Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

The Use of Lau Wuti Kau

The History of the Lau Wuti Kau

Shell Appliqué in East Sumba

Simple Lau Wuti Kau

Lau Nggeri Wuti Kau

Lau Ketipa Wuti Kau

Lau Pahikung Wuti Kau

Lau Hiamba Wuti Kau

Halenda Wuti Kau

The Symbolism of the Anthropomorphic Figure

Anthropomorphic Figures on Moko Drums

Bibliography

Appendix - The Spurious Link with Dong-son

Bibliography to Appendix

Introduction

The lau wuti kau is a heavy ceremonial woman’s tubeskirt woven from hand-spun or commercial cotton that has been decorated with arrangements of couched cut seashells. Lau wuti kau are only found along the eastern coastal strip of Sumba Island in the Lesser Sunda Islands of eastern Indonesia. The main centres of production were Napu, Kapunduk, Kambera, Pau and Rindi. Lau wuti kau have always been highly valued, but are relatively rare. Today the finest examples are some of the most expensive textiles to be found on Sumba Island.

The majority of traditional lau wuti kau have a black or dark brown ground. After the lau was woven and sewn together it was hot-dyed with a mixture of tannins, and then mordanted in stagnant river or pond mud that was rich in ferrous iron (see our page on Mud Dyeing). This cycle was repeated until the lau became sufficiently dark in colour. The tannins were extracted from the branches and leaves of specific local shrubs and trees, some producing blacks and others producing browns. The shellwork was added later - in some cases many decades later. Generally in a two- or three-panel lau wuti kau the shell decoration is confined to the lower panel, the tail or kiku lau. The head (katiku lau) and middle (padua lau) are normally undecorated. However there are exceptions - see below.

A lau nggeri wuti kau mislabelled as a lau hada. Assumed to be nineteenth century. The panel from an old lau wuti kau has been sewn to the front of a later lau nggeri

(Image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)

The term wuti kau literally means ‘shell cut’. The term lau wuti kau is still used even if the shells are mixed with some beads. Umbu Kapita used the slightly different term laü utu kaü, which he defined as a tubeskirt decorated with siput or snails (1976, 244). The shells were not imported by the Dutch as stated by Eric Kjellgren, but harvested locally (2007, 238).

Many lau wuti kau are mistakenly labelled lau hada (Adams 1969, 84; Gittinger 1979, 162; Holmgren and Spertus 1989, 28, 30, 106; Maxwell 1990, 96; Forshee 1999, 44-45; Forshee 2006, 147). In the Kambera language a hada is a bead, normally the size used for a necklace, while a ketipa is a smaller bead. A lau hada is a tubeskirt embellished with beads arranged in the form of a free-flowing pattern, while a lau ketipa is embellished with a lateral band of continuous beadwork.

Lau wuti kau are relatively rare. Unfortunately many held in museum and private collections have been acquired through auction houses and dealers and therefore lack any provenance, greatly decreasing their value to the textile historian.

Return to Top

The Use of Lau Wuti Kau

Until about 1970 lau wuti kau could only be worn by women from noble families, the maramba. Common people were forbidden to wear them.

Lau hada and the considerably rarer lau ketipa were likewise restricted to the nobility. Skirts decorated with embroidery, lau pakambuli, were not.

Two wives of the late Raja of Karera, Umbu Hunga Meha, wearing modern lau wuti kau at their husband's funeral in 2015

Some insights into how lau wuti kau were made for the royal families of East Sumba was provided to us by Dioyonesius Haling, the most skilful of the few surviving wuti kau producers in the Regency. He was born in 1962 in the house of Tamu Umbu Nai Wulang, the Raja of Kapunduk, at Parai Bakul on the Kapunduk River. His father, who adopted the Raja's name Wulang, produced lau wuti kau for the Raja’s first wife, Tamu Rambu Mirinai Tinggi, who was the youngest sister of the King of Prailiu. The Raja of Kapunduk, who was the head of the ruling Ana Matjua clan, had three other wives - Ina Mbati, a former slave/servant to the King of Prailiu, Tamu Rambu Mirinai Ridja and Tamu Rambu Mirinai Babang, both belonging to the royal family of Rindi. Each of the queens loved lau wuti kau, and each one had her own individual specialist producer. The queens would wear these lau for formal or ceremonial occasions, such as visiting the Raja of Prailiu.

Dioyonesius Haling was taught how to sew at the early age of ten and made his first lau wuti kau for the royal family of Prailiu at the age of fourteen. He later moved to Kambera, where he continued to make lau wuti kau for wealthy women living in and around Waingapu, especially the wealthy wives of the local Chinese business community.

In the past, a fine lau wuti kau was an important component of the ritual gift exchange that underpinned an arranged marriage between two noble families.

In East Sumba the formation of a marriage alliance demands the exchange of gifts between the clans or lineages of the wife-givers and the wife-takers, the former always considered to be superior in status to the latter because they are providing the ‘gift of life’ – the bride – whose fertility will ensure the continued existence of the wife-taker’s lineage.

The wife-takers are obliged to give bridewealth, the wali, which traditionally consists of buffalo, horses, mamuli pendants, and chains of plaited metal wire. The payment of bridewealth secures the incorporation of the wife and her offspring into the husband’s clan (Forth 1981, 368). The wife-givers must make a counter-prestation, the lipoko, the size of which is determined by the size of the negotiated bridewealth – it is believed that the two prestations should be in proportion otherwise the marriage will not prosper (Forth 1981, 362). The counter-prestation mostly comprises textiles, both male and female, but also includes orange anahida beads, ivory armbands, and a woman's knife (Forth 1981, 359 and 361). Some of the most valuable textiles for the counter-prestation included hinggi kombu, lau pahikung and, in the case of a noble family, a lau wuti kau.

The exchanges follow a fixed sequence determined by negotiation. Payment of the bridewealth may begin long before the marriage takes place and may not be finalised until after the marriage. However the counter-prestation only takes place once the bride is delivered (Adams 1969, 49). The counter-prestation is also referred to as the mbola ngandi (literally: basket take), the basket that a bride traditionally carried to her new family containing her dowry of textiles and other valuables and the obligatory woman's knife.

It was a custom in the noble families of East Sumba that when a daughter was about to get married, her mother would gift her a lau wuti kau. This would become part of the mbola ngandi and after the marriage would remain the property of the bride. In time the bride might gift the same lau wuti kau to her own daughter. This is why one author claimed that such skirts were not worn, but formed part of the dowry (Anon. 1918, 11). However another suggested they were worn by a bride as she walked in procession to her husband’s family (Kuipers 1989 reported by Taylor and Aragon 1991, 223).

Lau wuti kau were sometimes worn by noblewomen at the funeral of another nobleman or woman and also by the specially costumed female ritual attendants, known as papanggang, who are assigned to the deceased from the family’s pool of slaves. They were also used to dress the corpse of a noblewoman, to cover or hang near the coffin, such as on the rung of the ladder that was placed nearby and symbolized her passage to the afterlife. It has been suggested that the practice of burying lau wuti kau with their owners may explain why such sarongs are relatively rare (Cutsem-Vanderstraete and Bremer 2012, 419). Alpert too thought that they were now rare (1977, 79).

Woman dressed in a lau wuti kau attending a funeral at Nggoni, East Sumba

As the power of the nobility has eroded over the last half century, many of the prohibitions related to the use of textiles such as lau wuti kau and lau hada have ceased to be enforced. Today any woman may wear a lau wuti kau, whatever her caste.

Return to Top

The History of Lau Wuti Kau

It is possible that along the coasts of Sumba, and indeed the other islands of Indonesia the embellishment of hand-woven cloth with shells was a very early decorative textile technique (Warming and Gaworski 1981, 141). Today we still find that shells are used to embellish sarongs, skirts and jackets on the islands of Borneo (the Iban and Maloh), Sumatra (the Kauer and Lampung), Flores (in Ngada, Sikka and East Flores), Pantar, Tanimbar, Babar and of course New Guinea. Seashells have also been used to embellish baskets in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Lombok, Timor, Ambon and other parts of Maluku.

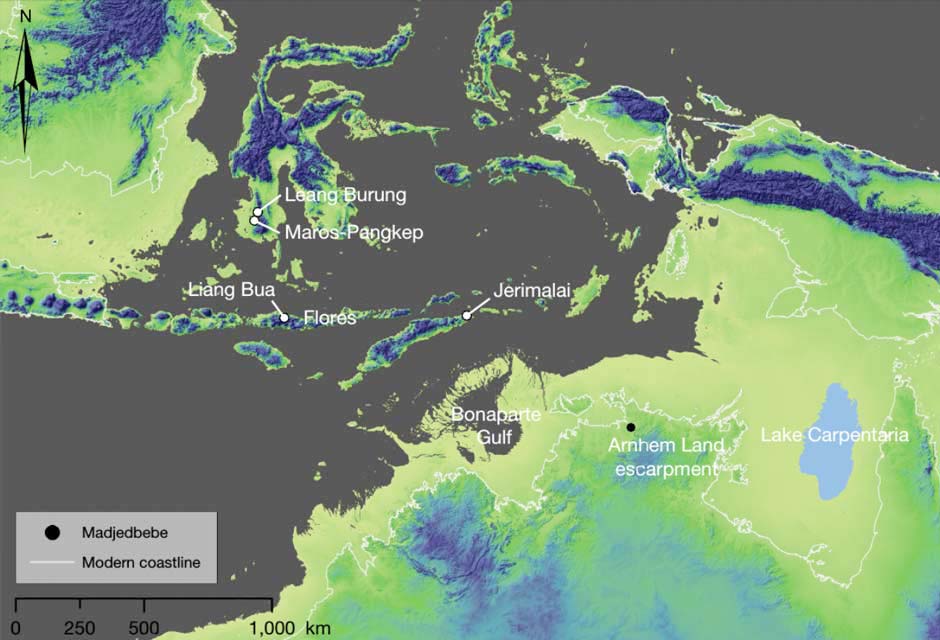

A fine lontar palm leaf chest decorated with shells, Alor Barat Laut, Alor Island

In eastern Indonesia the production of shell artefacts such as beads, fishhooks and cutting tools can be traced back for almost 40,000 years into the Palaeolithic. At the eastern end of Timor-Leste, for example, four archaeological sites have revealed 450 Oliva shell beads whose use dates back some 37,000 years (Langley and O’Connor 2016). Meanwhile on Gebe Island in Maluku archaeologists have recovered sophisticated flaked shell tools that were produced some 30,000 years ago (Szabó, Brumm and Bellwood 2007).

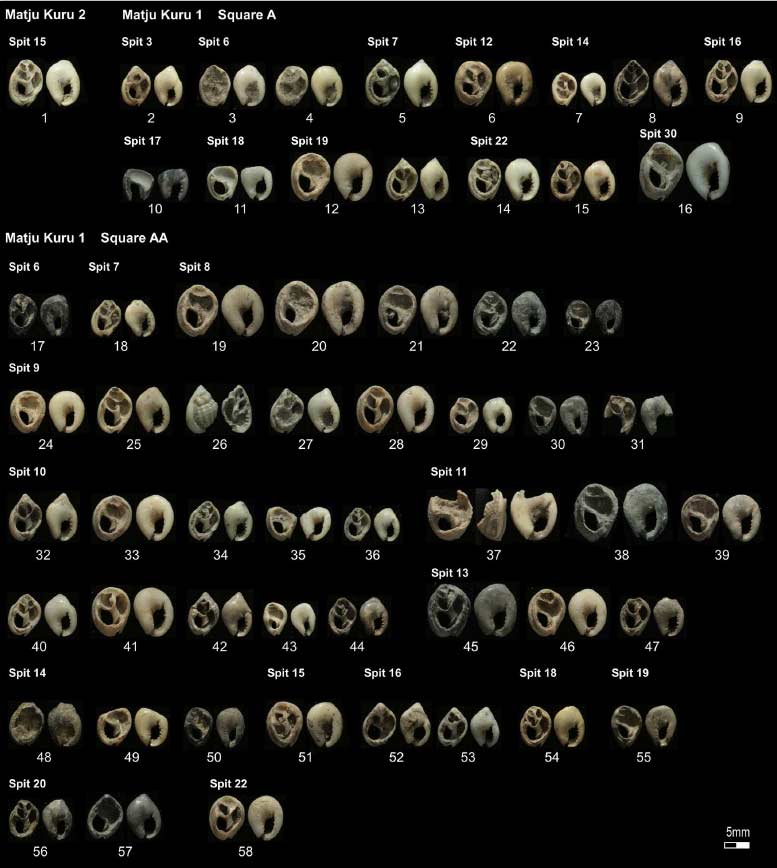

One of the most exciting recent discoveries has been made at four cave sites - Jerimalai, Lene Hara and Matja Kuru 1 and 2 - at the very eastern tip of Timor Leste (Langley and O’Connor 2015). Some 91 tiny Nassarius shell beads that were recovered from layers ranging in age from 6,500 to 2,000 years, bear traces of having been processed and used as decorative elements – specifically appliqué – on barkcloth textiles or other woven items such as baskets. The shells were first perforated and then pressure flaked to remove their dorsum. They were then all subsequently attached to a plant-based ground using a thread that has left wear and stain marks around the perforation. Amazingly the same manufacturing technique appears to have been used uniformly over a period of 4,500 years, showing a remarkably long and stable tradition of decorating artefacts by means of shell appliqué.

The 58 worked nassa shells recovered from Matja Kuni 1 and 2, Timor Leste

(Image courtesy of Michelle Langley and Sue O'Connor, ANU)

The date when the first Austronesian people migrated into this region is still hotly debated, but in Timor Leste is thought to have been around 3,500 years ago. Clearly the technique of shell appliqué was already well-established among the Melanesian inhabitants who greeted them. The spread of Neolithic maritime fisher-forager-traders across island Southeast Asia is strongly linked to the introduction of ceramics, novel forms of shell artefacts, barkcloth production and the weaving of cloth (Spriggs 2011, 523). In other words, the Austronesian immigrants who brought weaving to the Lesser Sunda Islands were equally accomplished at crafting seashells, as were the indigenous Melanesians they mixed with. It is therefore perfectly possible that shell appliqué was used to decorate some of the earliest textiles woven in the Lesser Sunda Islands.

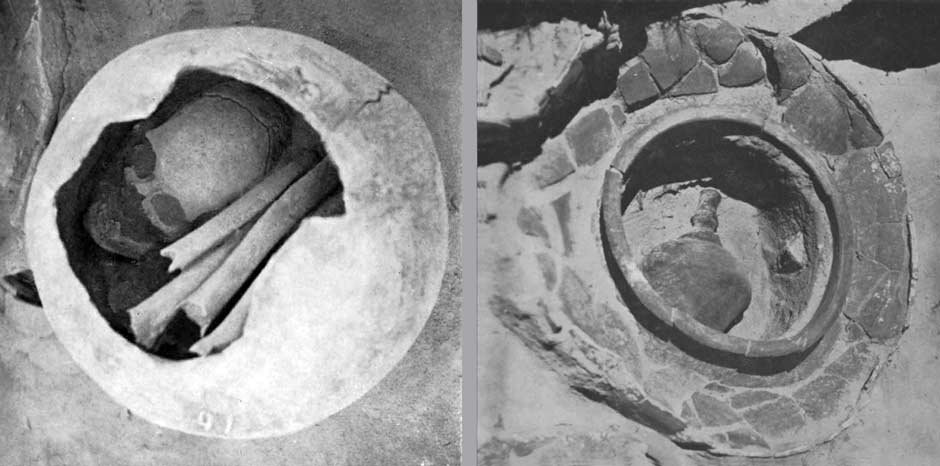

In 1908 a large coastal burial site was discovered at Melolo in East Sumba, which has since been the subject of numerous early excavations. Dating from the Neolithic or Palaeometallic (Early Metal) Era, it contained hundreds of ceramic urns containing skulls and long bones that had been inhumed some time after death as secondary burials. The occupants were a mixture of Papuans and Austronesians and were buried with grave goods that included shell beads, shell bracelets and rings, a shell pendant and ceramic spindle whorls. They clearly belonged to a society that could process shells as adornments and could spin fibre and therefore presumably weave. A somewhat similar burial site with ceramic jars containing worked shell ornaments and other shell artefacts has been located at Lambanapu, just south of Waingapu (Bulbeck 2017, 150). Interestingly both Melolo and Waingapu were important lau wuti kau producing regions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Finds from the Melolo urn cemetery. Left: Urn with skull and long bones; right: urn containing a funeral gift (Heereken pls 33 and 34, 1958)

A shell pendant recovered from the Melolo burial site in Umalulu, East Sumba

(Heereken fig. 23, 1958)

Historical reports show that lau wuti kau have been produced in East Sumba for at least the past two centuries. D. J. van den Dungen Gronovius, who had been appointed the Dutch Resident at Kupang in 1838, spent seven months on Sumba in 1846 - mainly in East Sumba. He noted that the local women wore a long, black, very narrow sarong of native cloth, which was usually embroidered on the lower side with small corals or covered with different coloured seashells, which ‘at a distance do not look disagreeable’ (1855, 289). He also recorded that Sumbanese clothing was generally very dirty, an observation supported by other European reporters who arrived later.

A similar picture was provided by Samuel Roos, who was stationed on Sumba from 1866 to 1873 as the first Dutch Kontroleur. He wrote that the women wore a cotton sarong or ‘laauw’, which was thick, coarse and narrow and of one length. It was black and sometimes interlaced with figures. It could also be embellished with small seashells and beads (1872, 13). The skirt was normally worn with the breasts exposed but could be pulled up over the head for protection against the night cold.

The Dutch representative Roo van Alderwerelt travelled extensively over the island in 1885. He was the first to record that certain specific items of jewellery and clothing were exclusively reserved for the high-ranking members of the nobility or maramba caste, the maramba wua kaba, also called the maramba bokul. If commoners, kabihu, or the lower nobility, maramba kudu, used them they would be confiscated and penalties would be imposed (1890, 593). This prohibition applied to women’s black sarongs decorated with shrimps, lizards and scorpions as well as to women’s sarongs woven with figures depicting birds, people or monkeys.

Five years later Ten Kate acquired a black lau hada decorated with beads in the Kambera region of Taimanoe, but did not say anything about Sumba women’s dress (1894, 551). Although the American naturalist William Doherty travelled across Sumba to study butterflies he at least left us a short reference about the use of shells on costume (1891, 150):

The Sumbanese, both men and women, wear a large loose mantle of Manchester cotton dyed black in the mud of the rivers. The women wear also a short black skirt, and on gala occasions a black jacket tastefully embroidered with beads and small cowries.

The minister Hendrik Hangelbroek briefly mentioned a lau wuti kau belonging to the wife of a Raja, which was decorated with shells in the shapes of shrimps, lizards and scorpions (1910, 47 and 51). He described it as a dress to be proud of, one which the woman could boast about to her sisters. Such sarongs could only be worn by her and the other princesses. Ordinary woman wore a narrow sarong that was made from extraordinarily rough and thick black cotton that left the breasts completely exposed and only covered the belly and thighs down to the knees. However in the cold it could be used as a blanket and pulled up over her shoulders.

Thanks to the assistance of the missionary Douwe Wielenga, the first detailed description of East Sumba women’s costume was provided by the talented Dutch artist Wijnand Nieuwenkamp (1923, 308-310). He arrived in West Sumba in May 1918 but did not reach Waingapu until August 1918. He stayed with Wielenga at Payeti, about 7km southeast of Waingapu.

Times were changing fast and men’s blankets (hinggis) were being produced for sale to people increasingly arriving into the port on KPM steamships. Nieuwenkamp discovered that in the past it was only the rich and influential that were permitted to wear decorated fabrics. The common man was forbidden to do so, the one exception being during important festivities when to add to the sense of occasion he was dressed in the textiles of his ‘lord’. At the same time, the common women were not allowed to produce coloured textiles, which explains why black was so widespread.

The women’s lau was made from a single length of cloth about 75cm wide and 175 cm long, divided into two and sewn into a tubeskirt. This was pulled up high under the armpits or worn with one part over the right shoulder.

After pointing out that sarongs decorated at the top and bottom with narrow bands of beads were called lau kapita, while those predominantly decorated with beadwork were called lau hada, Nieuwenkamp described a third type of sarong decorated at the lower end with a broad band of heavy beads about 30 to 40cm wide. The beaded patterns were mostly diamond-shaped and less commonly depicted men and birds. Called ‘kiri mbola‘ (bottom of basket) these weavings were not worn but formed part of the dowry. More specifically they were placed in the bottom of the basket (the mbola ngandi) in which the dowry is stored. Gittinger used the phrase pakiri mbola, meaning beginning of the basket (1979, 162).

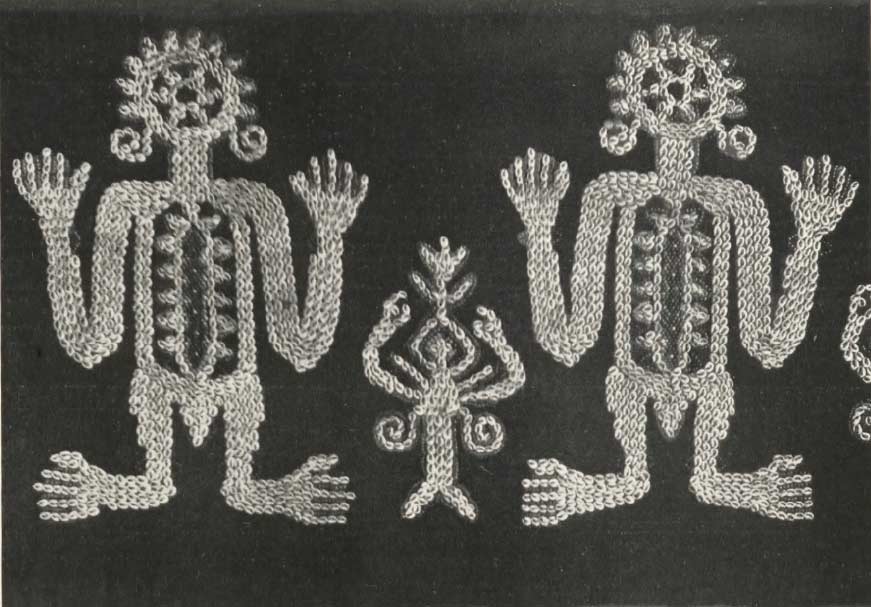

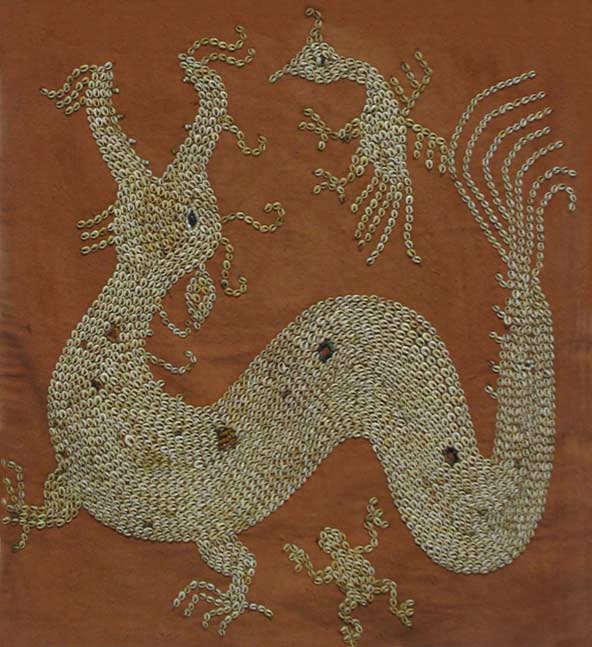

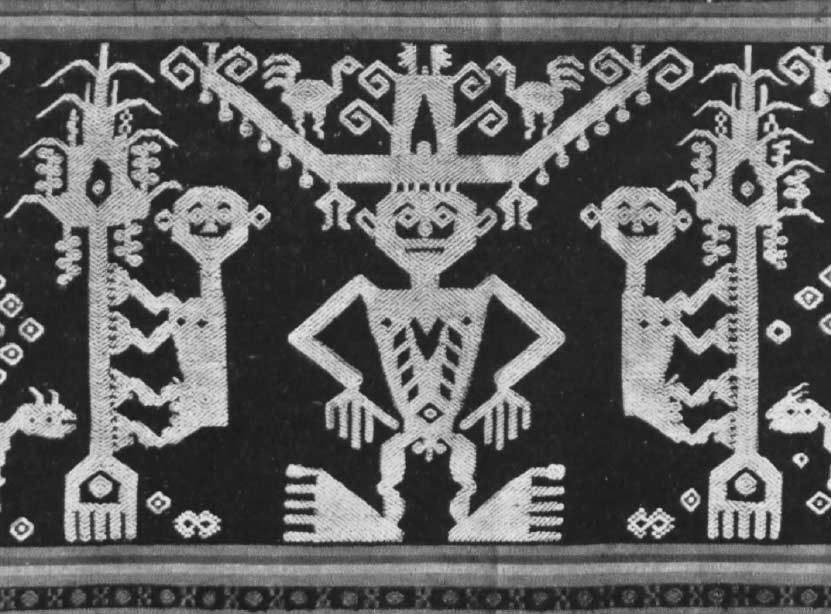

Shellwork on a heavy cotton lau wuti kau, described as a ‘kiri mbola‘. Erroneously said to represent two young girls and a shrimp. (Collected by Nieuwenkamp in 1919)

Horses and roosters on a red ground (Also collected by Nieuwenkamp in 1919)

In the past these ‘kiri mbola‘ had not been decorated with beads but with small shells. Later they were decorated with shells and beads, but at the time of Nieuwenkamp’s visit just beads. This was because it was now easier to buy beads than to collect the necessary shells and to grind them down to create the hole required for threading. Nevertheless there was at that time a great shortage of beads on the island because of the shipping blockade during the First World War, and therefore a sharp increase in their price.

At least one lau wuti kau was collected by Douwe Wielenga himself during his assignment at Kambaniru and later Payeti, which lasted from 1904 until 1921. He returned to Rotterdam with 71 hinggi and an unknown number of sarongs that are now held in the Wereldmuseum, Rotterdam.

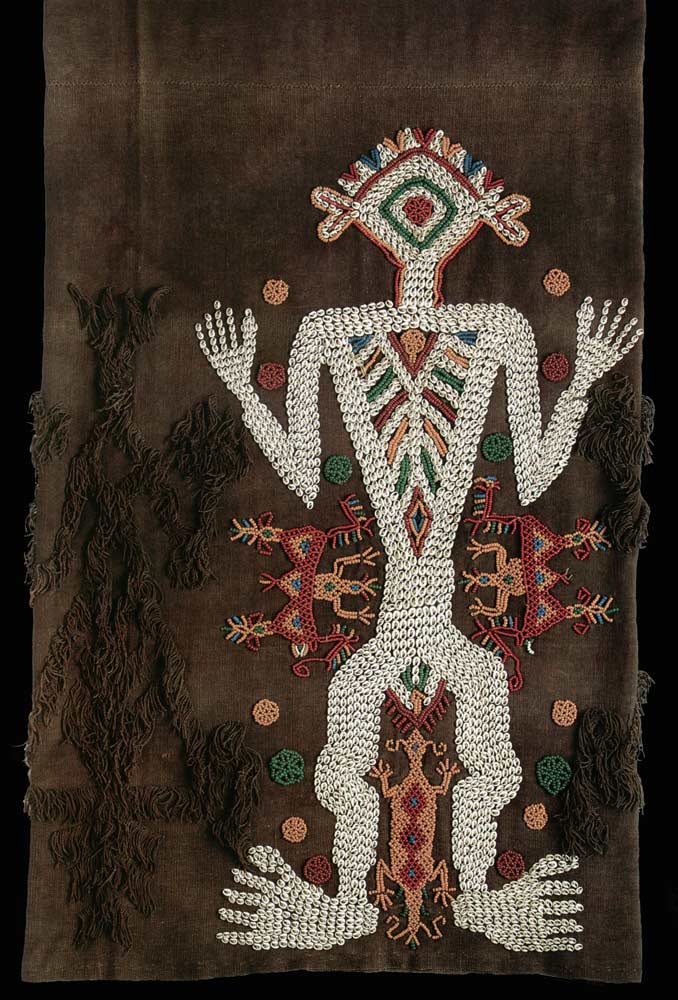

A hand-spun lau wuti kau (listed as a lau hada) collected by Douwe Wielenga in Lewa between 1904 and 1921. See Adams 1969, fig. 22.

It depicts a standing figure with a skeleton-like upper body of indeterminate gender. It could be a male wearing an elaborate atypical headdress or a female wearing a decorative comb (see Kartik 1998, 118). It is not clear whether it was made in Lewa or elsewhere.

During the two World Wars there was a huge increase in the production and commercialisation of men’s warp ikat blankets to satisfy the growing domestic demand from colonial officials on Sumba and Java and international demand in cities like Amsterdam and London. However it is doubtful if very much changed regarding women’s sarongs. In 1925 the Dutch naturalist K. W. Dammerman complained that the clothing worn around Waingapu was filthy and people were dressed in rags (1926, 52). When white clothing became dirty it was not washed but dyed black. Women wore a strong, heavy black sarong and were bare-breasted, only covering themselves for Europeans. These sarongs were normally undecorated apart from woven fringes, arranged diagonally one above the other. Others more fortunate had sarongs decorated with rows of silver coins or sewn figures of white yarn or white beads.

The anthropologist C. Noteboom, who worked in the East Indies from 1932 to 19,39 reported that on Sumba women wore a narrow two-panel tubeskirt (1940, 88 and 92). This was folded around the body either under or above the breasts and held in place by rolling the top folds inwards. In some cases it could be held up over one of the shoulders or held higher if the woman was carrying a load on her head. The uncovering of the upper body was still considered normal, although women had been made to feel ashamed with their breasts exposed in front of Europeans. When working in their gardens the women rolled their sarongs in such a way that only the navel to the knees was covered.

‘Simple’ women wore a black sarong made from coarse fabric while women ‘of good descent’ wore a sarong made from finer fabric decorated with white, and sometimes coloured, warps bearing the patterns of jumping horses, snakes, shrimps or fishes – in other words a lau pahikung. Others wore a plain dress sewn with shells or with half guilder pieces. In rare instances they added pieces of gold.

Post-independence, high quality lau wuti kau have continued to be made for the nobility, senior politicians and wealthy business people, especially the large local Chinese community who live in Waingapu and Melolo.

Since the 1960s Indonesia has witnessed a huge growth in tourism, with visitor numbers rising from 86,000 in 1969, to ½ million in 1979, to over 1½ million in 1989 and 5 million in 1996 (Cochrane 2009, 256). Many of these were tourists heading for Bali, seeking exotic souvenirs to impress their friends back at home. Modern beaded lau wuti kau perfectly filled the bill as examples of Indonesian ‘primitive art’, leading to increasing demand for the production of textiles decorated with shellwork on Sumba. This demand has since spread from lau wuti kau to crudely made, chemically-dyed sashes like the halenda pahikung wuti kau, which make more practical purchases as they can be used as table or bed runners.

Cheap modern halenda pahikung wuti kau made for the tourist market

Return to Top

Shell Appliqué in East Sumba

In East Sumba both shellwork and beadwork is done by men.

The raw material for shell appliqué is a small local variety of white Nassarius or nassa snail shell, known locally as a kambirru. The species is probably Nassarius pullus, known as the black nassa or ribbed dog whelk (Langley and O’Connor 2015). Belonging to the family Nassariidae, there are over 35 species of Nassarius mud snails. They all have tiny shells and are some of the most abundant molluscs found in Indonesia. They are sessile (stationary) gastropods that inhabit the intertidal zone of beaches and mudflats, emerging at low tide to scavenge for carrion. They spend the first one or two months of their lives as planktonic larvae, which is the reason for their wide oceanic dispersal (Pu, Lee, Zhu, Chen, Zhao and Zhan 2017).

In East Sumba the shells are collected from intertidal sandy beaches close to a river outlet. The shell is split to remove the dorsum or spire using sharp scissors or a knife or chisel or alternatively ground down with a file or grinder. The umbilicus of the shell is then pierced with a needle or awl.

Processing nassa shells in East Flores

A few villagers collect and split the shells commercially. They can be bought in bulk for very little money in places like Waingapu covered market.

Pre-split kambirru can be purchased on the market by the bottle full

The technique of sewing wuti kau involves pinning the sarong to an underlying support – in the past they used a large basket but today they use a wooden board or table. Traditionally the chosen pattern was marked on the surface of the lau using tacking stitches that were later removed. Today they use pencil or chalk. The shells are oriented so that their smooth white ventral surfaces face uppermost. They are then sewn on in rows, one at a time, using one or two stitches per shell. Today the embroiderers use a commercial single yarn which they sometimes ply to make it stronger.

Master wuti kau maker Dioyonesius Haling demonstrates how he couches shells onto a sample textile

The ventral surface of three wuti kau purchased from Waingapu market, length about 7-8mm

The anatomy of the shell is such that the split base has the shape of a figure 8, with a small hole at the top and a fragile bridge connecting the two sides. The fine threaded needle is passed through the underside of the textile and the small hole in the split shell and then passed back on the other side of the bridge. The needle is then repositioned and passed back through the underside of the textile to sew on the next shell.

The choice of motif is entirely down to the discretion of the maker. The motifs are not specific to the lau wuti kau’s use – if it is for a wedding or a funeral for example. The most commonly used motifs include the chicken, man, fish, naga or dragon, and crayfish.

If a wuti kau maker obtains a commission for a top quality lau wuti kau he will first search for an old undecorated lau to use as a canvas, preferably one that was mud-dyed. Lau nggeri are also a good choice, and are mainly found in Kapunduk and other places on the north coast. Pau and Rindi never produced lau nggeri. Unfortunately demand for high quality work is becoming less and less and the few remaining craftsmen left are forced to make a living by producing low quality work for the tourist industry.

Master wuti kau maker Kapenga Pala Manga with one of his simple cloths for the Bali tourist market

Kapenga Pala Manga who lives at the hamlet of Kayuri, close to the ceremonial village of Parai Yawang in Rindi, is also an accomplished maker of lau wuti kau. In the current absence of demand for high quality work he has no option but to produce cheap halenda that only take one week to finish. His work is sometimes traded to passing visitors by families in Parai Yawang. His brother Wili is also a wuti kau specialist.

A modern halenda hiamba pahikung wuti kau pinned to a table before the addition of the wuti kau to the chalked areas

A similar finished halenda hiamba pahikung wuti kau being offered for sale at Parai Yawang, Rindi

Cheap halenda on sale in Seminyak, Bali

The quality of a lau wuti kau very much depends on the artistic flair and technical skill of the maker. Some lau wuti kau look a complete mess, with cluttered compositions, poorly delineated motifs and an uneven arrangement of the parallel rows of shells. Others appear lifeless and mechanical, with stereotyped designs aimed to appeal to the commercial market. The finest lau wuti kau are dramatic pieces of art, often because of the simplicity and boldness of their design.

Return to Top

Simple Lau Wuti Kau

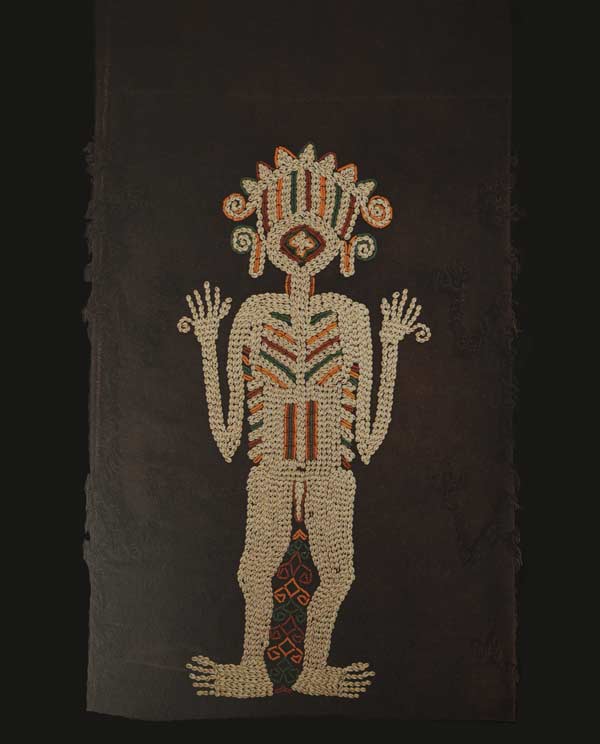

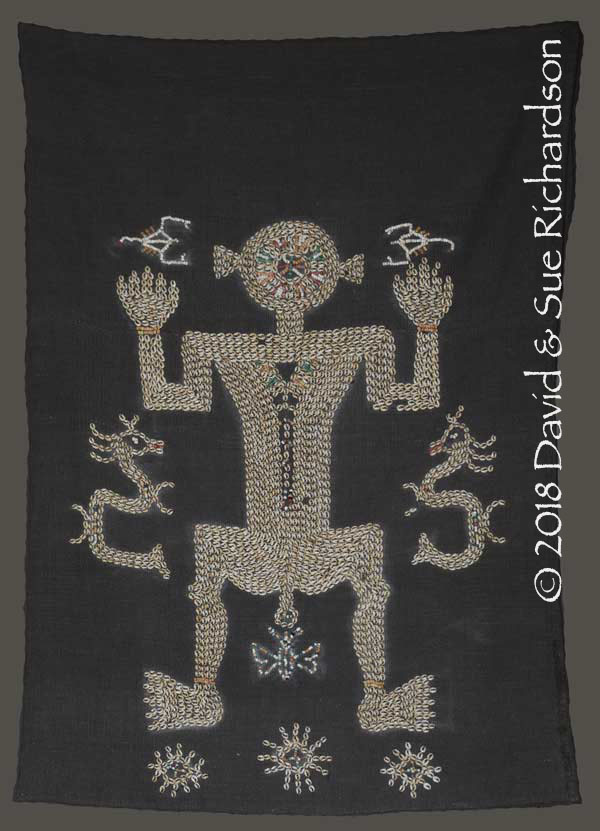

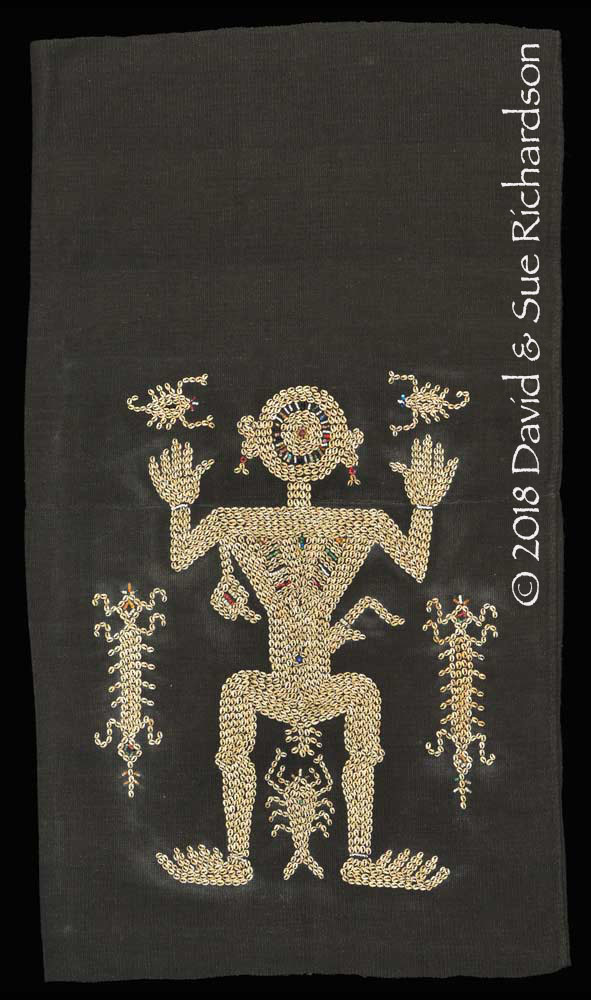

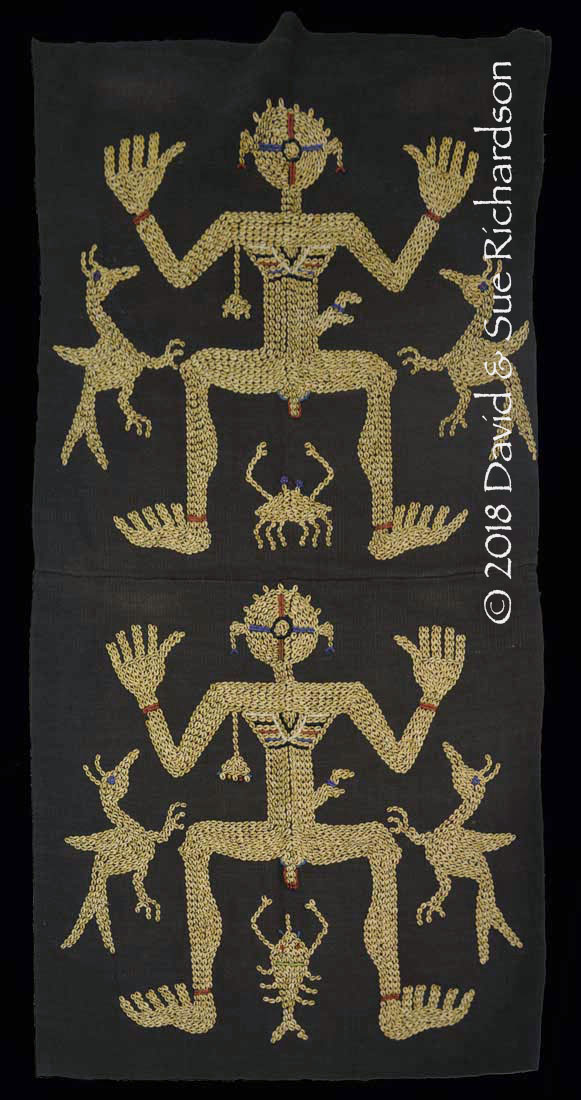

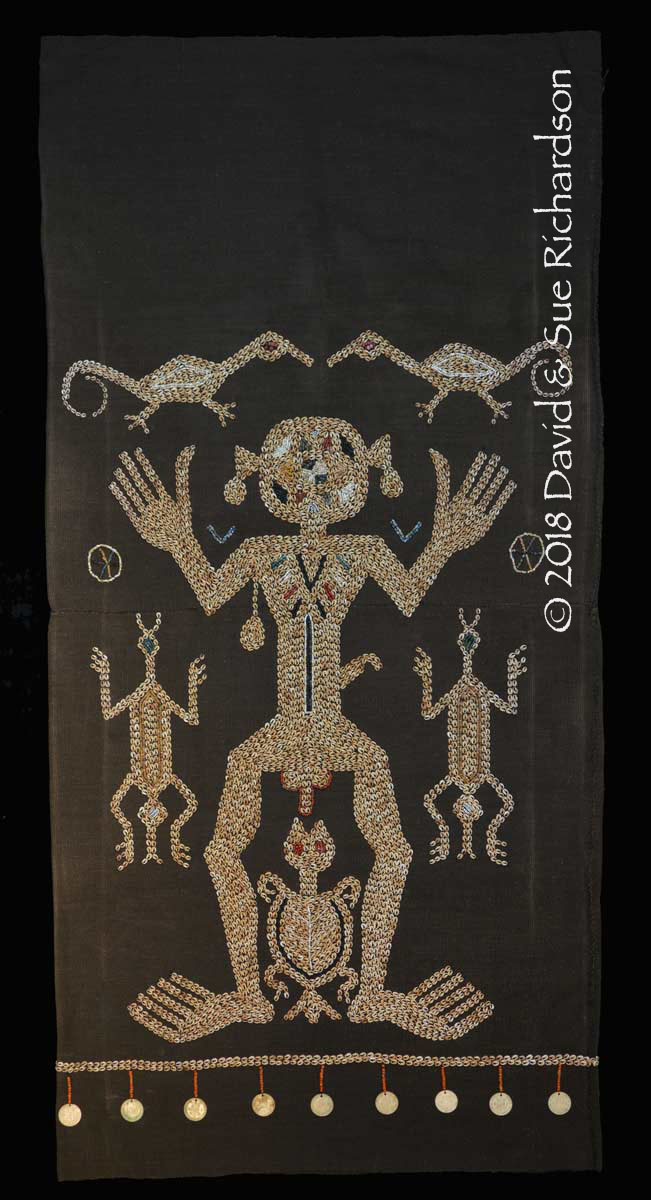

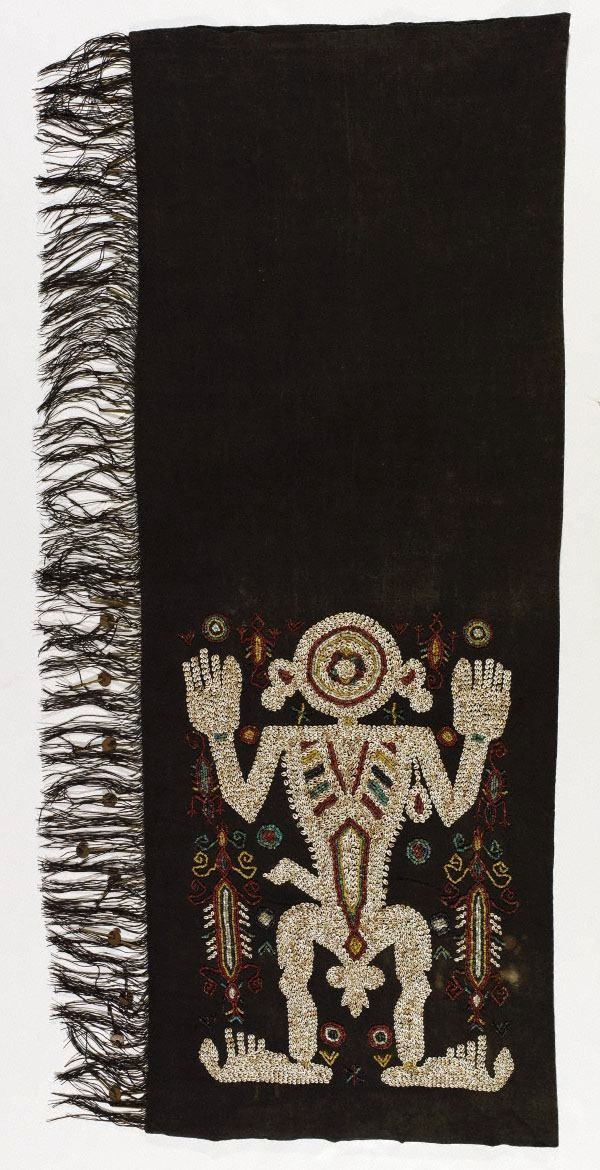

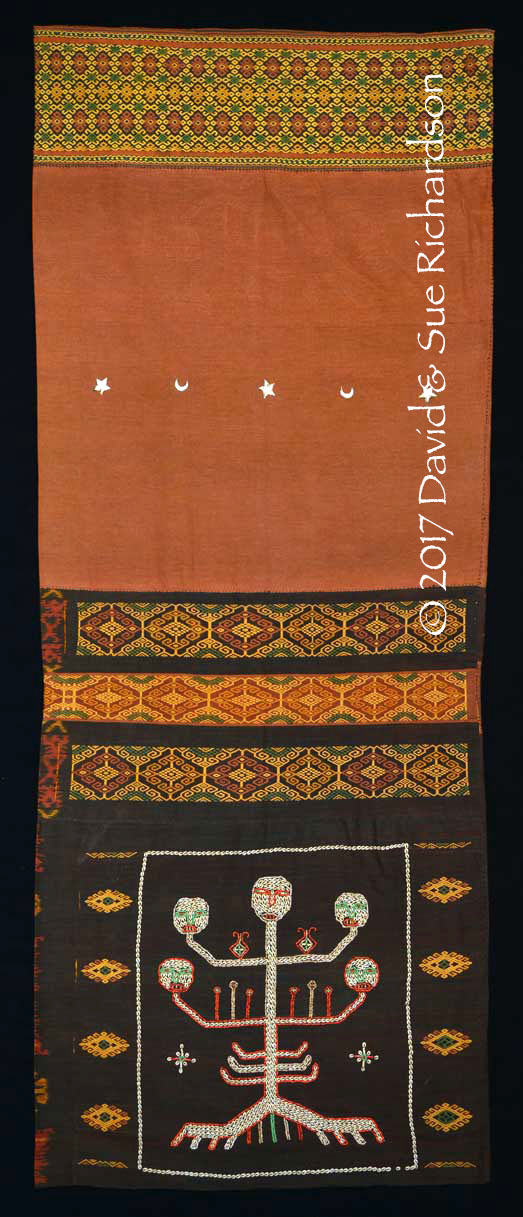

Traditional two-panel lau wuti kau are usually mud-dyed and have a plain upper panel, called the head or katiku lau, and a shell-embellished lower panel, called the tail or kiku lau. The most common shell decoration consists of a standing male anthropomorphic figure with raised arms, splayed hands and legs akimbo. Most commonly, a crayfish or crab is positioned with open claws below the figure’s genitals. Other secondary motifs such as lizards, snakes, insects, birds, seahorses and sometimes additional crayfish, normally flank the figure.

Lower panel of a lau wuti kau acquired on Flores in 1991

Richardson Collection

Lau wuti kau acquired in Bali in 1995. The remains of chalk marks outlining the pattern are still visible. Richardson Collection

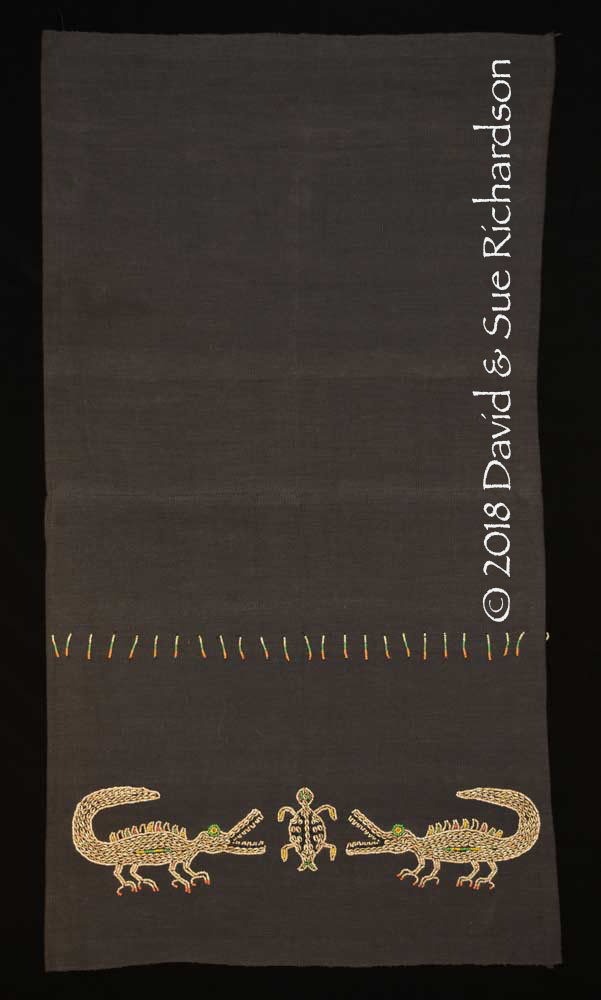

A lau wuti kau pakapihak with decorated upper and lower panels. Such an untraditional lau wuti kau was probably made for the commercial market. Private Collection, Sumba.

A naïve and understated lau wuti kau pakapihak made in Rindi in about 1960.

The motifs have been outlined using recycled antique glass beads. The crocodile symbolises power while the turtle symbolises wisdom. Richardson Collection

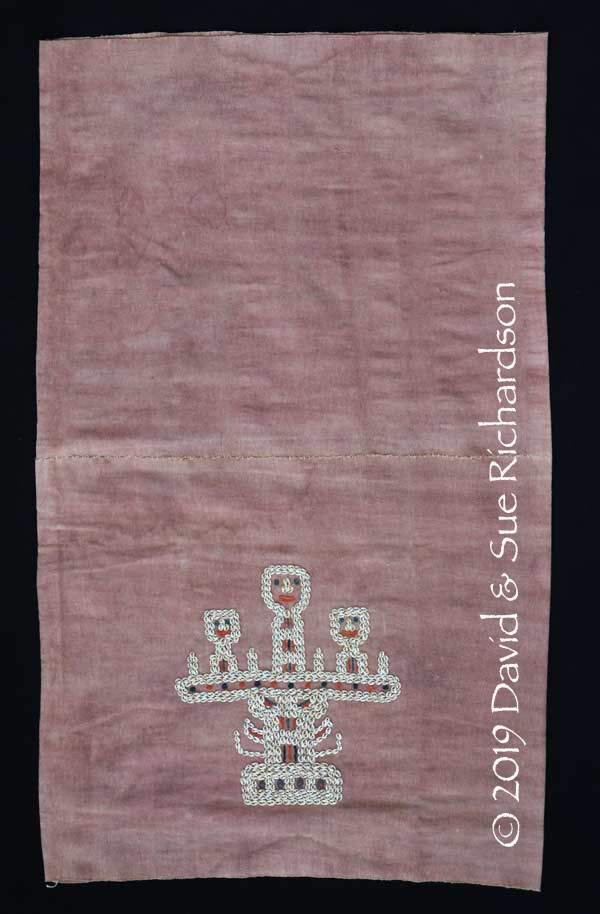

The smallest lau wuti kau in our collection was commissiond more than 50 years ago by Tamu Rambu Hudang, a noblewoman from Uma Kudu in Parai Yawang, Rindi. She died in 1997 and was buried in 2003, interned within the first grave in the centre of the village opposite her home. Tamu Rambu Hudang had it produced for her daughters, of which she eventually had four. The eldest is now aged 76 and the youngest 54. The lau wuti kau has been lightly dyed in morinda and is decorated with a depiction of the andung or skull tree that stood in the centre of Parai Yawang at the end of the ninetenth century.

A small double sided lau wuti kau commissioned over 50 years ago by Tamu Rambu Hudang, Parai Yawang, Rindi. Richardson Collection.

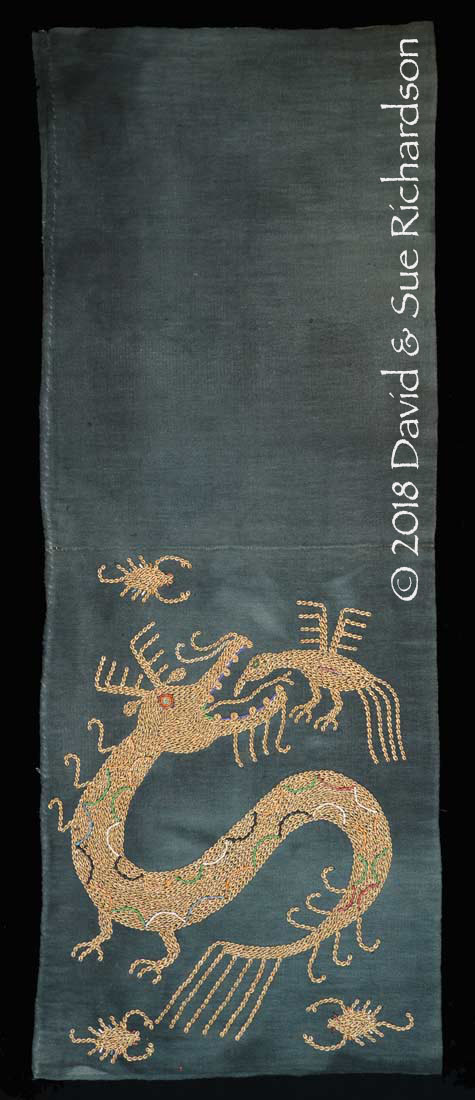

One of the most dramatic subjects for the lau wuti kau is the Chinese dragon, thought to have been initially inspired by the decorations on imported Chinese ceramics. China was already exporting large quantities of trade porcelain to Indonesia from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) onwards (Lam Pin Foo 2007). During the seventeenth century the VOC attempted to monopolise the import of Chinese porcelain and other ceramics throughout the Dutch East Indies (Volker 1954, 218). After the collapse of the VOC, Chinese pottery continued to be traded by Makassarese and other merchants, and perhaps by the Chinese themselves who came to Sumba in the first half of the nineteenth century to acquire slaves. When Dr Ten Kate visited Sumba in 1891 he identified the shards of Chinese porcelain plates, dishes and bowls in the derelict graves of local noblemen (1894, 571-572). During the 1960s and 70s many Chinese export porcelains were brought to Singapore by Indonesian antique dealers. Chinese ceramics are still found today in the treasuries of many of the wealthiest noble families of East Sumba. Interestingly, Monnie Adams recounted that Dr G. J. Onvlee was informed by a weaver that she had copied the dragon motif on her hinggi from a Chinese plate (1969, 148).

Detail of the lower panel of a lau wuti kau decorated with a Chinese dragon motif (Image courtesy of the Saskatchewan Craft Council)

A stunning lau wuti kau made in Rindi about 40 years ago and decorated with shellwork by Kapenga Pala Manga in Kayuri around 15 years ago. Richardson Collection

The large lau wuti kau pakapihak shown below was made at Kapunduk in Kabupaten Haharu, on the northeast coast of East Sumba. It is unusual for having a turtle positioned between the legs of the standing figure, a creature symbolically used to represent wisdom and by implication the queen. The bottom of the lau is decorated with a fringe of eighteen Dutch one-Guilder coins, suspended on short strings of highly valuable antique anahida orange beads. For the past half century the lau was in the possession of a wealthy Chinese business family in Waingapu.

A large and imposing lau wuti kau pakapihak made in Kapunduk, Kecamatan Haharu, around 50 to 70 years ago. The eighteen Dutch one-guilder coins date from 1929 to 1943.

Richardson Collection

One of the most dramatic lau wuti kau in our collection is very old and of uncertain origin. It was appliquéd by one of the great masters of shell work, Ama Retang (also known as Ama Nai Mandang), who throughout his career produced many lau wuti kau for the royal family of Rindi. He lives in a hamlet close to Parai Yawang and is now over 80-years-old. Ama Retang was responsible for teaching younger specialists like Kapenga how to produce lau wuti kau.

A large lau wuti kau pakapihak embellished with shells by Ama Retang in the domain of Rindi. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Lau Nggeri Wuti Kau

A lau nggeri is a plain lau decorated with a fringe. In the Kambera language nggeri means fluttering.

The fringe can be horizontal and placed in the lower or upper panel of the lau. Alternatively it can be inserted many times to create a pattern or motif, such as a horse - a common design in the Kapunduk region. In such lau nggeri the fringe should be added during the weaving process. This is achieved by placing short lengths of twisted fringe around single open warps before passing the weft. In a warp-faced cloth the fringe becomes concealed on the underside of the cloth. If the fringes are visible it means they have been added as an afterthought.

In some lau nggeri a vertical fringe is inserted into the side seam of either one or both panels.

A lau nggeri wuti kau with a vertical fringe, listed as a lau hada

(Image courtesy of The Art Gallery, New South Wales, Sydney)

Lau nggeri were a speciality of the Kapunduk region and other parts of the eastern coast located to the north of Waingapu. They were not made in either Pau or Rindi. The reason we see so many lau nggeri wuti kau is because wuti kau makers seek them out – old lau that are plain and undecorated are difficult to find, but lau nggeri are more common. Their aim is to find an example that has sufficient space to take the desired shellwork design.

Two sides of a lau nggeri wuti kau from Pau, dyed with yellow kayu kuning and decorated with a fringe, shells and glass beads (Private Collection, Sumba)

Some lau wuti kau are decorated with cockerels, which signify pride, courage and strength and are fearless defenders of their young. They symbolise the king, who likewise must bravely lead and defend his people. The cockerel also heralds the arrival of the new day, so also represents renewal and rebirth.

An elegantly simple three-panel lau wuti kau pakapihak from Napu, close to Wunga, in Kecamatan Haharu. It is over 100 years old. Mud-dyeing was once common in this region. Richardson Collection

Two sides of an old lau nggeri wuti kau obtained from Kapunduk that was decorated with shells and coins by the master craftsman Dioyonesius Haling 30 years ago. The cockerel symbolizes the king, as does the star. Richardson Collection

Despite being made around 80 years ago, the white lau nggeri wuti kau pictured below was first worn by the most senior of the three female papanggang at a major royal funeral held at Uma Bara on 31 October 1983. It was staged for the burial of five nobles, the most important being Umbu Nggaba Haumara, the Raja of Pau and head of the Watu Pelitu clan. Umbu Nggaba Haumara actually died in 1961 but was kept in his coffin for 22 years while the family gathered the resources necessary to stage the huge funeral.

Two sides of a white lau nggeri wuti kau made in Pau by a member of the royal family around 80 years ago. It was first worn at the funeral of the Raja of Pau, held at Uma Bara on 31 October 1983. Richardson Collection

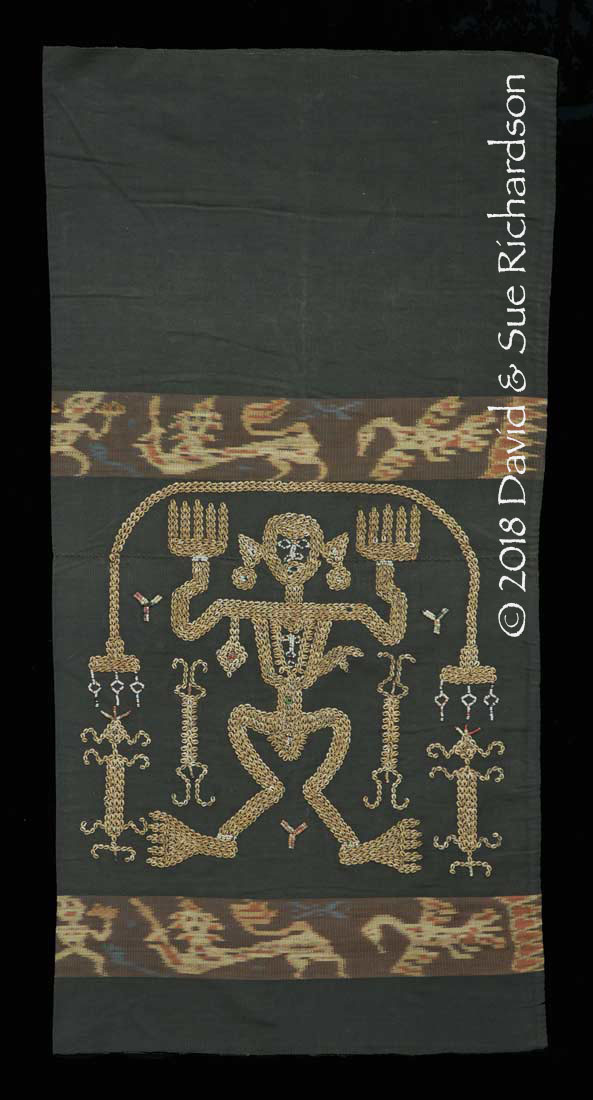

The last lau nggeri wuti kau in our collection is the most specacular. It is double sided with a marapu on one side and a lion on the other. This too was made by the a master shell work artist Ama Retang in a hamlet close to Parai Yawang in Rindi over 50 years ago. However the three-panel tannin-dyed lau nggeri is considerable older.

A long and dramatic lau nggeri wuti kau made in Rindi around 50 years ago by Ama Retang. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Lau Ketipa Wuti Kau

A very small number of lau ketipa wuti kau have been collected that are decorated with shellwork and a continuous horizontal band of beadwork. For an example, see Djajasoebrata and Hansen 1999, 65.

Return to Top

Lau Pahikung Wuti Kau

Jill Forshee reported that in the region around the town of Melolo, the two techniques of warp ikat and pahikung are often combined in the production of women’s tubeskirts, adding that they ‘are sometimes decorated with shells or beads’ (2001, 35). She illustrated this point with an image of two lau pahikung hiamba decorated with limited beadwork (Plate 12).

In our experience lau decorated with pahikung and wuti kau as opposed to beads are not common. The two examples in our collection only exist because of the extremely creative and highly talented weaver Rambu Ngana Harakay.

Rambu Ngana Harakay with one of her textiles, 2016

Born in Kabaru, about 2km from the important pahikung-weaving centre of Pau, she moved to Melolo after marrying a local Chinese man. She stopped weaving a decade or so ago to concentrate on her role as a priest. Rambu Ngana Harakay is rated by her peers as the finest weaver of pahikung and pahikung combined with ikat of her generation. In addition to being a talented weaver she was highly innovative, pushing the boundaries of traditional Sumba textile design into new areas. Much of her work was produced for wealthy Sumbanese collectors and for members of her own family. Local informants say that she has produced several other lau pahikung decorated with shellwork.

A lau pahikung hiamba wuti kau made by Rambu Ngana Harakay in about 1980. The crocodile superimposed with a human face is one of her important pahudu patterns.

Richardson Collection

A second lau pahikung hiamba wuti kau also made by Rambu Ngana Harakay, decorated with an andung or skull-tree. It was in the ownership of a mixed Chinese-Sumbanese family for the past several decades. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Lau Hiamba Wuti Kau

Lau hiamba (lau patterned with warp ikat) decorated with wuti kau are even scarcer than lau pahikung wuti kau. It is hard to find any examples in the textile literature.

The shell decoration on the example below from Rindi includes a strangely portrayed knock-kneed anthropomorphic figure with no obvious genitalia. It is flanked by insects or lizards and positioned below a long ceremonial woven kanatar chain with large decorative finials, a symbol of authority that was previously only worn by the highest nobility.

and

A lau hiamba wuti kau from the collection of a local Chinese businessman. It was made in Rindi roughly 50 years ago. Richardson Collection

Even rarer is this massive mud-dyed lau hiamba wuti kau, which is 105cm wide. It has been decorated with a lattice of motifs and four shell appliqé motifs - two mamuli pendants and two crayfish - arranged vertically. It is actually a lau payubuh, made to be worn by a noblewoman at her funeral as the outermost of all her dresses. It was bound by a woman who lives in the domain of Rindi and dyed by Karanja Ngana, the last remaining mud-dyer on Sumba Island.

The term payubuh refers to a woman covering her body with a sarong when she sleeps. A different word, palumbur, is used to describe covering with something else, such as a blanket; lumbu meaning to cover.

A lau hiamba wuti kau, known as a lau payubuh, made in 1977

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Halenda Wuti Kau

A halenda is a long narrow cloth, worn draped over the shoulder. They are not traditional but in recent years have been produced in increasing numbers. Many are decorated with a combination of warp ikat, pahikung and shell appliqué.

For a review of halenda pahikung please refer to the appropriate section of our webpage Pahikung - 2.

A high-status halenda pahikung hiamba wuti kau, estimated to have been made around 1960. The ikat is from the Kambera region and the pahikung comes from the vicinity of Pau. Size: 288cm by 69cm. Richardson Collection.

Return to Top

The Symbolism of the Anthropomorphic Figure

The anthropomorphic figure depicted on lau wuti kau is generally tightly proscribed. It is mostly male, carries a bag for sirih-pinang over one shoulder and a parang on the waist. It generally stands face and hands forward with raised arms and fingers and splayed legs and feet. The round head is normally featureless apart from a roundel or cross, the one exception being the ears from which hang earrings. Sometimes the chest is shown displaying the ribs, like in an x-ray. The genitals dangle above a creature – normally a crayfish or crab with raised open claws, but occasionally a butterfly, insect, lizard or turtle.

There are some exceptions to this template. In a few, the figure is shown with facial features or dressed in a lamba headdress. In a minority the figure has a female form and in one case is shown wearing what might be a hai kara jangga turtleshell comb.

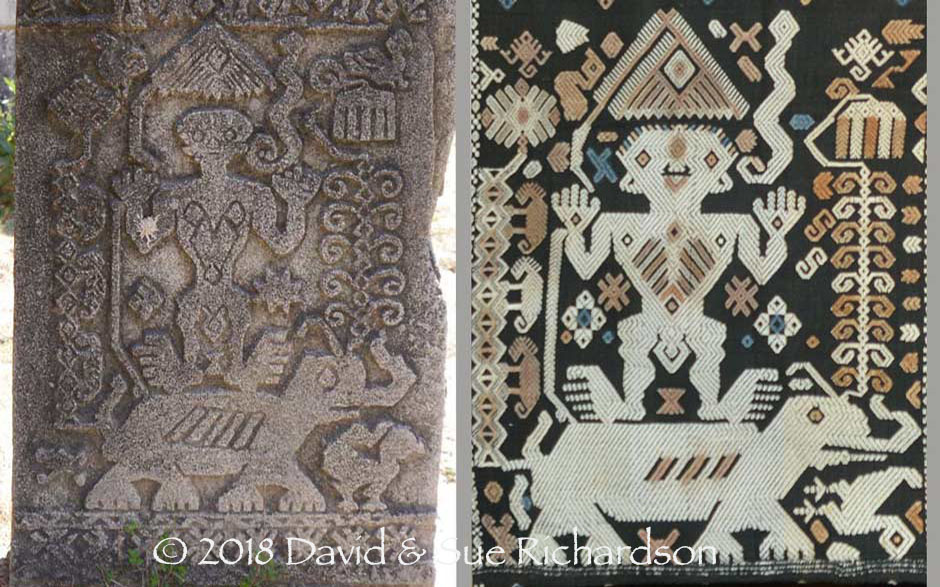

Similar figures are also depicted in warp ikat on hinggi kombu and in supplementary warp on lau pahikung (see Nieuwenkamp 1927). They also appear in lau pakambuli. However they are less commonly found on the stone carvings used to decorate the graves of the nobility, either on the richly carved upright penji or the sides of the dolmen. Having said this, Herman Ten Kate claimed to have repeatedly seen them on gravestones in 1891 (1894, 522). He described a penji on the grave of the Raja of Mangili at Kopa, close to the Mangili River, as being decorated with human skeletal figures with giant genitalia, a male on one side and a female on the other, surrounded by the images of fish, lobsters, crocodiles and horses (Ten Kate 1894, 583).

From our observations it is more common to find real human figures on Sumbanese graves, mostly involved in rituals or everyday activities, for example ratu and papanggang at a funeral, traditionally dressed nobles and warriors, men riding horses, men sacrificing buffalo, men playing gongs and women weaving and displaying textiles.

One exception is a short standing stone placed in the ground in the ceremonial village of Uma Bara in Umalulu. This is new and seems to be an oddity as it is too short to be a penji for a grave. Local people call the motif tau tunggung ngganja, a person on the back of an elephant, saying that it is inspired by an Indian patola. The carving was copied from a lau pahikung pattern belonging to one of the local royal weavers.

Left: the small stele placed in the ground at Uma Bara, Umalulu, with a figure riding an elephant and holding an umbrella; right: the corresponding pahikung pattern

Anthropomorphic figures also occasionally appear within paintings on the sides of the graves of noblemen.

Figures painted on the grave of Umbu Nggaba Maramba Amah at Kaliuda, Mangili

Figures on a grave in the centre of Yubawai in Kahaungu Eti

Robyn Maxwell believed that anthropomorphic figures were among the oldest symbols to be found in Southeast Asian textiles (Maxwell 1990, 17). They are widely found across the Indonesian Archipelago, in for example the tampan and pelapai of Lampung on Sumatra, the Dayak pua kumbu of Kalimantan, the mawa of Sulawesi, the ‘utang of Sikka, the betis of Timor, the homnon and lau of Kisar and the umban loincloths of Tanimbar. We have also discussed elsewhere the anthropomorphic carvings found throughout the South Western and South Eastern Islands of Maluku.

An early 19th century anthropomorphic figure carved on a stone 'waruga' sarcophagus at Sawangan, Minahasa, northeast Sulawesi. Photographed by C. T. Bertling around 1930.

Surprisingly the debate about the meaning of these ubiquitous front-facing human figures has been fairly limited. Langewis and Wagner put forward a rather contradictory view, firstly asserting that Indonesia had virtually no decorative art of its own until the arrival of geometric designs on Dong-son bronzes, then contending that religious and magical motifs, such as the forward-facing human figure, were taken from the Neolithic period that predated Dong-son (1964, 13-14). Warming and Gaworski likewise state that front-facing human figures are characteristic of the Neolithic (1981, 82). Hitchcock noted that these figures were closely associated with warp ikat, ‘a technique that may be one of the most ancient’ (1991, 161).

A few others have suggested that such figures originate from the Dong-son culture of the Red River delta of northern Vietnam, which flourished during the first millennium BCE (Fischer 1979, 9; Forshee 1996, 67; Forshee 1999, 42). We believe this extraordinary suggestion, again proffered with no supporting evidence, can be disproved – see Appendix.

It is far more likely that the origin of these figures lies within the Indonesian Archipelago. When and how we will never know because the decorative art of antiquity, expressed on wood, palm leaf, barkcloth and woven bast fibre, has long since perished.

The Cambridge-based linguist Roger Blench has taken an extreme position, which the Hawai’i-based linguist Robert Blust has subsequently criticised as an ‘adventure in freewheeling imagination’ (Blench 2012, 134-135; Blust 2017, 287-288). Blench proposed that the figurative art of the Austronesian-speaking world is characterised by two iconographic anthropomorphic figures. One is ‘a seated figure with either the arms crossed or held up to the chin, and generally with a serious demeanour‘. The other is ‘the seated figure with splayed legs bent at the knee’. We have no evidence to prove that either of these motifs were part of the original cultural package introduced to Island Southeast Asia by the Austronesian-speaking peoples but it is self-evident that they are widespread in specific regions of the Indonesian Archipelago today.

It is very tempting to label decorative figures that have a primitive appearance as Neolithic or ancient. And of course this might be the case - we have already shown how the early Papuan inhabitants of Timor Island were using shell appliqué long before the arrival of the Austronesians. However it is equally possible that the front-facing anthropomorphic figure is much more recent.

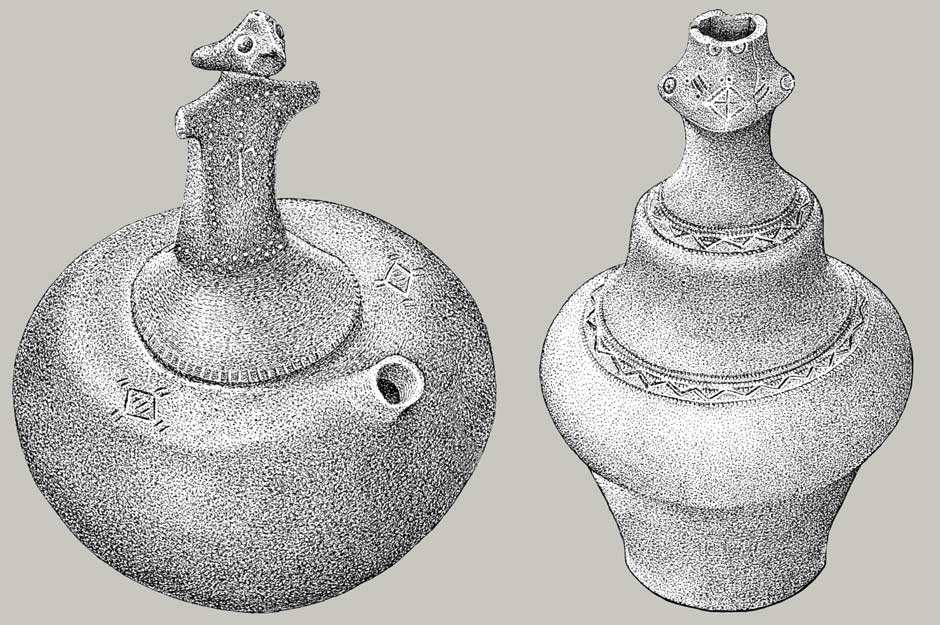

We are fortunate to have some insights into the decorative art of the inhabitants of East Sumba during the first millennium BCE, perhaps even from the time when prestige Dong-son bronze ware was arriving in the Lesser Sunda Islands from northern Vietnam (although none has yet been recovered from Sumba). We have already discussed the large coastal burial site at Melolo, close to the important weaving centre of Pau, a site that probably dates to the Neolithic or Palaeometallic (Early Metal Age, just a few centuries before or after the start of the Christian Era). Ceramic water vessels that were buried as funerary gifts next to urns containing the skulls and long bones of the deceased show a completely different stylistic way of depicting the human face and figure at that time (Hereekens 1958, 85-86; Bulbeck 2017, 154-157).

Finds from Melolo cemetery. Left: earthenware flask with human figurine and spout; right: earthenware flask with incised human face and geometric bands (Heereken figs 24 and 25, 1958)

A flask known as a kendi in the shape of a woman found next to ten skulls in the Melolo urn field (Image courtesy of the Museum Nasional, Jakarta)

It also seems that the later cult of constructing large megalithic tombs in which to inter the dead, especially the elite, may only be a relatively recent development on Sumba. According to Ron Adams, it is extremely unlikely that such tombs could have been constructed prior to the introduction of metals (2004). The oldest tombs that he could locate in West Sumba ranged in age from 100 to more than 450 years old, although how these dates were derived is a mystery. If Adams is correct, the distinctive iconography of Sumba Island, at least as expressed in stone carving, can only be centuries not millennia old.

After visiting Sumba in 1891, Herman Ten Kate pondered about the human figures with large genitalia depicted on certain hinggi kombu (1894, 552). He concluded, as did Roo van Alderwerelt, they were a fertility symbol. Describing them as ithyphallic (having an erect penis) he thought they might possess the power to repel evil. The skeletal appearance presumably symbolised death, while the enlarged genitalia symbolised eternal rebirth.

Wielenga noticed that there was a second type of anthropomorphic figure found on East Sumba textiles, with the arms akimbo but the arms and hands facing downwards (1921, cited by Adams 1969, 130). Maxwell believed this was another ancient depiction of the anthropomorphic form (1990, 128).

Anthropomorphic figure with hands on hip and a lamba headdress with mamuli pendants on a lau pahikung (Nieuwenkamp 1927, 262)

Wielenga believed the latter were tau or men (tau actually means person), while the figures with upraised arms were ana tau or suckling infants (ana tau means child person) lying with their arms bent upwards. We can dismiss this interpretation out of hand as the latter are frequently depicted with parangs and shoulder bags.

Warming and Gaworski claimed that lau pahikung featured three types of front-facing ‘Neolithic-style human figures’, which were no longer found on contemporary warp ikat hinggi (1991, 136-137). They identified them as follows:

- anatolomili or dancing man with both arms raised,

- tukakihu or standing man with both arms pointing downward, and the

- pahudu kalatahu or dancing man holding one hand up and one hand down.

Unfortunately this information is not correct. The expression ana tolumila refers to a skeleton, literally a person without flesh (tolu means meat and mila means poor). However the term is only applied to a marapu, which is normally depicted with the arms raised. The expression kahala tau refers to a body that is dead or a ghost. Hala means finished or complete, kahala means be finished, so a kahala tau means a body that is finished. Such a figure is normally depicted lifeless with the arms hanging downwards. The term tukakihu does not relate to a person or marapu at all but is the action of putting the hands on the hips, tuka meaning to put and kihu meaning hip.

These Kambera terms are not frequently used and are not all that well understood, so are best avoided. Whilst all three anatomical forms appear in lau pahikung, the first predominates in lau wuti kau. There seems to be a convention where in pahikung such figures are shown with facial features, but in wuti kau only rarely so.

Top row: ana tolumila and kahala tau. Bottom: we have yet to find an expression for this stance

Our informants in East Sumba believe that the anthropomorphic figure and associated crayfish or crab depicted on the lau wuti kau is a symbol of birth and rebirth. The figure itself represents a mythical ancestor, known as a marapu, the founder of a clan who now lives in the afterlife. The genitals represent the creative force of fertility and perhaps the line of patrilineal descent within the clan, while the crayfish or crab represent rebirth. This is because they each experience a form of metamorphosis – crustaceans moult, shedding their carapace as they grow larger. It is as though they complete one life before passing on to the next, just as each human dies and supposedly enters the afterlife to join their ancestors. A similar situation applies to the butterfly, which metamorphoses from the caterpillar. Likewise, many lizards shed their epidermis, some casting off their entire skin in one piece (Wilson 2012, 130). Turtles, on the other hand, do not shed their carapace, although they do sometimes shed the outermost scutes or individual plates that make up their shell (Fergus 2007, 2).

Local people use the expressions kurangu laku dalung, crayfish step backwards, and kura ma pa njilung, the crab is changing its shell.

On Sumba the marapu are the pre-eminent ancestors of the clans, usually the earliest or founding members of the clan and almost exclusively male (Forth 1981, 88). According to Forth they are descended ‘from an original group of beings conceived in the sky and placed on earth by God’ and consequently mythical. The people of East Sumba believe that they cannot communicate with their God directly but only indirectly, using their ancestors as intermediaries. The marapu are tutelary, acting as protectors or guardians, but they can also be vengeful if they are disrespected or if traditions are broken. When death, illness or some other misfortune occurs it is either because of some transgression against customary law (adat) or because the marapu have been insufficiently appeased. The marapu do not punish the members of their clan directly, but enact retribution by withdrawing their protection, allowing the inherently malevolent forces of nature to take their course.

It is possible that the depiction of the occasional female figure on a lau wuti kau represents the female marapu of a particular clan. For example, in Rindi they believe the Kanilu clan was founded by a female ancestor (Forth 1981, 88).

The lower panel of a messy lau nggeri wuti kau, described as a lau hada, decorated with a female anthropomorphic figure on one side and a male figure on the other.

(Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The interpretation of the frontal representation of a human figure as an ancestor or marapu has already been recognised by several writers (Hitchcock 1991, 161; Forshee 1996, 198; Tilden 1997, 57; Quincy 2001, 46). Robyn Maxwell was less specific, merely saying that it was possible such figures represented supernatural beings (1990, 128).

Possibly a lau wuti kau decorated with this symbol of birth and rebirth may have been seen as a talisman during the funeral of a noblewoman, facilitating her passage from the living world to the afterlife.

As is the case with many traditional motifs, modern weavers will frequently reinterpret their meaning. Jill Forshee recounts how that some of her contacts on Sumba thought the anthropomorphic motif had emerged as a jest against men, the crayfish and crabs performing an act of castration (1996, 198). This surely cannot be so because the same creatures are also positioned between the legs of female figures (see Holmgren and Spertus 1989, 28-31). Others believed a woman from Pau/Uma Bara (so-called ‘Hawewa’) invented the motif a long time ago to humble her husband.

In the opinion of the men who produce these standing wuti kau figures, Dioyonesius Haling describes them as a tau, person, but believes in some cases they represents the king rather than an ancestor. On the other hand Kapenga Pala Manga refers to the standing figure as a kapala roda, the head of a wheel, because the round head with its superimposed cross looks like the hub of a wheel, a roda. However he recognises that symbolically the figure represents an ancestor, who he describes as the manusia dulu, the first human being.

Return to Top

Anthropomorphic Figures on Moko Drums

One other possible although unlikely source of inspiration for the image of the standing anthropomorphic figure found in the Lesser Sunda Islands are the reliefs cast onto the sides of moko bronze drums. The latter are only found in Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands but in some places, such as Alor, in great numbers (Bintari 1985).

Bintari classified such moko drums into four categories (1981):

- Type I (Pejeng-type) are decorated with an eight-pointed star in the centre of the tympanum and a human face with bulging eyes on the sides.

- Type II (Classical-type) are decorated on the sides with temple-like motifs, shadow-puppet figures, the heads of monsters, floral motifs and spirals.

- Type III are decorated on the sides with western-inspired motifs like lions, crowns, grape vines and grape leaves.

- Type IV are decorated on the sides with human figures, animals, floral and geometric motifs.

Some earlier bronze mokos were manufactured on Bali, where fragments of stone bi-valve moulds for their casting have been recovered in Manuaba in central Bali (Soejono 1971, 84). They have been assigned to the Palaeometallic Era (Ardika 1987, 36).

The largest numbers of mokos occur on Alor and Pantar, the oldest and most highly valued having been buried underground and recovered sometime later (Vatter 1932, 238). They are consequently known as moko tana. However the majority of moko drums are reproductions that were cast in large numbers in north-eastern Java for commercial gain (Nieuwenkamp 1919a; Vatter 1932, 239). We know that the manufacture of such drums at Gresik near Surabaya has been active since at least 1860 (Huyser 1931, 279). These later mokos were imported into the Lesser Sunda Islands by Chinese and Makassarese merchants in great numbers (Vatter 1932, 239). Some 2,164 mokos were registered on Alor in 1916, but far more were probably concealed from the authorities (Nieuwenkamp 1922, 75).

Others mokos have been found on Flores, Adonara and Lembata but, as far as we can tell, none have yet been found on Sumba Island.

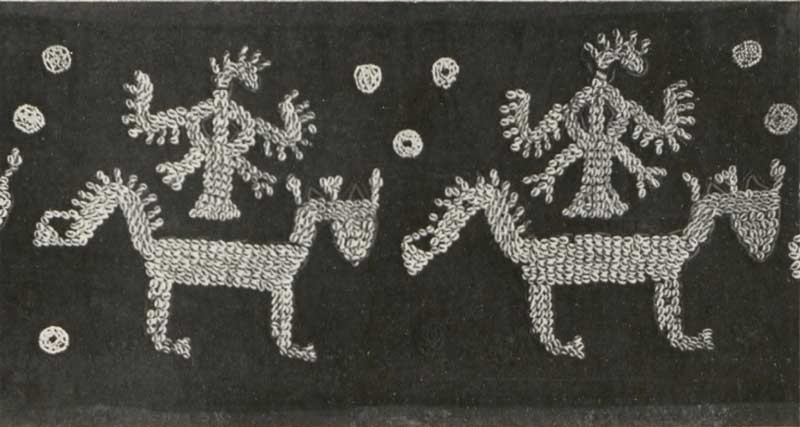

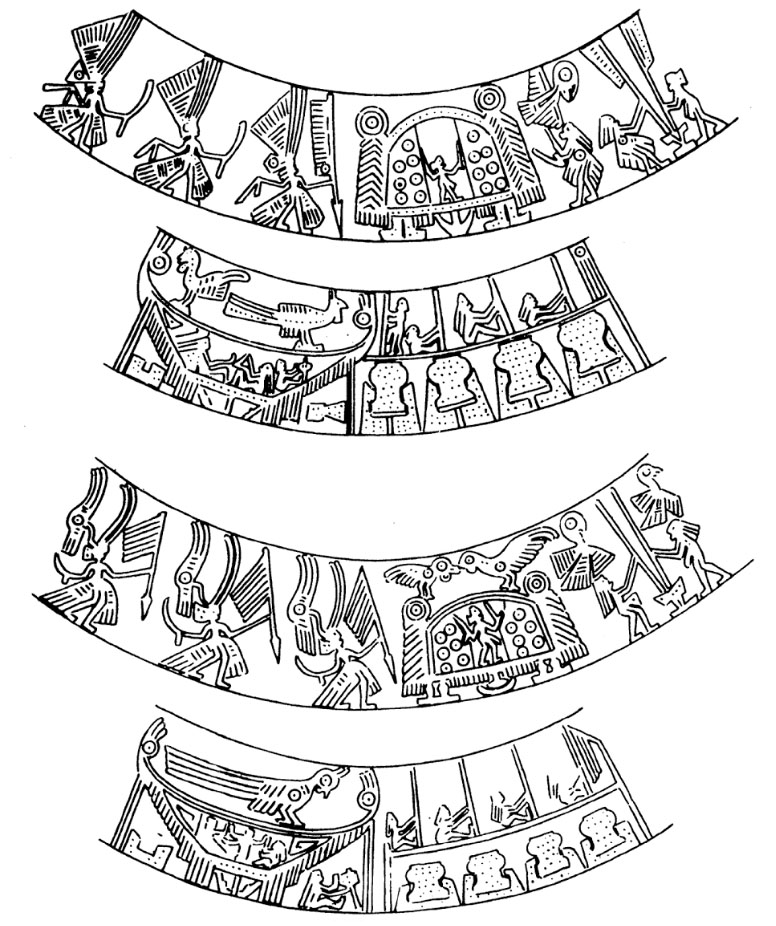

Bintari suggested that type IV moko drums are the most recent and classified them as pre-Second World War. They are relevant to this discussion because of the motifs incorporated in the relief decorations on their sides. Many include a standing or dancing frog with splayed footpads but lesser numbers have a squatting human figure with splayed legs, dangling genitals and raised arms and digits.

Reliefs from the sides of moko drums on Alor

Left: a dancing frog; right: a squatting anthropomorphic figure

It seems that one of these may have been the inspiration for a rock art painting at on a boulder outcrop at Nali behind Lamagute (formerly Atawatung) on the lower slopes of Ilé Api, Lembata Island (O’Connor et al 2018). The figure stands arms and legs akimbo, with splayed fingers and toes and hanging genitals and has been painted using white and yellow pigments.

The rock painting at Nali on Ilé Api, Lembata

(O’Connor et al 2018)

O’Connor and her colleagues suggest that the figure may have been copied from a local moko drum, an heirloom example of which is kept at the old ceremonial village of Lewahala up on the slopes of the volcano above Jontona, about 6km away from Nali on the opposite side of the caldera. As such they believe the rock art has little antiquity and was painted in the last millennium. It seems more likely to us that the painting is more recent – possibly made during the nineteenth century when the majority of moko drums were imported into this region.

The heirloom moko drum kept in a traditional shelter at Lewohala, Ilé Api

The figure appears more frog-like than human

Despite this credible example of an anthropomorphic figure copied from a moko drum we do not believe that the latter was the influence behind the marapu motif found on lau wuti kau. Standing ancestor figures with raised arms and hands appear to be part of a broad tradition mainly confined to the easternmost parts of the Indonesian Archipelago – East Timor, Kisar, Leti, Lakor, Babar and Tanimbar – islands where moko drums have never been found. See Rimanu Motifs. And, of course, moko drums are also absent from Sumba, as already mentioned above.

Why Sumba should be culturally linked to that far eastern region is still hard to fathom unless some of its Austronesian immigrants arrived via south Maluku.

Bibliography on Moko Drums

Ardika, I. Wayan, 1987. Bronze Artifacts and the Rise of Complex Society in Bali, Doctoral Thesis, Australian National University.

Bintari, D. D., 1981. Moko sebagai salah satu unsur penting masa perundagian, Seminar Sejarah Nasional III, 10-14 November, Jakarta.

Bintari, D. D., 1985. Prehistoric Bronze Objects in Indonesia, Indo-Pacific Pre-History Bulletin, vol. 6, pp. 64-73, Jakarta.

Huyser, J. G., 1931. Mokko’s, Nederlandisch-Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 225-236.

Huyser, J. G., 1932. Mokko’s, Nederlandisch-Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 16, no. 11, pp. 337-352.

Nieuwenkamp, W.O.J. 1919a. Iets over een mokko poeng Djawa Noerah, van Alor, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. 36, pp. 220-227.

Nieuwenkamp, W.O.J. 1919b. Mokkos, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. 36, pp. 332-334.

Nieuwenkamp, W.O.J. 1922. Drie weken op Alor, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 67-88.

O’Connor, Sue; Mahirta, Kealy, Shimona; Louys, Julien; Kaharudin, Hendri A. F.; Lebuan, Anthony; and Hawkins, Stewart, 2018. Unusual painted Anthromorph in Lembata Island extends our Understanding of Rock Art Diversity in Indonesia.

Soejono, R. P. 1968. The History of Prehistoric Research in Indonesia to 1950, Asian Perspectives, vol. 12, pp. 69-91.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: Unbekannte Bergvölker im Tropischen Holland, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Bibliography

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1969. System and Meaning in East Sumba Textile Design: A Study in Traditional Indonesian Art, Cultural Report Series 16, Southeast Asia Studies, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1970. Myths and Self-Image Among the Kapunduk People of Sumba, Indonesia, vol. 10, pp. 80–106, Ithaca.

Adams, Marie Jeanne, 1999. Life and death on Sumba, Decorative Arts of Sumba, pp. 11-29, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam.

Anon., 1918. Tentoonstelling, Weefsels en Kralenwerk van Soemba, Nederlandsche Indische Kunstkring te Batavia.

Bertling, C. T., 1931. De Minahasische 'Waroega' en 'Hockerbestattung', Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 33-51.

Cutsem-Vanderstraete, Anne, and Bremer, Stanley, 2012. Magie van de Vrouw: Weefsels en sieraden uit de Gordel van Smaragd, Stichting Wereldmuseum, Rotterdam.

Dammerman, Karel Willem, 1926. Een tocht naar Soemba, Natuurkundig Tijdshrift voor NederlandschIndisch, LXXXVI, reprinted by Indisch Comite uoor Wetenschappelijke Onderzoekingen, Batavia.

Djajasoebrata, Alit, and Hansen, Linda, 1999. Sumbanese textiles, Decorative Arts of Sumba, pp. 52-153, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam.

Doherty, William, 1891. The Butterflies of Sumba and Sambawa, with some account of the Island of Sumba, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol. LX, part II, no. II, pp. 141-197, Calcutta.

D. J. van den Dungen Gronovius, 1855. Beschrijving van het eiland Soemba of Sandelhout, Tijdschrift voor Neerlands Indie, 17 (1), pp. 277–312. Resident of Kupang, 1838

Fischer, Joseph, 1979. Threads of Tradition: Textiles of Indonesia and Sarawak, Lowie Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley.

Forshee, Jill Kathryn, 1996. Powerful Connections: Cloth, Identity and Global Links in East Sumba, Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Forshee, Jill, 1999. Unfolding passages; weaving through the centuries in east Sumba, Decorative Arts of Sumba, pp. 30-51, The Pepin Press, Amsterdam.

Forshee, Jill, 2001. Between the Folds: stories of cloth, lives, and travels from Sumba, University of Hawai‘i Press, Hawai’i.

Forth, Gregory L., 1981. Rindi: an Ethnographic Study of a Traditional Domain in Eastern Sumba, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Hangelbroek, H., 1910. Soemba: land en volk, G. F. Hummelen, Assen.

Hitchcock, Michael, 1991. Indonesian Textiles,

Kartik, Kalpana, 1998. Ritual and Myth in Sumbanese Textiles, Arts of Asia, vol. 28, issue 6, pp. 108-139,

Kate, Herman F. C. ten, 1894. Soemba, Verslag eener reis in de Timorgroep en Polynesië, part III, Tijdschrift Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2nd series, vol. XI, pp. 541-638, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Langewis, Laurens, and Wagner, Frits A., 1964. Decorative Art in Indonesian Textiles, C. P. J. van der Peet Uitgeverij, Amstedam.

Langley, M. C., and O’Connor, S., 2015. 6500-Year-old Nassarius shell appliques in Timor-Leste: technological and use wear analyses, Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 62, pp. 175-192.

Nieuwenkamp, Wijnand Otto Jan, 1920. ‘Soemba Weefsels’, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsche Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, vol. 37, pp. 374-378 and 503-513.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1923. Iets over Soemba en de Soembaweefsels, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 7, issue 10, pp. 295-313.

Nieuwenkamp, W. O. J., 1927. Eenige Voorbeelden van het Ornament op de Weefsels van Soemba, Nederlandsch Indië Oud & Nieuw, vol. 11, issue 9, pp. 259-288.

Nooteboom, C., 1940. Oost-Soemba: Een Volkenkundige Studie, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Quincey, Jennifer A., 2001. Textiles: Function and Symbolism within the Social and Ritual Systems of Sumba, Eastern Indonesia, Baccalaureate Thesis, Northern Illinois University.

Roo van Alderwerelt, J. K. H. de, 1890. Eenige Mededeelingen over Soemba, Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. XXXIII, pp. 565-595.

Roos, Samuel, 1872. Bijdrage tot de kennis an taal-, land- en volk op het eiland Soemba, Verhendelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, vol. 36, pp. 1-125.

Taylor, Paul Michael, and Aragon, Lorraine V., 1991. Beyond the Java Sea: Art of Indonesia’s Outer Islands, Harry N. Abrams, New York.

Warming, Wanda, and Gaworski, Michael, 1991. The World of Indonesian Textiles, Kodansha International, Tokyo, New York, London.

Appendix – The Spurious Link to Dong-son

Dong Son is the most well-known of over one hundred archaeological sites excavated in the Red River delta of the Bac Bo region of Than Hoa Province in far northeastern Vietnam (Bulbeck 2004, 429). Extravagant burials in boat-like coffins containing large amounts of funerary goods point to the existence of a wealthy elite, most probably hereditary chiefs. At least 171 coffins have been excavated, 12 of which have been carbon-dated from the fifth to the first century BCE (Liem 2005, 118). This region was inhabited by a sophisticated society that had developed the technology of bronze metallurgy to an advanced level, producing richly decorated kettledrums, buckets, socketed axes, daggers, bowls, bells, bracelets and belt hooks. Although the Chinese took control of the region in 43 CE, bronze production continued for at least two further centuries.

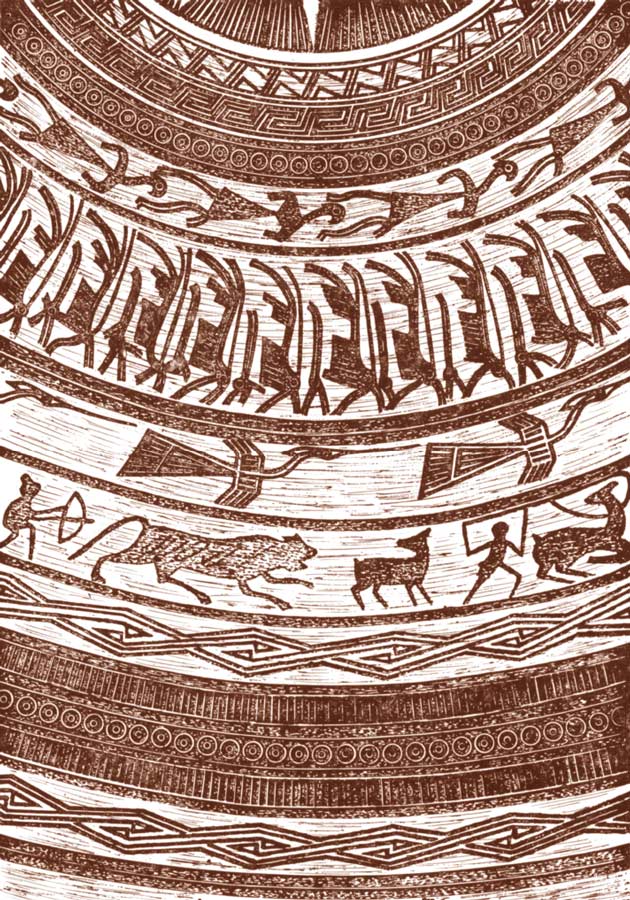

The pinnacle of Dong Son bronze casting was a large kettledrum, subsequently classified by the Austrian scholar Franz Heger as a Heger type-I. It had a flat tympana, bulbous upper sides and a splayed base, was cast in one piece, was up to one metre in height and could weigh up to 100 kilogrammes (Bellwood 1999, 122). It was intensively decorated with concentric circular zones radiating out from a central starburst. The zones were filled with detailed freezes of herons, deer and other animals, warriors wearing feather headdresses, houses with raised floors and a range of intricate repetitive geometric patterns.

Decoration on the tympanum of a kettledrum from the Kei Islands

(Hereeken fig. 13, 1958)

Heger type-I drums were widely traded as very high-status artefacts, possibly acquired as symbols of authority. In total more than 200 Heger type-I drums, or parts thereof, have been found from across Southeast Asia (Bellwood 1999, 122). Six of these have been located in Western Malaysia and fifty-six in the Indonesian Archipelago from Sumatra, Java, Sumbawa, Selayar in south Sulawesi, Rote, Alor, Leti, Luang, to the Kei Islands (Heereken 1958; Bellwood 2007, 278). Others have been found in Timor Leste and at Ayamaru, West Papua. None have been found on Sumba, Borneo or in northeast Indonesia. The drums seem to have been traded from around the first century BCE to the beginning of the second century CE (Imamura 2008, 38). Their distribution follows an ancient maritime trade route running along the more sheltered northern shore of the Malay Archipelago as far as southern Maluku and the Bird's Head Peninsula of New Guinea.

A Heger type-I bronze drum found in 1972 at Kokar on the north coast of the Bird's Head Peninsula on Alor Island (Museum of One Thousand Mokos, Kalabahi)

In 1934 the leading Austrian anthropologist, Robert Freiherr von Heine-Geldern, began to formulate an elaborate theory of long-distance migration, proposing that people from the bronze-age Hallstatt culture in Europe migrated with their metallurgic technology through the Caucasus to East and Southeast Asia, establishing what he termed the ‘Dong-son culture’ of Annam. This migration subsequently continued down the Malay Peninsula and into Indonesia. Dong-son culture penetrated Southeast Asia from the north not later than about 300 BCE, perhaps as early as 600 BCE, and must have lasted until about 100 CE (Heine-Geldern 1935, 315). The double spirals and plaited bands on Batak jewellery had their origin in Dong-son culture, as did the house decorations of the Batak of Sumatra and the Dayak of Borneo (1935, 319-320). The forms of the Toba and Minangkabau house were also related to the houses depicted on the oldest Dong-son bronze drums (1935, 328).

A decade later Heine-Geldern elaborated on the origins of the Indonesian graphic designs:

The decorative designs found on bronzes of the Dongson Culture in Indo-China as well as Indonesia – double spirals, circles linked by tangents, meanderlike patterns, etc. – are of western origin and closely related to, and indeed in many cases identical with, those of the Hallstatt Culture of Europe, the Thraco-Cimmerian Culture of the Lower Danubian regions and South Russia, and the Early Iron Age of Caucasia (Heine-Geldern 1945, 147).

He illustrated his comments with two bronze axes from Rote Island (Fig. 44).

In 1948 the Asia Institute in New York held a highly influential exhibition of 172 Indonesian textiles along with many other art objects loaned from the Indian Museum, Amsterdam. It subsequently moved on to Buffalo, Chicago and Baltimore. In an introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Heine-Geldern extended his ideas to weaving, suggesting that the technology of warp-ikat weaving and the decorative motifs that it employed originated with the Dong-son culture (Heine-Geldern 1949):

Whether or not the Indonesians knew the art of weaving already in the Late Stone Age has not been definitely established. It seems more likely that they used only bark cloth and that weaving was one of the many accomplishments introduced during the Dongson period. In any case, it seems fairly certain that the ikat or tie-dyeing technique, so widely used by the Indonesian peoples, came to the Archipelago with the Dongson culture.

Heine-Geldern’s theory became entrenched in the literature of Indonesia textiles, regularly trotted out to explain the origin of local textile designs (Langewis and Wagner 1964, 13; Kahlenberg 1977, 7; Fischer 1979, 9, 73; Warming and Gaworski 1981, 43, 79-80; Fraser-Lu 1988, 4; Holmgren and Spertus 1989, 106; Hitchcock 1991, 15, 160-161; Gillow 1992, 10, 73-74; etc. etc.).

Jill Forshee went further, claiming that ‘many researchers have considered’ that the front-facing human figures appearing on Sumbanese fabrics descended from ‘the Dongson cultural migrations from Southern Vietnam one to two thousand years ago’ [sic] (1996, 67). In fact four of the five references she listed considered no such thing.

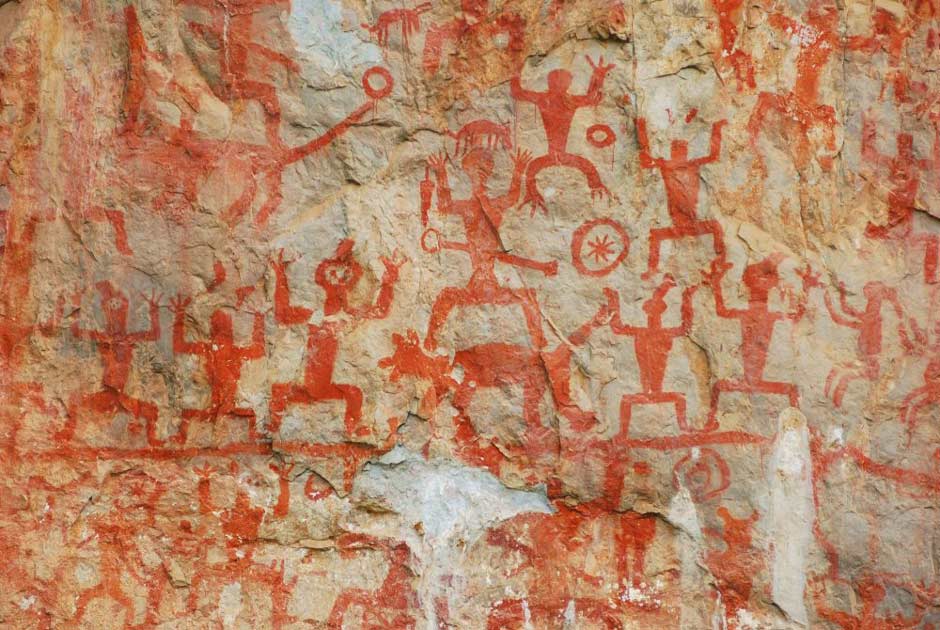

Certainly similar standing anthropomorphic figures did exist in the neighbourhood of the Dong Son region at a time when its bronze smiths were producing the Heger type-I kettledrums. Some 1,400 of them appear in the rock paintings of 38 sites at Huashan in the Zuo River valley of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China, close to the border with Vietnam. Painted by the ancient Luo Yue who undoubtedly had links to the neighbouring Dong-son Lạc, they have been carbon dated to the period 400 BCE to 400 CE (Gao 2013; Kim 2015, 248). Most of the anthropomorphic figures, whether shown frontally or in profile, have a uniform appearance and are adopting the same posture with raised arms and hands and legs and feet akimbo. However the figure in the centre of each group has a headdress and sword.

Figures painted with hematite and animal blood at Huashin cliff

Such images could have only been transported to the Lesser Sunda Islands on Dong-son bronze trade goods. The problem is that the large Heger type-I kettledrums that have so far been identified in this region are decorated with far more sophisticated anthropomorphic figures than those that appear in the Huashan rock paintings or the Sumbanese lau wuti kau. They include stylised warriors wearing dramatic feather headdresses and stylised figures planting and processing rice.

Longboat and crew depicted on a Heger type-I bronze kettledrum

Friezes on Dong-son drums showing cereal-husking and rice-planting. Rice would have provided the surplus to support the development of an advanced bronze industry (Hill 2012, 7, 13)

As a postscript, a recent phylogenetic analysis of warp-ikat motifs included a comparison of the geometric figures found on mainland and island Southeast Asia textiles with those found on Dong-son drums. It found little or no overlap (Buckley 2012). In particular, the hook and rhomb motifs characteristic of Southeast Asian weaving that are often claimed to be Dong-son were not identified on Dong-son bronzes.

Heine-Geldern was wrong on two counts. Dong-son designs did not originate in Europe; neither did they influence the material textile culture of Indonesia.

Bibliography to Appendix

Bellwood, Peter, 1999. Southeast Asia before History, The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, vol. 1, part 1, pp. 55-136, Cambridge University Press.

Bellwood, Peter, 2007. Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago: Revised Edition, ANU E Press.

Blench, Roger, 2012. Almost Everything You Believed about the Austronesians Isn’t True, Crossing Borders, NUS Press, Singapore.

Buckley, Christopher D,. 2012. Investigating Cultural Evolution Using Phylogenetic Analysis: The Origins and Descent of the Southeast Asian Tradition of Warp Ikat Weaving, PloS ONE, 7(12): e0052064.

Bulbeck, David, 2004. Dong Son, Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, vol. 1, pp. 428-431, ABC-CLIO.

Bulbeck, David, 2017. Traditions of Jars as Mortuary Containers in the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago, New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory, pp. 141-164, ANU Press.

Calò, Àmbra, 2009. The distribution of bronze drums in early Southeast Asia: trade routes and cultural spheres, Archaeopress,

Forshee, Jill Kathryn, 1996. Powerful Connections: Cloth, Identity and Global Links in East Sumba, Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Heekeren, H. R. van, 1958. The Bronze-Iron Age in Indonesia, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague.

Heger, Franz, 1902. Alte Metalltrommeln aus Siidostasien, Leipzig. [Impossible to locate].

Heine-Geldern, Robert 1934. Vorgeschichtliche Grundlagen der Kolonialindischen Kunst, Wiener Beitrage zur Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte Asiens, Band VII, p. 5-40.

Heine-Geldern, Robert, 1935. The Archaeology and Art of Sumatra, Wiener Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Lind Linguistik des Institutes für Volkerkunde der Universitat Wein, vol. 3, pp. 305-328, Verlag des Institutes vor Volkerkunde der Universitat Wein.

Heine-Geldern, Robert von, 1945. Prehistoric Research in the Netherlands Indies: Science and scientists in the Netherlands Indies, Natuurwetenschappelijk Tijdschrift Voor Nederlandsch Indië, vol. 102, Special Supplement, pp. 129-167, Board for the Netherlands Indies, Surinam and Curacao.

Heine-Geldern, Robert von, and Bertling, C. T., 1948. Indonesian Art: A Loan Exhibition from the Royal Indies Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 31, to December 31, 1948, The Asia Institute, New York.

Imamura, Keiji, 2008. The Distribution of Bronze Drums of the Heger I and Pre-I Types: temporal Changes and Historic Background, Unpublished Conference Paper, Meetings of Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Manila, Philippines.

Liem, Bui Van, 2005. A Study of Boat-Shaped Coffins from the Dongson Sites in Vietnam, Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin, vol. 25, pp. 117-119.

Publication

This webpage was published on 19th February 2018.