Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Double and Weft Ikat Telia

Types of Telia

Telia Rumal

Lungi and Dupatta

Dhoti

Janani

Some Modern Telia Motifs

The Story of Telia

The Manufacture of Telia

The Automated Asu

Bibliography

The Double and Weft Ikat Telia

A telia is a plain woven square or rectangular cotton cloth that has a geometrical layout and is generally coloured red, black and white. It is made using the resist dyeing techniques of weft ikat and double ikat, in combination with a traditional dyeing process based on morinda. This is similar to the process used for dyeing Turkey Red and is responsible for imparting the characteristic deep red colour to these cloths. The dyeing procedure requires the cotton yarns to be pre-treated with oil extracted from seeds such as sesame or castor, the residues of which impart a strong and distinct smell to the finished cloth. Because of this the double ikat telia is often referred to as an ‘oil cloth’. Its nomenclature telia literally means oily and is derived from tel for oil (Forbes, Dictionary of Hindustani, 1848, 175).

Interestingly the original source of that oil, sesame, is known as til. Three varieties were cultivated in India: white-seeded suffed-til, red or partly-coloured kala-til and the most common type, black sesame or tillee (Classified and Descriptive Catalogue of the Indian Department 1873, 75).

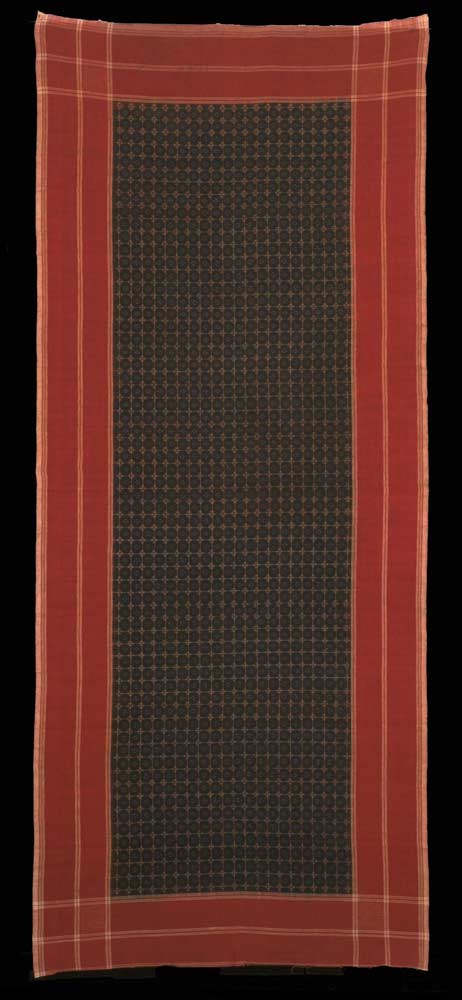

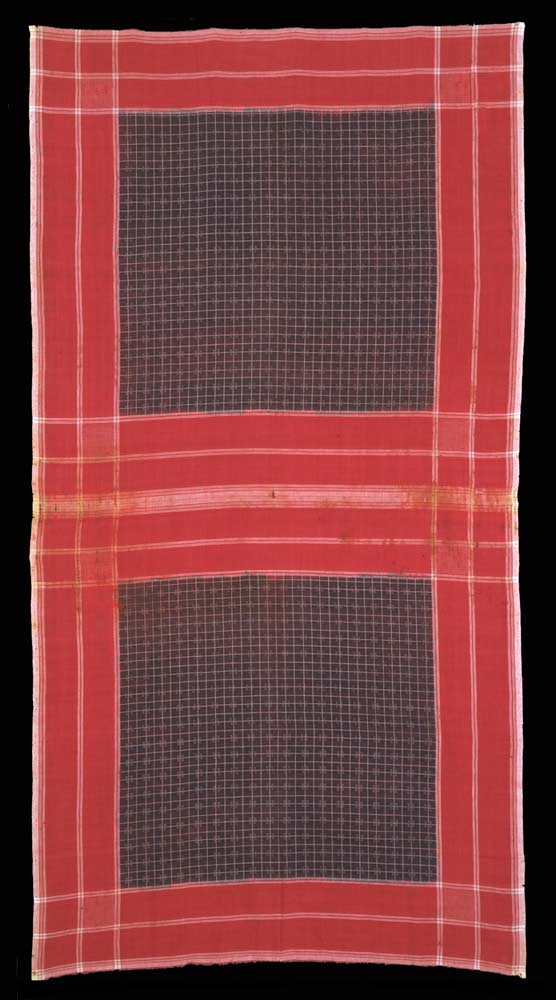

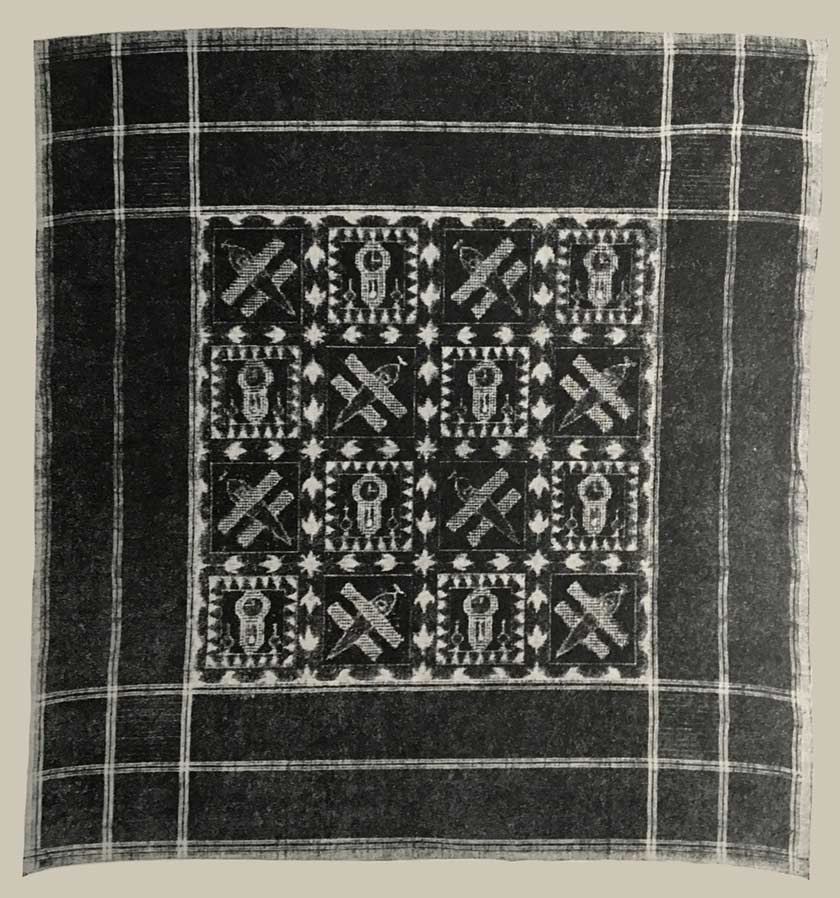

A telia from Andhra Pradesh, claimed to be late nineteenth century

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS. 161-1993, size: 250cm by 106cm

Telia ikats have only ever been produced by Hindu weavers belonging to the Padmasali (or Sali, meaning weaver) and Devang castes in the original state of Andhra Pradesh, which was divided in 2014, its north western part being split off to form the new state of Telangana, although Hyderabad temporarily remains the de jure capital of both. These weavers are of Dravidian origin and have been residents of this region for a long time, adopting the Telugu language of their neighbours. They wear sacred threads and worship the Gods Shiva, Vishnu and Naga, as well as trees (Mohanty and Krishna 1974, 21).

Generally whole families are involved in the production process, the knowledge of which is passed down from generation to generation. In the past children began learning details of the craft from the age of nine or ten, but today many youngsters see their futures in other professions. The majority of producers are employed by master weavers who supply all of the necessary materials and pay according to the number of finished items made. Today only a minority are familiar with the traditional and laborious natural colouring methods, relying on synthetic dyes instead.

The first telia appear to have been telia rumal (literally ‘oily handkerchief’), small cotton squares with dimensions of about 1.0 to 1.1 metres (42 to 44 inches), which were locally called chowkas (squares), chitki or chitti rumal, the latter from the Hindustani chhint or chint, derived from the Sanskrit chitra, meaning spotted or bright. They were primarily produced commercially, initially for local use but later mostly for export, not just to other states such as Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra but also further afield to Islamic communities in the Middle East, Africa, Pakistan, Malaysia and Burma. The export traders referred to them as Asia rumal.

Telia cloths were worn as turbans, head covers and lungis by agricultural labourers and cow herders and especially by fishermen, because the oily cloth repelled water. Later they were made larger for use as women’s dupattas and saris, some of which were embellished with embroidery by the wealthier women of Hyderabad.

Return to Top

Types of Telia

Telia were made in a number of sizes and types:

- Telia rumal are almost square kerchiefs that were used singly or in pairs as turban pieces or lungi waistcloths.

- Lungi are rectangular cloths about 2.0 to 2.6 metres long that are wound around the hip.

- Dhoti are longer than a lungi, having sufficient extra material to draw up between the legs.

- Mardan are turban cloths that are longer and narrower than the other fabrics.

- Dupatta or dupatti, literally ‘two-piece fabrics’ consist of two equal parts, and were worn by Muslim women over a skirt and blouse.

- Saris are cloths composed of two uncut lungi. In Andhra Pradesh a true sari is called a janani and is normally around 7.32 m long.

Return to Top

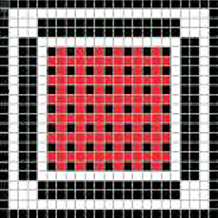

Telia Rumal

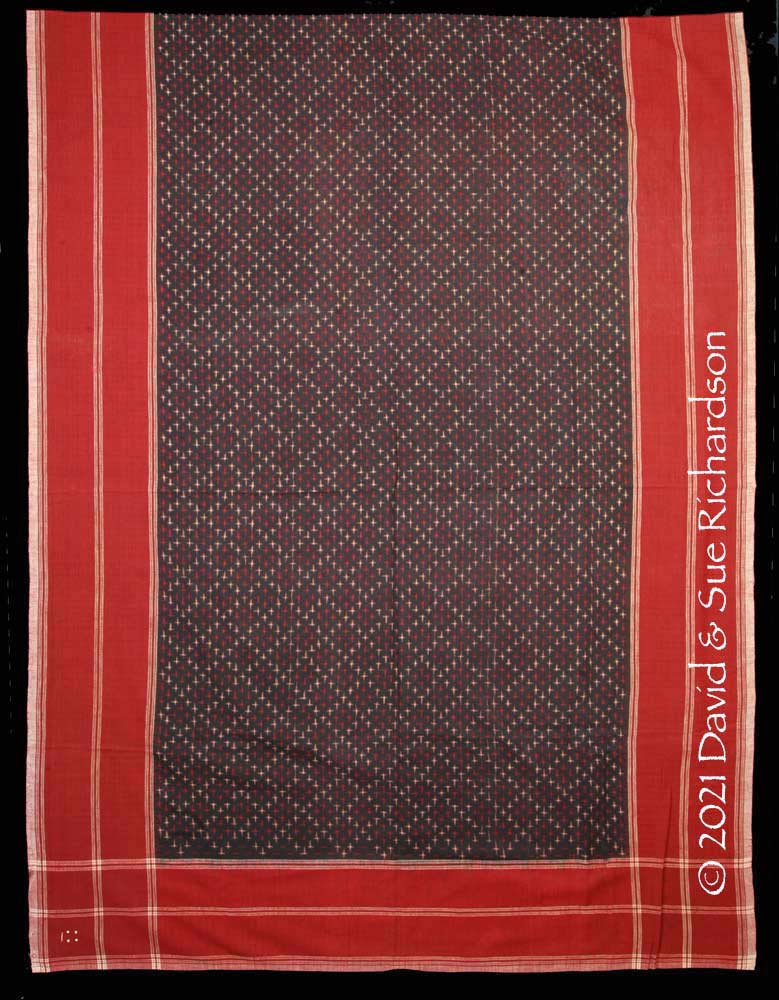

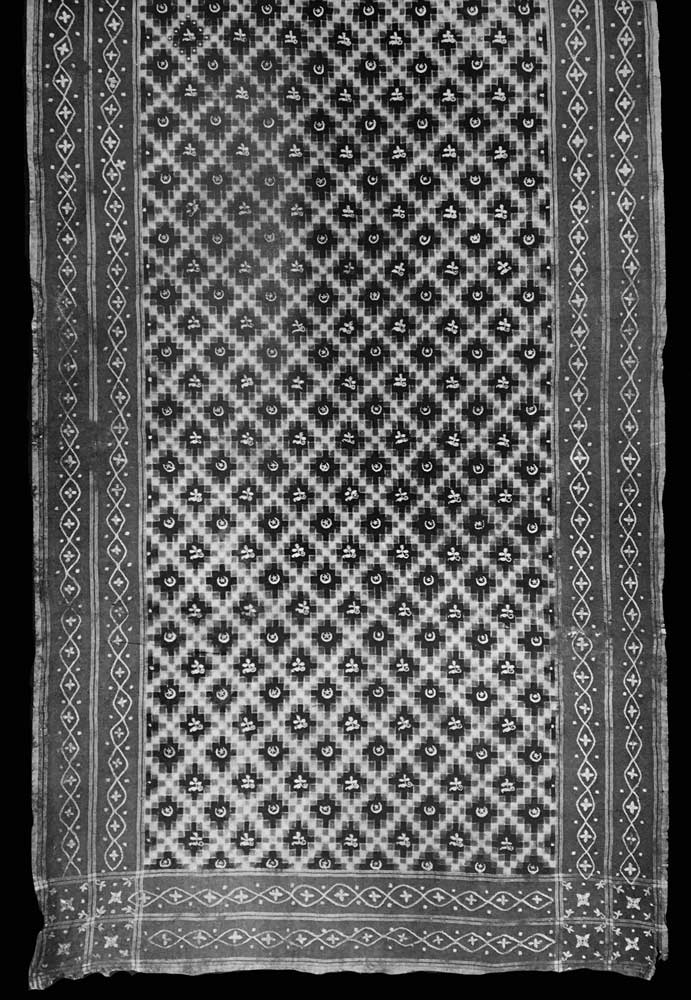

Telia rumal kerchiefs were the most common type of ikat telia produced in Andhra Pradesh. They have a centre field decorated with a geometrical lattice surrounded by a wide, double, single-coloured border. The outer border is generally red and surrounds a black centre field, although in a few the colours are reversed. A minority are either all red or all black. The outer border most commonly contains small square corner fields patterned with fine checks.

They were woven in lengths of eight pieces, which were known as than (Crill 1998, 87). It seems that some of the earlier pieces were woven with a weft ikat centre field and the warp ikat was only applied to the outer borders, creating the finely chequered corner squares. Some are entirely woven in weft ikat, the finely chequered corner squares being woven from plain warp stripes and an ikatted weft. Pieces completely woven in double ikat seem to have been a more recent development.

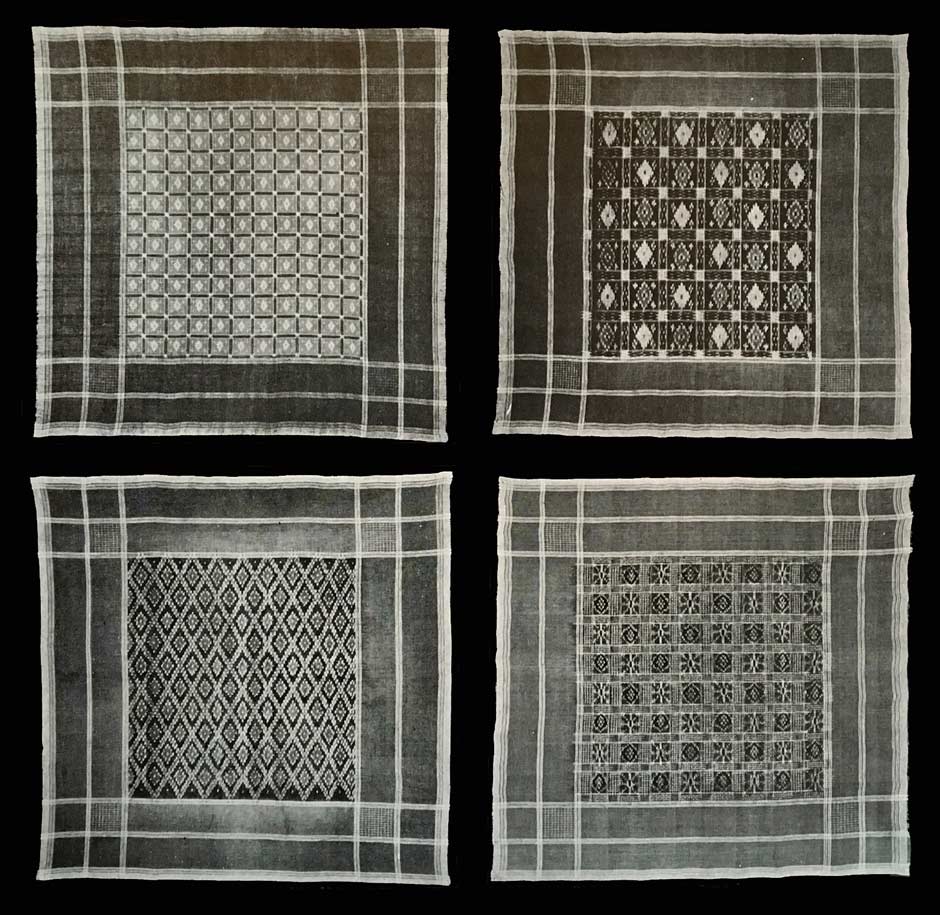

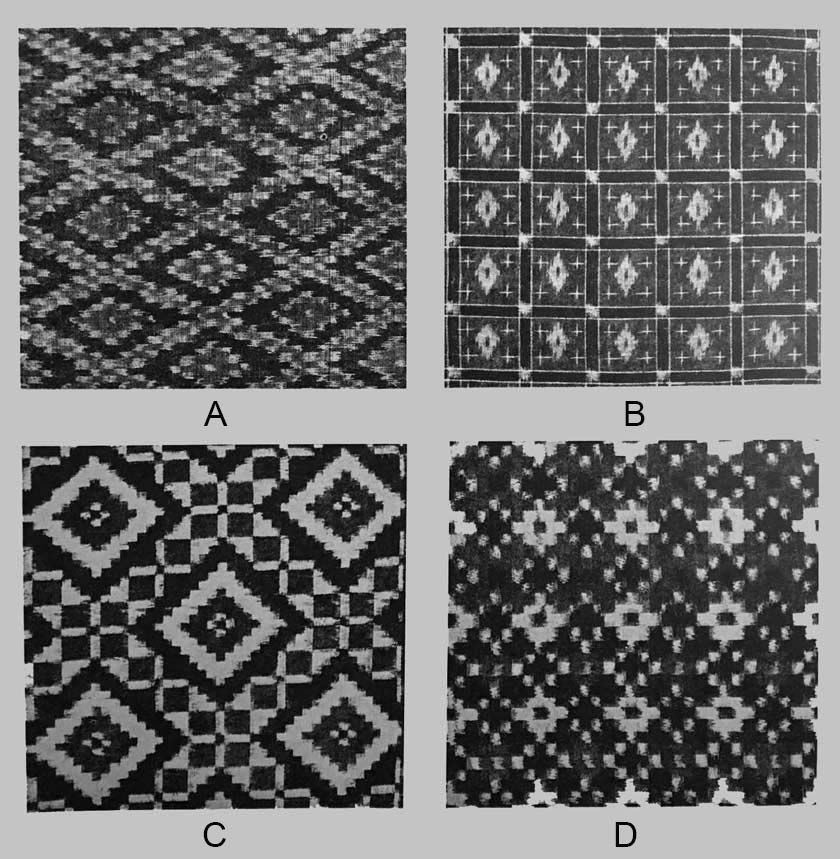

A selection of mid-twentieth century telia rumals from Pochampally

Calico Museum, Ahmedabad

Large numbers of rumals were exported from Pochampally to the Persian Gulf, Aden and even East Africa where the cloths were used as turbans and loincloths. The oily finish of the rumals was said to keep the head cool and free of dust. To test for authenticity, customers would sniff the cloth and chew a thread picked out of the cut edge to check for the oil and alizarin content.

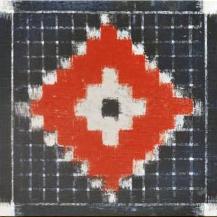

A naturally-dyed telia rumal with a weft ikat centre field and double ikat borders. From Chirala, Guntar District, Andhra Pradesh, made in the early 1900s. 113cm by 105cm. Richardson Collection

The following six examples were part of a former private collection acquired in about 1990 in the region of Hyderabad by the late Robin Guild, a London interior designer and a partner in India Works, based in Delhi, and his wife Shirin Guild, a well-known Iranian fashion designer. All six were woven in Chirala with weft ikat centre fields and double ikat outer borders.

Over time patterns evolved from the uniform designs based on small simple repetitive motifs to larger figurative motifs. Apparently these were popular with Middle Eastern customers (Crill 1998, 88).

A later telia rumal from Pochampally, acquired in 1999 in a fishing village in Tamil Nadu. Richardson Collection, size: 108cm by 107cm

Interestingly Rosemary Crill has compared the small square patterns of Indian telia rumals with those of the double ikat geringsing textiles of the Bali Aga in Tengganan on Bali, whose culture is Hindu and whose ancestors may have links to India. She has also drawn attention to the historical trade inks between coastal Orissa and Andhra Pradesh and Indonesia (1998, 156-157).

Return to Top

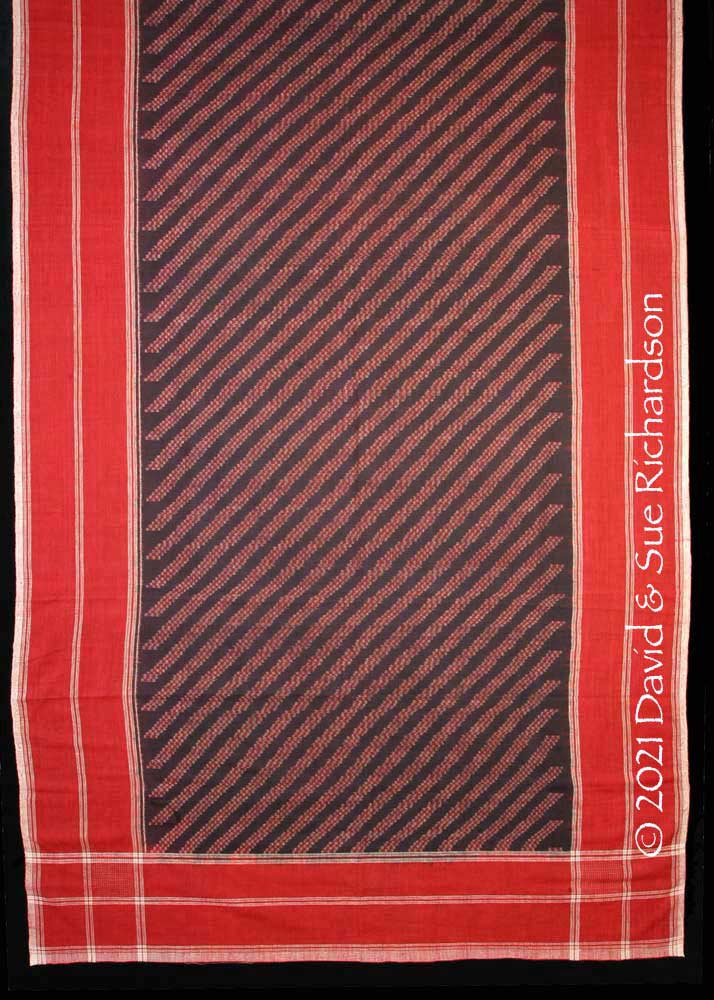

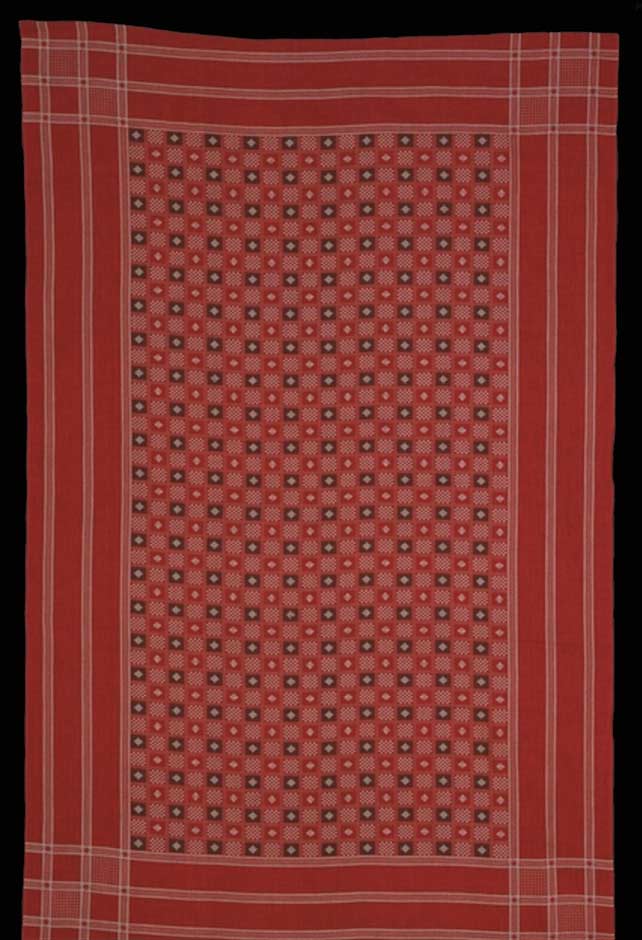

Lungi and Dupatta

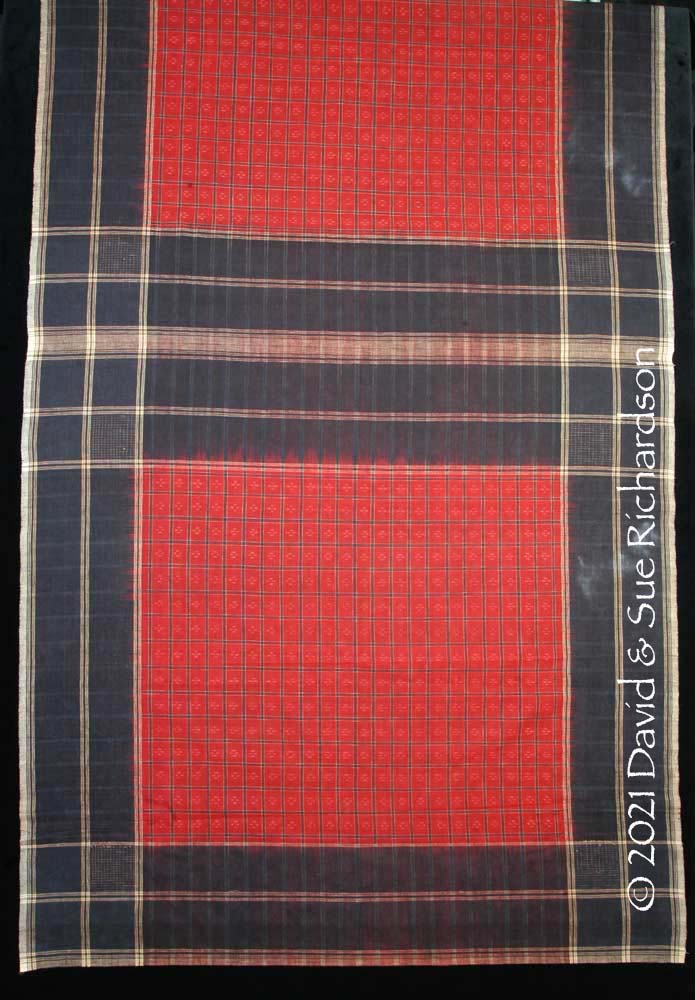

Complete telia lungi or telia dupatta were roughly 2.0 to 2.6 metres long and 1.0 to 1.2 metres wide with a double border, normally red, enclosing a central field of geometric motifs arranged in a rectangular lattice.

Because two uncut telia rumal were normally sold together as a pair they were often left this way and used either as a lungi or as a dupatta. When worn as a lungi the line dividing the two square patterns was worn at the back.

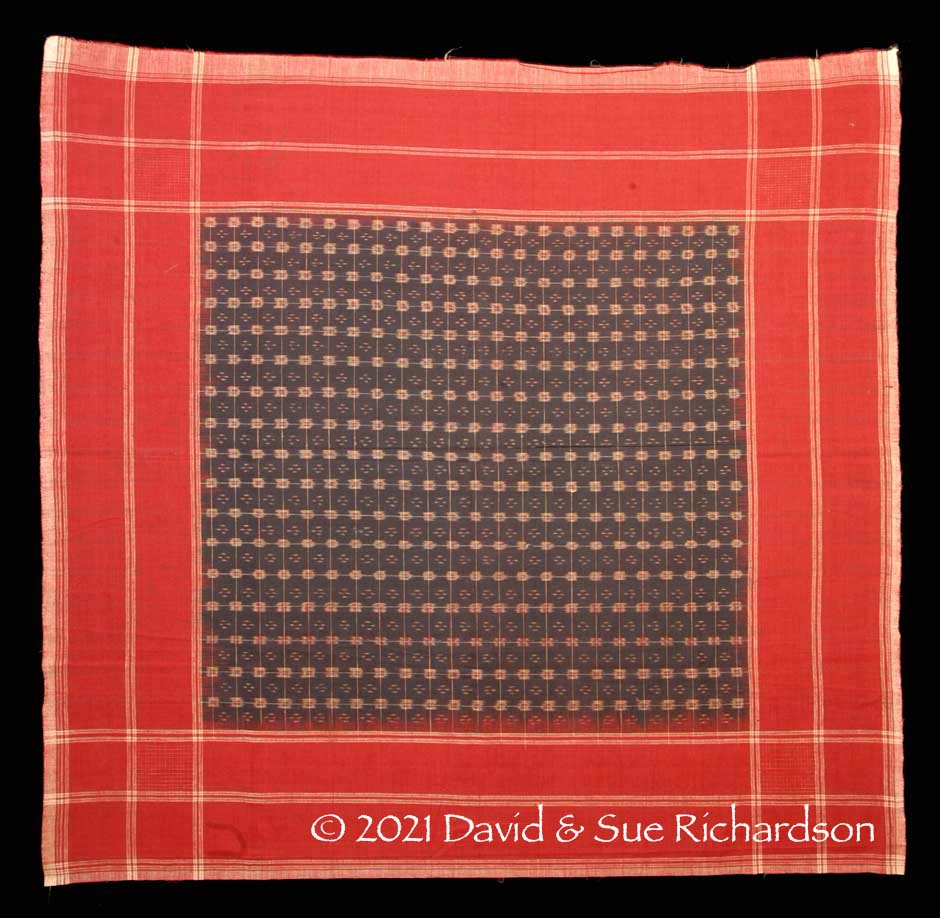

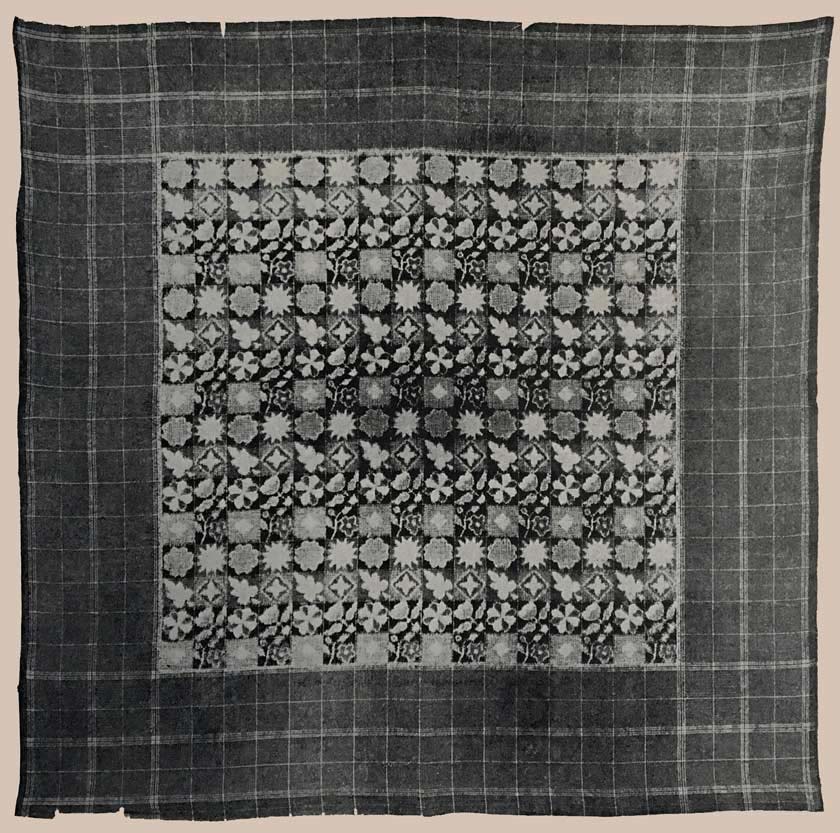

A pair of telia rumal from Andhra Pradesh, claimed to be late nineteenth century

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS. 159-1993, size: 208cm by 111cm

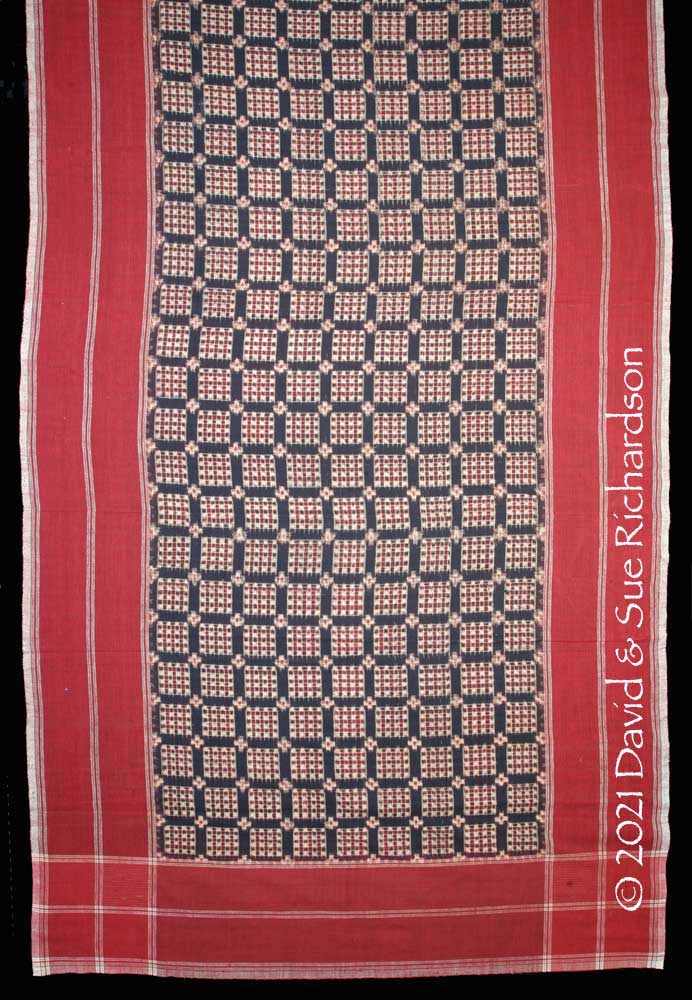

Above and below: two pairs of telia rumal from the former Guild Collection

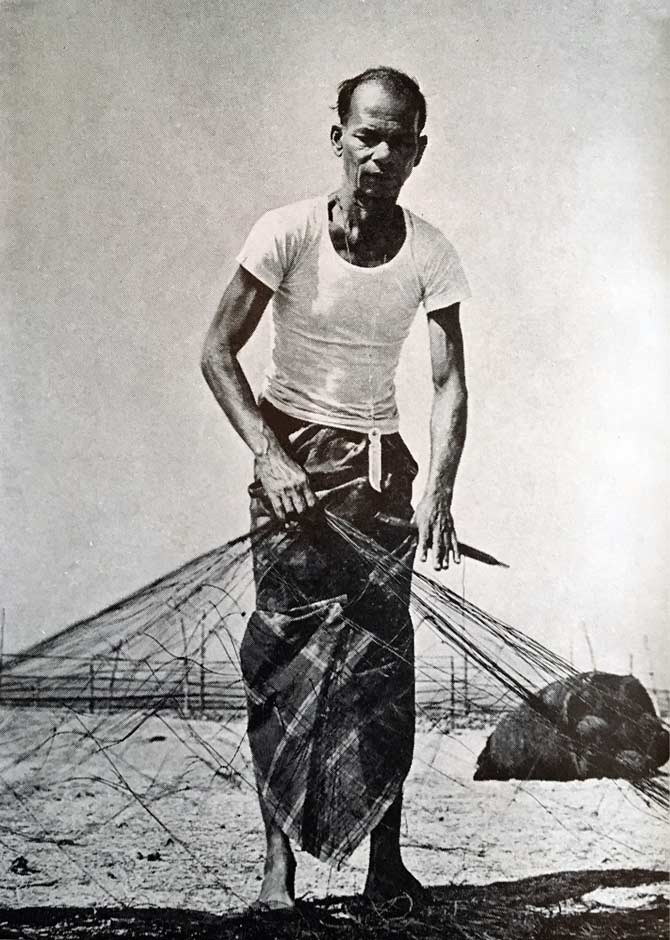

The lungi man’s hip cloth is wrapped around the waist and secured with a knot called a duba. The lungi is thought to have originated in south India and migrated up the east coast to Odisha and Bengal and then into Myanmar. It also migrated south to Sri Lanka. This may be why the lungi is still more popular in coastal towns than inland, especially among fishermen.

A fisherman wearing a telia lungi on the coast of Andhra Pradesh

The term lungi appears to derive from the Persian word long, a rectangular chequered cotton cloth worn as a loincloth in the hammam (Floor 1999, 168). The loincloth weavers in Isfahan were known as longbaf. It is possible that Persian traders sailing from ports in the the Gulf introduced the term to southern India. Between the seventh to the tenth century Persian had become the lingua franca of the southern seas (de Saxce 2016, 125).

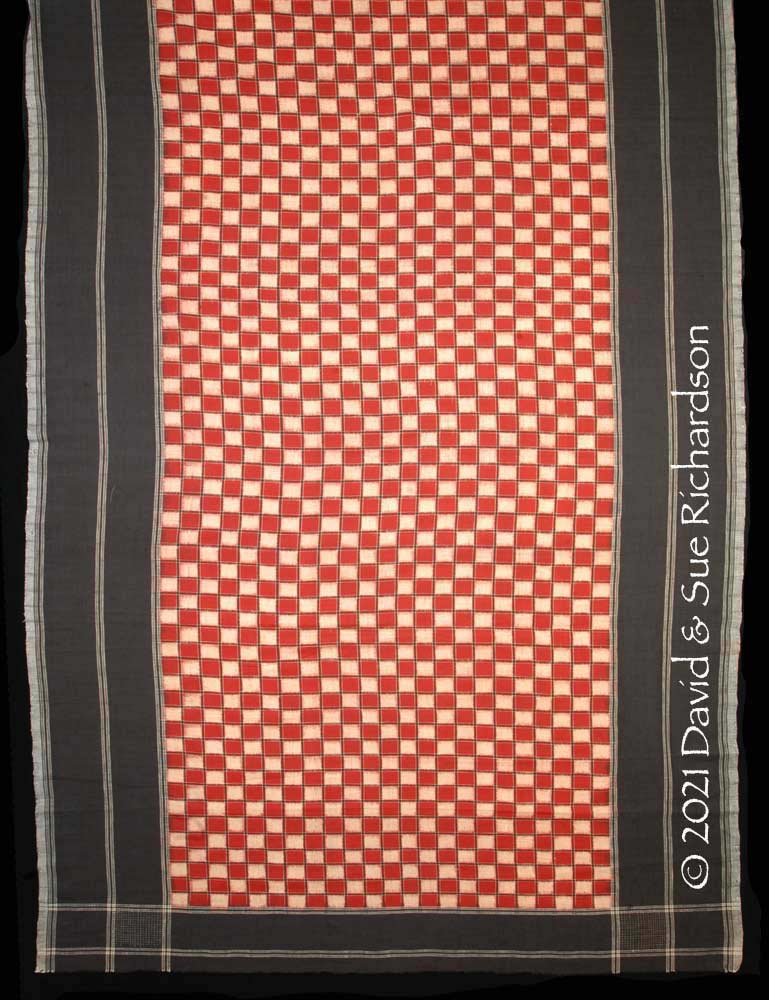

A lungi from Andhra Pradesh with no provenance, but thought to date from around 1900

Calico Museum, Ahmedabad

Lungi were worn by fishing communities and cowherds in Andra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra and were popular among poorer Muslims in Andhra Pradesh and other parts of India.

The dupatta is a woman’s waist wrapper, shawl or headcloth most common in southern India, especially among the Muslim community. The term means two breadths (Forbes, Dictionary of Hindustani, 1848, 267), or a piece of cloth of which there are two breadths (Yates, A Dictionary of Hindustani, 1847, 268). It derives from the Sanskrit terms du, meaning double or twined and patta meaning a piece or a piece of cloth.

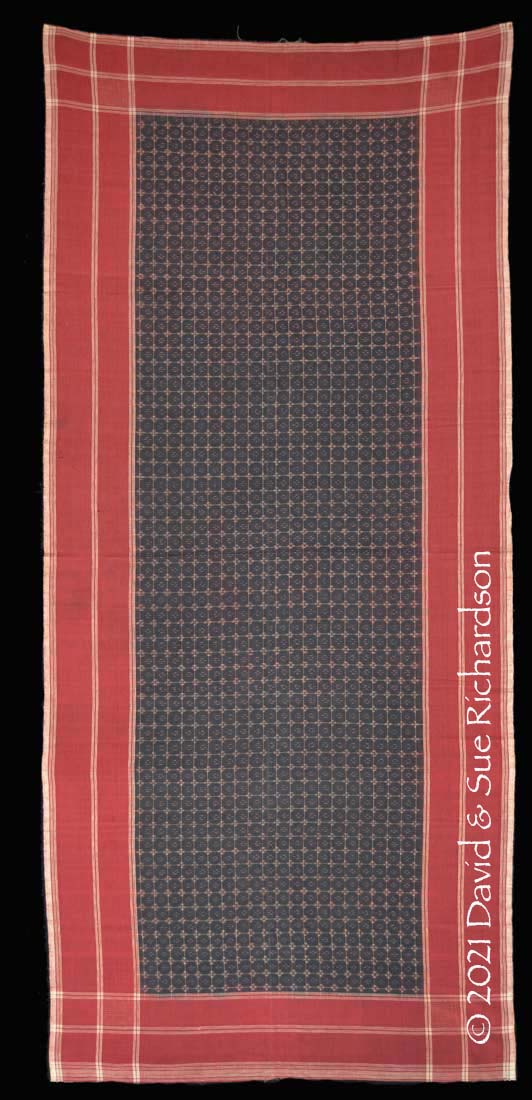

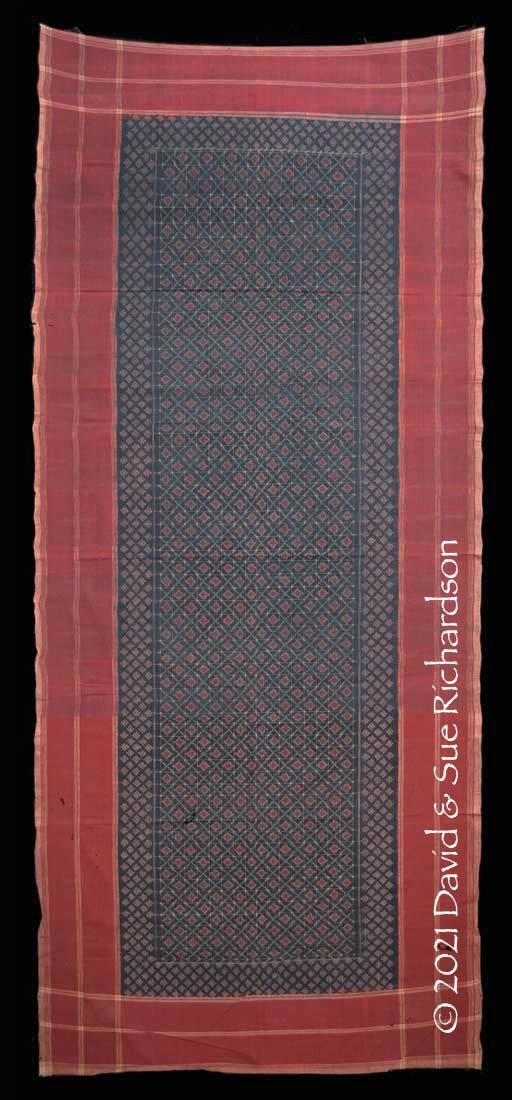

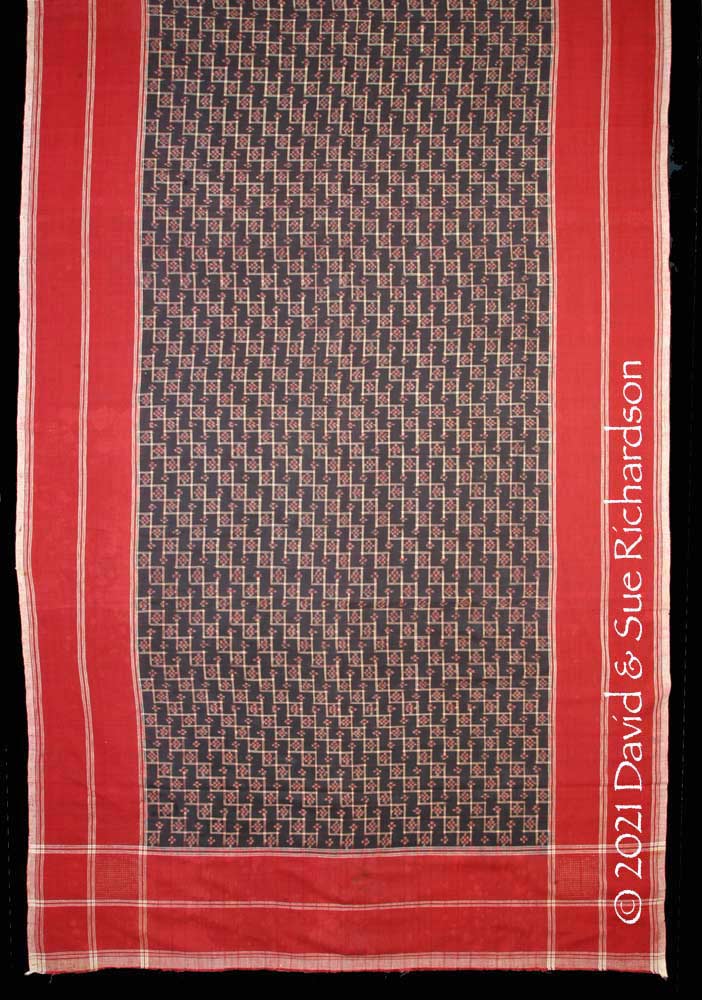

A man's telia lungi lower body wrap or possibly a woman’s telia dupatta.

Weft ikat centre field, double ikat borders,254cm by 106cm

Richardson Collection

A man's telia lungi lower body wrap or possibly a woman’s telia dupatta.

Weft ikat centre field, double ikat borders, size: 262cm by 115cm

Richardson Collection

The following five naturally dyed lungi or dupatta are from the former Guild Collection and are believed to have been made in Chirala. The first has a centre field woven in weft ikat, but the other four have centre fields woven in double ikat.

Telia dupatta were worn by wealthy Muslim women over their skirts, baggy trousers with drawstrings around the ankles (known as payjama or salvar) and their blouse (Bühler et al 1980. 72). Muslim women in Hyderabad often embellished their dupatta with embroidered metallic yarns. Sometimes the embroidery echoed the lattice design, but in other instances it was independent and totally unrelated.

A telia dupatta from the Hyderabad region embroidered with silver gilt yarns

Calico Museum, Ahmedabad

Return to Top

Dhoti

A dhoti is a large cloth wrapped around the waist and then passed between the legs with the end tucked into the fabric at the waist in the back. A dhoti resembles baggy trousers with draped pleats at the front, but unlike trousers is made of unsewn fabric. Commonly, dhoti drape below the wearer's knees to mid calf, but some men in warmer parts of India and young boys wear the dhoti above the knee. Although normally created out of a single piece of fabric, the dhoti can also be secured by a kamar-band, or a piece of cloth tied around the waist like a belt.

The term dhoti is a long-established Hindu word. It is often reported without any supporting evidence that it derives from the Sanskrit dhauta, meaning washed, cleansed, purified, bright, white or shining. It seems more likely that it derives from the Sanskrit term dhati, referring to a piece of cloth worn over the private parts.

Dhoti are usually around 4 to 6 metres long, so could be made from a loom length of four to six uncut telia rumals.

Return to Top

Janani

In Andhra Pradesh a woman’s sari was known as a janani and was about 7.30 metres in length. We have not yet discovered any examples of telia janani. Bühler et al also found no examples of such ikat textiles from Andhra Pradesh. It is possible that a than, a complete loom length of eight telia rumals, could have been worn as a janani. According to Bühler, in the past two uncut telia lungi were sometimes used as a sari (Bühler et al 1980, 72).

Return to Top

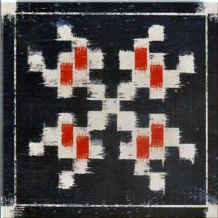

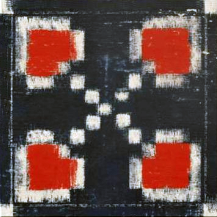

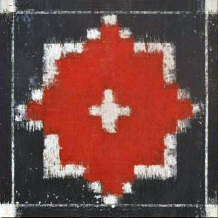

Some Modern Telia Motifs

Some of the more common modern telia rumal motifs were identified in a survey of 30 telia weavers in the villages of Puttapaka and Koyyalagudem in Yadagiri Bhuvanagiri conducted during 2017 and 2018 (Duguta et al 2019). Most of these motifs were inspired by activities in daily life, local fauna and flora, fruit and even local games.

The motif pachhis kana (also called nilam peka) represents a popular local board game played by four people, each with their own round counters.

The motif udita kallu literally means squirrel eye.

The star-shaped motif is simply called nakhatram, meaning star, or mallepulu (jasmine) representing purity, kindness, and marital life.

The motif mudda banti represents the petals of the marigold flower (banti) or a bunch of marigold flowers. Marigolds are considered pure and have become an important Hindu religious symbol, used to honour all the gods and goddesses, especially Laxmi and Ganesh. Marigold garlands are hung everywhere, in Hindu temples, at weddings and funerals, at festivals, restaurants, hotels, stores and even on vehicle windshields.

The grid-like motif is called mungi.

The stepped diamond motif is called kaya. If the diamond is surrounded by a grid the motif is called mungi dabbalu.

Stepped diamonds arranged in a grid pattern are called mungi kaya.

Finally the heart-shaped motif symbolising love is called badam, after the almond or badam seed.

Return to Top

The Story of Telia

Although the evidence is sketchy, the weaving of weft ikat in Andhra Pradesh might have been a long-standing tradition (Crill 1998, 98). Today most of the traditional ikat woven in Andhra Pradesh is simple, using mainly cotton and geometric designs that include up to three colours (Bühler et al 1980, 69).

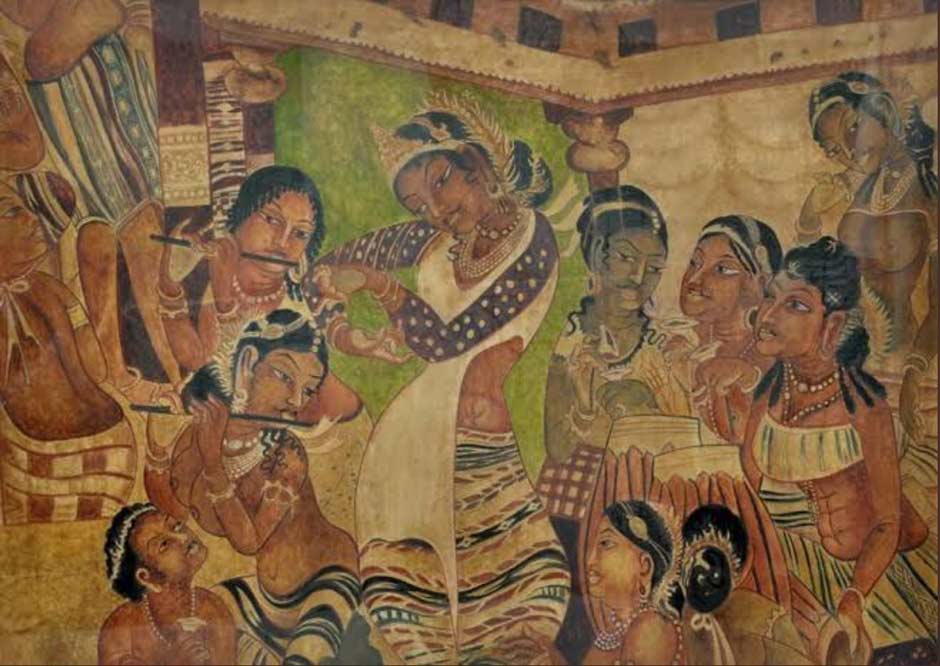

Presumption of early ikat production on the Indian Deccan comes from some of the Buddhist murals painted by monks in 30 rock-cut caves at Ajanta in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra State, located 450km northwest of Hyderabad. The most important are those in cave 1, dating from between 500 and 600 CE. They relate to the Mahajanaka Jataka, the story of Mahaa-janaka, the future Bodhi-sattva, who renounced the world and went to the Himalayas to meditate and seek enlightenment.

The detail in these murals has deteriorated through time, but can be better appreciated from painted copies produced by John Griffiths and seven students from the Bombay School of Art between 1877 and 1881. These depict women wearing skirts with bands that appear to have been decorated with simple linear weft (or possibly warp?) ikat patterns.

Detail of the mural on the left wall of cave 1 depicting an elaborately costumed dancer trying to entice King Janaka to change his decision to abandon his worldly life and become a hermit. Musicians are playing flutes, cymbals, drums and a stringed instrument. Photographed by Anandajoti Bhikkhu, Creative Commons Licence

Reproduction of the same image by John Griffiths et al

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS.31-1885

Detail of another mural in cave 1 depicting King Mahaa-janaka abdicating to become a wandering ascetic. Princess Shivali sits on his right. Photographed by Anandajoti Bhikkhu, Creative Commons Licence

Reproduction of the same image by John Griffiths et al

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS.31-1885

Apparently the Gujarati double ikat patolas that were exported to Malacca via Pegu in Burma in the seventeenth century were transhipped through the port of Masulipatam (now Machilipatnam) in Andhra Pradesh. It has been suggested that this might have been how the technique of double ikat was first introduced into this region.

Rosemary Crill has highlighted a few intimations that telia rumals or cloths of similar appearance might have been traded to Japan in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries (1998, 98). However most historical evidence indicates that the production of double ikat in Andhra Pradesh may have been a much more recent development.

The locations of Puttapaka, Pochampally and Chirala in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (Map courtesy of Australian National University)

The technique of making rumal textiles seems to have originated in Chirala, a coastal town in the Guntur area of Andra Pradesh, situated on the main railway line connecting Vijayawada and Chennai – only 95km down the coast from Machilipatnam. Sadly there is no information to indicate when the production of telia began in this village, although local weavers believe it dates back to the late nineteenth century. Elderly weavers interviewed in the early 1970s had no recollection of their grandparents making such textiles (Mohanty and Krishna 1974, 22). However in 1987 an elderly trader in Hyderabad recalled that his grandfather had traded ikat textiles to Aden at the beginning of the twentieth century (Crill 1998, 96-97).

By 1915, some 500 weavers in Chirala were specialising in producing square telia rumals. At that time it was the height of the export trade, so to increase output two local weavers, possibly brothers from the Karmakad family of the Padmasalis, were sent westward to Ponchampally in Nalgonda District close to Hyderabad, a distance of 250 km, to train additional weavers in rumal weaving.

A telia rumal woven in Chirala around 1930

We know that in 1936 one Chirala weaving family was exporting telia rumals to Aden (Mohanty and Krishna 1974, 22). Another was exporting to Arabia, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

However printed imitations of telia rumals were being mass-produced in Manchester, greatly undercutting the market for the genuine cloths. Before the outbreak of World War II the demand for locally produced cloths was already in steady decline.

A pair of imitation telia rumals printed in England in the early twentieth century

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS. 69-1990, size: 164cm by 94cm

An imitation telia, also printed in England in the early twentieth century

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London, IS. 69-1990, size: 164cm by 94cm

Weavers responded by introducing new and larger motifs, such as lions, elephants, birds, flowers and even clocks and aeroplanes.

A telia rumal woven in Chirala around 1950 decorated with aeroplanes and clocks

Over the following decades hundreds of weavers lost their livelihoods and turned to other work. There was only one other village within a radius of 20km of Chirala that was weaving telia rumals immediately after the war – Jandrapeta, almost adjacent to Chirala. Here weavers eventually abandoned making ikat because it was not as profitable as weaving simpler textiles.

By the early 1970s there were only ten weavers left weaving rumals in Chirala, not all working full time (Mohanty and Krishna 1974, 22). Mohanty and Krishna interviewed a 78-year-old Chirala female weaver who was weaving 16 chowkas every 20 days for a piece rate of Rs. 1.50 per chowka. Younger weavers could make the same number in just 8 days.

By 1979 there was only one master weaver and dyer still continuing to produce rumals in Chirala – Gunti Bhaskar Rao (Crill 1998, 90). His workshop received support from five other families, who carried out some specific parts of the production process, such as the oiling process which requires the use of impure sheep’s dung. Some of his telia rumal were exported to the Persian Gulf, where Arab customers had a preference for cloths that had been overdyed in pink.

Sadly today, the weaving of rumals in Chirala is finished.

It seems that Chirala was initially eclipsed by Ponchampally and the surrounding villages, which by the early 1970s had become the chief centre for weaving telia rumals. Interestingly it seems there was no social link ever established between Ponchampally and the originating village of Chirala (Mohanty and Krishna 1974, 22).

Some of the patterns being produced in Pochampally around 1950

A. Pakachekram laider rumal; B. Nilu paka batani rumal

C. Peddapadgu rumal; D. Pagdu bandhu rumal

Weavers in the Ponchampalli region began to innovate and diversify. Unlike the weavers of Chirala they adopted chemical dyes and new production techniques but their synthetically dyed cloths did not smell oily and lacked the softness and shading of the Chirala pieces. While they continued to make small numbers of rumals for the local market – mainly fishermen – they began to produce a wider range of cloths targeted at new markets. They began to produce double ikat jananis (local saris some 7.3m long), dupattas for the Muslim market, mardan turbans and even saris. By the late 1970s all of their textiles were being made with synthetic dyes (Bühler et al 1980, 69).

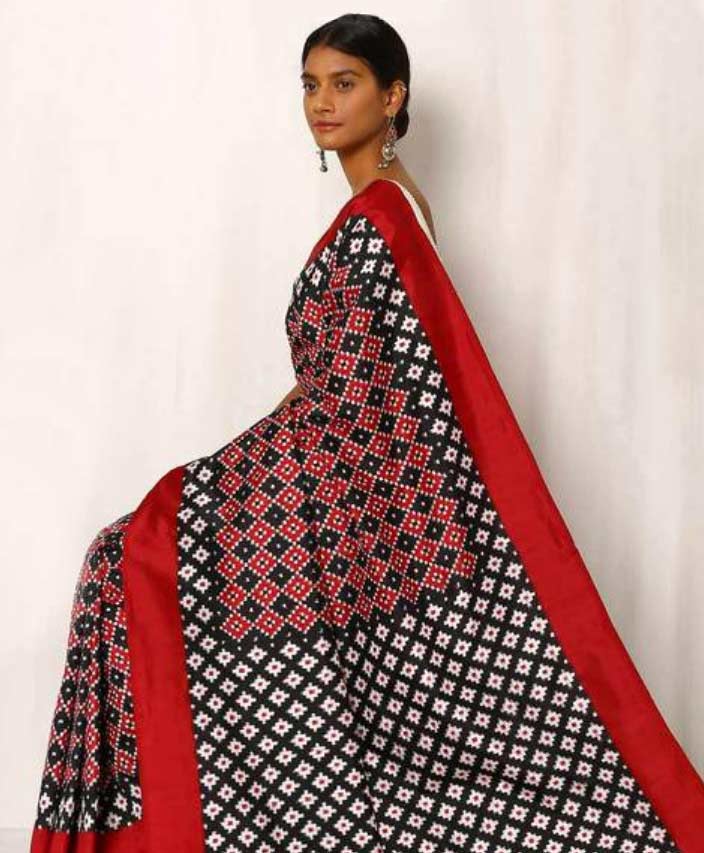

They also began using silk, mostly obtained from Bangalore, to produce more sophisticated versions of the telia targeted at wealthier urban consumers.

A modern silk Pochampally telia rumal sari selling for Rs 15,000 ($205)

By 2003 there were still around 5,000 weavers in Pochampally weaving ikat but they were struggling against imitation cloths woven on an industrial scale using power looms. At the end of that year the local weaving co-op applied for intellectual property rights protection, which was awarded one year later under the Geographical Indications category. Sadly this resulted in little improvement in their situation because the cost of litigation to stop infringement was prohibitively high.

Today the weaving of telia in Pochampalli is limited to less than 2,000 weaving families spread across a number of surrounding villages such as Koyyalagudem and Choutuppal just south of Pochampalli on the main road to Hyderabad, Siripuram, Bhubangiri, Chuigottala and Galteppala (Ghosh and Ghosh 2000, 23-24). It has been reported that even the sons of the late celebrated Pochampalli telia rumal weaver Chiluveru Ramalingam, a national award winner, have not taken up weaving as their profession. All chose alternative professions having witnessed their father’s struggle to make a living from handloom textiles.

The only telia weaving centre that survives today is Puttapaka, also in Nalgonda district. In 1975 Gajam Govardhan, an official working for the Ministry of Textiles visited Chirala and realised that the weaving of telia was on the wane and that the looms that produced them were falling into disuse. Belonging to a family of weavers in the undeveloped village of Puttapaka he decided to try and revive the traditional craft. The Gajam family began weaving traditional telia using the oil and alizarin process and later began to innovate with new designs.

The Gajam family’s big break occurred in 1980, when they were visited by Pupul Jayakar, a cultural activist and advisor to Indira Gandhi who was actively promoting the revival of traditional village handicrafts and handloom weaving. At the time she was organising the Festivals of India, exhibiting Indian arts and crafts in London, New York, Tokyo, Moscow, Sweden, and Denmark. The Gajam family were invited to participate and as a result gained much acclaim. Pupul Jayakar later obtained government funding for the Gajams to invest in bigger looms for making saris. In 1987 Gajam Govardhan participated in the Vishwakarma Exhibition in New Delhi.

From an initial 20 weaving families, Gajam Govardhan has trained 800 other weavers in the telia producing technique, maintaining the traditional dyeing methods. In 2011 he was honoured with the fourth highest civilian award from the Government of India – Padma Shri.

In 2017 Gajam Goverdhana applied for a Geographical Indication tag for the Puttapaka telia rumal and this was granted in May 2020. Today some 500 looms are operating in the Puttapaka area, but only four or five families are making telia textiles.

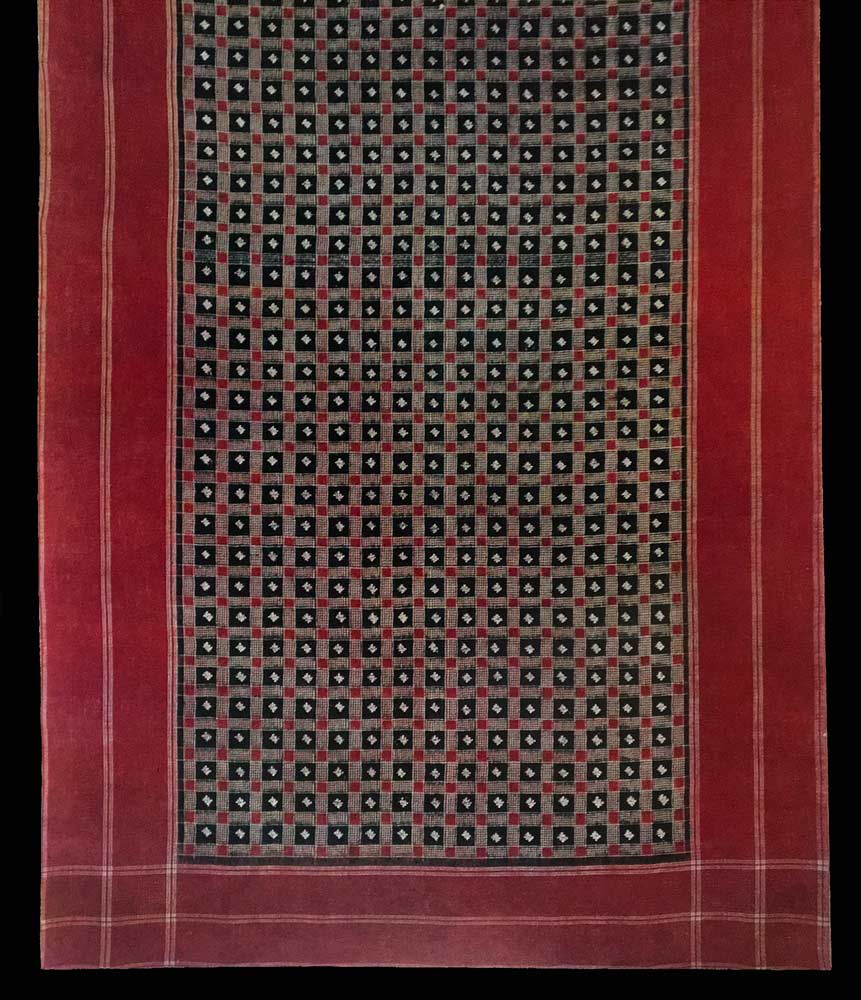

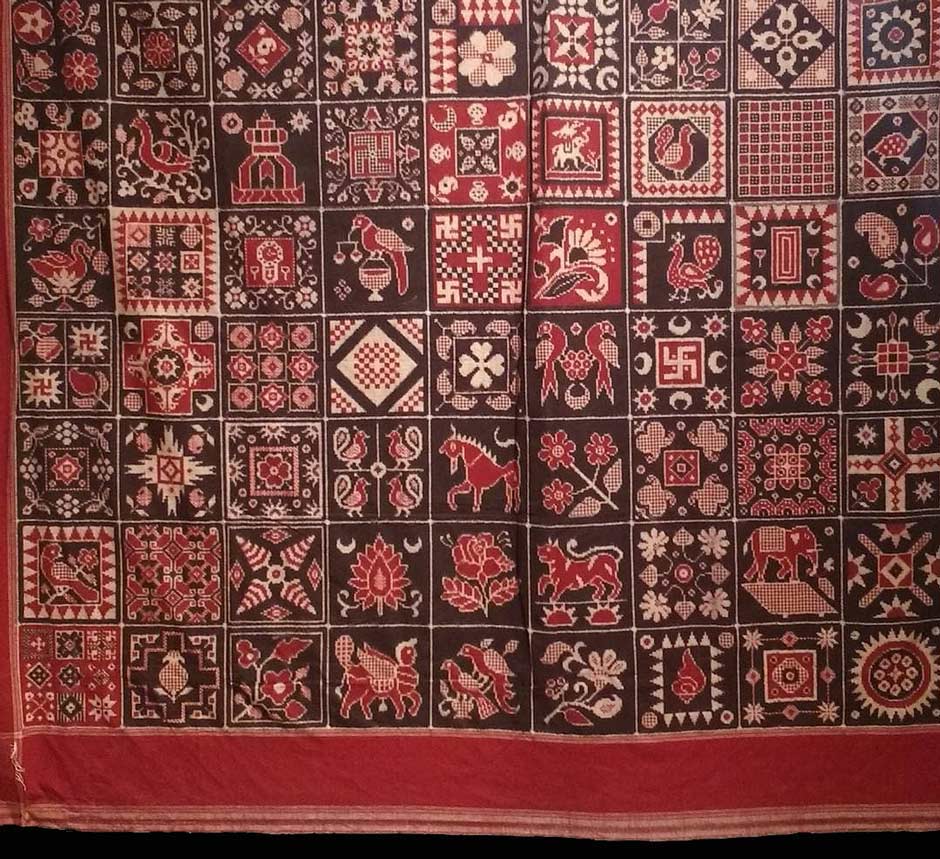

The exceptional Puttapaka telia shown below is from the collection of Padma Shri Gajam Govardhana and was made with 100 non-repetitive motifs. It was shown at the exhibition World Ikat Textiles: Ties that bind held in Bikaner House, Prince’s Park, New Delhi in 2018.

Segment from the Puttapaka telia in the collection of Padma Shri Gajam Govardhana

Return to Top

The Manufacture of Telia

Apparently local Andhra Pradesh weavers refer to the technique of telia making as pogdubandhu, chitki or buddabhashi (Ghosh and Ghosh 2000, 23). One report suggests that in Chirala it was known as chit-ku (Mahapatra 2016, 151). In Puttapaka they say chituki. Across India it is more widely known as pochampally, after one of its main centres of production.

Details of the traditional manufacturing process have only been properly documented in Pochampally (Mohenty and Krishna 1974, 89-90; Bühler et al 1980, 71-72).

Weavers used cotton threads with yarn counts ranging from the coarse 20s to the 40s, 60s, 80s and 100s, those finer than 100 being used for superior quality cloths. Note that an English yarn count of 100 Ne means there are 100 hanks (1 hank = 840 yards) of yarn in one pound.

The yarns for both the warp and weft were stretched on a warping board known as an asu, which is shaped like the quadrant of a circle, having about 35 regularly spaced pegs along the curved edge and one strong peg positioned at its axis. The yarns were stretched on the warping block and divided into bundles of 6 yarns, after which the white and black sections of the pattern were bound on each bundle. The details are transferred from a pattern that has previously been recorded on graph paper. A guide string attached to the central peg was used to ensure accurate placement of ties.

Cotton yarn was used for the finer ties and rubber bands for the larger ties. However the rubber does not form such a tight resist as the cotton and allows dye to seep into the knot creating a less precise pattern.

The asu appears to have been a Pochampally innovation. Weavers in Chirala used a rectangular warping frame.

Demonstrating the traditional binding process on an asu warping up block in Pochampally

Binding on a modern asu in a workshop in the Pochampally region

The bound yarns were removed for the first red dyeing stage and then dried before being stretched back on the warping frame so that some of the bindings could be removed from those areas that were to be dyed black and others added to protect the areas to remain red. The rebound yarns were then removed for the second dyeing stage for black. In Pochampally they most commonly used acid and direct dyes.

After dyeing and drying the warps were transferred to fly shuttle pit looms. After each pass of the shuttle the weft was adjusted by hand to ensure that it was exactly aligned with the pattern, thus maintaining the focus for the double ikatted sections (Mohenty and Krishna 1974, 89-90).

In the traditional dyeing process used in Chirala, the cotton yarns were first pre-treated for 21 days with soda, either the ash of castor seedpods or alkaline earth, oil extracted from either sesame seeds (gingelly oil), mustard seeds or castor seeds and sheep dung (Mittal 1962, 26f). Because this stage was considered unclean it was not carried out by the Padmasali community, but by lower caste workers.

Both the red and brown shades were produced using the dried powdered root of Indian morinda (Morinda citrifolia), known in Indian as al. Most writers refer to its active dye component as alizarin but it is in fact morindone, a different type of anthraquinone. For a full account of Indian morinda dyeing refer to the description provided by Dominique Cardon (2007, 146).

Iron splinters were added to the morinda to obtain a brown shade, while black was achieved by adding iron splinters dissolved in vinegar.

Fortunately the current process now used in Puttapuka has been described in the 2017 application for GI registration (The Consortium of Puttapaka Handloom Cluster 2020).

The stages are as follows:

Yarn Pre-Treatment

Commercial two-ply cotton yarn with a count of 80 or 120 is divided in bundles and steeped for 24 hours in a solution of fresh sheep dung, after which any foreign material is removed by shaking. The yarn is then sundried for 24 hours.

Next a mordanting bath is prepared by making a solution with ash of burnt castor-seed shells, which contain aluminum. After soaking for several hours, either castor oil or gingelly (sesame seed) oil is added and when the thick mix turns slightly white it is ready for use. The yarns are submerged in the mixture and squeezed well for 15 minutes, after which they are wrung out and stored overnight before being hung up the next day in the sun. In the evening the oil treatment is repeated and continued daily for sixteen days before a final washing and drying. If time is limited it is possible to treat the yarns twice a day for eight days. This process makes the yam soft and imparts the characteristic oily smell.

Warp Preparation

The mordanted yarn is first wound onto cones or cylinders and then transferred onto the large rotary warping machine (padduguadda), which not only enables the correct length of warps to be wound quickly – normally enough to produce eight telia rumals from one loom length. The padduguadda is fitted with a mechanism that forms the crosses, so that the sequence of yarns remains in the same order. After winding, markers are tied around the crosses so that the warps can be easily counted.

Warp Binding

The long warps are stretched out tightly in the street, tensioned between poles tied to wooden trestles fastened in place with stakes and ropes. After being tied into bundles of eight threads the designs are drawn onto the threads using a pre-prepared graph. The warps are starched and then bound with cords and strips of rubber cut from recycled bicycle inner tubes.

Weft Binding

The wefts are wound onto the asu for binding. The distance between the central peg and the pegs along the arc is equal to the width of the fabric, while the number of pegs used depends upon the design. The design is transferred from the pattern recorded on graph paper to the bundles of yarns, which are bound with strips of rubber cut from recycled bicycle inner tubes.

Dyeing

The colouring process is not specified in any detail apart from the fact that it is based on red natural alizarin-based dyes. In Puttapaka the black colour is obtained by mixing the alizarin dye with erakasu or erra kasu, known elsewhere as cutch or catechu. This is the gum resin extracted from the fresh heartwood of the cutch or khair tree (Acacia catechu). It is rich in a tannic acid complex that on its own produces a brown colour. To read more about catechu click here.

The light colour (normally red) is dyed first, after which some of the bindings are removed and then others are added to preserve the areas that will remain light. Then the yarns are dyed with the darker colour (normally black).

Preparation for Weaving

After the warps are dyed, the rubber ties are removed and they are immersed in a bath of acetic acid and starch to fix the dyes and add some stiffness. The warp is then taken out in the street and again is spread out to its full length under tension so that it can dry and be checked before being divided into single rumal sections with twines.

Meanwhile the weft is removed from the asu and wound onto pointed cylindrical-shaped swifts called parivattam. It is then transferred in the correct sequence to the small wooden or plastic sticks known as pims (sometimes pirns) that fit inside the wooden flying shuttle. This is done using a vertical wheeled charka spindle-winder, which draws the ikatted weft off the parivattam and onto the spindle, guided by the hand of the charka operator.

Weaving

The warps are transferred to flying shuttle pit looms made from teak that are known as maggam. They are operated by pulling a cord in the center of the loom that propels the shuttle from side to side. To weave the double ikat design, each throw of the shuttle has to be carefully checked to ensure the precise intersection of the design. However there is always an unavoidable slight movement of yarn that creates a feathered edge to the pattern. Adjustments can be made to any inexact alignment by tightening or loosening the heddles, loosening any yarns that are twisted or stuck together.

A master weaver can weave a full length of eight rumals in 4 or 5 days, while an average weaver might require several weeks to complete the same work.

Finishing

The finished fabric is starched, dried and inspected for flaws, which can be mended by hand.

Productivity

Because the most labour-intensive part of the process concerns the binding and dyeing of the warp and weft, more than one set of threads is normally prepared at one time. The amount will vary depending on the number of repeats across a design and also how many threads are in each unit of the design. If the bundle of threads is too large the definition of the motifs will be poor, especially if the design includes finely curved shapes. On average, eight warp sets (each containing enough for eight rumals) would be prepared together, along with an equal amount of weft. This means each bundle contains 64 threads (8 x 8).

A good illustrated overview of the modern process used in Puttapaka has recently been produced by Dastkari Haat Samiti.

Return to Top

The Automated Asu

The young Chintakindi Mallesham often watched his mother struggle to warp up her textiles manually in the village of Sharajpet, located to the northeast of Pochampally. In one day she would struggle to warp up enough yarn to make two saris, a process that involved winding around 14 kilometres of yarn onto the asu, requiring some 18,000 movements back and forth with one hand. This caused terrible pain in her shoulder and elbow joints and she would often tell her son that she could not continue doing this any more.

As a young engineer Chintakindi set out to see if he could automate the process. In 1999 he finally launched his first ‘Laxmi Asu’ semi-automated asu machine, named after his mother and powered by an electric motor. He then refined the winder by incorporating microprocessor controls. Despite costing around Rs 25,000 (about $340), he sold some 850 over the following 17 years (The Times of India 03.01.2017; The Hindu, 04.02.2017). The new machine reduces the warping up cycle from around six hours to about ninety minutes.

The automated Laxmi Asu and its inventor Chintakindi Mallesham

(Image courtesy of The Hindu)

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon 1, 2004. Pochampally handloom cluster receives IPR protection, The Textile Magazine, vol. 46, issues 1-6, pp. 78-79.

Anon 2, 2005. Andhra town weaves a success story as Ikat gets IPR, The Indian Textile Journal, vol. 115, issues 7-12, pp. 94-96.

Bühler, Alfred, Fischer, Eberhard, and Nabholz, Marie-Louise, 1980. Telia Rumal: Cotton Ikat Textiles from Andhra Pradesh, Indian Tie-Dyed Fabrics, Historic Textiles of India at the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad, vol. IV, pp. 69-87, Ahmedabad.

Crill, Rosemary, 1998. The Deccan: Andhra Pradesh, Indian Ikat Textiles, pp. 87-104, V&A Publications, London.

Duguta, Sushma; Sornapudi, Sirisha Deepthi; Shaik, Khateeja Sulthana, and Alapati, Padma, 2019. A Survey on Traditional Designs and Colors of Telia Rumal, Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology, vol. 32, issue 1, pp. 1-8.

Fereday, G., 1999. The Telia Rumal, The Dyeing Art, double geometric ikats of Andhra Pradesh, Surrey Institute of Art and Design, London.

Floor, Willem, 1999. The Persian Textile Industry in Historical Perspective 1500-1925, L’Harmattan, Paris.

Ghosh, G. K., and Ghosh, Shukla, 2000. Ikat Textiles of India, A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi.

Hiremath, Aloka; Jaitly, Jaya, and Chaudhuri, Chirodeep, 2017. Weaving the Telia Rumal, Dastkari Haat Samiti (Arts and Handicrafts Committee), New Delhi.

Jayaker, P. 1955, 'A Neglected Group of Indian Ikat Fabrics', Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. I, p. 55-64, Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad

Khurana, Purva; Pant, Suman and Chanchal, 2015. Telia Rumal: Relic to Contemporary Ikat, Fibre2Fashion.com https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/7561/telia-rumal-relic-to-contemporary-ikat

Khurana, Purva; Pant, Suman and Chanchal, 2016. Telia Rumal, double Ikat fabric of Andhra Pradesh, Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 167-172.

McCown, Dana, 2001. An Endangered Species, Telia Rumal - Double Ikats of South India, Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery, Queensland, Australia.

Mohanty, Bijoy Chandra and Krishna, Kalyan, 1974. Ikat Fabrics of Orissa and Andhra Pradesh, Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad.

Mittal, J., 1962. Telia Rumal of Pochampalli and Chirala, Marg, vol. XV, no 4, Marg Publications, Bombay.

Saxcé, Ariane de, 2016. Trade and Cross-cultural Contacts in Sri Lanka and South India during Late Antiquity (6th-10th Centuries), Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology, vol. 4, pp. 121- 159.

Swaminathan, S., 2011. Painting of Ajanta Caves (2nd century BC to 6th century AD): Appreciation of Mahajanaka composition

The Consortium of Puttapaka Handloom Cluster, 2020. G.I. APPLICATION NUMBER – 599, Geographical Indications Journal, pp. 21-27, Geographical Indications Registry, Chennai.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was first published on 25 January 2021.