Asian Textile Studies

Contents

A Fragmented History of Ilé Apé and its Textiles

Women's Sarongs

Wate Mohle or Wate Kerokong

Wate Buraken

Wate Topon or Wate Krokon

Wate Kebo Lolon

Wate Hebaken or Wate Hebak

Wate Ohin or Wate Bala Ohi

Wate Ohin Motifs

The Revot on Ilé Apé

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Ilé Apé Textiles 3 - Coming Soon

Watek Senewaken

Tenépa

Wate Nai Pa

The Influence of Indian Patolu

Kewodu

Nowing

Senai

Bibliography

Introduction

The Ilé Apé District

Ilé Apé Ethnography

Local Cotton and its Processing

Binding

Natural Dyes

Indigo

Morinda

Moringa

Réo Bark

Tenor Bark

Mango Bark

Tamarind

Natural Black

Turmeric

Weaving

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

A Fragmented History of Ilé Apé and its Textiles

Melanesian hunter-gatherers were probably active around the coasts of Lembata Island in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene (20,000 to 10,000 BP), possibly long before then. During the Last Glacial Maximum (about 21,000 BP) sea levels were about 134m lower than they are today (Lambeck et al 2014). Consequently Flores, Solor, Adonara and Lembata were joined in one landmass that was separated from Pantar by the deep Alor Strait. Pantar in turn was linked to Alor by a narrow land bridge incorporating Pura Island. We know that hunter-gatherers were present at the Tron Bon Lei rock shelter near Lerabaing on the south coast of Alor at this time, surviving on a diet of reef fish (Samper Caro, O’Connor et al 2016). As early as 1894, Ten Kate had clearly seen what he referred to as a negroid influence in the population of Lembata. In 1931 the physical anthropologist Johannes Kleiweg measured nine skulls from Lembata and detected a strong Papuan inheritance.

At some point around 1000 BCE this small population of Melanesians was joined by Austronesian-speaking immigrants, probably arriving from southern Sulawesi. A recent genetics study identified close genetic links (common genetic polymorphisms) between the populations of Lembata, Alor, Pantar and Timor and the people of Sulawesi (Hudjashov et al 2017). The same study estimated that the mixing of Melanesian and Austronesian genes took place quite late, between 500 and 0 BCE. This does not of course indicate the date of the Austronesian arrival, but rather the date at which the two populations began to significantly interbreed.

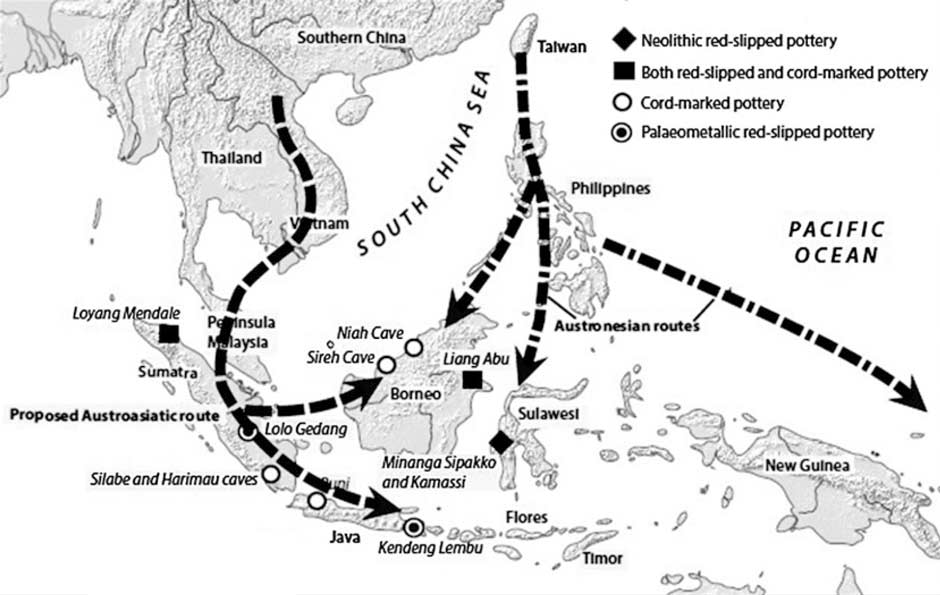

The two proposed routes of Neolithic migration - Austroasiatic and Austronesian

After Simanjuntak 2017

Archaeological evidence is currently sparse, but suggests a somewhat later date for the Austronesian arrival. The Neolithic urn burial site of Pain Haka on the coast of Hading Bay in East Flores dates from around 1000 BCE (Gallipaud et al 2016), and a similar site at Melolo on Sumba Island dates from a similar period (Bulbeck 2017, 150-157). The interaction between the Austronesian-speaking immigrants and the endemic Melanesians undoubtedly led to the emergence of the proto-Lamaholot language, which contains a substratum of non-Austronesian words. It is assumed that the Austronesian immigrants were responsible for the introduction of weaving.

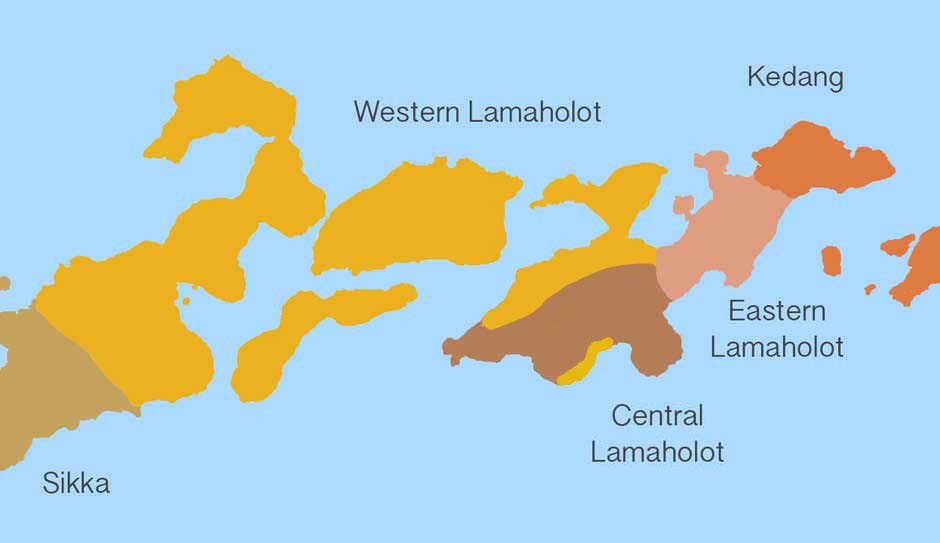

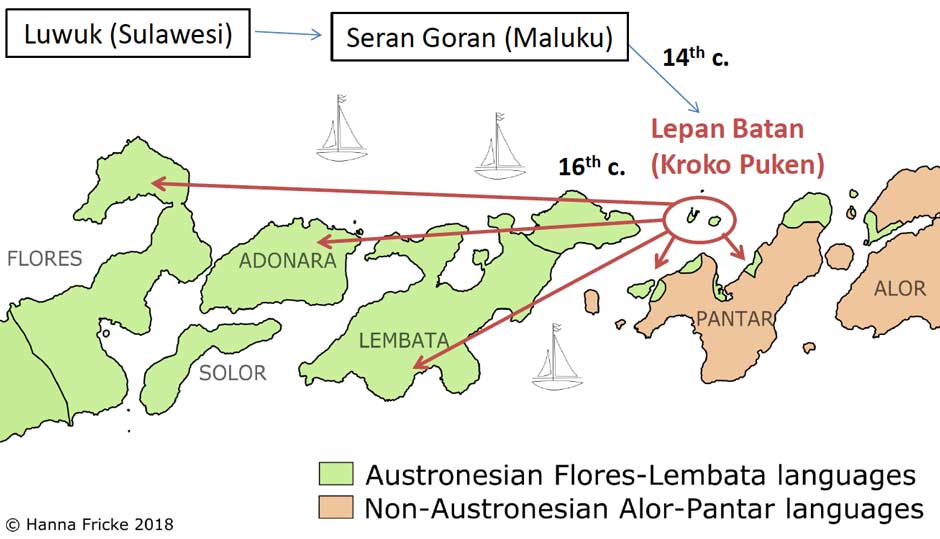

The distribution of Lamaholot sub-groups after Fricke 2019

Linguistic analysis suggests that the Proto-Flores-Lamaholot (PFL) language materialised in central Lembata, before spreading to peripheral parts of the island and to the islands to the west (Fricke 2020). At some time prior to 1300 AD this had fragmented into the Proto Central Lamaholot (PCL) language of southern Lembata, the Proto Eastern Lamaholot (PEL) of east Lembata and the Proto Western Lamaholot (PWL) spoken in northwest Lembata and Adonara Island (Fricke and Klamer 2018). Western Lamaholot subsequently spread from Adonara to Solor and East Flores.

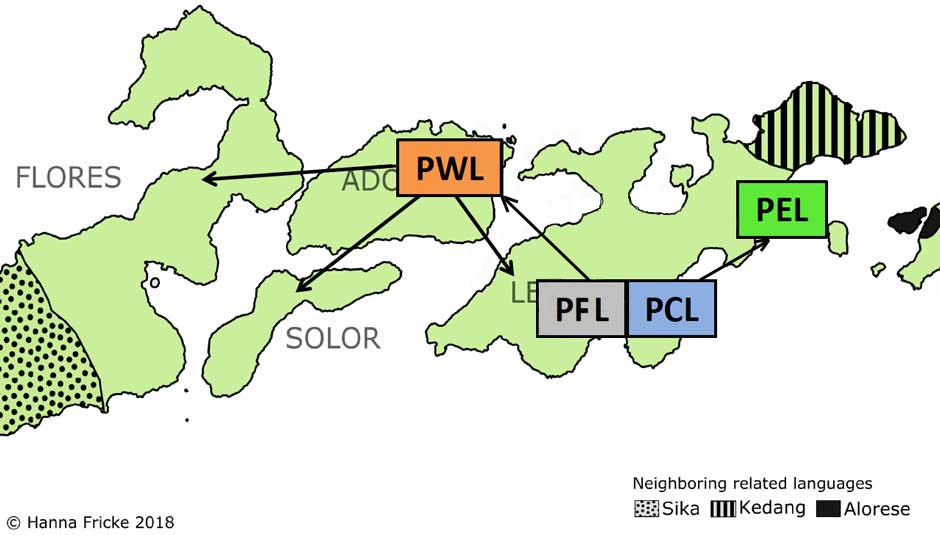

Language migrations from the Lamaholot homeland prior to 1300

Reproduced with the permission of Hanna Fricke and modified according to her advice

According to Keraf (1978), the language of Ilé Apé is quite different from the other languages spoken on Lembata. It belongs to Western Lamaholot and is very similar to the language spoken on Adonara (Fricke 2020). This suggests that the people of Ilé Apé have a different language history from the other inhabitants of Lembata.

Beckering (1911, 186) had already noticed in 1910 that the residents of Ilé Apé were different from the other people on Lembata. They were more likely to have frizzy hair like the inhabitants of Adonara and some were big and powerful figures. They also spoke a language that was similar to that found on Adonara. The closeness of their two dialects has led Hanna Fricke (2020) to suggest that Ilé Apé may have been populated by Western Lamaholot speakers coming from adjacent Adonara.

Local Lamaholot narratives describe a later influx of immigrants from a place called Kroko Puken – the twin islands of Lepan and Batan located beyond the eastern tip of Lembata. It seems that Kroko Puken was struck by a catastrophic natural disaster, possibly a tsunami. The myth of origin of the whale-hunters of Lamalera says that ‘the seawater rose up causing everyone to flee’ (Lundberg 2003, 79). As the island was evacuated, its refugees sought new homes on Pantar, Lembata, Solor, Adonara and East Flores. Vatter (1932, 10) estimated this event may have occurred in the mid to late seventeenth century, but Barnes (1982, 411) thought that this was too late and proposed an earlier date of around 1450. More recently Hanna Fricke has reported Thomas Ataladjar’s view that the disaster occurred between 1522 and 1525 (2019, 15).

Ataladjar’s analysis is partly based on the logbook of Francisco Albo, the pilot on Magellan’s Victoria, the only one of five Spanish ships to have completed the circumnavigation of the globe. On 8th January 1522, ten days after leaving Ambon, the Victoria entered the channel between the islands of Lamaluco and Aliguom, passing two small but inhabited islets on the right hand side (Albo 1874, 232). Following Le Roux, Ataladjar assumes the two main islands are Lembata and Pantar while the two small, inhabited islets are Lepan and Batan. Antonio Pigafetta, the expedition’s journalist, produced a crude chart showing a small island named Batuombor to the north of Galiau (Pantar). Was this the mountainous islet of Batan?

Ataladjar concludes that the disaster that befell Lepan Batan must have occurred between 1522 and 1525 because people from those islets were already present in Larantuka when Sira Napang became king in 1525 (Ataladjar 2015, 37).

Migrations from Lepan Batan

Reproduced with the kind permission of Hanna Fricke

Many of the escaping refugees sailed westwards, some passing along the south coast of Lembata and others along the north coast. The former initially settled in Labala Bay before relocating to southern Ata Déi and Lamalera. The latter bypassed Ilé Apé because of its lack of fresh water and its harsh terrain that was unsuitable for agriculture, settling on Adonara and the eastern end of the Flores mainland. If the oral narratives are accurate, this would imply that Ilé Apé was far less affected by the immigrant culture of Lepan Batan than was Lamalera or Ata Déi.

According to Ataladjar, the oral histories describe a life on Lepan Batan that was typically Lamaholot, with stone terraced fields, beliefs in the deity Lera Wulan Tana Ekan, ceremonial korke-bale clan houses containing clan heirlooms and nubanara sacred stones (2017, 18). One poem even suggests they spun yarn from the fibres of widuri, also known as milkweed or kolon susu (Hull 2006, 34). Milkweed is still spun today on Ternate Island in the Pantar Strait. Hanna Fricke has proposed that the inhabitants of Lepan Batan might have also spoken Western Lamaholot, thus explaining how they integrated easily into Lembata society (2019, 15).

Apparently Lepan Batan also had a safe harbour called Leffo Hajjio and was linked to northern Pantar. It also sat at the crossroads of two major sea routes – the spice route from Malacca to Banda, and the sandalwood route from Timor to Makassar (Ataladjar 2017, 19). Although Waienga Bay on the north coast of Lembata also offered a safe anchorage, it had no coastal ports where seafarers could have traded with the mountain dwellers of Ilé Apé.

An oral narrative describing the history of Lewohala might suggest that a few immigrants from Lepan Batan may have reached Ilé Apé later, by way of Adonara (Sumber Group Orang Baopukang 2015). Apparently migrants who had settled at Waiwuring on the east coast of Adonara, and at Sagu Arang on the north coast of Adonara, were affected by a leprosy epidemic. They decided to find a new home and sailed to neighbouring Ilé Apé, some settling at Lewotolok on the north coast and others at Lewohala on the eastern flank of Ilé Apé.

Because the colonial powers had no commercial interest in Lembata it is one of the few islands where we have no early historical records describing its people, their activities or their costume. Although the Dutch surgeon Wouter Schouten left us a brief account of Lembata when he visited the island with a large Dutch fleet in 1660, he sadly made no reference to the costume of the inhabitants or to any tradition of textiles or weaving. He did record that the people of Adonara were retiring and went naked apart from a loincloth, while the inhabitants of Solor were bolder and came out in their canoes every day to visit the fleet and to barter their food in return for cotton cloth, which they much preferred to money (1676, 80). It seems likely that loincloths were also once worn on Ilé Apé as they were on Pantar, Alor and Timor - although no hard evidence to support this has yet been uncovered.

For the following two centuries there is no reference to Lembata in any of the Portuguese or Dutch records. As late as 1849 the Dutch naturalist Coenraad Temminck observed that ‘Lombelm’ and Pantar were still completely unknown lands – just white spaces on the world map (Temminck 1849, vol. 3, 187). In 1851 the Dutch Resident at Kupang reiterated that Lembata was still little known, adding that it remained neither a Dutch nor a Portuguese possession – it apparently had no foreign settlers. Given the Dutch policy of non-intervention, and the lack of any colonial interest in Lembata, Dutch knowledge was limited to the coasts. No European had yet explored the interiors of islands such as Lembata and Alor (Donselaar 1882, 272).

The first missionary activity started in 1886 following the arrival of two Jesuit priests from Larantuka in Lamalera, who returned annually for the following few decades. At that time parts of the island were either subject to the Catholic Raja of Larantuka or the Muslim Raja of Adonara, based at Sagu on the north coast of that island (Barnes 1986, 300). The former ruled over the Demon mountain people in the hinterland of Lembata as well as Lewolein and Lamalera, while the latter ruled over the Paji coastal peoples of Ilé Apé (Lewotolo), Kédang, Labala and Mingar.

A woman's bridewealth cloth from Ilé Apé attributed to the nineteenth century and mysteriously labelled a nelang tetu. Honolulu Museum of Art (accession no. 10534.1)

It was not until the Dutch changed their policy towards the ‘Outer Islands’ that we obtained our first insights into life on Lembata. Having only just brutally crushed a 30-year-long insurgency campaign in Aceh, General Colonel Joannes van Heutsz was appointed Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies in 1904. Faced with numerous ongoing local insurrections across the Outer Islands, van Heutsz realised that stability and prosperity would require a new hands-on approach, taking away the authority of native leaders and installing strong local rule. Military operations were implemented in quick succession – in south-eastern Borneo in 1904, in southern and central Sulawesi in 1905, in Bali in 1906, on Sumba in 1906, on Flores in 1907 and on Sumbawa in 1908 (Groen 2018).

It was not until 1910 that Captain J. D. H. Beckering was despatched from Kupang with a company of troops tasked with registering the population of Lembata and confiscating their weapons and firearms. Beckering estimated the island’s population to be 31,000 to 32,000, mostly inhabiting villages located at easily defended sites on the slopes of the four highest mountains and in other highland regions – the coastal plains were virtually uninhabited. The implication was that the island hid a violent past. Apart from a few Christians in Lamalera and the Muslim community around Kalikur, the island was entirely pagan.

Sadly Beckering left us few insights into local textile production or costume. With the exception of Kédang, it seems that weaving was widespread on Lembata since all the women in the mountain kampongs understood the art of weaving (1911, 196). Sarongs were woven in the beach kampongs like Kalikur to sell to the mountain population of Kédang. The clothing of Lembata was the same as that on Adonara, although there were differences in the jewellery.

Despite Lamalera having more political influence than other parts of the island, the Dutch set up their administration at the more accessible Hadakewa in Waienga Bay.

Just before then, on 9 November 1928, the German ethnographer Ernst Vatter and his wife Hanna arrived in Larantuka on a small Dutch steamboat, having left Surabaya eight days previously. His objective was to acquire artefacts for the Ethnological Museum of Frankfurt, collecting across the Lamaholot region as well as on Alor and Pantar. They returned to Larantuka on 2 July 1929 and then drove westwards across Flores to Bajawa before exploring western Timor and Bali, from where they departed for Europe on 31 July 1929. They only toured Lembata at the end of their time in the Solor Archipelago in June 1929, completing their circuit of the island at Ilé Apé.

The smoking cone of Ilé Apé photographed by Ernst Vatter in June 1929

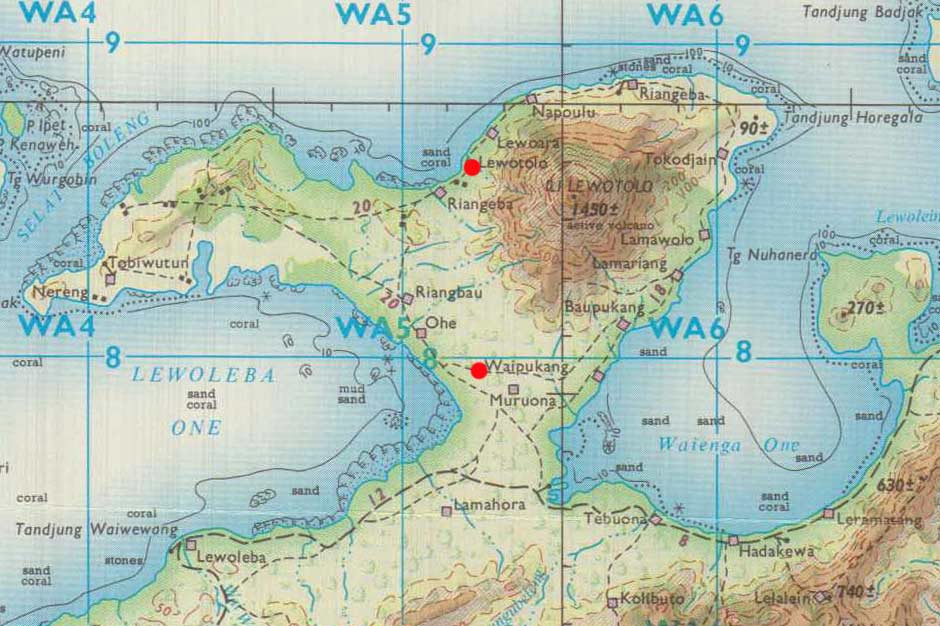

The location of Waipukang and Lewotolo (now Lewotolok)

Regrettably they only spent a few days at Waipukan in the southwest part of Ilé Apé, arriving just before the important bean festival, which was held in the ceremonial village of Lewohala at full moon in July for Atawatung (now Lamagute) and in August for Waipukang. Vatter left us with only a brief description of the region. In his opinion Lewotolo was the centre of local ikat weaving where the finest fabrics were produced. Some of these were traded to other parts of Lembata and to Adonara. The women of Ilé Apé all dressed in ‘self-woven’ ikatted sarongs, worn so that their breasts remained uncovered. They also knotted brightly dyed bast strips into their hair, while painting their faces with a rough sooty black stripe, which stretched across the forehead along the hairline (Vatter 1932, 216). A Catholic mission and school had only just opened in Lewoleba in 1926, and had clearly not yet had any impact on the way that the women of Ilé Apé dressed.

Women collecting water at the well in Lewotolo

Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Women from Lewotolo carrying water pots

Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1929

Textiles aside, Vatter was not impressed with the Lamaholot material culture of East Flores and the three Solor islands, which was restricted to a limited range of wooden carvings and bamboo objects that he judged poor in both artistic imagination and aesthetic value. While he also thought that the decoration of their textiles was equally simple, he considered in this case that simplicity provided an aesthetic advantage. On first comparison, he felt that they fell short of the dramatic textiles of Sumba with their dynamic zoomorphic motifs or the textiles of Savu and Rote with their more brilliant colouration. Yet in the long run they achieved far greater artistic impact. In his opinion one increasingly appreciated their reserved refinement that arose from their calmly structured layout, from their undemanding patterns and their muted colours (1932, 217).

Ernst Vatter collected just a handful of sarongs from Ilé Apé.

He acquired three two-panel wate ohin nulur piton, two woven in Lewotolo (catalogue numbers 69 and 70) and a third simply assigned to Ilé Apé (73). These are very similar to those that are still woven today, indicating an uninterrupted tradition that is at least a century long. He also found one wate senewaken in Atawatung (71), which is also typical of this pattern woven in that village.

An unusual three-panel wate senewaken, labelled a watek ohing [sic], collected from Atawatung by Ernst Vatter. Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

In addition he collected two unusual two-panel sarongs that seem to be linked to the hilltop hamlet of Atakoba (meaning people of the clouds) at Ledobelolong (now Lodobelolong), which is located in the highlands south of Dikesara and Waienga Bay – more than 35km overland from Ilé Apé. Although it is a non-weaving area today, many of its male inhabitants are married to women from Ilé Apé. It is possible that, like Hadekewa and Dikesara (formerly Lewolein), it received immigrants from Ilé Apé during the period of Dutch occupation. One of the sarongs (67) was acquired from a woman belonging to suku Lewolein, a widely distributed Lamaholot clan. It has the appearance of a wate hebaken with wide end sections containing a broad central band of ikat. Vatter described the second sarong (68) as an old piece, attributing it to either Ledobelolong or Ilé Apé. Each panel is almost completely covered with both wide and narrow bands of ikat apart from a plain blue terminal band with a white outer edge. This suggests that it was intended to be a ceremonial not a bridewealth sarong.

Both textiles are a mystery. They are most likely examples of a localised Ledobelolong style of weaving that was initially influenced by Ilé Apé, or perhaps less likely two unknown types of Ilé Apé sarong that have not been made for many decades.

In 1929 and 1931 the Dutch withdrew from Lembata, consolidating all of their Lamaholot territories back under the authority of the Rajas of Larantuka and Adonara (Symons cited by Barnes 1996, 30). Lembata was left in splendid isolation once more. Despite the construction of the north coast road, van den Windt complained in 1936 about the extraordinary difficulty of working on Lembata because of the mountainous terrain and lack of roads elsewhere on the island.

During the eight months they spent at Leuwayang, Kédang, in the far east of Lembata from October 1969 to June 1971, Ruth and Robert Barnes gained a fine distant view of towering Ilé Apé. During a later three-month stay in southern Lamalera in 1979 followed by a six-month stay in the second half of 1982, Ruth Barnes studied the ikat weaving culture of that village for her 1984 doctoral thesis. While there she paid a short visit to Ilé Apé (1984, 214). The Barneses visited Ilé Apé again in August 1985, spending time in the north coast village of Lewotolok.

In her thesis Ruth Barnes briefly discussed the ikat of Ilé Apé, noting that it ‘was extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get information about the cloth in general, and about specific patterns in particular’ (1984, 210). She was therefore unable to make an analysis of its textiles. She did note that Ilé Apé ikat sarongs were strikingly different from those of Lamalera and Ata Déi, being two-panel, with narrower main ikat bands and little trace of patolu influence. The local weaving was of a very high quality with precise ikat and subtle colours, but had a limited range of patterns. Indeed, Ilé Apé produced some of the finest Lamaholot textiles she had seen. Because of the above differences, Ruth Barnes judged that the Ilé Apé style of weaving was entirely indigenous to that area (1984, 215).

Return to Top

Women's Sarongs

On Ilé Apé a woman’s tubeskirt is normally referred to as a wate (pronounced ‘wat'er’) or less commonly fate. Today the weavers of Bungamuda, Napasabok and Jontona use the term wate, but say that older people often use the term fate, which was more common in the past. Speakers of Lamaholot frequently interchange the consonants [f] and [w]. As elsewhere in eastern Indonesia, there can also be differences in terminology from village to village. Thus in Lamagute they say watek and in Lewotolok they say watuk. As people on Lembata said to Marc Michels: ‘every village has its own language’ (Michels 2017, 11).

The panel of a sarong is called a nai in Lamaholot, meaning a piece of cloth. Two-panel sarongs are called wate nai rua and three-panel sarongs wate nai telo. However three-panel cloths are rare on Ilé Apé and are more commonly called tenépa.

Ruth Barnes was informed that three-panel sarongs were previously used in the Ilé Apé region of Lembata, but could not obtain a description of them (Barnes 1989, 100). She could only identify one possible candidate, held in the Basel collection (inventory number IIc 14732), but concluded that this could not be a tenépa because its central panel was decorated with a patola-like pattern similar to those found on three-panel sarongs at Lamalera and Ata Déi. In fact three-panel sarongs were woven in most villages of Ilé Apé in the past, and are still woven in some today.

On a sarong the mid seam is called the berait and the side seam is the kayun. A two-panel sarong can therefore be referred to as a wate berait to’u (one seam) and a three-panel sarong as a wate berait rua (two seams).

There are many different types of women’s sarong made on Ilé Apé. In increasing levels of status they are as follows:

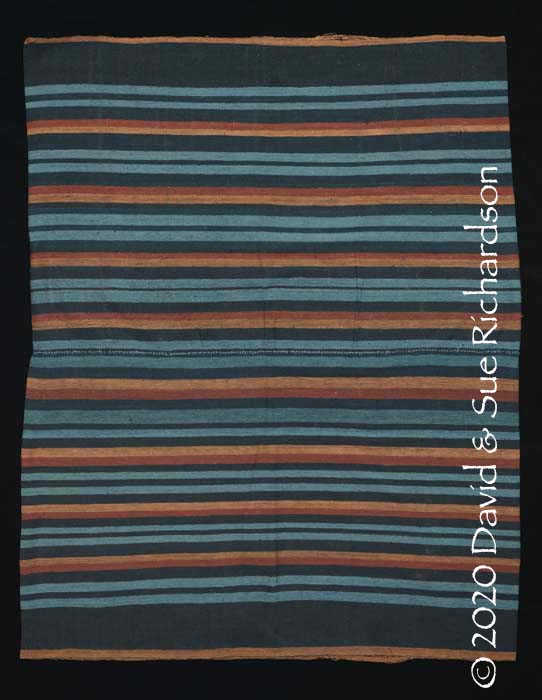

- wate mohle and wate kerokong are everyday two-panel warp-striped sarongs woven from hand-spun cotton and are devoid of ikat

- wate buraken are also everyday two-panel warp-striped sarongs woven from hand-spun cotton but are dominated by bands of white

- wate topon and wate krokon are two-panel sarongs with a plain black centre and chemically-dyed stripes that can be of hand-spun or commercial cotton. They are used for everyday wear, for an adat ceremony or for going to church

- wate botangen are modern two-panel sarongs, like the wate topon but they have more subdued colouring

- wate hebaken are ceremonial two-panel sarongs woven from hand-spun cotton that have a simple striped centre and end bands containing narrow bands of ikat. On the east coast of Ilé Apé they are known as a wate hebak

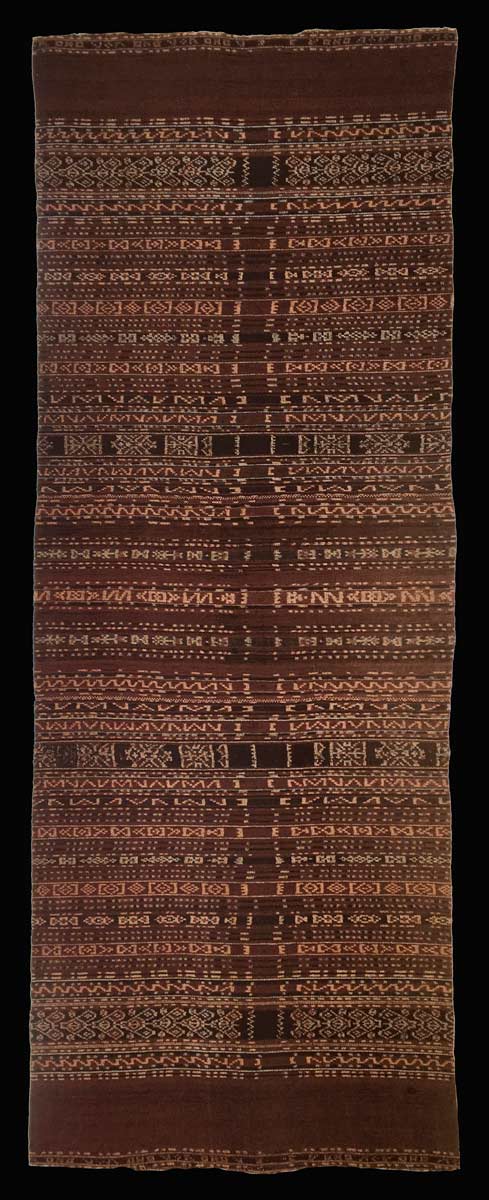

- wate ohin are ceremonial two-panel bridewealth sarongs woven from hand-spun cotton and decorated with alternating bands of ikat and plain brown. In southern Ilé Apé such sarongs are called wate bala ohi

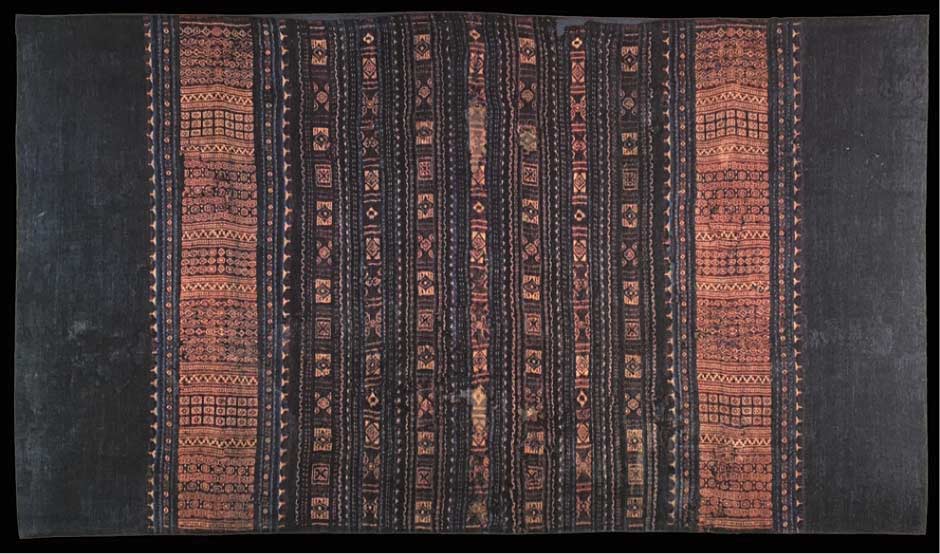

- wate senewaken are ceremonial two-panel sarongs woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton and are completely covered in narrow bands of ikat

- wate tenépa are very high-status three-panel sarongs woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton containing a distinctive centre panel, often decorated with a lattice.

Some of the higher-status sarongs are an essential part of the counter-prestation required to secure a marriage alliance. The composition of the counter-prestation can vary depending on the status of the marriage partners and the village.

The most important sarong included in the counter-prestation for bridewealth exchange is the wate ohin. This can be given alone, or in combination with other types of sarong. Generally in exchange for a single elephant tusk there are several types of counter-prestation:

✶ one wate ohin and five ivory bracelets

✶ one wate ohin and one wate hebaken

✶ one wate ohin and one Chinese ceramic plate

In Napasabok they claim the standard counter-prestation consists of one wate ohin, one wate hebaken, one wate topon and five ivory bracelets.

If the man’s clan cannot donate a tusk and provides gold (witi) and earrings (blaun) instead, then the counter-prestation does not justify a wate ohin. It then consists of one wate hebaken and one wate topon.

In Lamagute they claim the standard counter-prestation consists of one wate ohin, one wate hebaken, one wate krokon and five ivory bracelets. Sometimes even more textiles are included.

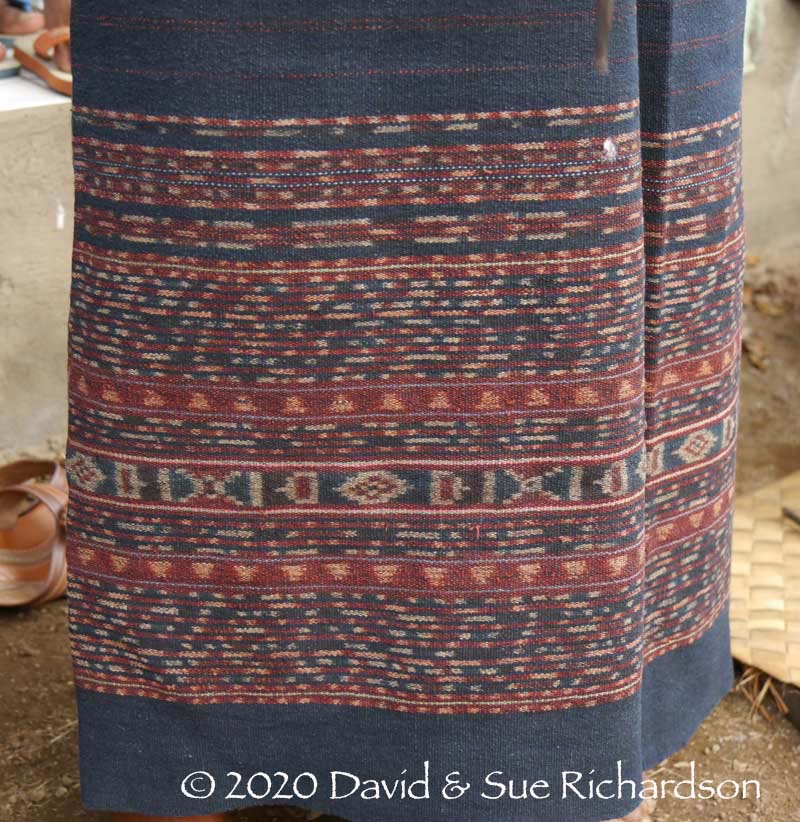

The women of Ilé Apé normally wear their sarongs tied at the waist and hanging down to their ankles. Because most sarongs are around 1.5 metres in length, this means the top part must be folded over. This can be folded over either on the inside or on the outside of the sarong.

The sisters Monika and Agnes Kihan at Napasabok wearing sarongs that are folded over inside

A woman wearing a wate ohin with the top folded over the outside

For more formal situations, a longer sarong can be folded above the breasts, making it unnecessary to wear a kebaya blouse.

An Ilé Apé woman dressed in an elegant wate ohin at a festival near Lewoleba

One must not assume that the women of Ilé Apé always wear locally made sarongs. For work in their gardens or around the home, many often wear more practical thin printed cotton sarongs purchased from the market in Lewoleba or from visiting traders.

Women returning from their gardens with firewood at Bungamuda

Return to Top

Wate Mohle or Wate Kerokong

Simple everyday sarongs are made from hand-spun cotton and are decorated with plain naturally dyed coloured bands. Such skirts are referred to as wate mohle along the north coast of Ilé Apé and wate kerokong in villages along the east coast of Ilé Apé such as Lamatokan (Tokojaeng), Lamawalo, Lamariang, Jontona (Baopukang), Todanara and Watodiri (Kimakama). The term wate kerokong is also used in southern villages such as Muruona.

A woman on Ilé Apé wearing a wate mohle as she drop spins and chews betel while carrying her produce home from her gardens

These simple, inexpensive textiles can be very beautiful with their contrasting bands of deeply dyed natural colours. Each one is unique.

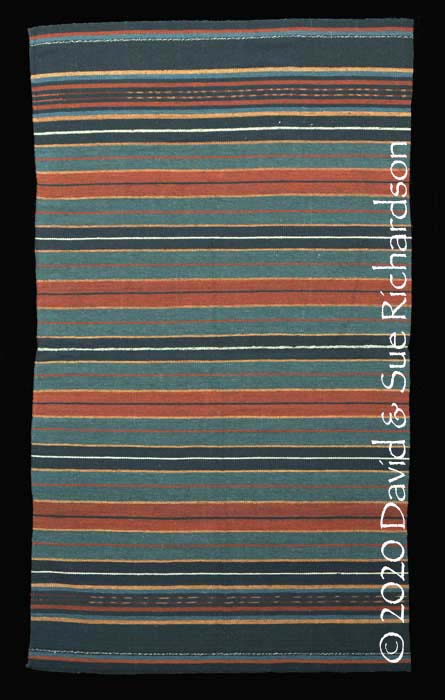

A wate mohle woven in Napasabok in about 2010

Richardson Collection

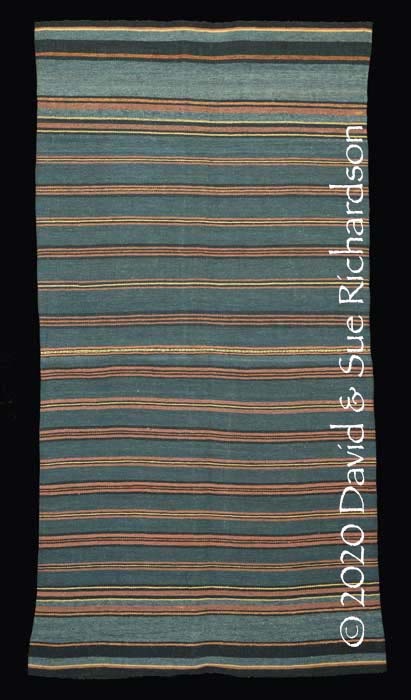

A wate mohle woven in Napasabok by Ursula

Richardson Collection

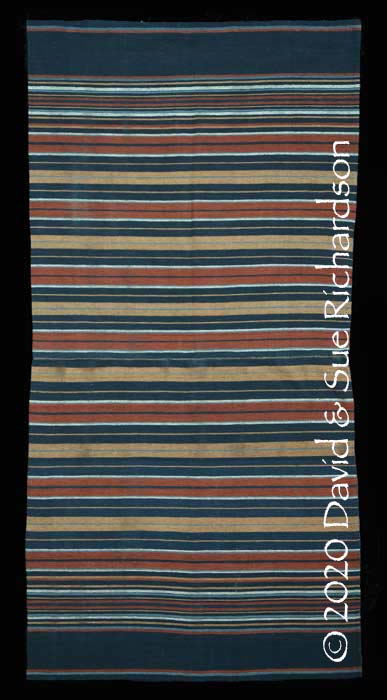

A wate mohle woven in Napasabok by Anastasia Bengang, aged around 75

Richardson Collection

A wate mohle woven in Napasabok

Richardson Collection

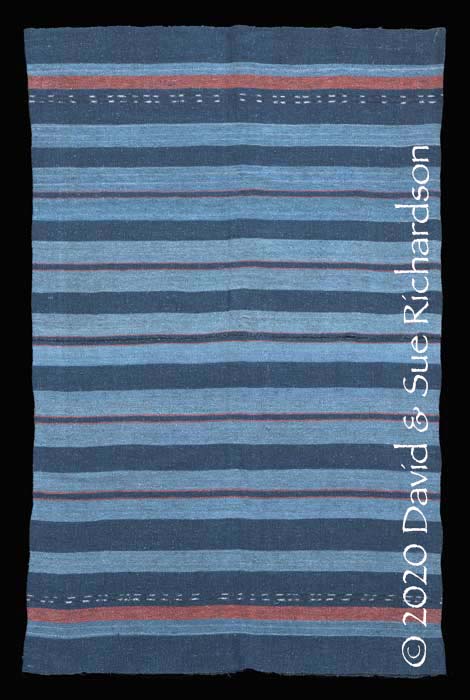

A wate mohle woven in Napasabok in 2018 by Esi Bengang, aged 57, who belongs to suku Laper Making. Richardson Collection

A wate kerokong at Jontona

Return to Top

Wate Buraken

Wate buraken are also simple everyday sarongs made from hand-spun cotton that are decorated with plain warp bands similar to wate mohle. However the majority of bands are white. The term buraken means blank or white in the local Lamaholot dialect. Such sarongs seem to be quite rare compared to wate mohle or wate kerokong.

A wate buraken, far left, and a wate mohle, far right

Return to Top

Wate Topon or Wate Krokon

Modern two-panel sarongs woven from commercial cotton that are decorated with a combination of stripes and bands, some of which are ikatted, and coloured with both chemical and natural dyes are called wate topon along the north and east coasts of Ilé Apé. However in a few villages such as Lamagute they use the term wate krokon.

The term topon (sometimes pronounced ‘topang’) seems to refer to the narrow stripes at the ends of the panels. Such skirts can be worn to attend an adat ceremony or for attendance at church. The wate topon is not used for bridewealth although there is one exception – see Women’s Sarongs above.

There are two types: the topon tukan miten, which has a black centre, and the topon tukan senega, which has stripes in the middle. Tukan means middle, miten means black and senega means mixed.

Left and right: two wate topon tukan miten. Centre: a wate topon tukan senega.

Two mothers wearing wate topon tukan senega at Napasabok

Similar skirts in which the colours are much more subdued are called wate botangen.

These modern everyday sarongs are occasionally called watek watan, watan meaning beach. This is because seaborne merchants who supply the commercial yarn used to land on the beach to sell their wares.

Wate topon or krokon for sale at Lewoleba market

Women attending a meeting in Jontona to discuss a marriage alliance

They are mostly dressed in wate topon

Although today most wate topon are made from commercial cotton, mostly pre-dyed, some are mixed with naturally dyed hand-spun yarns and can look very similar to the wate hebaken. Even so they are still referred to as wate topon. The example below was woven with hand-spun cotton that had been naturally dyed (including the bands of ikat) but was embellished with numerous brightly coloured stripes of commercial pre-dyed yarn.

Mala Lado Purab displaying a hand-spun wate topon at Bungamuda

Return to Top

Wate Kebo Lolon

The wate kebo lolon is a two-panel sarong woven with naturally dyed hand-spun cotton. It is decorated with end sections containing a compact cluster of narrow ikat bands and a central section filled with narrow alternating bands of ikat and plain indigo. It resembles the wate hebaken, but with more dominant central banding. However unlike the wate hebaken the wate kebo lolon is a lower-status sarong that is for everyday attire, for adat ceremonies or for going to church. It cannot be used for bridewealth exchange.

The term kebo lolon means palm leaf (kebo means palm and lolon means leaf) and refers to one of the patterns in the narrow bands of ikat.

A wate kebo lolon belonging to a woman from Bungamuda

The following wate kebo lolon was made in 2015 by the talented master ikat binder and weaver, Mama Agnes Dai from Napasabok. She is one of three unmarried sisters who belong to suku Lopot Making, one of the seven clans that belong to the higher status Beloloken tribe.

The wate kebo lolon made by Mama Agnes DaiRichardson Collection

Mama Agnes Dai wearing a very similar wate kebo lolon at Napasabok

Return to Top

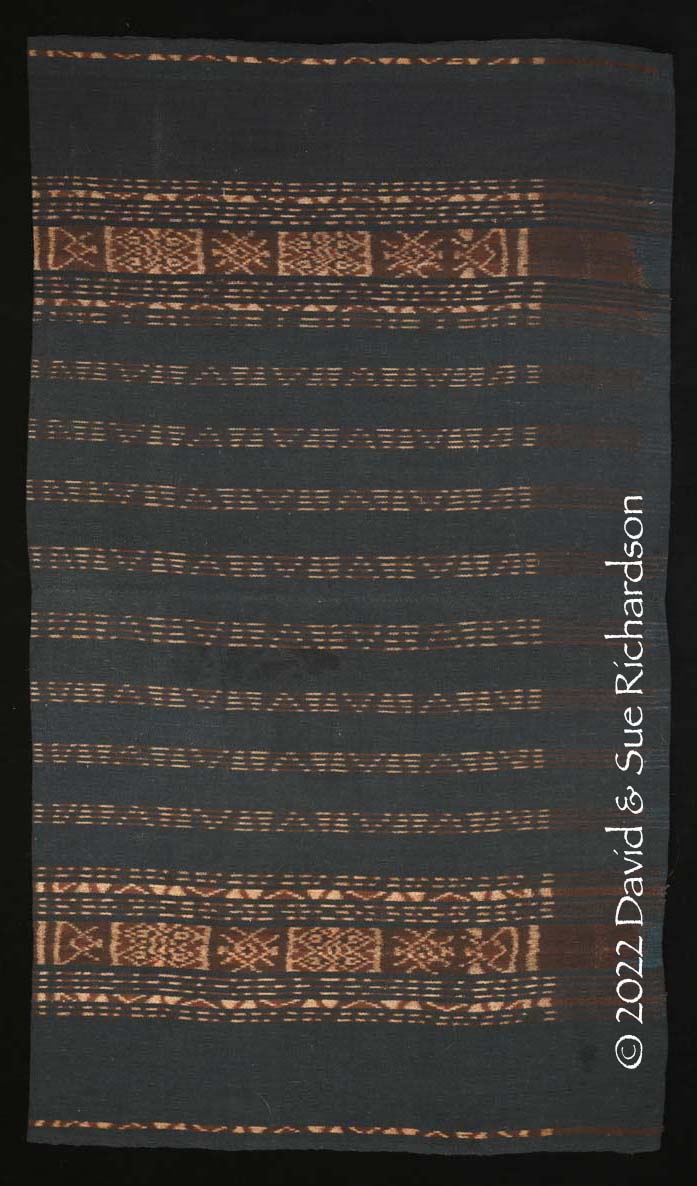

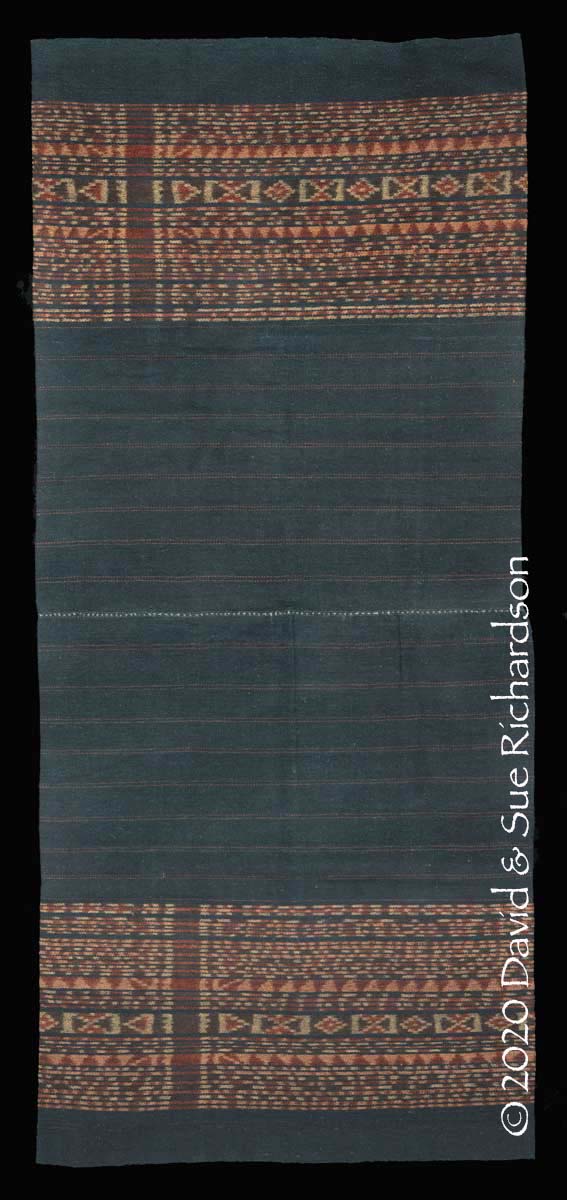

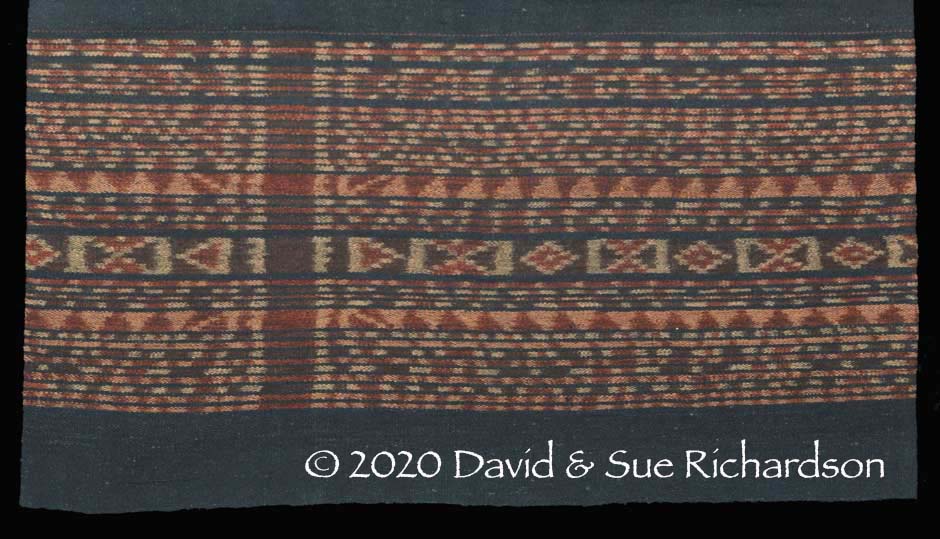

Wate Hebaken or Wate Hebak

The wate hebaken or hebak is a naturally dyed adat sarong woven from hand-spun cotton with a plain striped centre and narrow striped end sections. It has a lower status than the predominantly morinda-dyed wate ohin. The term hebaken (pronounced ‘hebak'n’) is used along the north coast of Ilé Apé and the term hebak (pronounced with a silent k) along the east coast and in the south of Ilé Apé.

Two women dressed in wate hebaken in Lewoleba

High-quality binding on a wate hebaken at Lamagute

The term hebak is also used by weavers in villages along the south coast of Waienga Bay, such as Hadakewa and Lerahingga, and in Dikesara (formerly Lewolein) on the east coast. These communities migrated from Ilé Apé during the time of the Dutch, following a local war.

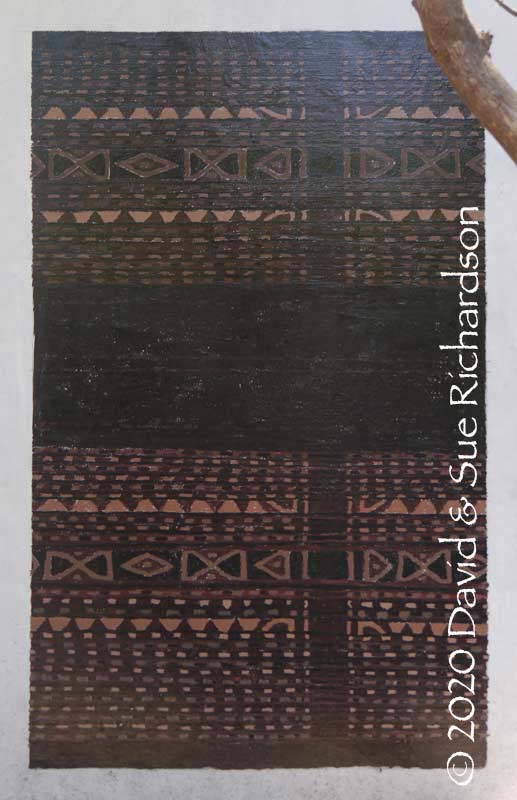

A painting of a wate hebaken on a wall at Lamawara

It is essential that the hebaken is entirely made from hand-spun cotton. If a skirt decorated in the hebaken style is woven entirely or just partially with commercial yarn it is considered an everyday sarong and is called a wate topon and has no adat value. In Napasabok and Lamagute wate hebaken woven with a mixture of natural and chemical yarns are called wate hebaken krokan.

Mama Selma weaving a modern watek hebaken krokan at Napasabok

There are two types of wate hebaken – the wate hebaken miten with a black centre and the wate hebaken méan with a red centre. The latter are quite rare.

A wate hebaken miten woven in 1996 by Belinda Bengang, now aged 56, in Napasabok

Richardson Collection

A finely ikatted wate hebaken

Private collection, Lewoleba

A wate hebak at Jontona

The rare wate hebaken méan

An untypical wate hebak méan at Dikesara

The term hebaken refers to the cluster of narrow stripes and bands at the top and bottom of the wate.

Detail of the hebaken end section

The central band of ikat in the hebaken is called the ina or mother. The narrow stripes on either side of it are called the liko ina meaning protect mother.

The two main motifs in the ina are:

- the diamond-shaped muda lolon or mudaten, meaning orange leaf (muda = orange, lolon = leaf) and

- the cross- or bow tie-shaped rie hangen, the term used to describe the forked-beam in a house.

The two flanking rows of small interlocking brown and beige triangles are called the belikung or blikun, also meaning the protectors. The triangles themselves are called kebelepak or kebele pak (pronounced with a silent k) meaning ‘folded coconut leaf’, despite the fact that a coconut is a kelapa and a leaf is a lepa or lepan.

The narrow stripes at the bottom and top of the cluster are called topon or hebak topon.

Return to Top

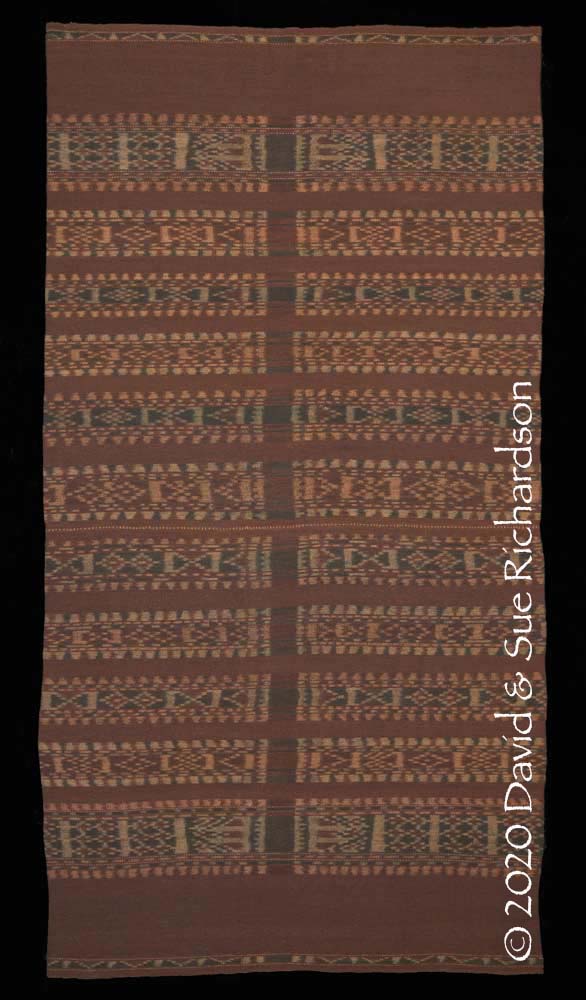

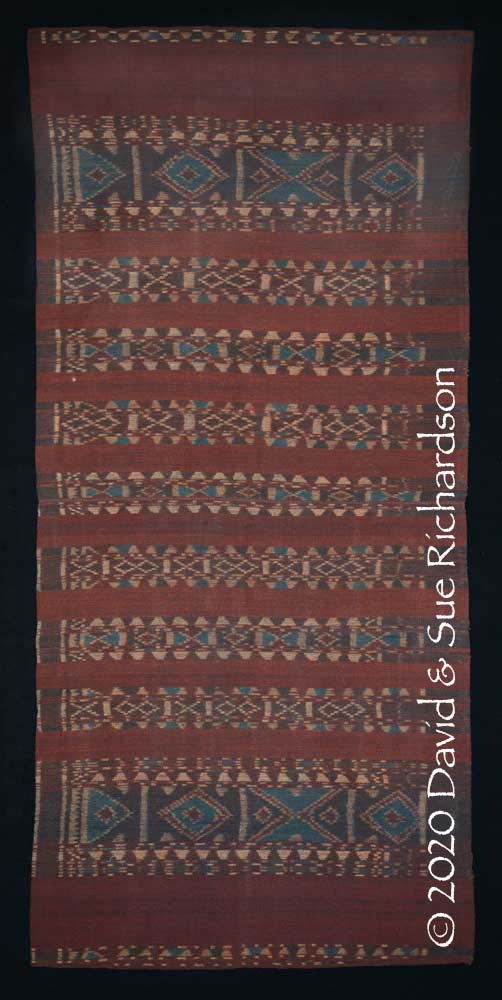

Wate Ohin or Wate Bala Ohi

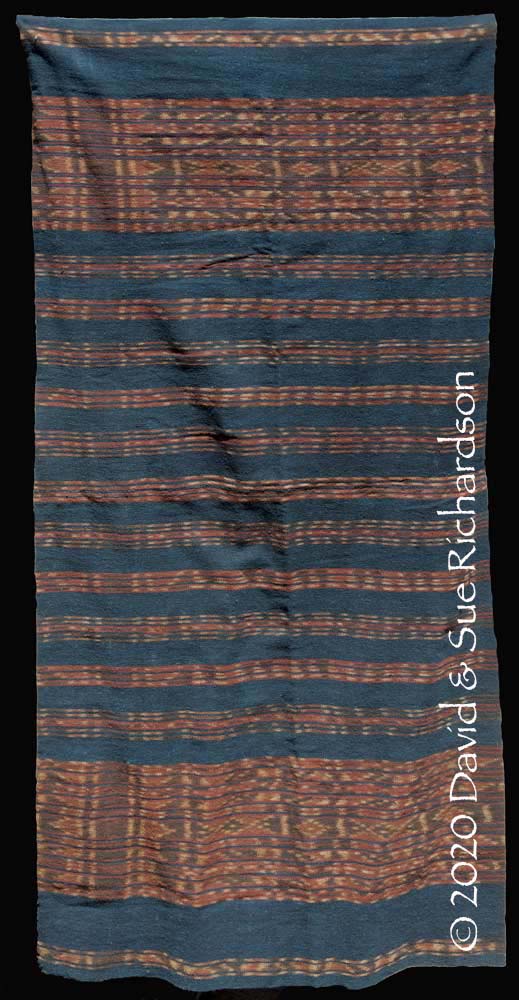

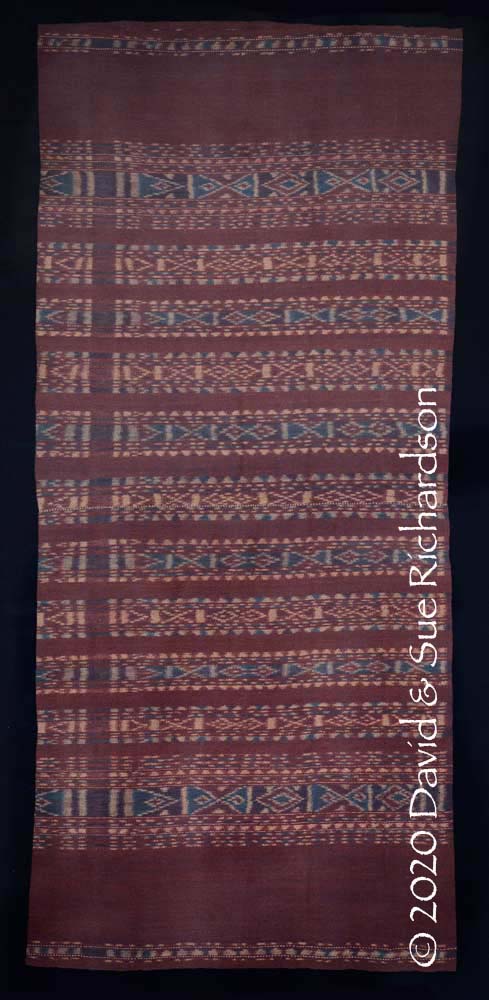

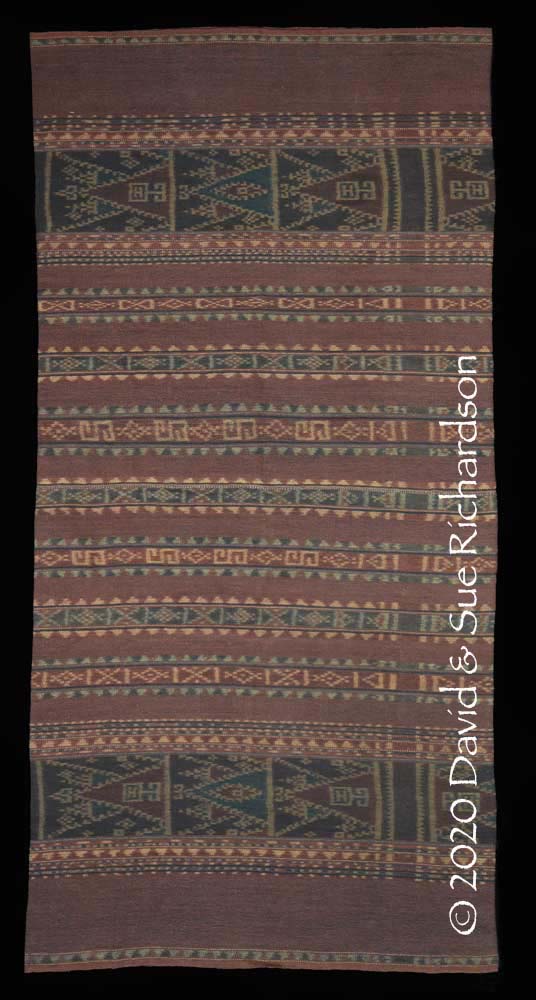

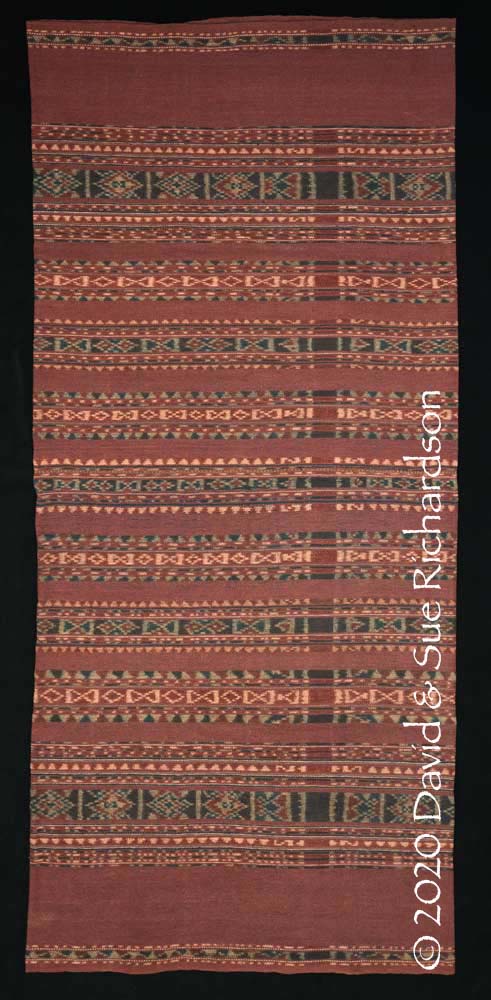

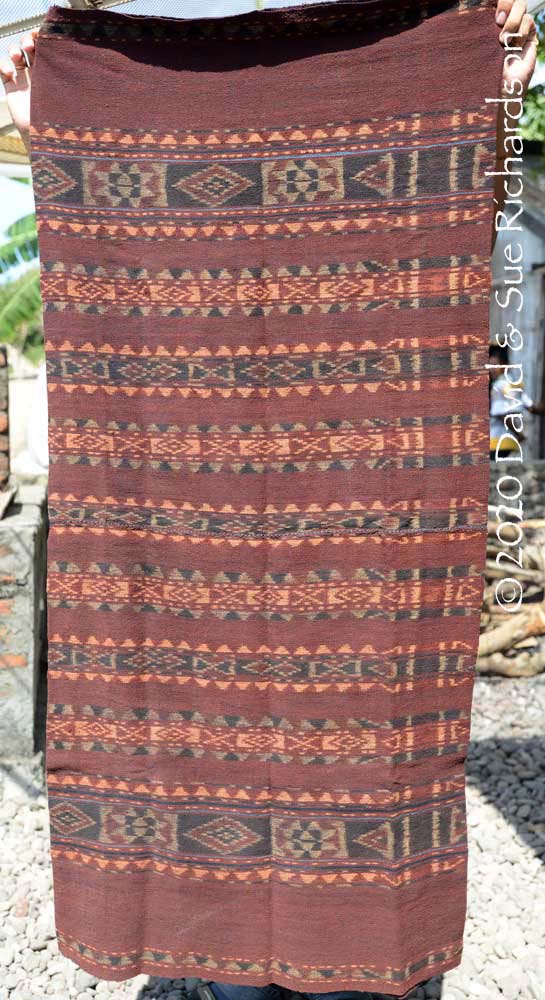

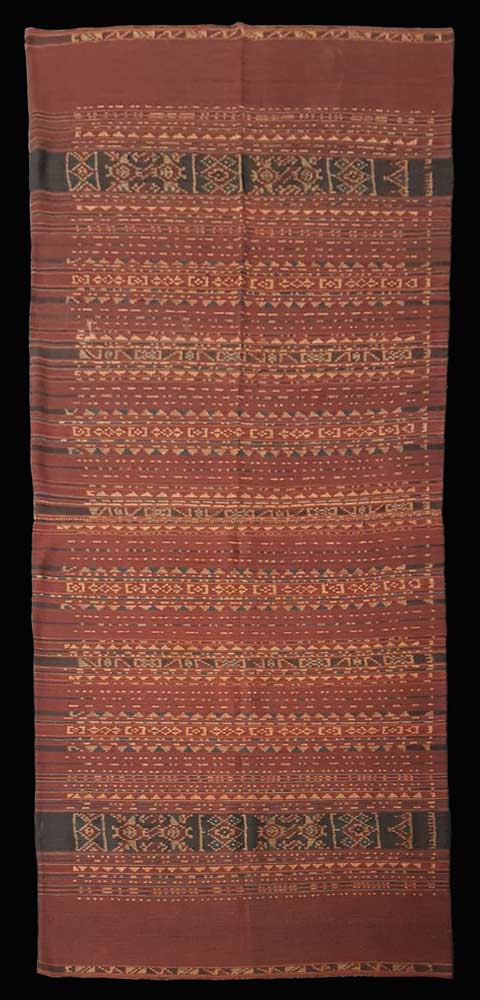

The wate ohin is the most important ceremonial two-panel bridewealth sarong woven on Ilé Apé. It is made from hand-spun cotton and decorated with alternating bands of ikat and plain morinda brown. Today similar-looking sarongs are woven using commercial yarn but these do not have the status of a wate ohin – they are classified as wate topon.

A wate ohin from a private collection in Lewoleba

A wate ohin in Jontona

The example below was woven 40 years ago by Helena Gehin Makin in Riangbao, located on the southwest side of Ilé Api. Riangbao has since been renamed Batuntawa. She is from suku Nilan and is now 65 years old and living in Todanara. She wove it when she was 20 years old with the intention of wearing it for her future wedding. It was not until she was 25 that she married a local farmer and moved to Todanara. Suku Nilan provided a second watek ohin for the counter-prestation that was given to suku Makin, her husband’s clan.

A wate ohin nulur hiwa woven by Helena Gehin Makin in Batuntawa

Richardson Collection

In north Ilé Api Lamaholot, ohin means agreement and in this context refers to the marriage agreement, including the negotiated bridewealth and counter-prestation. Weavers often simply say that ohin means bridewealth, in other words the wate ohin is literally a bridewealth sarong.

While the term wate ohin is used along the north and east coasts of Ilé Apé, in southern Ilé Apé in villages like Muruona, such sarongs are called wate bala ohi – bala meaning tusk and ohi still meaning agreement in their local dialect.

The people of Kédang call the Ilé Apé wate ohin a wéla wato-ohi, but do not understand the meaning of wato-ohi (Ruth Barnes 1989, 108).

Note that in the north coast dialect, the very similar word ohine refers to the Ilé Api district, while ohi means a ban, prohibition or the cancellation of an agreement (Lebuan 2020).

Generically these sarongs are classified as wate méan or red sarongs. This decription not only applies to the colour of the sarong, but also to its status. In Lamaholot society red is seen as auspicious and possessing spiritual power. According to Ruth Barnes, although the term méan is always directly translated as ‘red’, the word seems to signify extraordinary powers or wealth (1989b, 50). Consequently the majority of Lamaholot bridewealth cloths are predominantly dyed a morinda reddish-brown.

A very fine wate ohin at Napasabok

Wate ohin are classified by the number of ikat bands (nulur or sometimes nuluren) in the central section of the sarong that are flanked by the two outermost bands (which are not included in the number). Today there are normally either seven or nine bands of ikat. A sarong with seven bands is called a nulur piton (band seven), while one with nine bands is called a nulur hiwa (band nine). In the past they were often woven with eleven bands and were called nulur pulok to’u.

However in Napasabok they call the inner ikat bands matan rather than nulur.

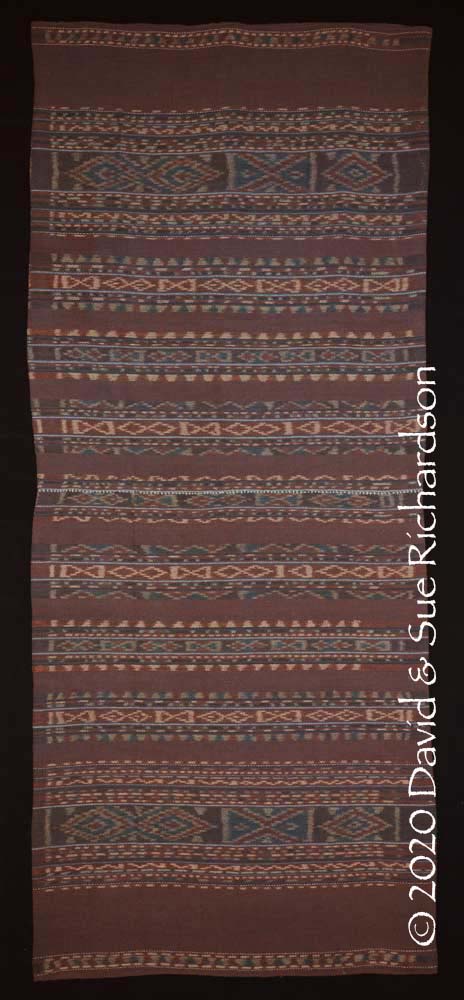

A wate ohin nulur piton. No provenance

Richardson Collecion

A wate ohin nulur hiwa. No provenance

Richardson Collecion

Because the number of nulur ikat bands is almost (but not always) odd, this means that the two panels have a different width, one panel being woven with one more nulur than the other. Each are woven separately on continuous circular warps.

One panel of a wate ohin with four nulur bands at Bungamuda

The wate ohin below was woven by Elisabet Sabon in Napasabok before the birth of her daughter, Moni Lema Holo, who is now aged 60:

A wate ohin matan pito woven over 60 years ago by Elisabet Sabon in Napasabok Richardson Collection

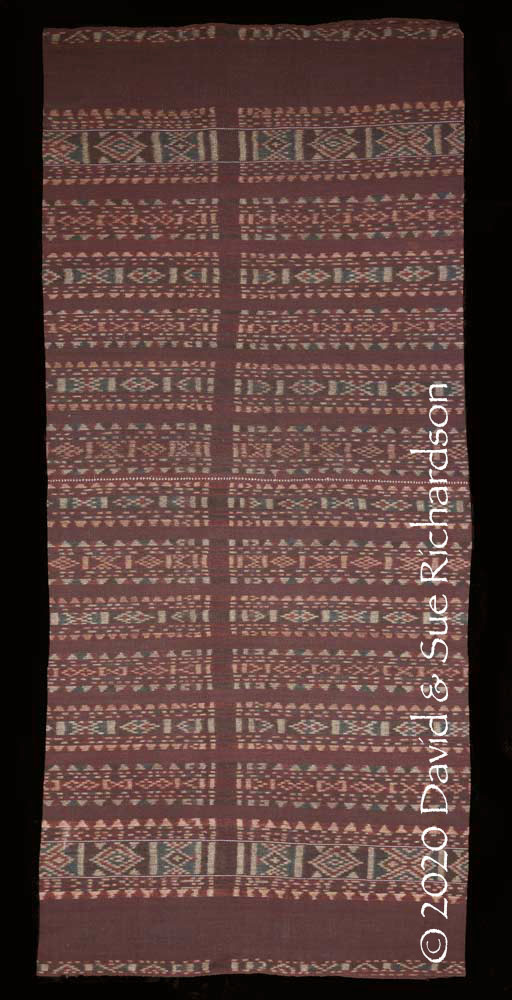

The next eleven-banded wate ohin nulur pulok to’u was woven earlier, about 75 years ago, by Nene Peni from Lewolein (since renamed Dikesara) who belonged to the important house of Lango Belun. She died in 1972. The village of Lewolein was founded by people who migrated from Ilé Apé during the period of Dutch occupation.

A wate ohin nulur pulo woven about 75 years ago by Nene Peni in Dikesara

Richardson Collecion

Nene Peni also wove a ten-banded wate ohin nulur pulok to’u at around the same time. Despite the fact the number of nulur is even, the two panels still have different widths, there being six nulur on one and four on the other.

A wate ohin nulur pulok to’u also woven about 75 years ago by Nene Peni in Dikesara

Richardson Collecion

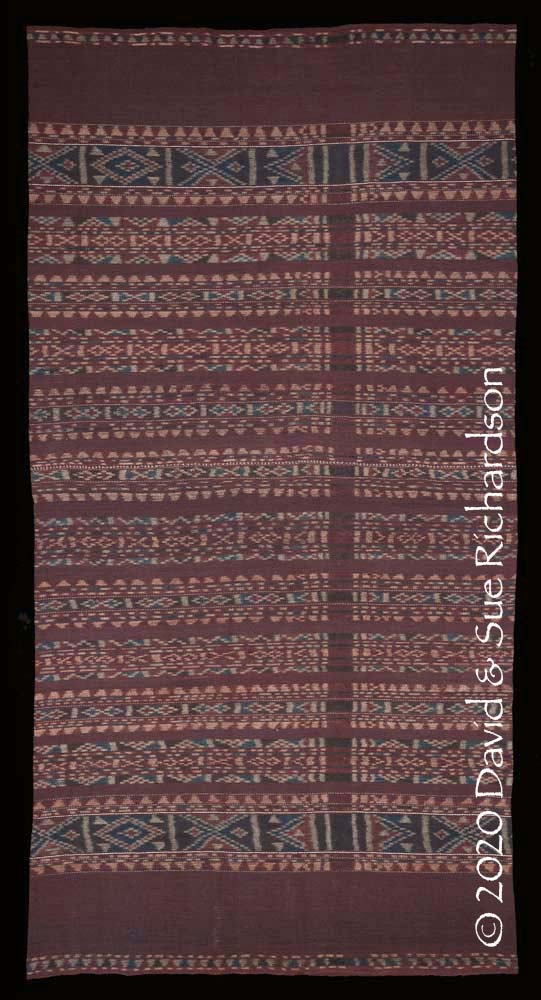

Another even older example woven in Napasabok about 95 years ago has a very different design with a much wider ina decorated with a more complex motif. It was acquired from the weaver’s 65-year-old granddaughter. Sadly the weaver died in 1954 at a ripe-old age when her granddaughter was only 5 years old.

A wate ohin matan piton woven about 95 years ago by Ina Kepua in Napasabok

Richardson Collection

The oldest wate ohin in our collection was woven in about 1902 by Tuto Balawala from suku Balawala in Napasabok. She wove it to be used for the counter-prestation for her future marriage. She chose a husband who was from suku Manuk and was married two or three years before she had her first child, a son born in 1906 who was followed by a second son in 1912. She gave birth to five children in total – four sons and one daughter.

A wate ohin matan piton woven by Tuto Balawala in about 1902

Richardson Collection

Her second son married Rosa Djari Hurek from suku Hurek, who died in 1999 when she was over 90 years old. We acquired the sarong from their son, Patrisius Gawi Manuk from suku Manuk, was is the current kepala desa of Napasabok.

We have already mentioned the three similar wate ohin collected by Vatter in 1929. The provenance of the sarong woven by Tuto Balawala is evidence that the tradition of making such sarongs goes back at least to the late nineteenth century.

Because wate ohin are considered to have a similar value to an heirloom elephant’s tusk, they are highly valued.

Return to Top

Wate Ohin Motifs

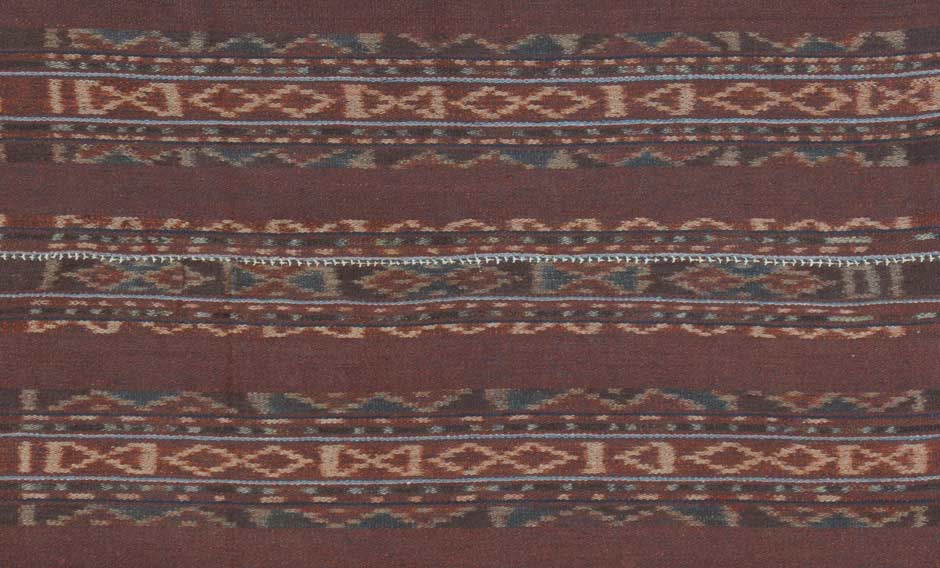

The two main ikat bands in the wate ohin are called the ina, the mother, and are protected by the likon ina, although some weavers call this the blikon ina. However in some villages such as Napasabok, they call the main band béleken rather than ina. Béle means large. Generally this is relatively narrow by eastern Indonesian standards, being composed of no more than fifteen ikat skeins. However there are exceptions as seen above.

The plain reddish-brown terminal band is called the hebaken although some weavers simply call it the méan, in other words the red. The narrow end band is the semeringan.

The rows of simple geometric motifs used in the internal bands are normally composed of diamonds and crosses. In local terminology a single diamond or a double diamond is called a muda lolon, meaning an orange leaf, sometimes shortened to mudaten. A diamond is also sometimes referred to by its Dutch description – a ruit. The rectangular motif enclosing a cross, which looks like a bow tie, is called a rie hangen, the term used to describe the forked-beam in a house:

The rows of flanking triangles are called kebelepak or kebele pak (pronounced with a silent k) meaning folded coconut leaf. The angular s-shaped motif is the aran leman:

The chevrons with alternating up and down orientations are called lakadowak:

The somewhat similar outer rows of zigzag or M-shaped motifs are called lekedowaten:

A rare upright hashtag-shaped motif, not illustrated but similar to the octothorpe symbol #, is called mekangen. Another uncommon motif based on a rectangle with E-shaped ends is called narun bunga. It is very similar to a common motif found on Tanimbar Island in southern Maluku.

Two narun bunga motifs in one of the nulur inner bands

Two larger motifs appear in the ina or béleken, the main ikat band, time and time again. The large diamond or double-diamond is again called muda lolon or mudaten, meaning orange leaf. A few use ruit, the Dutch word for diamond. The adjacent rectangular cross-shaped motif that looks like a chevron with an inverted chevron balanced above it is called the bélawaten (sounds like bélawate), which represents the niddy-noddy yarn winder known in Napasabok as a belawai (the same as on Ata Déi) and in Lamagute as a belawa.

Above and below: muda lolon or mudaten and bélawaten

Ruth Barnes (1984, 212) believed that the large motifs found in Ilé Apé cloths had less variety than those found elsewhere on Lembata, being mainly limited to rhombs and triangles. In reality there is considerably more diversity in local motifs than this comment would suggest, although the less common motifs only appear in limited numbers.

Only a few of the more complex motifs seem to be given names by today’s weavers. Thus the eight-pointed star motif is called maliken, while the four-pronged diamond-shaped bloom from the hardwood tree (not illustrated) is the kukunpahun.

Above and below: the maliken eight-pointed star

The six-armed diamond enclosing a sideways letter [s] shown below is called the aran leman, or hardwood chopping board, aran meaning wooden board or plank and leman meaning hard. However many motifs are simply called béleken, the term that normally refers to the main ikat band but in this context means big picture.

Two aran leman motifs flanking a bélawaten motif

Some are qualified further by adding the number of ikat bundles required to make the ikat band containing that motif. Thus a béleken pulok telo is a big picture composed of 13 bundles (pulok = teens, telo = 3) of ikatted warps.

A very complex and wide motif, simply described as a béleken

It is sometimes said that the textiles of Ilé Apé do not incorporate the moko manta ray motifs that are associated with those of Lamalera and Ata Déi. This is not correct, as the following examples demonstrate:

Pairs of manta rays and an eight-pointed star in a wate ohin

A relatively rare wate ohin decorated with pairs of manta motifs

Another marine motif that occasionally appears in wate ohin is the mola mola or huge ocean sunfish, which is more frequently found in the petak haren of Ata Déi in combination with the manta ray:

A wate ohin with the mola mola motif.

It is likely that a more comprehensive survey would uncover a multitude of additional motifs, as the final example shows:

Unusual complex motifs on a wate ohin at Jontona

Return to Top

The Revot on Ilé Apé

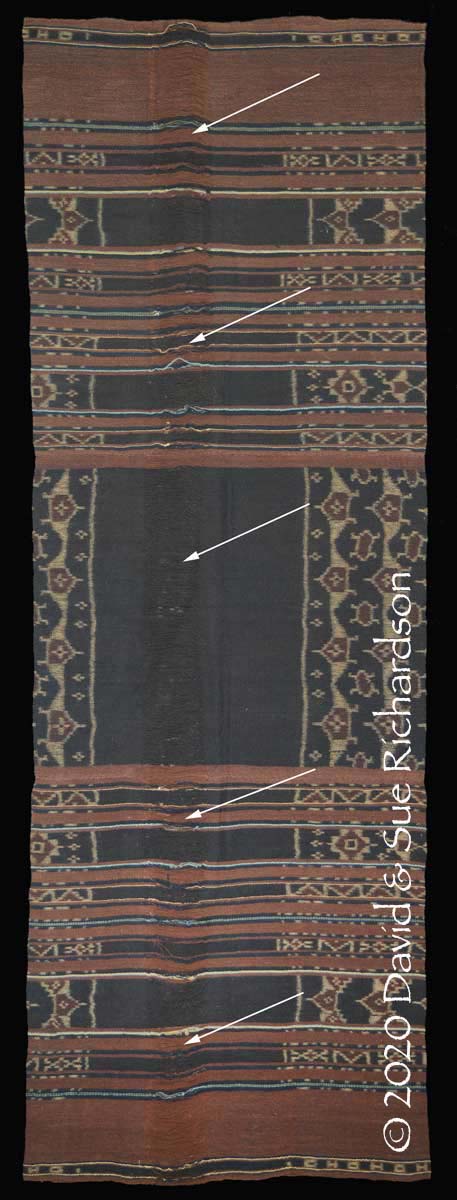

When a textile is woven on a back-tension or any other loom on a continuous circular warp, there comes a time when the weaving is almost complete but the remaining unwoven warps have become too short to be able to continue passing the shuttle through the open shed. The weaver normally stops at this point, removes the cloth from the loom and cuts through the unwoven warps, leaving a rectangular piece of cloth with loose warps at each end. This can then be fashioned into a tubeskirt, a fringed blanket or some other article as desired.

Many Lamaholot weavers refer to this section of unwoven warps as the rata or the revot, although in eastern Mingar they sometimes say serewot and on Ata Déi they say wunuren. In Lamaholot rata, or in some dialects ratan, means hair (Michels 2017, 46; Nagaya 2011, 60; Nishyama and Kelen 2007, 13).

If the cloth is to be made into a tubeskirt to be worn, the rata or revot in each panel is cut, the two panels are joined selvedge to selvedge and the cut ends are joined with a rolled seam. However in many Lamaholot regions on Lembata, including Lamalera, eastern Mingar and Ata Déi, and also in parts of East Flores, it was – and in some instances still is – essential that a bridewealth sarong was/is made from two lengths of continuous cloth in which the rata or revot remained/remains intact. Such a skirt can be used for a counter-prestation not just once, but repeatedly. However once those warps are severed it can no longer be used for that purpose ever again.

The wunuren (revot) on the three aligned panels of a petak harén bridewealth sarong from Watuwawer on Ata Déi. Richardson Collection.

Clearly for some of these communities, the rata or revot has auspicious or semi-sacred properties. In one part of East Flores the rata hairs were said to stand for the threads of kinship and descent (Ruth Barnes 1989b, 51). Ruth Barnes later described the uncut warp as the ‘thread of life’ (Barnes 1994, 21). In her opinion, dealers or collectors who cut these warps made the cloth literally lifeless, transforming it from a ritual cultural heirloom into a dead object of art.

One possible explanation of why the uncut warps might possess such ritual value has been proposed by Geneviève Duggan, who has investigated the link between the historical weaving of Sulawesi and that of Savu Island (2015).

In the past, weavers on Bentenan Island in North Sulawesi produced very long, high-quality ceremonial seamless tubular sarongs known as pinatikan that were woven on back-tension looms using a continuous warp. A specific feature of these sarongs was that the entire warp was interlaced with weft. As the weaving progressed, the length of the unwoven warps decreased to a point where the shed became too small to pass the shuttle through. The final section of cloth was therefore laboriously woven using a needle rather than a shuttle – a technique that was maintained until the end of the nineteenth century (Boland 1977, 1). Similar textiles have been found around Poso in Central Sulawesi, the only complication being that Kruyt recorded that Porso was a non-weaving area, so these must have been made elsewhere (Khan Majlis 1984, 120) An example of such a sarong from Poso collected by the late Mary Kahlenberg has been carbon 14 dated to the fifteenth or sixteenth century (Barnes and Kahlenberg 2010, 254-255).

Sarong collected from the Poso region of Central Sulawesi, carbon dated to the 15th or 16th century. Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection

Duggan discovered that on Savu Island there had been a tradition of producing a kenoto bridewealth bag using a similar weaving technique, only remembered by a few elderly women. The body of the bag and the handle were woven together with a complete circular warp, the centre of the handle being completed using a bamboo needle. The term kenoto refers both to the bag and to the system of customary marriage on Savu.

A new kenoto bridewealth bag on Savu Island

The kenoto was woven by the mother of the groom or by another female member of his family. It contained the ingredients for a betel nut chew, and possibly an item of gold or silver depending on the bride’s lineage or wini. The bag was then hung on the male pillar of the young woman's parents' house as a symbol of the marriage and remained there for years, if not decades.

Although Savunese women’s skirts called èi are also woven on a circular warp, in this case the unwoven warps are cut away so that the severed edges can be joined with a seam. Even so the discarded unwoven warp threads are still considered powerful and sacred and are used in rituals (Duggan 2015, 66). The importance given to these yarns might suggest that finishing the final unwoven section of continuous warps is the remnant of an ancient technique that was once more widespread.

More recently Geneviève Duggan has looked again at the historical and textile links between Sulawesi and the Lesser Sunda Islands (Duggan 2015, 53-83). We already know that Makassarese merchants traded widely throughput eastern Indonesia in the past. However a map belonging to the Sultanate of Gowa illustrates that prior to 1660 – and therefore probably also before the arrival of the Europeans – the sovereignty of Makassar extended widely, even as far south as north Australia (Ganter 2005). Meanwhile local narratives suggest a pre-Portuguese migration from Luwu and Makassar to Timor via Abi and Tunbesi (Tukang Besi?) in South Sulawesi (Spillett 1999, 29 and 31).

Duggan’s observations echo an earlier study of ikat techniques and processes by Alfred Bühler, which concluded that seamless tubular ikat textiles are the remnant of an ancient technique that may have originated in Minahasa, northern Sulawesi (1943, 47-168).

Further evidence of a link between Sulawesi and eastern Indonesia has been provided by the Australian linguist Geoffrey Hull, who has proposed a late migration of Austronesian immigrants from the Tukang Besi Islands of south-eastern Sulawesi to Kisar and East Timor, giving rise to the Meher and Kawamina family of languages. He estimates that this occurred around the eleventh century CE (Hull 1998, 150-151).

The main concern with Duggan’s hypothesis is that the Bali Aga of Tenganan Pegringsingan on Bali also use ritual textiles with uncut continuous warps. For them such textiles are considered sacred. For example, simple circular cotton sashes called wangsul (meaning ‘to return’) are used as offerings in rites of passage and might be part of a tradition that can be traced back to the Majapahit era (Ramseyer 1991, 62). In a sacred ritual performed on Lombok, a priest cuts and opens the warps of a similar cotton cloth, thereby releasing the energy stored in its continuous warps. On Bali only unused textiles with an intact circular warp, including geringsing, can be presented to deities and ancestors as rantasan textile offerings. Once the warps have been cut, textiles can only be offered to, or worn by, a human (Ramseyer 1984, 221).

These rituals and beliefs are clearly Hindu and do not originate from Sulawesi. Either the concept of ritual value associated with textiles with uncut continuous warps emerged independently in different societies at different times or else it is a common tradition that emerged during the evolution of back-tension weaving.

Returning to our main subject – the textiles on Ilé Apé – there is surprisingly no prohibition applied in this region of Lembata to the severing of the unwoven warps in a bridewealth sarong. In many villages like Napasabok, weavers say that the unwoven warps MUST be cut, whereas in others, such as Jontona, they say that it does not matter whether the cloth is used straight off the loom with an uncut rata or revot or is cut and sewn up with a side seam. Ruth Barnes had already noted this feature during her sojourn in Lamalera (1984, 213).

This idiosyncrasy again points towards the different ethnic origin of the people of Ilé Apé from the inhabitants of Lamalera, Ata Déi and eastern Mingar.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Albo, Franscico, 1874. Extracts from a Derrotero or Log-Book of the Voyage of Fernando de Magellanes in Search of the Strait, from the Cape of St. Augustin, Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Anon, 1956. Fundaçâo das Primeiras Cristanades nas Ilhas de Solor e Timor, pp. 475-

Documentação para a história das missões do padroado português do Oriente: 1568-1579, vol. 4, Basílio de Sá, Artur (ed.), Agência Geral do Ultramar, Divisão de Publicações e Biblioteca, Lisbon.

Ansar, Majid, 2018. Belis gading gajah tradisi perkawinan masyarakat Lamaholot di Ile Ape Kabupaten Lembata Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur, S1 Thesis, University of Makassar.

Ataladjar, Thomas B., 2015. Pai Hone Tala Ia, Pai Wane Tele Pia, Lame Lusi Lako dari Tanah Nubanara Menuju Tanah Misi, Koker, Jakarta.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata, 2018. Kabupaten Lembata Dalam Angka, Lewoleba.

Barbosa, Duarte, 1866. A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the beginning of the Sixteenth Century, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Barnes, R. H., 1977. Alliance and Categories in Wailolong, East Flores, Sociologus, New Series, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 133-157.

Barnes, R. H., 1979. Lord, Ancestor and Afine: An Austronesian Relationship Name, NUSA, vol. 7, pp. 19-34,

Barnes, Robert. 1982. The Majapahit dependency Galiyao, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 138, pp. 407–412, Leiden.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989a. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989b. 'The Bridewealth Cloth of Lamalera, Lembata', in To Speak With Cloth: Studies in Indonesian Textiles, Gittinger, Mattiebelle, (ed.), University of California, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 1991a. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 2, pp.95–112.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Fragile Traditions: Indonesian Art in Jeopardy, University of Hawaii Press.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010a. Woman’s Tubular Skirt: Porso Toraja Region, Sulawesi, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 254-255, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010b. Woman’s Bridewealth Tubular Skirt, watek ohing Ili Api, Lembata, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 346-347, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Beckering, J. D. H., 1911. Beschrijving der eilanden Adonara en Lomblem, behoorende tot de Solor-Groep, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2e Série, vol. 28, pp. 167-202.

Bolland, Rita, 1977. Weaving the Pinatikan, a warp-patterned Kain Bentenan from North Celebes , Studies in textile history : in memory of Harold B. Burnham, pp. 1-17, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Donselaar, W. M., 1882. De Christelijke zending in de residentie Timor, Mededeeling van mege het Nederlandsche Zendinggenootschap, vol. 21, pp. 269-89, Rotterdam.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2015. Tracing Ancient Networks; Linguistic, Hand-woven Cloths and Looms in Eastern Indonesia, Ancient Silk Trade Routes, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte, Ltd., Singapore.pp. 53-

Fricke, Hanna, 2017. Nouns and pronouns in Central Lembata Lamaholot (Austronesian, Indonesia), Wacana, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 746-771.

Fricke, Hanna and Klamer, Marian, 2018. Reconstructing Linguistic and Social Histories of the Lamaholot region, Seventh 7th East Nusantara Conference, Kupang.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2019. Traces of language contact: The Flores-Lembata languages in eastern Indonesia, Ph. D. Thesis, Leiden University.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2020. Personal communication.

Grangé, Phillipe, 2015. The Lamaholot dialect chain (East Flores, Indonesia), Language Change in Austronesian languages, Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Canberra.

Guy, John, 1998. Woven Cargos: Indian Textiles in the East, Thames and Hudson, London.

Hudjashov, Georgi; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Lawson, Daniel J.; Downey, Sean; Savina, Olga; Sudoyo, Herawati; Lansing, J. Stephen; Hammer, Michael F. and Cox, Murray P., 2017. Complex Patterns of Admixture across the Indonesian Archipelago, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 2439–2452, Oxford University Press.

Hull, Geoffrey, 1998. The Basic Lexical Affinities of Timor’s Austronesian Languages: A Preliminary Investigation, Studies in Languages and Cultures of East Timor, vol. 1, pp. 97-174, University of Western Sydney, Macarthur.

Hull, Geoffrey, 2006. Timorese Plant Names and their Origins, Monografias do Instituto Nacional de Linguōstica (Timor-Leste), no. 1, Instituto Nacional de LinguÌstica.

Irwin, John, 1955. Indian textile trade in the seventeenth century: 1. Western India, The Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. 1, pp. 15-44, Ahmedabad.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/lama1277-ileap

Kleiweg, J. P., 1931. Quelques crânes de l’île Lomblen (Archipel Indien), Anthropologie, vols 9-10, pp. 129-143.

Lianurat, Antonius Buga, (Antoni Lebuan), Head of Culture, Lembata Culture and Tourism Office, 2013 – 2020. Personal communication and translation.

Lundberg, Anita, 2003. Voyage of the Ancestors, Cultural Geographies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 64-83.

Melalatoa, Junus, 1995. Ensiklopedi Suku Bangsa di Indonesia Jilid L-Z, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Michels, Marc, 2017. Western Lamaholot: A cross-dialectal grammar sketch, MA Thesis, University of Leiden.

Nagaya, Naonori, 2011. The Lamaholot Language of Eastern Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, Rice University, Houston, Texas.

Pires, Tomé, 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, vol. 1, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Prakash, Om, 2009. Indian Textiles in the Indian Ocean Trade In the Early Modern Period, The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1984. Clothing, Ritual and Society in Tenganan Pegeringsingan (Bali), Verhandlungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Basel, vol. 95, pp. 191-241.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1991. Balinese Textiles, British Museum Press, London.

Rutan, Margarita I. M.; Daga, Lukas Lebi and Wutun, Monika, 2018. Studi Etnografi Makna Komunikasi Ritual Adat Werung Lolong pada Masyarakat Lewohala di Desa Todanara, Kecamatan Ile Api, Kabupaten Lembata, Provinsi Nusa Tenggarah Timur, pp. 1149-1163,

Schoutens, Wouter, 1676. Oost-Indische Voyagie, Jacob van Meurs and Johannes van Someren, Amsterdam.

Siebert, Lee; Simkin, Tom, and Kimberly, Paul, 2010. Volcanoes of the World, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Sumber Group Orang Baopukang, 2015. Sejarah Kampung Adat Lewohala, Kompasiana 25 June 2015: https://www.kompasiana.com/sandro.wangak/550b24cd813311df78b1e503/sejarah-kampung-adat-lewohala

Ten Kate, H. F. C., 1894. Een en ander over anthropologische problemen in Insulinde en Polynesië, Feestbundel aangeboden aan Dr. P. J. Veth, Leiden.

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of our friends on Ilé Apé, including its many incredible spinners, dyers and weavers, for answering the many questions we have asked over the past fifteen years, as well as Tony Lebuan, who we first met in Larantuka in 2013. We could not have written this webpage without their help.

Publication

This webpage was published on 15 March 2020.