Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Geography

Klon Oral Histories

An Extremely Limited History of the Klon

Klon Ethnography

Klon Linguisics

Klon Lego-Lego

The Ernst and Hanna Vatter Expedition

Klon Textiles

Klon Paneia Women’s Costume

Klon Paneia Men’s Costume

Bibliography

Introduction

The little known Klon, also known as the Kelong, Kalong, Kelon or Kolon, are one of fourteen non-Austronesian ethno-linguistic groups inhabiting the island of Alor in eastern Indonesia. The Klon were originally confined to the western part of Kerajaan Kui but some now reside in Moru, Kalabahi and beyond. They speak a language belonging to the Trans-New Guinea family of Papuan languages (Brown, Asher and Simpson 2006, 281). Subjugated by the Rajadom of Kui in the late nineteenth century, they adopted Protestant Christianity in the first few decades of the twentieth century. Only the coastal Klon have a tradition of weaving.

Geography

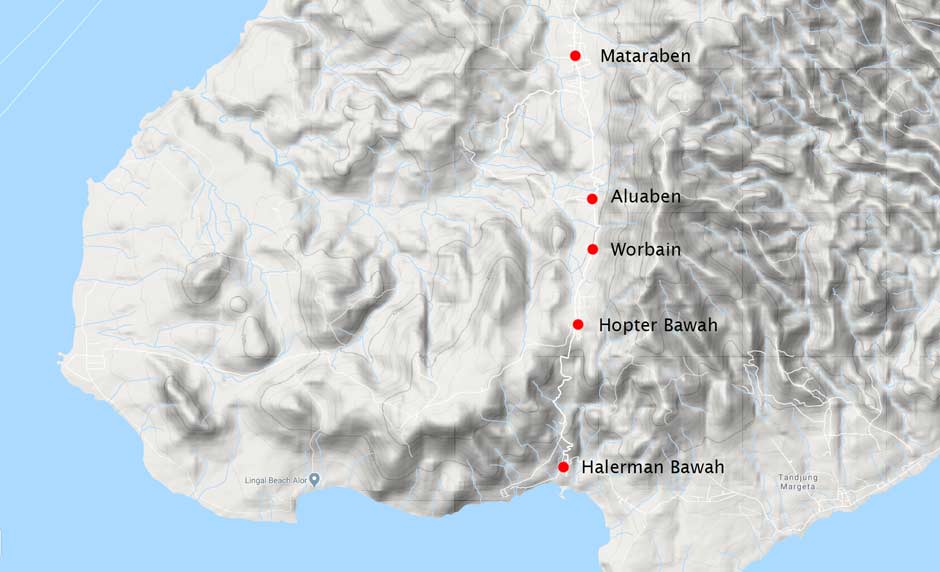

Administratively the Klon region falls within the confines of Kecamatan Alor Barat Daya (Southwest Alor Sub-District), one of the seventeen kecamatan (sub-districts) of Alor Regency. Alor Barat Daya has one kelurahan (urban village) – Moru, the administrative centre of the kecamatan – and nineteen desa (rural village districts), many composed of two or more dusun (hamlets). The Klon are mainly found in the desas of Probur, Probur Utara, Halerman, Margeta, Manatang and Tribur (Katubi 2005, 56).

However the majority of Klon are concentrated in a limited number of dusuns located in the remote far southwest:

- the coastal hamlets of Halerman, Margeta and Manatang and

- the inland hamlets that lie along a track that runs north from Margeta Bay to Mataraben in Desa Probur, including Hopter, Worbain and Aluaben.

Map of South Western Alor Island and the Pantar Strait.

Klon villages are highlighted in red.

The view from Cape Margeta towards Treweng Island and southern Pantar.

Mataraben is reached on a poor quality road that runs from Moru in the north via the relatively new hamlet of Habolat in Desa Probur Utara, occupied by the ethnic Kafoa and Beilel along with a few Klon (Sudiyono 2015, 188).

Above and below: The key link from Margeta Bay and Lower Halerman heading north to Martaben. Images courtesy of Google Maps.

The road from Mataraben south to Halerman follows the bottom of a rugged mountain valley flanked by a steep escarpment on the eastern side with peaks rising to 1000m. The condition of this important link has been very poor, with some sections severely potholed. In 2017 plans were announced to rebuild this road starting with the stretch from Hopter to Manatang (Kaful 2017, Kab. Alor). This is intended to take place in parallel with an extension of the electricity network southwards from Moru. Work has already started on the Halerman-Hopter road and bridge construction project, but there are accusations that some of the funding on earlier road improvements has been misappropriated (Beraona 2015, Media NTT).

The broken road running south towards Hopter.

Halerman is also connected to Kalabahi by a fortnightly ferry service operated by the motorboat MV Laut.

The seas around southwest Alor are exposed to the open Savu Sea and the Indian Ocean and can be hazardous in bad weather. There have been many shipwrecks around the coast of Cape Margeta. There are also several long deserted sandy beaches, especially Halmin and Ling'al.

The remote southwest. Looking south across Margeta Bay towards Cape Margeta.

Halmin Beach in the far west of Alor Barat Daya facing Treweng Island and southern Pantar.

In 2017 the population of Alor Barat Daya was 23,000, 11.3% of the Alor Regency total (Badan Pusat Statisik 2018). The Klon population has been roughly estimated at between 5,000 and 6,000 (Baird 2005, 1; Baird 2008, 3). A later 2009 survey by SIL International identified 6,000 Klon speakers on Alor (Shiohara 2010,177). The Klon are the second largest ethnic group in Alor Barat Daya, after the Abui.

Today within the former domain of Kerajaan Kui, the Abui and the Klon make up the majority of the Christian community and together account for 85-90% of the population. The ruling Masin, who are mainly Muslim, make up only 10-15% of the population (Kinanggi 2018). Despite this there is complete religious harmony.

Hopter Covered Bazaar.

The majority of Klon are farmers, growing maize, field rice and beans as well as taro and sweet potatoes (betatas). The main local market is at Hopter. There is very little fishing. In Desa Halerman, which encompasses nine kampungs including the two coastal kampungs of Halerman Bawah and Ling'al as well as inland Hopter, in 2018 there were only 10 fisherman compared to 520 farmers and 140 livestock breeders (Laporan Survey, Universitas Tribuana Kalabahi).

Return to Top

Klon Oral Histories

According to several different oral narratives it appears that the Klon may be an amalgam of groups with separate origins – having antecedents from either the mouth of Kalabahi Bay or southern Mataru in western Alor, or from northern Pantar or from northern Timor.

One group trace their origin to Cape Matap on Alor, on the south side of the entrance to Kalabahi Bay facing the Pantar Strait. In a Klon myth of origin documented by a Protestant preacher in 1950 and recounted by Emilie Wellfelt (2016, 263-264), the first two humans were created by God at Matapu, where they lived in a cave and were helped by the youngest daughter of the ruler of the sea. After the daughter married one of the Klon ancestors they had children and grandchildren. In time the latter relocated to the hamlet of Mabur, located just north of Buraga in Desa Tribur. According to the myth, they met Maleikili and Karkili, the founders of Kerajaan Kui, when they first landed on Alor.

A second narrative concerns two Klon ancestors from the village of Mudbur, the location of which is unknown (Wellfelt 2016, 264-265). Both being wealthy and able warriors, they were visited by their Hamap neighbours from Fo’ang, which may be a hamlet just west of Moru. The Hamap needed help to hold an important festival and the Klon warriors provided them with rice, cattle and a special moko drum. Later the Klon walked to Fo’ang to recover their debt, where they were impressed by the Hamap’s great house or temple decorated with woodcarvings. The Hamap repaid their debt with a similar moko drum and a piece of house carving. Back in Mudbur, the ancestors built their own house decorated with carvings based on the Hamap designs. During the lifetime of their son, the house was moved to Mabur, where it became a temple dedicated to the ancestors.

A third intricate narrative, collected by but only briefly sketched out by Wellfelt (2016, 262), suggests that the inland Bring Klon originated from an ancestor named Makini, an Abui from the village of Makaleleang in Mataru, located north of the south coast village of Eibiki. The village was attacked by a naga dragon-snake, forcing the residents to flee in different directions. One ancestor travelled west and settled in the hamlet of Probur, now Mataraben, where his descendants founded the house of Makanwat in memory of their origins in Mataru.

In the past the veneration of snakes and crocodiles was widespread across Alor. Carved ular naga (dragon snakes) statues were the guardian spirit of the village and were placed in ritual houses near the ceremonial dance floor in the centre of the village. The naga received ritual sacrifices to protect the clan against disease, misfortune and evil spirits and to ensure fertility, health and successful hunting and fighting. When such statues were removed it was believed that the snakes would come to steal the villagers' children. It was believed that an angry naga could initiate earthquakes (Jacobsen 1896, 51).

A carved ular naga serpent-dragon collected on Alor prior to 1880

(Image courtesy of Royal Zoological Society Natura Artis Magistra, Amsterdam)

In 2004 Thomas Loban, the resident of a mountain hamlet in Desa Probur who was the brother of Vincentius Loban (the 65-year-old chief of the Klon living in Moru), recounted yet another narrative (Katubi 2005, 57-58). This suggests that the ancestors of some of the Bring Klon came from Pantar Island on the opposite side of the Pantar Strait. According to the legend, the Kingdom of Munaseli located on Tanjung Muna, the northernmost cape of Pantar, was attacked by sea pirates and the residents fled to Alor. Linguists deduce that Munaseli and Pandai were settled by Lamaholot immigrants from Lembata Island, possibly Kédang, during or before the 14th century (Klamer 2012, 102). Legends from Pantar suggest that a conflict erupted between these two enclaves in the early fifteenth century, with Pandai attacking Munaseli, possibly with the assistance of Javanese marauders. The residents of Munaseli fled, some settling on the west coast of Alor, others continuing eastwards to Kolana and some going west to Lembata (Rodemeier 2006, 69; Barnes 2001, 279).

According to the story, these Klon Bring ancestors first settled at Klon Buku, the location of which we cannot ascertain, and later ascended Mount Muna, which is just over 9km north of Lerabaing and, at 1440m, the second highest peak on Alor. One wonders if it was named after Munaseli or Tanjung Muna? From Mount Muna they migrated south to Menif in the region of Mataru close to the south coast, then turned westwards to Kemai Fui followed by Wakapsir and finally Buraga. From there they ascended Mount Ulman Waiman, presumably the name of one of the peaks on the range of mountains that flanks the eastern side of the valley occupied by the majority of Klon today. On the mountain, one of the chiefs had three children, only two of whom survived. One eventually moved to Buraga on the southern coast, while the other moved to the current region of the Klon. This separation might partially explain the division between the coastal Klon and the inland mountain Klon.

Just to add one further dimension, the missionary A. A. van Dalen who worked on Alor from 1922 until 1924 reported that the people residing west of Kui – in other words the Klon - originated from the village of Wiwoko, located on the direct opposite side of the Savu Sea, north of Atapupu in West Timor (1928b, 263). It is interesting that most of the ethnic groups along the southern and eastern coasts of Alor - the Kui, Batulolong, Pureman and Kolana – appear to have cultural links to Timor. An anonymous 1914 report, written following the Dutch ‘pacification’ of Alor Island in 1910 noted that the coastal population of Kui was partly from Timor (Anonymous 1914, 77). From Kui, the Timorese immigrants gradually spread eastward and settled successively in Pureman and Kolana. This supports van Dalen’s comments and suggests that the coastal Klon subsequently assimilated immigrants from the north coast of Timor.

Interestingly in 1929 when Ernst Vatter asked some of the Klon-speaking residents of Kui about their origins he was told that some of their population migrated from Ende on Flores (1932, 242). We suspect that this comment referred to members of the minority Masin ethnic group, the rulers of Kerajaan Kui of which Klon was then a part.

Return to Top

An Extremely Limited History of the Klon

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was conflict between the Rajadom of Kui and the neighbouring regions of Klon (Kelong) and Mataru, with Kui eventually subordinating them both (Gomang 1993, 3). However this subjugation of the Klon does not appear to have succeeded until the very late 1800s. When the Dutch commissioner, Emanuel Francis, visited Kupang in 1831/32 he recorded a list of the local domains recognised at that time. The list for Alor, which he may have visited in 1831, included three separate domains in the southwest: Kui, Kelong (Klon) and Hamapu (Hamap) (Hägerdal 2010b, 236-237).

Francis had abolished the position of posthouder on Alor in 1831. However after the initial 1851 agreement between the Portuguese and Dutch to transfer control of the eastern islands including Alor to the Dutch, the posthouder Johan Hendrik van Nimwegen was installed at Alor Kecil at the mouth of Kalabahi Bay in 1852 (Almanak van Nederlandsch-Indië 1852). The formal treaty of demarcation was not finalised until 1854 and was only ratified in 1859 as the Treaty of Lisbon.

During the 1850s the Dutch divided Alor into four self-governing regions or zelfbesturende landschappen, later divided into six – Alor Besar, Kui, Bataru, Pureman, Batulolong and Kolana (van Galen 2010, 20). The chief of each landschappen became a Raja and, in return for his loyalty to Holland, was given powers over his domain - powers which he lacked the ability to impose. Chief Pui Soma or Pasoma became the first official Raja of Kui, supported by a single Kapitan, both based at Lerabaing. In theory his powers extended over the western region inhabited by the Klon.

Raja Pasoma of Kui died in 1890 or 1891 and was succeeded by his nephew’s eldest son, Taru Soma I (in some sources Tarsoma), who ruled until 1897. Under Raja Taru Soma I, the Klon region of Probur was officially incorporated into landschap Kui, having previously been contested by the Rajas of Alor (Van Galen 1946, 35). It became a new kapitan-ship of the Rajadom of Kui. Kapitans were local resident administrators who reported to the Raja. Kapitan is a word of Portuguese origin derived from capitão (Ellen 1986, 52; Hägerdal 2010, 21).

In 1906 the Resident of Timor, J. F. A. de Rooy, promoted posthouder A. C. Meulemans to the newly created position of Controleur of Alor, still based at Alor Kecil. The position of posthouder was given to A. F. Morgenstern (Regeeringsalmanak voor Nederlandsch-Indie 1907). It did not take Morgenstern long to realise that although the Dutch-appointed coastal Rajas took it upon themselves to exert their authority over their respective hinterlands, the animist mountain people did not accept them as their leaders (Morgenstern 1909 cited by van Galen 1946, 2). The Rajas spoke a different language, had a different religion, did not understand their adat and in some cases had not even visited the regions concerned. It is highly likely the same situation applied to the Klon within Kerajaan Kui.

The first Protestant missionary from the Dutch Indische Kerk arrived on Alor in 1901 (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 305). With the support of Controleur Meulemans, the church grew rapidly as villagers were encouraged to abandon their sacred nagas and adopt the new faith. By the early 1930s Reverend Krüger claimed that, with the exception of the Muslims, the whole population of Alor had accepted Christianity.

Dutch attitudes to the eastern islands were changing fast, with the replacement of the former policy of self-rule with a more hands on approach. Alor Island was one of the last to be affected. In July 1910, Lieutenant Adelberg was sent from Kupang to Kalabahi with three detachments of marechaussee. It seems the mountain dwellers on Alor respected the well-armed troops and were generally cooperative (van Galen 2010, 22).

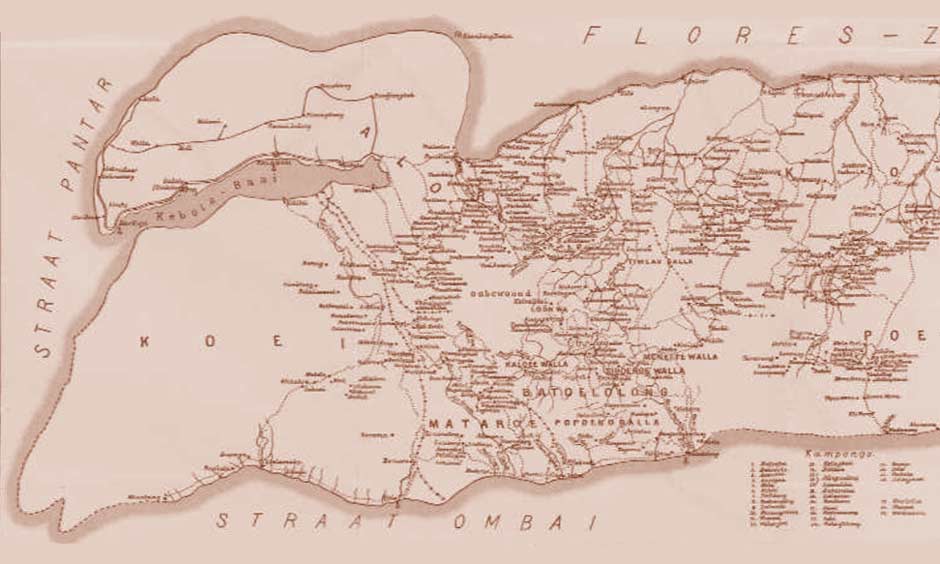

A map produced by Adelberg’s surveyor shows that there was only a limited military incursion into the western part of Kerajaan Kui and none at all into the areas inhabited by the Klon:

Part of the map of Alor included in Anonymous 1914

Lieutenant Adelberg’s campaign resulted in an anonymously authored report describing the state of affairs on Alor Island at that time, although many of the comments within it were in a generalised form. In that report it is noted that, according to Controleur Meulemans, the population of Kui was divided between two tribes: the Barawahieng (a term applied to the Abui) and the Kelong (Klon) (Anonymous 1914, 76). It is clear that he can only have been referring to the mountain villages of Kui. Meulemans thought that the mountain populations of Mataru and Batulolong probably also belonged to the Barawahieng or Abui tribe because they spoke roughly the same language.

Under their new hands-on policy, the Dutch placed increased demands on the local Rajas – they needed to maintain the newly introduced system of registration and taxation, construct new roads and build schools. On Alor Island only two leaders – Raja Gaw Amalei of Kerajaan Kui and the newly installed Raja Nampira Bukang of Kerajaan Alor – were considered up to the job (du Croo 1964, 462).

Dutch taxation, re-registration and forced labour, enforced by the regional Rajas on behalf of the Dutch, led to increasing resentment, especially among the inland mountain villages. In 1914 there was an uprising against the Dutch and the Raja of Kui in the district of Probur, as well as against the Raja of Alor in Alor Besar and Atimelang. The Dutch organised military patrols in the Kalong (Klon) region in the kapitan-ship of Probur (Van Galen 1946, 22).

The Rapat Zaal or adat courthouse in Kalabahi in 1926

From the photograhic album of C. van Schultz, Resident of Timor

According to the Dutch controleur of Alor, G. A. M. van Galen the landschap (colonial region) of Kui in 1946 consisted of three kapitan-ships, one of which was the Klon region of Probur, led by Kapitan Thomas Loban, son of the kepala besar of the kampong Mataraban in the region of Probur.

In van Galen’s opinion, the populations in much of Alor, especially in the landschap of Kui as well as the communities of Welai on the neck of the Kabola Peninsula and Limbur to its east, were still ‘utterly primitive’. At that time the roads on Alor were just horse tracks. Although there was a wide track from Alor Kecil to Kalabahi and on to Moru, its bridges were unsuitable for cars (Van Galen 1946, 75).

After independence in 1949, the previous Dutch system of regional governance continued for more than a decade with Klon, headed by the Raja of Kui, Banla Kinanggi, remaining part of the landschap or swapraja of Kui. This was one of eight landschappen within Onderafdeeling Alor. It was not until 1 July 1962 that the government of NTT abolished the system of swaprajas in favour of sub-districts or Kecamatan. The Governor of NTT stripped the Raja of Kui of his political power and appointed Bapak Pelupesi as acting Camat of Kecamatan Alor Barat Daya, located in its new administrative centre of Moru (Kinanggi 2020).

Since then there has been only limited economic development in the sub-district, with most of it concentrated in the urban region of Moru. Little has filtered out to the rural Klon. It is only in the past few years that attention has turned to improving the southern road link, extending the electricity network and installing Indosat communication towers above Halerman Atas and on Cape Margeta.

Return to Top

Klon Ethnography

The Klon still mainly live in the western part of the former Kerajaan of Kui.

According to Thomas Loban, the Klon used to live entirely within Kerajaan Kui (Katubi 2005, 57 and 58). In 2004 he explained that the Klon were composed of three tribes: the Bring, Paneya (Paneia) and Aboa, the latter speaking the Aboa language, often referred to as Kafoa. These three tribes are derived from three tribal sequences, namely Om'elor (eldest tribe), Kpit'elor (Middle tribe), and Ik'elor (youngest tribe).

However linguists treat the Kafoa as a separate ethno-linguistic group (Baird 2017). In the past their twelve clans had been dispersed throughout Kerajaan Kui, but since 1961 they have come together in the hamlets of Habolat and Lola in Desa Probur Utara located to the north of the main Klon-speaking region.

We therefore believe that the true Klon are divided into just two clans – the inland Bring and the coastal Paniea. Of these two clans only the Paneia could weave.

In the past, kinship among the Klon was based on paternal clans called läl that were led by a clan leader called a likewä and were exogamous (Vatter 1932, 245). Apart from being obliged to marry a partner from another clan there were no further restrictions on marriage. Bridewealth (am) for the bride’s lineage was composed of moko drums (known locally as hahal), gongs (gon), shawls, goats and pigs, one third to one half of which formed the dowry and became the personal property of the bride. There seems to have been no counter-prestation. In the event of a death, offerings of moko drums, gongs, swords, loincloths, sarongs, beaded sashes and other jewellery, goats, pigs, baskets of rice, maize and other vegetables were brought to the funeral.

Return to Top

Klon Linguistics

The Klon speak a language belonging to the Trans-New Guinea family of Papuan languages (Brown, Asher and Simpson 2006, 281). It is closely related to Hamap and Kabola (Adhiti et al 2016, 21).

There are two Klon dialects:

- Bring, spoken by around 3,000 people in hamlets in the northern villages of Desa Probur, Probur Utara and Tribur (such as Mararaben, Bakan, Durel, Aluaben, Longkap and Worbain) and

- Paneia, spoken by some 2,000 to 3,000 people in hamlets in the southern coastal villages of Halerman, Margeta and Manatang in Desa Tribur (Baird 2008, 3).

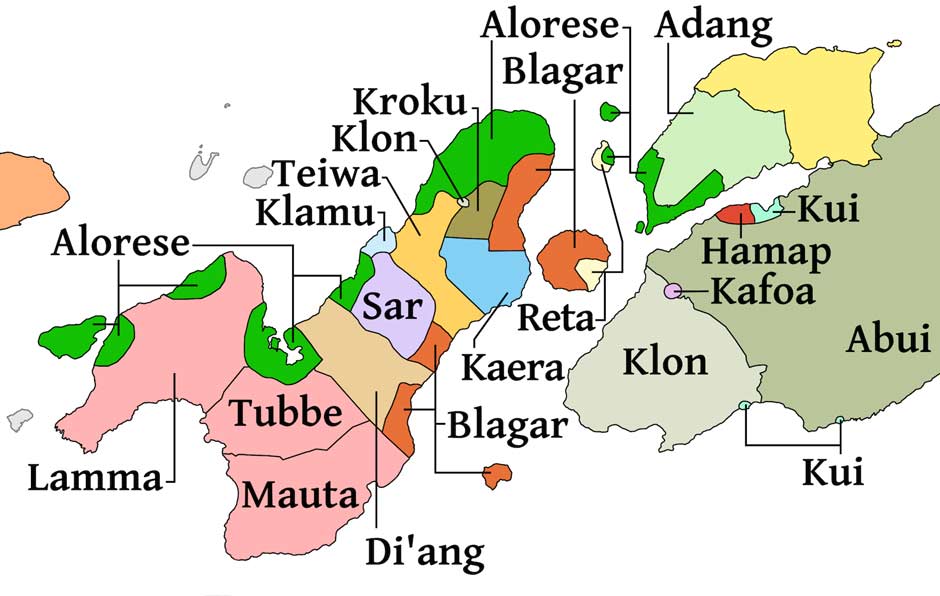

The language map below is somewhat misleading since it implies the Klon are widely dispersed, whereas they are mainly confined to a string of hamlets located on a road running north-south from Lola to Margeta Bay.

Linguistic map of Pantar Island and Western Alor

(Reproduced courtesy of the cartographer and copyright holder Owen Edwards 2018)

Only the Paneia have a tradition of weaving (Kinanngi 2018). From the textile point of view, Louise Baird regrettably conducted her linguistic research in the non-weaving Bring-speaking hamlet of Mataraben (formerly Probur) in modern Desa Probur.

Louise Baird found that Klon Bring is still widely spoken in most aspects of daily life while Alor Malay is used in church or with outsiders (Baird 2008, 7). Unfortunately many Klon Bring today see their indigenous language as old-fashioned and associated with poor uneducated people (Baird 2008, 10). Some Klon speakers are multi-lingual and in addition to Alor Malay can speak other Alor languages such as Abui and Hamap (Baird 2008, 7).

Linguists have argued that the Alor-Pantar languages originated on Pantar Island, which today has the region’s highest linguistic diversity (Holton and Robinson 2017, 75). The languages of Alor Island originated in the Pantar Strait and subsequently migrated eastwards.

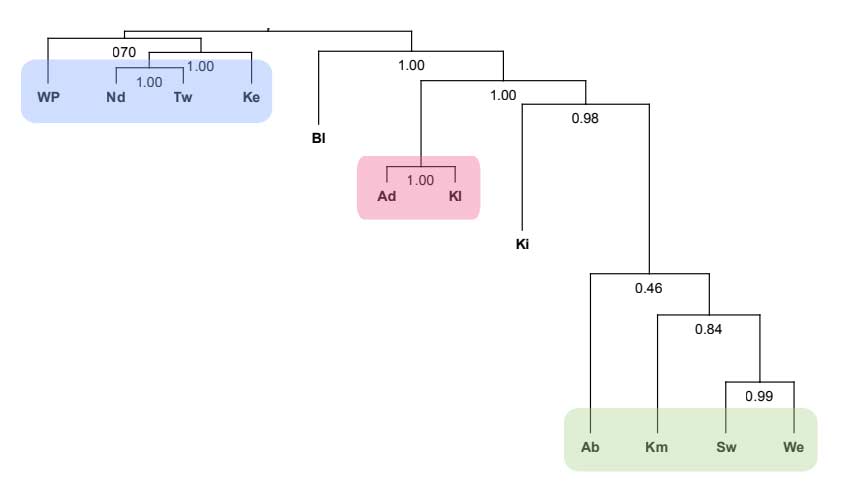

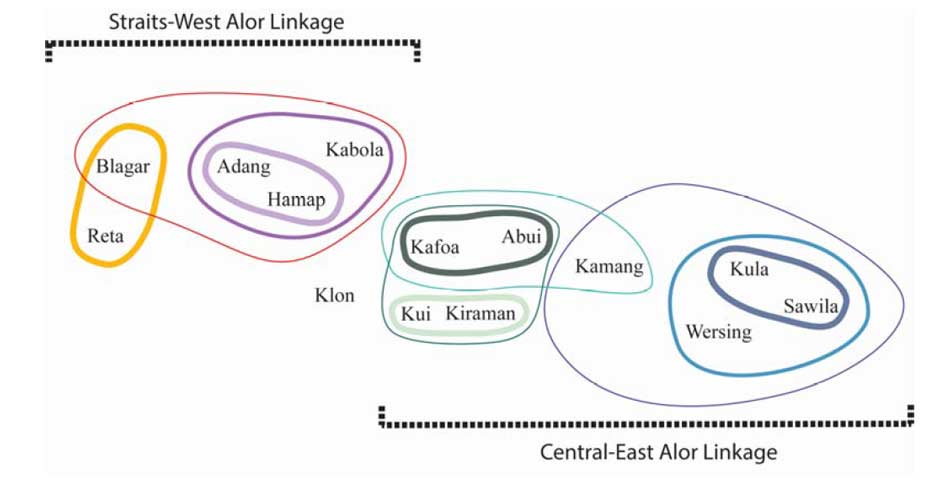

By analysing various language features it is possible to subgroup the Alor-Pantar languages to highlight which ones are more or less closely related (Holton and Robinson 2017, 70-73). An analysis of cognates (words that have evolved from a common ancestor) classifies Klon within a Central Alor group that also includes Kui and Adang. However a different analysis based on shared ‘phonological innovations’, places Klon within a small West Alor subgroup, which also includes Adang (spoken in western Kabola) and Blagar (spoken in the Pantar Strait), although Klon differs somewhat from the other two more closely related languages that form a Straits sub-subgroup. The adjacent Central Alor group is composed of Kui, Abui and Kamang. In a separate Bayesian analysis based on lexical characters (i.e. words), Klon and Adang form a different small subgroup distinct from Blagar and Kui.

Cladistic sub-grouping of the Alor-Pantar languages based on lexical characters showing Klon (Kl) grouped with Adang (Ad). From Holton and Robinson 2017.

Another recent analysis of lexical innovations in the Alor-Pantar languages places Klon within a broad Straits-West Alor grouping, but also concluded that Klon does not subgroup with any of the other Alor languages in either the Straits-West Alor or the Central-East Alor groupings (Schapper & Wellfelt 2018, 95). Klon sits alone in its own first-order subgroup.

The above comparisons suggest that Klon contains elements linked to the peoples of the Pantar Strait and Kalabahi Bay as well as to the southern coastal region of Kui, reflecting the Klon’s mixed ethnic composition. However its geographical isolation has allowed it to evolve unique features that distinguish it from the neighbouring linguistic groups.

Return to Top

Klon Lego-Lego

The Controleur of Alor, M. A. Bouman, discovered that in the regions of the Abui (which he described using the derogatory sub-group term Barawahing) and the Klon, the kampongs were occupied by just one clan and at its centre (the melang, abing or aving) each had a dance place (masang) for that clan, which was sometimes associated with an adjacent clan house (kadang) (1943, 486). These were surrounded by the houses standing on terraces constructed from rocks. The clan houses were distinguished by horn-shaped decorations (tangabeka) sprouting from the top of the roof.

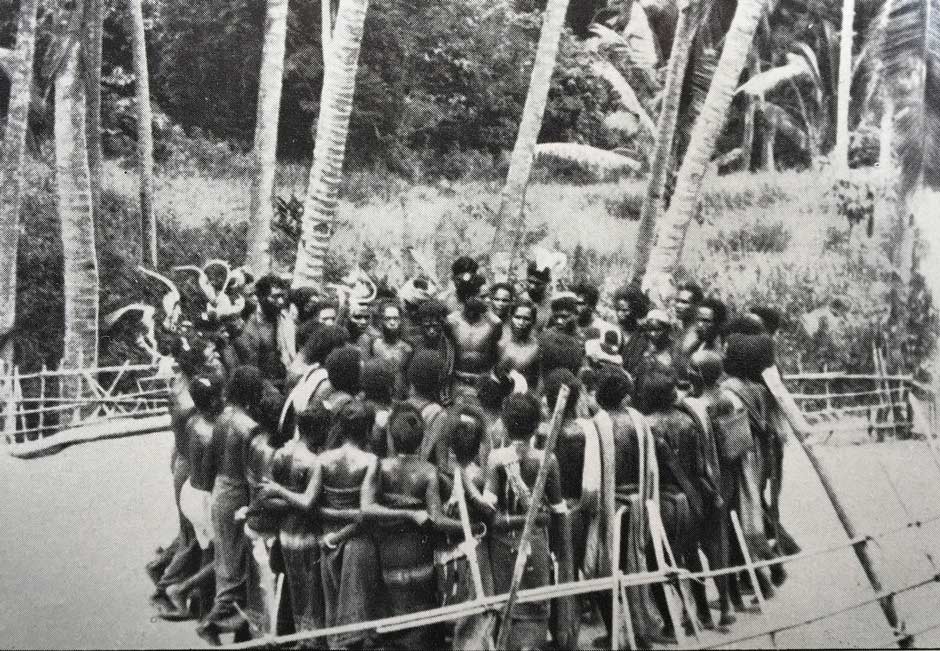

The lego-lego dance performed in Halerman in 1929. Photographed by Ernst Vatter.

The circular dance place, roughly 5 to 10m in diameter, was arranged around a high circular stone stack, roughly 2 to 3m in diameter and about 1m high, with an upright stone placed at its centre – very similar to the structures we see in Abui villages today. Sometimes a shelter or vokongvala, where the brass gongs were hung, was located close by . In the very old kampongs, community graves (majang) for the main members of the clan house were positioned at the edge of the dance place.

Return to Top

The Ernst and Hanna Vatter Expedition

We are fortunate to have been left an insight into the textiles of the Klon as they were almost a century ago thanks to a visit to the region by the German ethnographer Ernst Vatter and his newly wedded second wife Hanna in 1929.

The Vatters disembarked at Larantuka harbour on the island of Flores on 9 November 1928 from an old Dutch steamship, the KPM De Clerq, which had departed from Surabaya nine days previously. They had been sent to eastern Indonesia on a seven-month-long collecting expedition on behalf of the Museum of Ethnography in Frankfurt. After extensively exploring the Lamaholot regions of East Flores, Solor, Adonara and Lembata, they sailed from Larantuka to Kalabahi at the beginning of April 1929 on the steamer KPM Both.

Once on Alor they began their collecting campaign on the Kabola Peninsula but later that month they left Kalabahi in the government motorboat to be dropped in Margeta Bay (in his words Pantai Mar’ia) on the south coast of far western Alor to explore the Klon-speaking region of Kerajaan Kui.

They were met on the beach by First Lieutenant H. Sjoers of the Dutch infantry, whose soldiers were conducting an inspection tour of the Klon villages (1932, 241). The Vatters were escorted 7km north on horseback to an army bivouac located in a deep mountain gorge at Probur (now known as kampung Mataraben), passing through the hamlets of Bakan and Duläl (now Durel), whose inhabitants originally came from Probur. Apparently Bakan and Durel offered very little of interest to the Vatters.

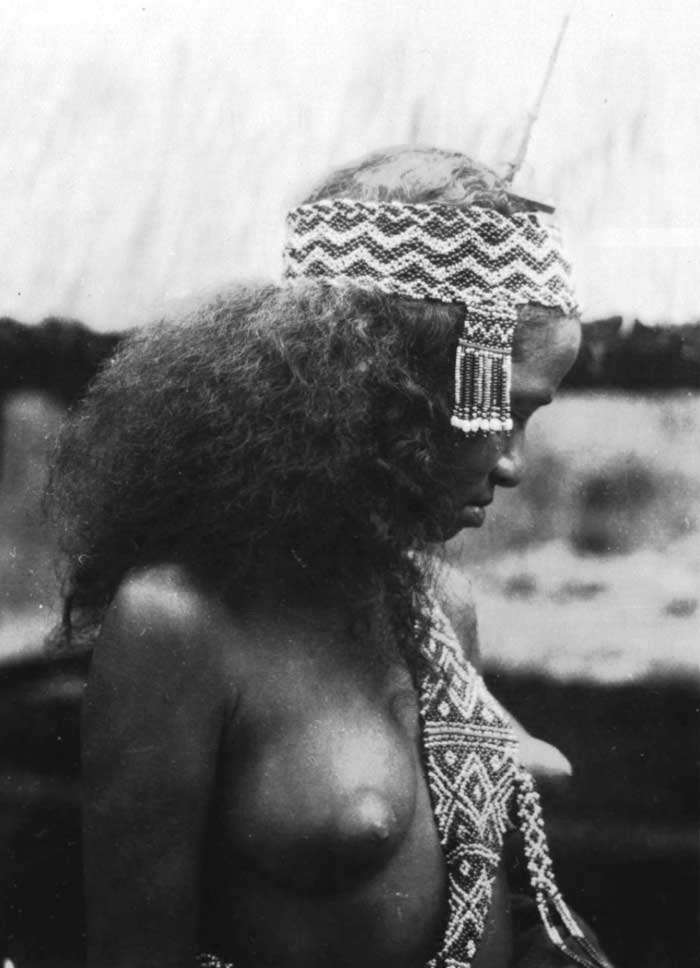

Two sirih pinang baskets collected in Probor by the Vatters in 1929

The following day they rode further south to Aluabän (now Aluaben) where they were welcomed with a lego-lego dance, before continuing on to Worbain. Although there was no weaving in these villages, the Vatters did encounter people dressed in local ceremonial costumes. The men were attired in woven loincloths and some had donned heavy buffalo-skin armour and armed themselves with swords, bows and arrows and leather shields. The women were bare-breasted and wore black and blue sarongs decorated on the edges with brown and white patterns.

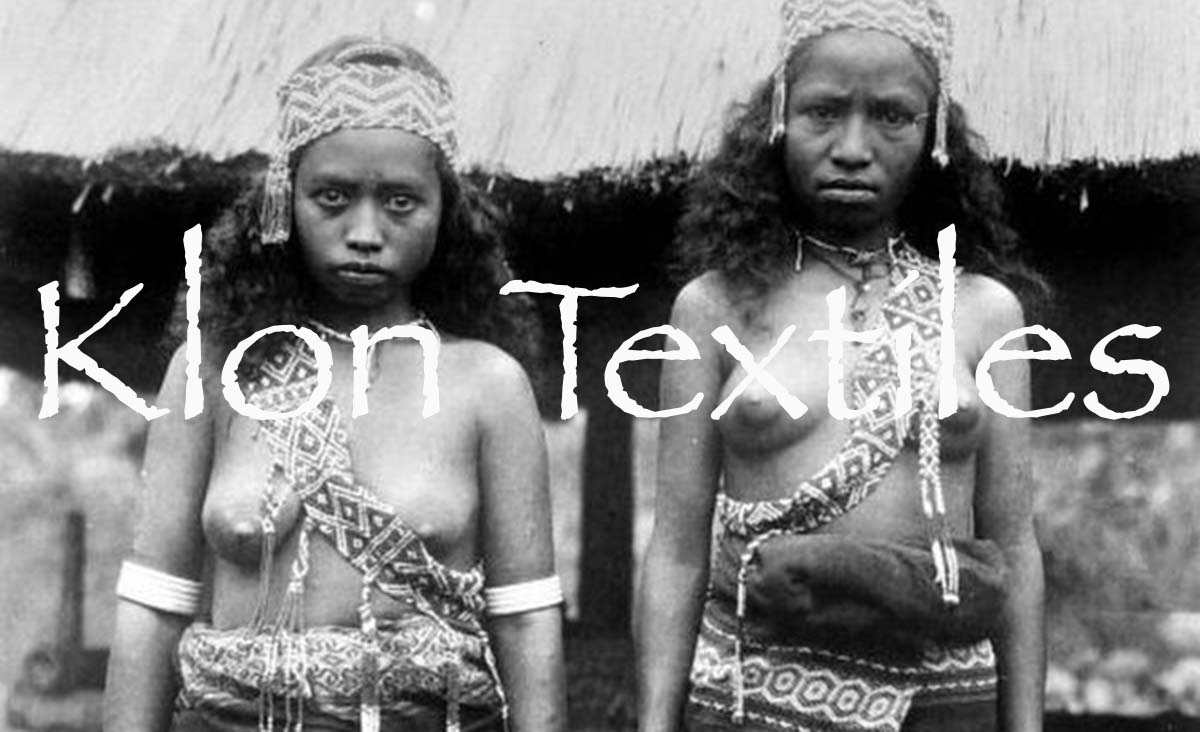

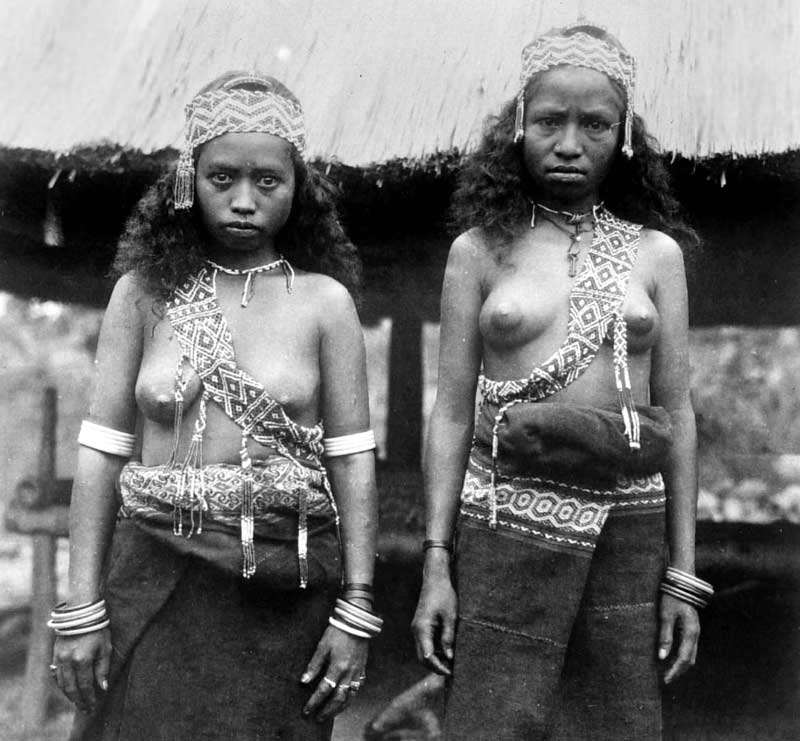

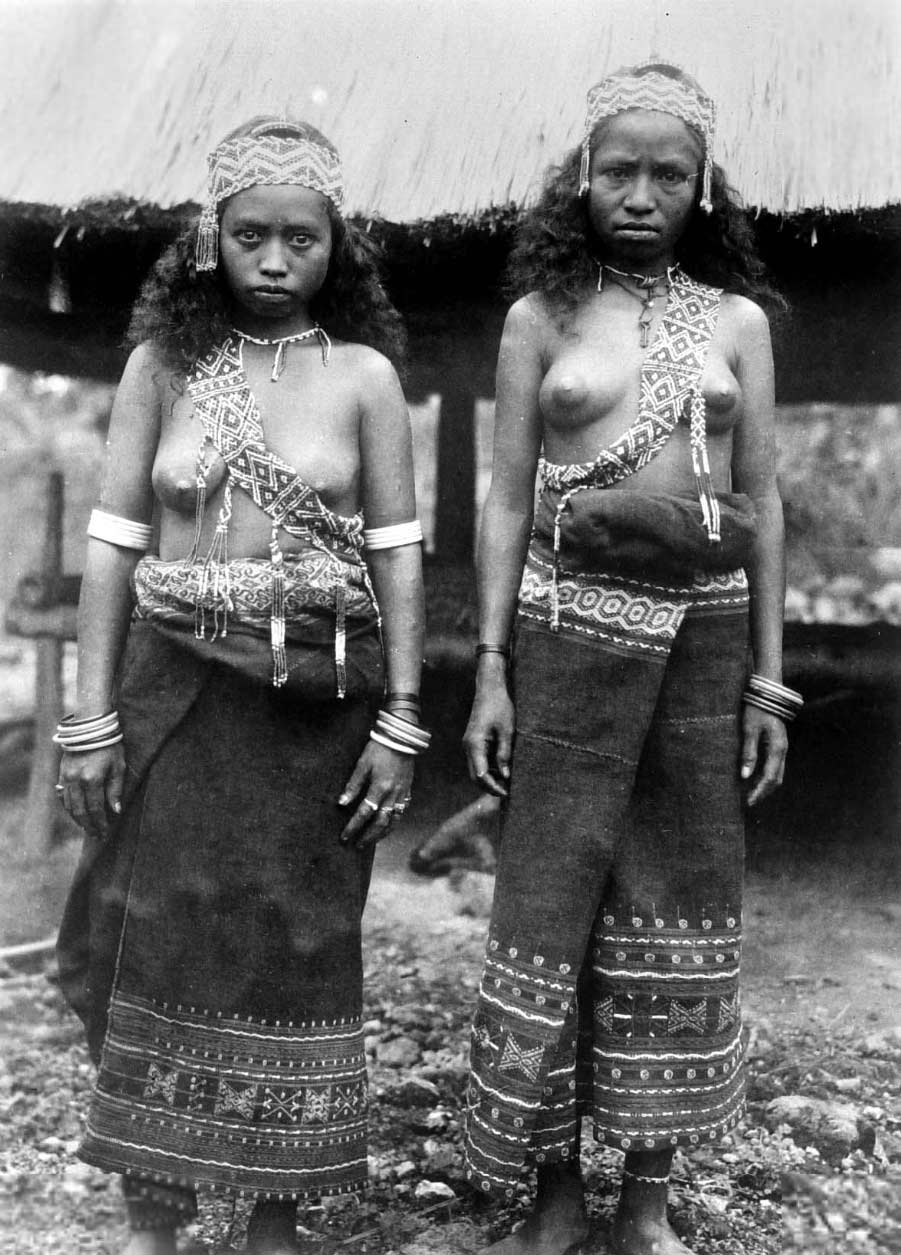

Two daughters of the chief of kampung Worbain, dressed in ceremonial dance costume.

Ernst Vatter 1929.

The Vatters located only one weaving village in the Klon region – Halerman, located just inland from Margeta Bay and only 10km west of the Masin village of Buraga. It seems that this provided the textiles for all of the other Klon villages. As the Vatters arrived in Halerman they were welcomed with a lego-lego dance, the dancers arranged in a spiral around a central stone. Unlike the girls photographed in Worbain, some of the female dancers here were wearing sarongs that covered the breasts.

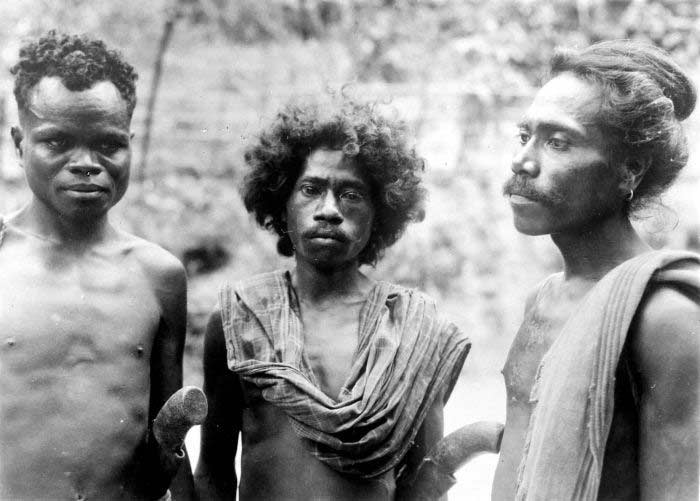

During their brief travels in the Klon region, the Vatters were struck by the extraordinary variety in the physical appearance of the local people – some had very dark skin and very frizzy hair while others were lighter skinned and had slightly wavy or almost straight hair. They also saw signs of a western racial element. Clearly the community that they travelled through was composed of mixed racial types but might also have contained individuals from other ethno-linguistic groups, such as the Klon, Hamap and Abui.

Three men with diverse appearances in Halerman

(Image courtesy of the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

During his posting on Alor and Pantar, Lieutenant (later Major) H. Sjoers collected numerous ethnographic objects including some textiles that he later donated to the Koninklijk Indisch Instituut in Amsterdam.

Return to Top

Klon Textiles

Throughout eastern Indonesia, hand-woven textiles are mainly produced by communities living on, or close to, the coast. This is because the essential ingredients, cotton, indigo and morinda, grow in dry coastal environments and not in the mountains. As a consequence, the inland people must barter their food to obtain cloth from the coastal weavers. In some cases this is enshrined in adat. As the Vatters discovered, this demarcation is also found among the Klon, with the coastally located Paneia producing textiles, which they then traded to the inland Bring. However at the time, the Vatters did not realise that the Klon were composed of these two ethno-linguistic sub-groups, only one of which had a tradition of weaving.

Sadly we have extremely limited insights into the textiles of Kerajaan Kui in the past. It is likely that barkcloth was once common, as it was among many of the other tribal groups of Alor. Imported cloth woven elsewhere would have been seen as superior and highly valued. In 2003-2004 Louise Baird discovered that the Kafoa people, who relocated to the hamlets of Lola and Habollat just north of the Klon-speaking region in the 1960s, continued to wear clothing made of bark up to the time of their resettlement (2017b).

Unlike the Alorese and Blagar weavers living along the coastline of the nearby Pantar Strait, the Klon Paneia have no tradition of producing warp ikat. They decorate their textiles using a combination of stripes and the complementary warp technique that is widespread on Timor Island just 75 km to their south. This suggests that the Klon adopted weaving from immigrants arriving from the central north coast of Timor. Klon textiles are also very similar to those produced by the neighbouring Islamic Masin, often referred to as the Kui, indicating common origins.

In 1851 the Dutch Resident on Timor, D. W. C. Baron van Lynden, observed that the people of Alor and Pantar were divided into:

- the Muslim coastal people living in enclaves of Pandai (Northeast Pantar), Blajar (Blagar, East Pantar) and Bamoesang (Baranusa, East Pantar) on Pantar Island, and Allor (Alor Besar) and Koewi (Kui) on Alor Island, and

- the ‘less civilized, contentious, untrustworthy and pagan’ mountain people (332).

The mountain people did not weave and, like the Dayaks of Borneo, they dressed in bark or cotton loincloths, obtaining their cotton from the coastal communities.

Referring to Alor as a whole, van Lynden claimed that cotton was limited and imported from the Solor islands but both indigo and morinda were planted and used just as on all the other islands, the latter combined with lobak (loba or Symplocos) (1851, 331).

As mentioned before, the first Dutch incursion into Alor Island led by Lieutenant Adelberg in 1910 does not appear to have covered the far south western region occupied by the Klon. However a report on the expedition’s findings published four years later included information provided by the Controleur of Alor, Meulemans, that the mountain population of Kui was divided between two tribes: the Barawahieng (a term applied to the Abui) and the Kelong (Klon) (Anonymous 1914, 76). The report noted that in general there was little industry on the island, the main activity being the weaving of coarse sarongs by the coastal inhabitants. However this comment must refer to coastal communities other than the Klon, who were not visited at that time. It also mentioned that the coastal population of Kerajaan Kui was partly from Timor (Anonymous 1914, 77).

During their brief exploration of the Klon region in April 1929, the Vatters located only one weaving kampung – coastal Halerman, located just inland from Margeta Bay. However they did not visit the other coastal Klon kampungs of Margeta and Manatang, the latter located just 3 km west of the Masin village of Buraga. They found that the weavers of Halerman supplied textiles to the inland Klon kampungs occupied by the non-weaving Bring such as Aluaben and Worbain.

Compared to the Lamaholot weavers of the Solor region, the looms used in Halerman were narrower and the circular warps were longer. The cloths were patterned using a warp float technique: ‘the warp threads are only bound by the weft threads at certain intervals, otherwise laying loosely on the surface of the fabric’ (Vatter 1932, plate 61.1).

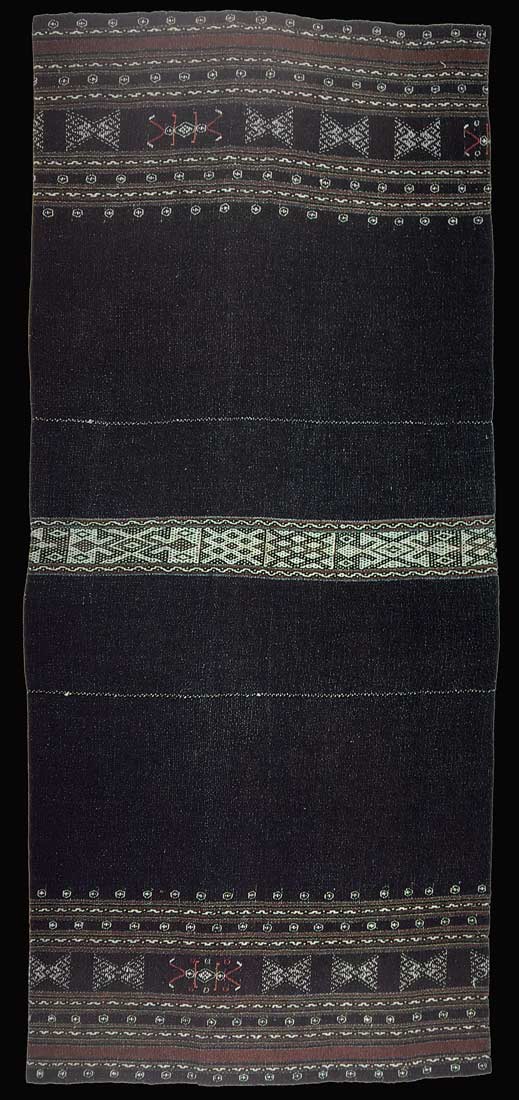

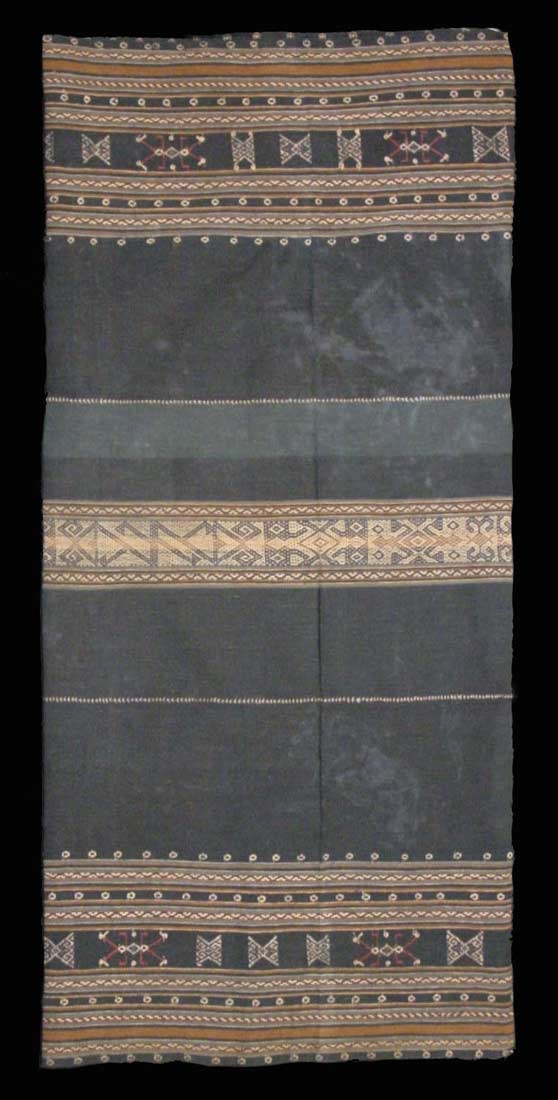

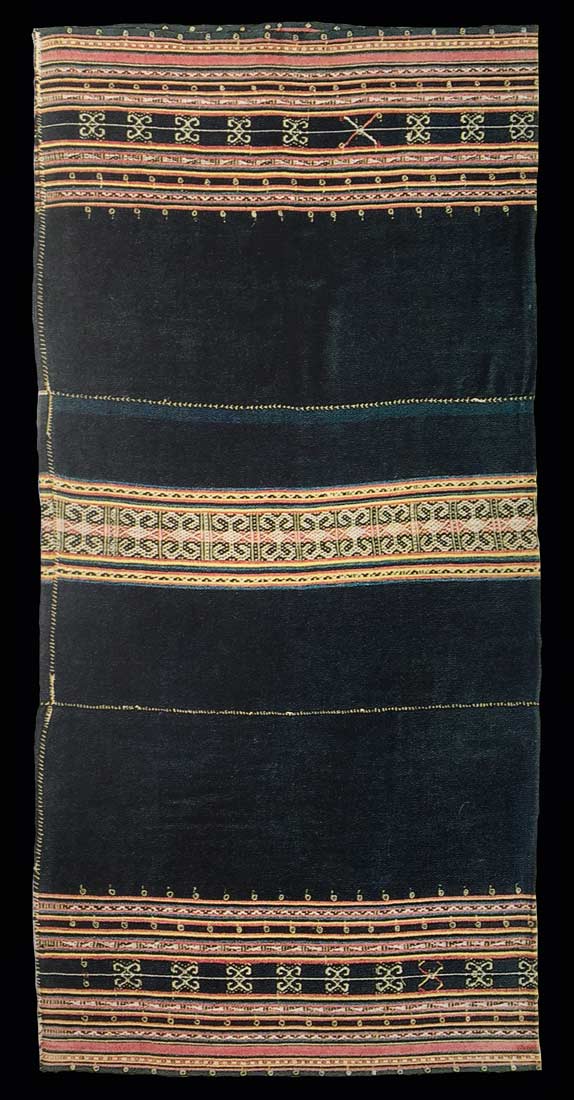

Loincloths were made from a single loom length of cloth, while selendangs and sarongs were made from two or three lengths sewn together. The decoration was confined to either the borders of the outer panels of the sarongs or the centre of the central panel. The sarongs were coloured blue-black, while the borders were white, brown or blue.

A weaver at Halerman photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Vatter acquired two women’s sarongs, which he labelled as ken (the same term used by the Masin), two men’s loincloths labelled emel (the same name used by the Klon Bring and similar to the term mol used by the Masin) and three shoulder cloths, labelled nu.

According to G. A. M. van Galen, the Controleur of Alor in 1946, the mountain people of Alor did not understand the art of weaving, apart from a few kampungs in Probur in Kerajaan Kui (1946, 64). It is likely that van Galen was mistaken, assuming that the textiles worn by the Klon in the inland Probur region were produced locally rather than further south on the coast.

In 2003 and 2004 the Leiden linguist Louise Baird spent four months in the Bring-speaking Klon hamlet of Mataraben in Desa Probur (2005, 11). During her stay she never encountered any weaving activities in that area (2017b).

However during her research she did record several terms for clothing and apparel among the Bring-speaking Klon (2008). The terms she recorded for a cloth are hlim and wei, a loincloth is an emel, a wrap is a kok or oglor, while a blanket is either a makoi or a noq.

More recently Hanna Choi documented a number of textile and weaving terms used by villagers in kampung Hopter in Desa Halerman, just north of kampung Halerman and south of Worbain, but recorded in kampung Fanatung next to Moru (Choi 2015). A sarong is a ken, a necklace is a baab, clothing is pèkar, thread is kap and weaving is gèdiing mèrhaain. It is unclear if the Paneia use the same terms.

Return to Top

Klon Paneia Women's Costume

According to Ernst Vatter a Klon Paneia woman’s sarong is called a ken, the same term used by the Klon Bring. Both the Abui and the Wersing of Kolana use the terms ken or keng (Kratochvil 1976, 27 and Kratochvil 2007, 469 and 495).

Howard refers to a Klon sarong illustrated with a small black and white image by Khan Majlis and termed a keng mei geweng (2008, 45). Although this has end panels that are similar to those found in Klon sarongs, it is actually four-panel and the middle panels are warp stripes. Khan Majlis actually attributes the sarong to Kolana in East Alor, not to the Klon in Southwest Alor (1991, 222 fig. 201). Yet it does not resemble a sarong from Kolana. Its provenance must be suspect.

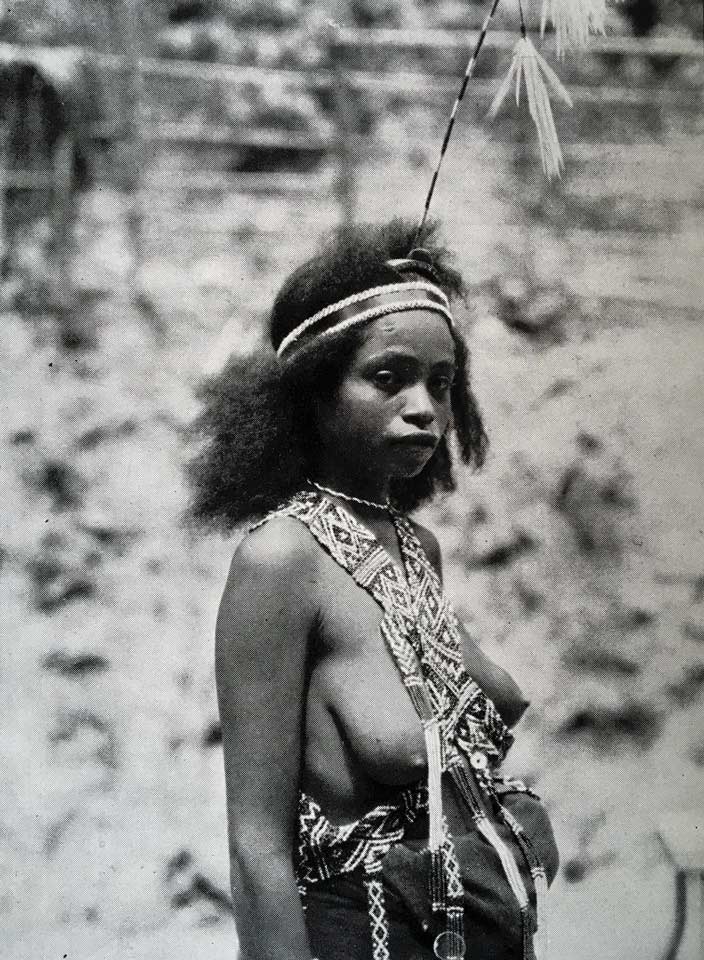

Vatter provides us with a good description of the ceremonial costumes worn by the female Klon Bring dancers at Worbain. They wore black and blue sarongs with brown and white patterns on the edges and ‘picturesque’ beaded jewellery. The latter consisted of headbands, necklaces, belts worn over a sarong or as a shoulder sash, sometimes crossed in pairs over the breasts. Their arms were decorated with many bracelets, some made of rattan and known as kil, others made from seashells and known as lak.

The solid red headbands were called pip and were made from rattan and palm leaf decorated with rows of nassa shells.

The sashes and belts were made from bands of red, white and black imported beads (known as mem) arranged in geometric zigzag and diamond patterns joined using bast fibre cords. Some were embellished with thinner beaded pendants decorated with beads and seeds. Vatter thought the beaded bands looked delightful on the bare brown skin of the dancers. A broad carved bamboo comb, known as a kir, decorated with flakes of mother-of-pearl (bing) was inserted into the hair, which supported a thin upright stick, wrapped with coloured cotton threads and decorated with a feather tuft.

The beaded sashes and headbands were called bab, while the beaded dance belts were called bab uhunkal (literally ‘a sash worn as a belt’).

A beaded bab uhunkal collected by the Vatters in Probur

Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

A bare-breasted dancer at Worbain wearing a narrow headband known as a pip, a kir bamboo comb and feather headdress, and red, white and black beaded belt and crossed sashes. Ernst Vatter 1929.

Ernst Vatter also photographed two noblewomen in Worbain, daughters of the local chief who were dressed in similar dance costumes. The women were bare-breasted and were wearing heavy three-panel hand-spun ken sarongs with side seams, decorated with a wide lower band composed of narrower rows that, to our eyes, appear to be woven in discontinuous supplementary weft. Within the band the central row contained large cross-like geometric motifs, either butterfly or bow tie shaped figures or pairs of opposing chevrons, while the outer rows had meanders and small circles. The middle panels of the sarongs were completely plain apart from a central lateral band of warp float weave, possibly complementary warp. The two noblewomen were also adorned with beaded necklaces, armbands, and ankle bands, along with many carved bracelets.

Apàn and Bikělà, two young daughters of the chief of Worbain in dance jewellery, photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929. Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen. Creative Commons Licence

Above and below: Bikělà showing the zigzag and diamond patterning of her shoulder sash and headband.

Vatter acquired two women’s sarongs labelled as ken, still held in the collection of the Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main.

One of the three-panel kens shows that the central band of the middle panel is woven in complementary warp using contrasting white and black yarns, while the small geometric motifs are woven in discontinuous supplementary weft, using white, red and green yarns. The appearance is very similar to the ken worn by Bikělà at Worbain with rows of bow-tie- or hourglass-shaped motifs (possibly representing bronze moko drums) flanked with rows of small hexagons both woven in supplementary weft. The stick-like motifs resemble two linked anthropomorphic figures.

One of the ken sarongs collected by Ernst Vatter in Halerman

Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

There is a remarkably similar Klon ken in the collection of the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, acquired at some time prior to 1952. It has exactly the same stick-like motifs.

A three-panel ken probably from Halerman

Tropenmuseum TM-2204-3 Creative Commons

Finally Howard has illustrated a more modern version of a ken from Halerman decorated with synthetically dyed red and yellow warp stripes (2008, 183). The dominant motif is a small diamond sprouting two pairs of scrolls or hooks, the same motif that was once reserved for the ruling Raja clan of the Masin of Kerajaan Kui – Ler Araman. Howard provided close up details revealing the warp float structure of the patterned bands.

Another three-panel ken from Halerman

The narrow plain stripes are made from synthetically dyed yarn

Vatter described one of the weaving techniques used to produce some of the decorative bands as follows:

[The pattern] is produced by the warps, in that they are only bound by the wefts at certain intervals, as required by the respective pattern, but otherwise float loosely on the surface of the fabric.

In fact two main techniques were used to produce these sarongs. The discrete motifs in the borders of the outer panels were formed using discontinuous supplementary weft, incorporating additional short lengths of white or red weft, while the more complex decoration in the central lateral band of the middle panel and the narrow flanking bands in the borders of the outer panels were formed using a technique that we personally call complementary warp or complementary warp float. This is because the warps are divided into two sets that are ‘complementary to each other and co-equal in the fabric structure’ (Emery 1966, 140).

Mattiebelle Gittinger described the latter technique as ‘warp-faced alternating float weave’. Some Western back-strap weavers call it ‘simple alternating float weave’. This requires warping up the loom with alternating warps of contrasting colours, so that the upper shed is composed of just one colour and the lower shed is composed of the other. If these warps are woven up in plain weave they will produce a band with simple alternating lateral stripes. However if some of the warps in one of the coloured sets are allowed to float over three or five wefts, it is possible to create a geometric pattern as complex as the weaver desires. Longer floats are generally avoided because they weaken the structure of the weave. If a repetitive pattern is required the warps can be pre-programmed using small sticks, but otherwise the weaver selects the warps that will float rather than interlace using her fingers or a pointed pick.

Interestingly this technique is widely employed on neighbouring Timor Island, where it is called sotis or lotis by the Atoni Pah Mèto and foit or fafoit by the Tetun (Hamilton and Barkmann 2014, 42). These are loose terms that are applied to any warp float technique, including supplementary warp (Yeager and Jacobson 2002, 72). This underlines the view that weaving was introduced to the coastal Klon by immigrants from Timor.

Return to Top

Klon Paneia Men's Costume

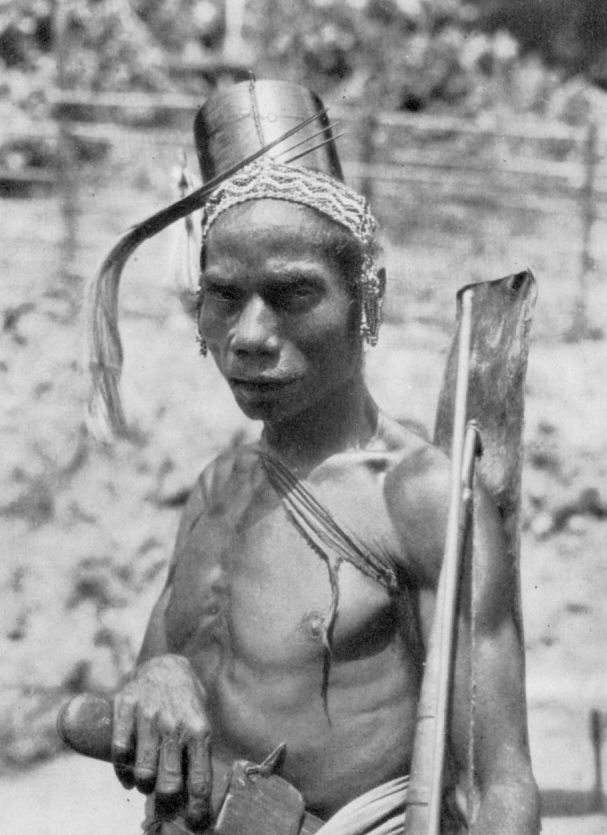

In the inland Bring Klon village of Aluaben, Ernst Vatter recorded that the men were dressed in woven loincloths. Some had donned heavy buffalo-skin armour and armed themselves with swords, bows and arrows and leather shields.

A Klon Bring native of Aluaben with a bow and arrow, wearing a loincloth, buffalo skin armour and a rear feather decoration. His parang and arrows are held in a wide belt woven from bast fibre, which protected his stomach. Ernst Vatter 1929.

When he arrived in the coastal Paneia Klon village of Halerman the following day, his description of the men’s textiles was equally limited. They wore woven loincloths made from a single loom length of cloth. He was more interested in the cylindrical headdresses, known as a kelep edir, worn by some of the male lego-lego dancers, but was disrespectful in his comments:

Some of the dancing men were adorned with the grotesque hair cylinder, which is still widespread in central Alor, but has almost completely disappeared here in the west (Vatter 1932, 244).

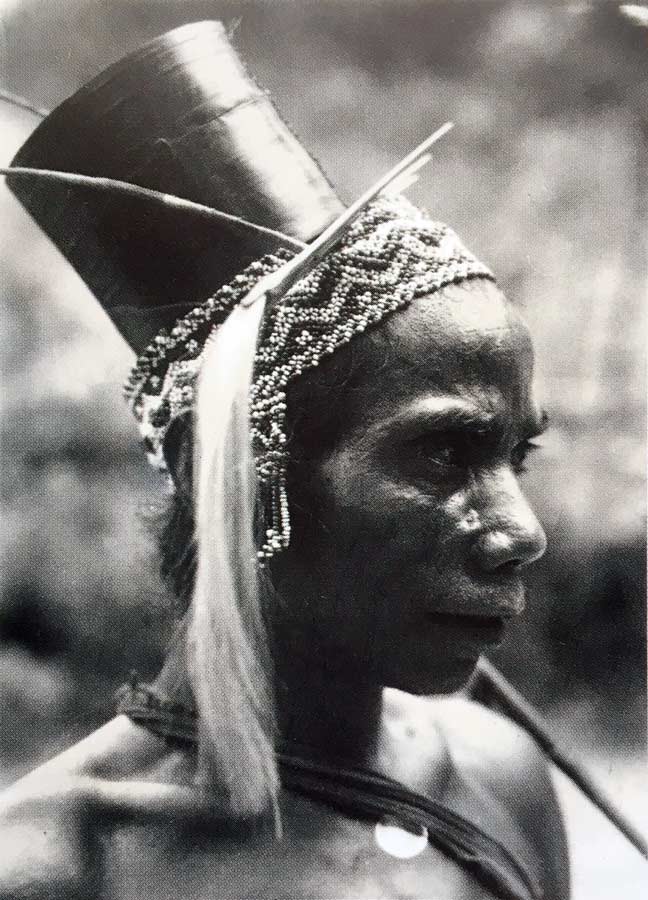

Above and below: Male dancers at Halerman wearing cylindrical headdresses. Some of these appear to have been wound with cane. Ernst Vatter 1929.

He went on to describe the kelep edir in some detail:

It consists of two or three strips from the leaf sheath of the palm tree, which are coloured red, clipped together with small pieces of sheet brass and joined to form a tube by a longitudinal seam. The red colour is obtained from kaju merah, the ‘redwood tree’. To put on this jewellery [sic] the hair is first twisted in a bundle and wrapped with a cord, then the cylinder is pushed over it. The men wore a beaded band around their forehead, through which was a comb was stuck into their hair decorated with a tuft of white goat hair and a stick with feathers. The deep red of the cylinder, the white, black and red patterned beaded band and the yellow bamboo comb with tufts of goat hair and feathers contrast with the dark brown of the skin and the deep black hair that is visible under the tiara, a colour harmony of wild beauty, from which we can only provide a weak impression by means of common photography.

The hair cylinder was often worn with a beaded brow band, called a pip, just like the women’s headdress, and a kir bamboo comb.

A native of Halerman with a kelep edir hair cylinder, beaded brow band and bamboo comb with a goat hair tuft. He is armed with a parang, bow and wooden shield. Ernst Vatter 1929.

Vatter acquired two emel loincloths from Halerman, one black with brown patterned selvages and the other white also with brown patterned selvages. The patterning on the side bands was woven in complementary warp. Both have narrow lateral end bands woven in continuous supplementary weft. In the black emel these are combined with simple geometric motifs woven in discontinuous supplementary weft.

The end section of a man’s black emel loincloth collected by Ernst Vatter in Halerman

Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

The end section of a man’s white emel loincloth collected by Ernst Vatter in Halerman

Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

An elaborate emel illustrated by Khan Majlis has four terminal rows of discontinuous supplementary weft, including one of anthropomorphic figures (1991, 221). It is finished with a combination of woven and wrapped fringes, reminiscent of similar fringes found on Timorese loincloths, headdresses and betel bags.

A more modern example but made in a similar style was woven using synthetically dyed yarns:

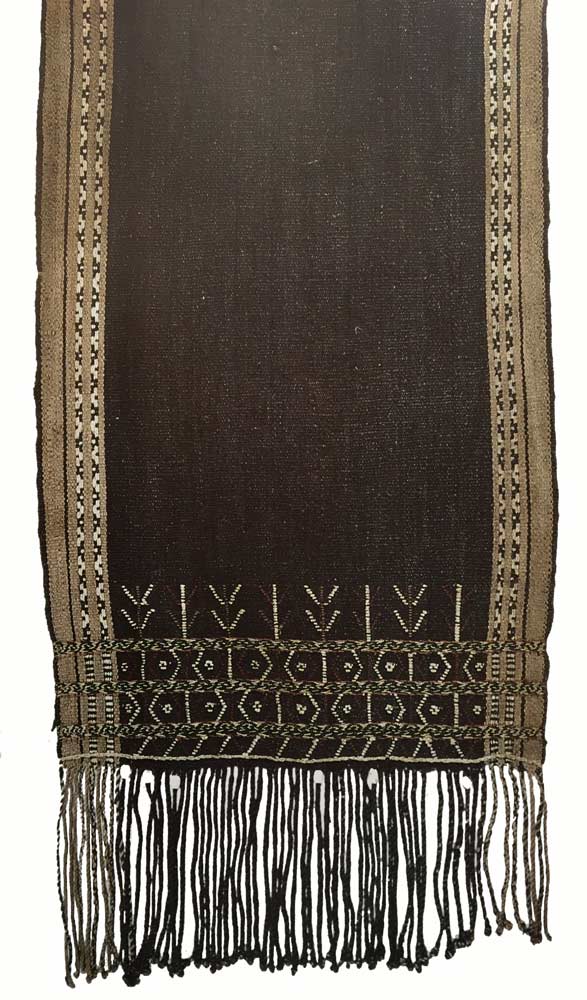

Of the three nu two-panel fringed shoulder cloths collected by Vatter, two had black central sections with black, white and brown side bands decorated with strips of complementary warp, while the third had a natural white cotton central section with brown and white side bands.

A similar two-panel nu in the collection of the Tropenmuseum has a plain black centre and brown side bands composed of a cluster of plain warp stripes and narrow bands of complementary warp decorated with simple geometric motifs.

A nu collected at some time prior to 1954

Tropenmuseum TM-2309-21 Creative Commons

A more complex nu from Halerman illustrated by Michael Howard has broader side bands flanking a central band decorated with a repetitive row of eight-pointed stars. The latter is woven in supplementary, rather than complementary, warp. It also includes inner bands of plain warp stripes. The motifs woven in the end sections in discontinuous supplementary weft include a row of anthropomorphic figures.

A nu from Halerman decorated with supplementary warp

Howard 2008, 185

A somewhat similar two-panel nu illustrated by Khan Majlis has red, ochre, blue and white side stripes and discontinuous supplementary weft end decorations incorporating rows of the same anthropomorphic and hour-glass (moko?) motifs (1991, 220).

Howard asserts that the quite different Alor men’s blanket illustrated by Sylvia Fraser-Lu (1988, ill. 46) is a nu woven by the Klon (Howard 2008, 45). However its lateral end band is woven in the warp-wrapping technique known in the Wersing language as sudi, which clearly shows that it is a keng limi woven by the Wersing people of the Kolana region of East Alor.

A later Klon nu with synthetic red warp stripes was also woven with side bands decorated with eight-pointed stars. These too are woven in supplementary warp, but using long floats over up to seven wefts, resulting in poor interlacing and therefore a relatively unstable structure.

A later nu from kampung Halerman

Some of these blankets are very similar to the keng limi woven by the Wersing, who live in scattered settlements along the southern coast of Pureman and on the eastern coast of Kolana. As already mentioned, the Dutch military detachments that visited Kerajaan Kui in 1910 discovered that its coastal population was partly from Timor (Anonymous 1914, 77). Over time, the Timorese immigrants gradually spread eastward from Kui and settled successively in Pureman and Kolana.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Badan Pusat Statisik, Kabupaten Alor, 2018. Kecamatan Alor Barat Daya dalam Angka, Kalabahi.

Baird, Louise, 2003. Language Klon, Bring

Baird, Louise, 2003. Language Hamap, Moru

Baird, Louise, 2005. Doing the split-s in Klon, Linguistics in the Netherlands, vol. 22, pp. 1–22, Doetjes.

Baird, Louise, 2008. A grammar of Klon: a non-Austronesian language of Alor, Indonesia, Pacific Linguistics, Canberra.

Baird, Louise, 2017a. Kafoa, The Papuan Languages of Timor, Alor and Pantar, vol. 2, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG

Baird, Louise, 2017b. Private communication.

Choi, Hanna, 2015. Language Klon Hopter, Field Notes collected by Hannah Choi on 2015-10-21 for the language spoken at Fanating

https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/kelo1247-hopteDalen, A. A. van, 1928a. Van strijd en overwinning op Alor, H. J. Spruyt, Amsterdam.

Dalen, A. A. van, 1928b. Uit de duisternis tot het licht, H. J. Spruyt, Amsterdam.

Emery, Irene, 1966. The Primary Structure of Fabrics, Thames and Hudson and the Textile Museum, Washington D.C.

Fraser-Lu, Sylvia, 1988. Handwoven Textiles of South-east Asia, Oxford University Press, Singapore.

Hägerdal, Hans, 2010. Van Galen’s memorandum on the Alor Islands in 1946. An annotated translation with an introduction, part 1, HumaNetten, vol. 25, pp. 14-44.

Hamilton, Roy W., 2010. Alor, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 304-305, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Hamilton, Roy W., 2010. Shoulder Cloth: Kui, Alor, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 318-319, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Hamilton, Roy W. and Barrkman, Johanna, 2014. Textile Style Areas in Timor, Textiles of Timor: Island in the Woven Sea, pp. 39-97, Fowler Museum, UCLA, Los Angeles.

Holton, Garry, and Robinson, Laura C., 2017. The internal history of the Alor-Pantar language family, The Alor-Pantar languages, pp. 49–91, Language Science Press, Berlin.

Howard, Michael C., 2008. Alor, A World between the Warps: Southeast Asia’s Supplementary Warp Textiles, pp. 45 and plates 434-442, White Lotus Press, Bangkok.

Ilyas, Awaludin, 2017. Pemekaran Wilayah Kecamatan ABAD bagian selatan dalam Tinjauan Pengembangan Wilayah

Jacobsen, Johan Adrian, 1896. Reise in die Inselwelt des Banda-Meeres, Verlag von Mitscher & Röstell, Berlin.

Khan Majlis, Brigitte, 1991. Woven Messages: Indonesian Textiles Tradition in Course of Time, Roemer-Museum, Hildesheim.

Kinanggi, Nasarudin, Raja Muda of Kerajaan Kui, 2018. Private discussions in Moru.

Kleden-Probonegoro, Ninuk, 2006. Identitas etnolinguistik orang Hamap dalam perubahan, LIPI, Jakarta.

Rodemeier, Susanne, 2010. Islam in the Protestant Environment of the Alor and Pantar Islands, Indonesia and the Malay World, vol. 38, no. 110, pp. 27–42.

Samper Carro, S.C et al., 2019. Somewhere beyond the sea: Human cranial remains from the Lesser Sunda Islands (Alor Island, Indonesia) provide insights on Late Pleistocene peopling of Island Southeast Asia, Journal of Human Evolution, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.07.002.

Schapper, Antoinette, and Wellfelt, Emilie, 2018. Reconstructing contact between Alor and Timor: Evidence from language and beyond, NUSA: Linguistic studies of languages in and around Indonesia, vol. 64, part 2, pp. 95-112, Tokyo-Jakarta.

Stokhof, W. A. L., 1975. Preliminary notes on the Alor and Pantar languages (East Indonesia), Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Verbeek, R. D. M., 1914. De Eilanden Alor en Pantar: Residentie Timor en Onderhoorigheden, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. 31, pp. 70-102.

Wellfelt, Emilie, 2016. Historyscapes in Alor: Approaching indigenous histories in eastern Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden.

Yeager, Ruth Marie, and Jacobson, Mark Ivan, 2002. Textiles of Western Timor: Regional Variations in Historical Perspective, White Lotus Press, Bangkok.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 11 June 2020.