Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kisar Textiles Part 3:

Introduction

The Current Status of Weaving on Kisar

Cotton and Drop Spinning

Binding and Natural Dyeing on Kisar

Dye Painting

The Kisar Loom

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 1

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 2

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 4

Introduction

This webpage summarises the findings of our research trip to Kisar Island, undertaken at the end of the dry season in November 2017. Our objective was to visit weavers in all three local communities, the Meher-speaking majority (population over 12,000), the small enclave of Indo-Dutch mestizos (population around 250), and the Oirata-speaking people who live in the two villages of Oirata Barat and Oirata Timur (population less than 2,000). We wanted to document their spinning, binding, dyeing and weaving techniques and to study and understand the textiles that they are still producing today compared to those they produced in the past. We also wanted to clarify the terminology that each linguistic group applied to its textiles, its patterns and motifs, its looms and other related equipment.

Interviewing Ibu Rahel Letelay, aged 81, a Meher dyer, binder, and weaver from Dusun Yawuru

David with 82-year-old Ibu Lorenci Serain, a master weaver from a noble lineage of the leading Hano’o clan of Oirata Timur

It was apparent during our visit that most of the scant material that has been written about the textiles of Kisar over the years is confused or incorrect. Many of the Europeans who voyaged to Kisar during the eighteenth and nineteenth century and commented on its culture were sea captains, missionaries or government administrators who had limited experience concerning the production of hand-woven textiles and little understanding about, or indeed interest in, local ethnic costume. Many of their reports excessively focussed on the small community of Dutch descendants at the expense of the Meher- and Oirata-speaking majority. Many of the reported observations differed from visitor to visitor and were sometimes conflicting.

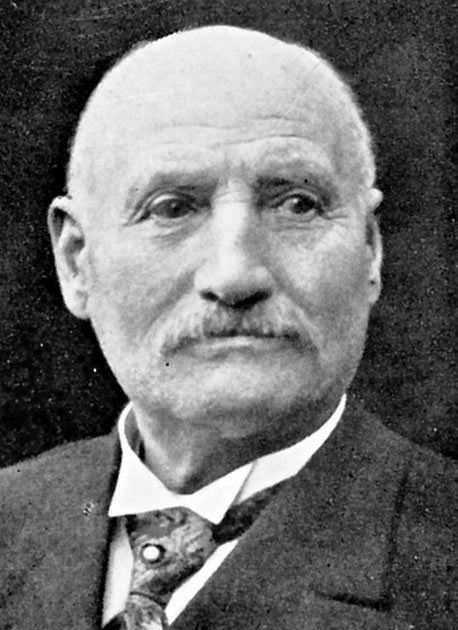

Johan Adrian Jacobsen, left, arrived on Kisar on 18 February 1888 and spent five days on the island. Wilhelm Müller-Wismar, right, visited Kisar in 1914 during the Berlin-Indonesian expedition to the South Moluccas.

Only the Norwegian Johan Jacobsen and the German Wilhelm Müller-Wismar were ethnographers and collectors. Despite this, both left us with rather inadequate reports of their visits. This may be because their primary aim was to acquire and collect the textiles and artefacts of Kisar, not to study them. We do not know how Jasper and Pirngadie obtained their information about weaving on Kisar that they published in 1912 but it was clearly one-sided, ignoring the important Oirata population. No museums or private collectors have seriously researched the textiles of Kisar on the ground since the brief visit by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar in 1914. As such many inaccuracies and misconceptions have been allowed to develop and circulate among the textile fraternity.

Many of the other Kisar textiles in museum and private collections have not been acquired directly but have come from auctions and dealers and therefore lack any provenance. With no record of who made them, where, when and how they were made, or how they were subsequently used, they have little value to the textile historian. To make matters worse, their owners have frequently mislabelled them and sometimes attributed them to neighbouring islands such as Leti or Luang.

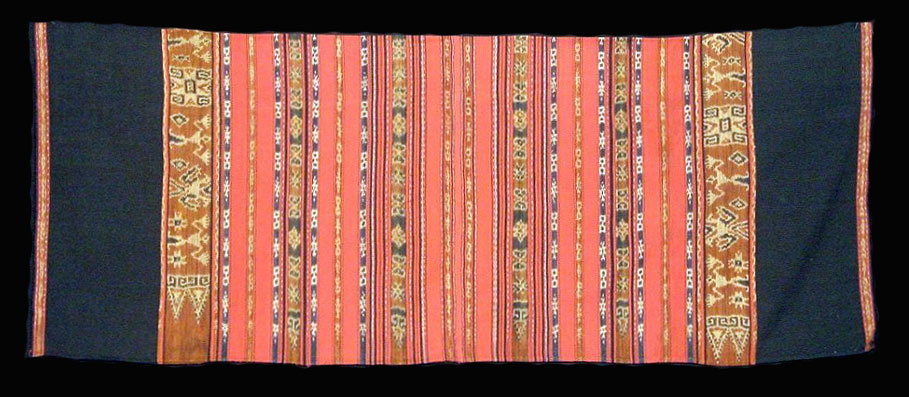

In particular there has been little understanding of the differences between the textiles of the Meher and the Oirata communities. Although they share many features, such as their layout, design and motifs, there are crucial differences between them – differences that are immediately obvious to anyone familiar with the island’s textiles.

Return to Top

The Current Status of Weaving on Kisar

The art of traditional textile production is very much on the wane across Kisar Island. Within two decades there will probably be very little left to see.

Weaving remains strongest within the Oirata community, which has traditionally produced the finest warp ikat textiles. Six of the more proficient Oirata binders and weavers belong to a small group called Kelompok Fajar (Group Dawn), four coming from Oirata Timur and two from Oirata Barat. These women were all taught to drop-spin, bind, prepare indigo, morinda and other natural dyes, and weave. However the number of women who can still bind and weave is falling alarmingly.

Today there are just five women left who can bind ikat: Lorenci Serain (aged 82), Henderina Ratu Mali (75), Sus Resimere Serain (71) and Yuliana Serain (66). These women bind the ikat patterns but do not weave. In addition there are just five women who can weave: Susana Resimere (77), Susana Latupae (71), Melsina Silkata (63), Velpina Ratu Romon (50) and Antoneta Resimere (35). Very few are still using hand-spun cotton and only some know how to dye indigo. Most are increasingly using synthetic dyes.

In the past every girl had to become a competent weaver before her parents allowed her to marry. Today most young women do not want to spin, dye or weave. One member of Kelompok Fajar illustrated this with an example from her own family – she has two daughters aged 23 and 24 and neither can weave. It is clear the days of weaving among the Oirata community are numbered. Local leaders are also concerned that the majority of heirloom Oirata textiles have been sold and no longer remain on the island, posing a threat to the traditional social culture. The situation has become so bad in the two Oirata villages that the kepala desa is proposing to ban the sale of any more textiles.

The authors with four members of Kelompok Fajar, Oirata Barat

Our contacts in the small Meher-speaking mestizo community confirmed that weaving died out many decades ago. In 1925 Ernst Rodenwaldt found that weaving had already been abandoned by most of the mestizo families (1927, 434). At that time, commercial cotton was widely available and aniline dyes were displacing indigo. More importantly, young girls were going to school and not being taught how to dye and weave. Although one mestizo woman, seventy-four-year-old Adriana Bakker, was still producing fine work, Rodenwaldt predicted that it would not be long before mestizo textiles would only be found in museums. His predictions were correct. Francina Joostensz, who is in her sixties, confirmed that when she was a young woman in 1960 there was no tradition of weaving among the descendants of the Europeans. Eighty-two-year-old Erens Belder, a mestizo who was born in Surabaya, came to Kisar in 1958 to look after his mestizo grandfather. He found there was no memory of weaving within any of the mestizo families at that time. We suspect that weaving among the mestizos had already become obsolete by the start of the Second World War.

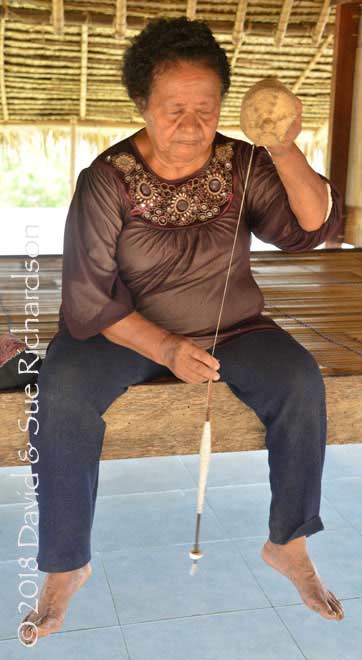

One of the five remaining weavers in Dusun Yawuru

The situation among the Meher-speaking majority is even worse than among the Oirata. It is hard to estimate the number of remaining weavers but they are few. There are none in the royal family and apparently none in Wonreli or neighbouring Lekloor. In the former weaving stronghold of Yawuru, only five active weavers remain. They all use commercial cotton because local cotton is no longer easy to get and few women can spin. Eighty-one-year old Mama Rahel Letelay told us that the young are no longer interested because producing textiles is difficult. She is still making indigo and morinda and producing good quality ikat but her adult granddaughter does not know how to weave. We could only find one weaver in Lebalau and there were none in Purpura. We could not locate any weavers in Abusur either, although a few survive in neigbouring Mesiapi. Even more shocking is that some of the remaining weavers we encountered are now producing very poor quality work. It appears that spinning and natural dyeing has almost disappeared from the Meher community. All of the remaining active Meher weavers we encountered were elderly women. Clearly it will not be long before weaving among the Meher becomes obsolete too.

Things have become so dire that in recent years the Meher have begun importing extemely crude chemically-dyed 'Kisar-style' homnons produced in Kalabahi on Alor Island. The quality of the ikat binding is atrocious. It's heartbreaking.

Above and below: two 'Kisar-style' sarongs photographed on Alor Island

A woman on Pantar Island wearing a 'Kisar-style' sarong made in Kalabahi

Cotton and Drop Spinning

Local cotton is no longer easy to get, so the overwhelming majority of cotton used on Kisar today is commercial. Whilst a few Meher weavers say they can still drop-spin, only the Oirata remain active proficient spinners, still processing a limited amount of raw cotton into yarn for weaving into cloth. Cotton has clearly not been cultivated on the island for a long time. An early-nineteenth-century visitor reported that cotton grew widely across the island (Van Hoëvell 1855, 227). Although cotton was still being cultivated in 1925 by slaves brought to Kisar from Timor, Rodenwaldt was of the opinion that it would soon be replaced by imported Chinese and European yarns (1927, 5). Today, sixty-five year old Hendarina Dauklori can only remember cotton being grown by the local Meher community when she was a child – in about 1960. Since then cotton has been in short supply and there have been times when villagers could only harvest enough to weave short sarongs.

The Oirata call the process of removing cottonseeds from raw cotton by hand, waare, and the process removing cottonseeds with a roller and block of wood, oré.

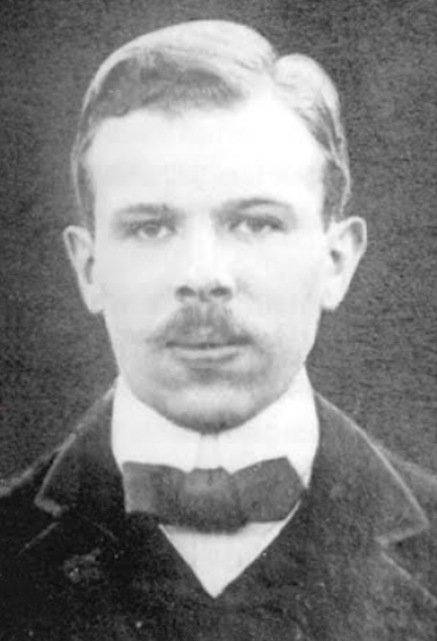

The Oirata drop spindle with a seashell whorl

An Oirata spindle (angka'i kette), rolag basket (wettur) and ash container

Richardson Collection

Both the Oirata and the Meher employ a similar technique for drop-spinning, using a hardwood spindle fitted with a seashell whorl at the bottom. The raw cotton is tightly packed into a small open-topped hexagonal basket, which has a short pronounced neck. The latter is gripped between the forefinger and middle finger of the left hand and held at chest height, head height or even above the head, while the cotton yarns are teased out with the right hand (and sometimes the left as well) before the spindle is spun clockwise with the right hand to produce a z-spun thread. Some spinners support the spindle while others do not. Some spinners use a second small basket containing a coconut shell with ash in it, in which they periodically dip their fingers to keep them dry.

An elderly woman drop-spinning in front of a basket of ash at Oirata Barat

Two women from Kelompok Fajar spinning raw cotton, one using an unsupported spindle and the other with a supported spindle

Women drop-spinning at Oirata Barat

Despite being identical in appearance, the Oirata and Meher use quite different terms for the spindle and basket.

Terminology

| Item | Oirata | Meher | Jasper & Pirngadie |

| Spindle | Angka’i kette | Pokor | Pokra |

| Rolag basket | Wettur | Ahuwiur | Ahwiore |

| Spindle and basket | Pokor ahuwiur | Pokraoewe | |

| Stick | Kette | ||

| Spindle whorl | Ti’ik waku |

Josselin de Jong called a weaver’s spindle an an’kai and a stick or part of a loom a kete (1937, 225 and 246). A Meher spinner told us that the spindle and basket are never described separately but always as one combined item, the pokor ahuwiur.

Return to Top

Binding and Natural Dyeing on Kisar

When Jacobsen visited Kisar in 1888 he found that both the Oirata and the Meher bound their yarns using braided pattern cards made from coloured koli (lontar) palm leaves (1896, 132). They were called sibi and kanàda respectively.

We encountered no such patterns. Today the ikat makers bind their patterns from memory using plastic string.

Ibu Lorenci Serain from Oirata Timur binding her motifs from memory.

Binding is called ilana more, more meaning to put or lay down

The Oirata ilana ete binding frame

In the Oirata language according to Josselin de Jong (1937, 231 and 238), ile means to tie, iliana means threads stretched and ready for dyeing, and ete means wooden.

Generally the task of binding is relatively simple because even the widest ikat bands are quite narrow. The widest ikat band being tied on the binding frame shown above contains just 25 bundles of yarn, while the narrower bands contain only 5. Because Oirata (and Meher) textiles are composed of so many different coloured stripes, the most onerous task is not the binding but the warping up of the loom.

Because there are so few women left in the two Oirata villages who can bind ikat, a few weavers take their yarns to be bound on Alor Island and then bring them back to Kisar!

Indigo grows wild and prolifically within the interior of Kisar Island and is still used as a dye by a minority of the weavers who remain active. Indigo is called tarum by the Oirata (taruma according to Josselin de Jong 1937, 276) and karung by the Meher.

Indigo growing wild at Lewkloor and Abusur

Oirata dyers soak the indigo leaves in cold water with lime for one week before immersing their yarns.

Balls of dark and light indigo-dyed commercial cotton – Oirata Barat

Both Meher and Oirata dyers sometimes boil the indigo solution instead, which produces a dark blue-grey instead of blue. In the early 1800s indigo was boiled in southern India where it was found to produce a more purplish hue (Weston 1829, 312). More recently boiled indigo has been used by the ethnic Yao of China and Southeast Asia and the Nagas of India (Pourret 2002, 187; Ganguli 1984, 242). Boiling will not affect the indigo, which is highly stable to temperature, but will extract tannins from the plant leaves and stems.

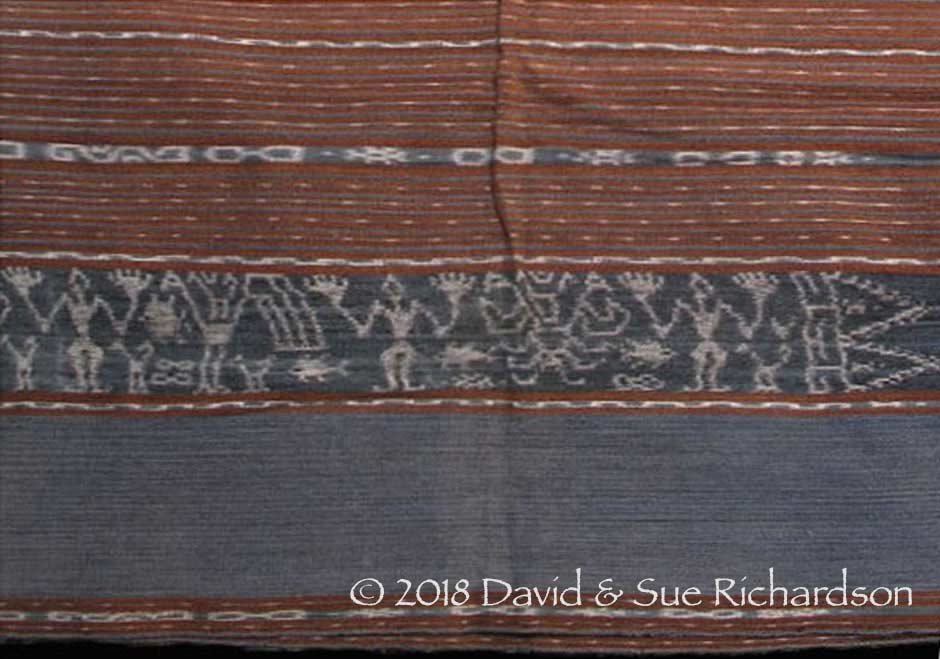

Plain and ikatted grey bands on a Kisar homnon

(Private Collection)

Two types of morinda thrive on Kisar – the medicinal Morinda citrifolia var. citrifolia and the dye source Morinda citrifolia var. bracteata. Morinda is called ne’nuka in Oirata and ne’nu in Meher.

Morinda citrifolia var. citrifolia growing by a main road in Wonreli

Because Kisar is a relatively low-lying island devoid of mountains, there is no local supply of candlenut - an important source of oil used widely across eastern Indonesia for dyeing morinda. Morinda dyers on Kisar therefore use an alternative source of oil – the seeds of kusambi, variously called the Makassar, Kusum or lac tree or the Ceylon Oak (Schleichera oleosa). The tree is also called kusambi on Timor. Elsewhere it is called kesambi and kosambi on Java, kasembi and kahembi on Sumba, and kahebe on Savu. This medium-sized tree grows in dry woodlands and deciduous forests across eastern Indonesia (Quattrocchi 2012, 3359).

The islanders also have no local source of loba. This is obtained from various species of Symplocos trees that grow at higher altitudes. Their leaves and bark provided a vital source of aluminium mordant, the second crucial ingredient required for binding the morindin dye to the cotton fibres to achieve a wash-fast brown. Surprisingly to us, the dyers we encountered produce their morinda dye without the use of any mordant at all, just adding the same lime powder that is used for chewing betel nut. Whilst this still achieves a good morinda brown, the resulting threads are not wash-fast. Weavers from both the Meher and the Oirata communities repeatedly emphasised to us that textiles from Kisar should never be washed – if they are, the brown colour will run.

Bundles of plastic-wrapped morinda dyed threads drying at Yawuru

Whether this has always been the case is hard to judge without chemically analysing the browns on old cloths with known provenance. Obviously loba is available on the higher nearby islands of Wetar, Timor and Alor and might have been traded to Kisar in the past.

The lack of loba may have been the motivation for local dyers to look for alternative sources of brown. In 1934 Josselin de Jong found that the Oirata produced a dye for colouring yarn by boiling a tree bark called kurin (1937, 248). Today some Oirata dyers prepare a purplish-brown dye using the bark of the kusambi tree (Schleichera oleosa), the same tree whose seeds are used for obtaining oil. The bark, which is astringent and tannin-rich, is boiled in water with lime powder to produce the dye. One Meher dyer in Yawuru was producing a brown by mixing kusambi with morinda root.

A mature kusambi tree at Oirata Barat and the trunk of another at Yawuru showing the red pigment

In yet another misguided government initiative, dyers in Oirata were recently taught some new dyeing methods by visitors from Saumlaki on Tanimbar Island. One was a new way of producing brown by boiling mahogany bark. When the mahogany is not strong enough the colour is boosted with the addition of some synthetic dye.

Yellow was traditionally obtained from kayu kuning. Very recently the dyers from Saumlaki showed Oirata dyers how to also obtain yellow from mango bark.

Oirata dyers produce green from the leaves of two different types of tree – kakara and katapang. The latter is the Indian Almond (Terminalia cattapa), a medium-sized tree with large leathery leaves. Its leaves have been reported as a dye source elsewhere (Parthiban, Kanna and Vennila 2016, 497).

Return to Top

Dye Painting

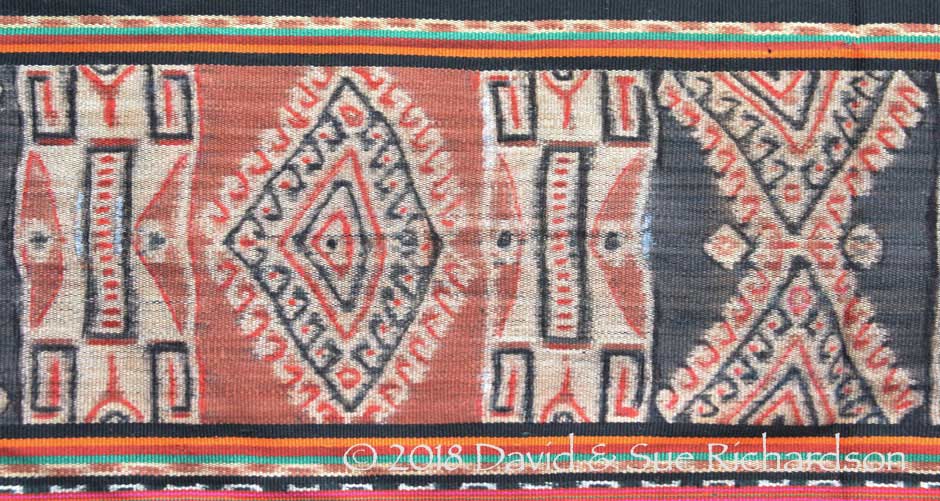

There has been a long-term tradition on Kisar of outlining the motifs on warp ikat textiles after they were woven, particularly those dyed with morinda or kusambi. Two examples of Kisar textiles with stencilled motifs were illustrated by Langewis and Wagner in 1964 (figs 207 and 208). This feature was also mentioned by Gittinger in relation to a homnon decorated with anthropomorphic motifs (1979, fig. 151) and Khan Majlis in relation to the cloths collected by Jacobsen (1991, 316). The technique has been used to paint bold black lines on an Oirata textile in our collection that we know to be almost exactly one hundred years old.

Unlike other islands in the Lesser Sundas, weavers on Kisar bind and dye the yarns for their decorative ikat bands and stripes only once. If they wish to add a second colour they achieve this through over-painting by hand.

A homnon collected before 1940 with motifs painted in black.

Tropenmuseum Collection, Amsterdam

A Meher homnon with motifs highlighted in black

Richardson Collection

This finishing technique may have emerged because of the inadequacy of local dyeing methodologies, with no aluminium mordant available to fix morinda and the rather subdued purplish tones arising from the use of kusambi. In some old Oirata sarongs it is possible to see where lighter patches of purple kusambi have been darkened by over-painting.

This technique of outlining motifs is called tupa kana by the Oirata and wek'wekur by the Meher. The Oirata word tupake means to dye yarn (De Jong 1937, 279). The painting is executed using a pointed stick.

A 30-year-old Oirata lau on which the motifs have been infilled with black

Private Collection Oirata Timur

Red highlights painted onto an old Oirata lau. Private Collection Oirata Timur

In recent decades this technique has been abused, especially by Meher weavers, and has become a short-cut low-quality method of decorating textiles compared to the more labour-intensive warp ikat technique.

A hoire man’s blanket from Yawuru with motifs that are entirely hand-painted

Private Collection Yawuru

A homnon in which all the red and black detailing has been crudely painted on by hand

Private Collection Purpura.

Return to Top

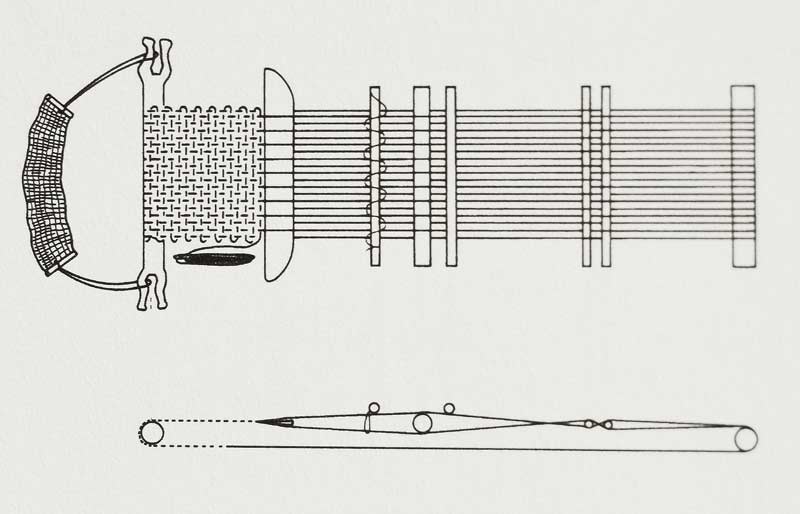

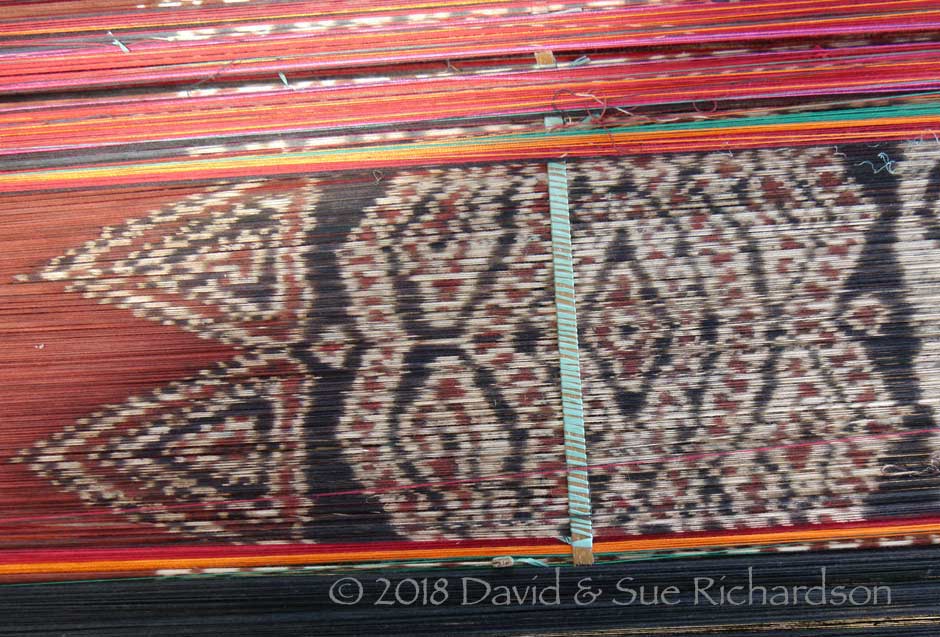

The Kisar Loom

The Oirata and Meher back-tension looms are almost identical and are always used with the back beam fastened to the side of the house or to a fence so that the warps are oriented upwards at around thirty degrees. In contrast to the Lamaholot loom for example, the continuous warps are long - permitting both panels of the two-panel sarong to be woven at the same time. The breast beams are made from a single length of wood with forked ends and therefore do not clamp the warps. Weavers wind their heddles using blue plied nylon fishing cord. Even their long wooden swords have exactly the same bowed shape.

These close similarities might suggest that the weaving techniques of the two communities on Kisar Island developed from a common origin.

Neither the Oirata nor the Meher have a local word to describe the complete loom.

The Oirata Loom

The Oirata loom is very similar to the looms found on Timor Island, such as those used by the Atoni or weavers in the Lautem district of Timor Leste (see for example, Schulte-Nordholt 2013, 43)

There are two types of Oirata loom, one for weaving cloths for skirts (and also in the past loincloths and shoulder cloths) and a smaller version for weaving belts and narrow selendangs. Both are highly portable, so a woman can interrupt her work whenever required to attend to her other responsibilities.

A member of Kelompok Fajar demonstrating how the Oirata loom is carried

Weaving cloth for a lau on the Oirata loom

Using a pick to focus the ikat prior to weaving

The yoke has a back support fashioned from a piece of tree bark

The narrow Oirata loom has exactly the same layout as its larger cousin. Today it is employed to weave modern synthetically-dyed ikat sashes, which the majority of women wear with the traditional lau. These selendang-like sashes are not traditional and are called sanikir - the same name as a man's blanket.

A member of Kelompok Fajar weaving on a narrow sash loom

There are a few similarities in the terms used to describe the Oirata loom and those used for the Meher loom, such as the breast and warp beams and the sword. Other terms are quite different:

Oirata Terminology

| English | Oirata |

| Breast beam | Katam or Katama |

| Warp beam | Oro |

| Yoke | Huipal or Hui pal |

| Sword | Walir |

| Stretcher | Sikara |

| Heddle yarns | Lun |

| Heddle stick | Lulun kette |

| Bamboo shed stick | Dudu (meaning bamboo) |

| Lease sticks | Hehese |

| Very long shuttle | Owana |

| Pick | O’he |

| Locking stitches | Riate |

Josselin de Jong mentioned two additional terms relating to the parts of an Oirata loom – an utnutan and a wetwetur - but unfortunately did not describe what they were (1937, 285 and 288).

The Meher Loom

The Meher loom along with its component parts was first described by Jasper and Pirngadie in 1912. As an accompanying illustration, they provided a schematic diagram of the 'south Maluku loom', which had the same fork-ended breast beam found in the Meher loom:

Schematic of the arrangement of the south Maluku loom

(Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, fig. 178)

Little seems to have changed over the past one hundred years. The shuttle is simply a long round stick with the weft wrapped around it in a helical fashion.

The warp beam is tied to a fence beside the house, inclining the warps at about thirty degrees

The weaver uses a stretcher or temple to maintain an even width of cloth

The warps in the main ikat band are locked in alignment by tying them to a short stick

This is called the pi’au

The red warp stripes are called awah ma’mere, the yellow stripes awah ma’mare and the green stripes awah mo’moke.

Rolling up the Meher loom at Yawuru. The foot brace is kept in place by wooden pegs

The terminology of the Meher loom is very similar to that given by Jasper and Pirngadie in 1912:

Meher Terminology

| English | Meher | Jasper & Pirngadie |

| Breast beam | Akam | Akam |

| Warp beam | Ore | Oro |

| Yoke | Alpuik | Kali oknelhe |

| Back support | Awu huikhuik | Alpoekei |

| Sword | Wilii | Wilië |

| Stretcher | Hini’ir | |

| Heddle yarns | Yo’on | Joön |

| Heddle stick | Yo’o nau | |

| Bamboo shed stick | Leleken | Leleken |

| Lease sticks | Pepehe | Pepehe |

| Locking stick & yarn | Pi’au | |

| Foot support | Awu nahari |

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 19 February 2018.