Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Sumba Part 1

Geography

The Pre-History of Sumba

The Early Historical Period – Sandalwood and Slaves

Sumba in the Eighteenth Century – Early Dutch Contacts

Sumba from 1800 to 1866 - Dutch Negotiations Fail

Go to Sumba Part 2

Go to Sumba Part 3

Geography

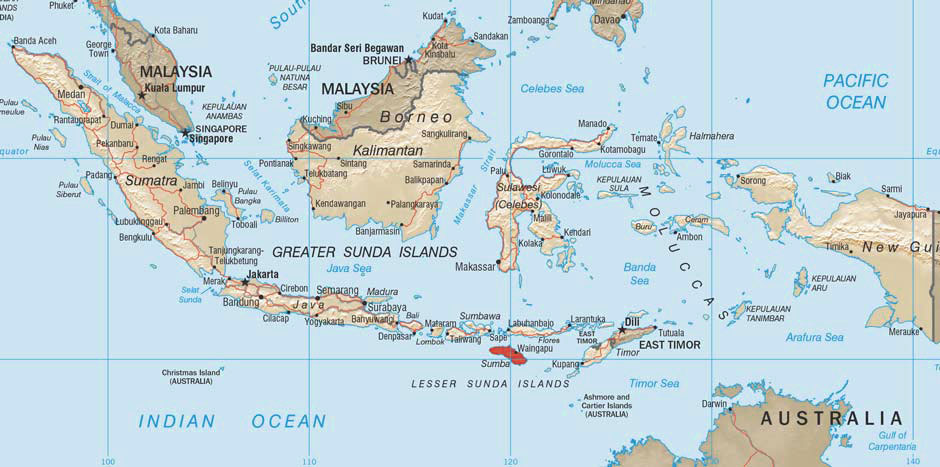

Sumba is one of the southernmost islands of Indonesia, separated from the western tip of Flores and the islands of Rinca and Komodo by the 50km-wide Sumba Strait. The coastline of Australia lies just under 700km to the southeast while the whole breadth of the Indian Ocean lies to the southwest, the nearest landfall being the Cape of Good Hope, some 10,000km distant.

The Indonesian Archipelago and the location of Sumba Island

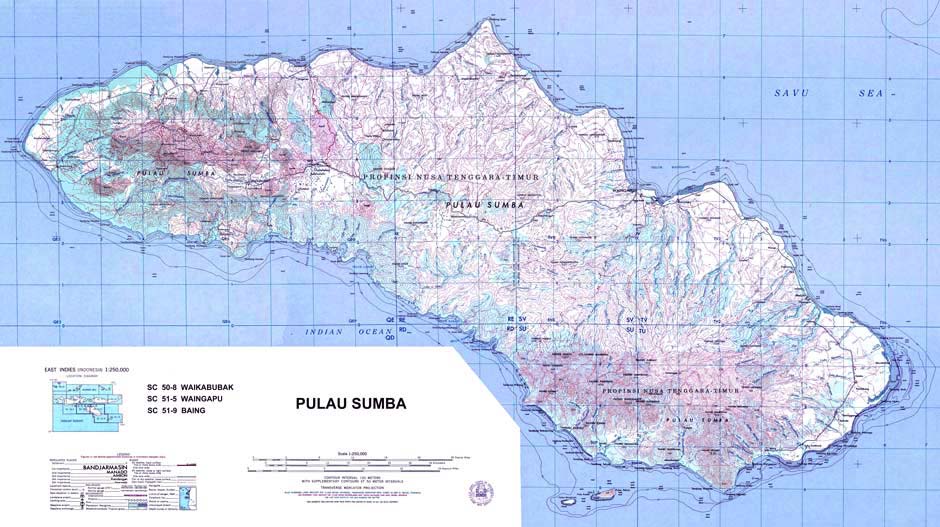

Roughly 220km from east to west, Sumba is a relatively low-lying non-volcanic island mainly composed of raised limestone plateaux broken by valleys and irregular hills. Although its marine limestone crust has been raised up from the sea floor, it sits on a much more ancient volcanic foundation.

The topography of Sumba Island (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

The widespread cutting and burning of firewood has caused severe deforestation across much of the interior, the remaining thin topsoil supporting a sparse cover of vegetation, mainly short grass savannah.

A limestone plateau carved with gullies on Sumba Island

The barren landscape of central Sumba in October at the end of the dry season

The highest elevations are located along the central spine of the western peninsula and in the southernmost part of the eastern peninsula. Their cores are the remnants of ancient long-dormant volcanoes. In the west the Jawila range extends west from Waikabubek, the highest hills being Tandaro (900m), Jawila (887m) and Pernubu (830m). The higher Masu complex in the southeast extends across the regions of Masu, Karera and Tabundung, the two highest hills being cloud covered Palindi Wanggameti (1,225m) and Palindi Anajadi (1,175m). These and their surrounding hilltops support the largest remaining area of closed canopy rainforest on Sumba, for which reason they were designated a national park in 1998. A dry low-lying plain fringes much of the eastern coastline. The northernmost Cape Sasar is sacred to most of the island’s inhabitants, being considered the spot where their ancestors first made landfall.

This map has been colour enhanced to show the mountainous regions in the west and south and the rivers flowing from them

The majority of the island’s many small rivers flow outwards from these two highland watersheds, the longest being the Luku Kambera, which rises on the slopes of Wanggameti and drains into Waingapu Bay, closely followed by Luku Kanatang, which flows from the Lewa Plateau to enter the Savu Sea at Kanatang. In the west the Luku Polapare flows from its source east of Waikabubak, reaching the southern coast between Kodi and Lamboya.

Sumba has a hot semi-arid climate, with rainfall varying across the island. The least rain falls in coastal areas and in the east, which has a climate similar to northern Australia, while the most falls in the hills of west Sumba. The rainy season prevails from December to March on the coast and from November to April in the interior (Forth 1981, 5).

Based on the 2010 census, the population of Sumba was projected to be 743,000 in 2014. Because the climate is drier in the east less land is suitable for agriculture. The population of East Sumba is just 247,000 and is mainly concentrated along the lower reaches of the rivers and the coastal plain, leaving much of the interior uninhabited. Wetter and agriculturally richer West Sumba, which is half the area of East Sumba, supports a population of 496,000, twice that of East Sumba. The two main urban centres are Waikabubak in the west and the port of Waingapu in the east.

The spectacular traditional village of Ratenggaro in Kodi, Sumba Barat Daya

Sumba is a relatively poor rural island. A 2002 survey covering every district of Indonesia found the poverty rate to be 47.3% in West Sumba and 43.9% in East Sumba - among the highest in the country and well above the national average of 18.2% (National Human Development Report 2004, 180-187). However such reports fail to include the income generated from the important barter economy. Almost 90% of the population are farmers and pastoral livestock herders while the government employs most of the remaining 10%. The main crops are maize, followed by rice, cassava, sweet potato and pulses. Important cash crops include coffee, cocoa, cashew nuts and coconut. Livestock has always been an important status symbol on Sumba and consists of horses, buffalo, cattle, pigs, chickens and goats. Although most major villages have a primary school, secondary education is restricted to the larger towns.

Paddy rice fields watered by the Kambera River

The only activity that can be called a domestic industry is weaving. In 2006 the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture established three commercial cotton plantations in east Sumba, while a 2005 project to exploit jatropha for biofuel in Memboro and Tana Rara has had only limited success. Since 2008 the Australian mining company Hillgrove Resources has been prospecting for gold and silver in Lamboya, Tanah Daro and Masu, but it has faced local opposition.

Preparations for a new plantation on Cape Sasar in 2017

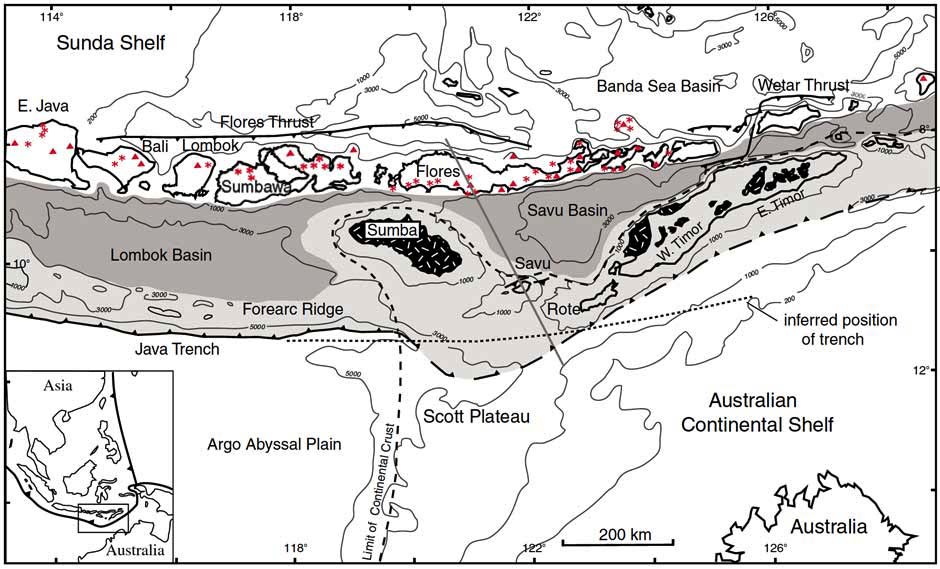

Geologically, Sumba is an uplifted fragment of continental crust, which may have once been a part of the more northern Sunda volcanic arc (Wensink and Van Bergen 1995). It sits on an extended promontory of the uplifted forearc ridge created by the collision of the Australian tectonic plate with the Eurasian plate and its subduction below it. Apart from the mountain cores, most of the island is composed of soft marine sedimentary limestone, which is readily eroded by acid rain. The gradual uplifting of Sumba from the ocean floor began around 7 million years ago at a rate of around ½cm per decade (Rutherford, Burke and Lytwyn 1998). It possibly first appeared as an island around 4 to 5 million years ago (Rigg and Hall 2011, 235).

Tectonic map of the Sunda-Banda arc formed by continental collision

The red stars are active volcanoes (after Harris 1992)

Sumba Island was called Pulau Cendana (Sandalwood Island) by the Portuguese and Sandelbosch Eiland (Sandalwood Forest Island) by the Dutch (Temminck 1849, 199). The British adopted the term Sandalwood Island (Horsburgh 1827, 529). The names refer to the white sandalwood (Santalum album) that once grew on the island. This was highly valued for its fragrant heartwood, especially by the Chinese. Sandalwood is an Australasian species that prefers a dry climate, hence its occurrence in the eastern islands. On Sumba it was probably more abundant in the river valleys along the east coast. Misleading historical reports suggest the mountains of Timor and Sumba were once covered in sandalwood. In reality sandalwood is a small, slow-growing tree with semi-parasitic roots that does not grow in dense stands. It had probably been significantly depleted by the end of the nineteenth century.

The traditional domains of Sumba

Sumba has been governed for most of the last half millennia – and probably long before that – by local noble families, each ruling over their own regional domain with their wealth derived from large swathes of land and numerous herds of large livestock. Competition between them resulted in many violent regional conflicts and a tradition of headhunting. The Dutch chose some of the more accessible local chiefs as their colonial representatives and appointed them as Rajas. After independence, Sukarno introduced a more democratic system of local government in 1958, with power transferred from the nobility to elected administrative heads or bupatis. Sumba was divided into two Kabupaten or Regencies – Sumba Barat and Sumba Timur. In 2007 West Sumba was further divided into three Regencies Sumba Tengah, Sumba Barat and Sumba Barat Daya. Today Sumba has 44 Kecamatan or sub-districts and 426 Desa or village administrations.

The town and harbour of Waingapu

Sumba remains relatively undeveloped outside of its two main towns. It is served by two airports – at Waingapu and Tambolaka – the latter constructed by the Japanese using slave labour (Geirnaert-Martin 1992, xx). Waingapu remains the main seaport. The island’s main two-lane road network is paved and in good condition but the quality of secondary roads varies. Mobile telephone coverage is fairly good.

Return to Top

The Pre-History of Sumba

The archaeology of Sumba Island has not yet been seriously investigated so our understanding of its early human occupation is sketchy.

The Palaeolithic

Sumba was probably first populated by early modern humans migrating from the ice-age continent of Sundaland to Sahul. Some may have reached the Lida Ajer cave on Sumatra 73,000 years ago while others had already established themselves in mainland Australia over 60,000 years ago (Westaway et al 2017; Clarkson et al 2017). Although Sumba was still an island at this time, 40km south of Flores it would have been accessible to seafarers capable of making the longer crossing from Timor to Australia.

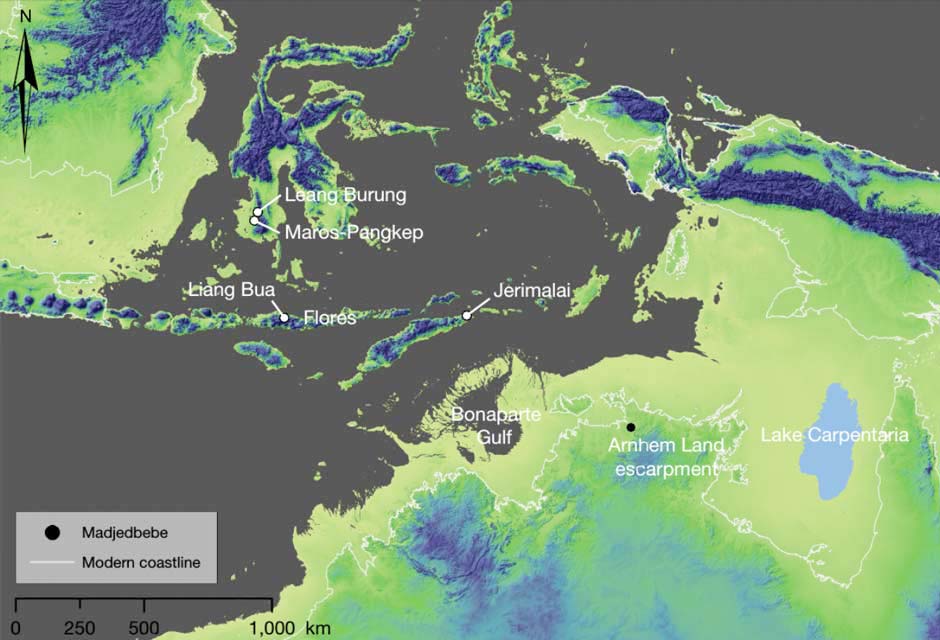

The island bridge that existed between Sundaland and Sahul at a time of lower sea levels 65,000 years ago (Map courtesy of Clarkson et al 2017 who found the remains of early humans at the once inland site of Madjedbebe in Arnhem Land)

The early occupation of Sumba is evidenced by the discovery of Palaeolithic stone tools at the Langang Pamalar site in West Sumba (Jatmiko 2017). As is common with such finds in eastern Indonesia, such tools are seldom found in combination with human fossils or with features indicating human activity (Jatmiko 2006, 163). The one exception is Liang Bua cave in Manggarai on nearby Flores, where 46,000-year-old human teeth have recently been discovered.

The Neolithic

At some time around 2000 to 1500 BCE – a more precise date is yet to be determined - the indigenous Melanesians of Sumba were joined by Neolithic Austronesian-speaking Malays (Bellwood 1997; Spriggs 2003). They would have most likely been skilled at fishing and foraging, making pottery, fashioning shells, making barkcloth and spinning and weaving (Spriggs 2011). According to various local legends, they made their first landfall on the northern tip of Cape Sasar. One story tells how the first ancestor arrived from the sky with a horse and settled at Wunga, which is today known as the ‘first village’, while a second came later by boat. Another says the first ancestors arrived over a stone bridge that connected Cape Sasar to Sumbawa. Geographically it seems likely that the new arrivals would have set sail from either Sumbawa or Flores.

Local languages on Sumba contain a high proportion of words (65%) that cannot be traced to proto-Austronesian, indicating that indigenous languages were not fully replaced during the initial expansion of Austronesians on Sumba (Lansing et al 2007). Climate and population density data suggest that eastern Sumba remained sparsely populated during this expansion, and that new agricultural communities were relatively isolated. This contrasts with wetter western Sumba where expanding farmers likely came into contact with a larger indigenous population who spoke non-Austronesian languages.

A detailed study correlating variations in the genetic structure of the male Y-chromosome with the regional languages spoken by 352 men from 29 localities on Sumba Island was undertaken in 2007 (Lansing et al 2007). The study found two strong correlations:

- firstly between the percentage of Y-chromosome lineages that were Austronesian as opposed to Melanesian/Papuan and the retention of proto-Austronesian cognates (words with a common origin) in the local language, thus demonstrating that people’s genes and their languages evolved together, and

- secondly between the percentage of proto-Austronesian cognates in the local language and the geographic distance from where the first Austronesians are believed to have arrived.

Consequently the highest percentages of proto-Austronesian cognates were found at the three sample locations closest to Cape Sasar – Wunga, Rambangaru and Kanatang.

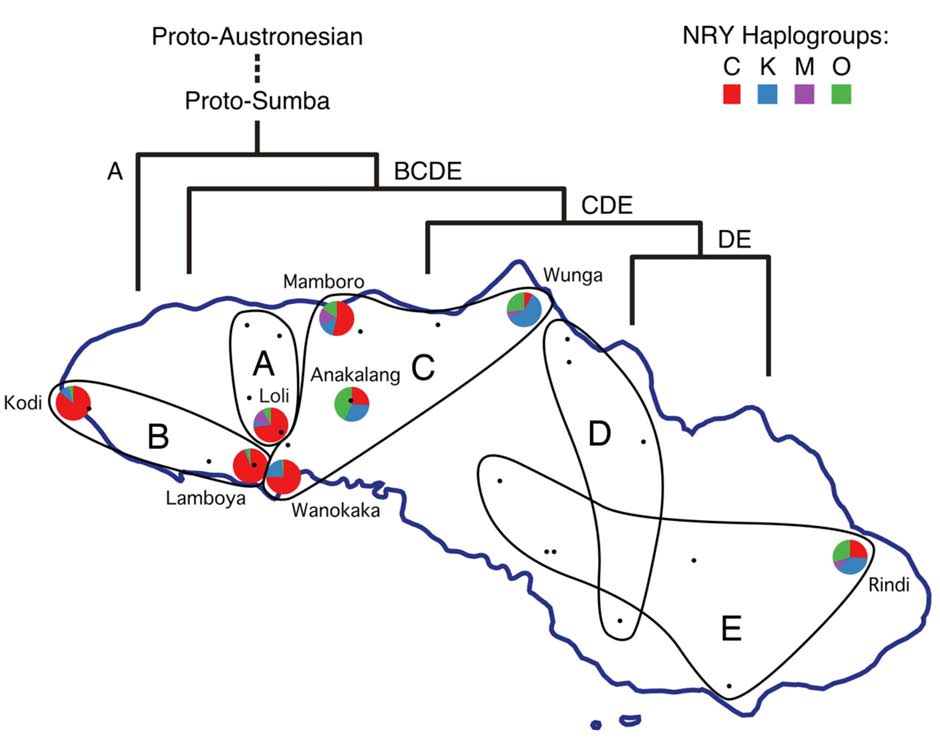

Geographic distribution of language groups and four Y-chromosome haplogroups on Sumba

(From Lansing et al 2007)

The researchers interpret their findings by proposing that after settling near Wunga, the ancestral Austronesian population expanded southwestward toward the centre of the island. The first population to split away led to the creation of group A in the northwest, which may have occurred before the main Austronesian population expansion to the south. The latter must have at least reached the centre of the island by the time group B separated and moved into the southwest. The expansion to the east occurred later and divided into two, groups D and E, probably after the main population (represented by group C) expanded to occupy the central section of the island.

A record of this sequence of dispersal appears in a ritual panggecango, or set of oral couplets from West Sumba recounted by Janet Hoskins (1997, 33):

The ancestors of long ago

Came to the distant cape of Sasar

From another land, the foreign land

The forefathers of ancient time

Came to the adze-shaped stone bridge

From across the seas, the strange land

When dawn came over Gaura’s coast

When day broke on Lombo’s land

Off to Kodi went Lord Ngedo

And to Rara went Lord Wango

…. to Ede ….and Manola

…. to Manekka ….and Lombo

…. to Karendi, Bukambero, Weyewa

…. to Gaura and Lamboya

…. to Rua and Wanokaka

…. to Lauli and Lawonda

To Kambera of different speech

…. to Melolo and Kabata

…. to Laura and Tana Righu

This phased Austronesian expansion must have involved a high degree of contact and intermarriage with the larger aboriginal population because there is a generally low and uneven distribution of a specific marker (haplogroup O) that is associated with the newly arrived Austronesian immigrants.

Melolo Neolithic or Palaeometallic Cemetery

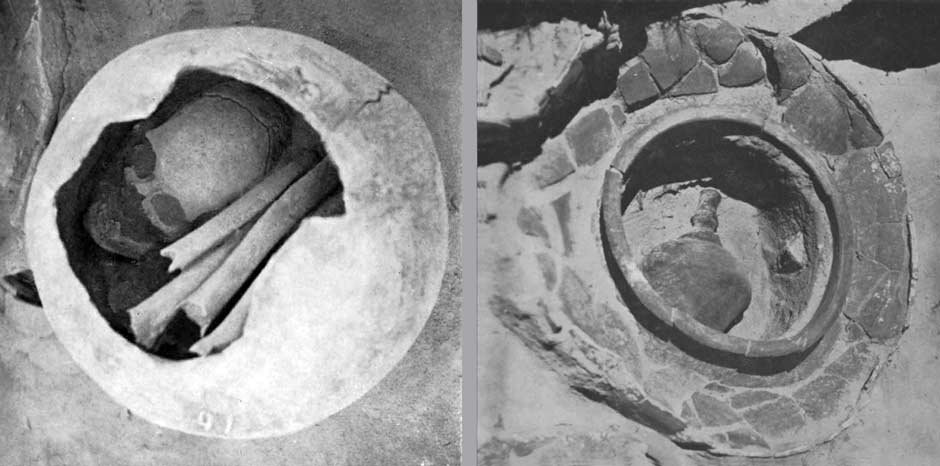

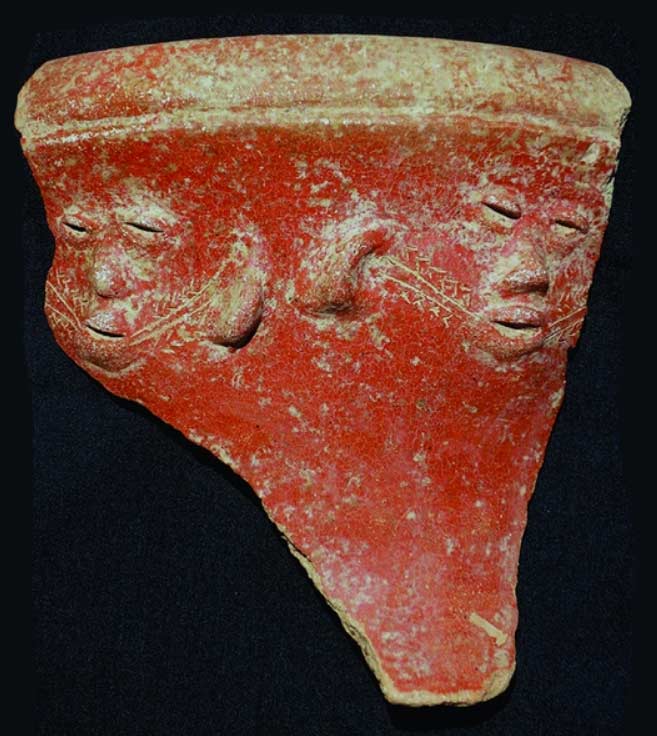

At some time during the first millennium BCE, the residents of Melolo in East Sumba adopted a ritual of secondary burial, interring the skulls of their dead in ceramic urns. The urn field at Melolo, just 10 metres above sea level, has revealed hundreds of large globular burial jars covered by a smaller upside-down pot. Most contained just a single skull, but others contained the skulls of several individuals and/or long limb bones. The dead had clearly been allowed to decompose before some of their bones had been recovered for secondary burial (Heereken 1958). The burial gifts placed in the urns consisted of beads made of seashell and stone, bracelets and rings made of seashells, a shell pendant, rectangular stone adzes and pottery and ceramic spindle whorls (Widianto 2006, 180). Some small highly polished long neck flasks with incised designs were also found.

Melolo Cemetery. Left: Urn with skull and long bones; right: urn containing a funeral gift

(Heereken pls 33 and 34, 1958)

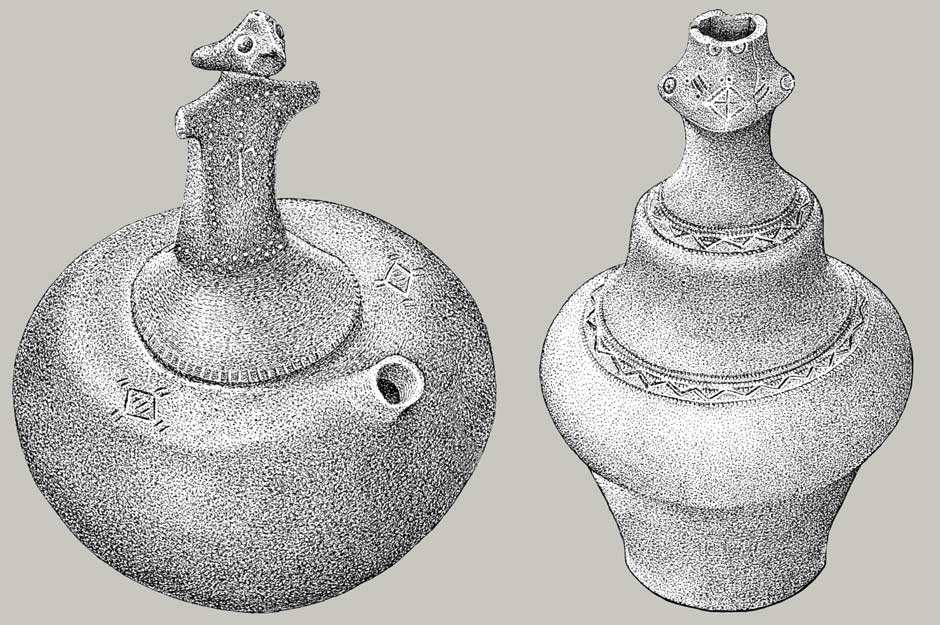

Finds from Melolo cemetery. Left: earthenware flask with human figurine and spout; right: earthenware flask with incised human face and geometric bands (Heereken figs 24 and 25, 1958)

A shell pendant recovered from the Melolo urn field

(Heereken fig. 23, 1958)

The Melolo site was first excavated by A. C. Kruyt in 1908, then by L. Dannenberger and Ernst Rodenwaldt in 1923, by K. W. Dammerman in 1926, by L. Onvlee in 1936 and by W. J. A. Willems in late 1939 (Van Heekeren, 1956; 1958, 85-86). Van Heekeren used Willems field notes to write an overview of the Melolo urn field (1956). Dannenberger and Rodenwaldt transferred the bones of 34 individuals recovered from the excavation to J. P. Kleiweg de Zwaan and C.A.R.D. Snell for anthropological analysis in Surabaya. They were found to be a mixture of Negroid Melanesian and Malay – in other words, the original Papuan population living alongside later Austronesian-speaking immigrants.

Several other jar burial sites have been identified in this region. On Sumba a somewhat similar urn burial site with jars containing worked shell ornaments and other shell artefacts has been located at Lambanapu, just south of Waingapu (Bulbeck 2017, 150). Another has been excavated at Pain Haka on the coast of East Flores, identifying 48 primary and secondary burials, 13 with remains interned in ceramic jars (Galipaud et al 2016). Other pots and flasks were buried alongside as grave goods, one decorated with a human face. The site is classified as Neolithic, dating from around 1,000 BCE. Two other sites have been located at Lewoleba and Waibau on Lembata Island (Bulbeck 2017, 150-157).

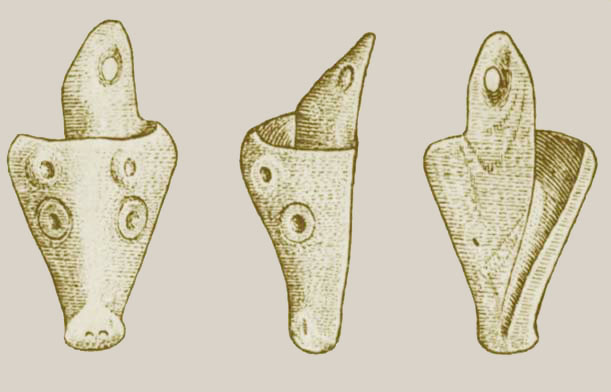

A small carinate-shaped burial pot incised with a human face from Pain Haka (Galipaud et al 2016)

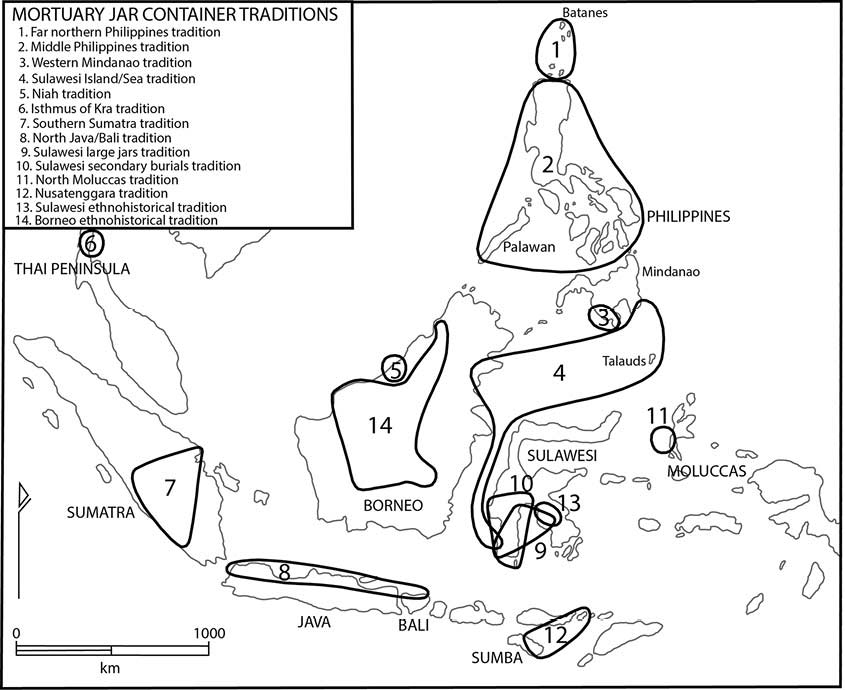

The cult of urn burial was once widespread throughout and beyond the Indonesian Archipelago. Bulbeck has recently classified a number of mortuary urn burial sites regionally, grouping Sumba, East Flores and Lembata as Nusatenggara (2017, 157). Bulbeck considers the sites in the Philippines and Borneo to be Neolithic, and those in Sulawesi, Sumatra, Java, Nusatenggara and Maluku to be Palaeometallic (Early Metal Age), dated to the period a few centuries before or a few centuries after the start of the Christian Era. This corresponds to a time of expanding trade linkages across the archipelago, with Dongson bronze ware arriving from as far away as northern Vietnam.

Twelve regional traditions of urn burial identified by Bulbeck 2017, 157

‘Nusatenggara’ is classified as Melolo, Lambanapu, East Flores and Lembata

Bulbeck dates the Melolo site to the early Palaeometallic because of the presence of kendi kettle-like flasks, which Bellwood considers a chronological marker. Earlier both Willems (1940) and Von Heine Geldern (1945) dated the site to the Early Metal Age, approximately some time after 500 BCE. However the absence of any metal objects has left some doubting as to whether the site dates from the Palaeometallic or the earlier Neolithic, roughly 2000 to 200 BCE (Soejono 1984). Interestingly nearby Pain Haka has been dated to 1000 BCE in the Neolithic.

Whatever the dating, the practice of urn burial on Sumba and elsewhere reflects a profound ideological change in perceptions of the world and afterlife (Galipaud et al 2016). Some have suggested that these jar burials may represent the antecedents of the practice of interring the deceased in large megalithic tombs that persists on Sumba today. The inclusion of prestige items such as stone and shell beads and shell bracelets is no different from the practice of placing the deceased in megalithic tombs with gold and prestige textiles.Return to Top

The Early Historical Period – Sandalwood and Slaves

Little is known about pre-colonial Sumba - outsiders were probably only interested in its slaves and sandalwood. With its rigid social hierarchy, the ruling families of Sumba’s numerous regional domains owned extensive tracts of land, large herds of livestock and held sway over sizeable numbers of slaves. Sporadic inter-tribal warfare and headhunting ensured a regular supply of captives whose export, along with sandalwood, further boosted the wealth of the ruling elite. Early European sources portrayed Sumba as an island in turmoil, with no centralised power and authority based on the survival of the fittest. Inter-clan rivalry and incessant headhunting raids required villages to be located on hilltops and heavily fortified. Heads became tokens of territorial conquest in battles between rival nobles and were displayed on village 'skull trees'.

Accounts from China

While we have no historical accounts of early maritime trade with Sumba, we do know that sandalwood has been exported from ‘Timor’ for several millennia by a mixture of Arab, Indian, Malay and Chinese merchants. As we shall see later, ‘Timor’ was once a loose term that may well have included Sumba. The Chinese greatly valued sandalwood and probably traded directly with the islands on which it grew, until the collapse of the navy during the Ming Dynasty. As early as 357 CE a Chinese record mentions a country in the Indies whose name transliterated as cendana or sandalwood, a name that was applied to Sumba by the first European explorers (Donkin 2003, 23).

The Inspector of Overseas Trade, Chau Ju-Kua, listed the Chinese sources of sandalwood in 1225 (Ptak 1983; Donkin 2003, 160):

Sandalwood comes from the two countries of Ta-kang [an unidentified island that was a dependency of Sho-p’o or Java] and Ti-wu [Timor], it is also found in San-fo-ch’i [Palembang] ....

Srivijaya/Palembang had previously controlled the shipment of sandalwood through the Malacca Strait to China and India from perhaps the 7th to the 11th century (Gunn 2016,127).

The Daoyi zhilue, written around 1350, added that (Ptak 1987, 32; Ptak 1999, xiv):

This country [Chi-li Ti-men or Timor] lies to the east of Chung-chia-lo [Sumbawa?]. Its mountains are covered in thick forests, all sandalwood. It produces nothing else. There are twelve trading ports. There is a tribal chief.

Up to around 1400, sandalwood was being shipped to China by both Chinese and non-Chinese merchants on shipping lanes that ran through Sulawesi, Maluku and the Philippines (Ptak 1999, 94).

Majapahit Java

In 1292 the Hindu Majapahit state emerged from the former kingdom of Singhasari in the Brantas Valley of Eastern Java. As it gained economic and military strength on the back of rice culture and maritime trade it began to extend its influence eastwards. In 1343, following a long military campaign, the Majapahit grand-vizir Gajah Mada finally subjugated Bali turning it into a vassal state. Some years later he led a powerful naval expedition eastwards, ‘conquering’ much of Nusantara. His commander Sir Nala arrived in Dompo (Sumbawa) in 1357 (Pigeaud 1962, IV, 216). The Nāgara-Kěrtāgama chronicle, written in Bali in 1365, lists those countries east of Java that were supposedly tributaries of Majapahit. Stanza 5 of Canto 14 lists Kunir [Kunit], Galiyao [Pantar and west Alor] and Salaya [Salayar, south Sulawesi], Sumba, Solot [Solor, Adonara, East Flores?] and Muar [West Seram?] (Pigeaud 1960, III, 17; Pigeaud 1962, IV, 34).

Carving of a Javanese sail boat with outriggers, Borobodur, ninth century CE

It is highly unlikely that Majapahit Java held much sway over distant lands like Sumba. However there must have been interconnecting trade. From around 1400 onwards Javanese, Muslim and Malay merchants increasingly shipped sandalwood to Malacca, from where it was loaded onto Chinese and Indian vessels for onward transhipment (Ptak 1999, 87-92).

It has been suggested that horses may have been introduced from Java to Sumba sometime after the fourteenth century once they became common on Java (Hobgen 2015, 68).

The Portuguese

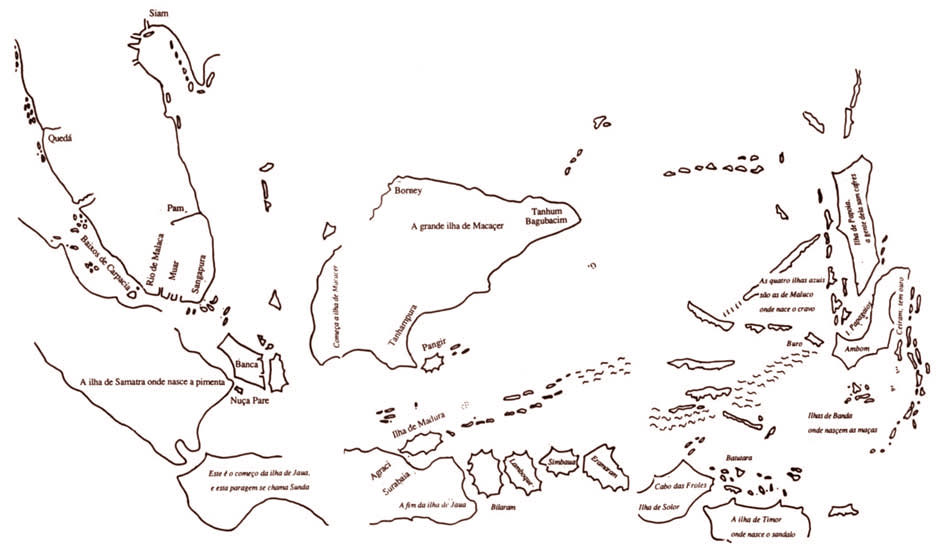

In 1511 Afonso de Albuquerque set sail from Cochin with 19 vessels to conquer Malacca, which controlled a strategic maritime trade route. After securing the town he despatched three ships under the command of Antonio de Abreu to explore the eastern Spice Islands. They sailed along the northern coasts of Sumatra, Java, Sumbawa and Flores on their way to Ambon and Banda. On their return their pilot, Francisco Rodrigues, prepared a set of sketched charts depicting many of these islands including Timor (‘where sandalwood grows’) but not Sumba, which could only be seen from the southern coast of western Flores.

Assemblage of four sketches from Francisco Rodrigues’ unfinished Book and Atlas

(Rodrigues 1511-1515, from Thomaz 1995, Plate III)

Fortunately the Portuguese naval apothecary and factor Tomé Pires left us with a better oversight of the islands. His Suma Oriental was mainly written in the port of Malacca, where he was posted from 1512 to 1515 (Pires 1944, lxii). Pires only sailed as far as Java, in 1513, so most of his information must have been gathered from other mariners, including Rodrigues. Pires reported that there was a wide channel between Sumbawa (which he called Bima) and Flores (Solor), which was used by Malay merchants to reach the ‘sandalwood islands’ (1944, 203-204). The sandalwood was shipped back to Malacca. Although the term Timor was applied to all the islands east of Java, the expression ‘the Timor Islands’ generally referred to the two most important - the sandalwood islands - which had a great deal of sandalwood and were ruled by ‘heathen kings’ (Pires 1944, 204). These islands were Sumba and modern Timor.

It was not only sandalwood that was being exported from ‘Timor’. The Portuguese mariner Duarte Barbosa, a cousin of Magellan, sailed to Maluku in 1512 and found that vessels from Java and Malacca were not only going to the islands of Timor to obtain sandalwood, honey, and wax but also slaves (Barbosa 1866, 192). This must have been an important trade that had been established long before the arrival of the first Europeans.

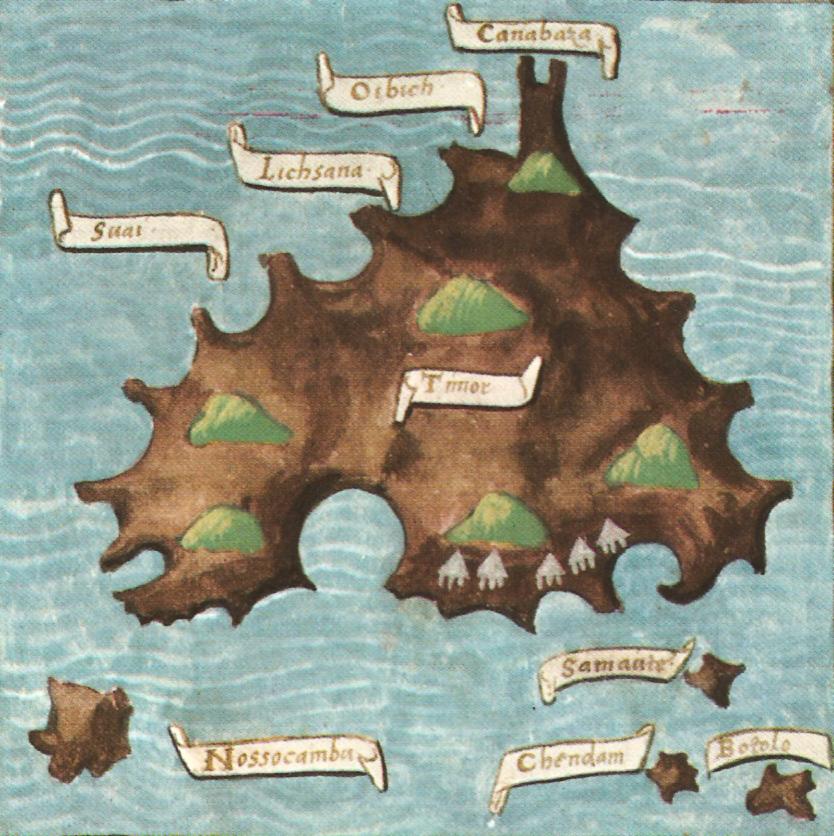

After circumnavigating half the globe and losing his life on the way, Magellan’s only surviving ship Victoria left ‘Balibo’ on Timor on the 11 February 1522 for the Cape of Good Hope, heading west-southwest to the south of Sumba before keeping well away from Portuguese Sumatra (Pigafetta 1906, II, 181). The ship’s chronicler Antonio Pigafetta sketched a distorted upside-down map of Timor showing four neighbouring islands, Nossocambu (Kambing Island), Botolo (possibly Rote), Samante (Semoa) and Chendam (Pigafetta 1906, II, 167). Some, including Gerrit Rouffaer, have since proposed that Chendam was Sumba Island - Cendana or Sandalwood Island (1899, 625). In our opinion it is more likely to be Savu.

Distorted chart of the island of Timor with of its four settlements, and four other islands - north is at the bottom (from Pigafetta 1906, II, 167, and colour enhanced)

The first Portuguese expedition to ‘Timor’ took place in 1514 and merchants soon began exchanging Malacca cotton cloth for sandalwood, honey and wax (Paulino 2012, 90). The natives were happy to trade freely without any need for the Portuguese to establish a strong military presence (Wallys Diffie 1977, 370-372). They did establish forts on Ternate in 1523 and started another on Banda in 1529, which was never completed. Their level of contact with Sumba remains unknown, although they must have traded with the island and apparently also built a fort near the mouth of the Tidas River in Lewa Tidahu on the southern coast of West Sumba, although its dates and use remain a mystery (Roo 1906, 188; Hoskins 1997, 34-35).

The Portuguese were adventurous mariners and it probably did not take long for them to discover Sumba and Savu. One of the eight sea maps produced by the Portuguese cartographer Bartholomeus Laso in 1590 shows an unnamed island in the location of Sumba laying west of Timor and south of Flores.

The map of Bartholomeus Laso, 1590

(W. A. Engelbrecht Collection, Rotterdam)

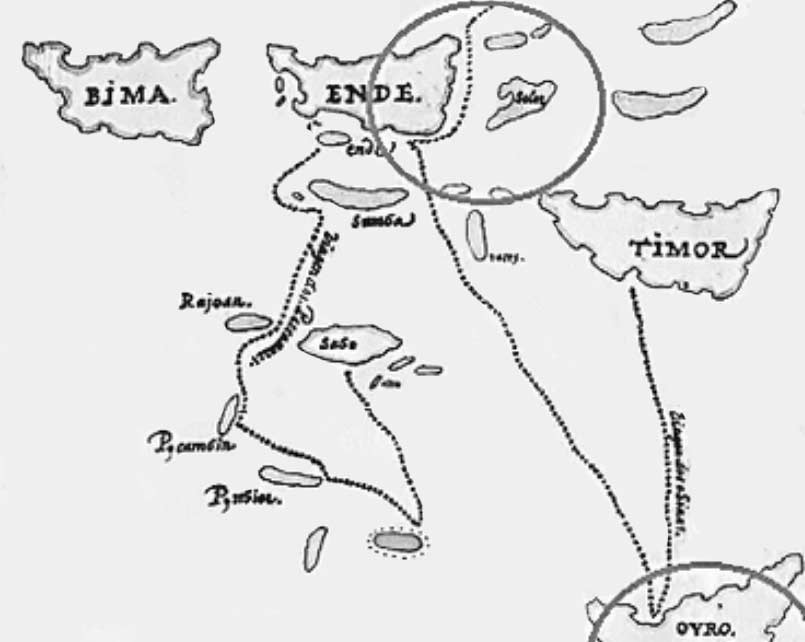

A 1602 map produced by the leading cartographer Godinho de Eredia even charts a voyage from Ende Island via Sumba and Raijua to the remote Scott and Seringapatam Atolls that lie between Indonesia and Australia.

Detail from a map showing a voyage to Scott and Seringapatam Atolls

(Emanuel Godinho de Eredia, 1602)

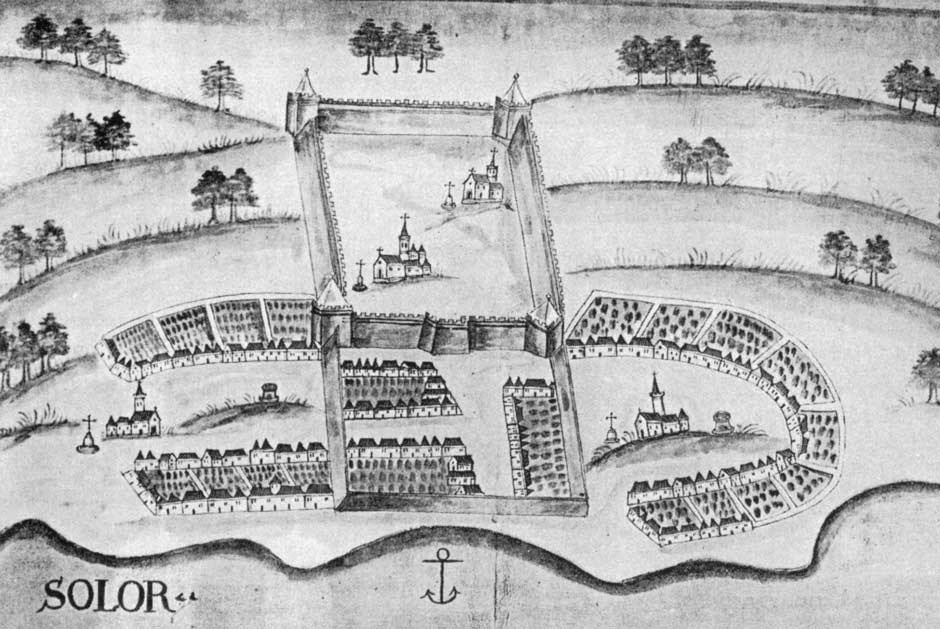

In 1562 the Portuguese Dominican Order built a fort on Solor Island, a convenient staging post on the maritime route to Timor. In time a mixed race community of so-called Black Portuguese grew up around the fort, some of who moved to Larantuka on east Flores in 1598.

The Portuguese Fortazela on Solor Island

The latter became increasingly involved in Timor, where they became known as Topasses, intermarrying with the native ruling families to establish their own powerful domains and gaining control over the trade in sandalwood, beeswax and slaves. From later reports they must have also had a limited involvement with Sumba. Although the trade in sandalwood was probably modest, it was highly profitable and continued to expand through to the 1630s (Subrahmanyam 2012). As the wealth of the Topasses on Timor Island grew they began to eclipse the power of the native rulers and the white Portuguese.

The Arrival of the Dutch

In 1568 the Protestant Dutch provinces, led by William of Orange, began their long struggle against Spanish Habsburg rule. After uniting in 1579 they declared independence from Spain in 1581. During the 1590s the United Provinces began to seek trading opportunities in the East Indies, bringing them into conflict with Habsburg Portugal which had been subjugated by Spain in 1580. In 1602 the Dutch formed the powerful Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC, a quasi-governmental trading company that would fund exploratory voyages, establish trading agreements with local rulers and construct military bases. It would also rely heavily on slave labour – throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century Batavia would host one of the most important slave markets in Asia (Needham 1983, 4).

In 1613 a Dutch fleet, assisted by troops from Ternate, laid siege to the Topass fort on Solor for three months. Instead of fleeing to Malacca the defeated Topasses were allowed to join their compatriots at nearby Larantuka. The Topasses made several attempts to regain the fort on Solor, but the Dutch prevailed. From their new base on Solor, the VOC jealously eyed the lucrative sandalwood trade.

Despite this setback the seafaring Topasses continued to strengthen their hold over Timor, finally overthrowing the leaders of Wehali, the island's predominant rulers, in 1642. In doing so they gained a greater degree of control over the Timor sandalwood trade, although the Makassarese, Malays and Islamic merchants still continued to visit the island (Villiers 1985, 77).

It is possible the Dutch had scanty knowledge of Sumba prior to 1636. In that year one of its schooners, the Maria, was shipwrecked on Sandelbosch Eyland (Ross 1906, 188). Its latitude was 10° 30’ south, further south than Timor. Initially the VOC showed no interest in the island. A report of 1650 noted that Sumba was under Makassarese control and that its slaves were excessively expensive (Hägerdal 2012, 94).

The Sultanates of Makassar and Bima

During the sixteenth century, the dual kingdom of Gowa and Talloq in South Sulawesi had become increasingly powerful and Makassar had developed into an important commercial town, free port, and trading entrepôt for rice, sandalwood and slaves, the latter captured on the coasts of Borneo, Sulawesi, Buton and the Lesser Sunda Islands (Gaynor 2017, 67). In 1605 ulamas from Minangkabau succeeded in converting its ruling families to Islam.

The Sultanate of Gowa decided to extend its authority southwards, attacking Bima on Sumbawa in 1618, 1619 and again in about 1630 - in the later case with a fleet of 400 vessels (Cummings 2010, 8 and 12). Bima was finally forced to submit to its authority in 1633. Previously Bima had extended its influence eastwards into Manggarai on Flores and southwards to northern Sumba, especially Mamboro, where there had been long-term contacts and trade, probably involving the export of slaves and sandalwood. Bima clearly regarded Sumba as falling within its sphere of influence. A VOC report of 1650 noted that Sumba sent tribute to Gowa and Talloq as an acknowledgement of its subordinate status (cited by Andaya 2011, 127). There is even an oral memory on Sumba of a Bimanese viceroy settling in the fifteenth century (Hoskins 1997, 38).

Although the Dutch initially used the port of Makassar, relations deteriorated – Makassarese merchants continued to trade directly with Banda. In 1636 the Dutch blockaded the harbour for several months until a peace treaty was signed (Lubis 1990, 108). Since Makassarese merchants were also successfully sourcing sandalwood directly from Timor, the VOC agreed to obtain its supplies from them. In response the Sultan of Gowa led a fleet of over 5,000 men to destroy the Topass base at Larantuka, going on to ravage the coast of Timor for slaves (Hägerdal 2012, 85). However on his return to Makassar, the Sultan was assassinated by his wife. His initiative to eliminate the Topasses from the sandalwood trade soon lost momentum.

The Dutch Dislodge the Portuguese

The Dutch had already gained control of the Straits of Malacca in 1635 after having displaced the Portuguese from Acheh (Freeman 2003, 98). In 1641, just as Makassar was attacking Larantuka, the heavily fortified Portuguese port of Malacca finally capitulated to the Dutch following a seven-month siege. The Dutch had gained a vital strategically located trading centre. Having lost their primary centre of operations in Southeast Asia, some 20,000 Portuguese and their associates were forced to transfer their trading activities to Makassar, giving it a new role in the spice trade (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 61).

The port of Malacca under Dutch rule 1665

Gezicht op de stad Malakka van de zeezijde, Johannes Vingboons, Amsterdam

(Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence)

Further east, the Topasses of Larantuka and the Sultan of Gowa still remained powerful commercial threats to the Dutch. Fearful that the Topasses would turn Larantuka into a second Malacca, the Dutch strengthened their garrison at Fort Henricus on Solor in 1646 (Hägerdal 2003, 92-93). Yet there were few commercial opportunities in the surrounding islands. Hendrick ter Horst, the Dutch opperhoofd on Solor, saw a chance to take a share of the Timorese sandalwood trade.

The Dutch had found a potential ally in the King of the Helong at Kupang who was under threat by the Topasses in alliance with parts of the Sonbai tribal confederation. With the help of the Helong the VOC built a simple fort on a site overlooking the Bay of Kupang in 1653, garrisoning it with 25 troops and naming it Fort Concordia. After several local skirmishes, the VOC mounted several poorly planned campaigns against the Topasses and their allies, especially the Amarasi, in 1655 and 1656 but failed on each attempt. Thoroughly defeated the Dutch briefly considered moving to the more friendly location of Rote but decided to stay, finally relocating their headquarters from Solor to Kupang in 1657 (Hägerdal 2012, 7). For unknown reasons Batavia seems to have lacked the will to send sufficiently large forces to deal with the Topasses once and for all (Hägerdal 2012, 126). In desperation the VOC attempted to negotiate a sandalwood supply agreement with the Topasses, but the latter refused to do so unless the Dutch vacated Kupang (Schulte Nordholt 2013, 172).

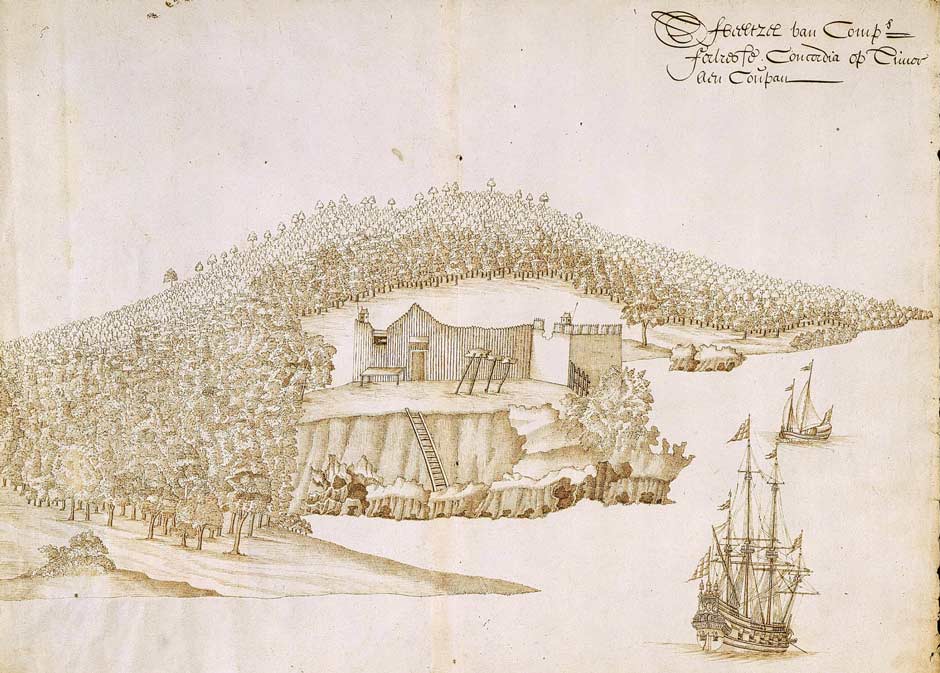

A sketch of tiny Fort Concordia at Kupang around 1656

(Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence)

The Dutch were to have greater success against their other commercial foe. Angered at Makassarese merchants continuing to source spices directly from Banda, Batavia decided to mount a direct strike on their homeport (Van Insselt 1908). In 1660 a Dutch fleet of 35 vessels commanded by Johan van Dam set out from Ambon to bombard Makassar. As it headed for the Straits of Larantuka, local Topasses sought refuge on Ende Island. After a sea battle the VOC occupied a fort to the south of the city and the Makassarese sued for peace.

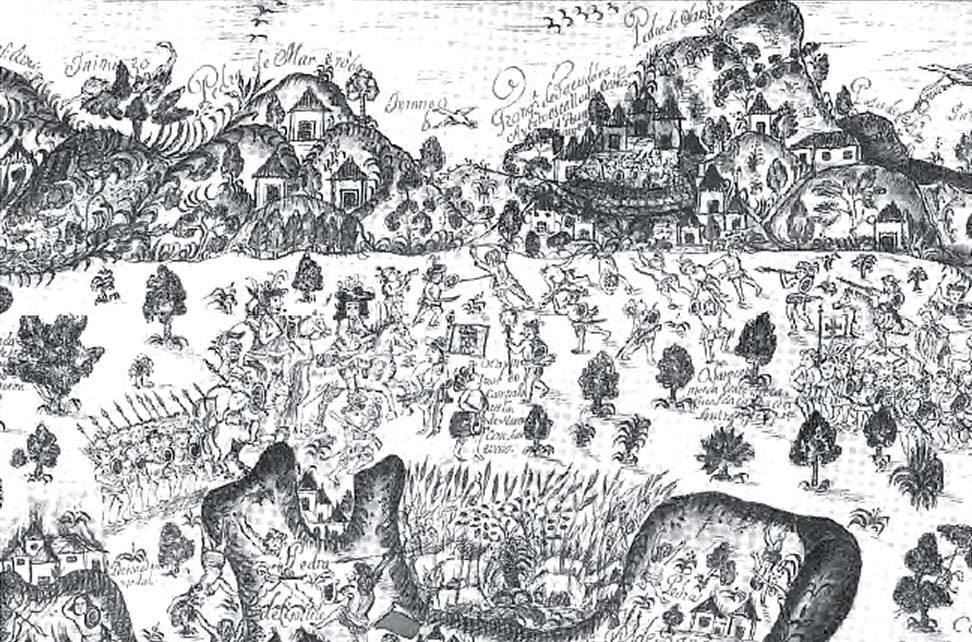

Two scenes from the VOC attack on Makassar on 12 June 1660

(Woulter Schouten 1676)

The bombardment of Makassar left many of its local merchants and slave traders in a state of anxiety. In January 1664 they despatched one thousand men in a fleet of 28 ships from Makassar to Ende on Flores to protect its inhabitants from oppression by local Topasses. These were soon joined by a further 8 ships carrying 500-600 men (Roo 1906, 242; Parimartha 2008, 73).

Meanwhile relations between the VOC and Makassar continued to deteriorate until in 1666 the VOC launched a full-scale war against Makassar that concluded in 1669 with the Sultan agreeing to withdraw from the spice trade and give up any territorial claims on the islands east of Lombok (Latch and Van Kley 1998, 1442). After a brief treaty two more campaigns followed, in 1667 and 1669, after which the Sultan was deposed, the Portuguese were expelled, and the VOC constructed Fort Rotterdam. It would become the centre of Dutch power on Sulawesi.

More immigrants arrived from south Sulawesi after 1671, many settling at Ende and on Sumbawa (Needham 1983, 18). Over the following years many of these Makassarese immigrants intermarried with other Moslems living in the Bay of Ende to form a new coastal Endenese community.

Sumba

In 1662 the Sultan of Bima again attempted to reassert his authority over Sumba, where the Topasses were entrenched in its modest sandalwood trade. Malay traders had delivered a cargo of Sumbanese sandalwood to Batavia, greatly irritating the Sultan who claimed it was his property because Sumba had been under the control of Bima ‘of old’ (Roo 1906, 189). The Sultan asked the VOC to refrain from sourcing sandalwood from the island until he had subdued the rebels. He offered the VOC a permit to take sandalwood from the island in return for their assistance. None was forthcoming and his threat of intervention came to nothing. Bima’s claims over Sumba need to be treated with caution – although Bima wanted to maintain the share of its trade with Sumba it lacked the resources to tame such a wild and unruly island.

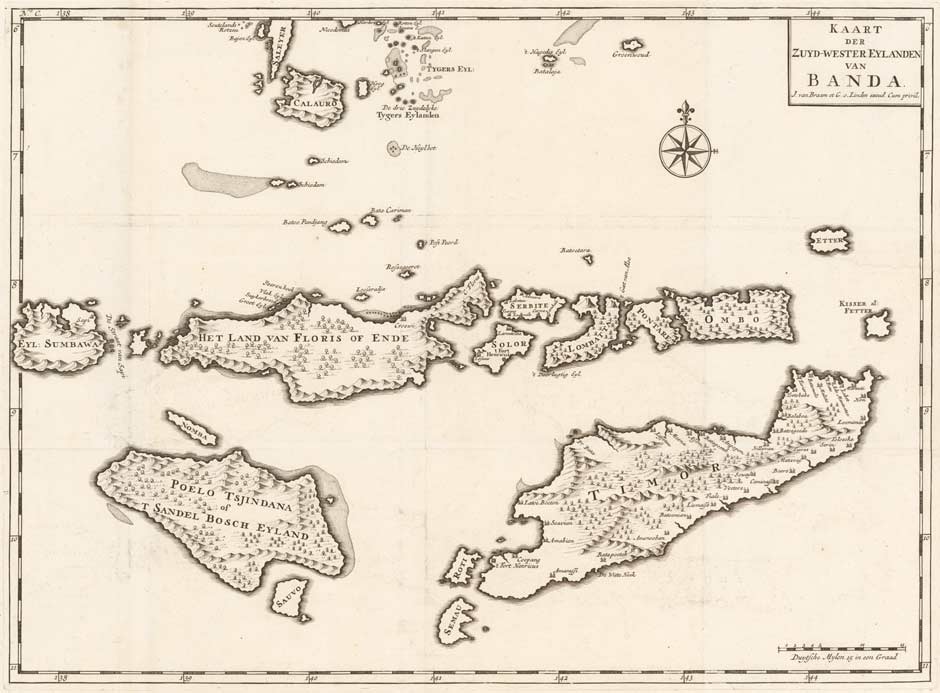

An anonymous map submitted by Arnold de Vlamingh van Oudtshoorn in 1656 double mapping Sumba Island as Nomba and Sandalenbos (Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam)

As the VOC merchant Michiel van Heijst was about to set off from Kupang to Batavia in 1675, he was diverted to Bima on a diplomatic mission. The Sultan offered the VOC a supply contract of Sumbanese sandalwood, to be collected from either Sumba or Bima, provided the VOC rescind any territorial claims over Sumba, Savu, Manggarai and Solor, which he claimed had been in the ownership of Bima from ‘olden times’ (Roo 1906, 190-191). Nothing transpired. When the VOC finally visited Sumba around 1685, they apparently found little sandalwood growing and that available was of low quality (Hägerdal 2012, 177).

Some of the Makassarese who had settled at Ende were slave merchants and they soon turned to nearby Sumba for an alternative source of their human merchandise. A VOC report of 1678 mentioned that ‘the Ende’ were sailing to Sumba every year, especially to the haven of Mamboro (Hägerdal 2012, 177).

Much of our understanding about the history of Sumba from around 1650 to 1900 is thanks to J. de Roo van Alderwereldt, who was the civiel gezaghebber – the most senior colonial official – on Sumba from 1885 until 1888 (Van den End 1987, 684). Having had full access to the Dutch archive in Kupang, he later researched aspects of the island in detail, publishing works in 1890 and 1891 on its culture and language, and in 1906 on its history in his seminal study Historical Notes about Sumba. Of course his comments reflect the views of the Dutch colonial authorities and not those of the native people or of the other powers competing for Sumba’s resources.

Sumba in the Eighteenth Century – Early Dutch Contacts

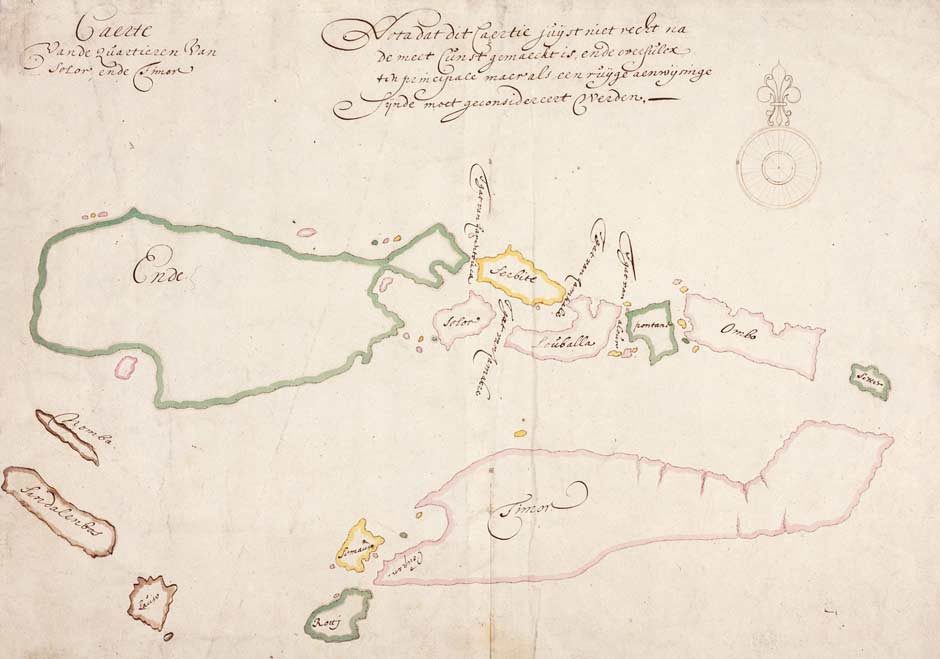

By 1700 the Dutch had a much better understanding of the location of Sumba Island but still understood almost nothing about its nature. A map included in the eight-volume Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien prepared by the VOC pastor and naturalist François Valentijn, published in Amsterdam, shows a slightly more accurate rendering of ‘Sandel Bosch Eyland’ but still contains many errors, misplacing Savu and still including the phantom island of Nomba.

Kaart der Zuyd-Wester Eylanden van Banda, folio 36, 1726

The absence of VOC interest in the island left it wide open to all-comers. In 1708 the Topass leader Domingos da Costa on Timor was offered the position of capitan of Larantuka and of Sumba but declined, in the latter case because the island was in constant revolt (De Matos 1974, 115). Despite this he did send a mission to Sumba in 1718 to intervene in a local dispute (Needham 1987, 5; Hägerdal 2010). This action coincided with the news that at least one of the rulers on Sumba wished to submit to Portugal (Oliveira Marques 1998, 513). This must have been Umalulu.

After Hendrik Engelburt was appointed opperhoofd (chief) of the VOC at Kupang in 1721 he concluded that Sumba might provide an opportunity for profitable trade. In his report of 1723, Engelburt revealed that the ruler of Mangili had sought the assistance of the VOC regarding his dispute with the ruler of Umalulu (Melolo), who was under the influence of the Portuguese based in Larantuka (Kapita 1976, 146). However his request to establish a presence on the island was rejected by the Hoge Regeríng, the supreme governing body of the VOC in Batavia. A subsequent report of 1726 confirmed that the Topasses had formed an alliance with Umbu Nggaba Haumara, the ruler of the Umalulu coast of Sumba, for the supply of sandalwood (Roo 1906, 193-194).

Topasses led by Francisco de Hornay suppressing a major tribal rebellion in East Timor in 1726 (Planta de Cailacao, 1727, Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Lisbon)

Meanwhile on the north cost of Sumba, Islamic Endenese merchants – still closely linked to Makassar – continued their lucrative raids along the north coast of Sumba, and also Sumbawa and Flores, in their search for slaves (Fox 1977, 136). Some 32% of the slaves entering Makassar during the 1720s were from Sumba, while 18% were from Sumbawa and 17% from ‘Ende’, in other words Flores (Van Welie 2008, 198). These raids were small-scale incursions with a few score of human captives taken on a few dozen prauws, generally with the connivance of the local nobility.

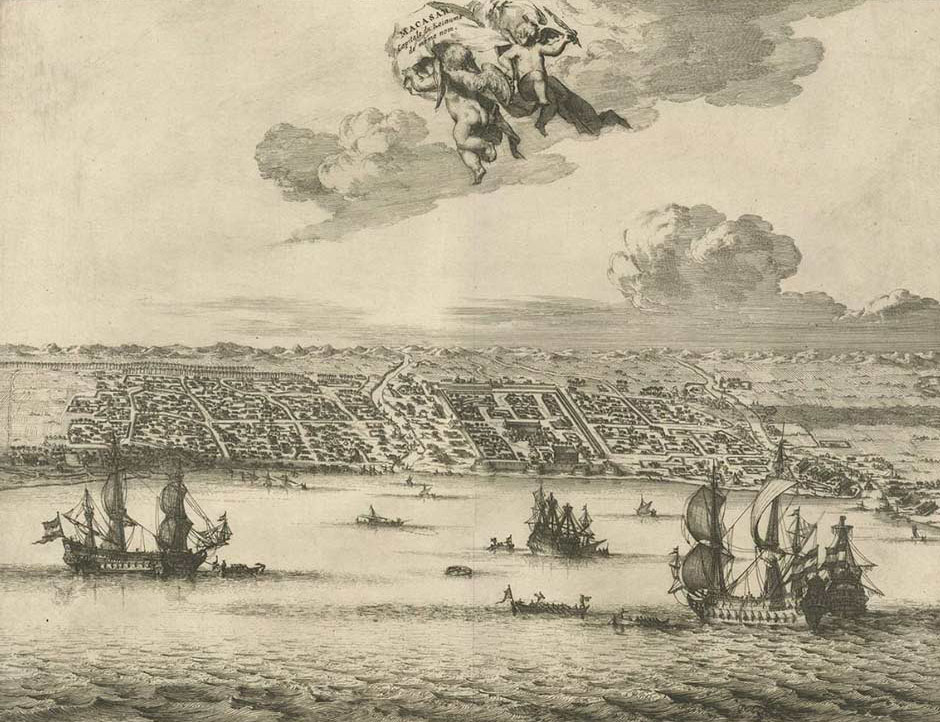

The port of Makassar, South Sulawesi, in 1725

(By Piet van der Aa, Amsterdam)

In 1749 the then opperhoofd of Timor, Daniel van den Burgh, informed Batavia that some of the native leaders on Sumba had requested VOC protection in return for an exclusive trade contract (Wellem 2004, 19). He was authorised to investigate the opportunities. After his regular annual visit to Rote and Savu, van den Burgh visited Sumba in 1751, the first senior VOC official to do so. There he met with the leaders of eight domains: Patawang, Melolo, and Mangili in East Sumba; Kapunduk, Kambera and Lewa in Middle Sumba; and Wanokakka and Sampareengoe on the south coast (Roo 1906, 196). On the basis of rather loose oral agreements they supposedly acknowledged the sovereignty of the VOC and agreed to trade with it exclusively (Wellem 2004, 19-20). Part of the contract stipulated that the Sumbanese must not allow any Makassarese traders to land on their island (Roo 1906, 243).

In 1756, concerned about Portuguese intentions on Timor, the Hoge Regeríng in Batavia despatched the VOC commissioner Johannes Andreas Paravicini on an important diplomatic mission to Kupang. There he obtained signatories on a contract of allegiance from a large number of regional leaders from Solor, Savu, Rote and Timor, including one from Sumba (Kapita 1976, 146; Fox 2003, 12; Wellem 2004, 19; Hägerdal 2012, 376-381). On 9 June Paravicini staged a solemn ceremony in which 92 regional heads swore an oath of allegiance to the banner of the VOC. The contract was supposedly signed by the eight regents from Sumba, themselves only a fraction of the island’s domains. Controversially only one of them was present at the meeting – the head of Mangili.

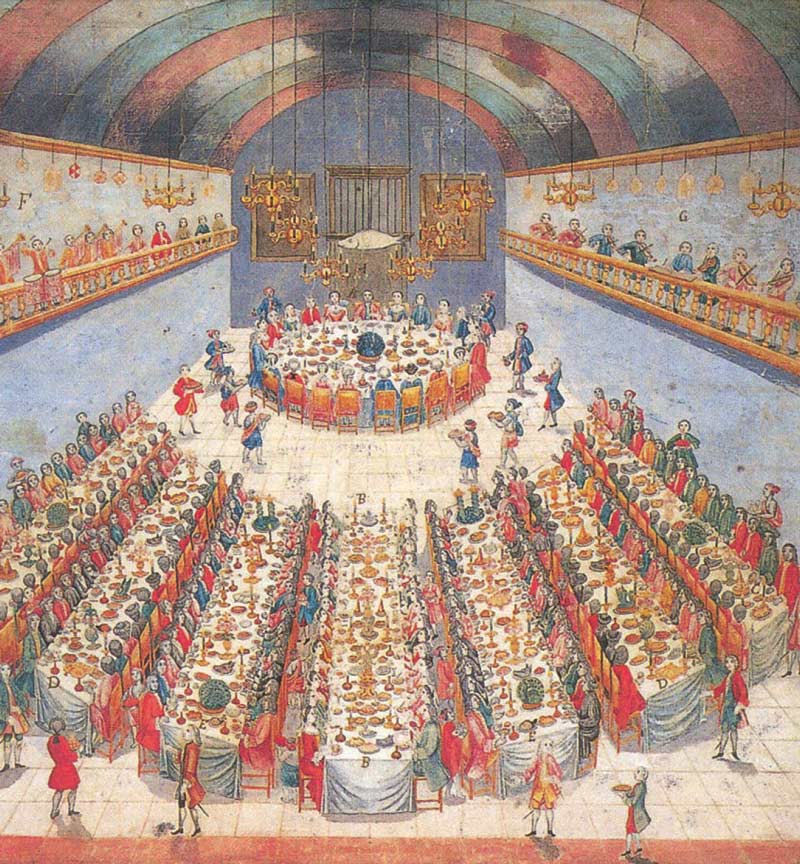

Banquet to celebrate the treaty between the VOC and the native rulers in Kupang on 10 June 1756 (An anonymous watercolour in the collection of the Tropenmuseum)

Despite having never visited Sumba, Paravicini submitted a glowing report about the island in 1757 (Roo 1906, 202-203):

"Sumba is one of the largest, most fertile and well-known islands of the East, full of inhabitants who are good soldiers, intersected with rivers navigable by ships, and its bays are full of the most precious timber to build ships and fine ropes to secure them and even provide sails. The main thing is the abundance of food, not so much today but the precious black earth could very well provide everything."

The Hoge Regeríng in Batavia responded by asking Ellis Jacob Beynon, the opperhoofd of Kupang, to investigate the situation on Sumba the following year (Roo 1906, 204-205; Kapita 1973, 22). He reported that the island was large and lightly populated but constantly disrupted by regional warfare. It would need to be pacified before it was safe to export sandalwood, cotton and slaves.

It seems that only the Topasses and the Makassarese and Endenese pirates were willing to trade with the island. Since 1753 there had been an upsurge in the arrival of slave traders on the island, the largest raid occurring in 1758 with 24 prauws capturing hundreds of people along the coasts of Kanatang and Melolo (Roo 1906, 195 note 2; Needham 1983, 38). We have no record of where these unfortunates were taken. Some ended up in the coastal Sultanates of Sumbawa, Sulawesi, Borneo and Maluku, others were sold to the VOC to work on Java or in the plantations in the Spice Islands. One report recorded that 4,000 slaves were taken to Batavia annually during the third quarter of the eighteenth century (De Haan 1935, I, 371; Fox 1980, 102).

In late 1758 the next opperhoofd of Kupang, Hans Albrecht von Plüskow, sent a mission to Sumba led by Hans Erasmus but including Gabriel Kotting, the Kupang-based brother of the Regent of Dengka from Rote Island, Bale, the district head of Kupang (who was married to the daughter of the Raja of Mangili) and a cartographer. They sailed from Kupang to Umalulu in East Sumba in October and returned on 25 January 1759 (Erasmus and Leupe 1879; Kapita 1976, 147). Their arrival at Melolo coincided with several local disputes. The Raja of Lewa had agreed to wed the daughter of the Raja of Umalulu and had paid the negotiated bridewealth in gold only for the marriage to be cancelled. The jilted Raja was preparing an attack on Umalulu and had bartered 55 slaves in return for Makassarese mercenaries who had already arrived in 18 prauws on the coast of Lewa (Roos 1906, 208-210; Kapita 1976, 146; Needham 1983, 20). In addition Lewa was in dispute with Tabundung and Melolo was in dispute with Patawang.

Erasmus concluded that no advantage could be made of Sumba while the domains were constantly at war with each other. Many of the disputes were caused by the incitement and intervention of the ‘mighty’ domain of Batu Kapedu in West Sumba, whom all the other domains greatly feared. If Batu Kapedu could be constrained then there was an opportunity to annually export a shipload of sandalwood, a good quantity of slaves, raw cotton, ebony, turtle shell, trepang (dried sea cucumber), sarongs, ropes and sail thread (Erasmus and Leupe 1879, 230-231).

In 1763 the Hoge Regeríng in Batavia concluded that the potential gain from Sumba was too small to justify the intervention of the Kupang VOC and no further action was to be taken (Roo 1906, 213). This was not the opinion of the authorities in Kupang. In 1765 they ordered that 45 individuals be taken from Sumba and enslaved (Needham 1983, 13). They were later retained for the VOC’s benefit.

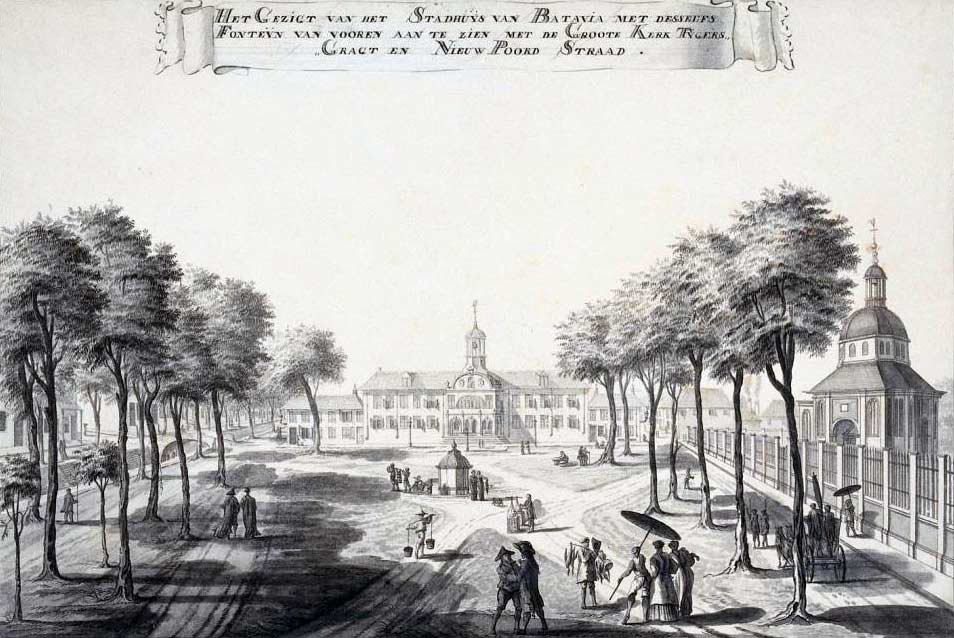

Batavia City Hall and Grote Kerk by Johannes Rach in about 1770

(National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta)

In 1768 the Raja of Mangili travelled to Kupang to ask the VOC to place an interpreter on Sumba and also to launch an expedition against Raja Sumba Galan of Umalulu who was apparently regarded as an enemy by the other domains (Roo 1906, 214-215). Kupang could not intervene but tried diplomacy, posting Corporal J. J. van Nijmegen to Mangili the following year in the hope of improving relations with local leaders and persuading them to expel the Makassarese slave traders (Roo 1906, 216). He was the first VOC officer to be stationed in Sumba and even persuaded a teacher from Ambon to open a local school. However after two years his appointment had achieved little effect. The Sumbanese rulers showed no loyalty to the VOC and continued to trade with Bimanese, Endenese, Butonese and Makassarese merchants, the latter sending 30 to 40 prauw to Sumba every year for sandalwood and slaves (Roo 1906, 226).

Following the appointment of B. W. Fockens as opperhoofd of Kupang in 1771 the company resisted a move against Umalulu but continued to maintain close relations with the Raja of Mangili, who reciprocated with annual gifts – in one year a pair of slave girls. Because of the unfavourable security situation Sumba was clearly a difficult place to deal with. In October 1774 Kupang sent a senior administrator called Tekenborgh on a 10-week mission to Savu and Sumba. His findings were summarised in his 1775 report, which is paraphrased below (Roo 1906, 219-235):

Sumba was a beautiful island with many plains lying between high mountains, criss-crossed by numerous large and small rivers. Despite being very fertile much of the land was left uncultivated as a result of the laziness of its inhabitants and continual warfare. There was a great deal of robbery and theft of foodstuffs and cattle and this was the cause of many of their conflicts. The Rajas did not have the slightest authority over their people and as such were incapable of fulfilling the promises that they had made to the Company. Every year Makassarese smugglers appeared on the coast of Mangili in 30 to 40 prauws to collect large numbers of slaves and sandalwood before sailing on to Selura off the south coast of Sumba and to Pasir Island south of Roti to gather large quantities of trepan. They paid for the slaves with muskets and gunpowder. Meanwhile the Endenese were trading with other domains on Sumba and the Bimanese were in close contact with Mamboro.

A model of an early Makassarese pirate prauw owned by the last Sultan of Gowa

(Tropenmuseum Collection, Creative Commons Licence)

Sandalwood was still available on Sumba but was scarcer than on Timor. In the past most of it had been exploited by private adventurers like the Topasses with no involvement of the VOC. For example, 100 trees had been felled at Melolo. However at Waijelo here were still large stands of sandalwood trees stretching to the horizon. Yet the natives were reluctant to fell the sandalwood trees, believing that they contained the souls of the deceased (Roo 1906, 233, 234 and 238). For the future, the foremost article of trade would be slaves supplemented with tortoiseshell, birds and trepang.

In order to gain a tighter hold on Sumba’s export trade, Tekenborogh concluded that the VOC would need to launch a punishing military campaign against Sumba using 4,000 troops, including auxiliaries and ships drawn from Savu and Rote, and with supplies and ammunition provided by Kupang. It would first sail to Ende and then attack Kapunduk and Kanatang before moving on to Mamboro and then finally subduing the stronger domains of Batu Kapedu and Lewa.

Possibly unbeknown to Kupang, the VOC was in severe financial straits after decades of mismanagement and corruption. After considering Kupang’s proposals the Hoge Regeríng, the supreme administration of the VOC in Batavia, responded on 30 December 1775, shelving the idea of an expedition to subdue Sumba ‘given the present state of affairs’.

Kupang in the 1790s (Roy Schreiber 2007)

Following the outbreak of war between Holland and Britain in 1780 the VOC was plunged into severe financial problems and lost its lines of credit (Gaastra 2007, 26). Despite making substantial annual losses it continued to pay its shareholders a 12½% dividend (Wielenga 2015). By 1789 its deficit reached 74 million Guilders and the Staten Generaal tried to gain political control. When French revolutionary forces began their attack on the Dutch Republic in 1792 it was the final nail in the coffin. Amsterdam surrendered in January 1795 and the House of Orange fled to Britain. King William V instructed the governors of his overseas territories to place their colonies under British rule. In 1796 the British, under Admiral Rainier, took control of Ambon and Banda and although Kupang capitulated briefly the following year but after some British soldiers were killed, the British Navy ended up bombarding the town.

Back in Holland the new Batavian Republic allowed the charter of the VOC to be extended to the end of 1798 and later to the end of 1800, after which it was then allowed to lapse (Gaastra 2007, 26). The VOC was declared bankrupt and its debts were taken over by the state.

Return to Top

Sumba from 1800 to 1866 – Dutch Negotiations Fail

Following the French annexation of Holland no information is available about Sumba for a quarter of a century. Although the British briefly restored the islands of the East Indies back to the Dutch after the Peace of Amiens in 1802, hostilities soon resumed. Britain declared war on France in 1803 and blockaded the French coasts in 1806, just as Napoleon founded the Kingdom of Holland under his brother Louis Bonaparte. After a disagreement Napoleon abolished the Kingdom in 1810 and annexed the Netherlands as part of France. The British quickly returned to the Netherlands East Indies, eventually storming Fort Concordia on 8 April 1811. They occupied it for less than a day, retreating after coming under fire from native marksmen (Farram 2007, 462-464). The British returned to Kupang in January 1812 and took possession of the town until 1816. Between 1812 and 1814 they appointed three Residents in succession – C. W. Knibbe, a Dutchman, and the two Englishmen Watson and Burn. Knibbe intended to alert the neighbouring islands about the British occupation and a ship was sent to Solor although not to Rote or Savu. It seems that unruly Sumba was not even a consideration.

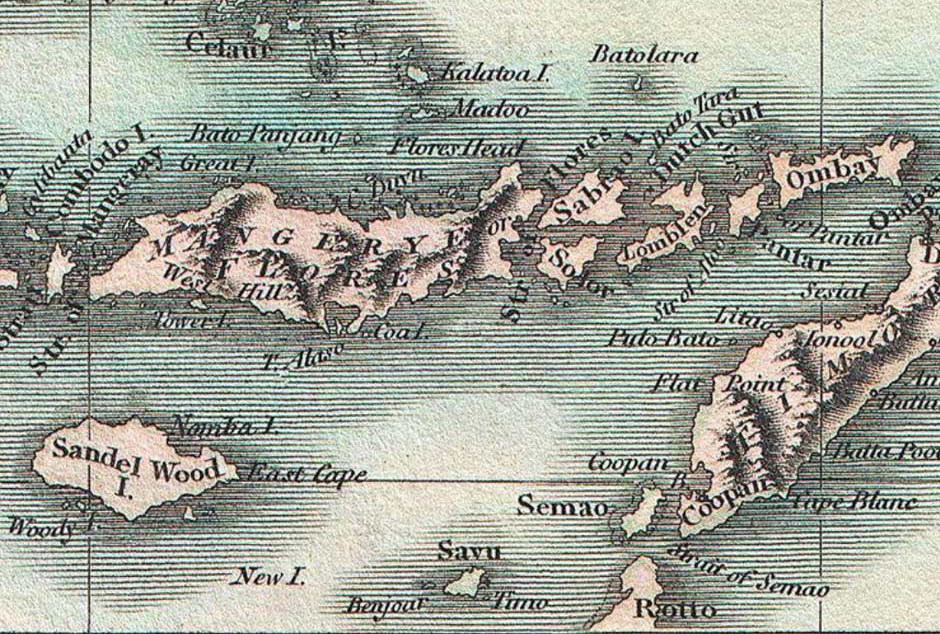

By 1800 cartographers had obtained a more accurate depiction of Sumba and its location

(A New Map of the East India Isles, John Cary, London, 1801)

With no other credible candidate available, the British administration in Makassar requested the previous Dutch Resident, Jacobus Arnoldus Hazaart, to take back control in 1814. In Europe, Napoleon was finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 but it was not until late 1816 that the British officer Lieutenant Philipps finally arrived in Kupang to meet Hazaart and formally transfer authority back from Britain to the Netherlands (Farram 2007, 471).

An indication of the violent situation pertaining on Sumba was illustrated by the fate of the Dutch ship Pamanukan, which was shipwrecked at Lamboya on the southwest coast of Sumba in 1820 while sailing from Java to Makassar. Instead of being rescued the crew were stripped, enslaved and taken off into the hills. After months in captivity the captain, J. A. Batiss, managed to escape and get to Makassar on an Endenese ship (Roo 1906, 240). Batiss dictated a detailed report about life in West Sumba to J. D. Kruseman, a financial commissioner in Kupang, including descriptions of houses, costumes, rituals and beliefs (Kruseman 1835, 63-74). The land was very fertile but agriculture was undeveloped. The Sumbanese grew rice, especially in Lamboya and as far as Mamboro, maize and potatoes and raised buffalo, goats, pigs and dogs. The islanders were good riders and kept beautiful horses that were strong and fast. Cotton grew everywhere and the best sandalwood forests were on the north coast. The island had no kings or chiefs but did have hereditary nobility, the maramba, who were respected for their oratory and bravery in warfare, ruling through consensus with decisions agreed at tribal councils. Although the nobles kept slaves, they lived closely together in the same house and ‘ate from the same dish as their masters’. Although there were numerous skirmishes that were not serious there was long-standing hostility between the people of Lamboya and Wanokakka, although nobody could remember why (Kruseman 1835, 63-74).

According to an 1831 report by the government commissioner E. Francis, some people from Savu had established their own kampong on Sumba after intermarrying with local families (Roo 1906, 241). Furthermore the Endenese had achieved a monopoly in the trade with Sumba, arriving in flotillas of 50 to 100 prauws (Roo 1906, 243). They would murder anyone else who came near to the island. At around the same time some minor chiefs from Sumba had visited Kupang where Resident Hazaart’s brother managed to acquire 200 pikols, about 12½ tonnes, of Sumbanese sandalwood.

Hazaart retired in 1833, but two years later his successor in Kupang was concerned about the corrupting influence of the Endenese on the Sumba slave trade. Yet Dutch intervention was out of the question at that time – the island was too far away, its closed society posed a major obstacle, and in any event no suitable vessel was available to go there. In 1836 the Dutch Resident of Timor reported that merchants from Ende and Larantuka had supplied the post of Fialarang in Belu on Timor Island with 1,000 slaves shipped in 28 prauw. They were stealing slaves from Sumba, as well as East Flores (then called Solor) and Alor, and shipping them in boatloads to Bali and Lombok, even supplying French ships from Bourbon (Reunion) and Mauritius (Roo 1906, 243-244).

The Dutch finally decided to admonish Larantuka and Ende with a naval attack, despatching a corvette, a brig and vessels manned by their allies from Savu and Solor. After attacking the kampong of the Raja of Larantuka they reached Ende in May 1938, first offering the Endenese a peace deal if they agreed to stop their pirates raiding Sumba for slaves. The Endenese declined and the Dutch supposedly destroyed 400 houses and 50 sturdy prauw (Roo 1906, 244). The following year Ende made an agreement with Kupang not to take any more slaves from Sumba. Yet unbeknown to the Dutch, they continued to do so, some Endenese even establishing bases on the island. In Batavia the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies asked the commander of the navy to consider stationing a warship in Sumbanese waters. He also set up an investigation that would lead to proposals for occupying and colonising the island.

Some years earlier, the Dutch Resident of Sambas in west Borneo, Diderik Johan van den Dungen Gronovius, had formed an acquaintance with a young enterprising Muslim, Syarif Abdur Rahman bin Abubakar al-Qadri, a relative of the Sultan of neighbouring Pontiak. When Gronovius took up the post of Resident of Timor in 1836 Syarif came with him and, since he was fluent in Dutch and a large number of local languages such as Makassarese and Endenese, was given a job in the port of Kupang. In 1839 Gronovius financed Syarif to move to Ende as his personal commercial agent (Roo 1906, 246). It did not take long for Syarif to visit Sumba and see there was money to be made from exporting the island’s tough Sandalwood ponies. After successfully shipping the first batch of 98 horses in 1841 (Fox 1977, 163), Syarif relocated his operations to Sumba in 1843, eventually settling in the natural harbour of Nangamessi Bay – a location that would later become Waingapu. By 1846 over 4,000 horses were exported. This venture would become so important that it would transform the political economy of the island.

Gronovius found that sandalwood on Sumba was not as scarce or as low quality as some had reported (1855, 303). The supply was restricted because the native population were superstitious about harming the trees. He estimated that the Endenese had exported 1,228 pikols (about 760 tonnes) between 1838 and 1848, about 75% from Palmedo and the rest from Mangili, Melolo and Andatta. If the market were opened up completely he believed the island was capable of supplying 6,000 pikols per annum.

Gronovius retired from his position as Resident in 1841, but in 1846 returned from Batavia to Sumba to review the development of his horse export business. He stayed for seven months during which he composed a detailed review of life on the island (1855). He found that slave merchants were now arriving from Bali, Lombok, the Gulf of Boni, Makassar and Bima, shipping their human merchandise back to Ende, Sumbawa, Bali, Lombok, Boni and the east coast of Borneo. In addition ‘pirates’ from the Komodo Strait were also capturing many slaves along the coasts of Sumba (Gronovius 1855, 297). The north coast of Sumba had been effectively depopulated.

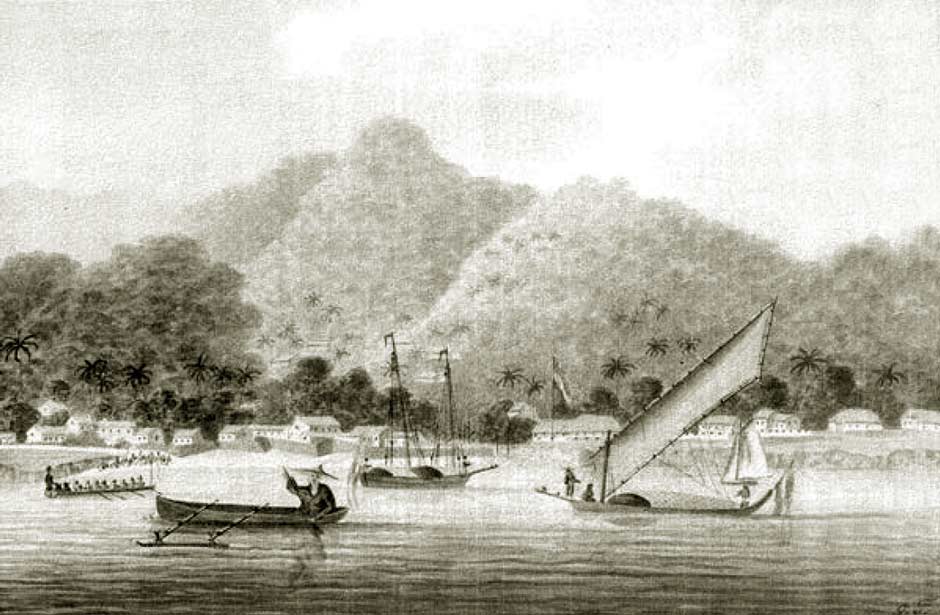

Kupang harbour in 1845, drawn by Charles William Meredith van de Velde

(Collection of the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

In 1842 the new Resident of Timor, Cornelius Sluyter, was ordered to submit a report on the situation on Sumba to the Governor-General. Later that year he received worrying news that a British warship had visited Sumba on its way from Kupang to Surabaya. Sumba was apparently often visited by British vessels, which had begun trading with the island. Sluyter decided to instigate a review of the 1756 Paravicini contract and soon discovered that none of the signatories from Sumba had established the slightest relationship with Kupang or fulfilled any of their commitments (Roo 1906, 248). However the regents of Savu, who were fiercely loyal to Kupang, advised against trying to take possession of the island as they had now established a foothold on Sumba and did not want the Dutch to rock the boat.

Sluyter finally sailed to Sumba on the schooner Egmond and during April and May 1845 signed contracts with the following chiefs:

- Raja Umbu Tugu of Kambera, Lambanapu, Endatar, Batakapido etc.,

- Raja Umbu Gala of Taimanu (Kanatang) and Sanpariengo,

- Raja Umbu Kambang of Kapunduk, Kamattu, Kadessan etc.,

- Raja Umbu Uiwindie of Palamedo (east of Mamboro), Lena, Ngadu, Mengommong, Prikambira, Uiwindolie, Bartulie etc.,

- Raja Umbu Dena Mondjorau of Kanatta, Tengedo, Kalamba, Sambayba etc.,

- Raja Umbu Nombong of Mamboro, Tana Kadungun, Paliendie etc.,

- Raja Umbu Dena Lakunara of Mangili, Sobie, Maro, Sewonie, Pidowatoe etc.,

- Fetor Umbu Mangu Kabul of the Talolua region,

- Raja Umbu Lando of Kadumbu on the northeast coast Sumba.

Walking canes or rottingknoppen with silver tops embossed with the Dutch coat-of-arms were awarded to the Rajas of Kambera, Taimamu, Kapunduk, Kanatang, Palamedo, Mamboro and Mangili, as well as to the Fettor of Mangili and the Raja of Kadumbu (Roo 1906, 250). The contracts stipulated that no Europeans were to settle on Sumba, other than the Dutch.

Surprisingly there seems to have been little contact during the following decade, although the brig Pylades did make a stop in Sumba in 1850 and the schooner Banda visited the south coast in 1852.

In 1856 the Resident of Timor, Siegfried Fraenkel, reported that there was no communication between Kupang and the chiefs on Sumba and so he had no idea whether the 1845 contracts had been maintained. Since the island was unguarded he feared they would soon forget their agreed obligations. Even if the contracts were maintained Sumba was so small and desolate, and its people in a ‘low stage of civilisation’, that had almost nothing to trade with Europe (Roo 1906, 252). His fear was that over the next few years an attempt would be made to establish a foreign settlement and he suggested that a Dutch warship should occasionally visit the island so that its chiefs could demonstrate how they had maintained their commitments.

The Resident’s fears were well placed. Since 1824 the British had been establishing trading posts on the north coast of Australia, opening Port Essington in 1838. They were keen to develop British trade across the Torres Strait and had been mounting exploratory trading voyages to Timor, the South Western Islands, Savu and Sumba. The English trade representative George Windsor Earl had clearly been well briefed about Sumba Island (1853, 184-185):

Sumba is a mountainous island, three hundred miles in circumference, lying to he south of Flores, from the coast of which it is distinctly visible in clear weather. The inhabitants of Savu possess a settlement near the south-west extreme of the island, and the Bughis traders of Ende have two or three stations on the north coast which are occasionally visited by small European vessels for the purpose of obtaining horses; but the natives of Sumba all dwell in the uplands, where they cultivate maize, yams, and other produce similar to that grown on Timor, and are said to use the plough .....The wild tribes, which dwell in the upper parts of the mountain ranges, are said to be very black and very savage; .....

Constant slave raids along the coasts had forced the island’s population to move their villages to high ground inland and to fortify them with walls and fences of thorns and cacti.

Batavia sent instructions to the Resident of Timor in 1858 to refresh the contracts made with the Rajas of Sumba. In response he suggested it might be pointless to establish new contracts because the Rajas could neither read nor write. The only way to gain influence on Sumba would be to install a posthouder (a civil administrator representing the colonial power or in charge of a trading post), defended by an armed and fortified garrison of around 10 to 12 soldiers (Roo 1906, 253). However there was little stability in the Dutch administration at Kupang – Residents came and went every two or three years.

On 1 January 1860 the Netherlands East Indies officially abolished slavery. This had no impact on affairs on Sumba Island (Needham 1983, 27).

Having been assigned the steam gunboat Z. M. Het Loo the next Resident of Timor, Willem Brocx, decided to assess the situation first hand and in June 1860 set sail for Sumba. After anchoring in Nangamessi Bay he was greeted and briefed by the Raja and the posthouder of Savu, along with Syarif Abdur Rahman. He was told there were five so-called Rajas of Ende who were based on Sumba and were actively engaged in slaving, mainly shipping their captives to Bali and Lombok. Brocx was given an example: the Raja of Kapunduk had previously been at war with the ‘mountain people’ living away from the coast. Having failed to get support from the other Rajas, he turned to Etto, one of the Rajas of Ende, who sailed 500 to 600 men across from Ende and captured a hundred slaves along with cattle and property (Roo 1906, 258). The Resident immediately sailed to Kapunduk intending to speak with Etto and the local Raja but they both refused to board his ship. In retaliation the Het Loo opened fire on 10 large prauw anchored in the mouth of the river while waiting to receive their cargoes of slaves.

Back at Nangamessi, Brocx went ashore to meet the Rajas of Kambera, Taimanu, Kadumbu and Mangili and their armed escorts, who had come at the request of the Raja and posthouder of Savu. There they renewed their contracts with the Dutch East Indies government after which the Het Loo fired a 21-gun salute. The other Rajas had refused to attend, believing the Dutch would punish their transgressions by taking their sandalwood.

During his visit Brocx gained concerns about Syarif Abdur Rahman who, in addition to taking a commission on the export of every horse. seemed to exert great power behaving as though he were the Raja of Sumba. He also had close ties to Ende and was rather worryingly married to the sister of the slave master Raja Etto. This confirmed Brocx’s view that he needed to place a posthouder at Nangamessi, primarily to deter the Endenese slave traders but also to influence the Rajas and keep an eye on Syarif Abdur Rahman.

Since Batavia was not yet in agreement, Brocx immediately took up the suggestion of the Raja of Savu to bring some of his Savu warriors to Sumba. In late July 1860 some 400 Savunese arrived at Kadumbu only to find that several Rajas of Ende, including Etto, had recently threatened to destroy that village unless they received compensation for the 10 prauw destroyed by the Dutch (Roo 1906, 264). The Savunese went to the small Endenese kampong and a skirmish ensued in which Etto and three of his followers were killed. The remaining Endenese fled to Patawang and sent for reinforcements from Ende. A running battle ensued throughout September, with the Savunese supported by the Raja of Umalulu attacking the Endenese who eventually fled to Waingapu. Most of the Savunese returned to Savu. In return for his support, the Raja of Melolo requested that Kupang award him a ceremonial gold-topped cane or rottingknoppen. Having been led to believe that Umalulu was especially important the Dutch initially agreed, only to find that the Rajas of Kambera and Taimanu wanted gold-topped canes as well (Roo 1906, 268-269)!

Isaac Esser superseded Brocx as Resident of Timor in late 1861 and took no time before visiting Sumba. Esser realised that his predecessors had completely misunderstood the powers of the local Rajas. The Rajas were not sovereign kings but shared power with the senior ratu or priests and had to comply with adat. Not only did they have little understanding about the contracts they had signed, they had no way of making their subjects comply even if they did. Kupang could not establish a relationship with 50 separate domains via gunboat. They needed to install a posthouder on the island to liaise with the tribal chiefs. It would be a mistake to grant a gold-topped cane to the Raja of Umalulu until the relationship with the other Rajas had been clarified. In the meantime the negotiation of further contracts was placed on hold (Roo 1906, 273).

Esser found that the export of slaves from Sumba had virtually ended. Instead the Endenese were attacking and pillaging villages in the interior of the island and selling people to the coastal Rajas (Roo 1906, 244-245).

On the other hand the export of horses from Sumba was now becoming significant. During the months of April and May 1863 seven ships transporting horses to Java as well as an American whaler were shipwrecked around the coasts of Sumba and were subsequently plundered, in some cases with the involvement of the local Rajas. Kupang held the Rajas of Kambera, Taimanu, Kadumbu, Sudu, Umalulu, Rindi, Mangili, Lewa and Mamboro accountable since their contracts committed them to provide assistance to shipwrecked sailors and to refrain from beach robbery. Military retribution was considered pointless because the coastal people would simply retreat into the hills. Instead it was decided to demand compensation to be paid in the form of numbers of horses.

The looting of ships provoked Batavia, which proposed that the responsibility for Sumba be transferred from the Resident of Timor to the Governor of Sulawesi. In response the latter sent his capable assistant, J. A. Bakker, to Kupang in 1864 to assess the situation, before travelling on to Sumba where he spent a fortnight visiting all of the relevant Rajas. On the basis of Bakker’s report, the Governor recommended that because of its close links to Ende Sumba should remain the responsibility of Kupang. It was obvious that the Rajas had no understanding of the contracts they had entered into. Yet the fact that Syarif Abdur Rahman had gained enormous influence on Sumba while remaining safe and secure for 24 years without Dutch military support showed the way forward. The Governor advised that the Netherlands Indies should place an official on the island protected by a dozen armed police and supported by 25-30 Javanese to build dwellings and teach agriculture. Batavia accepted his advice but decided to delay implementing his recommendations until the fines had been paid.

The following Resident of Timor, Jan George Coorengel, sailed to Sumba on the steamship Telegraaf in 1865 to take delivery of the horses. While the Raja of Taimanu had delivered 24, the other Rajas claimed various excuses or in one case denied liability. To maintain Dutch authority it was essential the fines be paid, but Coorengel knew that a military intervention would be expensive and out of the question. Demonstrating remarkable patience, he instructed the captain of the Telegraaf to return to Sumba and gently persuade the Rajas to fulfil their obligations. When Coorengel returned in early 1866 the Rajas came up with more excuses of why the horses had yet not been delivered. The Telegraaf steamed back to Sumba yet again, where it seems that with the one exception of the Raja of Sudu, the Rajas finally delivered the horses.

During his discussions with the Rajas, the captain of the Telegraaf discovered that Syarif Abdur Rahman had a more sinister side. He had been double-dealing – secretly establishing a lucrative sideline in slave trading while also engaging in private wars using reinforcements from Ende (Roo 1906, 283-284). The Rajas could not understand why they were being punished while the official Dutch agent was engaged in exactly the same activities.

The need to put a Dutch posthouder on the island was urgent.

Return to Top

Bibliography

For the bibliography please click here.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 18th March 2018.