Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Raijua Textiles Part 1:

The Complex Textile Culture of Raijua

Textile Collections

The Tao Leo Funeral Feast

The Raijuan Ritual Calendar

The Habemaare Banni Kedo Ritual

The Pana Jami Ritual

Two Glimpses of Raijuan Textiles in the Past

Textile Thefts on Raijua

Textile Production on Raijua

Bibliography

Raijua Textiles Part 2:

The Classification of Raijuan Ikats

Women's Costume

The Miniature Sarongs of Raijua

Èi Taba

Èi Wodattu

Èi Worapi

Èi Huri Wue

Èi Raja

Èi Mea

Èi Hebe Mea

Èi Ledo

Èi Beke Dara Womèdi

Èi Pudi

Èi Kubae and Èi Kemoru

Èi Dua Hebe

Men's Costume

Higi Taba

Higi Worapi

Higi Huri Wue

Higi Mea

Higi Pudi Wo Ie Rai

Higi Wohappi

Higi Pudi

Funeral and Other Sacred Cloths

Acknowledgements

The Complex Textile Culture of Raijua

In the past Raijua Island had an incredibly complex culture of cloth – textiles were not just an expression of a person’s identity, but had spiritual and political power as well as high economic value. Almost every ritual, of which there was a multitude, involved the use of specific textiles. The rules for how cloth was used were so highly complex they were almost overwhelming, laid down by the ancestresses Banni Kedo and Marega some 15 generations ago. Failure to abide by the rules set down by these powerful witches could bring about misfortune.

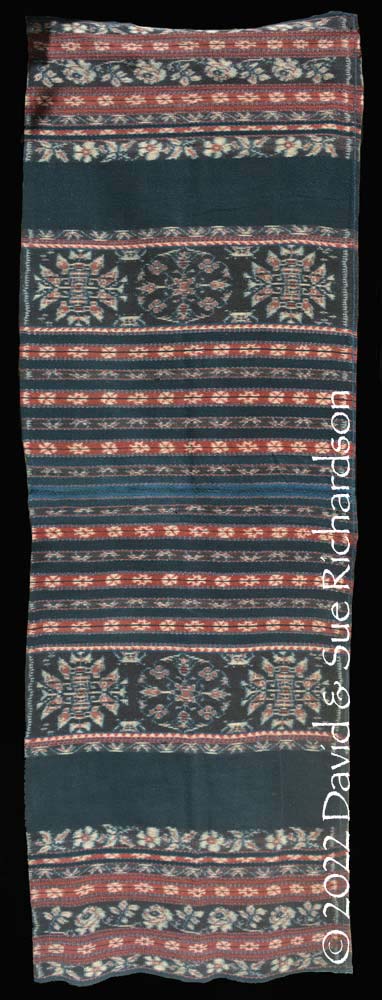

A woman’s èi worapi tube skirt

Family heirloom, Raijua

Being a poor island where cotton, food and water have often been scarce, ikat textiles were highly valued. Ikat was not only a precious private property but also vitally important common property for each wini and kepepe.

In the private sphere costume was, and to an extent still is, an expression of a person’s identity on Raijua, indicating their matrilineal lineage. Each wini or kepepe has its own unique limited range of motifs that have been inherited over many generations. In the past, by looking at what someone was wearing, a Raijuan would know their matrilineal group affiliation, their social rank and economic status and even their social situation (Kagiya 2010, 95). Some very special ikats indicate a genealogical connection to Marega or Banni Kedo. Others can only be worn or used by those who qualify to do so.

When a person dies, their corpse is wrapped in textiles decorated with motifs exclusive to their wini, and a flower motif symbolising that wini is drawn on their forehead and cheeks. At their funeral festival, ikats unique to their wini would be publicly displayed so that the ancestors of that wini would recognise the deceased in the after life.

A matrilineal group’s motifs were highly valued and carefully guarded. In the past, if a woman discovered that the motifs of her wini had been used by a member of another wini without permission, she was permitted to strip the sarong from that person on the spot (Kagiya 2010, 98). There is a folk memory of an incident that happened a long time ago when a woman from one wini copied the motif of another wini without its authority and as a punishment was expelled by her wini to become a slave in the wini that she offended (Kagiya 2010, 133).

To complicate matters further, many motifs had rules restricting their use to certain times, certain locations or specific occasions. Each wini had set rules specifying which type of ikat with which motifs people should wear to participate in each ritual. For example, the use of three motifs was restricted to the Tao Leo ritual.

Textiles were also of supreme importance in the communal sphere – they established the social hierarchy of individual matrilineal groups and were also the key to permit the performance of important rituals.

Every wini or kepepe maintained a stockpile of communally owned textiles, woven by the women of that matrilineal group over many generations. They were carefully folded and stored in numerous kepepe (lontar palm leaf baskets) inside the amu ina apu, the house of the ancestors, a tiny palm thatched hut communally owned by every wini which can only accommodate a few women sitting in a crouched position. Textiles held in the amu ina apu could only be made from cotton that had been hand spun and completely naturally dyed.

Some of the highest status matrilineal groups held hundreds of cloths in their amu ina apu, with the kepepe baskets individually named and assigned a rank to indicate their status. Wini Mako, the top ranking wini of the hubi ae, had several hundreds stored in ten large baskets. The number owned by kepepe Jingi Wiki exceeded 450.

Members of kepepe Jingi Wiki standing in front of their amu ina apu, photographed by Akiko Kagiya

In addition to the baskets of hand-woven cloth kept inside the amu ina apu, the matrilineal group also stored their pots for dyeing, tools and equipment for weaving and ornaments inherited from their ancestors (Kagiya 2010, 22). Their rituals were performed in an open area in front of, or close to, the amu ina apu.

Most importantly, the rank of each wini was determined by the quantity and type of ikat stored in their amu ina apu, especially the highest status rena kebao. In 1990, some wini owned hundreds of cloths. Since then many have been stolen. However most wini owned only seven or less rena kebao. There were three exceptions, especially wini wanynyi rato, which owned 29. At certain ritual events the textiles held by each wini are taken from their baskets and put on public display to be aired. Because Raijua is an extremely poor island with limited resources, permission was sometimes given to a woman weaving a cloth for the wini’s kepepe basket to make a miniature version.

The rank of one’s wini not only determined its member’s social status but also had important financial implications since it influenced the bridewealth that would be required for a young man to marry one of its daughters.

These stores of textiles were also an essential requirement for the performance of the traditional Tao Leo funeral feast, where they are used to decorate the house of the deceased so that the ancestors will recognise the wini of the deceased. Tao Leo is an extravagant event involving animal sacrifices that can last from 3 to 9 days and stretches the resources of the wini concerned.

In addition there were different types of textiles owned communally by the patrilineal groups – the udu and the kerogo. These were not indigenous weavings but foreign trade cloths, which the islanders believed were obtained about 600 years ago from ‘people of underground’. There were four types: lai rade and patola were silk (the latter silk double ikat patola from Gujarat), while huda and hide were cotton or cotton/silk. They too were essential requirements for holding certain rituals, including Tao Leo, and were worn by the Mone Ama over their shoulders.

Return to Top

Textile Collections

While museum and private collections of textiles from Savu are widespread, those from Raijua are quite rare, probably the largest being the fifty-nine examples acquired by Brigitte Khan Majlis in 2011 for the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum of ethnography in Cologne just before she retired. Unfortunately these lack any provenance. The Richardson Collection contains over twenty examples, some of which were ethically collected in the field with their provenance recorded for posterity.

It is likely that the majority of the textiles from Raijua held outside of Sabu Raijua Regency today were once stolen from the island.

Return to Top

The Tao Leo Funeral Feast

When a person dies on Raijua they are buried within three days, placed in a sitting position and wrapped in shrouds. In the case of a man, the body is first washed by his sister and then wrapped with a textile woven many years previously by his eldest sister. This is followed by further textiles brought by his other sisters (Kagiya 2010, 60). In the case of a woman, she is wrapped in the textiles of her own matrilineal group gifted by her brothers and maternal uncles.

If the wini/kepepe and the udu/kerogo to which that person belonged qualified – and also if they agreed – an extravagant funeral ritual called Tao Leo could be held in the following month of Bhagarae Ae (June). This was the grandest feast held on the island and was not only to mourn for the deceased but also to celebrate the wini/kepepe and udu/kerogo to which they belonged. Tao means make and Leo means tent, because activities took place under a tent covered with lontar palm leaves erected beside the house of the person who died. Raijuans believe that the first Tao Leo was performed by the uncle of Maja to mourn the death of Maja’s mother.

The Tao Leo is a major festival demanding a huge amount of time, effort and money for the matrilineal and patrilineal groups involved. It not only requires the participants to be fed and entertained but demands the sacrifice of many domestic animals including water buffalo. It is organised by the matrilineal group of the deceased. Because of the region’s poverty, in 1974 the local authorities in Seba attempted to outlaw this costly practice. Ironically while it has no longer been performed on Savu, it continues on much poorer Raijua.

There were five different types of Tao Leo, ranging in duration from 3 days to 9 days. The longest was the Tao Leo Penuni, which could only be held for members of hubi ae and involved the sacrifice of ten water buffalo. Very few wini were able to stage such an event. As one Tao Leo was not permitted to overlap with another Tao Leo, no more than three could be performed in any one year. In the decade up to 2010, only 13 were held, split evenly across both hubi.

During Tao Leo, many textiles called hara (meaning hope) are taken from the amu ina apu of the deceased person and are carried to the house in which the mourning is taking place, normally on the head of a woman from the same wini. There they are put on public display so that the deceased can be recognised by the ancestors of their wini (Kagiya 2010, 179).

The hara cloths are always displayed in pairs with a woman’s cloth and a matching man’s cloth. There are rules that determine which types of ikat textiles qualify to become hara cloths, how many should be used and in which order they must be displayed, depending on which type of Tao Leo is taking place. For the simplest type of ritual only five hara cloths were required but for Penuni it could be as many as twenty-five.

Return to Top

The Raijuan Ritual Calendar

For a poor island, Raijua had an extremely rich annual cycle of rituals, many of them agriculturally related - coinciding with the sorghum, mung bean and lontar palm sap harvests. Ikat was always an essential component of any big ritual held on the island.

| Month | Agricultural Rituals |

Non-Agricultural Rituals |

|

| Raijuan | Gregorian | ||

| Matina | November | ||

| Ko’oma | December | Pengaddu Wango | |

| Wari Ma | January | Melolo Ma | Kelia Harro |

| Leko Wila | February | Leko Wila Penggadu Kelangngo Ngaa Liha Hura Kabha |

|

| Daba | March | Daba | |

| Bhanga Liwu Ae | April | Bhui Ihi | |

| Bhanga Liwu Ro | May | Pelale Kowa Mone Weo | |

| Bhangarae Ae | June | Pedoa Peoke Pehele |

Ngaa Melaa Meharru |

| Bhangarae Ro | July | The hungry month | The hungry month |

| Rokoko | August | Gapedue Penanggapi Pearre Kii Rato |

|

| Wadu A’a | September | Pekaa Ngaa Due Ngaa Merao |

|

| Wadu A’ri | October | ||

(Kagiya 2010, 192-193)

Dancers with lontar palm baskets containing mung beans tied to their feet performing the pedoa circle dance, linked to a folktale about Banni Kedo searching for her son.

The nature of these various rituals is summarised below:

| Ritual | Summary |

| Pengaddu Wango | The most important agricultural ritual in which brothers donate roughly 5kg each of sorghum and mung beans to their married sisters. In memory of the ancestor Hawu Miha who planted crops for his sister and wife Babo Miha after she had left the island. |

| Melolo Ma | A seed planting ritual for sorghum and mung beans. |

| Kelia Harro | A horse racing ritual to commemorate the warriors who fell in battle. |

| Leko Wila | The ritual to pray for a good mung bean harvest. |

| Penggadu Kelangngo | A ritual to cleanse pests from the mung bean fields |

| Ngaa Liha | A ritual to delineate the field of each udu by sowing rice seeds along their borders. |

| Hura Kabha | The ritual of shelling the mung bean pods. |

| Daba | The ritual cockfights held between Upper and Lower Raijua. Only men who own a special daba ikat cloth can participate. These are usually the eldest sons of each family and the Mone Ama, who normally wear a higi mea woven by their sister (the red signifying braveness) and the heads of the udu who must wear a higi taba and carry a spear in recognition of past wars. |

| Bhui Ihi | The cleansing ritual in which everyone cleans themselves, their domestic animals and the graves of their ancestors. |

| Pelale Kowa Mone Weo | The ritual of sending the first crops to Mone Weo, the ancestor who ruled Raijua and was defeated by Maja. |

| Pedoa | The pedoa dances are held nightly to celebrate the sorghum and mung bean harvests. |

| Peoke | The ritual battle fought with palm stems and shields to encourage a good lontar palm sap harvest. |

| Pehele | The ritual battle fought with hard palm seeds to encourage a good lontar palm sap harvest. |

| Ngaa Melaa Meharru | The closing ritual of the agricultural season, a female festival for hubi iki to thank Banni Kedo and for hubi ae to thank Marega for teaching the islanders how to spin, dye and weave. |

| Gapedue | The ritual of placing mung beans on the notches of lontar palm trees. |

| Penanggapi | The ritual for purifying the tools used for palm tapping. |

| Pearre Kii Rato | A ritual to open the beginning of the palm tapping season. |

| Pekaa Ngaa Due | The ritual of shouting loudly to encourage the palm sap to rise. |

| Ngaa Merao | The lontar palm thanksgiving festival involving animal sacrifice and a thanks to Rai Ae, the first man to tap the lontar palm tree. |

Return to Top

The Habemaare Banni Kedo Ritual

One of the grandest festivals held on Raijua is called Habemaare Banni Kedo (‘cultivate Banni Kedo’s paddy fields’). It is held every six years, dedicated to the powerful female ancestress Banni Kedo (Kagiya 2010, 80-88). In addition to being a ritual of ancestor worship it is also an agricultural fertility ritual held to ensure a rich harvest and prosperity for the island. It is conducted in April/May at Daihuli, led by the Mone Ama. Sheep are sacrificed during the festival and a water buffalo is sacrificed at its climax. It is ironic that such an important festival is focussed on rice, which is almost impossible to grow on the island.

Return to Top

The Pana Jami Ritual

The second grand festival is called Pana Jami (‘hot and holy forest’), also held every six years and dedicated the powerful male ancestor Maji. Although held independently of Habemaare Banni Kedo it is seen as complementary to it. One is considered meaningless without the other.

Pana Jami is held in June at Jami Ae (‘big forest’) in Kolorae, western Raijua, and is again led by the Mone Ama (Kagiya 2010, 88-91). It is essentially a male ritual and at least one man from every household must participate – the eldest son. The men wear a special Pana Jami higi blanket decorated with the motifs of their wini, woven by their sisters. Several black boars, the preferred food of Maja, are sacrificed and their meat is shared out among the participants.

Return to Top

Two Glimpses of Raijuan Textiles in the Past

There are few mentions of Raijuan costume in the historical accounts. The Heidelberg naturalist Salomon Müller never visited Savu or Raijua but in November 1829 he had good views of the north coasts of both islands as he returned to Java from Kupang on his research vessel the Triton. On Timor he had obtained some information about Savu and its small neighbour. He was told that the Raijuans distinguished themselves from the Savunese through their dress (1857, 279):

[The dress of the Savunese men] consists of a similar long shawl-like cloth, like the Rottinese, Timorese and other neighbouring islanders use; among the Savunese, these coarse cotton blankets have a dark, black or bluish ground, over which, along the length of the cloth, run many broad, red stripes, between which various figures of lighter colours, which on the whole give a not unpleasantly colourful appearance. The women wrap the lower part of the body in a variegated sarong that reaches to the knees or even lower, while they cover the bosom with a shawl cloth, which is passed under the arms and tightened in front. The inhabitants of ‘Randjoea’ are mainly distinguished from the Savunese by the clothing, which with them is mostly white; their long shawl cloths look much like a bed sheet, and the fabric is also somewhat less heavy and coarse than those of their neighbours. However, both ends are likewise decorated with fringes.Both sexes, on Savu and ‘Randjoea’, wear the hair straight and long; the men gather it in a bundle at the back below the crown, and then, [ . . . .] wind a European or Chinese cotton or silk handkerchief around their head; the Randjoeans, however, prefer a pure white. The women, on the other hand, always go bareheaded, wear the hair smoothly, but parted in the middle, from the forehead to the crown, and tie it backwards into a thick bun that hangs long at the nape. They usually have their front teeth completely filed down to the gums, which they consider clean. Silver and gold necklaces of fine wire braided, cords of glass and other beads, bracelets of silvery gold, ivory or also of thick copper wire, and other such ornaments, are otherwise quite common among these people and testify to their longing for finery. Their taste, in this regard, is, however, somewhat more chastised than that of the more eastern islanders we have described.

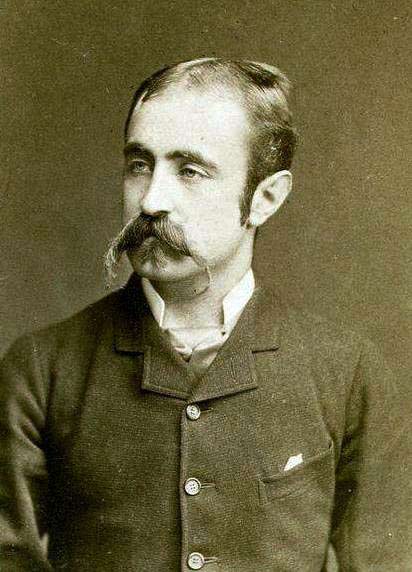

The Dutch anthropologist and linguist Dr Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate briefly visited Savu in 1891, commissioned by the British Royal Geographical Society under the auspices of the Dutch to explore the islands of eastern Indonesia.

Dr Herman ten Kate

He commented on the white ‘hidji pudi’ fringed shawls worn by the men of Raijua, which differed from the coloured ‘hidji hoeri’ (higi huri) worn on Savu (1894, 698-699).

[The sarongs] are distinguished by colour into ai-medi blue (literally black) and ai-hoeri, coloured sarongs. The selimut or scarves (hidji; the singgi of the Sumbanese) are exceptionally beautifully woven and perhaps the best, and because of their colour and decoration the most tasteful of the Timor group. Without an image, a clear description is impossible. The colourful hidji are distinguished by the word hoeri, the white by poedi. The latter variety, also provided with fringes, is preferably worn on Randjoewa. When the Savunese is not wrapped in his scarf, it is peculiarly folded lengthwise and wrapped around the torso, except that it passes across the chest and hangs down over the shoulder blades. The jewellery is very similar to that of the other peoples of the Timor group, including habas of gold and silver thread, bracelets of the same metal, or of black coral (Antipaihes), etc.

It is unclear why it was believed that men on Raijua dressed in the white higi pudi while those on Savu did not. The latter also wore the same white cloths at certain times and for certain occasions (Duggan 2001, 57). Dancers wore them to perform the Ledo dance at the Tao Leo ceremony and leaders wore them at times of peace.

Return to Top

Textile Thefts on Raijua

In the early 1980s it gradually dawned on a few islanders with criminal leanings that the unguarded amu ina apu contained a considerable quantity of valuable naturally dyed hand spun cloth that would fetch high prices if sold to dealers in Kupang. In 1983 many textiles communally owned by wini Raja were stolen from its amu ina apu, a massive blow to its pride (Kagiya 2010, 215). Its members sacrificed sheep in order to seek forgiveness from the important ancestress Banni Kedo. More cloth was stolen from them in 1991.

After 1991 cloth thefts turned into an epidemic. Incredibly some of the culprits were the female leaders of the winis themselves, the Banni Aa. By around 1995 all of the ikat held as common property by the most powerful winis had been stolen (Kagiya 2010, 212). Ikat was not only stolen from each wini once, but many times. Fearful that they would no longer have enough hara cloth to perform future Tao Leo funeral rituals, it became essential that the members of each wini began dyeing and weaving straight away to restore the situation in its amu ina apu. Of course such cloths had to be made from naturally dyed hand spun cotton but at that time it was very difficult to obtain a sufficient quantity of hand-spun yarn on the island and the weavers were too poor to buy hand-spun yarn on Savu or further afield.

Cloth thefts continued, forcing many women to devote considerable time to weave the vital hara cloths and other ikats required to maintain the Tao Leo ceremonies. Even some of the highest status kepepe such as Jingi Wiki began to use commercial yarns and chemical dyes mixed with natural indigo and morinda (Kagiya 2010, 221). However it was only much later in 2000 that several high status wini decided to reposition their amu ina apu to more secure locations.

As textile thefts continued through the 1990s, many matrilineal groups had their inventories of precious textiles decimated. Virtually every wini had nearly all of the ikats inherited from their ancestors stolen (Kagiya 2010, 132). In the past these holdings were essentially the group’s registry of their designs that could be used to establish their ownership in any copyright dispute. Following the thefts there were a number of disagreements in the 1990s between wini concerning the ownership of motifs, which were arbitrated over by village chiefs. Reconciliation sometimes demanded a ritual animal sacrifice.

The detailed rules set on every aspect of making and using ikat laid down by Marega and Banni Kedo even went so far as to meticulously specify how to respond to the theft of textiles (Kagiya 2010, 213). For example, food offerings had to be made to Banni Kedo to beg her forgiveness for having lost the ikat and the replacement textiles had to be woven in a predetermined order from natural materials under a cotton tree located well away from the amu ina apu. At a later stage a sow had to be sacrificed. While many wini worked hard to replace their stolen textiles according to these rules, some of the smaller ones admitted defeat.

It became harder to stage important rituals. During the period 1990 to 2010 many women became engaged in full time seaweed farming and had little time left for weaving. In addition many of the knowledgeable male and female ritual leaders of the matrilineal groups, the Mone Ama and Banni Aa, passed away taking their detailed knowledge about the ritual use of textiles to the grave. Raijua’s rich textile culture was in terminal decline.

By 2010 machine-spun yarn and chemical dyes were in common use on Raijua for the production of everyday sarongs and blankets (Kagiya 2010, 94). The number of weavers making hand-woven cloth had by then decreased sharply (Kagiya 2010, 215). Today there are still a handful of women in Upper Raijua who can still spin cotton and make natural dyes but in Lower Raijua there is only one – the 77-year-old Getreda Kana Koy.

As Akiko Kagaya made clear in 2010 (213):

Nowadays, 100% hand-woven and 100% natural-ingredient-dyed cloth is rare and precious.

Today the proportion of islanders who wear ikat has declined sharply. Younger people no longer wear traditional costume, but dress in jeans and t-shirts.

Return to Top

Textile Production on Raijua

In the past all women were taught to weave when they were little so that by the time they were 14 or 15 years old they could dye yarns and weave cloths by themselves without assistance. A sister was first obliged to weave a set of funeral shrouds for her brother’s funeral (Kagiya 2010, 53).

In most of eastern Indonesia only women traditionally bound, dyed and wove ikat cloth. On Raijua there was never any restriction on men doing the same, and Akiko Kagiya even discovered a man dyeing and weaving cloth because his wife was too ill to do so (2010, 97). Men are also always responsible for twisting and knotting the fringes on blankets and belts.

Furthermore, dyeing skills were never kept secret on Raijua as they were on other islands such as Sumba.

Cotton

Because domesticated cotton has an inherent ability to withstand drought, one might have expected that it would grow well on a small dry island like Raijua. While cotton requires some rain during the planting period, drought is essential during the latter growth phase – especially once the boll has burst when rain can wash away fibres and encourage rot.

On Raijua cottonseeds were mostly planted in November. In a normal year the rainy season starts in late November, the hottest month of the year, while the highest rainfall occurs in December. There is a minimal level of rain from February to early May and then effectively none until November. July is the coolest month. However the rainy season on Raijua is highly unreliable and the island has often experienced periods of prolonged drought when the late rains have failed to appear, as in 2015 and 2016, and in 2020. In such years there is insufficient early rain for the cottonseeds to germinate. When the rains eventually arrive, their duration is insufficient for the young plants to become established. Consequently the local supply of cotton on Raijua has always been insufficient to meet local weavers needs. In the past Islamic traders from Adonara visited Raijua and Savu to trade raw cotton for gula Savu. In recent years the well-know weaver Getreda Kana Koy even arranged for her husband to bring back raw cotton from Maumere.

According to Peter ten Hoopen (2018, 297):

On Raijua the main crop is cotton, which is traded for food and other essentials with Savu, ....

This is completely misleading. On Raijua the main crops by far are sorghum and mung beans. Raijua always suffered from a shortage of cotton, far too little of which was ever grown to permit any trade with Savu or anywhere else.

Cotton is known locally as wèngu and today a significant number of older women still know how to process it, although most younger ones have never been taught. When seaweed prices dropped dramatically in 2016, many women could no longer afford commercial yarn and reverted to using hand-spun cotton.

The processing of raw cotton was similar to that followed on Savu. Weavers did not have mechanical gins or spinning wheels. Cotton bolls were deseeded using a roller and a hard wooden board, after which the fibre was cleaned and fluffed using a bamboo bow (wuhu). The cotton was then hand spun using a drop spindle called a harru (heru on Savu). Some spindles have hardwood whorls but some are made from local coral limestone or fishbone. As on Savu, women preferred to spin in a sitting or kneeling position, support the spinning spindle on the floor or on a board or a plate. This reduces the yarn tension and makes it possible to spin a finer yarn.

A woman on Raijua pretending to drop spin using a spindle fully loaded with pre-spun yarn

Two harru drop spindles from Raijua

Left: From Ledeunu with a fishbone whorl previously owned by Getreda Kana Koy

Right: From Udju Dima with a limestone whorl. Richardson Collection

The spun yarn was wound from the spindle into a ball and then transferred to a niddy-noddy to stretch and set the twist and at the same time measure the amount that was needed to be stretched onto the binding frame.

A lore niddy-noddy in a house at Ledeke

Because Raijua was poor and the textiles owned communally by each wini and kepepe had to be woven from hand spun cotton, the island was slow to embrace commercial machine-spun yarn. However as already discussed, by the 1980s many weavers were using commercial cotton to weave non-adat textiles, even in the remoter areas like Kolorae. After the cloth thefts in the early 1990s weavers switched from hand spun yarn to commercial cotton en masse. Following the boom in seaweed faming, women completely stopped planting cotton. In 2008 Getreda Kana Koy formed a small weaving group with her extended family called Mira Le Hari and began planting cotton once again. However this project lost momentum and Getreda now obtains raw cotton from Flores Island.

Today almost all weaving on Raijua is done with machine spun cotton and Wantex chemical dyes sourced from shops in Seba. Using commercial cotton a weaver can increase her productivity enormously, making up to thirty textiles a year.

A crude kedia swift and a ball of commercial yarn in Ledeunu

Weavers use homemade kedia swifts to wind skeins of commercial yarn into balls prior to warping up and bonding.

Indigo or Dao

Today only a limited amount of natural dyeing takes place on Raijua, the majority of which is limited to indigo, known locally as dao. The locally acknowledged master of indigo dyeing is Getreda Kana Koy, who lives just behind the beach in west Ledeunu.

Unlike cotton on Raijua, indigo is not in short supply. Indigo thrives like a weed during the rainy season but soon wilts and desiccates with the onset of drier conditions. Grazing livestock will quickly devour fresh indigo, so weavers have to make the most of the few months available for harvesting and processing the dye. This is especially so in years of drought.

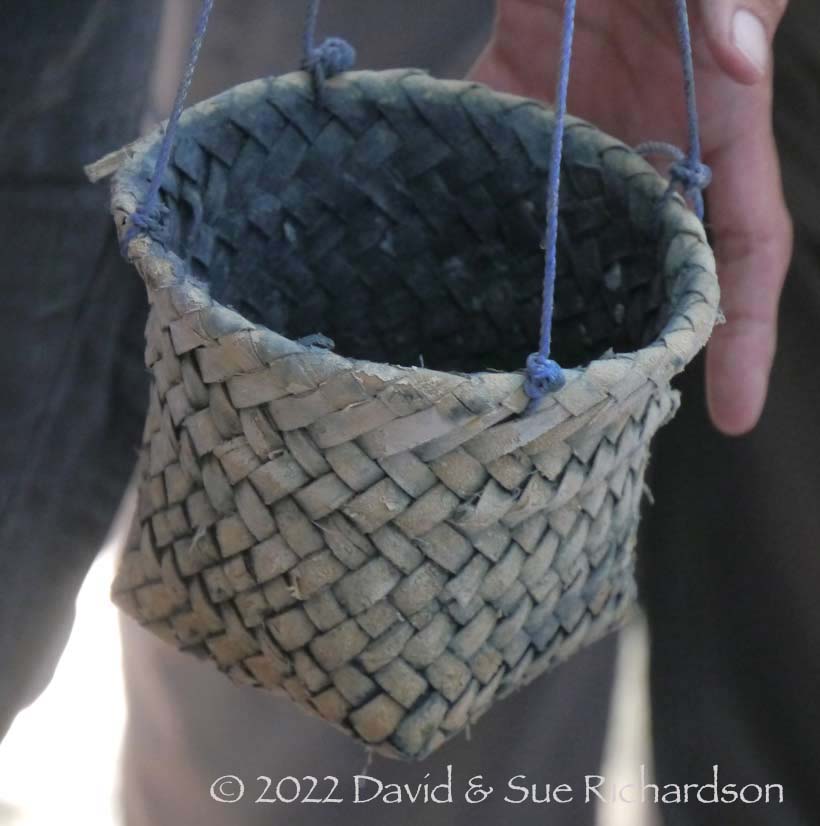

Because of this, most indigo was processed into solid cakes that could be stored and used at a later date during the dry season. Getreda Kana Koy demonstrated the technique to us in 2018. The harvested indigo is packed into a fired earthenware pot filled with seawater and lime powder, then covered and left in the shade for a week. The indigo plant remains are squeezed dry by hand and removed from the pot so that the contents can be aerated to precipitate the dissolved leuco-indigo as a thick indigo paste. The contents of the pot are poured into a small, tightly woven lontar palm basket, which is then hung up and left for three days, allowing the liquid to strain away and the paste dry into a cylindrical block. The indigo cake is then removed and stored in a dry place inside the house. Ten cakes are needed to produce enough dye to make one indigo èi pudi mau sarong.

Above and below: the small straining basket hung outside the house on a bamboo frame used for drying the indigo dyed yarns

Solid indigo cake made by Getreda’s family

To process the indigo cake into useable dye, the solid indigo must be transformed back into soluble leuco-indigo. This is done by dissolving it in alkaline ash water made from the burnt shells and seeds of the Java Olive (Sterculia foetida), locally known as nitas or képaka tree.

The seedpods of the nitas tree

Getreda Kana Koy with her indigo dye pot at Ledeunu

The resulting dye bath can be kept for up to three weeks. Yarns must be dyed multiple times and completely dried in between, the number of immersions required depending on the depth of colour required. Some forty immersions are required to produce a near black, with the yarns soaked in each indigo bath for up to a month.

Morinda

Morinda citrifolia grows well on Raijua where it is known as kabbo (pronounced ‘keb’o’). The tree roots are normally harvested in the first part of the dry season around May. However very few weavers produce this dye today. We have not yet witnessed the local process ourselves but were told that for oiling they use crushed nitas seeds. As elsewhere in eastern Indonesia, for the aluminium mordant they use the dried leaves and bark of luba (Symplocos sp.). This cannot grow on low-lying Raijua so must be purchased in Seba having been imported from mountainous islands such as Sumba, Alor or Flores.

A mortar for pounding morinda root

Turmeric

Turmeric is locally known as kéwunyi or keoni and is only used sparingly for highlights.

Binding

The circular bundles of yarn are tensioned on a small binding frame, separated from each other by a length of tape that is interlaced between each bundle. In the past the bundles were always bound with thin strips of gebang palm leaf. Today bundles of commercial yarn are bound with strips of thin coloured plastic cut with a sharp knife from lengths of packaging tape.

Above and below: binding bundles of commercial yarns for a sarong using strips of thin plastic

Weaving

The ikatted circular bundles of yarn are separated and stretched on a stout wooden frame in the correct sequence, several women working together to make the fine adjustments required to achieve exact alignment. The cotton heddle is wound manually around the heddle stick and a bamboo pole sufficiently wide to make the correct sized loops.

A demonstration of heddle making at Ledeunu

Winding the heddle for an èi worapi sarong

The assembled yarns are transferred to the back tension loom along with the heddle. The sarong or blanket is woven on a circular warp, so the finished textile will either contain the two matching panels of a sarong or a single blanket.

Weaving a chemically dyed man’s blanket

The Current Level of Ikat Production on Raijua

A recent survey of industry and energy on Sabu Raijua by the statistical branch of Kabupaten Kupang identified 147 producers of woven ikat on Raijua, the largest number being located in western Kolorae. It is likely that this does not include women who weave as a recreation rather than as a full time activity. For comparison, the total population of females on Raijua was 5,000.

Woven Ikat Industry

Total Manpower

Desa/Kelurahan |

Woven Products | Woven Ikat |

| Kolorae | 133 | 67 |

| Bolua | 54 | 36 |

| Ledeke | 6 | 7 |

| Ledeunu | 9 | 15 |

| Ballu | 10 | 22 |

| Raijua | 212 | 147 |

Woven products includes items such as mats

Source: Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Kupang

It is likely that in the past the majority of girls and women on Rajua would have been involved in ikat production in one way or another.

Return to Top

Bibliography

While much has been written on the history, culture and textiles of Savu, very little has been published in a similar vein about its more interesting smaller neighbour.

Duggan, Geneviève, 1995-1996. Matrilineal descent groups and weavings on the island of Savu, The Textile Museum Journal 1995-1996, vol. 34-35, pp. 54–73.

Duggan, Geneviève, 1999. Savunese ikat weaving: a sister-brother network, Proceedings of International ikat forum, pp. 137–144 and 184–185, Atelier Sarawak, Kuching.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2001. Ikats of Savu; Women Weaving History in Eastern Indonesia, White Lotus, Bangkok.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2004b. Woven Traditions, Collectors and Tourists: a Field Report from Savu, in Performing Objects; Museums, Material Culture and Performance in Southeast Asia,Fiona Kerlogue (ed), pp. 103-118, Horniman, London.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2009. The Genealogical Model of Savu, Eastern Indonesia, Journal of Indonesian Social Sciences and Humanities, vol. 2, pp. 163–177.

Fox, James J., 1977. Harvest of the Palm: Ecological Change in Eastern Indonesia, Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London.

Fox, James J., 1979. The Ceremonial System of Savu, The Imagination of Reality: Essays on Southeast Asian Coherence Systems, A. Becker and A. A. Yengoyan (eds), pp. 145-173, ABLEX publishing, Norwood, NJ

Hirose, Takaki, 2014. Survival Strategies of a Society Dependent on Borassus flabellifer during the Dry Season in Raijua Island, Eastern Indonesia: Analysis of Diet, Livelihood and Society, People and Culture in Oceania, vol. 30, pp. 52-72.

Hoopen, Peter ten, 2018. Ikat Textiles of the Indonesian Archipelago, Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong.

Kagiya, Akikio, 2010. Female Culture in Raijua: Ikats and Everlasting Witch-Worship in Eastern Indonesia, Japan Publications Inc., Tokyo.

Kagiya, Akikio, 2012. I became a "witch". Thirty-one years of research on women on Raijua, The Daily Jakarta Shimbun, 25 October 2012, Jakarta.

Kate, Herman F. C. ten, 1894. Verslag eener Reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesië, IV. Roti – Savoe, Tijdschrift van het Kon. Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. XI, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Müller, Salomon, 1857. Reizen en Onderzoekingen in den Indischen Archipel, gedaan op Last der Nederlandsche Indische Regering, Tusschen de Jaren 1828 en 1836, vol. 2, Frederik Muller, Amsterdam.

Roland, A. N.; Indrayaningsih and Agung Dwi Laksono, 2016. Daun Ro’Hili & Air Gula Sabu: Penyambut Bayi Baru Lahir, Etnik Sabu – Kabupaten Sabu Raijua, Unesa University Press, Surabaya.

Walker, Alan T., 1982. A Grammar of Sawu, Badan Penyelenggara Seri NUSA, Universitas Atma Jaya, Jakarta.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 4 February 2022.