KontAsian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

The Mangili Region

The Local History of Mangili

The Colonial History of Mangili

The Former Rajas of Mangili

Ethnography

The Anthropology of the Native Mangili Dam

Sumbanese Textile Terminology

Cotton Cultivation in Mangili

Warping Up and Binding

Natural Dyeing in Mangili

The Mangili Back-Tension Loom

Mangili Textile Motifs

The Textiles of Mangili

The Richardson Collection

Modern Mangili Textiles

Epilogue

Bibliography

Introduction

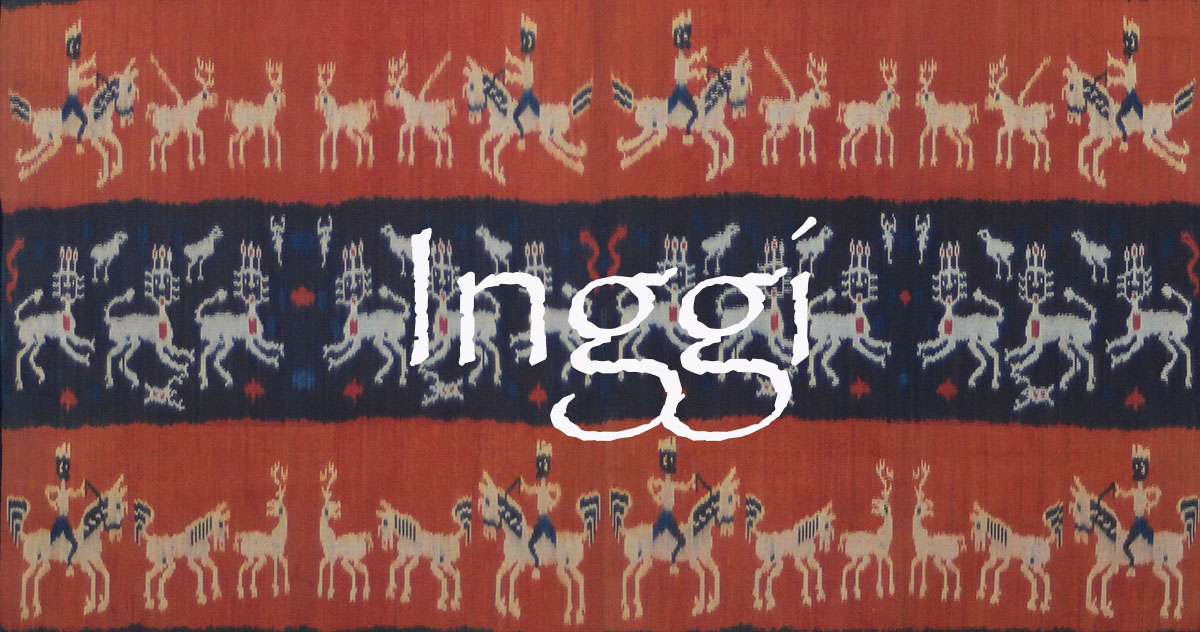

An inggi is a man’s blanket from Mangili, a former self-governing domain on the southeastern coast of East Sumba. Decorated with warp ikat, it is similar in size and general layout to the better-known hinggi that is produced in the central eastern regions of Kambera and Rindi.

However inggi are different – they have distinctive layouts, colourings and motifs. Although there are exceptions, most are easily identified by their alternating deep red and dark black lateral bands, each decorated with rows of small repetitive motifs such as riders on horseback, warriors, dancers, lions, cockerels, fish and shellfish. The motifs are predominantly white, set against a red or black ground. Inggi are only rarely finished with a kabakil.

A new inggi kombu kambata bara on display in Kaliuda in 2015

Note the crocodiles, Chinese dragons and the royal Dutch coat-of-arms

Just like the hinggi, they are always made as a pair, one intended to act as a hip wrapper the other a shoulder cloth. In the past inggi were primarily coloured with just two natural dyes, indigo and morinda. Unlike some hinggi they were never over-daubed with yellow kayu kuning.

The Regent of East Sumba, Gidion Mbiliyora, dressed in two inggi and a tiara headdress

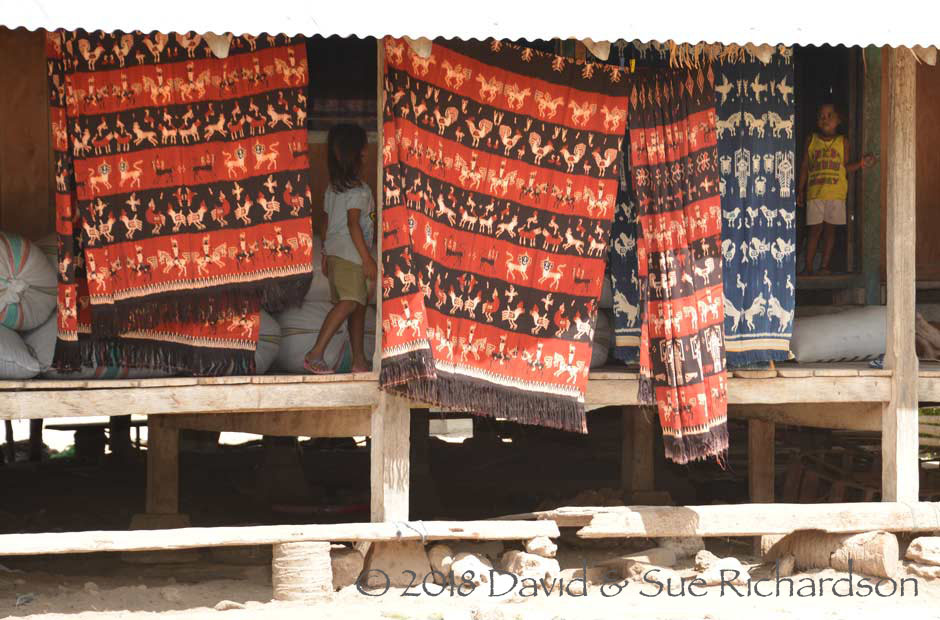

Guidebooks attract tourists to this region by claiming that the village of Kaliuda in Mangili is home to some of Sumba's best ikat (see for example, Wheeler 1997, 337; Turner 1998, 371). While this might have been partially true in the past it is hard to substantiate today. Although inggi are still being currently produced in significant numbers, especially for the local Sumba market, price pressure has forced producers to employ simpler designs with a more restricted range of motifs. Some look harsh and brutal compared to the subtle high-quality cloths of the past.

Return to Top

The Mangili Region

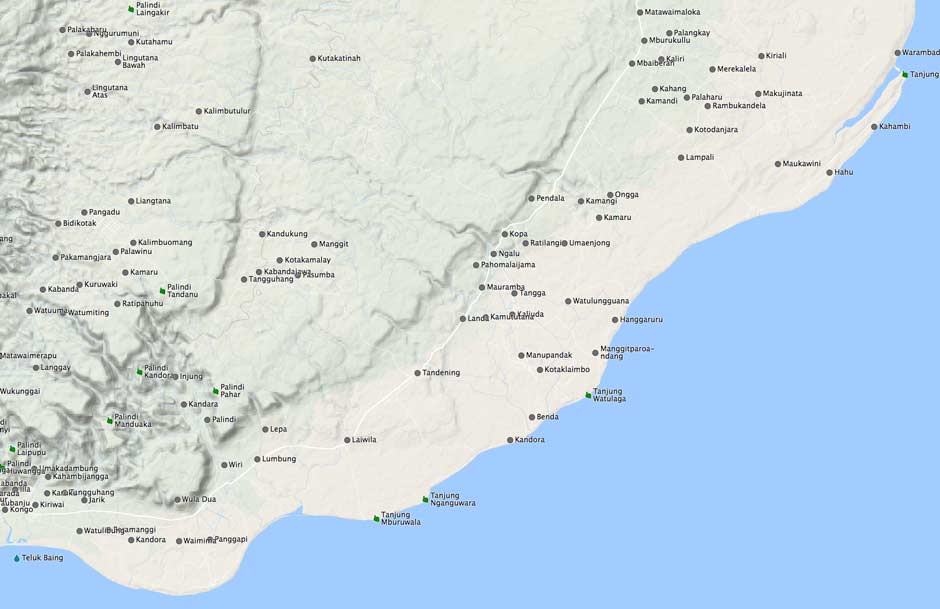

The small domain of Mangili is located on the southeast coast of Sumba, about 100km south of Waingapu – just a two-hour drive by car. The Luku Aumarapu river (also known as the Luku Marapu or Rindi Majangga) separates Mangili from the domain of Rindi in the north while the Luku Wuluwamu separates it from the domain of Waijelu in the south (Forth 1981, 7). The landscape is characterised by a dry flat low-lying coastal plain fringed with sandy beaches and coral reefs and an inland range of hills carved by streams flowing eastwards out of the Masu-Karera highlands. Whereas the uplands to the north of Mangili are covered in savannah grassland, those in Mangili are densely wooded.

The old capital of Mangili was the ceremonial hilltop village of Paraingu Mangili, but this was abandoned a long time ago when the clan leaders moved down into the lowlands.

The region of Mangili in southeast Sumba

As an indication of how isolated this region used to be in the recent past, the journey to Waingapu took about a week in 1970 (Twikromo 2008, 42). Hardly any local roads were asphalted at that time and there were few bridges crossing the rivers, so people had to walk or ride horses to reach Melolo before continuing on buses or trucks to Waingapu.

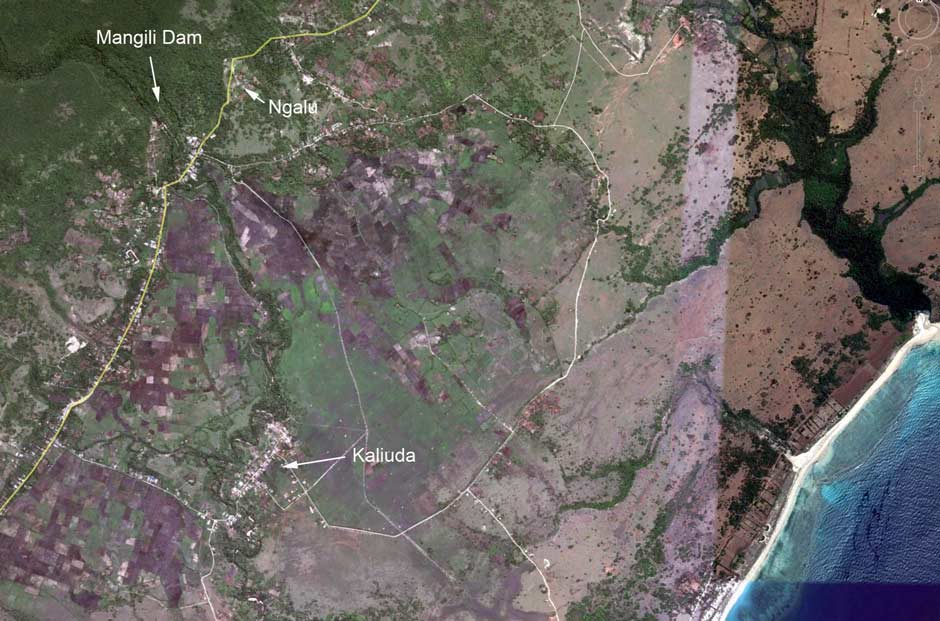

The lowland coastal region frequently suffered from severe water shortages and occasional famines (parambangu) during the long dry season from April to November (Onvlee 1949, 1). In 1936 the Netherland Indies Government funded an irrigation project based on the construction of a dam across the Luku Bakulu. It was completed between 1939 and 1940 and led to a significant increase in the acreage under agriculture. In about 1979 a new dam was constructed across the Luku Luanda (sometimes called Luku Kaliuda) close to Ngalu, turning the area below the escarpment into an agricultural oasis. It is now one of Sumba’s major rice-producing regions. Even so there was a bad drought in 1994 that caused crop failures and food shortages (News and Views Indonesia 1996, vol. 9, issue 90, 11).

The villages of Mangili located below the escarpment and on the coastal plain

(Map courtesy of Tripcarta)

The population of Mangili is mainly confined to the villages that lay below the edge of the escarpment and further out on the coastal plain, watered by the streams that flow down from the highlands. They include the important weaving villages of Ngalu (sometimes Nagalu) and Kaliuda.

View over the coastal plain of Mangili from the highlands

The location of the Mangili Dam and the region that it irrigates

(Image courtesy of Google Earth)

The important kampong of Kaliuda lies on the dry coastal plain about 3½km from the beach. It had about 3,000 inhabitants in 2002, 56% of whom were Sumbanese and 42% Savunese. Desa Tanamanang, which lies north of Kaliuda, was selected as the location for demonstration plots of the cotton farming development programme in 2008, located on the Kaliongga watershed (Nugrohowardhani 2014).

The weaving hamlet of Kaliuda

The Dutch referred to Mangili as Mendjéli and until 1912 it was regarded as a separate landschap or subdistrict of Sumba (Roos 1872, 26; Ten Kate 1894, 583). Following the death of the Raja of Mangili in 1911 and the imposition of direct colonial rule during the following year, the northern part of Mangili was transferred to Rindi. A little later, all of Mangili was annexed to Rindi to form the landschap of Rindi-Mangili within the afdeeling of Sumba within the Residency of Timor (Forth 1981, 13). Following the reorganisation of Sumba into four districts or onderafdeeling by Assistant Resident A. Couvreur in 1915, Rindi-Mangili became a zelfbesturende landschaps within the onderafdeeling of Sumba Timur (Wellum 2004, 26).

Today there is no defined region called Mangili. Pahunga Lodu is divided into eight Desa or villages, namely Kuruwaki, Pamburu, Kaliuda, Tanamanang, Tamma, Lambakara, Mburukulu and Palanggai. Its administrative centre is Tandening in Desa Kaliuda.

Return to Top

The Local History of Mangili

The people of Mangili have a number of different oral narratives expressed in figurative ritual speech, which explain how their ancestors came to this region. They all agree that the first ancestors arrived at Cape Sasar, where they settled and established their traditional customary laws, before spreading across the island (Kapita 1976a, 15-16). A population genetics study of communities across Sumba published in 2007 supports the idea that the first Austronesian settlers arrived on Cape Sasar (Lansing et al 2007).

The first clans to migrate into the Mangili region were the Mbukutu-Mangili Wai, Puhu-Rewatia, Kurungu-Kawàngi, Kawàngi-Wanggi Rara, Kandara-Ana Dàpi, and the Ana Watumanu (Kapita 1976a, 23).

Later they were followed by the Maru, Watu Bulu and Matolangu clans, who travelled down the east coast looking for a suitable site to plant their taro. They made numerous attempts to plant it in the river estuaries, but these were unsuccessful. It was only when they reached the estuary in Mangili that their taro grew well, so they therefore decided to settle (Twikromo 2008, 56-58). This brought them into conflict with the earlier clans who had already settled in this region and a tribal war ensued. The new clans chose Umbu Kaka Manau from the Matolangu clan as their military leader. He was assisted by one of the original clans, the Wanggi Rara.

After triumphing over the established clans, the four main victors – the Maru, Watu Bulu, Matolangu and Wanggi Rara – built the new hilltop settlement of Paraingu Mangili (Nugrohowardhani et al 2015, 122). Despite being newcomers, these four clans became the landowners or mangu tana, claiming rights over all the territory of Mangili and allocating lands to the other clans, including those who would arrive later.

According to Kapita, Paraingu Mangili was also occupied by six additional clans: the Lukunara, Kabulingu, Mbaradita, Weram Ata, Kanjanga Luku and Purungu (Kapita 1979, 83-85). As the settlement increased in size the four leading clans divided the territory in two, on each side of the Ngalu River. The Maru and Watu Bulu oversaw the northern region between the Kaliongga and Ngalu Rivers, known as La Majangga Dita, while the Matolangu and Wanggi Rara oversaw the southern region between the Ngalu and Luanda (Kaliuda) Rivers, known as La Tadulu Wa. The latter region is now known as Desa Kaliuda.

Eventually (probably in the early 1800s) the ruling clans abandoned Paraingu Mangili, and moved down into the lowlands, building new settlements close to their rice fields. The Matolangu, Wanggi Rara and several minor clans moved to kampong Kaliuda. However the Matolangu clan claimed political and economic control over the kampong because the Wanggi Rara clan had failed to produce any sons while living at Paraingu Mangli.

The Kanatangu clan, under the leadership of Umbu Yiwa Tarabihu, arrived in Mangili later. He first married a noblewoman from the Matolangu clan, without paying bridewealth and therefore the offspring of that marriage joined their mother’s clan. Later he married a noblewoman from a third clan and in this case paid the appropriate bridewealth. The offspring of this marriage established the Kanatangu clan in Mangili. Today the Matolangu and the Kanatangu clans control most of the land in Kaliuda and are linked through marriage alliances, the Matolangu clan providing brides for the Kanatangu clan.

Return to Top

The Colonial History of Mangili

The first historical record referring to Mangili comes from Hendrik Engelburt, the opperhoofd (chief) of the VOC at Kupang in 1723. The chief of Mangili had asked for VOC assistance regarding a dispute with Umbu Nggaba Haumara, the ruler of neighbouring Pau (Umalulu), who at that time was supplying sandalwood to the mixed-race Portuguese Topasses based in Larantuka (Roo 1906, 193-194; Kapita 1976b, 146).

The next opperhoofd of Timor, Daniel van den Burgh, visited Sumba in 1751 - the first senior VOC official to do so. There he met with the leaders of eight domains, one of which was Mangili (Roo 1906, 196). This must have been Umbu Lakaru Taraandungu, the leader of the Karindingu clan, who ruled from 1750 to 1775. Van den Burgh believed that he had secured an oral agreement with each domain, including Mangili, under which their leader acknowledged the sovereignty of the VOC and agreed to trade with it exclusively (Wellem 2004, 19-20). It turned out that the tribal chiefs were not as committed as he had naively thought.

Concerned about the intentions of the Topasses on Timor, the Hoge Regeríng, the supreme authority of the VOC in Batavia despatched their commissioner, Johannes Andreas Paravicini, on an important diplomatic mission to Kupang in 1756. There he obtained signatories on a contract of allegiance from a number of regional leaders from the islands of Solor, Savu, Rote and Timor, but just one from Sumba – Umbu Lakaru Taraandungu from Mangili (Kapita 1976b, 146; Fox 2003, 12; Wellem 2004, 19; Hägerdal 2012, 376-381). The contract supposedly applied to eight regents from Sumba, but controversially the Mangili leader took it upon himself to sign it on behalf of all the others without consulting with any of them! On the 9th June Paravicini staged a solemn ceremony in which 92 regional heads, including Umbu Lakaru Taraandungu, swore an oath of allegiance to the banner of the VOC.

It seems that the chiefs of the four leading landowning clans of Mangili, the mangu tana, deliberately avoided coming into direct contact with the VOC (Kapita 1976b, 146-47). They clearly feared the possible adverse consequences of establishing links with an unknown foreign power.

Another opperhoofd of Kupang, Hans Albrecht von Plüskow, sent a further mission to Sumba in 1758. It was led by Hans Erasmus, but included Gabriel Kotting, the Kupang-based brother of the Regent of Dengka from Rote Island, and Bale, the district head of Kupang, who also happened to be married to the daughter of the Raja of Mangili (Erasmus and Leupe 1879; Kapita 1976b, 147). It seems that Mangili was the only domain on Sumba that had established some form of relationship with the VOC at that time.

In 1768 the Raja of Mangili, Umbu Lakaru Taraandungu, travelled to Kupang to ask the VOC to place an interpreter on the island and also to launch an expedition against Raja Sumba Galan of Pau (Umalulu) who was apparently regarded as an enemy by the other domains (Roo 1906, 214-215). A. Carnabe, the new opperhoofd of Kupang, decided the VOC could not intervene militarily but tried diplomacy instead. He posted the translator Corporal J. J. van Nijmegen to Mangili the following year in the hope of improving relations with local leaders and persuading them to expel the Makassarese slavers who were constantly raiding the coasts of Sumba (Roo 1906, 216). In the following year van Nijmegen opened a school in Mangili with a teacher from Ambon but it was short-lived and closed in 1775 (Haripranata 1984, 39).

Following the appointment of B. W. Fockens as opperhoofd of Kupang in 1771 the VOC resisted a move against Umalulu, which was trading with the Topasses, but continued to maintain close relations with the Raja of Mangili. The latter reciprocated with annual gifts – in one year a pair of slave girls.

In October 1774 Kupang sent a senior administrator called Tekenborgh on a 10-week mission to Savu and Sumba. His findings were summarised in a 1775 report (Roo 1906, 219-235). Tekenborgh discovered that Makassarese smugglers were landing on the coast of Mangili every year in 30 to 40 prauws, collecting large numbers of slaves and sandalwood before sailing on to Selura off the south coast of Sumba and to Pasir Island south of Roti to gather large quantities of trepang (sea cucumber). It appeared that the oath of allegiance given in 1756 counted for little.

For the next two decades the VOC was plunged into turmoil, its charter finally lapsing in 1799 when its assets were taken over by the Dutch government. Following the French annexation of Holland, the Netherlands East Indies faced two periods of interim rule by the British, authority only being transferred back to Kupang in 1816.

At some time during the nineteenth century the noble clans of Mangili moved down from Paraingu Mangili to settle on the coastal lowlands at Kaliuda. Although there is no folk memory of when this took place, it is possible that it was earlier rather than later (Twikromo 2008, 57).

According to an 1831 report by the government commissioner E. Francis, immigrants from Savu had established their own kampong on Sumba following a royal marriage alliance between the Raja of Melolo and the Raja of Seba (‘Kupang in 1831’ 1838, 366; Roo 1906, 241). A second colony was established at Kadumbu on the northeast coast of Sumba in 1848 as a result of a marriage alliance between ruling families from the two islands (Wijngaarten 1893, xx; Fox 1977, 164; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 318). It seems these immigrants also arrived with their wives and children (Gronovius 1855, 304). The Raja of Seba seemed willing to provide an ongoing supply of men, either to support the Dutch militarily or to provide reinforcements to the Rajas of Sumba (Fox 1977, 163). Some of the closest ties were between Savu and Raijua and the eastern coastal regions of Mangili and Waijelu (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 318).

These new Savunese immigrants seem to have maintained close relations with the Raja of Sebu. When the new Resident of Timor, Cornelius Sluyter, discovered that none of the signatories from Sumba to the 1756 Paravicini contracts had established the slightest relationship with Kupang or fulfilled any of their commitments, the regents of Savu advised him against forcefully intervening (Roo 1906, 248). They did not want to put at risk the foothold that the Savunese had just established on Sumba. In May 1845 he did negotiate new contracts with a limited number of Rajas on Sumba, but on the east coast these were limited to just Mangili and Kadumbulu (Kapita 1976, 26 and 148).

In 1860 Umbu Mangu was inaugurated as the next Raja of Mangili, a position that he held for ten years. In June of that year, the Resident of Timor, W. L. H. Brocx, came to Sumba and signed a contract with him, as well as with the Rajas of Kambera, Kadumbulu and Taimanu (Kapita 1976, 26). During the same year some 400 Savunese warriors were brought to Sumba to help the Dutch rid the island of a small group of Endenese slave merchants who had established themselves on the island (Roo 1906, 264). After a short campaign that ended in Umalulu most of them returned to Savu.

In the spring of 1863 an American whaler was shipwrecked at Hudu on the coast of Mangili. The crew escaped in lifeboats for fear of being killed by the large number of natives who appeared on the beach and set about looting and burning the ship to recover its copper (Roo 1906, 273).

In 1866 the first Dutch government official was instated on Sumba, controleur Samuel Roos, who had previously been the gezaghebber of Larantuka (Steenbrink 2002, 155). He was located at Kambaniru to the east of the new port of Waingapu and was assisted by H. van Heuckelum and a translator called Baliede who had not only lived on Sumba for some years and was well acquainted with some of the Rajas, but was also married to a daughter of the Raja of Mangili (Kapita 1976, 155; Haripranata 1984, 66-67).

Although Roos visited numerous domains during his three-and-a-half-year stay, he does not seem to have visited Mangili, although presumably Baliede did. Roos did report that Mangili was one of the seven regions where the Endenese were still obtaining their slaves, shipping them on to Ende, Sumbawa and Lombok (Roos 1872, 11). At the same time the slaves from Kambera and the interior were supplied to the coastal domains of Mangili and Waijelu as well as to Kapunduk and Mamboru. He also made a comment that indicated the growing influence of the Savunese. The Raja of Savu owned 100 sheep – an animal that was rare on Sumba – which were kept at Melolo and Mangili (Roos 1872, 26).

A traditional uma mbatangu house in Mangili

Umbu Ngabi Rajamuda became the Raja of Mangili in 1872 following the death of Umbu Mangu two years earlier. Once again the new Raja did not belong to any of the four leading clans – the Maru, Watu Bulu, Matolangu or Wanggi Rara. The Sumbanese rulers remained suspicious about the Dutch. Umbu Ngabi Rajamuda would serve until 1893. (Kapita 1976b, 50).

In 1872 a British iron ship was shipwrecked on the reef at Nusa Manu on the north coast of Mangili and the crew were rescued by local Savunese – J. K. Wijngaarden saw the skeleton of the ship 20 years later (1893, 363). The Raja of Mangili, Umbu Ngabi Rajamuda, arranged for them to be taken to Melolo and on to Waingapu, assisted along the way by Umbu Hiwa, the Raja of Kadumbulu, and Umbu Tubuku, the Raja of Lewa-Kambera (Kapita 1976a, 28-29). In response controleur Roos acquired eight stallions and sixty-four mares as gifts of thanks. Early the following year his new assistant, van der Feltz, was tasked with delivering one stallion and eight mares to the Raja of Mangili in Larahau while the other horses were given to the Raja of Kadumbulu (Kapita 1976a, 29). At the same time silver-topped rottenkoppen canes and Dutch flags were awarded to the Rajas of Mangili and Lewa-Kambera. The Raja of Kadumbulu was excluded from these latter gifts because of thefts from the vessel.

The Nederlandsch Zendelinggenootschap (Dutch Missionary Society) sent its first pastors to neighbouring Savu in 1872 in an attempt to convert the population to Protestantism (Smith Kipp 1990, 102). However the Savunese strongly resisted this alien religion, and the few who did convert were ostracised by the traditional majority. The Dutch saw these pro-Dutch Savunese converts as potential allies and increasingly encouraged them to migrate to Sumba. In 1874 Savunese warriors intervened in the tiny civil war between Mbatakapidu and Kiritana to the south of Waingapu (Kapita 1976b, 31). The following year they assisted the Savunese to crush the Raja of Batakepedu, who was attempting to stop them settling along his coastline (Fox 1977, 172). By 1880 there were already 300 Savunese living in Waingapu (Steenbrink 2002, 151).

In 1889 the Dutch Christian Reformed Church, the ZCGK, sent the missionary Willem Pos to Sumba. He believed the church should be proactive and open schools in the middle of villages to preach the gospel. Based at Melolo, he eventually opened a Christian school at the village of Yalangu in Mangili with a teacher from Ambon and a second from Savu called Titus Djina (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 321; Wellem 2004, 148). The work of the missionaries on Sumba mostly revolved around the Savu immigrant community at that time (Coolsma 1901, 852). The following year the school was destroyed when the Raja of Rindi, Umbu Hina Marumata, plundered and burned the village, taking many captives (Kapita 1976b, 40). The Resident of Kupang demanded responsibility for Rindi’s actions and imposed fines, sending a warship to Rindi and Mangili to ensure that all of the captives were released and the fines paid (Kapita 1976b, 42). Kupang also appealed to the Raja of Timu to send 100 warriors to Sumba, but he failed to do so (Wijngaarden 1893, 368-369).

It was around this time in 1891 that the Dutch anthropologist Herman ten Kate passed through Mangili on his way to Waijelu. Just beyond the Mangili River he briefly stopped at the kampong of Kopa with its seven houses to visit the grave of the Raja of Mangili and his three wives (Ten Kate 1894, 582-583). He was of the opinion that Mangili was at that time without a Raja. He was also confused as to where the domain began or ended.

During the 1890s Kupang organised large migrations from Savu to the north coast, Kambaniru (eastern Waingapu) and Melolo, but this latter group did not really merge with the Sumba people. They established settlements of their own and were exploited by the Dutch to supply warriors to fight against the traditional rulers of Sumba (such as in the Lambanapu war of 1901).

In July 1892 the clergyman J. K. Wijngaarden sailed from Savu to Mangili, choosing the hazardous 30-hour crossing in a fully loaded local prauw instead of taking the KPM steamship to Waingapu by way of Ende. As they approached the shore they were prevented from sailing into the Puru River (Luka Burukulu) by the long offshore reef and for a while became temporarily stranded upon it before making landfall on the beach. The local region was thickly forested, which explained why some Savunese had previously come to Mangili to obtain wooden beams for constructing the church at Seba and the house for the Raja of Seba. Other Savunese even sailed their boats to Sumba to have them repaired. It was said that the two islands belonged together.

Because there was already such a significant Savunese population on Sumba, many Savunese came to Sumba temporarily every year for one to three months during the eastern monsoon, arriving in prauws fully loaded with 40 passengers (Wijngaarden 1893, 353-362). Many stayed on because of the ready supply of water and food and the cooler climate. Those who were sick often came to Sumba to recuperate. As Wijngaarden emphasised (1893, 368):

The Government would gladly see that there were more Sumba settlers, as a counterweight to the Endenese. The Savunese have a certain civilizing influence. Where they settle, the slave trade disappears. The Board promotes emigration as much as possible. Nevertheless, the move has not yet taken place on a large scale.

Wijngaarden travelled on to Melolo where he was welcomed by Willem Pos, who ran the local church and school, which were both attended by the local Savunese community.

As a reprisal for continual horse theft, the Raja of Rindi summoned Umalulu and Mangili to join forces with him in 1895 against their longstanding common enemy, the interior domain of Karera (Kapita 1976b, 39).

The landscape of Sumba around 1895 in a location similar to Mangili

(Photographed by Jean Demenni, Third Infantry, Dutch East Indies Army)

In late 1900 the Raja of Rindi once again struck the village of Yalangu in Mangili and, after looting it, took many prisoners. The attackers burnt the school that had only recently been reopened in 1899 by Reverend Pos and his teacher Titus Djina (Kapita 1976b, 40).

Slowly but surely the Dutch were being sucked into direct intervention. The Raja of Lewa-Kambera, Umbu Biditau, was engaged in a violent conflict with the Raja of Tabundung, supported by Umba Hina Maramata, the Raja of Rindi. When rumours spread in August 1901 that Lewa was about to attack Waingapu, the civiel-gezaghebber sent telegrams to Resident Heekert in Kupang and the Governor of Makassar calling for assistance (Kapita 1976b, 41). The warships Java and Pelikaan responded but the Raja fled into the interior and commenced a long guerrilla war. It was not until 1907 that he was forced to surrender. Meanwhile the Dutch troops moved south to attack Umbu Hina Marumata, who refused to surrender, despite suffering heavy losses. As a compromise he declared his willingness to end the war by paying a fine, to which Resident Heekert acceded.

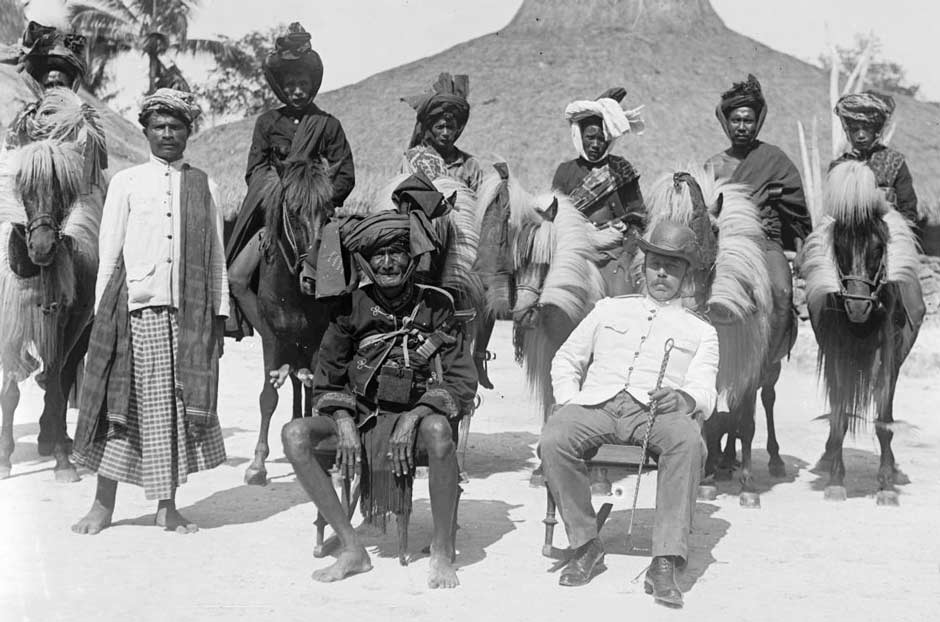

The Raja of Rindi, Umbu Hina Marumata, aged about 65, and Mayor P. J. Spruijt in front of the Raja’s house in Rindi. On the left of the Raja is a Savunese translator. Behind are six Sumbanese on horseback, the horses' necks decorated with tungga (decorative goats' hair). Dated 16 May 1910. G. P. Rouffaer Collection, Leiden University.

In return for their loyalty to the Dutch, the Resident of Kupang issued the Raja of Mangili, Umbu Hina Hungguwali, and the Raja of Waijelu, Umbu Teulu Atakawau, with Deeds of Recognition on the 5th October 1901. These were ratified by a decree seven months later. As a symbol of their authority, each Raja was issued with a gold-topped rottenkoppen and a Dutch flag (Kapita 1976b, 42). Once again the Raja of Mangili had been chosen from the Kanatangu clan, not from the four land-owning Maru, Watu Bulu, Matolangu, and Wanggi Rara clans (Twikromo 2008, 59). His appointment was however endorsed by the Matolangu clan.

The Dutch missionaries opened a second school in Mangili after 1901, which was mainly attended by Savunese children, the Sumbanese being resistant to the concept of education (Twikromo 2008, 90).

Until now the official Dutch colonial policy towards Sumba and the other 'Outer Islands' had been one of non-interference, although this could be suspended if circumstances demanded (Dietrich 1983, 39). These islands were considered incapable of generating a profit for the colonial treasury and it was therefore deemed that they should be ruled at minimum cost. It was sufficient enough for the local rulers to acknowledge Dutch supremacy.

In 1901 the post of the civiel-gezaghebber of Sumba was taken by Captain G. C. A. Dijk, a military officer (Kapita 1976b, 40-41). In April 1902 F. A. Heckler took over as Resident of Kupang and in he 1904 deposed the troublesome Raja of Larantuka. In the same year, Joannes Benedictus van Heutsz was appointed Governor-General of the Netherland East Indies, having previously gained control of the Sultanate of Aceh by means of a highly successful counter-insurgency campaign. This depended on the use of light and flexible detachments of military police (marechaussee), recruited from Ambon and Java. Faced with numerous ongoing local insurrections across the Outer Islands, van Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach with the installation of strong local rule. He initiated a campaign throughout the East Indies, which despite being euphemistically called pacificatie or ‘pacification’ was in certain places brutally violent.

The next Resident of Timor, J. F. A. de Rooy, took over from Heckler in March 1905 and was given clear instructions regarding this much more active policy. The former policy of non-intervention, in which the supreme authority was with the native rulers rather than the colonial authority, was to be abandoned (Steenbrink 2002b, 70). De Rooy’s primary task would be to forcefully implement the new strategy across all the self-ruling districts within the residency. With regard to Sumba, de Rooy did not have to wait long to find a suitable reason to intervene. The Raja of Mamboro, Umbu Karai, soon led a raid against Kodi and on his way through Laura threatened the local Raja, Umbu Lara Lungggi, that on his return he intended to settle an old score. The Raja of Laura appealed for assistance to the civiel-gezaghebber in Waingapu, who immediately alerted his superiors (Wielenga 1949, 30).

In March 1906 27-year-old Lieutenant Cornelis Adrianus Rijnders, the military commander at Kupang was despatched to Sumba, landing at Mamboro with 26 soldiers and 36 armed police (Kapita 1976b, 48-50). We do not have the details of their offensive but according to the Dutch minister Douwe Wielenga, who arrived in Sumba in 1904, they encountered no opposition in the coastal domains, presumably including Mangili, with even the powerful Raja of Rindi submitting without a fight (Wielenga 1949, 30). The real resistance took place in the interior, especially from the Raja of Lewa (Wielenga 1949, 32; Lamster 1945, 165). In 1909 Rijnders turned his attention to the rebellious mountain region of Masu-Karera, which he only subjugated after establishing a military base at Kananggar in Masu (Wielenga 1949, 32). The entire population was eventually disarmed and registered. Instead of installing posthoulders, the military leaders took on the responsibilities of civic officials, with Rijnders taking the position of civiel-gezaghebber in West Sumba in 1907.

After the death of Umbu Hina Hungguwali in 1911, leaderless Mangili was also briefly placed under military rule (Kapita 1976b, 53). In 1912 Rijnders divided the Mangili region in two (Kapita 1976b, 54). Northern Mangili, from the Aumarapu River (Rindi Majangga) to the Kaliongga River, was combined with Rindi kingdom to form the sub-department of Rindi, with Raja Hina Marumata at its head (Kapita 1976b, 54; Forth 1981, 13). Southern Mangili, from the Kaliongga River to the Wula River, was combined with Waijelu.

Umbu Hina Hungguwali had left just one daughter, Rambu Babangu Nona who, after having been widowed, married into another noble clan from Mangili with an appropriate exchange of bridewealth. By customary law she therefore lost her hereditary rights to her father’s land, livestock, heirlooms and power (Kryut 1922, 507; Twikromo 2008, 71). When she then made a move to inherit her father’s position her uncles objected. During the ensuing family dispute, the late Raja’s regalia were returned to the Dutch authorities. It was a major turning point – Mangili no longer had a legitimate Raja at its head.

Umbu Tunga Eta became the acting chief of Mangili until 1916 but did not have the status of Raja.

Lieutenant Rijnders in 1912

Rijnders left the island in 1912 (one report says 1911). Military control was transferred to a civilian administration led by A. J. L. Couvreur, based in Waingapu, initially with the title civilian Controleur of the Afdeeling of Sumba within the Residency of Timor, but later as Assistant Resident (Kapita 1976b, 50). A. J. van der Heyden became the civiel-gezaghebber at Melolo. At the beginning of 1913 Controleur Couvreur divided Sumba into four onderafdeeling, each subdivided into self-governing subdistricts or zelfbesturende landschap of which there were nineteen in total. Each of the latter was headed by a local noble leader or self-governing Raja. In the onderafdeeling of East Sumba there were four: Umalulu, Rindi-Mangili, Waijelu and Masu-Karera (Wellem 2004, 26). Without its own Raja, the whole of Mangili was now merged with Rindi under the leadership of Raja Hina Marumata (Kapita 1976b, 54). It was around this time that the missionary J. F. Colen Burner opened a school at Kanaggar in Mangili.

After this setback Mangili became increasingly regarded as a backwater. Although pacification had made it far easier for the Dutch missionaries to undertake their work, Mangili was not a priority region. The Reverend Douwe Wielenga, who had arrived in 1904, had looked at Mangili as a possibility, given that it was already home to a number of Christian Savunese families and had had a Christian teacher from Savu, Titus Djina. However he had concluded that Mangili was too remote and not appropriately located as a centre to influence the rest of the island (Wellem 2004, 153).

The minister Douwe Klaas Wielenga of the Dutch Reformed Church

In 1916 Mangili gained more formal recognition with the appointment of Umbu Njara Limu Rihiamahu as the Raja Bantu or deputy Raja of landschap Rindi-Mangili. He was the eldest son of the late Raja of Mangili, Umbu Ngabi Rajamuda, and was based in the royal village of Kopa in Mangili while serving alongside Umbu Hina Marumata based in Parai Yawang (Kapita 1976b, 50). In 1919 the younger Umbu Rongga Hambabanju replaced Umbu Njara Limu Rihiamahu, holding that position until 1930.

Umbu Nggala Lili Kani Paraing became the Raja of Rindi-Mangili following the death of Umbu Hina Marumata in 1918. However because of the onset of deafness it was not long before he delegated power to his son, Umbu Hapu Hamba Ndima, who represented him from 1925 until he abdicated in 1932. In that year Umbu Hapu Hamba Ndina, known as Umbu Kandunu, or ‘the one who wears the star’, finally became Raja of Rindi-Mangili, ruling until his death in 1960. In 1928 the religious teacher Ndjurumbatu was posted to the school in Mangili.

From pre-colonial times there had always been a small dam across the river in Mangili, to provide water for irrigating the rice fields. In 1936 the Netherland Indies Government allocated funds for a modern irrigation project based on the construction of a new dam across the Luku Bakulu. The objective was to put an end to the frequent food shortages that occurred in this area during periods of drought. The dam was completed between 1939 and 1940 and led to a significant increase in the acreage under agriculture. It provided an opportunity for Louis Onvlee, an ethnologist working for the Netherlands Bible Society to study the impact the dam would have on the lives of the local people (Onvlee 1949). He was helped in this task by Umbu Hina Kapita, a nobleman and former schoolteacher from the village of Paria Nggangga in Mangili.

Following the completion of the dam, a group of Christian Savunese relocated south from Melolo to Kaliuda in Mangili (Twikromo 2008, 44).

After landing in Waingapu on 14 May 1942, the Japanese military soon penetrated most parts of the island (Kapita 1976b, 66). In Mangili, the Japanese established an army base camp at the royal village of Kopa in Desa Tanamanang and a naval base camp at Laiwila in Desa Kaliuda (Twikromo 1976, 105). It was a time of great repression, with large amounts of livestock and food crops appropriated for the military. Men were forced to work in the fields, to build bomb shelters and serve as unskilled labourers while women were forced to feed the troops. With little food, no shelter and the constant risk of beatings, conscription into the Japanese workforce was tantamount to a death sentence (Kuipers 2003, 177). European missionaries were arrested and later sent to internment camps in South Sulawesi.

After the war the missionaries returned. In 1948 the first Protestant minister, Hapulewa, arrived in Mangili, where he remained until 1970. Because he was not a member of the nobility, the local leaders and their followers generally ignored him.

In 1957, some eight years after the granting of independence, the Sukarno regime introduced a new system of local government, intended to transfer power from the hereditary nobility to government-appointed leaders. Sumba was split into two Kabupaten or regencies, East and West, in 1959 and three years later in 1962 the old system of zelfbesturende landschaps was abolished with East Sumba subdivided into swaprajas or subdistricts, each administered by an official or camat, appointed by the government. At the same time, the swaprajas of Umalulu, Rindi, Mangili and Waijelu were grouped into the new Kecamatan of Pahunga Lodu (literally ‘east day’, meaning where the day begins), with Kabaru as its capital (Kapita 1976b, 155). This turned out to be too large, and in 1964 it was divided into Kecamatan Rindi-Umalulu, composed of the former swaprajas of Rindi and Umalulu, and the smaller Kecamatan Pahunga Lodu, composed of the former swaprajas of Mangili and Waijelu, with Ngalu as its capital (Kapita 1976b, 155). Finally in 1999, Pahunga Lodu was reduced in size again with the separation of the new Kecamatan of Wula Waijelu.

Following Suharto’s coup in 1965 he unleashed a violent anti-communist purge. All citizens would henceforth be required to declare their faith in one of six state-recognised religions specified in a new Presidential Decree: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism or Confucianism (Myengkyo Seo 2013, 56). Those who did not have one of these specified faiths recorded in their national identity card ran the risk of being accused of being a communist and losing their life. After the departure of the missionary Hapulewa in 1970, a maramba from Melolo, Taraandung, became the new minister in Mangili and established good relations with local tribal leaders (Twikromo 2008, 76). Given the political climate, the latter increasingly encouraged their people to convert to Protestantism (Twikromo 2008, 70). Nevertheless in reality many still held on to their traditional marapu beliefs.

A new dam was constructed across the Luku Luanda (sometimes called Luku Kaliuda) close to Ngalu in about 1979, turning the area below the escarpment into an agricultural oasis. It has since become one of Sumba’s major rice-producing regions. Yet even with the dam there was a bad drought in 1995 that caused crop failures and severe food shortages (News and Views Indonesia 1996, vol. 9, issue 90, 11).

The royal hamlet of Kopa, Desa Tanamanang

Today the descendants of the Mangili royal family still reside in Kopa, just north of the Luka Luanda, and have farms in the nearby rural location of Larahau. The current head of the royal family is Umbu Hina Ratu Wula who resides in Larahau.

One of Mangili’s finest sons was Umbu Hina Kapita, a maramba from Maru clan, who was born on 31 December 1908 at Paria Nggangga in modern Desa Tanamanang. From 1928 until 1950 he worked as the translator and research assistant to the Dutch scholar Louis Onvlee, later becoming a prolific publisher of his own work. He died on 21 December 2002, and was buried 21 days later.

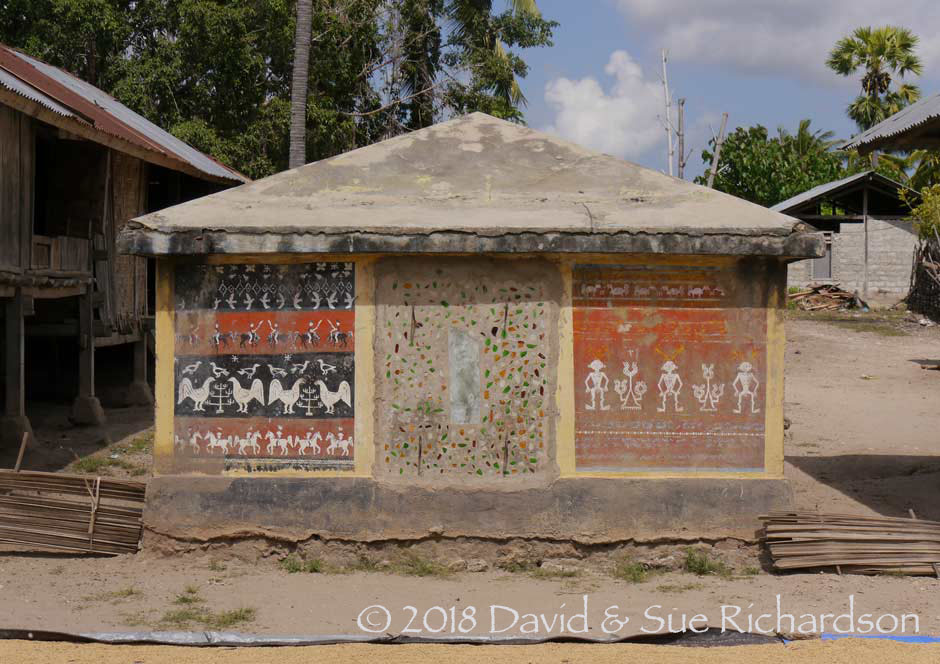

The grave of two former kepala desas of Kaliuda decorated with inggi motifs. Umbu Mangu Abi aka Umbu Djangga, a leader of the Matolangu Uma Kaluki lineage, died on 2 September 2007 and was buried on 3 November 2007. His father was Umbu Nggaba Maramba Amah.

Today there is no politically defined region called Mangili. Pahunga Lodu is divided into eight Desa or villages, namely Kuruwaki, Pamburu, Kaliuda, Tanamanang, Tamma, Lambakara, Mburukulu and Palanggai. Its administrative centre is Tandening in Desa Kaliuda.

Return to Top

The Former Rajas of Mangili

| Rajas of Mangili |

| Umbu Lakaru Taraandungu (1750 to 1775) |

| Umbu Mangu (1860-1870) |

| Umbu Ngabi Rajamuda (1872 to 1893) |

| Umbu Koparihi (??) |

| Umbu Lapu Karahanjara (??) |

| Umbu Hina Hungguwali (1901-1911) |

| Acting Chief of Mangili |

| Umbu Tunga Eta (??-1916) |

| Raja Bantu of Mangili within Rindi-Mangili |

| Umbu Limu Rihiamahu aka Umbuna i Pura (1916-1919) (the son of the brother of Umba Ngabi Rajamuda) |

| Umbu Rongga Hambabanju (1919-1930) |

Return to Top

Ethnography

The people of Mangili are divided into patrilineal kinship groups called kabisu, which are exogamous. As already mentioned, Mangili is currently controlled by four dominant clans – the Maru, Watu Bulu, Matolangu and Wanggi Rara, the latter being one of the original indigenous clans, the other three being later arrivals. These four clans are collectively known as the mangu tanangu or lords of the land (Onvlee 1949, 447).

One additional clan, the Kanatangu, arrived later but has been the source of the domain’s line of Rajas. These clans are divided into houses or uma (Twikromo 2008, 58).

Inggi motifs painted on the side of a tomb at Kaliuda

As elsewhere in East Sumba, the people of Mangili are strictly divided by caste. In the village of Kaliuda, for example, about 60% of the population are ata or slaves, 10% are tau kabisu or commoners and 30% are the maramba or nobility (Twikromo 2008, 52).

The relationships between the kabisu clans are governed by an asymmetric system of marriage alliance in which bride-givers have a higher status than bride-takers (Onvlee 1949, 152; Forth 1983, 654). The predominant position of the Matolangu clan rests on its position as the bride-giver in marriage affiliations with several other clans in Mangili. However the Matolangu and the Kanatangu clans have an especially close relationship that underpins their control of much of the land, with the Kanatangu clan taking its brides exclusively from the Matolangu clan (Twikromo 2008, 58).

There are also longer-distance alliances, with the people of Mangili supplying brides to the people of Paliti (Napu) and the Tabundung people supplying brides to Mangili and Waijelu (Kapita 1976a, 25).

Louis Onvlee explained how in East Sumba the bride-takers were obliged to gift bridewealth, banda, which literally means cattle but more generally means wealth (possibly from the Sanskrit word benda, meaning inanimate object or wealth). It has two components: banda luri, livestock, especially horses but also buffalo and pigs, and banda àmahu, golden ornaments, especially mamuli pendants and occasionally plaited and unplaited chains (1949, 452-453; 1980, 157). The latter include kanatar gold chains, haluku lulungu plaited chains of gold or silver and lulu amahu plaited copper chains - all of which represent the male genitals and symbolise male sexuality (Twikromo 2008, 47).

In return the bride-givers made a counter-prestation known as kamba, literally cotton, in other words hand-woven textiles, which might also include beadwork (and shellwork), especially for the marriage of a rich man’s daughter. Ideally the number of items should be eight, in which case the gifts were referred to as banda matoma and kamba matoma (matoma meaning fulfil). There is also a preference to have items paired by gender. For example, mamuli should always be given in pairs – an unadorned female pendant matched with a decorated male pendant, while each male textile should be matched by a female textile. Likewise a paired stallion and mare must accompany a bridewealth gift composed of four mamuli. This in turn must be matched by a counter-prestation of four textiles: a man’s blanket matched by a woman’s tubeskirt and a male torso wrapper (rohu banggi) matched by a female head-cloth.

Such gifts should also be commensurate in quality and status to those who are making the gift. Yohanes Twikromo observed how Umbu Amahu and Umbu Mana were heavily criticised for donating second-best rather than highest quality hand-woven cloth during the inauguration ceremony for the new kepala desa of Kaliuda (a close relative) in November 2002 (2008, 66). By doing so they brought shame onto themselves.

Return to Top

The Anthropology of the Native Mangili Dam

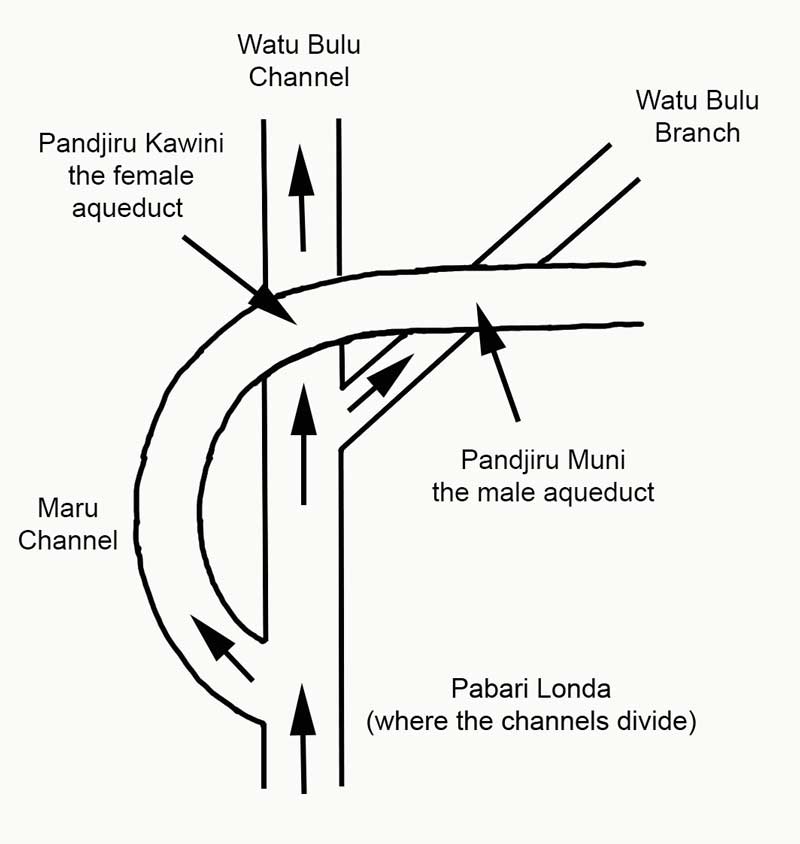

When the Dutch began constructing the first Mangili dam in 1939 it provided an opportunity for Louis Onvlee and his translator Umbu Hina Kapita to study the native system of dams and irrigation channels. Their conclusions were neatly summarised by Josselin de Jong, whose comments are broadly reproduced below (1980, 249-250):

Water was taken from the principal river through an irrigation channel, which at a certain point bifurcated into two wooden conduits, each leading to the rice fields of one of the principal exogamous patrilineal clans of the district – the Maru and the Watu Bulu. The higher, upstream, conduit that led to the Watu Bulu fields was considered male while the downstream conduit that led to the Maru fields was considered female. In poetic speech, the rice fields and conduits were likened to gold ear pendants and the chains attached to them. The pendants and the rice fields are considered female, the chains and the conduits male. The rain which fertilises the fields is called wai palinju awangu, heavenly sperm (Onvlee 1977, 159).

The female conduit did not lead directly to the rice fields but was laid out in such a way that it twice crossed the male conduit by means of an aqueduct. At these places the male and female conduits were said to live together as husband and wife.

The conduits were made of wood, which needed to be renewed from time to time. If the ‘female’ conduit needed repair, the clan to which it belonged had to send emissaries to the other clan to ask for suitable logs. This was done with the same formalities as were employed when the bride-taking clan approached its regular bride-giving clan to request a wife for one of its clansmen. Even the same gifts were exchanged. At the first negotiations, the wife-receivers gave gold ornaments and a horse and took a cloth in return. Later, when a party of woodcutters of the first clan (Maru) entered the territory of the other to fell the tree for their conduit, they gave a stallion and a mare and received four more cloths. Finally, when the log was carried into Maru territory, the party that fetched the log, and which was still regarded as bride-takers, gave ornaments and a horse, while the Watu Bulu responded with two more cloths, ‘to accompany the bride on her journey’. The parallel between Maru, the receivers of the log, and Maru, the wife-taking clan, is carried even further. The two places where the male and the female conduits crossed each other, i.e. where they ‘married’, could not be seen by members of the clan that had a wife-taking relationship with the Maru.

If a man from this third clan unavoidably had to approach these taboo places, he had to veil his face in passing. This was in accordance with the avoidance a man had to practise toward his wife's brother’s wife - and to a member of this third clan, the log from Watu Bulu stood in this position.

Return to Top

Sumbanese Textile Terminology

While there are seven recognised languages in West Sumba, most of East Sumba is united by the single language of Kambera (Grimes, Grimes, Therik and Jacob 1997, 67). However there are several different dialects of Kambera – Mangili and Waijelu have a distinct common dialect that is different from that spoken in Rindi and Umalulu (Forth 1981, 17).

Douwe Wielenga was one of the first scholars to produce a comparative glossary of the different dialects of Sumbanese words. For the Dutch word slimoet, meaning blanket, he provided the following comparisons (Wielenga 1914, 38):

| Region | Term |

| Kambera | hinggi |

| Mangili | inggi |

| Laura, Wadjewa and Lauli | ingi |

| Ana Kala and Wanokaka | régi |

| Lewa and Tarimbang | rénggi |

| Kanatang, Napu, Palamedo | rénggoe |

| Mamboro | singgi |

| Lamboya | singi |

| Kodi | hânggi |

| Tabundung, Karera, Tawoei | waroe |

Today the term inggi is used in both Mangili and Waijelu, whereas hinggi is used further north in Rindi and Kambera.

Return to Top

Cotton Cultivation in Mangili

Cotton once thrived along the coast of Mangili. Samuel Roos, who served as the first Dutch cyear stayontroleur on Sumba from 1866 to 1873, reported that the island’s soil was very suitable for cotton culture and that the cotton produced was of a superior quality. Cotton seeds were planted at the start of the rainy season in the last days of November or the first days of December (Roos 1872, 24). The plants first appeared during the middle of the west monsoon and from June onwards the raw cotton was picked continuously. In November the plants were cut down to the ground to prevent infestation by caterpillars.

However when the Dutch naturalist Karel Dammerman visited in 1925 he discovered that, despite having been cultivated widely in the past, the planting of cotton had almost disappeared (Dammerman 1926, 65). The Dutch civil servant/ethnologist Christiaan Nooteboom, who spent over one-and-a-half years in East Sumba in the mid-1930s, reported that cotton previously grew in the whole east coast region but, by the time of his stay, its cultivation had almost disappeared (Nooteboom 1940, 86). Spinning wheels were no longer used to spin raw cotton but to reel factory-made yarn instead.

An elderly man in Kaliuda winding a ball from a hank of commercial cotton using a simple swift or pepang

Today the majority of weavers use commercial two-ply machine-spun cotton, as they have done for the past half-century. However a few women still drop-spin, using cotton that they still grow in their gardens from seed.

A new inggi woven from local hand-spun cotton, Kaliuda, 2018

The region still remains ideal for cotton cultivation. In 2008/09 the Sumba Plantation Office established two demonstration plots for cotton cultivation in Desa Tanamanang, each managed by a local group of farmers. In 2012/13 two further groups of farmers were given plots in the same area (Nugrohowardhani et al 2015). These projects are part of a major NTT development programme called ‘The Cotton Belt of Indonesia’, which aims to turn Sumba back into a leading producer of cotton and at the same time improve local employment and household incomes. Farmers are supplied with cotton seed and fertiliser and must sell their cotton back to a private company, PT Ade Agro Industry (AAI), a subsidiary of PT Adetex in Bandung, at prices set by the government. Some farmers gain additional benefit by using the fertiliser on their rice fields and allowing their wives to spin some of the raw cotton for use in weaving.

Meanwhile PT Ade Agro Industry has established its own commercial cotton plantation at Lawila in Mangili (Vel and Nugrohowardhani 2012, 40; Vel and Makambombu 2013). They grow modern American G. hirsutum varieties using a system of centre-pivot irrigation, harvesting both seed and cotton fibre.

Return to Top

Warping Up and Binding

It is normal for the warps to be wound on a rectangular warping frame, raised from the ground on short legs. Two lateral cords are tied across the narrowest part of the frame, positioned towards one end of the frame and about 15-20cm apart. Two people sit side by side inside the frame, each holding a ball of yarn in a half coconut shell. They pass the yarns back and forth from hand to hand, around the frame to create a continuous warp, with an upper layer of warps on the top of the frame and a lower layer just below it. As they form the upper layer they pass the balls alternatively over and under the lateral cords to form the cross.

Two girls working in coordination to warp up yarns for a lau hiamba at Laiwila in Mangili. The two white transverse strings are used to make the cross. The red and green yarns divide the yarns into bundles of six

Sometimes the yarns are gathered into bundles at the same time, using coloured yarns to separate each bundle from its neighbours. Each bundle forms the basic element of the resist dyeing process. The finest cloths are made from bundles of six yarns, but it is possible to use eight or ten. To keep the bundles aligned side by side, the upper layer of warps are locked in place by binding them together transversely with a cord.

In the past the bundles of yarn were bound with strips of gebang palm leaf (Cabbage Palm) but today most binders use Chinese plastic straw twine, especially blue and green. In the image below, the binder is using green to protect the areas that will remain white, and blue for the areas that will be untied after the indigo dyeing stage so that they can be dyed morinda red. The areas that are unbound will be dyed with indigo followed by morinda, resulting in a dark purple.

Binding yarn bundles in Kaliuda with plastic straw twine

However there is no standardisation. Her neighbour, below, is using blue to cover the areas that will stay white and green for those areas to be dyed red.

Untying the green knots after the completion of indigo dyeing

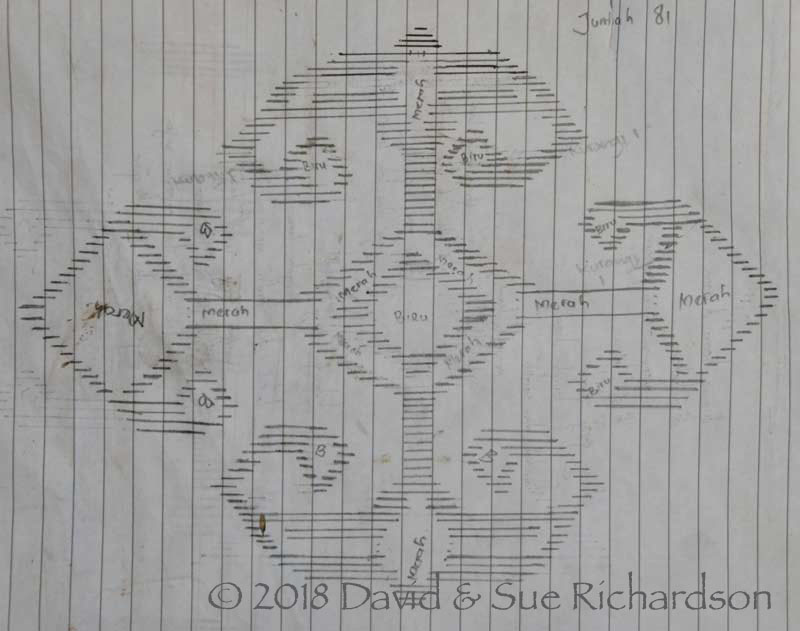

Motifs are normally tied from memory but, to help inexperienced binders, some patterns have recently been recorded on paper.

Pattern for binding warp bundles with a habak motif,

highlighting the areas to be dyed blue and red

Return to Top

Natural Dyeing in Mangili

The inggi of Mangili have long been renowned for their deeply saturated colours. According to Monnie Adams (1972, 16):

Locally, Mangili style is considered the finest because of the use of deeply saturated colours, for bright red and rich black replace the familiar rust and purplish tones. The strong colours result from local variations in mixing dyes made from mengkudu and indigo, longer pre-dye preparation of the yarn (for brightness) and, of course, repeated dye baths. It is claimed that a good pair [of inggi] requires at least five years work. In placing highest value on colours, the Sumbanese are employing a traditional yardstick of judgment for the Mangili cloths. The subject matter is conservative, roosters and the horsemen, who are often shown engaged in ceremonial dancing.

Jill Forshee (1996, 62; 2001, 36) added the following:

Some areas, such as the central and southern coastal regions, produce cloth with high contrasts between deep, blue-black indigo grounds and motifs in white. The southern coastal area of Kaliuda employs a strikingly bright red, achieved through long immersions in kombu dye, using a mordant called loba (candlenut; Aleuritas moluccana) to intensify the colour.

This is of course how all morinda is dyed throughout East Sumba, using a two-stage process involving oiling with candlenut (which is called kemiri not loba) and mordanting with aluminium derived from loba, the dried leaf and bark of trees belonging to the species Symplocos, an aluminium hyper-accumulator.

We too have wondered for many years why the inggi of Mangili are so different from the hinggi of Rindi and Kambera, especially as regards to their strong red and black colouring. This cannot be for the reasons proposed by Adams and Forshee. At one stage we worried that they might be boosting the red of their morinda through the addition of an alizarin-based synthetic dye. Yet we have so far never encountered chemical dyeing in this region – all of the textiles continue to be exclusively naturally dyed.

More recently we wondered if the deep colours were because of the presence of many immigrant communities from Savu and Raijua. For example, Kaliuda had 2,960 inhabitants a decade ago, 56% of whom were Sumbanese and 42% were Savunese (Twikromo 2008, 38). Although immigrants from Savu were first recorded arriving in the region at some time prior to 1831, small numbers had been sailing to Rindi, Mangili and Waijelu long before the colonial era, attracted by its watercourses and fertile land, or else having been expelled for misconduct (Noteboom 1940, 7).

Traditionally many Savunese women were masters at dyeing indigo and morinda, capable of achieving deep blues and morinda reds as well as black. Indeed, according to the oral traditions of the people of Kodi in West Sumba, the occult techniques of indigo dyeing and metalworking were brought to the island from Savu. People of Savunese descent still specialise in indigo dyeing in that region today (Hoskins 1993, 52; Hoskins 2013, 148). On Sumba Island, it has been reported that some Savunese merchants specialise in selling raw materials for dyes (Cunningham, Ingram, Kadati et al 2011, 18).

To explore the possibility of Savunese involvement we visited Mangili again in May 2018 but were told by weaver after weaver that the Savunese community play no part whatsoever in the production of local textiles. The Savunese lead quite separate lives relying not only on their rice plantations but also on their jobs as schoolteachers, religious teachers, and government employees (Hambarandi 1982, 41; Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 318).

We were told that the reason that the morinda of Mangili is so red is because of the local ecology – a result of the local soil conditions, landscape and possibly climate. It is the same phenomena that the French call terroir – the way that a particular region's terrain, soil and climate affects the taste of its wine. We already knew that the quality of morinda root dye depended on the location of the tree – dyers generally avoid trees growing close to the coast or to a water source, preferring trees that grow at higher elevations.

Dyers in Mangili believe that there is something special about their local morinda. Indeed they cannot reproduce the same deep red if they use morinda from another region, such as Kambera or West Sumba.

We were also informed by an expert from the Kambera area that there were a few morinda trees in that locality which gave a red similar to the red from Mangili.

In Mangili morinda grows in two main locations – along the coastal plain or up in the hills at higher elevations. Dyers claim that there is no difference between them regarding the quality of dye obtained. To our eye the local morinda root has a different appearance to that from Kambera or Rindi, being not orange but a deep chocolate brown.

Dried morinda roots harvested in Mangili

Both indigo and morinda thrive on the dry coastal plains of Mangili. At the end of the rainy season, the roadside verges in Mangili are filled with dense clumps of indigo up to 2-metres in height. Indigo dyeing mostly takes place towards the end of the wet season and in the early months of the dry season, when the indigo is at its best.

Freshly cut indigo being left to wilt at a house in Laiwila

As elsewhere in East Sumba, the dyeing of indigo is the responsibility of local specialists. After allowing the indigo leaves to wilt for half a day they are immersed in water and mixed with ash water or lime powder. The mix is allowed to ferment for a few days, the leaves and stems are squeezed out and removed and the bound threads can then be immersed in the dye pot. They are left for one or two nights before being hung up to dry. The cycle is repeated numerous times until the required depth of blue is achieved.

A bound indigo-dyed warp set drying in the sun

Woman brushing the indigo-dyed bundles to remove the excess indigo powder

In Mangili, as with indigo, only certain families are involved in dyeing morinda. The indigo-dyed yarns are first oiled in ash water mixed with crushed candlenut (kemiri) and dried dedap bark (Erythrina sps). They must then be allowed to thoroughly dry. The candlenut is imported from West Sumba.

Candlenut-oiled indigo-dyed yarns drying

Cotton warps drying on a nobleman’s grave

After harvesting, the morinda root is allowed to dry for several days in the shade. Bark is stripped from the large roots although the small roots can be processed whole. The bark is pulped in a wooden mortar with a small amount of water, normally two women work in unison to pound the mix. After pounding the ball of crushed root is removed and thoroughly squeezed out in a plastic bowl. The crushed root is returned to the mortar and pounded again. This continues until the root has been pounded and squeezed seven times. At the very end they recycle the morinda one last time in a small bucket of water to extract every last bit of dye.

A long days work ahead. Pounding morinda root is a hard laborious process

A whole family work together to prepare morinda dye in Kaliuda

Once all of the morindin has been extracted from the morinda root it is time to add the aluminium-rich loba, the powdered leaf and bark of Symplocos, although this can also be added to the morinda root in the mortar. Loba does not grow in Mangili and is today obtained from West Sumba, although Kapita noted in 1976 that it was sourced from the Masu highlands (1976a, 232). Dyers in Mangili do not add ash water or lime powder to the morinda dye bath.

The indigo-dyed bundles of yarn are immersed in the morinda dye bath and are kneaded and squeezed before being left to steep for several days. They are then taken out to dry, after which they are immersed in a fresh dye bath, a process that is repeated five or six times until the desired depth of red is obtained.

After dyeing with morinda, the yarns that were initially dyed with indigo become dark purple bordering on black

A complete indigo- and morinda-dyed warp set drying in the sun

Once the morinda-dyeing stage is complete the bound warps are stretched onto a frame and roughly aligned. The bindings are cut and the pattern is carefully focussed and locked in place through stitching or by binding them to a lath.

Above: Ikatted warps aligned on a bamboo frame for a final drying in the sun

Below: Two aligned sets of warps stretched on a frame in Kaliuda

(Photographed in 1987 by Dr Pienke W.H. Kal, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam)

Return to Top

The Mangili Back-Tension Loom

The body tension ground loom used in Mangili is identical to that used elsewhere in East Sumba. It uses a continuous warp and is set up so that it is slightly inclined from the horizontal. Each panel of the inggi is woven separately.

Weaving at a typical loom on the veranda of a house in Kaliuda

A simple loom set up to weave one half of an inggi at Laiwila

A young girl winding her mother's shuttle with morinda-dyed yarn

Above and below: a weaver in Kaliuda photographed in 1987 by Dr Pienke W. H. Kal from the Royal Tropical Institute (Tropenmuseum), Amsterdam

Return to Top

Mangili Textile Motifs

Sylvia Fraser-Lu claimed that weavers in Mangili only began producing textiles with simple compositions based on the realistic depictions of horsemen and roosters in the 1960s (1988, 199). This is not true – several examples in our collection were woven just after the end of the Second World War. Because of this we suspect that identical designs must have been produced pre-1940. The problem is that it is hard to find Mangili textiles with an earlier provenance.

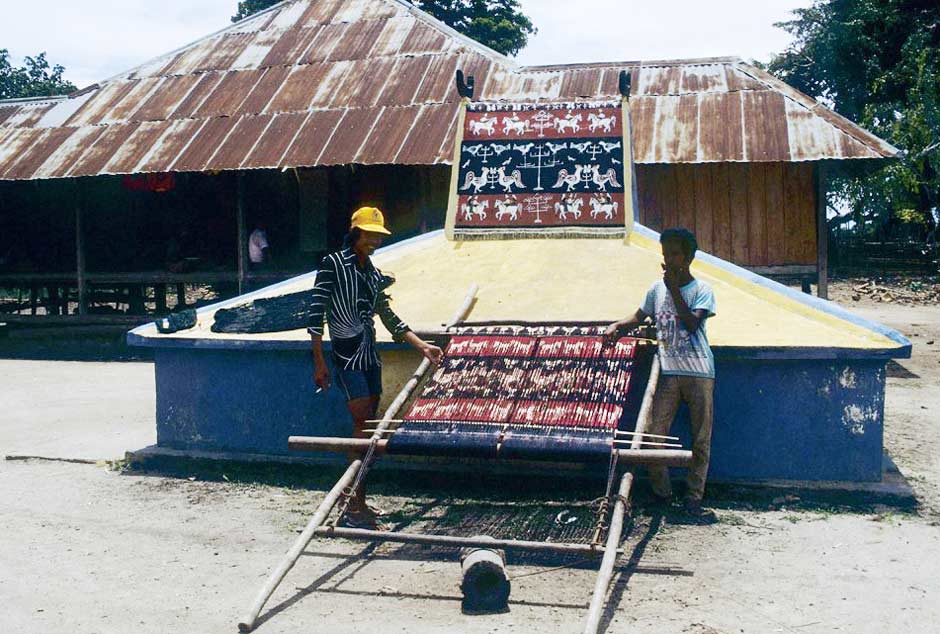

Local weavers have told us that each weaving village has a different repertoire of motifs. Motifs are a vital expression of local identity and culture and, in addition to appearing on textiles, are widely reproduced on houses, village entrances and graves.

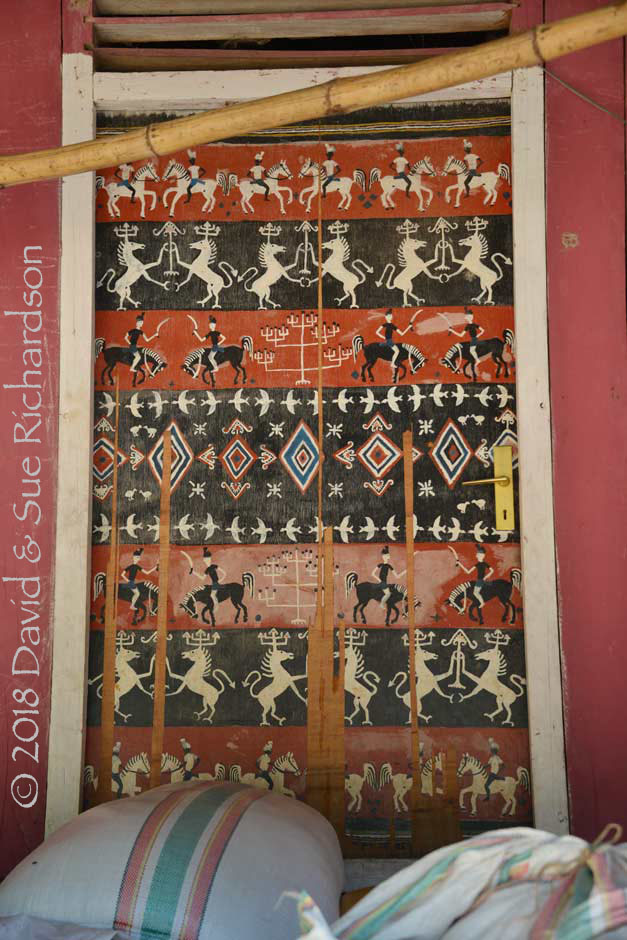

A house in Kaliuda with a door painted with textile motifs

The central band of an inggi is frequently decorated with a row of mata huta diamond motifs, flanked by rows of six-pointed stars, locally called kandulu but in Kambera kandunu. According to Warming and Gaworski, the central band composed of diamonds and six-pointed stars was once a speciality of the Mangili region, but is now also found elsewhere (1981, 82-83). We, on the other hand, have never seen this pattern on a single non-Mangili cloth.

The most prominent Mangili weaving motif is the horse or njara, which symbolises wealth, prestige, mobility and male bravado. In earlier times horses were the prerogative of the nobility and, as elsewhere on Sumba, are still sacrificed at their funerals to accompany their souls to the afterlife. Thanks to the business acumen of Gronovius, the prosperity of the nobility was enhanced greatly from the mid-nineteenth century onwards on the back of the exportation of horses. Yet Adams found that horses were rarely depicted on cloths held in early Sumba collections, which of course mainly represented cloths from Kambera and Rindi (1969, 136). We lack the evidence to say whether this was also the case with regard to Mangili inggis. It is possible that, over time, the export trade stimulated the increasing use of horse motifs - certainly in Kambera and Rindi weavings (Adams 1972, 16).

Bridled horses ridden by noblemen wearing kambala headdresses with upstanding ends

One reason that horses may be more commonly depicted on Mangili (and Rindi) fabrics is because the central east coast landscape provides an ideal breeding ground. In general horse density across East Sumba varied from 4 to 9 per square kilometre after the Second World War and there were 350-550 horses per 1,000 inhabitants. However in Rindi-Mangili there were over 13 horses per square kilometre and 1,450 horses per 1,000 inhabitants (Hoekstra 1948, 132).

Indeed some local people believe that souls are carried to heaven upon the back of a mythical, winged horse known as a njara ninggu rukappang (Breguet 2006, 213).

Statue of a horse on a grave in Kaliuda

Chickens (manu) are a common motif throughout East Sumba, symbolising protective, ancestral power. They are important in augury, as people seek information through their entrails from the higher powers of Marapu ancestors. Cocks wield vigilant power, poised atop homes, graves, or looming in upper design fields of fabrics, heralding the arrivals of that yet unseen by humans.

The Pacific Black Duck or Pasifik rende miting (Anas superciliosa) is sometimes depicted in noble cloths. The reason is because its behaviour. If the female duck is attacked with her ducklings she comes forward and pretends she has a broken wing, attracting the predator and allowing the ducklings to escape. A good leader must be similar, protecting his people and facing up to his enemy at the head of his warriors.

The depiction of crayfish (kurangu), shrimps and fish (iyang) seems to be less common in Mangili cloths than in those from Kambera and Rindi.

Another common motif is the harama dance, performed by men and women in traditional dress. Today they are staged to welcome important guests, such as government or religious officials, to the village. In the past the ninggu harama war dance was conducted to welcome back warriors who had just returned from the battlefield. It was performed in front of the warriors who were armed with their shields, parangs and spears by the elderly women, celebrating their prowess and bravery.

Women draped with inggi dancing the ninggu harama to welcome home their victorious warriors

Return to Top

The Textiles of Mangili

Textiles from Mangili are poorly represented in early collections of Sumba cloth. Unsurprisingly none exist in the small early 1891 collection of hinggi held in Leiden. More importantly we cannot identify a single Mangili cloth among the 71 men’s blankets held in the Wereldmuseum, Rotterdam. These were collected by the missionary Douwe Wielenga, who was based at Kambaniru and later Payeti (both close to Waingapu) between 1904 and 1921. None are illustrated in the 1927 review of the collection that Nieuwenkamp acquired on Sumba in 1919. Furthermore we can only identify a single example in the collection of 81 hinggis listed by the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

A rather poor inggi from Mangili acquired by the Tropenmuseum in 1973

More recently not a single Mangili cloth is illustrated in Decorative Arts of Sumba published in 1999.

There are also very few Mangili cloths in major museum or private collections. The few that are held have been acquired from dealers and auctions rather than collected at source. There is no record of when and where they were made or the clan that they belonged to.

A simple Mangili inggi with no provenance

(Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven)

Today the weavers of Mangili classify their blankets into three types:

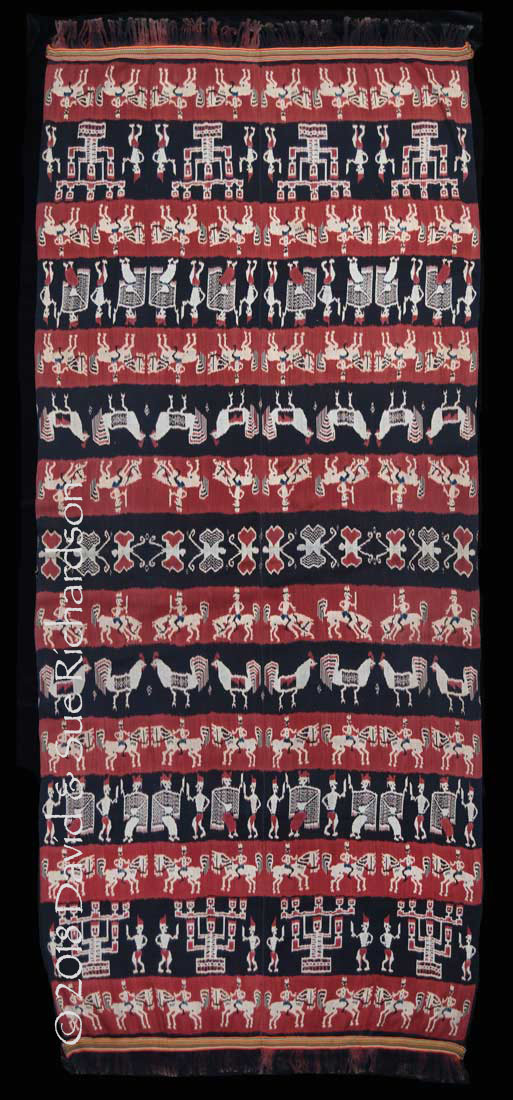

- inggi kombu rara have alternating red and black bands,

- inggi kombu kambata bara contain white bands (kambata bara) in addition to red and black, while

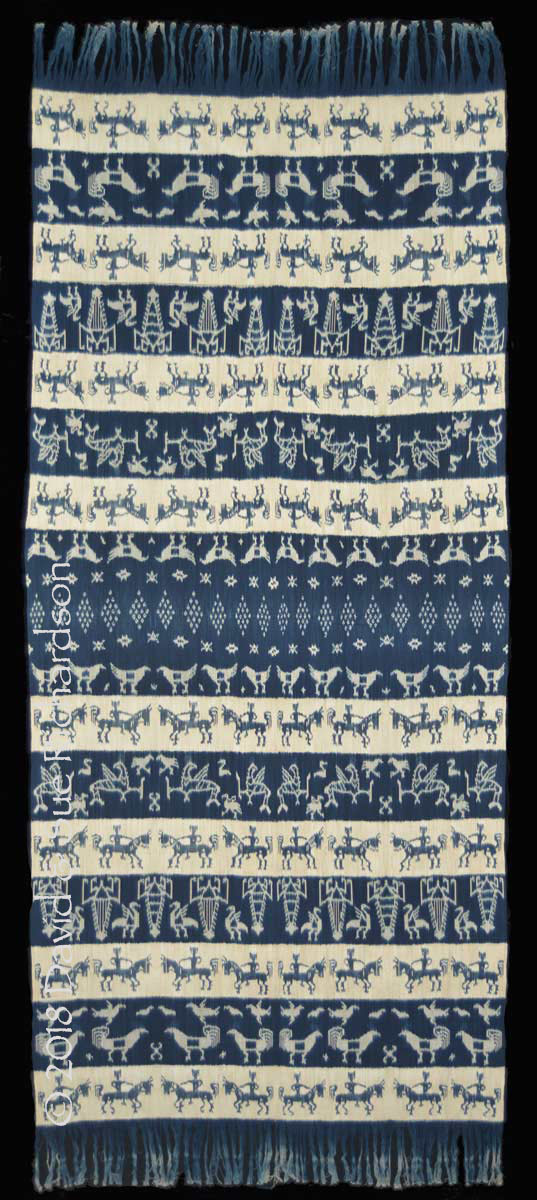

- inggi kaworu kambata bara have just indigo blue and white bands.

The term kambata refers to a fragment, piece or slice, and is derived from mbata, meaning to break or broken (Forth 1980, 53).

Return to Top

The Richardson Collection

We strive wherever possible to collect textiles in the field. This is the only way to know when and where a textile was made, who made it, for what purpose and how it has been subsequently used. Textiles without provenance have little value to the textile historian.

Unfortunately it is hard to find top quality Mangili weavings, so our own collection of these cloths is limited – confined to eight inggi kombu rara and one inggi kaworu kambata bara. Because the finest inggi were used in gift exchanges, especially those that underpinned the marriage alliances between the highest-status clans, these have been mostly collected from members of the Mangili nobility.

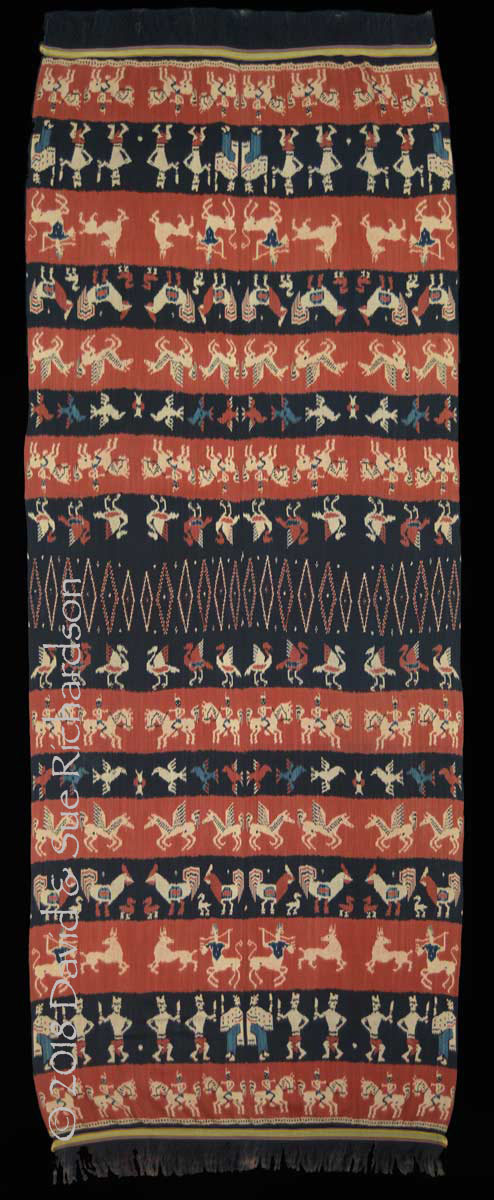

Disappointingly the first inggi in our collection has no provenance other than the fact it was acquired in Singapore in the early 1970s, meaning that it must be at least 45-years-old. It is unusual in that the horse and rider motifs in the morinda bands are aligned in a row but the cockerels, crayfish, harama dancers and skull trees (andung) in the black bands are not.

Inggi kombu rara acquired in Singapore in the early 1970s. No provenance

Richardson Collection

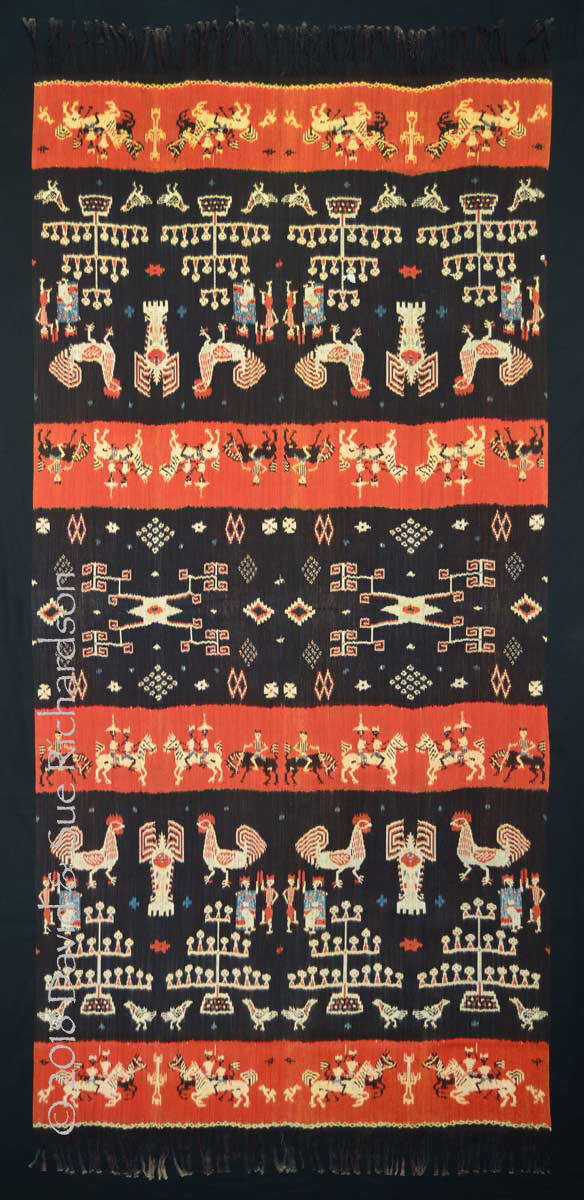

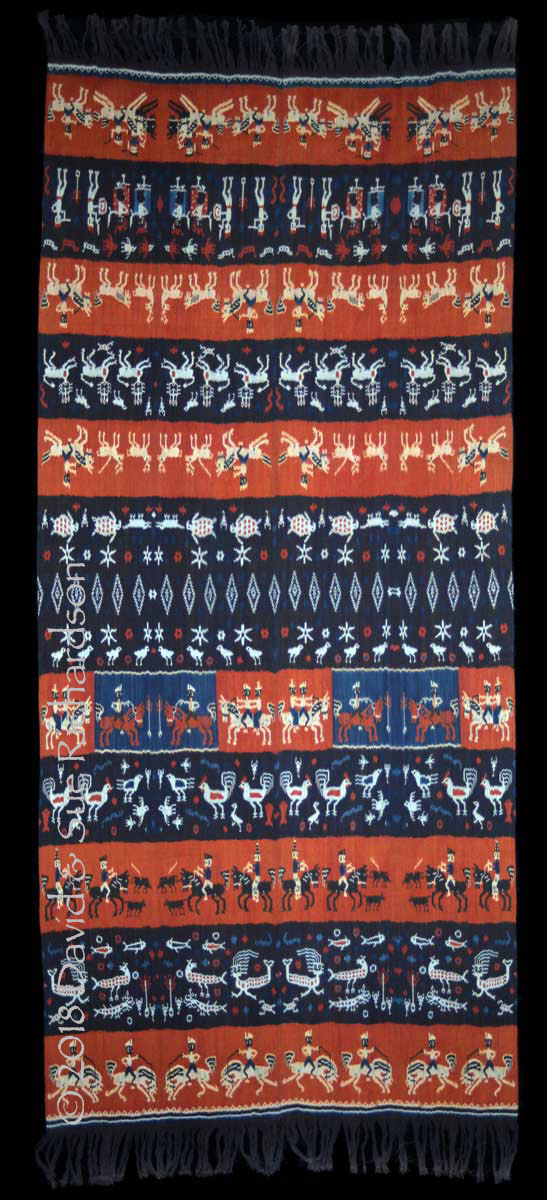

The second inggi was woven on the outskirts of Kaliuda in 1975 by a weaver belonging to a Christian family currently headed by Ahmad Kalawai, a wealthy maramba who is closely linked to the Mangili royal family. Many years ago he converted from Christianity to Islam. The weavers in his family have the reputation of being the best in Kaliuda, which may explain the exceptional depth of colour in this example. The inggi is decorated with uma kabihu (clan houses) flanked by ratu with sacrificial cockerels as well as pairs of fighting cockerels and their owners.

An inggi kombu rara woven in 1975 on the outskirts of Kaliuda by a noblewoman from the family now headed by Ahmad Kalawai. Richardson Collection

The third inggi was acquired from the highly respected Kapita family who informed us that it is well over 70 years old so was probably made before the 1942 Japanese invasion. They inherited it from their father, Umbu Haramburu Kapita, a maramba from the leading Maru clan. Born in 1934, he attended a Dutch high school in Waingapu between 1950 and 1955 before studying medicine in Surabaya. After becoming a member of Golkar he served two terms as the fourth Regent or bupati of East Sumba from 1967 until 1978. He died in 1996 leaving behind seven children.

Umbu Haramburu Kapita inherited the inggi from his famous father, Umbu Hina Kapita, a Mangili nobleman who became an important anthropologist. Born in 1908 in Paria Nggangga, Mangili, he was sent to Holland to study theology, and on his return to Sumba became a teacher. Between 1929 and 1955 he worked as the translator and research assistant to Professor Louis Onvlee, a missionary, Bible translator and cultural anthropologist who had earlier obtained a doctorate in Sumbanese from Leiden University in 1925. Umbu Hina Kapita later became a prolific writer and ethnographer in his own right, publishing two crucially important books on the history and culture of Sumba in 1976. He died at the age of 94 in 2002.

An inggi kombu rara that formerly belonged to the Mangili nobleman Umbu Haramburu Kapita and his father Umbu Hina Kapita. It is decorated with crayfish, fish and sword-wielding lions. Richardson Collection

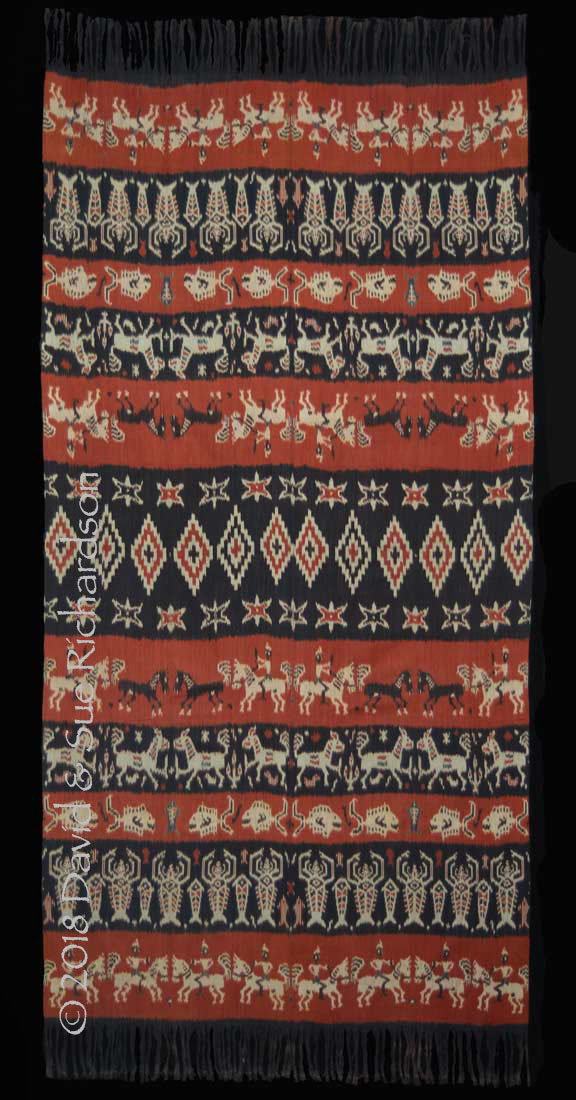

The fourth inggi in our collection was formerly owned by Umbu Pura Woha, a Mangili nobleman who was born in Wualanda village on 22 October 1936. It was woven in 1947 by his mother at the village of Lambakara, Mangili, located on the main Waingapu road about 15 minutes north of Kaliuda. She was a maramba belonging to the Mangili royal family.

Umbu Pura Woha spent his career in agriculture, becoming the Head of the Agricultural Service of East Sumba Regency in 1966. After relocating to Kupang he became Deputy Head of the NTT Plantation Office in 1971, Head of the NTT Provincial Plantation Office in 1974 and finally the Head of the Department of Agriculture, Food Crops and Horticulture for NTT Province in 1994. He has five children. Since his retirement in 1996 he has written two books on the History, Deliberation and Customs of East Sumba and the History of Government on Sumba Island. He is currently compiling a collection of Sumba folk and fairy tales.

An inggi kombu rara woven by the mother of Umbu Pura Woha in Lambakara, Mangili, in 1947. It is decorated with Pacific Black Ducks, winged horses and spear-throwing centaurs. Richardson Collection

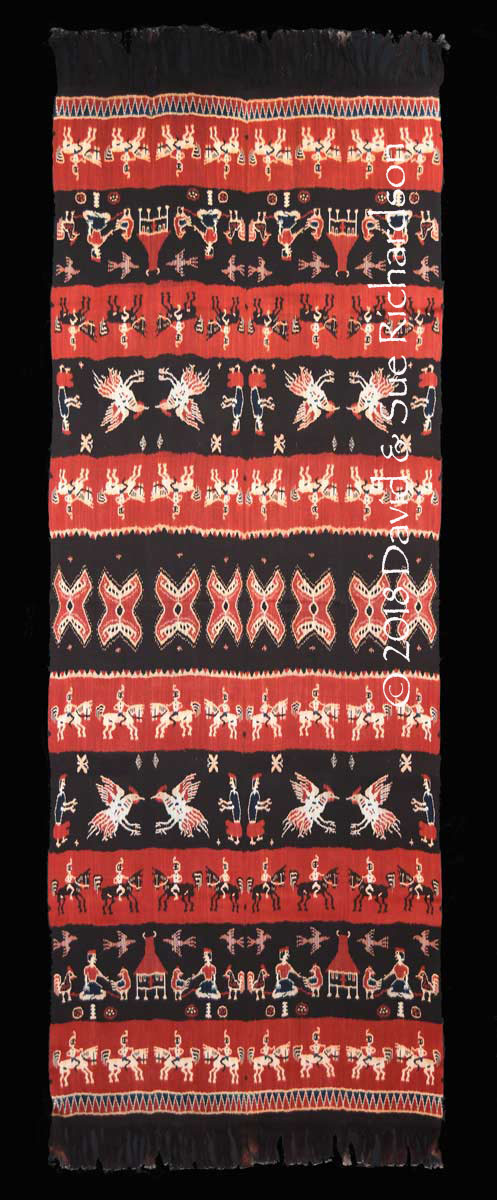

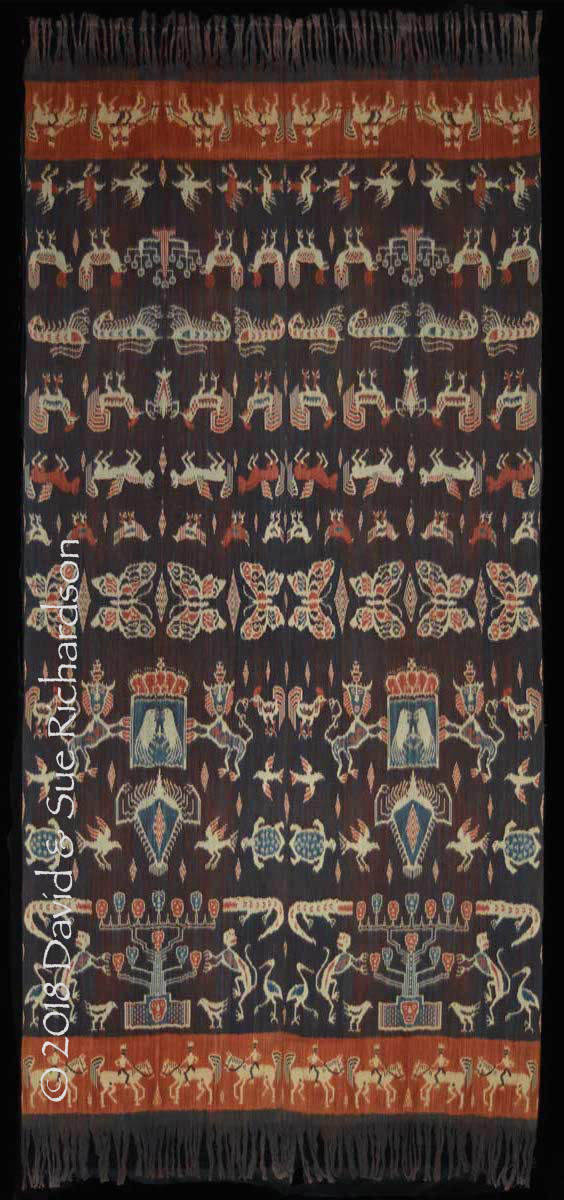

The highest quality inggi kombu rara in our collection was woven in 1948 by Rambu Nai Matolang, from Laiwila hamlet in Desa Kaliuda. Laiwila lays on the main coastal road just two settlements further west than Kaliuda.

It is one of an identical pair and was made when she was just 15-years-old and already betrothed to a member of the Mangili royal family who belonged to the leading aristocratic Matolangu clan. She was therefore duty-bound to produce an inggi of the highest possible quality. Following the death of her husband, the other matching inggi was used as his funeral shroud and was buried with him in his stone tomb.

Unlike most Mangili inggi it is unusual in being longitudinally unsymmetrical, making the task of binding the motifs twice as laborious. Such blankets are described as inggi hondo wingu in the Mangili dialect, meaning that the top and bottom are different. Hondo means binding. In the Kambera dialect the same term is hondu kihhil.

An inggi kombu rara woven in 1948 by Rambu Nai Matolangu, from Laiwila hamlet in Desa Kaliuda. It is decorated with dugongs, turtles, crowned lions (uki mahang), and stag hunts. Richardson Collection.

The sixth inggi in our collection is also longitudinally unsymmetrical and comes from the collection of Umbu Maku Hinggiranja, a nobleman belonging to the important Matolangu clan and the former kepala desa of the Desa Kaliuda region. He was born on 15 May 1957 and became kepala desa after the death of the former incumbent, Umbu Mangu Abu, in 2007. He lived in the centre of kampong Kaliuda but sadly died on 21 April 2010, aged just 54. His grave is located alongside the other noble tombs in the centre of the village. Local informants believe that the inggi was woven by a noblewoman in kampong Kaliuda who was a close family member, probably living in the same household.

An inggi kombu rara formerly owned by Umbu Maku Hinggiranja, the former kepala desa of Kaliuda. It is decorated with skull trees flanked by monkeys and crocodiles, Dutch royal coats of arms, butterflies, winged horses and shrimps. Richardson Collection

Next is an unusual inggi kombu whose design appears to have been influenced by the textiles of Rindi. It was formerly owned by Umbu Hina Ratu Wula, a member of the Mangili royal family who lived in the centre of the royal hamlet of Kopa. Now in his 90s, he lives at his farm in the nearby rural settlement of Larahau. The inggi was woven around 1960 by an unknown noblewoman in the centre of Kopa village next to the royal graves. Umbu Hina Ratu Wula kept it as an heirloom, stuffed inside a lontar palm basket and securely stored in the roof of his traditional house.

An inggi kombu woven in Kopa, Mangili and owned by Umbu Hina Ratu Wula. It is decorated with butterflies, snakes and the Dutch royal coat of arms, which incorporates the symbol of Partai Golkar with a banyan tree flanked by wheat and cotton plants. Richardson Collection

The final inggi kombu in our collection was woven about 60 years ago by Ina Maru, who lived in Uma Latang in kampong Kaliuda. She is a maramba who belongs to the leading Matalangu clan and was married to a wealthy farmer. Now in her 90s and unable to walk she currently lives in her family farmhouse outside of Kaliuda.

An inggi kombu rara, woven by the noblewoman Ina Maru in Kaliuda. It is decorated with skull trees, the harama dance, and butterflies. Richardson Collection

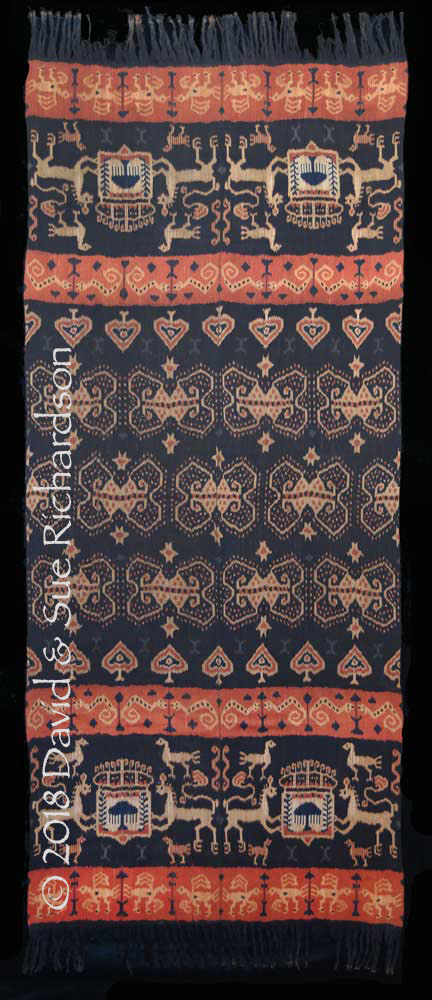

The final Mangili blanket in our collection is an inggi kaworu kambata bara. It too was woven in kampong Kaliuda and was owned by the late Umbu Maku Hinggiranja, a Matolangu nobleman and former kepala desa of the Desa Kaliuda region.

An inggi kaworu kambata bara from the collection of Umbu Hina Hinggiranja, the former kepala desa of Kaliuda. It is decorated with parang-wielding dragons, crayfish, Pacific Black Ducks, cockerels and flying birds. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Modern Mangili Textiles

Mangili remains an important weaving centre today, with many Sumbanese weavers still involved in traditional textile production.

Most Sumbanese men are involved in raising cattle, farming – especially rice cultivation – and harvesting seaweed. Their wives and daughters produce textiles to generate a supplementary income. The Savunese on the other hand are mainly civil servants, school teachers, church employees and also rice farmers. The Raijuans mainly live in two coastal fishing villages – Maukawini and Benda. According to local Sumbanese weavers, the Savunese play no part in the Mangili weaving industry.

Textiles for sale at a house in Kaliuda

There remains a huge local market for low-cost Mangili inggi, not just among the menfolk of Mangili and Waijelu but also to the neighbouring regions of Karera and Masu, where there is a prohibition against weaving. This sustains a sizeable local weaving industry. Although the vast majority of textiles are still naturally dyed, price pressures mean that the quality of the binding on many of these cloths is low.

Kaliuda textiles woven for the domestic market

Unfortunatley today many low cost synthetically-dyed immitations of Mangili inggi are woven in villages like Kawangu in Kambera district.

A weaver setting up her loom to weave the panel of a Mangili-style inggi in Kawangu

Rather brutish-looking Mangili-style inggi on sale at Waingapu covered market