Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Part 1

Geography

Myths of Origin

Local Oral History

Pre-History of the Ende Region

Pre-Colonial History

The Portuguese on Solor

The Ende Island Mission

The Dutch on Solor

The Makassarese move to Ende

Piracy and Unrest

Part 2

The Siboga Expedition 1899

Dutch Direct Rule 1907-1942

The Japanese Occupation 1942-1945

Post-War Developments 1945-1949

Ende following Independence

Bibliography

Geography

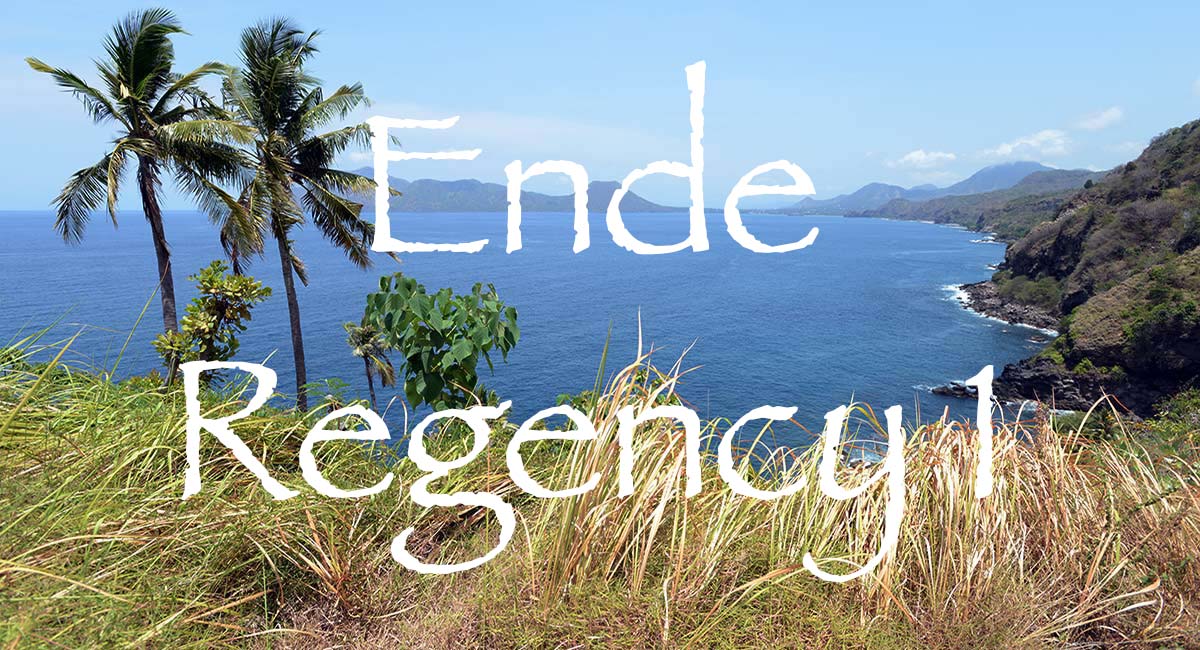

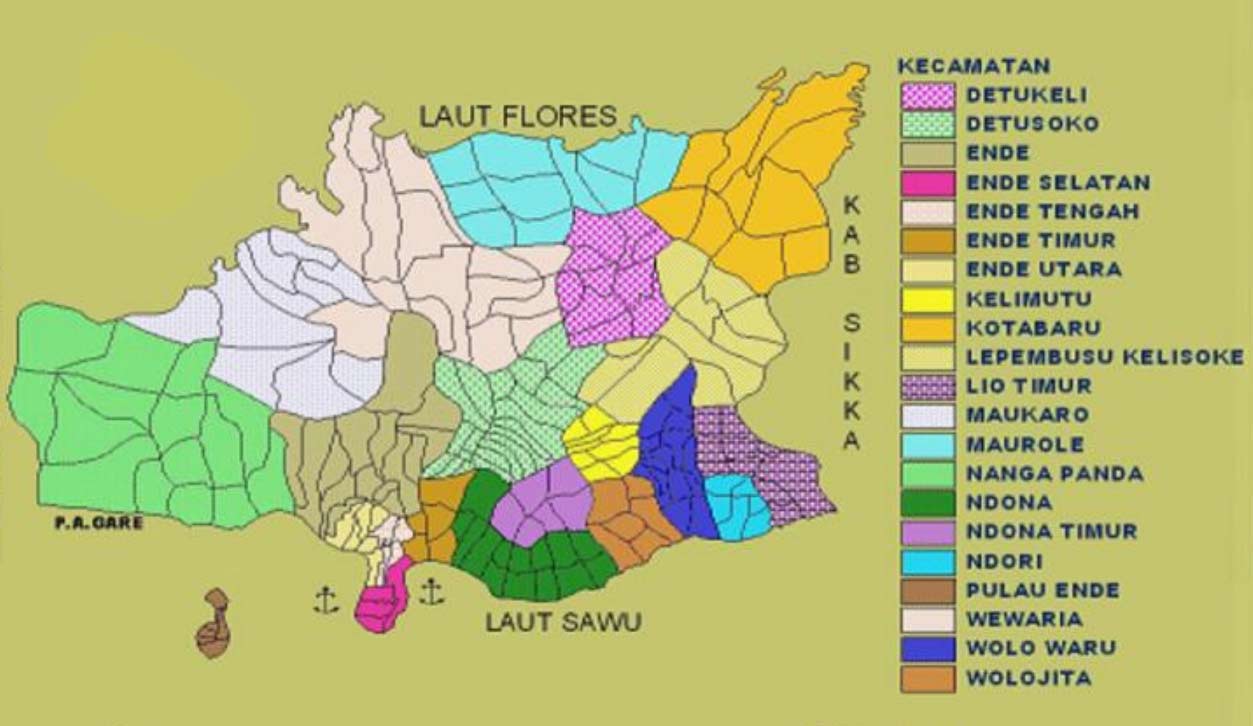

Ende Regency (Kabupaten Ende) occupies the central portion of Flores Island, sandwiched between Nagekeo Regency in the west and Sikka Regency in the east. It was formed in 1958, following Sukarno’s introduction of a new system of regional government.

Ende has a rugged, mountainous, forest-covered landscape carved by numerous long winding rivers. The largest river is Lowo Rea, which flows northwards into the Flores Sea. Lowo Wolowona flows towards the southeast, entering the Savu Sea just east of Ende City, while Lowo Wadjo flows to the southeast, entering the Savu Sea close to the border with Sikka Regency.

Above: The heavily forested landscape of Ende Regency.

Below: Overlooking the Mbuli River Valley close to the southern coast.

Some 90% of the land area of Ende Regency has slopes with an inclination greater than 12%, resulting in many landslides, rock falls, and mud flows during the rainy season.

Clearing a major landslide along the Trans-Flores Highway between Ende and Wologai

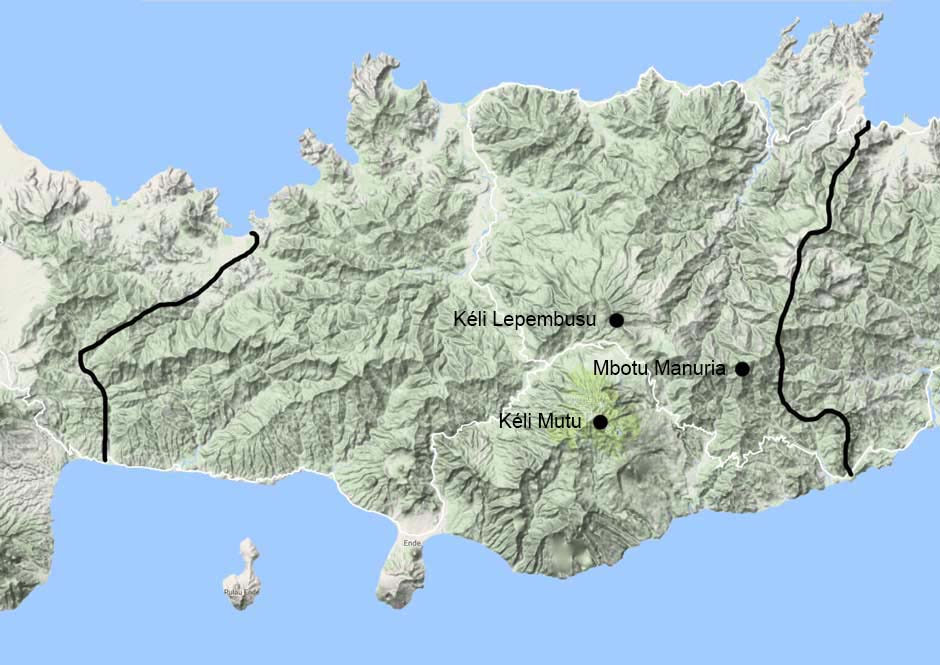

The rugged topography of Ende Regency (Source: Google Maps)

The highest mountains are Kéli Lepembusu (1792m) and Mbotu Manuria (1670m), both in the central highlands. There are also two active volcanoes, the largest being Kéli Mutu (1613m), literally 'Boiling Mountain', in Kéli Mutu National Park, its multi-coloured crater lakes being the largest tourist attraction on Flores. Smaller Gunung Iya (659m) lies at the tip of the promontory that extends south from Ende City. The latter is situated at the neck of the promontory, just north of flat-topped Gunung Meja. The old town of Ende (formerly Endeh) lies on the west coast, while the new town sprawls eastwards towards the modern ferry port of Ippi. Kota Ende is not only the Regency capital but also the largest town and port on Flores Island.

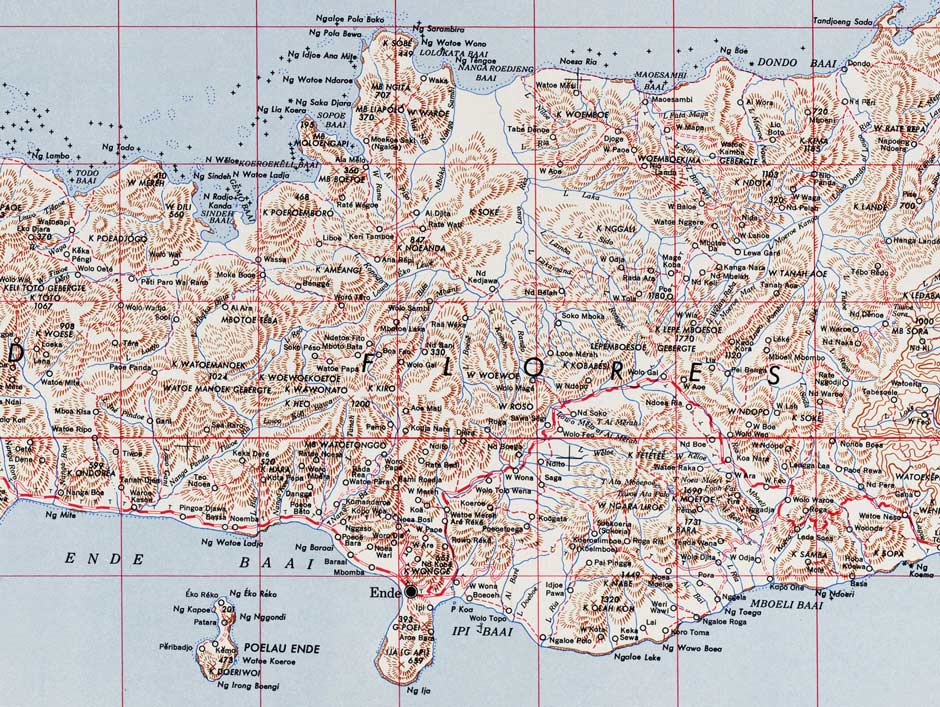

Map of Ende Region

(US Army Map Service, Washington D. C., 1943)

From the west, the main Trans-Flores Highway follows the southern coast as far as Ende City and then skirts inland to pass between the mountain massifs of Lepembusu and Kelimutu, before returning to the southern coast at Tola. At Wologai a minor road heads north to connect with the north coast road.

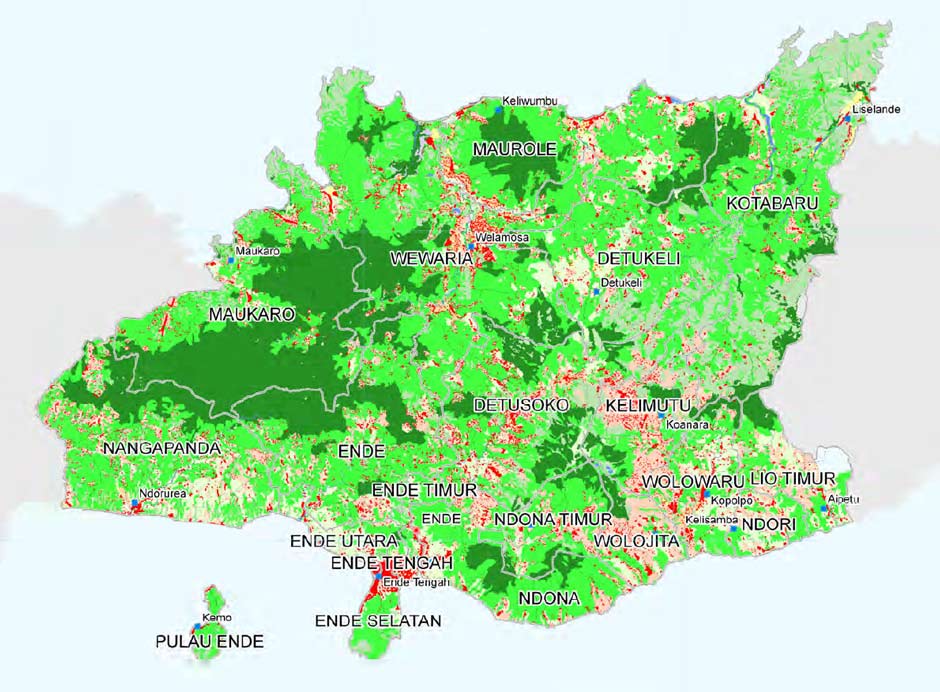

Ende Regency Land Use. Key: red = settlements, dark green = forest, light green = savannah (Source: Badan Koordinasi Survei dan Pemetaan Nasional Georisk-Project)

The population of Ende Regency was 270,763 in 2020 (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Ende). About 80% of the population live in the southern part of the Regency, leaving only 20% spread across the five northern districts (Maukaro, Wewaria, Maurole, Detukeli and Kotabaru). Roughly 93% are classified as Roman Catholic and 7% as Muslim (De Jong 2013, 280). With a population over 60,000, Ende City is the largest town on Flores. It has two harbours, Ende and Ippi, along with a domestic airport. The small offshore island of Ende supports a population of 8,200 including a fishing community of 1,700.

Politically, Kabupaten Ende is divided into 21 districts or Kecamatan:

The Kecamatan or Districts of Kabupaten Ende

From the point of view of textiles, those of greatest interest are those that lie adjacent to the southern coast, listed from west to east:

| Kecamatan Nanga Panda |

| Kecamatan Ende |

| Kecamatan Ende Utara |

| Kecamatan Ende Tengah |

| Kecamatan Ende Selatan |

| Kecamatan Ende Timor |

| Kecamatan Ndona Timor |

| Kecamatan Wolojita |

| Kecamatan Wolo Waru |

The southern kecamatan of Kabupaten Ende

Return to Top

Myths of Origin

The mountain Lio share a myth of origin that has been documented by two researchers. The first was reported in 1989 by Masao Yamaguchi, who in 1974 conducted fieldwork in the Lio region of Wologai, which lays in the southern foothills of Kéli Lepembusu some 16km north of Nggela and later in 1996 by Signe Howell, who conducted intermittent fieldwork among the northern Lio in 1984, 1986, 1989, 1993 and 2000. The two accounts are similar although Howell notes that there are different versions of the same myth, some conflicting and some incomplete.

The Lio believe the first ancestor was Ana Kalo, who arrived at the island of Flores in a small boat. His origin is not given. The term ana kalo refers to an orphan with no parents. Ana Kalo landed on the summit of Kéli Lepembusu, the tallest mountain in Ende Regency. At that time the summit was completely surrounded by water and the sky was close to the earth. There was so little space he had to crouch and eat from the palm of his hand. He planted a garden of sweet potatoes (ndora) but some of his crop was stolen at night. He watched over his garden to catch the thief and discovered that it was a red pig. He slashed it with his parang but it escaped into a tall banyan (lélé) tree – the cosmic tree that connected the heavens to the earth. The next day he found blood on the ground and followed it to the tree, which bore golden fruits. He looked up and saw the pig in the tree and in his anger severed the trunk of the tree with his parang. However the pig managed to climb a branch into the sky where it became the star known as wawi toro (red pig), which still shines today.

The peak of Kéle Lepembusu in the central massif of Ende Regency

By foolishly cutting the trunk of the tree, Ana Kalo terminated the supply of golden fruits. The heavens ascended and the primeval waters retreated to their current level. However the branch that connected the heaven and earth remained in the form of a gold chain (londa).

When Ana Kalo returned to the location of the tree he met a young girl, who he brought back to his garden and married. They had many children together but all of them died in infancy because Ana Kalo did not know how to cut their umbilical cord. He finally used the mast of a boat to make a knife that would cut the umbilical cord. Thanks to the knife they finally produced a son and a daughter whose descendants are the Lio people of today.

According to Yamaguchi’s interpretation, the myth describes the birth of humanity. The boat of Ana Kalo represents the mother's womb carrying the foetus surrounded by primeval waters, while the cutting of the cosmic tree represents the severance of the umbilical cord. Today the primordial boat in which Ana Kalo arrived at the top of Kéli Lepembusu is represented by the Lio clan house, the sao ria, and the cosmic tree by the pusu até, the rope that is suspended from the ceiling in the Lio clan house.

Eriko Aoki (2003, 156) reported that for the Lio, Ana Kalo was the very first human being and Kéli Lepembusu was the navel or the centre of the world – prior to his arrival the world was devoid of humanity. As people came down from the mountain they progressively dispersed and occupied the whole of the Indonesian Archipelago and beyond.

One version of the myth or origin claims that at one time there were seven villages on Kéli Lepembusu when the rest of the world was covered in water. Each village was home to a different ethnic group – the Goa, Tidhu, Buto, Melaka, Java and so on. When the Buto people felled the cosmic tree and the water withdrew, the people began to disperse. When they reached Watuwatawanda the seven ethnic groups made a treaty of alliance and slaughtered a small buffalo and pig. By the time the Europeans (Dutch) finally returned to their original homeland, they had long forgotten the treaty that they had made in ancient times and attacked the Lio.

The coastal Endenese have a different myth of origin concerning the lineage of the rulers of Ende town - the Rajas of Ende. This was documented by the former Dutch civil commander Gezaghebber B. van Suchtelen in 1910 (Lewis 2014, 179-180). After two brothers living in the rajadom of Majapahit had a trivial dispute, one of them named Djari Djawa decided to immigrate to another land. He travelled on the back of a whale to the south coastal village of Naga Sa, located at the mouth of a river west of Ende. There he married a native woman and later married two more women, one from neighbouring Sumba Island and another from the district of Nggela. One of his grandsons married a woman from the mountains and was promoted by the surrounding villages, eventually becoming the first Raja of Ende.

The concept of an immigrant from Majapahit Java marrying a native woman and founding the ruling lineage of the coastal Endenese is yet another case of the ‘stranger-king’ phenomena, elucidated by Douglas Lewis, where an indigenous community supposedly adopts a foreigner as their leader.

Return to Top

Local Oral History

The oral histories of the Lio-Ende people have received only limited attention by modern anthropologists.

Many Lio communities, such as the coastal Lio, have local oral histories that describe how their ancestors founded their villages. In May 2018, three of the senior mosa laki of Nggela – Pak Gabriel, Pak Thomas and Pak Leon Bule – recounted to us the story of how their own village was established.

Their ancestors previously lived in the mountains but several centuries ago, maybe around four, they began to move down to lower elevations. This migration was not the result of war or conflict but was driven by the desire to find better land. It was not a mass migration but involved small groups dissipating over an extended period of time and spreading out to occupy the whole of the southern coastal Lio region.

The ancestors of the village of Nggela were A Nggoro and his wife Ni Mbuja. They had four children, three of whom were sons. The eldest was A Nogo, the next eldest was A Tori and the youngest was A Niri. Their youngest child was a girl called Ni Nggela.

The family decided to break away from their community and head southwards. They initially settled at Lelebewa just to the north of Nggela, and used the forest location of Nggela to distil tuak. Later they moved to the present day location of Nggela, just 1km from the coast, naming their new kampong after their daughter.

The four siblings constructed four houses:

- Nogo built Sa’o Rore Api

- Tori built Sa’o Labo

- Nira built Sa’o Wewwa Mesa and

- Nggela built Sa’o Ria.

Sometime later the families of A Rangga Se and A Tua arrived from north Wewaria. A Rangga Se settled at the hamlet of Rangga Se, close to Jopu, but A Tua built Sa’o Tua in Nggela. They were followed by the families of Meko and Ndoka who built Sa’o Meko (next to Sa'o Rore Api) and Sa’o Ndoka.

Return to Top

Pre-History of the Ende Region

Archaeological research in eastern Indonesia is at a very early stage, so our understanding of its ancient history is extremley patchy. In the geological past, Flores Island offered a narrow corridor for the dispersal of the flora and fauna of Asia into Oceania, as well as the first human beings.

Evidence shows that Homo erectus was already present at Sangrian close to Solo in Central Java some 1.8 million years ago, which at that time was on the southern coast of the mainland of Sundaland (Husson, Salles, Lebatard, A. E. et al, 2022). Human migration further east was constrained by the deep Lombok Strait, separating Sundaland from the eastern islands of the Indonesian Archipelago.

Research conducted at the many fossil sites in the Ola Bula siltstones of the Soa Basin of Nage Keo Regency, just 50km west of Ende city, has established that Homo erectus was already present some 840,000 years ago and was probably making basalt flake tools (Morwood 2011). Either these early humans possessed the ability to make watercraft capable of transporting a small community across a dangerous marine obstacle like the Lombok Strait or else they arrived by chance – for example as survivors on a raft of vegetation following a tsunami (Dennell et al 2013). They shared the region with the large Stegodon, the Komodo dragon, the crocodile and the giant rat.

The first modern humans were already present at the Lida Ajer cave in the Padang Highlands of Sumatra 73,000 years ago and were occupying the Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem land in the Northern Territory of Australia around 65,000 years ago (Westaway et al 2017; Clarkson et al 2017). It therefore seems likely that they may have reached Flores Island at some time in between, crossing the 20km wide strait that then separated Sumbawa from a merged Flores and Komodo Island (Morwood et al 1998; Morwood and Jungers 2009).

Excavations at the limestone cave of Liang Bua

The earliest evidence so far discovered regarding the presence of Homo sapiens on Flores is limited to a pair of 46,000-year-old human molar teeth found at the Liang Bua cave site, just north of Ruteng in Manggarai Regency. If modern humans did reach Flores some 70,000 years ago, they may have shared the island for many millennia alongside Homo floresiensis, whose remains have been recovered from the same cave complex. This small species of human appears to have become extinct around 50,000 years ago.

Given the excessive archaeological focus on Homo floresiensis, discoveries of modern human remains have so far gone unpublished. For example, both Mesolithic and Neolithic remains have been found at Liang Bua, some up to 11,000-years-old (Lindelof 2013, 18).

The Dutch SVD priest Father Theodor Verhoeven conducted some of the earliest archaeology on Flores. During the 1950s he excavated various sites at the western end of the island, recovering the remains of twelve modern humans. The sites included the Liang Momer rock shelter, Liang Panas, Gua Alo and Liang X in West Manggarai, the Liang Togé overhang in East Manggarai, and Aimere in Ngada Regency. The skeletons, two with complete craniums, were sent to Utrecht to be examined by Professor Huizinga, who was of the opinion that they were ‘negritos’, in other words Melanesians (Verhoeven 1958). Later in 1965 Verhoeven began his excavations at Liang Bua where he recovered six Neolithic burials with grave goods. These Melanesian and Malay finds were roughly dated to around 2000 to 1000 BCE.

It is still impossible to say when the indigenous Melanesians (Papuans) of Flores Island were first joined by Austronesian-speaking immigrants. Not only is there a general scarcity of archaeological sites, but many are poorly preserved or have been damaged by changes to the physical environment.

It is generally accepted that the beginning of the Neolithic in Island Southeast Asia began around 2000 BCE but in some regions was delayed, in some cases as late as 300 BCE (Spriggs 2011). The arrival of the domesticated European pig, Sus scrofa, on Flores around 2000 BCE suggests that some Neolithic farmers may have arrived at the same time (Larson et al. 2005; Larson et al. 2007; Larson et al. 2009). An isotopic study of fossil pig bones and teeth recovered from Flores points to changes in their food supply at some point between 3160 and 750 BCE, suggesting an intensification of agricultural activity (Munizzi, Jordon, 2013).

One of the most important Flores sites is that of Pain Haka on the north coast of East Flores, a cemetery containing at least 55 primary and secondary burials, 13 with remains interned in ceramic jars (Galipaud et al 2016). Other pots and flasks were buried alongside as grave goods, one decorated with a human face. The site is classified as Neolithic and on the basis of C14 seems to have been in use from 1050 to 150 BCE. The majority of individuals for whom the burial context was identified had been wrapped in some type of loose organic material (Harris et al 2015, 303).

Return to Top

Pre-Colonial History

The earliest historical reference to the island of Flores appears in the Nāgara-Kěrtāgama chronicle, written in Bali by the court poet Prapañca in 1365. In 1292 the Hindu Majapahit state emerged out of the former kingdom of Singhasari in the Brantas Valley of Eastern Java. As it gained economic and military strength on the back of rice culture and maritime trade, it began to extend its influence throughout the Indonesian Archipelago. Following a long military campaign, the Majapahit grand-vizir, Gajah Mada, finally subjugated Bali in 1343, turning it into a vassal state. A Javanese noble, Kresna Kapakisan, was appointed to rule Bali and from then on the Balinese courts were based on the Majapahit model.

Some years later Gajah Mada led a powerful naval expedition eastwards, conquering much of Nusantara. The Nāgara-Kěrtāgama chronicle lists those countries east of Java that were subordinated under Nusantara (Pigeaud 1960, III, 17; Pigeaud 1962, IV, 34). First and foremost was Melayu, followed by Tanjungnegara, Hujung Medini, Jawa, Makkasar and Dwipantara. The nations of Makassar consisted of Buton, Banggawi, Kunir, Galiyao, Salayar, Sumba, Solot, Muar, Wandan, Ambon, Maluku, Waning, Serantau, Timor and other surrounding islands.

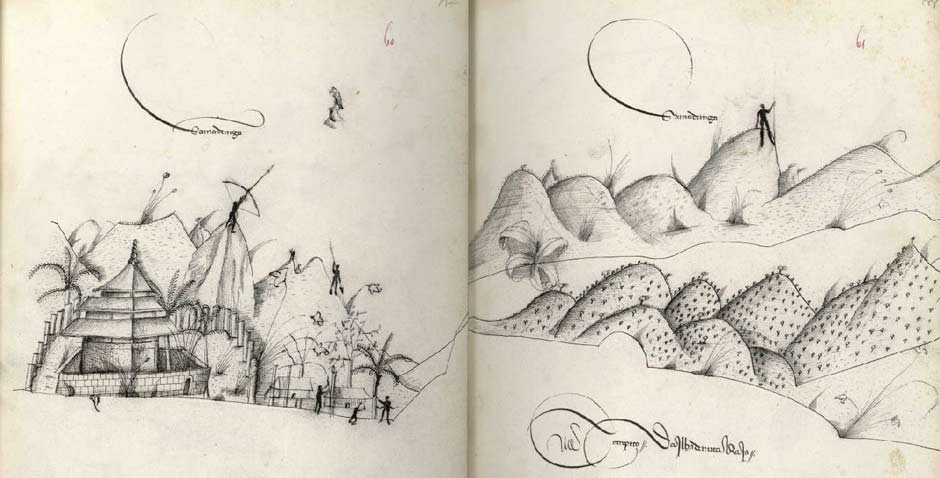

Solot probably referred to the eastern part or perhaps the whole of Flores Island, along with Adonara and Solor, a deduction first made by the Flores scholar Petu Sareng Orin Bao. We know nothing about the relationship between Majapahit Java and Flores except that unlike Bali, Flores did not become an integral part of the Majapahit State. It is possible its leaders might have been obliged to formally declare allegiance at court and possibly supply military manpower to Java. As the Portuguese discovered, Java still maintained a claim over Solor as late as the 1560s. Interestingly a Hindu temple appears on a panoramic drawing of the north coast of Flores Island (named Ilha de Samademga) made from the sea by Francisco Rodrigues in 1513 (Rodrigues 1944, 526; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 73).

The middle eastern part of Flores Island sketched by Francisco Rodrigues

Return to Top

The Portuguese on Solor

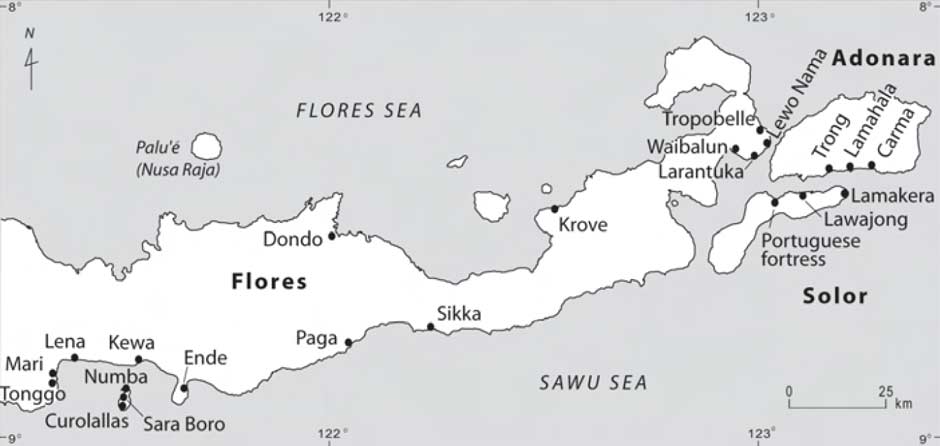

After taking Muslim Goa in 1510, Alfonso de Albuquerque commanded a Portuguese fleet of 17 ships and conquered Muslim Malacca the following year, establishing the first European colony in Southeast Asia. He immediately dispatched three small ships to explore the Eastern Spice Islands. They sailed along the north coasts of Sumatra, Java, Sumbawa, Flores and Solor before crossing the Banda Sea to Banda, before continuing to Ambon and Ternate. From 1513 a trading fleet from Portugal began visiting the Spice Islands annually, setting out from Malacca in September and January and returning in June and October (Jacobs 1974, 303). As early as 1515, merchants had already discovered that Solor offered a safe haven on this long voyage. They quickly established local contacts and built houses on the coasts (Jacobs 1974, 301). However the coastal inhabitants of Solor and the neighbouring islands tended to be Muslim. They were known locally as Pajis and were antagonistic towards the inland mountain people who were called Demon.

When the Jesuit Friar Baltasar Dias visited Solor in 1559 he discovered 200 Portuguese from Malacca wintering on the island, presumably waiting for the December and January storms to subside (Jacobs 1974, 299-307). The Portuguese had already made many converts among the local Moslem population, including four chiefs. In addition Dias reported 200 Christian converts at a village on East Flores. Over the years a growing population of mixed-race Catholics had developed on the island, making a profitable living by shipping sandalwood out of Timor. These so-called Topasses (termed by the Dutch 'black Portuguese') were even more despised by the endemic Solorese Muslims than the Portuguese.

In 1561, the new Bishop of Malacca sent three members of the Dominican Order to Solor under the leadership of Frey António da Cruz (Jacobs 1974, 495). They chose to settle at Lohayong on the north eastern coast of Solor Island, a region under the political control of Javanese Muslims. Feeling threatened by their Muslim neighbours, they soon abandoned their houses on the beach and erected a lontar palm palisade (Barnes 1987). In 1563 a fleet of Javanese craft sailed from central Java determined to expel the Portuguese from Solor. They succeeded in burning down the palisade, but its occupants were saved thanks to a passing Portuguese man-o-war.

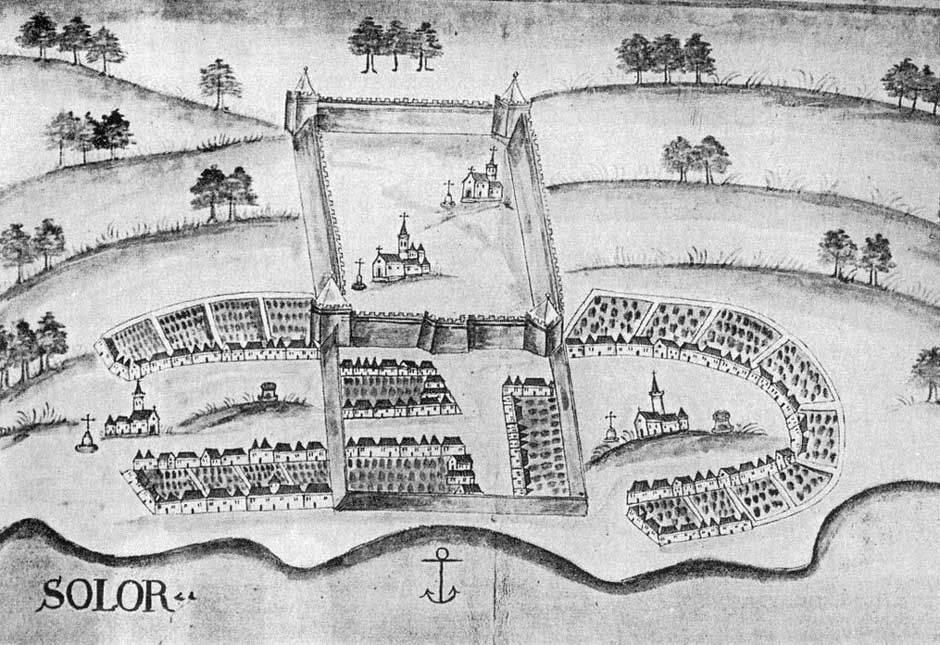

In 1566 the Dominicans built a limestone fort on Solor with five bastions defended by cannon (Barnes 1987). They constructed a well, a church and a seminary for 50 students. To the west of the fort was a local village with around 1,000 inhabitants with its own local leader and church. To the east was a village with around 2,000 lay Portuguese, soldiers and foreign Christians. From 1585 the viceroy of Goa appointed captains to head the fort (Thomaz 2017).

Fortazela de Solor, possibly based on a sketch made before the first Dutch attack of 1613. By Teodoro de Matos and very similar to the drawing of Pedro Barreto de Resende published in 1635.

The Portuguese had earlier built a fort on Ternate in 1523 and started another on Banda in 1529, although the latter was never completed due to local resistance. After the brother of the Portuguese governor of Ternate assassinated the Sultan of Ternate, the latter’s brother instituted a campaign of revenge against everything Portuguese and Christian. In 1574 he laid siege to the fort and expelled the Portuguese, thus increasing the strategic importance of the remaining fort on Solor. The Solorese too wanted to expel the Portuguese and sent envoys requesting military assistance from the Sultan of Ternate. Although an attempt was made to assemble an invasion force on Buru, nothing eventually transpired (Barnes 1987, 220).

In the end, the demise of the Solor fort came about because of the behaviour of its own Portuguese commander. Local Muslims and Christians became resentful of the tyrannical behaviour of the fort’s captain, Antonio d'Andria, who had imprisoned the chief of Lohayong, used forced labour, stole native merchandise and infringing local adat. In 1598 the chief of neighbouring Lamakera led an attack against the fort, burning most of the buildings and churches. The Solorese maintained the uprising for eight months, destroying many of the satellite mission stations on Solor and Flores.

The Portuguese authorities in Malacca retaliated in the spring of 1599, sending a fleet of ninety boats to obliterate Lamakera. The surviving Christian converts at Lamakera quickly reverted to Islam.

In 1602 the Sultan of Makassar (Goa) was persuaded to send a fleet of forty boats and three thousand men under the command of Dom João Juang to attack the Portuguese on Solor and Ende Islands, along with their allies at Sikka Natal. By chance the fortress on Solor Island was strongly manned by the crew of a galleon that had been stranded the previous year off the eastern tip of Java. Seeing that the fort could not be taken easily, Dom João attacked Sikka instead.

In 1603-1604 the fort on Solor was burnt down again and a Chinese builder was engaged to reroof the buildings with tiles (Barnes 1987).

Return to Top

The Ende Island Mission

Ende Island had already become an important trading post prior to the arrival of the first Europeans – an entrepôt for sandalwood, slaves and firearms visited by Chinese, Arab, Malay, Javanese, Bimanese, Goanese and Bugis merchants. Its natural harbour offered one of the few safe havens along the dangerous southern coast of Flores.

Ende Island

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Dominicans on Solor had established twenty different mission stations on the coasts of Solor, Adonara and eastern and central Flores, with one on Ende Island and five located around the Bay of Ende (Visser 1925, 292; Lewis 2009, 197-198). The Dominican presence on Ende Island dates from at least 1560 while the station at Krowé seems to have been founded between 1561 and 1575.

Dominican mission stations on Flores, Adonara and Solor in the sixteenth century

(Lewis 2009, 198)

The mission on Ende Island faced hostilities from Javanese Muslim raiders and around 1570 many islanders were forced to temporarily flee to the mainland (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 78). In 1588, the Dominican Friar Simao Pacheo persuaded the seven thousand inhabitants of the villages of Numbas, Charaboro and Curolallas to band together, convert to Christianity and to build a defensive wooden fort, which became known as Fortoleza de Ende Minor. This was quickly burnt down by the ravaging Javanese.

In 1595 the Dominican friars erected a coral fort – Forte de São Domingos also known as Fortaleza do Ende Kecil – with help from Larantuka. Its first commander was captain Pero Carvalhais (Ramerini 2011). This too had to be rebuilt in 1599 after yet another attack by the Javanese. The church of São Domingos was built inside the fort while outside several Portuguese kampongs, referred to as 'Old Solor', grew up around it - Numbas, close to the fortress; Currolalas on the left side, with the church or chapel of Santa Catarina de Sena; and Charaboro on the right side with the third church or chapel of Santa Maria Magdalena. The population was said to have numbered 7,000 people (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 78).

Countenance and clothing of the Portuguese in the East Indies, both civilian and military. Voyage ofte Schipvaert van Jan Huygen van Linschoten, Amsterdam, 1596.

However, Portuguese presence fuelled local resentment and in 1602, Ama Kira, the native headman of Mari on Flores, persuaded the Sultan of Goa (Makassar) to mount an attack against the fort on Ende – as already mentioned above. The fleet commanded by Dom Joao Juang initially targeted the fortress on Solor Island but, seeing that it could not be taken easily, attacked Sikka instead, loosing one hundred men in the process. His luck worsened when he encountered two Portuguese ships sent from Solor, which destroyed four of his ships. Meanwhile a local friar on Flores sent advanced warning to the Christians on Ende, who were able to repel the impending attack. After the defeat, the Sultan of Goa sent rice to Solor and concluded a peace treaty with the Portuguese (Rouffaer 1923-24, 209-210).

Local Muslims drove many Portuguese off the island in 1605, forcing them to settle at the new village of Numba in the sheltered bay of what is today Ende town. When a Dutch expedition visited Ende Island in 1613 it was subject to the Sultan of Ternate but in 1614 fell under the control of an atalaki (headman) from Sikka. In 1617 Friar João das Chagas reported that only Numbas and Charaboro remained Christian, all the other villages had reverted to animism or become Muslim (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 78). The island fort was later destroyed by fire. Ende Island ceased to play any further role in the history of the region.

Some Portuguese must have survived on the island until 1637. When a Protestant minister visited Ende Island in 1638 he discovered that the remaining Portuguese had been killed during the previous year because of the molestation of a local girl.

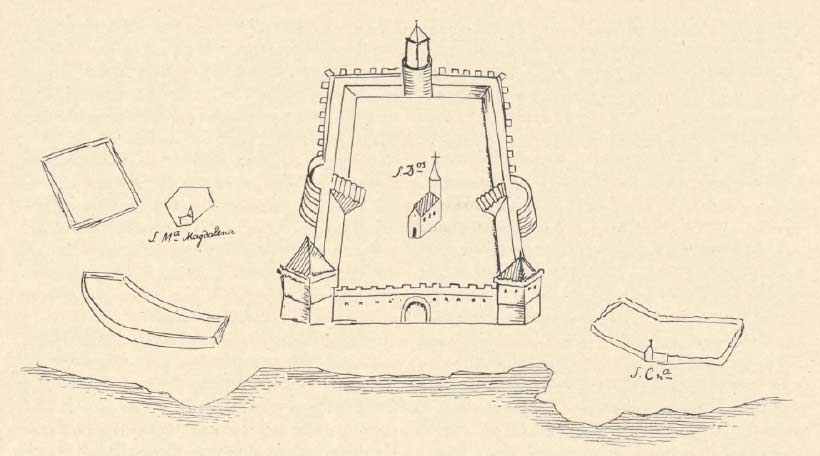

A very early sketch of the fort published in 1635 probably contains major errors but may depict some aspects of its layout shortly after its construction in 1595, including three turrets. The sketch shows rectangular castellated walls with a central entrance flanked by two square corner towers, two side bastions, a rear circular tower and the central church of São Domingos, which we know was later demolished. To the left of the fort is kampong Charaboro and the chapel of Santa Maria Magdalena. To the right is kampong Currolallas and the chapel Santa Catarina de Sena. The boat-shaped kampong on the lower left could be kampong Numbas, close to the shoreline.

A sketch of Fortaleza de Ende Minor by Dr Rassers in a Parisian manuscript of 1635. From G. P. Rouffaer 1923

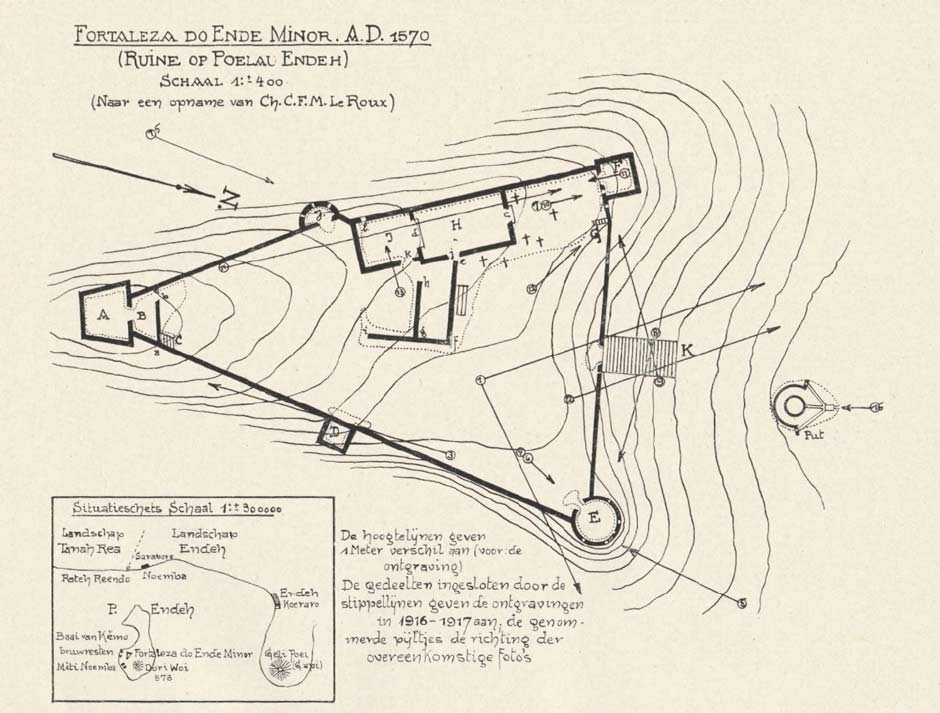

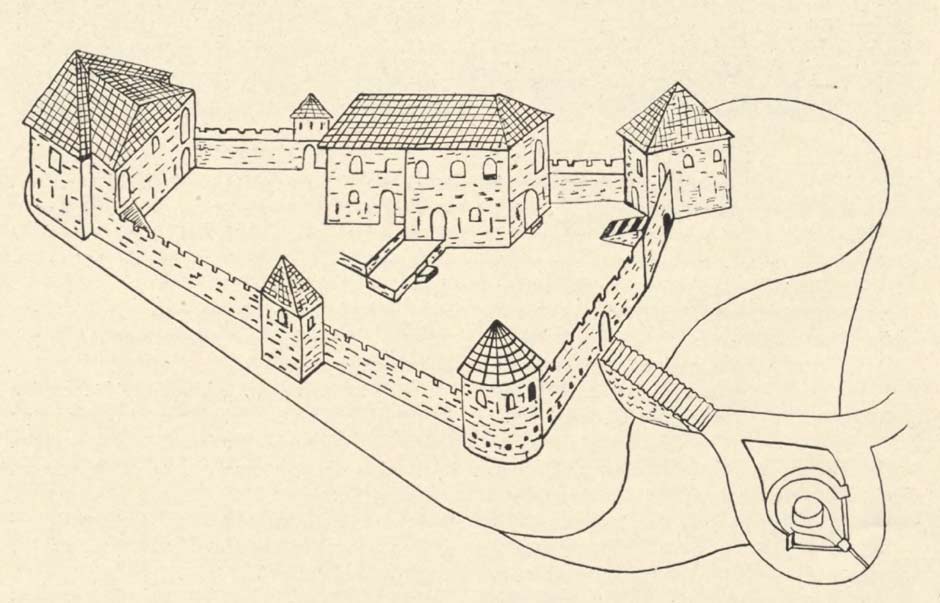

The ruins were was surveyed by the civil engineer Charles Le Roux in 1916 and 1917, who then produced a detailed plan of the foundations. The remains have a quite different triangular layout. The northern wall had a central entrance and was flanked by one round tower and one square tower. There was a four-sided tower at the southern end and several buildings positioned against the western side wall. Steps led down from the entrance to a circular well.

Above: The plan of Fortaleza de Ende Minor made from the survey of Charles Le Roux in 1916-1917. Below: A sketch illustrating how the fort may have appeared before its destruction. Both from B. C. M. M. van Suchtelen 1923.

Fortunately Le Roux also took numerous photographs of the ruins, some of which are shown below.

Above: west face of the ruined fort on Ende Island. Below: The northwest tower. Photographed by Charles Le Roux in 1916-1917

The northeast tower and the northern front wall. Photographed by Charles Le Roux in 1916-1917

On the mainland, the Portuguese Dominicans seem to have lost power to the Muslim native population at some time between 1620 and 1630. Ende town had effectively become a small independent Islamic state, ruled by its own Raja. Portuguese influence over the region had effectively come to an end. Nevertheless, Portuguese missionaries remained in the region until 1772.

Return to Top

The Dutch on Solor

As part of their struggle against the Spanish Habsburgs, the Dutch established the VOC in 1602 to challenge the exclusive trading rights of the Iberian powers in the East Indies. The company quickly set out to eliminate the power of Portugal by attacking every Portuguese stronghold, working their way from east to west (de Roever 2005, 219). In 1605 the Dutch seized the Portuguese fort on Ambon without a fight and then demolished the Portuguese fort on Tidore (Widjojo 2008, 22). The Dutch returned in 1607 and within a few years had established four forts on Ternate, one on Tidore and another on Halmahera.

View of Ambon, commissioned by the VOC in 1617

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (Artwork in the public domain)

Thanks to encouragement by the King of Buton, the Dutch authorities on Ambon hatched a plan to dislodge the Portuguese on Solor. They commissioned the Dutch captain of Makian, Appolonius Schotte, to lead the attack, supported by troops from Temate and Buton. He arrived at Lohayong (today known as Lewohayong) at an opportune time when some 500 of its occupants had gone to Timor searching for sandalwood (Fox 2003, 7). With just two warships he laid siege to the fort for 13 weeks, his bombardment reducing the fort and dwellings to ruins. The occupants finally surrendered on 20 April 1613.

Schotte described the Portuguese fort as being well located, close to the shore but on high ground with deep valleys on either side (Lach and van Kley 1993, 1459). The Solor Mission amounted to more than 1,500 people, including 110 white lay Portuguese and seven Dominican monks, the rest being of mixed or indigenous origin (De Roever 2002:119-26; Tiele and Heeres 1886-95, I, 12-7; Barnes 1987, 222-223). Their composition illustrates the way in which the Portuguese community was becoming ethnically mixed race. Schotte generously allowed them to travel with half of their possessions to Larantuka in eastern Flores, from where they could be transported to Portuguese Malacca. Some did return to Malacca but a large group led by Father Agustinho da Magdalena remained at Larantuka, located in land-oriented Demon territory that had tended to support the Portuguese against the rebellious sengaji (leaders) from the coastal-oriented Paji. According to a later illustration dated 1656, Larantuka at that time was positioned opposite the islet of Waibalun, several kilometres to the south of the present town, (De Roever 2002, 93, 129 and 307). One important reason for their survival was probably support from other local Catholic groups. According to Schotte, the villages of Lewolein and Pamakayo on Solor were Christian, as were several places on Adonara, while on Flores, Christians were also based at Sikka and Numba on the south coast of Ende.

In 1617 the Vicar-General of Goa, Miguel Rangel, sent João das Chagas and three young missionaries to Larantuka to revitalise the Solor Mission (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 81-82). As mentioned above, Chagas travelled to Ende Island as well as Sikka and Paga, installing parish priests. Some years later the Fathers of Malacca dispatched priests to Solor Island under the leadership of Friar Miguel Rangel himself. They arrived on 12 April 1630 with nine pieces of artillery and began to restore the main church and monastery (Rouffaer 1923, 143-144). Rangel departed in the autumn of 1633 to take up his appointment as the Bishop of Cochin. This Portuguese presence irritated the Dutch who sent a small fleet to Solor in 1636 but for unknown reasons did not engage with the occupants of the fort. The Portuguese seem to have abandoned the fort a few weeks later.

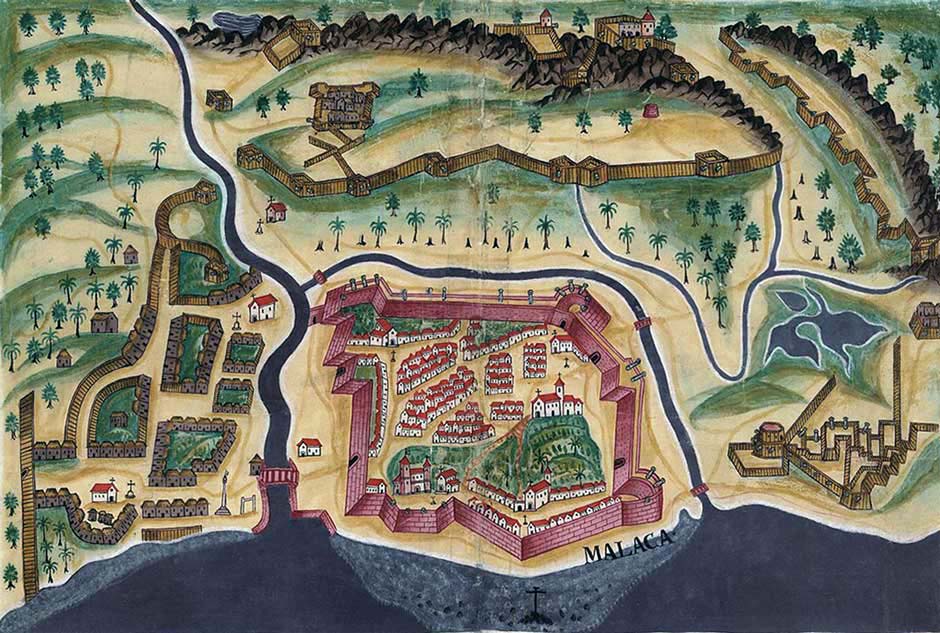

Portuguese Fortaleza de Malaca in 1635. A drawing by Pedro Barreto de Resende from Livro das Plantas de Todas as Fortalezas, a compilation of Portuguese fortresses in Asia made by António de Bocarro in the 17th century for King Phillip IV of Spain

In June 1640 a VOC fleet blockaded the strategic Portuguese fort of Malacca, their forces soon strengthened by reinforcements from their ally, the Sultan of Johor. After a long siege, the fort finally fell in January 1641. The Portuguese in the Far East were left with two remaining bases – Macau and Larantuka. Sensing its new isolation, the ruler of Tallo in south Sulawesi attempted to exert control over Larantuka, dispatching a large fleet to attack the small town. Its houses and church were destroyed but the inhabitants fought back and killed 300 attackers, forcing them to retreat.

Meanwhile Dutch forces led by Willem van der Beeck reoccupied the fort on Solor in 1646 (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 84). However they only held Fort Henricus for two years. It was destroyed by an earthquake in 1648 and was abandoned in ruins.

Return to Top

The Makassarese move to Ende

The Dutch now had their eyes firmly fixed on the strategic Islamic trading port of Makassar. In 1660 a large Dutch fleet passed through the Straits of Larantuka on its way to attack Makassar. Although it did not threaten Larantuka, most of the Larantiqueros left to seek refuge on Ende Island (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 86).

After threatening to destroy the town, Makassar signed a treaty with the Dutch, agreeing to expel all the Portuguese from the port. Many relocated to Larantuka. In 1662 Portugal and Holland signed the Luso-Dutch Peace Treaty, ending hostilities in the region (Boxer 1948. 180). The Larantiqueros led by the families da Costa and Hornay were left to advance their commercial interests on Timor Island.

The Dutch attack on Makassar in 1660. The fortified city and the palace of the Sultan lay between the two rivers. (François Valentijn 1726)

In 1664 merchants in Makassar dispatched a fleet of 28 ships with 1,000 men to Flores to protect their interests from the Topasses. They settled at Ende and were soon joined by a further 8 ships and 600 men. They interbred with the local population creating a mixed-race population known as the ‘coastal Ende people’. The natural mainland harbour at Ende town soon emerged as the main entrepôt of central Flores, eclipsing Ende Island. Ende increasingly dominated trade across the Savu Sea, including the Sumba slave market.

The port of Malacca under Dutch rule 1665

Gezicht op de stad Malakka van de zeezijde, Johannes Vingboons, Amsterdam

(Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam, Creative Commons Licence)

As early as 1691 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) temporarily installed a posthouder at Barai, a coastal village 6km west of Ende. In 1756 Ende was supplying the VOC with cinnamon but it was not until 1793 that the VOC concluded a formal contract with the Raja of Ende – just before its charter expired in 1799. The assets and affairs of the VOC came under Dutch government control, although its possessions were temporarily administered by the French and later the British following the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars. During the interregnum, in 1812, the Bugis inhabitants of Ende expelled the remaining Europeans. When the Dutch resumed their colonial rule in 1816 they operated a policy of minimal direct involvement and Ende was placed under the jurisdiction of Kupang.

Return to Top

Piracy and Unrest

In 1836 the Dutch post at Atapupu on Timor was overrun by pirates from Larantuka and Ende. In 1838 the Dutch responded to this attack and the ongoing slave trade, ordering Captain Paling, the commander of the corvette H.M. Boreas, to proceed with his vessel to Kupang. There the Resident ordered him to burn and destroy any of the kampongs used by the attackers along with any of their vessels. Accompanied by the war brig Siva he first sailed to Larantuka, dispatching a landing party to set fire to the kampong and destroy a native fort. Proceeding on to Ende, a seond landing party went ashore on 14 May and set fire to all of the houses they could reach, incinerating 30 local merchant perahus on the beach and 18 others in the roadstead.

On board the Boreas, Lieutenant Commander W. T. Baars left us a description of Ende Bay:

.... one reaches the far projecting promontory forming an almost quadrangular peninsula, which on some maps bears the name of Tandjung Aloso. On this little peninsula rises a mountain of fire, which bears the name of Gunung Api, and behind it, on the promontory connecting it to the island, a second summit called Table Mountain. Westward of this peninsula forms the beautiful and vast bay of Endeh. The coast is mostly rocky here, but at the extreme eastern inlet of the bay, where the kampong Ambugaga is situated, the beach is exceptionally of blackish sand. The kampong itself is (or at least was in 1838) fairly well built, the houses are more spacious and higher than those of other kampongs in these regions ....

In 1839 the Dutch concluded a contract with the Raja of Ende, Arubusman I, who recognized Dutch authority and agreed to cease slave trading, a promise that was short-lived. The Dutch also sent an Arab prince from Kalimantan to Ende to establish a horse-trading business. He subsequently moved to Sumba, extending his interest into the local slave trade. The Dutch despatched a Malay-speaking posthouder to Ende in 1855 as an observer but the trade in slaves continued – an 1860 report describes the coastal people on Solor hunting down the mountain people to be sold as slaves at Ende.

In 1861, Raja Arubusman II of Ende concluded another long contract with the Dutch government, replacing the former contract of 1839. During this period, the Dutch government maintained a policy of minimal direct involvement. For example, in 1868, the posthouder at Ende was notified by the Resident of Timor that he had been sent there not to govern but only to observe what was happening in Ende and to monitor Endenese involvement in the slave trade.

In addition to slaves, the Endenese actively traded in food and merchandise with destinations ranging from Sikka to Singapore. An 1872 report shows that Ende was exporting coconuts, coconut oil, cinnamon, bird's nests and turtle shells as well as coloured glass beads, hand-woven cloth and headscarves. In return it was importing rice, gunpowder, machetes, axes, copper wire, elephant tusks, Makassar cloth and white, red and black cotton (Barton and Dietrich 2009, 17).

Without military support, the Dutch-appointed posthouder based in Ende town was essentially a hostage to the unruly Endenese kampongs and totally powerless to intervene in the Endenese slave trade on Sumba. Since the main currency for slave trading was firearms, localised warfare between the various domains had become widespread across central Flores. When the Endenese kampongs went to war in 1878, the posthouder fled to Ende Island (Suchtelen 1921, 21). The next posthouder could do nothing when fighting erupted between the north and south kampongs in Ende. He was even forced to supply one of the village leaders with six packets of gunpowder and 80 cartridges. After the posthouder intervened to settle the dispute, his residence was fired upon (Vries 1910, 22-23). A party of villagers attacked the posthouder’s residence again the following year and one of his servants was killed. One important rebel leader was Bara Nuri, a mosalaki from Woloare, who was also involved in the Sumba slave trade.

The mosalaki Bara Nuri

In 1879 the Resident of Timor split the afdeeling of Flores into five onderafdeeling – South Flores with its posthouder based at Ende, North Flores with a new posthouder installed at Maumere, East Flores with a civil gezaghebber at Larantuka, and finally Solor and Alor. At that time Manggarai was under the jurisdiction of Sulawesi.

The five onderafdeeling of afdeeling Flores

During the 1880s, the Dutch managed to capture Bara Nuri, imprisoning him in Manggarai and later at Kupang. He escaped in 1890 and fled to the village of Manu Nggo'o near Ende, rallying his supporters to attack the kampong of Aembonga in Ende town. The Dutch ordered the Raja of Ende, Arubusman II, to arrest the rebel leader but despite surrounding the kampong with 1,100 warriors he failed to do so. The Dutch Governor-General in Batavia dispatched two gunships, the Jawa and Van Speijck, to Ippi Bay, where in March 1891 they bombarded the kampongs of Manu Nggo'o, Roworeke and Watu Roga. Bara Nuri refused to surrender but after the posthouder offered him a truce, he boarded the Van Speijck for negotiations. After accepting a peace agreement, Bara Nuri was arrested and taken to Kupang before being exiled on Java (Dietrich 83, 44).

This incident sparked a period of unrest between the Dutch and the mountain kampongs surrounding Ende. One of Bara Nuri’s key supporters had been Mari Longga, a leader from the northern Lio village of Watu Nggere in Detukeli. In 1895 he fought alongside villagers in Onderafdeeling Maumere against attackers from the district of Mego. Later during the period 1897 to 1899 he was involved in a conflict with Lise, in the southeast region of Onderafdeeling Ende.

The statue of Mari Longa at Wolowona on the outskirts of Ende city

Despite these problems, the modern world was slowly impinging on Ende. In 1892 Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij steamers began calling at Ende harbour and a KPM office was opened in the town. There was now a monthly service linking Ende to Makassar, Bima and Kupang. In 1895 the Muslim Raja of Ende, Arubusman II, died and the Dutch government formally appointed Pua Noté as his replacement and Raja Bicaraas his assistant (Steenbrink 2002, 70).

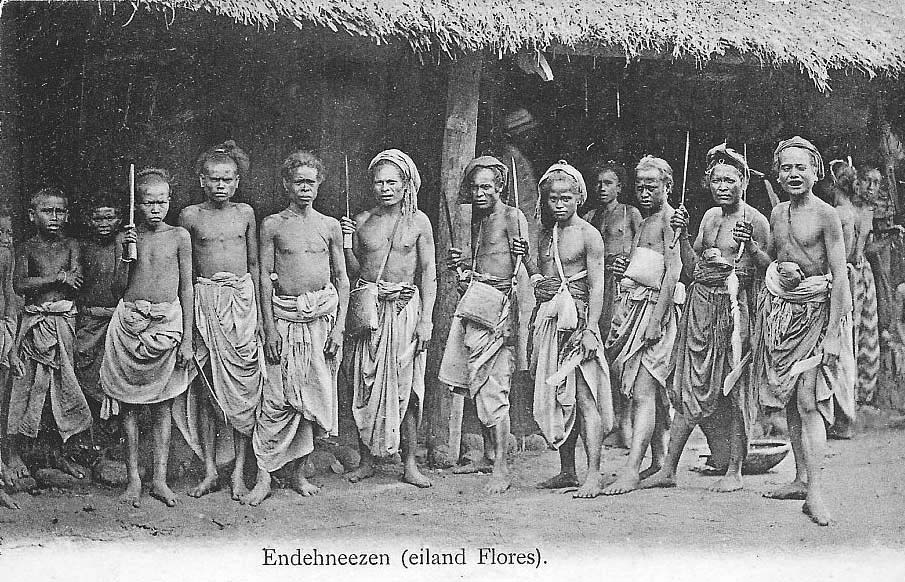

Above: Well armed villagers at Ende town in 1898

Below: A postcard of Endenese men and boys dated 1899

Return to Top

Continue to Ende Regency Part 2

Publication

This webpage was published on 28 December 2021.