Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Pahikung Part 1:

Introduction to Pahikung

The Pahikung Weaving Area

Weavers in Umalulu

Supplementary Warp

The Term Pahikung

Complementary Warp

The Choice of Yarns

Preparing the Warps

The Pahudu Pattern Guide

Programming the Supplementary Warps

The Pahikung Loom

Basic Pahikung

Luar Dalam Pahikung

Pahudu Rú Kalu Pahikung

Pa Ji Mbualang Pahikung

Tinu Pata Pahikung

Ndatta

Bibliography

Go to Pahikung Part 2

Introduction to Pahikung

East Sumba is internationally renowned for its warp ikat textiles, especially the dramatically decorated man’s blanket – known in the Kambera region around Waingapu as a hinggi. Yet its less well-known pahikung textiles, some of which incorporate warp ikat, are far more sophisticated and much more technically demanding to weave.

Pahikung is a weaving technique used on horizontal back tension looms that employs supplementary warps to embellish textiles with an infinite range of geometric and zoomorphic designs, many incorporating the rich iconography of Sumba Island. East Sumba is the only region in the entire Malay Archipelago where supplementary warp decoration has reached such a high degree of refinement.

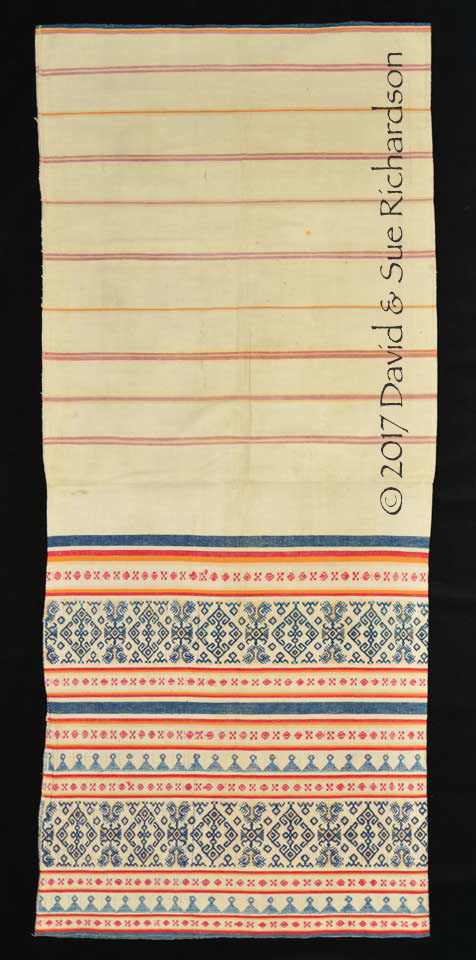

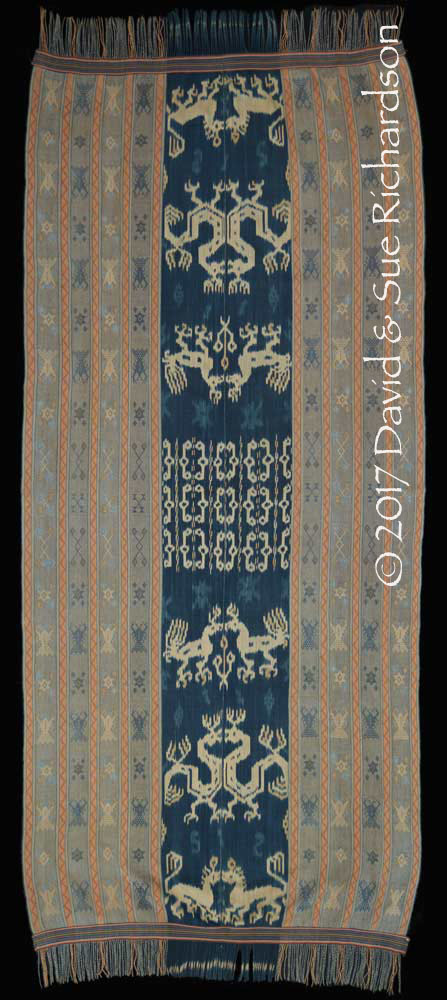

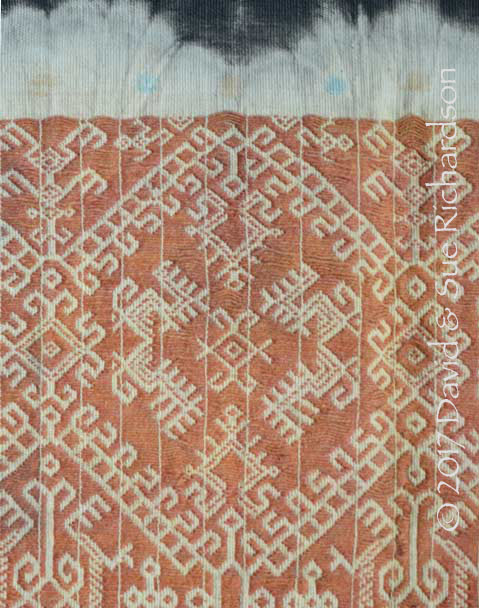

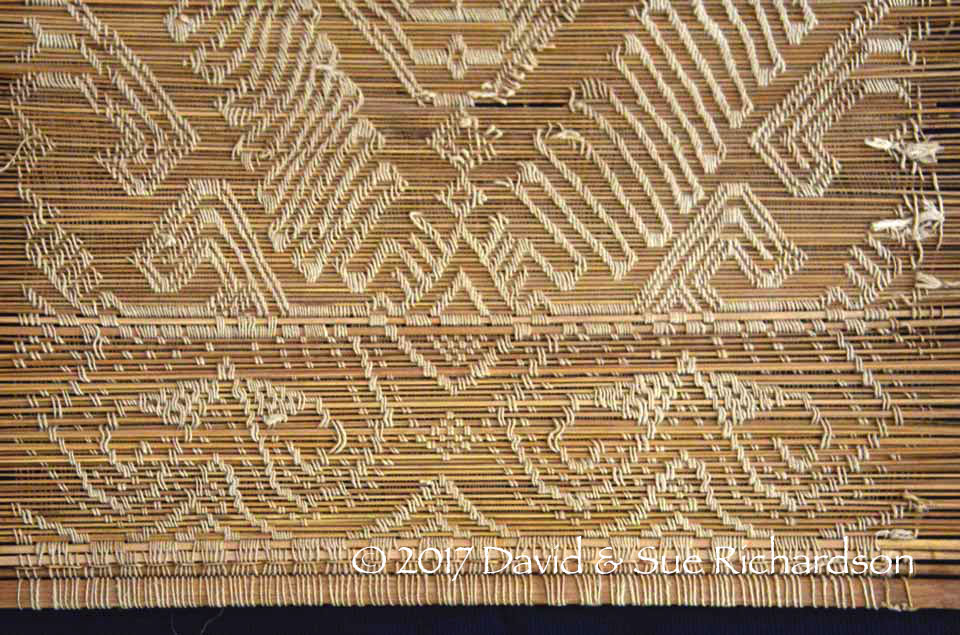

Geometric design of an early hand-spun lau pahikung, made in Tangguhang close to Baing in Wulla Waijelu in the mid-19th century. In the 20th century it was gifted to Tamu Rambu Lika Njanggang, who later married Tamu Umbu Bala Nggiku, the King of Karera. Richardson Collection

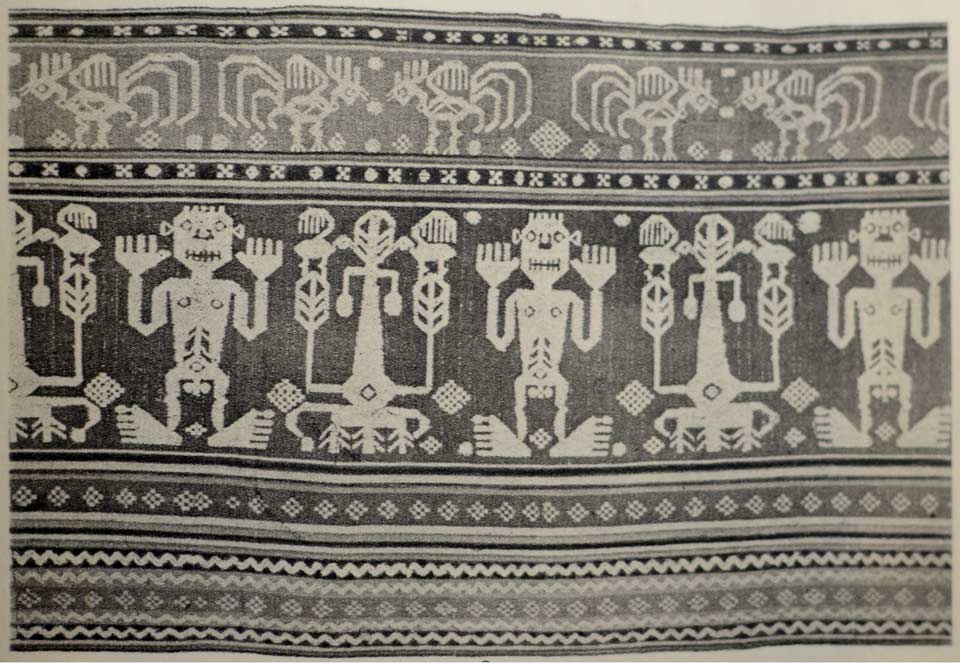

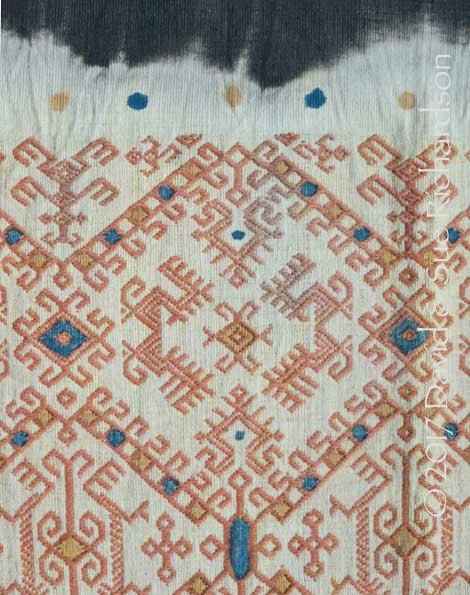

Detail from a lau pahikung collected by the artist Wijnand Nieuwenkamp in 1919

In the past pahikung was primarily employed to add dramatic decorative panels to women’s lau tubeskirts. Traditionally these were restricted to the maràmba or nobility, but today there are no longer any prohibitions restricting who can wear them. Neverthelass, lau pahikung remain expensive and beyond the means of most poor commoners and former slaves.

Three women from East Sumba dressed for a funeral feast at Watumbaka, to the east of Waingapu, in 1932 – centre: a noble dressed in a ceremonial lau pahikung hiamba;

left: a bare-breasted slave dressed in a plain mud-dyed lau pakapihak;

right: a commoner dressed in a beaded lau hada

(Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen)

More recently pahikung has been used to decorate halenda sashes and long rohu banggi torso wrappers. It has been, and occasionally still is, used by weavers in the villages of Pau and Parai Yawang to embellish or add side borders to men’s warp ikat hip or shoulder wrappers known as hinggi.

The Pahikung Weaving Area

Today pahikung is restricted to a small geographically confined coastal region in the Kecamatan Umalulu district of East Sumba, formerly the royal domain of Pau (the word ‘pau’ means mango). However during the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century it seems to have extended much further south, as far as the region of Wulla Waijelu bordering the southern coastline of East Sumba.

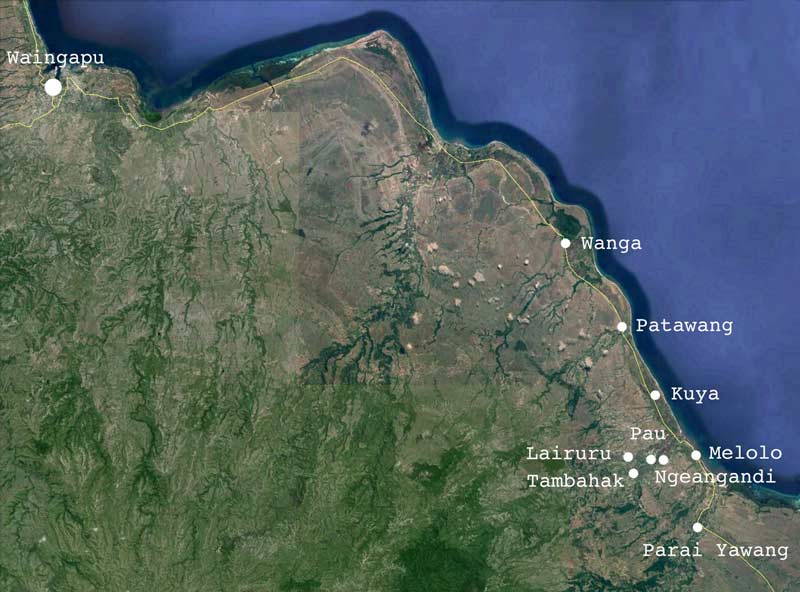

The pahikung-weaving region of East Sumba

(Image courtesy of Google Earth)

The modern pahikung weaving area begins at Wanga, about 44km due east of Waingapu. From there it continues along the coastal strip for almost 17km to the valleys of the Melolo and Lulukawaka rivers. It encompasses Patawang at the head of the Patawang River valley some 7½km south of Wanga, and Kuya - a further 3km south. The most well-known centre is the royal enclosure of Watu Panunggul, adjacent to the hamlet of Uma Bara, the royal centre of the former domain of Pau. Good quality pahikung can also be found in many of the surrounding villages such as Ngeangandi, Laihandang, Tambahak, Karunggu, Lairulu, Kanaka and Waimarang.

Some of the pahikung weaving villages on the east coast of East Sumba

An important outlying centre is the traditional village of Parai Yawang, just a few kilometres beyond Melolo, the royal centre of the former domain of Rindi. Parai Yawang is primarily an ikat-producing centre, but many of its noble families are closely interlinked by arranged marriages to the noble families of Pau. Many young noblewomen who grow up learning to weave pahikung in Pau move to join their future husbands in Parai Yawang, where they are then taught to become masters of warp ikat. In addition, many young girls from Parai Yawang are sent to stay with relatives at Pau to learn how to weave pahikung.

The town of Melolo is not a pahikung-weaving centre. It is mainly inhabited by Savunese people whose ancestors were invited to settle there by the Raja of Umalulu in 1860 (Vel 2008, 32). However Melolo does hold a weekly early morning pahikung market, which operates from 5am to 7am every Friday. It is located in the hills several kilometres above the town. At some time in the near future, Melolo is expected to become the capital of the new Pahunga Lodu Regency, encompassing the districts of Umalulu, Rindi, Pahunga Lodu, Kahaungu Eti and Wulla Waijelu.

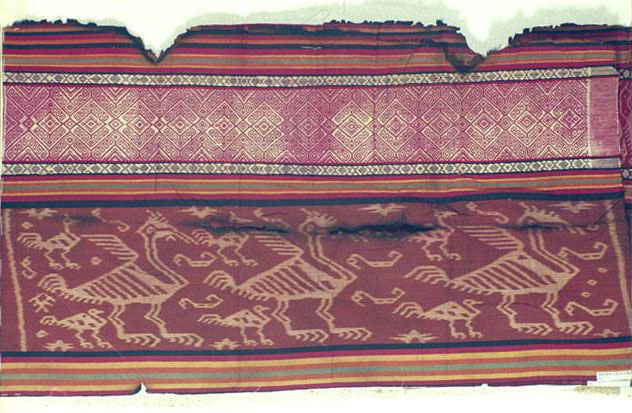

The pahikung technique was probably much more widespread in the past, extending all the way down to the southern coast. In the mid-nineteenth century the southern region of Wulla Waijelu, which lies between Pahunga Lodu and Karera, was another important pahikung-weaving region. Many fine old lau pahikung have been collected from this domain in recent decades. Alfred Bühler collected one example for the Museum für Völkerkunde in 1949 which he found in Baing, the main village in Waijelu.

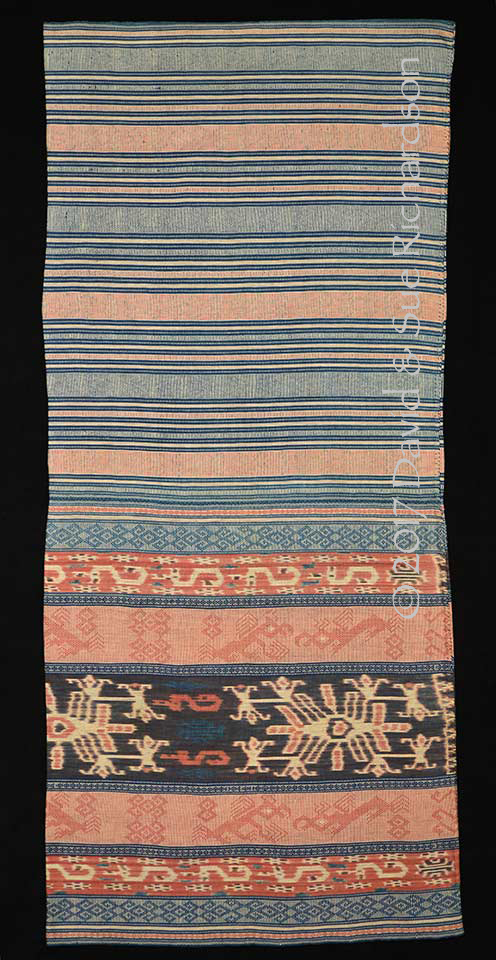

Part of a lau pahikung collected by Alfred Bühler in Baing, Waijelu, in 1949

However it seems that the pahikung weavers of Wulla Waijelu all originated from Umalulu. In the past, according to the noble families of Parai Yawang, many men in Waijelu took wives from the region of Pau. This has recently been confirmed by Johanna Wyllie, the Sumbanese wife of the late Australian surfer David James Wyllie, who still lives at Kalala close to Baing in Waijelu and knows several women in the local royal family who came from Umalulu. Despite this, the pahikung weavers of Waijelu still managed to develop their own regional designs and motifs.

Although there is no information to indicate when pahikung died out in Kecamatan Wulla Waijelu, it continued to be produced in Kecamatan Pahunga Lodu until approximately 1970. Warming and Goworski discovered a supplementary warp sarong in the important kampung of Kaliuda in the 1970s (1981, 138). The last pahikung weaver in the village had recently died and, because none of her daughters had learnt the technique, her pahudu patterns had been buried with her. A weaving technique that had survived in Kaliuda for many generations had finally been lost.

From the above, it seems that the pahikung-weaving region once stretched continuously from Kecamatan Umalulu in the north to Kecamatan Wulla Waijelu in the south, encompassing both Kecamatan Rindi and Kecamatan Pahunga Lodu.

Mysteriously the weaving technique does not seem to have strongly penetrated into the Kambera and Kanatang regions which lie to the north of Umalulu. Pahikung has been introduced into parts of Kambera - such as the district of Kawangu, just east of Waingapu - as a result of the arrival of pahikung weavers from Umalulu to join their new husbands following their marriage. For example, Rindi supplied noble wives to the royal families of Prailiu in Waingapu and to Kapunduk and Kanatang. Almost four decades ago, Warming and Goworski photographed a woman weaving a lau pahikung in Waingapu as well as a pahudu from the same region (1981, 137). Likewise we photographed girls weaving simple halenda pahikung hiamba at Maramata in 1991.

Pahikung textiles do appear in Kapunduk and Kanatang but probably as a result of marriage exchange with Pau and Rindi. It is likely that a lau pahikung hiamba collected in Kapunduk, just north of Waingapu, was made in Parai Yawang and sent to that region as part of a marriage counter-prestation (Khan Majlis 1991, 239).

Noblewomen dressed in lau pahikung displaying a trade cloth at the funeral of Tamu Umbu Nai Wolang, the Raja of Kapunduk, in 1988

In 1975 or 1976 a noblewoman from East Sumba apparently attempted to introduce the pahikung technique to weavers in the Loli district of West Sumba (Geirnaert 1989, 74). However it did not take hold. One of her pupils was a proficient weaver who, despite mastering the technique, felt that it was inappropriate to continue because she was a commoner and pahikung was the preserve of the nobility.

The disappearance of the pahikung technique from such a large geographical area to the south of Umalulu during the twentieth century is probably for other reasons - most likely the unwillingness of daughters to follow in their mother’s footsteps and master the technical intricacies involved.

Weavers in Umalulu

According to government figures collected in 2005, Kecamatan Umalulu was the most important district for weaving ikat in the whole of East Sumba, with over 500 people involved in the trade:

| Kecamatan | Units | Workers |

| Umalulu | 260 | 525 |

| Kota Waingapu | 78 | 457 |

| Pandawai | 200 | 400 |

| Rindi | 160 | 280 |

| Pahunga Lodu | 100 | 200 |

| Haharu | 80 | 160 |

| Kahaungu Eti | 20 | 43 |

| Nggaha Ori Angu | 7 | 7 |

| Karera | 1 | 4 |

| Lewa | - | - |

| Matawai La Pawu | - | - |

| Nggaha Ori Angu | - | - |

| Paberiwai | - | - |

| Pinu Pahar | - | - |

| Tabundung | - | - |

| East Sumba Total | 906 | 2,076 |

Source: Department of Trade and Industry, Central Bureau of Statistics, 2005

It is not clear whether these figures include weavers who weave pahikung but not ikat.

Either way, these figures are not correct and significantly understate the size of the weaving sector. For example, Kota Waingapu is by far the most important ikat producing region in East Sumba. In the single area of Kawangu there are well over 1,000 weavers producing ikat or the local market.

Likewise in Umalulu, there are well over 1,000 weavers of pahikung.

In Parai Yawang, Rindi, Tamu Umbu Makambombu emphasised to us the important difference between the weaving conducted in Rindi compared to Umalulu. In the past, 75% of the textiles produced in Rindi were hinggis while 25% were lau. Of the latter, 95% were lau hiamba while only 5% were lau pahikung hiamba. Today the proportion of lau is lower. Meanwhile in Umalulu, 90% of the textiles produced are lau pahikung while just 10% are hinggis.

Supplementary Warp

Supplementary warp is a technique in which the basic ground weave is supplemented by an extra set of warps. These partially float above and below the ground weave, while at the same time being partially interlaced with the ground weave. The technique is sometimes called extra warp patterning (Emery 1994, 144). However the use of the much broader term - warp float weaving - is not correct because there are many ways to produce a weave with a floating warp, such as in basket weave, twill, or warp-faced satin weave.

Supplementary warp is classified as a compound weave, in that the ground weave formed by the directionally differentiated sets of warps and wefts are compounded by more than one set of warps and/or wefts (Emery 1994, 140).

In Irene Emery’s opinion, supplementary warp cannot be as ‘spontaneous’ as supplementary weft because all of the supplementary warps must be in place on the loom before the commencement of weaving (1994, 144). This rules out the supplementary warp equivalent of discontinuous supplementary weft decoration. Of course supplementary warp can be used to produce a partially discontinuous pattern by allowing the extra warps to float freely on the reverse of the ground. However, Emery seems to have been unaware that a skilled weaver can introduce a discontinuous section of supplementary warp into a plain textile woven with just a ground warp and weft. This is achieved by weaving a section of supplementary warp and then cutting away the remaining unwoven supplementary warp threads.

A section of discontinuous pahikung inserted between two panels of warp ikat

In mainland Southeast Asia the supplementary warp technique is frequently used to weave narrow decorative warp bands with a simple repeat pattern. It is most closely associated with the T’ai- and Kadai-speaking peoples of southern China, Laos and Thailand. They include:

- the various Li groups on Hainan Island who are closely related to the T’ai

- the T’ai Daeng, T’ai Nuea, T’ai Moei, T’ai Khang, T’ai Dam, T’ai Khao and the Phuan in Laos (Cheesman 2004, 111; Gittinger and Lefferts 1992, 34; Gittinger 2004, 66; Tagwerker 2009, 114-115)

- the T’ai Yuan in Thailand (McIntosh 2012, 6)

- the T’ai Dam and the Cham in Vietnam (Howard 2008b). The Cham refer to the technique as bi ngu qua tan (to make a pattern with two layers).

Many of these groups have successfully migrated the technique from the back-tension loom to the frame loom. Surprisingly supplementary warp appears to be absent from Burma today (Howard 2005, 249).

The T’ai refer to the technique as muk, the term for the sticks that programme the supplementary warp design. Designs are described by the number of sticks required to weave that particular pattern, ranging from muk 3 and muk 4 up to muk 12 (Tagwerker 2009, 114). In Laos the T’ai Daeng and T’ai Khao use muk to weave the important hua buan waistbands attached to ceremonial tubeskirts.

It is the T’ai who were probably responsible for its spread westwards into Burma, Assam and Bhutan, and south-eastwards into Vietnam and eventually the Malay Archipelago (Howard 2008a). However supplementary warp originated as a back-tension loom technique and seems to have been abandoned by many T’ai communities as they adopted the more convenient frame loom.

Robyn Maxwell has suggested that the earliest weaving decoration used throughout Southeast Asia was warp-oriented. This encompassed warp banding and striping, warp ikat, complementary warp and supplementary warp (Maxwell 1990, 150-151). With increasing Indian influence from the fifth century AD onwards, and the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism, these techniques were progressively substituted by weft-oriented alternatives.

Bas-relief of a dancing apsara wearing a floral skirt cloth with weft-oriented end bands, Angkor Wat, Cambodia

This shift was encouraged by the introduction of silk, a much finer yarn that can only be woven on a loom with the help of a reed or comb to prevent the warps from tangling. This requires the warps to be threaded through the reed, and therefore makes it both extremely difficult to use a continuous warp and impossible to add a supplementary warp. This has reinforced the transition from warp ikat to weft ikat and from supplementary warp to supplementary weft. In the Malay Peninsula the influence of traders from China, India and Arabia, together with the silk and gold threads that they imported, led to the widespread adoption of songket - supplementary weft using a gold thread.

In Indonesia supplementary warp tends to have been used on just a few specialised textiles in a limited number of isolated areas. In Central Sulawesi it was infrequently used by the Toraja and in East Kalimantan by the Benuaq, but it seems to have died out during the nineteenth century in both locations (Maxwell 1990, 56). On Bali it was occasionally used to weave sacred textile lamak temple hangings (Maxwell 1990, 204; Hauser-Schaublin and Nabholz-Kartaschoff 1997, 7-8).

On Flores the technique was probably quite rare, and has now been lost. In the recent past it was only used by the Lio in Ende region to weave large ritual pundi shoulder bags for the mosalaki tana pu’u, and by the Lamaholot of East Flores to make mét waist belts. On Timor it is occasionally used to weave some decorative sotis warp bands, although most are woven in simpler complementary warp. Sotis is a rather vague term, poorly described in the literature, which covers all types of warp-float weaving (Yeager and Jacobsen 2002, 74). In Insana they combine complementary warp with two-colour supplementary warp to create four-coloured bands (Yeager and Jacobsen 2002, 72). In Lautem, East Timor, the Fataluku call the technique ter (Soares 2015, 12).

Throughout the whole of Indonesia, East Sumba has by far the richest and most complex tradition of supplementary warp weaving. The survival of this technique is probably because pre-colonial Sumba was historically more isolated than regions like Sumatra, Java and Bali, which were heavily influenced by Indian trade and culture. That this labour-intensive technique has been developed to such a highly sophisticated level on Sumba may be because of the island’s strict hierarchical social system, where a plentiful supply of slave labour was available to the island’s nobility.

The Term Pahikung

The term pahikung derives from hiku, meaning to thrust, jab or lever, or to do work with a needle. The addition of the ending -ngu or -ng produces the verb hikung, meaning to pick. Finally the addition of the causative prefix pa- turns the verb hikung into the noun pahikung, literally that which has been picked.

Complementary Warp

Supplementary warp is frequently confused with the complementary warp technique (sometimes referred to as alternate warp or alternating warp float). Complementary means combining in such a way as to enhance or emphasise the qualities of each other. In complementary warp weaving there are at least two sets of warps, which are complementary to each other and co-equal in the fabric structure (Emery 1994, 74).

In complementary warp weaving there is no supplementary warp, only the ground warps which are composed of yarns of two contrasting colours arranged alternately. When these are woven in normal warp-faced weave they produce a textile with bars of alternating colour. However if some of the warps of one colour are allowed to float over more than one weft, it is possible to weave a pattern. This can be done simply - by using a pick to select those warps that will float on the face of the textile. Alternatively the pattern can be pre-programmed by inserting short sticks into the unwoven warps. It is possible to achieve a bolder effect by choosing a coarser gauge yarn for one of the warp sets.

Complementary warp is used selectively in Indonesia. On Sumatra it is primarily used by the Toba Batak for adding stripes to the side panels of their ulos ragidup. On Flores it is used by both the Lio and Endenese to create narrow bands along the outer selvage edges of their lawo and zawo tubeskirts. On Timor the majority of sotis bands are woven in complementary warp (Yeager and Jacobsen 2002, 72; Coury 20014, 35). Sotis or foit complementary warp is common in East Timor, especially among the Fataluku-speakers of Lautem (Hamilton 2008, 42-44; Barrkman 2009, 12). It has also been found among the Timorese communities at Halerman and Kolana on Alor, and was used in the past on Kisar Island (whose textile culture has been heavily influenced by the Fataluku of Lautem).

On Savu the technique is used by weavers from the hubi ai moiety to make the raja warp stripes on èi raja tubeskirts.

Bands of complementary warp sotis on a tais runat at Teunbaun in Kupang Regency,

woven with a morinda weft and just three sticks to programme the black and white warps

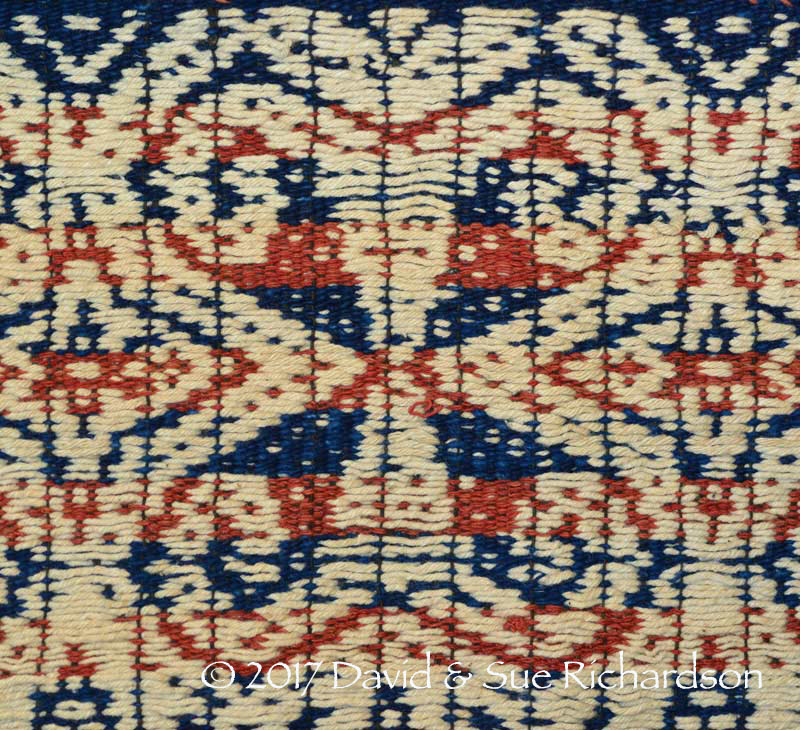

On Sumba Island complementary warp decoration is found in Kecamatan Kanatang, in the northern coastal region of East Sumba, from Ndapayami just north of Waingapu to Nahu and especially Desa Hamba Praing. It is locally known as pahitang. The same technique is also found to a lesser extent in Parai Yawang, Kecamatan Rindi, possibly as a result of the marriage of the daughters of noble Kanatang families to the sons of noble families in Rindi. As with supplementary warp, the complementary warp technique is taken to a higher degree of refinement on Sumba Island than elsewhere.

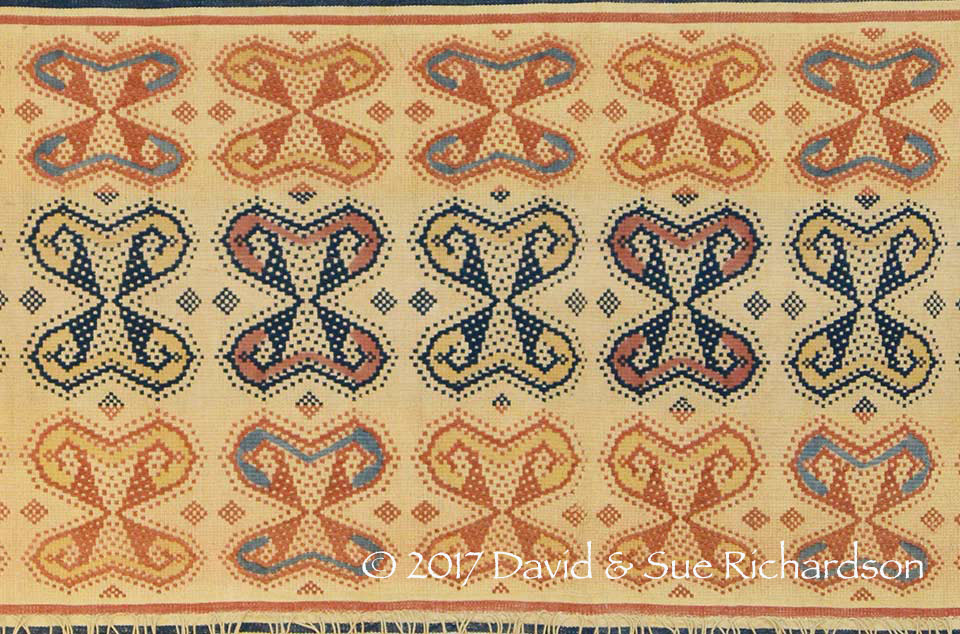

A ranggi kaworu pahitang from Kanatang, woven with wide pahitang side bands decorated with blue and white crayfish (kurangu). Richardson Collection

An elegant lau pahitang hiamba from Mondu, in Kecamatan Kanatang,

combining warp ikat and complementary warp. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

The Choice of Yarns

For the past half century the majority of pahikung has been woven using commercial machine-spun yarn. For the warp, which in the Kambera language is called the hiamba (sometimes written hemba), weavers use a fine 2-ply yarn. In the Kambera region this is called benang toko, but in the region of Pau they use the term bara ita, which seems to have no literal meaning. Bara ita or benang toko is the same commercial yarn that is used to make warp ikat.

In most cases the ground warp is dyed prior to weaving, preferably with either indigo or morinda. Occasionally weavers use alternating bands of indigo and morinda.

Pahikung weavers can use either a single or a double warp. In the latter case they simply place two skeins of cotton onto the swift (piyapak) and wind it into a ball (kabukul).

The supplementary warp or pahikung hiamba must be much thicker than the ground warp and is produced by plying several single yarns. In both Kambera and Pau these single yarns are called tawalah and are normally relatively coarse. In Pau the weavers have recently been using a coarse single Merak and Cendrawasih (Peacock and Bird of Paradise) brand cotton yarn with an English yarn count of 12 (12/S grade) purchased in 10lb bags from Bali.

A common choice for the supplementary warp is 4-ply (patu-puti), but some weavers use 6-ply and we have seen examples made using 10-ply and 12-ply. The verb paputi means to ply, spin or roll.

A 10lb bag of Merak and Cendrawasih (Peacock and Bird of Paradise) brand

12/S cotton yarn made in Bali

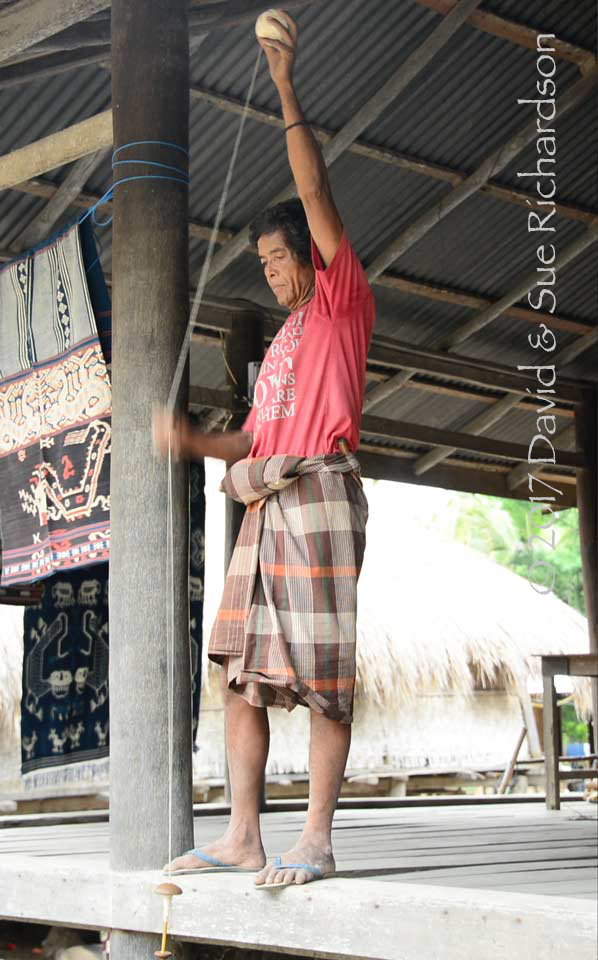

To produce a 4-ply yarn, four skeins of s-spun single commercial yarn are placed on a swift and rolled into a ball. The ends of the threads are attached to a drop spindle and are then spun in the counter-clockwise z-direction to produce a z4s plied yarn, which is then wound onto the shank of the spindle.

A man using a drop spindle to produce a 4-ply yarn at Uma Bara, Kecamatan Umalulu

The supplementary warp is generally used undyed. Colours can be added after the weaving has been completed – see the section on ndatta below. However in a few cases the supplementary warp is pre-dyed.

The finely-detailed panel on this mud-dyed lau pahikung paka kuamba has been woven with a morinda-dyed supplementary warp

The weft is called the pamawang. An unplied double weft is referred to as a big weft, pamawang bakul and a single weft is referred to as a small weft, pamawang kudu.

In the past, pahikung was woven using hand-spun yarn. This is very rarely the case today. Unfortunately unless the yarn is spun extremely finely, the results can look rather crude.

A coarsely woven karihu butterfly motif on a lau hiamba pahikung nggeri, executed in pahikung using hand-spun yarns and the pahudu rú kalu or banana leaf technique

Return to Top

Preparing the Warps

The first stage in weaving a pahikung textile is to prepare the warps. This is done on a simple warping-up frame, called a wungi pamening or pamening (wungi = frame). The ground warp and supplementary warp are wound at the same time, as is the heddle or wunang. The cotton warps are first wound into balls and placed in half coconut shells. Two women sit within the frame, side by side, and pass the coconut shells back and forth around the two end beams of the frame.

In the following images the women are using two balls of yarn to double their productivity.

They begin by winding a section of ground warp, forming a cross to separate the upper and lower sets of warps. The upper set passes under a bamboo pole that will be used to wind the heddle. They next wind a section of supplementary warp, which does not need to be separated into an upper or lower set, but is wound so that it lies below the bamboo pole used for forming the heddle. Next they lift and reposition each supplementary warp, one at a time, so that it sits on top of the ground warps. There is a fixed ratio of one white supplementary warp for every two ground warps.

We must emphasise that the supplementary warp does not incorporate a cross. It does not pass through the heddle and always sits above the ground warps - at least up to the point of weaving.

Beginning to wind the ground warp, passing the yarn under and over the

pair of brown battens to form the cross. Watu Panunggul, Umalulu

Moving the white supplementary warps on top of the blue ground warps

The heddle or wunang is formed simultaneously as the ground warp is wound. Today the heddle is made from fine strong nylon. As the upper warp is passed under the stout bamboo pole on which the heddle is wound, the nylon strand is looped over the bamboo and the warp passed through the loop.

The beginning of the nylon heddle

The process of warping up continues, with another section of ground warps, another section of supplementary warps, another section of heddle, and so on.

Once the warps have been wound they are transferred to the wungi pahikung, the frame for programming the pahikung design. If the warps are being prepared for making a two-panel skirt, their length is sufficient to weave both the upper and lower panel at the same time.

The Pahudu Pattern Guide

The patterns used in pahikung are not reproduced from memory but from a pattern guide known as a pahudu. The verb hudu means to land, to fish, or to catch in a dip net. The addition of the causative prefix pa- turns the verb into the noun pahudu - something that has undergone the action of hudu – in other words has been caught or retained.

The more descriptive term pahudu ri kalanda means a coconut leaf pattern guide, referring to the leaf ribs that were traditionally used to make the pahudu (Breguet 2013, 119).

A pahudu with a geometric design composed of around 144 supplementary warps

The pahudu consists of the full set of supplementary warps woven into the required pattern, substituting the cotton weft with the very fine ribs of palm leaves. These are described by the Indonesian word lidi. Today they are frequently substituted by strips of finely split bamboo. To make a pahudu the supplementary warps are first wound onto the wungi pahikung frame. The warps that float on the surface of the textile are raised using a bamboo pick, and the lidi sticks are inserted behind them in sequence. The pattern sides are kept in alignment by interlocking two warp yarns along each edge of the pattern. On completion the warps ends are knotted onto a stick to retain the integrity of the pattern.

A pair of morinda-dyed yarns constrains the pattern edge.

Comparison of the rampant crowned lion pattern on the pahudu and on the finished lau skirt. The pahudu rendition, based on 161 warps, is elongated because a lidi stick takes up more space than a beaten-in weft

To maintain the integrity of the textile it is common to design patterns so that each supplementary warp only floats over two or three wefts on the face of the textile and is staggered from its neighbour by one weft. This facilitates angular designs and produces patterns with diagonal ribbing.

The advantages of the pahudu are that:

- it is a permanent record of a woman’s intellectual property

- it can be rolled up and securely stored in the roof of the house until required

- it can be used over and over again

- a mother can pass on her library of pahudu to her daughter so that her designs and those of her ancestors will continue to be used down the generations.

As a consequence pahudu – especially those recording elaborate patterns – are highly valued and jealously guarded (Forshee 2001, 96 and 190). The royal cousins from the domain of Umalulu, Tamu Rambu Pakki and Tamu Rambu Tokung, have recorded on video how one of their pahudus was stolen and was eventually returned (Hamilton and Forshee 2010).

A more complex pahudu composed of about 200 lidi sticks

Weavers will go to great lengths to ensure that one of their lau pahikung with a valuable pattern does not fall into the hands of another weaver who will use it to make a replica pahudu.

Because pahudu are passed down from generation to generation, some perpetuate pahikung patterns that may have been designed a century or more ago. Some may be even older – even if a pahudu deteriorates through repeated use it can easily be copied to make a new one. The dependence of pahikung on the pahudu system probably means that some designs and motifs have been preserved for a long time. However we need to be sceptical about claims that lau pahikung might provide a source of information about the appearance of textiles in the pre-colonial period – in other words before the arrival of the Portuguese in 1515 (Holmgren and Spertus 1989, 36). Many textile scholars fall into the trap of assuming that textile designs are time invariant when in fact they often represent fashion and therefore are always changing in some way or another.

Consider for example one of the lau pahikung in the Tropenmuseum Collection, collected by a Dutch missionary in the first half of the nineteenth century. Despite having no provenance it is thought to be an early type, woven with a far more refined decoration than that found on later examples (Hout 2001, 99). Interestingly only the narrow decorative bands were woven in pahikung, the two wide bands having been woven in complementary warp.

Early nineteenth century lau pahikung, acquired in 1951 by the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

A similar design on an old skirt fragment collected before 1960

(Image courtesy of the Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen Foundation)

Return to Top

Programming the Supplementary Warps

The complete warp set is transferred to the wungi pahikung frame and placed under tension. The frame is set in a semi-vertical position and the weaver sits in front on the floor with the pahudu pattern in her lap. The weaver counts off each line of the pattern, using a long bamboo pick to lift the appropriate supplementary yarns and insert a new lidi pattern stick behind them. She progressively programmes the pahikung design by transferring the pattern from the pahudu to the supplementary warps on the frame, inserting a complete set of new lidi sticks. On the loom, each pattern stick will determine which supplementary warp yarns float above or below the ground weave for each throw of the weft.

With the pahudu on her lap and all the supplementary warps lying above the ground warps, the weaver starts from the heddle upwards, inserting her pick to collect all of the upper warps on that row before replacing it with a new lidi stick

The pattern is progressively transferred to the supplementary warps, lidi by lidi

To make a lau pahikung tubeskirt, decorated with a main band and a secondary band of pahikung, the main band is programmed first using very long lidi sticks. Then the secondary band is programmed, and as each row of upper supplementary warps is collected on the pick the long lidi is slid across to replace it.

Programming the main and secondary bands of supplementary warp

Return to Top

The Pahikung Loom

The East Sumba back-tension loom is called a kambatinung in the Kambera language, kamba meaning cotton and tinung meaning to weave. The continuous warp is stretched between the back or warp beam, and the breast beam - the latter tensioned by a second beam with a back rest that sits in the small of the weaver’s back. To weave pahikung the loom is slightly inclined from the horizontal and is fitted with two heddles – the first for the odd ground warps and the second for the even ground warps. Other details of the loom arrangement tend to vary from weaver to weaver.

Weaving under the house at Uma Bara

Two pahikung weavers carved onto a grave stone at Uma Bara, Kecamatan Umalulu

The following pahikung weaving demonstration at Pau, overseen by Tamu Rambu Pakki, shows a typical loom setup. The ground warps and the supplementary warps are tightly wound around two bamboo laths (lira) at the far right hand side of the photograph, next to the warp beam, keeping them in exact register. One bamboo pole, the kalira palambang or shed stick, separates the odd and even ground warps and a second supports the supplementary warps so that they remain above the ground warps.

Ibu Reni working on the lower panel of a lau pahikung at Watu Panunggul

The unwoven part of the pattern, pre-programmed with the numerous lidi sticks, is stored at the back of the loom. It is separated from the shed, held open with the upright sword, and the two heddles. To weave the next line of the pattern the weaver pulls the first lidi towards her and then slides the tip of a thin bamboo lathe along the top of the lidi so that it passes under the upper set of supplementary warps. She removes the lidi and uses the batten to lift the supplementary warps. If she is using heddle 2, she can lift it and insert her sword below the raised ground and supplementary warps before passing the shuttle.

If she is using heddle 1, she inserts a second lathe under the raised supplementary warps between heddle 2 and heddle 1, effectively transferring the pattern forward across heddle 2. She then pulls that lathe forward up to heddle 1, and places a third lathe under the raised supplementary warps in front of heddle 1 before pulling it further forward up to the stretcher. She now raises heddle 1 to create the shed.

When raising either heddle, it is lifted high so that the lower supplementary warps drop down well below the upper sets of supplementary and ground warps.

A lathe raises the upper supplementary warps, while heddle 2 forms a shed in the ground warps

The weaver can now pass the shuttle carrying the weft through the shed and then beat it into the warps with the sword, known as a kalira or kalira hanjil.

Passing the weft, which is wound on a long stick with bulbous ends

When weaving pahikung the ground warps interlace with every weft, and therefore need to be longer than the supplementary warps which partially float above and below the wefts. This means that the tension in the supplementary warps decreases as the weaving progresses. To make matters worse, the supplementary warp is more elastic than the ground warp because it is formed from several single threads plied together. The more lidi are inserted between the supplementary warps, the more they stretch. To produce a balanced textile it is vital that this decrease in tension is constantly countered. This is achieved by inserting one or more sticks into a loop in the supplementary warps. As the weaving continues, further sticks are progressively inserted, the loop being expanding using the point of a batten.

As the weaving progresses, the bundle of sticks taking up the slack in the supplementary warps gets bigger and bigger

The continuous warp is always longer that the length of cloth required. As the weaving continues, the length of the unwoven warps becomes shorter and shorter until there is no longer sufficient space to form a shed and pass the shuttle. At this point the cloth is removed from the loom and cut. If it is to be made into a tubeskirt, the cloth is cut into separate panels and the unwoven warps are discarded. If the pahikung has been woven to embellish a hinggi, the unwoven warps will form the fringes at each end.

Basic Pahikung

In basic pahikung the supplementary warps that form the pattern by floating above the ground weave usually only cross two or three wefts before being interlaced with a weft and passing through to the underside of the textile. There they may float over a few or many wefts before being brought back onto the upper surface of the textile. In the finished textile the underside has many free floating supplementary warp yarns. This is a problem if the textile is to be used as a garment such as a tubeskirt as they can get tangled in a foot and in time get broken.

The reverse side of a section of basic pahikung with hanging supplementary warps

Even in basic pahikung the quality of the weaving tends to be high. The warp-faced weave is always tight, even the simplest patterns remain intricate, and there are no loose or misplaced warp or weft yarns.

Luar Dalam Pahikung

The finest pahikung is woven with two separate wefts, the secondary weft interlacing with the floating warps on the underside of the textile and thereby incorporating them into the structure of the textile. This pahikung technique is called luar dalam, meaning outside-inside. In other words, the quality of the inside/underside of the skirt cloth is the same as that of the outside/upperside.

The extra second weft is called the tiama, meaning lifting, and is normally inserted using a second shuttle after a predetermined number of primary wefts have been passed. The more frequently the second weft is inserted, the higher the quality of the pahikung.

To insert the second weft the weaver withdraws the sword from the normal shed and then slides it back under the lower set of supplementary warps to create a new shed with just the lower ground warps at the bottom. She then passes the second shuttle and positions the extra weft. Unlike the primary wefts, the secondary wefts are not beaten in with the sword.

A weaver holds her main shuttle in her right hand while her secondary shuttle is placed on the mat beside her

Obviously this type of pahikung is more laborious to produce because it involves an additional stage in an already complex weaving cycle.

Underside section of simple luar dalam pahikung, illustrating how the second weft interlaces with the supplementary warps after every twenty primary wefts

The same section on the front side of the textile

Detail of high quality luar dalam pahikung, illustrating how the second weft interlaces with the supplementary warps on the underside of the textile after each second primary weft

The same section on the front side of the textile

In the finest pahikung, the supplementary warps on the face of the textile only float across two wefts, creating a much more detailed pattern.

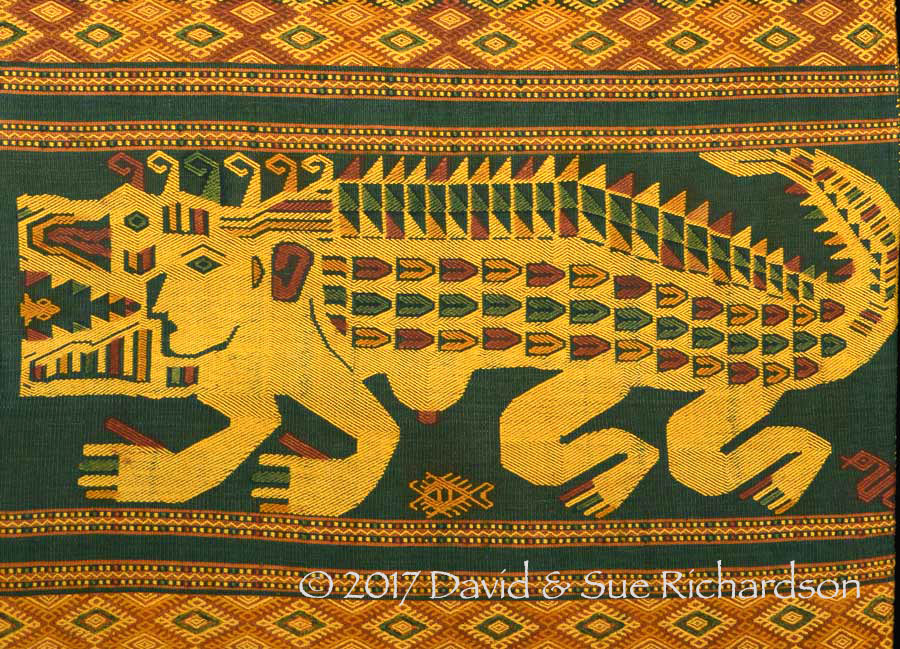

Very finely woven crocodile (wuya) motif on a lau pahikung made by Rambu Ngana Harakay, the best pahikung weaver of her generation in the whole of East Sumba

Return to Top

Pahudu Rú Kalu

Some pahikung is woven using what appears to be a double supplementary warp. The pahudu pattern guide is simply designed so that two adjacent warps follow one another exactly in parallel.

This technique is called pahudu rú kalu, meaning leaf (rú) of banana (kalu) pahudu or pahikung. It tends to produce a simpler style of supplementary warp, more suited to more elementary patterns, especially those that are symmetrical.

The butterfly (karihu) motif executed in the pahudu rú kalu technique using entirely hand-spun yarns

The reverse side of the same motif

The pahudu for the butterfly motif executed in pahudu rú kalu.

Property of Tamu Rambu Hamu Eti, Parai Yawang, the wife of the Raja of Rindi

The same butterfly motif executed in the pahudu rú kalu technique using commercial yarns

Pa Ji Mbualang Pahikung

A closely related technique to pahudu rú kalu is known as pa ji mbualang or basket weaving, the word mbualang meaning basket. This form of pahikung also uses a double supplementary warp, but in this case the warps only ever float over two wefts and each pair of matching warps is staggered from the neighbouring pair by one weft. It creates a herringbone-like textile structure, somewhat similar to a twill weave.

The pa ji mbualang technique is one of the easiest forms of pahikung, yet weavers in Pau guard it very jealously and are reluctant to allow it to be seen by other weavers.

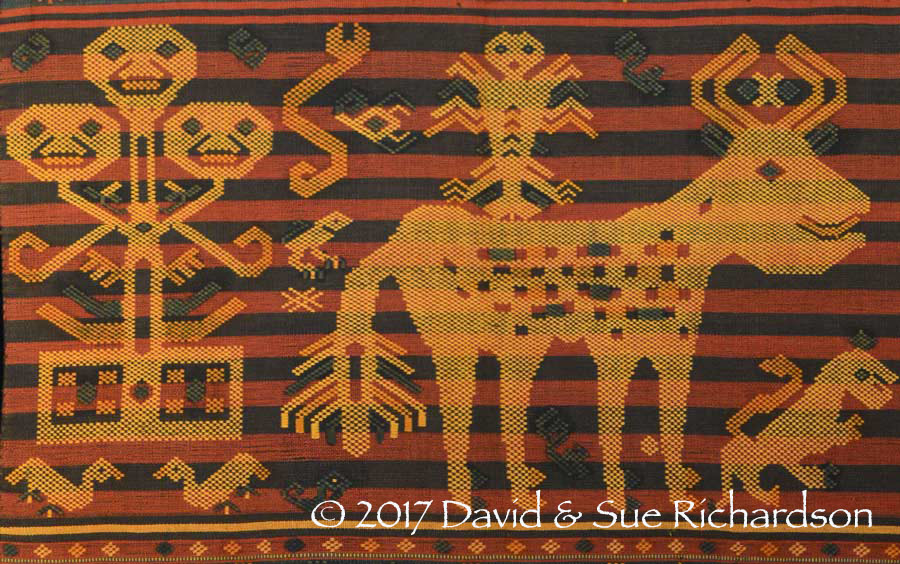

A complex pictorial pattern woven in pa ji mbualang technique on an old lau pahikung hiamba made in Lairuru, Kecamatan Umalulu

An octopus motif woven in pa ji mbualang technique at Watu Panunggul on a new lau pahikung

We have encountered a similar technique called paworu la kamba tinung, which we still need to investigate.

Return to Top

Tinu Pata Pahikung

Many classical two-panel lau pahikung hiamba are designed with a decorative band of pahikung on the lower panel and a much simpler band of pahikung on the upper panel. The latter is woven in the tinu pata (literally weaving broken) technique. The verb tinung means to weave while pata means break.

All of the supplementary warps follow each other exactly in parallel. In a typical example, they float over two wefts before passing under the third weft and then float over the next two wefts before passing under the sixth, and so on. This produces a band of parallel bars of alternating colour, occasionally broken by a simple motif.

A section of tinu patu in the upper panel of a lau pahikung hiamba

Return to Top

Ndatta

Pahikung can only be woven using supplementary warps that are all the same colour, or else are arranged in bands of the same colour. Most commonly they are used undyed, but sometimes they are dyed with either indigo or morinda.

To embellish the pahikung pattern with additional colours it is necessary to paint them onto the finished article using a brush. Traditionally they were hand-coloured with a small coconut fibre brush, called a pendatta, although today it is common to use a plastic toothbrush with some of the fibres removed from the brush head. The technique itself is called ndatta. It is not undertaken by the original weaver but is passed to a specialist who uses his or her own judgement on how to colour the cloth. Good quality pahikung cloth is coloured with natural dyes such as indigo, morinda and yellow kayu kuning. Cheaper work is coloured with synthetic dyes.

Two toothbrushes used to paint morinda – the upper one for large areas and the lower one with most of the bristles removed for detailing

A young girl is tasked with colouring pahikung sashes with synthetic dyes for the Balinese tourist market

The same specialists will also embellish hinggi kombu with a third colour, normally yellow kayu kuning, to contrast with the blue indigo and red morinda. Noteboom reported that cloths that had been processed with yellow were intended for the nobility (Noteboom 1940, 88). Adams rather rashly speculated that the painting of blankets was ‘tantamount to gilding’, because according to oral legends, prized cloths had been gilded (Adams 1969, 88).

Tubeskirts and blankets that have been coloured in this way are sometimes referred to as lau pendatta or hinggi pendatta. Some pahikung textiles are given a final colourwash using a solution of tobacco water or tea. This takes away the harshness of the white undyed supplementary warps.

A similar painting technique is used in other parts of Southeast Asia, frequently as a shortcut for adding a second colour to weft ikat.

A young girl using a stick to add chemical blue details to ikatted silk wefts at Prey Chung Kran, Kampong Cham, Cambodia

The same technique is also employed in a reverse ikat process, termed cetak by Sylvia Fraser-Lu (Fraser-Lu 1988, 45, 91). Cetak is an Indonesian word meaning ‘print’. Here the fine details are dyed first and the ground colour is dyed last. The bundles of yarns are bound with the outline of the required motif and the dye is carefully spooned or painted inside the enclosed outline. Once the dye has dried, the motifs are bound over to protect them from subsequent dyeing. This process is repeated for all but the ground colour. Once all of the minor colours have been applied and sealed, the wefts are completely immersed into the dye bath containing the ground colour.

In Indonesia commercial producers of weft ikat have frequently employed it to improve productivity. Examples include workshops in Troso, Central Java, endek producers around Gianyar on Bali, weaving factories at Cakranegara on Lombok, and commercial silk weavers at Sengkang in South Sulawesi (Fraser-Lu 1988, 183, 185, 189, 194).

In Burma it has been used for making cotton weft ikat si longyis at the villages of San Khan and Thapye Auk on the Dudawadi River close to Mandalay and at the weft ikat silk-weaving village of In Paw Khon on Inle Lake, Shan State (Fraser-Lu 1988, 46, 91 and 97).

Bibliography

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1969. System and Meaning in East Sumba Textile Design: A Study in Traditional Indonesian Art, Cultural Report Series 16, Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Adams, Marie Jeanne; Forshee, Jill; Djajasoebrata, Alit; and Hansen, Linda, 1999. Decorative Arts of Sumba, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam.

Bolland, Rita, 1956. 'Weaving a Sumba Woman’s Skirt', in Royal Tropical Institute Bulletin, vol. 119, pp. 49–56, Amsterdam.

Bolland, Rita, 1979. Demonstration of Three Looms, Irene Emery Roundtable on Museum Textiles: 1977 Proceedings, pp. 69-70, The Textile Museum, Washington D.C.

Breguet, George, 2006. The Life and Death of Tamu Rambu Yuliana: Princess of Sumba, Arts & Cultures, no. 7, pp. 200–233, Musée Barbier-Mueller, Genève.

Breguet, George, 2013. Three Lau Pahudu Skirts from Sumba: Ceremonial Dress or Currency?, Arts & Cultures, no. 14, pp. 116–129, Musée Barbier-Mueller, Genève.

Carol, Charles, 2004. Interpreting Social Change and Changing Production Through Examinations of Textiles of Xam Nuea and Surin, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 480.

Dammerman, Karel Willem, 1926. Een tocht naar Soemba, Natuurkundig Tijdshrift voor NederlandschIndisch, LXXXVI, reprinted by Indisch Comite uoor Wetenschappelijke Onderzoekingen, Batavia.

Emery, Irene, 2009. The Primary Structures of Fabrics: An Illustrated Classification, Thames and Hudson, London.

Forshee, Jill Kathryn, 1996. Powerful Connections: Cloth, Identity and Global Links in East Sumba, Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Forshee, Jill, 2001. Between the Folds: stories of cloth, lives, and travels from Sumba, University of Hawai‘i Press, Hawai’i.

Forth, Gregory L., 1981. Rindi: an Ethnographic Study of a Traditional Domain in Eastern Sumba, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Guelton, Marie-Hélène, 2004. ‘Use of the Pahudu String Model, Lau Pahudu Weaving from East Sumba, Indonesia’, in Through the Thread of Time, Southeast Asian Textiles: The James H. W. Thompson Foundation Symposium Papers, Jane Puranananda (ed.), pp. 47–65, The James H. W. Thompson Foundation, Bangkok.

Hamilton, Roy W., and Forshee, Jill, 2010. Weavers' Stories: Rambu Pakki and Rambu Tokung, video, The Fowler Museum, UCLA, Los Angeles, http://www.fowler.ucla.edu/videos/weavers-stories-sumba

Hout, Itie van, 2001. Lau Pahudu: Women’s Skirts from East Sumba, HALI, vol. 115, pp. 99-105.

Howard, Michael, 2008a. A World Between the Warps: Southeast Asia’s Supplementary Warp Textiles, White Lotus Press, Bangkok.

Howard, Michael, 2008b. Supplementary Warp Patterned Textiles of the Cham in Vietnam, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, paper 243.

Kate, F. C. ten, 1894. Soemba, Verslag eener reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesië, part III, Tijdschrift Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2nd series, vol. XI, pp. 541-638, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1923. Iets over Soemba en de Soembaweefsels, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 7, issue 10, pp. 295-313.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1927. Eenige Voorbeelden van het Ornament op de Weefsels van Soemba, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 11, issue 9, pp. 259-288.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. K. H. de, 1890. Eenige Mededeelingen over Soemba, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIII, pp. 565-595.

Witcamp, H., 1913. Een verkenningstocht over het eiland Soemba, II, IV, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, second series, 29, pp. 8-27, 619-637.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 4 March 2017.