Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Kisar Textiles

The Female Tubeskirt

The Oirata Tubeskirt

The Meher Tubeskirt

The Term Rimanu

The Male Loincloth

The Bark Loincloth

The Oirata Mal

The Meher Kornele He

The Male Ceremonial Loincloth

The Cloths for a Purka Priest

The Waist Belt or Sash

The Male Blanket

The Oirata Namlau

The Meher Hoire

The Terms Senikir, Sanikir and Snikir

The Selendang

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 1

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 2

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 3

Introduction

This webpage provides the first complete classification and description of the textiles that were once produced on Kisar Island, only a few of which are still being made today. It combines the previous accounts of earlier visitors with the findings of our own 2017 field trip to the island and our more recent examination of the Kisar textiles acquired by Heinrich Kühn in 1888, by Professor Alexander W. Pflüger in 1900 and by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar in 1914, all held in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Köln.

The Peuk cultural group from dusun Worono, Oirata Barat, performing at Lewkloor in 2015

(Image courtesy of Giel Wevers)

Thanks to our local informants we now have a clear perspective on the textiles that were produced on Kisar Island in recent decades. Here we combine that knowledge with the information extracted from earlier historical reports, often difficult to decipher when considered in isolation, in order to provide a more meaningful understanding of the textiles that were made over the past one and a half centuries, what they were made from, and what they were called by the people who produced and wore them.

Return to Top

Kisar Textiles

In the past there were three weaving communities on Kisar, the majority Meher-speaking population, the minority Oirata-speaking group whose ancestors came from East Timor, and the small mixed-race mestizo population, whose forefathers were the Dutch and other European soldiers once stationed on the island. While examples from the first two communities abound we have yet to track down a single example of mestizo weaving, which is disappointing since the mestizo textiles may have been spectacular. As Ernst Rodenwaldt discovered, weaving within the mestizo community had already declined substantially as long ago as 1926. We have however identified that at least one mestizo shawl was recorded as having been acquired by the Koloniaal Museum in Amsterdam (the predecessor of the Tropenmuseum) in 1897 (Maatschappij-Belangen 1897, 337).

The main European museum collections of Kisar textiles are to be found in the following locations:

- the Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museum zu Berlin, supposedly holds the textiles acquired by Johan Jacobsen in 1888, although none are listed in an online search of their collection

- the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Köln, holds a few textiles collected by Heinrich Kühn, who accompanied Jacobsen in 1888, as well as those acquired by Professor Alexander W. Pflüger in 1900 and by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar in 1914

- the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen in Rotterdam and the Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden hold textiles collected by a large number of Dutch visitors over the period from at least 1832 to 1948. Unfortunately their provenance is poorly recorded.

It is clear from the Rautenstrauch-Joest and Richardson Collections that weavers on Kisar had ready access to commercial mechanically-spun single-ply and two-ply cotton yarns, pre-dyed commercial yarns and possibly synthetic red dyes at a very early stage. All are found in the textiles that were acquired by Heinrich Kühn in 1888. Small quantities of pre-dyed silk are found in one of the textiles acquired by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar in 1914. At the same time textiles made from naturally dyed hand-spun yarns have continued to be made up to the recent past.

It would be fascinating to analyse the dye(s) used to colour these early pre-dyed yarns. Synthetic alizarin was only launched by BASF in the early 1870s and the more sucessful disazo dye Congo Red was launched by Agfa in the mid-1880s. The arrival of synthetically dyed commercial yarns from Europe must have caused much excitement among the weavers on Kisar. They would have been relatively expensive and beyond the reach of the average islander and were intially employed to add narrow stripes to the shoulder cloths for local shaman and to weave prestigious narrow belts. It was only later that they were used to insert warp stripes on tubeskirts.

For the past half-century the layout and decoration of the majority of Meher and Oirata textiles has been strictly proscribed. Sarongs in particular fall into strict categories and there appears to have been little room for individual expression. These restrictions seem to have been less important in the past, with the greatest variability found in men’s belts, loincloths and blankets. The increasing adoption of western clothing has led to a progressive erosion of men’s traditional costume during the twentieth century. Loincloths and narrow belts became obsolete first and this was followed by a decline in the use of men’s blankets – these have not been made for some decades among the Oirata. The weaving of shoulder cloths for priests seems to have died out between the two world wars. Women’s ceremonial sarongs have remained the most resilient to change, and continue to be worn up to the present day.

Of the two main weaving communities, the finest binding and the widest range of textiles are found among the Oirata. As already reported, textile production within both the Meher and the Oirata communities is now in terminal decline, with only a handful of artisans still able to produce traditional cloths.

Today very few museums or private individuals acquire their Indonesian textiles in the field, relying instead on Western auction houses and a combination of Western and Indonesian dealers. Although many acquire beautiful textiles by this means, the resulting collections have little value to the textile historian. This is because all of the knowledge of when, where, why and by whom most of these textiles were made has been lost. Although their new owners often assign names, dates and locations to these textiles, these assumptions need to be viewed with great scepticism – especially as both dealers and collectors have a tendency to claim their textiles are older than they really are. It is simply impossible to date a textile through visual inspection alone, and while comparisons with similar examples with known provenance in other collections (which are few and far between) might give a rough indication of origin and identity, textiles and the terms assigned to them often vary from village to neighbouring village. This is why so many of the attributions assigned to textiles that lack provenance are mistaken.

At the same time, few custodians of Indonesian textiles conduct rigorous in-depth research into their collections – the one notable exception being the Fowler Museum under the stewardship of Roy Hamilton.

Serious collecting involves a lot more than shopping and chatting on internet forums – it requires spending time in each region, understanding the local techniques of yarn production, binding, natural dyeing and weaving, along with the social context within which they were used. Scholarly research engenders friendship with and respect from the people who still make these textiles and, over time, makes it possible to acquire fine examples from the families who have owned and used them for many decades – in some cases for more than a century. Only they know when these textiles were made; who they were originally made by; when and where the weaver was born; what clan she belonged to; when and where she made it and for what purpose; and how it has been subsequently used. By building up a collection of textiles from a specific geographical region with known provenance it is not only possible to establish how designs and motifs vary from village to village but to understand how local costume has evolved over time.

Because of this approach, of the forty or so Kisar textiles in the Richardson Collection, more than half have fully documented provenance. They provide a good representation of both the Meher and Oirata communities, with textiles dating from 1920 up to the present day.

Return to Top

The Female Tubeskirt

The women of Kisar seem to have only ever made two-panel warp ikat tube-skirts. These were woven on a long continuous warp thereby producing a single loop of finished cloth, which was then cut into two matching rectangular panels. No special significance was given to the short unwoven section of warps, which was discarded.

Kisar Islanders dressed in modern festival costumes in Wonreli

Note how the top of the sarong has been folded down over the stomach

(Image courtesy of Hilary Hopkins)

A woman’s sarong is called a lau by the Oirata and a homnon by the Meher. The Leiden scholar Nazar Nazarudin, who specialises in the linguistics of the Oirata, has pointed out to us that both terms seem to have derived from the word for dark or black – lauare in Woirata and mohon in Meher. If that is so, one wonders if Kisar clothing was much darker in the past, as it was on Sumba.

Both the lau and the homnon are worn with the top folded down and the vertical seam positioned at the front, concealed by a fold. Today women do not hold their sarong in place with a belt. When Johan Jacobsen visited Kisar in 1888 he found that women held their sarongs in place with either a pin or a narrow waist belt made from palm strips, called a bato by the Oirata and an ehe by the Meher (1896, 119). The belts were decorated with carved patterns and then treated with lime to make the patterns stand out against the yellow or dark-coloured palm wood.

Some confusion has been caused by a brief comment made by Brigitte Khan-Majlis that if the ikat colouration in the widest decorative band of a sarong was indigo it was more likely to come from Luang than from Kisar (1991, 321). This observation is completely misleading and has led to some Kisar sarongs being classified as coming from Luang. On Kisar both the Oirata and the Meher dye the main ikat bands in their sarongs, blankets and loincloths with indigo, morinda or kusambi. The choice is entirely down to the discretion of the weaver and no one colour has any higher preference or status than the others.

Return to Top

The Oirata Tubeskirt

The Oirata call a woman’s skirt a tuhur lau, literally ‘woman’s skirt’. Josselin de Jong transcribed it as la’u, implying that the ‘u’ is stressed (1937, 249). Today the lau is always worn with a tuhur rain or kebaya blouse, usually coloured (De Jong 1937, 279). In the past many women on Kisar went topless, although as early as 1825 Dirk Kolff recorded that the local noblewomen of Wonreli turned out to meet him in sarongs and black kebayas (1940, 53). A shop-bought sarong is a kampia lau (De Jong 1937, 244).

Two women dressed in ceremonial costume at a wedding in Oirata Timur

There are at least seven main categories of Oirata sarong which, in terms of increasing status, are as follows:

| lau o’ohira halin |

| mauwesi lau |

| lau o’ohira hatin |

| lau o’ohira hatin’ni |

| lau ahi leu ru |

| lau ma’maro |

| lau metleur sorot |

In addition there are a few special designs, which do not fit into any of these categories.

The Lau O’ohira Halin

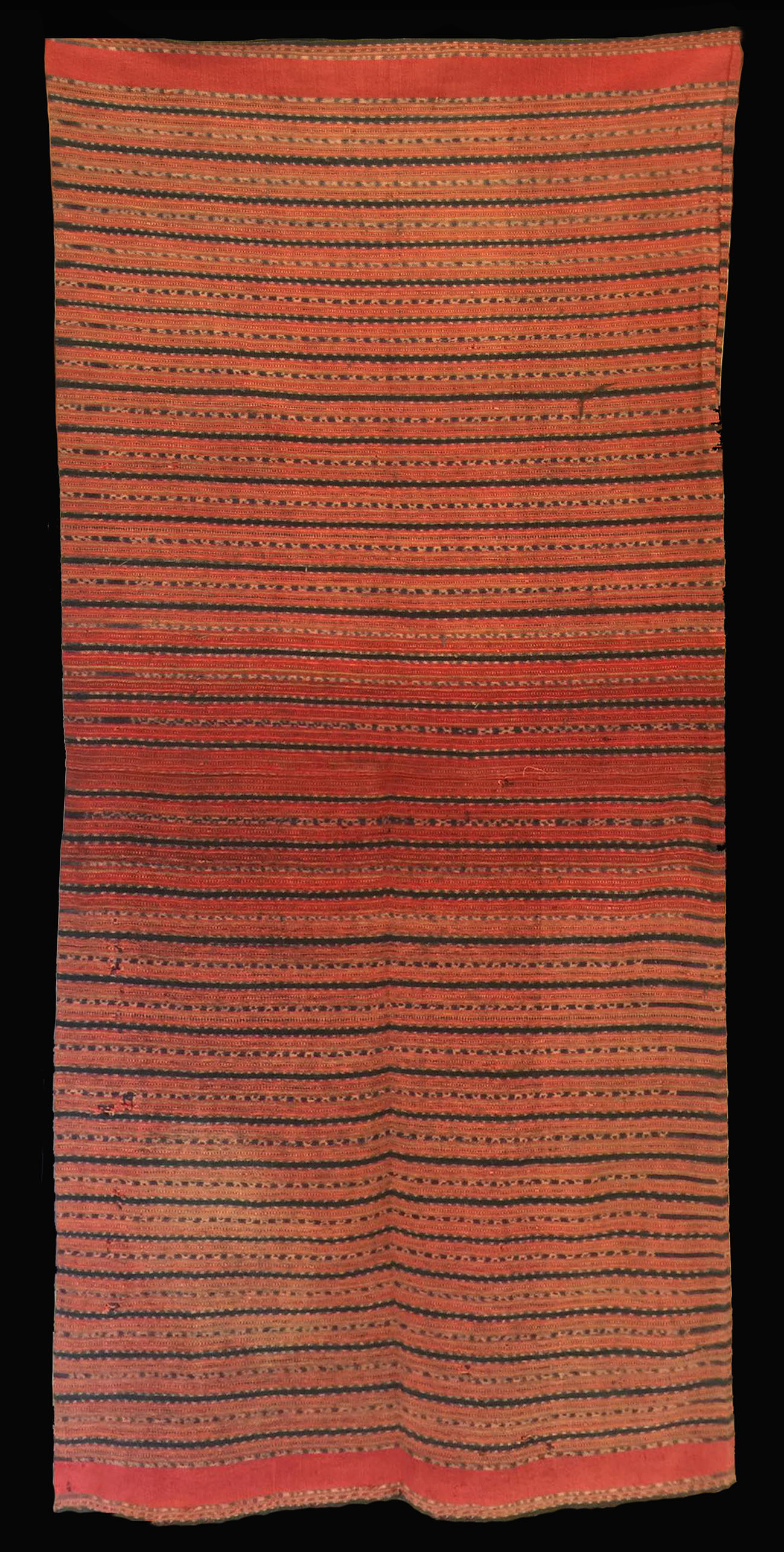

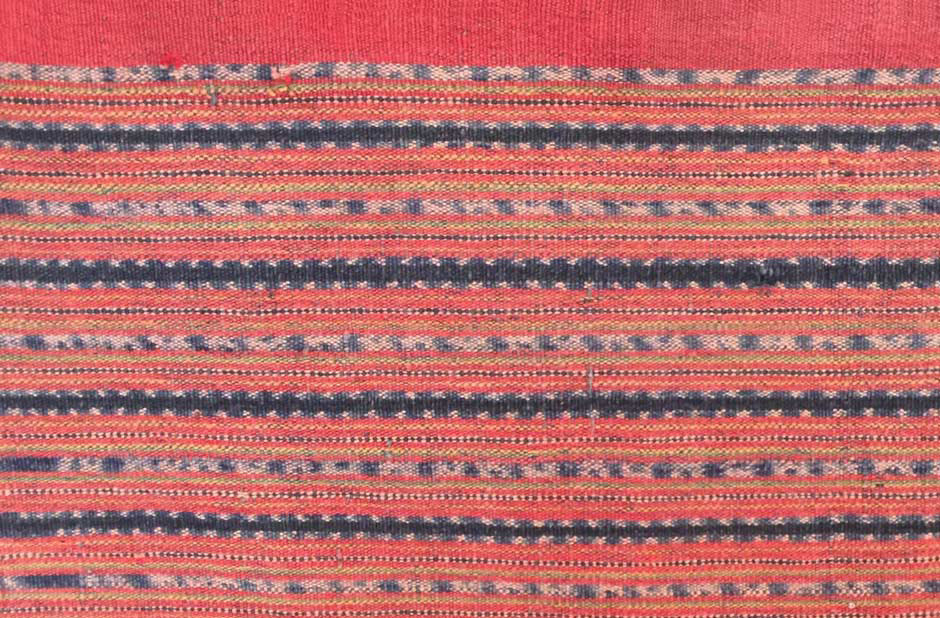

The simplest Oirata sarong of all appears to be the lau o’ohira halin, which is completely covered in a repetitive sequence of narrow plain red and plain and ikatted indigo warp stripes, interspersed with yellow and green lines. It has a narrow plain terminal band at each end and lacks any main decorative bands of ikat.

The term o’ohira refers to the edge or panel of a sarong, while halin means without - so o’ohira halin refers to the absence of a main decorative band.

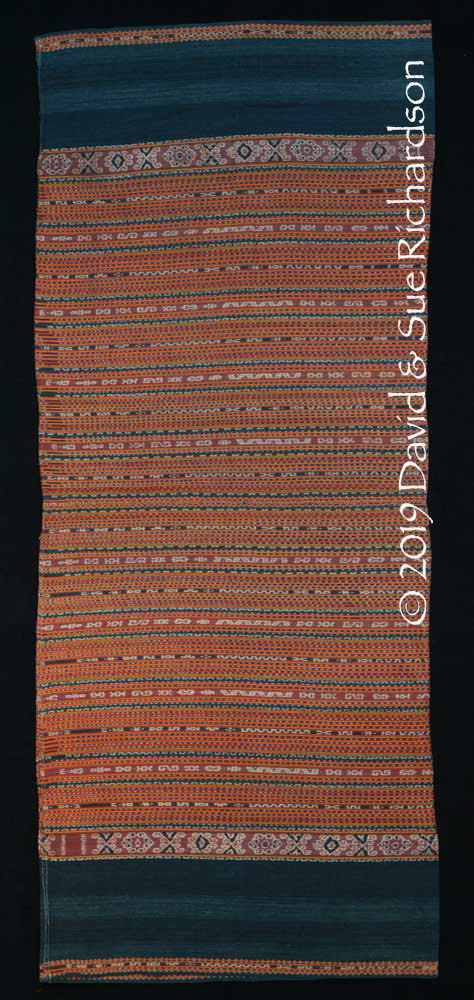

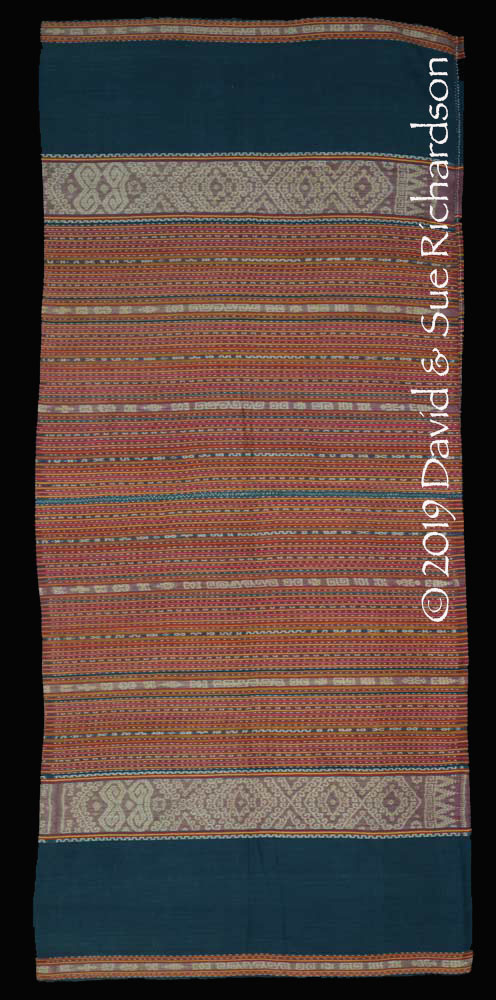

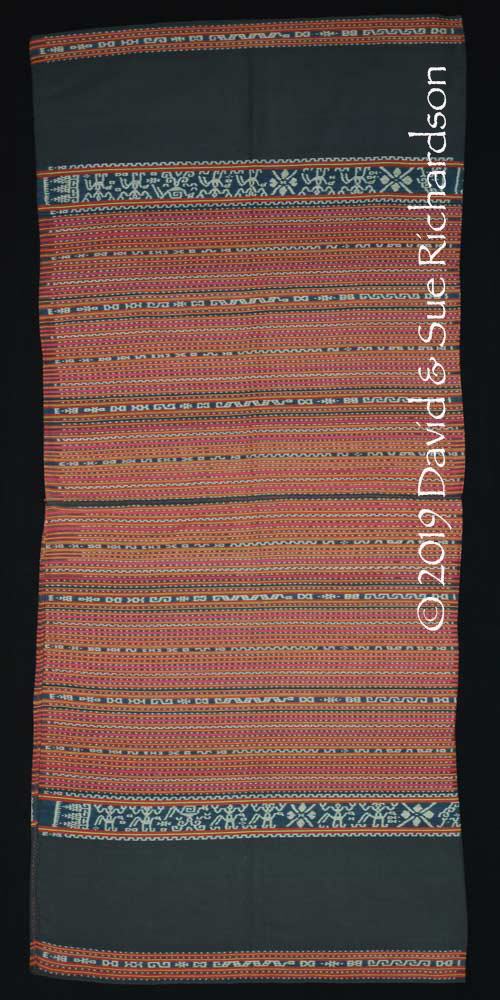

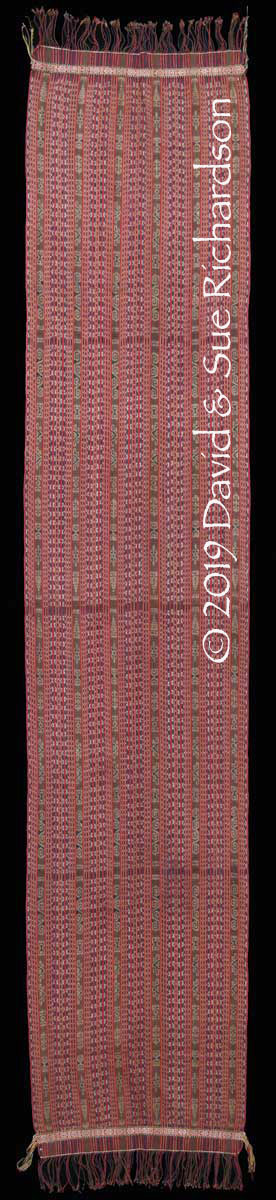

A lau o’ohira halin woven about 45 years ago by Terovina Tamindael, now aged 65, a noblewoman from pada Asatupa, one of the three clans in Oirata Barat

Richardson Collection

The Oirata refer to the narrow red stripes that separate the narrow lines of ikat as horo horo, horo meaning to enclose or encircle.

Detail patterning on the above lau o’ohira halin

A very similar looking naturally dyed sarong was collected by Kühn in 1888, although there is no record of whether he obtained it from the Oirata or the Meher. Although labelled a homnon, this everyday sarong looks very much like an Oirata lau o’ohira halin.

A possible late nineteenth century Oirata lau o’ohira halin. Collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inv. no. 12742

Detail of the above lau o’ohira halin

Despite its simplicity, it is clear that the lau o’ohira halin has not been woven for many decades. Because they were items of daily use, few examples have survived. Today most women wear printed cotton sarongs, trousers or denim jeans for everyday wear.

The Mauwesi Lau

The mauwesi lau, so-called because the design is said to come from a place called Mauwesi in East Timor, is a slightly more complex sarong. We cannot locate any village of this name in Timor-Leste and wonder if it derives from the village called Maubesi in Cova Lima district. Some of the ancestors of the Selewaku clan in Oirata Timur and the Ira Ara clan in Oirata Barat originated from this very same village (Wedilan 2014).

A very old and well-worn mauwesi lau in Oirata Barat

The central section of the mauwesi lau is decorated with simple narrow alternating morinda and indigo, red and black, or pink and blue stripes, bordered above and below with a wide band composed of further narrow and wider stripes, some of which are ikatted, and a wide outermost band of plain indigo. Mauwesi lau are used for everyday wear or for a funeral where it would be inappropriate to wear a more decorative ceremonial skirt.

These too are no longer woven today.

The first mauwesi lau in our collection was woven by the late Lorenci Serain about 65 years ago in Oirata Timur. She was a noblewoman from the Soho-Radi house of pada Hano’o, the highest status land-owning clan in Oirata Timur. She informed us that this was the first sarong that she ever made while she was still a young unmarried woman. Lorenci sadly died on 30 October 2018 at the age of 85.

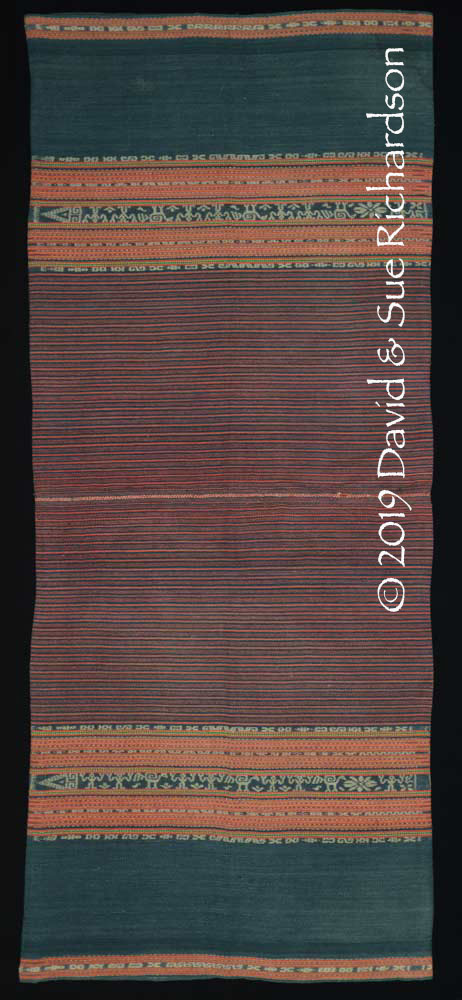

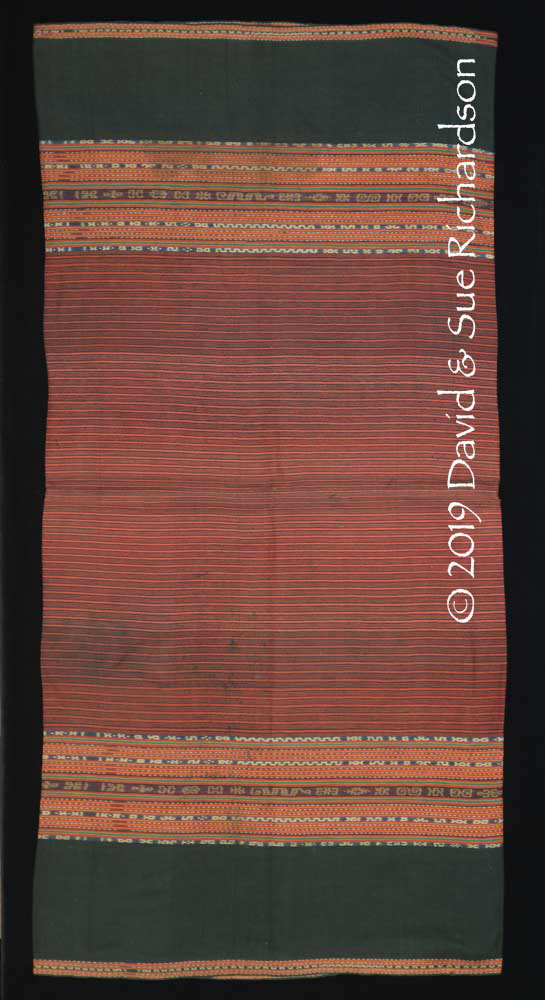

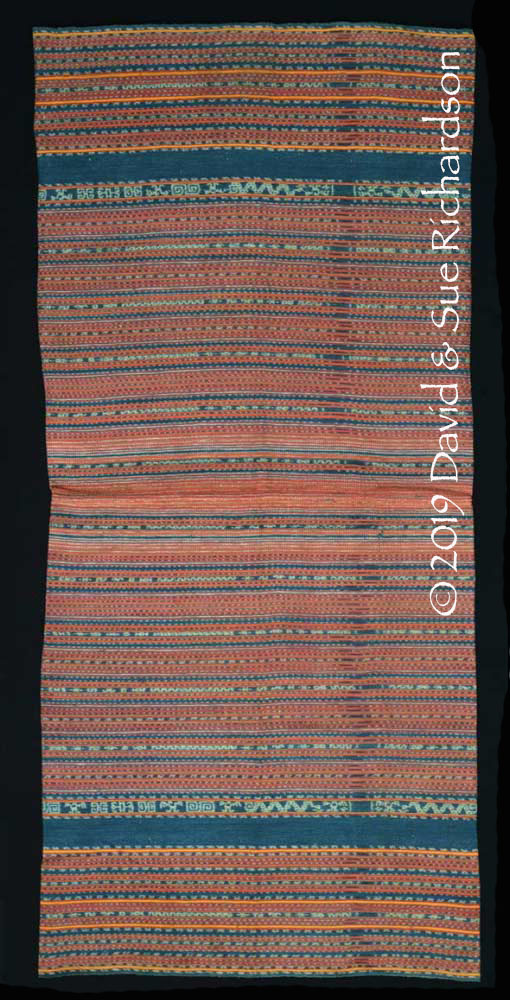

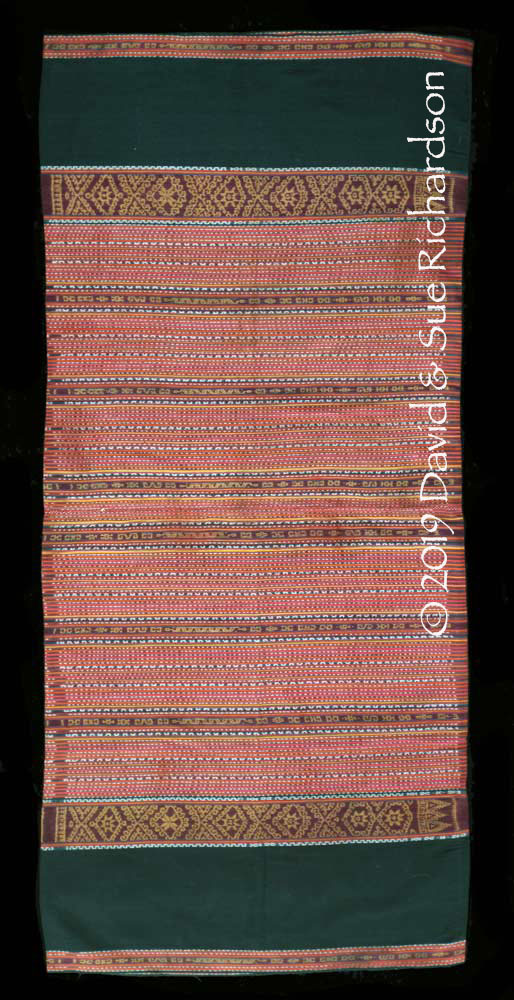

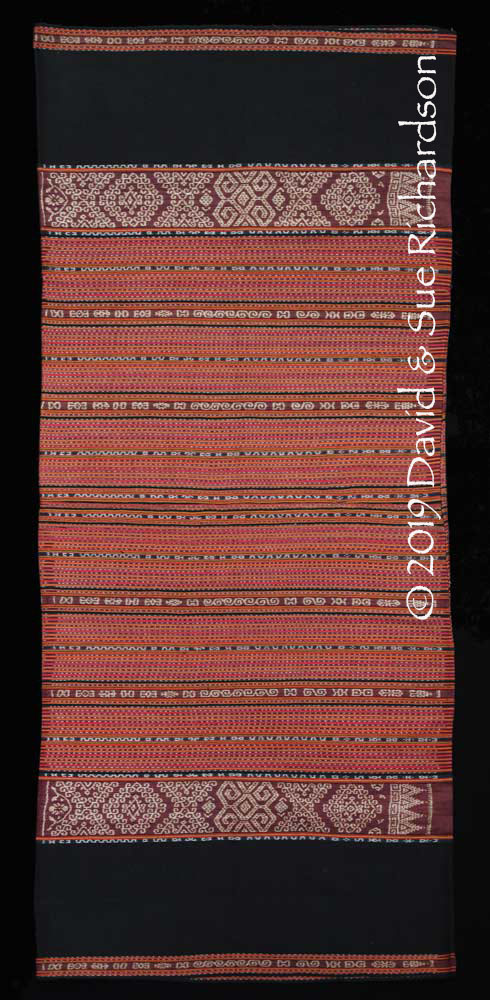

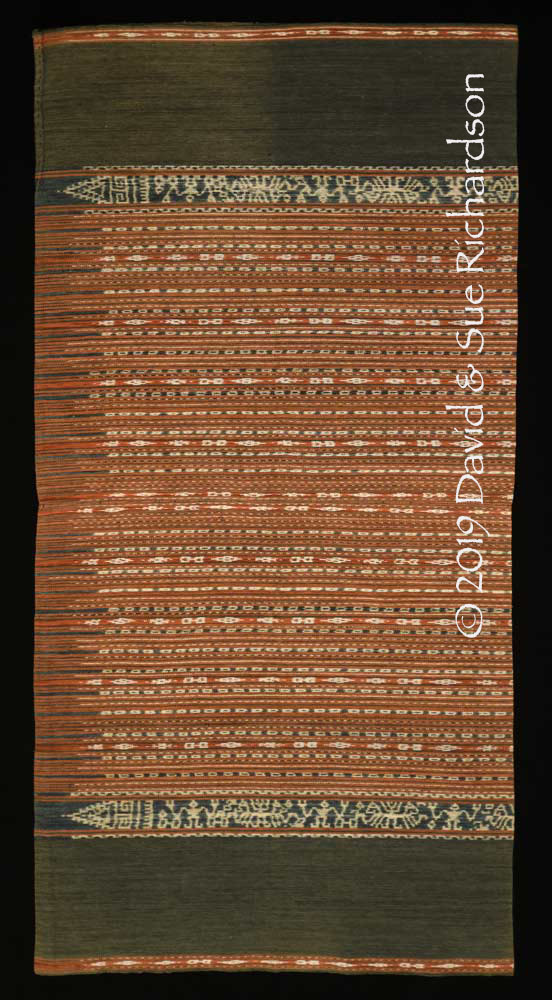

A mauwesi lau woven by the late Lorenci Serain about 65 years ago in Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

The second was woven over 70 years ago by the late Lambertina Ratu Sehaka, who belonged to the lineage Le Eka of pada Selewaku, another one of the four clans in Oirata Timur. She was a noblewoman belonging to the marna caste whose family, the Ratu Sehaka, were one of the founders of Manheri (meaning 'east hill') - the original Oirata Timur settlement.

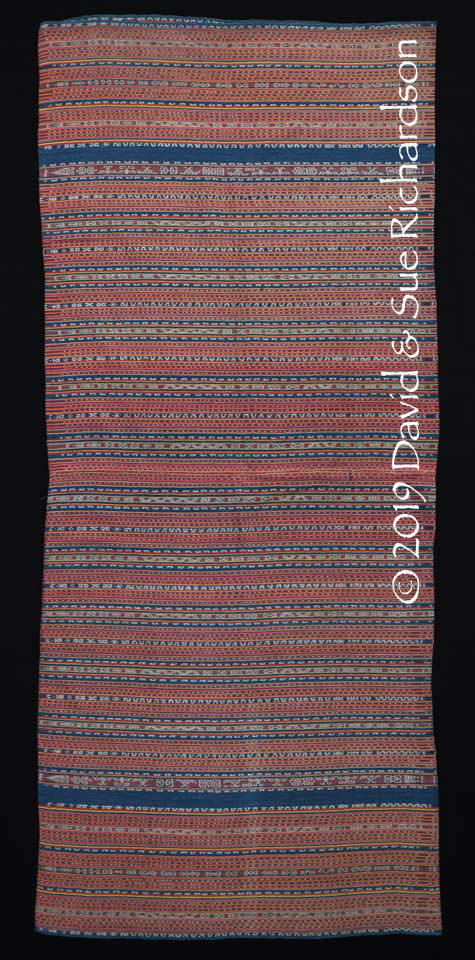

A mauwesi lau woven over 70 years ago by the late Lambertina Ratu Sehaka from Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

A mauwesi lau woven by Levina Hooru in the 1920s has a slightly simpler design. The weaver was born into the important Hooru family of Oirata Barat.

A mauwesi lau woven around 90 years ago by Levina Hooru in Oirata Barat. Family heirloom

A more elaborate mauwesi lau in the collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Köln, inventory number 36581, was collected by Müller-Wismar in 1914. It came from the Oirata and is decorated with wider, more elaborate ikat bands. The weavers in Oirata Timur say that it is a mauwesi lau decorated with a pattern belonging to the same pada Selewaku of Oirata Timur.

Mislabelled a homnon, this mauwesi lau is attributed to the Selewaku clan of Oirata Timur. Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 12742

The Lau O’ohira Hatin

The rare lau o’ohira hatin (not to be confused with the lau o’ohira halin) has two panels almost completely covered in narrow stripes apart from a narrow band of plain indigo and a narrow band of pictorial ikat. The latter can be either indigo or morinda.

The term o’ohira means the edge or panel of a dress (or a lip) and hatin means divided or in the middle, so a lau o’ohira hatin is a sarong with the panels divided by a plain band of indigo and a narrow band of ikat.

These sarongs are ceremonial but do not seem to have been woven for some decades.

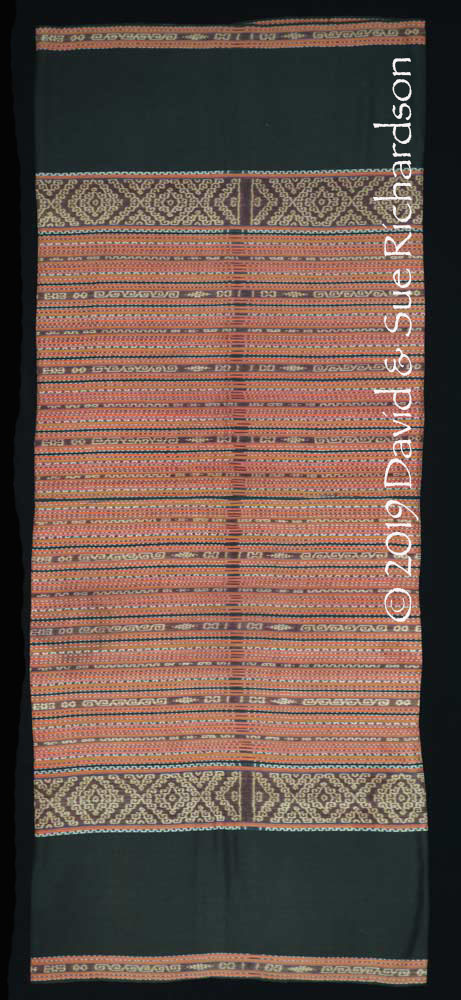

Lau o’ohira hatin woven about 30 years ago by Oktavina Lewedalu, now 71 years old, from the noble Lewe Dalu kodo of Pamodo pada, one of the four clans of Oirata Timur

Richardson Collection

Lau o’ohira hatin acquired on Timor with no provenance. Richardson Collection

Peter ten Hoopen has illustrated a fine lau o’ohira hatin but has mistakenly attributed it to the island of Luang (2018, 512).

The Lau O’ohira Hatin’ni

The lau o’ohira hatin’ni is very similar to the lau o’hira hatin but the main ikat band is wider. As before, hatin means divided and on its own and ni means tie. However in this case the suffix ni gives the word hatin more emphasis (Lewelipa 2018). So a lau o’ohira hatin’ni is a lau in which the panels are even more divided – by a plain indigo band and a band of ikat.

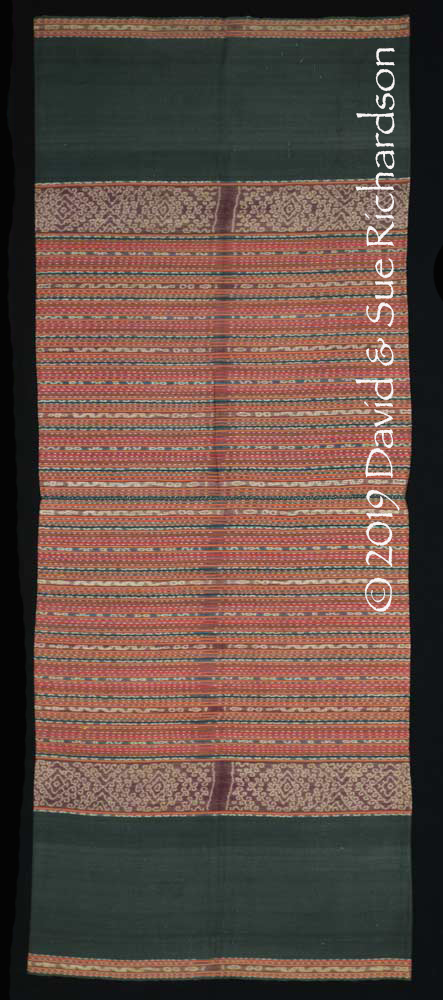

The following magnificent lau o’ohira hatin’ni was woven in 1946 or 1947 by the late Lenci Namtilu from the Ha’yau house of pada Asatupa from Oirata Barat. Born in 1920, she wove this sarong to prove she was a proficient weaver, thereby gaining her parents' permission to marry. She married late at the age of 28.

A lau o’ohira hatin’ni woven by the late Lenci Namtilu from the Ha’yau house of pada Asatupa from Oirata Barat. Richardson Collection

Although the second lau of this type has no provenance, our informants in Oirata say that the design belongs to pada Hano’o, the highest status clan in Oirata Timur.

A lau o’ohira hatin’ni acquired on Timor with no provenance. Richardson Collection

The Lau Ahi Leu Ru

The ceremonial lau ahi leu ru has a central section completely filled with alternating narrow stripes of red plain weave and indigo and morinda ikat, bordered above and below with a main band of ikat and a wide outer band of plain indigo or black. These narrow red stripes are called horo horo, horo meaning to enclose or encircle.

The main ikat band is decorated with the ahi leu ru or fish basket pattern, consisting of a row of hooked diamonds terminating at each end with a set of four or more tumpal motifs. A few examples also include a floral motif. The colour of this band can be indigo blue, morinda brown or kusambi purple, depending on the preference of the weaver. None of these colours conveys any higher status. In the past this pattern was not restricted to the noble marna caste and could be worn by commoners.

The very simplest lau ahi leu ru in our collection has limited provenance. All we know is that it was woven by a woman from the leading Hano’o clan of Oirata Timur roughly 30 years ago. The morinda-dyed band of ikat has then been hand-painted with black.

A simple lau ahi leu ru from the Hano’o clan of Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

The main ikat bands in the second example, which was acquired on Timor Island, were dyed with kusambi bark. The hooked diamonds enclose eight-pointed stars and flowers.

A lau ahi leu ru acquired on Timor with no provenance. Richardson Collection

The two most recently made lau ahi leu ru in our collection with known provenance were woven about 30 years ago by Jul Resimere, a 65-year-old noblewoman from Oirata Timur. She belongs to the Resimere house of pada Selewaku. She dyed the main ikat band of the first example with morinda and of the second example with kusambi.

A lau ahi leu ru woven by Jul Resimere from pada Selewaku, Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

A second lau ahi leu ru also woven by Jul Resimere. Richardson Collection

An older example was woven about 45 years ago by Oktavina Serain, a 69-year-old woman from Oirata Timur. She is a noblewoman from the Soho-Radi house of the leading pada Hano’o.

A lau ahi leu ru woven about 45 years ago by Oktavina Serain from the leading pada Hano’o. Richardson Collection

The two oldest and finest lau ahi leu ru in our collection were woven by Levina Hooru between 1925 and 1930. She was born in about 1900 and lived in rumah Kelihi in Oirata Barat. The Hooru family has played a leading role in the leadership of Oirata Barat over the past century, providing many of its kepala desa.

Above and below: two lau ahi leu ru, both woven by Levina Hooru between 1925 and 1930. Richardson Collection

An even earlier lau ahi leu ru, mistakenly labelled as a homnon, was collected by Müller-Wismar in 1914, and dated to around 1900. Woven from hand-spun cotton and completely naturally dyed, the skirt is short and has a simple design. Despite being the oldest example here, the quality of the morinda ikat is quite poor and the indigo has been painted on by hand.

A naturally dyed lau ahi leu ru collected in 1914

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36573

Interestingly the central section of narrow horo horo stripes contains numerous thin, naturally dyed pale yellow and green lines woven from just a few warps. This shows that the similar yellow and green thin warp stripes found in later weavings are the continuation of a long tradition and were not inspired by the arrival of pre-dyed machine-spun yarns.

The Lau Ma'maro

The ceremonial lau ma’maro has exactly the same layout as the lau ahi leu ru with one exception – the main ikat band is decorated with anthropomorphic, zoomorphic and floral motifs rather than hooked diamonds. The most common motifs are a stick-like anthropomorphic figure standing legs akimbo with outstretched arms and large upraised hands, a similar figure riding a horse, a cockerel or chicken – sometimes poised on the apex of a hooked triangle, and a four-petalled flower. The Oirata refer to the pattern based on this combination of motifs as ku’da asa ma’maro – literally horse, chicken and the image of a human. The term maro refers to a human being or person while a ma’maro is a statue, an image or a picture of a human being (De Jong 1937, 255). Less common motifs include large and small birds, a creeping vine and an eight-petalled flower.

Our first example of a lau ma’maro was woven about 35 years ago by Sus Serain, now aged 65, from the Soho-Radi house of the highest ratu or noble caste of the Hano’o clan of Oirata Timur.

A lau ma’maro woven by Sus Serain from pada Hano’o of Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

The second example was woven around 45 years ago by Oktavina Serain, a noblewoman from the Soho-Radi house of the highest ratu or noble caste of the Hano’o clanor pada of Oirata Timur. Born in 1948, she wove it in the years before she got married at the age of 28 in 1976.

A lau ma’maro woven by Oktavina Serain, from the Hano’o clan or pada of Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

The third example is naturally dyed but has no provenance.

A lau ma’maro that is completely naturally dyed. Richardson Collection

A lau ma’maro in the Peter ten Hoopen collection has been misattributed to the island of Luang (2018, 513).

In the past, skirts with such anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures were restricted to the marna or nobility and therefore have a higher status than ceremonial skirts like the lau ahi leu ru that are decorated with patterns that were not restricted in a similar way. Once again, the colour of the main ikat band can be indigo blue, morinda brown or kusambi purple, depending on the preference of the weaver. None of these colours conveys a higher status than the others.

A lau ma’maro worn in Oirata Barat decorated with a pair of songbirds in a bower, possibly a rare sign of European influence

Both the lau ahi leu ru and the lau ma’maro are appropriate for a wedding or other type of celebration, but are too decorative for a funeral. These two types of Oirata lau are very similar in appearance to the lau upu lakuwaru of Lautem District.

The Lau Metleur Sorot

The very high-status, ceremonial lau metleur sorot is named after the pattern of the main ikat band, which belongs to the noble (ratu) lineages of Lewelipa and Lewedalu, which belong to the clan or pada of Pamodo. Metleur is the place where they live in Oirata Timur and sorot means a picture – so metleur sorot is the Metleur pattern, named after their home. In the past, such designs were restricted to the marna, the tribal aristocracy of that clan.

The example in our collection was woven almost exactly 100 years ago by Ibu Worilina who belonged to the noble (ratu) house or kodo of the Pamodo clan or pada in Oirata Timur. Never baptised, she was known by the pagan name she was given at birth, which means ‘cold oil’. Her eldest daughter, Welmina Lewedalu, was born in 1917. The lau was acquired from the weaver’s great granddaughter.

Lau metleur sorot woven almost exactly 100 years ago by Ibu Worilina from the noble house of the Pamodo pada in Oirata Timur. Richardson Collection

A lau metleur sorot from Oirata with a blue ikat band. Image courtesy of Ishak Gideon Lewelipa

The anthropomorphic figure within the band is called ku’da ma’maro – literally horse and image of a man. The angular wave pattern is similar to that appearing on the Oirata mauwesi lau collected by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar in 1914 and now held by the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Köln, inventory number 36581 – see above.

Return to Top

The Meher Tubeskirt

The Meher call a woman’s skirt a ma’weke homnon, literally ‘woman’s skirt’. Today the homnon is always worn with a rain or kebaya blouse, usually coloured.

We already mentioned that the Oirata linguist Nazar Nazarudin pointed out that the term homnon seems to have been derived from the Meher word for dark or black – mohon. It may also be possible that the prefix hom is derived from an ancient Kisaric verb meaning to weave. In Wakatobi in southeast Sulawesi - from where the Kisaric languages are thought to originate - the word for to weave is homoru, while the related Tetum word is homan (Hull 1998, 144). If correct, homnon would literally mean ‘to weave black’.

A fine Kisar homnon photographed by the authors on Leti Island in 2004

Surprisingly none of the very early visitors to Kisar mentioned the local name of the woman’s sarong. The first was Johann Gerard Friedrich Riedel, who visited in 1882 and described the Meher skirt as a homonon. Was this how the term was pronounced at that time or simply a misunderstanding? He wrote that the women of Kisar (specifically the Meher) wore two types of sarong, a short homonon Jotowawa [sic] that hung down to below the knees and a longer homonon kapaije that extended over the shoulder (Riedel 1886, 424). Riedel also mentioned a graceful homonon awahe, which was used for trade – the word awahe being Meher for cotton yarn. The women generally went bare-breasted but donned a kebaya blouse for formal ceremonies (Riedel 1886, 401). Sadly the Norwegian ethnologist and collector Johan Adrian Jacobsen, who arrived just six years later, failed to record the local term for a women’s sarong, despite providing the name for the associated belt!

A woman on Kisar wearing a long ‘homonon’ fastened with an ehe palm strip belt

(Jacobsen 1896, 133)

Remarkably the German ethnographer and researcher Wilhelm Müller-Wismar, who arrived in 1914, seems to have been the only visitor to record the currently used term homnon. Unfortunately he appears to have applied it equally to the lau of the Oirata. Since then the term homnon seems to have been indiscriminately applied to all sarongs from Kisar Island, whether Meher or Oirata (Khan Majlis 1984, 294; Maxwell 1990, 56-57 and 100; Khan Majlis 1991, 287).

The Meher weavers we interviewed on Kisar said that there was no special sarong called a homnon Yotowawa. This term applied to every Meher sarong woven on Kisar Island. There was also no differentiation today between a long sarong and a short one. In the past, shortages of cotton may have been the reason that weavers had to produce sarongs that were shorter than normal.

Today, the Meher weave just two types of ceremonial sarong:

- homnon kililina with a main ikat band containing a row of rectangular motifs, some enclosing complex hooked diamond motifs and eight-pointed stars

- homnon rimorimori with a main ikat band containing a combination of anthropomorphic, zoomorphic and floral motifs.

Clearly Peter ten Hoopen is incorrect in asserting that “Meher ikats only rarely have anthropomorphic or zoomorphic motifs” (https://www.ikat.us/ikat_138.php accessed 24.01.1-19). On the contrary, the Meher use anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs widely, possibly more so than the Oirata.

The layout of both types of sarong seems to be strictly proscribed. The Meher, like the Oirata, have woven the same ancestral patterns from generation to generation and very rarely create new designs, although they may have done so in the past.

The Everyday Homnon

Although they do not make them today, the Meher, just like the Oirata, must have made simple everyday sarongs decorated with narrow alternating plain and ikatted stripes. In the 1840s Dr Wolter van Hoëvell, who seems to have limited his attention to the Wonreli area, observed that the women of Kisar made cotton sarongs for their own personal use that were very strong. Some were taken to Wetar and Romang for barter (1855, 227).

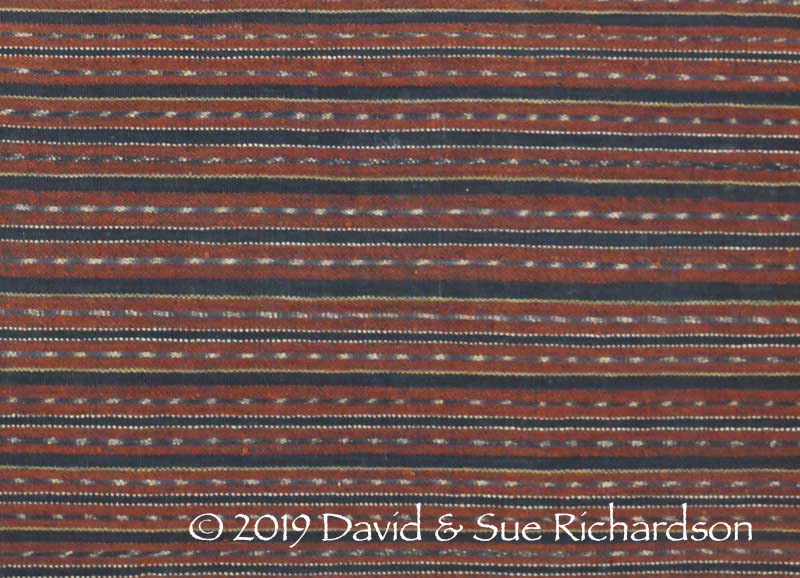

One possible example is held in the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Collection in Rotterdam. It has narrow alternating stripes of simple indigo ikat and plain chemical red, broken by a few warps of pre-dyed commercial cotton. The simple alternating chevron pattern is typically Meher.

Above and below: a simple homnon with no provenance, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Collection, inventory number RV-1348-72 (Creative Commons Licence)

Heinrich Kühn may have collected a simple everyday Meher sarong in 1888, which is now held in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum Collection in Köln, inventory number 12743. It is only listed as a homnon from Kisar so we cannot be completely certain that it is Meher. Woven from a combination of hand-spun yarns and commercial two-ply synthetically red-dyed cotton, the quality of the binding is poor. At only 92cm long, it is quite short – most ceremonial sarongs range from 130cm to 160cm in length.

A homnon collected by Müller-Wismar in 1914

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 12743

The Homnon Kililina

The homnon kililina is named after the pattern in the main ikat band called kililina, which our Meher informants say has no meaning. Interestingly on Tanimbar they had a motif with the similar name of kilunilaä, which meant large flowers (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 274). The Meher also call the pattern weku wekur, an undefined term similar to the phrase ‘wunukue klin weku wekur’ given to the same decorative band by Jasper and Pirngadie (1912, 274).

A woman wearing a simple Meher homnon kililina around 1925.

(Tropenmuseum, Creative Commons Licence)

According to our Meher informants, individual motifs are called roré. The hooked diamond motif is called rara’a opul, meaning crab shell, while the hooked diamond with four large outer hooks or scrolls is called roré leu. The hooked diagonal cross (like four v-shapes packed together) is called roré deul. There is also a motif called roré liweliwere. The eight-pointed star is awi kawi melai (also written awu kawi melay). The tumpal motif is called an ujung tambak or spear by some weavers and a loron, meaning ending, by others.

Motifs in the homnon kililina pattern, from the left: roré leu, awi kawi melai, rara’a opul, awi kawi melai and roré deul.

In the small ikat bands a small spot is called an eti, while a brown chevron is called a woyali. The red stripes are called awah ma’mere, the yellow stripes awah ma’mare and the green stripes awah mo’moke.

The homnon kililina can be worn for a wedding or other celebration, but it is inappropriate for a funeral. It has lower status than a homnon rimorimori.

It is no longer possible to find old homnons on Kisar Island with known provenance. Consequently all of the homnons in our collection lack any history.

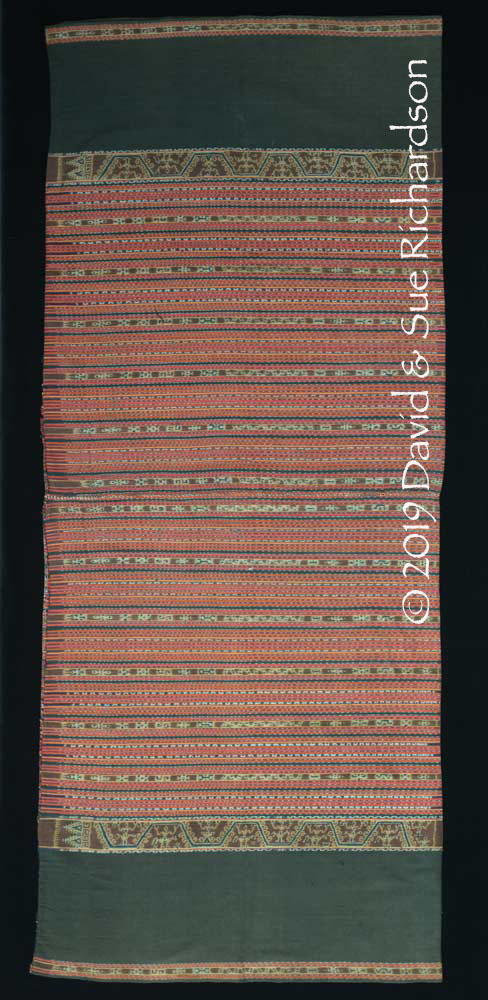

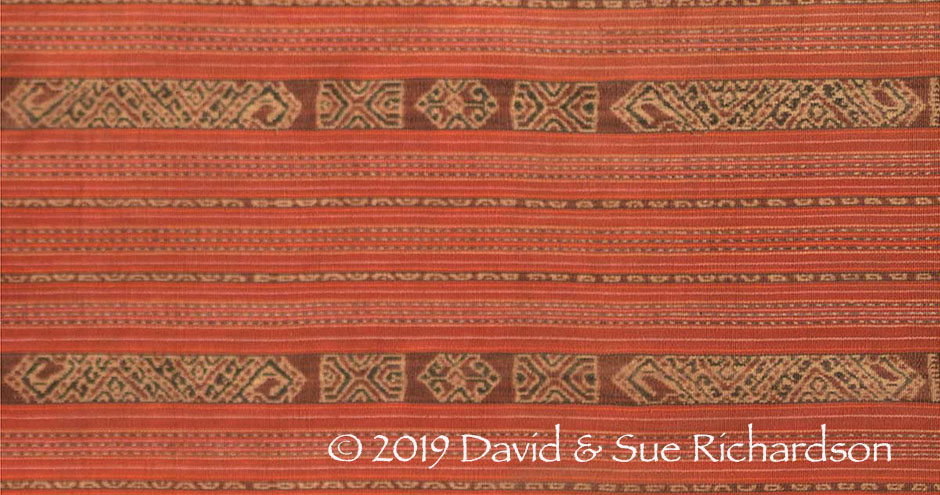

An old, completely naturally dyed homonon kililina woven from commercial cotton. No provenance. According to our Meher informants, the design is typical of that produced in the hamlet of Yawuru. Richardson Collection.

A homonon kililina, woven from commercial cotton and dyed with a mixture of natural and synthetic dyes. No provenance. Richardson Collection.

A homonon kililina, woven from commercial cotton and dyed with a mixture of natural and synthetic dyes. No provenance. Richardson Collection.

A short homnon kililina woven from commercial cotton by Marta Letelay in dusun Yawuru in 2016-17. Richardson Collection

A homnon kililina (with seam unpicked) acquired prior to 1940

Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, inventory number 1772-1193, Creative Commons Licence

The Homnon Rimorimori

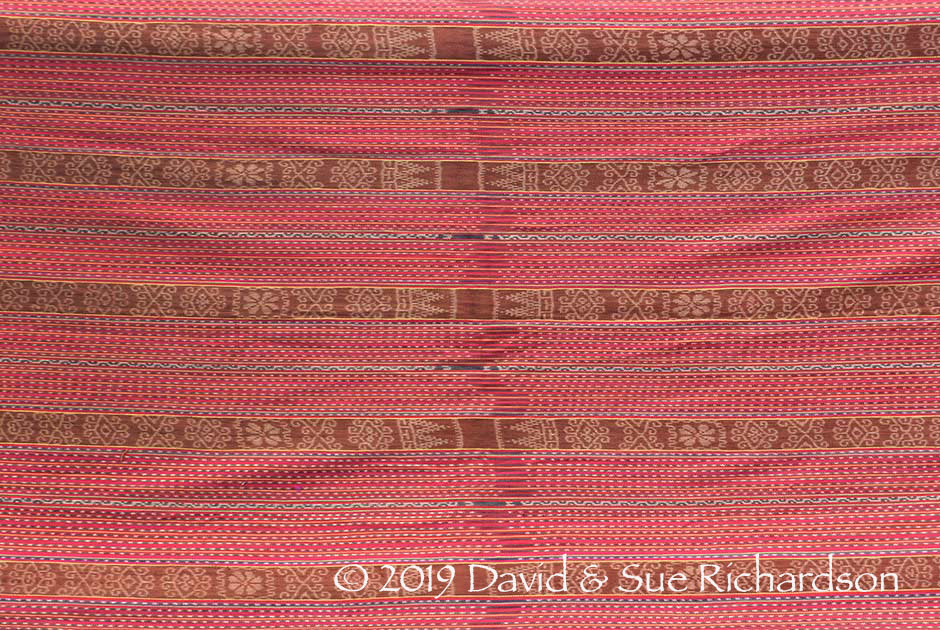

The homnon rimorimori is decorated with anthropomorphic, zoomorphic and geometric figures. Rimori-mori is the Meher term for a person (Taber 1993). Weavers describe the anthropomorphic figure as a manusia, bahasa Indonesian for a human. However they interpret the figure as a man dancing. This class of sarongs has the highest status because in the past the use of those motifs was restricted to the noble families or marna.

Only one informant used the term rimanu for this pattern, which they described as a mixture of people and chickens.

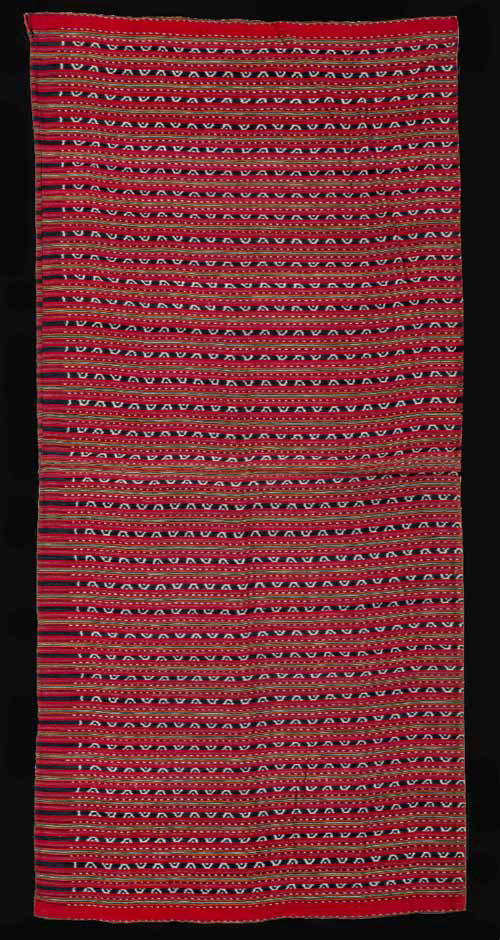

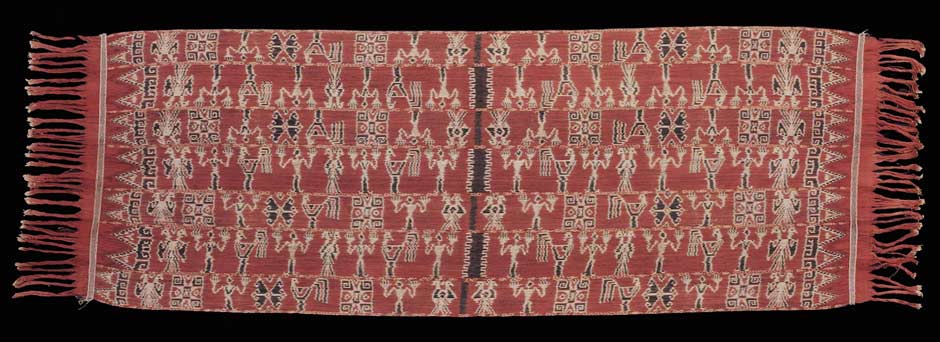

A naturally dyed homnon rimorimori (with seam unpicked) collected before 1942

Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Inventory number 6207-173

Above and below: two homnon rimorimori woven from commercial cotton, the first completely naturally dyed. No provenance. Richardson Collection

The following two examples are also naturally dyed, but the indigo appears grey rather than blue, suggesting that it has been boiled.

Above and below: two naturally dyed homnon rimorimori. Private Collections, Bali.

A rather crude homnon rimorimori acquired prior to 1940

Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, inventory number 1772-1191 Creative Commons

One unusual homnon rimorimori in our collection is decorated with double bands of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs. It was acquired on Timor in 2003 with no provenance.

A naturally dyed homnon rimorimori with wide double bands of ikat

Richardson Collection

The Meher community at Wonreli still consider it obligatory for a bride to be married wearing a homonon decorated with anthropomorphic figures (Finesso, Wahyudi and Sadju 2013). The sale of such sarongs is supposedly forbidden, although a large number have come to market over the decades.

Although textiles were once a minor component of the bridewealth exchange, the Meher have no concept of a bridewealth sarong. However sarongs did once play a role as gifts in certain situations. Following the birth of a boy, the father – but not the mother – was given several beautiful sarongs from the relatives of the mother – but only if the parents came from different villages. If the newborn child was a girl, the mother received a special lance with a long barb from the father's side (Jacobsen 1889, 134 and 215).

In the past, according to the East German anthropologist Theo Körner, when a Meher woman on Kisar Island died she was washed by her relatives and dressed in two sarongs before being laid with both her hands resting on her body (Körner 1936, 5). However when a woman from the island’s nobility (the marna) died, her nails and hair were cut and she was wrapped in cloths until her body resembled the shape of a doll.

Riedel had earlier reported that when a (Meher) person died on Kisar, their body was bathed and wrapped in a variety of textiles – two Kisar sarongs, a length of white linen, a snikir or shawl and a patola sarong – before being placed in a coffin or wrapped in mats (Riedel 1886, 420).

Miscellaneous Homnons

It is hard to find a Meher sarong that does not conform to one of the above three categories.

Although we cannot be certain, a sarong with its seam unpicked acquired by the Koloniaal Museum in 1920 and labelled Kisar appears more likely to be Meher than Oirata. Indeed it is so different that one questions whether it really is from Kisar?

An unpicked sarong labelled as Kisar. Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-A 5279. Creative Commons Licence

Another unusual homnon that looks far more Meher in appearance has no plain terminal bands, its main narrow bands of ikat being flanked by a pair of plain black bands instead.

An atypical homnon with no plain terminal ends. Private Collection, Bali.

The most unusual exception is an atypical homnon decorated with four central bands of anthropomorphic figures, chickens, double headed eagles, and eight-pointed stars. The motifs are clearly Meher in origin. The homnon was apparently gifted to M. C. Schadee, who was the Dutch controleur for Aru, the Kei Islands, Tanimbar and the Southwest Islands at the turn of the twentieth century. One wonders if this was a special high-status sarong gifted by the Raja of Kisar to his high-ranking Dutch visitor.

An unusual homonon (with seam unpicked) gifted to M. C. Schadee in the early twentieth century. Former Anthony Granucci Collection.

Return to Top

The Term Rimanu

The term rimanu (rimanoe in old Dutch) was first used by Jasper and Pirngadie to describe a set of special motifs from the Ambon Archipelago that were restricted to the nobility (1912, 8, 274 and plates 26 and 27).

Rimanoe is a pattern that can only be worn by monarchs and other important persons. Those who still wear this forbidden pattern may, according to ancient adat, be killed by those who are entitled to the rimanoe [pattern] according to their birth or rank (1912, 274).

They added that on Wetar Island, local legends recorded that the misuse of these patterns in the past had often given rise to bloody wars, reducing the size of the island’s population. As a consequence, the islanders swore an oath to henceforth use only textiles imported from elsewhere (1912, 8, 274).

Many of the other terms reported by Jasper and Pirngadie in 1912 for the patterns and loom parts of the Meher-speaking majority are the same or similar to those used today, so we must give the term rimanu some credence.

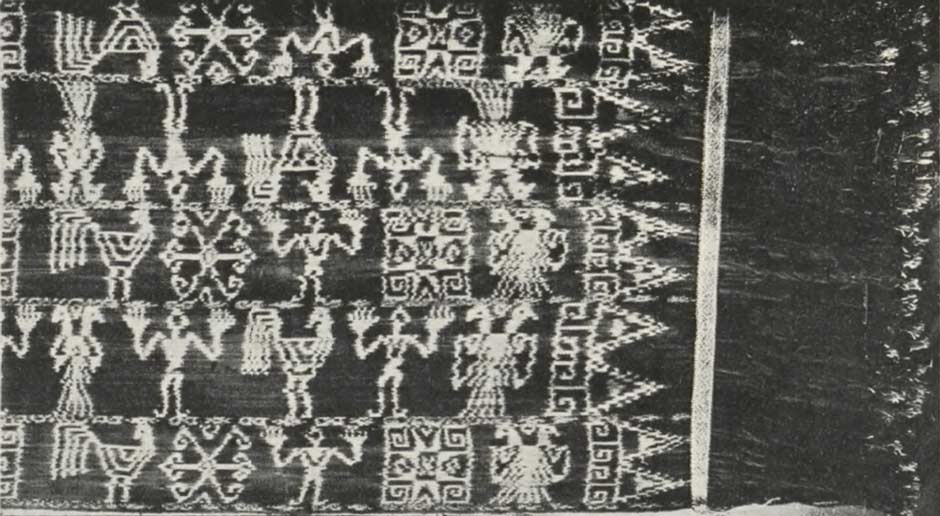

The rimanoe motifs illustrated by Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, plates 26 and 27

Yet there is no other original source referring to the use of the term rimanu/rimanou in the South Western Islands. Since 1912 the term rimanu has been reiterated, especially in relation to the textiles of Kisar, by a number of collectors and writers who have never visited the island (Gittinger 1979, fig. 151; Khan Majlis 1984, 121; de Jonge and van Dijk 2012, 126, 132, 133 and 136). As such it has become an established textile term.

The rimanu patterns illustrated by Jasper and Pirngadie are exactly the same as those that appear in the main decorative band of the Meher homnon rimorimori (but differ from those found on the Oirata lau ma’maro). We were therefore surprised to find that the weavers we interviewed among the Meher community (and also the Oirata) had never heard of Jasper and Pirngadie’s term rimanu. Only one person, a man, described the Meher rimorimori pattern as ri manu.

We have previously mentioned that the term rou once referred to a restricted motif while manu generally means a chicken, so one possibility is that a roumanu or rimanu might once have described a chicken motif restricted to the aristocracy. Over time, its meaning might have been extended to cover the other zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures.

The fact that it is not used by Meher weavers on Kisar today has led us to question whether the term rimanu was ever widely used on the island, especially as Jasper and Pirngadie used the term in the context of events on Wetar not Kisar. Today the modern term for a motif is a roré in Meher and a ru in Oirata. The once restricted anthropomorphic/zoomorphic pattern used by the Meher is called rimorimori, while the similar pattern used by the Oirata is called ma’maro. As such we think it is no longer appropriate or wise to use the term rimanu.

Return to Top

The Male Loincloth

Today the Oirata call a man’s loincloth a mal. However in 1937 Josselin de Jong listed the word as a māl or māla, the macron indicating the presence of a long vowel (De Jong 1937, 254). More recently Engelenhoven has also used the term mala (Engelenhoven 2010a, 73). De Jong also listed the term ulawara weltaru - literally waist or loin cover (1937, 281 and 288). This is no longer used today.

The Meher call a man’s loincloth a kornele he. This term caused much confusion among early visitors to the island, who described it as either a kornele or a he, or in one case a kornelhe.

These two terms, mal and kornele he, apply whatever material the loincloth is made from.

The most commonly used terms for a loincloth used by European visitors to Kisar in the nineteenth century were the early Malay expressions tjidako and tjidaki, equivalent to the modern tjawat or cawat. Some writers consider the latter to be an inappropriate term, because it also describes a diaper and a chastity belt.

The earliest known man’s loincloth was collected on Kisar by Heinrich Kühn in 1888. Unfortunately it is unclear whether it is Meher or Oirata. It is an exceptionally fine single warp-striped length of cloth woven on uncut continuous warps and has obviously never been worn. It was made from three types of cotton yarn: extraordinarily fine hand-spun single-ply, commercial single-ply and commercial two-ply. The colours of the warp stripes are chocolate brown, light brown, purple, eau-de-nil, orange, yellow, bright blue and black, while the weft is grey. It contains narrow ikatted indigo stripes with a simple dashed design.

Man’s loincloth, width 64cm, circumference 201cm

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 12690

Return to Top

The Bark Loincloth

Loincloths made from barkcloth were once common for men across all of the South Western Islands and the wider Maluku region.

As early as 1825, Lieutenant Dirk Kolff found them worn on nearby Damar Island (Earl 1837, 369-370). The Dutch Protestant minister Dr Wolter van Hoëvell found that men on Kisar wore nothing but a loincloth for everyday wear during the 1840s, describing it as a tjidaki (Hoëvell 1855, 227). He did not record what they were made from, although he did note that the men on neighbouring Leti wore just a crude barkcloth loincloth. H. C. von Eijbergen was saddened to see that the mestizos of Kisar, some with white skin and blonde hair, had become so poor that they worked in their gardens wearing only a ‘tjidako’, just like the native Alfurs (Eijbergen 1864b, 137).

When Hoëvell’s nephew, Baron van Hoëvell, visited Kisar in 1887 he ignored the costume of the natives, restricting his comments to the mestizos. However on neighbouring Leti Island he noted that the men wore nothing but a narrow homemade tjidako, which he said they called a rēwĕ (1890, 213).

In most cases the term tjidako was applied to a loincloth made from barkcloth, which was considered primitive and linked to poverty. Thus Philippus Pieter Roorda van Eysinga wrote that the Alfurs, the native people of Maluku, went completely naked apart from a tjidako made of bark fibre (1841, 181). J. B. J. van Doren described how the Alfurs on the northeast coast of Seram produced their tjidako by cutting a strip of bark from a certain variety of tree, which might be up to 40 feet in height, before diligently beating it gently with hammers (1856, 190). They then impressed it with figures and stripes in various colours.

At the same time the term was also applied to loincloths made from fabric. Johannes Olivier, who visited Ambon in the 1820s, wrote that the Alfurs of Maluku wore a tjidako made of white, blue or blended cotton (1840, 8). Abraham Jakob van der Aa found the Alfurs of Aru Island wore a tjidako, similarly made from white, blue or blended linen (1839, 344).

The Leiden geologist Professor Karl Martin described a native tjidako on Seram in the late 1800s as a narrow loincloth made from tree bark, beaten with notched stone beaters. On this island they were slightly rhombic in shape, with the widest part placed in the small of the back, and many were decorated with vegetable dyes. One example was made from two pieces 2.0 and 1.5 m long respectively (Martin 1894, 121). The two ends were completely wound around the body and were fastened with both ends hanging down low.

When the Siboga Expedition visited nearby Romang in 1900 it found that the male tjidako was worn everywhere. The loincloths were presumably made of barkcloth because they were decorated with figures and inscriptions, one example acquired by the expedition bearing its provenance in Malay: ‘This is the tjidako of R. A. Johannis and was manufactured by my sister W. Johannis and finished on the 31st day of the month of October in the year 1899’ (Weber van Bosse 1905, 297).

A rolled up tjidako from Seram acquired prior to 1920

Nationaal Museum von Wereldculturen, Amsterdam. Creative Commons

We do not know if the Kisar tjidako was decorated in any way. In 1888 Jacobsen saw slaves belonging to the orang kaya of Purpura on Kisar working in the fields wearing just a ‘pubic belt’ or loincloth, which he described as a kornele (he), werau or werneau (Jacobsen 1896, 117-118). At a celebration for the birthday of the King of Holland, the mestizos donned European clothing but the native ‘naked Kisarese’ ‘regarded a simple loincloth as an adequate piece of clothing’ (1896, 119).

A Kisar labourer or slave at Purpura dressed in a straw hat and apparently undecorated loincloth (Jacobsen 1896, 117)

A crude barkcloth loincloth from Kisar in the collection of the Rijksmüseums voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, is described as a kornele or he and was tied by means of a piece of rope at one end (Juynboll 1932, 106). A barkcloth shirt in the same collection (1348-57) is listed as a rain rarau.

A crude barkcloth loincloth, listed as a kornele or he.

Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, inventory number 1348-69 (Juynboll 1932, 106)

When Riedel visited Kisar in 1882, just six years before Jacobsen, he left us a different account of the Meher loincloth (1886, 423, 424, 426). He described two lower garments for a man:

- a waare loincloth (shaamgordel) made of Kisar cloth and

- a ‘kornelhe’ belly-band or abdominal belt (buikband).

He then added that the waare could also be manufactured from the bark of the fig tree (Ficus sp.). He failed to say what the kornelhe was made from.

The term waare is very similar to ware, the term used to describe a barkcloth or cotton loincloth on neighbouring Moa, Lakor and Leti (Riedel 1886, 383). Its use does not appear to be an error, since Riedel was clearly capable of distinguishing the subtle differences in terminology from island to island. Thus on Leti, Moa and Lakor he identified the ware cotton loincloth, the ware lilti barkcloth loincloth made from the lilti tree, the rewe cotton hip band that stretched down to the knees and the rewe petole patola belly band (1886, 383). Riedel also identified the waru on Damar, the warol on Babar and the ahas on Wetar.

Recently Engelenhoven has confirmed that on Leti Island, a loincloth is still called a ware (2010b, 149).

We gain some idea of the relative value attributed to the waare and the kornele he from their exchange value, because the Kisarese traded both types of loincloth to the Makassarese, Bugis and other foreign merchants who visited their island every year (1886, 426). One waare loincloth made from Kisar cloth was traded for a petole or patola sarong while one kornele he was traded for one head cloth (hoofddoek). Although no description of a patola sarong was given, it seems that despite its name it was not at all valuable. On Moa and Lakor one patola sarong was traded for one portion of wax (a lili) while a ware loincloth was traded for two portions of wax (Riedel 1886, 382). For comparison, a local sarong was traded for ten portions of wax and a man’s blanket for twenty.

This suggests that at the time of Riedel’s visit the Meher recognised two types of everyday male loincloth – perhaps one was wider than the other. The term waare must have become obsolete not long after, because Riedel is the only visitor to have used it. Only the term kornele he has survived to the present day.

Support for the idea of a second term once being used for the simple Meher loincloth comes from Jacobsen who, as mentioned above, referred to the loincloths he saw in the Meher district of Purpura as a kornele (he) or a werau or werneau.

Incidentally one of our Meher informants told us that, in the past, loincloths could not only be made from barkcloth but also from the bark of the banana tree. Today they are always made from a single length of warp ikat.

Return to Top

The Oirata Mal

As far as men are concerned, the traditional costume of the Oirata seems to have been abandoned some years ago. Consequently the Oirata male loincloth or mal is no longer woven or worn on the island today. At a local wedding ceremony, we were surprised to see that while the majority of women wore the traditional lau and kebaya, accompanied with a narrow sanikir shoulder cloth, every adult male was dressed in a western shirt and trousers.

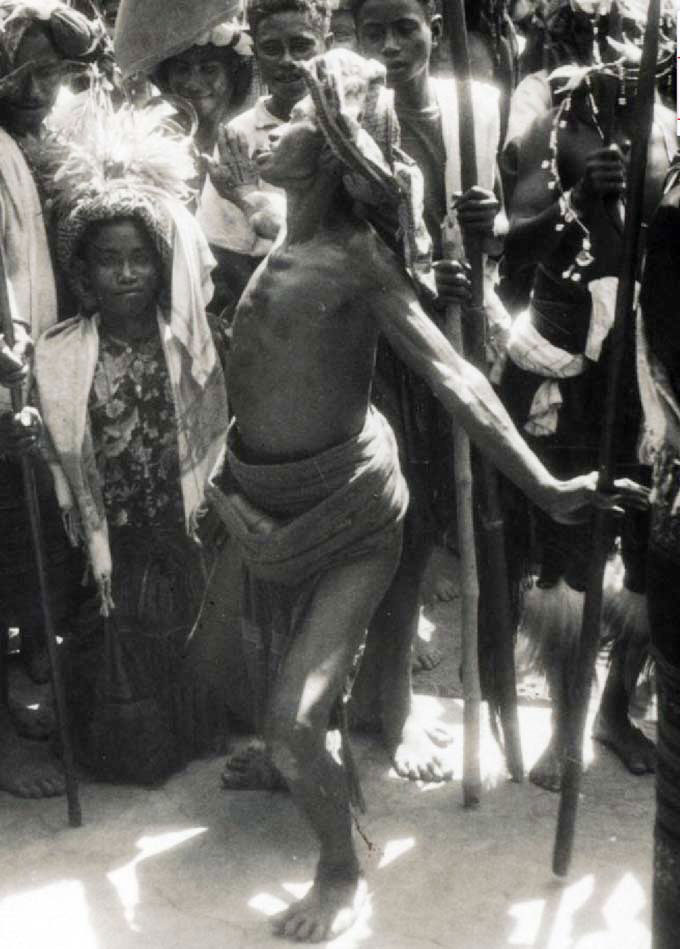

Apparently the mal was still worn by male dancers in the recent past but when the Oirata stage dance performances today they wear Meher loincloths because Oirata loincloths are not available, or are too valuable to wear for such purposes. The most common dances are the peuk victory dance and the war dance, which is known by the Oirata as the ita walu and by the Meher as the kerpopo.

An Oirata cultural group dressed in Meher kornele he

(Image courtesy of Ishak Lewelipa, Kisar Island)

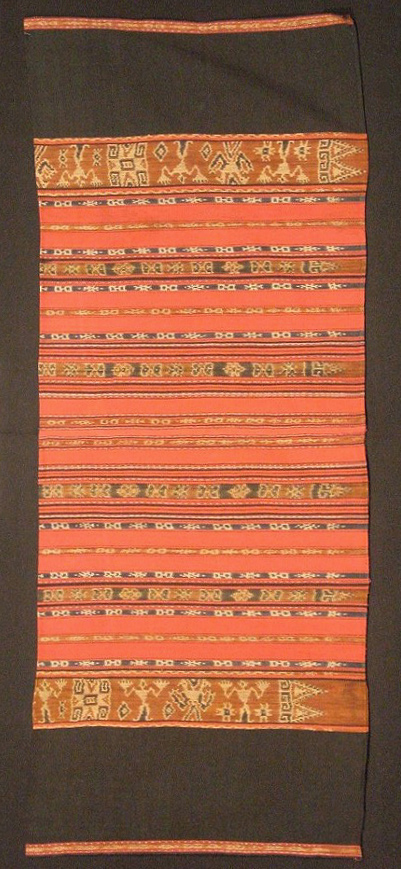

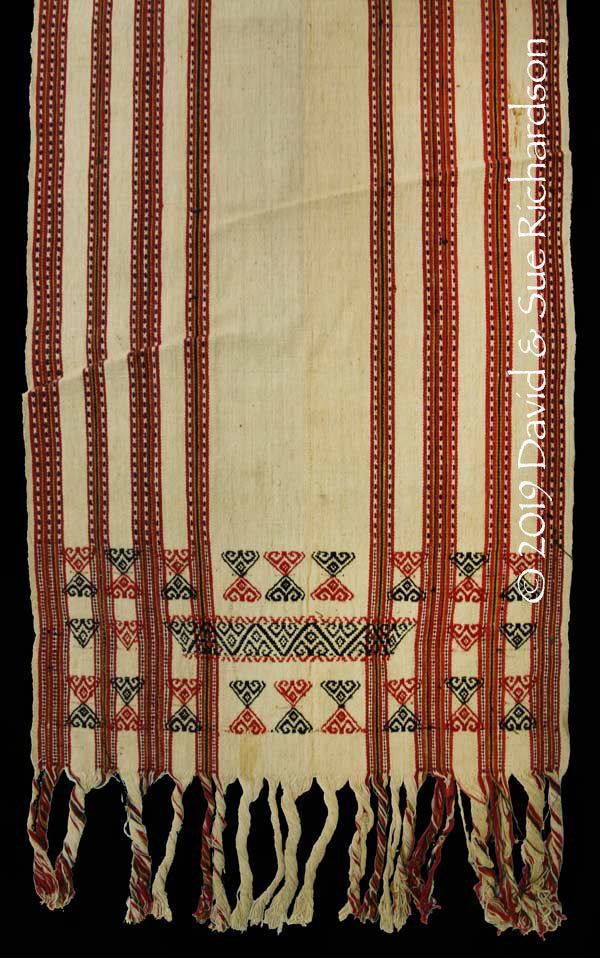

The mal was made from a single length of warp ikat decorated with narrow longitudinal bands of geometric hooked figures and floral motifs, along with pairs of terminal tumpals. The Oirata style of motif has rounded rather than angular hooks. These narrow bands were separated by narrow alternating stripes of plain red and simple indigo-dyed ikat. The ends were finished with a lateral band of twinning and a twisted fringe.

An example dated around 1900 was collected by Müller-Wismar in 1914. Described as a loincloth for a warrior, it was labelled a niala or an irä - the terms used for a more elaborate Oirata ceremonial loincloth (see below).

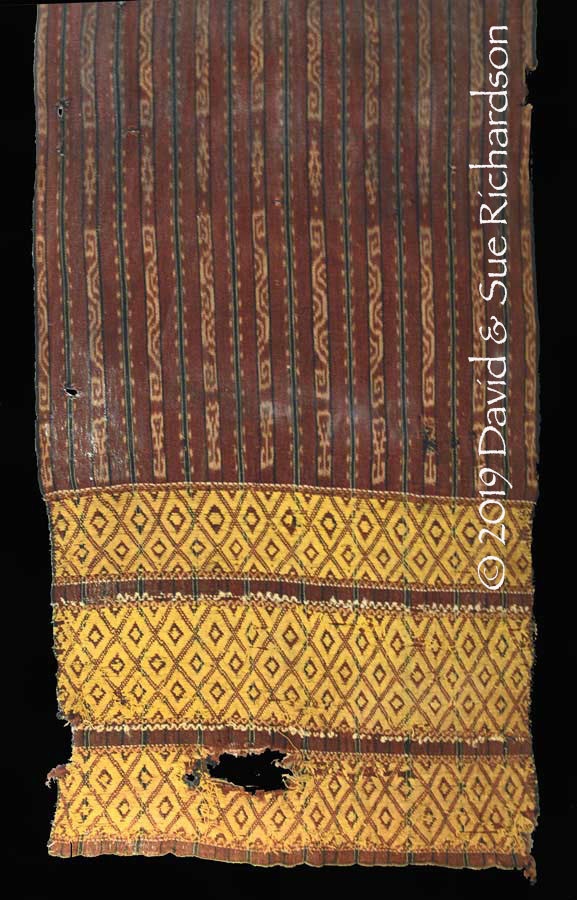

A mal from Oirata woven from naturally-dyed hand-spun cotton, width 28cm, length 216cm.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36585

Two more naturally-dyed mal woven from hand-spun cotton in the Richardson Collection are much wider and have a more elaborate ikatted pattern. However they lack the wide end decoration of a ceremonial loincloth. The first is 300cm long and 70cm wide, while the second is 302cm long and 79cm wide.

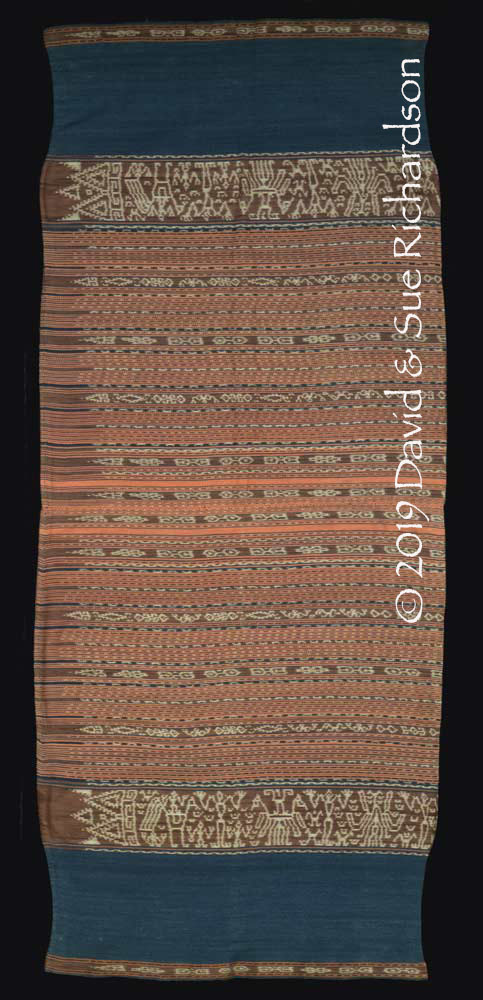

A mal from Oirata woven from naturally-dyed hand-spun cotton, length 300cm.

No provenance. Richardson Collection

Another mal from Oirata woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton, length 302cm.

No provenance. Richardson Collection

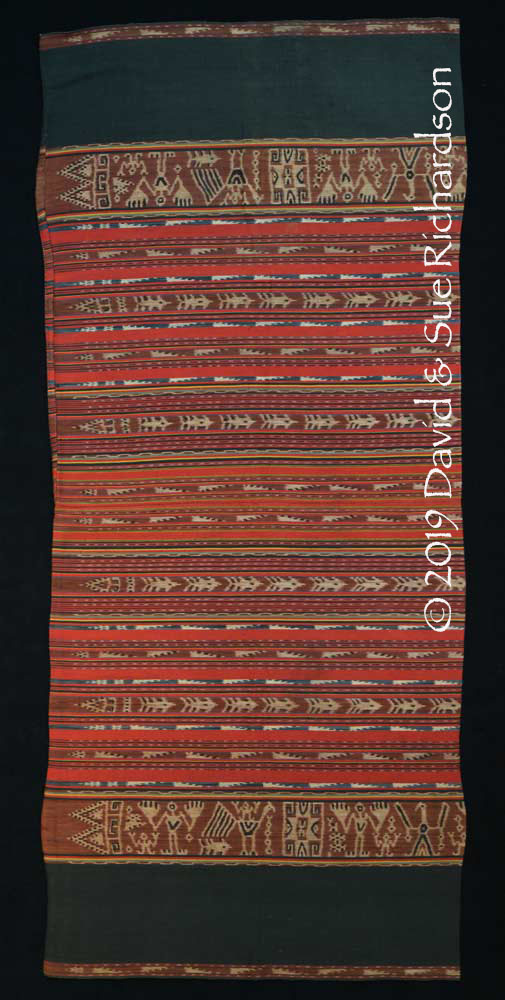

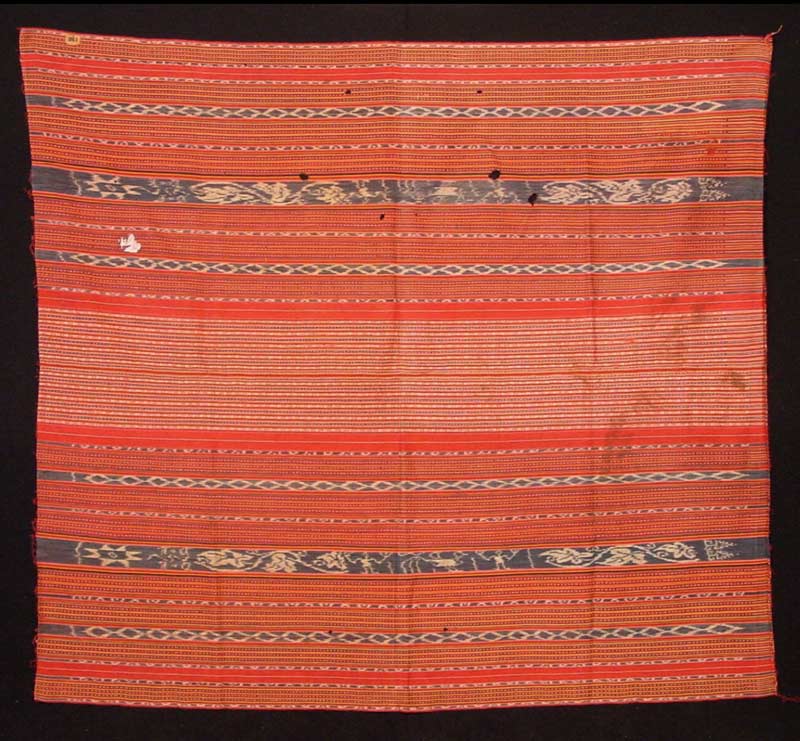

A third Oirata mal collected on Timor in the 1980s was woven from commercial cotton that had been dyed with a combination of indigo, morinda and synthetic red dyes. It is 271cm long and 51cm wide.

A very fine mal from Oirata collected in Timor in 1985, Woven from commercial two-ply cotton, length 271cm. No provenance. Richardson Collection

Detail of the lower end of the above mal

Above: An old Oirata mal that was woven 50 to 60-years-old. Private Collection, Oirata Timur. Below: A close-up of the narrow bands and stripes

A mal belonging to a family at Oirata Timur

A man from Oirata Barat demonstrating how the mal loincloth is worn.

This style of wearing the loincloth is exactly the same as that observed by Josselin de Jong when he visited Oirata Timur at the beginning of 1934. The loincloth is folded and wrapped twice around the upper hip with one end passing from the back, between the legs. Its decorative end is pulled up at the front and folded over the top of the wound loincloth and then arranged like a small apron.

Noblemen from the Hano’o clan of the Oirata dressed in mal and shoulder cloths in 1934

(Josselin de Jong 1937)

Return to Top

The Meher Kornele He

The Meher loincloth or kornele he is still being actively woven today and is used by dancers in the local cultural group Sanggar Seni dan Budaya.

A Meher dancer dressed in a kornele he loincloth with a sirih pinang basket tucked into a fold. Before 1936. Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence

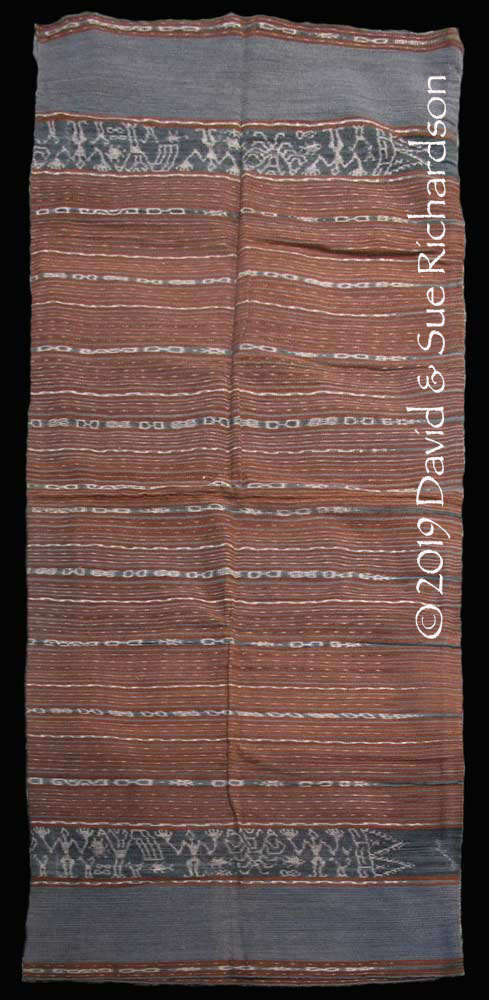

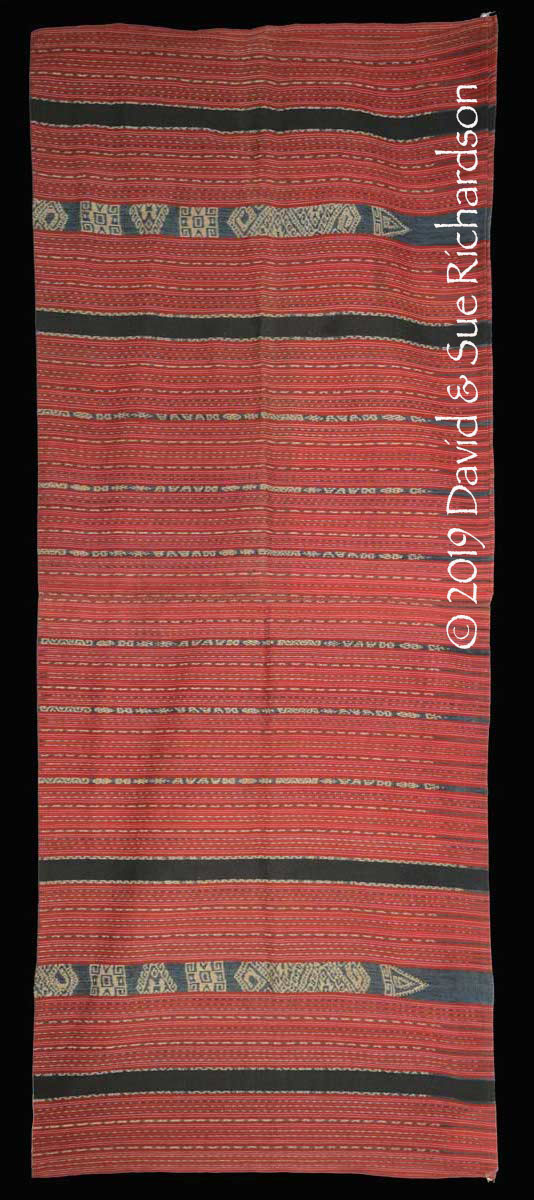

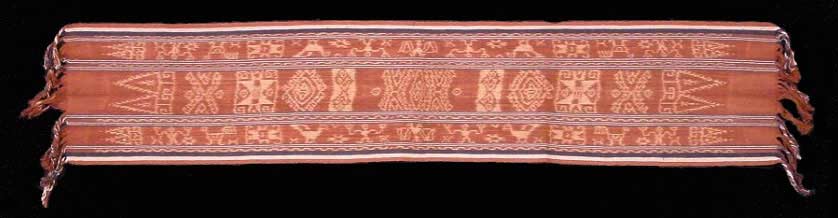

A kornele he woven from commercial cotton, length 284cm. No provenance.

Richardson Collection

Above and below: A newly woven kornele he at Yawuru

Like the Oirata mal, the kornele he is made from a single length of warp ikat decorated with narrow longitudinal bands of geometric hooked motifs with terminal tumpals, separated by narrow alternating stripes of plain red and simple indigo-dyed ikat. The ends are likewise finished with a lateral band of twinning and a twisted fringe. The Meher loincloth is easily distinguished from the Oirata loincloth because the motifs and their sequence in the main ikat bands are always very proscribed. They contain the same repeated arrangement of motifs: a small hexagonal-shaped figure flanked by square-shaped diagonal crosses and longer zigzag motifs with pointed ends containing angular hooks.

Details of the ikat motifs on the Meher kornele he

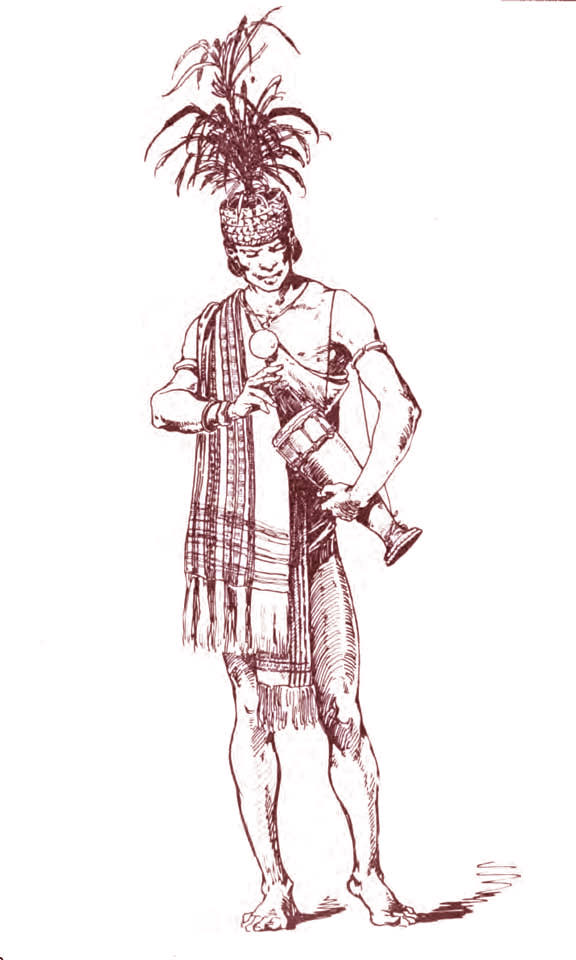

A simple version of a cotton kornele he was roughly sketched by Gaillard for Johan Jacobsen and published in 1896 (126). It appears to have been worn by a local warrior from Wonreli who Jacobsen encountered outside his hut. The relatively narrow loincloth is medium-length, striped and finished with a narrow lateral band at the end, patterned with geometrical motifs, and a gathered terminal fringe. It was wrapped around the hips and a decorated end hung in front half way down the thighs. Frustratingly Jacobsen did not record its name, but he must have considered it to be a fine textile since he described it as a product of Kisar’s ‘blooming weaving industry’ (130 and 132).

A fully equipped Meher warrior dressed in a narrow cotton loincloth

(Jacobsen 1886, 131)

Today the kornele he is no longer worn by local men, even for formal occasions. It is only donned by local dance groups for staged cultural performances.

Return to Top

The Male Ceremonial Loincloth

According to earlier visitors, Kisar noblemen and warriors also wore a high-status ceremonial loincloth. They probably became obsolete several generations ago. Today our Oirata and Meher informants have no memory of such a garment.

Unfortunately the historical accounts are far from clear, bewildering us with undefined terms such as loincloth (schaamgordel), bellyband (buikband) or hip band (heupband). Jasper and Pirngadie provide the only clear-cut description of such a garment, the one used by the Meher community (1912, 275). It was quite different from an everyday loincloth because it could only be worn by a prominent village or clan chief on special festive occasions. Called a warpitare, it had fringes and was worn in a special way.

Wilhelm Müller-Wismar used not one but three terms to describe the high-status Kisar ceremonial loincloths that he collected on Kisar in 1914 – niala, irä and warpitare. Unfortunately he did not identify which terms were Oirata or Meher. However since it is clear that warpitare was the Meher term, we must assume that the Oirata terms for a ceremonial loincloth were niala or irä.

The Oirata Ceremonial Loincloth

It is possible that a niala was an Oirata warrior’s ceremonial loincloth because in the Oirata language ni means to tie and āl or āla means a battle or war. Perhaps the irä was the civilian version worn by clan or village chiefs.

Unfortunately the elderly Oirata weavers that we interviewed had never heard of either term. There seems to be no folk memory of such a garment. For them the term ‘Ira’ refers to one of the three tribes or pada of the Oirata Barat (the Ira Ara).

Müller-Wismar collected two ceremonial loincloths on Kisar Island (Khan Majlis 1984, 292 and 293). They are very similar and are described as loincloths worn by noblemen to important festivals. They are both woven from extremely fine hand-spun cotton and each have eight narrow bands of indigo and morinda-dyed warp ikat, alternating with plain indigo stripes. Both are finished with elaborate end sections composed of lateral bands of geometric motifs woven in continuous supplementary weft. Both loincloths are dated around 1900 and are confusingly labelled as not only niala or irä but also warpitare. The second was recorded as being acquired from Oirata, implying that the first was from Oirata as well.

A niala or irä from Oirata, width 33.5cm, length 324cm.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36582

A niala or irä from Oirata, width 31cm, length 288cm.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36583

Note that Khan Majlis mistakenly identifies these ceremonial loincloths as having inventory numbers BK 491 and BK 492. However the latter are relatively narrow belts collected from the Oirata and are labelled as hita or hitilirrati (Khan Majlis 1984, 120 and 292).

Both of these ceremonial loincloths are similar to an example acquired by the late Anthony Granucci.

An Oirata niala or irä ceremonial loincloth with eight narrow identical bands of warp ikat. Collection of the late Anthony Granucci

The Meher Ceremonial Loincloth

Jasper and Pirngadie were the first writers to refer to the Meher ceremonial loincloth, which they termed a warpitare. It was a luxurious high-status ikat textile which required a great deal of work to produce. It had a richly ikatted warp and broad bands of complicated ‘line patterns’ approximately half an el wide (roughly 35cm) at each end, woven using both a continuous and a discontinuous weft – hiwi and laär respectively. It had a fringe at each end (1912, 275-276). Only prominent village or clan chiefs could wear the warpitare for special festive occasions. The populace respected whoever did so. The cloth was worn in a special way – placed loosely over the right shoulder and then wrapped around the middle of the body before being left to hang loosely over the loins.

Wilhelm Müller-Wismar might have acquired a Kisar warpitare on Leti Island, where it was called a revä lällivu. According to van Engelenhoven (2004, 326, 432, 445), on Leti a réva is a belt, a vara is a loincloth and a vutu is a sash. This example was worn by a warrior and has been dated to approximately 1910.

Possibly a Meher warpitare from Kisar, width 44cm, length 303cm.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36661

The yellow supplementary weft is woven using very fine plied yellow cotton,

probably of European origin

It is not possible to be definite – we cannot rule out that this loincloth might be Oirata. However the narrow bands of ikat have been dyed with just morinda, the meander motif is curved whereas the Oirata equivalent is more angular, and the supplementary weft weaving is by no means as fine as it is in the Oirata examples shown above. The size and style is also very similar to that of two ceremonial loincloths depicted on a staged 1926 photograph of nobles or clan leaders from the Meher community standing in front of a picket fence on Kisar.

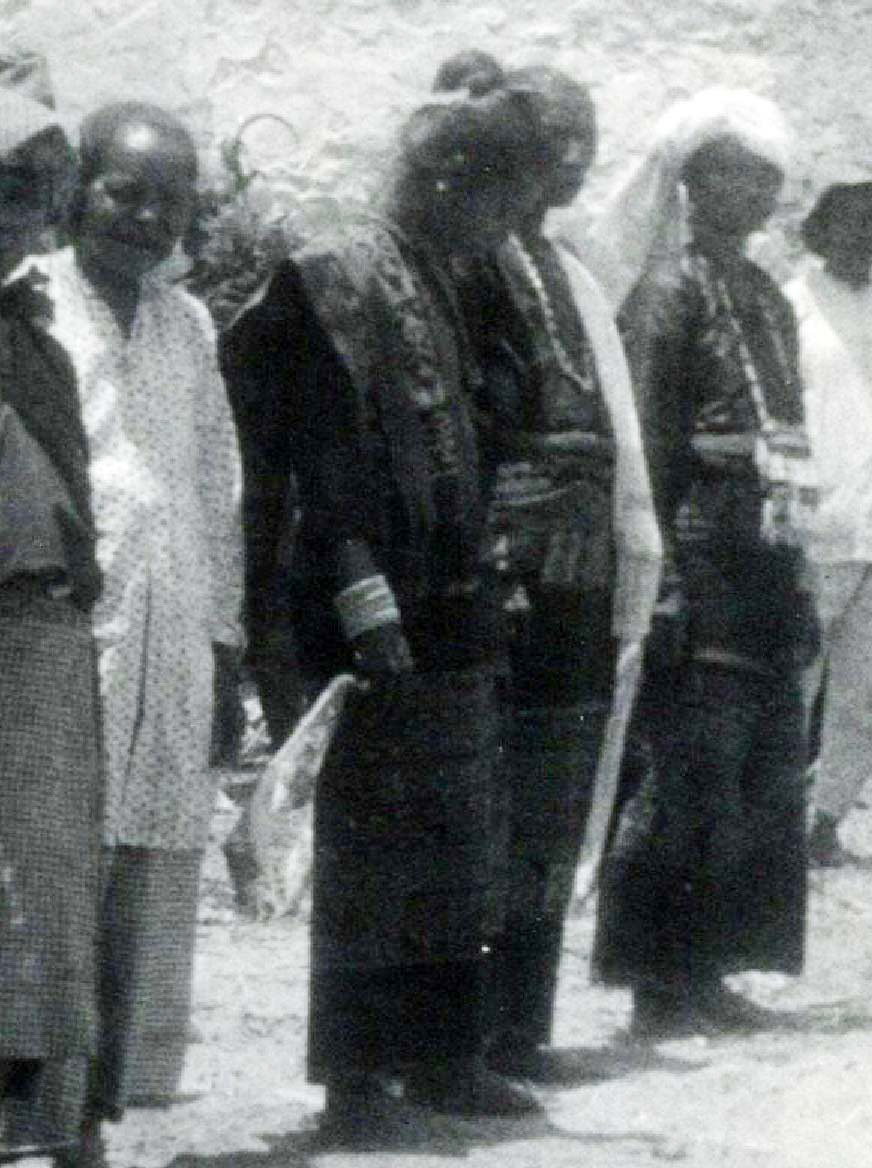

High-ranking Meher nobles wearing ceremonial loincloths. From the Indisch Wetenschappelijk Instituut, dated 1926. (Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence)

Another Meher warpitare with very similar bright yellow supplementary weft end sections is held in the collection of the Australian National Gallery, where it has been wrongly catalogued as a hita or hitilirrati and has been listed as being possibly Oirata. However the morinda-dyed warp ikat is decorated with motifs that are typically Meher. The ikat appears to have been embellished with hand-painted black detailing.

A Meher morinda-dyed warpitare, width 47cm, length 301cm.

Australian National Gallery, inventory number 1985.383. Creative Commons Licence

A different coloured warpitare was collected from Kisar in 1933 and is listed in the 1934 yearbook of the Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (139-141). It was described as a belt woven from local cotton, beautifully decorated with very large white ‘putjuk rebung’ or bamboo shoot motifs on a blue ground.

As already mentioned the use of such textiles was strictly restricted to the nobility. One of our informants, Julius Jonasz, was born into a noble family that was closely related to the royal family of Kisar. His grandfather had two wives, the first being his grandmother and the second the sister of the Raja of Kisar. One day his grandfather encountered a common man wearing a loincloth that was reserved for the nobility. He accosted the man, forcibly removed his loincloth and cut it into small pieces.

Return to Top

The Cloths for a Purka Priest

As in other parts of eastern Indonesia, local shamans on Kisar oversaw the cycle of customary rituals throughout the agricultural year. The Dutch referred to them as purkapriester or purka priests because they administered the important purka festival, celebrated for several weeks in the autumn under the nuna or morinda tree (Jacobsen 1896, 125). It involved singing and dancing throughout the day and night, with some dancers holding the beaks of sacrificed birds studded with nassa shells in their hands. Men and women danced separately or together, accompanied by ritual drumming, sometimes engaging in ‘sexual excesses’ on the dance arena. The festivities were interrupted by the mass sacrifice of pigs. The local name for a purka priest was leher marna or leher marna lalape, indicating that they belonged to the noble marna caste (Riedel 1886, 48; Jacobsen 1896, 125). Some were women.

Riedel observed one leher marna conducting a fertility ritual in a padi field some three to six months after the rice had been planted. He made an offering to the ‘earth goddess’, mahkarom mawahku (wahku referring to a seed or stone) by placing a cooked chicken, an egg and some sirih pinang in a hole in the centre of the cultivated field and following this with a prayer (1886, 48).

A leher marna with a drum and shouldercloth at the purka feast on Kisar

(Jacobsen 1896, 126)

Jacobsen illustrated a leher marna at the purka feast beating a small drum or kiwal. He was dressed in a warp-striped, light-coloured shouldercloth, a similar looking loincloth, and a feather headdress, and was wearing a disc-shaped neck pendant. Jacobsen termed such pendants lawang or mahe (1896, 124-125). Made of very thin brass, they had a diameter of 3 inches, and were engraved with fish or various triangles. Unfortunately he did not name the priest’s shouldercloth or loincloth.

The Museum Volkenkunde in Leiden holds two very similar early examples of such textiles. The first was acquired at some time prior to 1832, and the second prior to 1837 - the year the original Rijksmuseum was founded. It is possible that Dr. Maclot, G. van Raalten and A. Zipelius collected the first during the Natuurkundige Commissie geological survey of the South Western Islands in 1828. They have clearly never been used – both are just as they were taken from the loom with their unwoven warps still uncut. They have a broad natural plain cotton centre and single side bands, each composed of three narrow strips of complementary warp decorated with repetitive geometric motifs flanked by plain warp strips. The dyes are natural. It is not clear whether they are Meher or Oirata.

Two early examples of Kisar purka priest shouldercloths

Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, RV-1-131 and RV-1-132. Creative Commons Licence

Heinrich Kühn acquired a later example in 1888. Woven from hand-spun cotton it has a natural white ground and is decorated along each side with four narrow indigo blue ikat stripes flanked by red and black warp stripes. The ends are finished with a band woven in continuous supplementary weft. The red and black cotton is commercial. Brigitte Khan Majlis pointed out that this, along with a second textile in the collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum, was the same as that worn by Jacobsen’s purka priest – a white shawl with side stripes and brocaded end patterns (1984, 120). It is not identified as either Meher or Oirata, although the small embroidered stars are typically Oirata.

Cotton shawl (or loincloth) for a purka priest, width 45cm, length 264cm

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 12744

A fourth example was collected a quarter of a century later by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar – in 1914. Also woven from hand-spun cotton, it too is decorated along each side with four narrow stripes composed of simple rows of supplementary warp flanked by plain red, black and yellow warp stripes. The latter are made from commercial cotton. The ends are finished with three bands of red and black discontinuous supplementary weft. The cloth is recorded as being Oirata and is labelled a niala or irä for a priest at the annual purka fertility festival (1984, 293). These are the same terms used to describe an Oirata man’s high-status ceremonial loincloth. If we are correct in deducing that the niala was an Oirata warriors cloth, then perhaps these were called irä.

Cotton shawl (or loincloth) for a purka priest, width 43cm, length 242cm

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 36584

These few textiles demonstrate that the shouldercloth/loincloth for a priest may have undergone a process of change during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the increasing use of pre-dyed imported yarns. Today the people of Kisar Island have no recollection of such textiles. By the mid-twentieth century they seem to have become obsolete.

Return to Top

The Waist Belt or Sash

The Oirata distinguish between a man’s belt or sash, which they call a hita, and a woman’s belt or sash, which they call an atu hilana. Atu means belly.

The Meher make no such distinction and call a belt or sash a lirrihi, whether it is for a man or a woman.

Unfortunately earlier visitors to Kisar are almost silent on the use of woven belts and sashes. In 1882 Riedel recorded that Meher warriors were led into battle by three asuaman (literally ‘father dogs’) wearing a manu wullu loore (called elsewhere a manwu-lo-or) headdress made from rooster feathers and a red or white headscarf, with a red scarf and two red cotton armbands tied under their armpits (1886, 425).

When Jacobsen visited in 1888 he mentioned the decorated belt of ‘palm ribs’ that was used to support the sarongs of Meher and Oirata women, but said nothing about woven belts or sashes. He did provide a sketch of a simple man’s warp ikat pubic belt or loincloth (männerschamgurt) decorated with a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic motif but lacking a lateral end band, but did not provide the local name.

A man’s loincloth or girdle (männerschamgurt)

(Jacobsen 1888, 132)

However his travelling companion, Heinrich Kühn, did acquire one narrow belt, which was used for tying up a sarong. It was woven in complementary warp technique using fine 2-ply machine-spun, synthetically-dyed red cotton yarn. It carries the inscription ‘Jang ampunya initali kain * salamat pakai umur pan djang * tjintahati * dibuat PD’, which would today be written: Yang ampunya ini tali kain salamat pakai umur panjang cinta hati dibuat PD. Roughly translated it means ‘I hope that this belt will be worn for a long time with love. Made by PD’. It is probable that this belt is Oirata. His companion Jacobsen recorded that most of his acquisitions from Kisar came from the Oirata community, especially the carved idols (1896, 121).

End section of a woman’s atu hilana belt collected by Kühn, width 7cm, length 144cm

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 12687

Three somewhat similar belts were acquired by Alexander W. Pflüger, a Professor of Physics, in 1900. They were all woven using synthetically-dyed machine-spun yarn, the first two using the complementary warp technique. Both damaged, the first has a simple geometric design while the second bears a similar inscription to that on the belt collected by Kühn.

Two woman’s belts collected by Alexander W. Pflüger in 1900, possibly Oirata atu hilana

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory nos 44125 and 44126

The third belt from Kisar was woven with a geometric design using the supplementary warp technique. The warp floats on the reverse side are very long.

A woman's belt decorated with supplementary warp

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory no. 44127

The German ethnographer and researcher Wilhelm Müller-Wismar, who arrived in 1914 as part of the Berlin-Indonesian Expedition to the South Moluccas, collected five narrow sashes from Kisar. They ranged in width from 11.5 to 15cm and in length from 161 to 269cm. They were not newly woven at the time of acquisition and have been assigned a date of around 1900 (Khan Majlis 1984, 291 and 292). Only three were specified as having been collected from the Oirata community but, from their appearance our opinion is that they are all Oirata weavings.

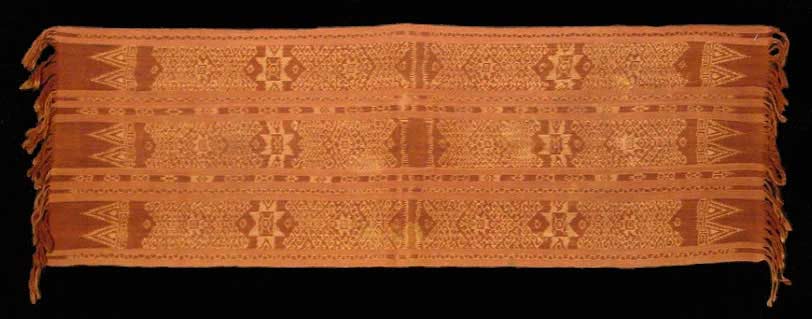

Three waistbands collected from the Oirata by Müller-Wismar in 1914. Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum - Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory nos. 36587 (13.5cm by 189cm), 36589 (13cm by 269cm) and 36590 (11.5cm by 169cm)

The belt labelled 36589 is interesting because it has two pairs of narrow warp stripes separating the side bands from the central band, one pair yellow and the other pair red. These are woven from yellow and red silk yarns. The twinned end band is also woven from yellow silk.

Two waistbands collected in 1914 from Kisar by Müller-Wismar, which appear to be Oirata. Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum - Cultures of the World, Köln, inventory numbers 36586 (15cm by 201cm) and 36588 (14cm by 161cm)

The band of twinning in band 36586 is woven from three- and four-ply pre-dyed red, mustard and white cotton yarns.

All five sashes are warp-faced, are decorated with warp ikat, have side bands and terminal sets of tumpal motifs. They are all finished with narrow lateral braided end bands and long fringes. Four are patterned with rows of hooked diamonds, but the fifth (36587) is quite different – it has a central longitudinal band of diamonds and crosses flanked on each side with anthropomorphic or bird-like motifs.

Müller-Wismar termed all five hita or hitilirrati, making him the only visitor to Kisar to have used the correct Oirata term hita for a man’s belt. Unfortunately he is also the only visitor to have used the unfathomable word hitilirrati, which has no meaning among the Meher or Oirata today. It might be a garbled combination of hita and lirrihi.

A further Oirata hita was acquired by the National Gallery of Australia in 1985, who have labelled it as a nineteenth century hita or hitilirrati loincloth.

An Oirata hita man’s belt, width 13cm, length 250cm.

National Gallery of Australia. inventory number 1985.384

Robyn Maxwell suggested that such items were originally loincloths that had ceased to be worn as intended and were then used as girdles and shawls (1990, 39). We are not aware of any evidence to support this assertion. These sashes appear to be too narrow to be used as loincloths.

Müller-Wismar's label ‘hita or hitilirrati’ has been misapplied parrot fashion to several Kisar bands and loincloths. It has even been applied to the warpitare ceremonial loincloth in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia (Maxwell 1990, 39).

Return to Top

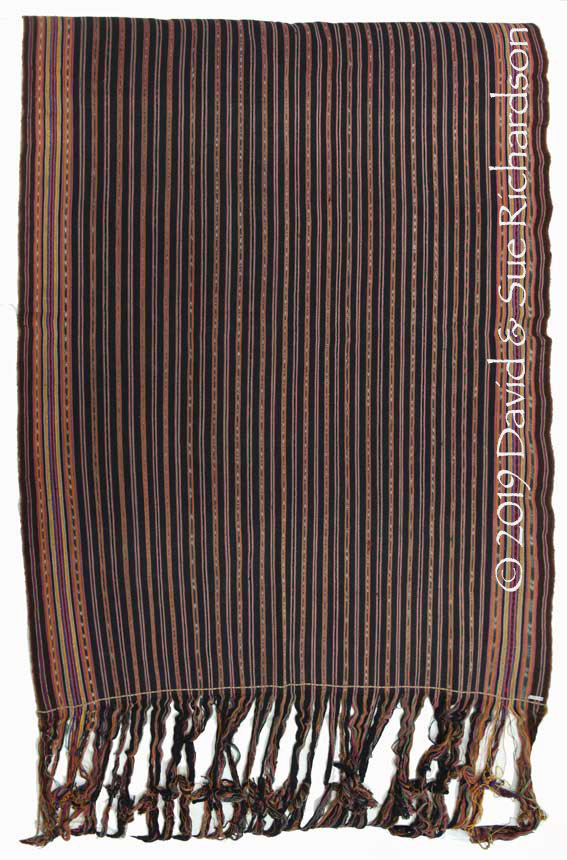

The Male Blanket

The majority of Kisar men’s blankets are formed from two separate panels of cloth, each woven separately on a continuous warp. They are mainly decorated with an assortment of narrow bands and stripes, some plain and others decorated with warp ikat. The two panels are sewn together side to side and stabilised at each end with a single band of decorative weft twinning. The end warps are left as a fringe that can be plain or gathered and twisted. Such blankets can be used as a waist wrapper or shoulder cloth.

A few blankets are woven as one cloth with no centre seam. They cannot have been used as loincloths because they are too wide and of insufficient length.

It seems impossible to locate a single old Kisar blanket woven from naturally dyed, hand-spun cotton. Given that men traditionally wore a loincloth and not a hip wrapper, one wonders if these blankets were a later development, inspired by the mestizo senikirs – see below. If so, this would explain why they are more common among the Meher, who lived close to the mestizos, compared to the Oirata, who did not.

Return to Top

The Oirata Namlau

The Oirata refer to a man’s blanket as a namlau, literally man’s cloth, a nami being a male or man and a lau being a cloth. These are no longer made for, or worn by, the men of Oirata today. Even old ones appear to be quite rare.

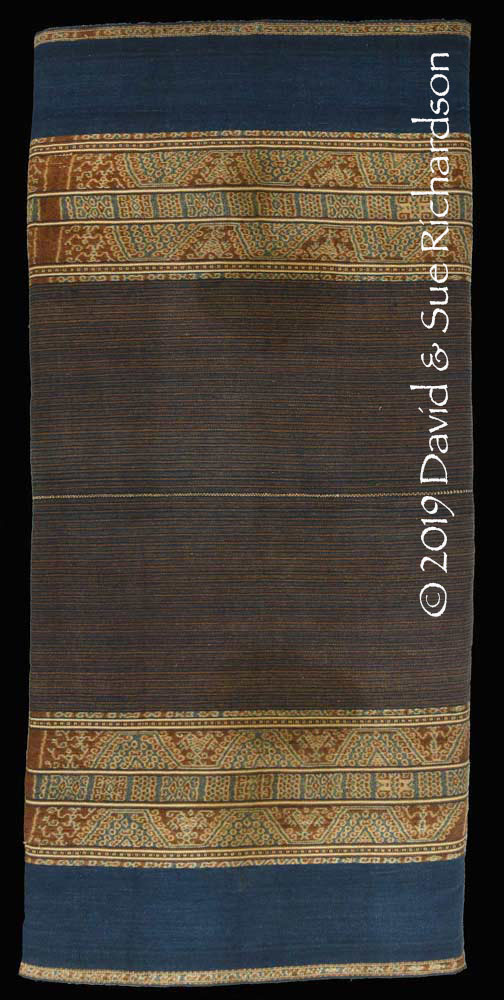

We cannot be certain but the quality of the ikat suggests that a blanket collected by the Koloniaal Museum in 1910 is an Oirata namlau. If correct this is the earliest example we can find. It is most unusual, composed of a single central panel covered with narrow plain and ikatted warp stripes and a pair of wider ikat bands decorated with floral motifs. We see the latter in some later Oirata weavings and assume they are European inspired.

Believed to be an unusual namlau with a floral motif, collected in 1910.

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-6207-207. Creative Commons Licence

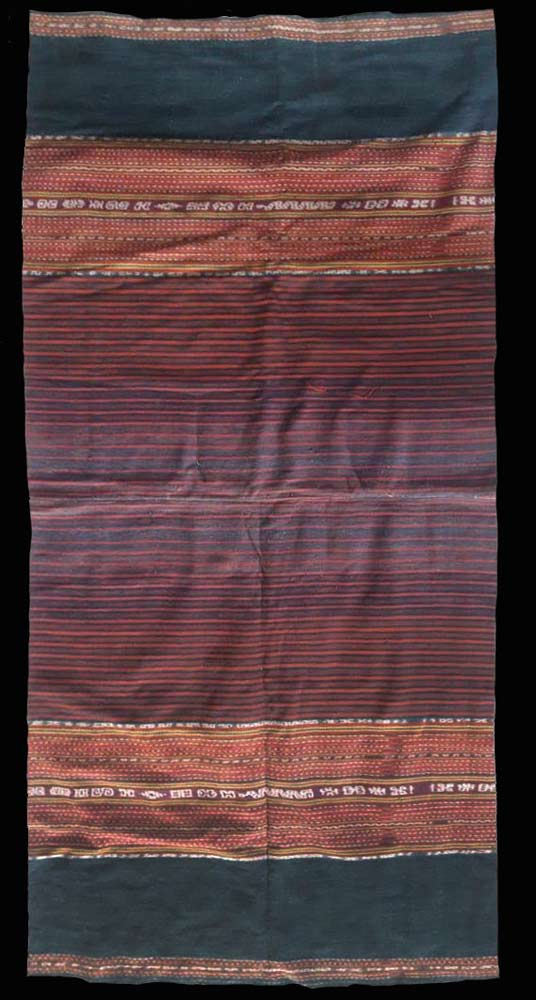

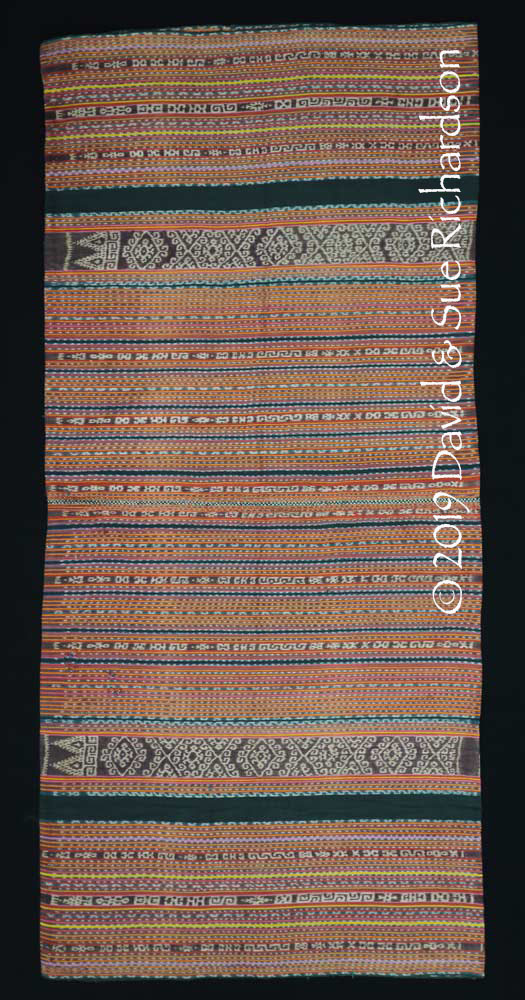

Two slightly later weavings are definitely Oirata. They are two-panel namlau ma’maro decorated with anthropomorphic ma’maro motifs, both woven around 1925 by Levina Hooru, an aristocratic noblewoman living in Oirata Barat. In the century from 1880 until 1980, the influential Hooru family provided four of the seven kepala desa of Oirata Barat.

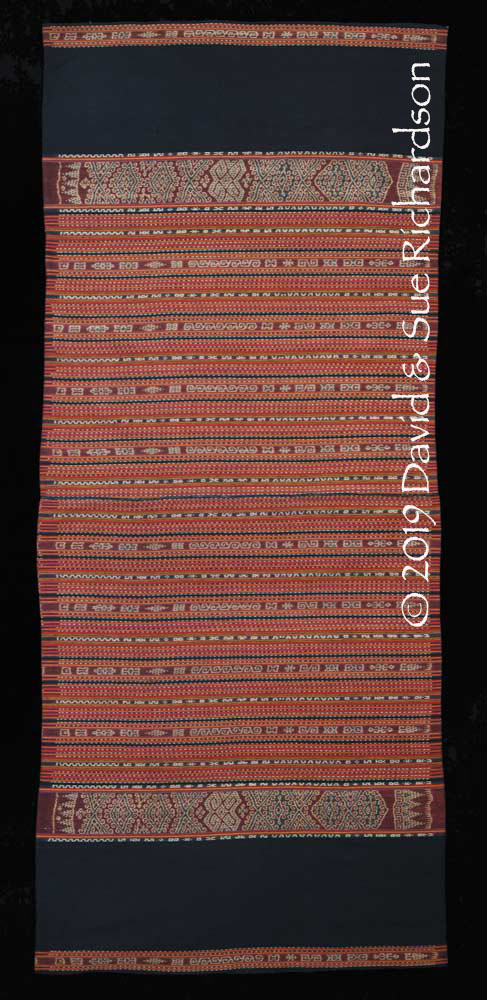

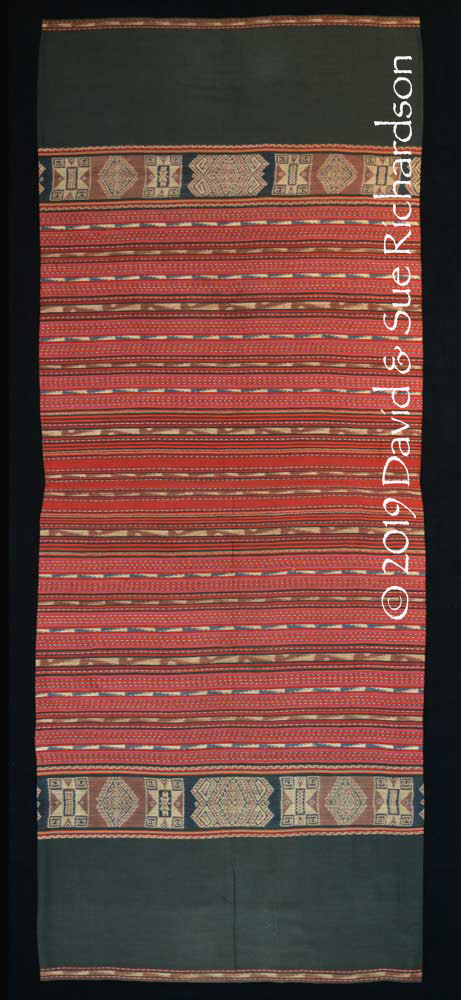

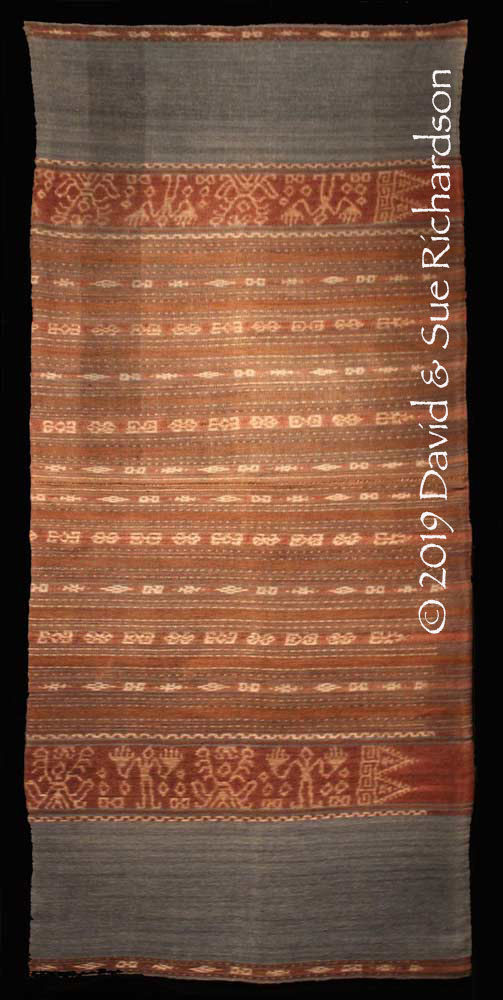

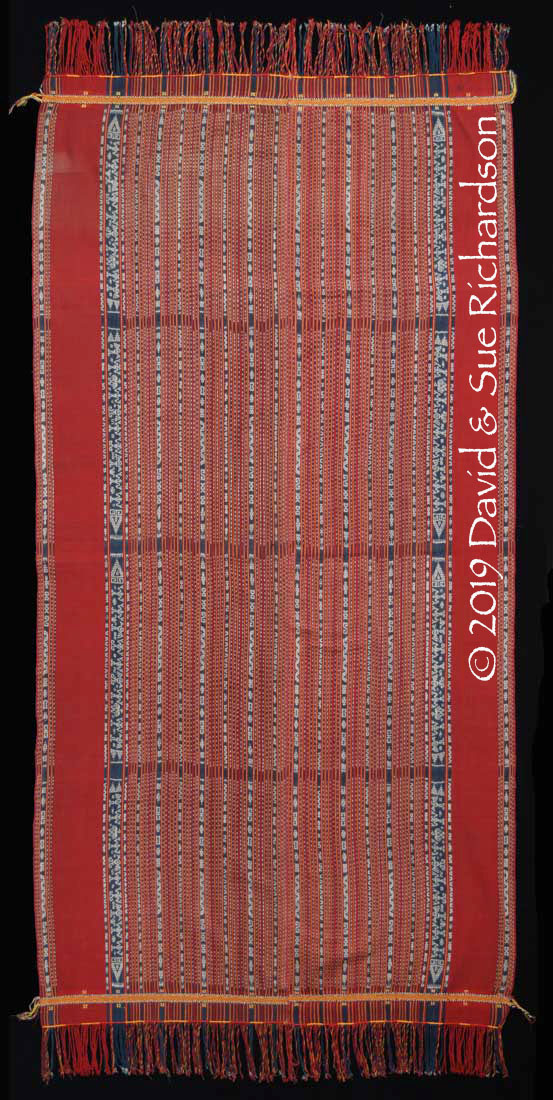

A namlau ma’maro woven by Levina Hooru in approximately 1925. She was born in about 1900 and lived in rumah Kelihi in Oirata Barat. Richardson Collection

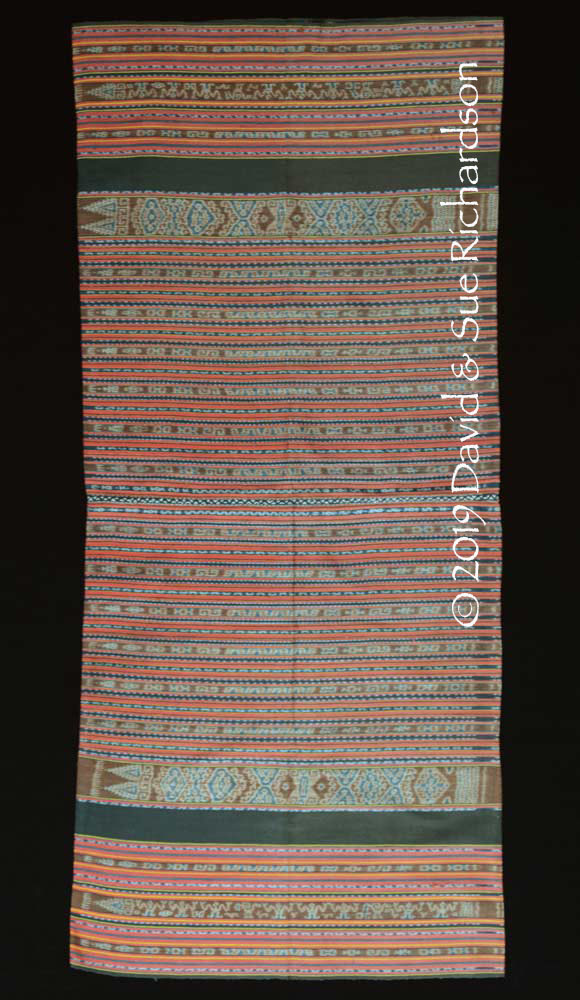

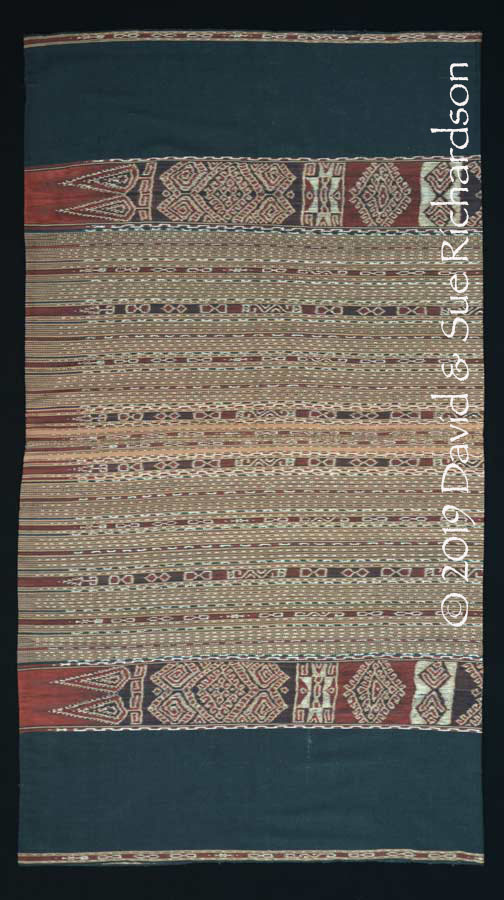

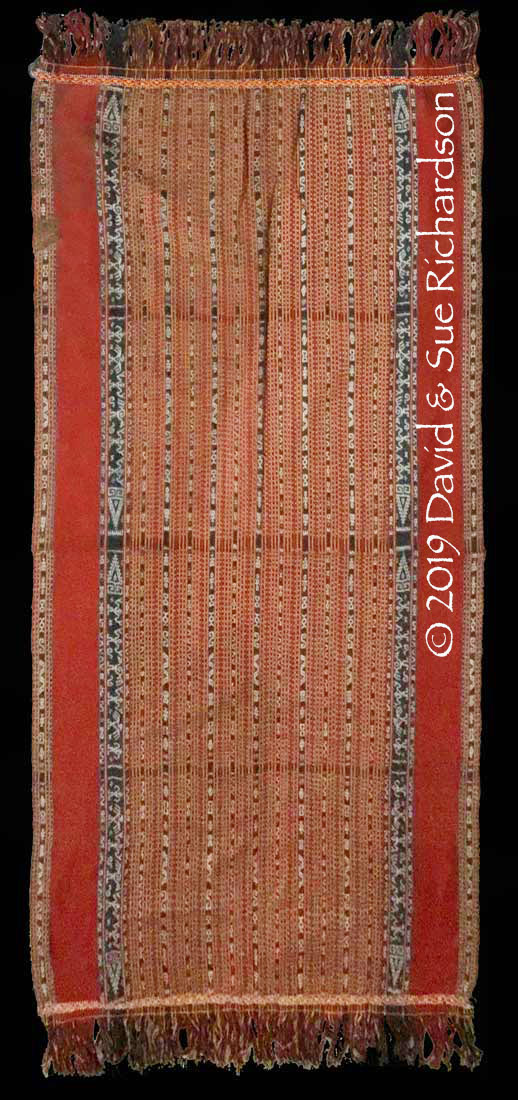

A second namlau ma’maro also woven by Levina Hooru in approximately 1925

Private Collection Ambon

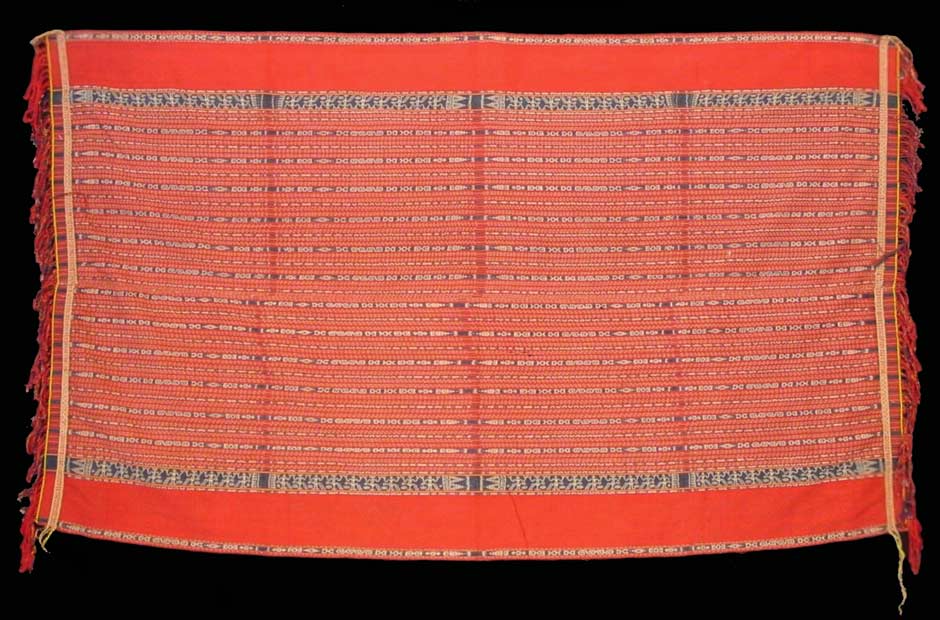

The only other example of a two-panel namlau ma’maro that we can find was acquired by the Koloniaal Museum at some time prior to 1940.

A namlau ma’maro acquired before 1940

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-1772-1217. Creative Commons Licence

Josselin de Jong reported that the Oirata term for a cover is a kawar, which also means a roof. A shroud is a wetur or kawas or more usually a wetur kawas (Josselin de Jong, 1937, 246 and 288).

In Fataluku-speaking Lautem in Timor-Leste, a man’s blanket has the same general name as a woman’s sarong – a lau (Barrkman, Finch and Afonso-Henriques 2009, 37). More precisely a man’s cloth is called a nami lau or alternately a lau sekuru covering cloth (Soares 2015, 13).

Return to Top

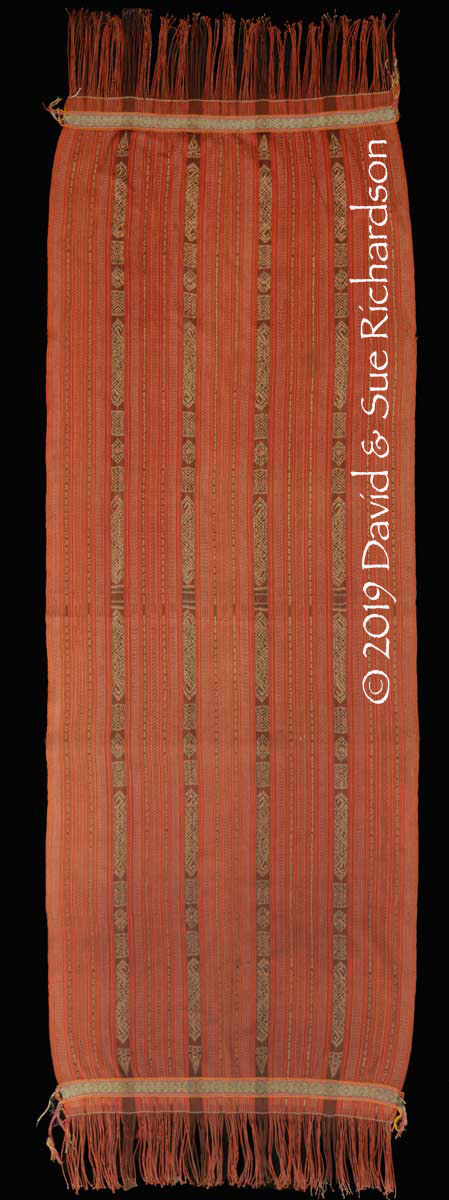

The Meher Hoire

The Meher refer to a man’s blanket as a hoire or hoir. More specifically the hoire wakawaka is a two-panel blanket with bands of either indigo or morinda ikat. Wakawaka means to join two panels to make one piece.

Riedel was the only historical visitor to Kisar to use the term hoire for a Meher man’s shawl (omslagdoek) or wrapping cloth (Riedel 1886, 419, 423-424). Unfortunately he left us no description of its appearance.

He did however report that the hoire had an important ritual use. If a person became sick they consulted a priest-like medicine man, known as the leher marna, who treated them with natural remedies. If they were healed they were obliged to kill a sheep and cook a piece of the ear, lips and liver with some rice and sirih-pinang. This was offered to the leher marna on a plate placed upon a flat circular rice basket covered with a hoire. The leher marna then threw the contents of the plate under the tree from which he obtained the medication and retained the hoire as payment for his services (Riedel 1886, 419).

The Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam has a number of Meher hoire, collected by the Koloniaal Museum from the time of its opening in Haarlem 1871 until its closure in Amsterdam in 1944. We suspect that the earliest example is Meher rather than Oirata although in the absence of provenance we cannot be certain.

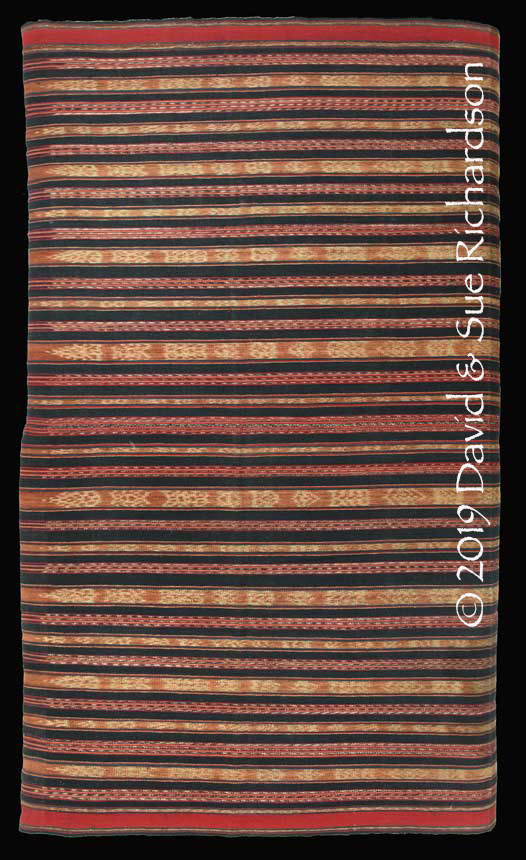

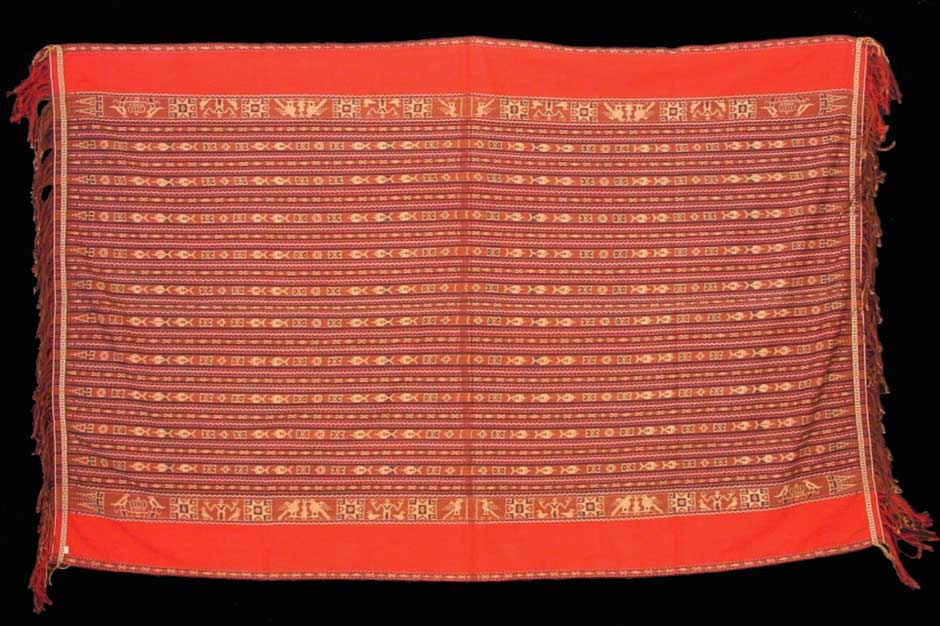

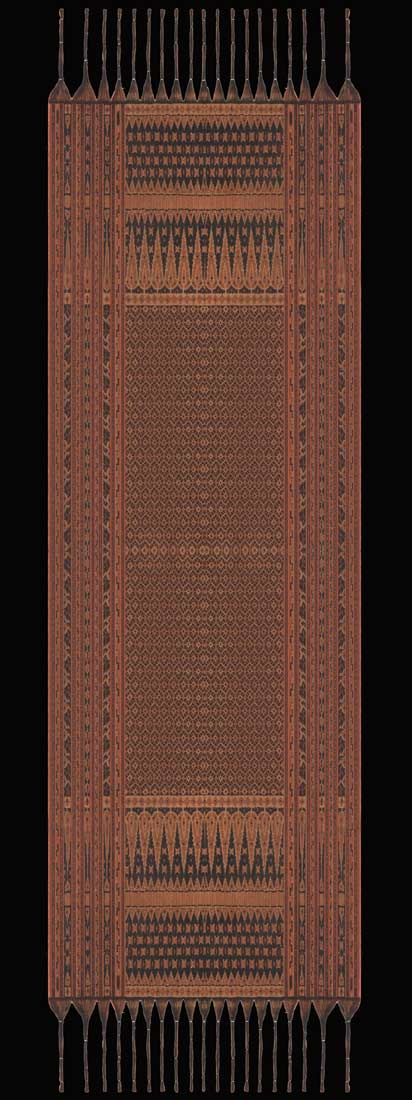

Probably a Meher hoire wakawaka collected before 1886

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-H-1936. Creative Commons Licence

On four later examples, the motifs are all definitely Meher. Note that the bands of ikat can be dyed with either indigo or morinda at the discretion of the weaver.

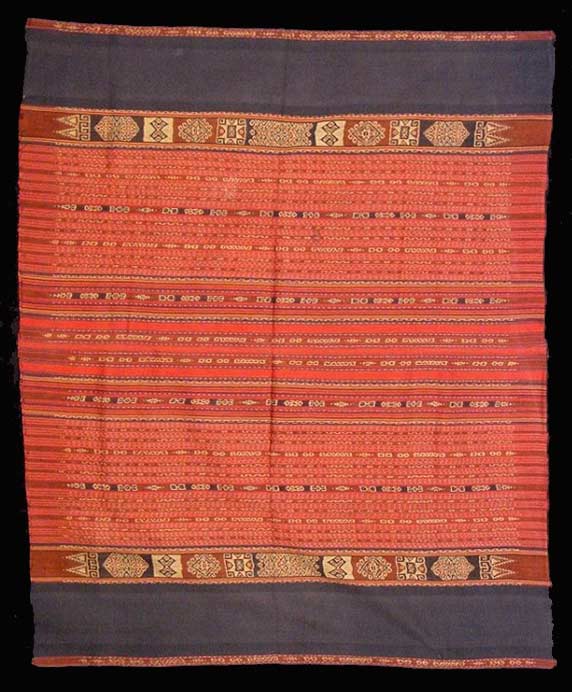

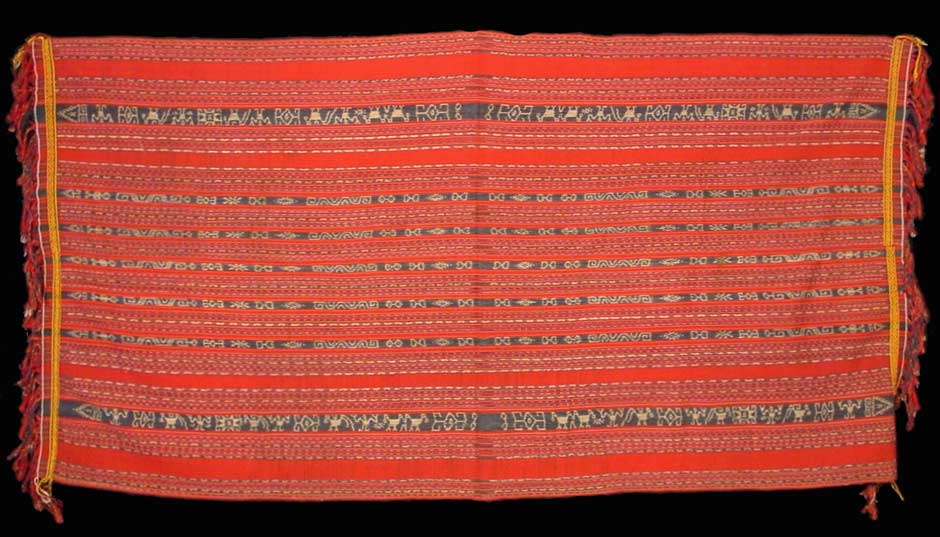

A Meher hoire wakawaka with fish motifs acquired before 1919

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-77-32. Creative Commons Licence

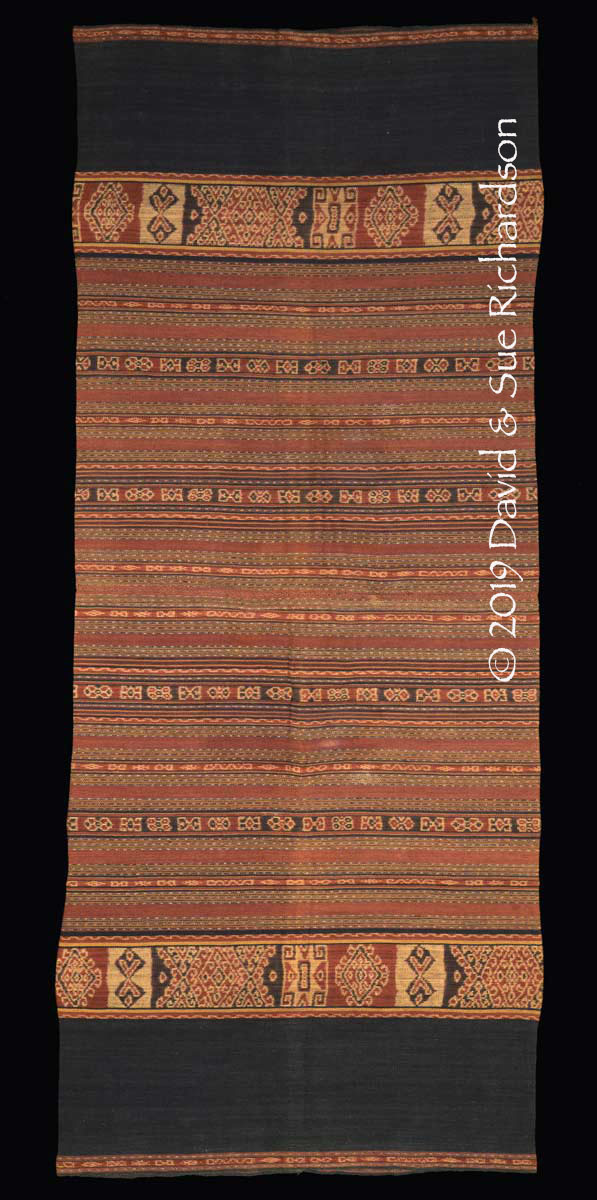

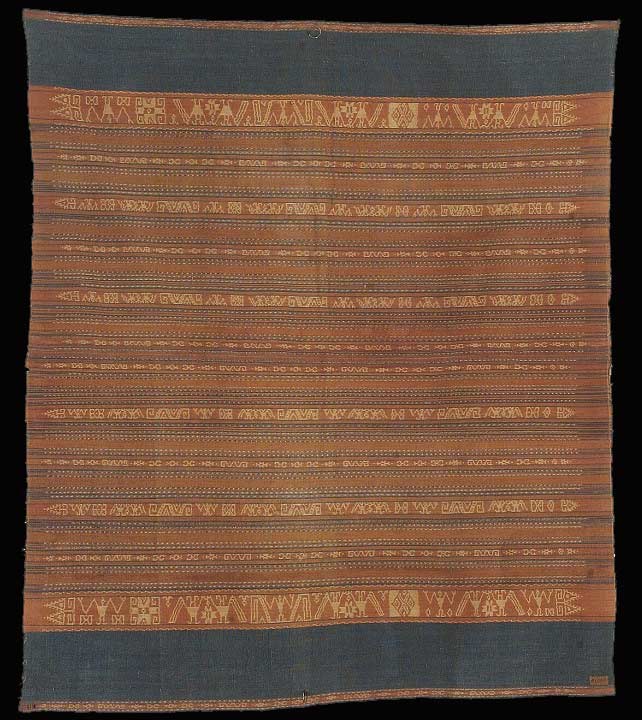

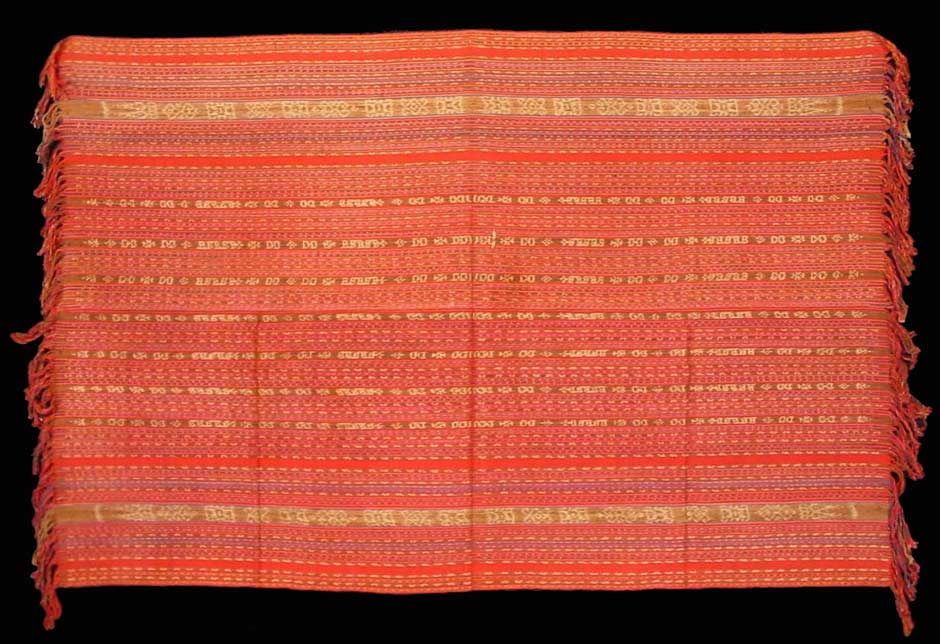

A Meher hoire wakawaka acquired before 1929

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-556-100. Creative Commons Licence

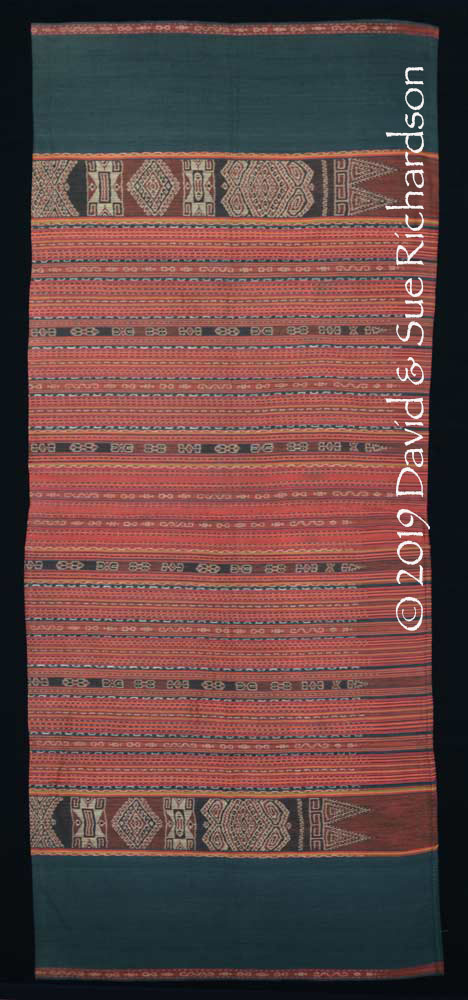

A Meher hoire wakawaka collected before 1929

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-556-108. Creative Commons Licence

A Meher hoire wakawaka with the layout of a homonon, collected prior to 1929

Collection of the Tropenmuseum, TM-556-103. Creative Commons Licence

A tiny number of elderly Meher weavers are still producing these blankets today in the hamlet of Yawuru.

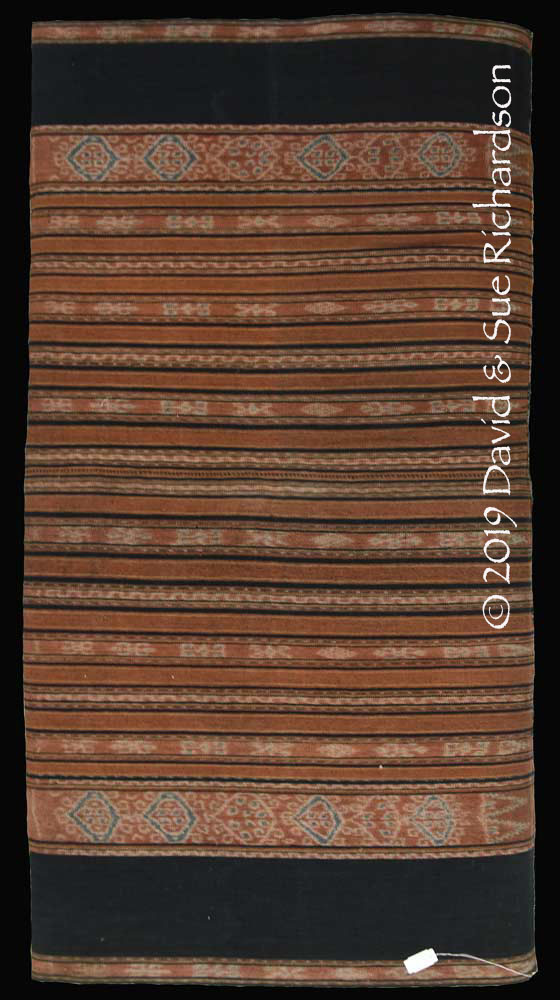

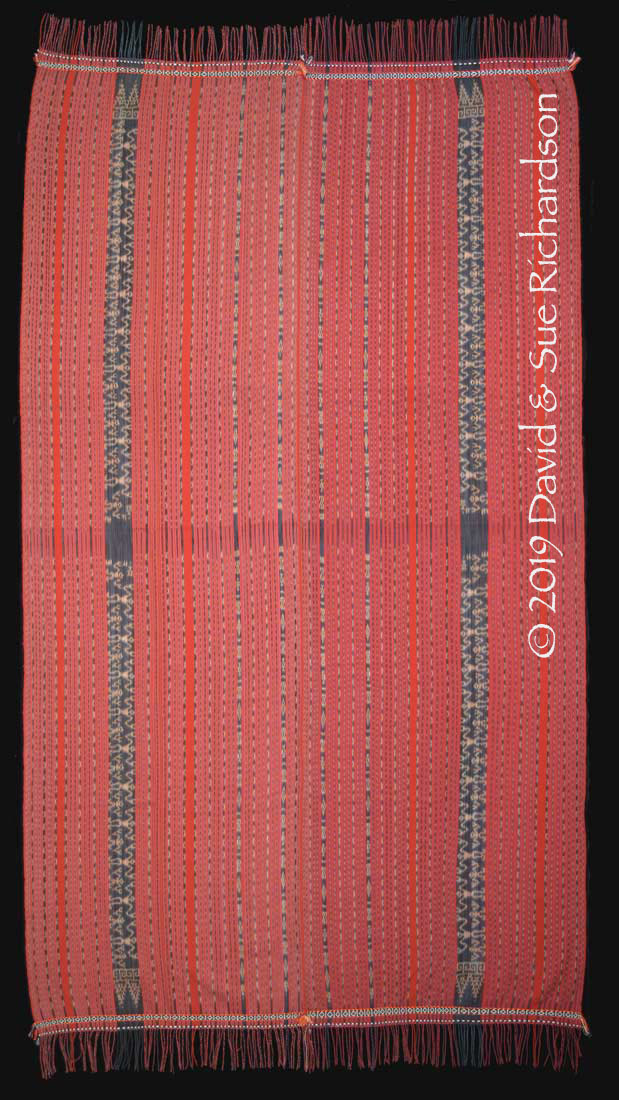

A hoire wakawaka woven in 2017 by Rahel Letelay, aged 81, from dusun Yawuru

Richardson Collection