Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Pantar Island

Geography

Economy

Narratives Describing the Founding of Pandai and Muna Seli

Narratives Describing the Introduction of Islam

Early History

Colonial History

Modern History

The Chiefs of Pandai, Baranusa and Blagar

Languages

Ethnography

Bibliography

Scholarship

Pantar Island

Pantar is one of the most isolated and least known islands of eastern Indonesia. Throughout the colonial period Pantar was always in the shadow of its larger and more populous neighbour, Alor, and little has changed since Independence. Although easily reached from Alor Kecil or Kalabahi by small ferryboat, the island has virtually no infrastructure. Its roads are in a terrible condition, so movement between villages is difficult - even by motorcycle. Travel between coastal villages is best undertaken by sea. Only recently has a project started to build a modern road linking the villages located along its eastern coast.

The linguist Gary Holten has described Pantar Island as ‘truly out of the ordinary, an outlier in the extremes of human habitation’ (2011, 144). Civil servants are reluctant to take assignments on Pantar, while ordained clergy routinely abandon their posts on the island. More than half of the indigenous population has migrated elsewhere, while many families who reside on the island maintain households off-island and only return at key points during the agricultural cycle.

Villagers in ceremonial costume at the Di'ang-speaking hamlet of Tamakh on the east coast of Pantar Island

The textiles of Pantar are some of the least documented in Indonesia despite the fact that the production of warp ikat textiles was once, and in many cases remains, widespread among the island’s coastal communities as well as those on three of the four offshore islands located in the middle of the Pantar Strait. Although Pantar textiles have some similarities to the weavings of the islands of Alor, Lembata and Solor, there is a wide variation in styles, with no obviously proscribed patterns.

Return to Top

Geography

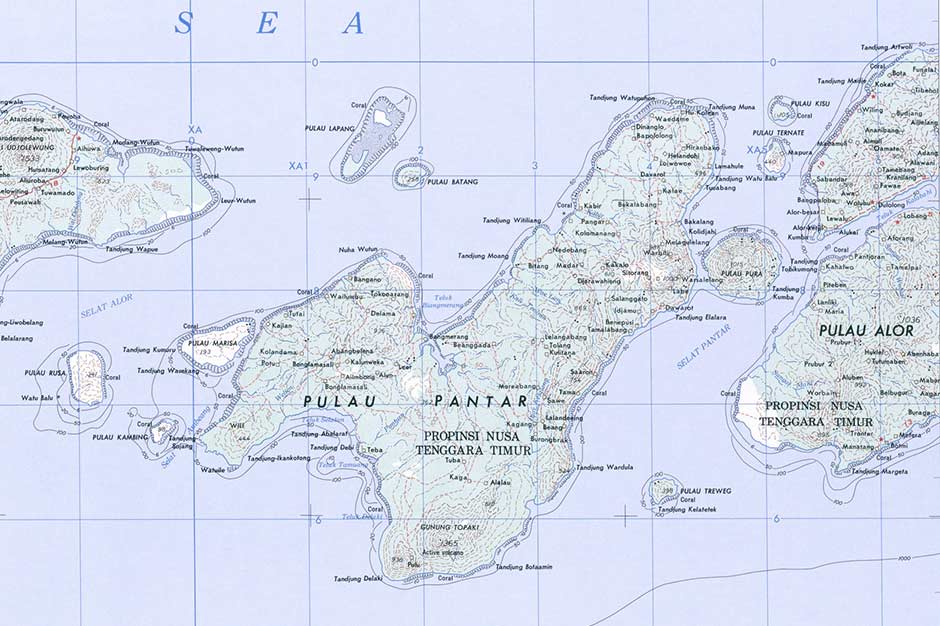

Rarely visited Pantar Island is just 46km wide and approximately tick-shaped (✔). It lies between the islands of Lembata and Alor, separated from each by the Alor Strait and the dangerous Pantar Strait respectively. The Flores Sea lies to the north, while the Savu Sea is to the south. Timor is located 80km south on the other side of the Ombai Strait.

The Pantar Strait contains the four small islands of Kisu (locally referred to as Buaya or Crocodile Island because of its appearance), Ternate, Pura and Tereweng. The islands of Lapang and Batang lie in the northern part of the Alor Strait, while the islands of Marisa, Kambing and Rusa lie in the southern part of the Alor Strait.

Map of Pantar Island, positioned between Lembata to the west and Alor to the east

(Image courtesy of the US Army, Washington, D. C.)

Ternate Island with the aptly named Buaya or Crocodile Island beyond

Pantar Island lies on the Sunda Arc, the elliptical chain of volcanic islands that run from Sumatra through to Banda. The island has six independent volcanic vents only one of which, Kukka Sirung, remains active today (Brouwer 1919). Although the last noteworthy eruption occurred in 1970, regular potent gas and ash eruptions have taken place since 2004 - the biggest in 2012. Eastwards from Pantar volcanic activity subsides until one reaches active Wurlalai on Damar, the intermediate volcanoes on Alor, Kambing, Wetar and Romang all being long dormant.

Pantar has two distinct geographic and climatic zones. The eastern peninsula, about 30km long and 10km wide, is orientated to the northeast and dominated by a ridge of mountains up to 700m in height that slope steeply down to the coasts. This is isolated from the western part of the island by lava flows and steep canyons that severely restrict movement across the island. The western part of Pantar has a stratovolcano complex at its southern end, with the dormant completely forested peak of Kukka Delaki (1372m), and the adjacent active volcano of Kukka Sirung (862m) which has a 2km-wide caldera containing an acidic super-saline lake. To the north lies a low plain with an elevation of up to 200m and a range of hills with active volcanic vents. Brine from Kukka Sirung surfaces in several locations across western Pantar, contaminating the water table.

Aerial image of Pantar Island, with West Alor to the east, separated by the Pantar Strait and the islands of Kisu or Buaya, Ternate, Pura and Tereweng (Image courtesy of Google Earth)

The topography of Pantar Island, highlighting the differences between East Pantar and West Pantar (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

The narrow channel between eastern Pantar and Pura Island

Eastern Pantar looking south towards Kukka Delaki

Despite being hot and humid, most of Pantar has a parched and dry landscape – indeed the island is one of the driest regions in Indonesia. Just as in northern Australia, the primary forests are eucalyptus. The short rainy season is mainly confined to January and February. During the dry season, all of the wells in western Pantar become contaminated with volcanic brine or seawater.

A small coastal kampong on East Pantar

The road from Baranusa to Mauta, West Pantar

(Image courtesy of Edyra Guapo, Denpasar)

Politically Pantar is part of Alor Regency, which was established in 1958. Alor is divided into seventeen districts or Kecematan, five of which are on Pantar. From west to east these are: Pantar Barat Laut, Pantar Barat, Pantar Tengah, Pantar and Pantar Timur. In addition, Pura Island is regarded as a separate district - Kecematan Pulau Pura. There is therefore no political body that represents the whole of Pantar Island.

The view towards southwest Pantar from Nuhawala

Pantar has a mixed population of Muslims, who mainly live on the coast, and Protestant Christians, who mostly but not always live in the interior. The relationship between both communities is one of close brotherhood (see Gomang 2006).

A small Protestant church on Pantar

Masjid At Taqwa at Lamahule

Return to Top

Economy

Pantar remains extremely undeveloped, even compared to Alor. It is one of the poorest islands in the poorest province of Indonesia - NTT. It has only a handful of cars, very poor dirt roads and no airport, although an airstrip has recently been built at Kabir but with no plans for it to become operational.

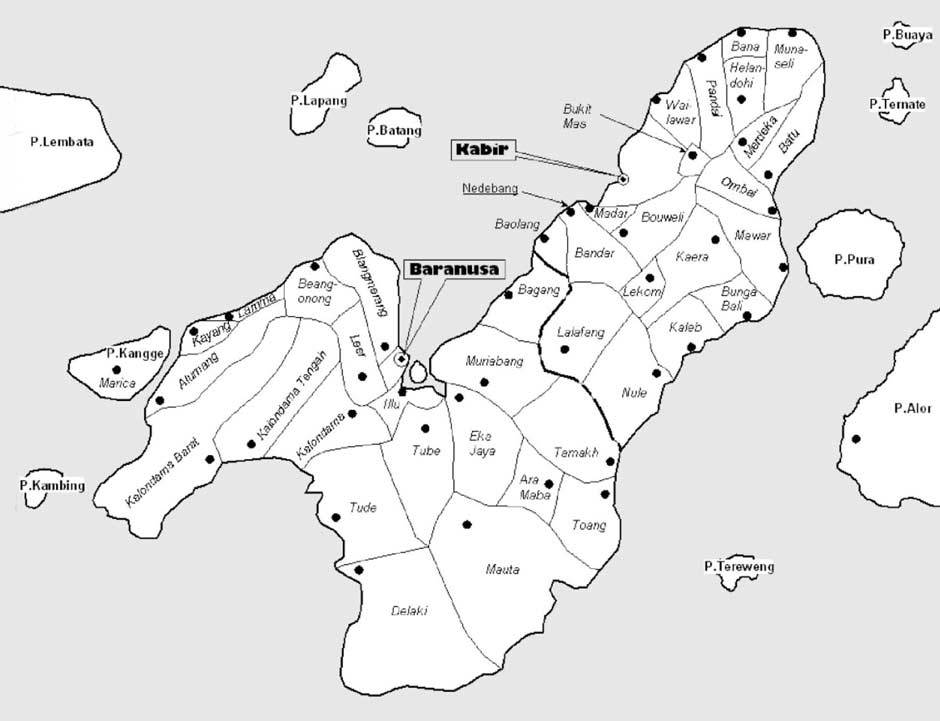

The population of Pantar was 42,557 in 2017 (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor 2018). The main town and port of Baranusa, tucked away in Blangmerang Bay on the north coast, is the only protected harbour on the island and provides the main connection to Kalabahi on Alor, although smaller ferries serve the second largest west-coast village of Kabir and several other villages located along the east coast.

Ferries from Alor Kecil docked at the tiny landing of Muna Seli in northeast Pantar

The island’s economy revolves around slash and burn farming and coastal fishing.

The primary agricultural crops are hill rice, maize, cassava and sweet potato and to a lesser extent millet (Holton 2011, 146-147). Farming activities follow the annual climatic cycle, which is divided into distinct dry and rainy seasons. Staple crops of rice and maize are planted at the start of the rainy season in December with the harvest occurring in March and April. Although the heaviest rainfall occurs in January and February, the impermeable volcanic soils retain little moisture. Consequently virtually no crops are grown during the dry season between June and November, which experiences little or no rain. Agriculture follows a shifting cultivation system, with fields being rotated every three to five years. After being left fallow for a number of seasons the fields are cleared and burned during August and September in time for planting.

As on Savu and Rote, lontar palms are cultivated for their sap, which provides a vital source of liquid on such a dry island. Some of the sap is fermented into a palm wine called tua. The cultivation of coconut palms is limited by the dry soil. The most important cash crop is the cashew nut, which was introduced in the mid-1990s, however most plantations are small.

The most important livestock are pigs and chickens. Pigs are not only essential for certain ceremonies such as marriages, funerals and house completions, but are also required to feed the agricultural working groups organised by clans or extended families to clear the fields and to bring in the harvest. Rice fields are owned by individual families or descent groups, but the labour-intensive tasks of clearing, planting, and harvesting are undertaken by larger work parties.

Pantar Island has 38 coastal villages of which just under half are dependent on marine resources as their main source of livelihood (Fitriana and Stacey 2012). While the men catch fish at sea in canoes or motorised perahus, the women contribute by using fish traps and collecting shellfish and trepang. More recently efforts by the local government and NGOs has encouraged the development of seaweed farming along the north coast.

The lack of local employment opportunities forces many Pantar residents to seek short-term employment in Kalabahi on Alor or further afield. In west Pantar, as much as half of the adult population may be resident in Kalabahi outside of the three main agricultural seasons - field clearing and burning, planting, and harvesting (Holton 2011, 147).

The desa or village districts of Pantar Island

On Pantar every desa or ‘village’ now has a primary school. However secondary schools are only found in the larger towns such as Baranusa and Kabir on the west coast and Tamalabang on the east coast. Consequently many residents continue to send their children to Kalabahi for secondary school education. These towns also have one or more shops, and a health care centre (puskesmas). There is one bank on the island, in Baranusa (West Pantar). Marian Klamer reported in 2010 that there was still no post office, hospital, hotel or restaurant on Pantar (Klamer 2010, 7). There are now several small homestays in Baranusa and Alor Divers Eco Resort, a dive centre with seven beach bungalows located just 2km south of Muna Seli.

Many Pantar villages still lack electricity and have limited access to mass media although satellite receivers are now found in some villages. Telkomsel cellular telephone coverage has existed since 2008.

Return to Top

Narratives Describing the Founding of Pandai and Muna Seli

One local legend reported in Anonymous (1914, 77) claimed that a colony of immigrants from Djawa settled at Pandai on the north coast of Pantar some 600-700 years ago – Djawa being a generic term not necessarily referring to Java but to any unnamed foreign destination (Klamer 2012, 101). Two brothers, Aki Ai and his younger brother Mojopahit, sailed to Pantar, where Aki Ai treacherously abandoned Mojopahit. Mojopahit eventually had five sons who founded five kingdoms: three on Pantar including Pandai and Baranusa, Alor Besar on Alor and Labala on Lembata.

Another legend claims that between 1300 and 1400 Javanese immigrants allied themselves with Pandai to destroy the neighbouring powerful kingdom of Muna Seli, located at Tanjung Muna (Cape Muna). After killing its king, the population were forced to flee in different directions, some settling at Alor Besar (Klamer 2012, 101-102).

Susan Rodemeier collected a long rambling myth on Pantar about the creation and destruction of ‘Munaseli’. It was recounted to her by Bapa Hibu from the Being Aring clan of Helangdohi at Pandai (2006, 268-272).

The Raja of Pandai had seven wives but no children. He gave the wives seven bananas to eat, but the six eldest wives ate them all, leaving only the skins for the youngest wife to consume. Despite being bullied and underfed, only the youngest wife became pregnant. The other wives were jealous and, after gouging out the youngest wife’s eyes, ordered a servant to murder both her and her infant boy who was named Klepo. Instead the servant took them to a tree that bore fruits and a hole that held rainwater throughout the year.The child grew up and learned to hunt with a bow and arrow, catching lizards and quail. One day Klepo went to visit his grandfather, Ula Being (‘Big Snake’), in the village of Kumo Onong. After he arrived Klepo decided to climb a coconut tree to take a coconut. Suspecting that someone was in his plantation, Ula Being arrived and called up to the boy to come down. Then Ula Being turned into a snake and climbed the coconut tree, attacking the boy. Klepo wound the string of his bow around the neck of the snake and nearly killed it, letting it go at the final moment. The serpent changed back into the old man.

Together they made their way back to the village with the coconut, where Ula Being’s wife prepared a meal. Bapa Ula Being offered Klepo a moko, or a gong, or gold and silver, but Klepo only wanted a cockerel. Klepo then recounted the story of what had happened to his mother and how she had been blinded. Ula Being told Klepo to take the rooster and seven grains of rice. If the rooster eats the grain and then crows, your mother will be well again.

Klepo took the rooster, which ate the grain and then crowed seven times. Suddenly the city of Munaseli appeared with people, police, soldiers and gold and silver. Klepo’s father, the Raja of Pandai, arrived at the city and found that his son Klepo had become Raja Talibura, the ruler of Munaseli while his younger sibling named Kosang Bala became Raja Muna.

Now Pandai planned an attack on Munaseli. They first sent their ambassador, Serang Babu, to assassinate Raja Talibura. However once he arrived in Munaseli, five foreign ships (from Jawa) appeared and their occupants murdered Serang Babu. When the killers realised that they had not killed the ruler of Munaseli, they sought out Raja Talibura and stabbed him in the stomach. The population of Munaseli fled, some travelling as far as Manututu in East Timor.

Return to Top

Narratives Describing the Introduction of Islam

There are several local legends describing how Islam was brought to Pantar and neighbouring Alor. One srelates how Islam was initially brought to Baranusa on Pantar by a mubalig or missionary from Ternate Island in Maluku named Mukhtar Likur.

Different legends from Pandai, Baranusa and Alor also point towards Islam arriving from Ternate. They say that Islam was introduced by five missionaries who sailed from Ternate on board the sailboat Tuma Ninah. They were all brothers and were named Iang Gogo, Kima Gogo, Karim Gogo, Sulaiman Gogo and Yunus Gogo. Iang Gogo settled at Alor Besar on the west coast of Alor, Kima Gogo at Lerabaing on southern Alor, Karim Gogo on Ternate Island between Pantar and Alor, Sulaiman Gogo at Pandai on northernmost Pantar and Yunus Gogo at Baranusa on western Pantar (Firmansyah 27.01.17). Evidence supporting this story is provided by an old Arabic Quran, which is hand-written on bark paper, and a circumcision knife, both kept in a house at Alor Besar and said to have been brought to Alor by Iang Gogo. It is interesting that the conical island to the north of Pura is named Ternate – it looks like a miniature version of Ternate Island in Maluku.

The wood bark Quran, said to have been brought to Alor Besar by Iang Gogo from Ternate, Maluku

According to a different narrative from Pura Island, Muna Seli was the first domain on Pantar to adopt Islam but after a war with Pandai its ruling nobility fled, some settling at Alor Kecil and others on Lembata.

A Blagar legend says that Islam was brought by three Muslim scholars – Abdullah Husain from Java and Usman Berkat and Sultan Mar from Makassar. Sultan Mar was eventually taken away by a fleet of kora-kora that were sent to find him, possibly from South Sulawesi (Gomang 1993, 44-46).

One final legend from Hulnani, near Alor Kecil, proposes that Islam was introduced from Java. Shortly after its introduction, a young Hulnani man called Boilelang was sent to Gersik to study Islam. He returned as Najamuddin and constructed a mosque, which still exists today.

Return to Top

Early History

We do not know when and how the first Papuan people settled on Pantar. Archaeological excavations at the Tron Bon Lei rock shelter on the south coast of Alor Island near Lerabaing show that the region was already inhabited in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene (20,000 to 10,000 BP) by mobile hunter-gatherers who subsisted on catching reef fish (Samper Caro, O’Connor et al 2016). They produced fishhooks, which were undoubtedly highly valued – from seashells. At one spot six shell fishhooks had been placed beside a human skull (Bellwood 2017). The widespread use of obsidian stone tools shows that these communities were already actively trading with other parts of the archipelago at this early time (Reepmeyer, O’Connor et al 2016).

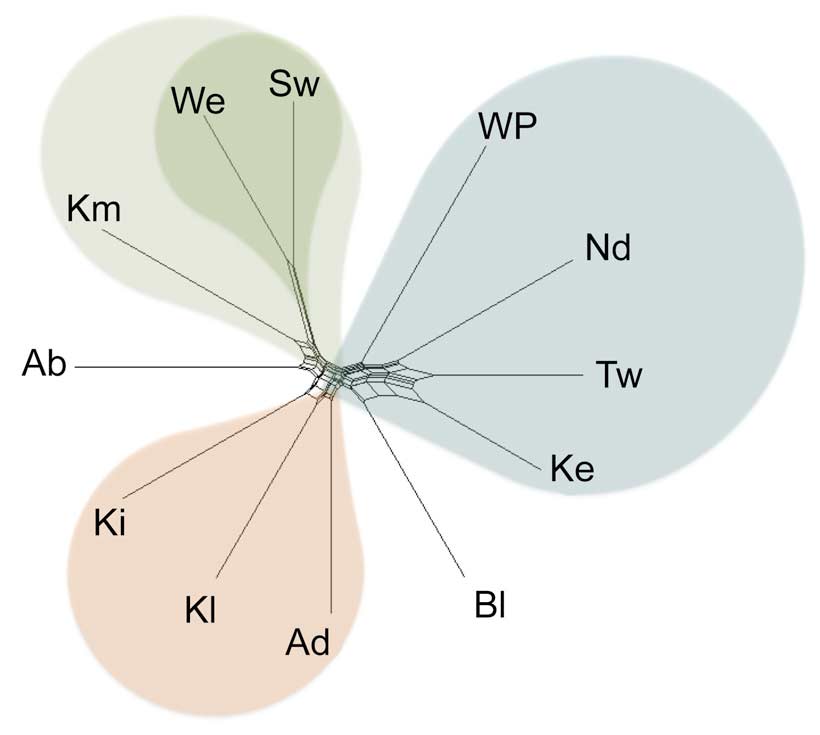

The twenty or so Papuan languages of Alor and Pantar form a discrete relatively isolated subgroup of the Timor-Alor-Pantar language family (Schapper et al 2012). Linguists have proposed that they evolved from a single proto-Alor-Pantar language spoken by the first human settlers. A recent phonological and linguistic analysis of twelve of these Alor-Pantar languages has shed light on their possible dispersal (Holton and Robinson 2017).

Ten of the twelve languages fall into three distinct clusters:

- West and Central Pantar – Kaera (Ke), Teiwa (Tw), Nedebang (Nd), and Western Pantar (WP)

- Western Alor – Kui (Ki), Klon (Kl), and Adang (Ad)

- Eastern Alor – Kamang (Km), Sawila (Sw), and Wersing (We)

However Blagar (Bl) and Abui (Ab) stand out as isolates.

Blagar sits between the languages of western Pantar and those of western Alor

(Analysis of cognates or common words by Holton and Robinson 2017)

Phonological innovations show the greatest degree of diversity on Pantar, suggesting a long history of settlement there (Holton and Robinson 2017). Lexical innovations suggest an original settlement in the Pantar Strait with a very early split towards Pantar. The implication is that the original settlement was in the region of the Pantar Strait where Blagar is spoken today – an ideal location for a settlement of fisherfolk. From there they spread both westward and eastward. As they dispersed into Alor, new lexical innovations were restricted to smaller and smaller subgroups in the east.

Surprisingly Blagar is an exception, being only weakly related to the other Pantar Strait and Pantar Island languages. It appears as though Blagar, as well as Adang, are more recent languages although we do not yet understand why.

As the maritime trading network expanded over the millennia, Alor and Pantar became the beneficiaries of long-distance trade. Some 56 Dong Son bronze drums from southern China or north Vietnam have been identified across the Indonesian Archipelago, probably arriving between 300 BC and 200 AD (Bellwood 2007, 278). One, a large Heger Type I drum, was found at Kokar in northwest Alor as late as 1972 (Museum of 1,000 Mokos). The presence of mid-sized hourglass-shaped Pejeng drums in the Alor region is evidence of long-distance trade with Hindu Bali in the late first millennium AD (Calò 2009, 155). One of these, locally called a moko pung, is located at Hirangbako on the Tanjung Muna peninsula of Pantar (Rodemeier 2006, 63).

Heger Type I drum from Kokar in the Museum of 1,000 Mokos, Kalabahi

Recent archaeological excavations conducted by Sue O’Connor and her colleagues at cave sites on the west coast of Pantar have identified the existence of two-thousand-year-old pottery making activities (Labuan 2018, personal communication). The identification of similar pottery making on the coast of Kedang dating to about one and a half thousand years ago suggests that there was a migration of pottery making communities from Pantar to Lembata during the first half of the first millennium.

In 1292 the Hindu Majapahit state emerged from the former kingdom of Singhasari in the Brantas Valley of Eastern Java. As it gained economic and military strength on the back of rice culture and maritime trade, it began to extend its influence throughout the Indonesian Archipelago. In 1343, the Majapahit grand-vizir, Gajah Mada, finally subjugated Bali following a long military campaign turning it into a vassal state. Some years later he led a powerful naval expedition eastwards, conquering much of Nusantara. The Nāgara-Kěrtāgama chronicle, written in Bali in 1365, lists those countries east of Java that were tributaries of Majapahit, including Bali, Lombok, Bima, Solor, Galiyao and Selayar, Sumba, Timor, Ambon, Seram, and Maluku (Pigeaud 1960, III, 17; Pigeaud 1962, IV, 34). Galiyao is today recognised as Pantar Island. The term appears to be derived from Gale Awa meaning ‘living body’, possibly a reference to its active volcano (Holton 2010).

Unlike Bali, distant Pantar did not become an integral part of the Majapahit State although its leaders may have been obliged to formally declare allegiance at court and possibly supply military manpower to Java.

Legends that immigrants from Djawa established a colony on the north coast of Pantar and founded numerous local kingdoms may have become conflicted with the arrival of Majapahit forces from Java. Linguistic research suggests that these Djawa immigrants were not settlers from Java, but rather Lamaholot speakers who arrived from the west during or before the 14th century – possibly from the Kedang region of Lembata Island (Klamer 2012, 102). The Majapahit Javanese appear to have arrived at a time when these immigrants had already settled in small enclaves along the north coast of Pantar, especially at Pandai and Munaseli on the northernmost cape of Tanjung Muna, the location of the mythical Munaseli kingdom (Klamer 2012, 102). It seems probable that the legends reflect a real conflict between these newly settled immigrant communities. In the early 15th century at least one group fled from Pantar to settle at Alor Besar on the opposite side of the Pantar Strait in western Alor. Some may have continued as far as eastern Kolana (Rodemeier 2006, 69). Others may have settled at Kedang and Hadekewa in Waienga Bay on Lembata (Barnes 2001, 279).

From the 13th century onwards, professional Arab teachers, many of them Sufis, began to introduce Islam into the Malay Archipelago (Azra 2006, 19-25). The founder of the new port of Malacca converted to Islam around 1414, creating a Muslim entrepôt centre that catalysed the spread of Islam along the north coast of Java (Pringle 2010, 26). According to one tradition, a Javanese merchant may have converted the Kolano of Ternate, Kaitjil Gapi Baguna, to Islam during his reign from 1465 to 1486 (Pires 1944, 213; Jacobs 1971, 83; First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1993, 727). His son, Sultan Zain al-Abidin (1486-1495?), was certainly a Muslim. The Kolano of Tidore seems to have been converted by an Arab cleric at about the same time (Gonda 1975, 70). Tomé Pires, who wrote his Suma Oriental in 1512-1515, noted that Muslims were already established on Banda, Haruku, Makian, Motir and Bacan.

The Islamisation of the ruling nobility of Ternate and Tidore led to the promulgation of Islam throughout the many islands that were under their control or influence. However at that time this did not extend as far south as Pantar and Alor, one thousand kilometres distant. Although Nurdin Gogo, the current custodian of the barkcloth Quran held at Alor Besar, claims that it and therefore Islam was brought to Alor in 1518 or 1519, this cannot possibly be correct.

Return to Top

Colonial History

In April 1511 Afonso de Albuquerque set sail from Cochin with 19 vessels to conquer Malacca, which controlled the strategic maritime trade route leading to the Spice Islands. By August the Portuguese had forced the Sultan to flee, establishing their first foothold in the Malay Archipelago.

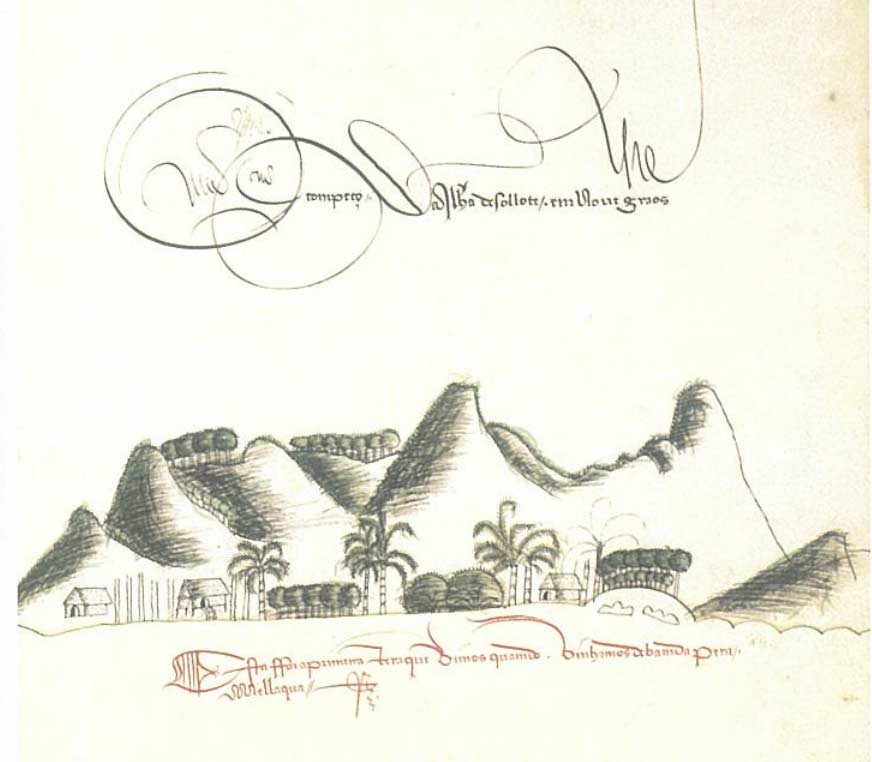

In November 1511, Albuquerque ordered three small ships to sail east from Malacca in an attempt to locate the Spice Islands. Manned by 120 sailors and 60 slaves, they were commanded by Captain-Major Antonio de Abreu, Francisco Serrão and Simão Afonso Bisagudo (Cortesao 1975, ixxx). According to Barros e Galvão, they sailed down the coastline of Sumatra before heading east along the northern coasts of Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Adonara, Pantar (Galao), Alor (Malua), and Wetar from where they headed north to Buru, Ambon and Ceram before finally reaching the Bandas (Cortesão 1975, 286-289). They returned by a similar route. During the voyage Bisagudo’s pilot, Francisco Rodrigues, sketched a village on the north coast of o Galao or Pantar Island, the very first illustration of the island.

Village with traditional houses on Pantar

Francisco Rodrigues, Livro, fl. 54.

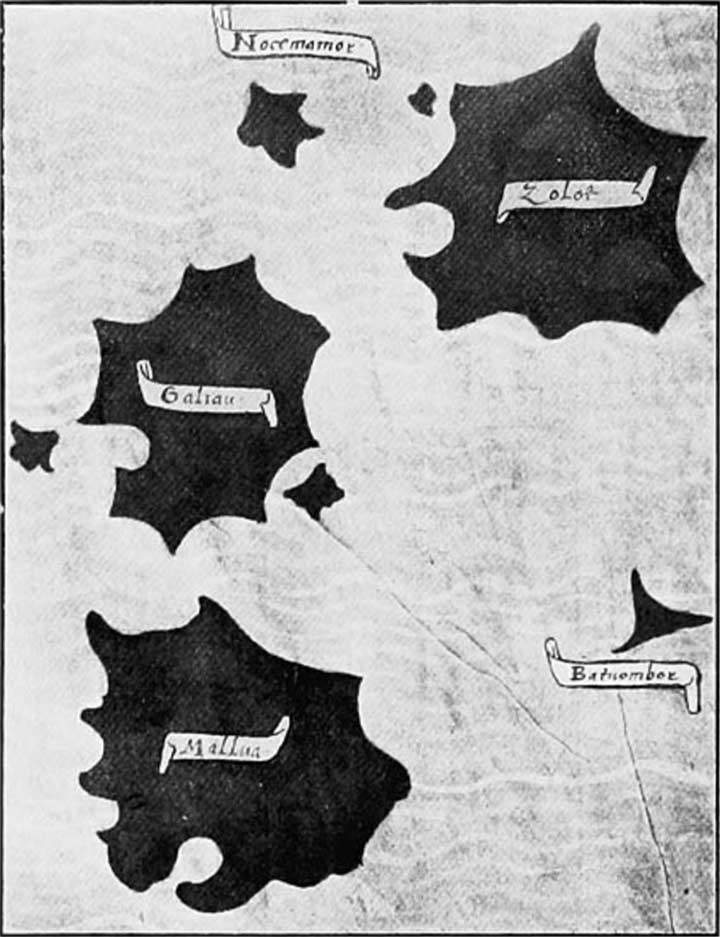

Just a decade later, during the first circumnavigation of the globe, Magellan’s ship the Victoria, captained by Juan Sebastián de Elcano, sailed south from Buru towards the chain of the Lesser Sunda Islands. It is probable that he passed through the Alor Strait between Pantar and Lembata since his navigator charted both Batang and Rusa Islands (labelled Batuombor and Nocemamor). South of Pantar his ship was struck by a fierce storm, forcing him to land on the ‘lofty’ island of Alor (labelled Malua), which he reached on either 8 or 10 January 1522 (Pigafetta 2007, 114 and note 569). We do not know where on Alor the Victoria found shelter. Antonio Pigafetta, the expedition’s journalist sketched an extremely crude map of the islands:

Pigafetta’s 1522 map of Zolot (Solot or Lembata), Galiau (Pantar), Mallua (Alor), Nocemamor (Rusa) and Batuombor (Batang).

He applied the appellation Galiau, later modified to Galiyao, to Pantar Island, probably a distortion of the local name Gale Awa Kukka, meaning ‘living form island’ (Horton 2011, 154). In the very same year of 1522 the Portuguese began building a fortified settlement on the spice island of Ternate in northern Maluku. However local resistance forced them to abandon building a fort on Banda Neira in 1529.

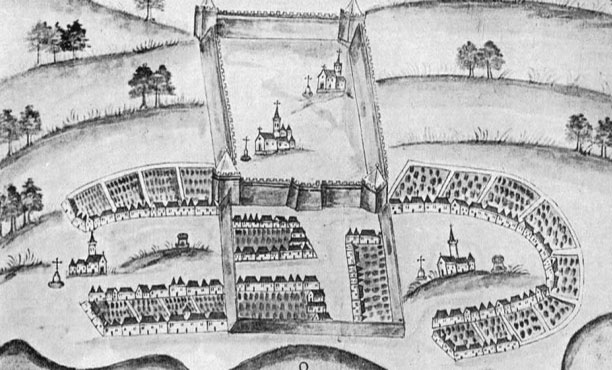

In 1562 Catholic missionaries from the Dominican Order erected a fort made from lontar palm wood at Lohayong on Solor Island, a convenient staging post on the maritime route to Timor. After being quickly burnt down by Javanese Muslims, it was replaced in 1566 by a stone fort with five bastions defended by cannon (Barnes 1987, 209-210). Over time a mixed race community of so-called Black Portuguese grew up around Forte de Nossa Senhora da Piedade, increasingly gaining control over the profitable trade in sandalwood, beeswax and slaves from Timor Island. They became known as Topasses, intermarrying with the Timorese ruling families and establishing their own powerful domains.

The Portuguese Forte de Nossa Senhora da Piedade at Loyahong on Solor Island founded in 1566

The Portuguese Topasses based at Forte de Nossa Senhora da Piedade on Solor obtained their supplies from a variety of ports including Ende, Sikka and Pantar or Galiou (Tiele 1886, 89; Dietrich 1984, 319). Although Pantar fell within the Portuguese sphere of influence it did not have a great deal to offer apart from volcanic sulphur. Nevertheless the Portuguese appear to have made treaties with some local rulers, although their influence seems to have been limited to specific coastal regions of Pantar and western Alor (Klamer 2010, 14). Portuguese and other merchants sailing from Makassar and the Banda Islands in the north to Timor Island and Sumba Island in the south, often passed through the Alor Strait between Lembata and Pantar and would have found the west coast settlement of Baranusa a convenient port of call (Klamer 2010, 7). Its precise location at this time is unclear - the original centre of the domain was Waiwagang, well to the north of Blangmarang Bay (Bell 2009, 50-51). We do not know when its occupants began migrating south.

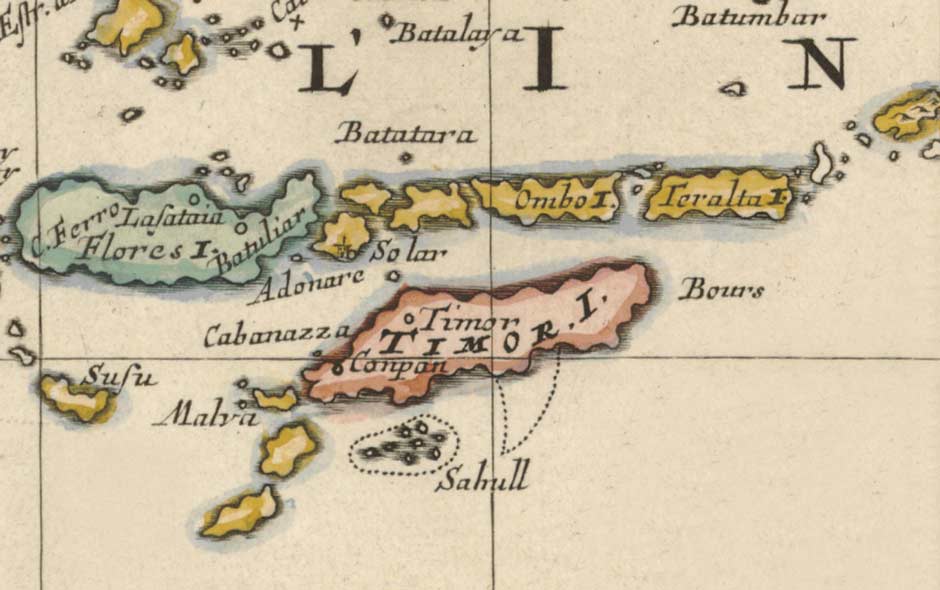

Despite the observation of Pigafetta, and the fact that Makassarese and Topass navigators must have known these islands well, many of the old colonial maps depict Pantar and Alor as a single island.

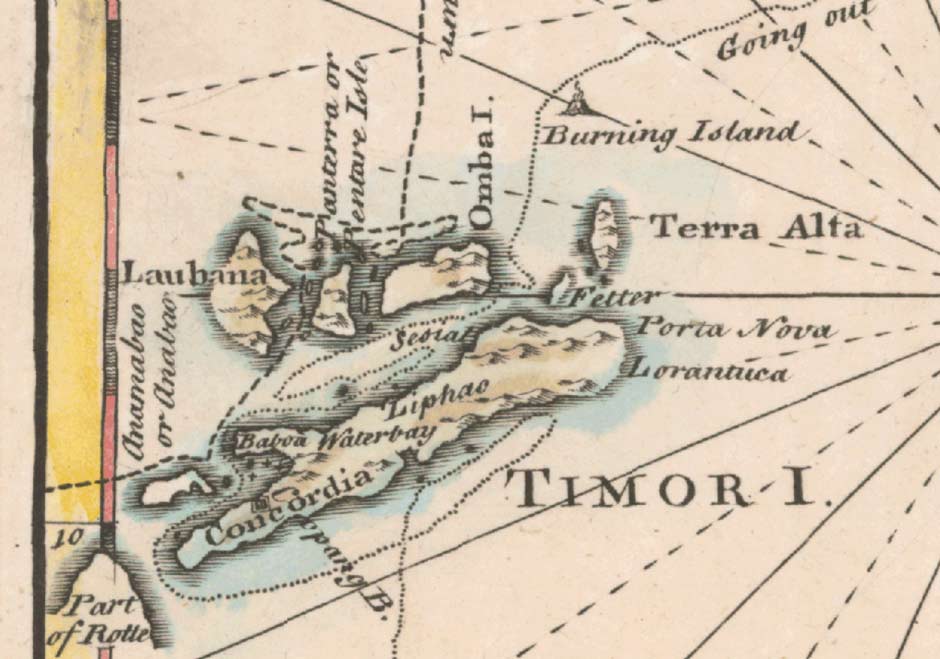

Pantar and Alor are depicted as the single island of Ombo. Teralta is tiny Romang

(De Molukkische Eilanden, Nicolas Sanson, Utrecht 1683)

The enclaves of Baranusa, Pandai, and Blagar on Pantar, along with Alor Besar and Kui on the west and southwest coasts of Alor, eventually formed an alliance of brotherhood named Galiyao Watan Lema – the five shores of Galiyao, with Pandai at its head (Barnes 2001, . A similar alliance – the Solor Watan Lema – was formed at some time prior to 1590 in the nearby Solor Archipelago, encompassing Lohayong and Lamakéra on Solor, Lamahala and Terong on Adonara, and Labala on Lembata (Dietrich 1983, 54, cited by Barnes 2001). The formation of both of these alliances may have been driven by a desire to rationalise or abolish the bridewealth demands required for intermarriage between these neighbouring communities (Gomang 1993, 39, 88-89; Rodemeier 1995, 439). Sometime later, we do not know exactly when, the two alliances formed a coalition known as the Sepulu Pandai or Ten Shores (Gomang 1993, 88-89; Hägerdal 2012, 38). It was apparently sealed by a vow of brotherhood (bela baja or big oath) and the drinking of blood mixed in arak. Henceforth any conflict between the two alliances would end in calamity (Barnes 2001, 278-279). Gomang suggests the motivation was to form an axis of coastal Muslims (known locally as the Paji) to wage war against the Demon, local inland or ‘mountain’ people and the Portuguese Catholics (Gomang 2006, 485).

In 1570 Sultan Khairun of Ternate was assassinated on the orders of the local Portuguese captain (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 19; Subrahmanyam 2012, 144). His son, Sultan Babullah, responded by eventually driving the Portuguese from the island, enhancing his status in the process. One of the consequences of this was an increased effort to spread Islam more widely throughout Maluku and beyond, extending as far as some of the coastal kingdoms of Sulawesi. It is probable that the missionaries sent to the coastal settlements of Galiyao Watan Lema arrived at this later stage, as opposed to a century earlier. Local legends suggest the conversion took place 14-17 generations ago, roughly between 1585 and 1660 (Rodemeier 2010, 28).

The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies, 19 July 1599

Andries van Eertvelt

When the Dutch entered the region in the early 1600s, the Galiyao Watan Lema was still nominally allied to Portugal. After its establishment in 1602, the VOC (Dutch East India Company) set out to eliminate the power of Portugal by attacking every Portuguese stronghold, working its way from east to west (de Roever 2005, 219). It began with an attack on Tidore in 1605, demolishing the Portuguese fort (Widjojo , 22). The Dutch returned in 1607 and within a few years had established four forts on Ternate, one on Tidore and another on Halmahera.

The Dutch attack on Tidore in 1605

In 1613 a Dutch fleet led by Appolonius Schotte, assisted by troops from Ternate, laid siege to the Portuguese fort on Solor for three months. Instead of fleeing to Malacca, the defeated Topasses were allowed to join their compatriots at nearby Larantuka, where they eventually became known as Larantuqueiros. They made several attempts to regain the fort on Solor, but the Dutch prevailed. They renamed it Fort Henricus.

After capturing the fort, Schotte reported that both Ende and Galiyao had risen up against the Portuguese and declared themselves subject to the king of Ternate, thus implying an alliance to the Dutch (Tiele 1886, I, 109). Galiyao had indeed switched its loyalties from the Portuguese to the powerful Sultanate of Ternate in Maluku. Despite this the coastal Rajas of Pantar (and Alor) appear to have maintained a loose loyalty to the Portuguese for the following two centuries. At first the Dutch VOC had almost no interaction with Pantar or Alor, and for a while the islands may have been under the influence of the Makassarese who might have demanded a modest tribute (Hägerdal 2010a, 17).

A Portuguese manuscript dated 1624-1625 mentions that Levotolo (Ilé Api) and Queidao (Kedang) on Lembata and Galiyao (Pantar) were inhabited by both pagans and Muslims. Merchants from Pantar would visit Larantuka with beeswax, turtleshell and slaves, the latter probably captured in the mountains (Barnes 1982, 408; Hägerdal 2010, 179; Hägerdal 2012, 101).

In 1630 the Dominican Friar Miguel Rangel arrived in Larantuka from Goa, India, with ten missionaries and nine cannons. He immediately moved to the empty fort on Solor, which the Dutch had evacuated the previous year. Two of the Dominicans who arrived with Rangel were dispatched to establish stations on Alor and Pantar (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 83-84). What happened to them remains a mystery. Rangel’s occupation of the Solor fort annoyed the Dutch who, in 1636, sent a small fleet to dislodge him - unsuccessfully as it transpired. He left the following year but the Dutch did not reoccupy the fort until 1646.

Having been expelled from Solor, the Portuguese Topasses from Larantuka still needed to maintain their important trade in sandalwood from Timor. No longer able to sail due east between Solor and Adonara, they now sailed along the north coast of Adonara before heading south through the Alor or Pantar Straits (Hägerdal 2010b, 224). This kept them in close contact with the communities on Pantar and western Alor, where they exchanged iron, cutlasses and axes for local commodities (Hägerdal 2010a, 17; Klamer 2010, 14). A 1663 VOC report mentioned that Makassarese merchants from Sulawesi imported gongs and moko drums manufactured in Java (Hägerdal 2010b, 244).

In 1657 the VOC relocated their base of operations from Fort Henricus on Solor to Fort Concordia in the Bay of Kupang, much to the displeasure of the Solorese. Nevertheless they maintained good relations with the local ruler of Lamakera on Solor Island who assisted them in their trade with Pantar and Alor (Hägerdal 2012, 237). A VOC report from 1665 describes an unsuccessful three-month expedition by the chief of Lamakera to acquire sappanwood from the forests of Pantar for the VOC. The mountain people proved hostile and the mission was abandoned. In the second half of the 17th century, merchants increasingly visited Pantar and Alor from Kupang, probably because of its increasing population of Chinese (Hägerdal 2012, 244).

In 1677 an unsuccessful VOC expedition led by Johannes van den Broeck from Kupang visited the Raja of Pandai, Sako Mede, in an attempt to acquire beeswax and slaves. It left with a modest amount of wax and just three slave girls (Hägerdal 2012, 244). Some indication of the lack of harmony between members of the Galiyao Watan Lema can be gauged from the fact that, at the time of van den Broeck’s visit, Alor Kecil had been at war with Blagar for five years. Apparently Alor Kecil refused to make peace with Blagar without the mediation of the leading voice of the Solor Watan Lema, the queen of Lahayong on Solor Island.

In 1685 the British bucaneer William Dampier joined Captain Charles Swan aboard his ship the Cygnet as navigating officer. After sailing across the Pacific from Mexico to Guam, the Philippines and Sulawesi, they finally reached Buton Island on 6 December 1687. After leaving Buton on 12 December, eight days later the Cygnet passed westwards along the north coast of the island of Omba, which Dampier described as a 'pretty high island'about 13 or 14 leagues long and 5 or 6 leagues wide - roughly 75km by 31km, not a bad estimate as it is actually 90km by 35km (Dampier 1699, 459). He added:

About 7 or 8 Leagues to the West of Omba, is another pretty large Island, but it had no Name in our Plats; yet by the Situation it should be that, which in some Maps is called Pentare. We saw on it abundance of Smoaks by day, and Fires by night, and a large Town on the North side of it, not far from the Sea; but it was such bad Weather that we did not go ashore. Between Omba and Pentare, and in the mid Channel, there is a small low sandy Island, with great Shoals on either side; but there is a very good Channel close by Pentare, between that and the Shoals about the small Isle.

The small mid-channel sandy islet must have been low lying Buaya Island. Over the next few days they sailed south through the Pantar Strait keeping close to Pantar shore, narrowly escaping being shipwrecked on one of the two small islands at the south end of the channel (possibly Pura or Teraweng) by pushing their ship away from the shoreline using their oars. From here they continued to Australia, passing two small islands at the southwestern end of Timor (Samua and Rote).

Dampier revisited the region in December 1699 as captain of the Royal Navy warship HMS Roebuck, which had been tasked with the first British scientific expedition to Australia. At that time he sailed from Baboa in western Timor through the strait separating Alor and Atauro heading towards the Banda Islands (Dampier 1709, 87). After cicumnavigating New Britain he returned along the north coast of New Guinea and on 14 May 1700 once again reached the north coast of Pantar Island (Dampier 1709, 169).

..... we saw many Houses and Plantations in the Country, and many Coco-nut-Trees growing by the Sea side. We also saw several Boats sailing cross a Bay of Channel at the west end of Misacomby (Alor), between it and Pentare (Pantar).

On this occasion Dampier chose not to sail south through the Pantar Strait, fearing it was too narrow. However lacking sufficient wind he struggled to locate the entrance to the Alor Straight separating Pantar and Lembata. After a day or two he finally reached a spit of sand and two islands at its northeast entrance (the Lapan and Batan Islands) and with a wind from the south-south-west and a good current completed his passage by nightfall before continuing on to Timor.

Detail from a 1744 map of 'Discoveries Made by Captn. William Dampier in the Roebuck in 1699' by Emanuel Bowen. It shows the islands of Lembata (Laubana), Pantar, Alor (Omba), Atauro (Fetter), Wetar and Gunung Api (burning island).

In 1717 a Topass leader with a contingent of 50 soldiers and two priests sailed from Larantuka to Pantar (Coolhaas 1979, 297). They built a settlement and church at Pandai, and began to erect a fortress. News reached the Dutch at Kupang who in 1719 dispatched an official to remind the intruders that this was Company territory and therefore off-limits to the Portuguese. It seems that the Topasses complied with this request and later moved across to Alor (Hägerdal 2015, 17). A 1733 Portuguese report again mentioned that Pantar was only populated by pagans and Moslems (Barnes 1982, 408).

In 1754 the domain of Baranusa was threatened by inter-tribal war from two of the surrounding villages. The chief and his supporters decided to relocate to the nearby island of Kura in Blangmarang Bay.

Topasses or black Portuguese in Batavia

(Ceremonies and Religious Customs of the Various Nations of the World, Amsterdam, 1752)

The white Portuguese were slowly losing their grip on the region in the face of the increasingly powerful Topasses – Portuguese mestizos who had monopolised the trade in sandalwood and slaves from Timor. In 1769 they forced the Portuguese Viceroy José Telles de Menezes to abandon the fortress at Lifau and relocate with 1200 refugees and just 15 surviving troops to the harbour of Dili some 50 kilometres eastwards (De Sousa 2012). This left the Topasses free to control the sea routes between Timor and the eastern islands of Solor, Flores, Alor and Wetar.

Heavily armed Dutch VOC ‘East Indiamen’, 1790

The Dutch VOC was also on the wane and during the second half of the 18th century ceased to have any significant influence beyond Kupang. In 1785 the governor of the Banda Islands complained to Batavia that marauders from Pantar were harassing Wetar Island (Hägerdal 2012, 245). The complaint was forwarded to Kupang, where the VOC said that Alor was beyond its jurisdiction and that it was therefore unable to intervene. Following the dissolution of the VOC in 1799, Alor and Pantar became a diplomatic no-man’s-land – the two colonial powers still laid theoretical claim to the region but neither had the incentive or means to take effective control.

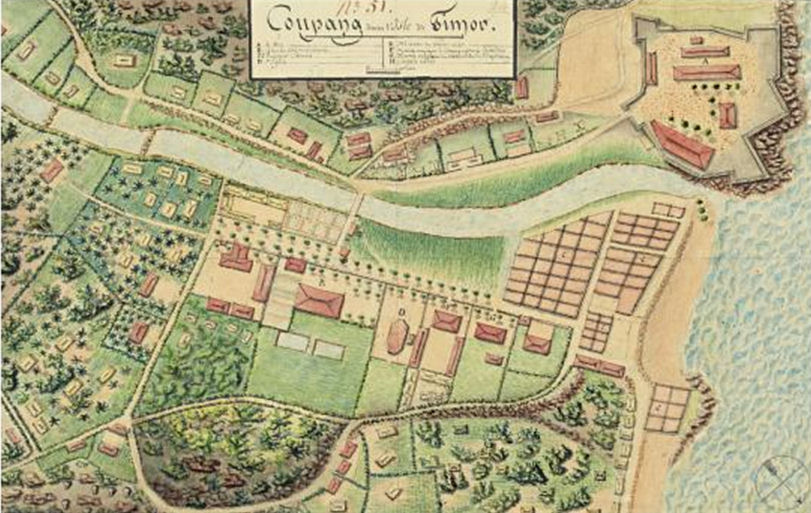

Fort Concordia and the Dutch settlement at Kupang in 1801

(From Salomon Müller)

The Dutch hold over the East Indies loosened further during the French Revolutionary and Napoleon Wars. The British occupied Kupang in 1812 and in 1814 Raja Manhola of Pandai and the Raja of Alor Besar voluntarily requested to be placed back under Portuguese authority (Rodemeier 2006, 78). The Portuguese Governor, Victorino Freire da Cuñha Gusmao, based in Dili, East Timor, endorsed this request and sent flags to confirm the new suzerainty. According to Lynden, the Portuguese also gave the chiefs of Pandai, Baranusa and Alor silver-topped canes (1851, 334). After the fall of Napoleon the British relinquished their control of the East Indies in 1816, and the returning Dutch claimed back the Portuguese gains.

According to a Dutch report, the Sepulu Pandai or Ten Shores composed of the ten domains of Galiyao Watan Lema and Solor Watan Lema finally disintegrated as a result of internal differences in 1820 (Hägerdal 2012, 38 and 245 note 95).

Although the Dutch had long maintained a posthouder (post-keeper or civil administrator representing the colonial power) at Lohayong on Solor with responsibility for overseeing Alor and Pantar, his ability to do so was slight. In the same year of 1820 the Dutch authorities in Kupang responded to recent Portuguese interests and the severing of the alliance between the coastal domains of Solor and Alor-Pantar by establishing a local presence on Pantar in the form of a posthouder called Evers (Hägerdal 2010a, 18; Hägerdal 2012, 245).

The Dutch presence on Alor turned out to be brief – terminated in 1831 on the orders of the Dutch Commissioner in Batavia, Emanuel Francis. This left some of the Alorese domains susceptible to the influence of the Topasses based at their stronghold of Lifau on Timor. Some insights into the tussle between the Portuguese and the Dutch for influence over Pantar can be gained by the subsequent events that took place in the domain of Pandai-Baranusa.

Portuguese sources record that Manhola, the chief of Pandai, was acknowledged by the Portuguese in around 1814 (Rodemeier 2006, 78). He was succeeded by Raja Hukum, who we know was still in power during the year 1832. Following the latter’s death a dispute arose over his succession with one candidate supported by the Portuguese Topasses and the other by the Dutch. The records show that Raja Hukum’s son, Salama Boka (or Slamat), travelled to Kupang in 1848, where the Dutch authorities endorsed his position as the legitimate successor (Hägerdal 2010, 29). Back on Pantar he was challenged by his uncle Boka or Bokka, who had the support of the Portuguese as well as his son Pela Boka and the Raja of Lamakera on Solor Island. The Dutch finally intervened in 1853, sending an armed expedition to Pandai to arrest Bokka and bring him to Kupang. Raja Slamat apparently ruled intermittently until 1877 and was succeeded by his son, Raja Beng Hukung, who ruled from 1878 until 1901.

Conflict between the coastal Rajadoms and the interior mountain people was common, with the latter frequently mounting attacks on the coastal domains. As a result of an attack in 1846, the Rajas of Blagar and Baranusa sought military assistance from Timor. In 1855 the mountain people destroyed the village of Baranusa and forced the Raja to flee to Alor (Hägerdal 2010, 19). The situation on Pantar, as well as on Alor, Lembata and the Solor Islands, eventually improved after the Rajas of the coastal villages were forbidden to summon auxiliary troops from Timor to assist in their subjection of the mountain populations (Koloniaal Verslag 1880, 14, cited by Barnes 2001, 296).

The Dutch bombardment of Larantuka in 1839 led to the opening of a dialogue between the Dutch authorities in Kupang and the Portuguese authorities in Dili concerning the disputed colonial sovereignty of Timor, East Flores and the Solor Islands. When José Lopes de Lima arrived as the new Governor of cash-strapped Dili in 1848 he set out to not only resolve the conflict over frontiers, but also to put the finances of his administration in order at the same time. He finalised an agreement with the Dutch Resident in Kupang, Baron van Lynden, in November 1851 to cede Flores, Solor, Adonara, Lembata, Pantar and Alor to the Dutch in return for the enclave of Oecussi and Maubara and Atauru Island in East Timor. Because the islands ceded to Holland were larger than the territories ceded to Portugal, the Dutch would make a payment of 200,000 florins (de Sousa Saidanha 1994, 38-39). Desperate for cash, Lopes de Lima immediately rescinded authority over Flores and the other Solor Islands in return for 80,000 florins. When Lisbon received news about the agreement they were furious and Lopes de Lima was recalled as a traitor but died at sea. However his agreement could not be annulled and a formal treaty of demarcation was finalised in 1854 but only ratified in 1859 as the Treaty of Lisbon. Further minor conventions followed in 1893, 1904 and 1913, the 1904 agreement formalising the boundary between Dutch West Timor and Portuguese East Timor.

Baron van Lynden noted that the population of Alor and Pantar was divided into the 'beach people', predominantly the Muslims of Pandai, Blagar, 'Bamoesang', Alor and Kui, and the 'mountain people' who were pagans (1851, 332). In his opinion the former were conquerers from Ternate. The mountain dwellers were 'less civilized, quarrelsome and untrustworthy'. Their dress consisted of a loincloth of tree bark or cotton, the latter bought from the beach people. In the past Alor and Pantar supplied many slaves, some to the Timorese at Oecusse.

The Dutch quickly established a presence on Alor, installing the posthouder Johan Hendrik van Nimwegen at Alor Kecil at the mouth of Kalabahi Bay in 1852 (Almanak van Nederlandsch-Indië 1852). One year after the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Dutch established a small military post on Alor headed by a Lieutenant Pelt, aimed at controlling the slave trade (Dalen 1928, 159). Yet the Portuguese flags owned by some of the coastal Rajas – a symbol of their loyalty to Portugal – were never collected by the Dutch or replaced with the tricolour (Hägerdal 2010, 19).

The Archipelago was divided into seven landschappen, headed by local coastal Rajas who were normally supported by kapitans. On Pantar there were three landschappen – Pandai, Baranusa and Belagar. Each Raja was obliged to sign the so-called Timor Declaration, an acknowledgement of Dutch supremacy and obedience to Dutch commands and a more detailed contract of the old kind in return for a measure of native self-government. Despite this Dutch interference remained minimal, leaving large regions of the island in a state of anarchy.

We know that the Raja of Baranusa, Koliamang Baso, and the Raja of Blagar, Salama Noke, signed the Timor Declaration on 3 June 1896. Both were approved and endorsed by the Dutch East Indies government on 17 November 1896. Both Rajas signed another contract conceding mining rights on 22 July 1898 and a declaration about the imposition of taxes on 22 August 1901. The Raja of Pandai, Beng Hukung, signed the Timor Declaration on 22 August 1901.

Until 1900 the official Dutch colonial policy towards the 'Outer Islands' had been one of non-interference, although this could be suspended if circumstances demanded it (Dietrich 1983, 39). These islands were considered incapable of generating a profit for the colonial treasury and therefore it was deemed that they should be ruled at minimum cost. It was sufficient for the local rulers to acknowledge Dutch supremacy.

The Raja of Blagar, Salama Noke, with his family and two bronze heirloom moko drums (known as kuang on Pantar) around 1900

Since 1871 the Dutch had waged a number of violent military campaigns to gain control of the Sultanate of Aceh on far away Sumatra. Between 1898 and 1903, Colonel Joannes van Heutsz headed a highly successful counter-insurgency campaign using light and flexible detachments of military police (marechaussee), recruited from Ambon and Java. In 1904, following Aceh’s ‘pacification’, van Heutsz was appointed Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies. Faced with numerous on-going local insurrections across the Outer Islands, van Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule.

The first official to implement this new and more active policy in the Lesser Sunda Islands was F. A. Heckler, who took over as Resident of Kupang in April 1902. He faced a problem in East Flores, where the troublesome Catholic Raja of Larantuka, Don Lorenzo II, had become engaged in territorial disputes with the Catholic Raja of Sikka and the Muslim Raja of Adonara (Steenbrink 2002a, 95). In July 1904 Heckler finally took action to depose Don Lorenzo, who was arrested and sent into exile in Yogyakarta. That same summer the Dutch intervened militarily to quash an insurrection in the Sikka area of Flores (Lewis 2014, 371-375).

The next Resident, J. F. A. de Rooy, who took over from Heckler in March 1905, was given clear instructions regarding this much more active policy. His main task was:

To establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the implication of a new strategy towards the self-ruling districts, which are the majority of the whole area. The former policy of non-intervention, suggesting that the supreme authority was with the native rulers and not with the colonial authority, should be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70).

Later that year action was initiated to subjugate the many local Timorese chiefs.

A Muslim community on Pantar in 1905

In 1906 A. J. L. Couvreur was installed at Ende as the first Controleur of Flores Island. His first objective was to explore the unknown territories of Flores and to bring them to heel. Between July 1907 and February 1908, Captain Christoffel and his contingent of armed military police carried out a brutal 'war of pacification' throughout the entire Western and Central areas of Flores, first taming Ende before sailing to Aimere Bay to gain control of Ngada and Manggarai. Villagers were disarmed and a census was conducted which would later be used to impose taxes in the form of money and unpaid labour. Prior to then, taxes and fines on the native rajas had been payable in the form of commodities such as coffee, rice, corn or elephant tusks (Steenbrink 2002b, 70). The proceeds were invested in roads for the army (built using forced labour), harbours, and schools.

Dutch East Indies marechaussee troops in 1900

(A painting by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht)

Also in 1906 A. F. Morgenstern was appointed as the new posthouder at Alor Kecil (Regeeringsalmanak voor Nederlandsch-Indie 1907). It did not take him long to realise that although the Dutch-appointed coastal Rajas took it upon themselves to exert their authority over their respective hinterlands, the animist mountain people did not accept them as their leaders (Morgenstern 1909). They spoke a different language, had a different religion and did not understand their adat. A decision was made in the same year to construct the capital town of Kalabahi at the head of Kalabahi Bay (Rodemeier 2006, 81).

The Raja of Baranusa, Koliamang Baso, persuaded his tribes to relocate back from Kura Island to the mainland in 1908, where they resettled along the western shoreline of Blangmerang Bay. That same year a German priest arrived on a Dutch vessel at Dulolong in Kalabahi Bay and began conducting baptisms (Abdurachman Nampira 2017).

The Dutch did not focus their attention onto Alor until 1910, where the posthouder A. F. Morgenstern had just been replaced by Meulemans at Alor Kecil. In July, Lieutenant Adelberg was sent from Kupang to Kalabahi with three detachments of marechaussee. It seems the mountain dwellers on Alor respected the well-armed troops and were generally cooperative (van Galen 2010, 22). The population of Alor Island was registered, their muskets and other weapons were destroyed and the Rajas were pressurised to sign the Korte Verklaring or ‘Short Declaration’ – a one-sided agreement designed by van Heutsz in which they recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies. The census enabled the Dutch to levy taxes in the form of heerendiensten or unpaid labour (Dietrich 1985, 279). Men were brought in from the mountain villages to construct roads in and around the capital of Kalabahi. Some of these were described by Nieuwenkamp in 1918 (1922, 71 and 73). Inevitably, Dutch taxation and forced labour soon led to local hostilities.

In 1911 Adelberg and his men returned to Kupang, leaving the Dutch administrators defended by a small detachment of prajurits or armed policemen. However it soon became apparent that the prajurits at Kalabahi needed to be reinforced. During that year the main seaport was moved from Alor Kecil to Kalabahi. One year later Meulemans was sufficiently entrenched to engineer a transfer of the Rajadom of Alor from the dynasty of Tulimau in Alor Besar to the dynasty of Nampira at Dulolong. Raja Kwiha Tuli II became ill and delegated his kapitan, Nampira Bukang, to act on his behalf. Meulemans refused to accept this compromise and raised Nampira Bukang as the new Raja (Gomang 1993, 81). The latter was preferred because he was educated and fluent in Dutch, wealthy and influential. As consolation the former Raja was appointed kapitan. Nevertheless the Tulimau family did not accept this lightly and in 1916 incited a revolt on Kabola while making several attempts to burn down the house of Raja Nampira Bukang at Dulolong.

Raja of Alor Landschapp, Nampira Bukang

During Meulemans tenure at Alor Kecil, Protestant missionaries linked to the Indische Kirk (the Dutch Reformed Church in the East Indies) were brought to Alor Island to spread the Gospel and to encourage converts to be baptised. In the early 1910s religious teachers were brought in from Rote (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 306). The first church on Alor was built in Kalabahi in 1912 - using a Muslim workforce!

The Dutch pacification of Pantar Island was conducted in parallel with that of Alor (Rodemeier 2006, 81). The population was registered and the resulting census became the basis for payment of tax, mostly in the form of unpaid work (Dietrich 1985, 279). When the Raja of Pandai, Sinung Maleng, became ill in 1911 he was succeeded by his kapitan, Koliamang Wono (van Galen 2010, 29).

Dutch troops were sent to Pantar in 1913 to supress a rebellion of mountain people at Blangmerang. The villagers were armed with shotguns acquired from the Solor Islands, in particular Adonara (van Galen 2010, 22). More trouble broke out in May 1916 and this too was quickly suppressed. Resistance inevitably arose when ambitious kapitans attempted to register the mountain villagers or impose taxation or forced labour (Stockhof 1984, 111-112).

In 1915 back in Dulolong, the Raja of Alor, Nampira Bukang, was succeeded by his son, Marzuki Bala Nampira.

In June 1918 the Dutch artist Wijnand Nieuwenkamp made a very brief visit to Pantar in the company of Lieutenant W. Muller, the military commander of Alor. From Kalabahi they sailed around the north cape of Pantar, making a brief stop at the small settlement of Kabir before anchoring in the safe haven of Blangmerang Bay. In the distance a column of smoke rose from the volcano. Baranusa was described as a poor dilapidated Islamic village located just above sea level, with a beach, a few perahus and the dirty, ramshackle home of the Raja, Koliamang Baso, the proud owner of a circular bolean mas gold plate and 50 moko drums. Nieuwenkamp returned to Kalabahi to spend seven days with Muller, where he observed hundreds of Alorese conscripted from mountain villages, organised into working parties for the construction of new roads around the town.

Moko drums sketched by Nieuwenkamp on Alor in 1918

A few months later, the Raja of Alor, Bala Nampira, was murdered by mountain villagers at Fungwati, incited by registration, the capture of unregistered people and demands for corveé service and taxation (van Galen 2010, 24). Lieutenant W. Muller set out to supress the uprising, but resistance was not finally overcome until October. The Raja’s assassination caused consternation among the Muslim members of Galiyao Watang Lema, including Pandai, Baranusa, and Bakalang on Pantar, who regarded it as an attack on one of their allies (Rodemeier 2006, xx).

In the 1850s Pantar had initially been divided into three zelfbesturende landschappen – Baranusa, Blagar and Pandai, while Alor was divided into four, then later divided into six – Alor, Kui, Bataru, Pureman, Batulolong and Kolana (Van Galen 2010, 20). In 1918 the Dutch rationalised the administration of Pantar by merging the landschappen of Pandai and Blagar into Pantar Matahari Naik, matahari naik meaning ‘sun rising’, in other words referring to the eastern part of the island. Koliamang Wono was appointed the acting Raja of Pantar Matahari Naik and signed the Short Declaration in November 1918.

In the 1920s the Nederlands Zendingsgenootschap (NZG) ‘Dutch Missionary Society’ opened schools on Pantar. In the Dutch schools the language of education was Malay, as elsewhere in the Dutch East Indies. On Pantar taxes were paid by labour, and many ‘roads’ were built. The labourers were supervised by kneko (servants) recruited from other regions (Rodemeier 2006, 80). Also during the 1920s and 30s the Dutch waged a campaign to destroy the huge number of moko drums that were circulating on the islands and acting like an unofficial currency.

Koliamang Wono, the Raja of Pantar Matahari Naik, chose to retire in 1926 and was granted a pension. It provided the Resident of Timor with an opportunity to further rationalise the governance of Pantar, transferring responsibility for the landschappen of both Pantar Matahari Naik and Baranusa to Umar Watang Nampira, the caretaker Raja of Alor landschap (the western coastal region of Alor Island). The latter was appointed official Raja the following year.

The Raja of Alor Landschapp, Umar Watang Nampira

In 1928 M. A. Bouman was appointed Inspector of Alor and Pantar and was quickly promoted to Assistant Resident. In May of the following year he travelled with Ernst Vatter and Umar Watang Nampira, the Raja of Alor, on a ten-day expedition to Pantar using the Dutch motorboat. Vatter was of the opinion that now that the whole of Pantar was subordinated to the Raja of Alor, the endless disputes between the three domains on Pantar had come to an end (1932, 260). The former Rajadoms of Baranusa, Pandai and Blagar were now only districts, headed by local kapitans. The name of the largest former Rajadom, Baranusa, was used by the surrounding islands as a designation for the whole island of Pantar.

They landed on the east coast at Bakalang after seeing local fisherman using small yellow tawa fish kites made of pandanus leaf. From there they travelled south along the coast to the Di'ang-speaking village of Lebang with its thirty houses.

A traditional house in Lebang, photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Continuing southwards Vatter passed through Sargang and Lälangabang before reaching Muriabang in the heart of the Döing-speaking area. The houses here were different, the older ones having steep-sided roofs. Grain stores were built high in the canopies of trees and there were also small houses used by the local women to give birth (1932, 266).

Villagers in Muriabang, Pantar, photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Travelling south of Muriabang they traversed the wide plain at the north foot of Kukka Sirung, covered with grassland, thick undergrowth, bamboos and extensive coconut and Lontar palm forests. After visiting Alalao and Mäuta they headed west to Tubal. For a brief review of their ethnographic observations, see Ethnography.

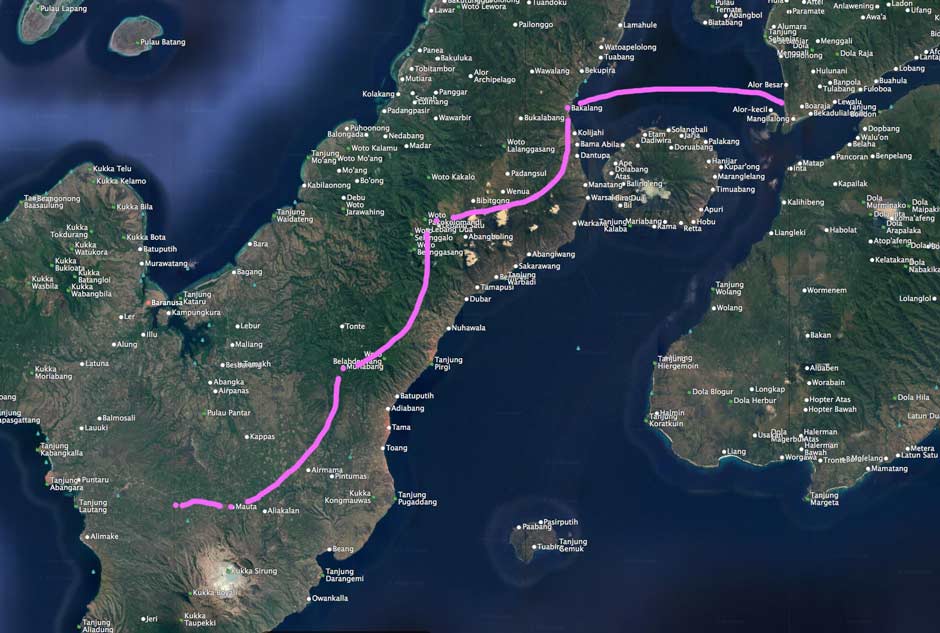

Vatter’s travels on Pantar

After sailing from Alor Kecil to Bakalang he continued south westward to Tubal

On Alor in the early 1930s, Assistant Resident M. A. Bouman was working alongside Controleur J. Wetstein and the military attaché Lieutenant D. Frijlink (Brouwer 1935). Controleur Wetstein was at some time replaced by K. Reijnders, who in turn was replaced in 1938 by G. A. M. van Galen.

In January 1938 the New York anthropologist Cora du Bois arrived in Kalabahi and soon moved to the small Abui mountain village of Atimelang. During her stay on Alor she never visited Pantar. At that time the onderafdeeling of Alor was divided into four Rajadoms – Alor including Pantar along with Pura, Ternate, Buaya and Tereweng, Kui, Batulolong and Kolana (Du Bois 1944, 16).

During the 1930s Dutch missionaries from the Indische Kerk (the Dutch Reformed Church in the East Indies) established the first schools and churches on Pantar. Between 1941-42 the missionary C. W. Mollema was active on the Alor islands (Rodemeier 2006, p. 83). However Dutch colonial interests remained primarily confined to the new administrative centre and port of Kalabahi on Alor. They had little interest in Pantar (Rodemeier 2006, 81).

In 1939, Anwar, the son of Koliamang Wono, was appointed kapitan of Pantar Matahari Naik.

The Dutch East Indies government in Batavia was well aware of the threat from Japan. The Japanese had already pressurised them to agree to supply oil. By the start of 1941 three brigades of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger or KNIL) were stationed at Kalabahi. However in March 1942 a mutiny broke out among the garrisoned soldiers and, after the KNIL officers and under-officers fled, the Dutch administrators and some clerics were taken prisoner. It seems that the officers hurriedly left the island.

The mutiny precipitated an uprising among the mountain villages and a refusal to pay taxes that spread from one kapitan-ship to another. Some hotheads attempted to march on Kalabahi and set fire to the buildings, but were violently repelled by residents from Kalabahi and Alor Kecil. This caused panic in Kalabahi and led to an exodus from the town.

In June 1942 the first Japanese warship arrived at Kalabahi and unloaded firearms and munitions. By July 1942 the Japanese had established their garrison in the town and faced no serious resistance (Du Bois 1961, xiv). They soon came under attack from Allied bombers stationed in Australia. One mission in late 1942 started fires among wharf installations at their new naval base at Kalabahi (A Week of the War 1942, 3).

The occupiers moved decisively against the rebellious kampongs, sending out missives demanding that the rebel leaders appear before them in Kalabahi. When they refused to respond, a troop of 60 marines led by Nakamura violently attacked some of the kampongs. Some village leaders were shot or bayoneted, others were decapitated and some imprisoned (Weaver 1973, 32). Several kampongs were incinerated. Fearing for their lives, some villagers reported to Kalabahi and begged forgiveness. To keep events in perspective, van Galen estimated the total number of dead would not have exceeded fifty. Only one Japanese soldier was killed. Order was only finally restored in October 1943.

Under the Japanese infamous system of conscript romushas or labourers, many people from Alor and Pantar were forced to toil on roads and military installations, both locally and on Timor, working under harsh conditions. Marion Klamer found that most elderly people tell stories about the cruel and barbarous treatment of local people by members of the Japanese army, as well as a lack of food and clothes during their occupation (Klamer 2010, 14). To maintain order and prevent uprisings, small detachments of troops were sent out at irregular intervals to crisscross the islands.

Information is scarce, but it is possible that Pantar was less harshly affected than Alor. Nevertheless van Galen mentions that on Pantar, ten witches (suanggis) were killed on the instructions of a Japanese soldier called Anai (2010, 41).

During March 1945 the Japanese had encouraged Muslim leaders in Batavia to form the Badan Penjelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (Research Body for the Preparation of Independence) and draft a constitution. On 7 August, the day after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the Japanese Commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army, Field Marshall Hisaichi, promised Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta and Dr Radjiman Wediodiningrat that Japan would recognise Indonesian independence. He ordered the creation of the Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence). In remote Kalabahi, the Japanese commander Tomiki received instructions to create a local independence committee. Prominent Muslims in Kalabahi and Dulolong formed Siap (Serekat Islam Alor en Pantar).

After the Japanese Emperor capitulated on 15 August, his representatives formally surrendered on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September. Japanese forces left Alor later that month. On 3 November an Australian corvette arrived at Kalabahi carrying the former Controleur G. A. M. van Galen and a detachment of Netherlands East Indies troops. The onderafdeeling of Alor was back under Dutch East Indies rule.

During the war the coastal Muslim leaders had collaborated with the Japanese and afterwards there seems to have been a settling of scores. Anwar, the kapitan of Pantar Matahari Naik was deposed at the end of 1945 due to complaints of the people over his behaviour. His role was given to a son of the Raja of Blagar, Tahir Noke, who held the post until 1962. Likewise, the Raja of Blagar and his kapitan were deposed in 1945 and 1946 respectively due to ‘committed oppression’ (van Galen 2010, 30). The Muslim independence committee Siap was closed down and all political activity was suppressed.

Return to Top

Modern History

The British and Dutch forces who arrived to re-establish Dutch control encountered a very different situation to that pertaining in 1942. Much of Java and Sumatra was now under Republican control and although the Netherlands had been able to regain many of the Outer Islands, by the summer of 1947 it still occupied just a few enclaves on Java and Sumatra (Homan 1990, 124). Under pressure from the British, the Dutch negotiated the Linggadjati Agreement, which was signed in March 1947. It proposed the creation a new federal structure to decentralise power, with a United States of Indonesia to be formed on 1 January 1949. The Republicans would control Java and Sumatra, leaving the Dutch to maintain control of Eastern Indonesia. The Dutch had already formed the new state of Eastern Indonesia, Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT), on Christmas Eve 1946. It encompassed Bali, Sulawesi and all of the islands further east, including Alor and Pantar, and was to be governed from Makassar (Ricklefs 2008, 276).

The Dutch state of Negara Indonesia Timur, formed in 1946 and dissolved in 1950

(Wikimedia Commons)

The heated negotiations soon broke down, and in July 1947 the Netherlands decided to seek a military solution by launching the so-called First Police Action. This precipitated UN intervention and the Dutch were pressurised to sign the vaguely worded Renville Agreement in January 1948, which reinstated the concept of a United States of Indonesia. There followed a period of intense US diplomatic involvement but this failed to resolve the impasse between the two sides. In the face of increasing guerrilla attacks The Hague launched Operation Crow on 19 December 1948 (Homan 1990, 136). Within weeks Dutch forces had occupied all of the Republican-held cities on Java and Sumatra.

This Second Police Action turned out to be a diplomatic disaster for the Dutch. A UN Security Council resolution in January 1949 demanded the reinstatement of the Republican government. More importantly the USA, aware of increasing communist influence in the region, immediately cancelled Marshall Aid for the Netherlands.

A Dutch-Indonesian round table conference was finally held in The Hague from 23 August 1949 to 2 November 1949, between the Republic, the Netherlands, and the Dutch-created federal states. The Netherlands agreed to recognise Indonesian sovereignty over a new federal United States of Indonesia. It would include all of the territory of the former Dutch East Indies, with the exception of Netherlands New Guinea. The Netherlands finally transferred sovereignty to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia Serikat) on 27 December 1949. This only lasted until 15 August 1950 when the Republic of Indonesia was declared.

These events had little impact on remote Pantar. In Kalabahi the Dutch administration was swiftly replaced by Republican representatives. The first few heads of local government (kepala pemerintahan setempat) were Ludgerus Poluan (1949-50), Hendrik Rihi Kanadjara (1950-1951), J. M. Tawa (1951-1954) and Immanuel Litamahuputi (1954-1958).

With the creation of Nusa Tenggara Timur province in 1958, Alor became a formally designated district or Kabupaten with Sharif Abdullah appointed as its acting head. Alor Regency included Pantar Island, which was divided into two sub-districts: Kecamatan Pantar (formerly Pantar Matahari Naik) and Perwakilan Kecamatan Pantar (formerly Baranusa). Once again Pantar was left with no island head to represent its interests. In any event there was little money available for development in these early days, and although some infrastructure investment took place during the 1960s under regents John Bastian Denu (1960-1962) and Marthinus Umbu Dikky Tarapanjang (1963-1967), this was mainly confined to Kalabahi. For decades to come, up to the present day, only a small fraction of local government money would ever reach Pantar.

After General Suharto seized power from President Sukarno in October 1965, the Indonesian army embarked on a violent and well-planned anti-communist pogrom against the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), which continued into 1967. Many villagers on Pantar had PKI leanings and were subsequently rounded up and taken to Kupang by the army where they were illicitly killed. After Suharto’s coup, anyone not following a major religion was in fear of their life and many converted to Protestantism and Catholicism en masse (Klamer 2017, 13). In time this led to the construction of churches and mosques across the island. Over the past half-century, more resources have been invested in religious buildings than economic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, ports or harbours.

Under Suharto’s New Order national government policy was to encourage indigenous populations to live in more accessible locations where they could be better controlled – either closer to the coast or closer to a main road (Klamer 2010, 6). During the 1960s, mountain villages were relocated, sometimes forcibly, onto the coast. In certain cases, especially around Baranusa, this created tensions, the resettled inland people being regarded as intruders. Some of these disputes have taken on a religious dimension as inland Christians have clashed with coastal Muslims (Rodemeier 2010, 38). Generally however, relations between different religious communities remain good.

In the early 1970s the first motorised perahus reached Pantar Island and a regular weekly ferry service was begun between Kabir and Kalabahi (Klamer 2010, 6).

The port and mosque of Baranusa

(Photographed by Professor Robert Barnes in 1996, Shared Shelf Commons)

The collapse of the Suharto regime in May 1998 left a hiatus in the outer islands. In 2005 a telephone landline was established with Kabir, while in 2007 Telkomsel announced that it had completed the installation of its first cellular telephone towers on Pantar. In that same year Pantar was divided into five sub-districts in an attempt to encourage faster development.

The kecamatan of Pantar from west to northeast: Pantar Barat Laut, Pantar Barat, Pantar Tengah, Pantar Timur and Pantar Timur Laut

In 2011 a ferry port was opened alongside the existing seaport at Baranusa (NTT Province Transportation Department), while central government funding resulted in the construction of Kabir Airport, which is expected to become operational at some time during the next five years

Yet the Alor Regency government's medium-term development plan for 2014-2019 highlights that there is still much to be done. Access to fresh water still remains a major problem in villages in Pantar Tengah, Pantar Barat, and Pantar Barat Laut. There remains no island-wide system of public transportation and five sub-districts on Pantar still have no access to modern communications. Many Pantar villages still lack electricity and have limited access to mass media, although satellite receivers are now found in some villages.

Return to Top

The Chiefs of Pandai, Baranusa and Blagar

Thanks to the 1946 Memorie written by the Controleur of Alor, G. A. M. van Galen, and the research work of Hans Hägerdal, we have a list of the Rajas of the three main domains on Pantar (Van Galen 1946 and Hägerdal 2010, 28-30):

Rulers of Pandai, northern Pantar

Dai Mauwolang (founding ancestor of the dynasty)

Sako Mede (was ruling in 1677)

Manhola or Bapa Boka (was ruling in 1814)

Hukum or Pela Boka (was ruling in 1832)

Salama Boka (was ruling in 1848)

Beng Hukung (1878-1901)

Sinung Maleng (1901-1911)

Koliamang Wono (1911-1926)

Rule transferred in 1926 to Umar Watang Nampira, Raja of Alor landschappen.

Rulers of Baranusa, western Pantar

Bara Mauwolong (founding ancestor of the dynasty)

Mau Bara I

Boli Mau

Mau Boli I

Bara Mau

Mau Bara II

Tonda Boli I

Boli Tonda

Mau Boli II

Tonda Boli II

Boli Tonda (was in power in 1832)

Aku Boli (1848-1877)

Baso Aku (1878-1895)

Koliamang Baso (1896-1926)

Rule transferred in 1926 to Umar Watang Nampira, Raja of Landschappen Alor.

Rulers of Blagar, eastern Pantar

Maka Pala (first half 19th century)

Keibara (was ruling in 1850)

Leing Date (1853-91)

Koli (1852-1895)

Salama Noke (1896-1917)

Noke Salama (1917-1918)

The landschaps of Blagar and Pandai were merged to form Pantar Matahari Naik in 1918. This was ruled by the former Raja of Pandai, Koliamang Wono, until 1926.

Return to Top

Languages

As Frans Watuseke discovered from his informant Alex Waang, a Christian from Kabir in West Pantar, the languages of Pantar and Alor differ widely and its inhabitants do not completely understand each other (1973).

The Assistant Resident M. A. Bourman was the first to identify some of the languages spoken on Pantar (1943, 484). He identified Blagar along the east coast; Lemma, Mauta, Di’ang, Madar and Bitang among the inland population of southern and central Pantar; and Alorese and its Kajang dialect among the Islamic costal populations of western Pantar.

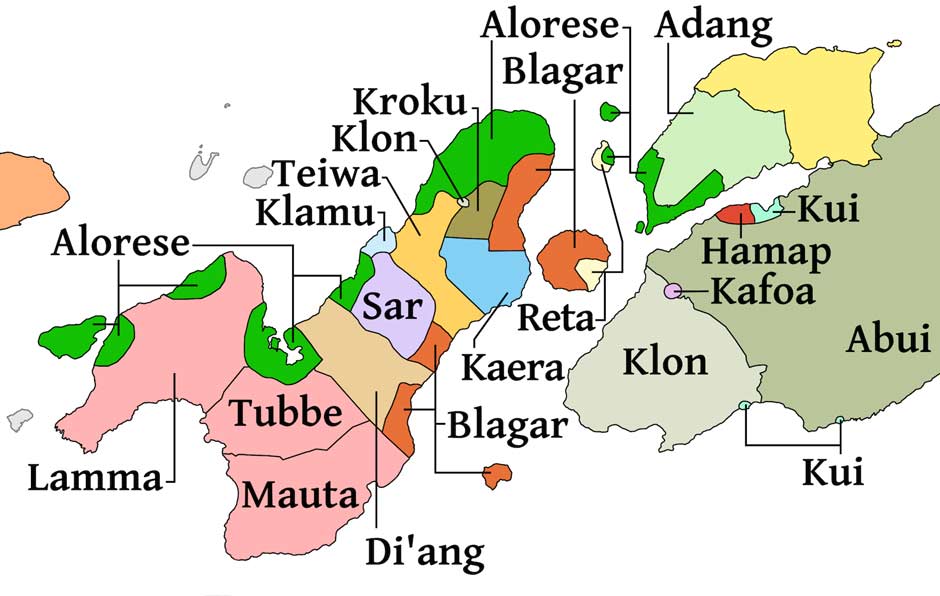

Linguistic map of Pantar Island and Western Alor

(Reproduced courtesy of the cartographer and copyright holder Owen Edwards 2018)

Modern linguists at the Universities of Leiden and Hawai’i now identify ten separate languages on Pantar. Nine of these are classified as Papuan languages belonging to the Timor-Alor-Pantar family. The term Papuan refers to the hundreds of non-Austronesian languages spoken in New Guinea and its vicinity:

- Blagar in enclaves along the east coast,

- Di’ang or Dë'ing in the southern part of eastern Pantar

- Kaera in the east coast region facing Pura Island,

- Klamu or Nedebang in the villages of Balungada and Baulang on the west coast,

- Klon spoken in one village in eastern Pantar,

- Kroku in the central inland part of the northeast,

- Sar in an inland enclave of the eastern peninsula

- Teiwa in a central band of the eastern peninsula,

- Western Pantar is spoken on the western peninsula and has three dialects – Lamma, Tubbe and Mauta.

Linguists still lack sufficient information to determine the origin of the Timor, Alor and Pantar group of Papuan languages (Klamer 2017, 34).

The tenth language spoken on Pantar is Alorese, a language belonging to the Austronesian family, spoken by more than 10,000 people in pockets around Pandai and Muna Seli on the north coast, around Baranusa and Blangmerang Bay, and on Kangge Island. It is closely related to Lamaholot.

Return to Top

Ethnography

Most research to date has focussed on the linguistics of Pantar, rather than its anthropology. Our comments are mainly focussed on the two ethnic groups involved in weaving on Pantar Island: the Alorese and the Blagar.

Alorese

Syarifuddin Gomang has given a detailed description of the clan structure of the Alorese living in Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong (1993, 50-64). This is very similar to that of the Alorese located on the islands of Ternate and Buaya. Unfortunately the anthropology of the Alorese communities living on Pantar Island is yet to be seriously addressed, although it is probably similar to that found on Alor and its offshore islands.

Rodney Needham (1956) did publish some notes about the system of kinship and marriage among the Alorese community of Baranusa on Pantar, but it was obtained from an elderly man from Baranusa who had spent 17 years living on Sumba Island. Clans were patrilineal and traditionally exogamous and, although this restriction had now lapsed, lineages still remained strictly exogamous. Ideally a boy should marry his mother's brother's daughter. Residence was patrilocal.

The Alorese in western Alor are likewise organised into patrilineal suku or clans, which are generally exogamous. Marriage is patrilineal – a woman joins the clan of her husband. For each clan, all the other clans are divided into:

- wife-givers,

- wife-takers and

- clans with which intermarriage is forbidden, known as lallang kakari (brotherhood clans)