Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Cham of Cambodia

Cham Women's Costume

Resist-Dyeing Techniques

Cham Kiet

Small Kiet Ceremonial Cloths

Large Kiet Cloths

Simple Pictorial Kiet Cloths

Complex Pictorial Kiet Cloths

Modern Kiet Cloths

Bibliography

The Cham of Cambodia

Numbering just over 300,000, the minority Cham comprise less than two per cent of the total population of the Kingdom of Cambodia. They live in compact villages mainly centred within specific regions (Collins 2008, 61):

- Kampong Cham Province

- along the middle reaches of the Mekong River north east of Phnom Penh

- north and south of Phnom Penh in Kandal Province and

- along the south bank of the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang Province.

The ethnolinguistic groups of Cambodia

SIL International, Dallas, Texas

Excluding a few small Cham groups who live in the highlands of Vietnam, the lowland Cham are divided into the Eastern Cham and the Western Cham. The Eastern Cham live mainly in Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan provinces, located between Saigon and Nha Trang. The Western Cham are divided between those living in Cambodia, and those living near the Cambodian border in Vietnam. The Western Cham in Vietnam live mainly in An Giang and Tay Ninh provinces (Howard 2008).

The Cham are of Malay-Polynesian origin. Their Austronesian ancestors settled on the coast of Vietnam from an earlier homeland, probably Borneo or possibly the Malay Archipelago, at some time prior to 600 BCE. One of their earliest sites is at Sa Huynh in northern South Vietnam. Most speak Cham, which belongs to the Austronesian language family, and are devout Muslims.

Although the Cham-speaking Cham make up the majority of the Muslim population of Cambodia, another distinct Cham community is sometimes referred to as the Chvea. They mainly speak Khmer and may have originated from Java. Both groups belong to the Shafi branch of Sunni Islam. There are also smaller groups of Bangladeshi and Pakistani descendants. However the term Cham is generally used to indicate all Muslims in Cambodia regardless of the above-mentioned ethnicities (Sabeone 2017).

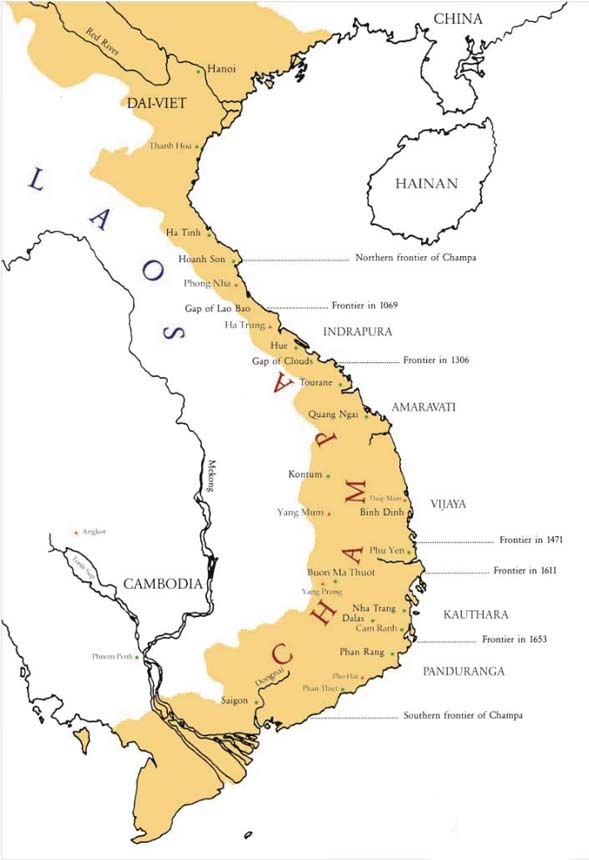

The original Cham are the descendants of the ancient Kingdom of Champa, which once ruled much of south-eastern Indochina. It was mentioned in second-century Chinese texts, and in the eighth century its territories stretched from the Ngang Pass in the north to the Donnai River basin in the south, probably organised as a confederate state (Hubert 2005, 18). Located on the Maritime Silk Route, the Cham controlled the trade in spices and silk between China, India, the Indonesian islands, and the Abbasid Empire in Bagdad.

Map of eighth-century Champa

In the tenth century the Khmer Empire and the Kingdom of Champa were the two dominant powers in mainland Southeast Asia.

The Cham appear to have adopted Islam in the early fifteenth century following the establishment of the important proselytising Muslim centres of northern Acheh on Sumatra and nearby Malacca. As the Khmer elite moved away from the imperial capital of Angkor in the fifteenth century, the Vietnamese increasingly expanded south from their historical base in Tonkin and Annam, gradually conquering the Champa principalities.

Over several centuries various waves of immigrants abandoned Champa and moved into Cambodia, settling along the banks of the Mekong River and around Tonle Sap Lake. It seems a few retained their former Hindu beliefs.

A Cham temple in the forest of Cambodia

Photographed by Henry Baudesson at some time prior to 1919

In 1970 General Lon Nol mounted a coup d’état against Prince Norodom Sihanouk that ushered in a decade of bitter political struggle, his inept regime leading to the rise of the Khmer Rouge. During this period all commercial activities, including silk production and trade, came to a halt.

After the fall of Phnom Penh to Pol Pot in April 1975, the Khmer Rouge set out to Khmerise minority non-Khmer groups such as the Cham, forcing them to adopt Khmer-style housing, dress and food. Their language was outlawed, Islam was prohibited, mosques and Qurans were destroyed and people were forced to eat pork. Whole Cham communities were broken up and dispersed into the countryside. Some Cham rebelled against the regime, resulting in a brutal crackdown during which whole villages were exterminated. It is estimated that over one third of the Cham population died under the brutal Khmer Rouge regime.

A Cham mosque close to the Vietnam border

Return to Top

Cham Women's Costume

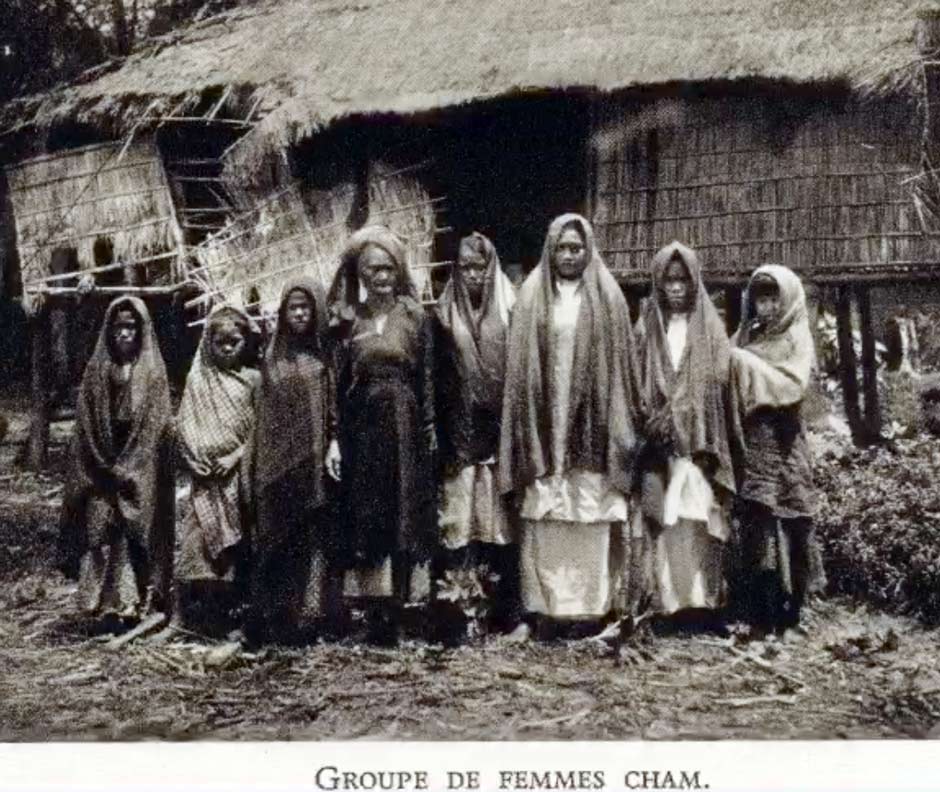

The only early description of women’s costume relates to the Eastern Cham. While staying in a Cham community located between Phantiet and Phanrang in Vietnam in 1919, Captain Henry Baudesson noted that:

The women wear a large piece of cloth wrapped round to form a rude skirt. Gay colours are somewhat restricted, white and white striped with red and green being the most popular. For bodice they have a clinging dark-green tunic open at the throat.Their taste in jewellery is remarkably restrained. The rich wear silver or gold buttons in their ears. Of the poorer classes some confine their personal embellishment to copper nails and others wear a plait made of coloured threads which falls over their shoulders. We sometimes noticed bracelets on the wrists of some of the girls. This ornament serves to remind its wearer of the temporary vow of chastity which she has taken to guard her against some danger or cure an illness.

Others again wear a necklace of large amber beads from which hangs the Tamrak, a kind of amulet which wards off the powers of evil. This indispensable talisman consists of a small cylinder of lead on which a priest has traced mystic characters with a sharp-pointed instrument.

Eastern Cham women returning from the market at Barau on the train line halfway between Saigon and Nha Trang. Taken by the Swiss photographer Werner Bischof in 1952.

In Cambodia, Cham women’s attire is conservative and consists of a tight-fitting, long-sleeved, open neck tunic that reaches down to below the knees. Under this they wear a sarong, tied at the waist, today referred to as a batik (Whittaker 1973, 73). In the past these were home-woven, but since 1980 women have preferred to use imported Javanese batik (Fraser-Lu 1988, 133). This may be why Cham skirts became known as batik.

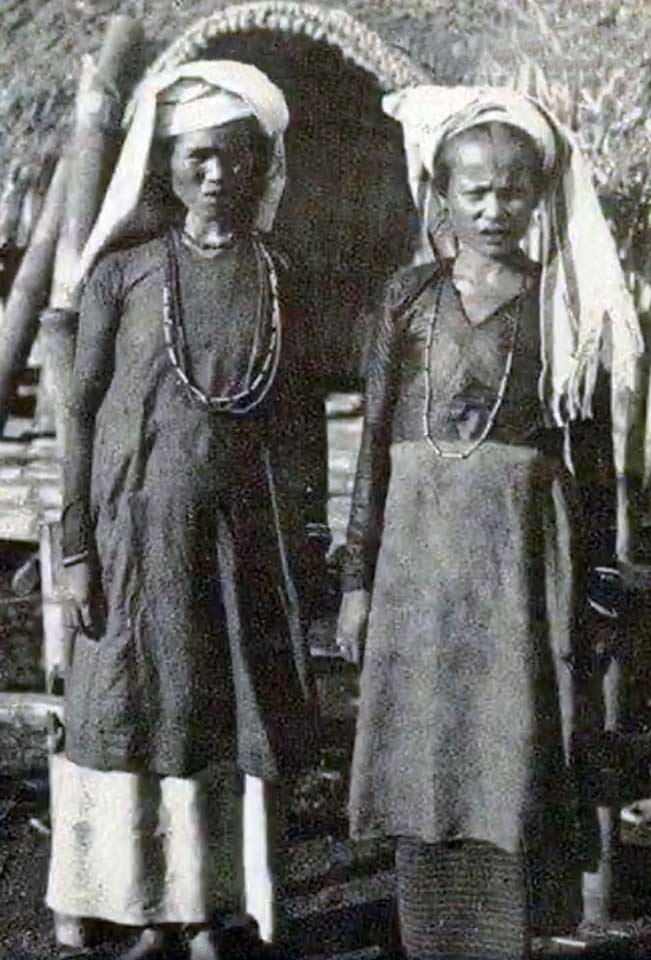

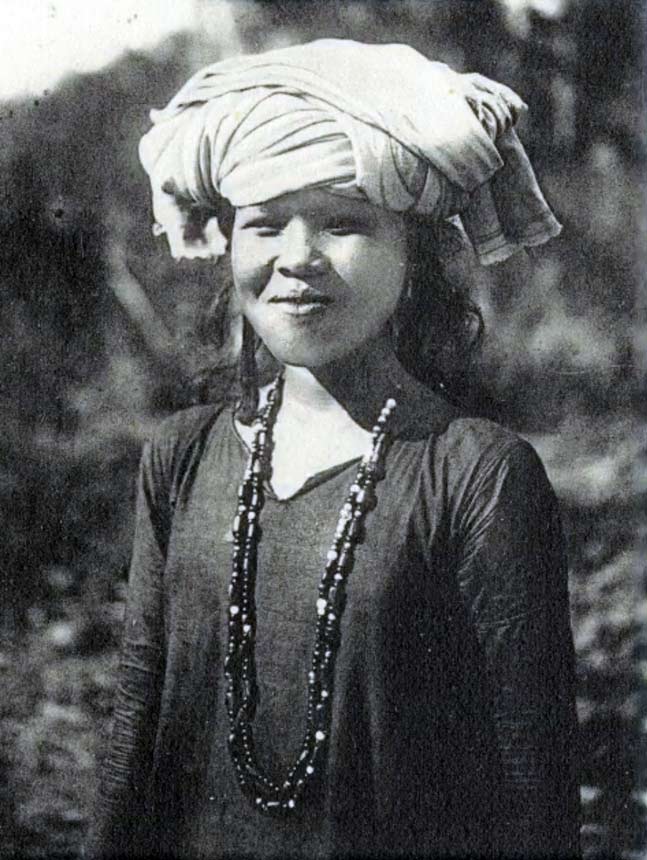

Unfortunately most of the few archive photographs of Cham women and their costume lack any information about the date or location. Nevertheless they illustrate the highly conservative nature of their dress and the various ways of wearing the head cloth.

A French postcard of a family of Cham women in Indochina

Above and below: Cham women wearing simple tunics and head cloths

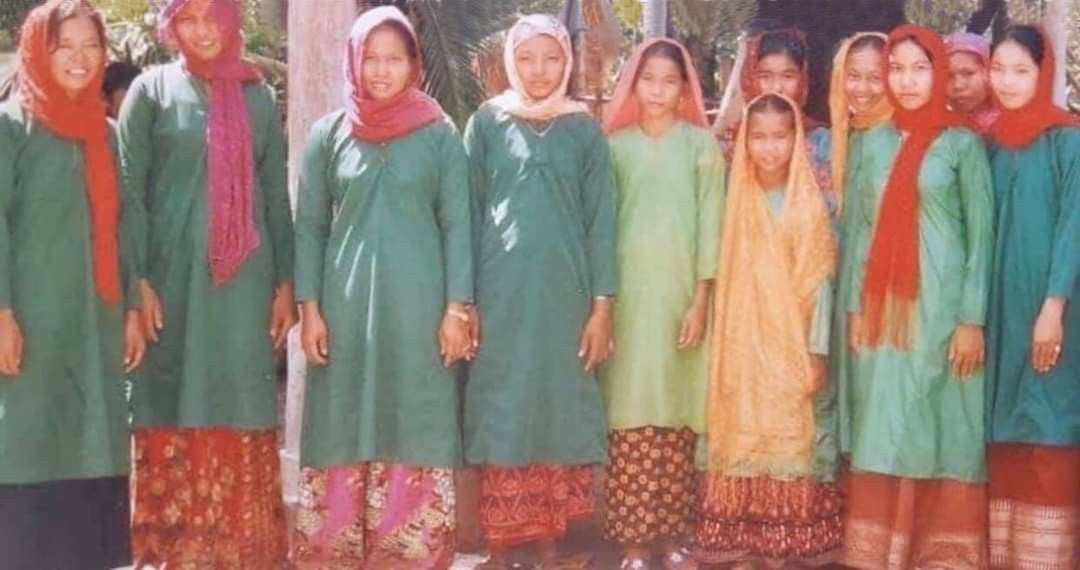

Cham women in Cambodia wearing plain green tunics over brightly patterned sarongs

A more recent image of young Cambodian Cham women threshing rice dressed in long tunics and head cloths

The Eastern Cham of Vietnam wear two types of tunic dresses, both of which cover the bust and have tight sleeves. The aw dwa baung is close-fitting and reaches the ankles, while the aw tah has a looser fit and reaches down to the knees (Thuy Hà 2016). For everyday work in the fields or at home women wear the simpler aw kauk (or aw kauh). For festivals, weddings or the important karoeh ceremony marking the passage of girls into womanhood, they wear the more elaborate aw xah.

A group of Eastern Cham women

For Cham Muslims the important karoeh ceremony marks the passage of a girl from infancy to puberty and usually takes place around the age of fifteen. From this moment onwards she is free to marry.

Unlike the Eastern Cham who weave textiles using a back-strap loom, the Western Cham use a Malay-type frame loom called a kay or ki, which they use to weave weft and warp ikat, although previously they wove supplementary weft and of course made kiet tie-dyed textiles (Howard 2008).

A Cham weaver at her frame loom in a village close to the Vietnamese border

Return to Top

Resist-Dyeing Techniques

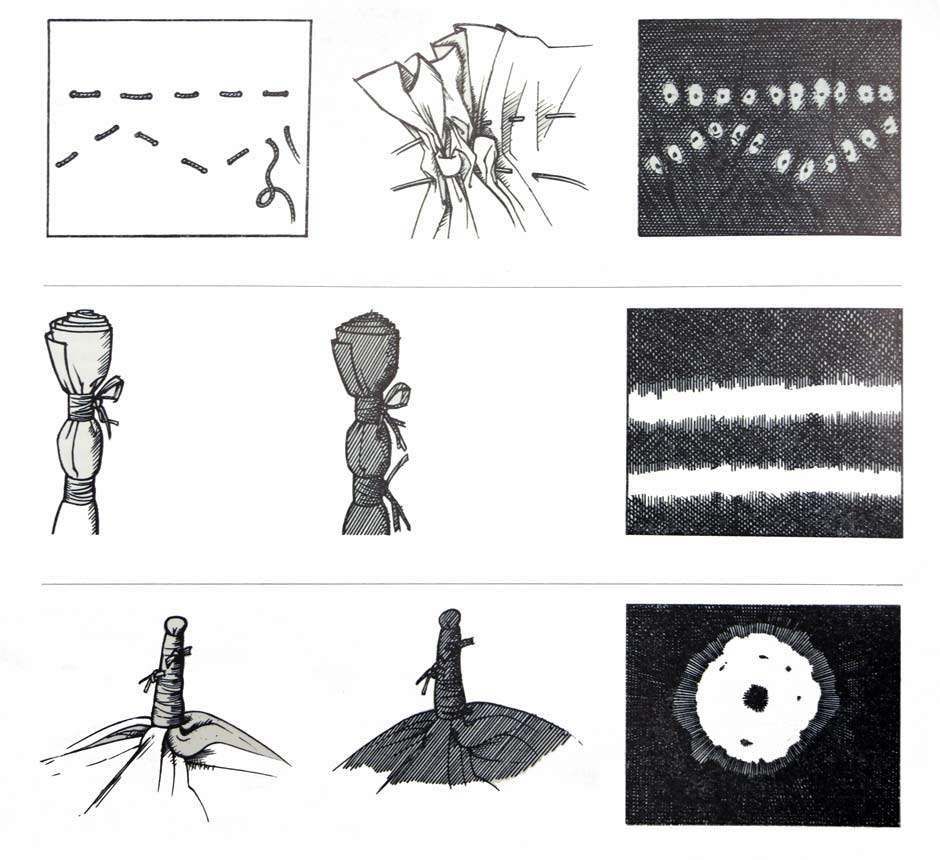

In his three-volume survey of resist-dyeing techniques, Alfred Bühler listed eight different methods of applying patterns by shielding areas of the textile or its component yarns from the dye:

- Fold resist – folding, pleating or creasing the textile.

- Stitch resist – inserting stitches and pulling and knotting them tightly. Known in Indonesia as tritik.

- Wrapping resist – wrapping parts of the rolled or folded textile with raffia, thread or ribbons.

- Binding resist – partially or fully tying the surface of the textile to create bobbles. Known in Indonesia as pelangi (meaning rainbow), often abbreviated in the West to plangi (The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts).

- Stencil resist – covering or clamping the textiles with a patterned template.

- Paste or wax resist – spraying, painting or brushing the textile with paste, mud or wax, which is removed after dyeing. Known in Indonesia as batik.

- Negative resist – pre-treating a textile with different mordants that produce different colours from the same dye or weaving the textile from different materials that take up the dye differentially.

- Yarn resist – binding the yarns with thread, tape, strips of dried palm leaf or plastic prior to weaving. Generally known as ikat.

The techniques of tritik, wrap resist and pelangi

(From Bühler volume 1 1972)

The pelangi and tritik techniques are widely spread around the globe. In the past they were especially used in North Africa, the Middle East and parts of Central Asia. Bühler has illustrated examples from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, Iran, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

In West Africa they have been used in the Gambia, Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin and Nigeria.

In the Indian subcontinent pelangi/tritik are called bandhana, meaning bound. They were especially popular in Rajasthan and among the Muslims of Gujarat and Sind Hindus. They are also found in Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Hyderabad, Bengal, and Tamilnadu, as well as in neighbouring Nepal.

Further east they have been used in Tibet, China, Japan, Cambodia, Kalimantan, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Java, Bali, Lombok and Savu. The Javanese call these techniques jumputan.

In Europe they were even used in Denmark, Sweden and Slovakia.

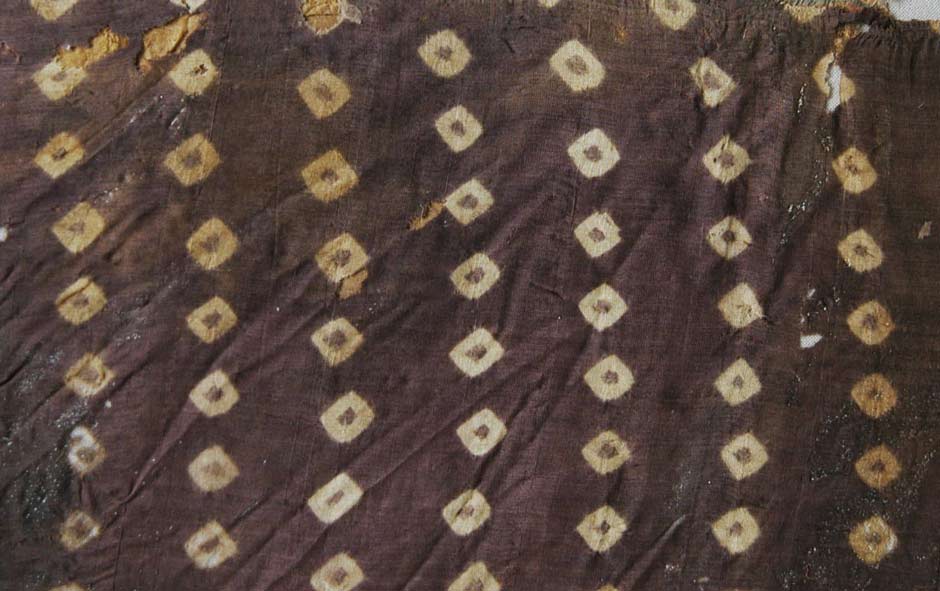

Such simple tie-dye techniques are clearly ancient. In China they were known as xie. However this term gradually became applied to all forms of resist-dye, including tie dye, clamp resist dye, wax resist dye and ash resist dye. According to Wang and Zhao (2017) the origin of tie-dyed silk in northwest China could date back to the West Jin dynasty (265-316 AD). It became more prevalent between the seventh and ninth centuries. Many examples of silk xie have been recovered from tombs in Tulufan in Chinese Xinjiang dating from the fourth to the eighth century. Stitching was the most widely used method in ancient China.

An example of purple silk xie (pelangi) from the tomb of a woman who died in 377 CE in Bijiatan, Huahai, Gansu Province.

It is not clear how the Cham acquired these resist-dye techniques. Warming and Gaworski have claimed that Muslim Arab and Indian traders brought them to the Malay Archipelago during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, along with the spread of Islam (1981, 114 and 122). Green also suggests that they are part of the Malay tradition (2003, 172). However Maxwell has suggested that over time they may have developed in Southeast Asia independently (1990, 321).

Return to Top

Cham Kiet

In the past the Cham used a combination of pelangi, tritik and batik to produce dramatically patterned cloths from hand-woven or machine-woven silk. They called these combined techniques kiet, a term that was also applied to the resulting textiles.

According to Gillian Green, in 1943 Alfred Bühler noted that:

In Cambodia their [kiet] manufacture is said to have been exclusively in the hands of inhabitants of Malayan descent (1943, 32).

However we cannot locate that comment in Bühler’s 1943 publication Materialien zur Kenntnis der Ikattechnik or in his 1942 paper on the ikat technique.

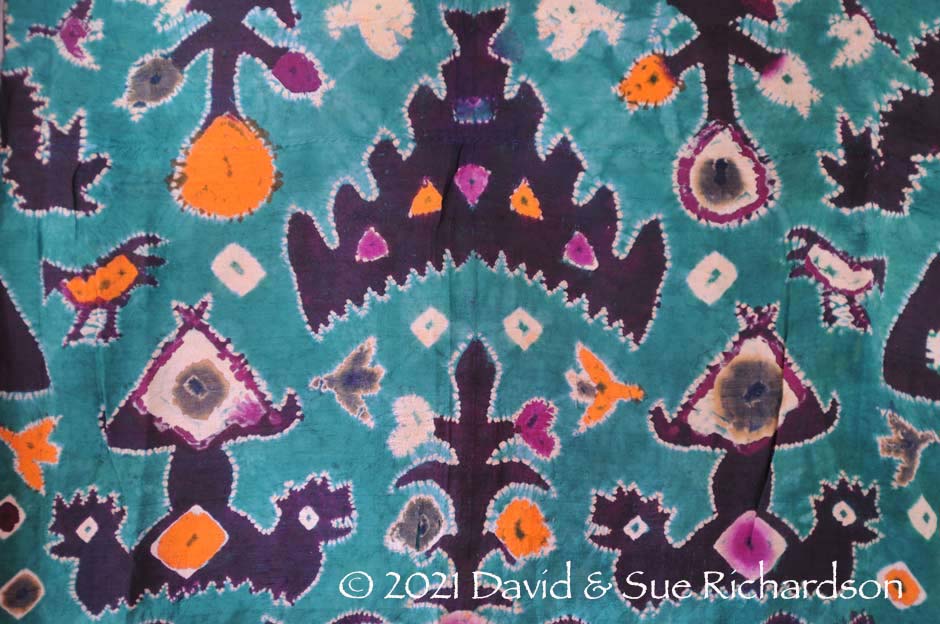

Detail from a Cambodian silk kiet

National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh

The rather loose Cambodian dictionary definition of the noun kiet is ‘a silk material dyed by the Cham method, i.e. by binding up different areas in turn so that they do not take up the colour’ (Jacob 1974, 31). The verb kiet means to ‘tighten, roll up, draw up’.

Kiet are sometimes referred to as tcharabok, a term that probably derives from the Khmer word craboc meaning the ‘scales of the nak’, the sacred serpent (Porée-Maspero 1964, 465, cited by Green 2003, 103). The origin of this name is clearly an expressive description of the cloth after the bindings have been cut which has the appearance of the rough skin of a reptile. Gillian Green has also used the term chabot (1997, 90).

The Khmer refer to the ikat technique as chawng kiet or chong kiet, meaning ‘tying strings’ (Green 2003, 310; Morimoto 2004).

Tragically the horrific civil war launched by the Marxist mass murderer Pol Pot in 1968 devastated the Cambodian silk weaving industry. The Khmer Rouge had a distorted vision of an agrarian utopia, and forced people out of the towns and cities into the countryside to work off the land. Business people, artisans and intellectuals were hunted down and killed by teenage soldiers (Ong 2003, 18).

According to the twisted mentality of the communists, silk was considered bourgeois. As a result mulberry trees were deliberately felled, and by 1970 the breeding of silkworms came to a halt. As already noted, the Khmers regarded the Islamic Cham as outsiders and targeted them brutally. Many Cham weavers were killed or fled the country. No silk was woven for the next quarter of a century.

Before the Khmer Rouge took power, Cambodia was producing an estimated 150,000 kilograms of silk per year. That number dropped to just 800 kilograms after years of political and civil unrest. It even became impossible to import foreign silk. Prior to 1975 the ethnic Chinese had dominated the Cambodian silk trade. Under the Khmer Rouge more than half of the ethnic Chinese community in Cambodia was murdered, especially middle-class Chinese business people and intellectuals (Dahles and Horst 2006, 64).

Because of this catastrophe, there is a scarcity of information about where and how kiet cloths were made and worn, and the extent to which they were made for sale to the Khmer population of Cambodia. It also means almost all surviving kiet dates from before 1968.

It is obvious that the small kiet cloths can only have been used as ceremonila covers, head cloths or kerchiefs. The larger cloths appear to have been used as turban-like head cloths (chnûet in Khmer), shawls or hip wrappers.

Return to Top

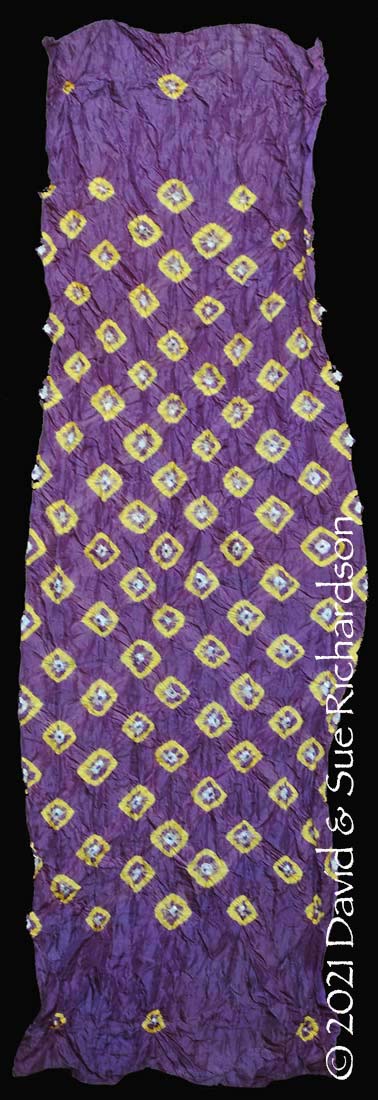

Small Kiet Ceremonial Cloths

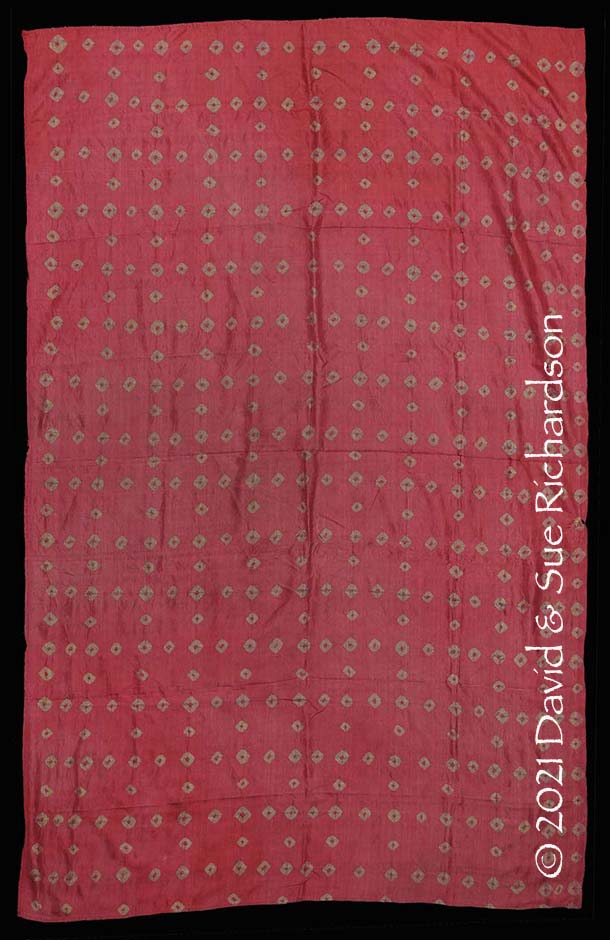

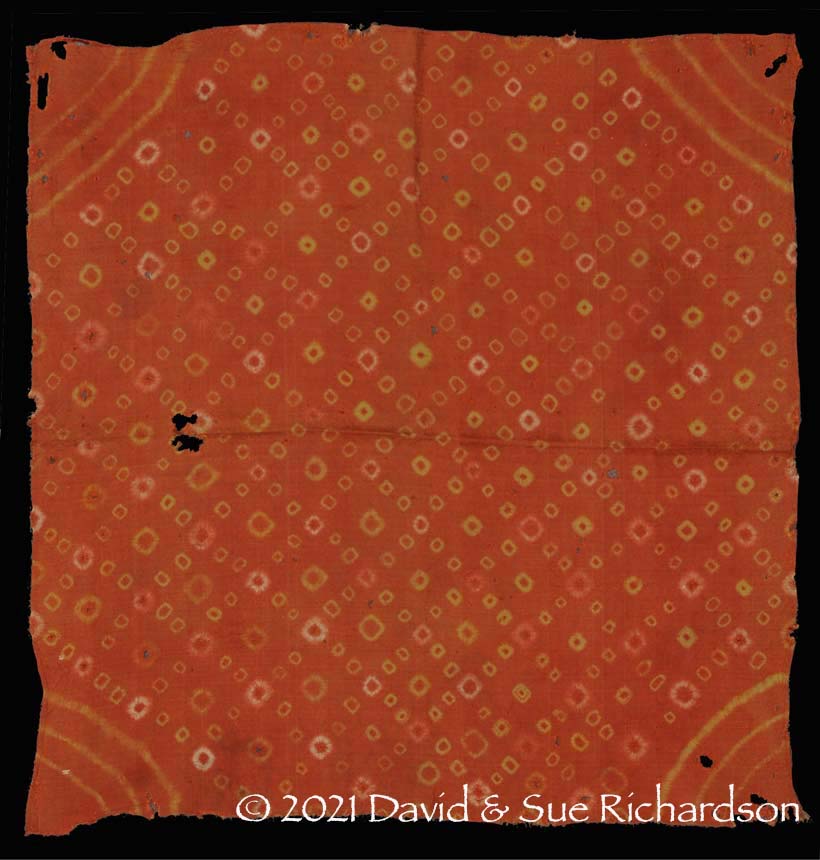

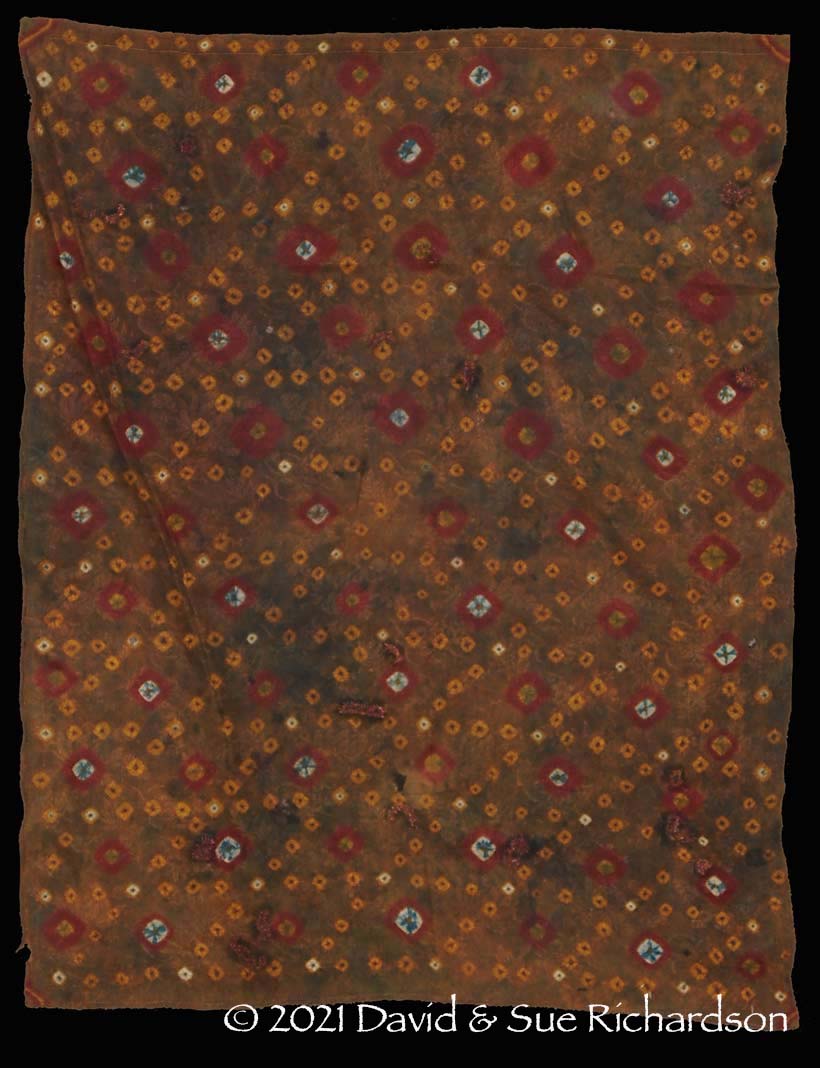

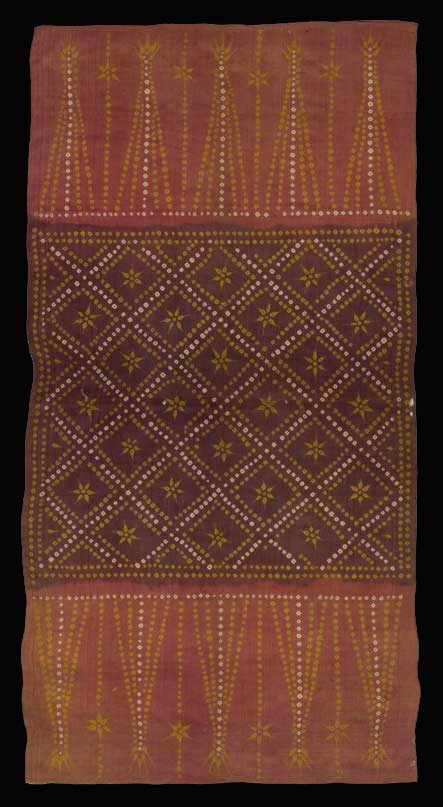

Small square-shaped silk kiet cloths are roughly 75cm wide, but other small rectangular cloths are about 100cm wide and 150cm long. They are made from machine-woven silk and show considerable signs of long-term wear, so appear to be of considerable age although not antique. We have no information of how they were originally used, but today they are mostly assumed to have been ceremonial cloths, for covering offerings for example.

A very simple kiet cloth, probably a fragment from a larger textile

Richardson Collection

The majority of these cloths are decorated with a simple rectangular or diagonal lattice of small pelangi circles or rectangles. These are achieved by using a pointed object to obtain a pinch of cloth and binding it with a strong thread and then, without breaking the thread, repeating the process over and over again. The cloths generally have two or three concentric quadrants in each corner. These are achieved by folding the cloth twice diagonally and binding the free corners with two or three larger separate ties. Sometimes small stones or seeds can be tied into the cloth to obtain a clearer more uniform shape to the ties. It is also possible to dip some of the ties in a third dye to obtain different coloured circles.

In some examples the silk has been initially dyed with a lighter colour before binding the small pinches and then immersing the cloth in a darker dye. In others, a few of the ties have been made before the first lighter colour is applied, while the rest are made before the final darker colour is applied. This means that some of the ties remain white, while the others are coloured.

Above and below: two small kiet cloths. Only small remnants of the corner decorations appear on the lower example, showing that it has been cut down.

Richardson Collection

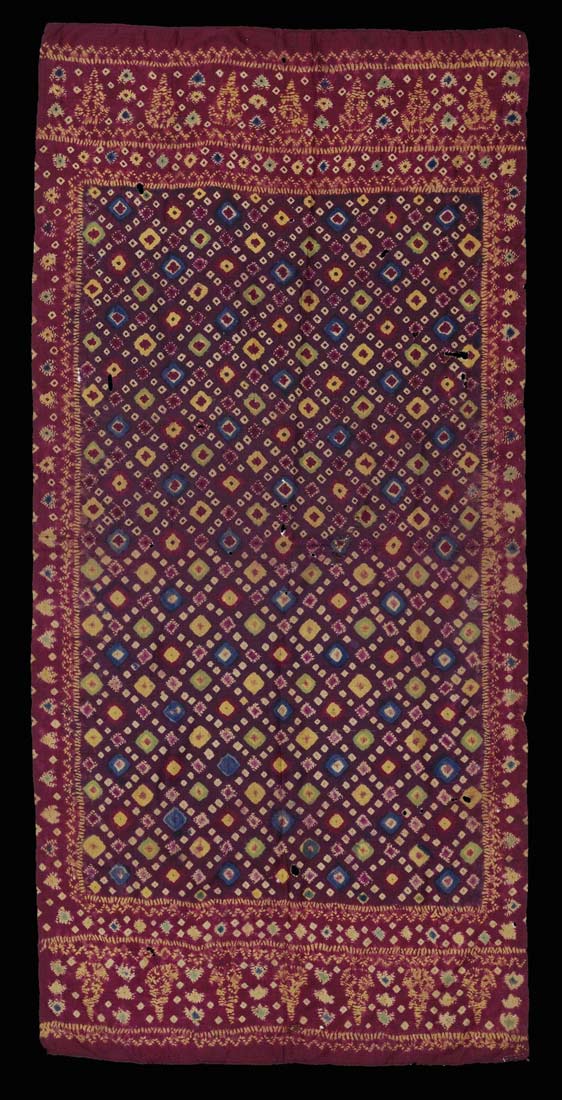

Above and below: two complete kiet head cloths

Richardson Collection

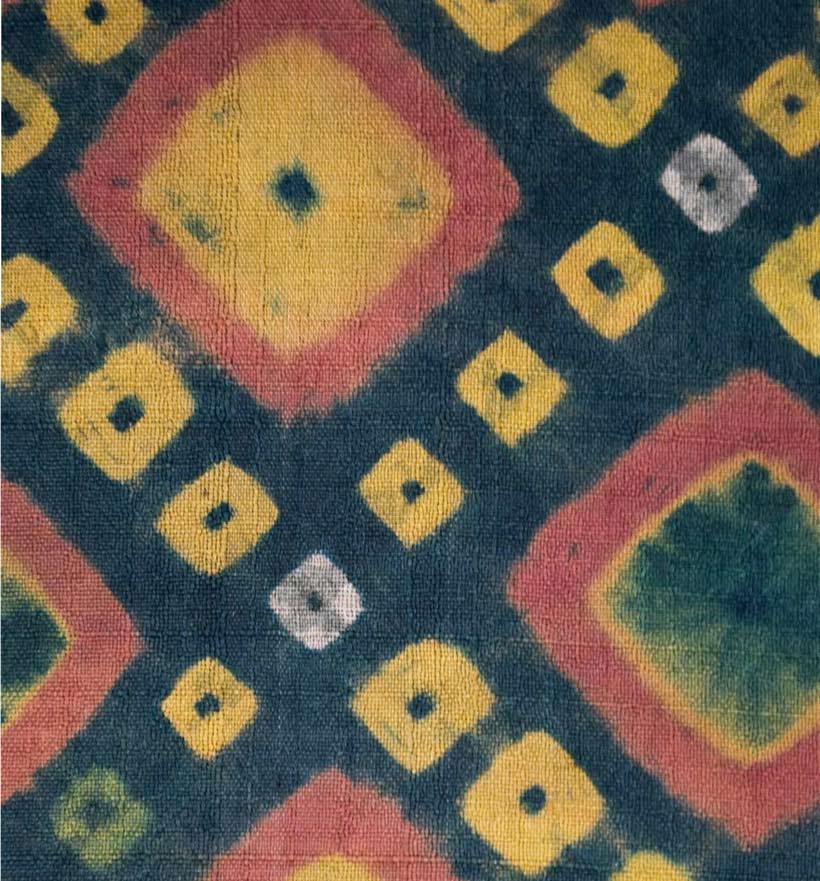

Some of the finest examples have been decorated with four different colours, one of which is usually the white of the undyed silk.

A four-colour kiet cloth. Private Collection

This detail of a four-coloured kiet headcloth shown below illustrates how the small spots at the intersections of the diamond lattice have been bound prior to the initial dyeing with yellow. All of the other small and large spots have been bound prior to the second dyeing with blue, some of the large spots being bound almost fully and others only partially so that the central area is exposed to the blue. Finally the outermost bindings of the large spots has been removed and the exposed sections have been painted with red dye, colouring the outer circumference of the spot orange.

Return to Top

Large Kiet Cloths

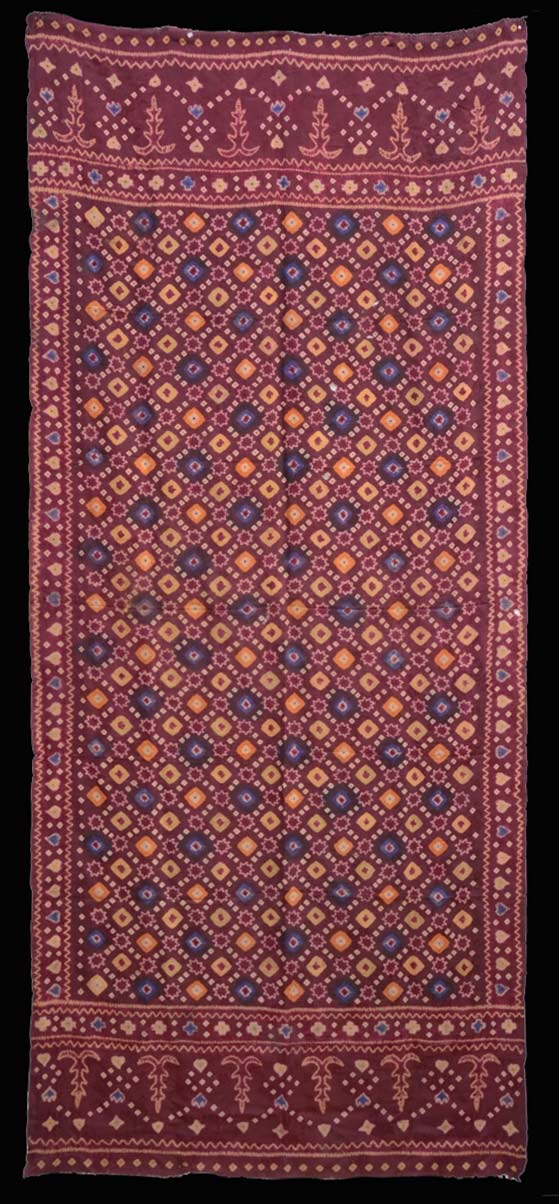

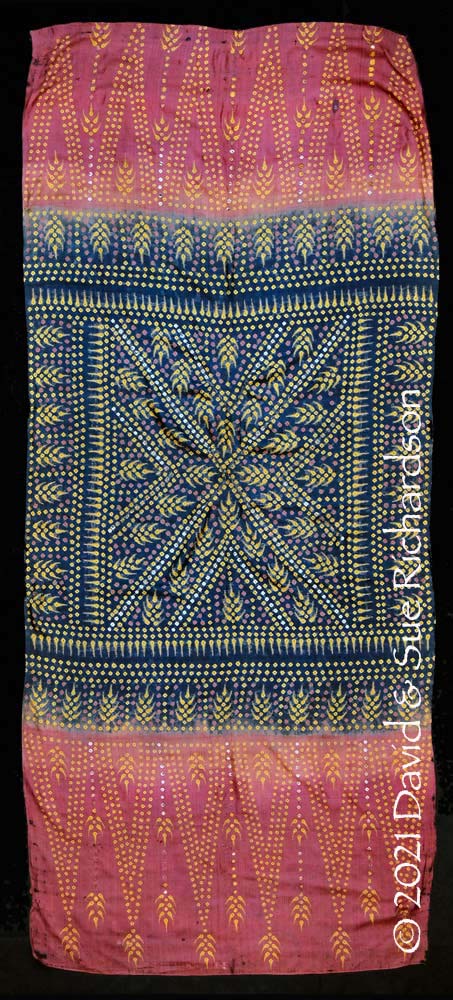

Some larger kiet cloths seem to have been used as Muslim head covers, and are around 75-90cm wide and 175cm long. They have a patola-like layout based around a rectangular central field filled with a diagonal lattice. This is completely surrounded by a narrow border and flanked by a pair of end panels containing a single row of outward-pointing tumpal-like triangles. The border surrounding the central field usually has a zigzag meander running around its inner side and, in some cases, its outer side as well.

The motifs in the lattice consist of small plangi diamonds and, sometimes, small flower heads or stars.

A large kiet in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London

A large kiet lattice cloth. Private Collection

These cloths are very similar to the prestigious kain pelangi made in the Sumatran cities of Jambi and Palembang (Kerlogue 2005, 136). In Palembang these were made by Malay artisans in the tie-dyeing quarter of Seseberang in Ulu on the southern side of the Musa River.

Return to Top

Simple Pictorial Kiet Cloths

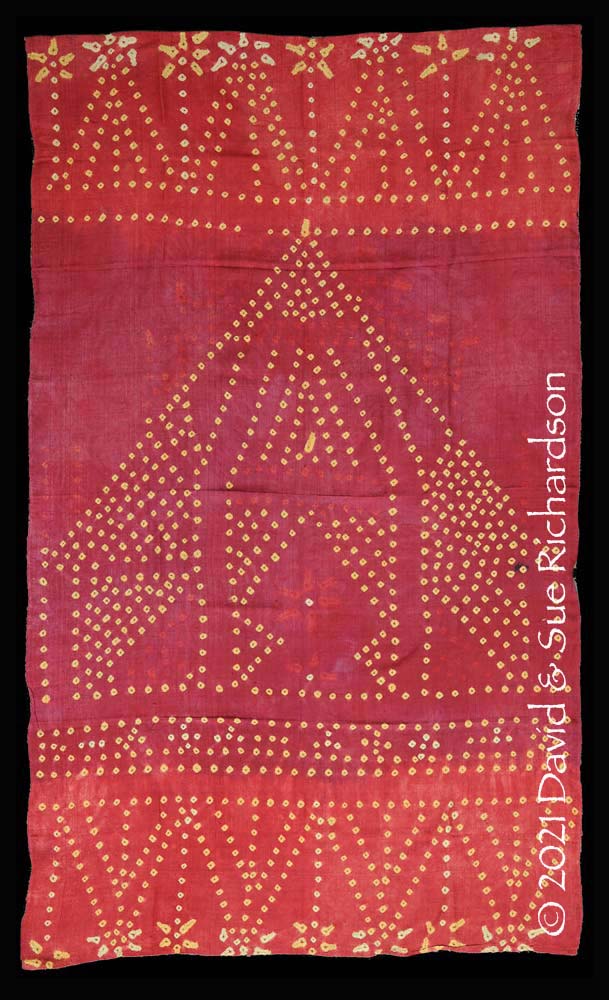

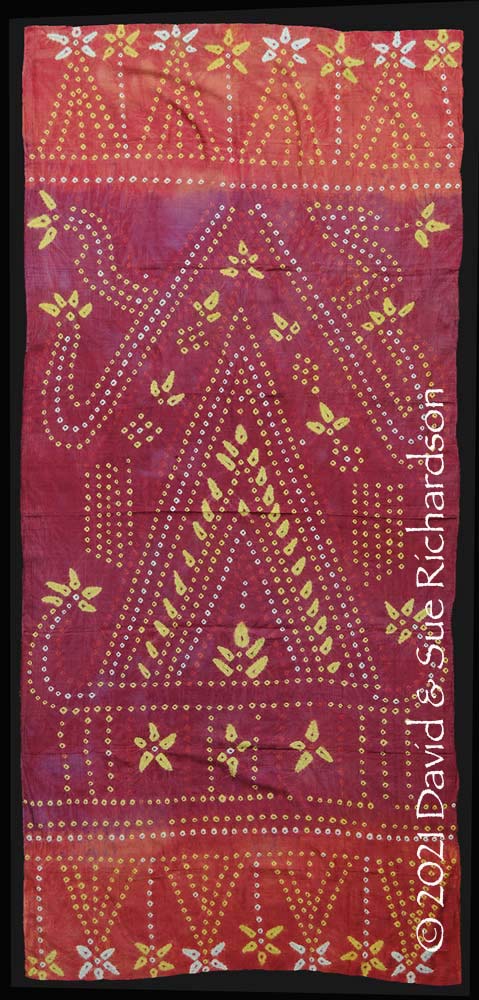

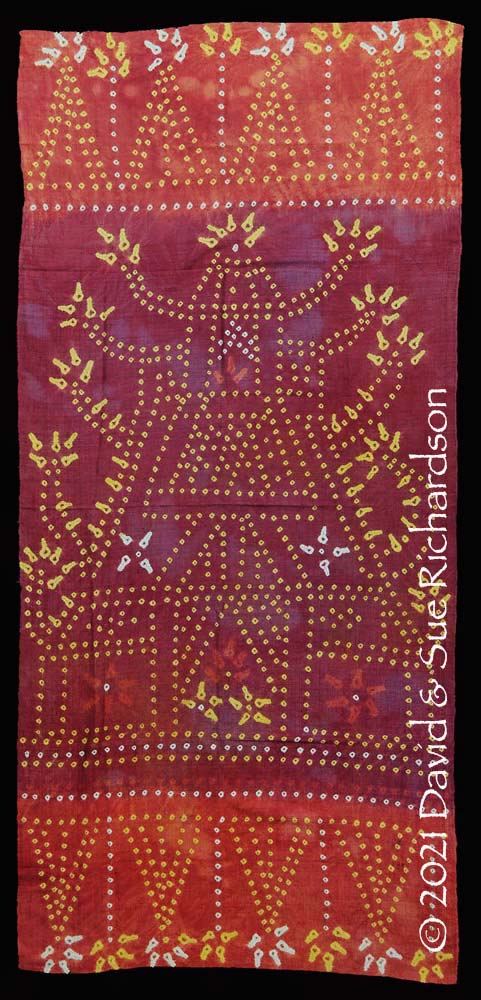

Simple pictorial silk kiet cloths have a basic layout with a large rectangular centre field flanked by matching rectangular end panels. The centre fields have a dark red, brown or black background, while the wide lighter red end panels are decorated with tumpal-like triangles. Here the pelangi designs are far less proscribed. Almost every example appears to have a unique free-style design.

A kiet in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

Given the conservative nature of their costume, these textiles do not appear to have been made for Cham use. A large number of these cloths appear to depict some of the traditional Khmer celebrations staged at the end of the rainy season, suggesting that they were produced commercially for the main Khmer market. Many depict pavilion-like structures that could be royal pavilions illuminated with candles, lanterns or electric lights. Others might include or depict firework displays.

A kiet depicting an illuminated house

Richardson Collection

A kiet depicting an illuminated pavilion and perhaps fireworks

Richardson Collection

A kiet depicting an elaborate illuminated pavilion

Richardson Collection

A kiet depicting heart-shaped figures and perhaps fireworks

Richardson Collection

A kiet possibly depicting fireworks

Richardson Collection

In most kiet of this type it appears that the red colour of the end panels is applied first and the centre panel is then zone dyed with the darker colour.

The uniform nature of these cloths suggests they were produced in a small local area, the location of which remains unknown.

Return to Top

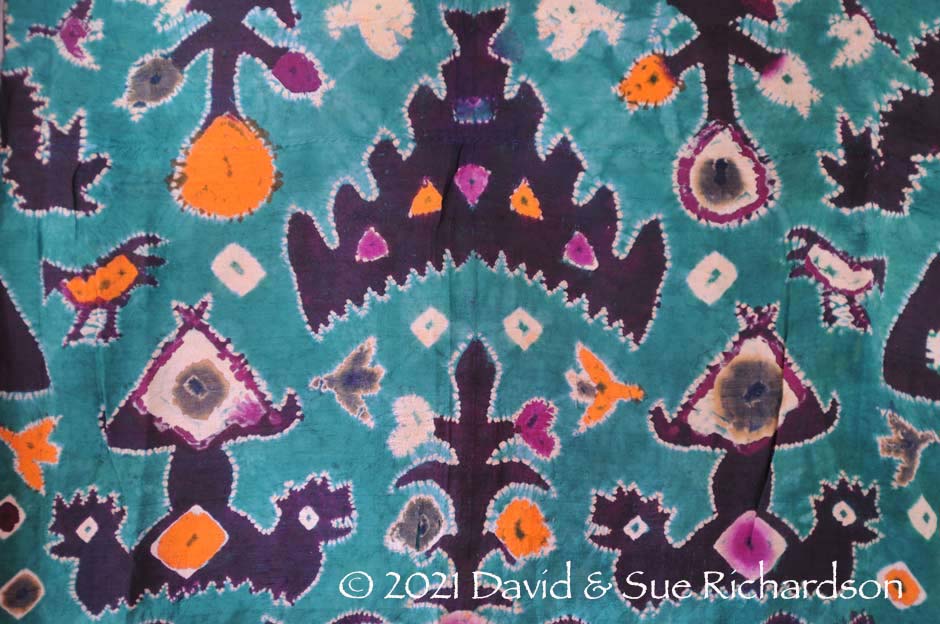

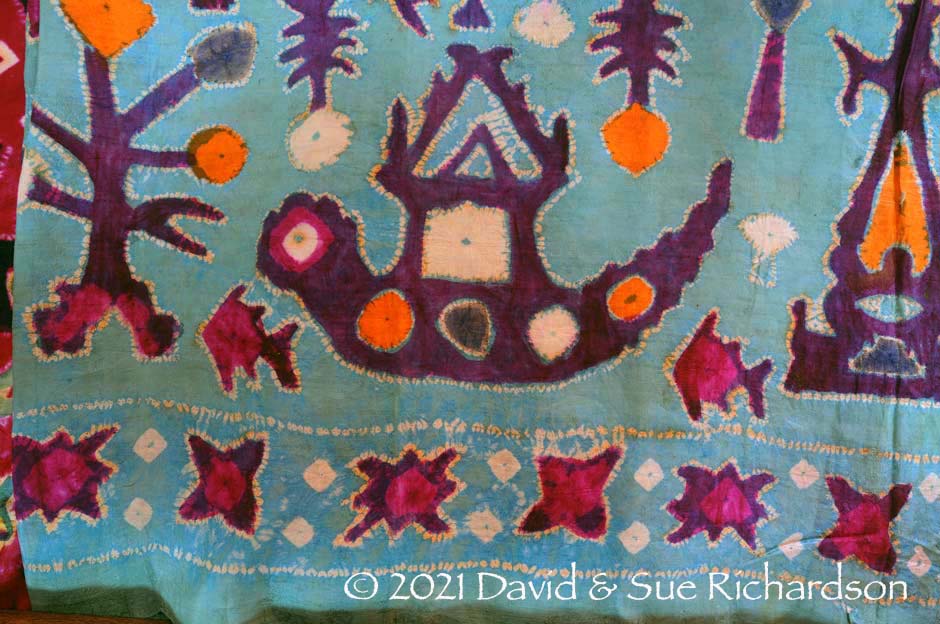

Complex Pictorial Kiet Cloths

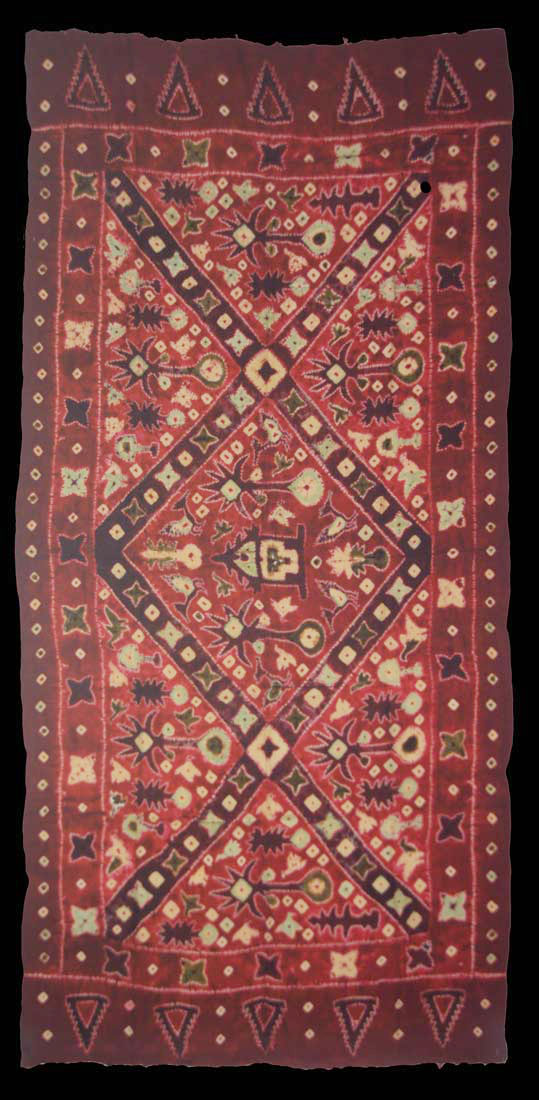

A unique collection of dramatically decorated silk kiet was acquired by the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh in 1928. Somehow these textiles miraculously survived the madness of the Pol Pot era. Following its forced closure in 1975, the museum was damaged and some of its collections stolen. Only 10 of the 70 knowledgeable staff employed by the museum survived the Khmer Rouge programme of exterminating educated people (Bunker 2005, 315). Not surprisingly, the provenance of the collection has been lost.

A pictorial kiet decorated with a pavilion, trees of life, chickens and birds

National Museum of Cambodia

The kiet in this collection were made from imported machine-woven silk and richly coloured synthetic dyes. They have a rectangular centre field flanked by side borders and narrow end panels that extend from selvedge to selvedge. Their sizes are in the range of 180-196cm long and around 90cm wide. They have strong coloured backgrounds of maroon red, cerise pink or turquoise naively covered with a wide range of traditional and modern motifs, especially the bird, nak river dragon and tree-of-life, but also fish, boats and cars; dogs, deer, buffalo and elephants; and chickens, swans and peacocks.

While the outlines of the motifs have been produced by means of tritek, and the diamonds and stars by means of pelangi, the blocks of colour seem to have been applied using dye painting.

An example decorated with cars and bicycles or motorcycles might illustrate the main road in central Phnom Penh that runs along the bank of the Sap River, one of our favourite locations in the city, today known as Sisophon Quay. The vehicles pass in front of Chinese shop fronts while Chinese junks, modern steamers and fish are found in the river. Apparently the first car arrived in Cambodia in 1912, dating the textile to the sixteen-year period between 1912 and 1928 (Green 2008, 61).

Above: An old-fashioned car passes in front of the arched openings of a Chinese shop

Below: A Chinese junk with mast and sail along with fish

Another dramatic example with a turquoise ground shows ceremonial boats or floats known as pratib, which formed a procession along the Sap River in Phnom Penh to celebrate the end of the rainy season.

A pictorial kiet decorated with a pavilion roof, trees of life and pratib floats

National Museum of Cambodia

Above and below: Details of a pictorial kiet with pratib floats, trees of life and the roof of a pavilion. National Museum of Cambodia

The naïve nature of these textiles is utterly charming. They have an almost child-like character, conveying a sense of festival and fun.

Detail of a pictorial kiet with a boat in the shape of a nak bearing a pavilion

National Museum of Cambodia

Detail of a pictorial kiet decorated with a lattice of zoomorphic and vegetative motifs – such as dogs, chickens, deer, cattle, water buffalo and trees of life. National Museum of Cambodia

Just like the simple kiet cloths, it is hard to believe that these dramatically decorated, brightly coloured textiles were made for Cham use. It is likely that these cloths were created by Cham artisans to be worn by Khmer women for the annual Khmer celebrations. It is also possible that some were produced by Khmer pelangi makers.

Some pictorial kiet decorated with nak sea serpents were used as bridal wedding sashes, known as spai (Green 2008, 128 and 134). Such sashes were a love token given by the fiancé to his fiancée during their engagement. The nak was a reference to the Cambodian Preah Thong legend in which Preah Thong, an earthly prince, married Nang Neak, a sea serpent, thus uniting the realms of the land and the sea.

The close similarity of all these pictorial kiet cloths suggests their production was limited to just one single village or small region, which the American collector John Ruddy has suggested could be located close to the border region with Vietnam, such as Kampot in the far south or Kampong Cham further north.

Sadly we will never know the full history of these textiles because it was lost during the era of death, terror and chaos imposed on the people of Cambodia by the evil Marxist Khmer Rouge.

Return to Top

Modern Kiet Cloths

Simple silk kiet textiles are still made in Cambodia today, although we have yet to identify the village or villages in which they are produced.

A modern kiet textile acquired in Siem Reap

Richardson Collection

According to Bernard Dupaigne, in the late 1960s Cham/Malay weavers were producing kiet head cloths using plangi in the village of Prek Reing in southernmost Kandal Province (1980, 33).

Return to Top

Bibliography

Baudesson, Henry, 1919. Indo-China and Its Primitive Peoples, translated from the French by E. Appleby, Hutchinson, London. Republished in 1997 by White Lotus Press, Bangkok.

Bruckmayr, Philipp, 2019. Cambodia’s Muslims and the Malay World: Malay Language, Jawi Script, and Islamic Factionalism from the 19th Century to the Present, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Bühler, Alfred, 1942. The Origin and Extent of the Ikat Technique, Ciba Review, vol. 44, pp. 1604-1611, Basel.

Bühler, Alfred, 1943. Materialien zur Kenntnis der Ikattechnik definition und bezeichnungen, geschichtliches, mechanische Verarbeitung des Garnes, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie 43, Supplement, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Bühler, Alfred, 1953. Plangi – Tie and Dye Work, Ciba Review, no. 104, pp. 3721-3748, Basel.

Bühler, Alfred, 1972. Ikat, Batik, Plangi, Reservemusterungen auf Garn und Stoff aus Vorderasien, Zentralasien, Südosteuropa und Nordafrika, Pharos, Basel.

Chandler, David P., 1983. A History of Cambodia, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

Collins, William, 2009. The Muslims of Cambodia, Ethnic Groups of Cambodia, pp. 2-173, Centre for Advanced Study, Phnom Penh.

Dahles, Heidi, and Horst, John ter, 2006. Weaving into Cambodia: negotiated ethnicity in the (post) colonial silk industry, Expressions of Cambodia: The politics of tradition, identity, and change, pp. 119-132, Routledge, London and New York.

Daravuth, Ly, and Muan, Ingrid, 2003. Seams of Change, Clothing and the Care of the Self in Late 19th and 20th Century Cambodia, Reyum Publishing, Cambodia.

Dupaigne, Bernard, 1980. Répartition des Tissages Traditionnels au Cambodge, Cheminements: Écrits offerts à Georges Condominas, Asie du Sud-Est et Monde Indonésien, vol. 11, pp. 327-337.

Fraser-Lu, Sylvia, 1988. Handwoven Textiles of South-East Asia, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Green, Gillian, 1997. The Cambodian Weaving Tradition: Little Known Weaving and Loom Artefacts, Arts of Asia, vol. 27, issue 5, pp. 78-90.

Green, Gillian, 2003. Traditional Textiles of Cambodia: Cultural Threads and Material Heritage, River Books, Bangkok.

Green, Gillian, 2005. Spirit Ships: Ancient Images on Cambodian Narrative Textiles, Arts of Asia, vol. 35, issue 3, pp. 38-47.

Green, Gillian, 2008. Pictorial Cambodian Textiles: Traditional Celebratory Hangings, River Books, Bangkok.

Hà, Thuy, 2016. Splendeur du costume traditionnel féminin des Cham, Le Courier du Vietnam, 05.03.2016.

Hawk, David, 1983. The Cham Ethnic Minority Group, Political Killings by Governments of Their Citizens: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Organizations of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Ninety-eighth Congress, First Session, November 16 and 17, 1983, pp. 108-112, US Government Printing Office, Washington.

Heywood, Denise, 2008. Cambodian Dance: Celebration of the Gods, River Books, Thailand,

Horst, John ter, 2008. Weaving into Cambodia: Trade and Identity Politics in the (post)-Colonial Cambodian Silk Weaving Industry, Doctoral Thesis, Vrije University, Amsterdam.

Howard, Michael C., 2008. Supplementary Warp Patterned Textiles of the Cham in Vietnam, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 243.

Hubert, Jean-François, 2005. The Art of Champa, Parkstone Press, New York.

Iwanaga, Etsuko, 2003. The Textiles of Cambodia, Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka-shii,

Jacob, J., 1974. A Concise Cambodian-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Larsen, J. L., 1979. The Dyers’s Art: Ikat, Batik, Plangi, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

Marchal, Sappho, 2005. Khmer Costumes and Ornaments of the Devatas of Angkor Wat, Orchid Press, Bangkok.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2002. Traces of War: The Revival of Silk Weaving in Cambodia, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 528.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2004. Traditional Textiles in Cambodia, Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles, Siem Reap.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2004. “Hol” the Art of Cambodian Textiles, IKTT, Phnom Penh.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2008. Bayon Moon, IKTT, Phnom Penh.

Morimoto, Kikuo, 2009. Private discussions, Wisdom of the Forest Village, Siem Reap.

Moussay, Gerald, 2004. Cham Weaving in Vietnam, Through the Thread of Time: Southeast Asian Textiles, pp. 152-161, River Books, Bangkok.

Phụ, Bá Trung, Undated. Áo Dài Cham Trong Su Giao Thoa Van Hóa Viet Nam.

Sabeone, Federico, 2017. Islam in Cambodia: The fate of the Cham Muslims, European Institute of Asian Studies, Brussels.

Sokhom, Hean, 2009. Ethnic Groups in Cambodia, Centre for Advanced Study, Phnom Penh.

Sokny, Sor, Ratha, Phat Chanmoy, and Vannak, Som, 2007. Technique of Natural Dyeing and Traditional Pattern of Silk Production in Cambodia, UNESCO, Phnom Penh,

Spancake, Jenny L., 2015. Tie-Dyeing – What’s in a Name?, Thai Textile Society Newsletter, vol. III, issue 1, pp. 9-11, Bangkok.

Steinberg, David J., 1959. Cambodia: Its People, its Society, its Culture, HRAF Press, New Haven.

Van Dish, Truong, 2003. Traditional Textile Craft of the Cham, Ethnic Culture Publishing House, Hanoi.

Wang, le, and Zhao, Feng, 2017. Xie, a Technical Term for Resist Dye in China: Analysis Based on the Burial Inventory from Tomb 26, Bijiatan, Huahai, Gansu, Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, pp. 437-450, Zea Books, Lincoln, NE.

Warming, Wanda, and Gaworski, Michael, 1981. The World of Indonesian Textiles, Kodansha International, Tokyo.

Whitaker, Donald P., et al, 1973. Area Handbook for the Khmer Republic (Cambodia), US Government Printing Office, Washington.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 21 May 2021.