Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Location of Janggamangu

Umbu Dongga Landu Praing

Umbu Diki Dongga

Janggamangu Textiles

Janggamangu Lau Hiamba

Janggamangu Hinggi Patola Kamba

Other Janggamangu Hinggis

Bibliography

Introduction

Although Janggamangu is only a small hamlet in the former domain of Kambera in East Sumba, it is the source of some unique and distinctive textiles that are quite unlike anything else produced on the island of Sumba. They are mostly inspired by the motifs found on a specific type of Indian double ikat silk patolu that was produced in Gujarat in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, if not earlier. Many seem to have been exported to mainland Southeast Asia and Indonesia by the Dutch VOC and their antecedents. However the inspiration for the weavers of Janggamangu was more likely a much cheaper block-printed cotton imitation of that same design of patolu, many of which have been found across the Indonesian Archipelago from Sumatra to Bali and the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Gujarati patola brought to the East Indies before and during the colonial period influenced the designs on many textiles found across Indonesia. Janggamangu not only provides us with a more recent example of the persuasive influence of patola designs on local textiles but also shows the willingness of Indonesian weavers to reinterpret imported designs and make them their own.

Return to Top

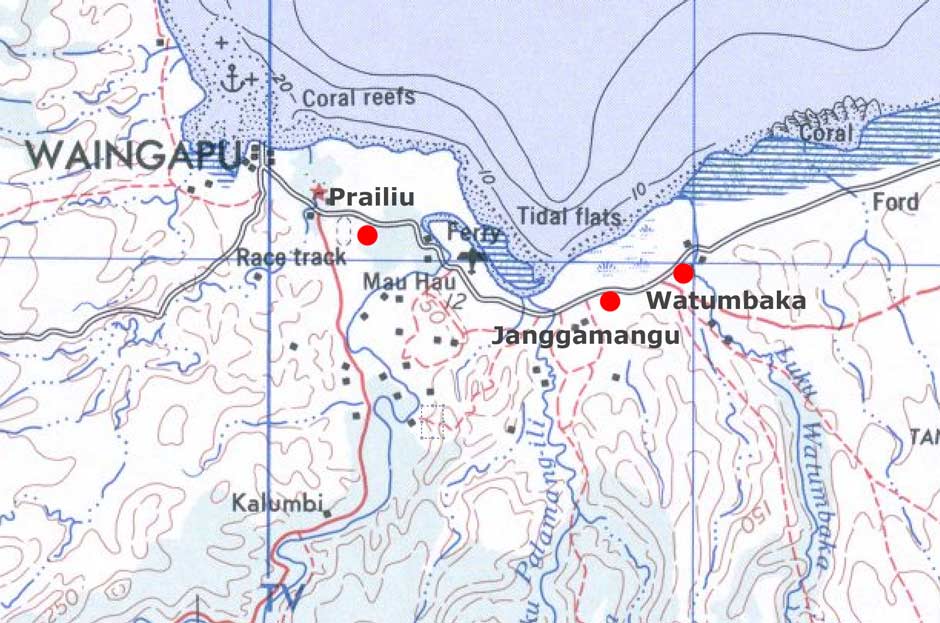

Location of Janggamangu

Janggamangu, or sometimes Jangga Mangu, is a small hamlet located about 9km east of Waingapu, the capital of East Sumba Regency, Sumba Island. It lies about one kilometre from the coast, just south of the main road to Melolo and just beyond Kawangu 5km east of Umbu Mehang Kunda Airport. The village of Watumbaka lies just to its east while the royal kampung of Prailiu, the capital of the former domain of Kambera, lies just to the west.

In the past Janggamangu was an important small domain headed by a wealthy commoner called Umbu Diki Dongga. It encompassed a large area of highland savannah which extended southwards over the limestone plateau.

Janggamangu, 9 km east of Waingapu centre

(Mapcarta and Mapbox Creative Commons Licence)

The location of Janggamangu at the foot of the limestone escarpment

Jangga means to be high or tall or even arrogant, while a mangu is an owner or possessor (Klamer 1998, 149, 230, 311, 359). For example, the term mangu paja na refers to the leader of a hunting party who places a levy or tax (paja) on the animals that are killed (Geirnaert-Martin 1992, 363).

Note that there is a village of the same name in Kecamatan Karera.Return to Top

Umbu Dongga Landu Praing

The domain of Janggamangu came to prominence in the early twentieth century under the leadership of the formidable Umbu Diki Dongga. He was not a royal noble but was a wealthy, powerful and influential commoner (kabihu). Despite his lack of royal blood he was still addressed as Umbu – roughly translated as Sir or Lord.

His father was Umbu Dongga Landu Praing, who was also a wealthy landowner and commoner who lived at Watumbaka, about 15km east of Waingapu. He was a fearless warlord who supported the King of Prailiu. Throughout his life he was assisted by Ana Kami, who was not only his wise and faithful slave, but also his lifelong companion.

Umbu Dongga’s wealth was based on his extensive landholdings and large herds of horses, cattle and goats, many of which were stolen from neighbouring farmers. Ana Kami was very skilled at cutting the ears of the livestock to conceal the identity of their former owner. This was still a time of ruthless anarchy on Sumba Island when theft was common. Umbu Dongga was not immune to this himself - rustlers who evaded his guard dogs stole two of his best horses and even a pig (Wielenga 1928, 24). Umbu Dongga could be brutally violent – those who were caught stealing were treated harshly, sometimes beheaded or thrown to the river crocodiles.

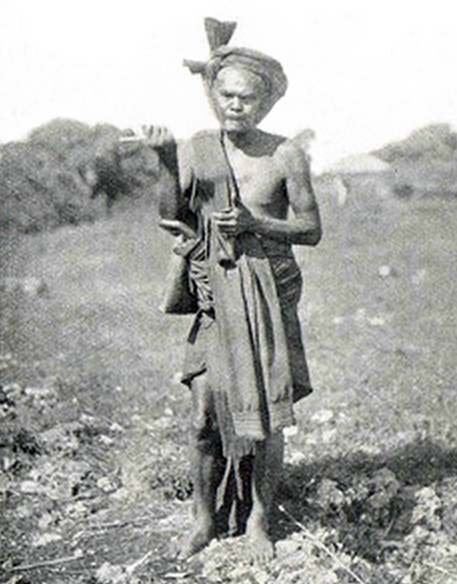

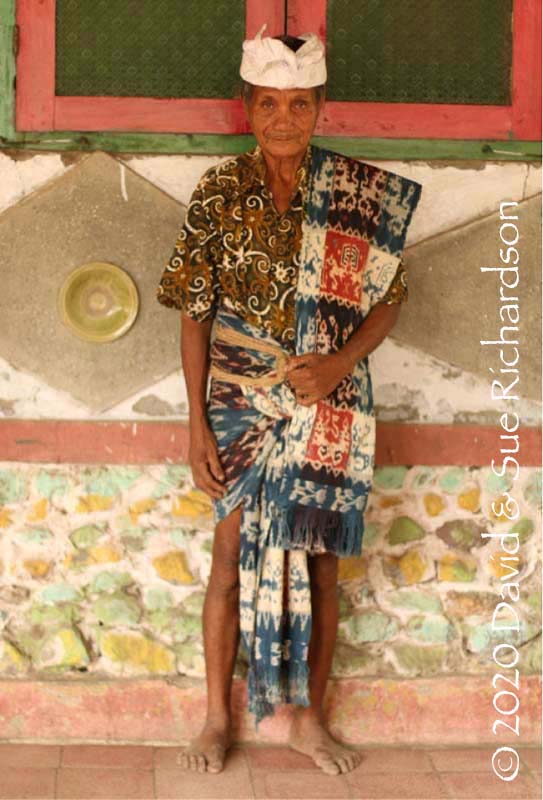

Umbu Dongga Landu Praing, the head of the family, dressed in a barkcloth kambala headdress and a plain hinggi hip-wrapper and shoulder cloth (Wielenga 1928)

The rise and fall of Umbu Dongga was the subject of an allegory written by the Protestant missionary Douwe Klaas Wielenga, who from 1907 until 1921 was based at nearby Payeti, 5km west of Watumbaka. Unfortunately the book is not a biography and is devoid of dates or the details of specific locations.

Wielenga described Umbu Dongga as follows (1928, 7):

He was a man of strength and brute force ... he had a booming voice that could command. The sound of his voice, the sparkling of his eyes, and the gesture with which his right hand would reach for his long knife, was more than enough to make one take him seriously.

Wielenga painted us a picture of Umbu Dongga on horseback. Dressed entirely in black, his four-meter-long dark loincloth was held in place with a rope and rattan braided waistband. This supported the wooden sheath holding his great machete with a black horn handle. About his naked upper body he wore a rigid black, densely-woven shoulder cloth while in his right hand he held an ancestral lance of black ebony with a razor-sharp steel spearhead, an heirloom from many generations ago. He was as agile as a cat, but muscled like a buffalo. His black stallion was almost ‘uncontrollable in its wildness’. But once the powerful Umbu Dongga mounted the saddleless beast it was well restrained.

Umbu Dongga was extremely experienced in all kinds of religious matters and knew an extensive litany of prayers. He was also an expert in all adat matters concerning marriage, birth and burial. He was fully conversant with the mutual family relationships of the different tribes and those of the families and houses of his own domain as well as adjacent domains.

In addition to being rich and ruthless Umbu Dongga could also be very generous, helping when someone needed to pay a dowry or hold a funeral party.

Although he normally dressed in simple, sometimes dirty, clothing, Umbu Dongga would dress in beautifully woven cloths for family meetings and ceremonial occasions (Wielenga 1928, 47). Some of these were made by his second wife, who was considered a proficient textile artist, skilled in arranging beautifully styled figures and colours. For this reason he had to pay a very high bridewealth to marry her (Wielenga 1928, 47).

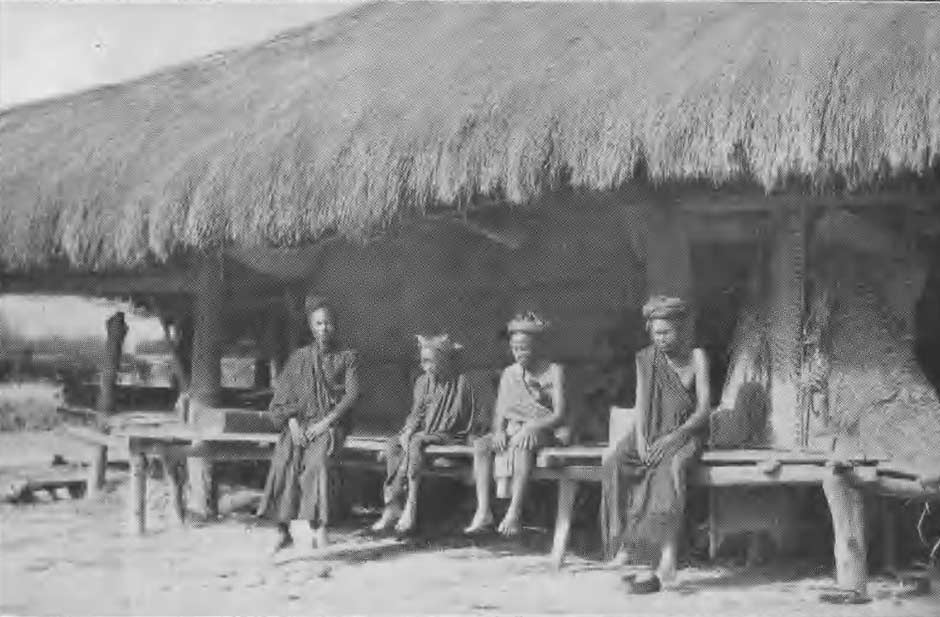

A gathering of important headmen

(Wielenga 1928)

Umbu Dongga’s fifth wife came from the royal family of nearby Kawangu. As a wedding gift the King of Prailiu gave him land at Janggamangu, adjacent to Watumbaka.

The situation for Umbu Dongga changed radically at the end of the nineteenth century, as the Dutch began to rethink their policy of non-intervention in their East Indies territories and began to move towards the imposition of direct rule.

After the Dutch had established a presence on Sumba, Umbu Dongga became embroiled in a venture that would lead to his downfall. He was summoned to a meeting with a close ally, the nobleman Umbu Lara Lunggi, who lived in Uma Malai in the village of Kanatang, one day’s ride from Watumbaka. Umbu Lara Lunggi owned the largest herd of horses on the island, some sixty of which had been stolen by a village just over the border of his domain. Umbu Lara Lunggi was set on revenge and the two embarked on a retaliatory raid supported by 120 heavily armed men (Wielenga 1928, 90). After attacking the offending village and killing a dozen defenders, they enslaved some 40 men and women and incinerated all of the houses.

The Dutch had so far not intervened in such inter-tribal disputes, but when the attacked villagers complained to the military authorities in Waingapu they decided that this was a good opportunity to tighten their grip on the unruly tribes. A junior Lieutenant and 60 troops were dispatched by sea from the port of Waingapu. Umbu Dongga and Umbu Lara Lunggi retreated with their supporters to the well-defended hilltop village of Paraing Madita in the southern highlands - but the experienced Dutch troops stormed their redoubt. Umbu Lara Lunggi surrendered but Umbu Dongga and Ana Kami escaped, seeking refuge with a tribe in the mountains and travelling from village to village to evade the relentless pursuers. Meanwhile Dutch forces searched Watumbaka and confiscated Umbu Dongga’s herds of horses and buffalo. After months of evasion, Ana Kami attempted to persuade Umbu Dongga to submit to the Dutch, but Umbu Dongga stubbornly refused. It was only after many more months of hardship that he finally reported to the military based in Waingapu harbour, where he was fined and detained until the amount was paid.

The Dutch referred to individuals like Umbu Dongga as kabana-mbani or angry men. Roughly translated the word mbani means anger, daring, threatening behaviour or rage (Kuipers 1998, 47-48). Such powerful individuals were often the subjects of various colonial reports, since many fiercely resisted Dutch rule.

This long ordeal broke Umbu Dongga’s spirit. During his absence, his once busy village of Watumbaka had become deserted. Under the new Dutch administration people felt safe and no longer needed to have the protection of a strong leader and live behind fortified walls of cactus. People could go about freely and build their homes in a field or their gardens or on the bank of the river. In Wielenga’s words: ‘The people went their own way and left him alone to sit in the deserted village’. The village square had filled with weeds and the houses had become neglected and dilapidated. With most of his livestock gone, his power and influence had largely disappeared. Umbu Dongga and Ana Kami left the village and built a new house in the valley on the bank of the river.

Umbu Dongga on his veranda mourning for his late slave Ana Kami

(Wielenga 1928)

A few years later Umbu Dongga was devastated when his slave, Ana Kami, died after suffering from a long fever. His master hosted a lavish burial ceremony, inviting many guests from the neighbouring villages and the coastal towns. After the ritual sacrifice of buffalo and a horse, Ana Kami was buried outside the village on a high hill in a stone sarcophagus covered with a huge stone, just like a nobleman. The body of Ana Kami had been wrapped in so many textiles and beautifully coloured cloths that it had become a shapeless bundle, so large that they had to force his corpse into the burial hole (Wielenga 1928, 170, 173 and 175).

The cost of Ana Kami’s funeral had not only left Umbu Dongga almost bankrupt, but also friendless and lonely. He died at some time between 1927 and 1930, something of a broken man, his power and influence lost to the Dutch, his herds of horses and cattle much diminished and his former followers widely dispersed.Return to Top

Umbu Diki Dongga

Umbu Dongga Landu Praing had three offspring, the first was a boy named Baku Juka Andung who was killed by the Dutch at Paraing Madita and the third was a girl called Loda Wani who died of neglect while Umbu Dongga was in hiding.

His middle child, a boy named Diki Dongga, was born in 1878. Umbu Diki Dongga grew up in the image of his father, settling himself on the land that he had inherited at Janggamangu, just east of Prailiu. Having seen the demise of his father, Umbu Diki Donnga must have been strongly motivated to rebuild the family’s herd of livestock using the very same methods he had learnt from his father – many of his animals were stolen from other breeders. Farmers who had to pass through his domain to take their livestock to market in Waingapu were fearful of losing their herds. Few searched his domain for their lost cattle because he had many slaves tending his herds. Local people also feared him, attributing him with magical, supernatural powers (Twikromo 2008, 131-132).

One estimate placed the size of his herd at 11,000 head of livestock (Twikromo 2008, 131). He became one of a few breeders who specialised in cattle exports (Metzer 1976, 49). He was described as a tau kaborangu, literally a person who is brave (Klamer 1998, 259). However the term tau kaborangu conveyed more than bravery – it referred to a fierce and charismatic individual feared for his criminal inclinations, invulnerability, anger, magical skills, cruelty, power, or courage (Twikromo 2008, 123). It echoed the kabana-mbani or angry man status of his father.

According to his grandson, Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga, the young Umbu Diki Dongga had an eye for the girls. He often flirted with the daughters of the noble royal families, greatly irritating the Rajas who did not want to see their beloved offspring mixing with a commoner. At some time around 1927, one influential Raja persuaded the Dutch to have Umbu Diki Dongga incarcerated on the notorious prison island of Nusa Kambangan in southern Java. While he was there he received news that his father was sick and was released on compassionate grounds. By the time he returned to Sumba his father had died.

Umbu Diki Dongga had nineteen wives. His first wife was childless but the second had two daughters, Rambu Dai Ata Luda followed by Rambu Ngguna Toba who subsequently became known as Rambu Matimbi (Lauren 2019).

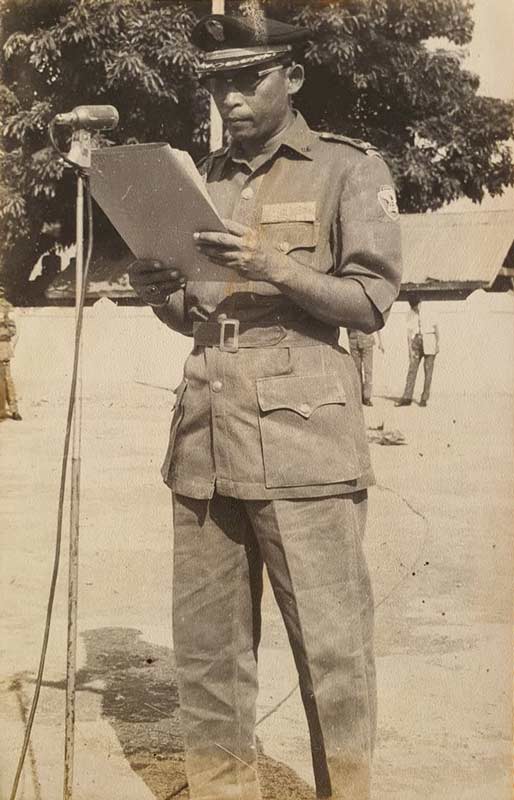

The only image of Diki Dongga that we can find, taken in the early 1970s

Image kindly supplied by Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga, one of Diki Dongga’s grandsons

In the 1950s Umbu Diki Dongga was arrested for murder, sentenced to death and returned to Nusa Kambangan. Thanks to his extensive wealth and good lawyers he managed to get the charges against him dropped.

In the early 1970s he must have met President Suharto during his first visit to East Sumba. The following photograph shows Umbu Diki Dongga standing next to his youngest daughter Yuli, who was born in 1967, and his eldest daughter Rambu Dai Ata Luda. The horse has been specially selected as a gift for the President. It has a rare feature - spurs on all four of its legs.

Umbu Diki Dongga with two of his daughters and a horse for President Suharto

(Image courtesy of Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga, )

Umbu Diki Dongga died on 18 June 1975 at an advanced age. Apparently the livestock herd that was inherited by his family soon dwindled, some animals dying of sickness others being stolen (Twikromo 2008, 132).

Today the remains of Diki Dongga’s large house lies just south of the main highway, surrounded by a stone wall, with the old village above it.

Return to Top

Janggamangu Textiles

Umbu Diki Dongga’s first wife came from the region of Mbatakapidu, just southwest of Waingapu town. At the time of her marriage to Umbu Diki Dongga, her mother gave her an Indian sari textile to place in her dowry basket, the mbola ngandi (literally: ‘basket take’) that every bride takes to her new family. This was apparently a fragment, not a complete sari (Hambuwali 2019). It is possible that it was part of an original silk patolu. However it is more likely that it was part of an imitation cotton tradecloth that had been dyed with madder after being block-printed with the same pattern using an alum mordant. This is because the patolu motif was given the name patola kamba or cotton patola.

The design on this sari cloth was subsequently adopted as the family emblem. The very same patola pattern may also have been the inspiration for the pattern of the Balinese geringsing frangipani pattern called cecempatkan.

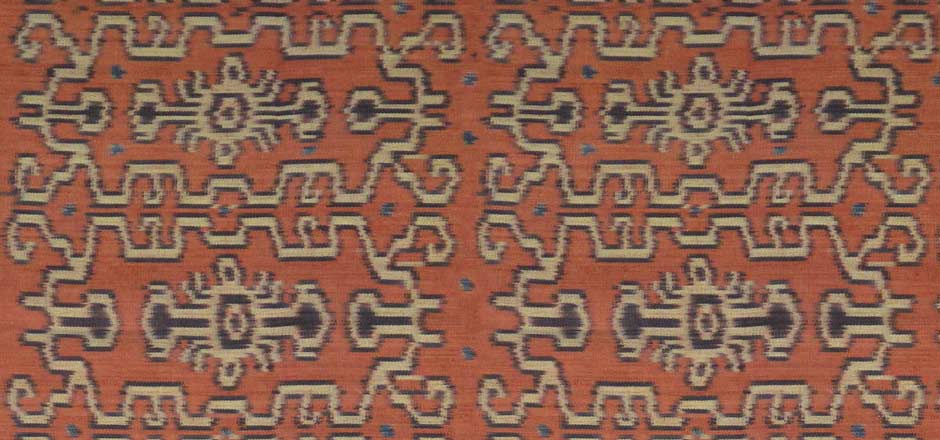

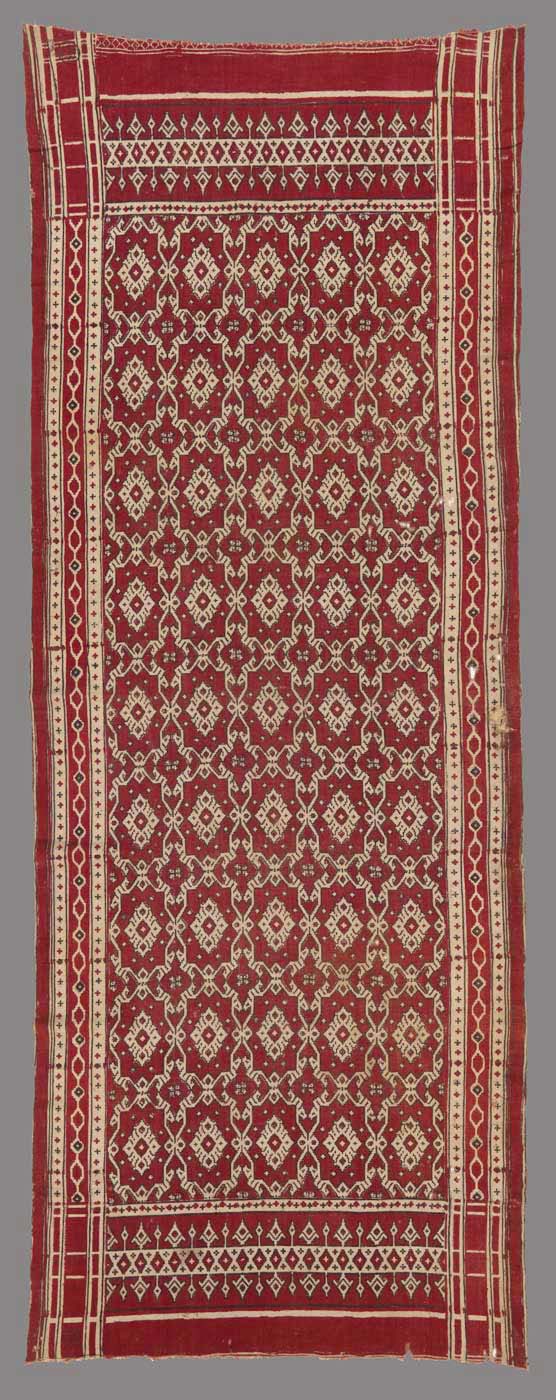

Above: the original Gujarati design

Above and below: the elongated Diki Dongga rendition. Notice the four pairs of lines that extend from the central diamond, mirroring the patolu pattern.

The double-ikat silk patolu concerned was originally woven in Gujarat for the Indonesian market. Examples of this type seem to be quite rare in museum collections. It was one of the few patterns not catalogued by Alfred Bühler and Eberhard Fisher in their monumental 1979 monograph on the Patola of Gujarat, although they did show one photograph of a printed cotton imitation.

In the opinion of the scholar and curator John Guy, a specialist in Indian trade textiles, this design may have been the most common earliest type of patola that was distributed extensively across Southeast Asia (1998, 96).

A badly damaged silk patlou made in Gujarat for the Indonesian market, 18th century

Collection of Ikuo Hirayama, Kamakura, Kanagawa

One wonders if this Gujarat pattern was in turn inspired by an Islamic carpet design (Fraser-Lu 1988, 11).

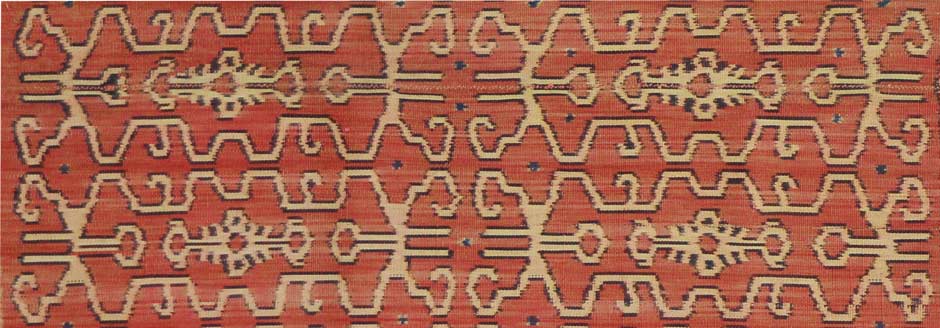

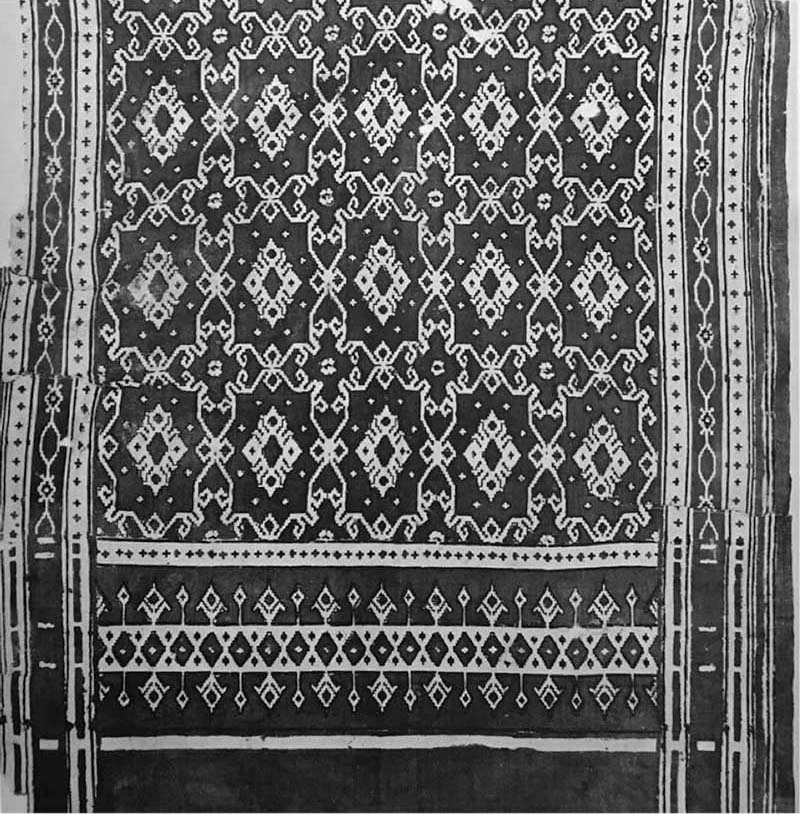

A red and black version of the same silk patolu design from south Sumatra

Museum voor Land- en Volkenkunde, Rotterdam

Another red and black silk patolu also collected on Sumatra

Holmgren and Spertus Collection

The belief that this was an early widespread patola design is reinforced by the fact that its much cheaper cotton reproduction was one of the commonest forms of imitation patola exported to Indonesia. They have been found from Sumatra to Bali (Maxwell 1990, 212). Such imitation cloths were produced as multiple copies on loom lengths of fine hand-spun cotton, each one then cut off piece by piece. Unlike the original silk double ikats they were relatively inexpensive and were probably gifted by the Dutch in considerable numbers.

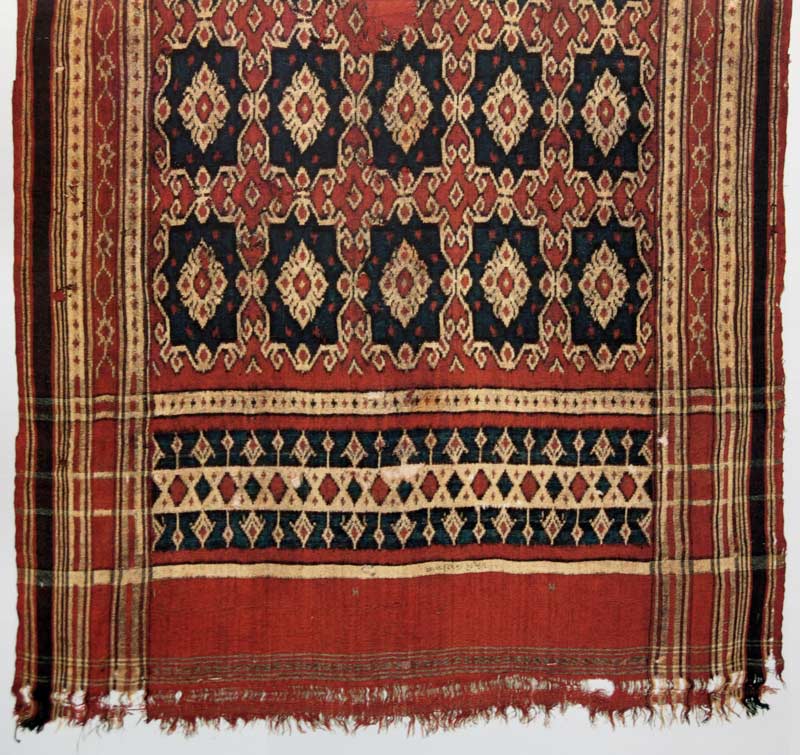

Imitation block-printed cotton patolu from Gujarat for the Indonesian market bearing a mid-17th or 18th century VOC stamp. Collection of Ikuo Hirayama, Kamakura, Kanagawa

Imitation mordant block-printed cotton patolu from Gujarat for the Indonesian market

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The process for making these cloths was relatively simple (Mohanty et al 1987, 176-177). After bleaching with dung and drying in the sun, the cotton was repeatedly treated with myrobalan (harida) until it became deep yellow in colour. The dried cotton was then stamped with carved wooden pattern blocks dipped in an alum paste, made by heating alum with water and adding it to dhawadi gum (from the Indian sumac tree). Sometimes the dyers added red lead to make the mordant visible so that they could accurately align the block prints. If the pattern included details of black, it was then stamped with smaller blocks dipped in kala paste, which contained ferrous iron. The kala was prepared by placing pieces of cleaned iron metal along with ferrous sulphate in a pot of mud and water, which was tightly closed and left for one to two weeks until the metallic iron had been reduced into the active ferrous iron mordant.

After stamping, the cloth could finally be dyed. The printed cloth was immersed in a copper pot containing an alizarin dye bath, which was gradually heated to boiling. The cloth was stirred in the boiling solution for half an hour to prevent the appearance of red stains. After dyeing, the cloth was washed in running water and exposed to sunlight to make the ground lighter. However the unmordanted sections still remained a light pink colour.

Detail of a mordant block-printed cotton imitation patolu from Gujarat, collected from Bali. Museum of Ethnology, Basle.

At least one of these mordant printed trade cloths is still in use in East Sumba today. It was used in combination with a silk patola to cover one of the corpses of three members of the nobility at a joint funeral held in Parai Yawang in the domain of Rindi in August 2005 (Breguet 2019).

A mordant block-printed cotton imitation patola covering a corpse at Parai Yawang

Image kindly provided by Georges Breguet

Return to Top

Janggamangu Lau Hiamba

Lau hiamba are tubeskirts decorated with warp ikat. Lau hiamba in which both panels were entirely decorated with warp ikat were quite common in the former domain of Kambera, especially in villages like Prailiu and Kalu just west of Janggamangu.

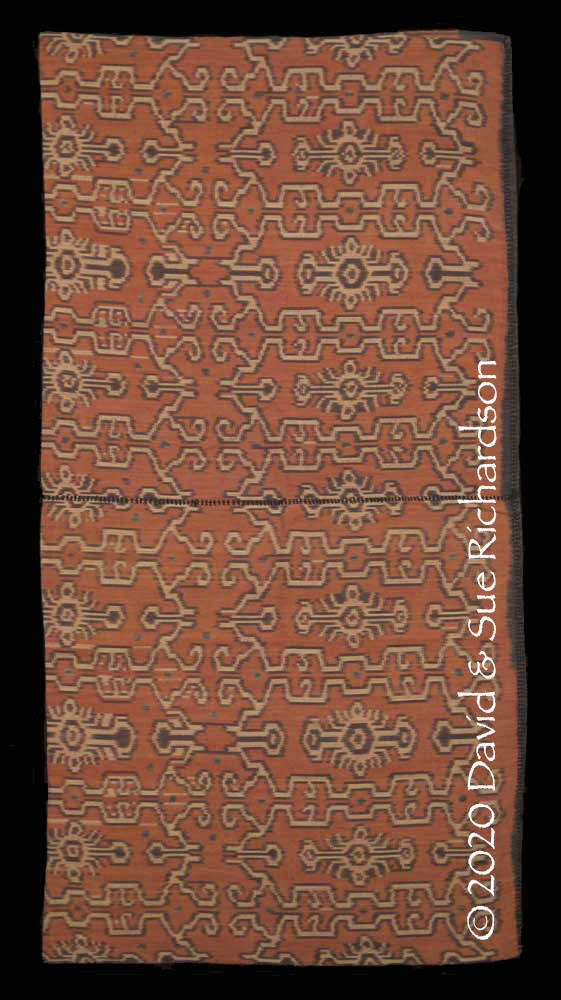

At Janggamangu, Umbu Diki Dongga’s wives distinguished themselves by producing lau hiamba with both panels bearing the new family insignia. They are known as lau hiamba patola kamba.

Rambu Dai Ata Luda, the eldest daughter of Umbu Diki Dongga by his second wife, maintained this tradition. Although her Kartu Tanda Penduduk (resident identity card) stated that she was born in 1925, her family believe that she was born at some time during the 1910s.

Umbu Diki Dongga with his eldest daughter, Rambu Dai Ata Luda

(Image courtesy of Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga)

Rambu Dai Ata Luda was a woman of considerable status, and was chosen to be the driver for President Sukarno when he visited Sumba in 1950. Her younger sister was Ngguna Toba, often called Rambu Matimbi, who is the mother of Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga, one of our informants.

Rambu Dai Ata Luda standing second from right next to the family vehicle

(Image courtesy of Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga)

Rambu Dai Ata Luda in 2000

(Image courtesy of Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga)

Rambu Dai Ata Luda produced a number of sarongs with the patola kamba design. One example in our collection was woven by Rambu Dai Ata Luda at Jangamanggu in the 1930s or 1940s. In her old age she gifted this sarong to her granddaughter, Rambu Yuliana Atambu, after she graduated from university in 2006. Rambu Atambu has since become a very senior Lutheran pastor. We acquired the sarong from her for our collection.

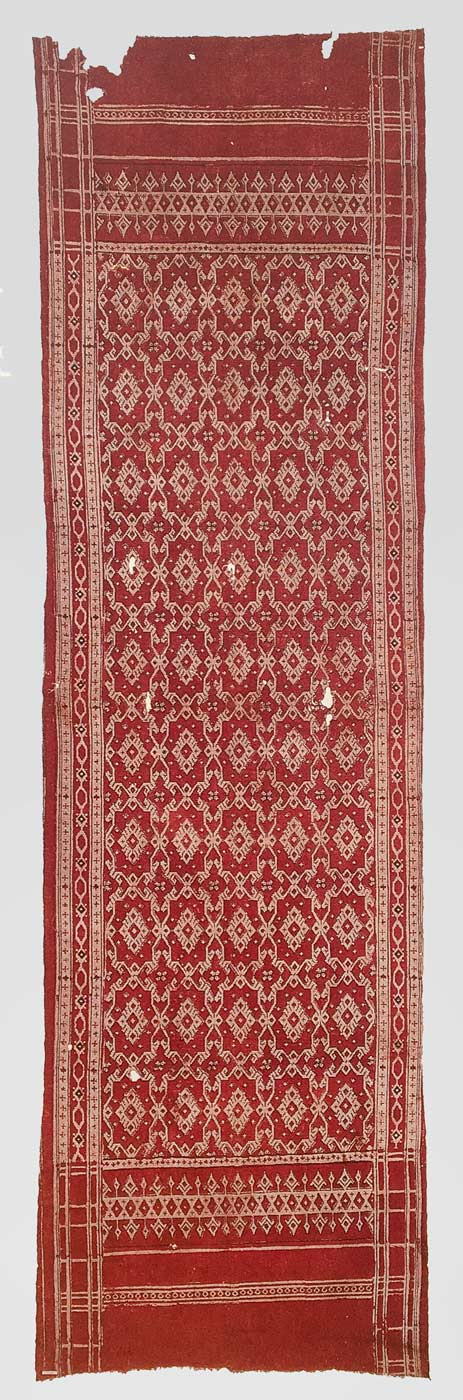

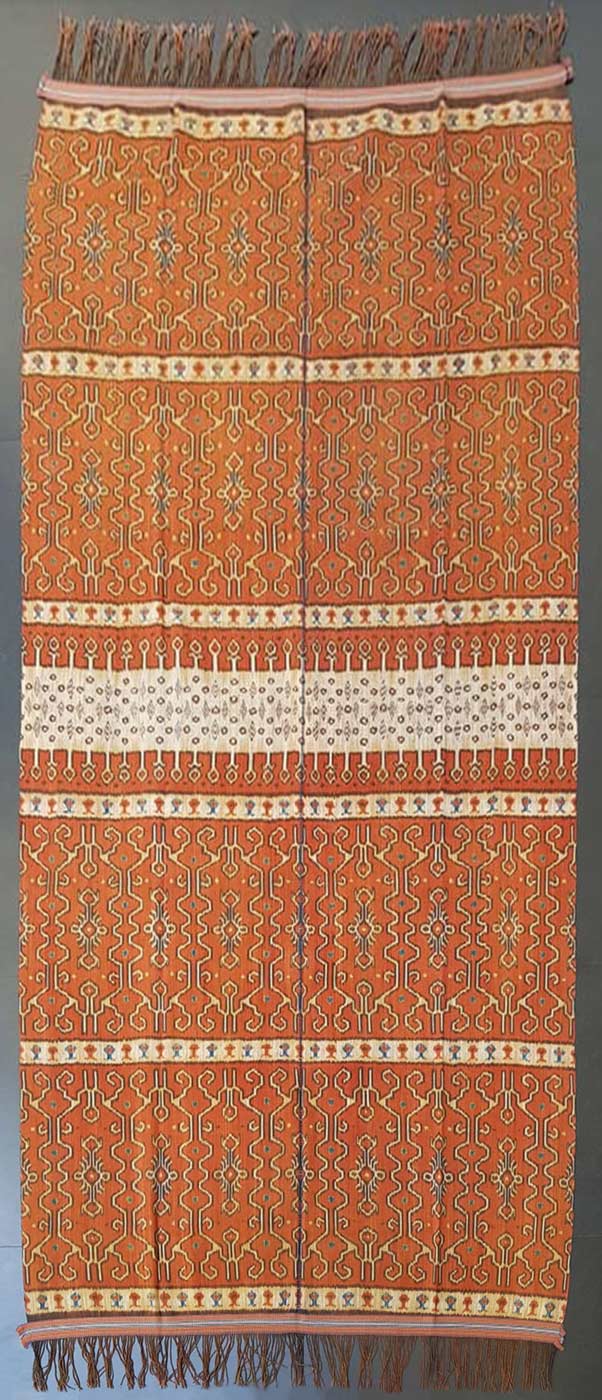

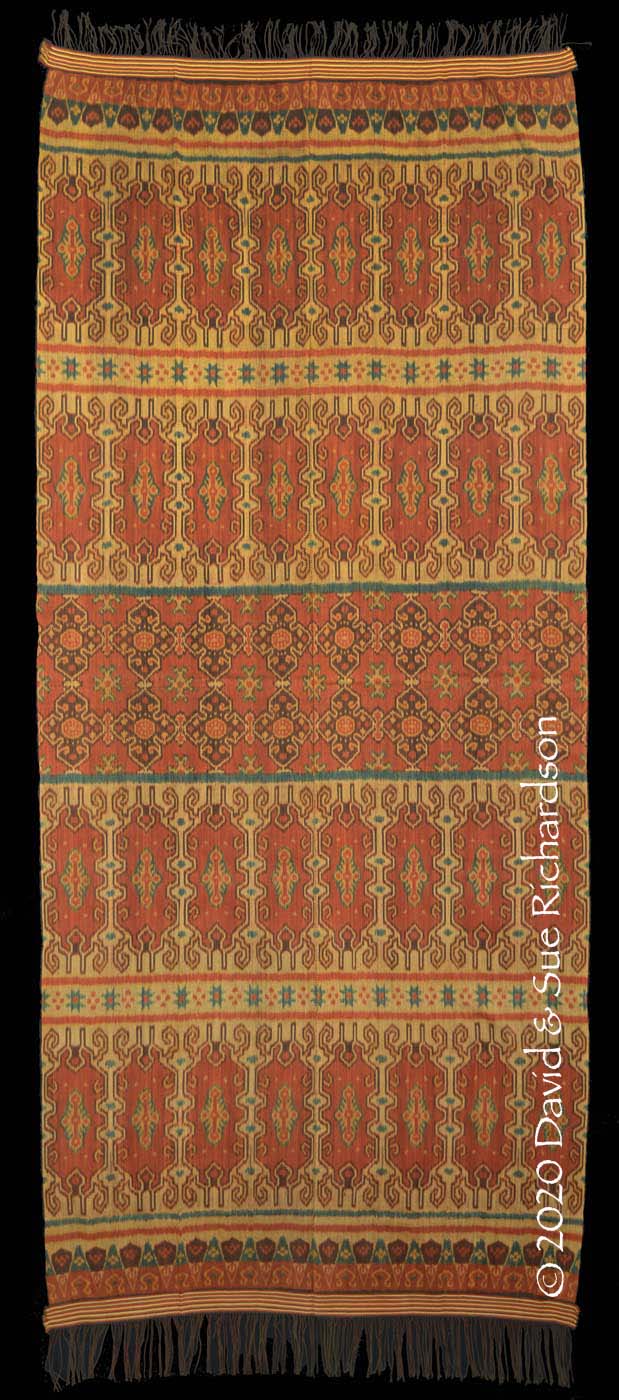

The lau hiamba patola kamba woven by Rambu Dai Ata Luda in the 1930s or 1940s

Richardson Collection

Another was gifted to Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha, the King of Karera, when he visited Janggamanggu in the 1950s. We were kindly shown this following his funeral in 2015.

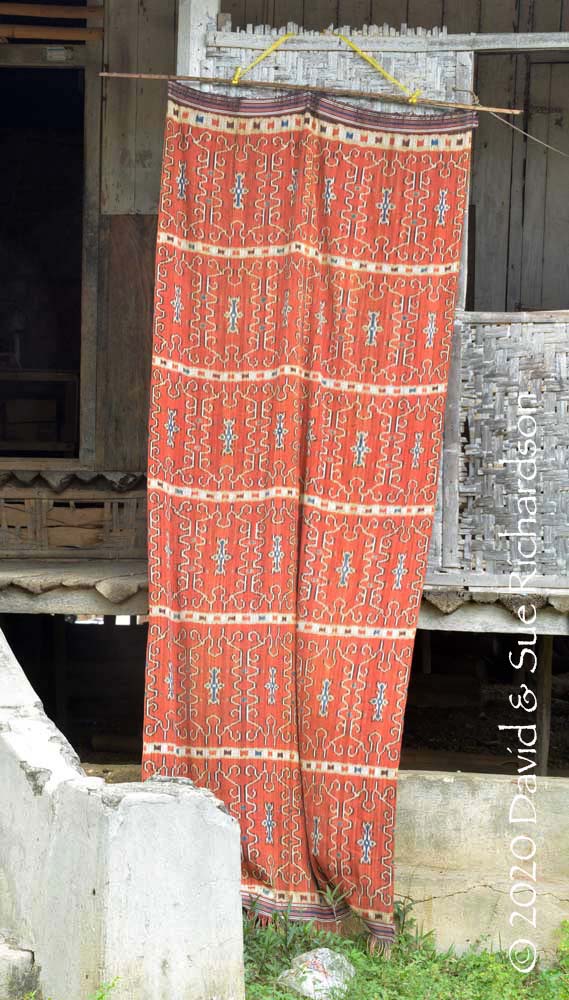

Tamu Rambu Nai Ridja, one of the wives of the late Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha, at Nggongi with the lau hiamba patola kamba made by Rambu Dai Ata Luda

Rambu Dai Ata Luda died on 19 June 2001. We believe that since then no more sarongs of this design have been woven by women belonging to Umbu Diki Dongga’s extended family.

A three-panel lau hiamba patola kamba with a modified interpretation of the patola kamba motif was acquired from Janggamangu many years ago by the late Babang Nati. Unfortunately we do not know the name of the weaver because Babang Nati died several years ago, taking its history with her to the grave. It was acquired from her widower, Windy Takanjanji.

A three-panel lau hiamba patola kamba woven in Janggamangu

Richardson Collection

The tradition of wearing the lau hiamba patola kamba continues to this day, with many female members of Diki Dongga’s large extended family continuing to wear these sarongs for important ceremonial occasions.

Some members of the extended Diki Dongga family dressed in their ceremonial lau hiamba patola kamba

The wife of one of the grandsons of Diki Dongga (right) wearing a lau hiamba patola kamba decorated with silver Dutch coins

In recent years there has been a revival in this pattern, which has been copied by many ikat producers in the Kambera region. Perhaps it is ironic that having copied the design of Gujarati weavers, the Diki Dongga family are angered that so many ikat binders have in turn copied their design, which in former times was exclusively restricted to their use.

Unwoven ikatted warps for two panels of a lau hiamba patola kamba on a frame at Prailiu, the traditional royal centre of the Kambera domain

A batch of new lau hiamba patola kamba for sale in the Hambala district of Waingapu

Regrettably some of the cheaper reproductions are chemically dyed and of poor quality.

A chemically-dyed lau hiamba for the local market

On the other hand the same Diki Dongga design has inspired some creative reinterpretations. The example below was woven in Prailiu by an unknown weaver about 40 years ago. It was collected from Tamu Rambu Ranggambani, the wife of the current King of Kapunduk, Tamu Umbu Kudu Praibakul, who was the only son of Tamu Umbu Kadambungu Nggeding (also known as Tamu Umbu Hinggu Praibakul) and his third wife, Mati Mbana, a former slave of the King of Prailiu. The royal family of Kapunduk have close links to the royal families of Prailiu and Rindi.

A two-panel lau hiamba decorated with a reinterpretation of the patola kamba motif

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Janggamangu Hinggi Patola Kamba

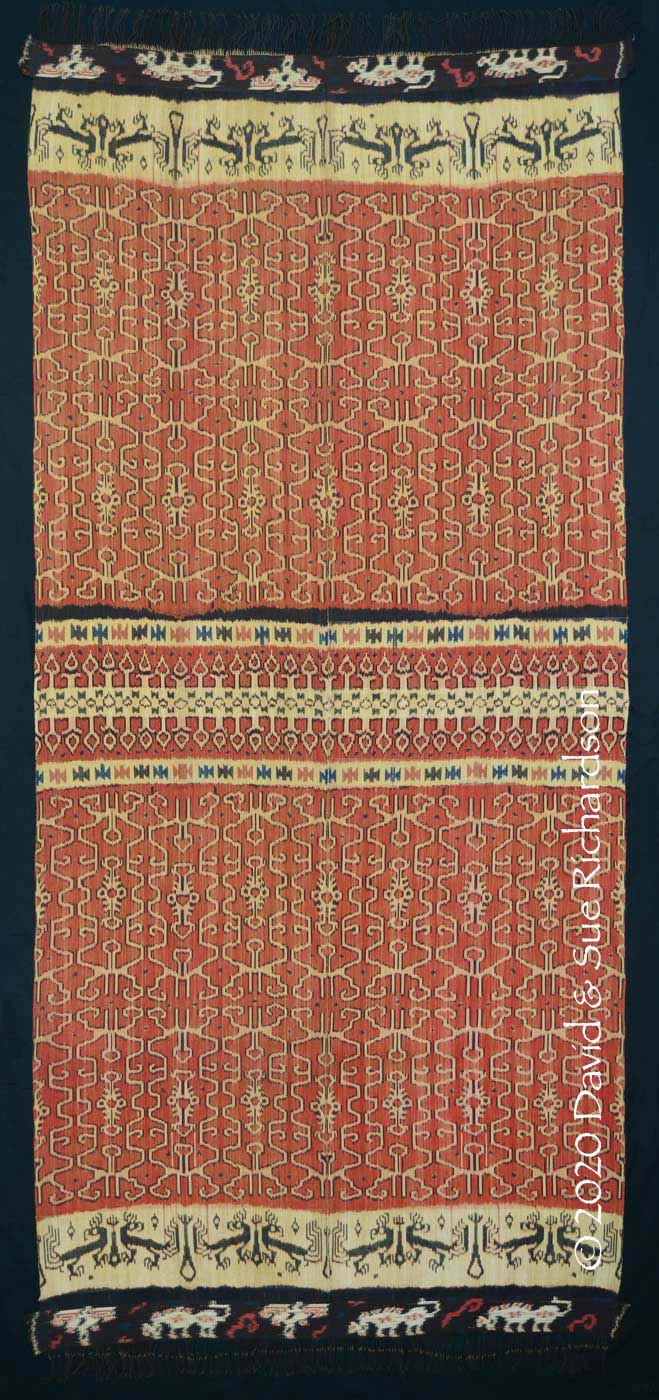

Hinggi patola kamba not only contain lattices of patola kamba motifs but also frequently include the associated patola terminal lateral band with its two sets of arrowheads.

The following hinggi patola kamba was one of a pair made in the 1950s. It was acquired from the collection of Umbu Lapoe Moekoe, whose house is located on the main Waingapu to Melolo road close to Janggamangu.

Umbu Lapoe Moekoe in 2019

Umbu Moekoe was trained as a medical doctor before becoming the third Bupati or Regent of East Sumba Regency, a position he held from 1977 to 1983. He acquired the pair of hinggis when he was younger, directly from Umbu Dongga’s family who were his direct neighbours. It is possible it was made by Rambu Dai Ata Luda. We in turn acquired the hinggi from Umbu Lapoe Moekoe’s first grandson. It has ikatted kabakils decorated with horses and chickens, which may well be later additions.

The hinggi kombu patola kamba from the collection of Umbu Lapoe Moekoe

Richardson Collection

The inclusion of pairs of black cockatoos (kaka) illustrates the close link between the Diki Dongga family and the nobility of Kanatang.

A somewhat similar hinggi in the Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection, Sanur, Bali, was made by Rambu Dai Ata Luda in the 1960s for her father, Umbu Diki Dongga:

A hinggi kombu patola kamba woven by Rambu Dai Ata Luda

Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection. Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

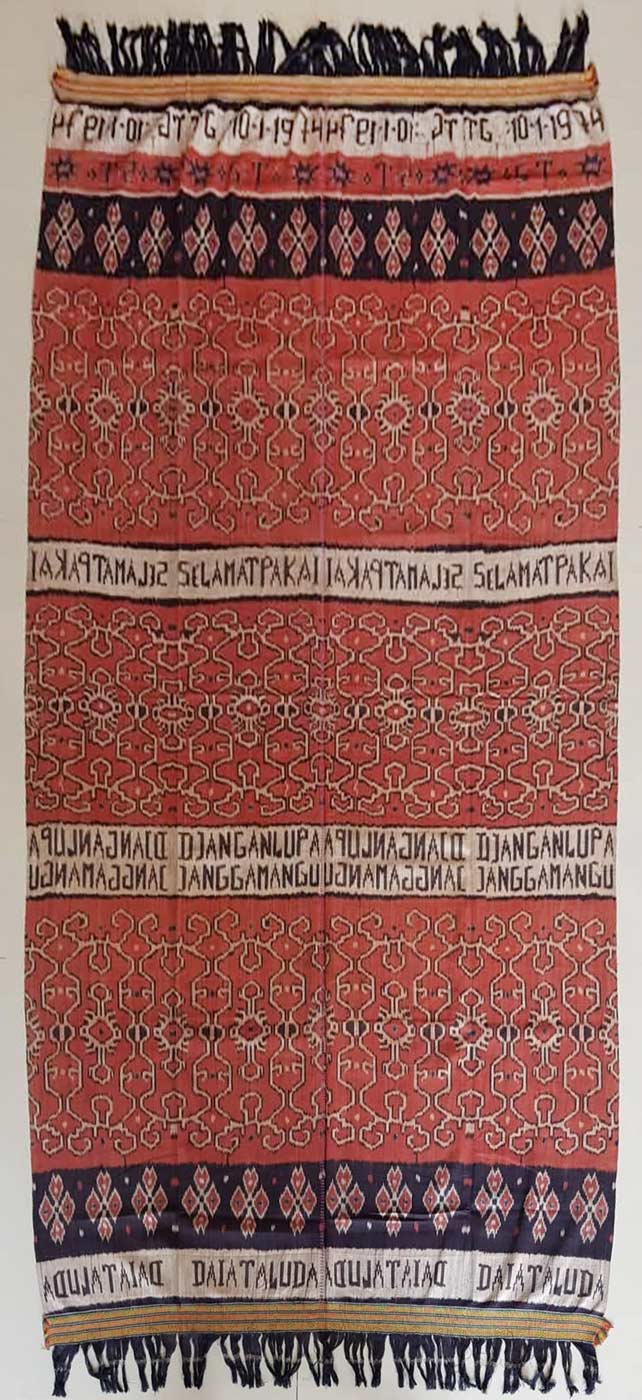

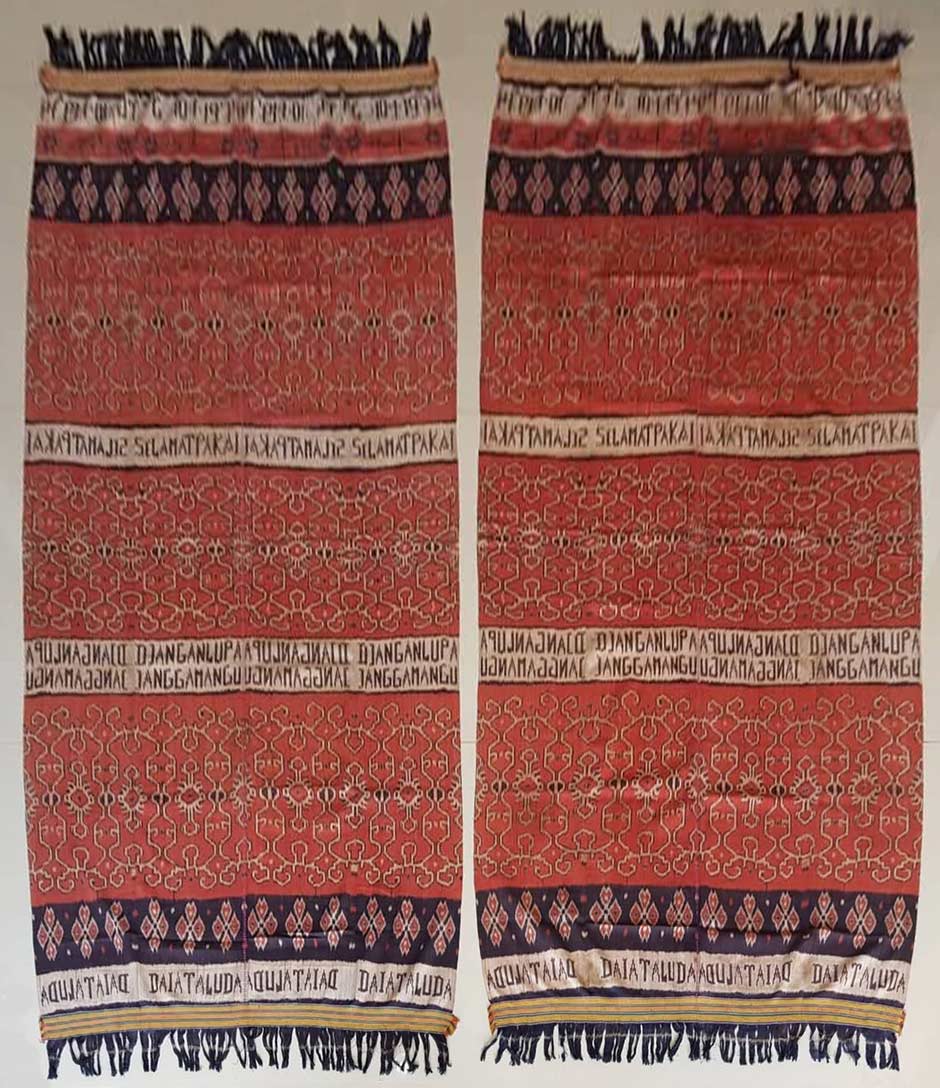

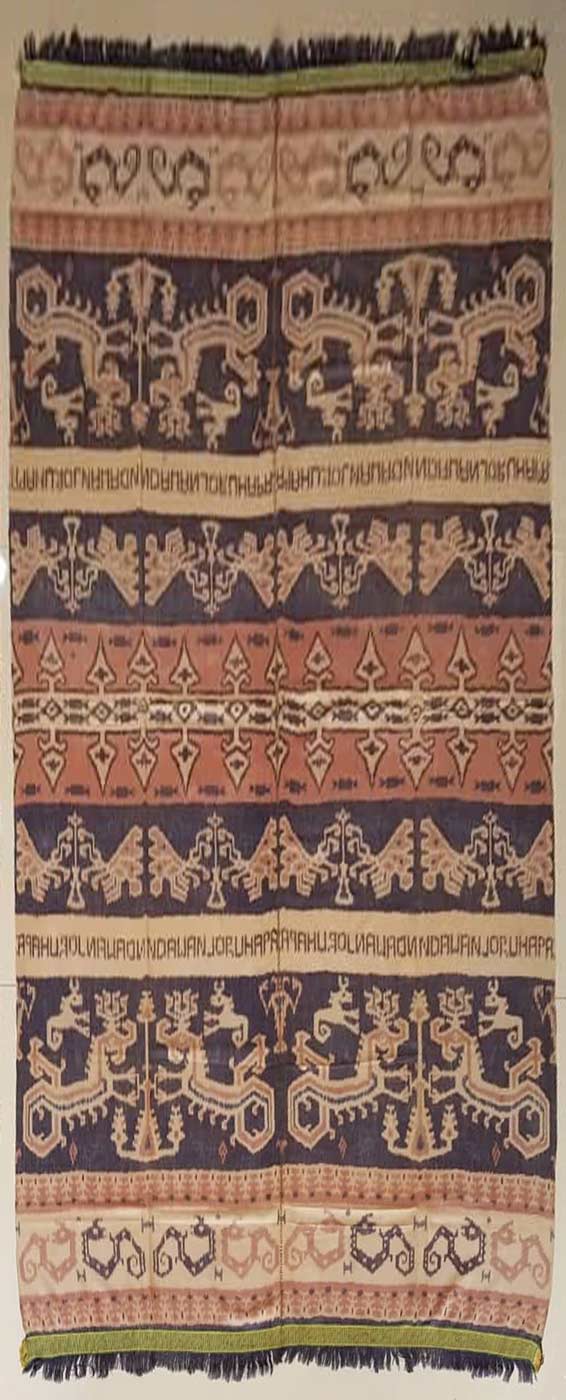

An unusual pair of hinggi patola kamba in the same collection were designed without the terminal band but included bands of black and white inscriptions giving the name of the weaver, Rambu Dai Ata Luda, the date 10-1-1974 and the phrases Selamat Pakai, 'Best wishes to the wearer‘ and Djangan Lupa Janggamangu, ‘Don’t forget Janggamangu’.

One of a pair of matching hinggi patola kamba woven by Rambu Dai Ata Luda

Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection. Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

The matching pair of hinggi patola kamba

Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

The two hinggis were specially made for Lieutenant Colonel Harsudoyo, an officer in the Indonesian army, at the time he left his position as Commander of the 6th East Sumba Kodim (Komando Distrik Militer) at Waingapu in 1974, having led it since 1967. From Sumba he moved to Bali to serve as the head of Wirasatya Command (Military Command 163), before being promoted to the rank of Major General in charge of Udayana (the 9th Military Regional Command named after a tenth century Hindu logician), which was headquartered in Denpasar and was responsible for the provinces of Bali, West Nusa Tenggara and East Nusa Tenggara.

Major General Harsudoyo, Udayana Command

Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

Hinggi patola kamba are still worn on ceremonial occasions by male members of the Diki Dongga family. A prime example is one of Umbu Diki Dongga’s grandsons, Umbu Yanto Diki Dongga, an important member of the East Sumba parliament. As a member of Partai Golkar, he was elected to the East Sumba Regional House of Representatives, DPRD, for the period 2014 to 2019. In 2019 he moved from Golkar to Partai Nasdem and was re-elected as a member of the East Sumba DPRD for the period 2019 to 2024.

Umbu Yanto Diki Dongga, one of the grandsons of Umbu Diki Dongga, with his wife Rambu Meri Gunawan in 2019. Reproduced with the kind permission of Umbu Yanto.

Umbu Yanto Diki Dongga, far left, his wife Rambu Meri Gunawan, centre, Umbu Ferdy, left, Rambu Yety Diki Dongga, second from right, and Rambu Halla, fourth from right. Reproduced with the kind permission of Umbu Yanto.

The following hinggi kombu patola kamba offers a more complex reinterpretation of the patola kamba pattern. It was one of a matching pair designed and bound by Agustinus B. Kilimandu, nicknamed Ama Seli, one of the top three modern ikat designers working in East Sumba today.

Ama Seli with a t-shirt bearing the patola kamba motif

Ama Seli was born in 1974 in the village of Haumara, situated just 500 meters before the twin villages of Tanau-Wukuramba, located in a cul-de-sac close to a bend in the Kambaniru River. He was trained by the late Umbu Pinggu Hambu, a preeminent East Sumba ikat designer. The quality of the very best modern cloths produced by Ama Seli and his few contemporaries frequently exceeds that of the older hinggis produced in the first half of the twentieth century.

A hinggi kombu patola kamba made by Ama Seli at Haumara

Richardson Collection

Modern lower quality versions of hinggi patola kamba frequently appear at Prailiu but they lack depth and vitality.

Above and below: two very similar hinggi kombu patola kamba with different kabakils on display at Prailiu

Return to Top

Other Janggamangu Hinggi

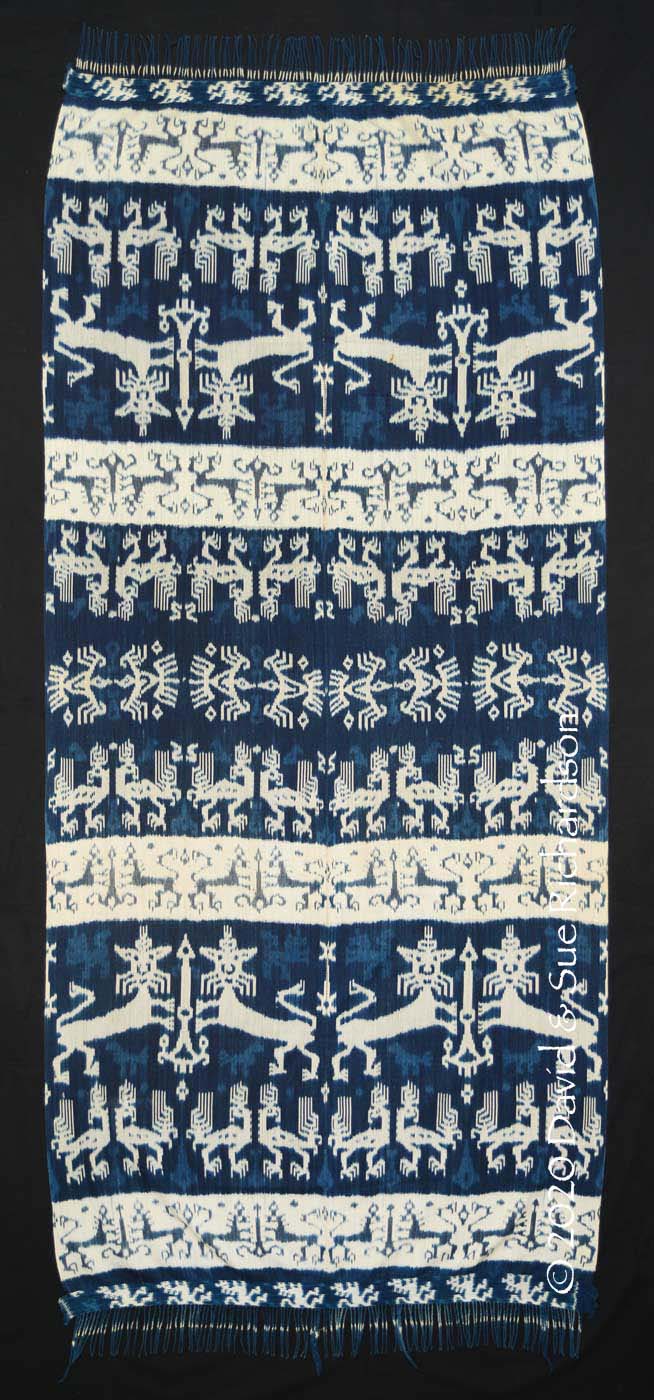

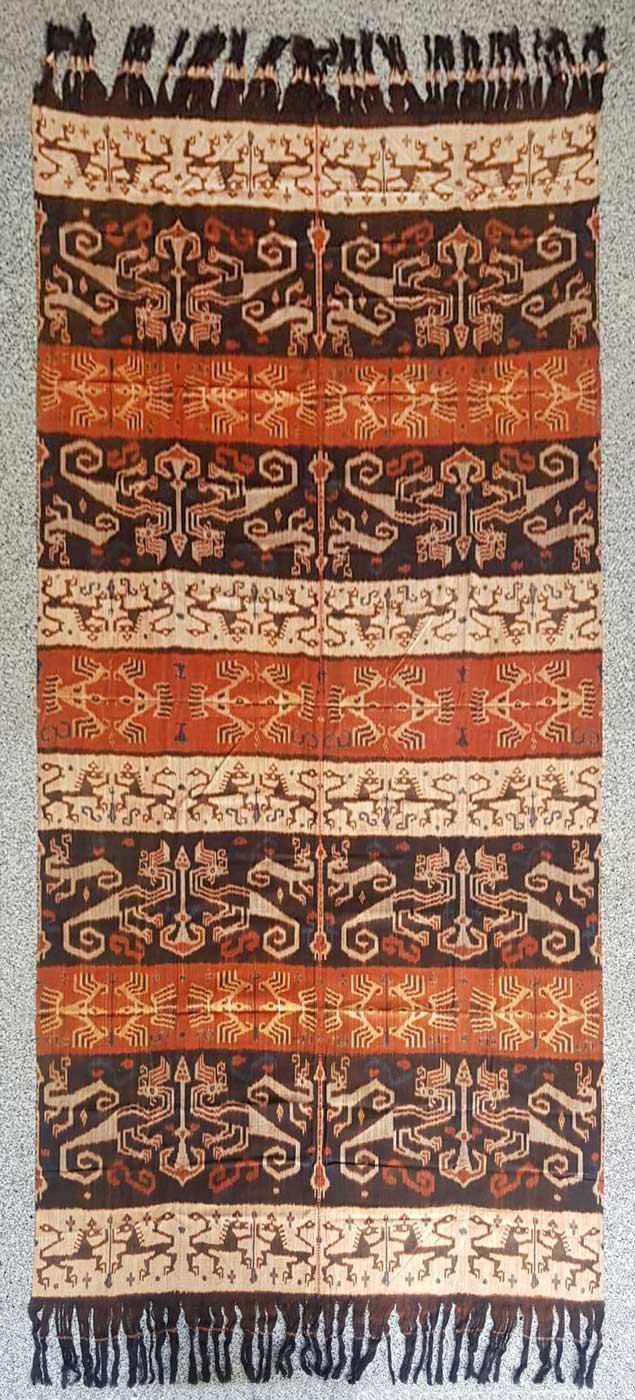

Not all hinggis produced by Umbu Diki Dongga’s family incorporated the patola kamba motif. The following very different hinggi kaworu was made by Rambu Dai Ata Luda, the daughter of Umbu Diki Dongga, about 45 years ago at Janggamangu. It was acquired by her neighbour, Umbu Lapoe Moekoe, the former Regent of East Sumba, shortly afterwards.

A hinggi kaworu made by Rambu Ata Luda

Richardson Collection

The flying bird motif was another speciality of Janggamangu. Once again, note the inclusion of pairs of cockatoos, always depicted with a downturned beak, a motif closely associated with Kanatang.

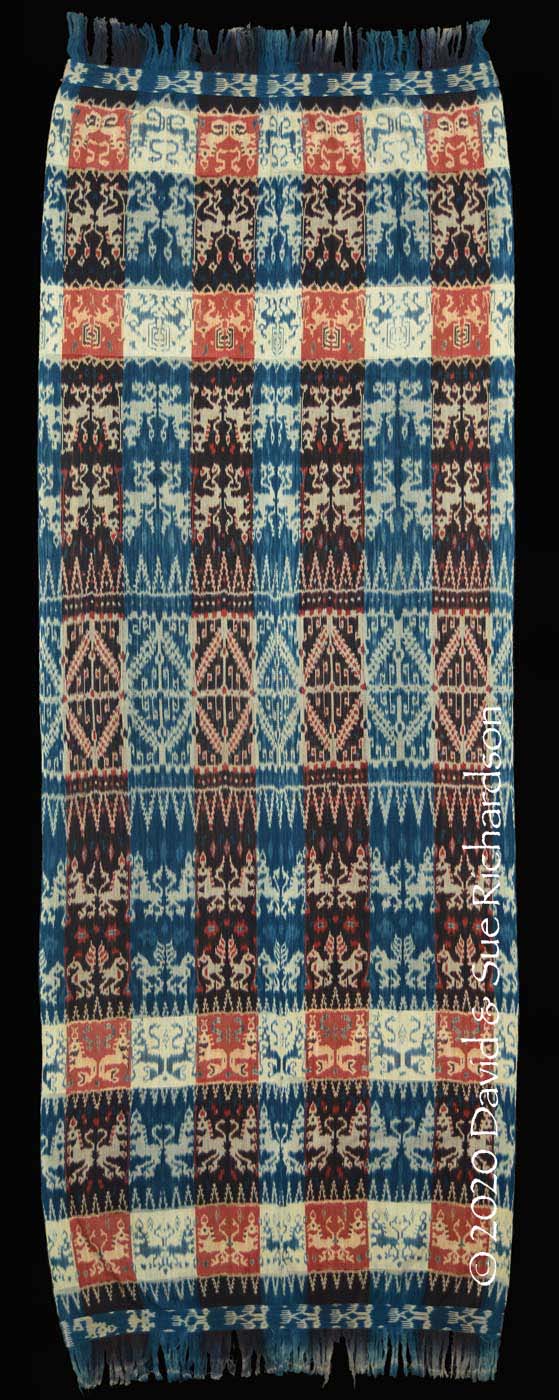

Rambu Ata Luda also made a matching pair of complex high-status hinggi kombu at some time prior to 1950. She gifted them both to Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha, the King of Karera, when he visited Umbu Diki Dongga at Janggamangu during the early 1950s. The quality of the ikat is extremely fine. The ikatted kabakil is decorated with the flying bird motif.

A hinggi kombu from the collection of the late Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha

Richardson Collection

Note the inclusion of pairs of cockatoos (kaka) along with pairs of rampant crowned lions (mahal uki) and pairs of fish-tailed nagas, a speciality of Janggamangu.

Tehu Tetur, the faithful equerry of the late Tamu Umbu Hunga Meha wearing one of the matching hinggis over his shoulder at Nggongi in Karera

The Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection at Sanur on Bali has another hinggi kombu woven by Rambu Ata Luda with a more classic design containing pairs of bird-like naga dragons with curled tails, another motif unique to Janggamangu. Note also the flying bird motif.

A fine hinggi kombu woven by Rambu Ata Luda at Janggamangu

Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection. Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

A much older hinggi kombu in the Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection was woven by an anonymous member of the Diki Dongga family at Janggamangu and designed with a single lateral terminal band from the patola kamba at its centre and two bands of text bearing the inscription NDAWAN JORUHAPA, possibly a person’s name. It too is decorated with pairs of fish-tailed naga dragons.

An old hinggi kombu made in Janggamangu

Kinga and Reni Lauren Collection. Image courtesy of Kinga Lauren

The creation of textiles including bands of text seems to be another local trait established by the Diki Dongga family. While Diki Dongga and his father stamped their mark on the turbulent history of East Sumba, his wives and daughters created an important local style of textile that still exerts a powerful influence over designers and weavers today.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Breguet, Georges, 2019. Sumba: Rites, Offerings and Sacrifices, Arts & Cultures, pp. 108-121, Musée Barbier-Mueller, Genève.

Bühler, Alfred, and Fisher, Eberhard, 1979. The Patola of Gujarat, vols 1 & 2, Krebbs AG, Basle.

Guy, John, 1998. Indian Textiles in the East from Southeast Asia to Japan, Thames and Hudson, London.

Hambuwali, Frederik, 2019. Personal communication.

Lauren, Kinga, 2019. Personal communications and liaison with Umbu Dominggus Diki Dongga.

Lee, Justin Lance, 1995. Participation and Pressure in the Mist Kingdom of Sumba; a local NGOs response to tree planting, Doctoral Thesis, University of Adelaide.

Metzner, Joachim, 1976. Die Viehhaltung in der Agrarlandschaft der Insel Sumba und das Problem der Saisonalen Hungersnot, Geographische Zeitschrift, vol. 64, quarter 1, pp. 46-71, Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden.

Mohanty, B. C.; Chandramouli, K. V.; and Naik, H. D., 1987. Natural Dyeing Processes of India, Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad.

Twikromo, Y. Argo, 2008. The Appropriation of National Policies by the Local Elite, The Local elite and the Appropriation of Modernity: A Case in East Sumba, Indonesia, pp. 131-134, Kanisius Printing and Publishing House, Yogyakarta,

Wielenga, Douwe Klaas, 1928. Oemboe Dongga het Kampong-Hoofd op Soemba – een Verhaal uit het Leven van een Heiden (Umbu Dongga the Head of a village on Sumba – A Story from the Life of a Heathen), J. H. Kok te Kampen, Kampen.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was first published on 23rd January 2020.