Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Geography

History

Ethnography

Kinship

Social Stratification

Marriage

Traditional Beliefs

The Cult of the Boat

Bibliography

Geography

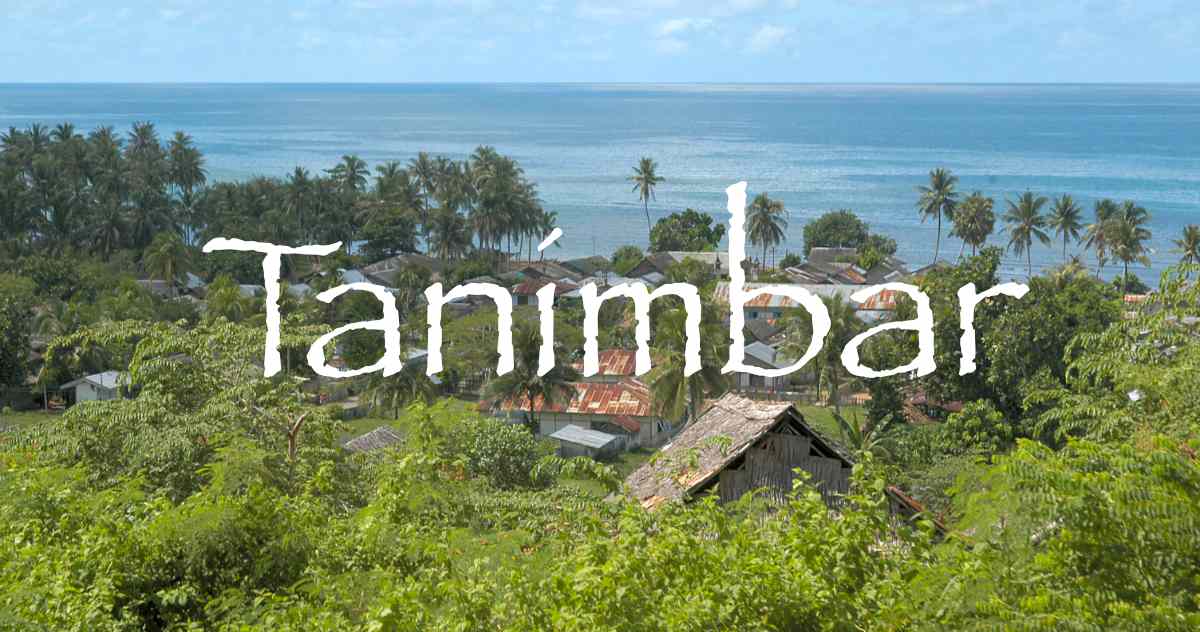

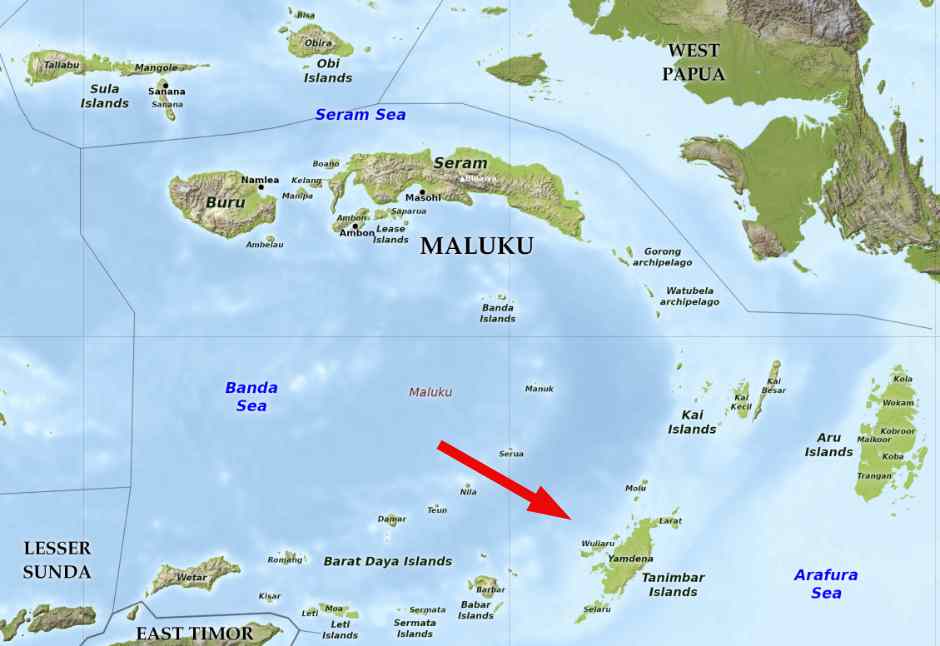

The isolated Tanimbar Islands lie just beyond the great arc of the Lesser Sundas Islands in the southern part of Maluku province, to the east of Timor Island and almost due north of Darwin, Australia. They consist of a group of about 66 limestone and coral islands that stretch some 220km from north to south and rarely exceed a height of 150–250 metres above sea level. To the west lies the Banda Sea, to the east the Arafura Sea.

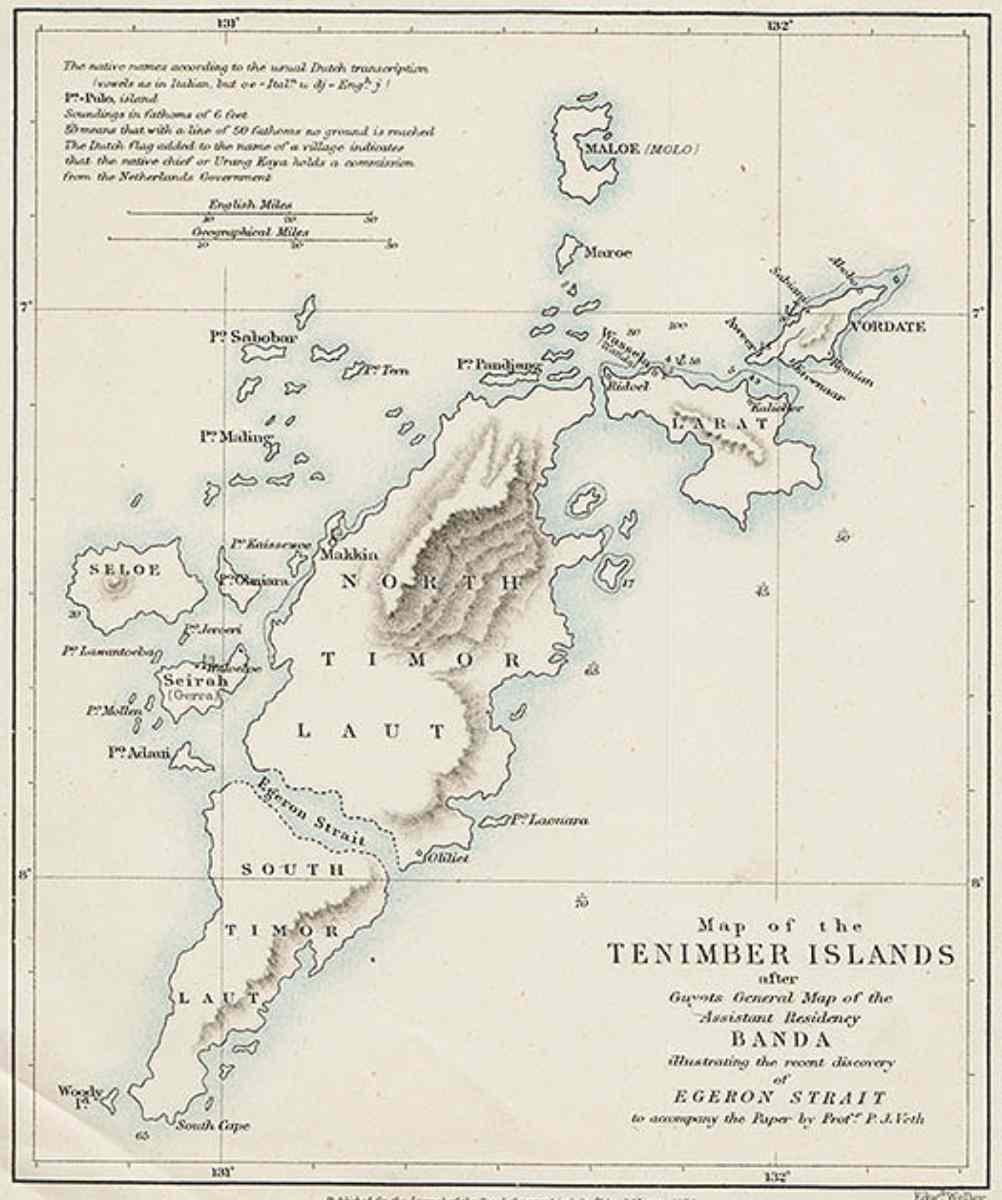

The Tanimbar Islands in southeast Maluku

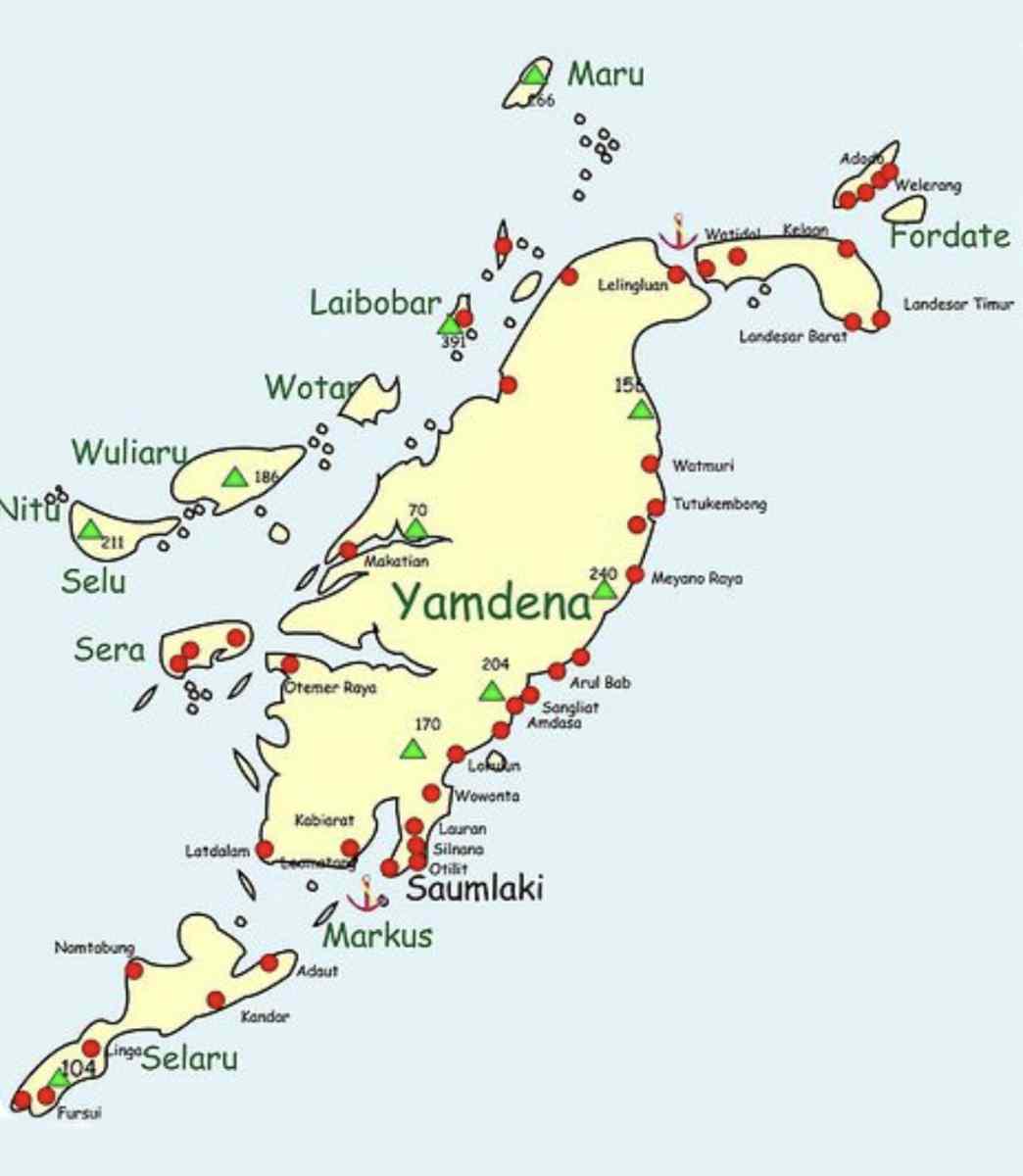

The principal islands are Yamdena (sometimes Jamdena), followed by Selaru then Larat, Seira, Selu, Wuliaru, Wotar, Laibobar, Maru and Fordate. The islands are forested but not as densely as those in central Muluku, which receive more rain. There are no rivers apart from a few small streams on Yamdena.

Fordate, Molo and Selu islands and the southeastern part of Yamdena are slightly uplifted compared to the rest of the archipelago, though do not exceed 240 metres in height. The exception is tiny Laibobar, which has two hills, the southernmost with an elevation of 390 metres.

Moluccans called Yamdena Timur Laut meaning ‘far east’, although this nomenclature was not used on Tanimbar. In the past, Europeans described Yamdena as Timor Laut.

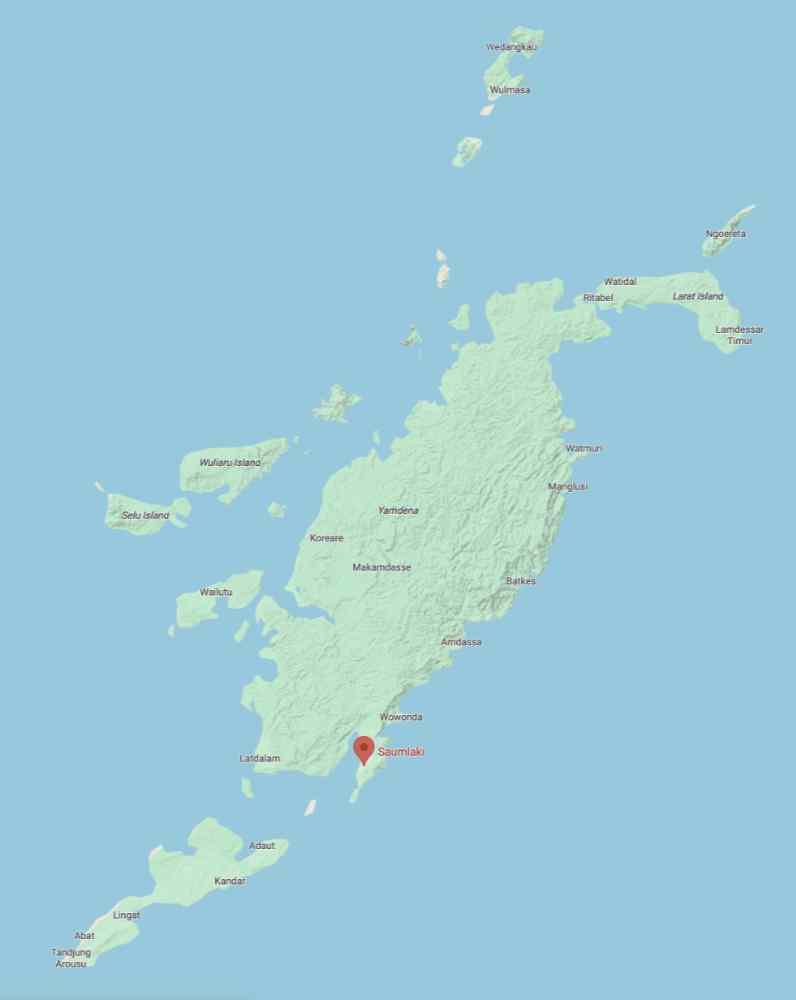

The main island of Yamdena has a range of thickly forsted hills along its eastern coast, which are under threat from commercial loggers. The western coast has a lower elevation. The majority of the population of 80,000 live along this eastern coast.

Topography of the Tanimbar Islands

Courtesy of Google Maps

Saumlaki is the chief town and main commercial port, located at the southern end of the island facing a sheltered inlet. From Saumlaki the main arterial road runs northwards close to the eastern side of the island, reaching the far north of the island and connecting up with the new 323-metre-long Leta Oar Ralan Bridge connecting Yamdena to Larat Island. The bridge was only inaugurated in January 2019. Mathilda Batlayeri Airport, named after a local heroin, is located 15km north of Saumlaki and has a runway that can take ATR-72 twin-engine turboprop aircraft. It is serviced by Wings Air and Garuda Indonesia flying from Ambon. There is a plan to make this an international airport connecting Saumlaki to Darwin, which are only 500km apart – some 45-minutes by air.

Above: An aerial view of Saumlaki

Below: The harbour at Saumlaki

The main market in Saumlaki, not far from the harbour

Politically the Tanimbar Islands are governed locally by the Tanimbar Islands Regency (Kabupaten Kepulauan Tanimbar), administered from Saumlaki. This was only created in January 2019. Prior to 2019, the archipelago formed part of Western Southeast Maluku Regency (Kabupaten Maluku Tenggara Barat).

Tanimbar Regency is divided into ten sub-districts (kecamatan):

| Tanimbar Selatan |

| Wertamrian |

| Wermaktian |

| Selaru |

| Tanimbar Utara |

| Fordate |

| Wuarlabobar |

| Nirunmas |

| Kormomolin |

| Molu Maru |

The total population in 2023 was 130,278, 30% of which lived in Tanimbar Selatan.

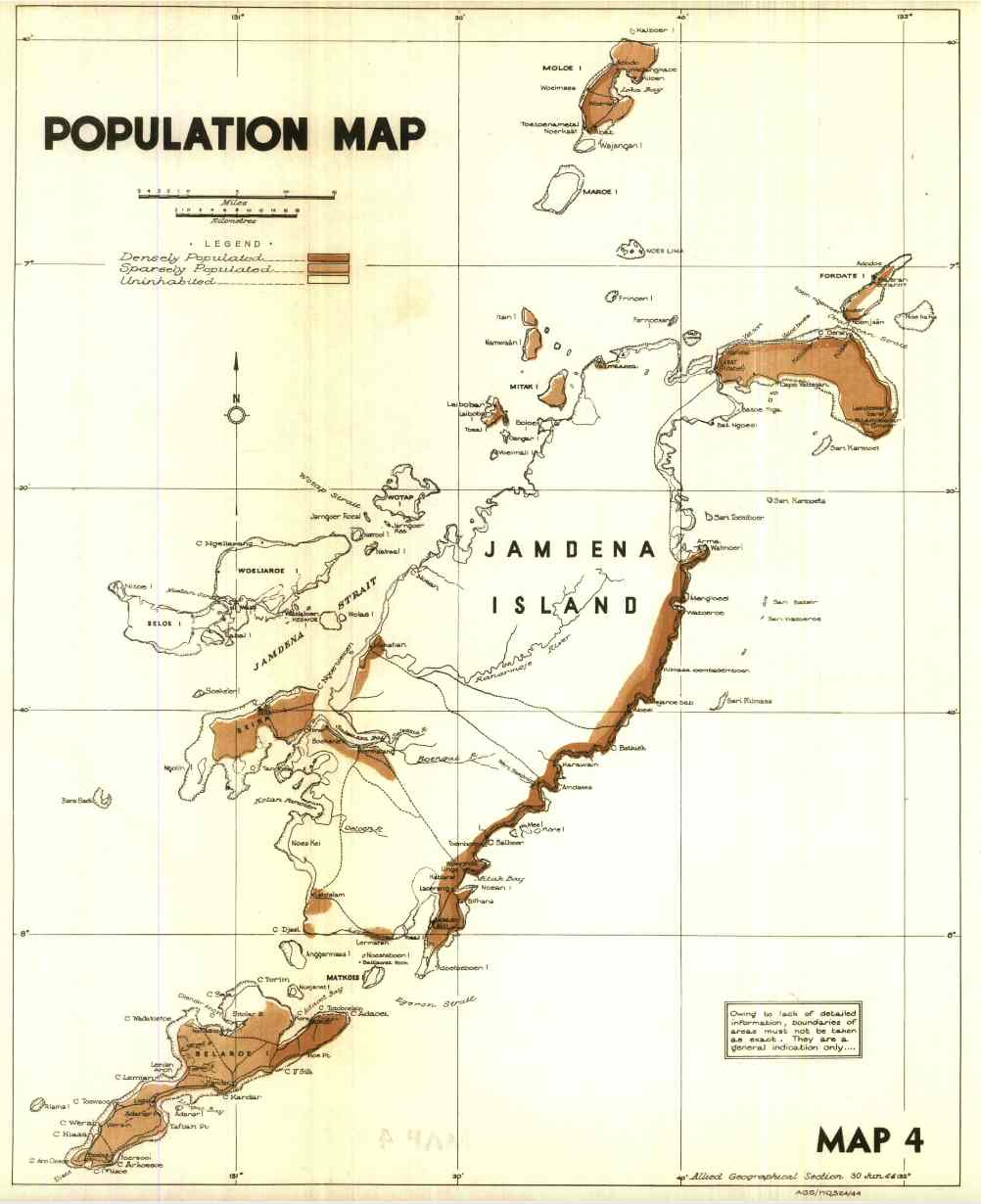

1944 map showing the uneven population distribution on Tanimbar

US Allied Geographical Section

Today, well over 70% of the population is Christian, with Catholics located in the northern part of the archipelago and Protestants predominating in the southern part of the archipelago. A government survey of population by religion in 2023 identified 65,004 Protestants and 5,397 Muslims but mysteriously no Catholics.

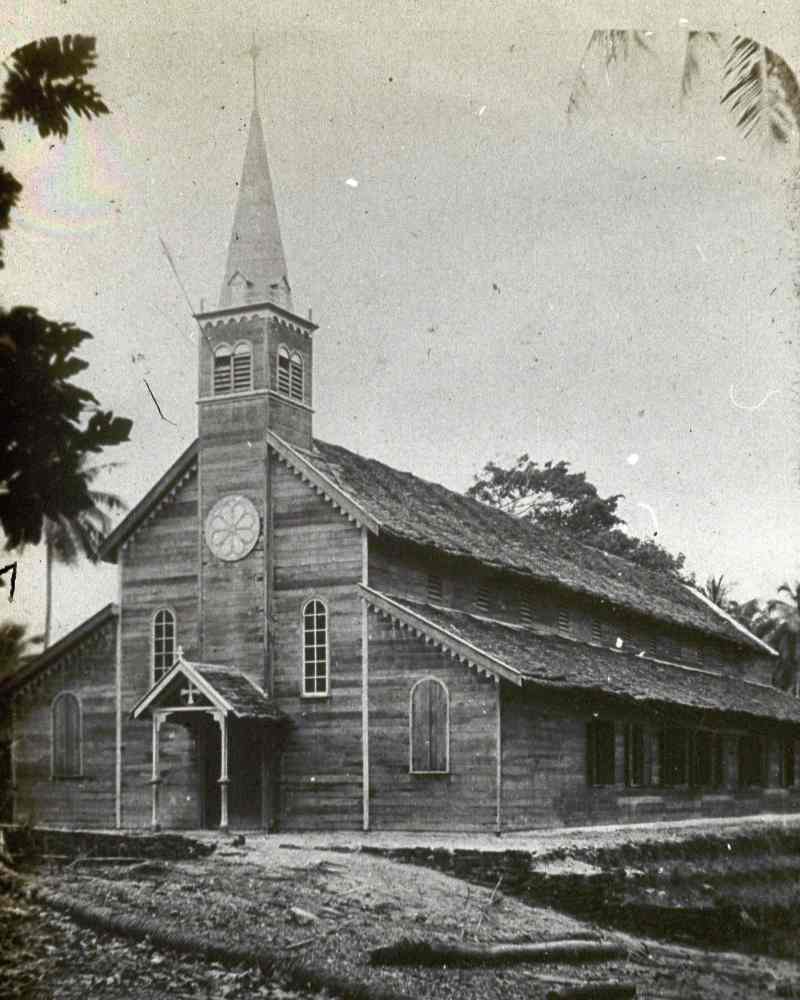

The Catholic church of Maria Bunda at Sangliat Dol

Return to Top

History

Recent archaeological research indicates that humans have occupied the Tanimbar Islands for at least 42,000 years (Kaharudin et al 2024). The rock shelter site at Elivavan on the south-west coast of Fordate Island contained evidence of two periods of human occupation, the first dating from around 42 to 32,000 years ago and the second from about 260 BCE to 1600 AD.

We know that modern humans had already reached many of the Lesser Sunda Islands some 40,000 years ago. On Flores, Liang Bua has provided evidence of modern human occupation approximately 47,000 years ago (Sutikna et al 2016), On Alor, Makpan, has an occupation age of 40,000 (Kealy et al 2020), while on Timor archaeologists have discovered four sites with records dating greater than 40,000 years: Laili (44,000), Matja Kuru 2 (44,000), Asitau Kuru (42,000), and Lene Hara (42,000) (Hawkins et al 2017; O’Connor et al 2010; Samper Carro et al 2023; Shipton et al 2019; and Shipton et al 2024).

These findings show that there was a rapid dispersal of modern humans across the Indonesian archipelago. Unlike the Lesser Sunda Islands, the Tanimbar Islands have been permanently isolated by a sea barrier long before the earliest human occupation in Wallacea. As Kaharudin et al point out, given the risks involved in reaching Tanimbar, the development of advanced maritime technology and the availability of predictable food resources would have been a necessity for successful colonization.

We know nothing about the history of pre-colonial Tanimbar. The first colonial power to reach Tanimbar was Portugal. After conquering Malacca in 1511, Alfonso de Albuquerque dispatched three small ships to explore Maluku, which reached Banda, Ambon and Ternate the following year. By 1513 a trading fleet from Portugal began visiting the Spice Islands annually. It is likely that the Portuguese located the Tanimbar Islands not long after. One possible early visitor may have been the Portuguese official Martim Afonso de Melo (Jusarte) who wintered in the archipelago around 1522–1525.

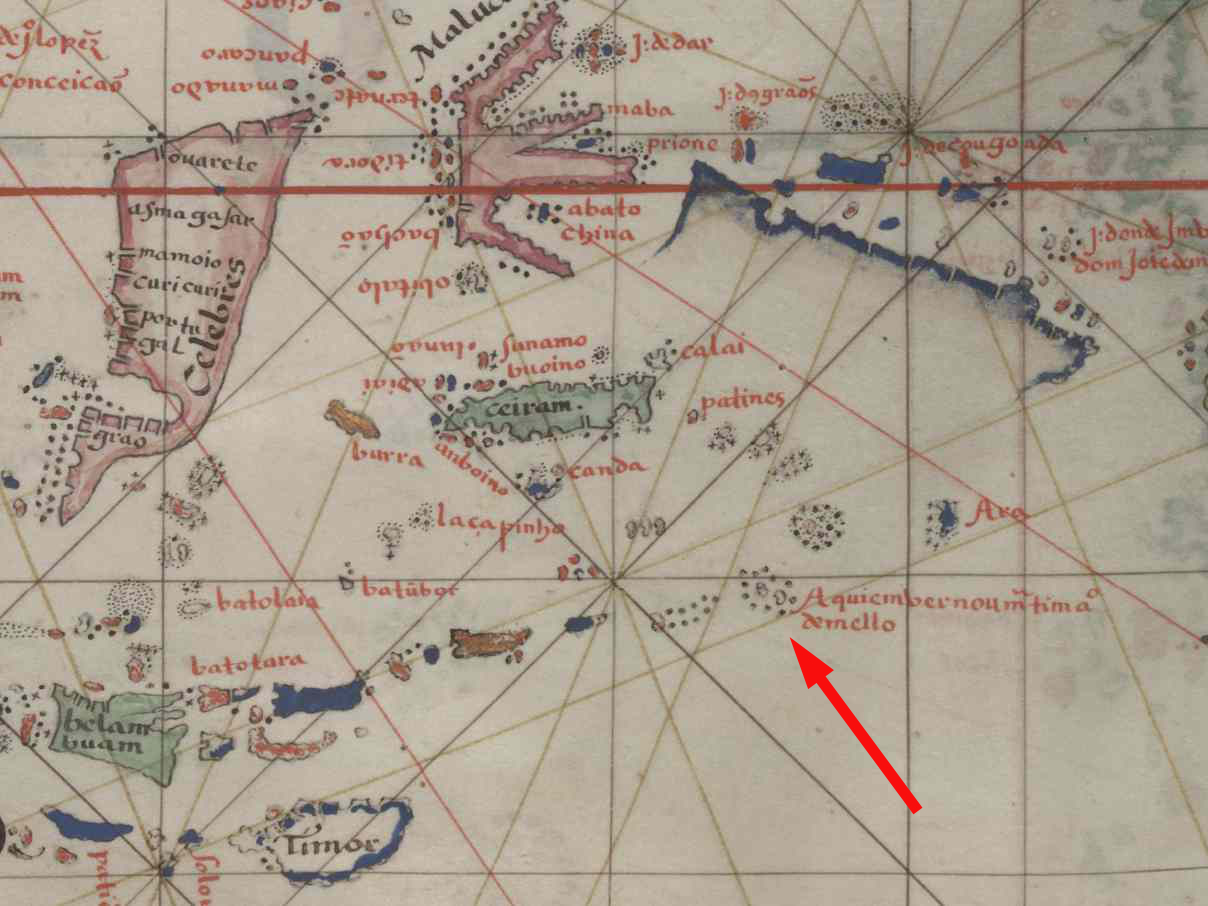

The islands of Maluku from the 1560 map of Bartolomeu Velho, with the Tanimbar Islands highlighted with the phrase Aqui in bernon Martin Afonso de melo [Here wintered Martin Afonso de Melo]. Image courtesy of the Huntington Digital Library.

In 1623, two Dutch yachts, the Pera and the Arnhem, were sent from Ambon to New Guinea and the South Lands with instructions to visit the islands of Kei, Aru and Tanimbar, and to enter into friendly relations with the inhabitants (Tent 2022, 18). A third yacht, De Mus, arrived at Tanimbar and after several days some 60 local villagers appeared on board under the pretence of trade and attempted to murder the crew with knives and clubs and to take control of the boat. They were eventually driven off leaving two dead crewmen and many injured (Drabbe 1940, 10).

Later, in 1636 two yachts, the Cleen Amsterdam and the Cleen Wesel commanded by G. Thz. Pool and carrying the Dutch merchant Pieter Pieterszoon passed briefly through ‘Temember’ (the Tanimbar Islands) on his return voyage to Banda from the northwest coast of Australia. They reported that on Timor Laut, sandalwood, sheep, coarse cattle, and other useful items were present.

The yacht Petten passed the islands of Tanimbar and Timor Laut in 1639 on its way to Banda. They found a fairly high and populous land, well-cultivated and suitable for human habitation. The principal useful trade commodities found there were rice, paddy, slaves, and turtle shell (Drabbe 1940, 10).

In 1645 and 1646 the merchant Adriaan Dortsman made two journeys to Tanimbar, establishing a lodging house on Fordate. In 1647 he concluded the first official contact between the Tanimbarese and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) establishing an ‘exclusive contract’ with the village heads and elders of Timor Laut, Larat, Sera and Selaru covering the trade in slaves, tortoiseshell, shark fins, ambergris, wax, and sapan wood (Riedel 1886, 276; Drabbe 1940, 10). The Dutch established a fort with a manned garrison at Rumya’an on Fordate and began trading in slaves, tortoiseshell and shark fins. A Protestant missionary also arrived to begin converting the natives. However, trade with Tanimbar failed to prosper, thanks to competition from Bandanese traders and predation by local pirates. It soon dwindled and was finally terminated in the mid-eighteenth century. The fort fell into ruin and the Dutch departed.

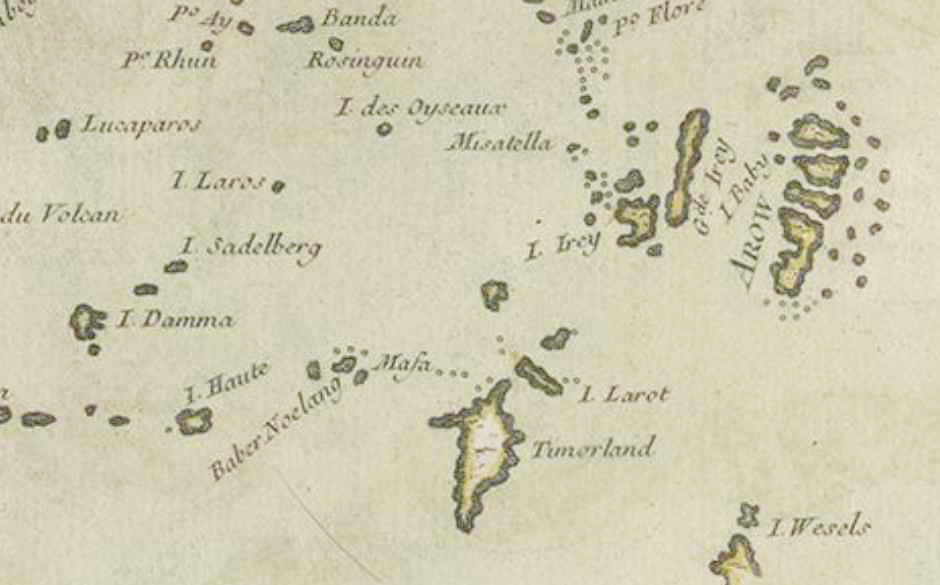

Above: The Tanimbar archipelago shown on a map of the Isles Moluques by George Louis Le Rouge 1756. Yamdena is labelled Timorland and Selaru is missing

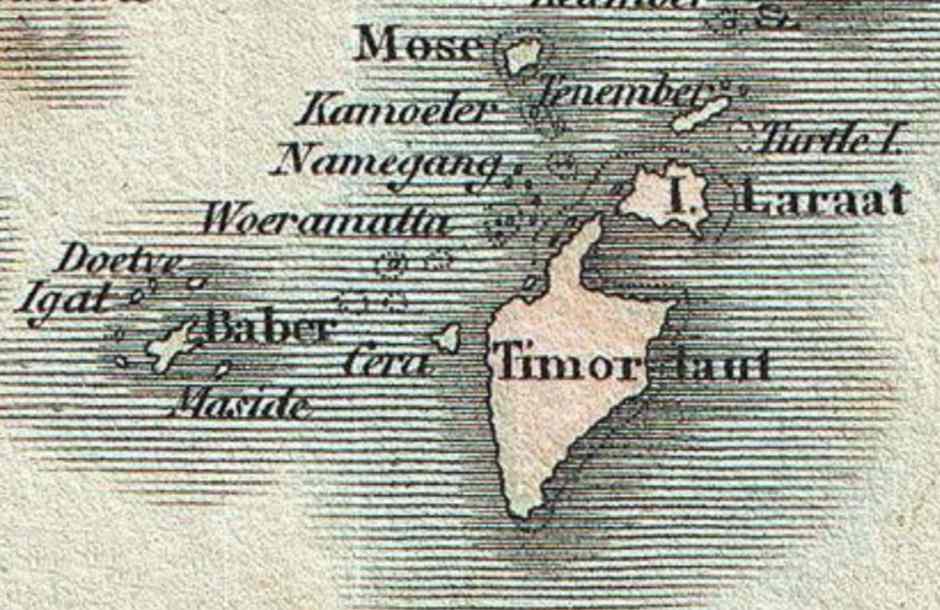

Below: The Tanimbar archipelago shown on the 1801 map of John Carey, London. Yamdena is labelled Timor laut and Selaru is missing

In the nineteenth century the south Moluccas were frequently visited by British vessels on their way to the north coast of Australia. In 1824 a British trading schooner from London, the Stedcombe, stopped at Larat Island in an attempt to trade weapons for livestock. While the captain and ten of his crew were ashore, the villagers attacked the ship and murdered all of the crew apart from two ship’s boys, thanks to the intervention of the local women. The boat was plundered and then set on fire. One boy did not long survive but the other, Joe Forbes aged 14, was enslaved as an agricultural labourer for the next 15 years. He was finally rescued in 1839 by another English vessel, the Essington, captained by Owen Stanley.

Despite the fact that the Dutch still regarded these islands as Dutch territory, they were not visited again until 1825-26 when the Dutch Brig-of-War Dourga captained by Lieutenant D. H. Kolff called at Fordate, Larat, Yamdena and Sera. He had been sent from Ambon to visit all of the islands located between Timor and New Guinea with orders to discover what remained of the forts erected by the VOC, especially those of Aru, Tanimbar and Kisar, and to renew friendly relations with the natives. Kolff first visited the village of Watidal on Larat, located on a limestone hill. He noted:

These villages present a very picturesque appearance: they consist, according to their population, of from twenty to fifty houses, erected near each other, upon piles from six to eight feet high. These dwellings are from twenty to twenty-five feet long by twelve to fifteen broad. They are enclosed on all sides, and have a couple of long holes cut in the walls to serve for windows. The roofs are covered with a thatch of palm leaves, these being first arranged on small sticks, and then placed neatly on the roof, overlapping each other. The interior is usually kept in good order; but every part is blackened with smoke from the fires they employ in cooking their provisions. The house is entered by a door in the centre of the floor, to which the inhabitants ascend by means of a ladder. Against the wainscoat, immediately fronting the door, is placed a small scaffold of carved wood, having upon it a large dish, containing the skull of one of the forefathers of the owner of the house, whose weapons are also hung around it.

From Larat the Dourga sailed to the islands of Timor Laut (Yamdena), Maling, Laboba and Wau, meeting the various village chiefs. The crew then headed for the village of Maktia on Yamdena, not far from Sera. After going ashore, the landing party were attacked with arrows and one of the seamen was wounded and subsequently died.

After visiting New Guinea, the Dourga revisited the Tanimbar Islands, stopping at Fordate and Sera.

Timor Laut was briefly visited by Captain Owen Stanley abord the Essington who sailed from Port Essington in March 1839. He wrote that they arrived to encounter:

... shores fringed with impenetrable mangroves, the natives black, the lowest in the scale of civilised life. We landed on a beach, along which a luxurious growth of coconut trees extended for more than a mile, under the shade of which were sheds neatly constructed of bamboo and thatched with palm leaves, for the reception of their canoes. To our right a hill rose to a height of 400 feet covered with brilliant and varied vegetation so luxuriant as to entirely conceal the village (Olilet) built on its summit. The natives who thronged the beach were of a light tawney colour, mostly fine athletic men with an intelligent expression of countenance.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Tanimbar suffered dreadfully from an outbreak of small pox which killed half of the population. It then suffered from a further outbreak of smallpox in the early twentieth century (Goudswaard 1863, 101-103). There was also a cholera outbreak around the same time.

In 1877 the steamer Egeron belonging to some Banda traders and captained by a Mr Herzog visited Timor Laut and reported that the island was divided into two parts by a channel which they named the Egeron Strait (Caarten 1878). We now known that the strait separates Yamdena from Selaru to its south. The crew traded with some of the kampongs located close to this strait. The strait was shown on a map that divided Timor Laut into a northern and a southern island.

Map of the ‘Tenimbar Islands’ by J. Murray, published by the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society 1878.

Eventually in 1882 the Dutch Resident in Amboina, J. G. F. Riedel, decided to bring Tanimbar under regular Dutch administration by sending two posthouders to Tanimbar – one to Sera the other to Larat. They were both Protestants from Ambon. It was little more than a gesture. At that time Larat was embroiled in a civil war between the three western villages and the three eastern villages. and the Dutch posthouder proved totally ineffectual in stemming the conflict.

That very same year, the Scottish explorer and naturalist Henry Ogg Forbes and his new wife Annabella arrived in Ritabel on Larat Island on the steamer Amboina. As they approached the island, Forbes described its appearance:

I observed that the much-indented coast, a low and narrow foreshore covered with a thick forest of coconut trees and dark green mangrove thickets, was fringed in most places with a precipitous bluff, on which principally the villages, whose houses glinted through the vegetation above them, were situated. At midday we entered a narrow straight between the mainland and the island of Larat, and anchored opposite the village of Ritabel. As soon as we had made fast, several boats – the foremost of them rather timidly – put out from both shores, and in a few minutes we were surrounded by a little fleet, whose occupants scrambled on board, talking and jabbering as only Papuans can, affording us an opportunity of forming some opinion of those who were to be our friends or foes for the next three months. They were powerful athletic fellows, and conducted themselves exceedingly well, apparently awed by what they saw on board of the marvellous things of civilisation. Their soul request was for laru or gin, the most-prized by them of all earthly commodities.

The visitors were welcomed by the new posthouder who was accompanied by his wife and two policemen. The Forbes’ objective was to catalogue the island’s flora and fauna but their explorations were heavily constrained by local inter-village warfare. Ritabel was encircled by a high palisade, outside of which the ground was covered by sharpened bamboo spikes save for a single narrow footpath. When they climbed up to the nearby village of Ridol they found it abandoned and half-burned to the ground with recently-gibbeted human heads positioned nearby and a human arm hanging from a tree. They stayed on the island for just three months before returning to Ambon.

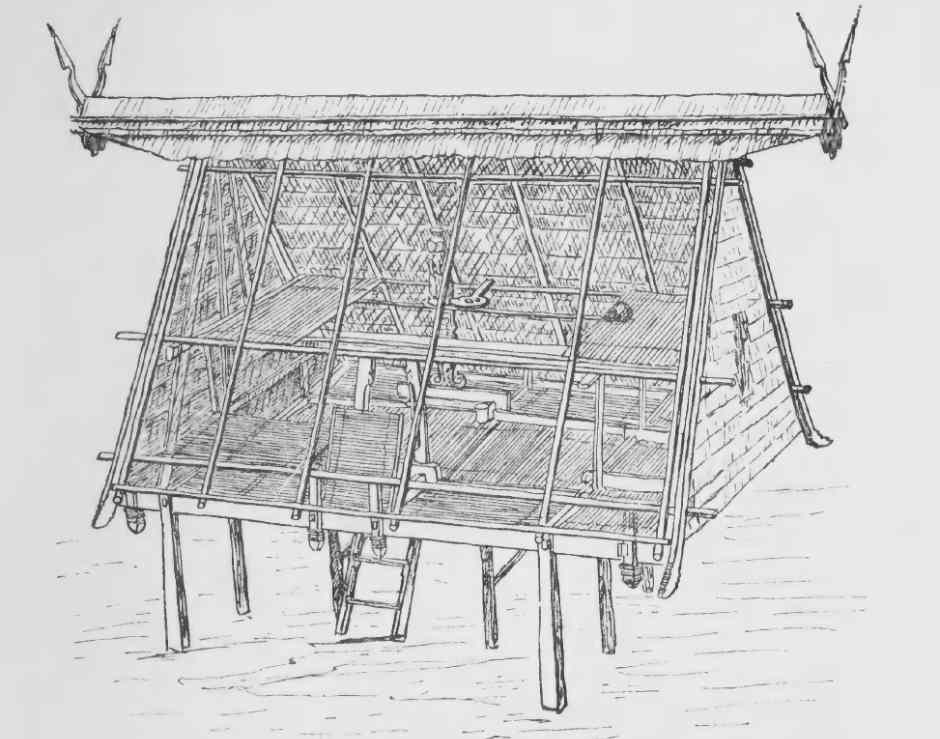

A house in Timor Laut with its roof removed to show the interior (Forbes 1885, 319)

Other reports dating from the nineteenth century suggest that many other kampongs were permanently engaged in inter-village warfare, with head-hunting raids instigated by disputes over the ownership of land and reefs, inter-village thefts, adultery and murder (Forbes 1886, 25 and 55; Jacobsen 1896, 209). For defensive purposes, villages were located on cliff tops enclosed by stone and cactus walls with an outer perimeter of upturned bamboo spikes.

Riedel left us an account of the fortifications around some of the villages on other Tanimbar islands:

On the islands of Yamdena and Selaru, fear of enemy attacks means that villages are built by deliberately on the peaks of raised coral rocks, up to 120 metres above sea level. Here access is provided by heavy wooden ladders (ret) about two metres in width. In times of war, these ladders are dismantled and stored in the village. These villages, the largest of which contains 80 big wooden houses standing on piles two to three metres high, are surrounded by heavy walls of stacked coral stones, and further protected by palisades of thorny bamboo, while on the seaward side they are usually shielded by Pisonia alba trees (Riedel 1886, 285).

The Norwegian ethnologist and collector Johan Adrian Jacobsen led an expedition to the Banda Islands in 1887-88, tasked with collecting ethnographical artefacts for the Museum fur Völkerkunde in Berlin. In June 1988 he reached Ritabel on the western tip of Larat where he stayed for about ten days. He had been warned about the dangers of inter-village warfare but found the villagers friendly and welcoming. He suggested that one reason for the violence may have been the heavy consumption of distilled palm wine. Jacobsen spent much of his time collecting some 600 carvings, weapons and other ethnographic artefacts from the villagers. Just before departing for Sera, he was told that warriors from the island of Maulo [sic] were moored behind a nearby island, clearly intent on attacking Ritabel to take revenge for the loss of nine of their men in a previous skirmish. Thanks to a nearby storm, the invasion had been halted.

Because of the storm Jacobsen had a difficult voyage to Sera to visit the Dutch posthouder. The village was surrounded by foot traps – planks of wood studded with needle-like spines designed to trap night-time attackers. He spent one week on Sera before sailing on to Dammar.

In 1892, the kampongs of Olilit and Rumjaan were partly destroyed by fighting while in 1896, the kampong of Kamatubun on Sera was attacked by the Javanese. The posthoulder had only two guards for protection and fled to Adaut. In 1902, Otémar was burned down by attackers from Java and Ceram.

In 1900, the Resident of Ambon, J. H. de Vries, described the village of Lermatang Kort in southern Yamdena:

It is built on a high rock plateau, with sharp drops on all sides. From the sea side in particular it is unscalable, so a tall wooden staircase or ladder consisting of several sections is installed. In wartime these sections are hauled up, completely severing the link with the outside world. The ladder leads to a gate which provides access to the village. The gate is set in a wall of stacked stones, mounted by a fence of thick upright bamboo carved at the top into sharp spikes. Cross-beams reinforce the whole structure. The gate itself is so narrow that only one person can pass through at a time. Opposite it on the landward side is a second gate, also with a ladder. These two gates are the only ways into the village (De Vries 1900, 494).

The remains of a wall around kampong Omtufu on Yamdena photographed by Petrus Drabbe around 1920. Image courtesy of KITLV.

In 1910, the Catholic authorities were looking for a location to establish a mission on the southwestern coast of New Guinea. By chance they encountered the gezaghebber of Babar and Tanimbar, E. G. E. P. von Heijden, who suggested they consider the east coast of Yamdena, where some Protestant teachers had worked previously but had left due to the ‘wildness of the population’. Later that year, two priests were despatched to the island with two assistants and two houseboys. J. Klerks chose to settle in Olilit while E. Cappers settled in Lauran, both opening schools shortly afterwards. One year later they opened a third school in Sangliat (Steenbrink 2007, 216).

In 1911 the Dutch installed an Ambonese official as posthouder in Olilit accompanied by around 20 soldiers. That same year a Protestant teacher opened a school in Olilit. At the year end, some Olilit villagers attacked the government post, injuring some soldiers and the new teacher. The Regent of Ambon responded in early 1912 by despatching Lieutenant van den Bossche with a party of about 40 infantrymen to subdue the population. He waged an extremely violent campaign against the local leaders, exiling 70 of them to Ambon. At long last the Dutch had gained a modicum of control across the entire archipelago which inevitably led to an upsurge in missionary activity.

In 1915 the Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC) posted 28-year-old Petrus Drabbe to Tanimbar. He had been ordained in Tilberg in 1911 and in 1912 began his missionary work in the Philippines. Drabbe was not just a priest but was a talented linguist with an interest in the customs of the local people. As he familiarised himself with the native people, he realised that major changes were underway. Faced with the influence of European colonialism and religion they were not just abandoning their traditions but were disposing of their material culture, including items inherited from their ancestors. He set out to document as much as he could of their pre-colonial ways.

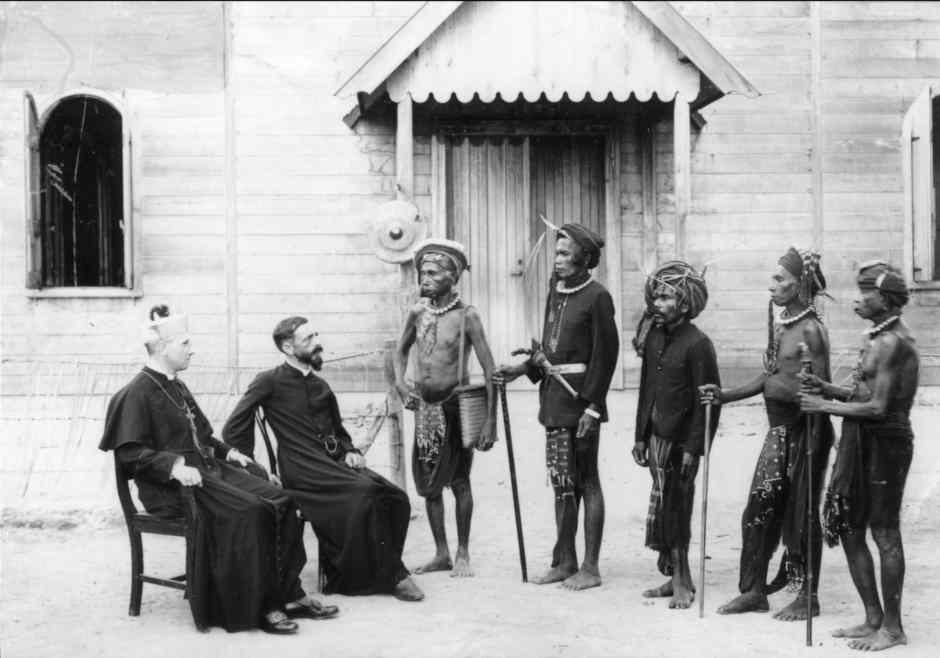

Vicar Aerts and Father Drabbe talking to village heads on Fordate, 1922

It was not until 1927 that he formulated a strategy for his project, returning to the Netherlands to consult the Amsterdam anthropologist Johan Christiaan van Eerde at the Colonial Institute. On his return he embarked on an eighteen-month trip on horseback, armed with a professional camera. He left us with a significant photographic archive and an ethnographic manuscript entitled Het leven van den Tanémbarees (The life of the Tanimbarees), which was published in Dutch in 1940. It covered everything about life on Tanimbar in great detail.

Father Drabbe on horseback, around 1930. KITLV, Leiden University Libraries

Drabbe recorded that for defensive reasons, most of the traditional villages were built on a rocky promontory projecting into the sea, with one, two or even three sides sloping steeply towards the beach and the sea. These generally provided a site for the village around 100 to 300 metres square. The village was enclosed by a wall of coral rocks roughly two metres high. This was a safety measure. The original access to the village from the sea side was a staircase. At the top was often a beautifully carved gate. In times of war, they were replaced by a door fastened with a bolt.

Above: Steps leading from the beach up to a village, photographed by Drabbe

Below: Steps leading up to kampong Sangliat Dol on Yamdena

In many places, densely grown cacti or thistles made the wall inaccessible and in times of war it was fitted with a defensive upper fence of bamboo, with halved bamboo poles with sharply pointed ends and with the twigs still on them standing upright to create an impassable barrier.

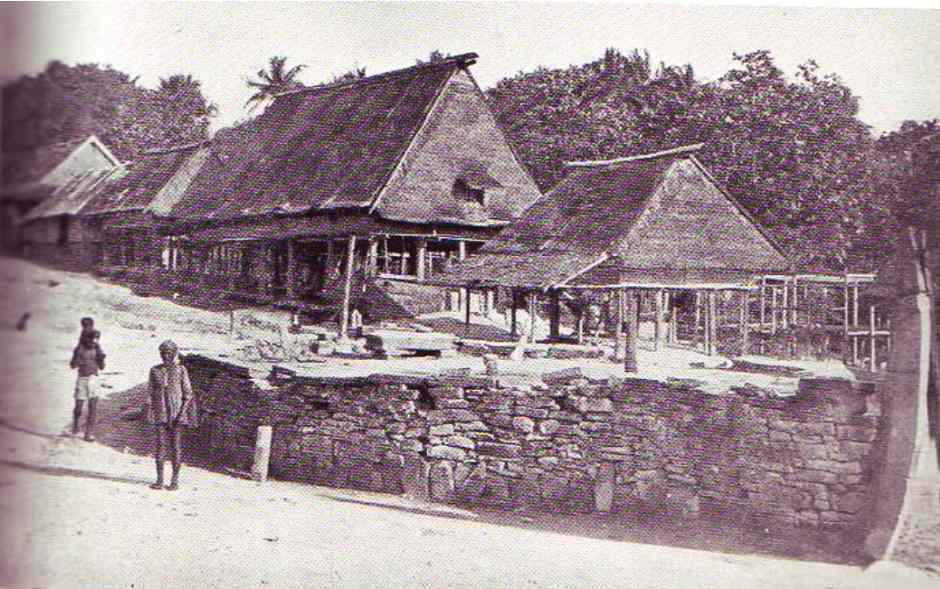

Houses in a Tanimbar village photographed by Drabbe.

During Drabbe’s twenty-year sojourn on Tanimbar the Dutch brought about major changes to local life. Both Catholic and Protestant missionaries began to open schools in an increasing number of villages, and baptising villagers who were willing to convert. The gezaghebber E. Kromme claimed by 1921, every village had a school. He reported that across the whole of the Tanimbar and Babar Islands, the Protestants had opened 78 schools and the Catholics 23.

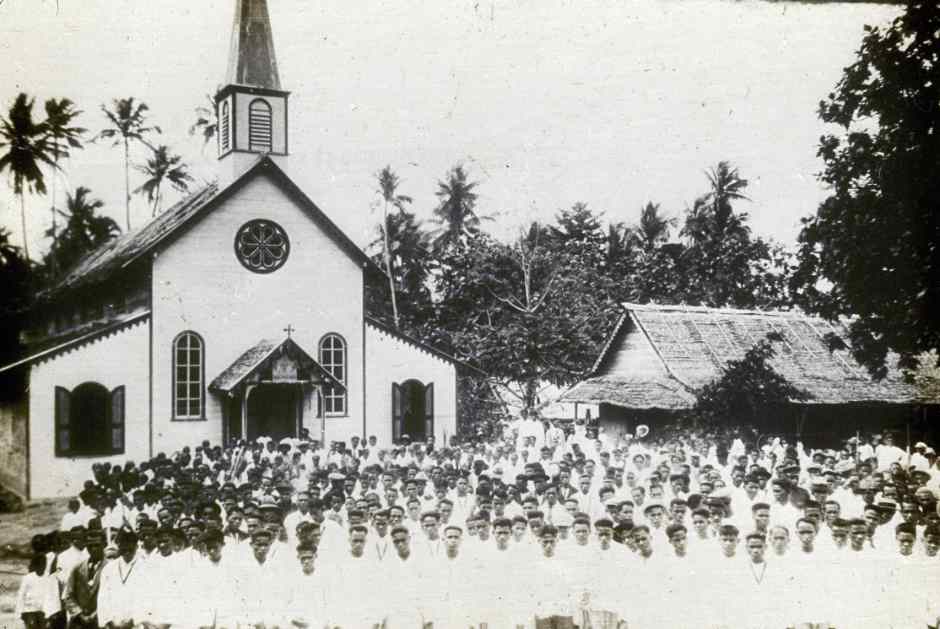

Worshippers outside a Roman Catholic church in a village on the Tanimbar Islands photographed by Drabbe. Courtesy of KITLV Libraries.

With the Dutch authorities outlawing inter-village warfare, they ordered that all of the defensive walls should be demolished. Extended families were forced to move from their large longhouses into separate houses for each nuclear family. Over time, villagers came down from their fortified cliff-top villages to build new villages closer to the beach, many incorporating a Christian church. The former villages progressively became sacred ceremonial sites. Writing in 1931, Drabbe claimed there was no more trouble on any of the Tanimbar islands.

The modern village of Lauran in southeast Yamdena photographed by Drabbe

Return to Top

Ethnography

Despite the existence of four languages across the islands (Yamdenan, Fordatan, Selaruan and Seluwasan), the Tanimbarese share a remarkably uniform culture which differs markedly from that of the neighbouring islands.

As already mentioned, the first ethnography of the Tanimbarese was penned by the Dutch Catholic missionary Petrus Drabbe, who spent 20 years on the islands and described the pre-Christian culture of the 1920s and 30s. More recently, some aspects of Tanimbar social life were discussed by F. A. E. van Wouden in 1968, but more widely by Simonne Pauwels in 1985 and by Susan McKinnon in 1990 and 1991.Return to Top

Kinship

Tanimbar has a house society, with every person belonging to a specific named house. On Yamdena a house is called a das. Each house is identified by two founding ancestors: the ancestor who founded the house and the ancestor who gave the first wife to the house (Pauwels 1985, 132). If two houses are linked by a marriage, the wife-giving house is called the nduan while the wife-taking house is the uranak.

In addition to belonging to a house, children are born into the clan of their father, known as tnjame-matans (literally ‘source of food’) or soens (Drabbe 1940, 148). These clans are exogamous. On Fordate, a clan is called a rahan-ralan. The head of the clan is the first-born male descendant whose lineage goes back to the first chief.

Several clans can unite to form a village or pnoewe, or to form a tribe, suan. In the language of Fordate, a village is an ahoe and a tribe is an aroen.

To be a village (pnoewe or ahoe) it is necessary for the clan leaders to have their own meeting place or clan house (kejain).

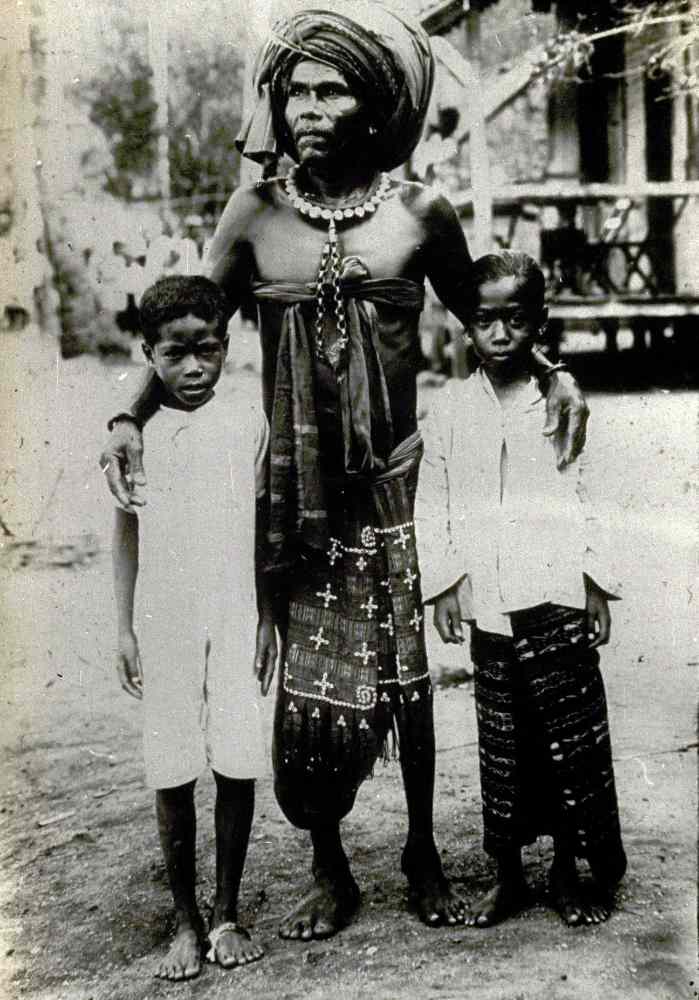

A grandfather and his two grandchildren photographed by Drabbe

Return to Top

Social Stratification

The traditional social structure of Tanimbar was hierarchical. Society was divided into the upper class, the nobility (mele or mela), the commoners (jamoedi), and the lower class (famoedi), whose members were formerly considered slaves (Drabbe 1940, 179). Slaves were people who had fallen into debt or war captives, although most warriors captured in inter-village wars were killed.

Membership in the first two classes is reflected in membership in "named houses" and "unnamed houses." According to McKinnon (1991, 105), a kind of "older-younger brother" relationship exists between the two classes. However, membership in a social class is not fixed, but can change, for example, if the bride price is not fully paid. Associated with the named houses are land ownership rights and the right to participate in matters of adat (right of use) in the village assembly.

In pre-colonial times, discussing these legal issues was the sole activity of male members of the upper class. Hunting, fishing, and tending gardens were the responsibility of the commoners and slaves. Today the distinction between the classes is less pronounced, apart from regarding matters of adat (McKinnon 1991, 106).

Marriage

On Tanimbar, houses are exogamous – young people should not marry a partner who belongs to their own house. The ideal is matrilateral cross-cousin marriage, where a young man marries his mother's brother's daughter, or inversely, a young woman marries her father's sister's son.

Basically, there are two types of marriage:

- The first is called the marriage with a bat nduan, a ‘nduan woman', meaning a woman from the wife-giving house. In such a marriage a man marries a woman belonging to a house with which his house has a long-term marriage alliance.

- The second is called the marriage with a bat waljéte, a ‘stranger woman'. In this case a man marries a woman who belongs to a house with which his house has not yet established a marriage alliance.

Drabbe noted that in most cases there was no pressure on a young man to marry a particular girl. However, there were instances where a person was forced to submit to the will of his parents. In extreme cases, a person who was unwilling to follow his or her parents’ choice of partner was killed (1940, 191).

Both types of marriage require a two-way exchange of goods between the house of the wife-takers (the uranak) and the house of the wife-givers (the nduan). The house of the wife-takers (the uranak) gift male earrings (lelbutir), breastplates, elephant tusks, antique swords, meat (pork), fish, and palm-wine to the house of the wife-givers takers (nduan). This is known as béli or bridewealth.

Meanwhile the wife-givers gift gold kmena-type female earrings, necklaces, bracelets, sarongs, loincloths, and rice to the wife-takers. This is known as adornment. The textiles could be locally made or imported from neighbouring islands such as Babar.

Return to Top

Traditional Beliefs

In Drabbe’s time, many Tanimbarese still followed an earlier faith, believing in a supreme being. This god was referred to by many names such as Mele (Noble One), Ratu (the great, the exalted), Ratu das (God above), or Ratu-desar (God himself) on Yamdena or Ubila’a (Supreme Ancestor or Grandparent) on Fordate (Drabbe 1940, 424; McKinnon 1991, 42–45; Pangemanan 2014, 201). Another term for God is Limnditi-Fendéoe, the literal meaning of which is unknown.

This supreme being encapsulated male and female, sun and moon, and heaven and earth. It was omniscient, having power over life and death and strict justice.

This existence of this pre-colonial belief made it easier for missionaries to convert the Tanimbar people to the idea of a Christian god (Pangemanan 2014).

A new Catholic church on one of the Tanimbar islands photographed by Drabbe

Return to Top

The Cult of the Boat

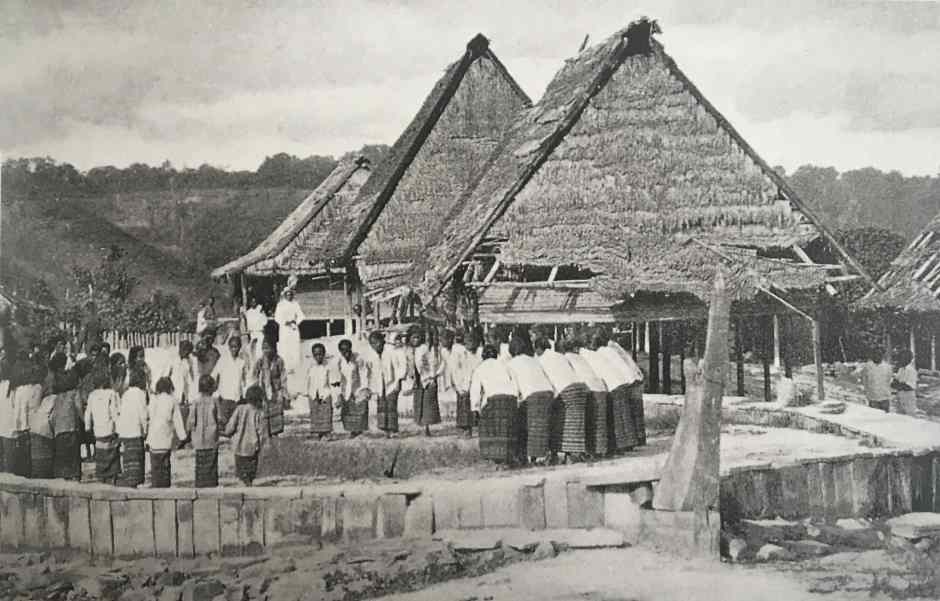

The cult of the boat remains a common feature of many facets of Tanimbarese culture. Indeed, oral legends recount how the ancestors originally arrived by boat from the southwest. Traditional villages were centred on an oval of stones, called a natar on Yamdena or a didalan on Fordate, sometimes formed into the shape of a boat. Those at Sangliat Dol and Arui even have finely carved stone prow and stern boards, while the platform at Olilit is embellished with an old Dutch anchor and chains. The boat-shaped natar or didalan included a stone altar dedicated to the supreme deity, Ratu or Ubila'a. It was here that ritual officials had their stone seats and it was here that offerings were made to Ratu or Ubila'a in connection to events that unified the village, such as head-hunting raids, warfare, inter-village alliances, and epidemics.

Above: A stone boat-shaped platform photographed by Drabbe in 1940

Below: The stone boat at the clifftop villager of Sangliat Dol, known as Natar Sori

A computer model of the elliptical stone boat at Sangliat Dol. It is 18 meters long by 10 meters wide and filled with earth to form a raised ceremonial platform.

Women dancing on a stone boat in Arui-Bab in east Yamdena in around 1930

In ritual songs, the name of the stone boat is used as a metaphor for the village, which traces its origin to distant islands, often to the southwest. The community itself is also linked to the concept of a boat, with certain ritual officials forming its crew. One is known as the 'bow of the boat', another as the 'middle' and a third as the 'stern'. In a ceremony aimed at renewing the intervillage alliance, villagers perform a dance in which the participants are arranged as if on the deck of a boat. Some dancers even represent the sail, others the frigate birds flying overhead!

The layout of the villages, which often consisted of only a few houses, were also designed as a boat, just like the houses themselves.

Houses were traditionally laid out in rows that ran landward from the sea with their entrances facing the village square. Inside immediately facing the entrance was the altar panel, the tavu dardarin, a finely carved human-shaped figure with upraised arms representing the founding ancestor. The skulls of the family's ancestors were placed on the roof beam above it. The house with the tavu at its heart was the ritual centre. Offerings were, and still are, made in front of the tavu altar to Ratu/Ubila'a and the ancestors for almost every family event, from birth to death as well as for the onset of an illness, starting a new garden, or building a house or boat.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon 1944. Area Study of Tanimbar Islands, Terrain Study 87, Allied Geographical Section, US General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area.

Barbier, Jean Paul, and Newton, David, 1988. Island and Ancestors: Indigenous Styles ofSoutheast Asia, Prestel, Munich.

Brandl-Straka, Ursula, 2009. Früher hatten wir so etwas – heute nicht mehr, Konflikte, Mächte, Identitäten: Beiträge zur Sozialanthropologie Südostasioens, pp. 65-86, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien.

Caarten, P. Bicker, 1878. Voyages of the Steamer ‘Egeron' in the Indian Archipelago, including the discovery of Strait Egeron, in the Tenimber, or Timor Laut Islands, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 48, pp. 294-310.

Dasfordate, Aksilas; Winoto. Darmawan Edi, 2022. Traditional Government System in Tanimbar, International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 434-444.

De Jong, Nico, and van Dijk, Toos, 1995. Forgotten Islands of Indonesia: The Art & Culture of the Southeast Moluccas, Periplus, Hong Kong.

Drabbe, Petrus M. S. C., 1940. Het leven van den Tanémbarees, Ethnografische studie over het Tanémbareesche volk, Verhandelingen Bataviaasch Genootschap, vol. 71, part 2. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Drabbe, Petrus, Etnografi Tanimbar Kehidupan Orang Tanimbar Di Zaman Dulu

Drabbe, Petrus; De Jong, Nico; and Van Dijk, Toos, 1995. De unieke Molukken-foto`s van Petrus Drabbe. Alphen an den Rijn, Periplus.

Forbes, Henry O., 1885. A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago, Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London.

Goudswaard, A., 1863. De Papoewa’s van de Geelvinkbaai, H.M.A. Roelants, Schiedam.

Hoëvell, Gerrit Willem Wolter Carel Baron van, 1890. Tanimbar en Timorlaoet-Eilanden, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIII, pp. 160-186, M. Nijhoff, ‘s Hage.

Jonge, Nico de and Toos van Dijk, 1995. Forgotten Islands of Indonesia, Periplus, Amsterdam.

Kaharudin, Hendri A. F.; O’Connor, Sue; Kealy, Shimona; and Ririmasse, Marlon N., 2024. Islands on the edge: 42,000-year-old occupation of the Tanimbar islands and its implications for the Sunda-Sahul early human migration discourse, Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 338.

Kaharudin, Hendri A. F.; Wicaksono, Gillar; Azis, Fairuz; Kealy, Shimona; Ririmassa, Marion N. R.; and O’Connor, Sue, 2024. Living Seaward: Maritime Cosmology and the Contemporary Significance of Natar Fampompar, a Stone Boat Ceremonial Structure in the Village of Sangliat Dol, Tanimbar Islands, Ethnoarchaeology, vol. 16, issue 2, pp. 255–280.

Kolff, D. H., 1840. Voyages of the Dutch brig of war Dourga through the southern and little-known parts of the Moluccan Archipelago, and along the previously unknown southern coast of New Guinea, performed during the years 1825 & 1826, Translated by George Windsor Earl, James Madden & Co, London.

Kuhnt-Saptodewo, Sri; Brandle-Straka, Ursula; and Tuarissa, Thontji, 2012. Maluku: Sharing Cultural Memory, Museum für Völker Kunde, Vienna.

Lebar, Frank M., 1972. Tanimbar, Ethnic Groups of Southeast Asia, vol. 1, Indonesia, Andaman Islands, and Madagascar, pp. 112-114, Human Relations Area Files Press, New Haven.

McKinnon, Susan, 1983. Hierarchy, Alliance and Exchange in the Tanimbar Islands, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago.

McKinnon, Susan, 1987. The House Altars of Tanimbar: Abstraction and Ancestral Presence, Tribal Art (Bulletin of the Barbier-Mueller Museum), vol. 1, pp. 3-16, Geneva.

McKinnon, Susan, 1988. Tanimbar Boats, Islands and Ancestors: Indigenous Styles of Southeast Asia, Jean Paul Barbier and Douglas Newton (eds), pp. 152-169, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

McKinnon, Susan, 1989. Flags and Half-Moons, Tanimbarese Textiles in an 'Engendered' System of Valuables, To Speak with Cloth, Gittinger, Mattiebelle, (ed.), pp. 27–42, University of California Cultural History Museum, Los Angeles.

McKinnon, Susan, 1990. The Slave in the Gift and the Market in Kinship: The Dynamics of Hierarchy in Tanimbar, Paper Presented at the First Maluku Research Conference, University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Honolulu.

McKinnon, Susan, 1990. Houses, Hierarchy, and the Dynamics of Objectification and Personification, Paper presented at the International Workshop on Indonesian Societies, no. 5, Halmahera Research and its Consequences for the Study of Eastern Indonesia, in particular, the Moluccas, Sponsored by the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology, Leiden.

McKinnon, Susan, 1991. Formed from a Shattered Sun: Hierarchy, Gender, and Alliance in the Tanimbar Islands, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

McKinnon, Susan, 2012. Houses and Hierarchy: The View from a South Moluccan Society, About the House: Lévi-Strasse and Beyond, pp. 170-188, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

McKinnon, Susan, 2000. 'The Tanimbarese Tavu: The Ideology of Growth and the Material Configurations of Houses and Hierarchy in an Indonesian Society', in Beyond Kinship: Social and Material Reproduction in House Societies, Joyce, Rosemary A., and Gillespie, Susan D., (eds), pp. 161–166, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Kuper, Lieut. Augustus L., 1839. Journal of a voyage to Timor Laut, the Arrou Islands &c., in Her Majesty’s Brig “Britomart”, March and April 1839, The Sydney Herald, pp. 1-2, 22 July 1839.

Pangemanan, Frits H., 2014. Masuknya Agama Katolik di Awear, Pulau Fordata, Tanimbar (MTB), P. T. Kanisius, Yogyakarta.

Pauwels, Simonne, 1990. The Awaire Relationship in a Tanimbarese Society. Paper presented at the International Workshop on Indonesian Societies, no. 5, Halmahera Research and its Consequences for the Study of Eastern Indonesia, in particular, the Moluccas. Sponsored by the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology, Leiden.

Pauwels, Simonne, 1985. Some Important Implications of Marriage Alliance: Tanimbar, Indonesia, Contexts and Levels: Anthropological Essays on Hierarchy, pp. 131-138, Anthropological Society of Oxford, Oxford.

Pauwels, Simonne, 1990.: From Hursu Ribun's "Three Hearth Stones" to Metanleru's "Sailing Boat", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 146, issue 1, pp. 21-34.

Renwarin, P., 1989. Life in the Saryamrene: An Anthropological Exploration of the Yamdena in the Tanimbar Archipelago, Maluku, Indonesia, Leiden.

Stokes, John Lort, 1846. Discoveries in Australia, vol. 1, T and W. Boone, London.

Taylor, Paul Michael; Aragon, Lorraine V.; and Rice, Annamarie L., (eds), 1991. Beyond the Java Sea: Art of Indonesia's Outer Islands, Harry N. Abrams, Washington D.C.

Vuuren, Marianne van, 2009. Ikat from Tanimbar, Orchid Press, Bangkok.

Publication

This webpage was published on 15 November 2025.