Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Ternate Island

The Oral History of Uma Pura

The Islamisation of Alor and Ternate

A Brief Colonial History of West Alor

Uma Pura Textiles

Uma Pura Natural Dyes

Marine Dyes

Vegetable Dyes

Bibliography

Introduction

On tiny Ternate Island dyeing and weaving only takes place in the village of Uma Pura, home to its only Muslim community. Curiously the other four villages on Ternate, which are all Christian, have no tradition of weaving. This may be because in this region of the Pantar Strait the introduction of weaving was closely linked to the introduction of Islam, which probably occurred in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century (see Wellfelt 2014, 7-8).

The small village of Uma Pura on Ternate Island

For many years we had naively assumed that most of the textiles produced on Ternate were synthetically dyed. When we finally visited the island for the first time in May 2018 it was a revelation to discover that while a few of their textiles were indeed chemically dyed, the majority were naturally dyed in an extraordinarily wide range of colours.

It is ironic that this miniscule island with its scarce resources should produce more natural dyes than any other region of eastern Indonesia. This can only be put down to the creativity and resourcefulness of its people.

We were so impressed with our discoveries that we returned to visit the island’s weavers in the following October to investigate the dyeing processes in more detail. This webpage summarises our findings so far. It will be updated as we gather more information in the future.

Return to Top

Ternate Island

Ternate is one of five small islands, volcanic in origin, located in the Pantar Strait separating Pantar Island from Alor Island. The others are Kisu (locally known as Buaya or Crocodile Island), Pura, Kepa and Treweng. Pristine seas, rich in marine life, surround them all, making this region one of the premier diving sites in eastern Indonesia.

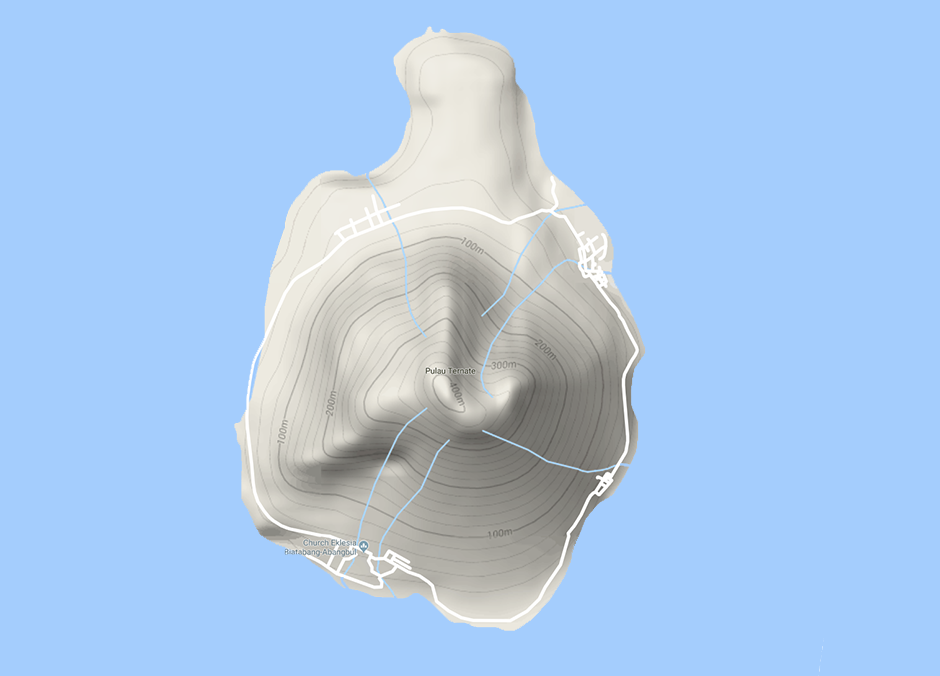

Ternate is only 2km wide and just under 3km from north to south. Administratively it is divided into two Desa within Kecamatan Alor Barat Laut (Northwest Alor District), one of the seventeen Kecamatan or districts that make up Kabupaten Alor (Alor Regency). The district administration is based in Alor Kecil.

The location of Ternate Island, highlighted in green

Ternate is conical in shape, reaching a height of just over 400 metres. Its slopes are unstable and are strewn with rocks and boulders. It shares its name with the much larger island of Ternate in Maluku, which has a similar conical shape. This is not coincidental. When Muslim clerics from Ternate, Maluku, brought Islam to west Alor in the late sixteenth or seventeenth century they saw that this tiny island in the Pantar Strait had the same shape as their own much larger island and renamed it accordingly.

The north side of Ternate as seen from Buaya Island

The south side of Ternate, with Biatabang on the far left and Uma Pura on the far right

There are five coastal settlements on the island, Biatabang and Uma Pura being the largest. Today the two adjacent hamlets of Bogakele and Kota Abang are essentially one, having gradually merged together over time. Biatabang, Bogakele, Kota Abang and Abangbol are Protestant, while Uma Pura is Moslem. Biatabang and Bogakele each have churches while Uma Pura has a mosque. Some of the Christians on the island still speak Reta or Retta, a little studied minority Papuan language.

The simple topography of Ternate (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

The five settlements on Ternate (Image courtesy of Google Earth)

Since 1999 Ternate has been subdivided into two desa:

- Ternate, composed of Uma Pura and Kota Abang, and

- Ternate Selatan (South Ternate), composed of Biatabang, Abangbul and Bogakele.

This partition was chosen deliberately to create two entities with roughly the same area and population without creating one Muslim desa and one Christian desa. Desa Ternate is further divided into dusun 1, the coastal part of Uma Pura, and dusun 2, the upper part of Uma Pura and Kota Abang. The population of Ternate was 1,887 in 2016 - 1,043 in Ternate and 844 in Ternate Selatan (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor, 2017, 15).

On Ternate, only the women of Uma Pura produce textiles. The villagers are poor and survive on a diet of fish and vegetables, especially maize. Although they raise goats and chickens, meat-eating is mainly restricted to ceremonial feasts. In the dry season, from April to October, the men go off far and wide in small boats, diving for sea cucumbers (trepang) and mother of pearl (Wellfelt 2007, 6). Others catch fish offshore using bamboo fish traps (bubu). The women collect shellfish and engage in weaving, selling or bartering their cloth on Alor and Pantar. Many take their weavings to a weekly early morning market on the mainland close to Alor Besar.

Local fishing boats on the beach at Uma Pura with Alor in the distance

Fishing is constrained during the wet season and the focus turns to agriculture. In the past the villagers farmed the sides of their mountain but today this is prohibited because of the risk of erosion and landslides (Wellfelt 2007, 6). In 1966 they were allocated farmland at Sebajar on the mainland opposite Ternate Island. In November many villagers move to the mainland to prepare their allocated plots, planting maize, cassava and dry hill rice.

The people of Uma Pura speak a dialect of Alorese, an Austronesian language closely related to Lamaholot.

Return to Top

The Oral History of Uma Pura

The creation myth and oral history of the people of Uma Pura has been collected from the clan elders by Emilie Wellfelt (2007, 39-40). It is a rather incredible, garbled and disjointed tale.

The villagers believe the first humans originated from a place called Watu Meang (Red Stone) on the west side of neighbouring Pura Island. The first man, Kalipang, emerged from a bamboo stalk while his wife, Watu Meang, emerged from a stone on Red Mountain. Their descendants thrived until the menfolk suffered a disaster at sea, only one man, Muko Tahakang, surviving. To seek help for the starving women and children he paddled his canoe to the village of Kulong to ask for food.

It was a time of war between East Pura and West Pura and the latter sought assistance from the Raja of Alor Besar. Before his help was forthcoming, West Pura spontaneously attacked East Pura and incinerated its leader’s village. The Raja was angered at not being consulted and as punishment kidnapped the inhabitants of Watu Meang, including Muko Tahakang, and brought them to Alor Besar. There they built houses and adopted Islam. The son of Muko Tahakang became a loyal warrior to the Raja of Alor Besar.

At Alor Besar, the exiled community of Watu Meang maintained their self-respect – every time their leader ate or drank they struck a gong. After enquiring about the noise the Raja was told that the gong was rung to announce that a man, so poor that he could only eat maize, was having a meal. The Raja renamed him Wata Kamang (‘maize peel’) and to rid himself of the annoyance relocated the whole community to Sebanjar. However it was inhabited by people with a habit of excessive feasting and the local food resources were soon exhausted.

Wata Kamang decided to take his people to Pantar, but instead they settled on the island of Nuha Being (Big Island), which would later be renamed Ternate. Wata Kamang eventually had three sons. In time, they became the founders of three lineages: Uma Kakang (the house of the oldest brother); Uma Tukang (the house of the middle brother); and Uma Aring (the house of the youngest brother).

A fourth clan called Leing Papa was formed by a family who had been enslaved by Uma Kakang as a punishment for breaking one of their knives on the Alor mainland. A fifth clan, Deng Wahi, was founded by two brothers from Sebanjar who had accidentally set fire to a field owned by the Raja of Alor Besar and as punishment had been fined 30 bronze moko drums. Unable to pay the fine they were invited to come to Nuha Being and take on the role of guards.

Today these five clans form one of two exogamous groups or moieties at Uma Pura.

The second exogamous moiety consists of three clans and was formed by the descendants of the three sisters of the three founding brothers. Each sister married a man from off the island. Lipanggali, the first daughter, married Liku Amang and their descendants became members of the clan Filu Walu Lolong (Upper Filu Walu). Buiresang, the second daughter, married Liang Amang and their offspring formed the clan Biatabang. Finally Saleh, the third daughter, married Jon Being and gave rise to the clan Filu Walu Lang (Lower Filu Walu).

Return to Top

The Islamisation of Alor and Ternate

Linguistic research suggests that during or before the fourteenth century, Lamaholot-speaking Austronesian immigrants from Lembata (possibly Kedang), settled in small enclaves along the north coast of Pantar, especially at Pandai and Munaseli on the northernmost cape of Tanjung Muna, the location of the mythical kingdom of Munaseli (Klamer 2012, 102). Legends describe a war in which Munaseli was conquered and its people were dispersed. At least one group fled from Pantar in the early fifteenth century to settle at Alor Besar on the opposite side of the Pantar Strait. Legends say that that their leader Tulimau Wolang settled after defeating the local leader Bunga Bara (Gomang 1993, 29). He then married local women to form a mixed community. One local clan, Lallang Kisu, was formed by people from Ternate and Blagar on Pantar. Some groups from Munaseli may have continued as far as eastern Kolana (Rodemeier 2006, 69). Others may have settled at Kedang and Hadekewa in Waienga Bay on Lembata (Barnes 2001, 279).

Eventually Alor Besar and Kui on the west and southwest coasts of Alor formed an alliance of brotherhood with the enclaves of Pandai, Baranusa, and Bakalang on Pantar Island named Galiyao Watan Lema – the five shores of Galiyao – with Pandai at its head. A similar alliance – the Solor Watan Lema – was formed at some time prior to 1590 in the nearby Solor Archipelago, encompassing Lohayong and Lamakéra on Solor, Lamahala and Terong on Adonara, and Labala on Lembata (Dietrich 1983, 54, cited by Barnes 2001). The formation of both of these alliances may have been driven by a desire to rationalise or abolish the bridewealth demands required for intermarriage between these neighbouring communities (Gomang 1993, 39, 88-89; Rodemeier 1995, 439).

Different legends suggest that Islam was brought to Alor, Pandai and Baranusa by five missionaries who sailed from Ternate on board the sailboat Tuma Ninah. They were all brothers and were called Iang Gogo, Kima Gogo, Karim Gogo, Sulaiman Gogo and Yunus Gogo.

Iang Gogo settled at Alor Besar on the west coast of Alor, Kima Gogo at Lerabaing on southern Alor, Karim Gogo on Ternate Island, Sulaiman Gogo at Pandai on northernmost Pantar and Yunus Gogo at Baranusa on western Pantar (Firmansyah 27.01.17).

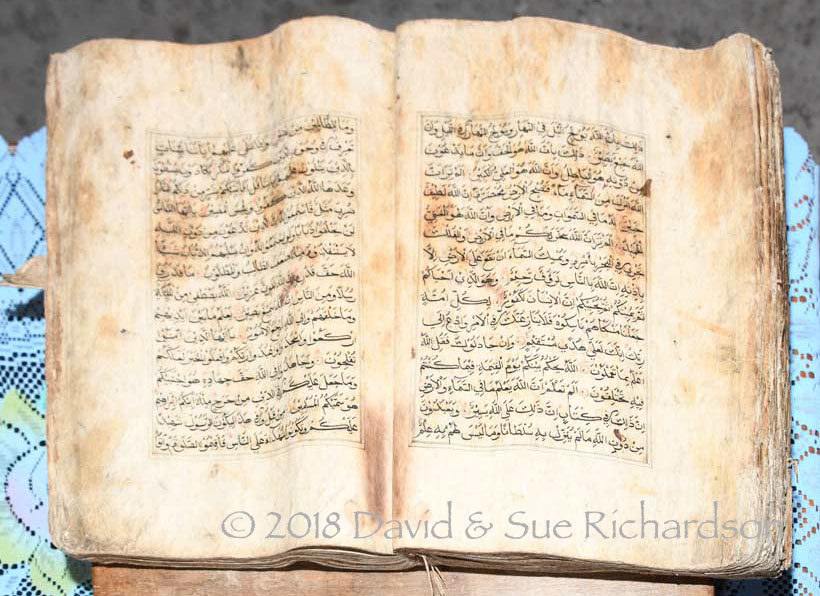

These stories are supported by the existence of a circumcision knife and an old Arabic Quran, handwritten on bark paper, that are preserved in a house next to the Babussholah mosque in Alor Besar. They are claimed to have been brought to Alor by Iang Gogo. The Quran appears to have been written in the Arabian Peninsula and was already old before it was brought to Alor.

The Holy Quran on its wooden container at Alor Besar

When exactly Islam arrived in the Pantar Strait is difficult to say. Nurdin Gogo, the current custodian of the Quran claims it arrived in 1518 or 1519. Although the last Kolano of Ternate in Maluku seems to have adopted Islam before the end of his reign in 1486, this date seems far too early for the spread of Islam to distant Alor, 1,000km to its south (Pires 1944, 213; Jacobs 1971, 83; First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1993, 727).

Local legends suggest that Islam arrived much later, some 14 to 17 generations ago, which would roughly place its arrival between 1600 and 1700 (Rodemeier 2010, 28). A later date seems more likely, especially because the promulgation of Islam by the Sultanate of Ternate seems to have been motivated by the assassination of Sultan Khairun in 1570 on the orders of the local Portuguese captain (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 19; Subrahmanyam 2012, 144). His son, Sultan Babullah, responded by driving the Portuguese from the island, enhancing his status in the process. This then led to an increased effort to spread Islam more widely throughout Maluku and beyond, extending as far as some of the coastal kingdoms of Sulawesi. It is probable that the missionaries sent to the coastal settlements of Galiyao Watan Lema arrived at this later stage as opposed to a century earlier.

Interestingly G. A. M. van Galen, who was the Controleur of Alor in 1946, mentioned that Islam first arrived from the Solor Islands and Ende, suggesting that there may have been more than one mission to convert the local population.

Eventually the two alliances of Galiyao Watan Lema and Solor Watan Lema formed a coalition known as the Sepulu Pandai or Ten Shores (Gomang 1993, 88-89; Hägerdal 2012, 38). It was apparently sealed by a vow of brotherhood (bela baja or big oath) and the drinking of blood mixed in arak. Henceforth any conflict between the two alliances would end in calamity (Barnes 2001, 278-279). Gomang suggests the motivation was to form an axis of coastal Muslims (known locally as the Paji) to wage war against the Demon, local inland or ‘mountain’ people and the Portuguese Catholics (Gomang 2006, 485).

The Sepulu Pandai continued until 1820 when it disintegrated as a result of internal differences (Hägerdal 2012, 38 and 245 note 95).

Masjid Al Muanshar, Uma Pura, Ternate Island

Return to Top

A Brief Colonial History of West Alor

Even in the sixteenth century, the villages of Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong in west Alor were completely independent of each other, each governed by a headman or Atabeng, supported by a Kapitan (Van Galen 1946). It seems that Ternate was effectively a satellite of Alor Besar.

Following the establishment of a fort on Solor Island in 1562, the Alor region came under the influence of the Portuguese, who appear to have made treaties with some of the local rulers in western Alor (Klamer 2010, 14). When the Dutch entered the region in the early 1600s, the Galiyao Watan Lema was still nominally allied to Portugal and remained so for a further two centuries.

In 1851 José Lopes de Lima, the Portuguese Governor of cash-strapped Dili, reached an informal agreement with the Dutch Governor of Kupang, Baron von Lynden. In return for a payment of 200,000 florins, the Portuguese would cede Flores, Solor, Adonara, Lembata, Pantar and Alor to the Dutch, while the Dutch would cede the enclave of Oecussi and Maubara on Timor along with Atauru Island to the Portuguese (de Sousa Saidanha 1994, 38-39). The Dutch quickly established a presence, installing the posthouder Johan Hendrik van Nimwegen at the port of Alor Kecil in 1852 (Almanak van Nederlandsch-Indië 1852).

Following the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon in 1859, Alor formally became a Dutch colony. One year later the Dutch established a small military post on Alor headed by a Lieutenant Pelt, aimed at controlling the slave trade (Dalen 1928, 159). Alor was divided into four, and then later six, zelfbesturende landschappen – Alor, Kui, Bataru, Pureman, Batulolong and Kolana (Van Galen 2010, 20). However, in the case of Alor - effectively the three villages of Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong - the Dutch had no desire to deal with three separate Atabengs. Around 1860 an agreement was reached in which Baololong, the Atabeng of Alor Besar, would become the first Raja of Alor. Dulolong accepted this decision because Baololong was married to a sister of its Atabeng, while Alor Kecil concurred because it saw itself as the younger sibling of Dulolong (Van Galen 1946).

The Dutch initially followed a hands-off policy of self-rule, hoping that the coastal Rajas would exert their authority over the inland mountain people. Faced with numerous insurrections throughout the archipelago it became obvious by the turn of the century that a more interventionist policy was required. In the eastern islands, the first visible sign of this change in policy was the deposing of the raja of Larantuka in 1904. The Dutch did not focus their attention onto Alor until 1910, where a new posthouder, Meulemans, had just been installed at Alor Kecil. Raja Baololong had earlier been succeeded by his son Tulimau II who, following his death in 1902, had been replaced by his relative, Raja Kawiha Tuli II.

The modern town and port of Kalabahi sits at the head of Kalabahi Bay

In 1906 it had been decided to construct a new administrative centre at Kalabahi at the head of Kalabahi Bay (Rodemeier 2006, 81). Kalabahi means 'kusambi tree', after the many kusambi tress that once grew there. From now the focus would move away from Alor Kecil at the mouth of the bay to Kalabahi at the head of the bay. The main seaport was moved from Alor Kecil to Kalabahi in 1911.

In July 1910 Lieutenant Adelberg was sent from Kupang to the new centre of Kalabahi with three detachments of marechaussee (military police). It seems that even the mountain dwellers on Alor respected the well-armed troops and were generally cooperative (Van Galen 2010, 22). The population of Alor Island was registered, their muskets and other weapons were destroyed and the Rajas were pressurised to sign the Korte Verklaring or ‘Short Declaration’ – a one-sided agreement in which they recognised the sovereignty of Holland and agreed to obey all of the laws and rules of the government of the East Indies. The census enabled the Dutch to levy taxes in the form of heerendiensten or unpaid labour (Dietrich 1985, 279).

At around the same time Raja Kwiha Tuli II became ill and delegated responsibility to Nampira Bukang, the Kapitan of Dulolong. Controleur Meulemans refused to accept this compromise and raised Bukang Nampira as the new Raja of Alor, thus transferring the Rajadom from the noble Tulimau family in Alor Besar to the Nampira family in Dulolong (Gomang 1993, 81). Nampira Bukang was much preferred because he was educated, wealthy and influential and, furthermore, fluent in Dutch. As a consolation the former Raja was appointed Kapitan. The Tulimau family refused to accept this decision lightly and in 1916 incited a revolt on the Kabola Peninsula, while making several attempts to burn down the house of Raja Nampira Bukang at Dulolong.

During Meulemans tenure at Alor Kecil, protestant missionaries linked to the Indische Kirk (the Dutch Reformed Church in the East Indies) were brought to Alor Island to spread the Gospel and to encourage converts to be baptised. In the early 1910s religious teachers were brought in from Rote (Aritonang and Steenbrink 2008, 306). The first church on Alor was built in Kalabahi in 1912 using a Muslim workforce.

In 1915 Bukang Nampira was briefly succeeded by his son, Bala Nampira, who in 1918 was murdered by rebellious mountain people. His brother, Umar Watang Nampira, was appointed caretaker Raja of Alor landschap and became the official Raja the following year. He ruled until 1952. Throughout this period Ternate and neighbouring Buaya remained under the control of the Atabeng of Alor Besar, within the landschap of Alor.

Raja Umar Watang Nampira, who ruled from 1919 until his abdication in 1952

After independence this administrative structure remained in place until 1965 when it was replaced by six new districts or kecamatan, each headed by an elected kepala desa.One of these was Alor Barat Laut, which encompassed most of the Bird’s Head Peninsula. This was divided into a number of desa or extended villages, one of which was Alor Besar. The latter included the offshore islands of Ternate and Buaya.

Over the years the residents of Ternate and Buaya became increasingly dissatisfied with their position in this structure, which left them on the periphery of the region's administration and economy. In the early 1990s, the menfolk of the two islands revolted, sailing to Alor Besar and demanding their separation from the mainland village (Wellfelt 2007, 10). Although some were arrested and imprisoned, their protest did make an impact. In 1994 Ternate and Buaya became desa persiapan (preparatory desa) and in 1996 full desa.

Return to Top

Uma Pura Textiles

The majority of women in Uma Pura are involved in textile production, not just for themselves but as an important commercial enterprise to support their families. The village is alive with activity, with women binding, dyeing and weaving everywhere.

In the past the conditions on Ternate made it hard to grow sufficient quantities of cotton. In response the weavers from Uma Pura would use small canoes to take textiles to the pottery-making village of Ampera on the Bird’s Head Peninsula of Alor. Textiles were bartered for cooking pots, which were then taken to Ili Api on the island of Lembata. There the pots were bartered for raw cotton; the exchange rate for a pot was the amount of cotton that could be pressed into the vessel. Finally, the weavers would return with the cotton to Uma Pura and work until the need for cotton forced them to repeat the journey all over again (Wellfelt 2014, 6).

This shortage of cotton encouraged some weavers to weave using the silk-like fibres from the seed floss of Milkweed (Calotropis gigantea), a coastal shrub locally known as kroko lolong. The fibres are difficult to spin – they are short, smooth and light and are easily blown away from the seedpods. Because they are so difficult to spin, the weavers process the fibres in a cave and mix them with the longer fibres of cotton, rolling them into punis, which can then be spun back in their homes.

Although the majority of cotton used on the island today is commercial, the women now plant cotton in their gardens across on the mainland at Padang and Sebanjar. Many women can still process raw cotton and spin it using a wheel.

Spinning cotton in Uma Pura on a hand-turned wheel or tanue

In some areas of eastern Indonesia, weaving only continues to thrive in those places where there is a shortage of land for farming. This is especially true for Ternate and explains why most of the women in Uma Pura devote a large proportion of their time to the production of textiles. Because of its focus on textiles and its wide variety of patterns, some local people call Uma Pura ‘the one-thousand motifs village’.

Today Uma Pura has five weaving Kelompok Pengrajin Tenun Ikat (Ikat Weaving Craftswomen Groups), four of which are:

- Kelompok Pantai Laut (Seashore), founded in 2000 which has 15 members

- Kelompok Cakrawala (Horizon), founded in 2000 which has 15 members

- Kelompok Beringin Jaya (Banyan Tree), founded with 15 members in 2000, it now has 32

- Kelompok Bijati (Wise), founded in 2009 which has 15 members

- Kelompok Mezbah (Place of Ritual), founded in 2000 which has 15 members

Some of the women take their weavings across to an early morning weekly market on the mainland close to Alor Besar, where they are bought by local people from Alor Kecil and Kalabahi, as well as by small-time dealers.

Return to Top

Uma Pura Natural Dyes

Mama Sahari Karim, the leader of Kelompok Pantai Laut (Group Seashore), claims that the weavers make around one hundred natural dyes on Ternate. Some ninety-three of these are derived from plants and trees and are said to be traditional – inherited from their ancestors. A further seven are extracted from marine life and are all very recent developments.

Many of these natural dyes are replicated on the mainland opposite Ternate Island at dusun Hula in Desa Alor Besar, just north of the Babussholah mosque. Here 45-year-old Mama Sariat Libana runs a dyeing and weaving workshop at Rumah Tenun Gunung Mako. She claims to produce 210 natural dyes, most from the foliage, bark and roots of plants, but some from marine life such as squid, seaweed, cuttlefish and sea cucumber.

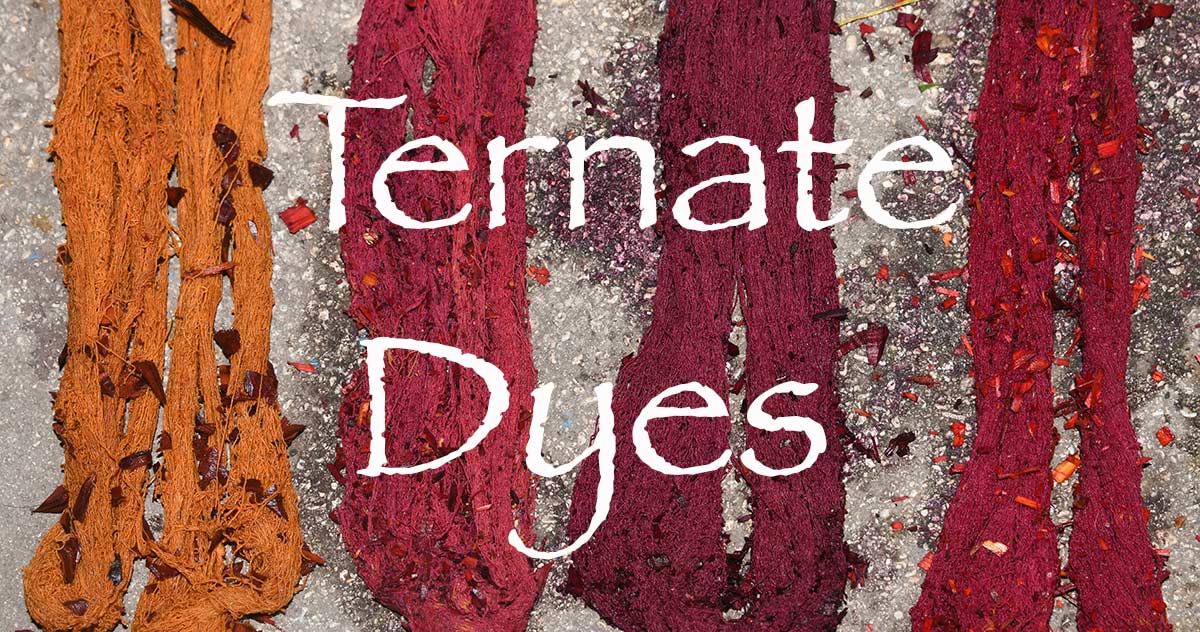

A few of the naturally dyed yarns in Uma Pura

At Uma Pura natural dyeing is a small-scale domestic activity undertaken from household to household. In the dry season, coloured yarns hang outside every other house and across open yards. In every case the cotton yarns are thoroughly wetted in cold water before the commencement of dyeing.

Return to Top

Uma Pura Marine Dyes

Marine dyes are a very recent development at Uma Pura, thanks to Mama Sahari Karim, the leader of Kelompok Pantai Laut (Group Seashore), one of five weaving cooperatives in her village. Her house is positioned on the shoreline and overlooks the Pantar Strait and the Alor mainland beyond. In 2007 she had a long dream in which she imagined that the seas surrounding her island should surely be a source of important natural textile dyes. She began to experiment and soon discovered that she could produce a yellow dye from local sea sponges. This inspired her to investigate further. Today she has successfully developed seven new marine-based dyes.

Mama Sahari Karim with one of her hand-spun and naturally dyed textiles

Sea Sponge Dyes

Sea sponges (phylum Porifera) are the simplest of all multicellular animals, being immobile and having no fixed body shape. They consist of a colony of individual cells held in place by a skeleton or matrix, which can be made from various materials such as calcite, silica or protein (Moore 2001, 21-22). To discourage predators, sponges produce an array of biotoxins. On the shore and in shallow seas, many are often brightly coloured - yellow, orange, red, green or violet - possibly to warn predators that they are inedibile.

In Uma Pura sponges are called kula. The yellow sponge is called kula kumong and produces a pale yellow pigment. The rust-coloured sponge is kula kumong tua, and produces a strong yellow. The grey sponge is kula avo avo (meaning grey) and produces a pale blue or grey. Finally the black sponge is called kula kemuning and produces a dark purple.

Four different coloured sea sponges from Ternate – yellow, orange, grey and black

The process for producing a sponge-based dye is the same for all four different sponge types. The sponges, still holding some seawater, are cut into small pieces and placed in cold water. The cotton yarns are soaked in the mixture for one night before being all boiled together. The sponges are then exhausted and cannot be used again. However this process must be repeated several times using new sponges for each stage until the desired colour is achieved.

The yellow obtained from kula kumong is compared to the colour of bamboo stems

A warm grey from kula avo avo

Mulberry-coloured yarns obtained from multiple dyeing with kula kemuning

Sea Urchin Dye

Sea urchins are simple animals belonging to the class Echinoidea (from the Greek ekhinos, spine) within the phylum of Echinodermata, which also includes starfish and sea cucumbers. They have a rigid, usually spherical, calcareous shell bearing moveable spines which protects the soft internal digestive system.

In Uma Pura small sea urchins are called bragang. They produce a light brownish-purple or light purple pigment. It requires a large number of urchins to make the dye and they must be fresh. Only the insides of the urchins are used and these must be boiled.

A bowl of live sea urchins and sea cucumbers

A pale brown from the intestines of sea urchins

Sea Hare Dyes

Sea hares are slow-moving shell-less gastropod molluscs that belong to the order Anaspidea (meaning lacking a shield). They are related to the sea cucumbers and live on patches of sand, in seagrass beds, coral reefs and even exposed reef flats. Their humped body and ear-shaped chemosensory rhinophores give them the appearance of a crouching hare, hence the name. They have a range of anti-predatory defences, one being the secretion of a toxic ink that is a mixture of two glandular products – purple ink from the ink gland and sticky white opaline from the opaline gland.

In Uma Pura they are called uve kotong and come in two different forms – a light sea hare that lives on sand and a black sea hare that lives on rocks. Both produce exactly the same pigment.

The dyers cut the live sea hare with a sharp knife and pierce the ink sac, collecting the purple ink in a bowl. This is used directly as a dye and produces purple.

Collecting the purple ink from the sea hare

Light purple obtained from sea hare ink

After emptying the ink sack, the innards of the sea hare are removed and used to make an attractive sage green pigment.

Sea hare sage greens

Return to Top

Uma Pura Vegetable Dyes

Indigo thrives on the hot coastal lowlands of Ternate Island, while morinda and many other trees grow on the slopes of the mountain. The undeveloped shorelines are covered with dense patches of milkweed and castor oil. Corals can be burnt and ground into lime powder.

The scrubby, boulder-strewn slopes of Ternate Island

Castor Oil and Milkweed grow in profusion along the coasts of Ternate

However the dyers of Uma Pura are not entirely self-sufficient. Some materials like mangrove bark and the leaves and bark of loba must be obtained from the mainland.

Indian Mangrove Bark

On Ternate, Indian mangrove (Ceriops tagal) is referred to as tongke. It has to be imported from either Alor or Pantar. Some grows on the west coast of the Kabola Peninsula at Seieng or along the northeast coast of Pantar at locations like Muna Seli. However the biggest mangrove forests are found on Kangge Island in West Pantar. For more details click here.

The Indian mangrove bark is boiled in water and after one immersion it produces a rust-brown or orange-brown.

Hanks of yarn dyed with tongke

An immersion in tongke followed by another in morinda (or vice versa) gives a chocolate brown. The simple sash below has stripes of tongke, tongke with morinda and indigo.

Kayu Hidup Bark

The pink bark from kayu hidup produces a pale pink dye. We have yet to identify the species of tree – kayu hidup simply means live wood. The bark must be boiled in water.

Pieces of salmon-pink kayu hidup bark

Kayu hidup bark and the pale pink dye that it produces

Hong Tree Dyewood

The heartwood of the hong tree, known as kayu hong, produces a stunning deep cerise pink or cherry red. The tree is also called kayu pen because it is also used to make the pen, the laths that connects one beam to another beam when contructing a house. The wood is also used by fishermen to make their perahus. The tree is known as kanuru on Sumba Island.

We have yet to identify the species concerned.

One possibility is Sappanwood (Caesalpinia sappan), a small to medium-sized, shrubby tree, normally 4 to 8 metres tall with yellow flowers. Its heartwood looks similar and yields the red crystalline dye, brazilin, which produces a range of colours from deep crimson to pink.

Another possible candidate is the Red Sandalwood or Coral Tree (Adenanthera pavonina), a fast growing tropical tree that grows at lower elevations and is deciduous, shedding its feathery leaves briefly once a year. It has an orange bark that produces a strong red dye. The heartwood is bright yellow when fresh, turning red upon exposure to the air (Barwick 2004; Quattrocchi 2016, 78).

At Uma Pura the heartwood of the hong tree is chopped into slivers, which are then crushed with a heavy stone before being boiled. The raw wood is a yellow-orange but turns bright pink when soaked in water.

Slivers of hong tree bark and the pigment that it produces

Boiling the crushed hong bark with yarn

The addition of lime powder to the hot dye bath produces an attractive mulberry colour.

Mulberry-coloured yarns drying in the sun

The addition of lime juice to the hot dye bath produces a yellowish-pink plum colour.

After the addition of lime juice

Hong bark with left: lime juice; middle: lime powder; right: hong bark alone

These colours will lighten considerably as the yarns dry.

Morinda

The women of Uma Pura refer to morinda as bota. It grows on the slopes of Ternate Island but is not used as widely here as it is elsewhere in eastern Indonesia – probably because dyeing with morinda is a laborious process and here there is a much wider choice of alternative dyes.

Hanks of morinda-dyed commercial cotton drying next to the frame of a loom

First the yarns must be pre-mordanted in an alkaline mixture of crushed kemiri or candlenut. After drying they are then dyed in a bath of morinda root bark and the bark and leaves of loba, which provide the aluminium mordant. Loba is a large tree belonging to the Symplocos species, which grows in the highlands on the Alor mainland.

For full details of the morinda-dyeing process click here.

Kayu Kuning

Kayu kuning (literally yellow wood) is a dyewood taken from the heart of the Cockspur Thorn (Maclura cochinchinensis), a long-lived woody erect climber or scrambling shrub. The women of Uma Pura also call it akar kuning or yellow root. It is widely used throughout eastern Indonesia. For more details click here.

Above: a section of kayu kuning dyewood; below: yarns steeping in a cold bath of kayu kuning

Kayu kuning produces a much stronger mustard-yellow colour than sea sponges. The wood chips are boiled in water and the yarns are left to soak overnight.

Turmeric

As elsewhere in eastern Indonesia the dyers of Uma Pura refer to turmeric (Curcuma longa) as kunyit. For full details of this dye click here.

At Uma Pura they heat the chopped kunyit in water to produce a golden-yellow dye. Adding acidic lime juice to the dye bath produces a much lighter yellow, while the addition of alkaline lime powder creates a dark orange colour.

Yarns are added to hot chopped turmeric

The addition of lime juice considerably lightens the dye

Above: yarns given one immersion in hot turmeric

Below: yarns dyed with turmeric after the addition of lime juice

The dye bath after the addition of lime powder

The women of Uma Pura produce a different light yellow from the crushed leaves of Milkweed, chopped turmeric and crushed candlenut (kemiri) without the addition of lime. This is a cold process.

Milkweed

Milkweed (Calotropis gigantean) grows in profusion around the coastlines of Alor Regency. In Uma Pura it is called kroko lolong.

Milkweed growing beside the beach on the north coast of Alor

The leaves are smashed with a stone and boiled in water to produce a light green chlorophyll dye.

A boiling bowl of crushed Milkweed leaves

One immersion produces a pale green

A khaki green can be produced by the addition of purple sea hare ink and the extract from black sponges.

Indian Almond

Indian Almond (Terminalia catappa) is a large tropical tree that thrives in eastern Indonesia, including Ternate. Local people refer to it as ketapang.

The young leaves are chopped and boiled to create a green dye called talehi kal.

Freshly cut ketapang leaves

A stunning turquoise is obtained by dyeing yarns in indigo and then overdyeing them with ketapang.

Yarns that have been dyed with indigo followed by ketapang leaf

Castor Oil

A local variety of Castor Oil (Ricinus communis) grows in profusion along the undeveloped coastline of Ternate, growing in thick stands alongside clumps of Milkweed.

The dyers of Uma Pura call the plant umanena and use both the leaves and the outer skin of the stalks. Boiling the chopped sticky leaves produces a dark beige or dull khaki green.

The sticky leaves of Castor Oil

Yarns immersed in boiled chopped Castor Oil leaves

To make a different colour, the outer skin of the Castor Oil stalks are stripped off in long lengths and are then boiled to produce a straw or cinnamon coloured dye.

Yarns after just being immersed in a bath of Castor Oil stems

Colours obtained from the Castor Oil plant. Above: from the leaves; below: from the stalks

Yarns just dyed with the stalks of Castor Oil drying in the sun

Indigo

The women of Uma Pura refer to indigo as ta’ang. It is used widely in their local textiles.

Indigo dyeing has been covered in great detail elsewhere on this website - click here for details.

Hanks of indigo-dyed yarn drying in Uma Pura

Treating deeply dyed indigo yarns with the dye mix extracted from yellow sponges, kula kumong, produces a dark blue green.

A ball of hand-spun yarn dyed with indigo and kula kumong

Return to Top

Bibliography

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor, 2017. Alor Barat Laut Dalam Angka 2017, Kalabahi.

Faulkner, Kay, 2018. Kay Faulkner’s Blog, May 2018: Part 2 of The Lesser Sunda Islands trip; The Volcanic Islands - Andora, Lembata, Ternate, Alor, Pantar, accessed 05.11.18. Kay Faulkner visited Ternate Island with us in May 2018 as a guest on our Textile Tour of the Lesser Sunda Islands. Her notes contain a few errors - as did ours, which is why we returned.

Gomang, Syarifuddin R., 1993. The People of Alor and Their Alliances in Eastern Indonesia: a Study in Political Sociology, M. A. Thesis, Wolongong University, Wolongong.

Klamer, Marian, 2012. Papuan-Austronesian language contact: Alorese from an areal perspective, Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century, pp. 72–108, University of Hawai'i Press, Honalulu.

Klamer, Marian (ed.), 2017. The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology, Language Science Press, Berlin.

Rodemeier, Susanne, 2010. Islam in the Protestant Environment of the Alor and Pantar islands, Indonesia and the Malay World, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 27-42.

Wellfelt, Emilie, 2007. Diversity and Shared Identity: A case study of interreligious relations in Alor, Eastern Indonesia, MA Thesis, Göteborg University, Sweden.

Wellfelt, Emilie, 2014. The Secrets of Alorese ‘Silk’ yarn: Kolon susu, triangle trade and underwater women in Eastern Indonesia, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, Los Angeles.

Publication

This webpage was published on 14 November 2018.