Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

The Ilé Apé District

Ilé Apé Ethnography

Local Cotton and its Processing

Binding

Natural Dyes

Indigo

Morinda

Moringa

Réo Bark

Tenor Bark

Mango Bark

Tamarind

Natural Black

Turmeric

Weaving

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

A Fragmented History of Ilé Apé and its Textiles

Women's Sarongs

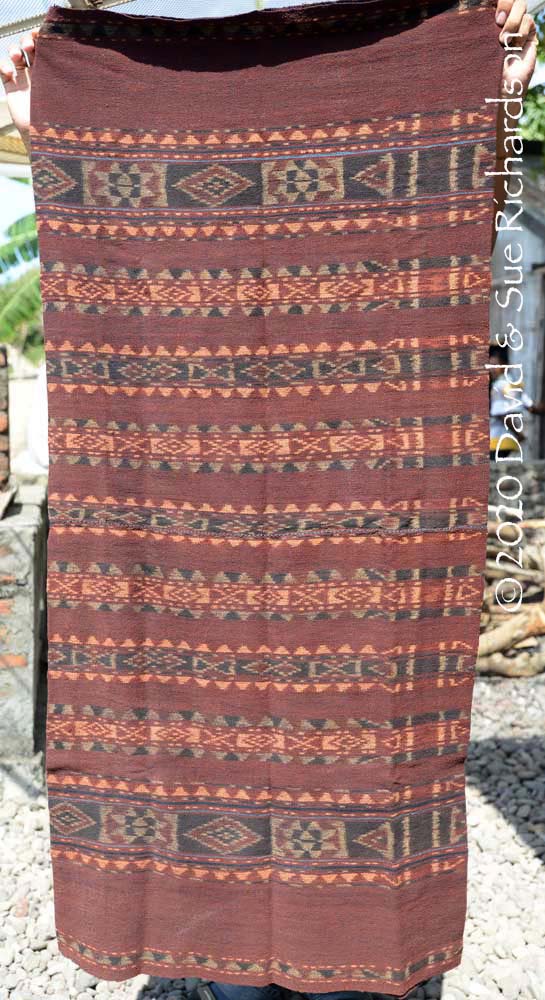

Wate Mohle or Wate Kerokong

Wate Buraken

Wate Topon or Wate Krokon

Wate Kebo Lolon

Wate Hebaken or Wate Hebak

Wate Ohin or Wate Bala Ohi

Wate Ohin Motifs

The Revot on Ilé Apé

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Ilé Apé Textiles 3 - Coming Soon

Watek Senewaken

Tenépa

Wate Nai Pa

The Influence of Indian Patolu

Kewodu

Nowing

Senai

Bibliography

Introduction

We first arrived in the Ilé Apé region of Lembata Island on a small boat in 1991, before returning in 2004 to research its textiles. Since 2013 we have visited the weavers of Ilé Apé once or twice every year, building friendships with some of the best ikat producers on Lembata Island.

Ilé Apé photographed from Nuha Nera in 1991

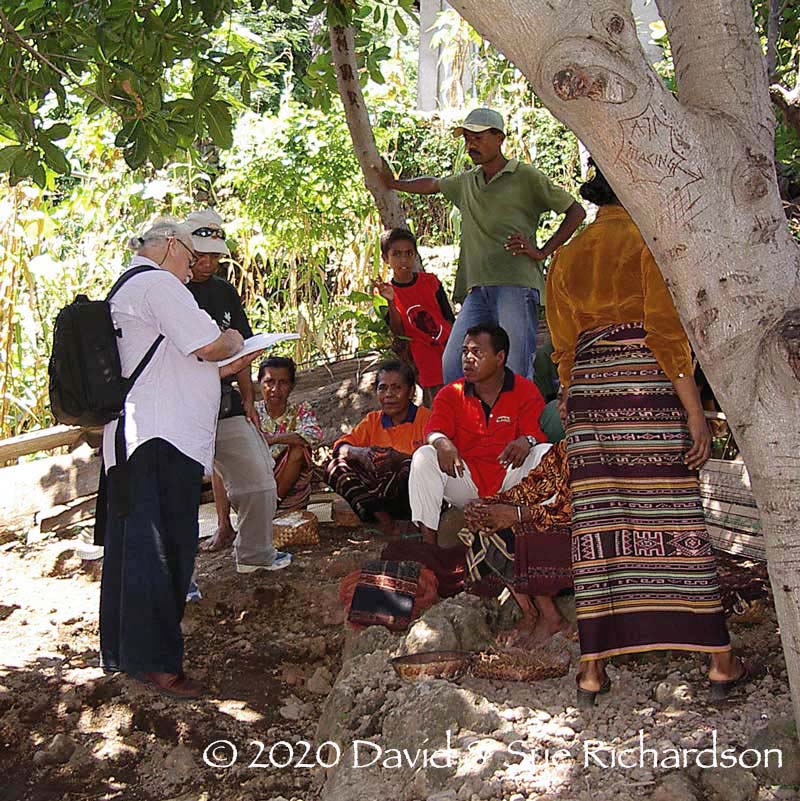

Interviewing weavers at Lamagute in 2004

The Ilé Apé region of Lembata Island has a rich weaving tradition that continues to this day, its women producing some of the finest warp ikat textiles in eastern Indonesia. In 1929 Ernst Vatter rated the ikat textiles of Ilé Apé alongside those of Lamalera, South Solor and Loba Tobi on Flores (1929, 214).

A few of the weavers from the north coast of Ilé Apé

Traditional Ilé Apé textiles are woven from locally-grown hand-spun cotton that has been initially dyed with many immersions in indigo and subsequently dyed with many further immersions in rusty brown morinda. Today they also produce many textiles using commercial machine-spun yarn.

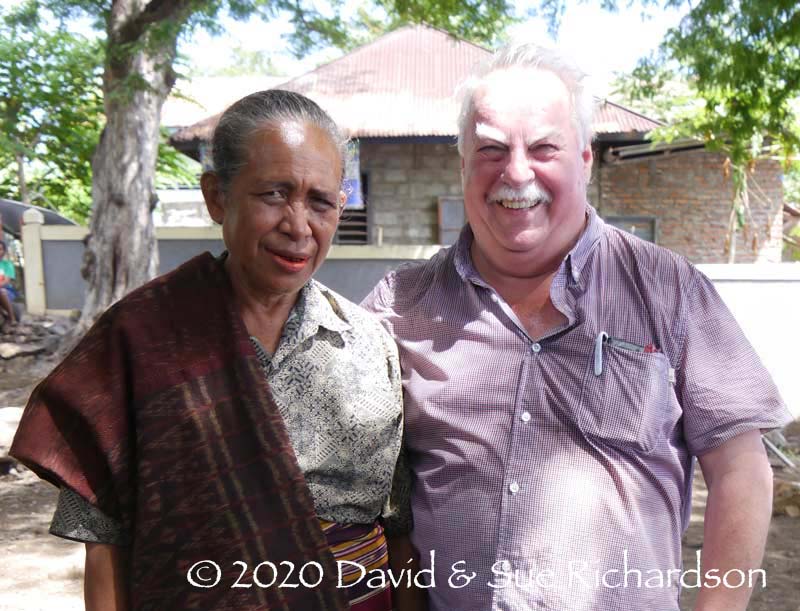

The authors with Julie Tenoa (the head of the Bungamuda weaving group)

and the master dyers Mulia and Maria

The authors at Napasabok with master weavers Salma Deram and Monika Kihan

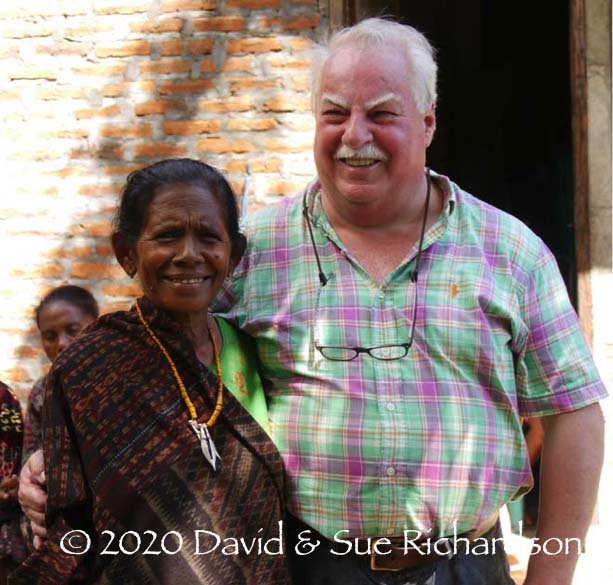

David with Margaretha Jawa Betekeneng from the highest status Betekeneng clan,

the best tenépa weaver in Lamagute

Villages on Ilé Apé depend on slash and burn agriculture, so their menfolk are mainly subsistence farmers who cultivate maize, dry hill rice, sweet potatoes, cassava and beans. Many of the local rituals are based on the annual agricultural cycle, such as the important bean harvest. There are very few fishermen.

The most important weaving villages on the north coast are Lamawara, which has 26 weavers, Napasabok with 90 to 100 weavers, Bungamuda with over 80 and Lamagute with 40 to 50. The two main weaving villages on the east coast are Lamawolo with 30 weavers and Jontona with around 150.

Return to Top

The Ilé Apé District

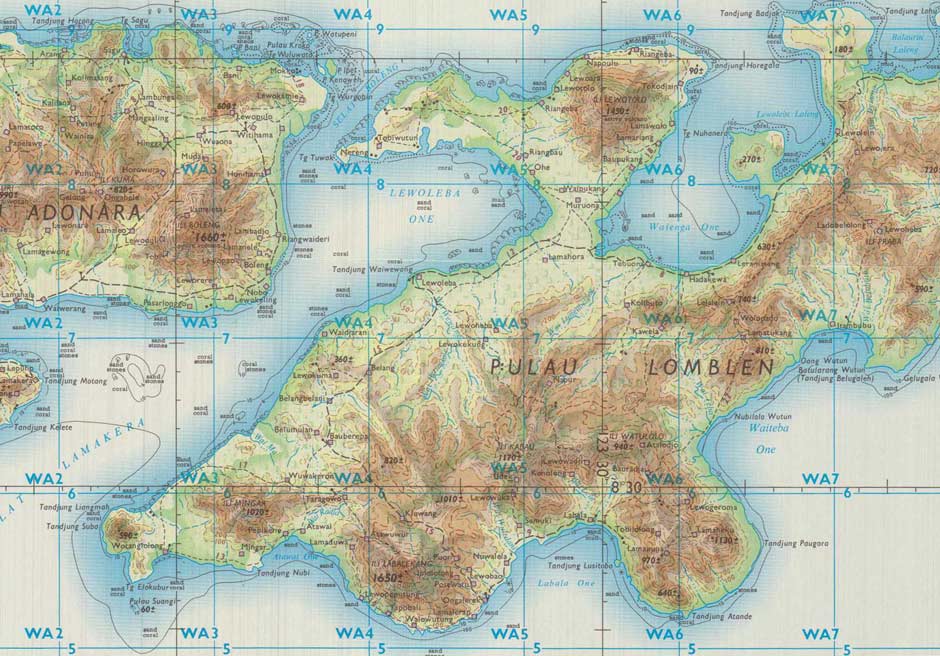

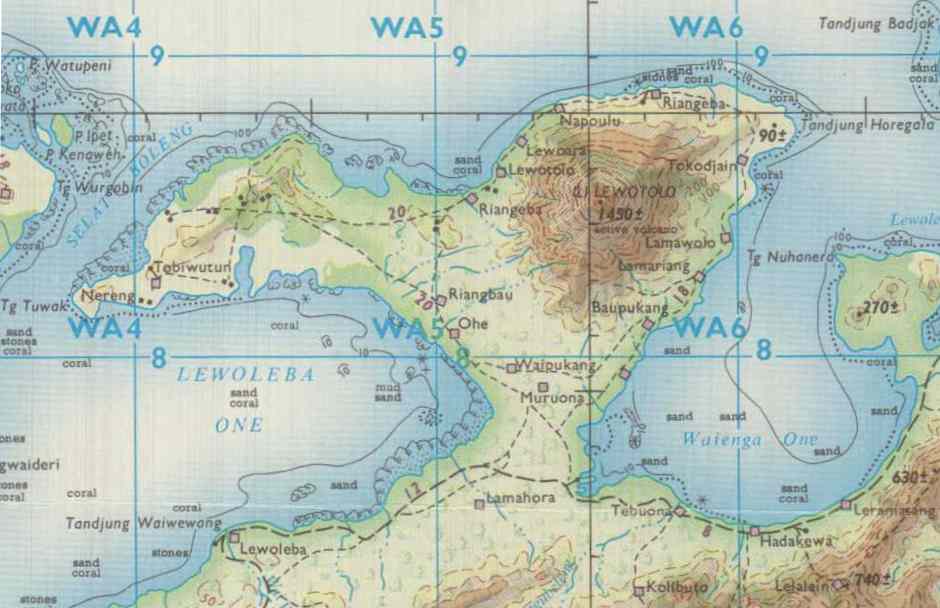

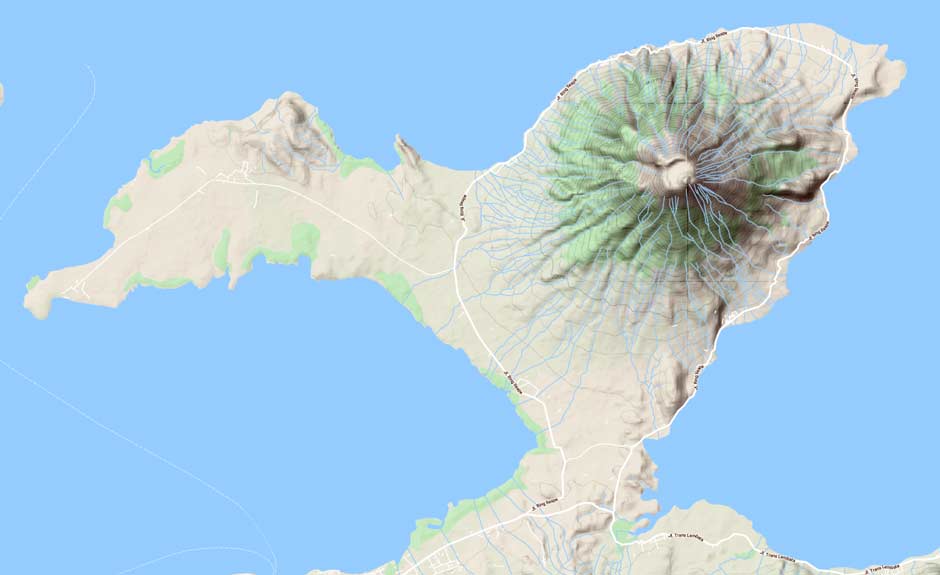

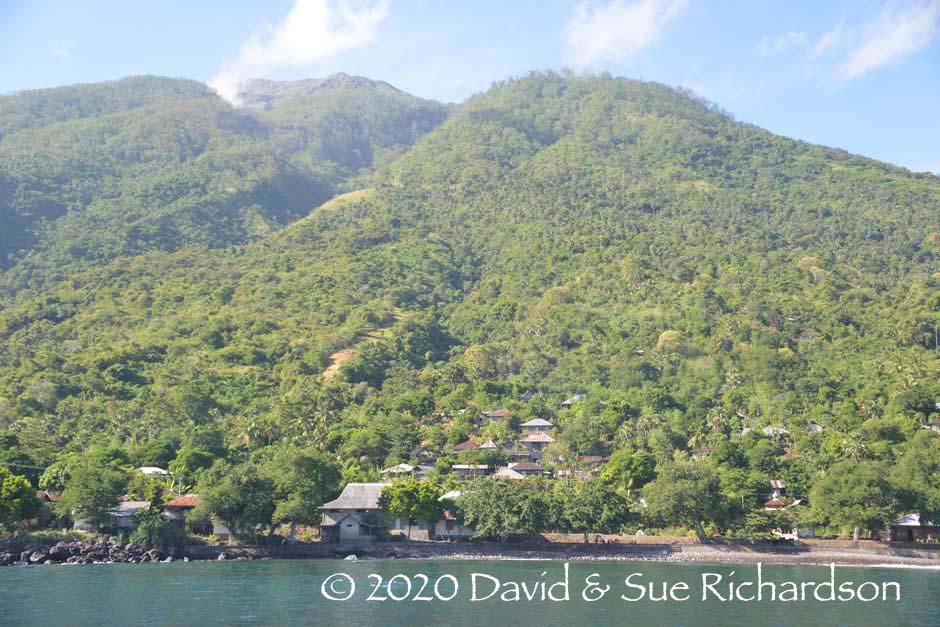

The quietly active stratovolcano of Ilé Lewotolo (with an altitude variously reported as 1423m, 1449m, 1450m or 1455m) is located on the northern coast of Lembata Island, where it has created its own peninsula connected to the mainland by a low-lying neck that partially floods at high tide. It is flanked by Lewoleba Bay and Adonara Island to the west and beautiful Waienga Bay to the east. It is known locally as Ilé Apé or ‘Fire Mountain’ because of its constantly smoking, sulphur-covered crater, although in the past it was sometimes known as Ilé Wariran (Barnes 1996, 21). Eruptions were recorded in 1660, 1819, 1849, 1852, 1864, 1899, 1920, 1951 and 2012 (Siebert et al 2010, 96).

On 11 October 2017 Ilé Apé was struck by an earthquake of magnitude 4.9 on the Ritcher Scale. Ten villages along the north and east coasts were affected and 2,172 residents were temporarily evacuated. About 100 houses were damaged, some by rock falls, 11 seriously (Media Indonesia 2017). Villagers from Lamagute and Waimatan could not return to their villages for a week due to the risk of landslide (ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management).

Above: The northern peninsula of Ilé Apé on Lembata Island (formerly known as Lomblen)

Detail from a 1970 map produced by the Ministry of Defence, UK

Below: Detail of the Ilé Apé peninsula

The terrain of the Ilé Apé Peninsula

(Image courtesy of Google Maps)

Ilé Apé from the neck of the peninsula

Ilé Apé from Waienga Bay at sunset

The first Portuguese explorers to reach the East Indies in 1511 must have been well aware of Ilé Apé as they closely navigated along the north coasts of Adonara, Lembata and Pantar on their way to the Banda Spice Islands (Cortesão 1975, 286-289). A later Portuguese manuscript dated 1624-1625 mentions that Levotolo (Ilé Apé) and Queidao (Kédang) on Lembata and Galiyao (Pantar/West Alor) were inhabited by both pagans and Muslims (Barnes 1982, 408).

One of the earliest descriptions of Ilé Apé was written in April 1660 during a major eruption. As a deception the Dutch commander, Johan van Dam, decided to conceal his fleet of 33 ships at 'Lombatta' prior to the bombardment of Portuguese Makassar. One of the fleet's surgeons, Wouter Schouten, reported that the island had a 'wonder high burning mountain' on its north coast 'standing far above the clouds and billowing from its crown, fire, smoke, sulphur and vapour'. Its terrible crater was filled with fires and snow-white ash rolled down its flanks to the sea. Elsewhere the island had many trees, sand dunes, beautiful cultivated valleys, and pleasant villages (Schouten 1676, 80).

Ilé Apé and Cape Horegala from the northeast

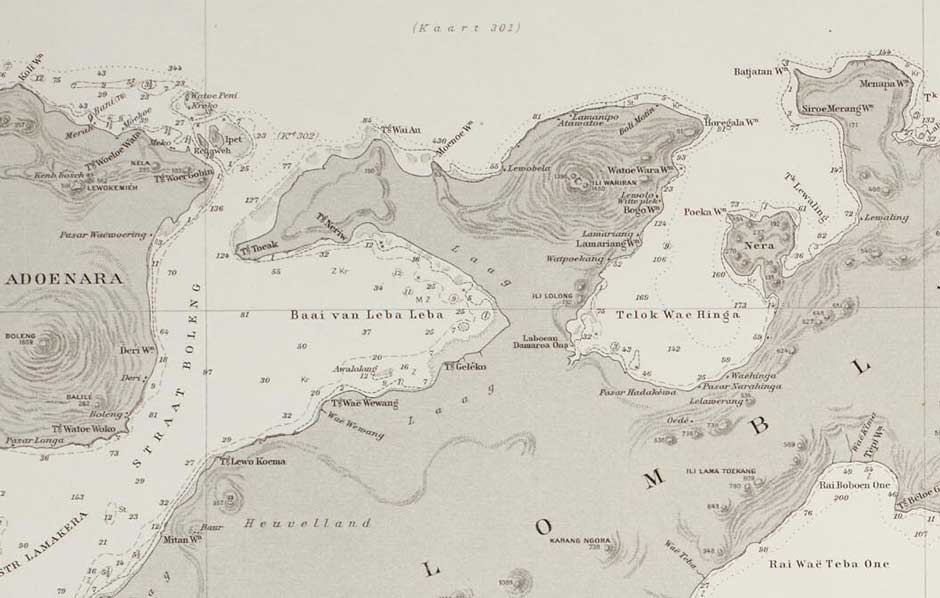

It was only after the Dutch took direct control of the outer islands that we were given a better description of Lembata. In 1910 Captain J. D. H. Beckering landed with a company of troops tasked with registering the population and confiscating their weapons and firearms. He most likely had access to the hydrographic chart produced by the survey vessel Hr.Ms. Opnemingsvaartuig van Doorn in 1908 and 1909:

Ilé Apé from a ‘Nautical Chart of Lomblen’, dated 1911

(Hydrographic Department of the Naval Ministry, The Hague, June 1911)

Beckering was surprised to find that most of the island’s population lived in easily defendable sites on the slopes of the four highest mountains, one of which was Ilé Lewotolo or Ilé Apé (Beckering 1911, 189). There were only a few villages situated around the coast, such as Lamalera, Labala and Kalikur.

The Dutch initially administered the island from Hadakewa in the haven of nearby Waienga Bay. In 1920 they began using corveé labour to construct an unpaved road along the north coast of Lembata, which was not completed until 1935 (Barnes 1996, 49). A Dutch map of 1931 shows that by then an unpaved road had been constructed that completely encircled the volcano, skirting the northern and eastern coasts. During this period the Dutch began to encourage tribal chiefs to relocate their villages from the mountain sides down onto the new coast road.

The small coastal village of Napasabok, formerly Mawa

Looking down on Lamagute and its large Catholic church of Saint Maria Perantara

When Ernst and Hannah Vatter visited Ilé Apé for several days in June 1929 they stayed at Waipukan, just north of the narrow neck of land leading onto the peninsula (1929, 218-219). They observed that the modern coastal villages such as Lewotolo and Napaulung were constructed on terraces, with each house built on its own foundation of stones. Atawatung was a ‘pure’ fishing village where fish were caught using a bow-and-arrow.

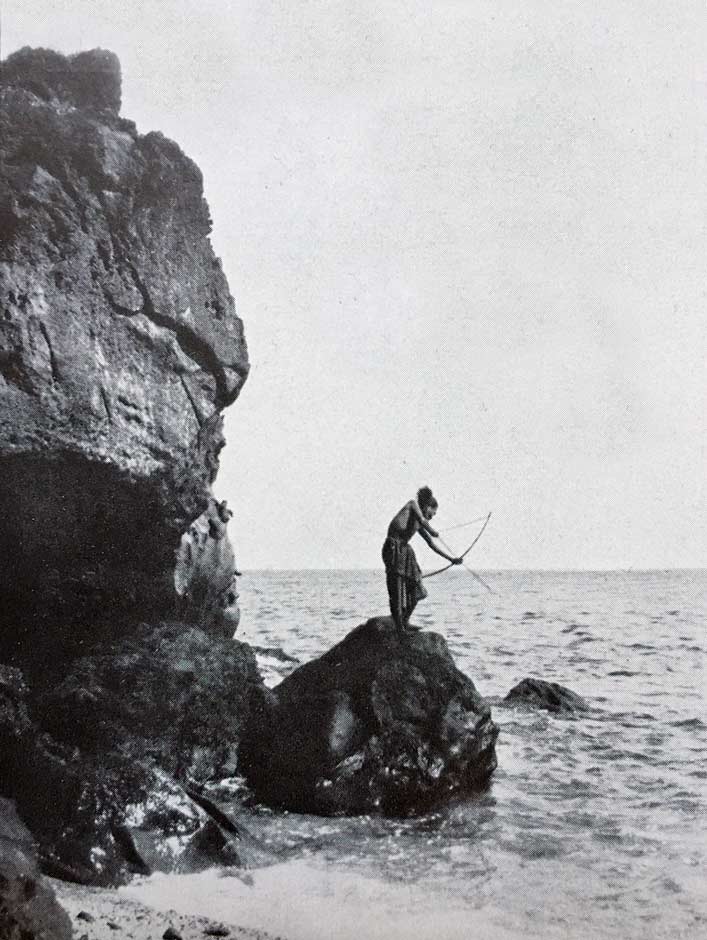

Fishing with a bow and arrow at Atawatung (now Lamagute)

Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Some seven of the original mountain village sites still exist; the largest and most important being Lewohala with around fifty ceremonial clan houses (korke), located 2km north-northwest of Jontona. This is followed by Napaulun, with thirty five clan houses located above Bungamuda, and Watun Lewopito, with eighteen clan houses located just above the modern village of Lamagute, and then finally Lewotolok above Lewotolo. Lewohala was the last traditional village to be abandoned, its population being ordered to relocate during the Suharto era of the 1960s. It is now used for the annual bean festival, which is held every autumn.

The ceremonial village of Lewohala half way up the eastern flank of Ilé Apé

An aerial view of the clan houses at Lewohala

Because of the active volcano, the local water sources are contaminated with sulphur. Although the local government invested in a desalination plant and an associated fresh water distribution system over a decade ago, this was never commissioned and is now defunct. Consequently road tankers must now deliver fresh drinking water from Lewoleba.

Formerly governed as part of East Flores, Lembata became a separate Kabupaten in 1999. Today Ilé Apé is divided into two Kecamatan, Ilé Apé with 17 desa and Ilé Apé Timur with 9 desa.

The Desa of Kecamatan Ilé Apé and Kecamatan Ilé Apé Timur

The Current Desa of Ilé Apé

| Desa | Kecamatan Ilé Apé | Kecamatan Ilé Apé Timur |

| 1 | Amakaka | Aulesa |

| 2 | Beutaran | Bao Lai Duli |

| 3 | Bungamuda | Jontona |

| 4 | Dulitukan | Lamaau |

| 5 | Kolipadan | Lamagute |

| 6 | Kolontobo | Lamatokan |

| 7 | Lamawara | Lamawolo |

| 8 | Laranwutun | Todanara |

| 9 | Muruona | Waimatan |

| 10 | Napasabok | |

| 11 | Palilolon | |

| 12 | Petuntawa | |

| 13 | Riangbao | |

| 14 | Tagawiti | |

| 15 | Tanjung Batu | |

| 16 | Waowala | |

| 17 | Watodiri |

(Source: Klasifikasi Perkotaan dan Persesaan di Indonesia 2010, 112)

Amakaka is the largest village. Unfortunately much confusion has been created by the insane decision of the Indonesian regional government to change the traditional names of all of the villages. Thus for example, Amakaka, Bungamuda, Napasabok, Lamagute, Lamatokan and Jontona were previously known as Lewotolok, Nobolekron, Mawa, Atawatung, Tokodjain and Baopukang. Many elderly villagers still use these names.

The total population of Ilé Apé in 2017 was 17,390, with 7,689 males and 9,701 females. The imbalance arises because many men leave to find work in other parts of the archipelago. In the 1980s many had gone to work as migrant labourers at the port of Tawau in Kalimantan (Barnes 1986, 26). Today the men find work at the Freeport mine in Papua, in Makassar and on Bantam Island.

| Kecamatan | Population 2010 |

| Ilé Apé | 12,311 |

| Ilé Apé Timur | 5,079 |

| Total | 17,390 |

(Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata, 2018)

In terms of official religion, over 75% of the population are Catholic and less than 25% are Muslim. For example, in the village of Napasabok there are 377 Catholics and 73 Muslims. However in Amakaka some 40 to 50% of the population are Muslim. At the same time many people still hold their traditional beliefs in their own supreme deity and the power of the ancestors.

The tiny mosque at Bungamuda

Return to Top

Ilé Apé Ethnography

Ilé Apé is located in the Lamaholot-speaking region of eastern Indonesia, which extends from East Flores to the islands of Solor, Adonara and Lembata. Lamaholot belongs to the Timor subgroup of Central Malayo-Polynesian languages. Lamaholot is not a single unified homogeneous language but rather a family of dialects that in some cases differ so widely that they are mutually incomprehensible. According to the linguist Gregorius Keraf (1978), the people of Ilé Apé speak just one dialect of Lamaholot out of a total of thirty five.

Although Lamaholot is primarily a language, its speakers are often treated as a distinct ethnic group because they have similar social structures, beliefs and rituals.

A banner at YS3L in Lewoleba signifying the unity of spinners and weavers across the Lamaholot region

Descent and kinship is patrilineal, with offspring joining the clan or suku of their father. In the past these sukus were strictly exogamous. Suku are responsible for negotiating marriage alliances and funeral arrangements. A few of these are higher-status clans that have land rights as a result of their ancestors being the first to arrive. Traditionally Lamaholot society was hierarchical, with the nobility, tatkabelan, the commoners, atakabalen, and the slaves, aziana (Melallatoa, 1995, 444). Today, status is determined by different factors such as education, profession, position in the government administration and of course wealth.

The total number of clans or suku on Ilé Apé is probably well in excess of one hundred. Villages differ widely in the number of clans they encompass. The large village of Jontona claims it has thirty clans, whereas in Lamagute there are only seven – Betekeneng, Witak, Watun, Mamik, Making, Berwulo, and Bleker. Betekeneng clan has the highest status because they were the founding clan that arrived first from the islands of Lapan and Batan.

In Napasabok there are at least nine suku: Hurek Making, Lopot Making, Laper Making, Nimanuko, Balawala, Lamarongan, Waolangun, Ladopural and Manuk.

The eastern and southern clans that originated from the old village of Lewohala are divided into two tribal groups:

- wungu bele (the large tribe) is composed of sukus Gesi Making, Tede Making, Duli Making, Beni Making, Do Making, Hali Making, Soro Making, Krowing Making and Laba Making.

- wungu belumer (the small tribe) is composed of sukus Pureklolon, Balawanga, Lamawalang, Matarau, Lebahi, Atanila, Lamatapo and Langodai.

Today young people are generally free to marry anyone they choose. In the past, however, marriage could only take place between couples belonging to clans that had an established asymmetric marriage alliance. Each individual clan would have an alliance with one or more wife-giving clans, known as opulaké or more strictly belaké, and with one or more wife-taking clans, known as opubiné or simply opu. For example in Napasabok, a boy from Manuk had to marry a girl from Hurek.

Wife-giving clans had a higher status than wife-taking clans. Because the system of marriage alliance was asymmetric, these two sets of clans had to be different – if clan B received the daughters of clan A it could not reciprocate by offering its daughters back to clan A since that would be symmetrical alliance. It had to supply wives to clan C.

The terminology relates back to the tradition of cross-cousin marriage, which was considered the ideal form of asymmetric marriage alliance. In this system a son is married to his mother’s brother’s daughter and conversely a daughter is married to her father’s sister’s son. The mother’s brother’s daughter is the son’s closest relative available for marriage from another clan. Opu are affines or relatives related by marriage. A biné is a woman or sister while a laké is a man, husband or brother. Opu belaké (or belaké) refers to the uncle, the mother’s brother who donates his daughter (Barnes 1977, 144). Opubiné refers to the father’s sister who donates her son. Today these traditions are considerably eroded and the younger generation have greater freedom in choosing a marriage partner.

The formation of a new marriage alliance is secured by an exchange of goods negotiated between the belaké and the opu or opubiné. The belaké are obliged to donate bridewealth (belis) in the form of a durable asset – in this region an elephant tusk or bala. The greater the status of the bride, the larger the elephant tusk. In return the opu are obliged to donate a counter-prestation in the form of consumables – textiles and ivory bracelets.

Bapak Lodan, the kepala desa of Jontona, demonstrating how to carry a normal sized elephant tusk at a marriage ceremony

Bapak Lodan, the kepala desa of the large village of Jontona, told us that there were 30 different clans in his village and every one of them possessed elephant tusks. A normal tusk is around two feet in length and is considered to have the same value as a bridewealth sarong. At Lewohala, the original mountain village above Jontona, one of the korke clan houses contains a huge elephant tusk about two metres in length. The villagers consider that this is worth fifteen bridewealth sarongs, and therefore has a market value of around IDR 300 million. Because the traditional textiles from Ilé Apé are valued in terms of elephant tusks, this makes them expensive to acquire.

A huge elephant tusk kept as a clan treasure in a korke at the old ceremonial village of Lewohala

Marriage is patrilocal – the bride moves to the location of the husband’s relatives. However if the bridewealth has not been paid, the husband must live and work in his wife's parents' house.

Traditional beliefs are based around two concepts: the continual influence of the spirits of the deceased ancestors, which can be either positive or negative, and a supreme bipartite deity called Lera Wulan Tana Ekan, Lera Wutan meaning sun and moon, in other words the heavens, and Tana Ekan meaning land and the specific region (Barnes 1996, 159). It is thought that disasters, challenges, illnesses and natural disasters arise when the relationship between humans and nature is disrupted. Harmony can only be re-established by conducting the appropriate ceremonies and rituals.

Ilé Apé rituals are closely linked to two fundamental cycles – the cycle of life from pre-birth to post-mortem, and the annual agricultural cycle of the different crops: rice, corn, long beans, green beans, soybeans, pomegranates, and sorghum. These rituals take place at the korke, the temple located at the centre of the traditional village and the associated meeting place, the raised platform called the koker bale or just bale (Kumhan et al 2016). The nuba nara sacred stones are located in front of the korke in some villages. Some villages also had a sacred wooden pole called a rie lima wana.

Korke clan houses in the old ceremonial village of Lewohala on the eastern flank of Ilé Apé. Note the seven bamboo uprights along the roof ridge

The most important festival is the werung lolong (‘new beginning’) harvest festival, commonly called the bean festival. It is celebrated at Lewohala by 77 suku from seven villages located in the southern part of Ilé Apé – Riangbao, Waipukang, Muruone, Ohe, Kimakama, Waiwaru and Jontona. It takes place at full moon on third or fourth week of September, or in the second and third week of October.

Villagers organising a formal welcoming ceremony in Napasabok

Another widely shared element of Lamaholot culture is the traditional system of leadership, where each village was governed by four ritual leaders (Vatter 1932, 81):

- the kepala Koten was the most senior of the four leaders being in control of internal village affairs including land ownership,

- the kepala Kelen was responsible for external affairs, dealing with neighbouring villages and in the past dealing with the Dutch authorities,

- the kepala Hurit (also Hurin or Hurint ) and the kepala Marang were advisors and mediators if there was a disagreement between the heads of Koten and Kelen.

Other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders became too powerful. Since Independence and the introduction of democratic regional and village government in the early 1960s, their roles have been superseded by an elected kepala desa.

Today the four ritual leaders still play an important role during the ritual sacrifice of pigs. The kepala Koten holds the animal’s head, the kepala Kelen holds the back legs, the kepala Hurit wields the knife while the kepala Marang is responsible for chanting ritual prayers. The animal’s blood is then spread on the village’s sacred nuba nara stone.

Many writers mistakenly interpret the four positions of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang as representing village sukus, but the latter are completely different. Traditionally the leaders from four specific village sukus will have been assigned to the roles of head of Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang. These will be different for every village. However in some villages the less important positions of Hurit and Marang are not represented.

Return to Top

Local Cotton and its Processing

Most of the cotton that grows around the coasts of Ilé Apé is of the tall and lanky tree-like perennial form, Gossypium arboreum. At Napasabok (formerly Mawa) it is grown in gardens located about 2km from the village but at Jontona (formerly Baopukang) it is grown in gardens within the village. Cotton is variously referred to as kapok or kapek but in the local Lamaholot it is known as lelu.

Gossypium arboreum growing in a yard on Ilé Apé

Above and below: Gossypium arboreum and indigo growing side by side in a garden in Jontona

One of the attributes of tree cotton is that it sometimes reverts to a more hardy ancestral variety bearing light rust-coloured fibres, a feature shared with all wild uncultivated cottons. On Ilé Apé this is highly valued. This is because local weavers never incorporate white undyed cotton in their ikat patterns. To ensure a more subdued effect they always pre-dye their white cotton yarns before they bind them with the ikat patterns – generally with light pink from the bark of the réo tree or from one immersion in morinda, or with light beige from an immersion in mango bark. If they use red cotton there is no need for them to pre-dye it.

De-seeding cotton bolls at Napasabok using a malok gin

The weavers pick the bolls and gin them using a crude mechanical roller called a malok, which plucks the fibres from the seeds, a process called bulelu. The cotton seeds are reserved so that they can be planted in the weavers’ gardens during the rainy season between December and February, thus allowing the cotton bolls to mature during the long hot summer. After de-seeding the cotton is then cleaned, fluffed and aerated using a pick and bow, respectively known as a mesil and wuhu, the vibrating cord separating and partially aligning the individual fibres. A few spinners roll the fibres into small cigar-shaped punis (small rolags), known locally as lelu knolot. The latter process is called golo lelu. However most spinners spin from a large handful of fluffed cotton.

Fluffing cotton fibres using a mesil pick and a wuhu bow.

Today cotton production here is very small-scale, barely enough to meet the needs of the weavers. Yet in the past, some raw cotton from Ilé Apé was exported to other nearby regions. Weavers in the village of Uma Pura on Ternate Island, situated between Pantar and Alor, could not grow cotton on their rocky islet. Instead they took their textiles to Ampera on Alor and bartered them for ceramic pots. The pots were then taken by boat to Ilé Apé, where they were bartered for raw cotton. The exchange rate for one pot was the amount of cotton that could be packed into its interior. The raw cotton was sailed back to Uma Pura to be processed into textiles (Wellfelt 2014, 6).

Women on Ilé Apé spin their cotton using a long drop spindle known as a tenue. It has a bamboo or wooden shaft and a whorl made from the wood of the Areca palm. The advantage of a long spindle is that it does not precess – its rotational axis remains vertical and is less likely to wobble. This produces a more even twist. Using a drop spindle also allows the spinner to adjust the width of the yarn from coarse to fine. The process of spinning is known as tue lelu.

Mama Salma Deram drop-spinning in her house at Napasabok

As in many other Lamaholot regions, they do not use mechanical spinning wheels (tenulé) on Ilé Apé, probably because in the past this region was so isolated from external influences. The women far prefer using the drop spindle because they can spin throughout the day, whether walking to market, relaxing or talking with neighbours. They also believe the drop spindle is more productive. Spinning with a spindle is a single process. Local women say that spinning with a wheel is more laborious because it demands double processing of the yarn – after the initial spinning it is necessary to go over the thread again by hand to even out the coarser sections.

Fortunately the tradition of drop-spinning continues on Ilé Apé, with many young girls still taught by their mothers and elder sisters at an early age.

Twelve-year-old Wati Nimanuho, who started drop-spinning at Napasabok when she was just nine-years-old

David with master spinner Julie Tenoa from Bungamuda, who always wins every spinning competition by producing the very finest spun yarn

Drop-spinning while chatting to neighbours at Bungamuda

Unwinding the spun yarn from the drop spindle

Once the spindle is fully loaded with spun yarn, the tip is held between the toes and the yarn is unwound and rolled into a ball. The balled yarn is then wound onto a niddy-noddy, known in Napasabok as a belawai and in Lamagute as a belawa. This not only sets the twist in the fibres, but also allows the weaver to measure the amount of yarn required for binding. By measuring six wraps of the niddy-noddy they have enough warp for one bundle of ikat.

Belinda Benang winding the balled yarn onto the belawai

Commercial yarns are purchased in hanks and are placed on a swift (muter) so that they can be easily rolled into a ball.

Return to Top

Binding

On Ilé Apé, the cotton yarns are normally always pre-dyed prior to binding, so that the undyed parts of the ikat pattern are not a harsh white. This process of pre-dyeing, which can also include starching, is called giri. There is a choice of five methods: using mango bark, réo bark, tamarind pods or turmeric, or simply allowing the morinda to bleed into the bindings. A sixth option is to use natural red cotton.

Morinda-dyed warps separated into bundles of twenty-four yarns prior to binding

The pre-dyed yarns are then stretched on a binding frame and gathered into individual bundles of twenty-four. Sometimes a narrow section is woven to lock them all in alignment, the woven part being positioned over one end of the binding frame. The bundles are then grouped into sections, each section containing the number of bundles needed to create the required ikat band or beleken – 4, 5, 7, or more.

Next the bundles are bound with the required ikat pattern using either traditional strips of dried gebang palm leaf or with plastic string. The patterns are either recalled from memory or sometimes they are copied from a finished textile.

The narrow woven section of warps and the grouping of the bundles into ikat bands

Binding bundles of pre-dyed yarn using strips of gebang palm leaf at Napasabok

Above and below: Belinda Benang binding with coloured plastic string

Knotted warps drying following dyeing with morinda.

Note how they have been locked in alignment by a narrow strip of weaving

Return to Top

Natural Dyes

According to Bibiana B. Rianghepat, the head of the Lamaholot Solidarity Foundation (Yayasan Solidaritas Sedon Senaren Lamaholot or YS3L) in Lewoleba, which supports local weavers, there were up to 55 different natural dyes produced on Ilé Apé. Sadly the recipes for many of these have never been recorded.

Balls of naturally dyed yarns at Bungamuda

Return to Top

Indigo

Wild indigo, known variously as tao, ta’u or taum, spreads like a weed around the rocky coasts of Ilé Apé.

Indigo growing in the village of Napasabok

Local dyers conduct their indigo dyeing towards the end of the rainy season. Dyers mix the wilted leaves with lime powder and leave their yarns in the dye bath for two full days, after which the yarns must be thoroughly dried before the next immersion. For a light blue dye they use three immersions in indigo. To obtain a deep blue that borders on black they repeatedly dye their yarns for up to thirty times.

Indigo dyeing at Bungamuda. Note the leaf impurities in the dye bath

Hanks of hand-spun cotton that have been dyed in indigo up to 29 times, Lamawara

Return to Top

Morinda

In the past morinda flourished on the lower slopes of the volcano. However weavers preferred to harvest roots from a variety of morinda that had smaller fruits and grew in the forests higher above sea level (presumably M. citrifolia var. bracteata). Today morinda is harder to find, and dyers are being encouraged by the local government and NGOs to set aside land for growing morinda and other dye plants. Some weavers now plant morinda trees in their gardens. If a woman does not have enough morinda she can sometimes borrow some from a neighbour.

Morinda growing at Jontona

The aluminium mordant Symplocos is not found on the slopes of Ilé Apé and local dyers have to buy it from fishermen who bring it over from Alor Island. They call it koka, which simply means bark in Lamaholot. The suppliers keep the nature and location of the koka bark a secret to protect their market.

A bowl of koka from Alor next to a bowl of morinda root, Lamagute

The yarns are immersed in the morinda dye bath for two days and are then dried thoroughly in the house for about two weeks. For a medium brown colour they dye their yarns seven times, but for the deepest brown they can repeat dye fifteen times and in some cases for thirty or more times.

Return to Top

Moringa

Dyers on Ilé Apé make a pink dye from the leaves of the moringa tree (Moringa oleifera), which is locally known as kelor. The tree has a fernlike leaf. Dyers mix the moringa leaf with crushed candlenut and boil it in water. When the dye bath is hot they add the yarn. The resulting colour is a pinky-beige.

Return to Top

Réo Bark

A pale reddish-brown dye is produced from the bark of the small deciduous réo (pronounced ‘ray oh’) or Indian Ash Tree (Lannea coromandelica). It is rich in polyphenols including flavonoids and tannins.

A réo tree growing beside by the coastal road around Ilé Apé

The dried bark is crushed between two stones and is then added to water and boiled. The yarns are immersed and left for around an hour. The longer the bath is left to boil, the deeper the colour achieved. After turning off the heat they leave the yarns in the dyebath until it has partially cooled.

Grinding stones for powdering tree bark at Bungamuda

Above: hanks of commercial yarn are added to the réo dyebath

Below: the colour deepens with longer boiling

Return to Top

Tenor Bark

Ruth Barnes referred to a red dye used in Lamalera, locally called tenor (1984, 72-75). It was made from the bark of a tree that grew on Ilé Apé and was purchased at Lewoleba market, a whole 10 litre bowl of tenor exchanged for Rp. 250 or one strip of dried fish. After crushing the bark between two stones it was pounded in a mortar and boiled with lime powder before adding the cotton yarns.

We suspect that the tenor of Lamalera is the same dye bark as the réo of Ilé Apé.

Return to Top

Mango Bark

On Ilé Apé the bark from the evergreen mango tree (Mangifera indica) is only used for pre-dyeing the yarns prior to binding.

Crushed mango bark

To dye with mango the dyers simply boil the crushed bark with water. No other ingredients are required. The cotton yarns are immersed just once, producing a light oatmeal coloration.

Immersing the yarns in the mango bark dyebath

For more information about dyeing with mango click here

Return to Top

Tamarind

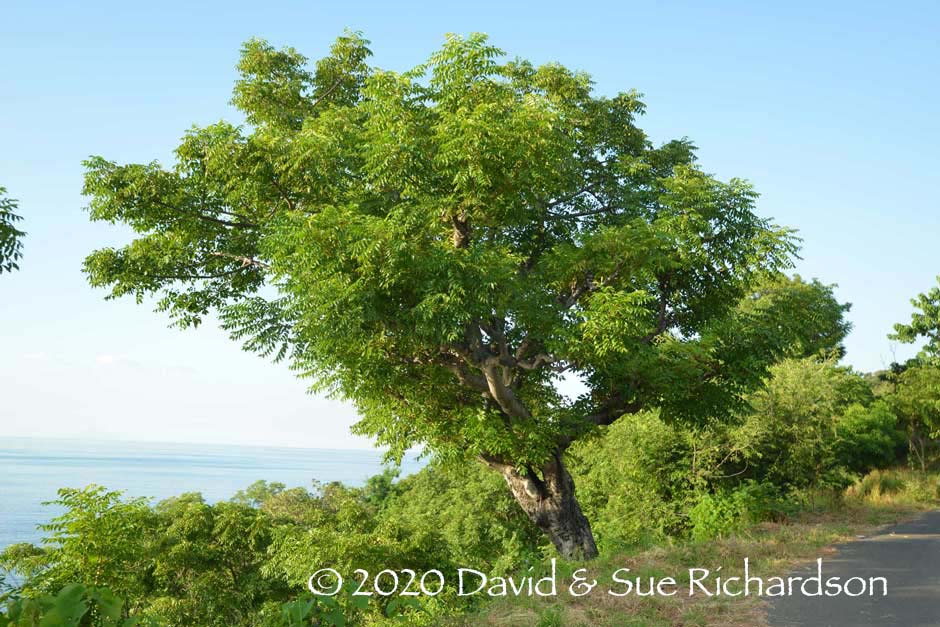

Tamarind is called tobi in Lamaholot and asam in Indonesian. Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) is a large, long-lived, evergreen or semi-evergreen tree that can grow up to 30m in height (El-Siddig et al 2006).

A huge tamarind tree by the beach at Napasabok

For a different background colour in the main ikat bands, the white cotton is sometimes dyed with the boiled casings of tamarind seeds for ten minutes. No lime is added. Weavers believe that tamarind can strengthen the cotton threads and prevent them breaking. The tannins in the tamarind may also have a mordanting effect as well.

For more information about dyeing with tamarind click here.

Return to Top

Natural Black

Although repeated indigo dyeing can produce a very dark blue, it is impossible to achieve a true black with indigo alone. To obtain a true black, the dyers on Ilé Apé finish their deepest indigo-dyed yarns by treating them with a cocktail of tannins.

Boiling roasted tamarind seeds at Bungamuda

The production of the tannin bath is a hot process. The dyers boil ground tamarind seed, powdered mangrove bark and the outer shells of the Java Olive or Wild Almond tree (Sterculia foetida), known locally as kapok or wuka and elsewhere in the Lesser Sunda islands as nitas. The mangrove bark is powdered on a stone slab using a stone pestle. They also add a little lime powder. Once the mixture has cooled, a small amount is scooped into a plastic mug and the indigo-dyed yarns are laid on an old rice sack. The tannin mix is splashed onto the yarns and pushed into the fibres with the knuckles. Once a section has been treated, the yarns are turned and more mix is pummelled into them. After the application of four mugs of tannin solution, the yarns are thoroughly soaked through and are hung up to dry without rinsing.

The dyers emphasise that the yarns must not be immersed into the tannin mixture because this will make them stick together.

Above and below: Mama Maria pummels the tannin mix into her indigo-dyed yarns, Lamawara

Return to Top

Turmeric

Ilé Apé dyers use turmeric, known locally as kunyit, to make three different shades of yellow. In each case they first wet their cotton yarns before immersing them in the dyebath. They begin by boiling chopped kunyit tubers in water to produce the basic yellow dye mix. They use this unadulterated to dye their cotton a golden mustard yellow. By acidifying the dye with the addition of the juice of several limes to the mix, they can obtain a bright light-yellow. However the addition of alkaline lime powder (kapur) to the kunyit bath produces a darker shade of orange-yellow.

Left: unadulterated turmeric. Above: turmeric with lime powder. Right: turmeric with lime juice

Mama Mulia holding up three hanks of wet, turmeric-dyed cotton at Bungamuda. Left: pure turmeric; Centre: turmeric with lime powder; Right: turmeric with lime juice

The colour differences become more muted after drying. Left: turmeric with lime juice; Centre: pure turmeric; Right: turmeric with lime powder

For more details about dyeing with turmeric click here.

Return to Top

Weaving

Women work in their gardens from October/November until April, and then weave from May until September. Weaving is known as tané tenané, tané being the verb to weave and tenané referring to woven clothes.

For a simple undecorated cloth weavers warp up using a basic rectangular frame fitted with a crossbar. The warps are wound over and under the cross bar to form the cross, and the yarn heddle is formed at the same time.

Above and below: Warping up to form the cross and forming the heddle at the same time

For more complex textiles containing plain bands and bands of ikat, the component parts are assembled on a frame without a crossbar and the cross and the heddle are produced by manual manipulation. The dyed ikatted yarns are untied and stretched on a frame so that the pattern can be focussed and then locked in position using interlocked knotted yarns, sometimes supported by a short stick.

Locking the ikat bands for a wate hebaken with wrapping, knotting and in some places sticks

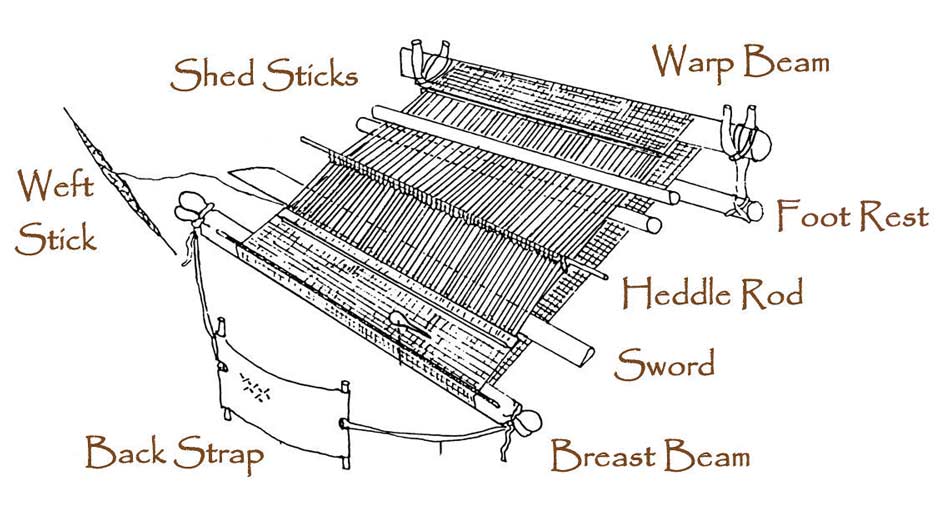

Weavers on Ilé Apé use the typical short Lamaholot frame-braced body-tension loom fitted with a split breast beam. The shuttle is a very long stick with the weft wound on in a helical fashion. They sometimes lubricate the warps by rubbing them with a block of beeswax.

The typical Lamaholot loom

The components of the Ilé Apé loom are as follows:

| Breast beam | Hapit |

| Warp beam | Pola |

| Back strap and yoke | Seligur |

| Stretcher/Temple | Nugi |

| Heddle rod | Gurun kayo |

| Yarn heddle | Gurun kapek |

| Sword | Huri |

| Shuttle | Beloe |

| Shed stick | Wulo |

| Pick | Newa |

(Source: Nursida, the wife of the kepala desa of Napasabok)

The Ilé Apé terminology for the parts of the loom differs from that used in Lamalera and Ata Déi, sometimes widely (Barnes 1984, 309-312). Thus in Lamalera they call the breast beam a tenané, not a hapit, and the warp beam a pola, the same as on Ilé Apé. The corresponding terms used in Watuwawer on Ata Déi are tenané and kebol. It is possible the terms even differ from village to village.

Weaving a tenépa in the shade of an awning at Lamagute

This particular loom is supported by a substantial wooden frame

Mama Salma weaving a modern wate hebaken krokan

Note the very long stick shuttle wound with an indigo weft

Weaving a traditional wate hebaken

Ilé Apé remains one of the few places left in eastern Indonesia where women continue to make high quality textiles using traditional designs, hand-spun cotton and natural dyes. While many mothers still encourage their daughters to drop-spin and weave, there are now so many more opportunities for young women to take up a professional career that few are choosing textile production as a full time occupation.

Ruth Barnes encountered a lot of pessimism about the survival of traditional Ilé Apé weaving in 1984 and at that time commented that her 'own experience bears this out to a certain degree' (Barnes 1984, 210). Clearly her concerns were premature. Nevertheless some thirty six years later we too now worry about how much longer this wonderful artistic tradition can continue. As with Ruth Barnes, we hope our fears prove to be groundless.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Albo, Franscico, 1874. Extracts from a Derrotero or Log-Book of the Voyage of Fernando de Magellanes in Search of the Strait, from the Cape of St. Augustin, Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Anon, 1956. Fundaçâo das Primeiras Cristanades nas Ilhas de Solor e Timor, pp. 475-

Documentação para a história das missões do padroado português do Oriente: 1568-1579, vol. 4, Basílio de Sá, Artur (ed.), Agência Geral do Ultramar, Divisão de Publicações e Biblioteca, Lisbon.

Ansar, Majid, 2018. Belis gading gajah tradisi perkawinan masyarakat Lamaholot di Ile Ape Kabupaten Lembata Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur, S1 Thesis, University of Makassar.

Ataladjar, Thomas B., 2015. Pai Hone Tala Ia, Pai Wane Tele Pia, Lame Lusi Lako dari Tanah Nubanara Menuju Tanah Misi, Koker, Jakarta.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata, 2018. Kabupaten Lembata Dalam Angka, Lewoleba.

Barbosa, Duarte, 1866. A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the beginning of the Sixteenth Century, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Barnes, R. H., 1977. Alliance and Categories in Wailolong, East Flores, Sociologus, New Series, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 133-157.

Barnes, R. H., 1979. Lord, Ancestor and Afine: An Austronesian Relationship Name, NUSA, vol. 7, pp. 19-34,

Barnes, Robert. 1982. The Majapahit dependency Galiyao, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 138, pp. 407–412, Leiden.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989a. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989b. 'The Bridewealth Cloth of Lamalera, Lembata', in To Speak With Cloth: Studies in Indonesian Textiles, Gittinger, Mattiebelle, (ed.), University of California, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 1991a. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 2, pp.95–112.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Fragile Traditions: Indonesian Art in Jeopardy, University of Hawaii Press.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010a. Woman’s Tubular Skirt: Porso Toraja Region, Sulawesi, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 254-255, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010b. Woman’s Bridewealth Tubular Skirt, watek ohing Ili Api, Lembata, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 346-347, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Beckering, J. D. H., 1911. Beschrijving der eilanden Adonara en Lomblem, behoorende tot de Solor-Groep, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2e Série, vol. 28, pp. 167-202.

Bolland, Rita, 1977. Weaving the Pinatikan, a warp-patterned Kain Bentenan from North Celebes , Studies in textile history : in memory of Harold B. Burnham, pp. 1-17, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Donselaar, W. M., 1882. De Christelijke zending in de residentie Timor, Mededeeling van mege het Nederlandsche Zendinggenootschap, vol. 21, pp. 269-89, Rotterdam.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2015. Tracing Ancient Networks; Linguistic, Hand-woven Cloths and Looms in Eastern Indonesia, Ancient Silk Trade Routes, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte, Ltd., Singapore.pp. 53-

Fricke, Hanna, 2017. Nouns and pronouns in Central Lembata Lamaholot (Austronesian, Indonesia), Wacana, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 746-771.

Fricke, Hanna and Klamer, Marian, 2018. Reconstructing Linguistic and Social Histories of the Lamaholot region, Seventh 7th East Nusantara Conference, Kupang.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2019. Traces of language contact: The Flores-Lembata languages in eastern Indonesia, Ph. D. Thesis, Leiden University.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2020. Personal communication.

Grangé, Phillipe, 2015. The Lamaholot dialect chain (East Flores, Indonesia), Language Change in Austronesian languages, Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Canberra.

Guy, John, 1998. Woven Cargos: Indian Textiles in the East, Thames and Hudson, London.

Hudjashov, Georgi; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Lawson, Daniel J.; Downey, Sean; Savina, Olga; Sudoyo, Herawati; Lansing, J. Stephen; Hammer, Michael F. and Cox, Murray P., 2017. Complex Patterns of Admixture across the Indonesian Archipelago, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 2439–2452, Oxford University Press.

Hull, Geoffrey, 1998. The Basic Lexical Affinities of Timor’s Austronesian Languages: A Preliminary Investigation, Studies in Languages and Cultures of East Timor, vol. 1, pp. 97-174, University of Western Sydney, Macarthur.

Hull, Geoffrey, 2006. Timorese Plant Names and their Origins, Monografias do Instituto Nacional de Linguōstica (Timor-Leste), no. 1, Instituto Nacional de LinguÌstica.

Irwin, John, 1955. Indian textile trade in the seventeenth century: 1. Western India, The Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. 1, pp. 15-44, Ahmedabad.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/lama1277-ileap

Kleiweg, J. P., 1931. Quelques crânes de l’île Lomblen (Archipel Indien), Anthropologie, vols 9-10, pp. 129-143.

Lianurat, Antonius Buga, (Antoni Lebuan), Head of Culture, Lembata Culture and Tourism Office, 2013 – 2020. Personal communication and translation.

Lundberg, Anita, 2003. Voyage of the Ancestors, Cultural Geographies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 64-83.

Melalatoa, Junus, 1995. Ensiklopedi Suku Bangsa di Indonesia Jilid L-Z, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Michels, Marc, 2017. Western Lamaholot: A cross-dialectal grammar sketch, MA Thesis, University of Leiden.

Nagaya, Naonori, 2011. The Lamaholot Language of Eastern Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, Rice University, Houston, Texas.

Pires, Tomé, 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, vol. 1, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Prakash, Om, 2009. Indian Textiles in the Indian Ocean Trade In the Early Modern Period, The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1984. Clothing, Ritual and Society in Tenganan Pegeringsingan (Bali), Verhandlungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Basel, vol. 95, pp. 191-241.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1991. Balinese Textiles, British Museum Press, London.

Rutan, Margarita I. M.; Daga, Lukas Lebi and Wutun, Monika, 2018. Studi Etnografi Makna Komunikasi Ritual Adat Werung Lolong pada Masyarakat Lewohala di Desa Todanara, Kecamatan Ile Api, Kabupaten Lembata, Provinsi Nusa Tenggarah Timur, pp. 1149-1163,

Schoutens, Wouter, 1676. Oost-Indische Voyagie, Jacob van Meurs and Johannes van Someren, Amsterdam.

Siebert, Lee; Simkin, Tom, and Kimberly, Paul, 2010. Volcanoes of the World, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Sumber Group Orang Baopukang, 2015. Sejarah Kampung Adat Lewohala, Kompasiana 25 June 2015: https://www.kompasiana.com/sandro.wangak/550b24cd813311df78b1e503/sejarah-kampung-adat-lewohala

Ten Kate, H. F. C., 1894. Een en ander over anthropologische problemen in Insulinde en Polynesië, Feestbundel aangeboden aan Dr. P. J. Veth, Leiden.

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of our friends on Ilé Apé, including its many incredible spinners, dyers and weavers, for answering the many questions we have asked over the past fifteen years, as well as Tony Lebuan, who we first met in Larantuka in 2013. We could not have written this webpage without their help.

Publication

This webpage was published on 2 February 2020.