Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

The Ilé Mandiri Region

The Baipito and Larantuka Myth of Origin

A Limited Early History of Baipito

Ilé Mandiri in 1928

Ilé Mandiri in 1950

The Ilé Mandiri Clan Structure

Marriage and Bridewealth

Bibliography

Go to: Ilé Mandiri Textiles

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production in the Past

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production Today

Terminology

Women's Costume

The Kewatek Mitan

The Kewatek Lamakera

The Kewatek Kenuma

The Kewatek Makassar

The Kewatek Mowak

The Kewatek Méan

the Tenapa

Men's Costume

The Senai Mitan

The Nowing

The Senai Méan

The Mét

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Introduction

The eastern part of Flores Island, along with the neighbouring eastern islands of Adonara, Solor and Lembata, are mostly inhabited by the ethno-linguistic Lamaholot people. They share a rich tradition of making fine warp ikat textiles which, despite sharing similar characteristics, vary significantly from region to region.

Even in mainland East Flores itself there are important differences between the six separate weaving districts – Tanjung Bunga, Ilé Mandiri, Lewolema, Demon Pagong, Titihena and Ilé Bura. Regrettably much of the literature published on Indonesian textiles takes a simplistic approach to this complex region and attributes many of its textiles to just the one district of Ilé Mandiri.

While this webpage reviews the Ilé Mandiri region and its people, its associated page focuses on the textiles produced in the Ilé Mandiri area.

Map of the east Flores region showing Ilé Mandiri and the town of Larantuka

US Army, Washington D.C.

Return to Top

The Ilé Mandiri Region

Ilé Mandiri (1,484m) is a dormant, double-peaked stratovolcano that dominates the far eastern tip of Flores Island. Its top and flanks are heavily forested and today completely uninhabited. The long, narrow coastal town and port of Larantuka, almost 12km long, stretches along its southeastern foot hugging the shoreline. It faces Adonara Island across the narrow Larantuka Strait, at its narrowest point only two-thirds of a kilometre wide. The lesser peak of Ilé Waikerewak (1,002m) and a ridge of hills lie to the north of Ilé Mandiri, the valley between lined with a string of small villages that run from Oka Bay in the southwest to Delang Bay in the northeast.

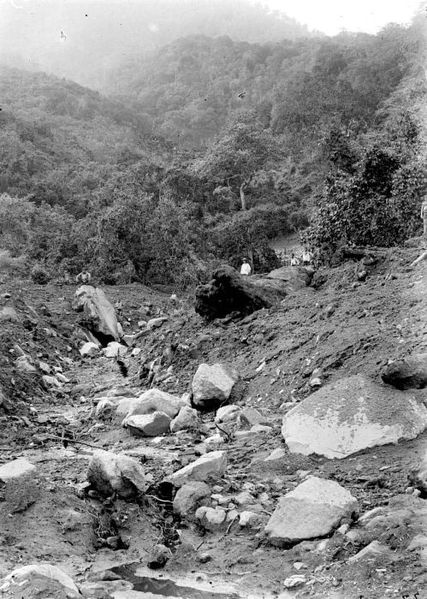

Ilé Mandiri viewed from high above Adonara looking west

Although the volcano appears to have been inactive for a long time, it is not without hazard. In late February 1979 there were four days of intensive rainfall, totalling an incredible 2.5 metres, which triggered flash floods as unstable areas of waterlogged topsoil on the sides of Ilé Mandiri collapsed. Twenty villages were affected and eight were severely damaged. Lewoloba was flooded. Around one hundred people died. More floods on 2 April 2003 killed ten people. In September 2019 hundreds of firefighters tackled a forest fire near the summit, and there were fears that further floods during the rainy season could destabilise the burnt areas and initiate further landslides.

Sunrise over Ilé Mandiri and the town of Larantuka

Larantuka is the capital and centre of local government of East Flores Regency, as well as a major port and commercial centre servicing the islands of Adonara, Solor and Lembata. It has also been the traditional seat of the Raja of Larantuka, a hereditary role that is still occupied today. For over four centuries, Larantuka has also been a major Catholic religious centre and is the location of the Reinha Rosari (Queen of the Rosary) Cathedral, three chapels (Lord of the Mother, Lord of the Son, and Standing Lord), and several shrines. It is renowned on Flores for its extensive annual Semana Santa (Holy Week) celebrations, which attract thousands of pilgrims.

The port of Larantuka

The main street in Larantuka

The Reinha Rosari (Queen of the Rosary) Cathedral in Larantuka, built in 1884

There is no tradition of weaving in the town of Larantuka. Our interest lies in the villages that lie behind the volcano. Today these all lie within the district or kecamatan of Ile Mandiri, which was created as a result of the division of kecamatan Larantuka in 2001. It is divided into eight village areas or desa:

The eight desa of Kecamatan Ile Mandiri, located north of Kecamatan Larantuka

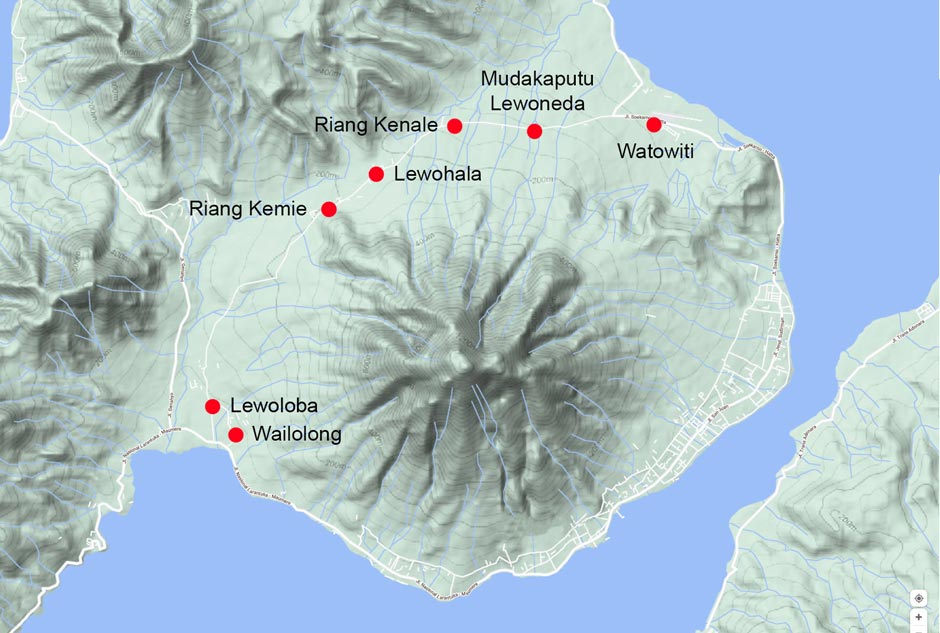

These eight desa accommodate a total of 2,068 households. In 2015 they had a combined population of just 9,551, 51.5% female and 48.5% male. The overwhelming majority of people live in the kampongs of Lewoloba or Leloba, Wailolong (divided into Badu and Oka), Riang Kemie, Lewohala, Riang Kenale, Mudakaputu-Lewoneda and Watowiti. These kampongs are locally known as the Baipito or the seven children (Dietrich 1997, 61-2 cited by Barnes 2009b, 36). In the Lamaholot language the term lewo means a village while riang refers to a branch village. Wailolong means ‘over the water’ and Watowiti means ‘goat stone’.

The villages known as Baipito at the feet of the west and north flanks of Ilé Mandiri

(Image courtesy of Google Maps)

The location of six of the Baipito behind Ilé Mandiri and Larantuka

(Image courtesy of Google Earth)

The villages of Lewoloba (population 1,430) and Wailolong are more modern and prosperous, being close to the trans-Flores highway and Larantuka. Watowiti is now the site of Larantuka’s Gewayenta airport. The largest village to the north is Riang Kemie, yet its population in 2010 was only 1,650. It is home to the large Catholic church of Saint Joseph. There are also Catholic churches in Lewoloba, Wailolong, Mudakeputu and Watowiti, as well as in desas Halakodanuan and Watotutu.

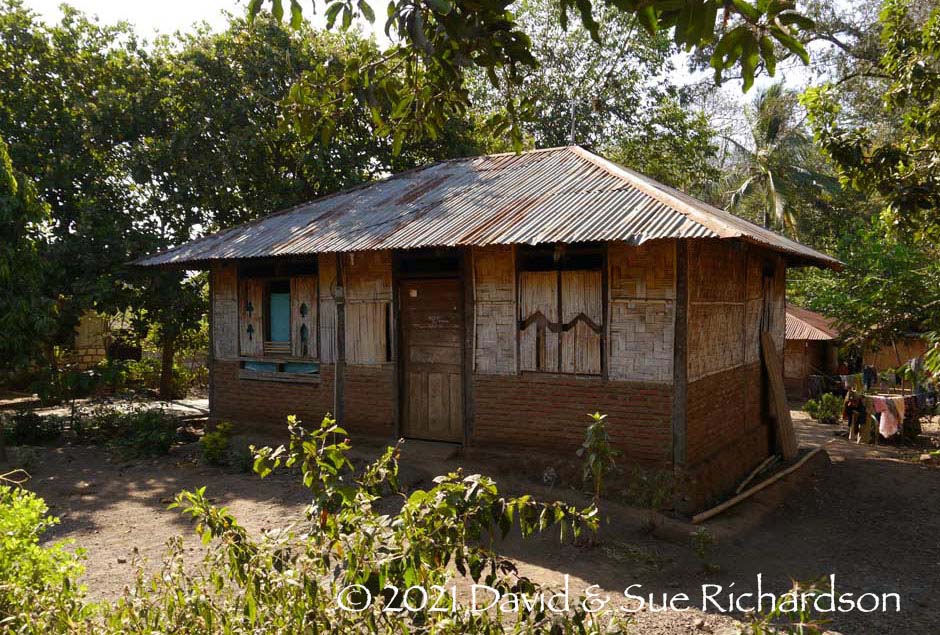

A house in Riang Kemie situated below the volcano

The road passing through Riang Kemie

A simple house by Lewohala

The church of Saint Maria de Fatima in Mudakaputu

The residents of the villages due north of Ilé Mandiri are mostly farmers growing dry hill rice, maize and cassava, along with other vegetables and fruits (Statistics Flotim 2015). The main cash crops are coconuts and cashews, plus smaller amounts of cloves, chocolate and coffee (BPS 2017). Mudakaputu is the main producer of cashew. The local fish catch is tiny.

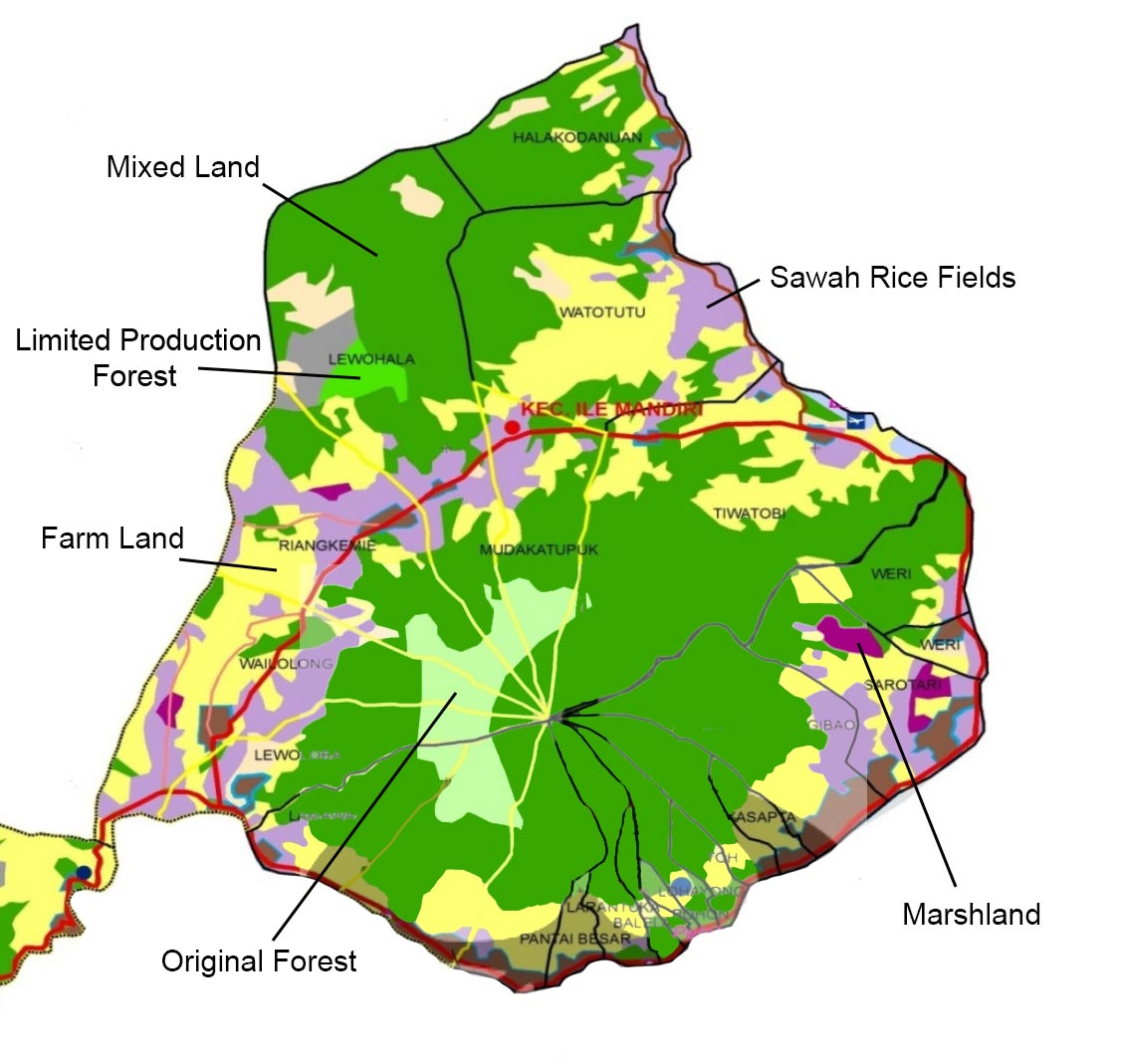

Land Use in Ilé Mandiri and Larantuka

The land area of Kecamatan Ile Mandiri is 7,276 ha, of which 2,276 ha was classified as dry land, gardens and bare land available for cultivation (2009). The harvested areas by major crop were as follows:

| Crop | Area (ha) |

| Dry Rice | 1,364 |

| Maize | 457 |

| Cassava | 141 |

| Cashew | 29 |

| Sweet Potato | 7 |

| Total | 1,998 |

Flores Timor Dalam Angka 2009

The Forestry and Estate Crops Agency in Larantuka is implementing a reforestation project on Ilé Mandiri, which has impinged on land previously cultivated by local farmers (Rohadi et al 2010, 120).

Some people in Lewoloba, Wailolong, Mudakaputu and Watowiti who live closer to Larantuka work in the city or at the airport. In recent decades a few young local men have emigrated to Sabah on Borneo to find work.

Return to Top

The Baipito and Larantuka Myth of Origin

The origins of the people of Baipito and those of Larantuka are closely linked in a complex mythical narrative that is composed of two parallel and symmetrical threads, both of which contrast various opposites, such as mountain-sea, nature-culture and correct marriage-incest. While most local people know a simplified rendition of the story, various similar yet different versions of the full narrative have been documented - one in a handwritten manuscript in the archives of the Societas Verbi Divini (SVD) in Ende. Some of these have been compared and analysed in detail by Dietrich (1995). They have also been discussed by Raymond Kennedy (1955, 167-168), Penelope Graham (1987) and Robert Barnes (2008a).

The narrative begins with two primordial beings, Sén Ma and Adam Eva, who made seven bundles that they then threw away. Ilé Mandiri was made from the last of these. On the summit there were two eggs laid by two birds that hatched into the twins Lia Nura Nura Nama (generally known as Lenurat, sometimes Lia Nurat) and Watu Wélé Apa Utan (generally known as Watowélé). On the mountain they were wild beings with unkempt hair, incapable of having offspring. In order to become normal people they needed to find someone from the coast who could civilise them, marry them and mate to have children.

While on the mountain, the forest man Lenurat was noticed by a girl on the coast – Hadun Boleng Teniban Duli, a Paji girl from Kuku Lewo Pulo, a place that is located close to what is now Pantai Délang. After seeing the light from his fire on Ilé Mandiri she climbed the mountain and met Lenurat and his sister Watowélé. They married and Lenurat became cultivated. After Hadun Boleng taught Lenurat how to mate they subsequently had seven children, five boys and two girls.

Meanwhile another Paji, a princely man called Patigolo Arkian arrived from Wehali on Timor, where he had been harvesting sandalwood. After landing on the beach at Waibalun he saw three lights on Ilé Mandiri. After climbing the mountain he discovered the abandoned hearths of Lenurat and Watowélé. After hiding in the trees he met the forest woman Watowélé and he married her, despite being married already. One of their four sons was the ancestor of the Rajas of Larantuka.

In the narrative the Demon are the mountain people and the Paji are the first inhabitants on the coast. At first the two groups lived together peacefully until a dispute arose and there was a war between the Paji and the Demon sons of Lenurat and Watowélé. The Demon sons had already waged a war against Maumere during which they had been taught how to make iron weapons. Because of this they were finally able to drive out the Paji, leaving the children of Ilé Mandiri free to descend from the mountain.

The children of Lenurat were responsible for establishing the villages behind the mountain. Of the five sons, Belawaburak founded Lewoloba, Kweluk or Keweluk founded Wailolong, Kwaka or Kewaka founded Lewohala and its offshoots Riang Kenale and Lewoneda, Bampowa founded Mudakaputu and Mado Liko Wutun founded Watowiti. Of the two daughters, Beliti Hingi married a man from Adonara and founded Bui Baja Wua, while Ehen Peni married a man from Tanjung Bunga and founded Ebak.

The seven villages were called Keba Baipito Nara Ledu Lema, commonly abbreviated to Baipito, referring to the seven children of the founding ancestors. Their common descent from Ilé Mandiri means that they refer to themselves as ilé jadi (born of the mountain), ilé jadi woka tula (born of the mountain, made of the hill), ilé ana (children of the mountain), or ana-ana Ilé Mandiri (children of Ilé Mandiri).

It seems that the village of Riang Kemie was founded separately by immigrants from Kroko Puken – the twin islands of Lapan Batan located just north of the western part of Pantar Island. These islands were inundated by a tsunami, probably at some time between 1522 and 1525. As the islands were evacuated, refugees from there sought new homes on Pantar, Lembata, Solor, Adonara and East Flores.

Vatter found that in Lewoloba, these immigrant clans described themselves as tana mau or shipwrecked (1932, 71). While some traced their ancestors back to Kroko Puken others, such as the Lohajong clan, believed that their homeland was ‘Sina-Djawa’, which some associate with Malacca.

The original clans have precedence over the later immigrant clans, most of whom can be traced back to the two mythical countries of origin, Sina Djawa in the west, and Kroko Puken (Lapan Batan) in the east.

Together the villages of Baipito and Riang Kemie formed the kakang or traditional district of Mudakaputu, one of ten districts within the realm of the Raja of Larantuka.

Meanwhile one of the grandsons of Watowélé and Patigolo was Sira Demon Pago Molan. He was strong, clever and brave and the local leaders feared him. To extend his power across the other neighbouring kakangs and create his own domain, Sira Demon climbed Ilé Mandiri and danced so violently that he initiated an earthquake, the dust from which rose like smoke from a volcano (Barnes 2008, 345). The kakangs of ten nearby settlements were so impressed by his power that they came together peacefully and acknowledged his authority as the first Raja of Larantuka. The ten separate Lamaholot districts were Mudakaputu, Wolo, Lewoingu and Lewotobi on the Flores mainland, Horowura on Adonara, Pamakayo on Solor, and Lamalera and Lewolein on Lembata.

Note the contrast in status - the founding ancestor of the subordinate domain married an ordinary Paji woman, but the founding ancestor of the Raja married a princely immigrant from Timor.

Don Andre III Martinus Diaz Viera de Godinho (aka DVG), the current Raja of Larantuka

Return to Top

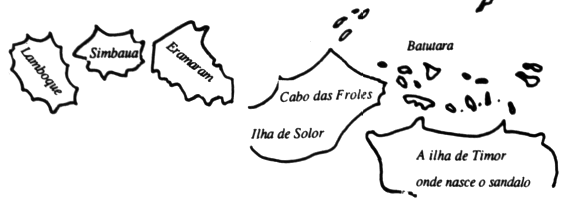

A Limited History of Baipito

The first historical record pertaining to eastern Flores is a Portuguese sketch map of Ilha de Solor naming its easternmost cape as Cabo das Froles – the ‘cape of flowers’. At that time the loosely applied terms Solor and Solot were applied to the whole of Flores and its eastern offshore islands (Pires/Cortesão 1944, 202). The map was drawn by Francisco Rodrigues, one of the pilots on a flotilla of three small ships that sailed along the north coast of Flores on their way from Malacca to the Banda spice islands and back in 1511 to 1512. The name has stuck - today the cape is called Tanjung Bunga which in Bahasa Indonesia means Cape of Flowers.

A sketch of Ilha de Solor with Cabo das Froles marked at its eastern end

Francisco Rodrigues about 1513

The Portuguese were slow to settle in the region. It was not until 1562 that Catholic missionaries from the Dominican Order erected a fort made from lontar palm wood at Lohayong on Solor Island, a convenient staging post on the maritime route to Timor. After being quickly burnt down by Javanese Muslims, it was replaced in 1566 by the stone built Forte de Nossa Senhora da Piedade with five bastions defended by cannon (Barnes 1987, 209-210). Over time a mixed race community of so-called black Portuguese grew up around the fort, increasingly gaining control over the profitable trade in sandalwood, beeswax and slaves from Timor Island. A few settled on the mainland at Larantuka.

In 1613 a Dutch fleet, led by Apollonius Schotte and assisted by troops from Ternate, laid siege to the Portuguese fort for three months. Instead of fleeing to Malacca, the defeated black Portuguese were allowed to join their compatriots at nearby Larantuka, where they eventually became known as Larantuqueiros. As regular visitors to Timor, some settled and intermarried with the Timorese ruling families, establishing their own powerful domains. Because of their Portuguese headwear the Dutch increasingly referred to them as Topasses.

The arrival of the black Portuguese ensured that the Ilé Mandiri region remained allied to both Portugal and the Catholic Church. At that time the indigenous population were led by their own pagan ruler or Raja, the first of whom was supposedly the mythical Sira Demon. He and his successors ruled over the ten kakang, one of which was Baipito, not through force but as a result of their status and esteem. The Raja’s power was also shared with the traditional Larantuka ‘lord of the land’ who oversaw the implementation of customary law. Villages were not taxed, but voluntarily donated gifts on ceremonial occasions.

There were strong trading links between the Larantuqueiro settlement at Larantuka and the so-called ‘mountain villages’ inhabited by the ‘mountain people’ – the terms the Dutch used to describe the native villages and their occupants in the hinterland, specifically the Baipito villages located behind the mountain. There was little scope for food production in Larantuka, so its residents were heavily dependent on the mountain people to obtain their food and supplies. When a Dutchman arrived in Larantuka from Kupang in 1681, he discovered that the prominent Portuguese were either in Lifau with the leader Hornay, or else in the mountains purchasing rice and other provisions (Hägerdahl 2012, 176).

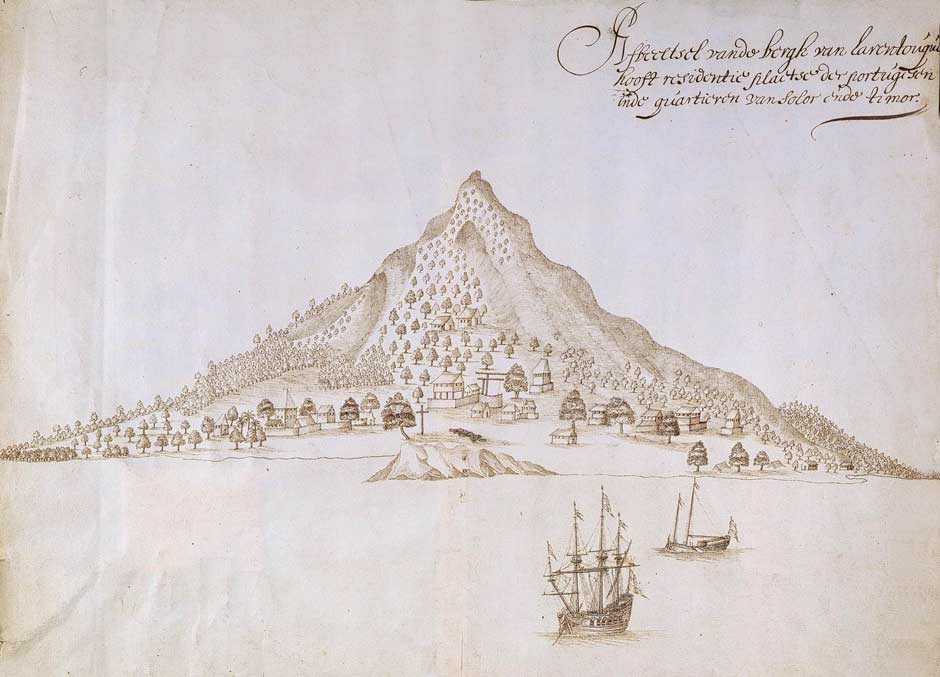

Larantuka in 1672, the main residence of the Portuguese in the Solor-Timor region. Note the cannons on the foreshore. Leupe catalogue, Nationaal Archief, Amsterdam.

It seems that the Rajadom adopted Catholicism at an early stage. Hägerdal mentions three early Catholic Rajas – a Dom Constantino who ruled from at least 1625 until 1661, a Dom Luís in 1675 and a Dom Domingos Vieira in 1702 (2012, 175). The ninth Raja, Ola Ado Bala, who was baptised under the name of Don Fransisco Diaz Viera de Godinho (DVG), established the dynasty of Rajas that continues up to the present day. While some report his baptism occurred in the later 1600s, it may well have been in the 1730s or 40s. At some stage the immigrant Larantuqueiro community that was previously led by the Hornay and Da Costa families seems to have adopted the indigenous Catholic Raja as their leader, thus unifying the two local communities.

Although allied to Portugal, the Raja of Larantuka was essentially politically independent - on the one hand defending the Catholic faith, while at the same time supporting the indigenous pagan kakangs and helping maintain their traditional temples.

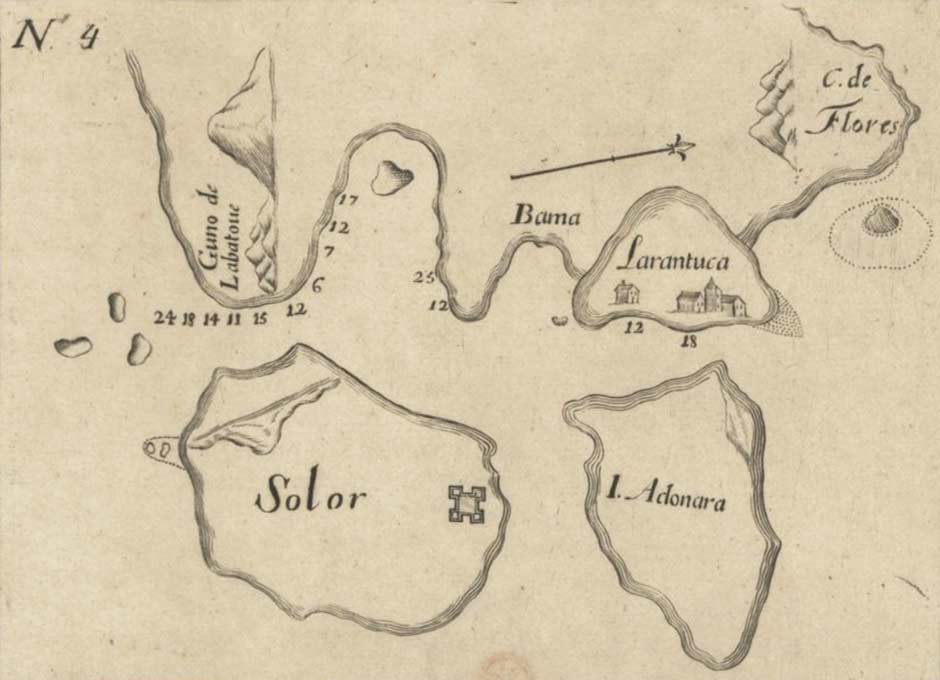

A Portuguese chart of Larantuka in 1700: Ilhas de Solor, Adonara, Larantuca, Cabo de Flores e parte da Ilha de Timor, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

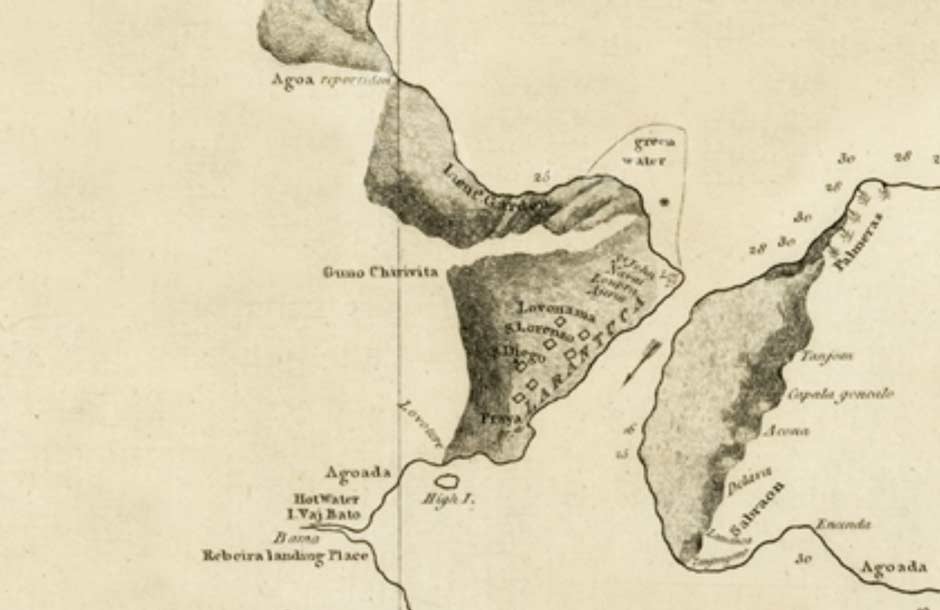

A more realistic map of Ilé Mandiri and Larantuka from 1781: Chart of the Strait of Solor, Alexander Dalrymple, London, ca. 1792, National Maritime Museum, London

We must remember that prior to the early 1900s most of the Baipito villages were not in their present location. The majority of them were located at higher altitudes on the slopes of the volcano. Inter-village disputes were relatively commonplace, mainly caused by disagreements over the ownership of land used for slash and burn farming. Consequently villages were built in inaccessible locations that were easy to defend but hard to attack. This inevitably resulted in harsher living conditions with women and children having to obtain water from afar.

In 1836 the Dutch discovered that merchants from Larantuka and Ende had supplied slaves to Timor. As a punishment they despatched two gunships, which first shelled and incinerated Larantuka before sailing on to Ende (Vatter 1932, 45; Barnes 1996, 15). This event opened up a dialogue between the Dutch authorities in Kupang and the Portuguese authorities in Dili concerning the disputed colonial sovereignty of Timor, East Flores and the Solor Islands. When José Lopes de Lima arrived as the new Governor of cash-strapped Dili in 1848 he set out not only to resolve the conflict over the frontiers, but also to restore the financial health of his administration. In November 1851 he secured an agreement with the Dutch Resident in Kupang, Baron van Lynden, to cede Flores, Solor, Adonara, Lembata, Pantar and Alor to the Dutch in return for the enclave of Oecussi and Maubara and Atauru Island in East Timor. Because the islands ceded to Holland were larger than the territories ceded to Portugal, the Dutch would also make a payment of 200,000 florins (Saldanha 1994, 38-39).

Desperate for cash, Lopes de Lima immediately rescinded authority over Flores and the other Solor Islands in return for 80,000 florins. The Dutch immediately established a small military garrison at Larantuka as a guarantee for the loan.

When Lisbon received news about the agreement they were furious and Lopes de Lima was recalled as a traitor, but died on the passage home. However his agreement could not be annulled and a formal treaty of demarcation was finalised in 1854, but only ratified in 1859 as the Treaty of Lisbon.

The Larantuqueiros or Topasses were also angry that the white Portuguese in Dili had sold them out to Holland. One of the conditions agreed with Lopes de Lima was that those inhabitants who were Catholic (primarily those in Larantuka, Konga and Wureh) would remain Catholic. This condition was secured in article 10 of the 1859 treaty, which guaranteed religious freedom on both sides (Barnes 2009b, 33).

By 1860 Dutch Catholic priests began to replace the Portuguese priests who had previously travelled to Flores from Dili (Fox 1980, 241). More pious than their predecessors, these religious zealots lacked any understanding of the local culture and were therefore shocked by the practices of the indigenous Lamaholot villagers and their korke temples. Their arrival into a world ruled by adat (indigenous customary law), overseen by a bureaucratic colonial system run by inept Dutch officials, would create several difficult decades for the people of Larantuka and Baipito that have been examined in some detail by Robert Barnes (2009b). The episode described below gives us an insight into the relationships between the people of Baipito and both the Catholic Larantuqueiros and the Protestant Dutch administrators at that time.

In 1860 the Raja of Larantuka was planning to allow the ‘mountain people’ to rebuild a dilapidated temple associated with the realm of Larantuka, but the first Dutch priest Jan Sanders strongly opposed this, describing it as a ‘house of the devil’ (Barnes 2008b). In 1862 Sander’s replacement, Caspar J.H. Franssen, discovered the Ilé Mandiri korke and the remains of a sacrifice in a sacred grove, and later another traditional temple at Konga. He instructed Raja Don Gaspar to remove them. The Raja was in an impossible position – pulled in opposite directions by the mountain people on one hand and the church on the other. The Raja said he could not maintain his position without the temple.

When the next Resident of Timor, Isaac Esser, visited Raja Gaspar at Larantuka the following year, several Christian heads asked for his permission to rebuild the town temple. Told that the priest had forbidden it, the Resident noted that the priest had no authority to issue orders beyond those related to church affairs (Barnes 2009b, 40). It seems the temple was erected close to the Raja’s home.

These affairs clearly created tensions between the people of Larantuka and those of Baipito. In 1867 the mountain people murdered eight townsfolk who retaliated by shooting four mountain people. When the mountain people threatened to attack the Raja’s compound he placed cannons in front of and behind his house. In the light of this incident it is surprising that the small military garrison was withdrawn from Larantuka in 1869 (Steenbrink 84). This left the town undefended, greatly strengthening the position of the well-armed Biapito villagers.

It was only in 1873 that the raja tanah or tuan tana (lord of the land) of Larantuka (second only to the Raja himself) converted to Catholicism. During the following year the townsfolk finally took down the temple located within Larantuka, which previously served the entire domain (Barnes 2008a, 347).

Raja Don Gaspar died in 1877 and was succeeded by his half-brother Don Dominggo. Catholic affairs were now in the hands of the Jesuit priest Gregorius Metz, who had arrived in 1863 and later replaced Franssen. Meanwhile another priest had erected a cross with a picture of Christ at the top of Ilé Mandiri. When the following rainy season was delayed and the planting season threatened, the mountain people blamed the Europeans for demolishing some of their temples in Larantuka, for prohibiting the sacrifice of goats and pigs to encourage rain and for desecrating the sacred mountain. The head of Lewoloba contacted the other Baipito villages with a plan to attack the Europeans and local Christians. Poorly defended, the Raja asked for permission to purchase rifles and ammunition, but the Resident rejected this request and sent a warship to Larantuka instead. Meanwhile Metz discovered that villagers were re-erecting a temple in the hamlet of Lewerang to the northeast of Larantuka town, which had been torn down a decade previously. He pressurised the Raja to halt the construction, but the villagers persisted. Fortunately by February the rains had resumed and the threat from the mountain people abated.

In October 1879 a small Demon-Paji feud erupted between the people of Baipito and an East Flores coastal community that fell within the realm of the Raja of Adonara. In order to appease angry spirits following the faulty preparation of a temple beam, warriors from Lewohala needed to offer up heads as a sacrifice and so murdered two people belonging to a Paji community located in the north of Tanjung Bunga (Barnes 2009b, 47). After a failed attempt to murder more Pajis in December 1879, several more people from Tanjung Bunga were killed in March 1880. The culprits were from Lewohala and on their way home they stole five goats and robbed houses in Riang Koli. The Raja of Adonara was incensed, and threatened to retaliate. The civiel gezaghebber of the Solor Islands, E. F. Kleian, advised the Raja to hunt down the murderers and exile them, but the Raja said this was impossible because many other villages had been involved. Klein later named the guilty villages as Wailolong, Lewoloba (Leloba), Riang Kemie, Lewohala, Mudakeputu, Lewoneda and Watowiti – in other words the whole of Baipito.

Just a few days later the chief of Lewoloba and two companions were shot in the coastal village of Waibalun, just to the southwest of Larantuka. It seems there had been a long-running land dispute between the two kampongs. Hearing the news, the inhabitants of Lewoloba began preparing for war. Klein was concerned. Unlike the people behind Ilé Mandiri, Larantuka was poorly armed.

Lacking military resources or an appropriate naval warship in Kupang, the Resident of Timor, J. G. F. Riedel, could offer only limited help. He sent the civiel gezaghebber an armed boat with 30 casks of gunpowder, so that if necessary the Europeans could be evacuated. In the meantime he requested Makassar to send a warship with a 120-stong battalion to Larantuka but sceptical officials in distant Batavia blocked his request. During May 1880 the mountain people attacked Waibalun twice, only retreating after the arrival of the armed warship. They also fired flaming arrows into the homes of some of the Catholic priests.

The Resident argued that it was the Raja’s responsibility to punish the insurgents. If he could not, the Dutch would declare the mountain villages independent and transfer the Rajadom to a local pagan leader. Fearful of his position, that July the Raja led some 2,000 coastal and mountain people against Lewoloba and Wailolong, leading to dead and wounded on both sides (Barnes 2009b, 52). Two further attacks on Lewoloba took place in September and October.

After Resident Riedel was transferred to Ambon he was replaced by W. F. Sikman. Concerned with the unstable situation in East Flores, the new Resident came to Larantuka in December to meet with the heads of the mountain villages and listen to their grievances first hand, one of which was that they had been prohibited from visiting the local markets so could not trade their produce such as tobacco and sirih-pinang. Sikman ordered the Raja to rescind the prohibition and to instruct his kapitan to meet the Baipito chiefs and negotiate a settlement. The Raja declined, fearful of meeting the enemy leaders and concerned at what might happen if the mountain people returned to the local markets. When Sikman threatened to replace the Raja with one of the Baipito leaders he agreed to act and abolished the prohibition.

Unbeknown to the Raja, civiel gezaghebber Kleian entered into secret negotiations with the Baipito chiefs. When he learnt about the talks the Raja was highly irritated and blamed Kleian for all the problems. When villagers from Waibalun killed some Baipito residents at a fight in a local market in February 1882, the Baipito people retaliated, bizarrely attacking hamlets in northern and central Larantuka who had nothing to do with the dispute.

Later that year Resident Sikman was replaced by Salomon Roos, a former gezaghebber of Larantuka. Angered by the dispute, Roos also threatened to depose the Raja if he did not resolve it, but the Baipito villagers were furious and unwilling to negotiate.

Despite this impasse, hostilities between the mountain and coastal villages appear to have ceased by early 1884, for reasons that remain unclear. It may have been because conflict erupted within the Baipito villages themselves.

The Catholic priests appear to have started moving into the Baipito villages in about 1885 (Kennedy 1953, 191). They were initially welcomed, possibly because they came arrived with modern medicines. In Wailolong the first villager was converted in 1890. Conversions proved to be easier in Lewoloba. However the period of amicable relations between the pagan believers and the church would only last until 1912.

Raja Don Dominggo died in 1887 and was succeeded by the 27-year-old Don Lorenzo Diaz Vieira Godinho. Educated by the Jesuit Metz, he was a committed Catholic and had an authoritarian uncompromising outlook. Within a month of his inauguration he had already placed 20 people in the stocks for practising traditional rituals (Barnes 2008b). He quickly began to irritate the Dutch officials, governing his Larantuqueiros in a harsh and irrational manner, while also becoming involved in territorial disputes with the Catholic Raja of Sikka and the Muslim Raja of Adonara (Steenbrink 2002a, 95).

Raja Don Lorenzo II DVG in about 1890

(Image courtesy of KITLV)

Unfortunately for Raja Lorenzo, it was slowly dawning on the Dutch that they needed to change their approach to governing the problematic Outer Islands by taking a more hands-on approach. This would have profound consequences for the people of Baipito. In April 1902, F. A. Heckler took over as the new Resident of Timor in Kupang. On 1 July 1904 he arrived in the port of Larantuka on board the government steamship Pelikaan and ordered the troublesome Raja Lorenzo II to join him, whereupon he was arrested and deposed. After being sent as a prisoner to Kupang he was exiled to Yogyakarta and temporarily replaced by a puppet.

In the same year Colonel Joannes van Heutsz was promoted to the role of Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies. Having succeeded in overcoming a long-running insurgency in the Sultanate of Aceh, Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule.

The next Resident of Timor was J. F. A. de Rooy, who took over from Heckler in March 1905. He was issued with clear instructions regarding this much more active policy. His main task was: To establish a powerful authority in the whole residency, with the implication of a new strategy towards the self-ruling districts, which are the majority of the whole area. The former policy of non-intervention, suggesting that the supreme authority was with the native rulers and not with the colonial authority, should be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70). Attention was initially focussed on central and west Flores, with A. Couvreur installed at Ende in 1906 as the first Controleur of Flores. It was not long before Captain Hans Christoffel led a ruthless campaign to confiscate weapons and register the population. Couvreur’s opinion of the Raja of Larantuka was not high – in 1907 he commented that the Raja’s influence over his ten domains was non-existent (Barnes 2010).

In 1908 work began on the construction of the trans-Flores highway that would link Larantuka to Reo, a challenging and ambitious project that would take almost two decades to complete. The route passed just south of Wailolong and Lewoloba and around the edge of Konga Bay. As the road progressed, the inhabitants of the nearby mountain villages were encouraged to move down to new villages that had been built alongside it (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 241). The Baipito villages were not affected at this stage.

By 1905 the first teacher in Lewoloba had begun teaching Christianity to his pupils (Kennedy 1953, 265).

However it was not until 1910 that Captain J.D.H. Beckering arrived in Larantuka with a company of armed military police tasked with registering the population and collecting firearms. Apparently Lewoloba submitted to the Dutch, but Wailolong resisted (Barnes 1977, 138).

The Dutch looked to the Raja of Larantuka and his kapitans to impose taxes on the village kakangs and requisition corveé labour to construct roads. Not surprisingly villagers strongly opposed these measures, sometimes violently, and the Dutch responded with military force (Dietrich 1985). In 1912 the Dutch conducted military operations against a few of the Baipito villages. In the same year the first church was constructed in Riang Kemie.

Ilé Mandiri on the hydrographical chart produced by the Hydrographic Department of the Naval Ministry, The Hague, June 1911

It was around 1912 that the Catholic pastors began taking a harder line against the beliefs and rituals of the pagan villages, aiming to eventually eradicate them. The people began to resist the pressure to convert, and in some cases there was real conflict. However this did not last. By 1920 many villagers became resigned to the situation, and effectively surrendered to the Catholic Church (Kennedy 1953, 191).

Also in 1912 the acting Raja and his officials chose Servus, the 23-year-old son of Raja Lorenzo II, as the next Raja - a decision consistent with adat. His appointment was endorsed by the local Dutch Controleur A. M. Hens once he had signed the Korte Verklaring (Short Declaration). This was a one-sided agreement in which Larantuka recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies (Barnes 2010, 10). The mountain villagers were delighted with the appointment, and some came to Larantuka with gifts (Barnes 2010, 11).

It was probably a bad choice, as Raja Servus seems to have quickly lost the confidence of both the church and the Dutch authorities and increasingly turned to drink. In 1916 he moved his residence to Waiwerang on Adonara and three years later asked to resign. As the Raja’s oldest son Lorenzo was only five years old, the Dutch appointed his second in command, Antonius Balantran de Rosari, as a temporary replacement. He had earlier worked as the mandur jalan, the overseer of road workers (Barnes 2010). Obviously Lorenzo was the only legitimate successor, being from the Dias Vierra Godinho line.

In 1915 the Burgerlijke Openbare Werken (Department of Civil Public Works) of the Netherlands East Indies appointed the civil engineer Charles Constant François Marie Le Roux to oversee the trans-Flores road project. This was a fortunate choice as during his four years on the island he used the opportunity to photograph the locations and villages along the route and the local people’s daily life, increasingly becoming more interested in ethnography than road construction. He photographed people and villages along the route, such as at Wairunu near Oka Bay, but we have yet to identify any images relating to the Baipito.

Above and below: Dry riverbeds on the slopes of Ilé Mandiri shortly after a flood. Probably photographed by Charles Le Roux at some time after 1915

Women and children in East Flores with hollowed out gourds for collecting water, photographed by Charles le Roux at some time after 1915

Le Roux also produced a detailed map of East Flores which is not yet in the public domain (Verkenningskaart van de Onderafdeeling Oost-Flores en Solor-eilanden).

As already noted, prior to the introduction of tighter governance by the Dutch in the early 1900s, many Baipito villages were located higher on the slopes of the volcano. The residents of Lewohala explained to us that their original village was Huluhala on the slope of Ilé Mandiri, but the villagers then moved down to Sirigokok at a lower level. The location of Sirigokok was on the northeast flank of Mandiri. They had to walk down from the village to get water, and were eventually forced to move to Lewohala at the foot of Ilé Mandiri by the Dutch in 1916, after John Carol had built an easy access road.

When Vatter visited the Baipito villages in 1928 he found that Watowiti had been moved from the heights to its current location just over a decade previously (1932, 46). Apparently when the local priest first arrived in the new village, the women and children fled in horror. Wailolong was relocated twice, firstly when the Dutch moved it down from the mountainside to the crossroads at Oka by the coast in 1913 and then, faced with a potential revolt, back from the coast to its present position in 1922 (Kennedy 1953, 72 and 258). Lewoloba was only moved once, although Vatter claimed – perhaps mistakenly – that it remained in the location where it was originally built.

A Dutch pastor near Larantuka in around 1920

Return to Top

Ilé Mandiri in 1928

It is not until 1928 that we get a more accurate picture of the Baipito villages, especially Lewoloba. On 9 November of that year the German ethnographer and collector Ernst Vatter and his wife Hanna disembarked at Larantuka harbour from an old Dutch steamship, the KPM De Clerq, which had departed from Surabaya nine days previously. They had been sent to eastern Indonesia on a seven-month-long collecting expedition on behalf of the Museum of Ethnography in Frankfurt.

Ilé Mandiri and the landing at Larantuka, photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1928

On 14 November they travelled to Lewoloba (which Vatter calls Leloba, an abbreviation) in a rickety car that they had been lent by the Raja. They remained there for three weeks before returning to Larantuka. It was the longest they spent in one place on their whole expedition and gave them a fine introduction to the culture of the Lamaholot people. By now a road existed through almost all of the villages behind Ilé Mandiri so they could easily visit them.

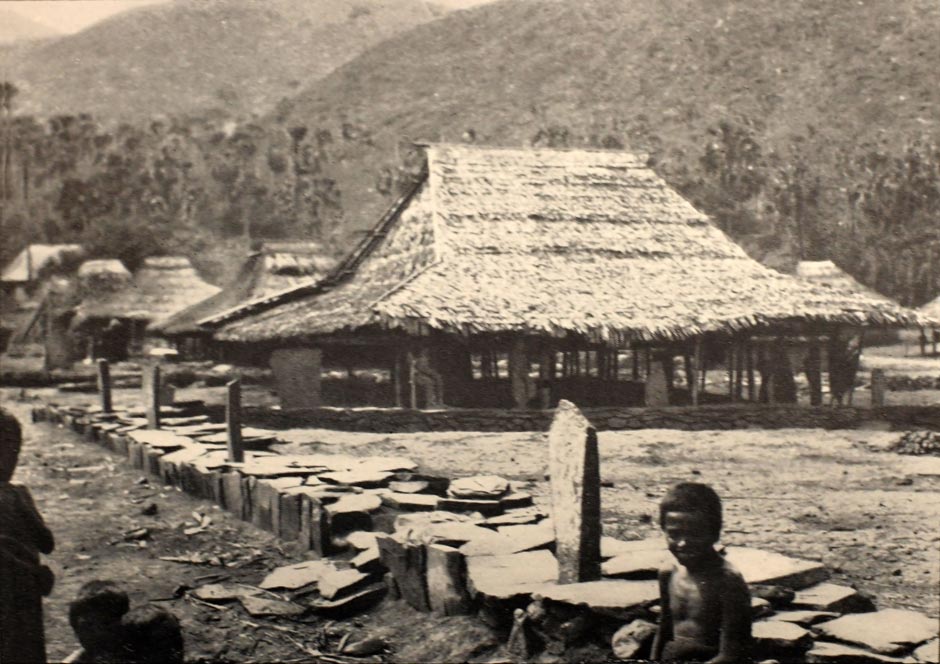

Lewoloba was the exception, accessed on foot from the road at Wailolong by means of a long narrow path through thick forest. It was an old village, situated on a small plateau with a terraced scree slope behind, which Vatter (possibly mistakenly) believed was still located where it had been originally built. Being closest to Larantuka, it also had a higher proportion of Christians than all of the other Baipito kampongs. Lewoloba had a population estimated at 600 to 700 with a church, a parsonage and about 70 houses - each house accommodating an extended family. Some of the houses were arranged in parallel rows on separate rising terraces held in place with retaining rock walls.

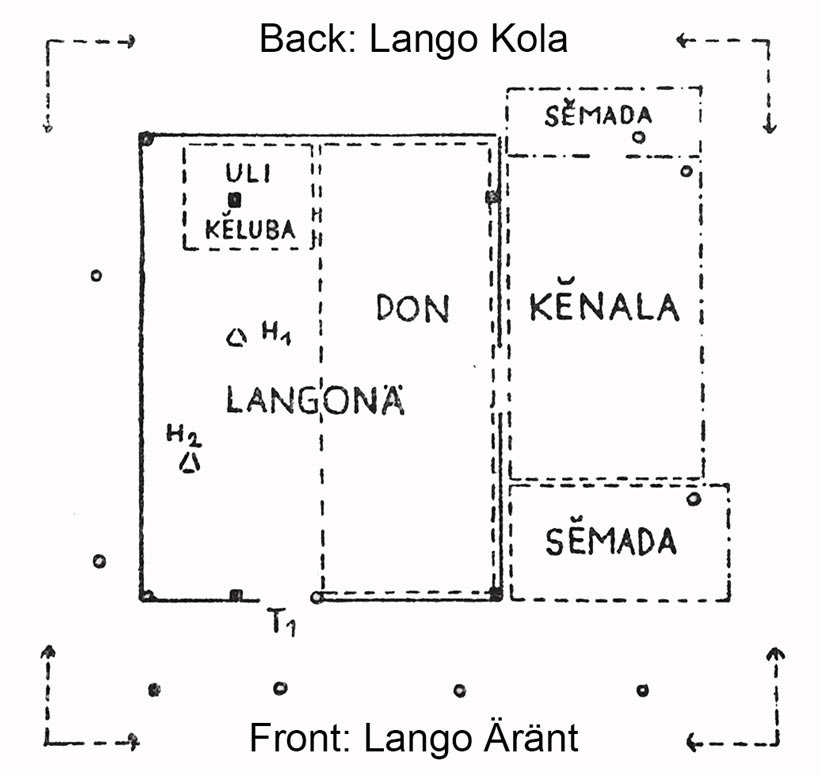

The houses were constructed around four robust vertical pillars connected by cross beams. The grass-covered roofs were made from a bamboo frame covered with bundles of alang-alang sword grass. They a short ridge and four sloping sides which overhung the walls, creating a veranda on all four sides. The internal living space was raised above the ground on a bamboo platform and was sectioned into two parts:

- a rectangular kitchen/living room, the langonä, with slatted windowless bamboo walls, which contained the hearth and cooking pots stored on the raised uli këluba platform, and

- a bamboo bale platform called the don, which was used as an eating and sleeping place for the women and small children and a storage area for baskets containing the festival sarongs and dance jewellery, protected from the moths by tobacco leaves.

Note that the Lamaholot word bale is a loose term that has several meanings ranging from a raised platform, an unwalled building, a meeting hall or a building (Waterson 2006, 228-229).

There was no chimney. There were further bamboo bale platforms built outside, under the projecting roof or outside in the open air in front of the house and this is where most women carried out their food preparation, spinning, weaving or basket-making. The bale just outside of the don was the called the kenala, on each side of which was a slightly lower bale, called the semada, which served as an entrance and forecourt. Another higher semada was used as a storage room (Vatter 1932, 69).

Vatter’s plan of a house in Lewoloba

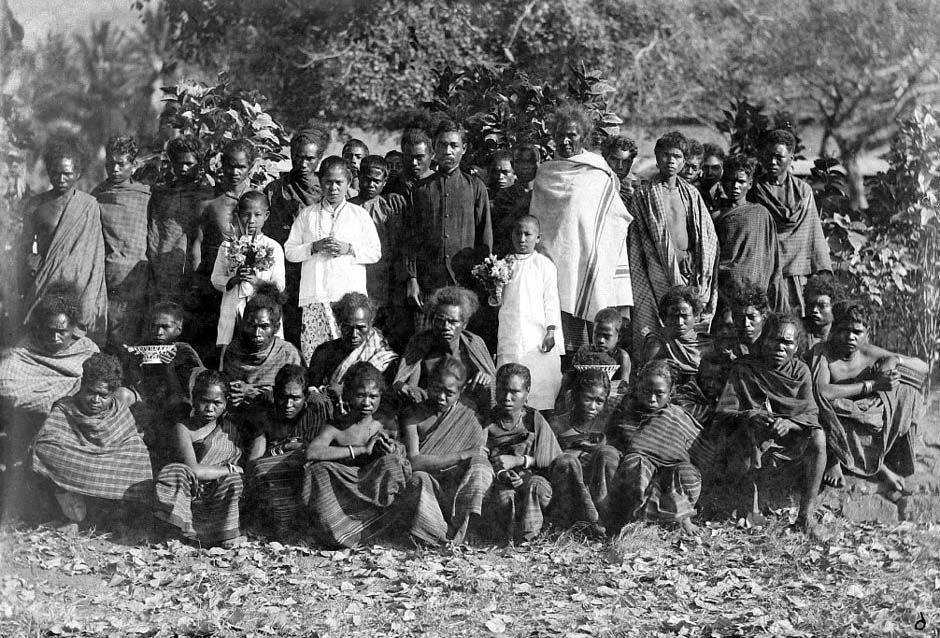

The Vatters were struck by the wide racial diversity of the kampong’s inhabitants – some had a slim and graceful stature and fine features (clearly Austronesian), while others were big-boned stocky figures with broad noses and frizzy hair (clearly Papuan). Many were suffering from health issues such as sore eyes and malaria, as well as from wounds caused by walking barefoot or working in the fields. There was no sense of hygiene and there was widespread uncleanliness. Women and girls had to routinely walk down to the coast to wash themselves and to fetch water from a spring using big hollowed-out gourds.

Agriculture and the collection of raw materials for construction and manufacturing took up a huge proportion of the day. The men worked in the fields located down by the coast using simple tools such as digging sticks and hoes, but a few went out to hunt armed with lances, bows, and arrows. Many went out in the morning to tap the sap of the lontar palms to obtain juice and to make wine. The Dutch had banned the distillation of lontar wine to make sopi liquor, but this still continued in secret. Meanwhile the women foraged or collected fish at low tide in funnel-shaped rattan baskets. Although there were many goats, pigs and chickens in the kampong, these were mainly kept for sacrifices, not for food. To go to school the children walked down to Wailolong.

A house in Leloba with fish traps and men setting out to tap palm sap

Ernst Vatter 1928

The Lewoloba korke was located away from the village on the slope of the mountain, constructed with six massive vertical pillars connected at the top by heavy cross beams and roofed not with grass but with palm leavess. A wide bamboo platform was suspended between the posts and there were no walls. In the past it housed the village treasures, especially large elephant tusks, but in 1928 it contained only a goatskin drum. The dance arena and the sacred stones normally associated with a korke were missing, so festivals were no longer celebrated there. However the Vatters were invited to a feast following the re-roofing of a korke in neighbouring Wailolong – see below.

By now Riang Kemie was regarded as a kampong in its own right, unlike Riang Kenale which was still a branch of Lewohala. Only a lewo had the right to have its own korke. Thus Riang Kemie had its own korke, but the residents of Riang Kenale had to use the korke in Lewohala. Each of the main pillars of the roof in the Riang Kemie korke belonged to one of the long-established village clans.

The korke in Riang Kemie, showing the walled dance arena and the upright sacrificial stones set up by the four raja tuan clans. Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1928

Some months after the Vatters departed from Ilé Mandiri, hostilities broke out yet again between Lewoloba and Waibalun – in this case because the latter had planted coconut palms in a disputed area of land.

According to the 1930 census, the population of Baipito was 3,606, 1,973 (55%) of whom claimed to be Christian:

| Kampong | Population |

| Watowiti | 251 |

| Mudakaputu | 251 |

| Lewoneda | 310 |

| Riang Kenale | 221 |

| Lewohala | 571 |

| Riang Kemie | 857 |

| Lewoloba | 570 |

| Wailolong | 578 |

There were slightly more females than males (Kennedy 1953, 197). The average size of a family was around eight.

Sadly we know almost nothing about Baipito during the 1930s and 40s, apart from the fact that a small war occurred between Wailolong and Riang Kemie around 1935 (Kennedy 1953, 73). In 1938 Raja Antonius stepped down to allow the 24-year-old Lorenzo to take over as the legitimate Raja (Hangelbroek 1977, 140). Don Lorenzo Oesi Diaz Vieira Godinho III was to become the last official Raja of Larantuka, ruling through the Japanese occupation until 1962, when the system of Rajadoms was abolished.

On 17 May 1942 the Japanese minelayer Wakataka arrived at Larantuka and special naval landing forces (SNLF) came ashore and immediately occupied the town (Bertke et al 2014). The Dutch had left Larantuka undefended. At the beginning of 1941 there had been four Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) brigades stationed at Larantuka, but in December they were all redeployed to Kupang. We know from other parts of Flores that the four-year long occupation would have created many hardships for the local people. Apparently the Baipito villages feared that the Japanese would kill all the Christians but not the Muslims. Some changed their costume and began wearing the Javanese songko hat (Kennedy 1953, 73).

Ilé Mandiri in 1950

In 1949 the Yale anthropologist Professor Raymond Kennedy embarked on a 15-month research trip to the former Dutch East Indies, which had only just gained its independence. He arrived in Jakarta on 12 July 1949 and started his intensive fieldwork in southern Sulawesi.

He reached Larantuka on 20 December 1949 having departed Ende by jeep that morning, passing through Maumere at noon. He described Larantuka as ‘having been asleep for a long time’ and later as a ‘miserable spot’ (1953, 37 and 45). He left at Christmas but returned to Larantuka on 6 January 1950, stayed until 11 January, then returned from Ende for one last visit on 16 January to spend 3 days in Lewoloba, leaving Larantuka on 20 January to return to Ende. The American from Massachusetts did not enjoy his time on Flores Island (1953, 258):

I am glad I will be leaving this truly forsaken island before long. One can’t buy anything, few places have electric lights, .... everything is broken down, the people are stupid, the radjas are hopeless.

He found Larantuka with its constant Catholic processions particularly depressing.

Raymond Kennedy, Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Yale University, New Haven

The kampongs of Baipito looked shabby, especially Mudakaputu. The region was terribly poor and overcrowded, covered with stones and with a scarcity of water and food. Many people were hungry and many had sore eyes, swollen bellies and skin sores. Kennedy wrote: ‘Nowhere before have I seen such misery’. The Raja and the tuan tanah used every opportunity to seize the best land for themselves, so many local villagers had lost their land and were forced to work as sharecroppers for the Raja, receiving one quarter of the crop for their efforts. According to the local teacher there had been almost no technological change in the whole Baipito region for the past 50 years - an indication of the indifference of both the Dutch authorities and the Catholic Church. Kennedy was of the opinion that little had changed since Vatter’s visit. A few people now had shovels, and there was just one plough in the whole region. A few men had shirts and shoes, and about 80% of the population were now Catholic.

By this time Lewoloba was accessed by a side road from Wailolong, both kampongs being about the same size and having a close relationship with each other, with much intermarriage. Here the women and girls were still walking 3km to the coast to fetch water.

Lewoloba was now entirely Christian and the korke had been destroyed. There was a weekly barter market at Oka every Tuesday/Wednesday.Wailolong had around 100 houses, and a school with two teachers and a chapel, although the villagers went to the church in Riang Kemie on Sunday. Kennedy estimated the population at around 700. The newer houses were mostly small but some of the older ones were large and could accommodate five families. They were all thatched with alang-alang grass and had bale platforms under the roof and sometimes in front as well. The kakang had a telephone, but there was no telegraph and no post service. Very few people travelled from kampong to kampong and no one had any knowledge beyond Larantuka. Wailolong still had many pagan believers and lots of magical saoniwang stones, but things were changing - there were now very few young people holding pagan beliefs. The korke was located at the head of the village, next to the rectangular nama dance place, but the formerly upright sacred nubanara stones had fallen down and had not been righted. Its roof was damaged and it was empty. Nearby the leader of the main clan had a large house and a korke for his suku (clan).

Wailolong had recently had another skirmish with Waibalun, during which one of their men was killed. Several Lewoloba men were arrested and jailed in Larantuka. The men were still fighting with bows, spears and knives and the priests believed that head-hunting was still taking place in the region in secret. The causes of wars were, in decreasing order: land disputes, women, head-hunting, and someone from one kampong molesting a child from another. Seven of the Baipito kampongs had friendly relations with each other and were linked by intermarriage, but Riang Kemie was generally regarded as an enemy by all of the others. Most of the enmity occurred with the kampongs bordering Riang Kemie, mainly because of land disputes. This long-standing hostility may be because the ancestors of Riang Kemie were later arrivals from Kroko Pukan, whereas all of the other villages were descendants of Lenurat – the ilé jadi.

Wailolong was traditionally allied to Lewoloba but, like the other villages, its traditional enemy was Riang Kemie, against which a small war was fought in the 1930s. It is therefore surprising that its Catholic believers regularly used the church at Riang Kemie. However recently the church and parsonage at Riang Kemie had been destroyed by fire. The korke was not just the centre of the ancestor cult, but also of the war cult.

Kennedy thought that Watowiti and Mudakaputu seemed less interesting than Wailolong, with only one or no korke and less suku.

The health situation had much improved since Vatter’s visit in 1928. In the past roughly half of the children did not survive into adulthood, but by 1950 the situation had improved dramatically thanks to modern medicines and greater cleanliness, the latter greatly encouraged by the priests. However traditional sorcerers called molang (who could be male or female) still used magic to heal some of the sick, while local healers called dukun (who were mostly female) still made and prescribed local quack medicines.

All of the kampongs had about the same level of wealth, although Lewohala and Watowiti had slightly better and more extensive land holdings. Riang Kemie was the largest kampong, with a population of about 1,300 – almost twice that of Lewoloba and Wailolong. Generally all of the korkes were in poor condition, the reason given being the cost of the festivals that must be staged following a repair and the animals that must be sacrificed (Kennedy 1953, 179).

Sadly just three months later, on 27 April, Kennedy was held up and executed by unidentified assailants while travelling in a jeep from Bandung to Yogyakarta in West Java.

Return to Top

The Ilé Mandiri Clan Structure

The people of Ilé Mandiri speak a local dialect of Lamaholot that Keraf classified as Baipito. The separate dialect of Waibalun is spoken in the region closer to Oka Bay.

Each Baipito village is divided into patrilineal clans called suku, a Malay term that means quarter. Children are therefore born into the clan of their father, not their mother. In Ilé Mandiri people sometimes used the term ama, father, instead of suku (Vatter 1932, 74). Apart from sharing the same name and belief in a common ancestry, the members of each clan have a leader, a shared history, possibly a myth of origin, and the same specific prohibitions or wungun, normally a taboo food. They sometimes also have a clan house – a sebuan (known in other regions as a lango bélen)– that contains the clan’s ancestral treasures.

There can be up to a dozen clans in any one village and the composition of each village differs (Vatter 1932, 75). In 1928 Ernst Vatter found that in Lewoloba, which had a population of around 600, the number of people in a clan ranged from just a handful to over one hundred. The clan was the most important social unit. Vatter was surprised to find that clans played a far more important role in Ilé Mandiri society than families. Unlike European societies, in this region men and women were never seen outside the home with each other or with their children. Indeed because the clans were exogamous, the husband and wife in each family belonged to different clans, and so the clans separated husband and wife and wife and children from one another (1932, 74).

Each clan is further subdivided into several named sub-clans or paternal lineages.

The Baipito clans are divided into two types – the suku raja and the suku ama or suku wu’un. The sovereign clans, the aristocratic suku raja (sometimes called the suku raja tuan or suku tuan tana) were founded by the ancestors who initially settled each village (Kohl 1996, 135). As such they have inherited important rights over their village's common land.

Karl-Heinz Kohl studied the village of Belogili facing Hading Bay, which formerly belonged to the Baipito domain and regarded Mudakaputu as its ritual centre. However following a war with Riang Kemie it chose to join the Lewolema domain. There Kohl found that the suku raja were divided into two separate groups (1996, 135):

- the autochthonous suku raja ile jadi who considered themselves the original owners of the villages common land (135). The village’s tuan tana (lord of the earth) was the head of one of these clans.

- the suku raja tena mau were immigrant clans whose ancestors had arrived later by boat (tena) and in the past inherited land rights from the suku raja ile jadi in return for their assistance in fighting wars with neighbouring villages, or in exchange for bridewealth contributed to the ile jadi clans.

The non-sovereign or common clans are called the suku ama (father clans) or suku wu'un (new clans). They have no land rights and have a lower social status than the suku raja.

According to Karl-Heinz Kohl, each village should ideally have four suku raja named Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang, of which Koten is the most important (Kohl 1996, 135). However not all of them actually did, so although that ideal situation applied in a few villages, most had a completely different group of ruling clans. As Rappoport further emphasises, even the ‘four clan’ system is theoretical – some villages have only two or three (Rappoport 2010, 224).

It is important to understand that these four specific suku raja were not original founding clans. Their appellations derive from the traditional system of western Lamaholot leadership, which was most prevalent in eastern Flores. Here many villages were previously governed by the following four ritual elders(Vatter 1932, 81; Arndt 1940, 101–104; Ouwehand 1950, 57–55; and Barnes 2013, 309-310):

- the kepala Koten was the most senior of the four leaders, being in control of internal village affairs including land ownership

- the kepala Kelen was responsible for external affairs, dealing with neighbouring villages and in the past dealing with the Dutch authorities

- the kepala Hurit (also Hurin or Hurint ) and the kepala Marang were advisors and mediators if there was a disagreement between the heads of Koten and Kelen

Each of these positions could only be filled by elders from the founding suku raja clans. Other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders became too powerful. Since independence and the introduction of democratic regional and village government in the early 1960s, their roles have been superseded by an elected kepala desa.

The name of these positions is directly related to their ritual obligations invoved in staging animal sacrifices:

- the kepala Koten holds the head of the animal (koten meaning head),

- the kepala Kelen holds the tail or back legs (kelen is the hind leg of an animal),

- the kepala Hurit severs the animal's neck or head (hurit means knife, derived from surit for sword) and

- the kepala Marang voices the ritual speech during the sacrificial ceremony (marang means to speak or pray).

Together, these land-owning clans are responsible for conducting the annual cycle of agricultural rituals. The right to land is symbolised by the ritual of blood sacrifice called huké tana (giving food to the earth), the land being seen to possess spiritual value that must be fed and reinvigorated by animal sacrifices, preferably a pig or a goat.

In Baipito, the one village that does have the four suku raja clans Koten, Kelen, Hurit and Marang is Lewoloba. Four separate ethnographers have studied its clan structure in some detail: Paul Arndt in the 1930s, Ernst Vatter in 1928, Cornelius Ouwehand in the 1940s and Raymond Kennedy in 1950 (see Graham 1987). They each came up with a somewhat similar structure for suku Lenurat – the ile jadi – although there were slight differences, possibly reflecting the views of their informants. Kennedy’s is the most detailed, showing five clans divided into either two or three sub-clans:

| Clan | Sub-clan |

| Ama Kottang or Koten | Belepe Lolong Waktukang Ama Marang |

| Ama Kelen | Tuakerura Ama Belemang |

| Ama Hurint | Ama Waru’ing Eramolik Ola Demong Making |

| Lewodoreng | Lewamaking Ekimaking |

| Lewonuhah | Ama Kottang Ama Keleng |

Vatter described the Lewoloba clans Koten, Kelen, Hurint and Marang as the suku raja, or royal clans that held a special position as the holders of political power and were responsible for ‘magical-religious’ functions (1932, 81).

However the majority of Baipito villages do not have these four named clans. Their suku raja are quite different, as is the case in neighbouring Wailolong where the clan structure was studied by Kennedy in 1950 and Robert Barnes in 1970. Here there were five sukus, each divided into three lineages (Barnes 1977; Ipankipoy 2016):

| Clan | Lineage |

| Ama Datong | Ama Raja Ama Belolong Ama Reren |

| Lewo Rita | Ama Suba Making Ama Harut Making Ama Tapo Pukang |

| Ama Hurint | Hadum Boleng Ama Waru’ing Mela Making |

| Lewato | Sina Jawa or Ama Waru’ing Bunga Retung or Watukan Keton Making or Tuhowutung |

| Lewo Doren | Pihok Making or Ama Waru’ing Saka Making Eke Making |

Likewise in Lewohala, the four suku raja are Badin, Piran, Lebuan and Weking. The position of kepala Koten is filled by an elder from suku Badin, kepala Kelen by suku Piran, kepala Hurit by suku Lebuan and kepala Maran by suku Weking.

Almost all of the land on Ilé Mandiri, whether cultivated or jungle, was clan property which was generally owned by the suku raja. In addition there were a few stretches of nawa, land that had belonged to individual families from antiquity. It was inalienable land that could never be sold or bought. Each land-owning clan had a tuan tanah, or lord of the land, who was normally the kepala suku. So for example, in Lewoloba there were three: Ama Kotan, Amu Kelen and Lewonuhang (Vatter 1932, 104). The land of each clan was divided into separate lots according to the number of families, and redistributed by the tuan tanah every year - not just to the suku raja, but also to the clans who did not own village land. The latter effectively leased their land, but without paying rent. The tuan tanah also determined which land should be replanted and which should lie fallow, even issuing permission to cultivate new land. Finally he supervised the rituals linked to the annual agricultural cycle.

In the past each village had a temple known as a korke, also the location of the sacred nuba nara stone or stones that symbolised the founding ancestors and defined the ritual centre of the village. An adjacent arena or nama was surrounded by a low wall, often the location for the belada vertical stone slabs, one raised for each clan, which were smeared with sacrificial blood during rituals and festivals. Over the years virtually all of the sacred stones have been destroyed under pressure from the Catholic Church. Some korke had an accompanying meetinghouse called a bale, but in Baipito many korke-bale served as both temple and meeting house. Some villages also had separate clan houses called sebuan, which accommodated the clan elder and the clan’s treasures (Vatter 1932, 93).

The korke was guarded by the tuan korke who was generally the tuan tanah of the clan on whose land the korke had been built (Vatter 1932, 104).

The korke was a raised open-sided building with at least six or more vertical posts and a high roof covered with strips of palm leaf. It is here that traditional ceremonies were conducted, some involving offerings and addresses to the bipartite Divinity, Ama Lera Wulan (Father Sun Moon) and Ina Tana Ekan (Mother Earth Region), others involving a sacrifice to the ancestors in the form of a pig or a goat. In the past, village treasures such as large elephant tusks, drums and gongs were kept in the korke. There may have been a tradition of allowing the korke to deteriorate over time and then replacing it with a new building – a time for great celebration and feasting (Barnes 2009b, 39).

Vatter mentioned that after the erection of a korke temple the villagers would hold dances from sunrise to sundown for four weeks at a stretch in order to safeguard the village from calamities.

Female dancers performing at a festival following the re-roofing of the korke in Wailolong. Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1928

In some settlements the temple was located within the confines of the village, but in others it was outside, further up the volcano at the site of the former village (Arndt 1951, 79). Despite the fact that Lewoloba was never relocated, its korke was situated well away from the village on the flank of the volcano.

Over the years many traditional temples have become derelict. Today, reconstructed village temples can still be found in Wailolong, Riang Kemie and Mudakaputu.

The village korke in Riang Kemie today

The village korke in Wailolong today. Photographed by Viktor B. Hurint, the kepala desa of Wailolong

Most of the Lamaholot today are Roman Catholic, though a minority are Muslim and a few are Protestant. However many people still practise the earlier traditional beliefs, worshipping their bipartite Divinity, Lera Wulan Tana Ekan.

Return to Top

Marriage and Bridewealth

As a generalisation, clans on Ilé Mandiri are exogamous so marriages between members of the same clan are prohibited. However there are exceptions – in some clans it is possible to marry someone from a different lineage within that clan.

Marriage between lineages was governed by strict rules, which Vatter considered to be very complicated and far from uniform (1932, 75). While they certainly were complicated for some villages, they did align with the system of asymmetric alliance. This is conceptually a circular process in which marriages are cycled in one direction through a chain of patrilineal groups. Ouwenhand (1950, 56-57) put forward a grossly simplified model of this process where young women were exchanged as follows:

Koten → Hurit → Kelen → Koten

In the villages of Baipito, the marriage alliances were far more complex. Each lineage had explicit rules that defined a limited number of other lineages (mostly from other clans) that their young women could marry into (the opu or wife-takers) and a limited number of different lineages that their young men could marry into (wife-givers or belaké). The wife-giving belaké lineages are always considered to have a superior status to the wife-taking opu lineages because they provide the gift of life. Lineages cannot exchange women directly – one lineage cannot be both a wife-giver and wife-taker to any one other lineage (Barnes 1977, 142; Graham 1987, 142).

As an illustration Vatter gave a few examples from Lewoloba, which were quite restrictive and severely limited the choice of partner (1932, 75). Thus a man from Ama Waru’ing could only marry a woman from the clans Lewodoreng and Lewonuhang, while a man from the sub-clan Ola Demong Making of Ama Hurint could only marry a woman from the sub-clan Ama Belemang of Ama Kelen. Kennedy examined the marriage rules in Lewoloba in detail. A man in any lineage had the choice of a woman from a maximum of three other lineages (1953, 53).

In the past these marriage rules were strictly enforced, more so than in other Lamaholot regions. Vatter found that breaches of these rules in Lewoloba were once punished by expulsion from the clan or even death. At the time of his visit in 1928, the rules still applied, but the penalties for infringement were less severe. When Kennedy visited Wailolong in 1950 he concluded that there had been no change to the system of marriage for the past half century (Kennedy 1955, 193).

The ideal norm was matrilineal cross-cousin marriage – a young man should marry his mother’s brother’s daughter. Indeed the couple were considered engaged from birth. By 1950 this had become considerably weakened, partly due to pressure from the Catholic Church. The preference was for a boy to marry into the clan or lineage of his mother, although this was no longer obligatory (Kennedy 1955, 194-199). Marriage into any wife-giving lineage was acceptable, but marriage into any other lineage or group required a higher bride-price.

A Catholic wedding in a mountain village near Ilé Mandiri, dated about 1915

Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam. Probably photographed by Charles Le Roux

Marriage always demands a special gift exchange between the lineages forming the alliance: thus bridewealth composed of one or more elephant tusks (bala) is given to the woman’s lineage, while in return a counter-prestation composed of ceremonial cloths is given to the man’s lineage.

Ernst Vatter found that an elephant’s tusk was the most precious and enviable item that a person from Ilé Mandiri could own. The number and size of tusks in their home defined their wealth, social position and reputation (1932, 76). At that time tusks were classified into eleven separate sizes, ranging from the short bala kerüng (with a length from the fingertip to the elbow) up to the bala raing, over a fathom long (1.8 to 2.0 metres). Raing or rai appears to mean ‘more’.

The kepala desa of Lewoneda proudly displaying his village treasures: large tusks said to be worth 1,000 guilders each (equivalent to about $10,000 today). Vatter 1928.

The values of the gift exchange depend primarily on the social status of the two families involved; for a chief's daughter it will be larger than that for the daughter of a simple man. Vatter gave the example of a porter who had not yet married because he had no tusks (1932, 77). To marry he would need one huge bala huut tusk around 1.8 to 2.0 metres long, worth at that time at least 300-400 guilders, or several smaller ones, along with two or three goats and pigs. The counter-prestation would consist of several beautiful women's sarongs, with a value of around one third of the bridewealth.

By the time of Kennedy’s visit, the number of elephant tusks in circulation was much reduced. Clan leaders made every attempt to ensure that tusks remained within the village and were not exported elsewhere. In 1950 Wailolong and Lewoloba had about 25 tusks each, which were considered just enough to maintain the marriage system (Kennedy 1953, 184). There a man’s clan needed a minimum of 5 tusks to underwrite a marriage, but in Riang Kemie they only needed three. For poorer men, the clans were using virtual tusks, never transferring the real tusks from one family to another or in Kennedy’s words ‘making the transfer in their heads’ (1953, 47). As the circular system of marriage alliance progressed it was assumed that the old debts would be gradually cleared. However in the long term the bridewealth had to eventually be paid, even if it took two generations to do so (Barnes 1977, 149).

By the 1970s in Lewoloba, Barnes was told that bridewealth was now the same value for all marriages, irrespective of the class or wealth of the parties (1977, 150). Today tusks still exist, but have become increasingly rare and are often replaced by cash. Nevertheless the link between the marriage exchange value of a tusk and a bridewealth sarong still applies. Thus in Lewohala:

- a kewatek kenuma can be exchanged for a legar tusk with a length extending from the fingertip to the armpit,

- a kewatek mowak can be exchanged for a bedori tusk, with a length extending from the fingertip to the opposite shoulder, while

- a kewatek méa can be exchanged for a balarai tusk with a length extending from one fingertip to the other fingertip.

To be exchanged for an elephant’s tusk the kewatek must have a complete rewot.

Bibliography

Aritonang, Jan S., and Steenbrink, Karel, 2008. A History of Christianity in Indonesia, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2009. Flores Timur Dalam Angka 2009, Larantuka

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Flores Timur, 2018. Kecamatan Ile Mandiri Dalam Angka 2017, Larantuka.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1977. Alliance and Categories in Wailolong, East Flores, Sociologus, vol. 27, pp. 133-157, Duncker and Humblot, Berlin.

Barnes, R. H., 1985. The Leiden Version of the Comparative Method in Southeast Asia, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, vol. 16, pp. 100-101, Oxford.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1987. Avarice and iniquity at the Solor Fort, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 143, no: 2/3, pp. 208-236, Leiden.

Barnes, R. H., 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 2008a. The Power of Strangers in Flores and Timor, Anthropos, vol. 103, pp. 343-353.

Barnes, R. H., 2008b. Raja Lorenzo II: A Catholic kingdom in the Dutch East Indies, IIAS Newsletter, vol. 47, pp. 24-25.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 2009a. The grooming of a Raja: Don Lorenzo Diaz Vieira Godinho of Larantuka, Flores, Indonesia, Indonesia and the Malay World, 37, 107, pp. 83-101.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 2009b. A temple, a mission, and a war: Jesuit missionaries and local culture in East Flores in the nineteenth century, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 165, no. 1, pp. 32-61.

Barnes, Robert, H., 2010. Raja Servus of Larantuka, Flores, Eastern Indonesia, Recherche en sciences humaines sur l'Asie du Sud-Est, vol. 16, pp. 39-56.

Berke, Donald A.; Kindell, Don, and Smith, Gordon, 2014. World War II Sea War, vol. 6, The Allies Halt the Axis Advance, Bertke Publications, Dayton.

Dietrich, Stefan, 1983. Larantuka and the Baipito District, Flores in the Nineteenth Century: Aspects of Dutch Colonialism on a Non-Profitable Island, pp. 48-51, Indonesia Circle, School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

Dietrich, Stefan, 1995. Tjeritera Patigolo Arkian: Struktur und Variation in der Gründungsmythe des Fürstenhauses von Larantuka (Ostindonesien), Tribus, vol. 44, pp. 112–148.

Dietrich, Stephan, 1998. "We Don't Sell Our Daughters": A Report on Money and Marriage Exchange in the Township of Larantuka (Flores, E. Indonesia), Kinship, Networks and Exchange, pp. 234–250, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Fox, James J., 1980. The Flow of Life: Essays on Eastern Indonesia, Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Graham, Penelope, 1987. East Flores Revisited: a Note on Asymmetric Alliance in Leloba and Wailolong, Indonesia, Sociologus, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 40-59.

Hägerdal, Hans, 2012. Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea, KITLV Press, Leiden

Kennedy, Raymond, 1955. Field Notes on Indonesia: Flores, 1949-1950, Human Relations Area Files, Behaviour Science Monographs, New Haven.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. Morfologi Dialek Lamalera, Doctoral Thesis, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/languages/lama1277-baipi

Kohl, Karl-Heinz, 1996, A Union of Opposites: The Cosmological Meaning of Sacrifice in East Flores, For the Sake of our Future: Sacrificing in Eastern Indonesia, Howell S. ed., pp. 133-147, Research School CNWS, Leiden.

Pires, Tomé, 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, translated by Armando Cortesào, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Rodrigues, Francisco, 1944. The Book of Francisco Rodrigues, translated by Armando Cortesào, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Saldanha, Joao Mariano de Sousa, 1994. The Political Economy of East Timor, Pustaka Sinar Harapan, Jakarta.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002a. Catholics in Indonesia, 1808-1900, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Steenbrink, Karel, 2002b. Another Race Between Islam and Christianity: The case of Flores, Southeast Indonesia, 1900-1920, Studia Islamika, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 63-106, Jakarta.

Steenbrink, Karel A., 2003. Catholics in Indonesia 1808-1942: A Documented History, vol. 1: Modest Recovery 1808-1903, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Waterson, Roxana, 2006. Houses and the Built Environment in Island South-East Asia, Inside Austronesian Houses Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living, pp. 227-242, ANU Press, Canberra.

Weking, Christina T., 2018. Derivasi Bahasa Lamaholot Dialek Baipito, Metalingua, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 135-151.

Wouden, F. A. W. van, 1968. Types of Social Structure in Eastern Indonesia, translated by Rodney Needham, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Publication

This webpage was published on 15 February 2021.