Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Raijua Textiles Part 2:

The Classification of Raijuan Ikats

Women's Costume

The Miniature Sarongs of Raijua

Èi Taba

Èi Wodattu

Èi Worapi

Èi Huri Wue

Èi Raja

Èi Mea

Èi Hebe Mea

Èi Ledo

Èi Beke Dara Womèdi

Èi Pudi

Èi Kubae and Èi Kemoru

Èi Dua Hebe

Men's Costume

Higi Taba

Higi Worapi

Higi Huri Wue

Higi Mea

Higi Pudi Wo Ie Rai

Higi Wohappi

Higi Pudi

Funeral and Other Sacred Cloths

Acknowledgements

Go back to Raijua Textiles Part 1:

The Complex Textile Culture of Raijua

Textile Collections

The Tao Leo Funeral Feast

The Habemaare Banni Kedo Ritual

The Pana Jami Ritual

Two Glimpses of Raijuan Textiles in the Past

Textile Thefts on Raijua

Textile Production on Raijua

Bibliography

The Classification of Raijuan Ikats

As already emphasised, the textiles of Raijua are incredibly complex. While it is possible to classify the most common types, there appear to be a vast number of exceptions and oddities. This webpage should therefore be regarded as work in progress, summarising our present understanding of Raijuan cloths from the limited information available. Hopefully we will be able to refine and add to this in future years.

The main obstacle is that today, traditional weaving on Raijua has almost completely died out. The epidemic of cloth thefts during the 1990s has meant that the information about valuable heirloom cloths has been lost while the widespread adoption of commercial yarn and synthetic dyes in the 2000s coupled with the increasing number of women abandoning weaving to participate in more lucrative seaweed farming has resulted in a dearth of knowledgeable women able to talk seriously about the textiles and textile culture of the past.

Return to Top

Women's Costume

As on Savu, the women of Raijua traditionally wore a ceremonial tube-skirt known as an èi (pronounced 'eye'), the majority made from two identical pieces cut from a single continuous loom length of cloth. While a few of the elderly women still wear an èi daily, the majority only use them for rituals, attending church or festivities. They are usually worn folded around the waist in combination with a Javanese kabaya or western blouse. Female dancers tend to wear their èi high under their arms supported by a metallic waist belt so that it covers their breasts. They often drape a man’s higi sash or blanket around the neck or wear one like a cape.

A young Raijuan woman wearing an èi worapi sarong and a higi worapi man’s blanket

Just as on Savu, the moiety of a woman can be identified by the colour of the inner selvages of the two panels at the seam (bakka) where they are joined to form the complete tube skirt. Hubi ae sarongs have red selvedges at the central seam while hubi iki sarongs have black selvedges at the central seam. This difference is attributed to the founding ancestors of the two moieties hubi ae and hubi iki, respectively Muji Babo and Lou Babo. In a weaving competition, Muji Babo took the thin dye from the upper part of the indigo dye pot, but Lou Babo selected the thick dye from the lower part (Kagiya 2010, 98).

On Raijua, there appears to have been an endless variety of women’s sarongs – it is hard to find any two that are similar. Furthermore the designs appear to be less prescribed, with women using their initiative to create their own new interpretations of classical layouts.

Raijuan sarongs are ranked in status and valued in comparison to a female water buffalo, a rena kebao. The highest status cloth being worth one whole buffalo and the lowest status cloth one twentieth of a buffalo:

| Rank | Name | Description |

| 1 | Èi Taba or Rena Kebao | A sacred two- or three-panel skirt, regarded as the ikat for a queen. It must be stored as a pair with a higi taba in the amu ina apu. |

| 2 | Èi Wodattu | A two-panel skirt with bands of large floral motifs decorated with painted dots. |

| 3 | Èi Worapi | A two-panel skirt introduced in the 19th century with white black and red bands. |

| 4 | Èi Huri Wue | No description. |

| 5 | Èi Raja | A daily two-panel skirt with seven black stripes decorated with white floating warp stripes. Reserved for the aristocratic hubi ae. |

| 6 | Èi Mea | A two-panel red sarong. |

| 7 | Èi Ledo | A daily two-panel skirt with an ikat band containing the serpent motif in combination with four stripes and reserved for the hubi iki. |

| 8 | Èi Pudi Tie | An undecorated white two-panel sarong. A symbol of purity. |

| 9 | Èi Hebe Maddi | No description. |

| 10 | Èi Pudi Mau Wodattu | A two-panel indigo-dyed sarong with a band decorated with tie-dyed white spots. |

| 11 | Èi Pudi Mau Dja’a | A two-panel sarong with wide plain indigo-dyed bands. |

Women’s sarongs are decorated with around 60 different main motifs, three times as many as available for men. These are known as hebe, a term also applied to the whole band. Some motifs are specific to individual matrilineal groups whereas others can be shared, usually because those groups share the same ancestors.

Return to Top

The Miniature Sarongs of Raijua

A significant proportion of the sarongs that were made on Raijua are like small versions of adult tube skirts – a unique feature of the island’s textile culture. In the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum Collection, of the 22 ikatted sarongs (excluding the èi pudi mau) 8 are miniature versions (36%). In the Richardson Collection, of the 13 similarly ikatted sarongs, 4 are miniature versions (31%).

Commentators who are unfamiliar with the island often claim that these were made for children, but this is mostly not the case. Raijuans could not afford to buy ready-made children’s clothes so most girls did wear a sarong when they were still young but this was normally too large for them, so they had to fold it into many layers to be able to wear it. Girls also used this sarong to sleep in. Nevertheless a few girls did have a children’s sarong made by their mother (Kagiya 2010, 96). It is not clear if this was ikatted.

A miniature sarong from Raijua labelled as a kindersarong

Museum der Kulturen, Basel

However some of the miniature Raijuan sarongs were clearly unwearable, even by the tiniest child. They must have been made for another reason:

A very narrow miniature sarong from Raijua

Because Raijua is extremely poor ikat was, and still is, highly valued, both as precious private property and as the common property of each wini or kepepe (of which there are 74).

Some small ritual sarongs were made as personal private property, to be used for the traditional Jingi Tiu baptism ceremony for a new-born baby, known as the Hapo Ana ritual (hapo = to accept, ana = a child).

After a woman gave birth to her first child – whatever its gender – her husband ordered her to make a small sarong for the Hapo Ana ritual. According to Kagiya, this sarong was a symbol of the mother’s womb and a memento of her menstrual bleeding (2010, 204). The ritual was performed for all new-born children but in the case of the very first child, a more elaborate version of the ritual was held called Hapo Puru Rai (‘accept descent to the earth’). The eldest child of the family was known as ’the child who made the road for the amniotic fluid from the mother’s womb’ and as such was respected by its younger siblings.

The Hapo Ana ceremony is performed in the month of Bhui Ihi (April to May) following the child’s birth. During that month every individual cleans himself or herself and their domestic animals before cleaning the graves of the deceased. Many domestic animals are sacrificed and meat is given to married sisters. The Hapo Ana ritual can be held at any time once three days have passed after cleaning the ancestor’s graves. During the Hapo Ana ritual the child becomes a formal member of Raijua Island and a Niki Maja or warrior of Maja (Kagiyo 2010, 204-205).

One aspect of this ritual was that it provided an opportunity for the father of an illegitimate baby to acknowledge his paternity over the child. If the father of such a child did not bring the appropriate gifts laid down by customary law, he lost his parental rights over that child for ever.

In the past every family owned such miniature sarongs, so they were common. They were kept in a basket together with a piece of aromatic tree and certain other magical items and were stored in the roof of the house. These sarongs were never worn but were kept to ensure the good health and well being of the child as it grew older.

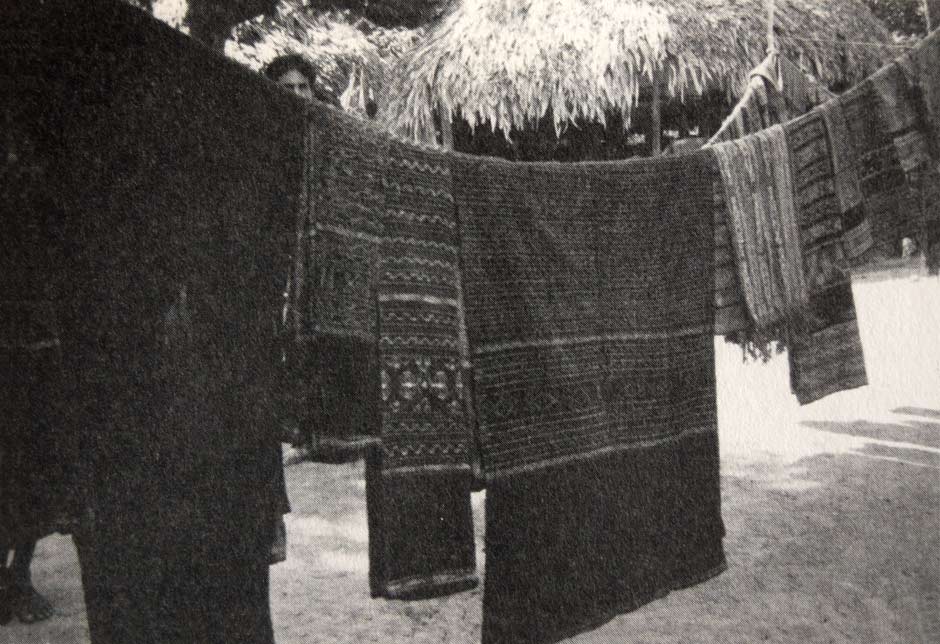

Many other small sarongs were made for the communal holdings of textiles owned by each wini and kepepe, stored in kepepe baskets inside the ritual amu ina apu – the house of the female ancestors. These were vitally important because the quantity and type of ikats stored in each amu ina apu determined the social rank of that wini or kepepe. It was therefore necessary to accumulate these holdings of cloth over many generations, especially if the matrilineal group were to qualify for holding the extravagant and expensive Tao Leo funeral festival and feast, a tradition that has been lost on Savu. The house of the deceased was decorated with many textiles so that his or her ancestors could identify the wini to which he or she belonged. Such cloths had to be hand-spun and be naturally dyed.

The production of communal ikats placed a burden on the members of each matrilineal group because resources like cotton and natural dyes were not only limited but sometimes scarce. However as Akiko Kagiya (2010, 213) makes clear:

According to their customary law, if dyeing and weaving cloth in a regular size is difficult, such cloth in a smaller size is acceptable.

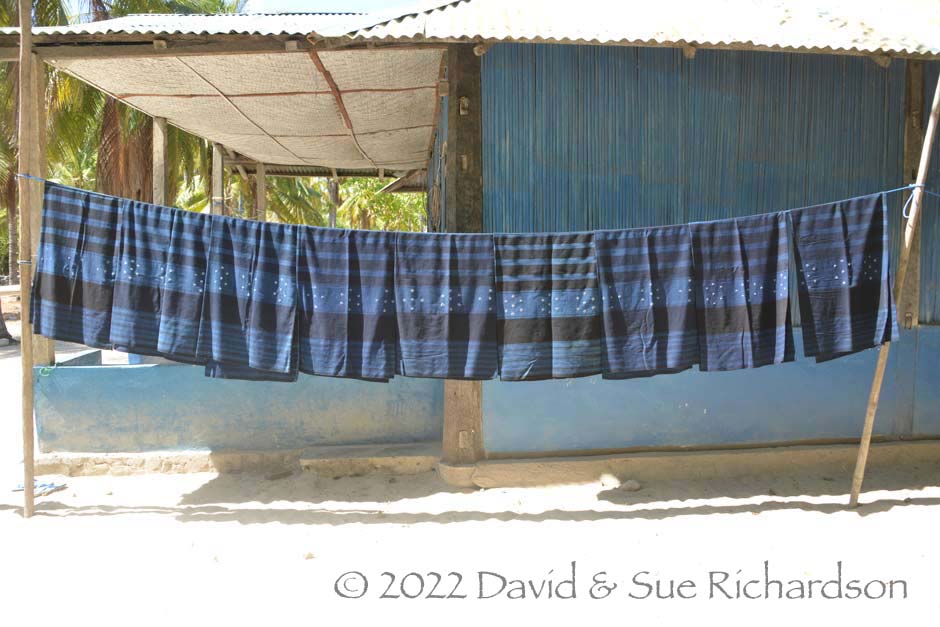

Consequently when an amu ina apu occasionally aired the contents of its kepepe in the wind, quite a few of the cloths on display were seen to be small sized (Kagiya 2010, 142).

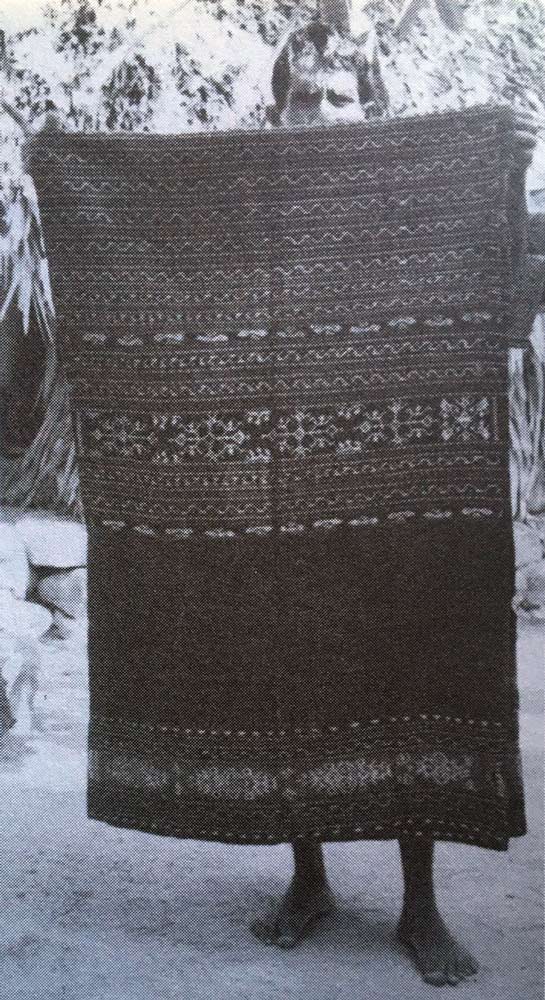

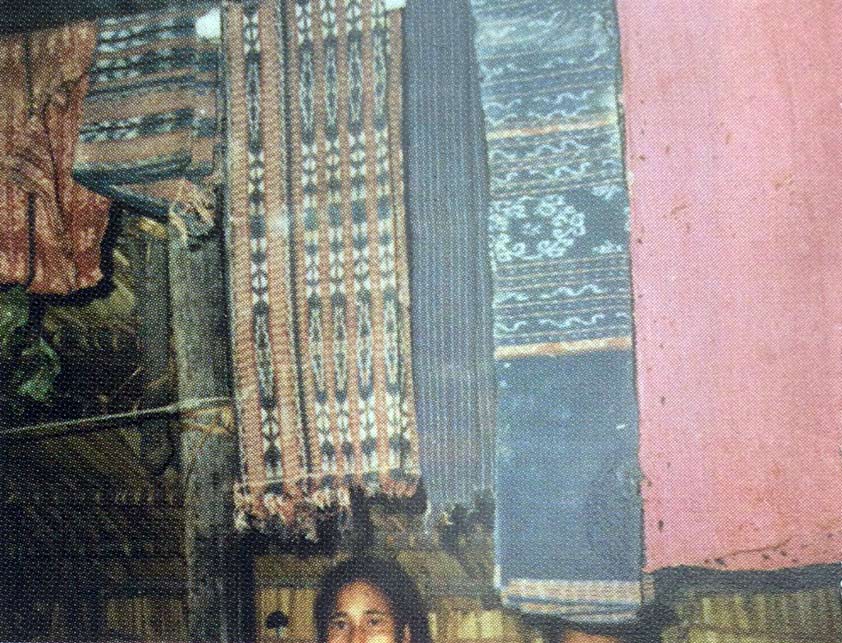

A mixture of full-sized sarongs and small-sized sarongs being aired by wini Mako at a Pemeringi Kebao water buffalo sacrifice ritual in the 1980s. Photographed by Akiko Kagiya

At the same Pemeringi Kebao festival Akiko Kagiya noted that there were many small sized cloths on display ‘because economically it’s difficult to prepare cloths in full size’.

A few of the miniature sarongs being aired along with a large èi taba at the same Pemeringi Kebao ritual, photographed by Akiko Kagiya

It was obligatory for each wini to store a set of the highest status cloths together – an éi taba sarong, a higi taba man’s sarong and two wai ae belts. Because poor wini often struggled to follow this rule they sometimes had to make do with miniature versions of these cloths (Kagiya 2010, 115).

Return to Top

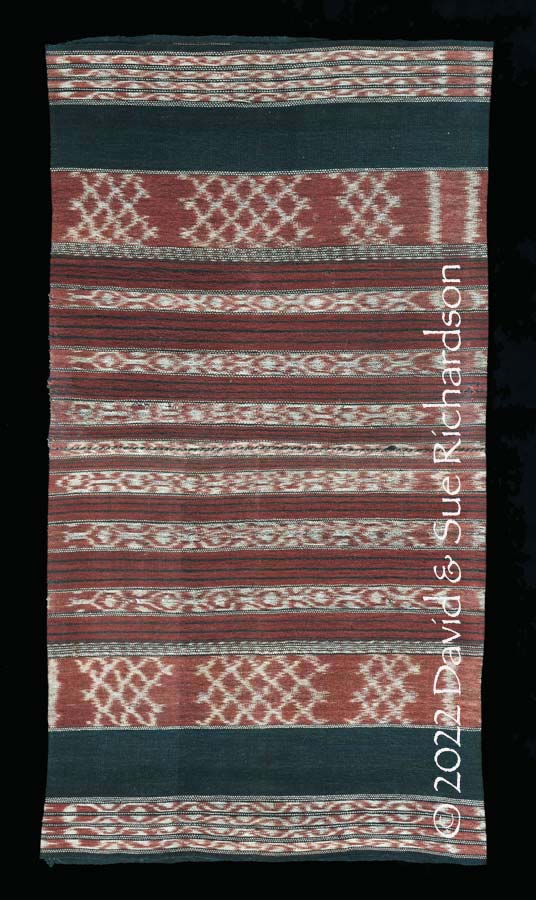

Èi Taba

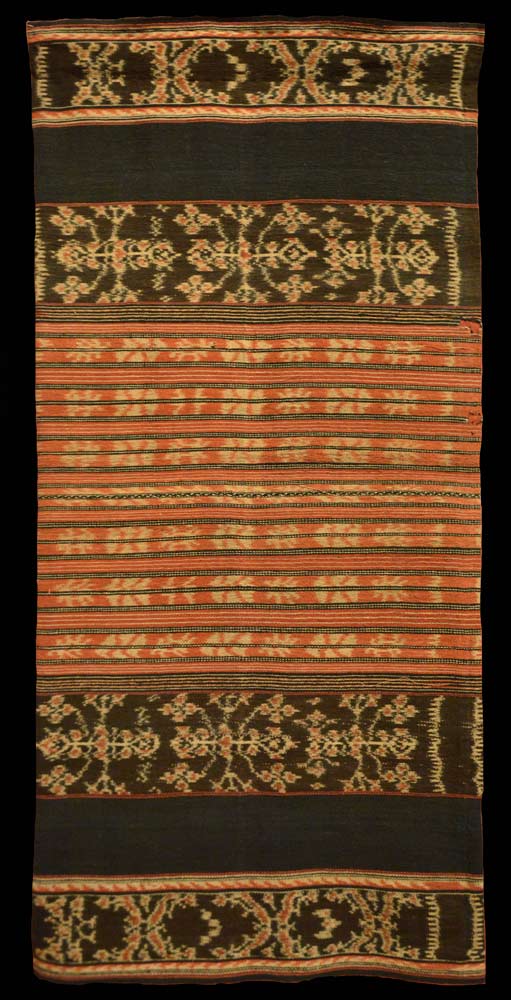

The èi taba is a sacred, oversized three-panel woman’s sarong, about 50% larger than a normal adult sarong. Along with the man’s sacred higi taba it is one of the two highest status textiles woven on Raijua. Taba means forbidden.

Just to confuse matters, the higi taba is not a blanket but a two-panel sarong, the difference between that and the èi taba being the number of panels, the background colour of the motifs and the size. The three-panel èi taba has white motifs on a blue-black background while the two-panel higi taba has white motifs on a red background; the èi taba is also wider and longer than the higi taba.

An old éi taba with no provenance.

Richardson Collection

Referring to such cloths as èi taba or higi taba on Raijua Island invites illness. These cloths are therefore referred to as a rena kebao, meaning a female buffalo. The ancestress Marega wove the first rena kebao for her brother.

The value of an ikat on Raijua is measured in terms of how many pieces are equivalent to the cost of a female water buffalo. Female water buffalo are never killed but male water buffalo will be sacrificed at the matrilineal group’s Pemeringi Kebao ritual once they grow to the right size. One rena kabao is equivalent to one female buffalo, making it the highest value cloth on the island (Kagiya 2010, 113). A lower ranked ikat may have a value of one twentieth that of a buffalo. Such high status ikats are the symbol and pride of the wini and can never be used as a daily sarong or hip wrapper. The more rena kebao owned by a wini, the greater its status and power. Each wini distinguishes itself by using a different motif for its rena kebao.

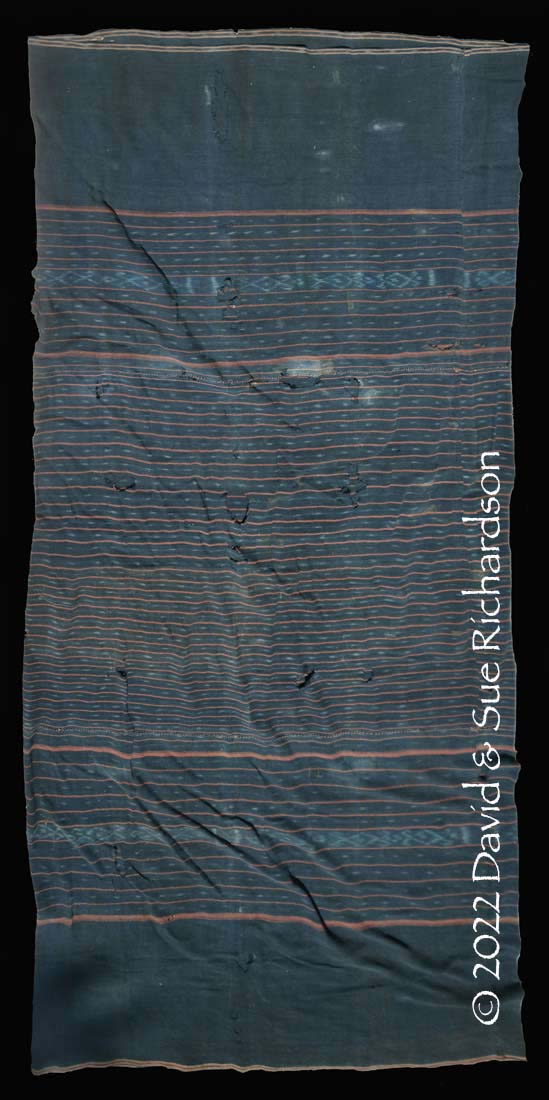

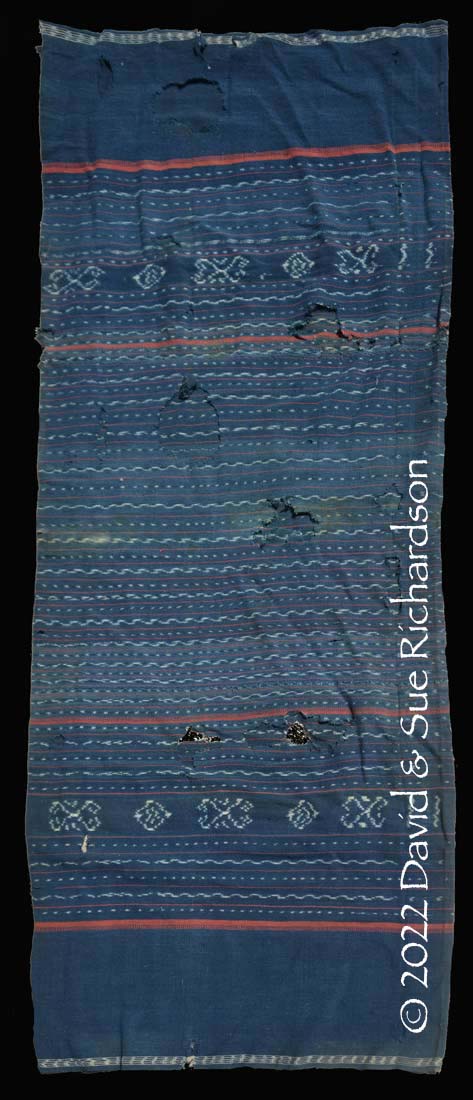

Above and below: two old torn and tattered èi taba. Private Collection, Indonesia.

A later éi taba with no provenence. Private Collection.

According to the rules laid down by Banni Kedo and Marega, every wini with an amu ina apu must have at least one pair of rena kebao (an èi taba and a higi taba) stored in their kepepe lontar baskets, which hold their collection of ikats. The basket must also contain a pair of wai ae, large striped torso wrappers, which symbolise the brother. These are considered to be paired with the two rena kebao, which symbolise the sister. Wai ae and rena kebao have the same value, equivalent to one buffalo. According to tradition, a wini should hold a maximum of 15 rena kebao, although one wini, Jingi Wiki, owned 29 in 1985 prior to the start of the textile thefts. Most owned between 2 and 7. A 1985 survey showed that collectively, the 20 wini on Raijua owned only just over 100 female rena kebao, indicating their rarity. Since 1991 the large-scale thefts from the major wini has decimated their holdings of heirloom textiles.

A later éi taba collected in Kupang in 1983

Richardson Collection

According to Kagiya, a rena kebao is not only considered to be the ikat of a queen but is actually treated like a queen. It is therefore always displayed on a number of cushions, each made from a folded belt or wai, placed under its head, shoulders, chest and legs (201, 116). The most common number of wai used was 5, but several kepepe used 9. As a symbol of its power, kepepe Jingi Wiki used 15 wai and èi. Only the elderly members in each matrilineal group qualified to lay down a rena kebao.

There are very strict rules limiting the use of rena kebao. Only a tiny number of wini are permitted to use them as a funeral shroud. Thus in kepepe Jingi Wiki, a rena kebao can be used for the funeral of its Mone Aa or male leader.

Akiko Kagiya mentions that there are four types of èi taba (and also higi taba):

- èi taba womaddi

- èi taba womea

- èi taba worapi

- èi taba based on a mixture of the above three types

Unfortunately she provides no information on what distinguishes each of them (2010, 119). We suspect that in the womaddi the main ikat band is dyed blue-black, in the womea it is dyed morinda red and in the worapi it is dyed both blue and red. One of the five éi taba in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum Collection is of the fourth type, having two main ikat bands on either side of the wide plain media ae band, a worapi on the inner side and a mea on the outer side.

It is clear that the weaving of èi taba textiles ceased a considerable number of decades ago. Emanuel, the 50-year-old son of the indigo master dyer Getreda Kana Koy, who lives with his mother at Ledeunu says that although he had heard of the rena kebao, he had never seen one throughout his entire lifetime.

Return to Top

Èi Wodattu

The èi wodattu is a two panel sarong decorated with large cross-shaped flower motifs ikatted on a red background with round white spots with coloured centres. The latter are not dyed by immersion like the rest of the ikat but are individually painted with dye on the binding frame using either indigo, morinda or turmeric. Wodattu means dot.

There are three types of èi wodattu: èi wodattu dao with blue-black spots, èi wodattu kabbo with red spotsand èi wodattu keoni with yellow spots. The èi wodattu dao is the most valuable, considered to have the same status as a silk Gujarati banni jate patola.

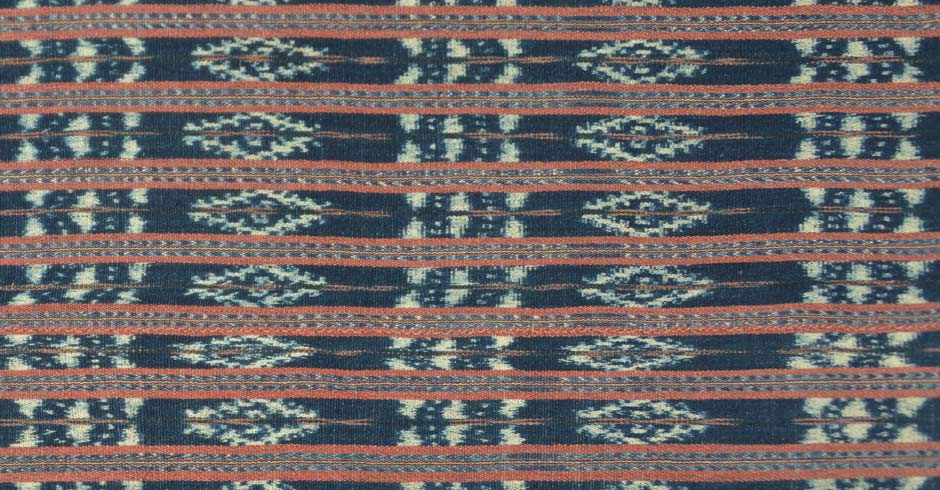

A detail from an èi wodattu dao

No wini or kepepe is allowed to perform the Tao Leo ritual without possessing an èi wodattu (Kagiya 2010, 178).

It is believed that the first èi wodattu was made at the time of Banni Kedo, some 15 generations ago. There is a story that illustrates the ancestresses brutality. One day Banni Kedo became angry after seeing a woman from a wini without a name wearing an èi wodattu dao. She killed the woman and cut her in half with a sword.

In the past the aristocratic wini of hubi ae owned many more èi wodattu than the wini of hubi iki (Kagiya 2010, 117).

Return to Top

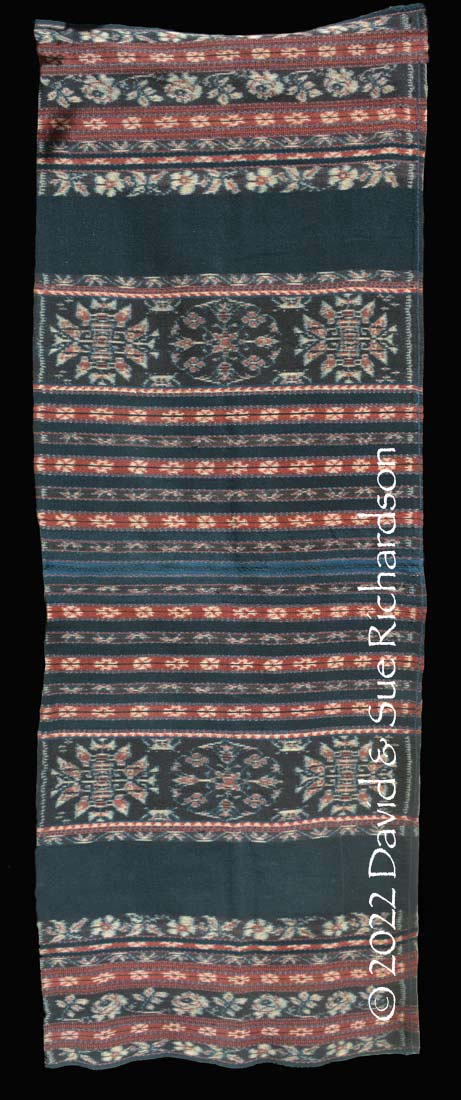

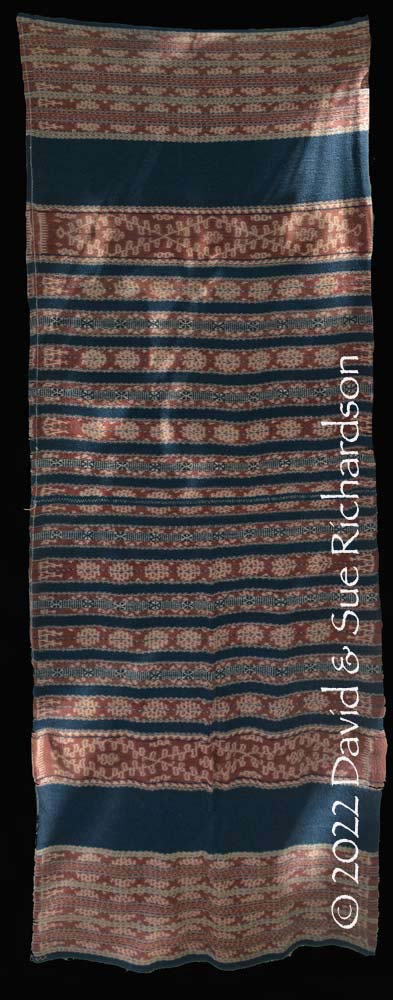

Èi Worapi

The two-panel èi worapi ranks number three in terms of the status of women’s cloths. It is a relatively new style of sarong that emerged during the nineteenth century under the influence of Dutch colonial rule and the Protestant church. The èi worapi incorporated elements from both hubi so that either could wear it. The motifs are sometimes based on western depictions of flowers and even dancers and sailing ships.

An èi worapi with the patola motif, Ledeunu.

The central indigo seam (bakka) indicates that it was made for a woman from hubi iki.

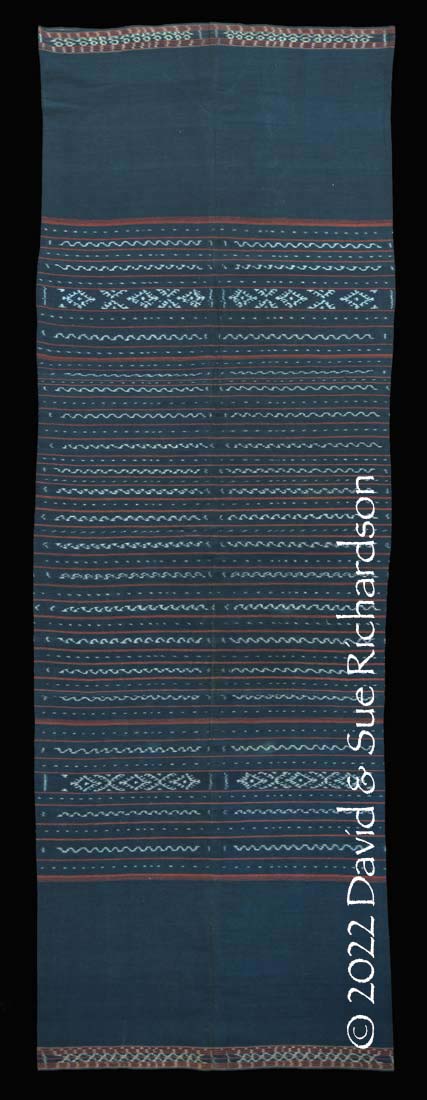

The èi worapi has a hebe that has been dyed to produce three colours – red, white and blue-black. The central section has narrow bands of ikat separated by plain black stripes, frequently seven. Such sarongs are neutral and can be worn by either the hubi ae or the hubi iki.

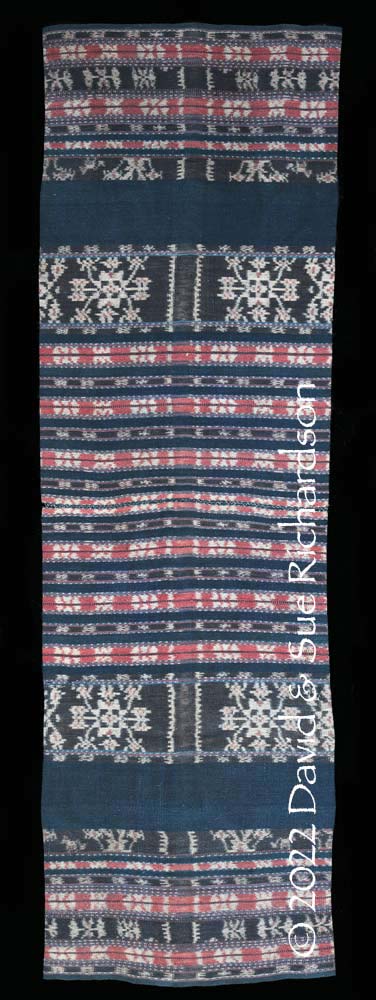

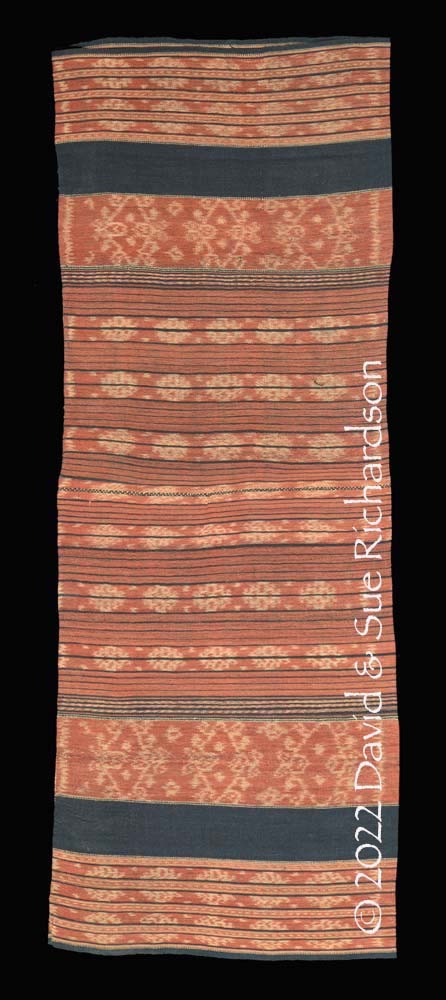

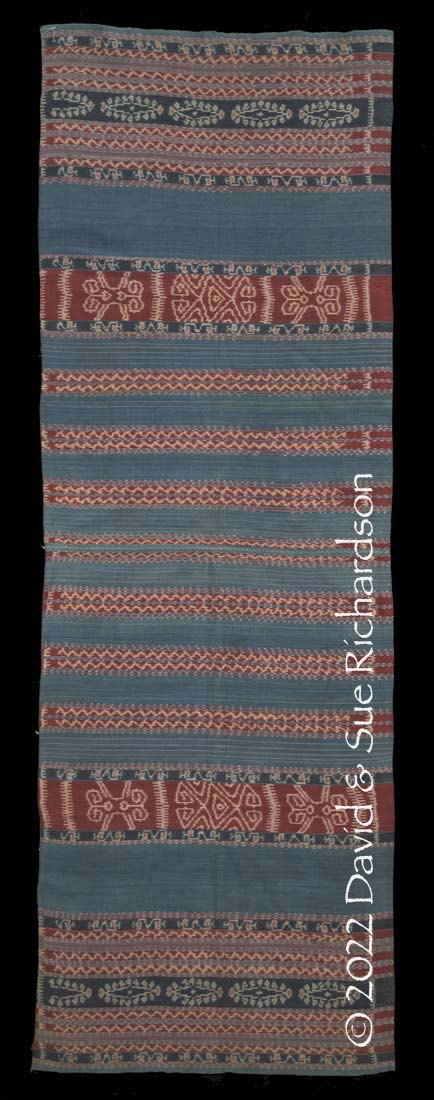

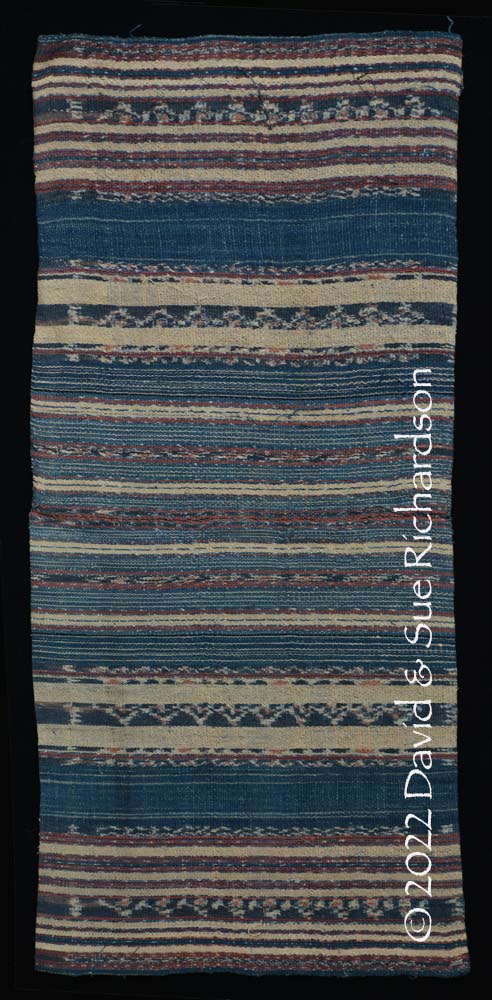

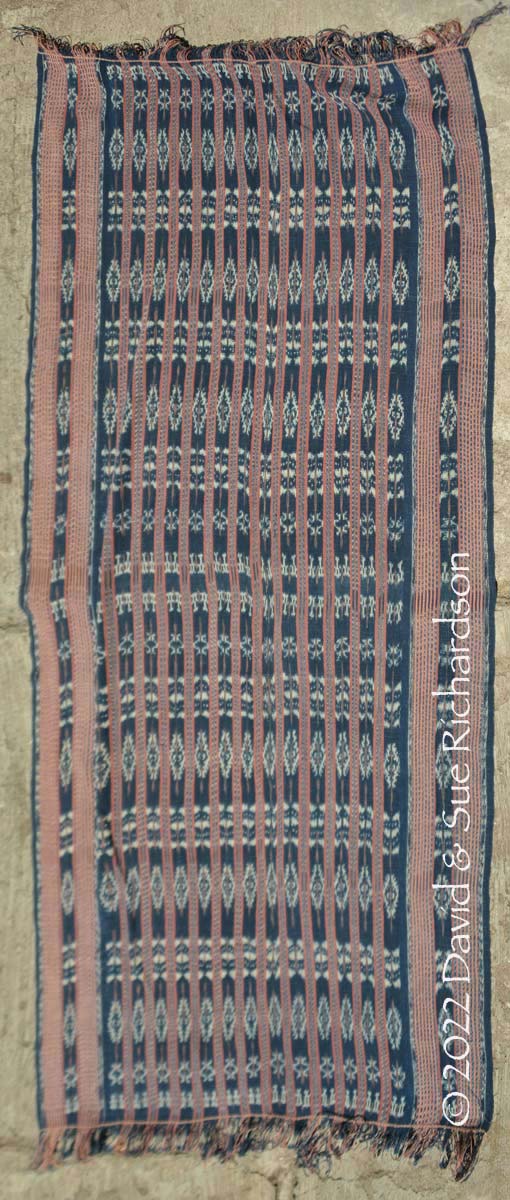

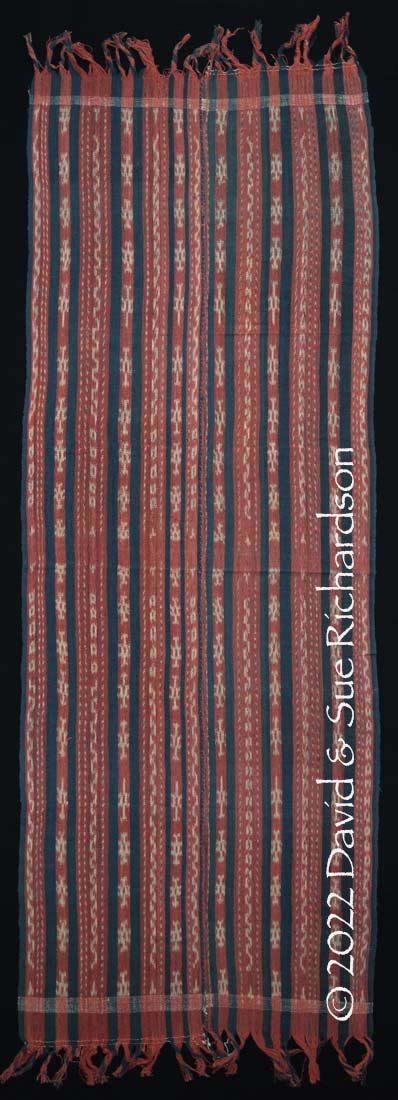

The following miniature èi worapi is decorated with the starfish or gage motif, which is only found on Raijua:

A miniature èi worapi from hubi iki acquired in Kupang in 1983

Richardson Collection

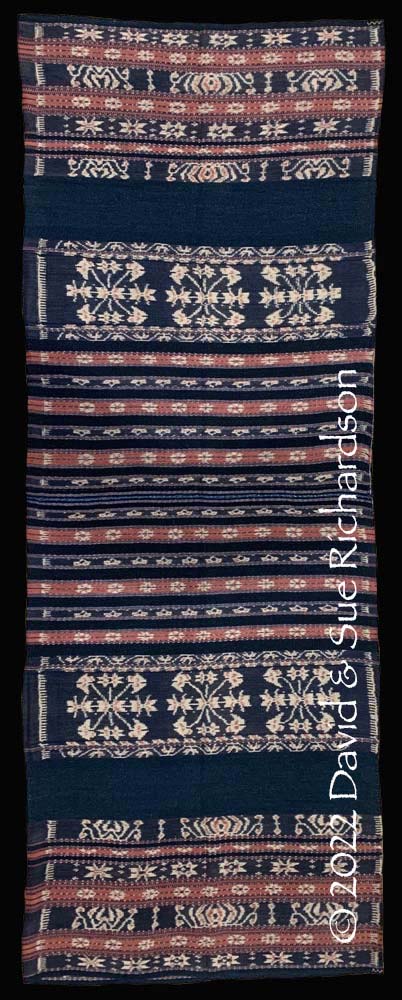

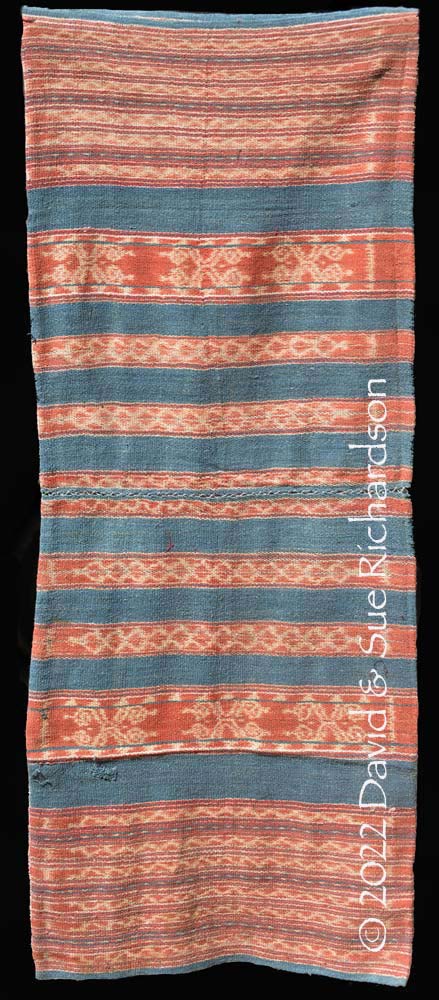

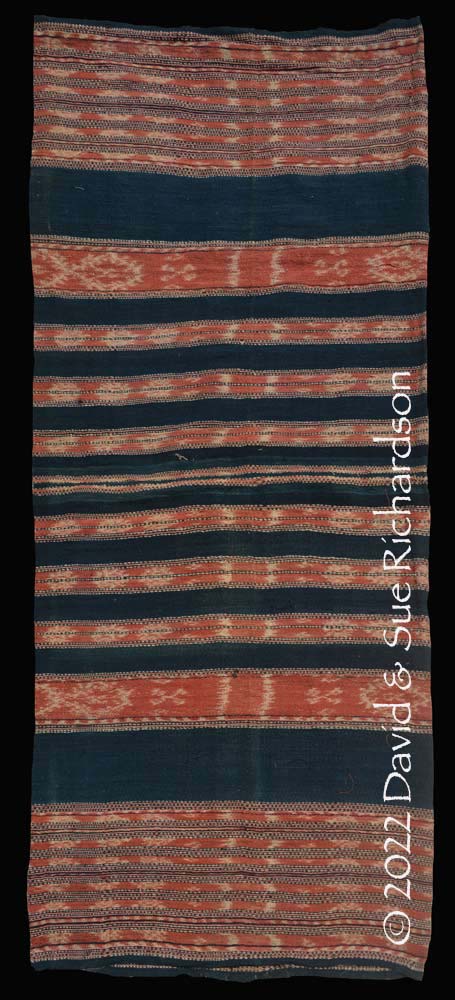

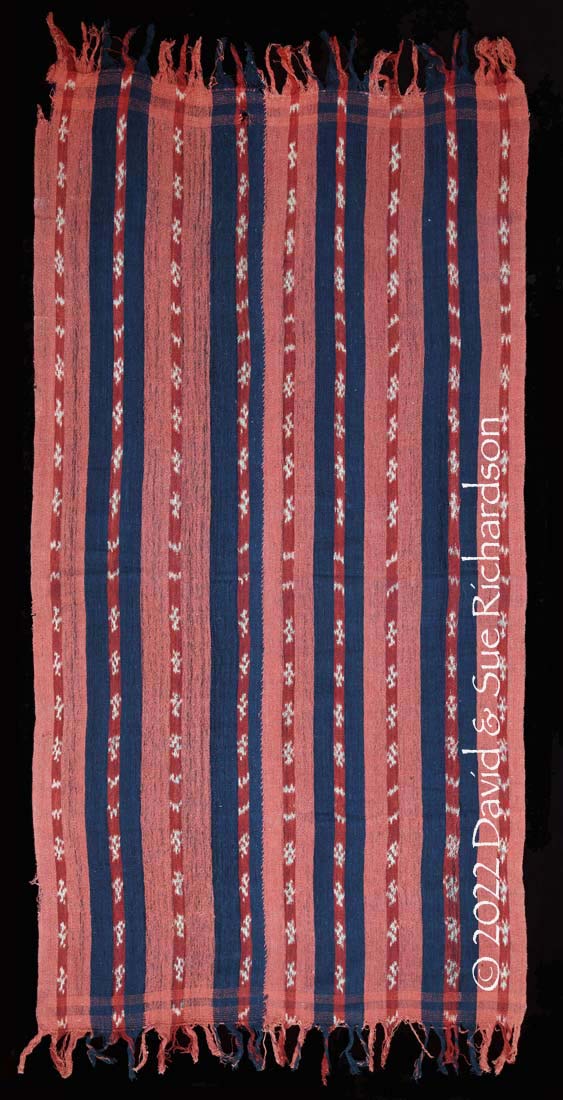

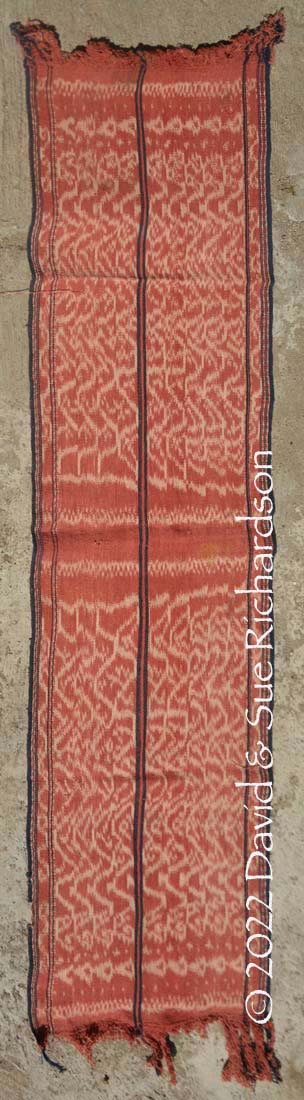

A full-sized èi worapi from hubi iki

Richardson Collection

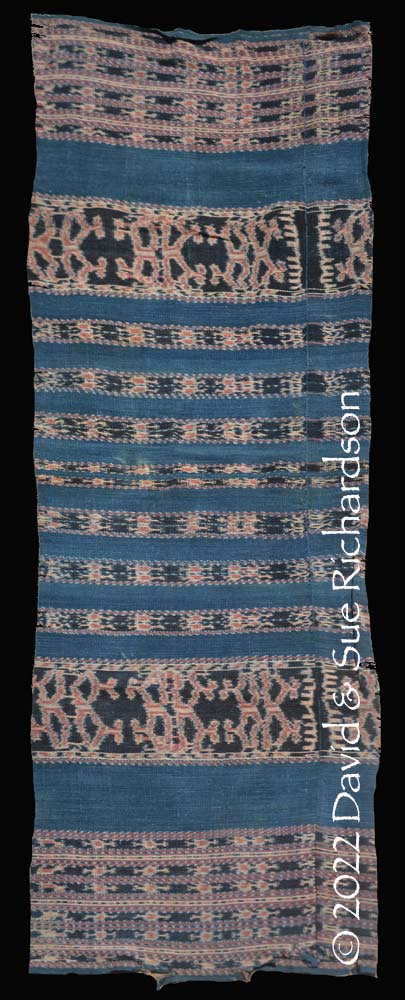

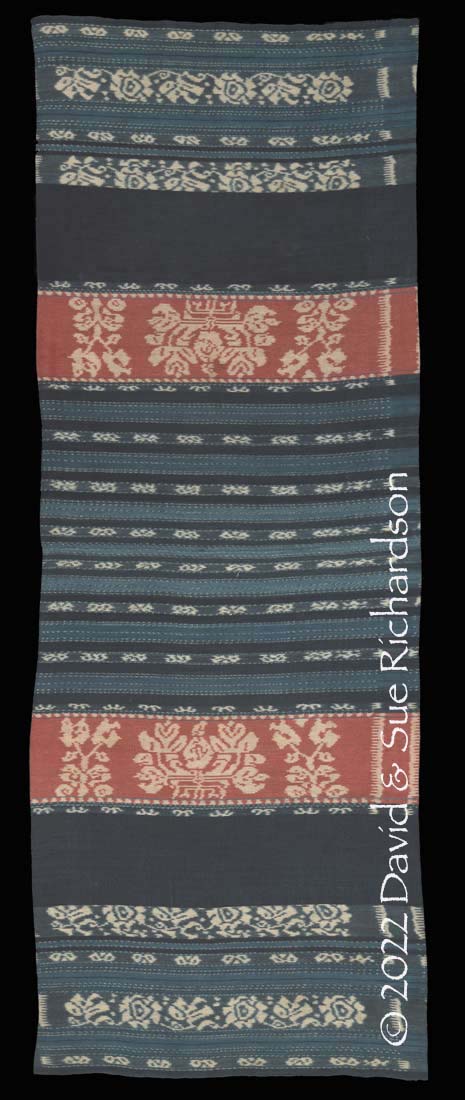

Another full-sized èi worapi from hubi iki

Private Collection

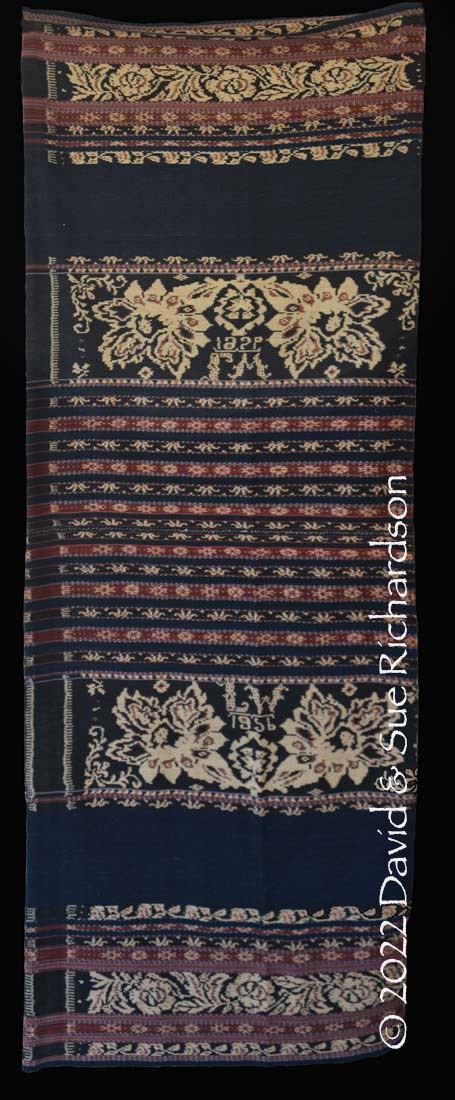

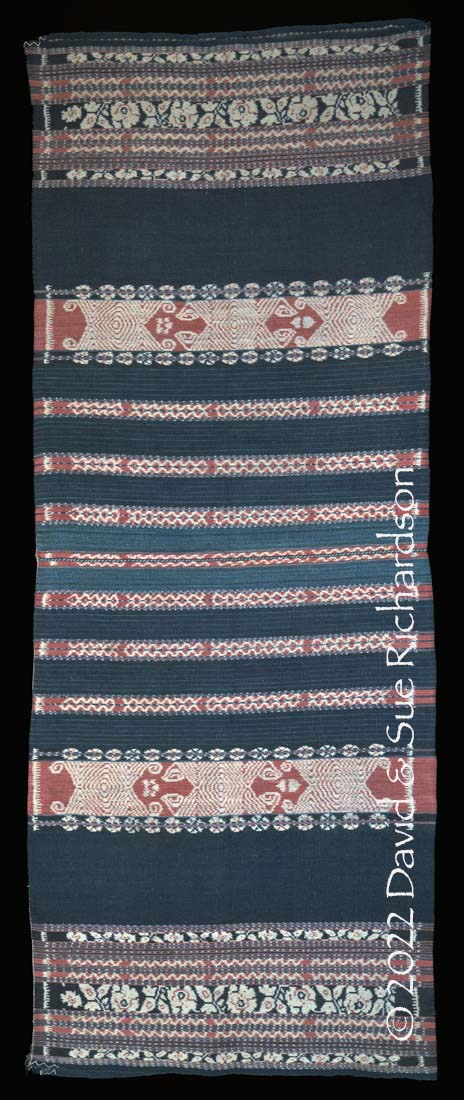

An èi worapi from hubi iki woven in 1956

Private Collection Kupang

The ikat band from an èi worapi depicting the Dutch Royal coat of arms with two rampant lions

The ikat band from an èi worapi depicting a pair of Dutch ships

The ikat band from an èi worapi depicting a pair of sitting females flanking a floral bower

Èi worapi can be used as a funeral shroud for both men and women.

Possession of an èi worapi or a higi worapi is an essential requirement for a wini or kepepe to qualify for staging a Tao Leo funeral feast. Unlike other cloths, èi worapi can be bought and sold. Wini with a low social status that are not permitted to own an èi worapi can purchase the right to weave and wear a worapi if they pay a very high price to a wini which already owns a worapi (Kagiya 2010, 118). However some wini have a tradition to never sell the èi worapi inherited from their ancestors no matter how much they are offered. The wini kept a mental record of which worapi were inherited from their ancestors and could not be sold and which had been purchased.

People believe that bad things will occur if the rules of rituals like Tao Leo are not followed. After wini Lebe performed Tao Leo Penuni without an èi worapi, one of its female members suddenly disappeared without trace.

A modern chemically dyed èi worapi decorated with a sailing ship motif

Today èi worapi made from commercial cotton and dyes are widely worn for festivals and ceremonies.

Three modern floral èi worapi near Ledeunu

Return to Top

Èi Huri Wue

We have never seen an èi huri wue and neither have any of the women we have asked on Raijua. Local people say that huri means flower, just like hebe, and wue means only, so the implication is that the description means ‘only flower’. However according to Walker (1982), in Savunese huri is a letter and wue is a qualifier for numbers (as in he-wue = one-count or just one).

Return to Top

Èi Raja

An èi raja normally has the inner section of each panel decorated with seven plain black stripes called roa and three so-called raja stripes woven in complimentary alternating black and white floating warp. The latter is directly associated with the aristocratic hubi ae and the creation of the function of raja during the colonial period. Although not mandatory, women from hubi ae are supposed to wear the èi raja as an everyday sarong.

The following èi raja is decorated with the common diamond-shaped woore motif, which is used by both moieties. People can wear ikat with this motif on any occasion and in any place. This example is unusual in that the central seam or bakka is black, suggesting it was woven by a woman from hubi iki.

An èi raja with the woore motif

Family heirloom, Raijua

Èi raja sarongs seem relatively rare compared to èi ledo sarongs. For example, there are only two out of the 22 ikatted sarongs in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum Collection.

While the èi worapi is usually used as a funeral shroud, if one is not available and if the deceased is a woman from hubi ae, then an èi raja can be used instead. If it is a man they use a higi wohappi.

A very unusual èi raja womèdi in the Richardson Collection, sometimes just called an èi womèdi or black sarong, has seven plain black stripes on the inner part of each panel but no raja stripes. It was made from very fine hand-spun cotton by the late Ibu Oborea who belonged to wini Ga of the aristocratic hubi ae. We acquired it from the weaver’s daughter, Ria Djami, who was 73-years-old. Ibu Oborea made the sarong about 50 years ago, dyeing the yarns many times to achieve a deep blue-black. It is decorated with the kobe motif, which originated from wini Ga Lena on Savu and represents stars. On Raijua it is the most important motif of wini Ga. Although a similar kobe motif is used by hubi iki, its appearance is different.

An èi raja womèdi with the kobe motif woven by Ibu Oborea half a century ago

Richardson Collection

According to Akiko Kagiya, if a normal èi taba was not available for the Tao Leo Penuni ritual, the most elaborate of all the funeral feasts, then it could be substituted by an èi womèdi (2010, 182).

Return to Top

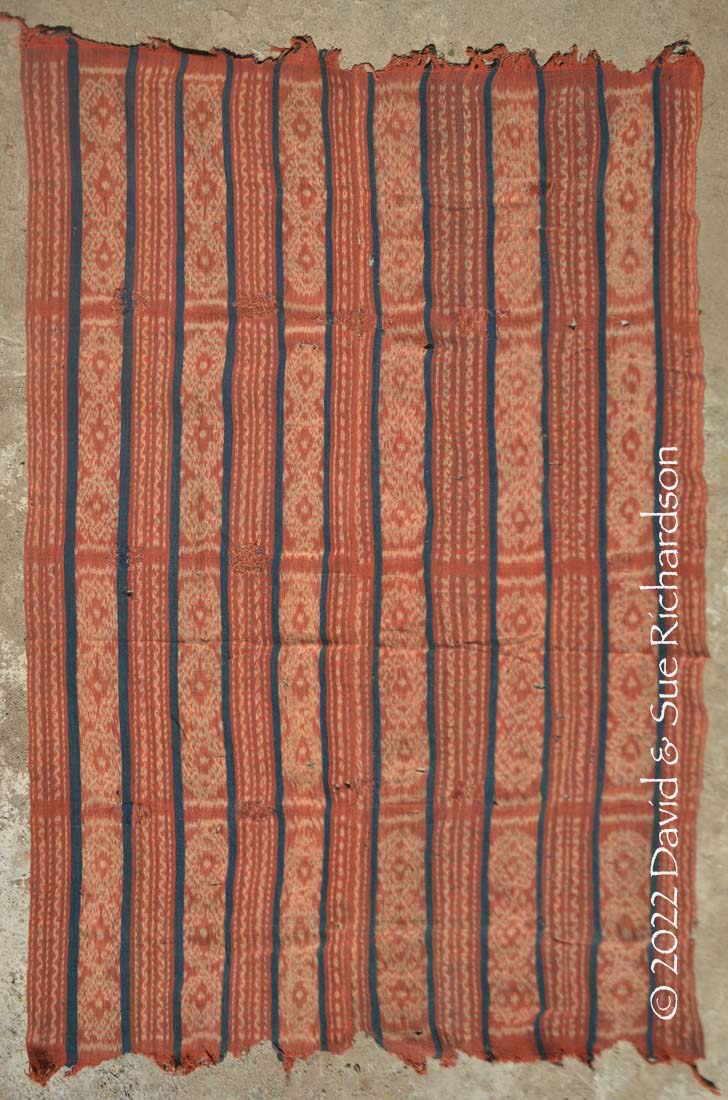

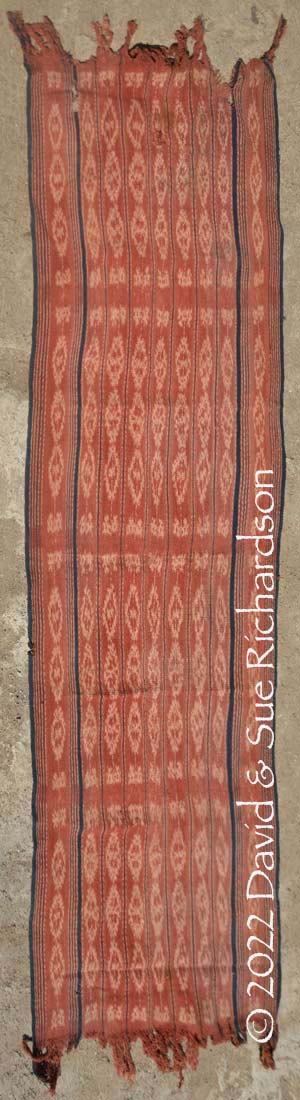

Èi Mea

According to Akiko Kagiyo, the èi mèa is the most basic of cloths and is easy to weave (2010, 214). Èi mèa were sacred cloths mostly intended not to be worn. They were used to wrap the deceased. In the distant past they were worn by warriors about to go to war.

Many èi mea appear to have been woven as miniature versions. The following three èi mea from Raijua in the Richardson Collection were collected in Kupang and Bali, so have no provenance. The fourth belongs to a family from Savu Raijua living in Kupang.

Above and below: two miniature èi mea from Raijua, sized 87 by 44cm and 78 by 41cm respectively. Richardson Collection

An èi mea from Raijua sized 110 by 41cm. Richardson Collection

A miniature èi mea. Private Collection Kupang.

When a wini decide to purchase a female water buffalo or mare to be used as a sacred symbol of that group, they must weave a large number of textiles, ranging from 20 to 36, in order to stage the Pehami ritual, held in the month of Bhanga Liwu Ro (May/June). An èi mèa is placed on the back of the water buffalo or horse and a necklace hung around its neck. The head of the animal is rubbed with dry copra and the wini pray for the animals and their members to be fertile (Kagiya 2010, 140).

Under certain conditions an èi mèa qualified to be a hara cloth, displayed at the Tao Leo festival for a deceased woman. A red cloth is the symbol of victory, courage, good harvests and fertility. At Tao Leo, red cloths are considered to bring wealth and happiness to people (Kagiya 2010, 176).

Return to Top

Èi Hebe Mea

The range of textiles that were once woven on Raijua appears to have been endless and one often encounters examples that lay outside of the main classifications.

This two-panel tubeskirt was described as an èi hebe mea, hebe referring to the floral motifs (hebe being a motif) and mea meaning red. It was woven two generations ago by an old woman who lived in the the kampong adat of Nada Ibu at Kelurahan Ledeke.

An old èi hebe mea from Nada Ibu in Ledeke. Richardson Colection

It was woven from hand-spun yarn that had been dyed with either indigo or morinda. The yarns in the patterned ikatted sections have been plied. The weft is indigo.

Return to Top

Èi Ledo

The èi ledo is a two-panel tube skirt with four plain black or blue narrow bands in each of its two panels. These are often decorated with narrow white stripes. The most common type of èi ledo has its main ikat bands or hebe decorated with the ledo serpent or snake motif.

The èi ledo is directly associated with hubi iki. It is obligatory for a woman from hubi iki to wear an èi ledo for her wedding ceremony. Although not mandatory, women from hubi iki are also supposed to wear the èi ledo as an everyday sarong.

An unusual èi ledo with the ledo motif and floral worapi end panels

Richardson Collection

Another unusual èi ledo with a different version of the ledo motif

Richardson Collection

An èi ledo decorated with the woore motif

Private Collection

An èi ledo owned by a family on Raijua

Raijuan dancers wearing modern èi ledo

While the èi worapi is usually used as a funeral shroud, if one is not available for a deceased woman from hubi iki then an èi ledo can be used instead.

Return to Top

Èi Beke Dara Womèdi

Another Raijuan sarong that defies classification is the all-indigo èi beka dara womèdi, beka meaning half, dara meaning inside and womèdi meaning black. It was woven in 2017 by Getreda Kana Koy at Ledeunu using raw cotton acquired in Maumere.

The èi beka dara womèdi woven by Getreda Kana Koy in 2017

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Èi Pudi

According to Raijuan oral history, the very first èi pudi mau was woven by Banni Kedo herself and was one of her favourite sarongs.

The èi pudi mau was originally a plain white tube skirt, considered clean. Consequently a woman wearing such a sarong was likewise considered pure, clean and beautiful. No other cloth has these characteristics. Today there are three kinds of èi pudi mau:

- èi pudi tie, the original white sarong,

- èi pudi mau dja’a, a simple indigo-dyed sarong with horizontal bands, and

- èi pudi mau wodattu, an indigo tie-dyed sarong made by using small stones or seeds.

According to Akiko Kagiya (2010, 195), the status of the èi pudi mau is peculiar. Its status as a sarong is low but its value is often equivalent to that of an èi wodattu. The èi pudi mau is just a simple cloth with indigo blue dyed horizontal bands. But because it is easy to dye and weave, it can be used freely and is often used as a substitute for the èi wodattu. An èi wodattu is precious and women would rather keep it in a basket than to wear it and get it dirty. Consequently if a woman’s ownership of an èi wodattu is known to members of other wini, she will wear the èi pudi mau instead.

There is also a strange exception in which the generally low-status èi pudi are regarded as high ranking. When it was occasionally decided to relocate an amu ina apu, perhaps to a more secure location following cloth thefts, it was necessary to perform the Dhede Haro Kedulu ritual, dhede meaning to lift and haro and kedulu referring to the kepepe haro and kepepe kedulu storage baskets (Kagiya 2010, 156). Some 36 pieces of newly woven high-status ikat had to be woven and placed in the relocated amu ina apu. These could include a pair of èi pudi tie and a pair of èi pudi mau.

Èi Pudi Tie

An èi pudi tie is an all white sarong, the wearer of which is considered clean and pure. Although pudi means white, it also means blank and is applied in this instance to mean without motifs.

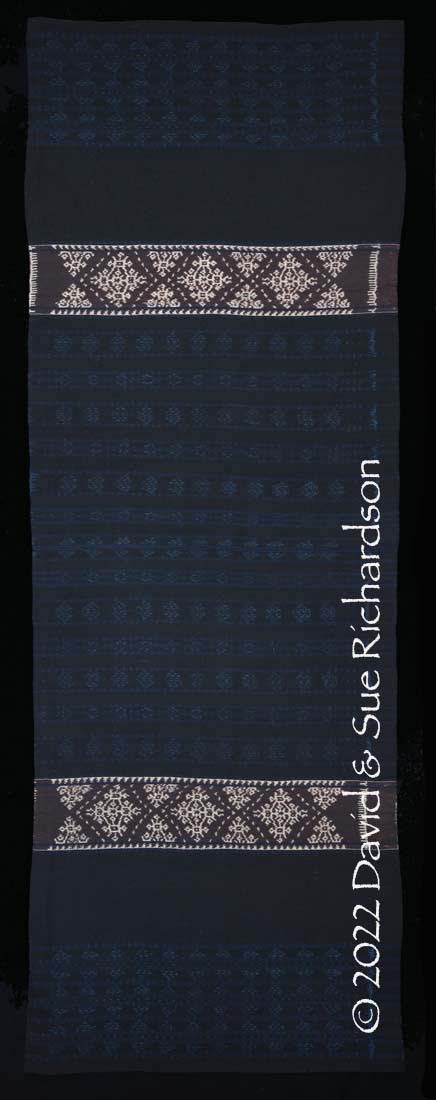

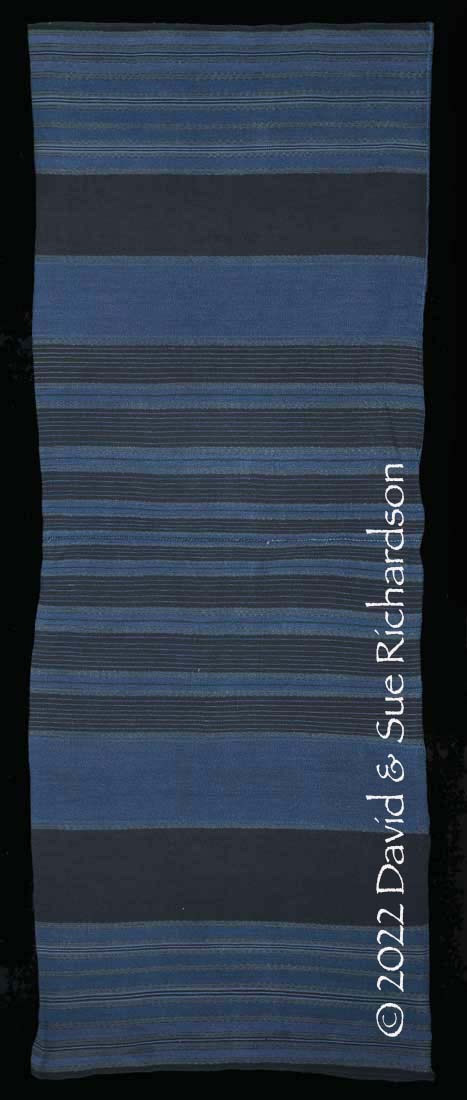

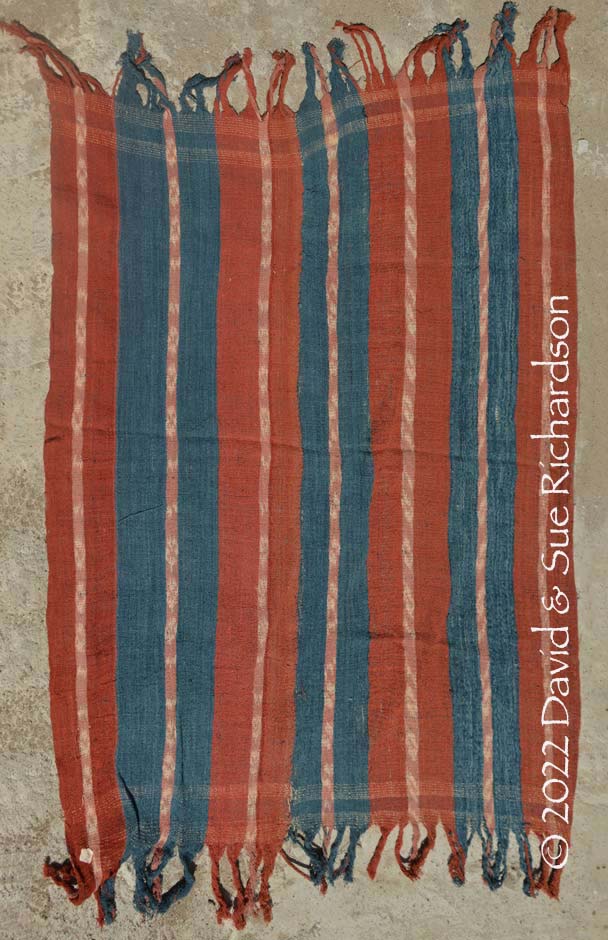

Èi Pudi Mau Dja’a

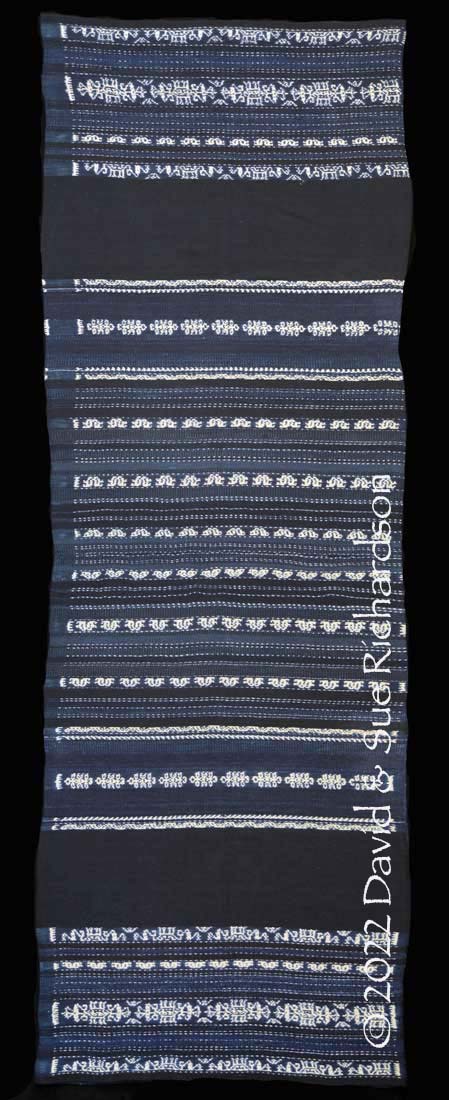

The èi pudi mau dja’a is a simple indigo-dyed striped sarong, dja’a refering to the process of colouring blue or black. These two-panel tube skirts are woven from local hand spun cotton that has only been dyed with indigo, known locally as tarum. The indigo is normally prepared in the rainy season, using seawater and lime. Èi pudi mau dja’a are decorated with wide lateral bands of light and almost black indigo, segmented by fine warp stripes.

An èi pudi mau dja’a woven by Naomy Laga Hahe from Kelurahan Lede Unu, who lives not far from Namo harbour. Richardson Collection

An èi pudi mau dja’a with no provenance. Richardson Collection

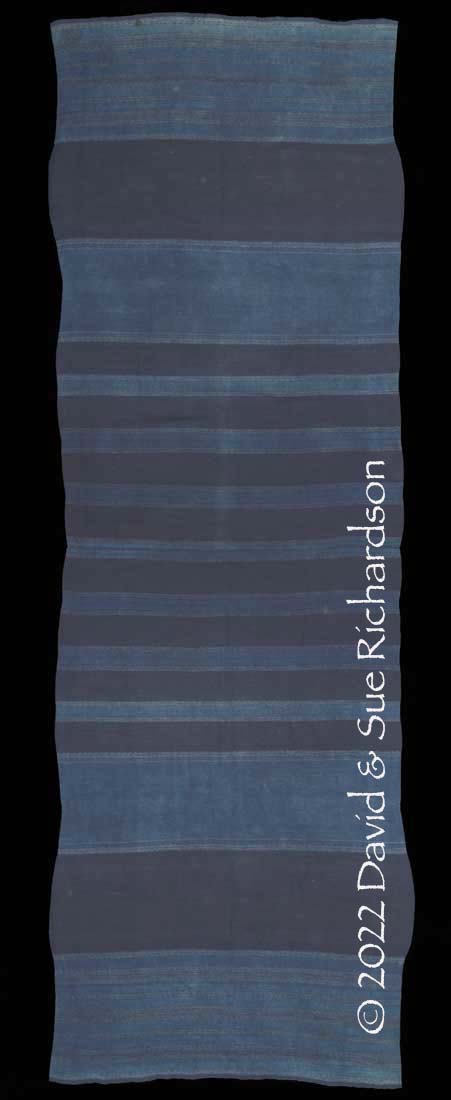

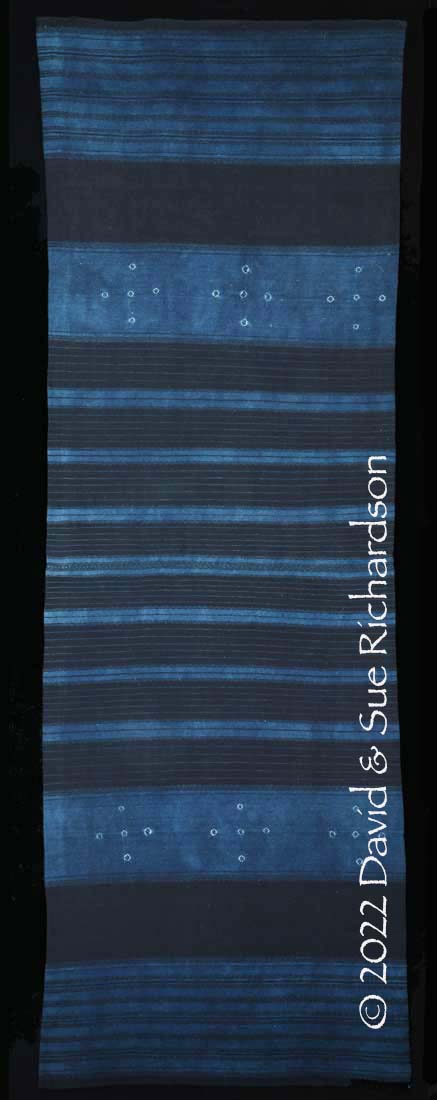

Èi Pudi Mau Wodattu

The èi pudi mau wodattu is a striped indigo-dyed sarong that is tie-dyed using mung beans, corn seeds or small stones. Such sarongs are considered easy to make and have the lowest status of all Raijuan sarongs. However as mentioned above, they are used as a substitute for an èi wodattu (a high status sarong with ikatted flower motifs coloured red, blue and white) and also as a funeral shroud.

The indigo panels are decorated with simple cross-shaped motifs composed of five small circles, created by the plangi tie-dye technique. They symbolise the flower of the lontar palm, which produces a sweet milky sap called tuak that flows when the stalk of the palm flower is cut.

Some writers have claimed that the terms ketaddu or dattu refer to the flower of the lontar palm. According to the Raijuan master weaver Getreda Kana Koy, wodattu actually means dot.

An èi pudi mau wodattu woven by Tila Mojo Hau and acquired from her elder sister, Lodia Doyi Hau. Richardson Collection

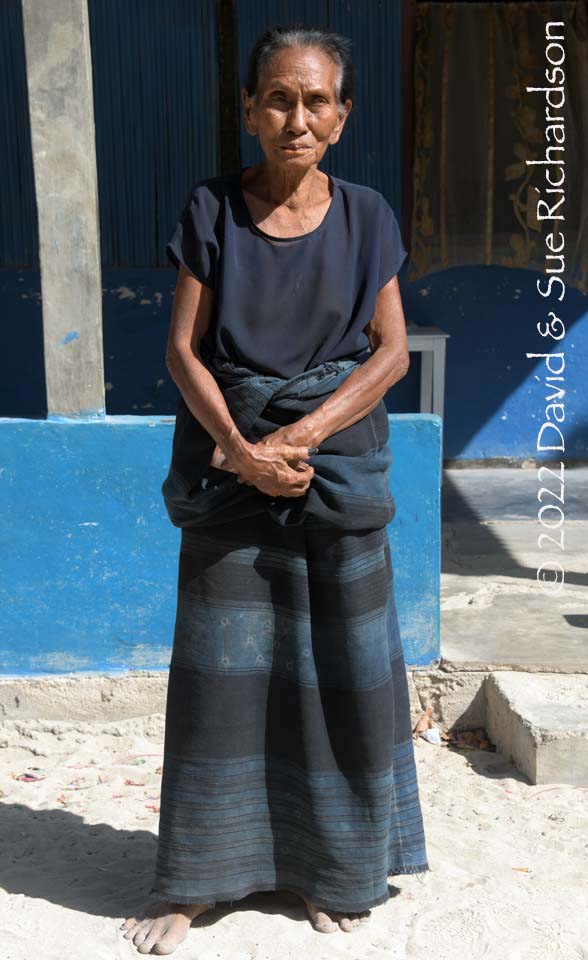

In recent years many èi pudi mau wodattu have been produced by master indigo dyer Getreda Kana Koy at her home in Ledeunu, which is close to the beach. Her yard is sandy, shaded by tall trees and gets the sea breeze, an ideal place to bind, dye and weave. Getreda belonged to wini Putenga, hubi iki, one of the two most powerful wini in hubi iki. When we visited her in 2019 it was obvious that she was still a very hard working woman, despite being 77-years-old. Yet despite being assisted by her son, she looked very weary and told us that her health was broken. Sadly she died in 2023 and the tradition of dyeing indigo on Raijua died with her.

Getreda Kana Koy wearing an old èi pudi mau wodattu in front of her home in Lede Unu

In 2008, Getreda Kana Koy formed a small weaving group called Mira Le Hari, composed of members of her extended family. They initially started to plant cotton once again but this initiative lost momentum and Getreda decided to obtain raw cotton from Flores Island instead. Nevertheless in 2018 her kelompok still had 10 members, making their indigo in the rainy season from a local, woody variety of indigo using sea water and lime powder. Getreda was helped with the tying and weaving of textiles by her daughter, Ibu Adin, and her son Pak Emanuel.

A batch of nine new èi pudi mau wodattu produced by Mira Le Hari in 2018

Return to Top

Èi Kubae and Èi Kemoru

Èi kubae and èi kemoru are sarongs that are stored in the kepepe in the amu ina apu without being worn for everyday use or for rituals. Because of this their ranking is uncertain, although some wini and kepepe give them a high rank. Thus kepepe Jingi Wiki ranks the èi kubae fourth and the èi kemoru fifth in status.

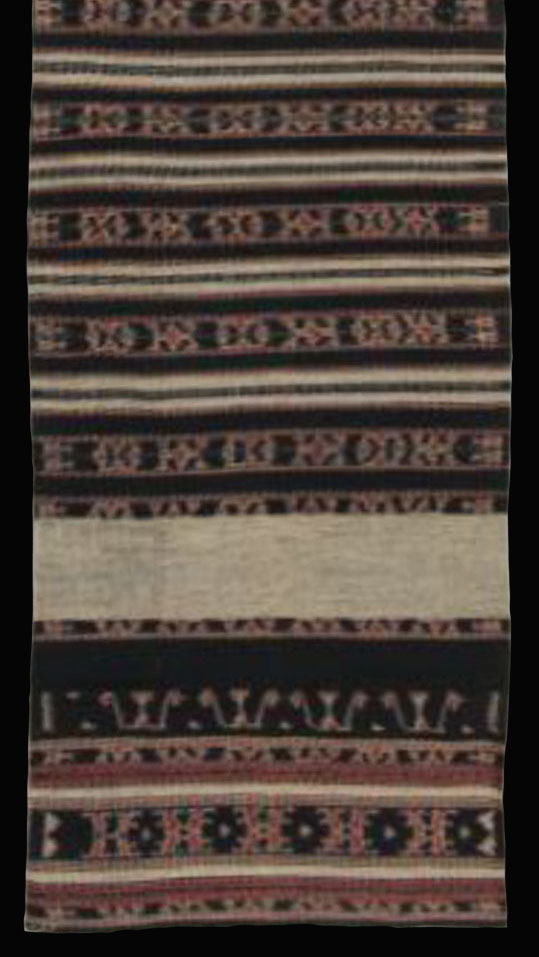

One panel of an èi kemoru

Private Collection

The èi kemoru has distinctive wide plain indigo and white bands in each panel.

A shrouded woman wearing an èi kemoru in Kelagamare Cave, the residence of Marega.

Photographed by Akikio Kagiya.

A miniature èi kemoru sized 84 by 36cm

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Èi Dua Hebe

The èi dua hebe has two main ikat bands and is therefore considered more valuable. A woman was obliged to wear either an èi dua hebe or an èi huri wue if she visited Udju Koro, the former residence of Banni Kedo, to make offerings.

Return to Top

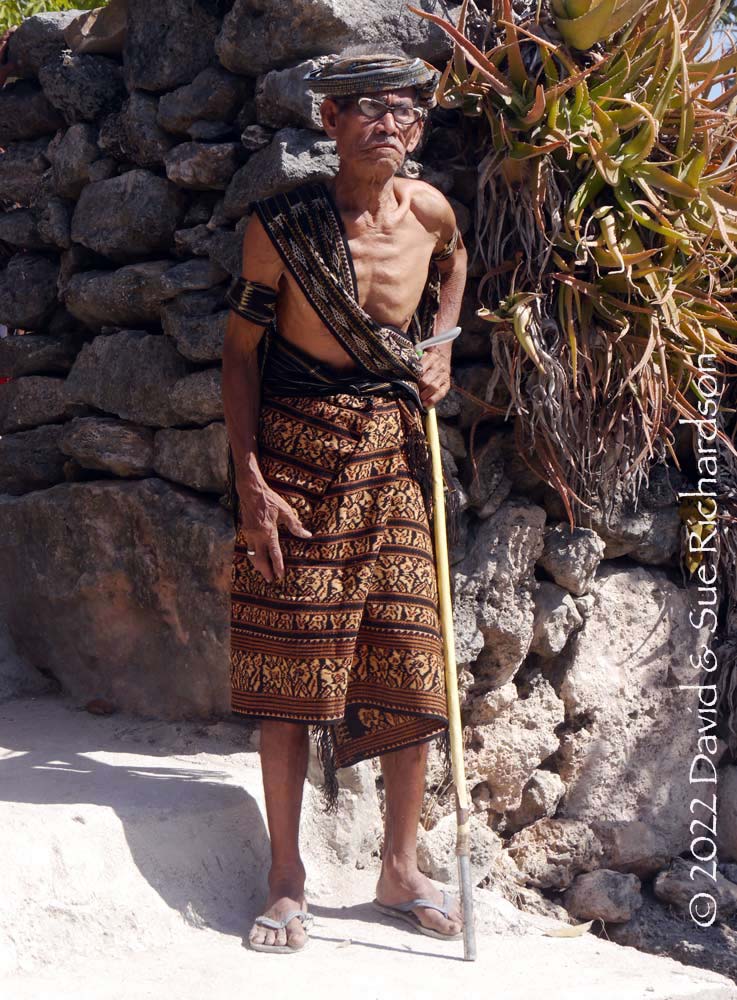

Men's Costume

Men traditionally wore two rectangular cloths, a fringed hip wrapper and a shoulder cloth, both called a higi (or hig'i on Savu Island).

Leonard Albert Lai Kudji wearing a higi worapi and shoulder sash at the royal enclosure of Udju Dima. He is the great grandson of the last Raja of Raijua, Ama Meda Lai Kudji

The most traditional hip wrappers are called higi womèdi and have ikat bands that are just indigo and white. More modern cloths contain bands with three or more colours and are known as higi worapi.

Higi always have a central field composed of a cluster of narrow ikatted bands, which are known as huri. They contain rows of motifs, known as hebe. Normally the number of huri is an odd number that can range from five, seven, nine, or even more if the motifs are small. Some higi have fifteen, seventeen and even nineteen huri. The greater the number of rows – the higher the status of the wearer and the more valuable the cloth. The huri are sometimes flanked by plain narrow blue of black bands called roa. The two outer edges of the higi are decorated with a cluster of narrow stripes called dini flanking a central ikat band, which together are called the wurumada or delicate eyes. The central band of the wurumada is normally decorated with the same band of motifs used in the central field huri.

Higi can be woven as single cloths or can be made from two pieces of unequal-size. In the latter case the larger piece has one more band of motifs than the other. Twisting the fringes of the higi is considered men's work, and is normally accomplished by the owner while he is relaxing.

Just like Raijuan women’s èi, higi are ranked in status and valued in comparison to a female water buffalo, a rena kebao. The highest status cloths are worth one whole buffalo and the lower status cloths are valued in fractions of a buffalo:

| Rank | Name> | Description |

| 1 | Higi Taba or Rena Kebao | A sacred two-panel tube skirt, regarded as the ikat for a queen. It must be stored as a pair with an èi taba in the amu ina apu. |

| 2 | Higi Worapi or Huri Wue | A two-panel blanket with white, dark blue and morinda red ikat bands. |

| 3 | Higi Mea | A two-panel blanket with red, white and blue ikat bands. |

| 4 | Higi Pudi Wo Le Rai | No description. |

| 5 | Higi Wohappi | A two-panel blanket with ikat bands decorated with lozenges. |

| 6 | Higi Pudi | A two-panel white blanket. |

As with women's cloths, each hubi employed a basic motif for the corresponding male cloths. Originally the basic motif for each hubi was based on an elongated diamond called a wohèpi, reminiscent of the diamond wo kelaku motif of the female sarong. For the hubi iki the sides of the lozenge were unbroken. For the hubi ae the diamond was more elongated and the two sides divided by a line of plain weaving.

Diamond-shaped wo kelaku motifs on a higi for a man belonging to hubi ae

Over time the hubi ae developed a new motif from the basic wohèpi. Called a boda, it looks like an elongated stepped diamond surrounded by tiny diamonds. In some domains individual wini have their own motifs.

Men traditionally wore a narrow cloth belt called a wai. It was long and narrow and generally plain-woven dark indigo with red, light blue and white warp stripes.

Return to Top

Higi Taba

The higi taba is a two-panel cloth for a man. However in this instance it is not a blanket but a two-panel tube skirt, although one that is shorter and narrower than the éi taba.

A very fine example of a higi taba photographed by Akiko Kagiya

When stored in the amu ina apu the higi taba must be paired with an èi taba. As previously mentioned, calling this blanket a higi taba invites illness, so they are always referred to as a rena kebao, a female water buffalo. On Raijua female water buffalo are never killed whereas male water buffalo will be sacrificed at the matrilineal group’s Pemeringi Kebao ritual once they grow to the right size. One rena kabao is equivalent in value to one female buffalo, making it the highest value cloth on the island (Kagiya 2010, 113).

Each wini uses a different motif for their rena kebao. In the higi taba, the dini, the lines of ikatted dashes that border the main motifs, are red and white, not black and white as in the èi taba.

In the past these were taken from the amu ina apu to be worn by a warrior in a headhunting expedition to offer protection. More recently they were occasionally used as a funeral shroud but only for a certain number of men who qualified according to the extremely strict rules defining their permitted use. This was for those matrilineal groups that qualified for holding the Penuni festival, the highest-ranking form of the extravagant and expensive Tao Leo funeral festival. In such instances a new higi taba had to be woven for the funeral ritual.

When attending a cockfight, known as a daba, it was customary for the leader of each udu to wear a higi taba and carry a spear, in remembrance of the time of the headhunting wars (Kagiya 2010, 126). The higi taba is considered a sacred ‘hot’ cloth.

According to local legend, in hubi ae, Marega wove the very first rena kebao for her brother, Lado Ga (Kagiya 2010, 116). In hubi iki, Banni Kedo ordered Banni Dare Dahi to weave the first pair of rena kebao for her brother, Maja.

Return to Top

Higi Worapi

The higi worapi has parallel longitudinal hebe that have been dyed with three colours – red, white and blue-black. This is a relatively new style of ikat that emerged during the nineteenth century under the influence of Dutch colonial rule and the Protestant church. The higi worapi can be worn by either hubi, although each use their own selection of motifs.

The higi worapi was usually used for a man’s funeral shroud.

Possession of a higi worapi or an èi worapi is an essential requirement for a wini or kepepe to qualify for staging a Tao Leo funeral feast.

A modern higi worapi belonging to a man on Raijua.

Raijuan dancer wearing a modern higi worapi at Udju Dima

Musicians belonging to the local Ledeunu sanggat. Three are wearing modern synthetically dyed higi worapi and one a higi pudi.

In the past traditional men’s hip wrappers were dyed with not two colours but just one – indigo. They were known as a higi womèdi, mèdi meaning black. Depending on the number of immersions, the actual colour varied from light blue to near black.

A man’s higi womèdi with 13 central ikat bands or huri decorated with the wo hèpi motif. Private Collection Kupang.

Return to Top

Higi Huri Wue

The higi huri wue appears to have had a central field that is not decorated with parallel longitudinal huri bands but is either filled with much bolder motifs or with a distinctive lattice of diamonds. They seem to have been relatively less common.

Return to Top

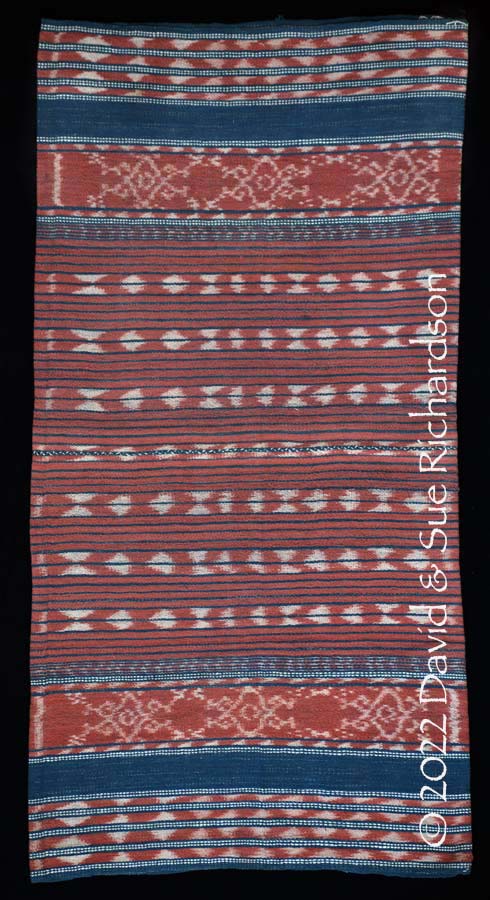

Higi Mea

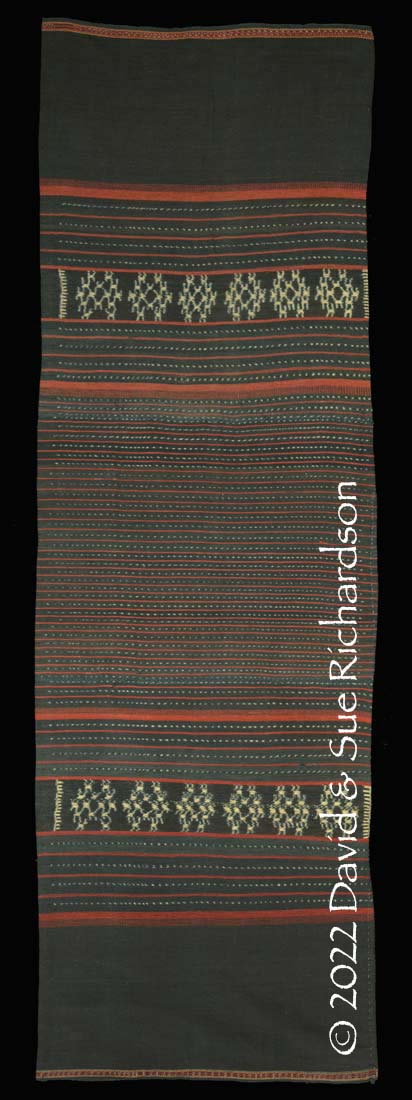

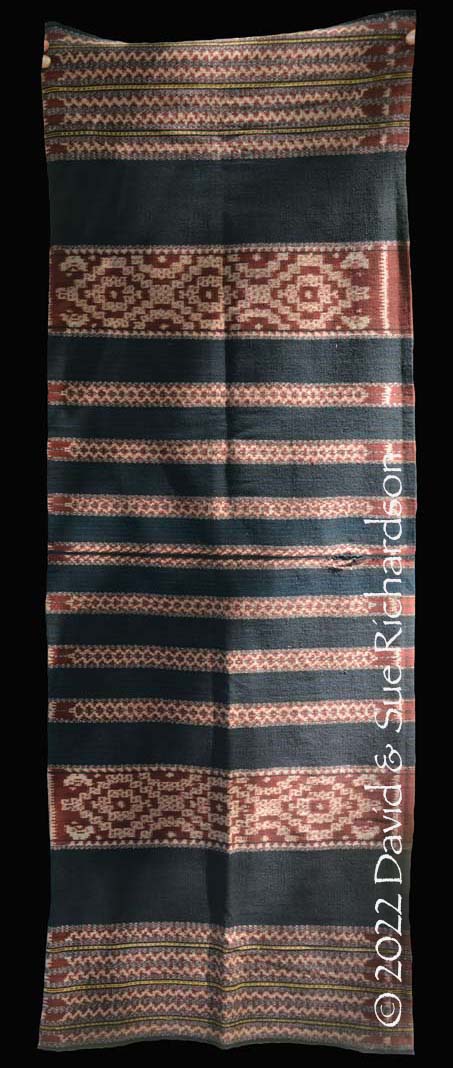

The higi mea is woven in a wide range of forms but is generally decorated with a central field composed of a cluster of narrow ikatted bands or huri that have been dyed with morinda rather than indigo. In some examples the huri are flanked by plain indigo stripes in others they are not. Higi mea are woven with both an odd and even number of huri.

A large higi mea wrapper with six main huri. Private Collection Kupang.

Large rectangular higi mea were worn by Jingi Tui priests, the hereditary Mone Aa, during religious rituals. Higi mea are also often used as hara cloths to be displayed at the funeral festival for a man.

The higi mea often fulfils the role of a daba cloth – a hip wrapper worn to the ritual daba cockfight. This is because the red symbolises braveness and daring. Only the elder son can inherit the daba cloth and if it wears out only the man’s sister can weave a new one, since it is considered shameful if one is woven by his wife.

A narrower higi mea with six main huri. Richardson Collection

Some higi mea are woven with wide plain indigo bands rather than stripes. In these examples the ikat decoration on the red bands is much more simple.

A large higi mea wrapper with nine narrow huri. Richardson Collection

A somewhat similar example owned by a family from Raijua

A very simple and small higi mea. Private Collection Indonesia.

Above and below: narrow higi mea, the first example decorated with the wo hèpi motif

Private Collection Indonesia

There are several subcategories of higi mea such as the higi mea worapi and the higi mea wodattu, the latter decorated with painted spots.

The higi mea worapi is worn by the eldest son during the Pana Jami ritual, the second grand festival held every six years and dedicated the powerful male ancestor Maji. It should ideally be woven by the man’s sister, although it is acceptable if it is woven by his wife.

Return to Top

Higi Pudi Wo Ie Rai

We have been able to find no information about this mysterious higi.

Return to Top

Higi Wohappi

The higi wohappi is very similar to the higi worapi, the principle difference being the design of the lozenge-shaped motif.

The motif used on the Raijuan higi wohappi differs from that used on the Savunese hi’i wohappi. It is an elongated lozenge similar to the wohèpi with closed ends, except in this case one end is open and encloses a smaller elongated lozenge, somewhat like and open mouthed fish swallowing a minnow.

The Raijuan wohappi motif

The higi wohappi is sometimes used as a substitute for the higi worapi. Thus if a wini has no higi worapi for a man’s funeral shroud a higi wohappi can be used instead (Kagiya 2010, 118). At the Penuni funeral festival, the highest rank of Tao Leo, it was necessary to display 24 pieces of hara cloth. These were placed in a kepepe basket to be carried to the mourning house with a higi taba spread on the bottom. If a higi taba was not available it could be substituted by either a higi worapi of a higi wohappi (Kagiya 2010, 182).

A set of hara cloths on display at a Tao Leo festival with a higi wohappi hanging centrally. To the right is a wai ae, a higi taba and a plain red cloth symbolising the sail of a boat. Photographed by Akiko Kagiya.

Return to Top

Higi Pudi

The higi pudi is a plain, all white two-panel hip wrapper with fringed ends woven from undyed cotton. It is sometimes called a higi wopudi. As previously mentioned although pudi means white, it also means blank and is applied in this instance to mean without motifs.

On Savu such hip wrappers were worn by rulers for official gatherings during times of peace, white being considered cool while red is considered hot. Photographic evidence shows many Rajas dressed in hi’i pudi alongside important Dutch colonial officers, suggesting that they were also worn for diplomatic events.

Several historical reports dating from the second half of the nineteenth century suggest that the white higi pudi was common on Raijua at that time, far more so than on Savu.

Higi pudi may have also been worn by bridegrooms at their weddings.

On Raijua today higi pudi are mainly worn by local sanggar cultural groups for their traditional dance performances.

A male dancer wearing a higi pudi at Udju Dima

Return to Top

Funeral and Other Sacred Cloths

In the past woven belts played an important role as sacred cloths that offered personal protection or were essential for preforming funeral rituals. All of these cloths were considered to be imbued with special power and were treated with a high degree of respect.

Wai Made and Wai Wake

The wai made (‘the belt for the dead’) and the wai wake were simple small sashes, roughly 300cm wide and up to 1.2 metres long. They are dark indigo with narrow red and white stripes, the number of stripes varying according to the moiety of the group. Thus these belts have 7 stripes for the hubi ae and 5 stripes for the hubi iki. Regarding use, the wai made is a loincloth while the wai wake is a waist belt. They are especially used for funerals, both being placed on a brother’s body when he dies.

It was traditional for every male individual to own a wai made and a wai wake. It was the responsibility of the eldest sister to weave all the wai (and the higi) for all her brothers, although her younger sisters were allowed to assist her (Kagiyo 2010, 54). This placed a heavy burden on the eldest sister of the family.

Should a brother die, it was the responsibility of his sisters to clean the corpse and to wrap it in textiles and cover it with shroud.

In the case of any death, whether male or female, it was the responsibility of the maternal uncle to oversee the burial and to bring a wai to tie the shrouded corpse of the deceased.

These small wai also serve as cushions for supporting rena kebao cloths, regarded as the queen of ikats, when they are used in rituals.

Wai Mea

There was an equivalent wai mea 'red belt', which was intended to be worn by a man to provide protection during periods of acute danger. In the past they were always worn by a man when he set off on a journey. It was especially required if crossing the dangerous Raijua Strait on a voyage to the main island of Savu, where people drowned almost every year. If a man was lost and his higi and or wai were later recovered, he could be identified by the motifs or stripes on the cloth. If no body were found, the cloth could be treated as a dead body and the funeral would proceed. However if neither body nor cloths were recovered, no funeral would take place and no mourning was permitted.

Wai Labe

The wai labe (‘the belt to cover [the corpse]’) was the name given to a wai made or wai wake when it was used for a funeral.

If the deceased was a woman, the corpse was dressed in an èi mea or red sarong that was smaller and narrower than a traditional sarong and was decorated with the primary motif of her hubi. It was then tied under the armpits with a narrow wai labe. She was then dressed in several additional ceremonial sarongs appropriate for her wini.

If the deceased was a man, the corpse was dressed in wai labe and then wrapped and covered with several hi'i mea red blankets, which had bands of red ikat separated by bands of plain indigo.

Both types of funeral cloth were woven very coarsely.

Wai Huri

The wai huri was a small ikat belt decorated with motifs (huri). It was one of the seven wai required as part of the 25 hara cloths displayed at the funeral of a man who qualified for the Penuni, the highest status form of Tao Leo festival.

Wai Ae

The wai ae is a big and heavy indigo belt with plain warp stripes and fringes, ae meaning big or large. Wai ae are roughly 12m long and 0.5m wide.

The wai ae is considered a symbol of the brother whereas the rena kebao is regarded as the symbol of the sister.

In the nineteenth century when Raijuan warriors went on a headhunting raid or were recruited to fight wars on Timor, their sisters would come to their brother’s house to weave a wai ae and a rena kebao under the supervision of the eldest sister. Both textiles were considered to have amuletic powers and were gifted to the brother before his departure. In preparing for a battle, the rena kebao was fastened under both arms while the wai ae was firmly tied over it and wrapped around the chest. These layers of cloth protected the torso like a suit of armour, having the same function as the very similar long and heavy rohu banggi used by Sumbanese warriors.

Because of this the wai ae and the rena kebao are always considered a pair and must be stored together in a kepepe basket inside the amu ina apu. At the same time the èi taba and the higi taba must be paired together, thus requiring them to be stored with two wai ae.

In more recent times, the wai ae was one of the high status cloths that were required to be woven in order to perform various rituals. It also played a role as one of the ritual hara cloths that were displayed during the Tao Leo funeral festival.

Today the wai ae is only a memory. By the mid-1990s, almost all of the valuable cloths on Raijua had been stolen, including all of the wai ae. With no reason to use them any more, they ceased to be woven.

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

It would not be possible to discuss the wide range of Raijuan textiles listed on his webpage or their deep cultural significance without the extensive 31 years of research conducted by Akiko Kagiya on Raijua Island. Sadly her work is difficult to access and therefore hardly known in the textile world.

We are also grateful to Pak Titus B. Duri, the camat of Kecamatan Raijua, and his wife for welcoming us to Raijua and for transporting us around the island, and Pak Leonard Lai Kuji for allowing us, along with our annual textile groups, to enjoy the cultural performances inside the royal enclosure at Udju Dima.

Getreda Kana Koy and her son Emanuel, along with the rest of the Mira Le Hari weaving group at Ledeunu, as well as Gena Lakki in Ledeke, have proved valuable informants about Raijuan textiles.

We also wish to thank Geneviève Duggan for providing us with advanced information about the island and its weaving culture.

The authors with Getreda Kana Koy at Ledeunu

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 4 February 2022.