Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Kantha and Kantha Saris

Shamlu Dudeja's Background

The Development of the Kantha Sari

The Richardson Collection

Bibliography

Kantha and Kantha Saris

The traditional domestic Bengali craft of kantha was never used to make saris. It was a way of recycling old cotton saris, lungis and dhotis into embroidered quilts, covers or sitting mats, not into items of clothing. Usually three or more layers of old cloth were sewn together in a rectangle and naively decorated with various types of running stitch.

Kantha making almost died out in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, mainly because of the availability of cheap machine-made textiles imported from Europe. Various attempts were made to revive the craft but it was only after the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence that kantha making recovered, although not in its original form.

A tussar silk kantha sari

exoticindiaart.com

The initiative for creating kantha saris came from a Karachi-born woman called Shamlu Dudeja, who encouraged urban women living in a suburb of a town north of Kolkata to apply kantha embroidery decorations onto plain silk saris. This grew into a successful business enterprise, producing luxury saris for the prosperous elite of West Bengal and beyond.

A pair of very different kantha dupattas

Return to Top

Shamlu Dudeja's Background

Shamlu Kripalani Dudeja is a Hindu who was born in Karachi in 1938, the daughter of a professor of mathematics. When she was nine years old her family fled from their home in central Karachi because of the violence that engulfed the city after the traumatic Partition of India in 1947. They moved to Delhi, where her father obtained a job in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. While studying at her school in Delhi she was fortuitously taught to embroider kantha by a craft teacher who happened to come from Bengal. Little did she know that kantha would dominate her later life. She went on to Hindu College in Delhi and graduated with a degree in mathematics in 1957. After her family moved to Bombay she decided to study psychology part-time whilst working at a local tea company. It was there that she met her future husband.

Shamlu Dudeja in 2018

She married in 1962 and immediately moved to Kolkata where her new husband had found a job as a junior executive in another tea firm. After giving birth to her son the following year, her husband moved to the tea broking firm of J. Thomas and Company while Shamlu began teaching at a local private school. After her daughter Malika was born in 1968 she gave up teaching for a while but later joined an international school to teach mathematics.

In 1975 Shamlu won a scholarship from the British Council to go to England to learn a new method of teaching mathematics, obtaining a Diploma of Education from the University of Nottingham. She then obtained another scholarship to study how mathematics was taught in schools in the USA. With this background she was able to gain a better job in a teachers training college.

Return to Top

The Development of the Kantha Sari

Shamlu’s teaching career was halted in 1985 when she was diagnosed with stomach cancer. One afternoon while she was recovering from surgery in Kolkata, she chanced upon a handicrafts fair – the Shantiniketan Craft Mela. Many crafts were on display but one group of women were displaying and trying to sell their kantha embroideries. They came from Shantiniketan, the northern Bhubandanga neighbourhood of Bolpur city in Birbhum district, West Bengal, about 152km north of Kolkata. Shantiniketan was well known, being the place where Bengal’s Nobel Laureate poet, playwright and social reformer Rabindranath Tagore had established an ashram (school) in 1901 that by 1921 had developed into Visva Bharati University. Intrigued by their kanthas, embroidered on three layers of cotton fabric, she wondered if the same technique could be applied to some plain silk saris that she had recently been given by her husband.

She invited the group of women to her home and asked them if they could embroider her four white silk saris with kantha decorations. The women were initially reluctant to accept the task because they only worked on layered cottons, not a single layer of new silk. Shamlu asked them to give it a try and not to worry, as she would take full responsibility if the project proved to be unsuccessful. Shamlu told them to use any colours that they liked and suggested embroidering some paisley designs along the edges of the saris while adding butti motifs in the middle. She paid the women for their efforts in advance.

Shamlu Dudeja and her daughter Malika

Some weeks later Shamlu and her daughter Malika travelled to Shantiniketan to visit the women and were shocked to see the conditions they were living in. They lived in small huts, with just one room and no kitchen and lacked any cooking pots or pans.

Some months later three of the women arrived at Shamlu’s home with the finished saris. They were pleased with the results of their work and were keen to do more. Shamlu purchased more plain coloured saris from the local shop and sent them on their way.

In January 1987 before the second batch of saris had been finished, Shamlu was diagnosed with breast cancer and had to undergo a double mastectomy. Her daughter Malika had succeeded in gaining entrance to a college in Cambridge but gave up the opportunity so that she could stay in Kolkata to look after her mother and keep her kantha project alive.

Malika realised there was an opportunity to embroider kurtis and kurtas (long tunics worn over loose trousers) in a similar manner and set up Malika’s Kantha Collection & Trading Private Limited for marketing them. Village housewives were delighted to receive fair prices for their work, undertaken in the afternoons when all their housework had been done. Gradually, the group expanded from Birbhum district to North and South 24 Parganas, Burdwan and Nadia.

To sell the kantha saris and kurtas they organised friends in India, the UK and USA to hold kantha exhibitions in their homes. In Kolkata they established a stall in Khazana (the word means treasure), a high-end boutique located in the Taj Bengal Hotel in Alipore.

Both Shamlu and Malika were committed to improve the livelihood for the rural kantha artisans in Shantiniketan and realised that the most lucrative potential market was among the urban elites of India. In 1991 Shamlu founded Self Help Enterprise or SHE, an NGO for implementing welfare projects in the artisans’ villages, such as increasing access to health care, schooling, clean water projects and nutrition. The funding for SHE would be raised from a commission taken on the kantha sari sales. In 1993 Malika establishing the trading company Malika’s Kantha Collection, also in Alipore.

Shamlu Dudeja with a kantha artisan

Shamlu and Malika have proved to be masters at marketing their kantha wares. They have promoted it to Indian designers such as Rohit Khosla and Tarun Tahiliani and created a following among influential urban women in Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai. They have exhibited their kanthas widely – at the Governor of West Bengal’s residence in Kolkata, the Commonwealth Institute in London, the Gandhi Centre in the USA, The North American Bengali Conference in New York, the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe and at the International Quilt Week in Yokohama, Japan.

In 2012, they gained considerable publicity from Hillary Clinton, who bought a kantha panel from the SHE stall at the Taj Bengal, Kolkata, as a gift for the Chief Minister of West Bengal, Ms. Mamata Banerjee, the first woman to ever hold this position.

By 2013 there were about 2,000 rural women in West Bengal who had gained financial independence by undertaking embroidery work for SHE. Today it is estimated that there are over 20,000 artisans producing kanthas of one type or another across West Bengal.

Return to Top

The Richardson Collection

We acquired our fist two kantha saris at the SHE stall in the Taj Bengal Hotel in Belvedere Road, Alipore, at the beginning of February 1999. They were embroidered by kantha artisans from Shantiniketan, working for Shamlu Dudeja’s Self Help Enterprise NGO.

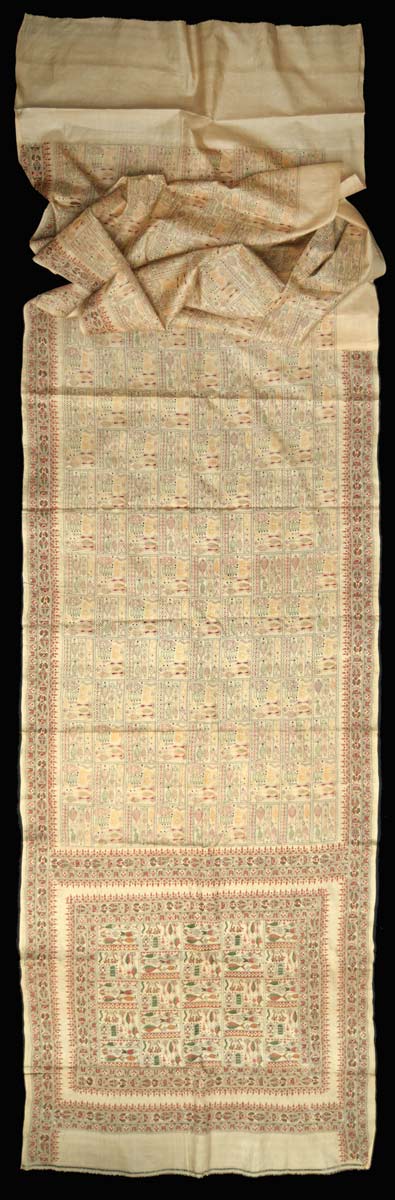

Each sari is made from a length of fine beige tussar silk, embroidered using red, green, yellow, orange and light brown mulberry silk threads. The traditional kantha-style embroidery has been executed in running stitch and employs traditional quilt motifs that have been stencilled by professional kantha designers.

The fish-design sari has a 10cm wide border running along each selvage, above and below the pallau end-piece and all four sides of the rectangular panel decorating the pallau. It has been filled with a repetitive series of motifs, including a tuna-shaped fish, what might possibly be a jellyfish, a small flower stem and a pair of leaves.

The fish-design kantha sari from Shantiniketan, West Bengal

Length 560cm, width 107cm

The centre of the end-piece contains two alternating rectangles, each containing a collection of motifs. One rectangle contains four fish of varying shapes and sizes, a squid or cuttlefish and a wingless parrot. The other contains a more complex range of motifs, amongst which can be identified: a single fish, a snake, a house, a window, a symbol of the goddess Lakshmi’s footprints, a swastika for good fortune, and what appears to be two ears of wheat or corn. These two rectangles are repeated throughout the whole field of the sari, although in this case only in outline form.

Close up of the pallu of the fish-design kantha sari

The fish is a common kantha motif, representing prosperity and fertility. Fish feature prominently in marriage rites in Bengal, and in one ceremony a fish is one of the main gifts taken to the bride’s house. Furthermore in a land dominated by rivers, the fish is seen as a symbol of fecundity, echoing the desire of the mother to have many sons.

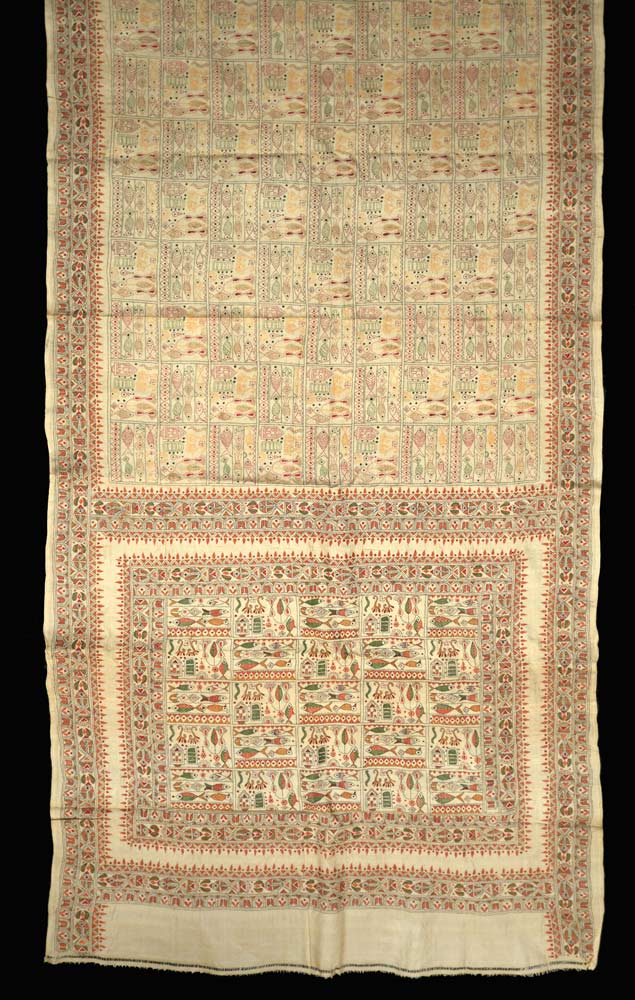

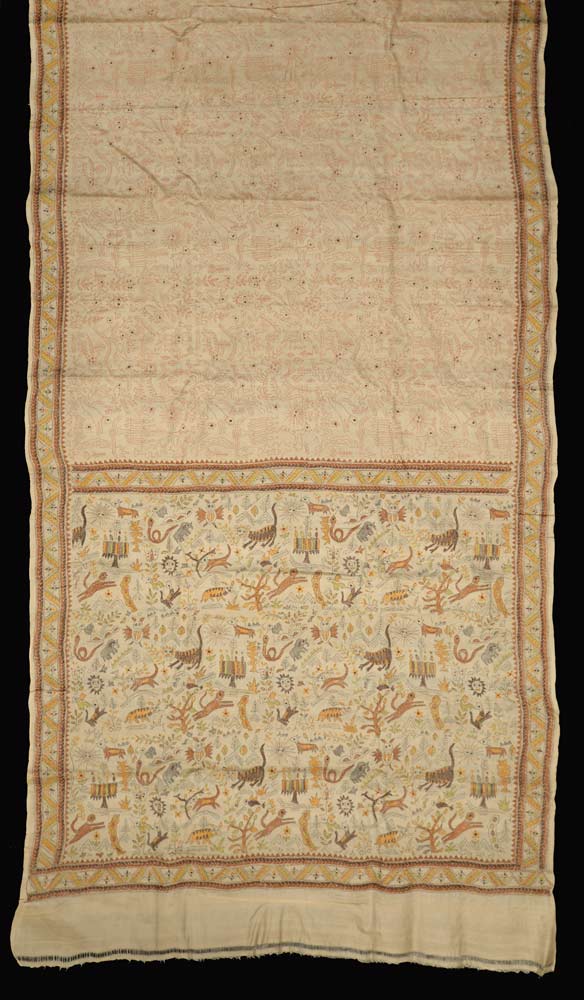

The zoomorphic-design sari has an 8cm wide border running along one whole selvage edge and along almost half of the other, being missing from that section of the sari tucked into the waist. It also runs above and below the pallu end-piece. The border design is a green and yellow zigzag flanked by two continuous rows of brown chevrons.

The zoomorphic-design kantha sari from Shantiniketan, West Bengal

Length 570cm, width 112cm

The square panel decorating the pallu has no formal structure, but consists of a random collection of motifs, which are repeated wallpaper fashion about six times. The motifs are quite naïve and child-like and consist of lions, tigers, deer, elephants, cats, dogs, monkeys, snakes, butterflies and birds, as well as trees, plants and flowers. These same motifs are repeated throughout the whole field of the sari, although as with the first sari, only in outline form using rust coloured thread. The alternate end to the pallau has been left clear of any embroidery for the final half metre.

Close up of the pallu of the zoomorphic-design kantha sari

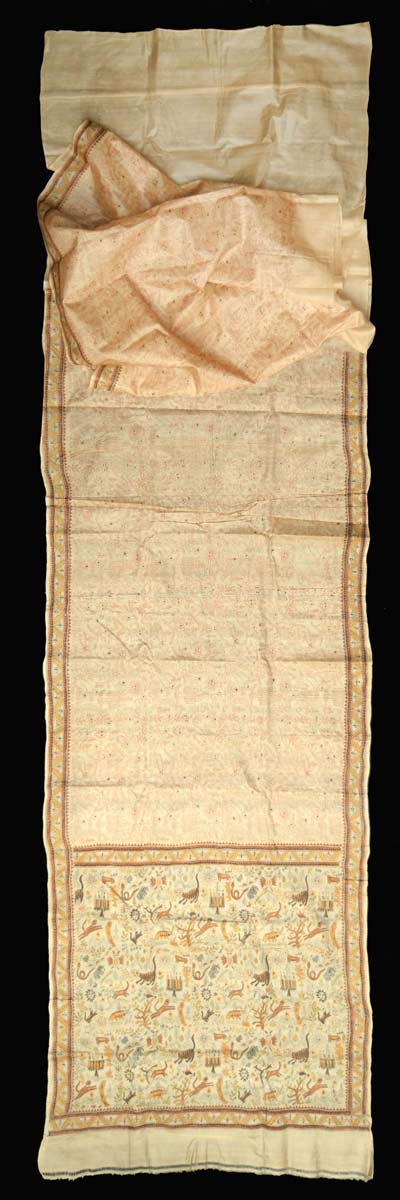

Our second pair of kantha saris were also acquired from the SHE stall in the Taj Bengal Hotel in Belvedere Road, Alipore, in 2006. They too were embroidered by kantha artisans from Shantiniketan.

By now some of the Shantiniketan kantha sari designs had developed a more contemporary feel. This pair of very long, fine silk saris have been made with a plain end piece that can be tailored into a matching blouse. They both have a zone-dyed central field and have been embroidered in a kantha-like style with swirling lines of parallel running stitches looped around randomly placed loci.

The first sari is light olive green and has a rectangular maroon central field decorated with swirling lines while the pallau has been embroidered with curled stems bearing star-like flowers and leaf sprays. Both the central field and the pallau are surrounded by a border decorated with a repetitive row of floral roundels. The end of the pallau terminates with a band of somewhat tumphal-like motifs. The other end of the sari has a plain green end section terminating in an embroidered maroon band.

Above: Contemporary kantha sari from Shantiniketan, West Bengal. Richardson Collection. Length 642cm, width 110cm. Below: Detail of the embroidered pallau.

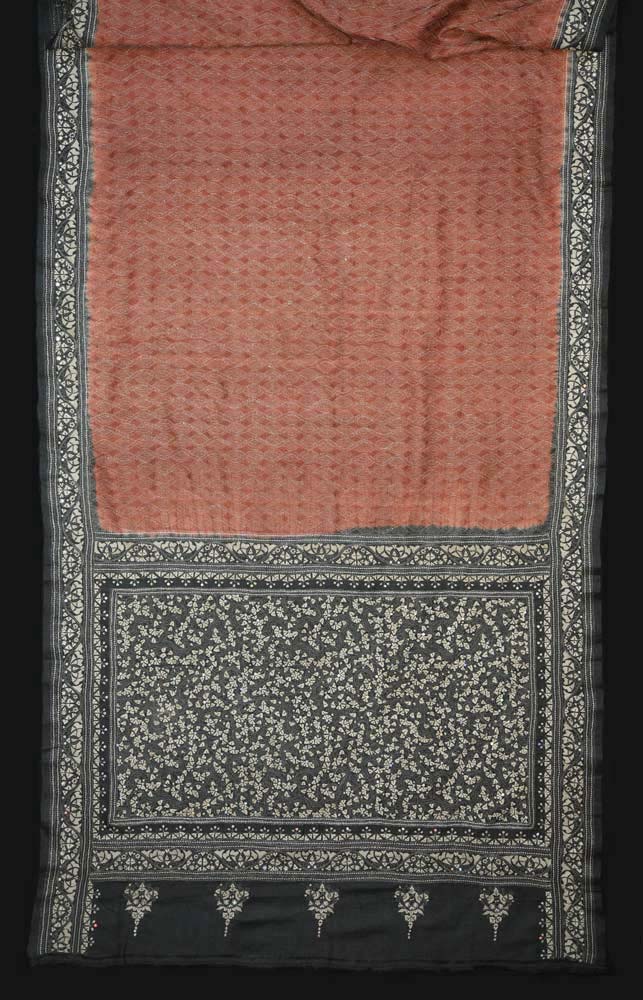

The second sari is dark slate grey and has a rectangular terracotta brown central field. The latter has been decorated with parallel rows of two intertwining waves. Meanwhile the pallau has been embroidered with a complex pattern of curling stems bearing small semi-circular florettes. Both the central field and the pallau are surrounded by a wave-like border decorated with alternating semi-circular motifs. The end of the pallau terminates with a band of tumphal-like motifs. The other end of the sari has a plain grey end section terminating in an embroidered terracotta band.

Above: Contemporary kantha sari from Shantiniketan, West Bengal. Richardson Collection. Length 631cm, width 114cm. Below: Detail of the embroidered pallau.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Bajpai, Lopamudra Maitra, 2021. The tradition of kantha embroidery: connecting several parts of the SAARC region, India, Sri Lanka and the SAARC Region, pp. 35-41, Routledge, Abingdon.

Bhagat, Rasheeda, 2015. Stitching up Dreams, Rotary News, August 2015, https://rotarynewsonline.org/stitching-up-dreams/

Basu, Rituparna, 1999. The History of the Kantha Art, The Journal of Women's Studies, vol. 3, pp. 79-126, Women's Studies Research Centre, Calcutta University.

Jones, Geoffrey, 2018. Shamlu Dudeja, Kantha Revivalist Director, Malika's Kantha Collection & Trading Private Limited; Chairperson, SHE (Self Help Enterprise) Foundation & Calcutta Foundation Interviewed by Geoffrey Jones, Isidor Straus Professor of Business History, Harvard Business School April 27, 2018 in Kolkata, India, The Creating Emerging Markets Oral History Collection, Harvard Business School.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 5 February 2022.