Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kisar Textiles Part 2:

The Weaving of Textiles

The Weaving of Bands and Braids

Kisar Ikat Motifs

Rimanu Motifs

The Origins of Ikat Weaving on Kisar

Bibliography

Go back to Kisar Textiles Part 1

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 3

Go to Kisar Textiles Part 4

The Weaving of Textiles

As George Windsor Earl discovered in 1838 and 1841, the weaving of cotton was widespread across the South Western Islands (Earl 1850, 178). Earl seems to have never encountered ikat before and was therefore surprised by the locally produced cloth, which he described as durable with muted and exceedingly lasting colours - quite unlike anything produced by the Malays, Javanese or coastal tribes of Sulawesi. The locally cultivated cotton was handspun using a simple drop spindle made from a stick with a circular lead whorl. The yarns were then bound with vegetable fibres before they were dyed, creating motifs that had ‘a distinctness and regularity ... calculated to excite no small degree of surprise’. Earl collected several specimens and some years later compared them to similar textiles from Sumatra (‘Batta’ cloths) and from the Dayaks of Borneo, concluding that both of the latter were inferior regarding texture.

In 1882 Riedel found that the Kisarese spent much effort cultivating cotton (aohe) of which there were two varieties (Riedel 1886, 409; Hollander 1898, 539). In addition to cooking, fetching water, gathering firewood and weeding, women were responsible for spinning the cotton, dyeing the yarn red, black, yellow and blue, weaving sarongs and shawls, braiding strainers and mats, weaving hats, knitting small fishing nets and making ropes (Riedel 1886, 426). Almost every home possessed a spindle (pohkor awahe) and small basket (ahawiure) for spinning yarn and a giant clam shell (Tridacna gigas) for dyeing (Riedel 1886, 424 and 426). The islanders traded livestock and agricultural produce for imported white, red or black cotton. It is not clear if this was pre-dyed cotton imported from Europe.

When Baron van Höevell visited in 1887 he found that the wives of the mestizos were weaving very fine sarongs and snikir shawls using their own cotton. The total mestizo population was only 222 according to Riedel, so it is surprising that they exported 300 sarongs and 350 snikirs to Timor in just one year (1890, 217 and 231). They were probably trading textiles made by native weavers as well as their own. In the following year Jacobsen found that when weaving, the women from both the Meher and Oirata communities used braided pattern cards made from coloured lontar leaves (in Meher kanàda, in Oirata sibi) (1896, 132).

Jasper and Pirngadie provided a more detailed review of weaving on Kisar among the Meher community, albeit somewhat disjointed (1912, 19, 38, 105, 113-114, 147-148, 182, 232 and 274). In the following extracts we have transliterated their Dutch ‘oe’ into the English ‘u’.

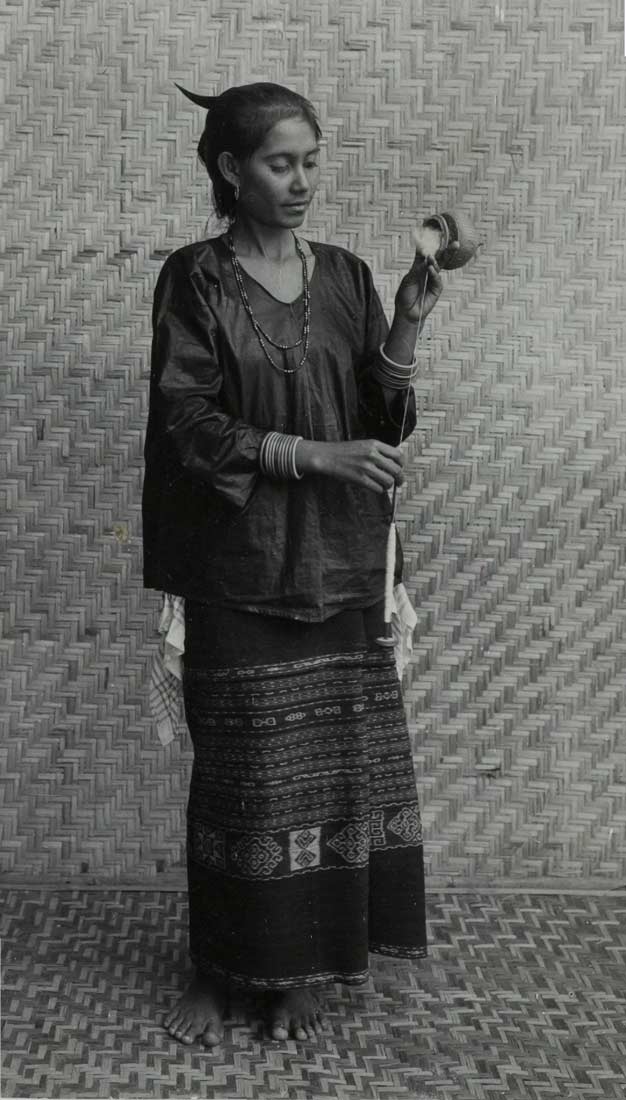

To spin their yarns the local raw cotton was cleaned and ginned using a simple round bamboo stick (nadle) and then fluffed using a bow (bosear). The prepared cotton was formed into a crude rolag and placed into a small round lontar palm leaf basket (ahwiure). The spinner held this in her left hand – see image below – while at the same time teasing out small amounts so that they could be spun using a drop spindle (pokrauwe) twisted with the right hand. The spindle had a whorl made of wood or shell. The spun yarns were then starched by cooking them with the roots of an unknown sea plant.

Demonstration of drop spinning by a woman from Kisar, about 1925, and the lontar palm leaf basket (ahwiure) (Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, and Jasper and Pirngadie 1912)

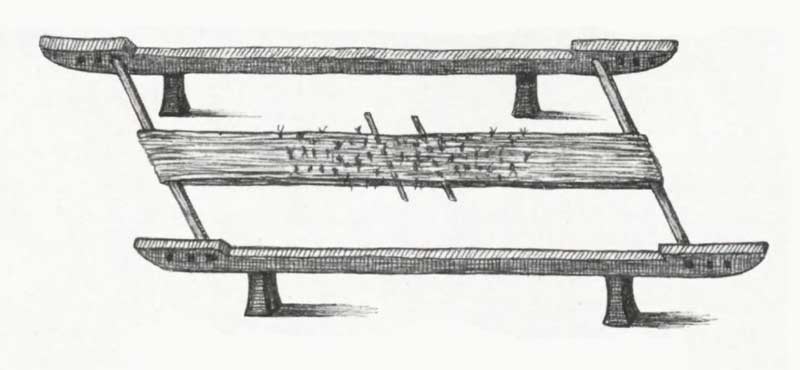

The simple warping up device was called an aunahore and consisted of vertical sticks pushed into the ground. There were two outer sticks (auwaknihe) and two inner sticks (pepehe). Two women sat side by side in front of the frame and passed a ball of spun yarn held in a lidded coconut shell (larnahore) back and forth. The warps were then transferred to the ikatting frame (auwunuku) for binding.

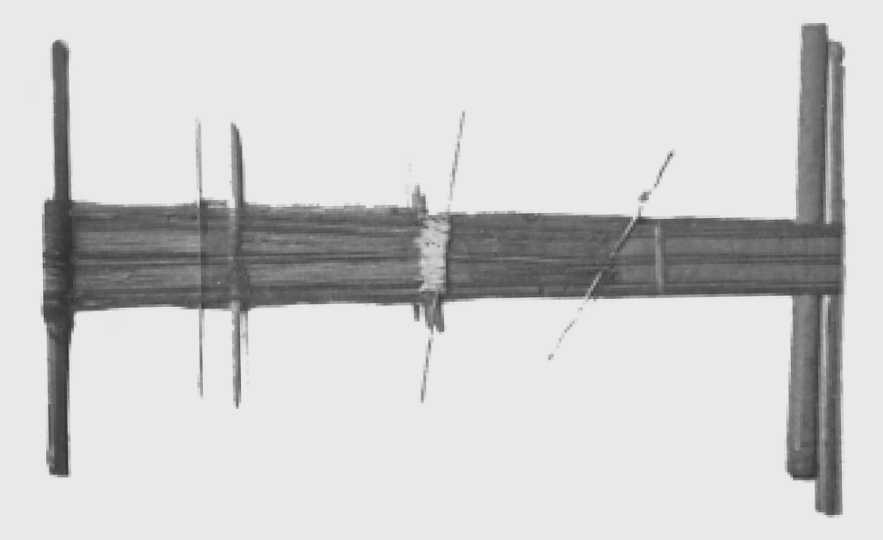

The auwunuku binding frame

(Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, fig. 178)

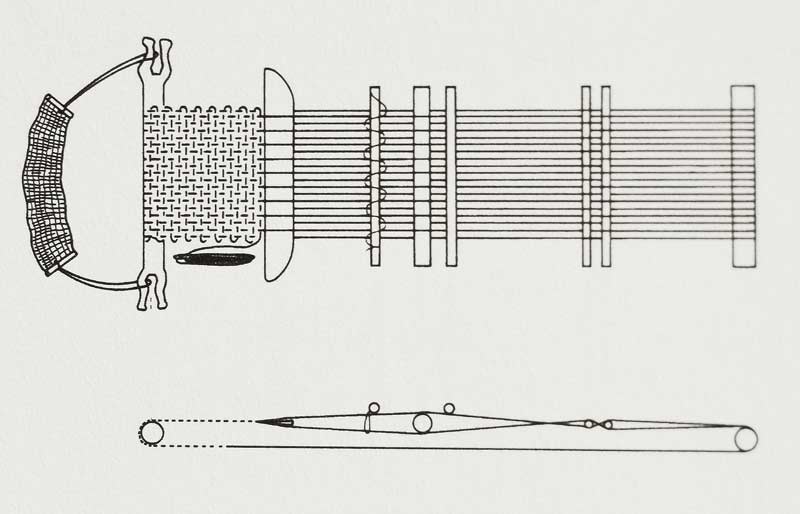

Schematic of the arrangement of the south Maluku loom

(Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, fig. 178)

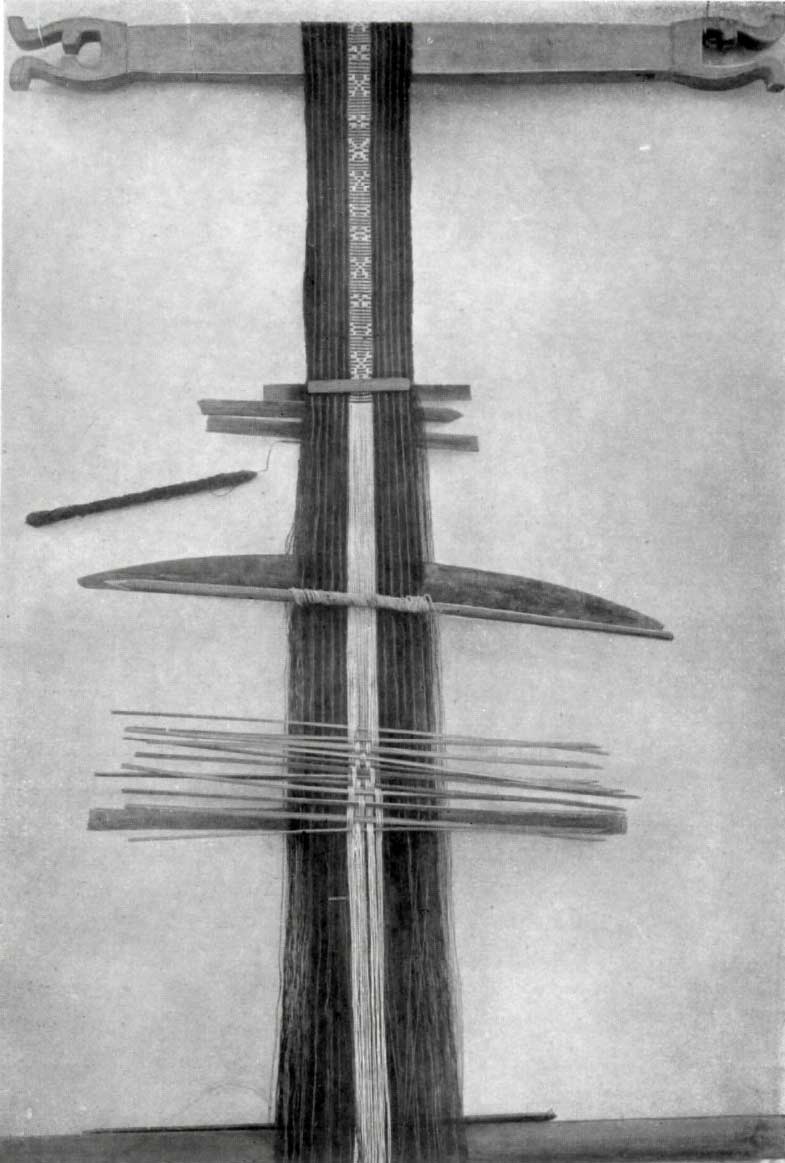

The Kisar back-tension loom used a circular warp and was longer than those used further west, so that the two halves of a tubeskirt could be made from one single loom length. The round bamboo warp beam (oro) could be fastened to the side of the house while the breast beam (akam) was positioned in the weavers lap and tensioned by means of the back strap or yoke (alpukei). The upper shed was separated from the lower shed by a round bamboo roller (lelekan), while the long warp threads were kept in place with cross sticks or lease rods (pepehe). The Kisarese sword (wili) had a distinct shape while the shuttle (howone) was just a simple bamboo rod with notches in each end. For focussing the pattern the weaver used a wooden picker (joon). The pattern formers were usually thin bamboo sticks (auromok).

The Kisarese sword or wili

(Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, fig. 138)

Kisarese Weaving Terminology in 1912

| Dutch | English | Meher |

| reel | reel | ulu alie |

| rolpers, ontkorrelingspers | roller | nadle |

| uitpluizingsboog | bow | boesar |

| rol kapas | rolag | ahwiore |

| uitpluizen | pick | maboesar |

| spinnewiel, spinwerktuig | spinning wheel or machine | pokraoewe |

| haspel | reel or spool | oeloe alie |

| stijven, borstelen | starch, brush | kanaäre |

| stijvingsraam | frame | kanaäre |

| garenafwinder | swift | dodomore |

| scheringtoestel | warping frame | aoenahore |

| ophalers | pickups | joön |

| scheringboom | warp beam | oro |

| liniaal, kruisingstaven | lease rods | pepehe |

| roller | roles | leleken |

| sabel | sword | wilië |

| weven | weaving | kennoe |

| spoel | shuttle, spool | howone |

| borstboom | breast beam | akam |

| lendenjuk | yoke for small of the back | alpoekei |

| touwen van het lendenjuk | yoke harness | kali oknelhe |

| omwinden (ikatten) | binding or knot (ikat) | woenoekoe |

(Source: Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 330-334)

According to Jasper and Pirngadie, the weavers used only red and blue dyes – indigo and morinda. However in 1934 Josselin de Jong found that the Oirata produced a dye for colouring yarn by boiling a tree bark called kurin (1937, 248). This was probably a tannin-based brown dye. The Oirata referred to both tannin and tannin-rich plants as kamir (1937, 244). The Kisarese must have also used a natural yellow dye and a tannin overdyeing technique to produce the yellow and black colours mentioned by Riedel. The South Western Islands must have had a rich natural dyeing heritage in the past. For example, Baron van Hoevëll found that the small islets of Maopora and Nyata near Romang were a rich source of ebony, sandalwood, Yellow Flame tree and sappanwood. The latter was highly valued by the island of Madura, off Java, which dispatched 'ten dozen' perahus to the islands every year to collect the bark to dye their sarongs (1890, 220).

We do not know when chemical dyes first arrived on Kisar but they do seem to have been enthusiastically adopted at an early stage, possibly because Timor was one of the few outer regions of Indonesia where synthetic dyes gained an early foothold (Kahlenberg 1979, 38). By the mid-1920s aniline dyes had already displaced dyes such as indigo and young girls were attending school rather than receiving tuition in natural dyeing (Rodenwaldt 1927, 434). Many cloths collected before 1940 incorporate an extensive use of chemical red, a convenient alternative to the long labour-intensive process of making natural morinda.

Imported pre-spun yarn was also reaching Kisar during the last few decades of the nineteenth century. Around 1925, Ernst Rodenwaldt found that Chinese yarns, some pre-dyed, had been available for over 50 years and was fearful that local cotton would soon be substituted by both Chinese and European yarns (1927, 5 and 434).

Although Josselin de Jong included a number of Oirata textile terms in her 1934 word list, she did not provide us with any insights into Oirata textile production at that time:

A Few Oirata Textile Terms

| cotton, cotton thread | kaisala |

| indigo | taruma |

| tannin | kamir |

| tree bark dyewood | kurin |

| dye yarn | tupake |

| black | laure |

| spindle | an’kai |

| bind (ikatting) | ile |

| weave | uta, la’u pai, la’u uta |

| to plait | ina |

(Source: Josselin de Jong 1934)

Since that time little else has been recorded about the state of textile production on Kisar. In 2004 a women's group formed in the village of Oirata Timur with the aim of promoting and maintaining weaving as a craft as well as providing a modest additional source of income. However by 2012 it was reported that the venture had already lost significant momentum (www.mauteri.org).

The women’s weaving cooperative at Wonreli in 2013

Note the woman on the left with a drop spindle and an ahwiure basket

Meanwhile in Wonreli some local weavers have recently received financial support through a community development programme run under the auspices of Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Mandiri Perdesaan (PNPM Mandiri Perdesaan) (kompass.com 18.10.13). Weavers in both Wonreli and Oirata have also modestly benefitted from a biannual visit by the Australian cruise ship MV Orion, which began calling in 2008 but stopped after 2012.

For a review of the current state of weaving on Kisar, see Kisar Textiles-3.

Return to Top

The Weaving of Bands and Braids

It seems that the weaving of narrow bands was once common on Kisar. Apparently bands as narrow as 5 to 8cm were used as loincloths (Loebèr 1916, 61).

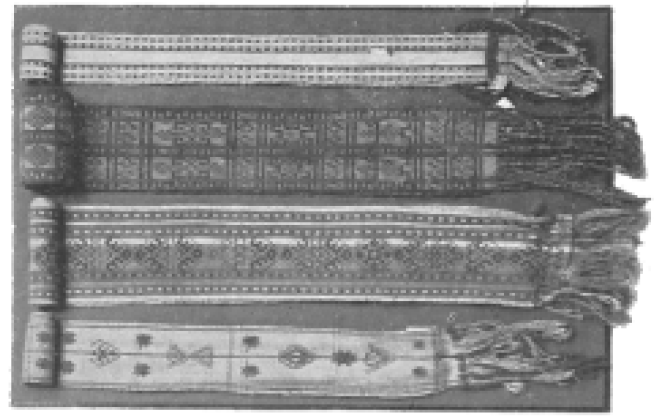

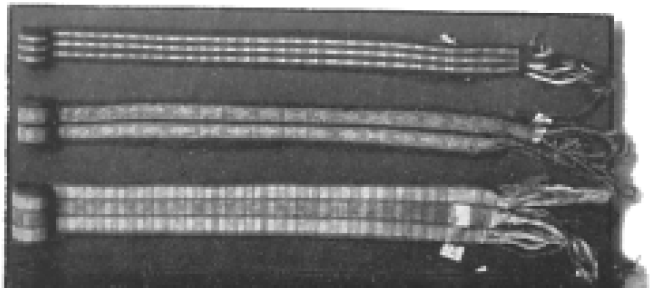

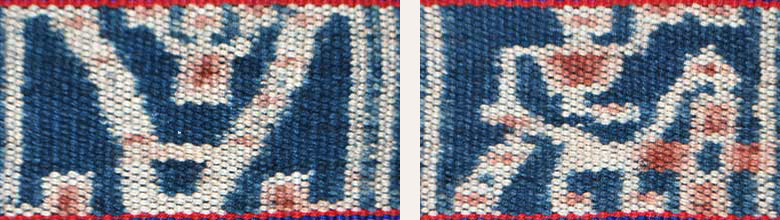

In 1888 the prolific Norwegian collector Johan Jacobsen acquired a dozen bands on Kisar as well as a narrow band loom, all of which were transferred to the Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin (Loebèr 1903, 61). Unlike the ikat technique used for the larger textiles, these bands were woven by inserting a floating ornamental thread – in other words, supplementary weft. Loebèr illustrated what he considered to be the seven most beautiful bands in the Jacobsen collection, two of which showed the height of what a Kisar band weaver could achieve. At least four of the seven were woven in continuous supplementary weft, while a fifth appears to have been woven in discontinuous supplementary weft (Loebèr 1903, plate XIX).

Small loom for weaving narrow supplementary weft bands. Museum für Völkerkunde

(From Loebèr 1903, plate XX)

Four of the bands collected by Jacobsen: the first three yellow, red and white, the fourth blue, red, yellow and white. (From Loebèr 1903, plate XX)

Three more bands collected by Jacobsen: red, green and blue; brown, black and white; and red, green and white. (From Loebèr 1903, plate XX)

A quarter of a century later, the German ethnographer Wilhelm Müller-Wismar acquired four more belts on Kisar, which all appear to have been woven in warp-faced complementary weave (Brigitte Khan Majlis 1984, 290-291).

A loom from Leti island for weaving narrow decorative bands using the complementary warp technique (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, fig. 210)

Return to Top

Kisar Ikat Motifs

In the past, according to Engelenhoven, storytellers on Kisar and Leti narrated their tales with the help of ornaments carved on wooden statues - statues that represented a deceased member of the clan. Each ornament was linked to a specific section of the story. However a distinction was made between ordinary, purely decorative motifs (wona) and special motifs (rou), which were effectively copyright designs that belonged to the specific clan (Engelenhoven 1998, A-38). In the past these motifs were jealously guarded and could not be transferred - they could only be executed and used by those entitled to do so. Apparently such motifs were also used on goldwork and textiles. Consequently the status of one’s clan rather than personal wealth determined the type of design that one could wear.

The Dutch missionaries regarded such statues as a form of idolatry and pressurized the islanders to give them up or destroy them. Now that the island has been denuded of its traditional carvings, the link between the names of many of the rous and the narratives associated with them have been lost. Today traditional textiles are the only medium left to exhibit and communicate these rou even though the weavers who produce them have long forgotten their original meaning.

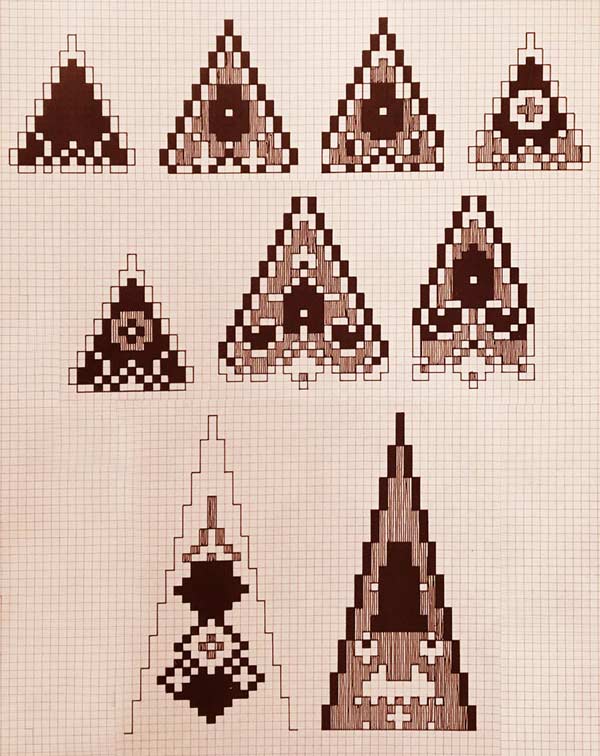

According to Jasper and Pirngadie (1912, 274), ikat motifs on Kisar are generically referred to as bunga angkat, meaning flower. Local weavers distinguish between the endemic bunga angkat Kisar motifs and the introduced bunga angkat Timor. As already mentioned, Jasper and Pirngadie claimed that the latter - which consist of arrangements of lozenge and hook figures as well as images of men and animals - were introduced from East Timor in 1897. However it is likely that many design elements had already been shared with East Timor, and perhaps Luang, long before then.

Some of the patterns imported from Timor were referred to as rimanu and their use was restricted to the nobility. According to tradition, the use of these rimanu patterns by those forbidden to do so was punishable by death (Jasper and Pirngardie 1912, 274). Such infringements sparked bloody wars on neighbouring Wetar, leading to a decline in its population. The islanders resolved the problem by swearing an oath to only use textiles imported from other islands.

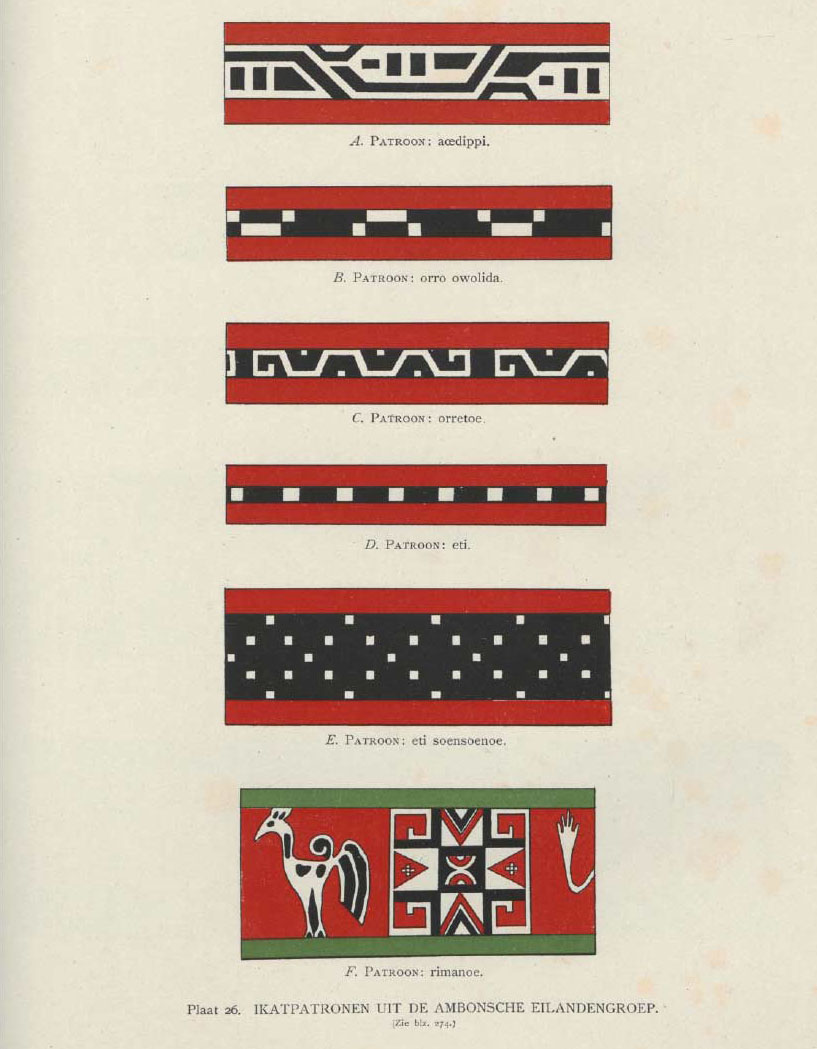

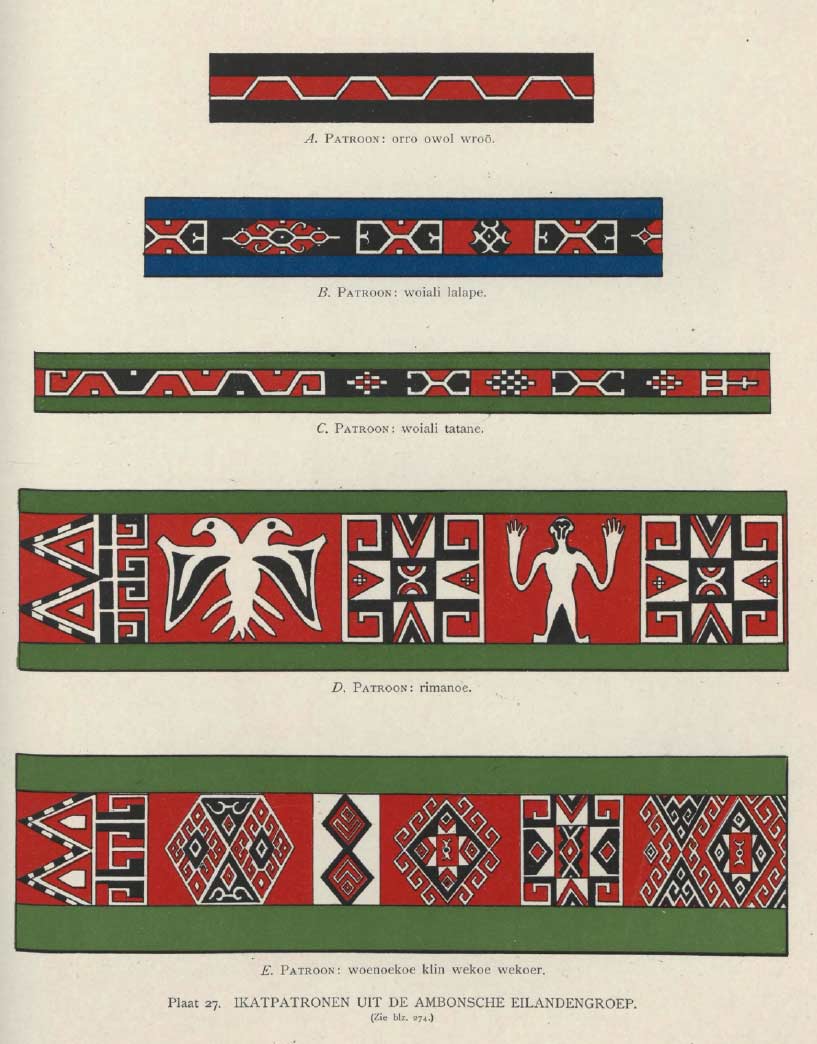

Kisar motifs illustrated by Jasper and Pirngadie (1912, Figs. 236 and 237)

Segmented square with key or hook figures and diamond pattern with key or hook figures.

The problem is that it is not entirely clear from Jasper and Pirngadie which motifs fall into the so-called rimanu category. They list and illustrate the most common patterns from the ‘Ambon Archipelago’, which encompasses both the South Eastern and the South Western Islands (1912, 273 and plates 26 and 27):

- audippi – a meander with additional geometric detailing,

- eti – a repeating dot and dash,

- eti sunsunu – a row of dots arranged in the form of diamonds,

- orro owolida – alternating dots and dashes,

- orreto – a row of angular snake-like motifs,

- orro owol wroo – a simple angular meander,

- woiali lalape – pairs of linked pentagons separated by hooked diamonds and hexagons,

- woiali tatane – an angular snake-motif combined with other geometrical figures

- rimanu – a double tumpal, double-headed eagle, eight-pointed star, an anthropomorphic figure with raised arms, and a cockerel, and

- wunukue klin weku wekur – various hooked diamond patterns along with a double tumpal and the eight-pointed star.

Ikat patterns from the Ambon Archipelago

(Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, plates 26 and 27)

This would indicate that the anthropomorphic figure with raised arms and large hands and the zoomorphic motifs such the cockerel or jungle fowl and the double-headed eagle are classified as rimanu motifs, but the motifs incorporating hooked diamonds are not. Mysteriously the double tumpal and the square enclosing an eight-pointed star are regarded as rimanu if they appear alongside anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs, but apparently not if they appear with hooked diamonds.

The term rimanu appears to be a combination of the term rou, meaning copyrighted motif, and manu, meaning chicken. One wonders if at the time of their introduction in 1897 or earlier the term rou was applied to a range of motifs, only one of which was rou manu. By 1912 Jasper and Pirngadie applied the term rimanu to the full range of restricted motifs, only one of which was the chicken or cockerel.

Restrictions on the use of motifs still apply today. In 2012 a Jakarta Post reporter interviewed a 72-year-old weaver at Lekloor who was producing an ikat cloth with motifs that were restricted to the Rehiara and Dadiara families (Somba 2012).

These same restrictions on the use of textile motifs apply in neighbouring East Timor, as explained by Joanna Barrkman (2009, 11):

Within the diverse cultural groups of Timor-Leste textile motifs were employed as indicators of social status, with restrictions being placed on those who could make and/or wear specific regional and clan motifs. In some instances textile motifs were reserved for specific sacred ceremonies or for use only by rulers who had the authority to publicly wear these motifs. Other motifs were specifically reserved to adorn cloth worn by warriors, empowering them to undertake warfare. Such restricted and powerful cloths were in some instances stored inside the clan’s ceremonial houses where their potency was protected by the ancestors (Barrkman 2009, 11).

Some East Timor patterns and motifs were restricted to a particular family or clan while others were not (Soares 2015, 22). Weavers who violated these restrictions could be harmed. Sacred motifs that were controlled included the boat (loiasu) and the worm (ifi) - the latter linked to the Fonseca family of Tutuala. Non-proscribed motifs included the star (ipinaka), pori leaf (pori-asa), three-stone cooking stove (lafuru) and eagle (mai) - the latter confusingly appearing identical to a tumpal.

Fataluku ikat motifs:

left the boat (loiasu) and right the horse and rider (kuca hiapi)

Interestingly in the Lautem region of East Timor it was traditional for a lau tubeskirt destined for the ruling family (liurai) to be decorated with at least seven motifs, the number seven being considered sacred (Soares 2015, 28). A lau with six or less motifs was not fit for a liurai to wear and was called a sica lau poukalaru or cloth without sails (Forshee 2014, 215). Several other types of lau from this area destined for the nobility also incorporate seven motifs. They include the lau upu lakuwaru reserved for the royal caste of Lorehe, the lau kusin aravei used as a saddle for taking royal brides to their weddings and the charunaku lau worn by the royal caste at the villages of Luarai and Ira Ara in Los Palos. During the period of Portuguese rule, only the nobility of far eastern Tutuala district could wear a sica lau blanket or a lau skirt that featured the boat motif (loiasu), horse motif (kuca or kucha) and figures of people (ma’ar ma’ar lauhana). In Tutuala today, one special tais design incorporates seven motifs based on rock art paintings from the local Ile Kére Kére cave including the cloud, eagle mouth, horse, three boats and pori leaves. It is termed a sica lau loiasu fanu, loiasu meaning boat and fanu meaning face, yet understood to be a cloth bearing rock art motifs (Forshee 2014, 215; Soares 2015, 20).

It does not seem that this tradition of applying seven motifs for the nobility has transferred to Kisar. While the finest Kisar textiles contain a range of motifs, sometimes up to seven, many contain just four, five or six.

One unusual feature of Kisar textiles is that individual ikat motifs were sometimes embellished by stencil painting or by outlining them in black (Langewis and Wagner 1964, fig. 207; Khan Majlis 1991, 316).

Return to Top

Rimanu Motifs

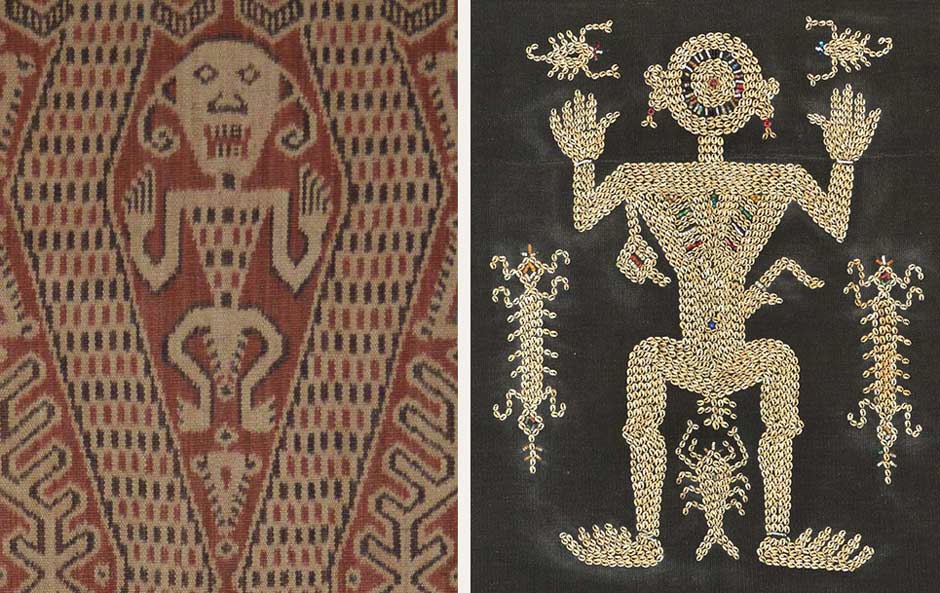

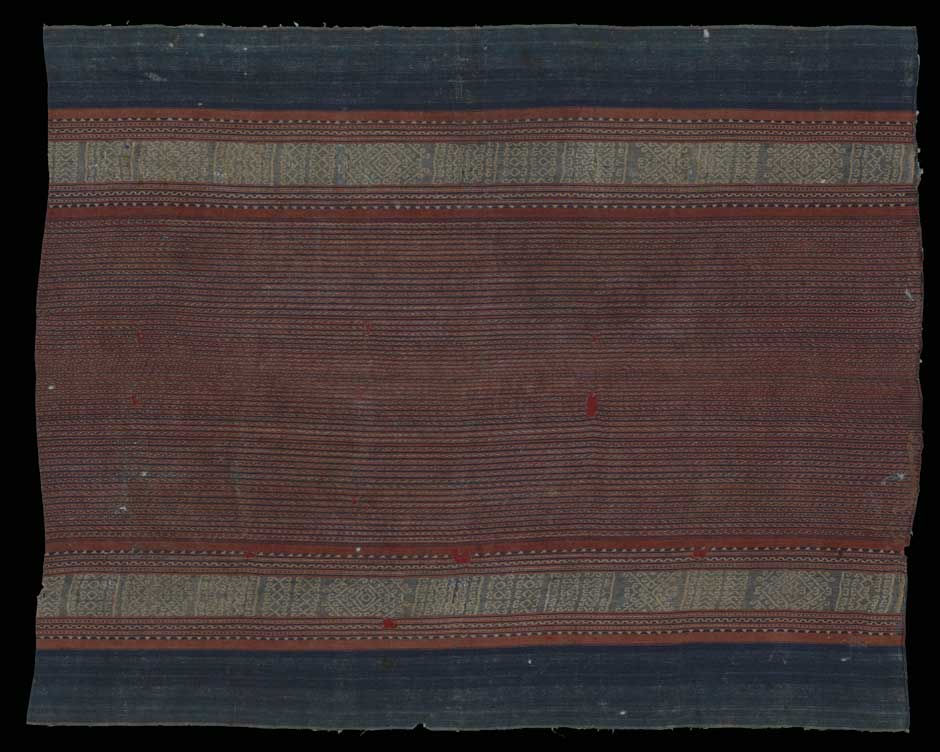

Jasper and Pirngadie applied the term rimanu to a very limited number of motifs from the Ambon Archipelago, which encompassed Kisar and Wetar. These included the anthropomorphic figure with raised arms and hands, the cockerel, the double-headed bird or eagle, the eight-pointed star and perhaps the double tumpal motif. They were used to decorate the main warp ikat bands on women’s sarongs, men's blankets, and men’s ceremonial loincloths, some of which are no longer made today.

Rimanu motifs on a homonon collected in 1975 for the Siwalima Museum, Ambon, Maluku

The interpretation of textile motifs is a risky and sometimes foolhardy activity, perhaps even more so on Kisar where the original meaning of many motifs seems to have been lost. We can never know how individual motifs came into being or what was in the minds of the weavers who first employed them. Weavers often interpret similar motifs in different ways, depending on the nature of their own culture and local environment. The following comments should therefore be read with caution.

Anthropomorphic Figures

The Meher community at Wonreli still consider it obligatory for a bride to be married wearing a homonon decorated with anthropomorphic figures (Finesso, Wahyudi and Sadju 2013). The sale of such sarongs is supposedly forbidden.

Peter ten Hoopen is incorrect in claiming that Oirata cloths never have anthropomorphic or zoomorphic motifs (http://www.ikat.us/ikat_274.php, accessed 21.08.17). As an example, the nineteenth century ‘homnon‘ collected in 1914 from Oirata by Wilhelm Müller-Wismar for the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin shown above is decorated with both anthropomorphic forms and the figure of a bird with outstretched wings.

Robyn Maxwell believed that anthropomorphic figures were among the oldest symbols to be found in Southeast Asian textiles (Maxwell 1990, 17). They are widely found across Indonesia, in for example the tampans and palepais of Lampung on Sumatra, the Dayak pua kumbu of Kalimantan, and in the mawa of Sulawesi.

The anthropomorphic motifs found in Kisar textiles are tightly proscribed, depicting a standing figure with raised arms and large open hands displaying individual digits. Anthropomorphic figures with raised and enlarged hands and arms are also found in a number of other Indonesian regions, such as Kalimantan, Ngada, East Sumba and West Timor as well as in Timor-Leste.

Left: Figure on a pua kumbu cloth from the Kantu’ Dyak people of the Upper Kapuas River, Kalimantan. Richardson Collection

Right: Image of a founding ancestor on a mud-dyed lau wuti kau, East Sumba

Richardson Collection

Metal headdress from Timor Leste. Richardson Collection.

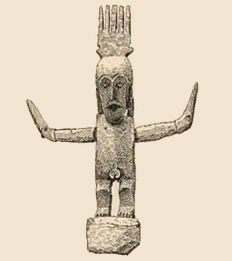

It is possible that such figures represent the mythical ancestors of a specific clan or lineage. A special category of carved wooden statue found across the islands from Timor to Tanimbar depicts an upright figure with raised arms and hands and represents the founding male or female ancestor of a descent group (De Jong and van Dijk 1995, 52-53). Such statues include:

- the carved wooden luli of Leti and Lakor, which represent the first female ancestors. Such founding mothers are depicted holding their arms up and to the side with the palms of the hands facing either forwards or towards the head.

- the wooden founder statues of Babar, which represent the forefathers of the village descent group.

- the stylised, intricately carved tavu house altars of Tanimbar, representing both the male and female ancestors of a noble family. The ancestors are carved with outstretched arms transformed into decorative curving branches. Such altars support the central roof beams of the great houses and are surrounded with valuables and ancestral remains such as skulls, bones and wooden effigies.

De Jong and van Dijk believed that founding ancestors were depicted in a standing position, often with their arms raised high, while common ancestors were mostly depicted in a squatting position. But, as we shall see, this convention does not seem to apply to Kisar.

Unfortunately few of the once highly treasured statues from Kisar seem to have survived. According to Jacobsen (1896, 120) the wooden carvings of the forefathers stood on the ‘plank of the ancestors’ next to the bedhead in a room without a ceiling, so that their souls could freely enter and leave through a hatch in the gable. Jacobsen found six small and two large ancestor figures, one of which was carved with female breasts, in the abandoned village of Lekioto on the southwest coast of Kisar. Unlike Leti, Babar and Tanimbar, it seems that most of the male ancestor figures on Kisar were carved in a crouching position with raised knees, in the same way that the dead were buried, while the female figures were carved with crossed legs (Jacobsen 1896, 122-123; Baron von Hoëvell 1895, 135). According to Rodenwaldt, these ancestor images were called opleras and, while some were kept in the islander’s homes, others were kept in ancestral houses located on the peaks of the highest hills (1927, 6).

Jacobsen (1896, 129) also mentioned that almost every Kissarese carried a small idol in a red bag or basket around his neck or his wrist as a wartime amulet. It was normally in the form of a squatting man, just one to three inches tall, and was made of horn, tin, ivory, wood or even gold. When a person died a stone was placed beside their body so that their soul or shadow image could pass into the stone. The idol was then placed on the stone so that the person’s soul could take possession of it.

One exception is a carved standing figure with raised arms that was collected on Kisar by Pastor Dr. J. G. de Vries in 1891 for the ethnographic museum in Amsterdam (Pleyte 1897, 347). However this was not the figure of an ancestor but of one of the islanders lower gods, the God of the Dance.

Sketch of the 'God of Dance' collected by Pastor de Vries (From Pleyte 1897)

The carved ancestor figures were only put on public display during the great fertility ritual - the purka or idol festival - a hedonistic event held every autumn at the beginning of the rainy season, the start of the new agricultural cycle. It was held under a morinda tree in the ceremonial village and lasted for weeks, involving the mass sacrifice of pigs, feasting, singing, dancing and sexual orgies (Jacobsen 1896, 125; Pleyte 1896; Stöhr 1976, 197). The ritual celebrated the union of the deity father sun, opolere, with the deity mother Earth, oponuse, through the medium of the morinda tree and would ensure the fertility of the people, their crops and their livestock. The celebration of this feast demanded the presence in the village of all members of the community, the dead as well as the living. The dead, in the form of statues, were given a place in the centre of the village (De Jong 2017).

If Jacobsen's descriptions of the carvings of Kisar are correct, the implication is that the anthropomorphic motifs found on the local textiles are not modelled on local ancestor figures and must have therefore been imported. The most likely sources are East Timor and/or Luang, the latter being the origin of many of the influential marna noble families.

Cockerels and Chickens

The sacrificial chicken or cockerel is frequently depicted in Indonesian art. It appears in the tampans of Sumatra and the warp ikats of Timor, East Sumba and Savu. On Sumba the chicken symbolises protective, ancestral power (Forshee 2001, 55-56). Cockerels are fighters and fearless defenders of their territory and their hens and symbolise nobility courage, strength and fertility. Sometimes an ancestor is depicted in the form of a cockerel.

Some Kisarese decorated the gables of their houses with primitive depictions of chickens (Rodenwaldt 1927, 6). In some Kisar textiles an anthropomorphic figure is placed above a cockerel.

Interestingly, chickens are involved in all of the rituals associated with weaving.

Bird and Fish Motifs

Chickens are not the only zoomorphic figures found in Kisar textiles. The single bird motif appears rarely in Kisarese textiles. Birds are generally considered creatures of the upper world. A bird motif appeared on some of the gold crowns, masks and plates in the treasury of the Raja of Kisar (Rodenwaldt 1927, 21).

A single bird appears close to a cockerel on this narrow selendang

(Tropenmuseum 1772-1195, collected around 1940)

Fish and cockerel motifs on a homonon from Kisar

Richardson Collection

Small fish motifs also appear on a few Kisar textiles. In the past some Kisarese decorated the gables of their houses with primitive depictions of fish (Rodenwaldt 1927, 6). Meanwhile single and pairs of dolphins were embossed onto the large gold circular discs known as mas bulan, which made up an important component of the Raja’s treasury.

A mas bulan decorated with pairs of birds and dolphins

Double-Headed Eagle

The double-headed eagle motif is common in the textiles of Kisar and is probably indirectly linked to the coat-of-arms and flag of the Habsburg monarchs who ruled Austria and Spain in the 16th and 17th centuries (1566 through to 1700). Portugal was part of the Habsburg Empire from 1581 to 1640 following the alliance between the crowns of Portugal and Hapsburg Spain, known as the Iberian Union. This motif became widely disseminated in Portuguese Asia, even appearing in Chinese silks (van Campen 2015, 86). It may have reached Kisar through contact with Portuguese East Timor or through inter-island trade.

Eight-Pointed Star

The eight-pointed star is another motif that is widespread throughout Indonesia, from the songkets of Palembang and the Minangkabau on Sumatra to the ikats of Nita in Sikka, Flores.

Some have suggested that this motif was copied from Indian patolu or trade cloth designs. However the eight-pointed star only appears in the border stripes of a few rare patola types – specifically Bühler’s Motif Types 32, 38, 41 and 44 – all of which appear to have been made for the domestic Indian market rather than for export (Bühler 1979, 119, 133, 137 and 146). Even more obtuse, some have suggested that the eight-pointed star is derived from the much more common eight-rayed flower basket or chhabadi bhat patola motif, Motif Type 11.

It seems to us pointless to look for the origin of such a ubiquitous textile pattern. One of the more creative suggestions is that the eight-pointed star is a relic of Southeast Asian and Indonesian plait work (Solyom and Solyom 1984, 13). Alas we will never know.

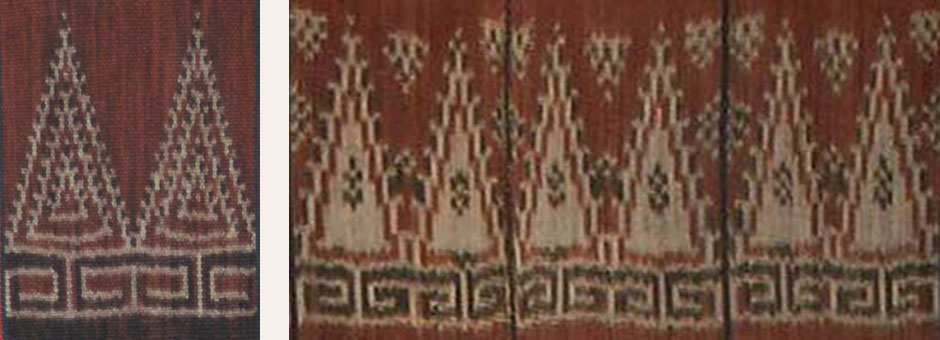

Double Stepped Tumpal Motif

The majority of Kisar warp ikat textiles include terminal double tumpals in the widest decorative band and terminal single tumpals in the narrower ikat bands. These almost always take a stepped or barbed form and sit on angular scroll-shaped feet.

Kisarese tumpal motifs

Similar tumpal motifs are found in ikats from across the South Western Islands, from Leti to Luang, Babar and Tanimbar (Khan Majlis 1984, 296-324). Tumpals also appear widely across Indonesia - in the pua kumbu of Kalimantan, the seko mandi and mawa’ cloths of Sulawesi, the songkets and bidaks of Sumatra, the batiks of Java and Sumatra, the lafa blankets of Rote, the hanggis of Kodi and the patola ratu hinggis of East Sumba.

The Indonesian textile literature frequently mentions that such motifs are based on Gujarati double ikat patolu designs. One can readily see how the layout of a Rotinese lafa or East Sumba hinggi mirrors that of a patola – indeed many not only include the terminal row of tumpal motifs, but also the synchronised adjacent row of small spotted diamonds. However tumpal motifs are not that common. Out of the 53 designs of patola identified by Bühler and Fischer, tumpals appear in Motif Types 8, 11, 12, 17, 18, 19, 21 and 23, mostly in a truncated form. Elongated tumpals are mainly found in Types 11 and 12 ‘flower basket’ chhabadi bhat patolu that were made for the export market – the type most commonly found across the islands of Indonesia. Long-form tumpals appear to be far more common in the Indian mordant-printed trade cloths that were exported to Indonesia in greater numbers (Peck 2013, 20).

Tumpal motifs from Gujarati patolu. The ikat process requires them to be stepped.

(Redrawn from Bühler and Fischer 1979, vol. 1, 180)

However not all writers agree with an Indian patola origin. In Malaysia and Sarawak tumpals are regarded as stylised bamboo shoots (pucuk rebung). Alternatively they are said to represent hills or mountains (Manansala 2016, 405). Other scholars believe they symbolise the cosmic Mount Meru where the gods abide (Abu Bakar 2002, 47; Lee 2006; Lee-Niinioja 2010, 126). Holmgren and Spertus point out a possible connection to aligned rows of tumpal shapes incised on early Austronesian Lapita ceramics (1991, 75). Another idea is that they originate from the Dong Song culture of southern China/north Vietnam – rows of small tumpal-like triangles appear as circular outer borders on some bronze drums. Tjandrasasmita and Lee-Niinioja note that the tumpal is one of the most widely distributed pre-Islamic ornamental motifs found on Buddhist-Hindu temples, including those on Java, some of which date back to the fifth century (2008, 117). Whilst acknowledging that the origin of the tumpal remains uncertain, they suggest it at least dates back to ancient Neolithic or megalithic times.

Alfred Bühler initially believed the tumpal was of old Indian origin (1945, 2480). He later changed his mind. Although they occurred in patola, their frequent use in the textiles, mats and baskets of Southeast Asia, Indonesia and even Oceania led him to regard them as Malayo-Polynesian (Bühler 1959, 12). Rouffaer and Juynboll had earlier argued that the tumpal must be of Malayo-Polynesian origin because it had spread into the remotest reaches of Indonesia, Melanesia and Polynesia where the influence of foreign decorative art had never penetrated (1899, 163). They proposed that the textile producers of Cambay and Coromandel acquired the tumpal motif from the East Indies and modified it to satisfy local tastes, only later re-exporting it back to the East Indies. Evidence from the last few centuries certainly illustrates how Indian producers adroitly adapted their trade cloths for the different Southeast Asian export markets.

Whether the tumpal originated in Indonesia or India, it seems highly likely that it entered the iconography of Kisar through the medium of textiles. The difficult question is how? This could have been through the direct influence of textiles from India – as we shall see later, Indian patolu and trade cloths were being imported into the Banda region in quantities before the arrival of the Portuguese and we know that some found their way to Kisar. An alternative possibility is that the motif was Indian-inspired but was imported via East Timor or one of the neighbouring islands.

A third intriguing possibility is that it actually arrived with the first Austronesian weavers who may have reached Kisar from Sulawesi just over one thousand years ago. Relics of their weaving style can be found in the handful of centuries-old Minahasa and Porso sarongs that have survived to the present day. Some do not include tumpal motifs but one or two do (see the discussion in The Origins of Ikat Weaving on Kisar below).

Hooked Diamonds

According to Jasper and Pirngadie, hooked diamonds are not classified as rimanu motifs. Such motifs are extremely common, found in textile designs across Central Asia, Southeast Asia and Indonesia, pointing to a pre-historic origin. Throughout West Timor such designs are termed k’aif or mak’aif motifs. In the past, in regions like Belu and Biboki, the number of hooks included in the mak’aif motif indicated the social status of the wearer. Commoners would wear a single hook mak’aif or a two-hook mak’aif for daily wear, and a three-hook mak’aif for ceremonial wear. Aristocrats would wear motifs containing up to twenty-two-hook mak’aif for ceremonial occasions, indicating their high status (Asche 1995, 122; Leibrick 1994, 9- 0). These conventions are still observed today.

Return to Top

The Origins of Ikat Weaving on Kisar

While we cannot trace the origin and evolution of ikat weaving on Kisar with certainty, there are some intriguing pointers to how it might have arrived and developed. One of the first observations is that there is very little Chinese, Indian, Islamic or European colonial influence in Kisar textiles, suggesting that they are primarily a product of the Austronesian world.

Jasper and Pirngadie thought that the ikat textiles of the Ambon Archipelago had a striking resemblance in almost every respect to those of Bentenan, a coastal village and also a small offshore island in southeast Minahasa, north Sulawesi. They concluded that the patterns must have originated in Bentenan and reached the Ambon Archipelago via the Ternate Islands (Jasper and Pirngadie 1912, 274).

Over thirty years ago Brigitte Khan Majlis separately pointed out similarities between the ikat designs found on a very rare sarong collected by Holmgren and Spertus from the Poso region of Central Sulawesi and those from southern Maluku (1984, 160). The former has a somewhat similar layout to several other early sarongs, including one in the Kahlenberg Collection acquired in the same region (Barnes and Kahlenberg 2010, 254-255).

Cloth for a sarong from the Poso region of Central Sulawesi

Note the box-shaped motifs and the eight-pointed star

Sarong from the Poso region of Central Sulawesi, carbon dated to the 15th or 16th century. Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection

More recently Geneviève Duggan has looked again at the historical and textile links between Sulawesi and the Lesser Sunda Islands (Duggan 2015, 53-83). We already know that Makassarese merchants traded widely throughout eastern Indonesia in the past. However a map belonging to the Sultanate of Gowa illustrates that prior to 1660 – and therefore probably also before the arrival of the Europeans – the sovereignty of Makassar was widespread, extending as far south as north Australia (Ganter 2005). Meanwhile local narratives suggest a pre-Portuguese migration from Luwu and Makassar to Timor via Abi and Tunbesi (Tukang Besi?) in South Sulawesi (Spillett 1999, 29 and 31).

Duggan’s main theme is to suggest a connection between the high quality Bentenan textiles from north Sulawesi, named after Bentenan Island, and those of the Lesser Sunda Islands. The former produced seamless tubular sarongs woven on a back tension loom using a continuous warp. A specific feature of these sarongs was that the entire warp was interlaced with weft. Of course as the weaving progressed, the length of the unwoven warp decreased to a point where the shed became too small to pass the shuttle through. The final section of cloth was therefore laboriously woven using a needle rather than a shuttle – a technique that was maintained until the end of the nineteenth century. An example of a similar Poso sarong, collected by the late Mary Hunt Kahlenberg, has been carbon 14 dated to the late fifteenth or sixteenth century (Barnes and Kahlenberg 2010, 254-255).

In the Lesser Sunda Islands seamless tubular textiles have been produced by the Lamaholot in East Flores and on Lembata Island and also by the Bali Aga at Tenganan Pegringsingan on Bali. Although the short unwoven section of warp in these textiles has not been finished with a needle, it is regarded as sacred and there is a prohibition against severing it. Finally, on Savu Island, the kenoto bridewealth bag is woven with a complete circular warp and while the unwoven warps are removed from a skirt cloth they are still considered powerful and sacred (Duggan 2015, 66). Could it be that these circular warp textiles originated in north Sulawesi and were brought south by immigrants who subsequently abandoned the laborious stage of interlacing the unwoven warps with a needle?

Duggan’s observations echo an earlier study of ikat techniques and processes by Alfred Bühler, which concluded that seamless tubular ikat textiles are the remnant of an ancient technique that may have originated in Minahasa, northern Sulawesi (1943, 47-168).

Another feature of the sarongs from northern Sulawesi is that they have a similar layout to those from Kisar, with a centre field of narrow stripes, ikat bands composed of box-shaped motifs (sometimes incorporating eight-pointed stars and clusters of concentric hooked diamonds) and plain indigo or black end-bands.

Sarong possibly from Minahasa and estimated to be 16th or 17th century

(Image courtesy of the Indo-Pacific Collection, Yale University Art Gallery)

Sarong listed as possibly Minahasa Toraja and attributed to the 17th or 18th century

(Image courtesy of the Indo-Pacific Collection, Yale University Art Gallery)

Thanks to the Australian linguist Geoffrey Hull we now have a better understanding of how the ancient weaving culture of Sulawesi might have been transferred to Kisar, Timor and the other Lesser Sunda Islands. Is it possible that Austronesian immigrants from the Tukung Besi Islands of south eastern Sulawesi not only introduced the Meher and Kawamina family of languages to Kisar and East Timor around the eleventh century AD but also their own style of ikat binding and weaving?

The Kisaric languages spoken on Kisar and Roma belong to the Timorese group of languages, which the linguist Geoffrey Hull and his colleagues have shown to be closely linked to those from South Eastern Sulawesi – more specifically from the islands of Muna, Buna and Tukang Besi (Hull 1998,149-53). The precursors of the Kemak, Tokode, Idate and Mambai dialects, spoken in western and central East Timor, may have originated from the Muna and Buton Islands, while the Tetum, Galoli and so-called Kawamina family of dialects (Naueti, Waimaha, Kairui, and Midiki), spoken in central and eastern East Timor, may have initially migrated from the Tukung Besi Islands to Wetar and from there to the South West Islands and Timor (Hull 1998, 149-153; Hull 2000, 158; Palmer 2015, 68). While the Austronesian languages may have arrived in north Sulawesi about 4,000 years ago, these specific variants do not seem to have reached Kisar and Timor until very much later – the eleventh century AD (Hull 1998, 150). Until this time only non-Austronesian languages (most or all Papuan) were spoken on Kisar (Hull 2004a).

Not long after the arrival of these new immigrants the Timor region was invaded by people from Central Maluku, probably Ambon, resulting in a simplification of the newly imported Austronesian dialects (Hull 2004).

The early Austronesians had clearly mastered the technology of weaving textiles because linguistic palaeontologists have identified many weaving terms – such as tenun, the word for weaving itself – in the early proto-Austronesian and later proto-Malayo-Polynesian languages. Although we are not sure when, the ikat technique must have been adopted later. The earliest known examples of warp ikat are eight fragments of cotton excavated at Nahal ‘Omer in Israel, attributed to Yemen and dated to the late seventh or early eight century (Baginski and Shamir 1997). A slightly later drawstring bag made from a fragment of recycled warp ikat cotton from the ancient city of Antinoupolis in Egypt is attributed to India or Yemen and thought to be no earlier that the eighth century (Pritchard 2014, 47). Two later warp ikat abaca burial cloths from Banton Island in the Philippines have been dated to the fifteenth century. Meanwhile Jan Wisseman Christie has found that ikat production was an important commercial activity in the Surabaya region of East Java between the early tenth and the late eleventh centuries (1993, 13). The idea that ikat weaving may have arrived on Kisar in the eleventh century is therefore not unreasonable.

If the same immigrant population introduced ikat weaving to both Kisar and East Timor it is perhaps not surprising that we find very close similarities between the textiles of both regions. Khan-Majlis was the first to note the close link between the cloths of Kisar and two textiles from Los Palos - a man's blanket and a sarong - textile types that had never been published previously (1991, 313, 314 and 316).

The man's blanket from the region of Los Palos, East Timor

Since the formation of Timor Aid in 1998, and the recognition of an independent Timor Leste in 2002, there has been increased focus on that region's textiles and it is only now that we are in a position to see that it is not just the ikats and motifs of Los Palos that show links with Kisar, but those of the whole municipality of Lautem (Soares 2015).

Detail of a man’s mud-dyed sica lau wrapper from Tutuala, Timor Leste. The box-shaped motifs enclose anthropomorphic figures, eight-pointed stars and tumpal motifs Richardson Collection

These locations not only share the same motifs, but also have the same customary rules and restrictions on their use as discussed above in the section on Motifs.

Jasper and Pirngadie claimed that the motifs they described as boenga angkat Timor, consisting of images of men and animals and various arrangements of lozenge and hook motifs, were introduced to Kisar from East Timor as late as 1897. Although certain new motifs may well have been introduced at this time, this assertion seems unlikely. As well as sharing the same immigrant textile culture, these two regions enjoyed a long-term historical interrelationship involving trading, migration and intermarriage, which must have resulted in a degree of two-way cultural exchange. The 500 Fataluku-speaking immigrants from Loiquero, Tutuala sub-district, on the north coast of far eastern Timor who arrived in 1721 undoubtedly came with their own weaving culture and design motifs. It was they who settled in the two villages of Oirata, which subsequently became the source of the island’s highest quality ikat.

Kisar and East Timor were not entirely immune to external influences and it seems likely that some motifs have been borrowed from other cultures. For example the stepped tumpal motif, which appears as a doublet in Kisarese textiles and as a single, doublet or triplet in East Timorese textiles, may have been inspired by imported weavings from India. Silk double-ikat patolu from Gujarat, India, (and their block-printed cotton imitations) were being exported to Maluku via Malacca before the arrival of the first Portuguese, as observed by Tomé Pires in about 1515 (Pires 1944, 207). He identified ‘red and black brentangis, caçutos, white and black maindis, coraçones cloth, patolas, and after these there is cloth from Bengal ….’. The Portuguese and Dutch VOC imported many more as prestigious gifts, used to cement relationships with local tribal leaders. Some of these undoubtedly found their way to Kisar, probably via Makassarese, Bugis and other maritime traders. We have no idea of how many patolu reached the island but those that did were highly valued – almost on a par with gold. For example, if an arranged marriage between the children of brothers and sisters (agreed when they were just 5- to 7-years-old) was subsequently broken, the adat fine amounted to two gold discs, two buffalo, one Makassar sarong and one patola (Riedel 1896, 416). Patolas were also employed on Kisar as funeral shrouds (Riedel 1886, 420).

Despite the presence of a Dutch garrison, European influence on Kisar textile design seems to be minor. During most of the colonial era, Kisar lay between the two spheres of influence, Dutch Banda and Portuguese Timor (Riedel 1886, 402). Although a small garrison of Dutch, German and French soldiers was established on the island for a century and a half (from 1665 to 1819) and some of its officers and troops married local women, their only legacy was to influence the dress of their mestizo descendants, not that of the native population. Likewise the efforts of Ambonese missionaries to Christianise the islanders does not seem to have had any impact on their textiles.

The one exception could be the double-headed eagle motif that is found in many Kisar ikats. This might have been acquired directly or indirectly from Portuguese merchants, or from the white Portuguese administration on Timor. Portugal, along with its overseas territories, came under Habsburg rule following its annexation by Philip II of Spain in 1580 and did not regain its independence until 1640. The double-headed eagle was prominently featured in both the coat-of-arms and the flag of the Imperial Hapsburg Dynasty. It even remained popular after Portuguese independence and later appeared in the coat-of arms of Thomas Stamford Raffles, the Lieutenant Governor of the Dutch East Indies from 1811-1816 at the time of the British interregnum. Portuguese-inspired double-headed eagle motifs have also been found on a number of sixteenth and seventeenth century textiles, such as silk colcha quilts finely embroidered in Bengal, and silks and silk velvets embroidered in China for the Portuguese market (Karl 2016, 149; Irwin 1952, 72; Bogansky 2013, 49-50).

The close link to Timor may also explain how early chemical dyes, especially red aniline dyes, and machine-spun cotton yarns rapidly gained a foothold on the backwater of Kisar. Timor is one of the few outer regions of Indonesia where synthetic dyes appear to have taken an early foothold (Kahlenberg 1979, 38). One report suggested that the important colonial trading port of Kupang (with its enterprising Chinese merchants) resulted in chemical dyes being introduced to Timor as early as the 1870s (Hali 1983, vol. 6, 205). Rodenwaldt implied that imported Chinese yarns had been available since the 1870s. While we do not know when synthetic dyes eventually reached Kisar it is notable that the twenty textiles collected by Müller-Wismar in about 1913 were naturally dyed (although they were not necessarily new at that time). Yet by 1925 Rodenwaldt found that natural dyes were rapidly being displaced by aniline dyes and young girls were no longer being taught the art of natural dyeing.

In 1950, immediately after independence, Kisar became part of Maluku, by far the largest of the eight newly formed Indonesian provinces, stretching from the Philippines to Australia and governed from Ambon. Kisar seems to have dropped off the map, left as a minnow in the remotest province of the new Indonesian State. In more recent times Kisar and neighbouring Leti became even further cut off from the outside world as a result of the annexation of East Timor by Indonesia in 1975 and the state of war that persisted up to its violent climax in 1999. This enforced isolation undoubtedly saved Kisar textiles from more recent commercialisation. It may also be one of the reasons why there are relatively fewer Kisar cloths in western collections.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon, 2016. Sekilas Tentang Bahasa Oirata di Pulau Kisar, Ambon.

Bühler, A., 1943. Materialien zur Kenntnis der Ikattechnik definition und bezeichnungen, geschichtliches, mechanische Verarbeitung des Garnes, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie 43, Supplement, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2015. Tracing Ancient Networks; Linguistics, Hand-woven Cloths and Looms in Eastern Indonesia, Ancient Silk Trade Routes: Selected Works from Symposium on Cross Cultural Exchanges and Their Legacies in Asia, World Scientific Publishing, Danvers, MA.

Earl, George Windsor, 1837. Reize door der weinig bekenden Zuidelyken Molukschen Archipel, door Lieut. D. H. Kolff, Amsterdam, 1828 - Voyage through the Southern, or little known part of the Archipelago of the Moluccas, Etc. Communicated by G. W. Earl, Esq., M.R.A.S., Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 7, pp. 369-374, London.

Earl, George Windsor, 1841. An Account of a Visit to Kisser, one of the Serawatti Group in the Indian Archipelago. Extracted from a Letter written by G. W. Earl, Esq., Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 11, pp. 108-117, London.

Earl, George Windsor, 1850. On the Leading Characteristics of the Papuan, Australian, and Malayu-Polynesian Nations, Chapter IV, The Malayu-Polynesians, Moluccan Tribes, The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, vol. 4, pp. 172-181, Singapore

Eijbergen, H. C. Van, 1864a. Aanteekeningen, gehouden op eene reis naar de zuid-westereilanden (Maart 1862), Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Lansd- en Volkenkunde, vol. 13, pp. 193-226, M. Nijhoff, The Hague.

Eijbergen, H. C. Van, 1864b. Aaanteekeningen: Der Verrigtingen van den Ambtenaar ter Beschikking van den Gouverneur der Moluksche Eilanden, Belast met eene Zending naar de Zuidwester-Eilanden, bij Besluit van den 10 den Mei Jl. No. 4, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 129-196, Brill

Engelenhoven, Aone van, 1998. Epithets and Epitomes: Management and Loss of Narrative Knowledge in Southwest Maluku (East-Indonesia), Paideusis - Journal for Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Studies, vol. 1, pp. 29-41.

Engelenhoven, Aone van, and Nazarudin, 2016. A tale of narrative annexation: Stories from Kisar Island (Southwest Malukua, Indonesia), Wicana, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 191-231.

Finesso, Gregorius M.; Wahyudi, M. Zaid; and Sadju, Pascal S. B., 2013. Daya Wanita pada Sehelai Kain, kompas.com, 26 October.

Granucci, Anthony F., 2005. The Art of the Lesser Sunda islands, Editions Didier Millet, Singapore.

Hoëvell, Wolter Robert Van, 1855. Bijdrage tot de kennis der Zuid-wester eilanden, door eenen Zendeling, Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, vol. 1, pp. 225-237, Batavia.

Hoëvell, G. W. W. C. Baron van, 1890. Leti-Eilanden, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 33, pp. 200-232, Batavia/’s Hage.

Hoëvell, G. W. Baron van, 1895. Einige weitere Notizen über die Formen der Götterverehrung auf den Südwester- und Südoster-Inseln, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, vol. 8, pp. 133-137.

Hull, Geoffrey, 1998. The Basic Lexical Affinities of Timor’s Austronesian Languages: A Preliminary Investigation, Studies in Languages and Cultures of East Timor, vol. 1, pp. 97-174, University of Western Sydney, Macarthur .

Hull, Geoffrey, 2000. Historical Phonology of Tetum, Studies in Languages and Cultures of East Timor 3, pp. 158-212.

Hull, Geoffrey, 2004a. The Papuan Languages of Timor, Estudos de línguas e culturas de Timor Leste 6, pp. 23-99.

Hull, Geoffrey, 2004b. The Languages of East Timor; Some Basic Facts

Jacobsen, A., 1889. A. Jacobsen’s und H. Kuhn’s Reise in Niederlänisch-Indien, Globus: Illustrirte Zeitschrift für Länder- und Völkerkunde, vol. 55, no. 14, pp. 213-17, Braunschweig.

Jacobsen, Johan Adrian, 1896. Auf Kissar, in Reise in die Inselwelt des Banda-Meeres, pp. 116-134, Verlag von Mitscher & Röstell, Berlin.

Jasper, Johan Ernst, and Pringadie, Mas, 1912. De Inlandsche Kunstnijverheid in Netherlandische Indië, vol. 2, De Weefkunst, Mouton & Co., The Hague.

Joesef, Hendro, 2012. Merunut kisah pulau selatan daya

[http://teteucu. blogspot.nl/2012/09/sejarah-pulau-kisar.html, accessed on 01.06.2016]

Jonge, Nico de, 2002. The Religious Art of the Southeast Moluccas: Masterpieces in the collection of the National Museum of Ethnology and their cultural context, Digital publication of the National Museum of Ethnology.

Jonge, Nico de, 2013. Life and death in southeast Moluccan art, in Eyes of the Ancestors: The Arts of Island Southeast Asia at the Dallas Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Jonge, Nico de, and van Dijk, Joss, 1990. After sunshine comes rain; A comparative analysis of fertility rituals in Marsela and Luang, South-East Moluccas, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Rituals and Socio-Cosmic Order in Eastern Indonesian Societies; Part II Maluku, vol. 146, no: 1, pp. 3-30, Leiden.

Jonge, Nico de, and van Dijk, Joss, 1995. Forgotten Islands of Indonesia: The Art & Culture of the Southeast Moluccas, Periplus Editions, Singapore.

Jonge, Nico de, and van Dijk, Joss, 2002. Wilhelm Müller-Wismar (1881-1916): Hunting for Answers in the Banda Sea, Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkskunde, vol. 30, pp. 241-260.

Josselin de Jong, Jan Petrus Benjamin de, 1937. Oirata, a Timorese Settlement on Kisar, Studies in Indonesian Culture, vol. 1, Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam, Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers Maatschappij, Amsterdam.

Josselin de Jong, J. P. B., 1937. Studies in Indonesian Culture, vol. 39, issue 1, Noord-Hollandsche uitgevers-maatschappij.

Juynboll, H. H., 1932. Katalog des Reichsmuseums von Ethnographie, Band XXIII, Molukken III, Südost- und Südwest-Inseln, Brill, Leiden.

Khan Majlis, Brigitte, 1984. Südwester- und Südoster-Inseln, Indonesische Textilien: Wege zu Göttern und Ahnen, pp. 119-135 and 290-324, Deutsches Textilmuseum, Krefeld.

Kolff, D. H., 1840. Voyages of the Dutch brig of war Dourga through the southern and little-known parts of the Moluccan archipelago and along the previously unknown southern coast of New Guinea, performed during the years 1825 & 1826, translated by George Windsor Earl, James Madden & Co., London.

Loeber, J. A., 1903. Het Weven in Nederlandsch-Indië, Bulletin van het Kolonial Museum te Haarlem, no. 29, Amsterdam.

Loupatty, Stenly, Pattipeilohy, J. J., and Pattinama, W., 2008. Sejarah kerajaan Kisar, Departemen Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata, Maluku and Maluku Utara Provinces.

Majlis, Brigitte Khan, 1984. Kissar, Indonesische Textilien: Wege zu Göttern und Ahnen, pp. 119-121 and 290-295, Deutsches Textilmuseum, Krefeld.

Manuhutu, Florence Sahusilawane, 2002. Tenun tradisional masyarakat Pulau Kisar, Kecamatan Pulau-Pulau Terselatan, Kabupaten Maluku Tenggara Barat (MTB), Propinsi Maluku, Ambon.

Meyer, A. B., 1882. Die europaische Colonie auf der Insel Kiser im Ost-indischen Archipel, Müteüungen aus Justus Perthes' geographischer Ansalt, Dr. A. Petermann, 28. Band, pp. 334-5, Justus Perthes, Gotha.

Müller-Wismar, W., 1914. Dagboek Kisar, Manuscript, Hamburgisches Museum für Völkerkunde und Vorgeschichte, Hamburg.

Nazarudin, Nazar, 2013. Kamus Saku Bahasa Oirata-Indonesia: Sekilas Catatan Bahasa yang Terancam Punah.

Nazarudin, Nazar, 2017. Private communication.

Nieuwenkamp Wijnand Otto Jan, 1923. Een kort bezoek aan de eilanden Kisar, Leti en Roma, Nederlandsch-Indië Oud en Nieuw, vol. VIII, pp. 99-107.

Nieuwenkamp, Wijnand Otto Jan, 1925. Zwerftocht door Timor en Onderhorigheden, Amsterdam.

Pleyte, C. M., 1896. Seltene ethnographische Gegenstände von Kisar, Globus, vol. 70, pp. 347-349.

Reinwardt, Caspar Georg Carl, and Vriese, Willem Hendrik, 1858. Reis naar het oostelijk gedeelte van den Indischen Archipel in het jaar 1821, pp. 369-374, Frederik Muller, Amsterdam.

Riedel, Johann Gerard Friedrich, 1886. Het Eiland Keisar of Mekisar, De sluik- en kroesharige rassen tusschen Selebes en Papua: Uitgegeven door tuschenkomst van het Nederlandsch -aardrijkskundig genootschap, pp. 399-429, M. Nijhoff, The Hague.

Rinnooy, N., 1882. Zeden en Gebruiken op Kissir Zuid-Wester-eilanden, Berichten van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging, Utrecht.

Rinnooy, N., 1886. Maleisch-Kissersche Woordenlijst, Tijd., vol. 31, pp. 149-213.

Rinnooy, N., 1886. L'ancienne sous-résidence de Kisser, Revue Coloniale Internationale, Tome Il. p. 42.

Rodenwaldt, Ernst, 1928. Die Mestizen auf Kisar Band I. Mit einem Beitrage von K. Saller ueber "Mikroskopische Beobachtungen an den Haaren der Kisaresen und Kisarbastarde", 2 vols, Mededeelingen van den Dienst der Volksgezondheid in Nederlandsch-Indie, G. Fischer, Jena.

Soares, Rosália E. M., 2015, The Textiles of Lautém, Timor Aid.

Soewarsono, 2013. Orang dan bahasa Oirata, sebuah historical context, in Revitalisasi budaya dan bahasa Oirata di Pulau Kisar, Maluku Barat Daya, Maluku, Soewarsono, Masnun, Leolita, and Nazarudin (eds), pp. 7-29, Jakarta.

Somba, Nethy Dharma, 2012. Ikat fabric, family self-esteem, The Jakarta Post, 5 May.

Stokes, John Lort, 1846. Discoveries in Australia, with an account of the Coasts and Rivers Explored and Surveyed during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle in the Years 1837, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, Volume 2, T. & W Boone, London.

Stöhr, Waldemar, 1976. Die Altindonesischen Religionen, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Vriese, W. H. de, 1858. Reis naar het Oostelijk Gedeelte van den Indischen Archipel in het Jaar 1821; door C. G. C. Reinwardt, Frederik Muller, Amsterdam.

Wedilen, Oni, 2011. Pulau Kisar (Yotowawa – Daisuli), [http://onekswedilen.blogspot.nl/2011/07/pulau-kisar-yotowawadaisuli.html, accessed on 14-1-2016.]

Wedilen, Oni, 2014. Kedatangan suku Woirata di Kisar, [http://oniwedil.blogspot.nl/2014/07/kedatangan-suku-woirata-dikisar.html#more, accessed on 14-1-2016.]

Publication

This webpage was firt published on 5th October 2017.