Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Pahikung Part 2:

Pahikung Textiles

Lau Pahikung

Lau Pahikung Nggeri

Lau Pahikung Wuti Kau

Lau Pahikung Pakapihak

Lau Pahikung Hiamba

The Use of Lau Pahikung as Costume

The Role of Lau Pahikung in Funerals

Lau Pahikung as Gifts of Exchange

Halenda Pahikung

Tiara Pahikung

Ruhu Banggi Pahikung

Hinggi Pahikung

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Go to Pahikung Part 1

Pahikung Textiles

Over the last century pahikung has been primarily used to decorate women’s tubeskirts (Adams 1969, 80). However it can also be found on almost every type of textile woven in East Sumba, including men’s tiara headdresses, halenda selendang and sashes, ruhu banggi torso wrappers, and less commonly on hinggi waist wrappers and shoulder blankets.

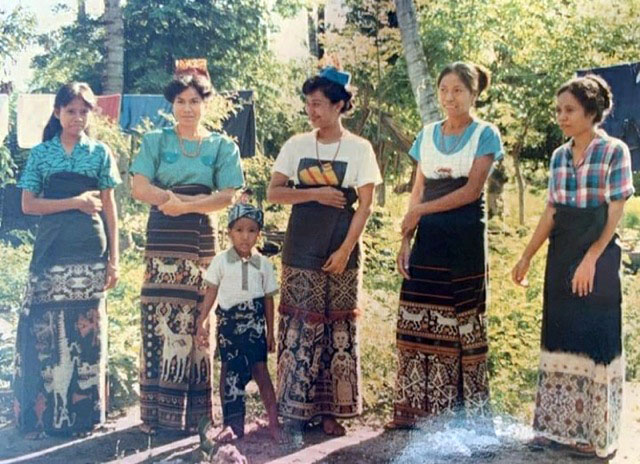

Four members of the royal family of Pau in 1985, all dressed in pahikung.

From left to right: Tamu Rambu Ana Humba, Tamu Rambu Kuddu, Arena Jacob (a student from Java), Tamu Rambu Tokung and Tamu Rambu Paki.

(Image reproduced with kind permission of Umbu Nggaba Haumara, aka Umbu Roman, and his family, Uma Bara)

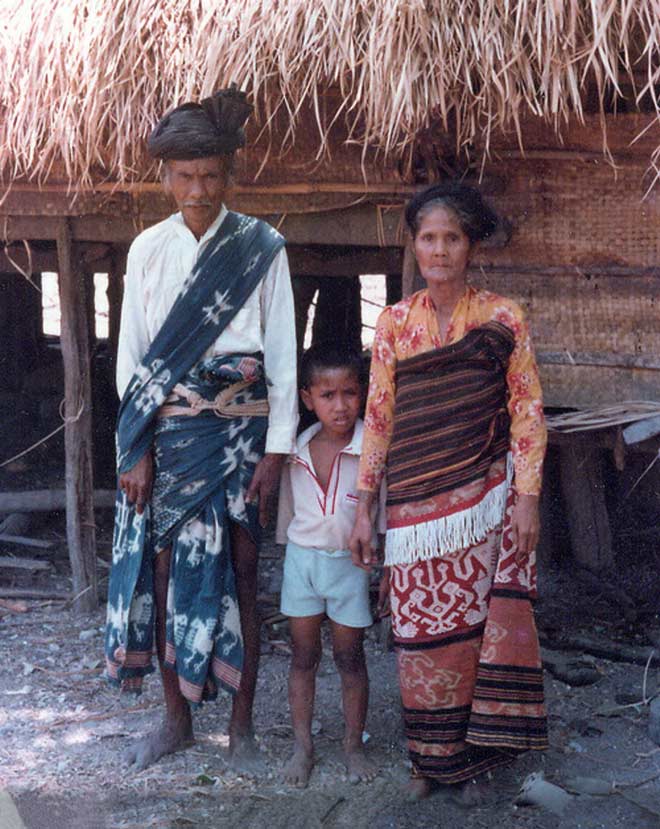

A noble couple dressed in formal attire in a village in Umalulu. Undated.

The woman wears a lau pahikung hiamba nggeri and the man wears a mud-dyed barkcloth kambala headdress with a fanned, upturned end – the sign of a nobleman

(Image courtesy of Dr Purwadi Soeriadiredja, Denpasar)

Pahikung textiles were formerly made by, and restricted to, the nobility - a situation that still applied in the late 1930s (Nooteboom 1940, 88). In the 19th century even dresses decorated with simple shells could only be worn by princesses and their slaves (Roos 1972, 13). Since the declaration of Indonesian Independence in 1949, and the imposition of a regional system of government in 1962, these sumptuary rules have progressively ceased to apply. Yet even today the cost of these textiles limits their use to the better-off commoners.

Tamu Rambu Maramba Bokul wearing a lau pahikung hiamba standing beside her husband, Tamu Umbu Makambombu, in Parai Yawang, Rindi

A noblewoman dressed in a lau pahikung tubeskirt and hai kara jangga headdress carved on a gravestone at Uma Bara

An increasing application of pahikung in recent decades has been for the decoration of halenda sashes which, unlike lau skirts, are a convenient way for tourists to acquire a useable example of pahikung art.

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung

Lau pahikung are normally two- or three-panel tubeskirts woven with at least one wide band of pahikung, although most usually have two and sometimes three or more. In most cases the uppermost panel is plain or warp-striped.

As we shall see later, when we discuss the use of lau pahikung as costume, such garments remained relatively exclusive until the 1930s because they were only produced by the nobility. The majority of women wore a heavy black mud-dyed sarong which was generally undecorated. By the late 1930s, while most ordinary women were still wearing a coarse-textured black sarong, women from good families wore skirts adorned with white and sometimes coloured threads, with outlines of horses, snakes, fish or shrimp (Nooteboom 1940, 88). According to Nooteboom the patterns were usually very simple and largely consisted of a succession of different coloured bands. However one band was always broader than all of the others and was extensively decorated - sometimes with 'an unusual weaving technique based on floating warp threads'.

A simple two-panel lau pahikung, woven in the 1980s by Rambu Jera from Pau.

The main motif represents a weaver’s karanganata or swift. Richardson Collection

In the past lau pahikung were called lau pahudu (see for example Kapita 1976, 245). However on Sumba today they are mainly referred to as lau pahikung, especially by the younger generation (Tamu Rambu Tokung 2016, private communication). This seems a more accurate description, since a pahudu is merely a pattern guide, whereas pahikung is the weaving technique used to make them.

Jasper and Pirngadie referred to various types of lau pahikung as lau kombu, in other words morinda-dyed lau (1912, 281). This is because many Sumbanese describe local skirts in a simpler manner, independently of how they have been made. If they are primarily indigo-coloured they are called a lau kawora, and if they contain morinda they are called a lau kombu. These terms are especially applied to skirts decorated solely with warp ikat – lau hiamba.

Some writers such as Nieuwenkamp and Kapita described the lau pahikung as a lau pahudu kiku (Nieuwenkamp 1923, 309; Nieuwenkamp 1927, 261; Kapita 1976, 240). Nieuwenkamp specifically described such a lau as one in which the weft yarns form the patterns on the front side and then run loose on the reverse, creating an untidy negative of the pattern on the front. He was clearly referring to a lau pahikung but confused the weft threads (inslagdraden) with the warp threads. The word ‘kiku’ means below or tail. A lau pahudu kiku or lau pahikung kiku is therefore simply a skirt with a band of pahikung at the bottom – in other words, a lau pahikung.

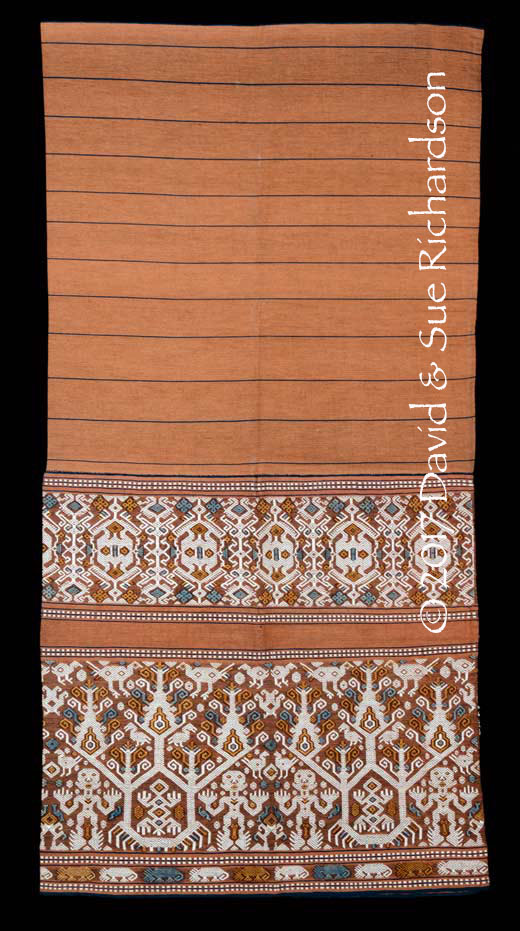

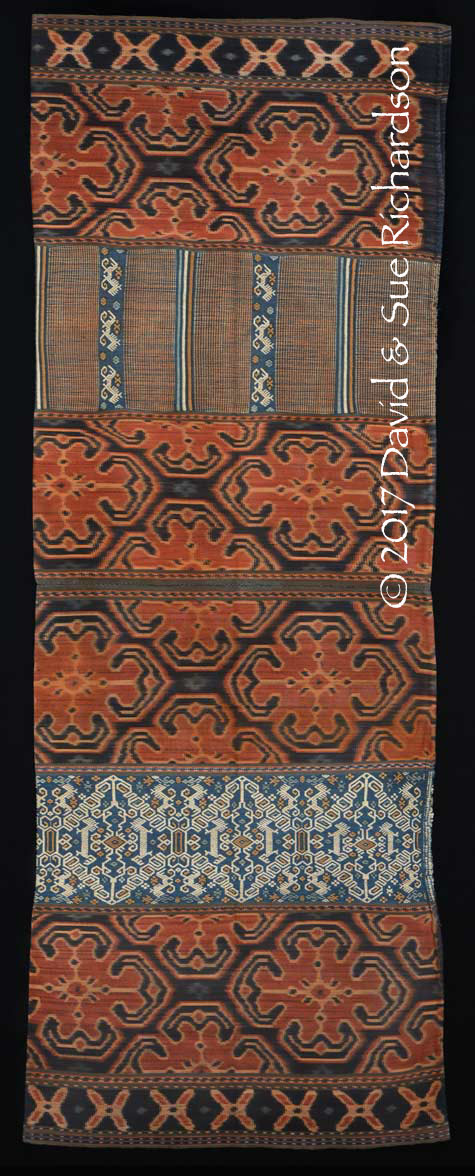

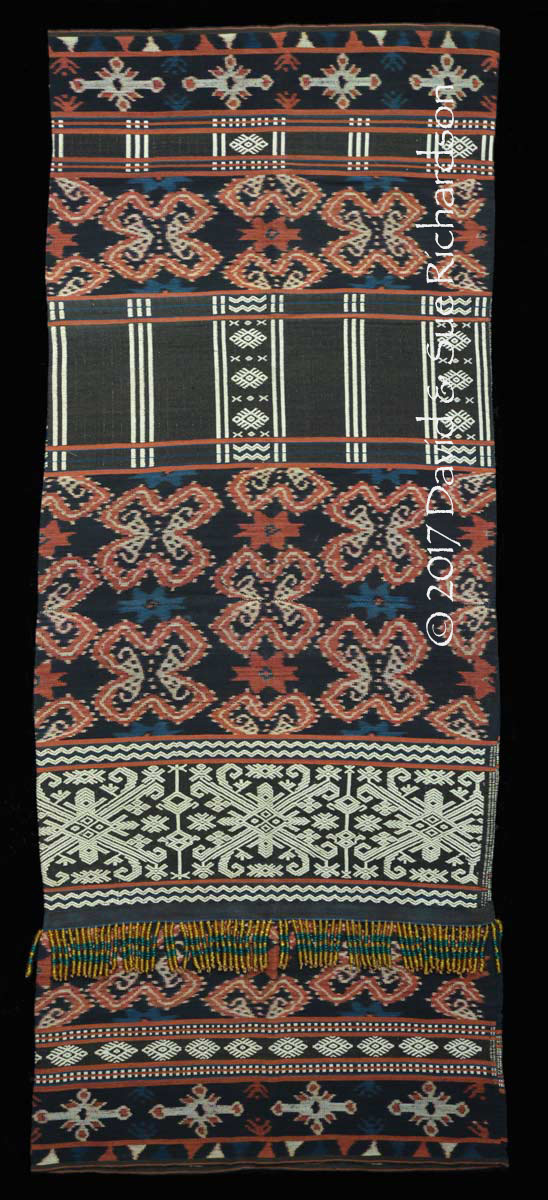

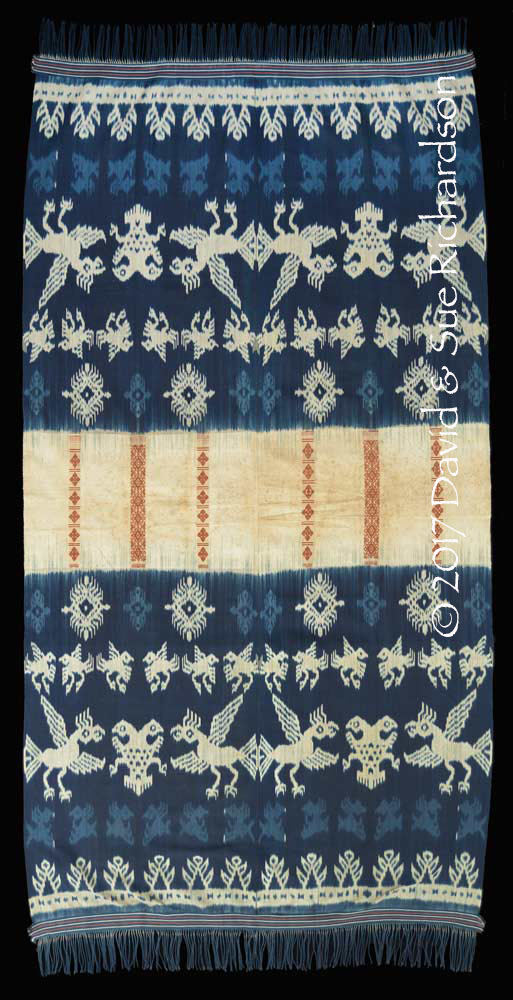

A two-panel lau pahikung that belonged to Tamu Rambu Yuliana of Parai Yawang, Rindi. She acquired it in the 1950s or 60s from a relative in Pau or Uma Bara and in about 1970 gave it to a friend in Melolo. Rambu Yuliana later served as the unofficial queen of Rindi from 1992 to 2003. Richardson Collection.

A three-panel lau pahikung woven in the 1940s by Tamu Rambu Uru Ana Hidda, the wife of Tamu Rambu Retang Tamba Hina Tara. Her father-in-law was Tamu Umbu Hiya Hama Taki II, the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. Richardson Collection.

A three-panel lau pahikung decorated with six bands of supplementary warp. Woven by Rambu Ngana Harakay from Kabaru, rated the finest pahikung weaver in East Sumba.

Richardson Collection

Strictly defined, a lau pahikung is only decorated with supplementary warp. If additional production techniques are involved then these are often incorporated into the skirt’s title.

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung Nggeri

Lau pahikung nggeri are decorated with one or more fringes of twisted yarns. These can be inserted horizontally between bands of pahikung, or into the upper panel in the form of a zigzag. The warp ends can also be twisted into a vertical fringe down the side seam. Horizontal fringes are usually inserted manually during the weaving process, each piece looped around the weft before it is beaten into the warps. Because the ground weave is warp-faced, the fringe is concealed from view on the reverse of the fabric.

A two-panel lau pahikung nggeri with a linear horizontal fringe, woven about 60 years ago by Tamu Rambu Hara Adji, the daughter of Umbu Hiya Hama Taki II, the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. She died in Patawang in August 2019. Richardson Collection

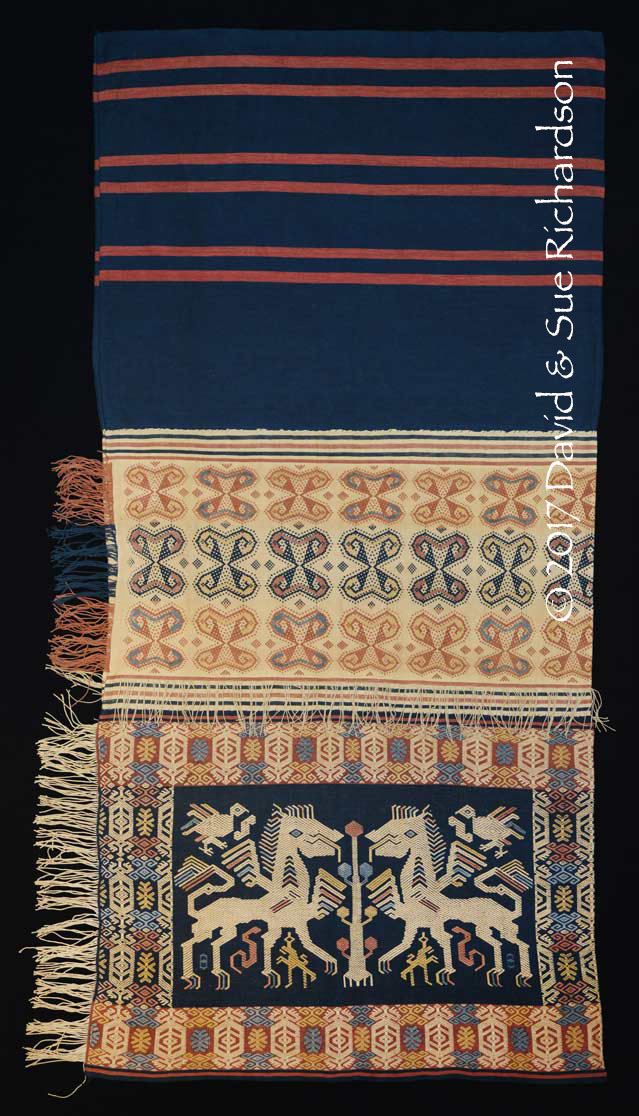

A three-panel lau pahikung nggeri, probably woven in Pau, with a horizontal fringe inserted into the central panel and a vertical side fringe formed from the warp ends. Richardson Collection

A three-panel lau pahikung nggeri with a zigzag fringe inserted into the upper panel, which has been woven in the tinu pata technique. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung Wuti Kau

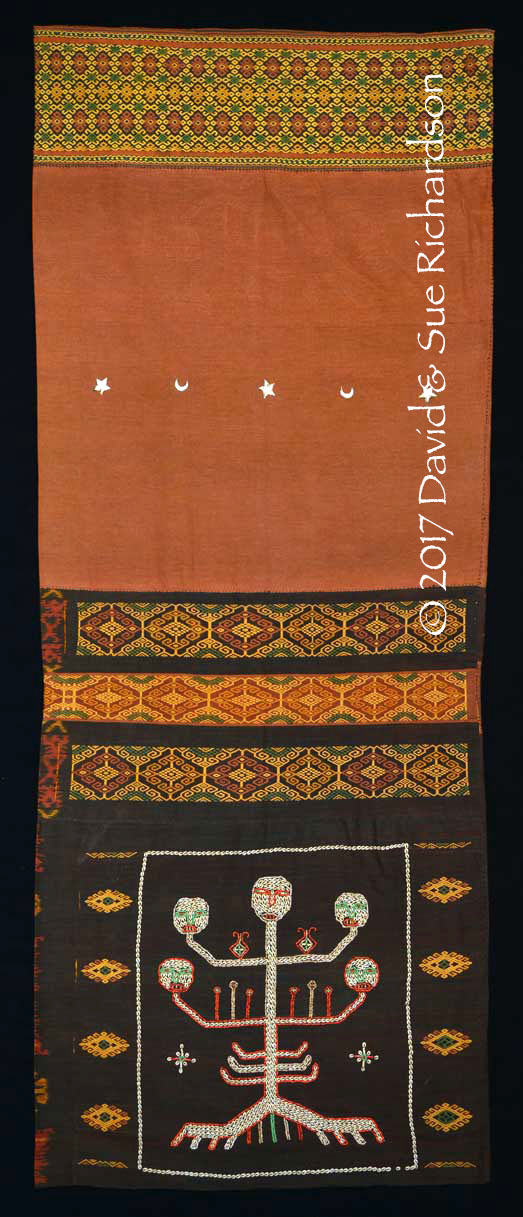

Lau pahikung wuti kau usually combine one or more panels woven in pahikung with a panel embellished with a pictorial motif of appliqued white nassa shells. These tiny seashells, which belong to the Nassarius or dog whelk genus, must first be split in half or be ground down, since only the lip of the shell is used for decoration. The split shells are often combined with coloured glass beads (hada).

A three-panel lau pahikung wuti kau from Kabaru, close to Pau, embellished with two ancestor (marapu) figures appliqued in shells and outlined with glass beads. Richardson Collection

A four-panel lau pahikung wuti kau produced in Pau and embellished with a skull-tree (andung) motif using a mixture of shells and beads. Richardson Collection

Nieuwenkamp discovered in 1918 that embellishments which had been previously been made using nassa shells were now only being done using beads. This was because the latter were easy to buy compared to the effort required to gather the necessary shells and to grind them down and insert the holes for threading (1923, 309). This was despite the fact that the shipping blockade during the First World War had led to a great shortage of beads on the island and, as a consequence, a sharp increase in their price.

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung Pakapihak

Lau pahikung pakapihak are skirts that have been mud-dyed. On Sumba mud-dyed skirts are often called lau pakapihak, occasionaly shortened to lau pihak. The word piha means to fall or wilt and is modified by ka.-.k into kapihak meaning mud. The prefix pa turns the noun into a verb, so the process is called pakapihak – literally to mud or muddy.

There are two types of lau pakapihak – those that have been woven from mud-dyed yarns and those that have been mud-dyed after they have been made.

The old dyers and weavers referred to the latter as a lau pa ka kuamba. The kuamba is the outer casing of the unripe fruit of the betel nut palm, Areca catechu, which is rich in tannins. In the past they covered the woven lau with kuamba before it was soaked in the stagnant mud containing the ferrous iron mordant.

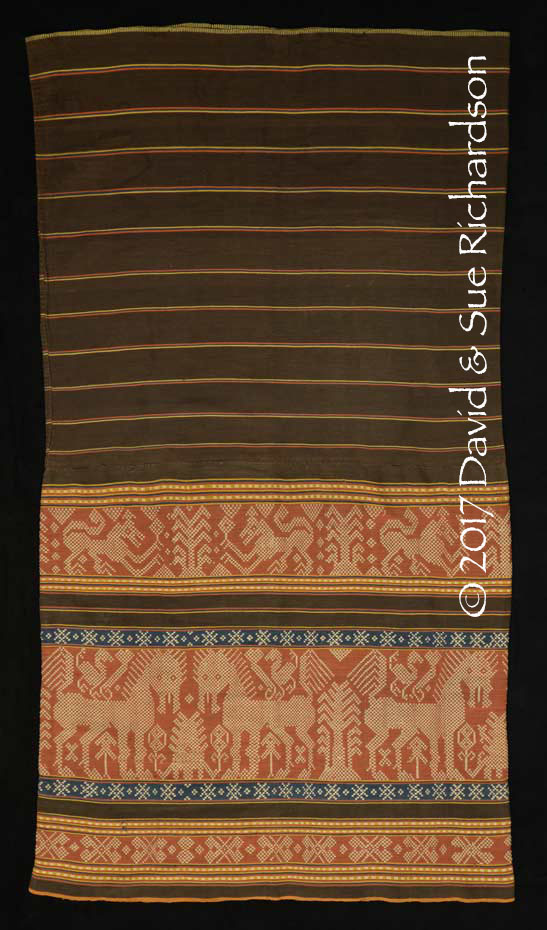

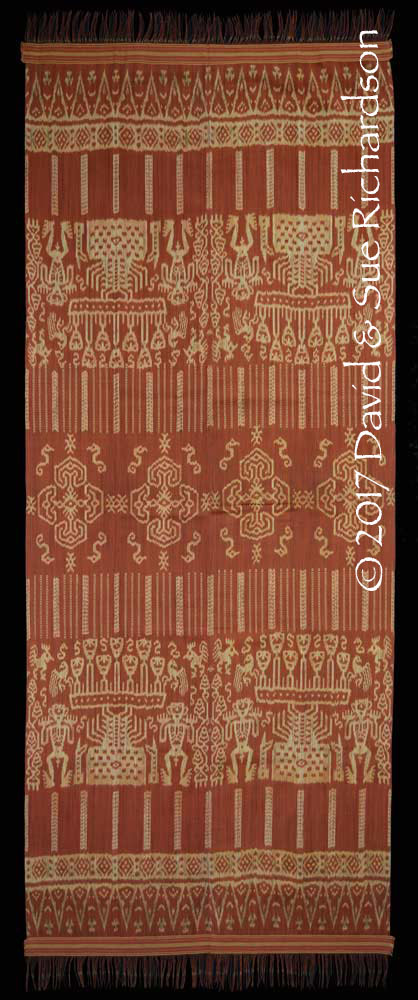

A lau pahikung pakapihak woven at Tambahak, close to Pau, using yarns that were mud-dyed at Waimarang. The design is called ma-katoba, meaning crazy person (literally lunatic or idiot). Richardson Collection

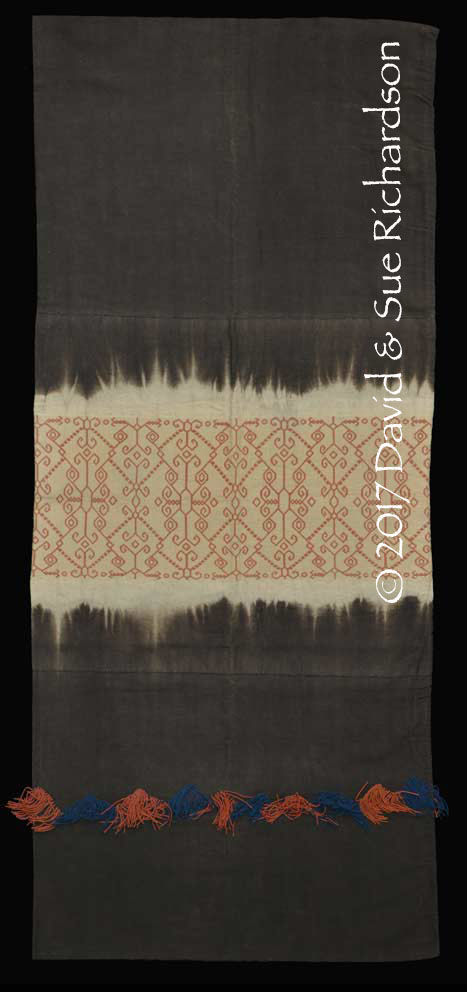

A lau pahikung nggeri pakapihak, also known as a lau pa ka kuamba, woven by Tamu Rambu Hara Adji, the third daughter of Tamu Umbu Hiya Hama Taki II, the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. The skirt was woven before being zone mud-dyed. Richardson Collection.

A three-panel zone mud-dyed ceremonial lau pahikung nggeri pakapihak, also known as a lau pa ka kuamba, woven a century ago by the grandmother of Tamu Rambu Pakki at Pau. Richardson Collection

An old two-panel lau pahikung nggeri pakapihak with beaded fringes, woven at Ngeangandi from mud-dyed yarns and decorated in basket weave with a freshwater crayfish (kurangu).

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung Hiamba

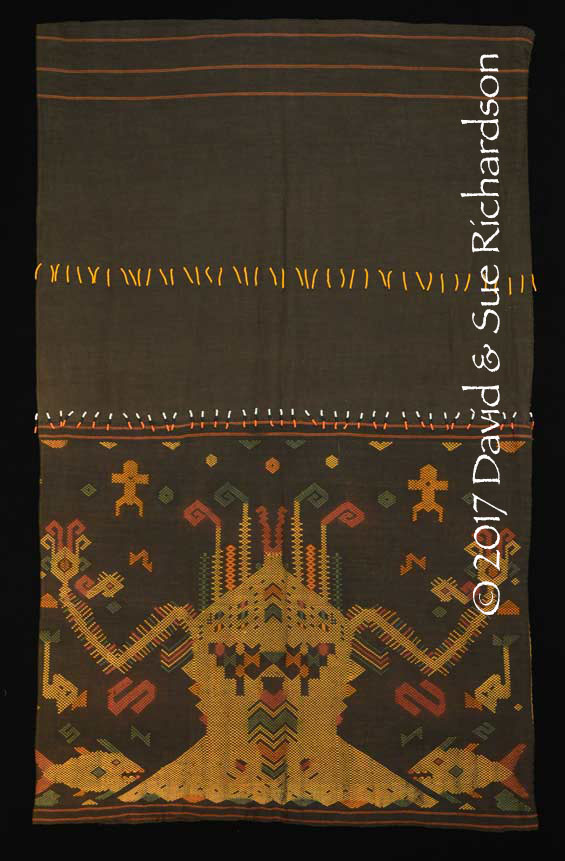

Lau pahikung hiamba are ceremonial two- or three-panel tubeskirts decorated with a combination of pahikung and warp ikat (hiamba). They are the most complex form of the lau pahikung – the pinnacle of East Sumba textile art – requiring the integration of two widely different decorative techniques – supplementary warp and warp ikat.

The existence of these beautiful objects is a result of the long term alliance between the Ana Mburungu clan of Parai Yawang in Rindi and the Palai Malamba clan of Pau in Umalulu, the former traditionally taking some of their wives from the latter (Forth 1981, 11). In addition the Ana Mburungu clan also took wives from the noble Kaliti clan of Waijelu and the ruling clan of Tabundung (Forth 1981, 223).

As a consequence, daughters of the noble Palai Malamba clan who are raised in Pau and become proficient in the weaving of pahikung move to join their husbands in Parai Yawang where they are then taught to bind and dye warp ikat. In addition young women who have been raised in Parai Yawang are sometimes sent to live with relatives in Pau to learn how to weave pahikung.

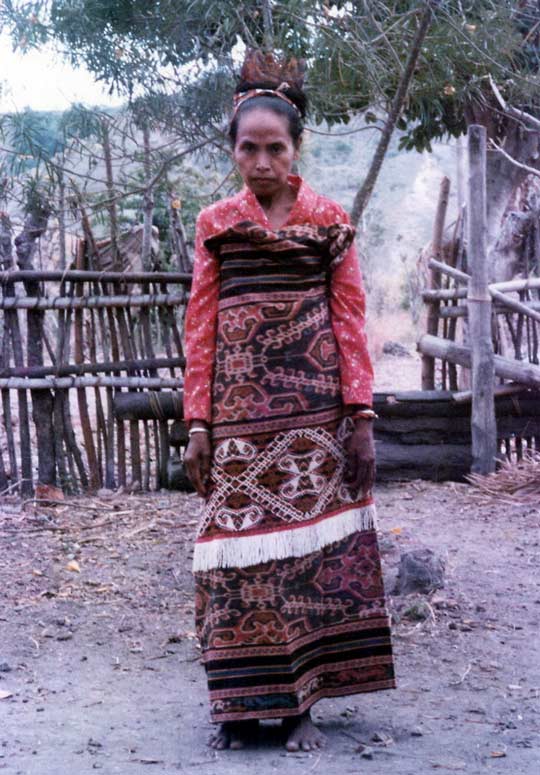

A woman from the noble Palai Malamba clan wearing a lau pahikung hiamba nggeri at a village in Umalulu. Undated. (Image courtesy of Dr Purwadi Soeriadiredja, Denpasar)

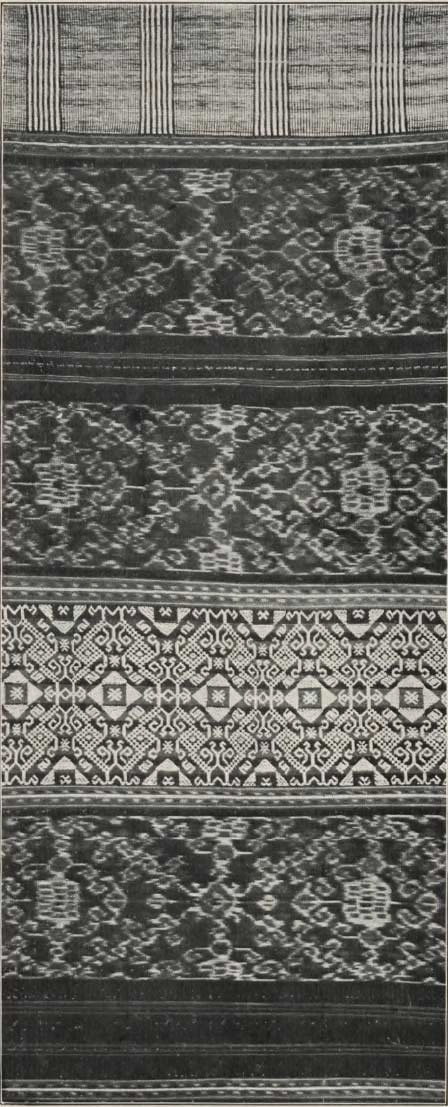

It is clear that lau pahikung hiamba sarongs were in fashion long before the commercialisation of East Sumba weaving. H. Witcamp, a geologist of the Bataafsche Petroleum-Maatschappy, acquired four of these sarongs in 1910. In the following year he donated them to the Colonial Museum in Haarlem, who in turn passed them onto the Colonial Institute. Bernhardus Marius Goslings, the ethnographic curator at the Tropical Institute, described them as lau pahudu kiku (Goslings 1920).

One of the lau pahikung hiamba acquired by Witcamp in 1910

Nieuwenkamp, who had also described lau pahikung as lau pahudu kiku, suggested that skirts that had been decorated with both pahikung and ikat were simply called an ikatted lau kombu (1923, 309). More recently the Sumba historian and linguist Umbu Hina Kapita referred to them as lau pahudu hemba (Kapita 1976, 239). Marie Adams, and later Mary Hunt Kahlenberg, referred to them as lau pahudu padua, a rather confusing and meaningless term, padua meaning middle (Adams 1969, 91: Kahlenburg 2010, 322).

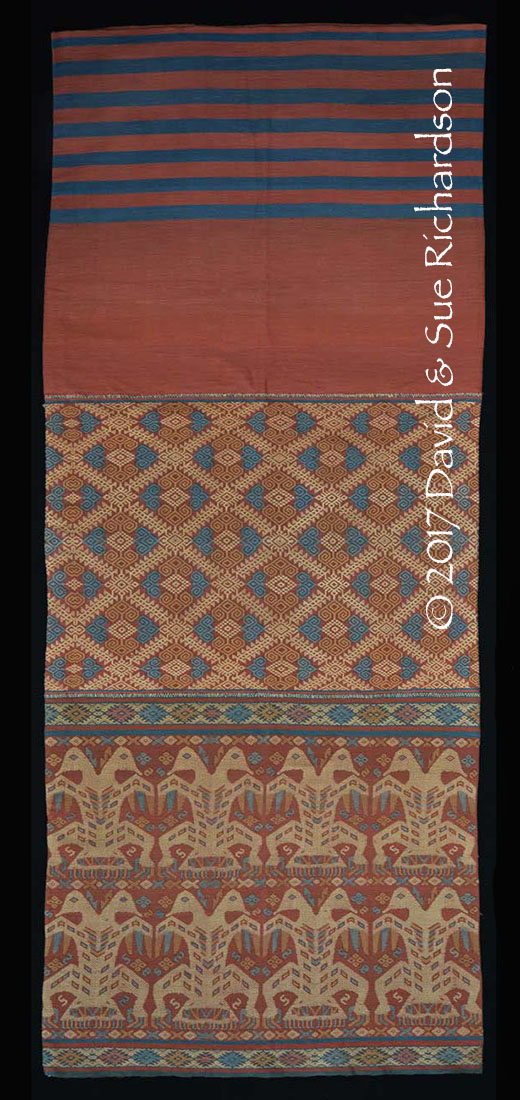

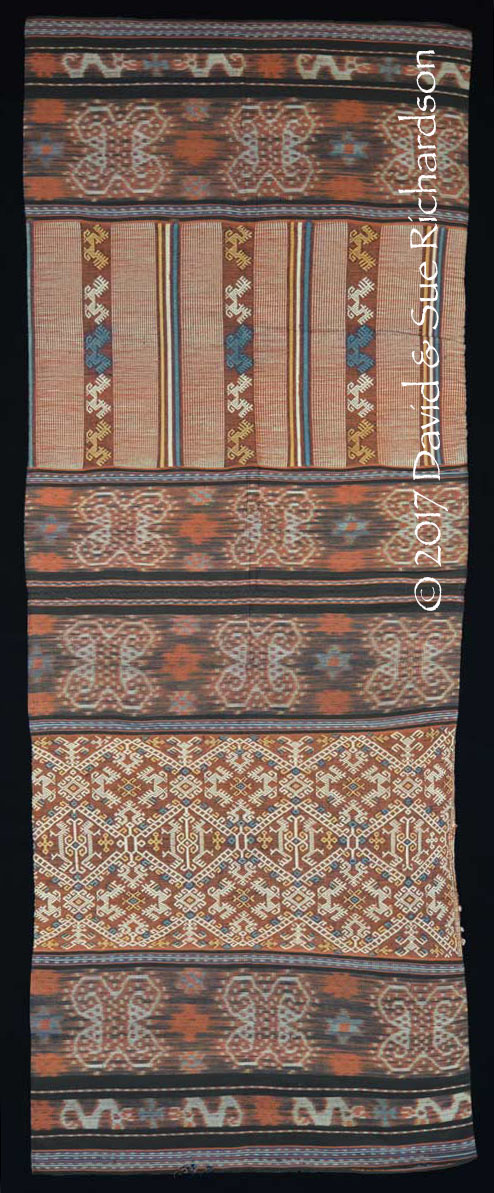

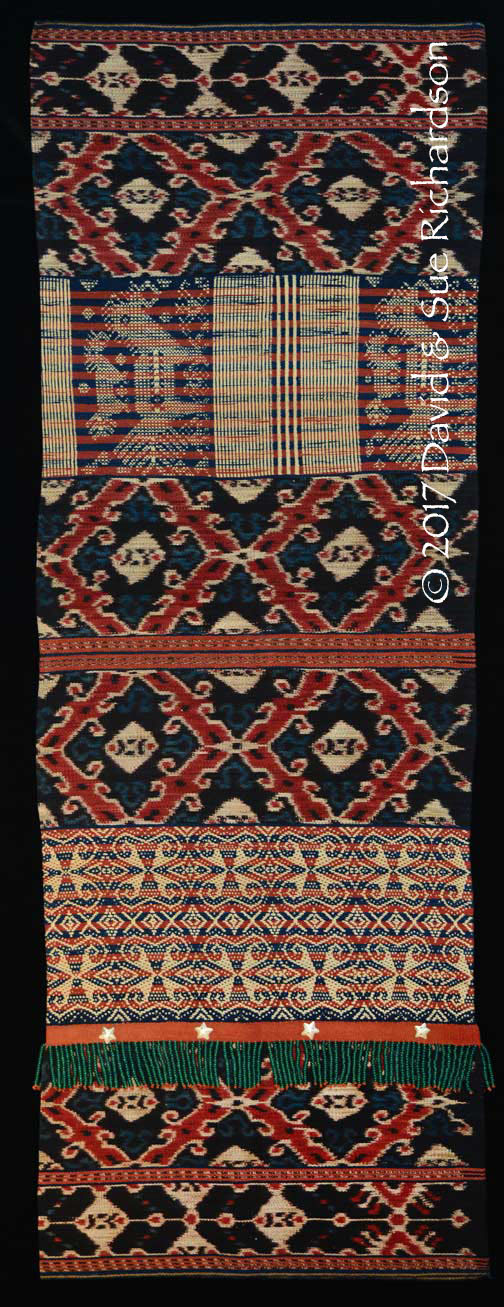

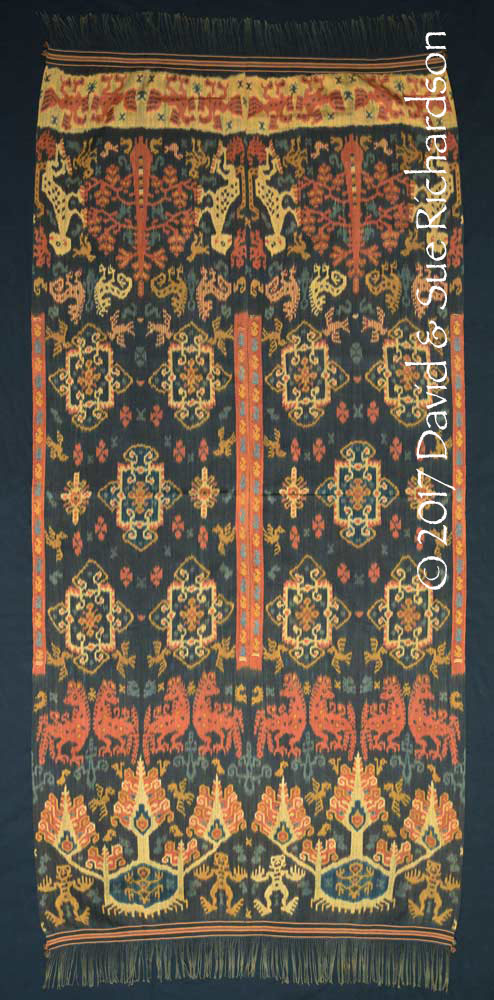

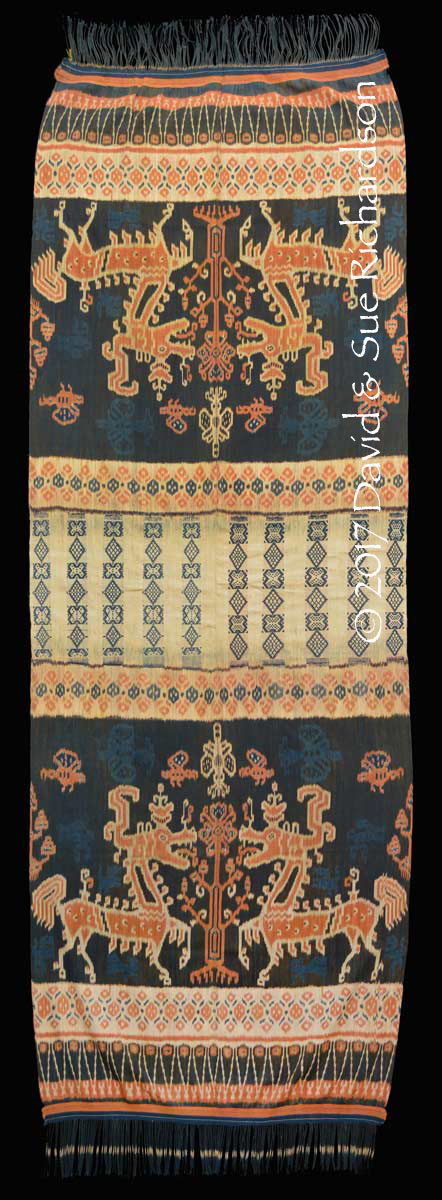

Lau pahikung hiamba with ikat bands bearing the habak flower motif. Woven in Pau roughly 50 years ago using ikat made in Parai Yawang by Tamu Rambu Ana Motur, one of the best ikat producers of her generation. Richardson Collection

Lau pahikung hiamba with ikat bands bearing the karihu butterfly motif. Woven in Pau using ikat made in Parai Yawang. Formerly in the collection of Umbu Wanggi Keimaruku, the Raja of Rindi from 1962 until his death in 1992. Richardson Collection

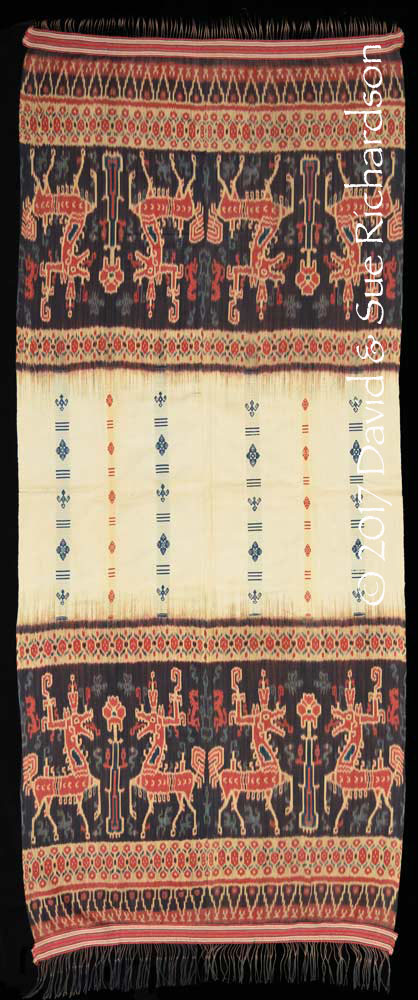

Lau pahikung hiamba woven about 50 years ago by Tamu Rambu Uru Ana Hidda, the wife of Tamu Umbu Retang Tamba Hina Tara. His father was the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. Richardson Collection

Lau pahikung hiamba woven about 45 years ago by Tamu Rambu Hunggu Djawa, a princess in the royal family of Pau. Her formal title was Tamu Rambu Wori Hama. Richardson Collection

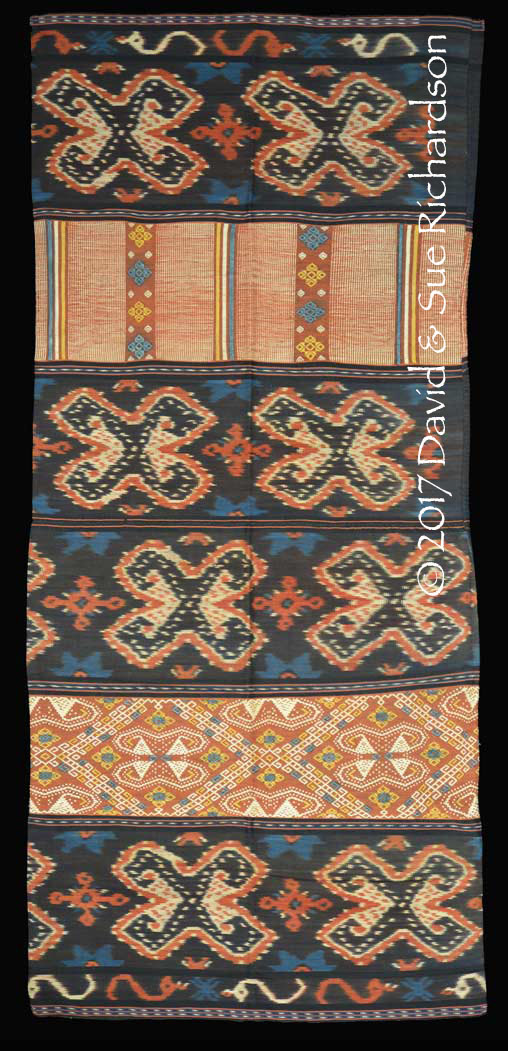

A very heavy hand-spun lau pahikung hiamba nggeri produced recently by Tamu Rambu Hamu Eti, the current queen of Rindi. She bound the ikat but the lau was woven in Pau by a male pahikung weaver. The pahikung is woven on a ground of mud-dyed yarns. Richardson Collection

A very heavy hand-spun lau pahikung hiamba nggeri, claimed to have been woven by Tamu Rambu Yuliana (the former Queen of Rindi) at Parai Yawang. She was the exclusive owner of the tiara ndai ikat motif. It it more likely to have been made by one of her close relatives. Richardson Collection

The production of a lau pahikung hiamba is the ultimate challenge for a pahikung weaver. The first task is to form the circular warp for the ikat section and to tie, dye and untie it, both for the initial indigo-dyeing phase and the later morinda-dyeing phase. The ground and supplementary warps must then be wound onto the warping-up frame so that they have precisely the same length as the ikatted warps. The two warp sets are then transferred to the wungi pahikung frame. After finely focussing the pattern, the ikatted warps are locked together in alignment by tying them in bundles to a thin bamboo lath.

The wungi pahikung frame for arranging the warps and programming the pahikung pattern for a lau pahikung hiamba, Parai Yawang

Tamu Rambu Hamu Eti with her husband, Tamu Umbu Kanabu Ndaung, the Raja of Rindi, pointing out some features of their wungi pahikung frame for setting up the warps and heddle

The pahudu pattern is now transposed onto the supplementary warps using extra long lidi sticks that ride above the ikatted warps. Once a section of the pahikung bands has been pre-programmed in this way the entire warp set can be transferred to the back-tension loom so that weaving can begin. Weaving can be interrupted at any stage and the warps rolled up and stored away for another day.

A back-tension loom with a partially woven lau pahikung hiamba at Parai Yawang.

The finger is pointing to the stick used to control the tension of the supplementary warps

Return to Top

The Use of Lau Pahikung as Costume

Lau pahikung range widely in quality - some costing just tens of dollars, others many thousands. Less expensive skirts are often made to be worn, especially for formal events like marriages, baptisms and funerals. They are also frequently worn by dancers.

A lau pahikung hiamba woven with simple bands of warp ikat and intended to be worn

Modern lau pahikung hiamba being offered for sale at Parai Yawang, Rindi.

A young dancer dressed in a lau pahikung at Marumata, 1991

In the past lau pahikung were relatively rare, accounting for just a small proportion of all women’s sarongs. The vast majority of women throughout East Sumba wore a coarse black cotton two-panel tubeskirt that was either plain or simply decorated. It was long and worn high under the armpit or, if more voluminous, pulled up over the right shoulder (Nieuwenkamp. 1923, 309).

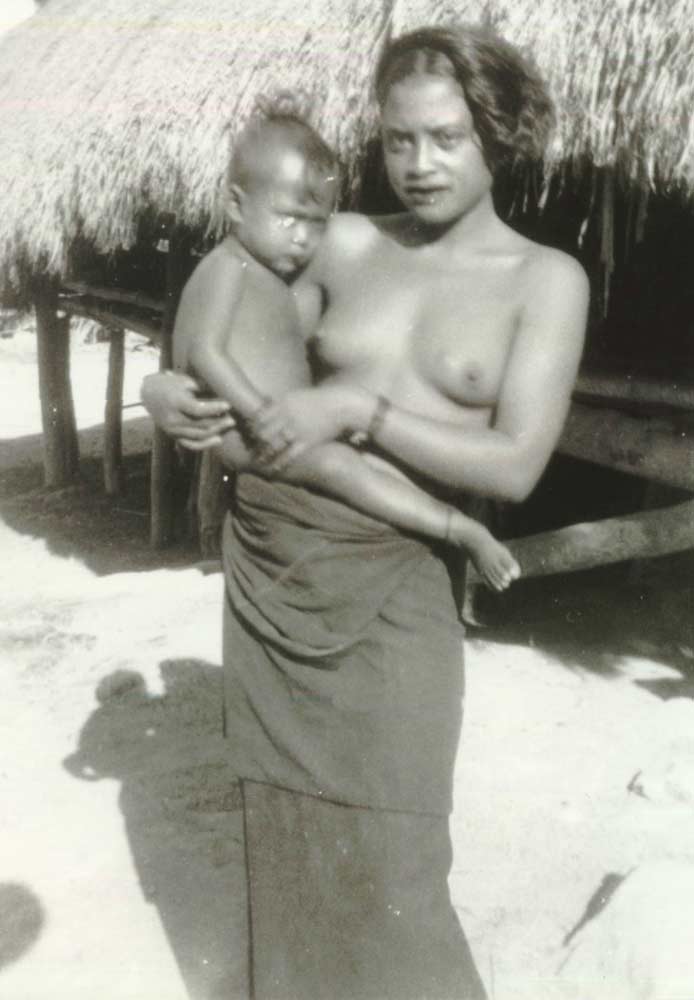

Diderik Johan van den Dungen Gronovius, who had been the Dutch Resident at Kupang between 1836 and 1842, spent seven months on Sumba Island in 1846. He reported that the dress of the Sumbanese was simple but dirty. Women wore a long, black, very narrow sarong of native cloth, usually embroidered on the lower side with small corals or sea-shells of different colours (Van Hoëvell 1855, 289). Samuel Roos, the first Kontroleur of Sumba from 1866 to 1873, confirmed that women’s dresses were very simple, consisting of a narrow cotton ‘laauw’, which was thick, coarse and dyed black and sometimes interwoven with figures or decorated with beads and small seashells (Roos 1872, 13). These were usually worn with the breasts exposed and were long enough to be drawn up over the head during cold nights. The only women’s skirt acquired by Ten Kate was a black lau hada decorated with coloured beads from Taimanu, just north of Waingapu (1894, 551).

The black skirt continued to be the most common form of women’s dress well into the twentieth century. The Dutch missionary-linguist Albert Kruyt, who conducted a three-month survey of Sumba with the missionary Wielenga in 1920, found that the only garment worn by women was a long black skirt, called a lau in the east and a rabi in the west (Kruyt 1921, 516). It was fastened around the waist, with the upper half hanging down while working, leaving the breasts uncovered. The naturalist Karel Dammerman, who visited Sumba in 1925, reported that the only garment worn by women was a heavy, durable black sarong that did not cover the upper part of the body (Dammerman 1926, 52). However women quickly covered themselves when they saw a European. Everything was dirty, and as garments made from white cloth became black with the dirt they were not washed but were instead dyed black – most likely with tannins and mud. These black sarongs were undecorated apart from two fringes, one above the other. The Dutch civil-servant-cum-ethnologist Christiaan Nooteboom, who was stationed in East Sumba in the mid-1930s and spent over one-and-a-half years on the island, found that ‘simple’ women wore a coarse textured black dress, which was folded under or above the breasts and fastened by rolling the folds inwards. The exposure of the upper body was not regarded as inappropriate, although contact with Europeans had led to some feelings of shame about being uncovered (Nooteboom 1940, 91-92).

Young mother wearing a plain black cotton lau in 1932

(KITLV, Leiden)

Many years later in the mid-1970s when Gregory Forth was conducting his 22 months of fieldwork in the royal village of Parai Yawang, he found that although women still wore a long tubular skirt or laü, most daily clothing was made from purchased cotton or synthetic material. Just as black clothing had been preferred in the past, not a lot had changed. Women still wore skirts that were black or a shade regarded as black such as dark blue or green.

Up to this time lau pahikung were strictly restricted to the maràmba or nobility. Thanks to the complex weaving technique involved, it was easy for any noblewoman to control and restrict the production and distribution of her own pahikung textiles. Each weaver exercised tight control over her personal collection of pahudu patterns, some designed by her and others inherited. Only she or one of her many slaves could program and weave the supplementary warps according to that pattern.

According to Roo van Alderwerelt, the civiel gezaghebber on Sumba from 1885 to 1888, women’s sarongs woven with figures of birds, monkeys and men, along with black beaded sarongs decorated with shrimps, lizards and scorpions, could only be worn by the maràmba or nobility (1890, 593). In particular, the women from the region of Melolo who had a reputation for weaving the finest fabrics, made a clear distinction between the cotton textiles produced for the nobility and those made for the commoners or kabihu (Roo van Alderwerelt 1890, 594).

These restrictions lasted well into the twentieth century. Dammerman observed that the better-off sometimes owned a sarong adorned with rows of silver coins or with figures sewn in white yarn or with white beads (Dammerman 1926, 52). A decade later Nooteboom recorded that women from good families wore skirts adorned with white and sometimes coloured threads, with outlines of horses, snakes, fish or shrimp (Nooteboom 1940, 88). Others wore skirts decorated with shells or half-guilder coins and, in some cases, with gold. Many of these sarongs were decorated with woven coloured figures similar to those found on men’s blankets. The patterns were usually very simple with a succession of different coloured bands, but one band was much broader and was extensively decorated, sometimes using a weaving technique with floating warp threads (Nooteboom 1940, 88). Nooteboom found that blouses were worn by higher-status women and on festive occasions, but thought that this practice was not traditional.

At Parai Yawang in the mid-1970s woven decorative skirts were still generally only worn on ceremonial or festive occasions, normally in combination with a blouse (Forth 1981, 16). Today women wear skirts made from a wide range of fabrics, including plain cottons, synthetics, batik, and ikat. Many younger women wear jeans and long shorts. However in rural East Sumba there is still, in our opinion, a preference for black - especially among the nobility.

Women wearing black warp ikat sarongs (lau hiamba) at a village festival in Kambera

Although modestly decorated black lau are still generally preferred for attendance at funerals, there are no longer any fixed rules. Lau pahikung can also be worn and these often have a black ground, but sometimes brightly coloured versions are worn as well.

Three out of these eleven women are wearing a lau pahikung at the funeral of Umbu Hunga Meha at Nggongi in 2015.

Lau pahikung worn by attendees at funerals in East Sumba

Return to Top

The Role of Lau Pahikung in Funerals

In East Sumba a funeral or taningu is by far the most important ceremony in a person’s life. The marapu or ancestors are highly revered and so it is absolutely vital that after a person’s death the appropriate rituals are strictly adhered to, in order to ensure their smooth passage to join their ancestors in the afterlife. The death and subsequent funeral of a high noble is of immense importance, and may be attended by thousands of mourners (Forshee 2001, 30).

The rituals associated with death and burial vary from region to region (see for example Kruyt 1922, 539). When a person dies in the Kambera, Umalulu and Rindi regions, the body is washed in coconut oil and placed in a foetal position with the hands resting on the cheeks and the legs folded inwards so that the knees are close to the elbows (Kruyt 1922, 521; Forth 1981, 172). Mamuli and/or coins, which are intended to provide wealth in the afterlife, are placed in the mouth and the hands. Two saucer-shaped slices of dried coconut wrapped in cloth are placed under the chin to keep the head upright (Forth 1981, 173). Finally the body is wrapped in textiles, primarily provided by members of the deceased’s clan. The richer a person is, the greater the number of cloths used to wrap their body (Kruyt 1922, 522).

In the case of a woman, the body is dressed in many lau of varying quality. Traditions vary from village to village. Gregory Forth found that in Rindi a female corpse was first dressed in an ordinary black tubeskirt, and then covered with a skirt decorated with red dye – a lau kombu (Forth 1981, 172). Other skirts might be added later, tied above the head and below the feet. Today it is common to dress the corpse in a number of skirts, the two finest being worn innermost, next to the body, and outermost. When the body is dressed in many skirts the last lau of all must be very wide and is sometimes referred to as a lau payubuh, the term payubuh meaning to cover the sleeping body with a cloth. A tortoiseshell comb or hai kara jangga is placed in the hair and sometimes jewellery is added. The dressed body is finally covered with several red shrouds (tera tamali) and placed in a quiet position in the main room of the house, facing the principal house post. For the first few months after death a member of the family, generally a woman, will sit and guard the body and from time to time ritually feed it and offer it betel nut. In the case of a commoner, the family will continue to live, cook, eat and sleep in the same room as the corpse - separated only by a curtain or partition. Noble families have larger houses and are more likely to place the body on its own in a separate room.

The body of a noblewoman raised on a dais partially covered with a lau pahikung. Baskets of lime, areca nut and betel catkin lie at the foot of the table. Parai Yawang 2014.

The body of the great ikat producer, Tamu Rambu Ana Motur, lays in state in 2017 at her home of Uma Andung, Parai Yawang. The ikat-wrapped body is covered with two lau pahikung hiamba and one lau pahikung, as well as two Indian sarees.

At a later stage the body is rewrapped and placed in a laying position inside a coffin raised on bearers. The coffin is then covered with more lau, especially lau pahikung. Because there is a large Savunese community in Melolo, many local men have Savunese wives. When a woman from Savu dies, her body will be treated in exactly the same way, although her coffin will be covered with a Savunese èi (most likely woven on Sumba).

In the meantime other deaths may occur in the family, leading to several coffins being arranged side by side within the house until they can all be buried simultaneously at a single funeral event.

Four deceased relatives – two female, two male - inside a commoner’s house at Wukuramba. The first death occurred 12 years ago. The two women’s coffins are decorated respectively with a Savunese èi and a Sumbanese lau pahikung.

The body of a noblewoman is dressed in a larger number of skirts, some of which will be very high quality lau pahikung. As she passes into the next world to join her ancestors, these textiles, along with her jewellery, coins and items of gold will proclaim her noble status and provide her with wealth in the afterlife. Tamu Rambu Yuliana even designed and produced a lau pahikung hiamba to be worn for her own funeral (Breguet 2006, 219).

While slaves may be buried within a few days, the coffin of a commoner or noble usually remains unburied for a significant period, in some cases for more than a decade, while the family assemble the huge resources required to stage the funeral ceremony.

The coffin of Tamu Rambu Hada Pawulung, wife of Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha, draped with a black lau pahikung and a black lau hiamba at Nggongi, Karera

Once the extended family are ready to hold the funeral, the clan priests or ratu are consulted to agree an auspicious day. The relatives of the deceased are formally invited, but it is customary tradition that villagers and the nobility from the surrounding area are welcome to attend. Mourners begin arriving on the day before the funeral and spend time paying their respects in front of the coffin before being provided with food and overnight accommodation by the family and their friends and relatives. It is normal for guests to bring gifts, of which textiles – including pahikung – are the most common.

At the funeral of a noble the quantity of textiles can be enormous, with the local ratu recording and bagging up every item. These will later be shared out among the relatives of the deceased.

Gifts of modern pahikung and other textiles from guests to the royal family of Karera at the funeral of Tamu Umbu Hanga Meha in 2016

Once the body is in the tomb more textiles, brought by the guests, may be placed around it. When Tamu Rambu Yuliana was buried at Parai Yawang in 2003 about a hundred textiles were offered in this manner. Previous funerals of important people had seen several hundreds offered (Breuget 2006, 215).

As mentioned earlier, in the past lau pahikung were strictly restricted to the nobility. However there was one exception – they were also worn by slaves or lower- ranking commoners who had been selected to fulfil the ceremonial function of a ritual attendant or papanggang (or papanggangu) at the funeral of a noble. The papanggang are composed of an equal number of men and women, with each male functionary having a female counterpart. The total number of papanggang can range from two to eight. In Rindi the maximum is six and would be composed as follows, regardless of the gender of the deceased:

| Male papanggang | Female papanggang |

| Makaliti njara, who rides the deceased's horse to the grave | Matidungu tubuku, who wears a tall conical hat covered with a red veil |

| Malunggu manu, who carries a cockerel under his left arm | Mayutu kàpu, the bearer of the woman’s betel bag |

| Mahalili kalumbutu, the bearer of the man’s betel bag | Matanggu tuku, who pounds the betel chew for the deceased |

(Forth 1981, 197).

The ceremonial attire of the female papanggang varies from funeral to funeral, and is elaborated according to their rank as indicated by the sequence in which they are listed above. The female papanggang who wears the hat and veil is the most important and, if only two attendants are employed, she is the one who undertakes all of the other female tasks (Forth 1981, 198). The attendants are dressed on the day of the funeral, seated next to the corpse inside the house. In the case of the costume for the female attendants there does seem to be a preference for the lau pahikung, although other types of lau are permissible. In Rindi the attendants were rewarded for their service by being treated with special respect and being allowed to keep the ceremonial clothing that they wore (Forth 1981, 199).

A matidungu tubuku female slave at Kambaniru, near Waingapu, in 1932 wearing a very fine lau pahikung hiamba. (L. C. Heyting Collection, Leiden University)

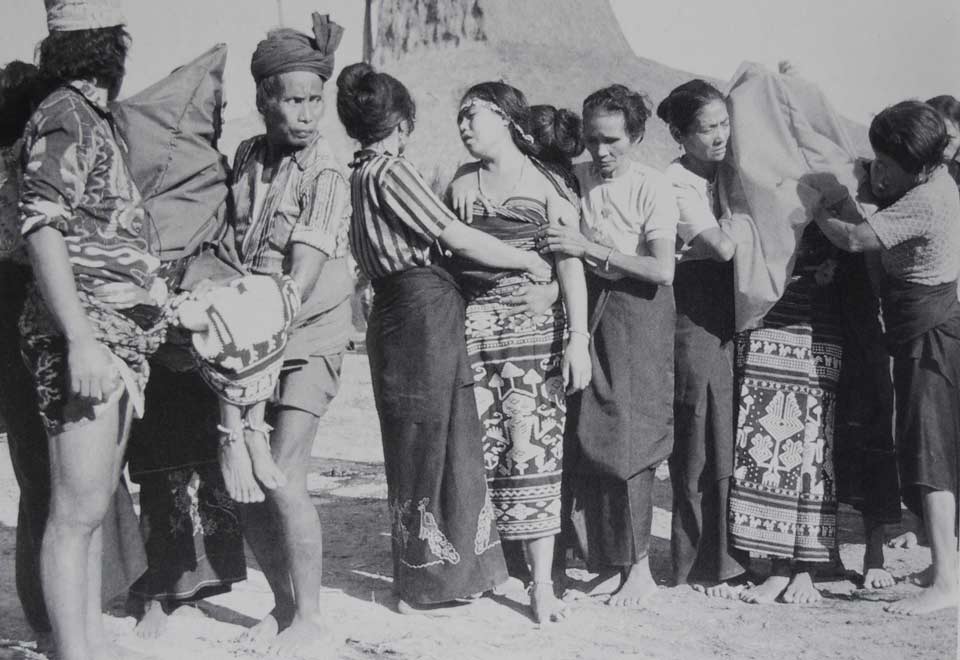

Male and female papanggang at the funeral of Rambu Ndai Pakonggalong, the wife of Umbu Rara Lunggi, at Parai Yawang in 1935. (Nooteboom 1940, plate 4)

Three female papanggang in a trance at the 1981 funeral of Tamu Umbu Windi, the Raja of Pau. They are all dressed in ceremonial lau pahikung. Two have their heads covered.

Of the four female papanggang at the funeral of Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha at Nggongi in 2015, only one wears a lau pahikung.

During the burial ritual the papanggang fall into a trance, and must be given assistance to reach the graveside. In this state they are believed to enter the world of the dead to accompany the soul of the deceased to the after world. Indeed the term papanggang is derived from the verb pangga, meaning to step, walk or cross over (Forth 1981, 198).

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung as Gifts of Exchange

The finest lau pahikung and lau pahikung hiamba are prestige heirlooms that are seldom worn, even for ceremonial purposes. They are primarily used as gifts of exchange at the time of an arranged marriage between closely related families, especially among the higher nobility (maràmba bokulu). The most highly valued women’s skirts in Rindi were the lau pahudu (Forth 1981, 363-364).

Marriage in East Sumba is exogamous – marriage within the same clan (kabihu) is forbidden. Generally a wife should be taken from an allied clan that has a tradition of providing wives to the clan of the groom. Ideally this should be the clan of the groom’s mother's brother. As an example, the ruling Ana Mburungu clan of Rindi take some, but not all, of their wives from the Palai Malamba clan of Umalulu (Forth 1981, 11). The alliance between those clans must be asymmetric. While the wife-givers supply brides to the wife-takers, the wife-takers cannot supply brides in return. Their daughters must marry into a third clan with which there is a similar long-tern asymmetric alliance.

In the past marriages were arranged between families well in advance, sometimes while the couple were still in their infancy. This is less strictly the case today with the exception of the nobility. Sumbanese society remains rigidly classified into the nobility (maràmba), clan members or commoners (kabihu) and slaves (ata). Although the Indonesian government dismantled the royal system in 1962 and slavery is illegal, local nobles who hold the titles Tamu Umbu and Tamu Rambu ('named lord' and 'named lady') still command great respect, while the destitute and uneducated still act as unpaid indentured servants in return for shelter and sustenance. In marriage, class endogamy is preferred – if a man marries outside of his class, he normally marries down. It is therefore vital that members of the higher nobility marry among their own class.

The formation of a marriage alliance demands the exchange of gifts between the clans or lineages of the wife-givers and the wife-takers, the former always considered to be superior in status to the latter because they are providing the ‘gift of life’ – the bride – whose fertility will ensure the continued existence of the wife-taker’s lineage.

The wife-takers are obliged to give bridewealth, which traditionally consists of horses, mamuli pendants, and chains of plaited metal wire. The payment of bridewealth secures the incorporation of the wife and her offspring into the husband’s clan (Forth 1981, 368). The wife-givers must make a counter-prestation, the size of which is determined by the size of the negotiated bridewealth – it is believed that the two prestations should be in proportion otherwise the marriage will not prosper (Forth 1981, 362). The counter-prestation mostly comprises textiles, both male and female, but also includes orange anahida beads, ivory armbands, and a woman's knife (Forth 1981, 359 and 361). The most valuable textiles for the counter-prestation are the hinggi kombu and the lau pahikung, the lau pahikung hiamba being the most prestigious of all.

The exchanges follow a fixed sequence determined by negotiation. Payment of the bridewealth may begin long before the marriage takes place and may not be finalised until after the marriage. However the counter-prestation only takes place once the bride is delivered (Adams 1969, 49).

Return to Top

Halenda Pahikung

A halenda is a long narrow cloth, worn draped over the shoulder. It is wider than the man’s tiara headcloth. In Indonesia such textiles are generically known as selendang. However the selendang plays no part in traditional East Sumba costume, for either women or men. As Nieuwenkamp discovered during his visit of 1918, the women wear only one garment – a sarong or lau (1923, 309). You will never see a woman in East Sumba wearing a shoulder cloth and a man will only wear a folded hinggi blanket over his shoulder, a hinggi paduku.

Yet today both halenda pahikung and tiara pahikung are made in significant numbers, primarily for sale to visiting tourists and to merchants for onward shipment to retailers in Bali.

Simple chemically-dyed halenda at a workshop on the main Waingapu-Melolo highway

Better quality halenda being offered to guests at Pau during our Textile Tour

Cheap, chemically-dyed halenda pahikung hiamba on display at Parai Yawang, Rindi

Cheap synthetically-dyed halendas on sale in Bali

In 1994 Jill Forshee visited a workshop located between Melolo and Pau, which specialised in producing commercial pahikung for the Balinese market. It was run by Sing Ha, a mixed-race Chinese-Sumbanese entrepreneur who employed 25 weavers (1996, 208-210). To appeal to foreign tourists, some of its fabrics were composed of strips of warp ikat with borders or central panels woven in pahikung, contained a myriad of motifs and embellishments. Some were even made of multiple strips of warp ikat and pahikung. Such non-traditional commercial textiles were ridiculed by the local nobility, as well as by master pahikung weavers like the cousins Tamu Rambu Pakki and Tamu Rambu Tokung from Pau.

Forshee also encountered an elderly woman who lived close to Pau who was producing a steady stream of simple chemically-dyed black-and-white ‘uniform, market-quality halenda’ which were sold to a variety of agents on the island (1996, 205). Some were later tailored into shoulder bags and clothing for the Bali tourist market.

A few years later a dealer called Julius H. Prawira of Sumba Art, Plaza Adorama, Kemang, South Jakarta, whose company has been trading since 1996, began commissioning high-end pahikung from local weavers to be sold to upmarket dealers on Bali (Tenun: Handwoven Textiles of Indonesia, 2011).

Although Sumba warp ikat has been extensively plagiarised by workshops using ABTM looms at Troso, near Jepara, Central Java, they have so far avoided pahikung, probably because of the technical challenges involved. This was not an obstacle for the sister of Sing Ha, who with her husband opened the Sumba Primitive ikat shop on Kuta Beach on Bali in 1993. As a proficient pahikung weaver she began to produce a few mixed ikat and pahikung textiles for the local tourist market (Forshee 1996, 299). Today a few commercial pahikung textiles are now being produced by Rotinese weavers at the Ina Ndao workshop in Kupang. Some pahikung is even being woven on Lombok to be used as a fashion product, some for the outer covering of stiletto shoes (Tribal Signature, Kerebokan, Bali).

The production of so many textiles for the tourist rather than the domestic market raises the question of when halenda pahikung were originally introduced and for what purpose. Were they simply a commercial development or did they evolve from textiles that were made for local use?

It is not easy to answer this question. What is clear is that high quality halenda pahikung have been produced for the Sumba nobility from at least the mid-twentieth century onwards.

One woman who specialised in weaving some of the finest halenda pahikung was Rambu Ngana Harakay, who was born in Kabaru, about 2km from Pau, in the 1950s. She informed us that she produced such textiles for three reasons:

- firstly because her family had a tradition of designing large and dramatic pahikung motifs, so there was a desire to make their textiles wider than those normally used as items of clothing, such as the lau pahikung tubeskirt.

- secondly as heirloom gifts for her children, and

- thirdly for sale to the Sumbanese nobility and other important local individuals as well as for specialist collectors.

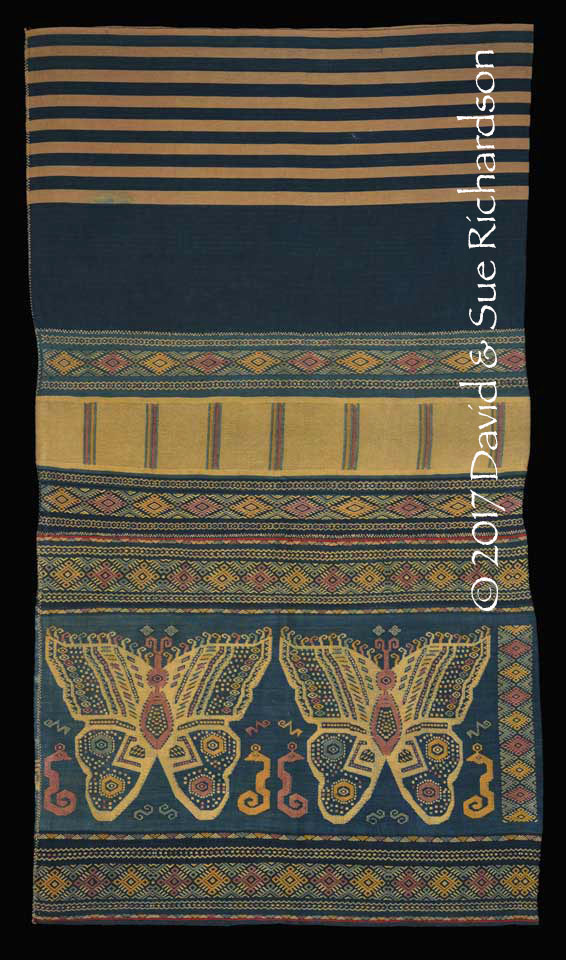

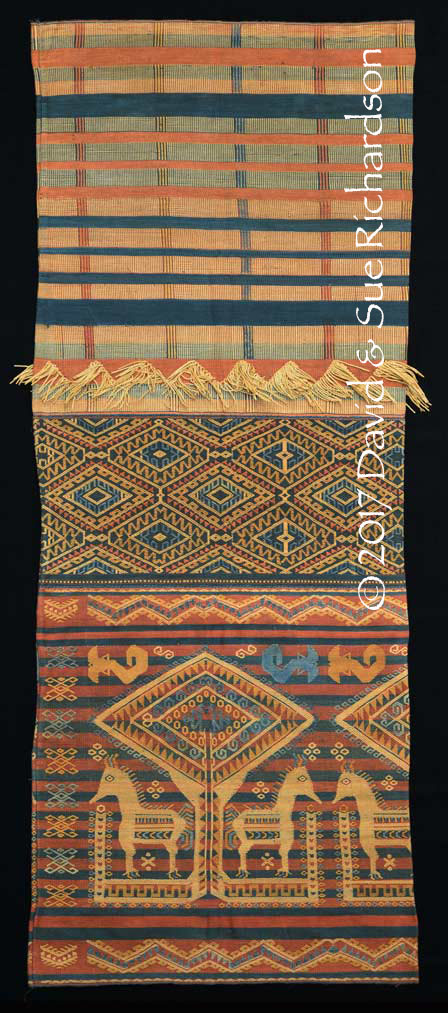

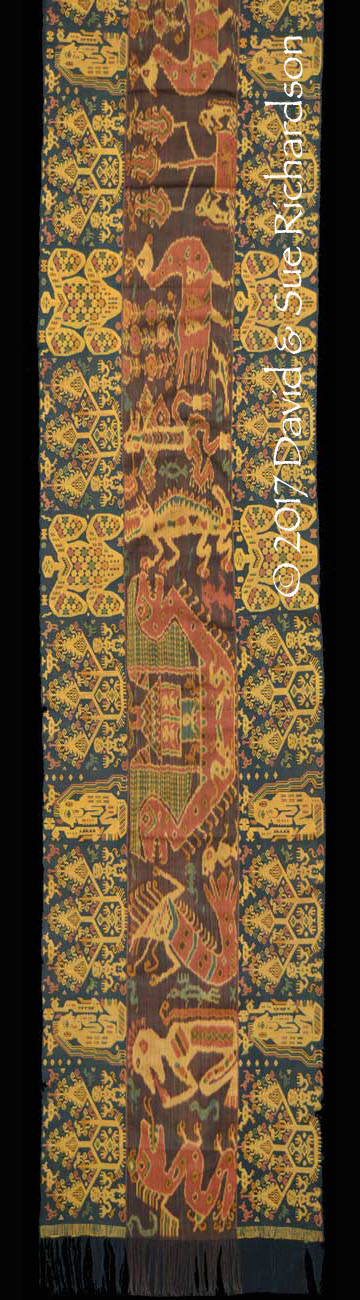

A halenda pahikung woven by Rambu Ngana Harakay in 1973. Size: 194cm by 60cm.

Richardson Collection.

A halenda pahikung hiamba woven by Rambu Ngana Harakay in 1973. Size: 164cm by 58cm.

Richardson Collection.

The princesses and cousins Tamu Rambu Pakki and Tamu Rambu Tokung, two specialist pahikung weavers who live and work together in Pau, were weaving high quality halenda pahikung in the mid-1990s (Forshee 1996, 198). Some, but not all, of these would have been sold to local merchants. An example of their work is illustrated in the book based on Forshee’s earlier 1996 Ph. D. thesis (Forshee 2001, plate 10).

The highest status halenda pahikung in our collection dates from around 1960 and was clearly produced for local use. It is possible such cloths were used ceremonially as a substitute for an Indian patola. They may have fulfilled the role of a nobleman’s shroud, being paraded around the tomb just prior to his burial.

A high-status halenda pahikung hiamba wuti kau, estimated to have been made around 1960. The ikat is from the Kambera region and the pahikung comes from the vicinity of Pau. Size: 288cm by 69cm. Richardson Collection.

Return to Top

Tiara Pahikung

A man’s head sash or turban is known in the Kambera region as a tiara. It is frequently transliterated as tera (Wielenga 1902, 321; Adams 1966, 49; Forth 1981, 16). The term also refers to a length of fine woven material as opposed to, say, barkcloth. Such sashes are always wrapped anti-clockwise as seen from above. The custom was to arrange the tiara so that one end was left pointing upwards on the left hand side. Tiara are usually only worn for ceremonial situations in combination with a hinggi, and can be made from a wide range of materials, including plain coloured cotton, batik, warp ikat and pahikung.

When a man dies and his corpse is ceremonially dressed, his headdress is wound in a clockwise direction with the upstanding end positioned on the right hand side, following the inversion rule 'move to the left' (Forth 1980, 172).

The traditional women’s head cloth, the tiara tamali, is rarely worn today. The word tamali means veil.

Return to Top

Ruhu Banggi Pahikung

A ruhu bànggi is a torso wrapper, originally made as a substitute for armour to protect a warrior from injury. It was kept in place with a liku ruhu bànggi belt composed of two or three strands of plied bast fibre sheathed at each end with strips of plaited rattan. In the Kambera language, ruhu means band, bànggi means loins, while rohu means to hug. Wielenga confusingly translated ruhu bànggi as a loincloth (1909, 153). The cloth is not wound neatly around the waist like a roll of cloth but is bunched up before it is wound to create a bulky mass of cloth around the waist and upper loins.

The term ruhu bànggi is also applied to the internal pair of horizontal rafters placed in the middle of each of the four sides of both the peak and the lower section of the roof of the traditional ancestral thatched house or uma marapu (Forth 1981, 30).

Other similar terms used to describe these wrappers include roesoe banggi (Roos 1872, 12; Ten Kate 1894, 567; Hangelbroek 1910, 46; Kruyt 1922, 524), roehoe bănggi (Wielenga 1909, 310), and rohubanggi (Warming and Gaworski 1981, ). The reason for these differences is because the terminology varied by region:

| Region | Name | Anglicised |

| Kambera | roehoe bânggi | ruhu bânggi |

| Tarimbang and Tabundung | rôhoe bânggi | rôhu bânggi |

| Kanatang, Napu and Palamedo | roehoe bânggoe | ruhu bânggu |

| Lewa | rosoe bânggi | rosu bânggi |

| Memboro | roesoe bânggi | rusu bânggi |

(Wielenga 1914, 38)

Samuel Roos, who became the first Dutch controleur of Sumba in 1866, provided one of the earliest descriptions of this textile. He called it a ‘roesoe banggi‘ and said that it was made from stiff, black-dyed (mud-dyed?) cotton, 4 or 5 vadem long (7½ to 9 metres), and was decorated with red and white stripes and terminal fringes (Roos 1872, 12). The textile was stiff and was wrapped around the body many times, with one end left hanging down. It took a long time to wrap, and was kept in place with one or more twisted ropes called a liku bànggi. In combat it protected the belly and thighs leaving the legs, knees and upper body exposed. Ruhu bànggi were woven by women and had the same value as an expensive horse. At that time they appear to have been uncommon objects, since Roos mentions that there were thousands who did not have the luxury of such a wrapper.

Another visitor in 1888 described the ‘roesoe bangi’ as being made of twill or black fabric, usually with many fringes (Vermast 1895, 47).

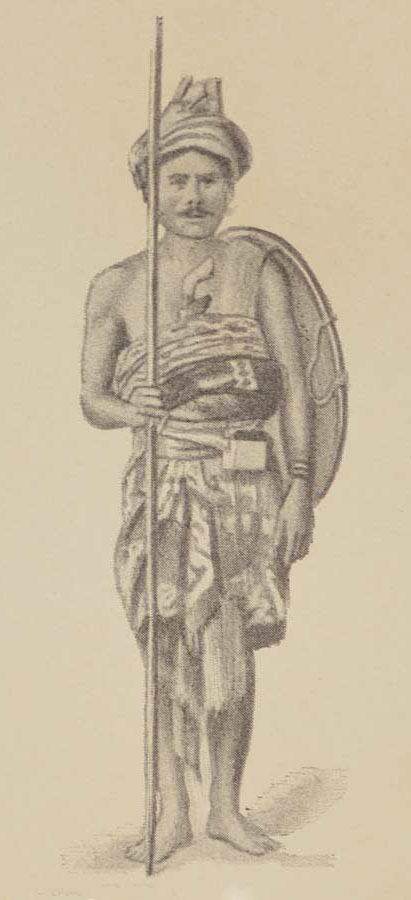

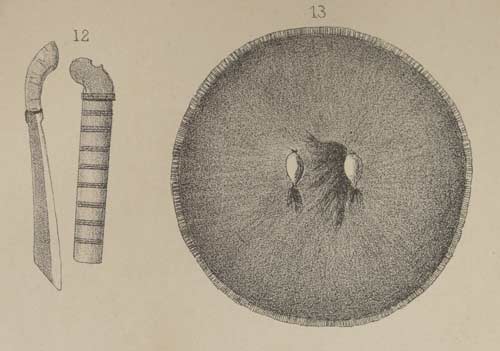

The ruhu bànggi clearly evolved as a crude form of armour for warriors engaged in interregional warfare or headhunting expeditions. The Dutch anthropologist Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate encountered a small band of armed warriors in the remote mountains of Masu in the early 1890s, led by their Raja - a man of vigorous martial stature (Kate 1894, 567). Their costume and armour was much as described by Roos. They were dressed in barkcloth kambala headdresses, katanga ngingi chin straps, singgi hip wrappers, roesoe banggi body wrappers held in place with likoe roesoe banggi rope belts, bracelets of copper or ivory, tonggal flat boxes for money and offerings, and the inseparable kaloembo or sirih bag. They were armed with short spears, kabéla knives, and round leather shields.

A Sumbanese warrior and details of his knife and shield

(Ten Kate 1894, plates 10 and 12)

Previously Ten Kate had acquired a blue coloured ruhu bànggi from Hambapraing in Kanatang (Kate 1894, 555).

An example in the collection of the Museum of the Batavian Society was made of stiff cotton dyed with dark blue indigo (Norman 1880, 163). Apparently ruhu bànggi were never worn undyed. The associated liku rohu bànggi fastening was black and smooth, having been dyed with roasted old coconut, pig fat and the bark of the wunga tree. It was usual to use two or even three of these strands around the belly, normally slightly higher for comfort when sitting on horseback.

Jasper and Pirngadie described a classical ruhu bànggi similar to one collected by the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen in 1909. The black and white ground was decorated with continuous weft bands, colourfully patterned with geometric diamond and hook motifs. The warp ends were sometimes woven into long ribbons and some examples were decorated with beads (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 291).

A 6½m-long traditional ruhu bànggi described as a ‘loincloth’, woven from indigo-dyed hand-spun cotton and collected in 1909

(Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Rotterdam, Creative Commons)

Different ruhu bànggi varied considerably in length. As already mentioned, in 1872 Roos published dimensions of 7 ½ to 9 metres. Albert Colfs estimated the length of such a wrapper in Monboro in 1880 to be 6 to 7 brasses long (about 9 to 11 metres), while the missionary Wielenga quoted much shorter dimensions for the ruhu bànggi, indicating that it was 3 to 4 metres long (Vorderman 1888, 127; Wielenga 1909, 310). Hangelbroek confirmed that it took a long time to wrap the ruhu bànggi and make it firm before supporting it with the two or three strands of the liku ruhu bànggi (Hangelbroek 1910, 46-47). Although Roos had suggested that the ruhu bànggi was uncommon, Hangelbroek noted that there was no restriction on who could wear one.

In addition to its physical protection, the rohu bànggi was considered to give its wearer a degree of supernatural protection. Perhaps this provided the motivation to transform the simple indigo, mud-dyed or warp-striped textile into a more decorative item. In the 1970s Warming and Gaworski were shown a ruhu bànggi woven over a century earlier by the grandmother of the late Raja of Tabundung. Measuring 7 metres long and 75cm wide it had been woven in warp ikat with tapestry weave end-bands, decorated in the centre with the red, white and blue stripes of the Dutch flag and elsewhere with an ikatted bird motif (1981, 79). The late Umbu Baba Hunggu wore the cloth before he went into battle and believed that it gave him extraordinary strength.

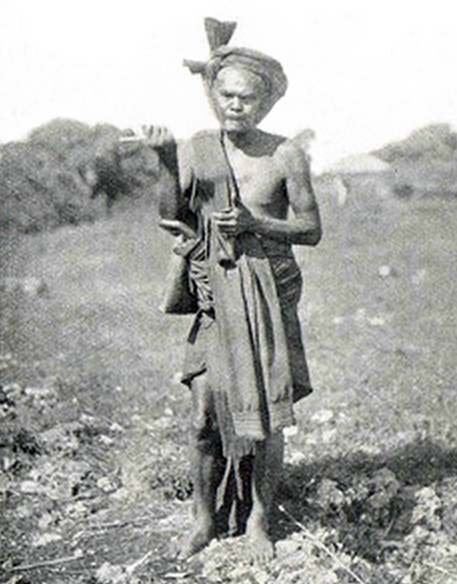

The heads of the domains of Masu and Karera photographed by G. P. Rouffaer in 1910

University of Leiden

Such a military chief was known as a kaboran - a brave, courageous and fearsome warrior who was the leader of a war party or head hunting expedition. The word kaborang or kaborangu means brave, valiant or vicious (Wielenga 1909, 207). Jacqueline Vel defined a kaborangu as a great, courageous person feared for his criminal inclinations, invulnerability, anger, magical skills, cruelty, power, or courage (Vel 2008, 123).

Samuel Roos encountered such a kaboran on horseback close to Karita in southwest East Sumba (Roos 1872, 107). He was the son of the local Raja and was leading a group of 42 armed men who, unlike him, were on foot. There were other names for such a leader. One was a moni mbani or valiant brave - whose status could vary from the Raja himself, to a leading noble, a commoner or even a slave retainer (Kruyt 1922, 558). Another was a kabana-mbani or angry man. Roughly translated the word mbani means anger, daring, threatening or rage (Kuipers 1998, 47-48). Such powerful individuals were the subjects of various colonial reports, since many fiercely resisted Dutch rule.

To ensure his invulnerability, the kaboran was protected not only by his ruhu bànggi but also the amuletic contents of his rectangular tongalu storage box (which was fastened to his liku ruhu bànggi belt) and his shield, which was embellished with shells that supposedly made it impenetrable (Adams 1969, 155; van Hout 2006, 814).

A group of Sumbanese who appear to have substituted hinggis for ruhu banggi. No provenance.

Kruyt also found that the ruhu bànggi was used to wrap the corpse of the deceased in Lakoka, in the western part of East Sumba (1922, 524). The body was first wrapped in the ruhu bànggi, before being covered with many blankets. A scarf was wrapped around the head, keeping the face uncovered. As in Kambera, the knees were pulled up and tied to the body and the arms were crossed. Kruyt mentioned that the ruhu bànggi were old cloths, no longer found on Sumba - suggesting that by 1920 the garment was no longer being woven. Support for this comes from Nooteboom, who thought that Sumba fashions had changed in recent decades since he had not seen the ‘roesoe bangi’ described by Roos and Wielenga (Nooteboom 1938, 90). Possibly the use of this armour, which was only worn by the living for going into battle or for attending high level ceremonies, declined following the brutal ‘pacification’ of the island between 1906 and 1912, during which the Dutch attempted to suppress the level of inter-regional conflict. This may be why it is hard to find any historical photographs of Sumbanese men dressed in this garment.

Sadly there are very few historical reports about the use of the ruhu bànggi for clothing the dead. Regarding the wrapping procedure used in Kambera, Kruyt simply noted that the body was wrapped in cloths, sometimes very costly ones, and the wealthier the person, the greater the number of cloths used (1922, 521).

Umbu Dikki Dongga dressed in a kambala headdress and a pair of hinggis (Wielenga 1928)

One prominent kabana-mbani was Umbu Dikki Dongga, a ruthless and very wealthy leader who lived at Janggamangu, just east of Waingapu (Kuipers 1998, 47). He is just the type of chieftain who would have most probably been buried dressed in a ruhu bànggi. However after his death in the 1920s, his biographer Douwe Wielenga frustratingly only tells us that his body was wrapped in ‘all kinds of cloths and beautiful garments until it became formless’ (Wielenga 1928, 170).

The custom for dealing with the corpse of a man in Rindi was more recently documented by Gregory Forth (1981, 171). It was dressed in the man’s regular loincloth while his waist was bound with a ruhu bànggi, securing by a rattan girdle. The body was covered with a hinggi kombu and a second similar textile was added as a shoulder cloth. Georges Breguet has more recently reported from the same location that the corpse of a prince was wrapped with a short ruhu bànggi only three-meters-long, held in place by a rattan belt (Breguet 2006, 214).

In some cases the ruhu bànggi was part of the costume of one or more of the male papanggang in attendance at the funeral of a noble. Unfortunately we cannot find any historical references relating to this issue. Gregory Forth did not describe the papanggang’s costumes that he observed at the several funerals he attended in Rindi, simply noting that they approximately varied in relation to the papanggang’s rank (Forth 1981, 197). At the funeral ceremony of Tamu Rambu Yuliana in Rindi in 2003, the papanggang wore full-length ruhu bànggi measuring up to 12-metres-long (Breguet 2006, 232).

There is no firm evidence to say whether ruhu bànggi pahikung are traditional textiles or a relatively recent innovation. It has been suggested that modern ikat-decorated ruhu bànggi hiamba are primarily woven for the tourist market (Geirnaert 1989, 76). From our experience this is not the case – few tourists have any interest in a textile that has such limited practical or decorative use in a Western home. These cloths are primarily woven for the local market, to be used for wrapping a male corpse or for dressing the papanggang at the funeral ceremony of a noble.

Because a ruhu bànggi cannot be woven on the traditional Sumba loom, Danielle Geirnaert suggested that they might have been inspired by the introduction of Western looms by the Dutch at the turn of the 20th century. The Alat Tenun Bukan Mesin or ATBM flying-shuttle handloom was actually introduced in 1926. It had been developed by the Textielinrichting Bandung, established by the Dutch in 1921. Although almost 45,000 had been licenced across the Netherland East Indies by 1940/41, only 1,381 were operating on islands other than Java (van der Eng 2006, 23). It is likely that the majority of the latter were on Bali. We suspect that none ever reached Sumba. The production of a ruhu bànggi simply requires a modified loom to support the longer continuous warp, the warp and breast beams held apart by long bamboo side beams.

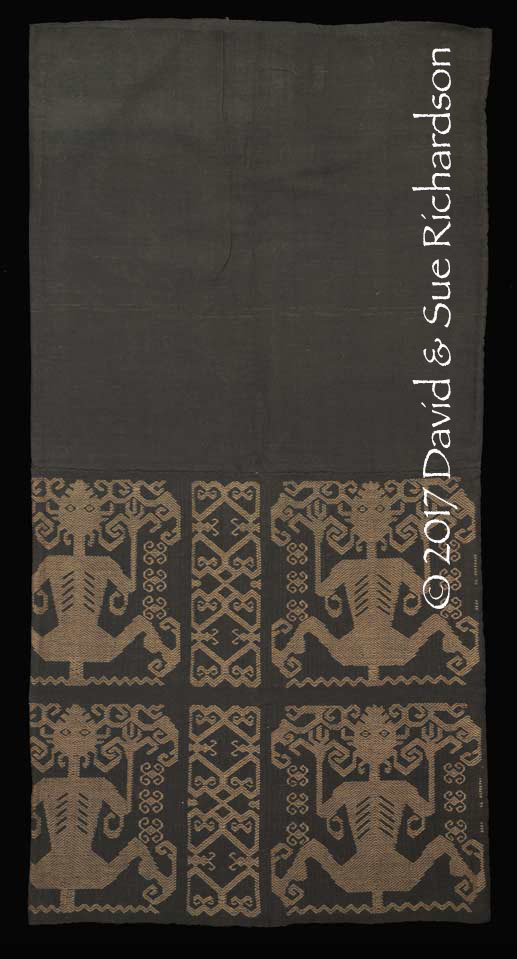

Two important centres for producing ruhu bànggi decorated with plain warp stripes, ikat, and shell work are Prailiu and Parai Yawang, while ruhu bànggi pahikung are made in villages in the vicinity of Pau, such as Uma Bara and Tambahak.

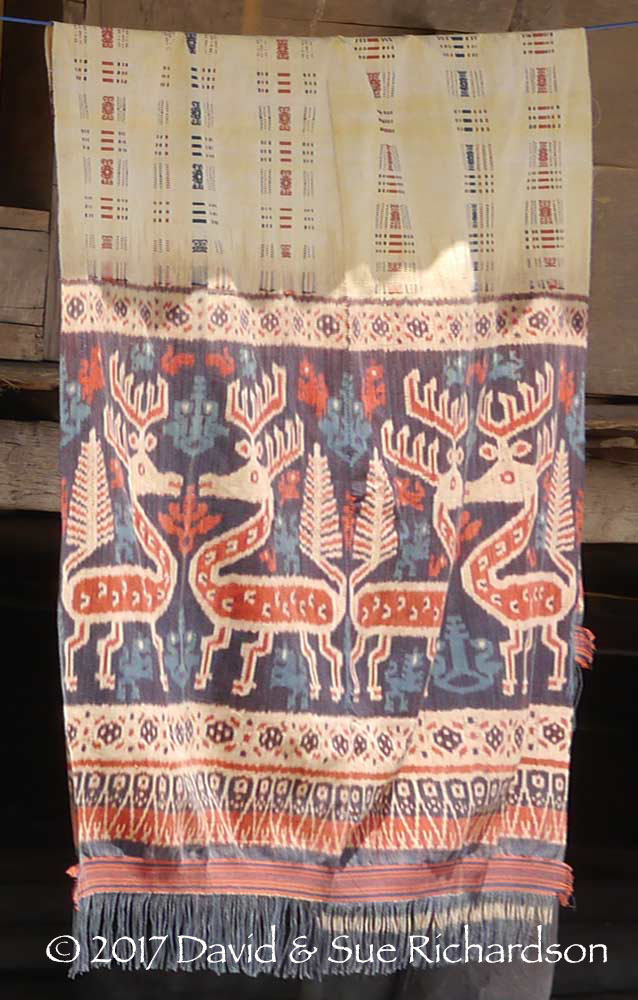

A ruhu bànggi pahikung in Parai Yawang, Rindi, approximately 12-metres long

A pair of dugongs on the ruhu banggi pahikung shown above

A roughly 10-metre-long ruhu banggi pahikung wuti kau in Parai Yawang, Rindi, decorated with shells and pahikung and said to be 50 years old.

We suspect that ruhu bànggi pahikung are traditional textiles that have probably been woven for at least a century or more, albeit on a small scale. As Warming and Gaworski discovered in Tabundung, highly prestigious ruhu bànggi hiamba were clearly being woven during the second half of the 19th century. As the demand for ruhu bànggi required for combat declined under the Dutch, their use became purely funereal and ceremonial, possibly leading to a greater emphasis on their decoration.

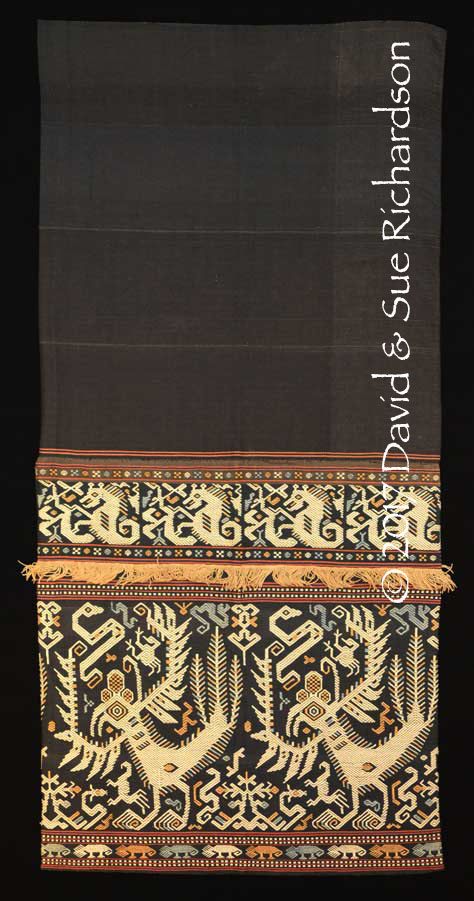

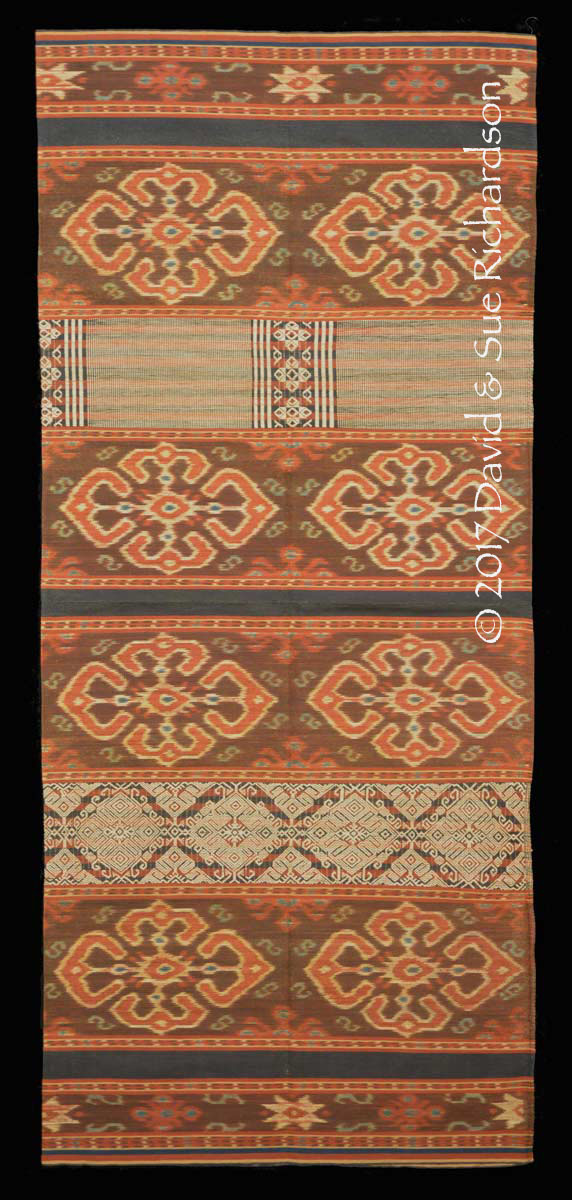

A 5.2-metre-long ruhu bànggi pahikung woven in Uma Bara. Richardson Collection.

Two of the most prestigious high-status ruhu banggi pahikung of all were woven by the royal princess Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja, a daughter of the Raja of Pau and later a wife of the Raja of Rindi. Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja was the third child of the second wife of Tamu Umbu Hiya Hama Taki II, the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. She subsequently became the third wife of Umbu Hapu Hamba Ndina, locally known as Umbu Kandunu ‘the one who wears the star’. He was the Raja of Rindi from 1932 until his death in 1960. Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja was born with the formal title Tamu Rambu Mirinai Ridja Pinggi Djawa, but was informally known as Tamu Rambu Mirinai Liaba. After having been widowed, she moved to Tambahak on the other side of the Melolo River.

Brought up in Pau, where she learnt to become a master of pahikung weaving, her move to Parai Yawang would have resulted in her also become highly proficient in binding and dyeing warp ikat. The ikatted sections incorporated into these two textiles was clearly bound and dyed in Parai Yawang, Rindi. Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja set up the ikat and pahikung continuous warps and programmed the pahikung design before weaving the complete ruhu bànggi on a modified horizontal loom.

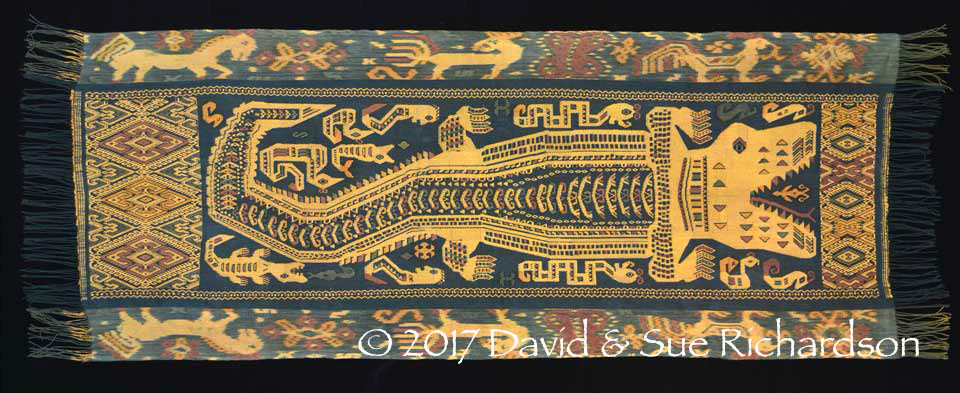

One half of a prestigious ruhu banggi pahikung hiamba, made by Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja in Parai Yawang at some time between 1932 and 1960. Richardson Collection.

At just over 5-metres in length, these sumptuous textiles were made as a non-identical pair, one retained by the royal family at Pau, the other gifted to a noble family at Ngalu, close to Kaliuda in Mangili. Clearly such important heirlooms were produced for exclusive use by the royal family, not for sale to foreigners. They were most likely intended to be used at a senior nobleman’s funeral, either as a wrap or shroud for the corpse, or as a substitute for a patola that was intended to be paraded around the grave during the burial ceremony.

Return to Top

Hinggi Pahikung

In the past, hinggi woven with a white central section were reserved for the nobility. They are called a hinggi bara padua - literaly hinggi white middle. In the finest examples, the central white section was subtely decorated with pahikung, combining the techniques of warp ikat and supplementary warp in one garment.

According to Adams, hinggi pahikung were rare and were reserved for the leader of the royal maramba or noble caste (Adams 1969, 87 and 91). She found that examples from ‘Prailiu, Kambera, Uma Bara and Melolo’ were characterised by:

a wide white central section in which figures are woven in white, flanked on either end by bands of colourful ikat decoration.

Whilst this is partially true, there is another less common category of hinggi pahikung that lack any central white section. Some, if not all, of these appear to originate from the nobility of Parai Yawang in Rindi and Pau in neighbouring Umalulu. Jill Forshee, who conducted research in East Sumba from 1994 until 1996, mentioned an older woman called ‘Rambu Ina Matua’ from Parai Yawang (which she disguised as Parai Mutu) who as a teenager could produce technically precise combinations of warp ikat and pahikung (Forshee 1996, 166).

Hinggi kombu rara, which are only dyed with morinda (rara means red), are a speciality of the Rindi region. The hinggi kombu rara pahikung shown below was bound and dyed by the princess Tamu Rambu Maramba Bokul (formally titled Tamu Rambu Kahi Timba) from Uma Kudu, one of the best ikat-producing houses in Parai Yawang, Rindi. Tamu Rambu Maramba Bokul is one of the granddaughters of Tamu Umbu Hiya Hama Taki II, who was the Raja of Pau from 1893 until 1932. She later married into the royal family of Rindi, so is a master of both warp ikat and pahikung. Her sister is Tamu Rambu Tokung, the pahikung specialist from Pau. The hinggi has been woven with alternating lateral bands of warp ikat and pahikung.

A hinggi kombu rara pahikung designed and bound by Tamu Rambu Maramba Bokul in Parai Yawang, Rindi, but woven by one of her servants. Richardson Collection.

A more elaborate hinggi kombu pahikung has been made from identical panels of warp ikat that have been woven with discontinuous pahikung bands along their selvages.

A hinggi kombu pahikung, most likely made by a female member of either the Rindi or Umalulu royal families. Richardson Collection.

Yet another style has much wider bands of continuous pahikung woven along each selvage, somewhat like a wide halenda pahikung hiamba.

A hinggi kaworu pahikung dyed with indigo and kayu kuning with integral pahikung side panels. Woven in Pau using ikat produced in Kaliuda, Pahunga Lodu. Private Collection.

In recent decades Prailiu has ceased to be a major ikat-producing centre and has increasingly focused on selling textiles and jewellery from other regions of East Sumba. The only major remaining centre for making high status hinggi kombu pahikung with the white centre panel is Parai Yawang in Rindi. The weaving of such blankets has been and remains a particular speciality of the Ana Mburungu royal family.

A hinggi kombu pahikung on display outside of Uma Wara in Parai Yawang

The following two hinggi pahikung were produced in Parai Yawang by the royal princesses Tamu Rambu Ana Motur and Tamu Rambu Yuliana. These weavers were regarded by their peers as the two finest ikat designers and producers in East Sumba.

Tamu Rambu Ana Motur was a princess from the ruling family of Tabundung who married Umbu Makapaki, the head of the noble Uma Andung household in Parai Yawang and a cousin of the Raja of Rindi, Tamu Umbu Hapu Hamba Ndima. She died in Parai Yawang in 2016. Her simple, uncluttered design has been dyed in two shades of indigo.

A hinggi kaworu pahikung from the collection of the late Tamu Rambu Ana Motur. Richardson Collection

Tamu Rambu Yuliana was the daughter of Raja Tamu Umbu Hapu Hamba Ndina by his first wife. In 1992 she became the unofficial and highly influential queen of Rindi, a postion she held until her death in Parai Yawang in 2003 at the age of 70.

A hinggi kombu pahikung from the collection of Tamu Rambu Yuliana, the former queen of Rindi. Richardson Collection

Each half of the white centre panel has been woven with five narrow strips of discontinuous pahikung. The mismatch in the indigo tone and motif size suggests that there was some delay in weaving the second panel

Unlike other regions of eastern Indonesia, the production of an ikat blanket in East Sumba is a cooperative venture, requiring the involvement of a variety of specialists. Normally the key producer is the person who creates the design and binds the warps. However other specialists may be involved in dyeing the indigo, unbinding, dyeing the morinda, weaving the two halves, weaving the kabakil and twisting the fringes. A noblewoman may obtain assistance from her female relatives, as well as from the family slaves.

In the case of the above hinggi kombu pahikung, the design was created by Tamu Rambu Yuliana, who was also responsible for binding the yarns. The ahu uamang katiakar wihhi motif (wild dog from the forest with one raised front leg) was Tamu Rambu Yuliana’s exclusive design and could only be tied by her or by someone else under her authority. However she requested a specialist in pahikung to weave it for her - her relative, Tamu Rambu Njanji, a princess from Pau.

A similar hinggi kombu pahikung produced in Uma Penji, Parai Yawang, the home of Tamu Rambu Yuliana. Produced roughly 30 years ago under her supervision. Richardson Collection.

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank some of the many people who have given up their time to share with us their knowlege about pahikung weaving.

In the former domain of Pau, we have made numerous regular visits to the royal cousins and master pahikung weavers, Tamu Rambu Pakki and Tamu Rambu Tokung, who have explained the intricacies of the process in great detail.

David interviewing Tamu Rambu Pakki and Tamu Rambu Tokung at their home in kampong Watu Hadangu, adjacent to Uma Bara

In the former domain of Rindi we would like to thank the

Return to Top

Bibliography

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1969. System and Meaning in East Sumba Textile Design: A Study in Traditional Indonesian Art, Cultural Report Series 16, Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Adams, Marie Jeanne; Forshee, Jill; Djajasoebrata, Alit; and Hansen, Linda, 1999. Decorative Arts of Sumba, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam.

Bolland, Rita, 1956. 'Weaving a Sumba Woman’s Skirt', in Royal Tropical Institute Bulletin, vol. 119, pp. 49–56, Amsterdam.

Bolland, Rita, 1979. Demonstration of Three Looms, Irene Emery Roundtable on Museum Textiles: 1977 Proceedings, pp. 69-70, The Textile Museum, Washington D.C.

Breguet, George, 2006. The Life and Death of Tamu Rambu Yuliana: Princess of Sumba, Arts & Cultures, no. 7, pp. 200–233, Musée Barbier-Mueller, Genève.

Breguet, George, 2013. Three Lau Pahudu Skirts from Sumba: Ceremonial Dress or Currency?, Arts & Cultures, no. 14, pp. 116–129, Musée Barbier-Mueller, Genève.

Carol, Charles, 2004. Interpreting Social Change and Changing Production Through Examinations of Textiles of Xam Nuea and Surin, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 480.

Dammerman, Karel Willem, 1926. Een tocht naar Soemba, Natuurkundig Tijdshrift voor NederlandschIndisch, LXXXVI, reprinted by Indisch Comite uoor Wetenschappelijke Onderzoekingen, Batavia.

Emery, Irene, 2009. The Primary Structures of Fabrics: An Illustrated Classification, Thames and Hudson, London.

Ernawati, Wahyu, 2013. Gold jewellery from Sumba, in Living with Indonesian Art; the Fritz Liefkes Collection, KIT Publishers, Amsterdam.

Forshee, Jill Kathryn, 1996. Powerful Connections: Cloth, Identity and Global Links in East Sumba, Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Forshee, Jill, 2001. Between the Folds: stories of cloth, lives, and travels from Sumba, University of Hawai‘i Press, Hawai’i.

Forth, Gregory L., 1981. Rindi: an Ethnographic Study of a Traditional Domain in Eastern Sumba, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Gronovius, D. J. van Dungen, 1855. Beschrijving van het eiland Soemba of Sandelhout, Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indïe, vol. 1, pp. 277-312

Guelton, Marie-Hélène, 2004. ‘Use of the Pahudu String Model, Lau Pahudu Weaving from East Sumba, Indonesia’, in Through the Thread of Time, Southeast Asian Textiles: The James H. W. Thompson Foundation Symposium Papers, Jane Puranananda (ed.), pp. 47–65, The James H. W. Thompson Foundation, Bangkok.

Hamilton, Roy W., and Forshee, Jill, 2010. Weavers' Stories: Rambu Pakki and Rambu Tokung, video, The Fowler Museum, UCLA, Los Angeles.

Hangelbroek, H., 1910. Soemba: Land en Volk, G. F. Hummelen,

Hout, Itie van, 2001. Lau Pahudu: Women’s Skirts from East Sumba, HALI, vol. 115, pp. 99-105.

Hout, Itie van, 2006. Dressed in prayers: religious implications of bird motifs on Indonesian textiles from Borneo, Sumba and Timor, Les Messagers divins: Aspects esthétiques et symboliques des oiseaux en Asie du Sud-Est, Connaissances et Savoirs, Paris and Bangkok.

Howard, Michael, 2008a. A World Between the Warps: Southeast Asia’s Supplementary Warp Textiles, White Lotus Press, Bangkok.

Howard, Michael, 2008b. Supplementary Warp Patterned Textiles of the Cham in Vietnam, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 243.

Kate, Herman Frederik Carel ten, 1894. Verslag eener reis in de Timorgroep en Polynésie, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. 11, pp. 195-246, 333-90, 541-638, 659-70 and 765-823, E. J. Brill, Amsterdam.

Kruyt, Albert C. 1921. Verslag van eene reis over het eiland Soemba, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2nd series, vol. 38, pp. 513-553.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1923. Iets over Soemba en de Soembaweefsels, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 7, issue 10, pp. 295-313.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1927. Eenige Voorbeelden van het Ornament op de Weefsels van Soemba, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 11, issue 9, pp. 259-288.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. K. H. de, 1890. Eenige Mededeelingen over Soemba, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIII, pp. 565-595.

Vermast, Alfons M., 1895. Remonte-ankoop op het eiland Soemba (Sandelhout-eiland) in 1888, H. M. van Dorp, Batavia.

Wielenga, D. K., 1914. Vergelijkende Woordenlijst der verschillende dialecten op het eiland Soemba en eenige Soembaneesche Spreekwijzen, Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, vol. 61, pp. 1-68, A. C. Nix, Bandung.

Wielenga, D. K., 1949. De zending op Soemba, Hoenderloo, The Hague.

Witcamp, H., 1913. Een verkenningstocht over het eiland Soemba, II, IV, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, second series, 29, pp. 8-27, 619-637.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was first published on 26th March 2017.