Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Buaya Island

A Short History

Ethnography

Weaving on Buaya

The Textiles of Buaya

Kafate Bélang

Tenapi Matang Kari

Kafate Sontoraja

Tenapi Muko Tahakang

Kafate Bul Ihing Launjia

Kafate Leor Manis

Kafate Sinta Galla

Kafate Mobehe

Tenapi Tenamang

Nofang

Bibliography

Introduction

We first visited beautiful Buaya Island in April 2004, not only collecting our very first textiles woven on the island but snorkelling from one of its pristine beaches, Obi Singga. Since then we have sailed past it many times on our voyages from Lembata to Kalabahi on Alor and back from Kalabahi to Lembata or Pantar, but only returned to spend time with its weavers in 2018.

The inhabitants of Buaya Island are Muslims who only moved there from the neighbouring island of Ternate in 1935, following a schism in religious beliefs. Consequently there are close similarities between the traditional textiles that were produced on both islands, although the appearance of their modern textiles has diverged considerably. In general there are common features between all of the traditional textiles produced by the coastal Alorese-speaking peoples in the Pantar Strait - Buaya, Ternate, Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong. However local terminologies often differ. As in many other parts of eastern Indonesia, if you do not know which village a textile was woven in, you cannot accurately give it a name.

Today commercial weaving is thriving on Buaya Island, with almost half of all adult women producing simple, inexpensive chemically dyed sarongs and sashes. These are mostly sold on the Alor mainland, providing an important ancillary source of income for a tiny island with few resources of its own.

Return to Top

Buaya Island

Buaya Island is the northernmost of a string of four islands lying in the centre of the Pantar Strait, which separates the islands of Pantar and Alor in eastern Indonesia. The others are Ternate, Pura and Tereweng. It is just 4km from the Kabola Peninsula of Alor and 5km from Muna Seli on northern Pantar.

Today Buaya and the other islands between Pantar and Alor fall within the Alor District Marine Conservation Area, formed in 2009 by increasing the area of the former Pantar Strait National Park (Fitriana 2014, 306). The Alor government initially established a Taman Laut (Sea Garden) in 2002, which was elevated to a Marine Conservation Area in 2006. The Pantar Strait is rich in sea life including tuna, manta rays, turtles, dugong, sunfish and whale sharks and is also an important seasonal migration route for various species of whale. In addition it has some outstanding dive sites, making it a prime diving destination. Unfortunately the Conservation Area is poorly protected with little sign of any enforcement of regulations.

The location of Buaya Island between Pantar and Alor, labelled here as Kisu Island

(Image courtesy of the US Army, Washington D. C. 1963)

Tiny Buaya is just 2.11 kilometres square, being only 1.8km wide and 1.7km from north to south. It is a low-lying island with just one hill, less than 200m in height. It is mainly covered with dry, sparsely vegetated savannah. The northern half of the island is fringed by coral reefs and there are three long white sandy beaches. The wet season lasts from October/November to March/April, during which the island and the entire Pantar Strait are affected by strong winds from the west. In addition cold currents sweep through the strait about twice a year, usually during the dry season, bringing shoals of fish and dolphins close to the shore.

Above: Barren Buaya with its single settlement and one tree-topped hill.

Below: The topography of Buaya

(Images courtesy of Google Earth and Google Maps)

The word buaya means crocodile in Bahasa Indonesia, a term that is frequently applied to the island because of its crocodile-like shape when viewed from the sea. However some have suggested that the name of the island was inspired by a whale not a crocodile, this being an important seasonal migration corridor for whales (Wellfelt 2019). According to an Indonesian linguist who has recently documented Bahasa Buaya, the islanders call a crocodile a bapa and a whale a bapa klaru (Sulistyono 2019).

In the past Buaya has been given a variety of names. Some local people referred to Buaya as Nuha Kae or Small Island in contrast to its larger neighbour Ternate, which was called Nuha Béing or Big Island (Wellfelt 2007, 20, note 25). Perhaps that is why in a few texts Buaya is referred to as Little Ternate.

When the Resident of Timor, D. W, J. C. Baron van Lynden, visited Alor in 1851 he referred to Buaya as Pulau Padjang (1851, 329). This designation ‘Long Island’ is presumably derived from the island’s appearance from the sea – see the image below. It was still recorded as North or Panjang Island by Findlay (1878, xxxiii) and as Pandjang by Johan Jacobsen when he visited Alor in 1888 (1896, 83). The Kapitan of Alor Kecil dismissed this term in 1908, stating that the northernmost of the four islands was not Pandjang but Kisoh (Departement van Overzeese Rijksdelen 1908, 373). When Ernst Vatter visited Alor in early 1928 he once again called the island Pandjang (1932, 16). The US Hydrographic Office applied the same name in 1935. Perhaps Pandjang was an appellation used by foreigners and not by the local people.

On some charts Buaya is mistakenly labelled Reta.

Buaya Island viewed from the south

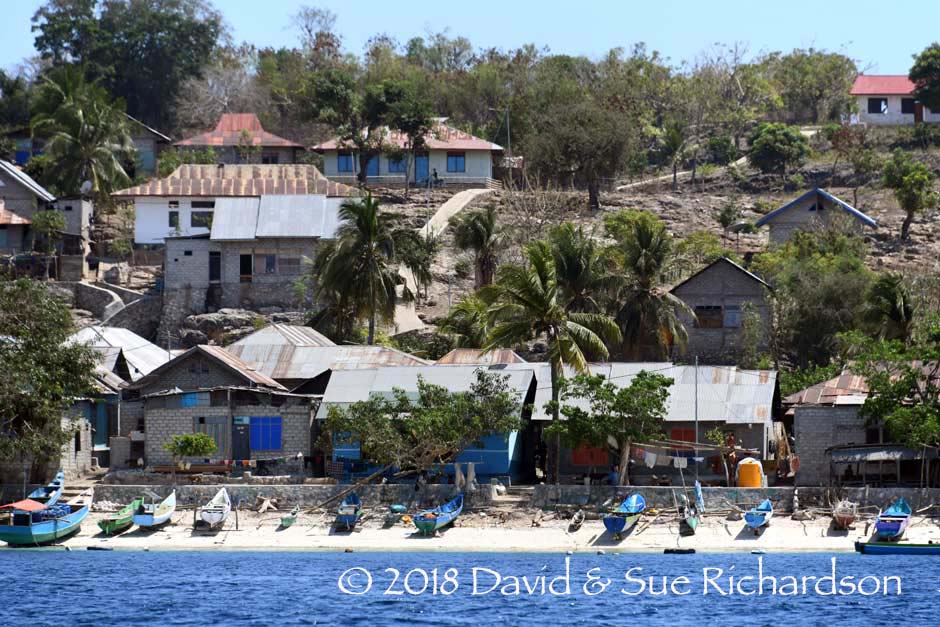

Buaya has just one village, Nuhakisu, located on the south side of the island by one of its beaches. The south coast of Buaya was chosen because it is calmer, sheltered by Ternate Island, and is not impeded by a coral reef. Because of the name of the village, Buaya is labelled as Kisu Island on the US Army map shown above. The kepala desa of Nuhakisu is currently Bapak Hamsa Wahid.

Aerial view of Nuhakisu (Image courtesy of Ditjen EBTKE)

Above: The waterfront and beach at Nuhakisu. Below: Looking south towards Ternate

In 2017 the population of Buaya Island was 1,251, with 595 males and 656 females spread across 253 households (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor 2018). Of the 253 households, 181 were permanent residents and 70 were not permanent (sic). This illustrates the significant number of residents who work on the Alor mainland or elsewhere.

The island's inhabitants are entirely Muslim and speak a dialect of Bahasa Alor. This is also called Alorese or Coastal Alorese, and the same language is spoken in the village of Uma Pura on neighbouring Ternate, in Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong on the mainland at the mouth of Kalabahi Bay, and in pockets on the east and north coast of Pantar (Klamer 2017, 6). Their village has one mosque called Masjid Al Ijtihad Ternate.

The Masjid Al Ijtihad Ternate, built close to the beach in Nuhakisu in 1972

Buaya has no roads and no cars or motorcycles. There are only footpaths and numerous small boats, 15 of which are motorised. It takes 15 minutes on a small ferry to get to the important port of Alor Kecil, which has bemos and buses to Kalabahi.

The village has one kindergarten, three primary schools (SD) and one junior high school – a madrasa tsanawiyah (MT). To continue their education to senior secondary level at a madrasa aliyah, children must cross to Alor Island or be sent to an Islamic boarding school on Java. Local medical support is provided by 3 midwives, one nurse and 3 trained shaman.

In terms of occupation, government statistics for 2016 list 376 farmers, 251 fishermen, 35 livestock-breeders and 12 traders. 322 people were classified as industrial or craft workers, a category encompassing carpenters, boat-builders, weavers and basket-makers.

Most of the men earn a living from the sea, catching fish or harvesting sea cucumbers. Some fish locally with fish traps called bubu or nets using small outriggers, while others travel considerable distances in larger Makassarese-type vessels for their catches, staying away from home for several months (Gomang 1993, 40).

A small outrigger in the crystal clear waters of Buaya

Weaving a bubu fish trap with split bamboo by the beach at Nuhakisu

The women are mainly responsible for farming and raising livestock as well as weaving. They grow cassava, maize, green beans and red beans, and tend herds of goats, which roam free during the dry season but are tethered or placed in enclosures during the rainy season. Many homes keep chickens. Most agricultural work is conducted during the rainy season, women spending much of the dry season weaving sarongs, which are bartered or sold on Alor or Pantar.

In the past the island has had no natural water supply. Water had to be imported from either the Alor or Pantar mainland. A water distillation plant was built at the west end of the village fourteen years ago but fell into disuse because of lack of maintenance. The village was forced to obtain its fresh water from Kepa Island opposite Alor Kecil or from a spring on the beach at Baolang on the Alor mainland opposite. However in 2003 and 2011 there were clashes between the islanders trying to get water and local residents on Alor. There was even one incident of an islander drowning when his boat sank after collecting fresh water. In 2018 the Resident of Alor announced a plan to resolve the island’s water problem by drilling 12 clean-water boreholes.

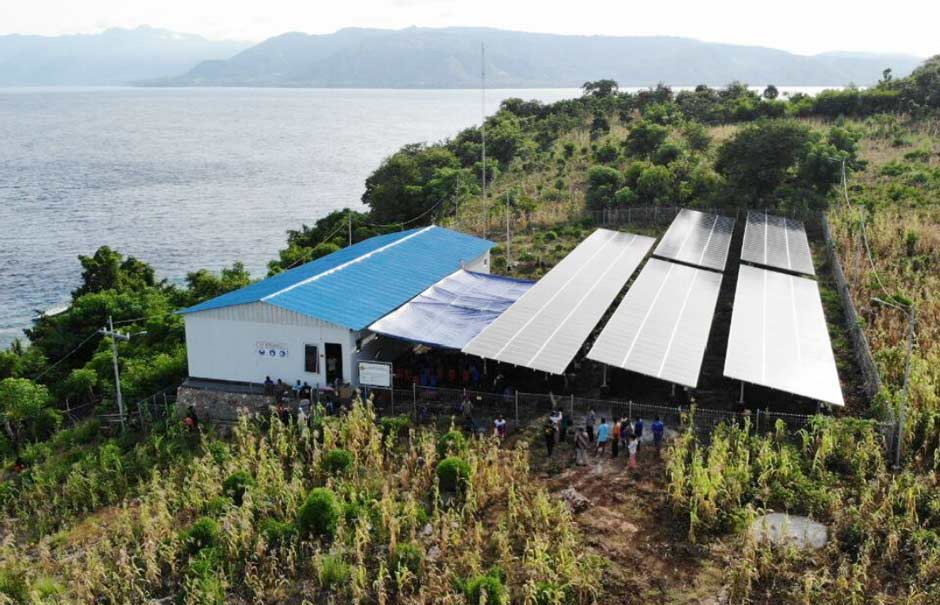

The new solar power station at the west end of the village

(Image courtesy of Ditjen EBTKE)

Until recently Buaya had no public electricity supply. As a result of an IDR 8.5 billion government project, a 100Kw solar power station was built at the foot of the hill at the west end of the island. Opened in October 2017, it now provides power for the majority of families from dusk until midnight. Thanks to the Telkomsel tower at Alor Kecil, the islanders have had good cellphone communications for some years.

In 2016 there were 15 satellite dishes on the island and 42 televisions (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor 2018).

Neverthless poverty on Buaya remains significant. In 2017 the humanitarian charity Aksi Cepat Tanggap distributed food aid to poor families on the island. They returned in January 2018 to organise the mass circumcision of 100 children in the Al Ijtihad Mosque (ACT News 28.01.2018). The children's families had previously been unable to afford the cost of a circumcision ceremony.

Return to Top

A Short History

When the Resident of Timor, Dirk Wouter Jacob Carel Baron van Lynden, visited Alor in 1851 he referred to the northernmost island in the Pantar Strait beyond ‘Poera’ and Ternate as Pulau Padjang, (1851, 329). He described it as being low, with a small hill in the middle. Van Lynden died the following year aged just 33. Although later visitors mentioned the island, they do not appear to have visited it - perhaps not surprising since until the 1930s Buaya Island was uninhabited and was simply used as grazing land for goats.

Following the imposition of direct Dutch rule in the early 1900s, a number of groups emerged in locations such as Sumatra, Java and Ambon to promote their own local ethnic interests (Ricklefs 1993, 168). It was not until 1921 that Haji Dasing, an Alorese noble from Dulolong, joined with other intellectuals to form the Timorsch Verbond (Timorese Alliance) aimed at defending the interests of the people of the Timor region (Gomang 1993, 113). Having previously been spooked by protests and uprisings elsewhere, the colonial government quickly banned it the following year. Haji Dasing went on to found a local branch of Partai Komunis Indonesia, only to see the entire PKI outlawed by the government in 1927 following failed uprisings in Batavia and other regional cities.

Undaunted by these setbacks, Haji Dasing's supporters sent him to Makassar in 1930 to meet the leaders of the local branch of Partai Syarikat Islam Indonesia, an organisation founded in 1905 by Muslim merchants in Surabaya as a counter to the growing power of local Chinese businessmen. With the assistance of Makassar he established an Alor branch of SI-Indonesia with an initial membership of just thirty. Just like many similar regional branches, it developed rapidly as a vehicle for promoting independence from Holland.

The connection with Makassar soon led to the introduction of a modern, reformist interpretation of Islam to the Alor branch of SI-Indonesia. Called Muhammadyah ('followers of Muhammad'), it had been founded in 1912 by a member of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. It emphasised ijtihad (independent reasoning), the individual interpretation of the Qur'an and the sunnah, the body of Islamic customary law and practise. It contrasted with taqlid (imitation), the acceptance of traditional interpretations of Islam propounded by the ulama, the established Muslim clergy. It focussed on the authority of the Qur’an and the abolition of all superstitious customs, while encouraging religious tolerance, schooling and education.

The new ijtihad form of Islam became popular in Dulolong, but was not adopted in Alor Besar or Alor Kecil (Gomang 1993, 114). When a faction of residents in the village of Uma Pura on Ternate Island embraced this new modernist approach it created a schism with traditional believers who followed the more conventional form of Islam, where Islamic beliefs were combined with pre-Islamic practises. In 1935 the reformists left Uma Pura and moved to the uninhabited island of Buaya to build a new settlement. There they constructed their own mosque which they named Al Ijtihad.

Within the colonial structure of the Landschap of Alor, Buaya and neighbouring Ternate were at this time under the authority of the Atabeng or Raja of Alor Besar, Mahmud, the grandson of Kwiha Tuli II, the former Raja of Alor who had been deposed by the Dutch in 1912.

Following independence this administrative structure remained in place until 1965 when it was replaced by six new districts or kecamatan, each headed by an elected sekretariat daerah. One of these was Alor Barat Laut (Northwest Alor), which encompassed most of the Kabola Peninsula. This was divided into a number of desa or extended villages, one of which was Alor Besar. The latter continued to govern the offshore islands of Ternate and Buaya.

Over the years the residents of Ternate and Buaya became increasingly dissatisfied with their position, ruled from the village of the former Raja. They felt left out on the periphery of the region's administration and economy, treated as underdogs and starved of development resources. In the early 1990s the menfolk of the two islands revolted, some 80 men from both Ternate and Buaya sailing to Alor Besar and demanding their separation from the mainland village (Wellfelt 2007, 10). Although some were arrested and imprisoned, their protest did make an impact. In 1994 Ternate and Buaya became desa persiapan (preparatory desa) and in 1996 full desas. Today Buaya is divided into two hamlets or dusuns.

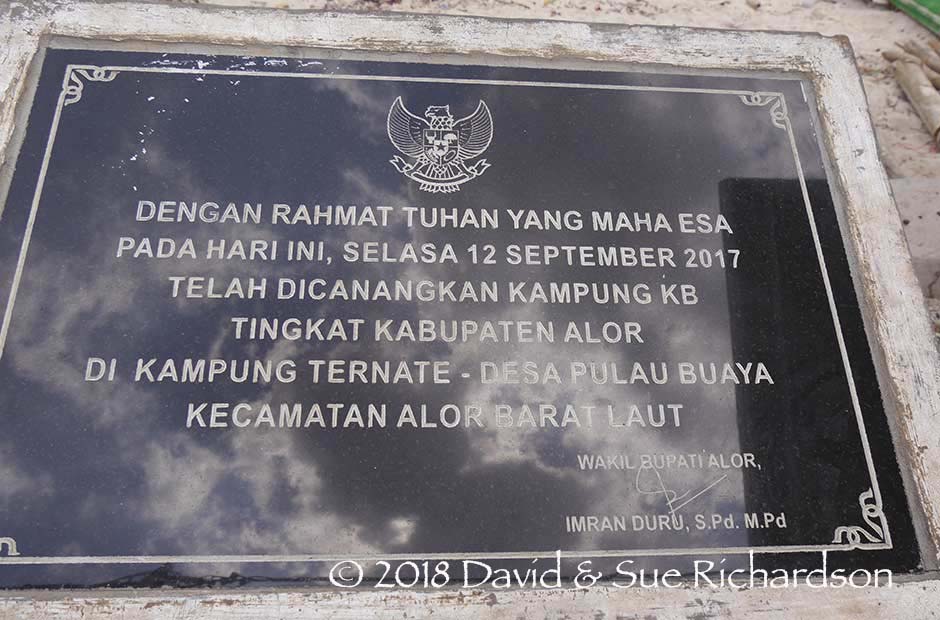

In 2017 Pulau Buaya committed to join the Indonesian Keluarga Berencana (KB) or family planning programme, in which families strive to limit their families to no more than two children.

The commemoration plaque recording the date Buaya committed to join Keluarga Berencana

Return to Top

Ethnography

The villagers of Buaya belong to the wider Alorese ethnic group, along with the villages of Uma Pura on Ternate, and Alor Besar, Alor Kecil and Dulolong on the opposite mainland coast of Alor. Their origin seems to go back to a group of Lamaholot speakers who migrated from Lembata to north Pantar in around the fourteenth century, some of whom later spread to coastal parts of Alor (Klamer 2010, 8). For more details click here.

Because of its recent history, Buaya has a close but sometimes conflicting relationship with Uma Pura. They share the same language, similar Islamic and adat beliefs, parallel clan structures, and considerable intermarriages – the most common marriage alliances are between members of the two moieties living on each island (Wellfelt 2007, 20). However there is also intense rivalry between the two villages. Emily Wellfelt witnessed a football tournament in 2003, which included a match between Nuhakisu and Uma Pura that descended into violence (2007, 31). After the tournament, villagers on the Alor mainland temporarily stopped the men from Buaya going ashore to collect water.

As mentioned above, Buaya Island has the same clan structure as Uma Pura on Ternate. This structure goes back to Wata Kamang, the founding ancestor of Uma Pura, who originated from Pura Island and was temporarily exiled at Alor Besar before being banished to Sebanjar just south of Alor Besar by the Atabiang. From there Wata Kamang decided to take his family to adjacent Nuha Béing (Big Island), later known as Ternate.

There are eight patrilineal descent groups or suku, arranged into two exogamous moieties. Over the last 80 or so years the terminology used on Buaya for a few of the suku has diverged from that used on Ternate. To add complications, there is also a variation in terminology from informant to informant coupled with differences in pronunciation, with some informants using the consonant ‘w’ instead of ‘f’ and vice versa.

| First Moiety | Second Moiety |

| Uma Kakang | Fil Falu Kana Béing |

| Uma Tukang | Fil Falu Folang |

| Uma Aring | Barfahing or Defahing |

| Léing Papa | |

| Deng Wahi or Sebanjar Jawa |

The first exogamous moiety consists of five clans, three of which were founded by the three sons of Wata Kamang: Uma Kakang (the house of the oldest brother); Uma Tukang (the house of the middle brother); and Uma Aring (the house of the youngest brother). A fourth clan called Léing Papa was formed by a family who had been enslaved by Uma Kakang as a punishment for breaking one of their knives at Alor Besar. A fifth clan, called either Deng Wahi or Sebanjar Jawa on Buaya and Deng Wahi in Uma Pura, was founded by two brothers from Sebanjar who had accidentally set fire to a field owned by the Raja of Alor Besar and as punishment had been fined 30 bronze moko drums. Unable to pay the fine they were invited to come to Nuha Béing and take on the role of guards.

The second exogamous moiety consists of three clans and was formed by the descendants of the three sisters of the three founding brothers. Each sister married a man from off the island. Lipanggali, the first daughter, married Liku Amang and their descendants became members of the clan Filu Walu Lolong (Big or Upper Filu Walu), known as Fil Falu Kana Béing on Buaya. Buiresang, the second daughter, married Liang Amang and their offspring formed the clan known as Barfahing on Buaya and Biatabang on Ternate. Finally Saleh, the third daughter, married Jon Béing and gave rise to the clan Filu Walu Lang (Younger or Lower Filu Walu), known as Fil Falu Folang on Buaya.

Uma Kakang is the oldest clan on the island and therefore the most senior, playing a significant role in all matters of adat, in organising lego-lego dances and welcoming important guests.

Each suku has a clan house, or uma suku, inhabited by one extended family. This is the focal point of ritual and ceremonial occasions, and is used to house ancestral objects and clan treasures.

In the past an individual from one moiety had to marry a partner from the other moiety (or someone not from Buaya). Although these rules are no longer enforced, most marriage alliances still tend to be formed between the two moieties. Unlike marriage in Lamaholot society, a bride must abandon her natal suku on Buaya and join her new husband’s suku.

Today there is no exchange of bridewealth, although there may have been in the past. The women in the wife-giver’s suku will give the bride a sarong, which must be of good quality. These are not part of any marriage exchange and become the personal property of the bride. The wife-giver’s suku will also donate gifts to the wife-taker’s suku.

Return to Top

Weaving on Buaya

According to government statistics the number of people producing tenun ikat on Buaya Island in 2017 was 160 working in 85 households (the same as published the previous year), indicating an average of two weavers per household (Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor 2018).

This means that one third of all households on Buaya are involved in weaving. Assuming that these statistics are accurate, that the 160 weavers are entirely female and that the proportion of 15- to 65-year-olds in the population on Buaya is the same as for NTT as a whole (57%), this would suggest 43% of all females in this age group are active weavers. This is the reason that, during the dry season, the lanes and open spaces of Nuhakisu are alive with women and girls winding yarns, warping up and weaving.

The vast majority of modern weaving is done using commercial yarns, mostly pre-dyed but sometimes coloured locally with commercial dyes. Bright colours predominate. Yarns and dyes are purchased at the various markets in Kalabahi.

Today most weavers are producing cloth for sale, an activity known as tané kafate (literally weaving sarongs). Commercial pressures mean that there is little time to carefully bind the ikat motifs or to create the wide ikat bands of the past. Many weavers can produce an average of one sarong a week. The women take their finished cloths across to the mainland to the Friday morning market at Baolang, which starts at 4am and finishes at 7am. They sell simple scarves for around Rp. 100,000 and modern sarongs from Rp. 200,000 to up to Rp. 1,000,000.

Balling skeins of pre-dyed cotton on a crude swift

In the past ikatting was done by binding the bundles of yarn with split palm leaf, but today most weavers use plastic.

Bundles of indigo-dyed yarns bound with plastic string

Above and below: Warping up while simultaneously creating the cross and the heddle

Weaving is done using a frame-braced body-tension loom fitted with a split breast beam. The unusual feature is that weavers use a long shuttle, up to one metre in length, consisting of a simple round wooden rod wound with a considerable amount of weft. This allows them to weave a wider cloth and to continue for a considerable length of time without changing shuttles.

Most modern cloths are only decorated with warp stripes or with narrow bands of complementary warp, a technique copied from the Masin weavers of nearby Kui at Moru just south of Kalabahi Bay. When bands of warp ikat are included they tend to be narrow.

A young woman taking a break from weaving her brightly striped sarong

Weaving complementary warp stripes using pattern sticks

A lane of looms. The weaver in front is making a sarong with narrow bands of simple ikat

Weaving a sarong with chemical stripes and naturally dyed bands of ikat

Weaving in front of the Al Ijtihad Mosque. Note the long shuttles.

Women working in the shade overlooking Ternate Island

Tree cotton, kapo, once thrived in the hot, dry summer climate of Buaya. Although a few women are still hand-spinning their own cotton (kapas) and using natural dyes, many more were doing so in the past. There seems to be no tradition of mixing cotton fibres with milkweed (kolon susu) floss on Buaya as they do on Ternate and once did at Alor Kecil (Wellfelt 2014, 7).

Indigo, known as tang, thrives on Buaya, while morinda, known as bota, grows on the slopes of the main hill. However given the quantity of morinda-dyed yarns used in the textiles of Buaya in past decades, it is hard to believe that this small island can have been self sufficient in morinda root in the past and we suspect that some had to be imported. Here they dye with morinda root without the use of lime (apu) or ash water.

A bag of dry crushed morinda root kept in a house in Nuhakisu

Return to Top

The Textiles of Buaya

This section is an interim report on our studies so far, and is not yet presented as a comprehensive description of Buaya textiles. More research will be required to finalise this work in progress.

The majority of weavers on Buaya are producing two-panel sarongs, known here generically as kafate (pronounced 'kafa'tae'or ‘kava'tae’). Johan Adrian Jacobsen recorded the very similar term kawate for a sarong when he visited Alor Kecil in February 1888 (1895, 99). Today the women of Alor Kecil also use the term kafate. Speakers of Alorese in the Pantar Strait (Buaya, Ternate, Alor Besar, Alor Kecil, Dulolong) sometimes interchange the consonants [f] and [w], as in some dialects of Lamaholot.

As a general rule, however, speakers of Buaya Alorese on Buaya Island use [f] as opposed to [w] (Sulistyono 2019).

In the past each suku had its own exclusive and protected design of kafate, which could only be woven and worn by members of that suku. Today these prohibitions no longer apply, and any suku can weave and wear any pattern without redress.

Although all sarongs are classified as kafate, some are titled tenapi or tanapi. However it is very difficult for weavers to explain what distinguishes a tenapi from a non-tenapi. Some say the term can only be used for a sarong with a specific name. Others say a tenapi has clusters of three narrow bands of warp ikat. We remain confused and have yet to truly understand the difference.

The term tenépa is used widely by Lamaholot weavers to describe an exclusive three-panel ikat sarong, generally associated with wealthy families. The name means ‘extension’ in Bahasa Lamaholot (Barnes 1996, 209). It is used here because the normal two-panel sarong has been extended with an extra central panel. Weavers in the Pantar Strait have clearly inherited this term from their Lamaholot ancestors, from whom they separated in around the fourteenth century, but now use it in a different manner, applying it to two-panel sarongs.

As in Alor Kecil and Ternate, kafate and tenapi are classified according to the arrangements of the narrow warp stripes and bands in the middle section of the sarong, not by the pattern in the outer main ikat band, the mofa inang. This means that different kafate with the same name can appear widely different. The terms used on Buaya are similar to, but not exactly the same as, those used in Alor Kecil, Alor Besar, Dulolong and Ternate Island.

Although some motifs in the main ikat bands have names, weavers often say that they cannot name them all – they were inherited from their ancestors. Many ikat bands containing geometric motifs such as diamonds, rectangles, crosses, stars etc. are termed Baololong, after the founding ancestor of Alor Besar. In the Baololong pisah layout the individual motifs are set against a plain background, while in the Baololong sambung layout there are no plain unikatted areas between the continuous motifs.

While modern sarongs made for the local market are woven from commercial yarn, most traditional kafate are made from naturally dyed hand-spun yarn, apart from some of the coloured warp stripes which are woven with pre-dyed commercial yarn.

There were, and are, an enormous number of different patterns produced on Buaya, probably too many to ever be covered comprehensively, especially if one includes the modern designs. Some of the main types found on the island are given below:

Return to Top

Kafate Bélang

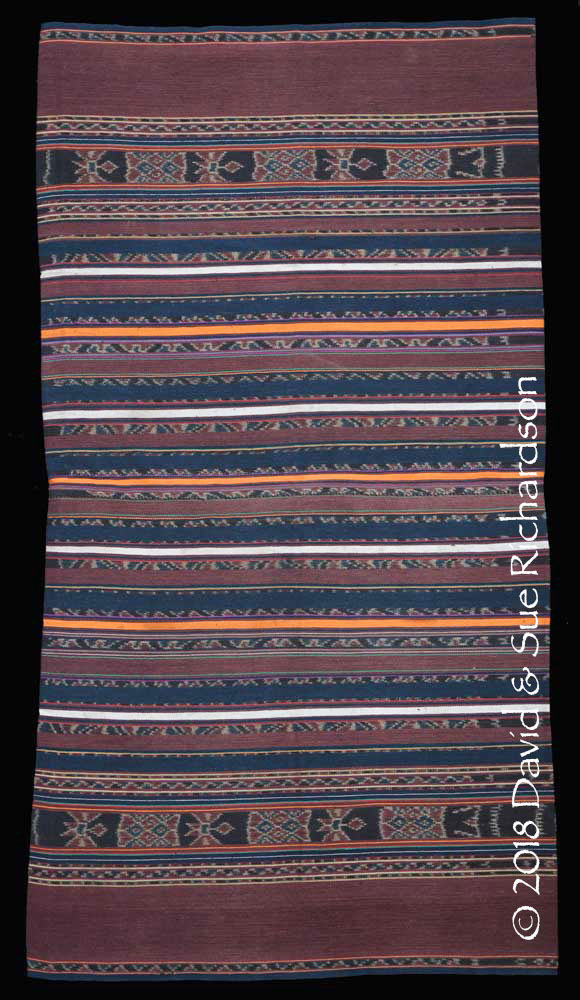

The kafate bélang is distinguished by a middle section in which the naturally dyed bands of ikat and plain weave are intersected by bold alternating wide stripes coloured either white or orange, along with eight less obvious bands of plain indigo. There are usually four white and three orange stripes, therefore one panel has to be slightly longer than the other to incorporate the central orange stripe. The white and orange coloured warp stripes are woven from pre-dyed two-ply commercial yarns. Narrower stripes using other colours of commercial yarn are also included.

Buaya weavers say that bélang means great although in Buaya Alorese big translates as béing (Sulistyono 2018). However bele or belang mean big in Bahasa Blagar, spoken on the Pantar coast adjacent to Buaya (Gomang 2006, 480). In Bahasa Indonesia belang means bright, striped or mottled and in Dutch it means importance or significance.

The kafate bélang pattern was previously restricted to suku Uma Tukang, the clan with the second highest status after the oldest clan, suku Kakang. It is intended for ceremonial use, such as adat ceremonies, for welcoming guests and the lego lego dance.

The first example of a kafate bélang shown below was woven with hand-spun yarn by Siti Ibrahim from suku Uma Tukang. She died in 2009 aged over 75-years-old, so was therefore born before 1934. Local weavers said they could not name the motifs in the Baololong pisah, simply stating that they were inherited from their ancestors.

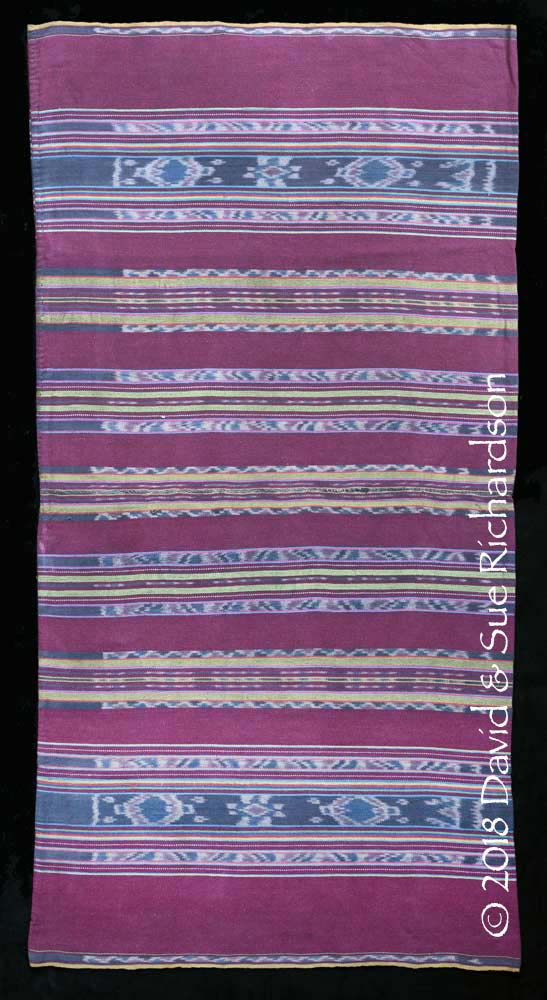

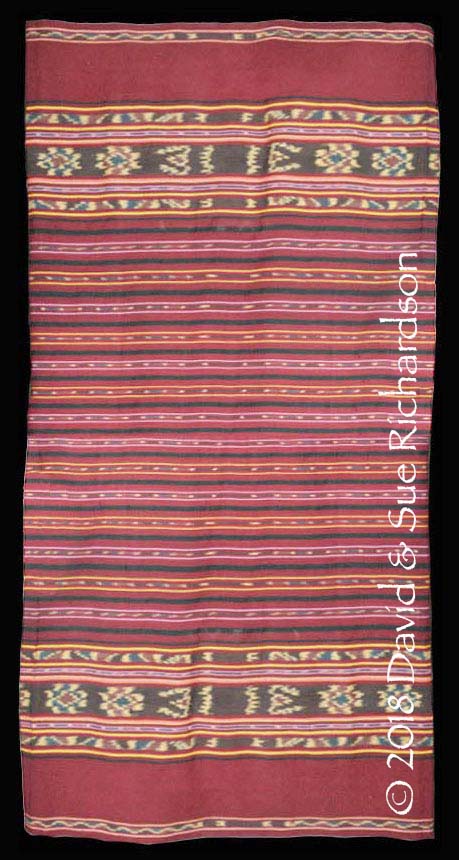

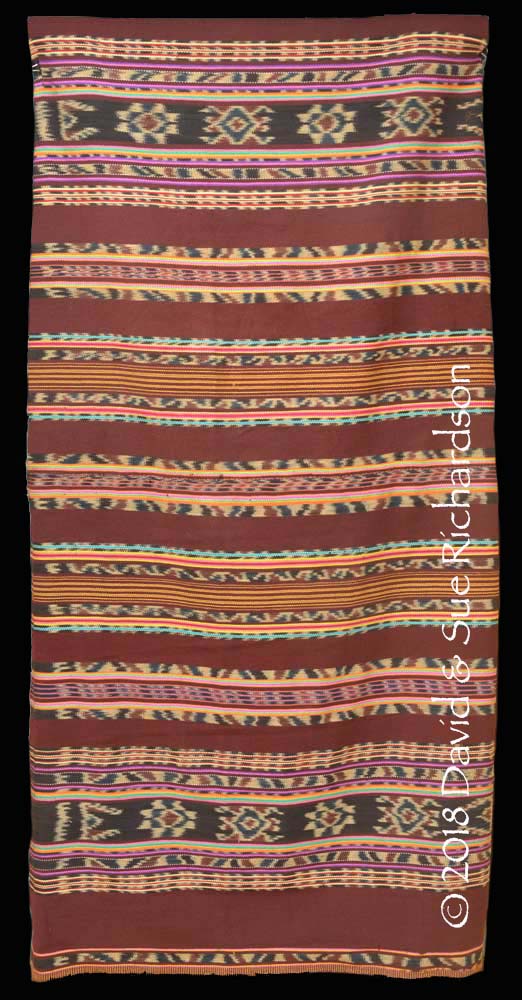

A kafate bélang woven on Buaya over 40 years ago by Siti Ibrahim from suku Uma Tukang. Richardson Collection

The second example has a very similar layout but quite different motifs, as does the third.

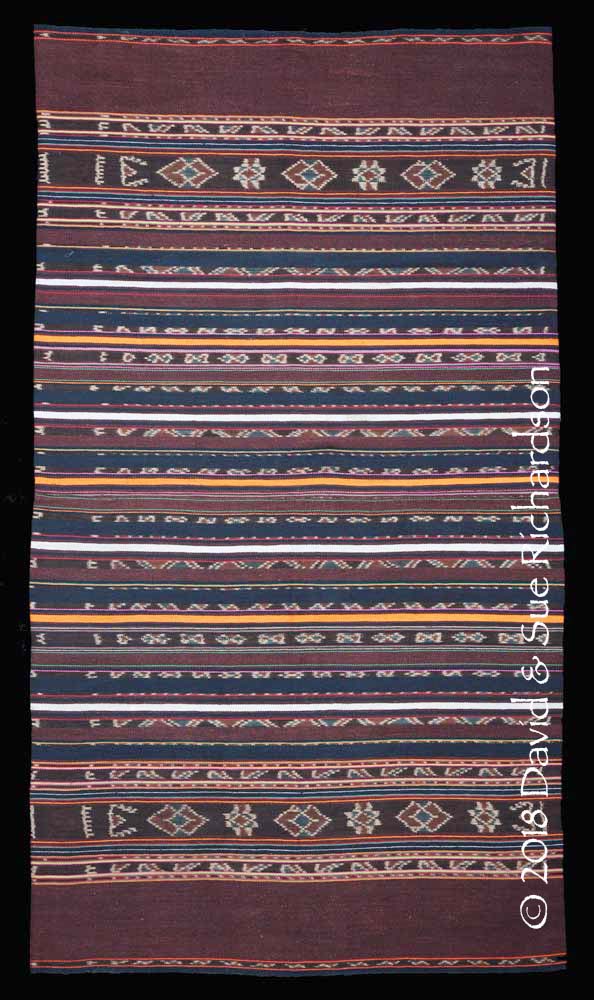

A kafate bélang woven on Buaya in 2002 by Sahari Kasim, from suku Uma Tukang

Richardson Collection

A kafate bélang belonging to a weaver on Buaya

It would be interesting to locate an antique version of this pattern from Ternate to see if in the past the orange stripes were coloured using turmeric mixed with lime powder or apu (see Yellow Dyes - Turmeric).

Return to Top

Tenapi Matang Kari

The tenapi matang kari is distinguished by two alternating narrow bands of ikat separated by clusters of narrow stripes that are arranged around a central stripe of simple ikat decorated with a row of spots or eyes. Some of the stripes are often pink or brown.

On Buaya, matang kari means small eyes, matang meaning eye in Buaya Alorese (Sulistyono 2018) and kari meaning thin in Alorese (Klamer 2012, 92). The ‘eyes’ can be grouped into threes, telo matang, or fours, pa matang. The flanking pink or brown stripes are called kaluma. As before, the main motif is irrelevant in describing the textile.

These tenapi matang kari were traditionally made and worn by suku Uma Aring, the clan with the third highest status below Kakang and Tukang. Today it is a custom to make a gift of a tenapi matang kari to a daughter who is getting married, no matter which suku she belongs to. Although such sarongs can now be made by any clan, it is still the case that weavers from suku Uma Aring produce many of the sarongs that are used as wedding gifts by the other clans.

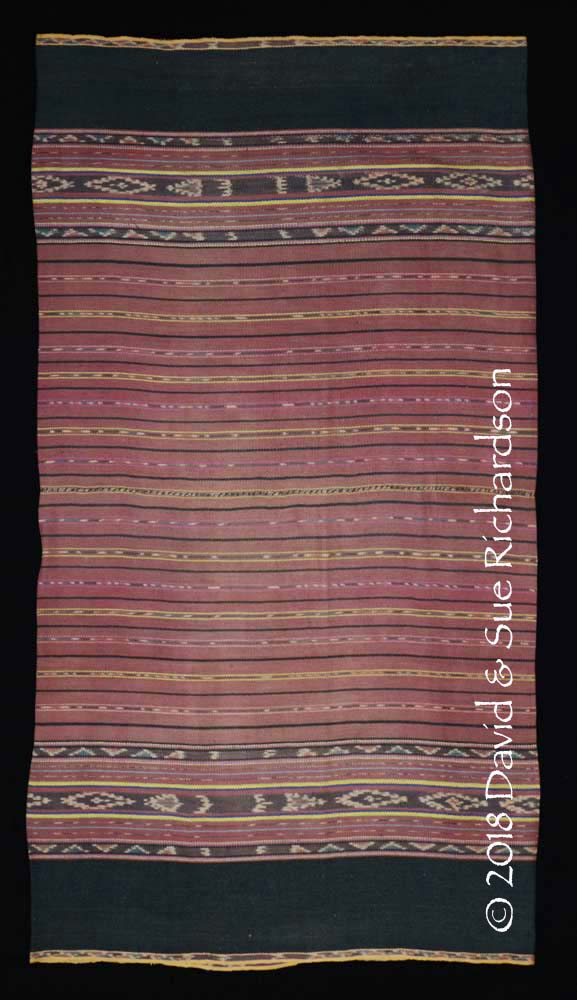

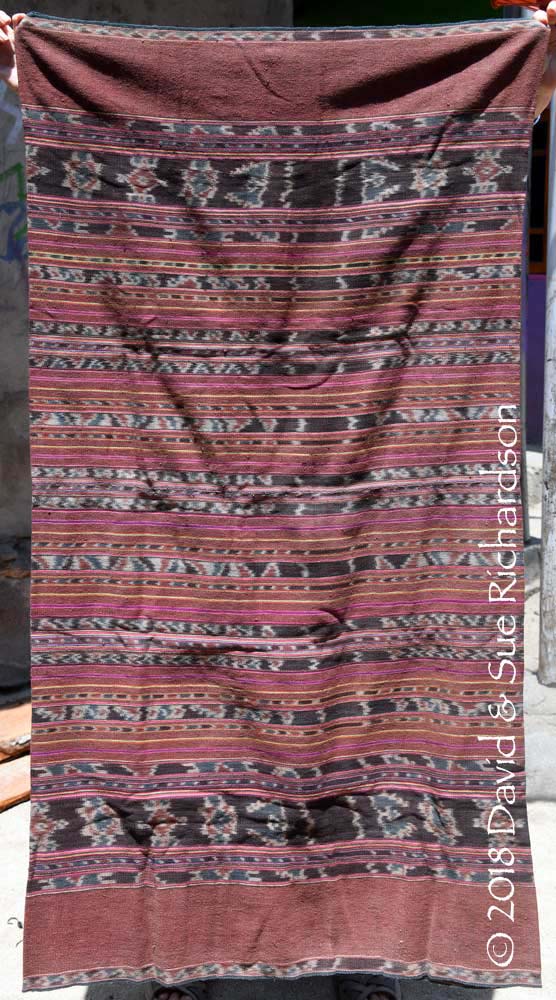

A tenapi matang kari woven in Uma Pura, Ternate

The main ikat band has the Baololong pisah (separated) layout

There is also a closely related tenapi matang béing, meaning big eyes, in which the central stripe of simple ikat has larger dots or dashes.

Return to Top

Kafate Sontoraja

The kafate sontoraja is distinguished by a centre field containing three groups of three narrow bands of ikat, the two outer bands with matching motifs that differ from those in the central band. This is similar to the arrangement of bands in the kafate tenemang, except in this case, the three bands are generally separated by several plain warp stripes.

It is possible that the kafate sontoraja was previously associated with suku Léing Papa.

In the first example below, the triple bands of ikat are separated by two extra ikat bands flanked by purple stripes.

A rather coarse kafate sontoraja belonging to a weaver on Buaya

A very old and more refined tenapi sontoraja from Alor Kecil

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Tenapi Muko Tahakang

The tenapi muko tahakang is distinguished by pairs of narrow yellow and lime green warp stripes, hence the appellation muko tahakang – ripe banana, muku meaning banana in Buaya Alorese (Sulistyono 2018) and tahakang meaning ripe in Alorese (Klamer 2011, 46). Interestingly Muko Tahakang happens to be one of the mythical ancestors in the creation myth of Uma Pura (Wellfelt 2007, 39).

This pattern was associated with suku Sebanjar Jawa, sometimes called Deng Wahi, the lowest status clan in the first moiety.

A tenapi muko tahakang woven by Dahlia at Uma Pura over 20 years ago. The plum-coloured dye is extracted from kusambi bark. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Kafate Bul Ihing Launjia

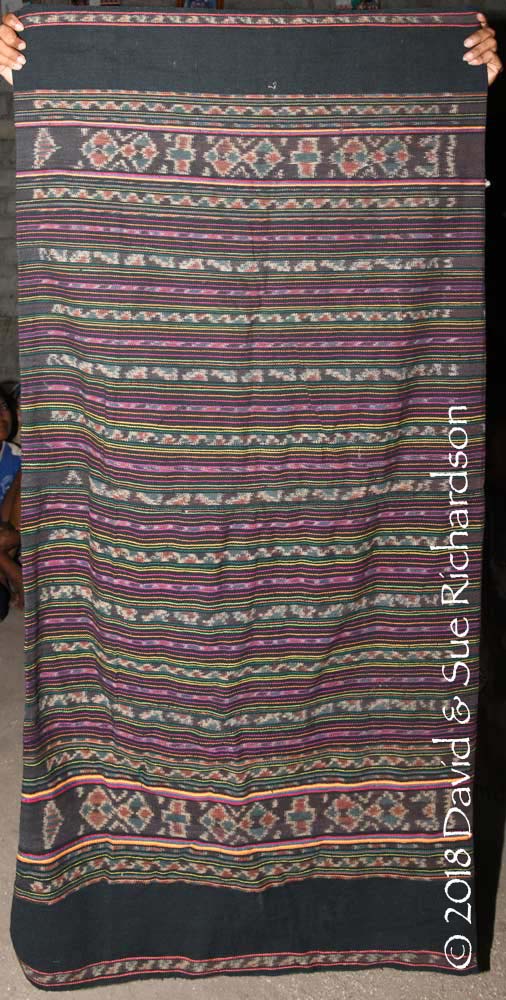

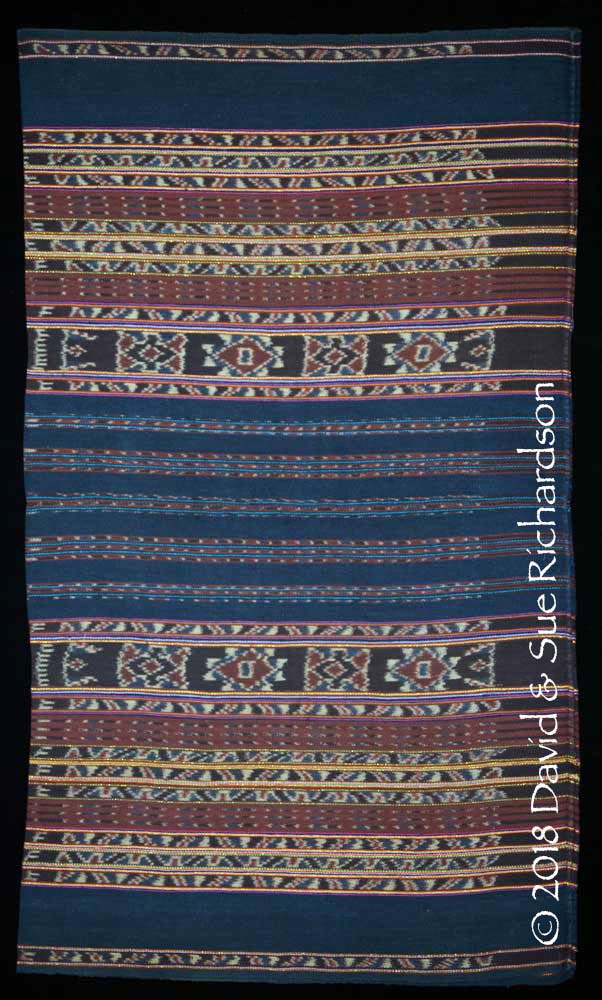

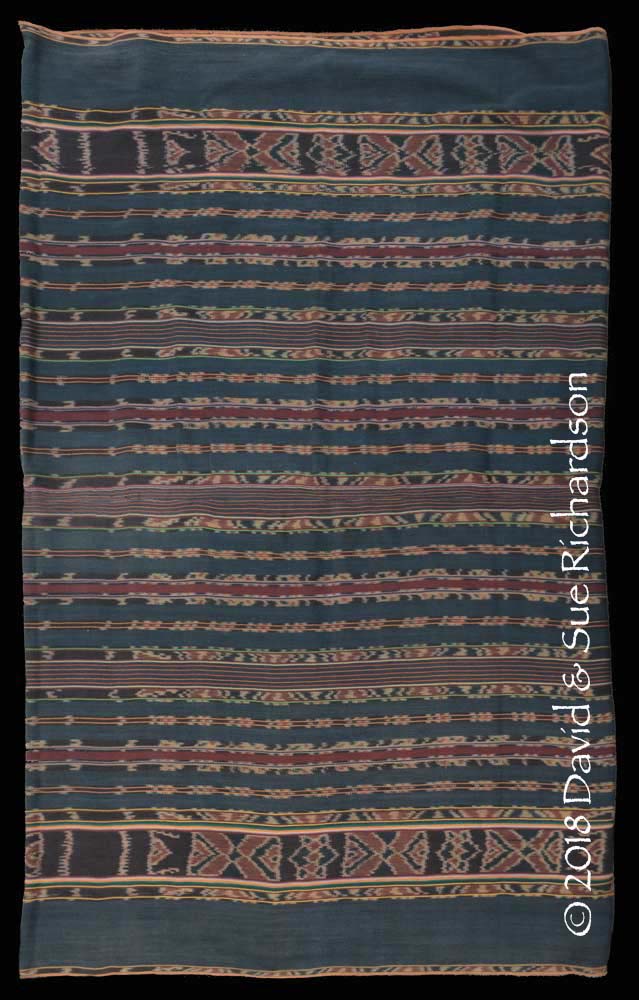

The kafate bul ihing launjia is distinguished by bands filled with clusters of narrow alternating plain and ikatted warp stripes. These are arranged as a pair towards the outer edge of each panel. There are normally three or four ikatted stripes within each band decorated with simple dashes. Once again the motifs can be radically different, as demonstrated by the comparison of four different kafate bul ihing launjia from neighbouring Ternate.

Four completely different kafate bul ihing at Uma Pura, Ternate

The kafate bul ihing launjia is specifically associated with suku Fil Falu Kana Béing.

Weavers on Buaya say that the term bul ihing launjia has no meaning. Interestingly in Lamaholot ihing can mean crops or harvest.

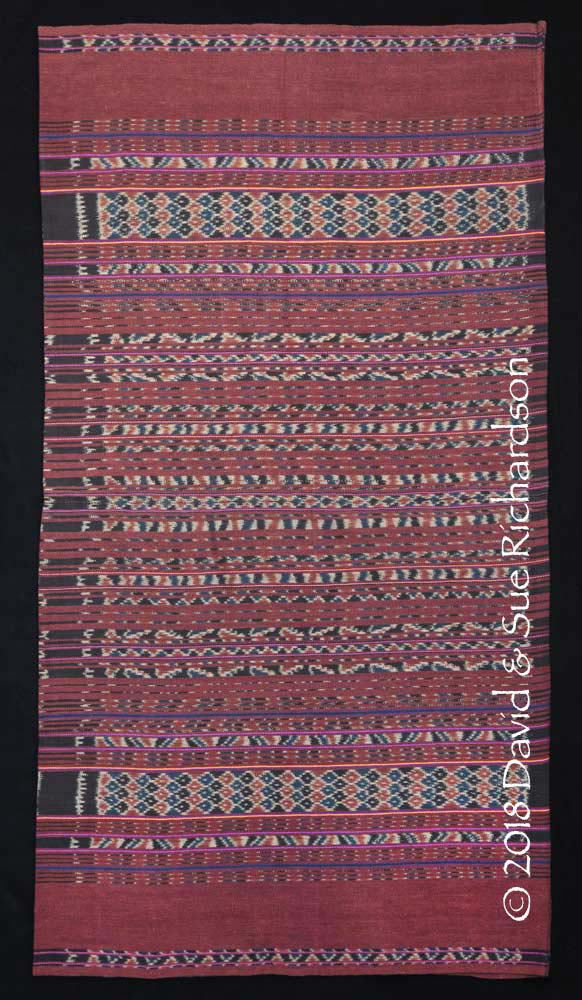

A kafate bul ihing launjia woven on Buaya by Mome Mustapa

Richardson Collection, acquired in 2004

The example below has a main ikat band decorated with a Baulolong pattern that includes the ufe kotong motif, kotong meaning head (Sulistyono 2018; Klamer 2011, 55). It is composed of a central diamond flanked by a pair of triangles.

A kafate bul ihing launjia woven on Buaya in 1993/4 by Nurwati Kamran from suku Fil Falu Kana Béing when she was around 15 or 16 years old. Richardson Collection

A kafate bul ihing launjia woven on Buaya in 1993 by Mama Loni Sardin from suku Fil Falu Kana Béing. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Kafate Leor Manis

The kafate leor manis is distinguished by a centre field filled with triplets of narrow stripes, each composed of a central stripe of ikat decorated with dashes flanked by a pair of plain warp stripes. The central ikat stripe is called leor manis.

A kafate leor manis from Uma Pura, Ternate

Museum of One Thousand Mokos, Kalabahi

In the past the kafate leor manis was restricted to suku Fil Falu Folang.

One variant of this style of sarong is the kafate bélang papa. Weavers on Buaya say the name has no meaning and they inherited it from their ancestors. The example below was collected in 2004 and has an elongated diamond-shaped motif symbolising the bitter gourd or cucumber, known in Indonesia as the paria isi (Momordica charantia). On Buaya it is called utang péi, péi meaning bitter in Buaya Alorese (Sulistyono 2018) and utang meaning vegetable in Bahasa Blagar (Steinhauer and Gomang 2016, 103).

Utang péi was a common motif for suku Fil Falu Folang.

A kafate bélang papa made by a weaver from suku Fil Falu Folang

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Kafate Sinta Galla

We have yet to locate a kafate sinta galla on Buaya Island.

Sinta means love in Bahasa Blagar (Steinhauer and Gomang 2016, 90).

It is possible such designs were associated with suku Barfahing Sebanjar, also known as suku Defahing.

Return to Top

Kafate Mobehe

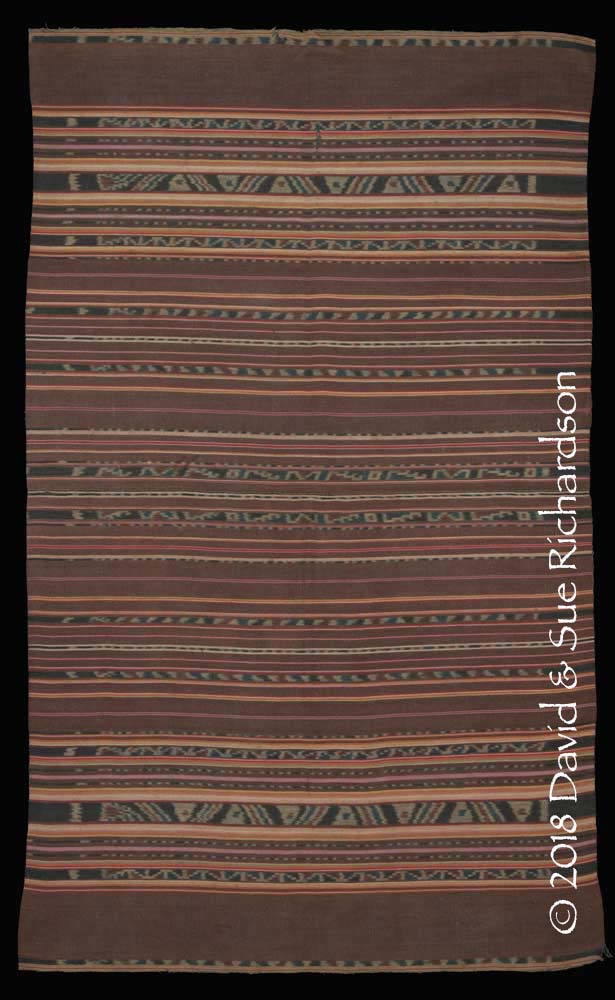

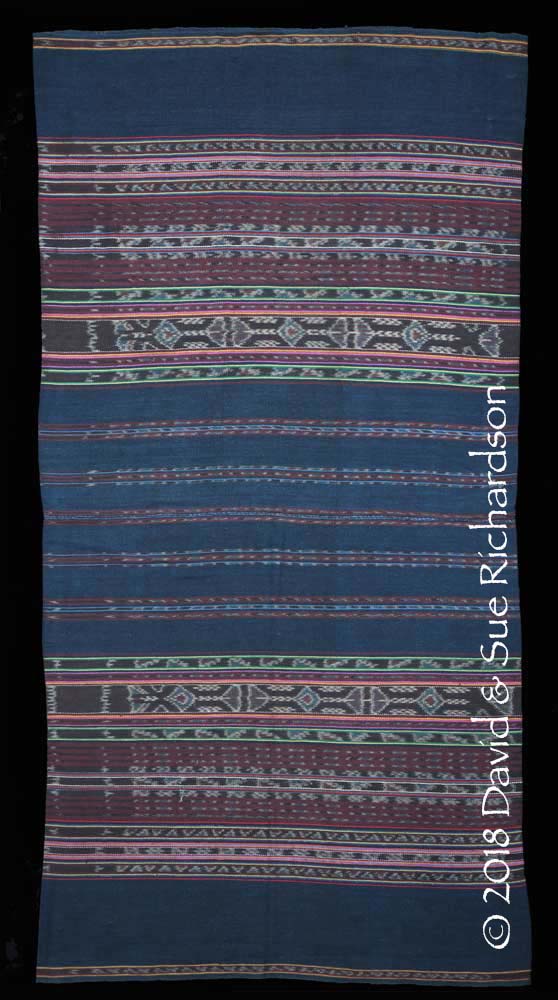

The kafate mobehe is distinguished by a number of secondary bands composed of clusters of narrow plain or sometimes dashed stripes. The stripes alternate in colour and in number they can range from 5 to 21. The term mobehe appears to have no translation, but refers to the specific clusters of warp stripes. The motifs in the main ikat band can vary enormously.

In Bahasa Blagar a behe is a palm leaf and mo- means on the other side, thus the underside of a palm leaf (Steinhauer and Gomang 2016, 119 and 215).

A kafate mobehe from Buaya with the rectangular nasi (pineapple) motif

(Private Collection, Kalabahi)

A quite different looking example from neighbouring Ternate is also decorated with the pineapple motif and the cross-shaped anchor (jangka).

A kafate mobehe belonging to a weaver on Ternate.

A kafate mobehe from Ternate.

Richardson Collection

Another kafate mobehe from Ternate.

Museum of One Thousand Mokos, Kalabahi, Alor

Return to Top

Tenapi Tenamang

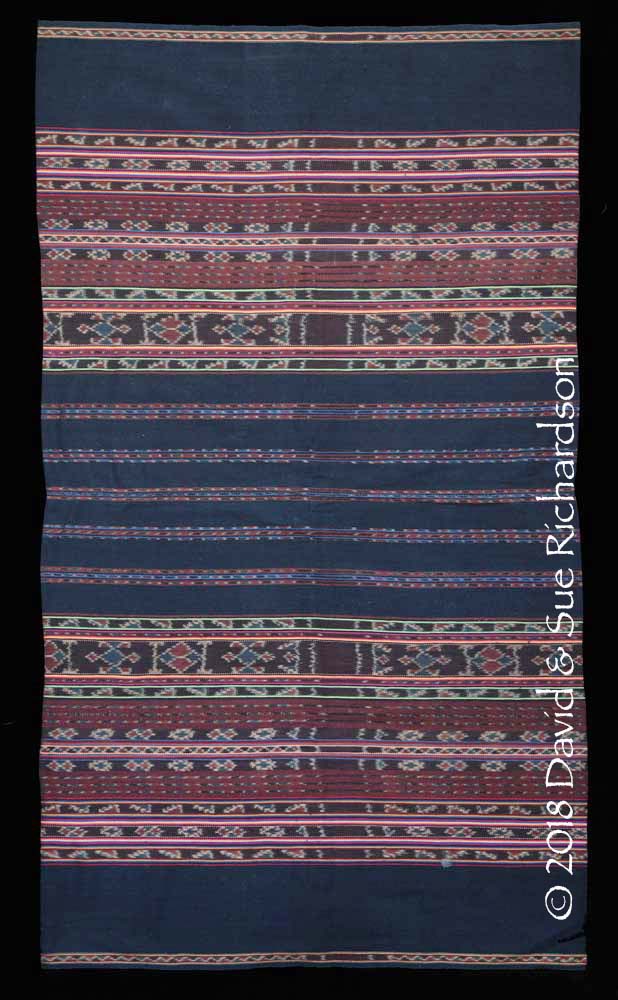

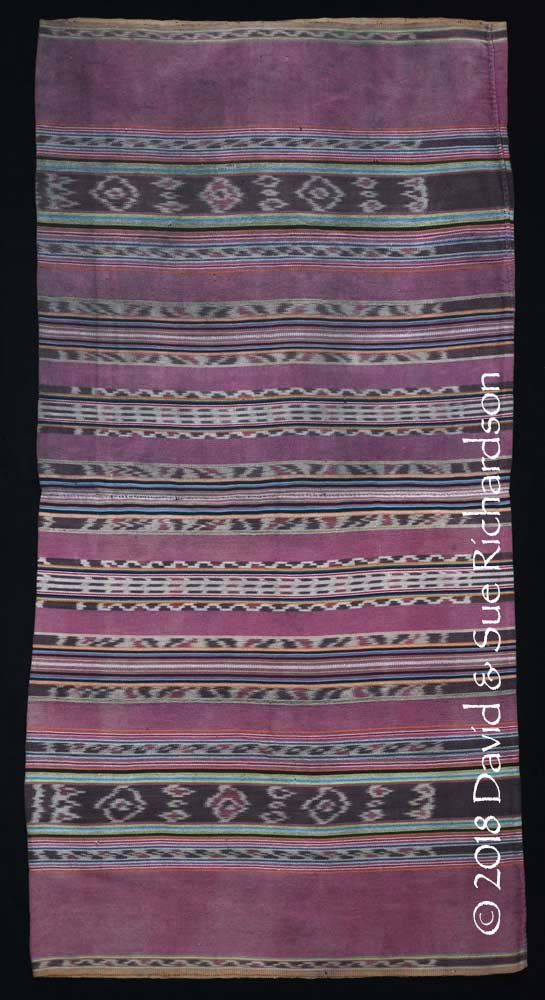

The tenapi tenamang is distinguished by a centre field filled with repetitive clusters of three narrow bands of ikat, the two outer bands matching but differing from the central band. Generally two different sets of triple bands alternate between one another, each decorated with different motifs.

It is not clear whether tenamang has the same meaning as it does in Bahasa Blagar, where it means 'just ripe' (Steinhauer and Gomang 2016, 209 and 246).

The tenapi tenamang does not appear to be a traditional pattern linked to any one of the eight clans.

A heavy tenapi tenamang belonging to a weaver on Buaya

As an example of the minefield of classification used on Buaya Island (and the other weaving communities in the Pantar Strait), although the example below is described by its maker as a tenapi tenamang, it also contains clusters of the narrow plain and ikatted warp stripes in its end sections that are normally associated with the kafate bul ihing launjia.

A tenapi tenamang woven in 2002 by Nursa Bakar from suku Uma Tukang

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Nofang

Buaya weavers produce relatively few blankets compared to sarongs. They are known as nofang, a term similar to the Blagar word for a man’s hip wrapper, noang (Steinhauer and Gomang 2016, 217). It is less close to the Lamaholot word for a man’s hip wrapper, nowing.

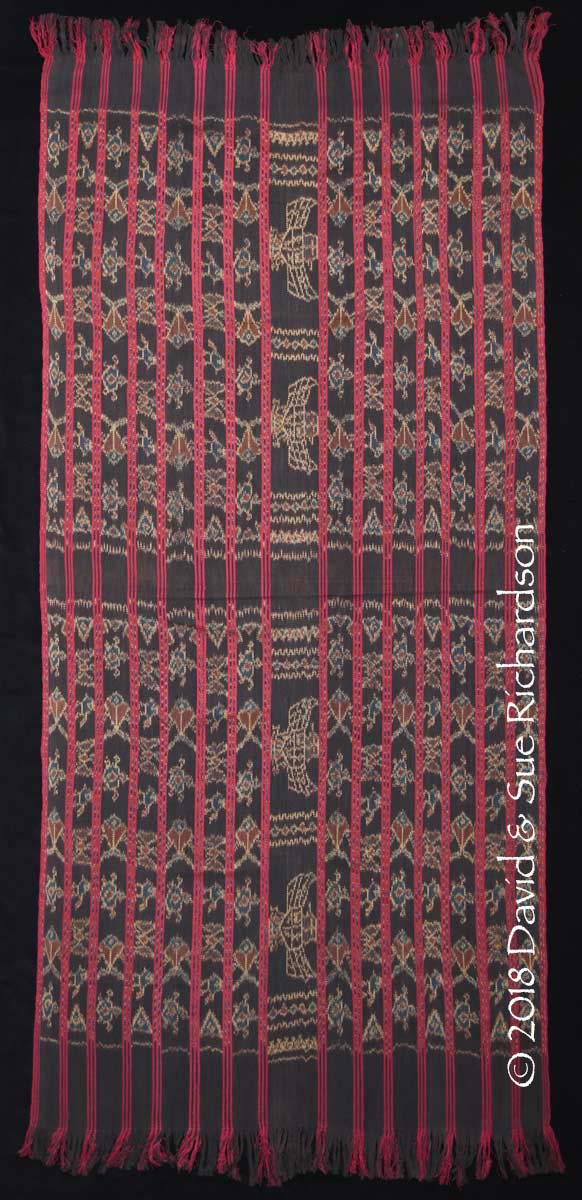

The blanket below was woven by Samira Musa, who lives next to the Al Ijtihad mosque. She decorated it with a central band containing a row of Garuda motifs, symbolising the Garuda Pancasila, the national emblem of Indonesia. The side bands have rows of fish and turtles alternating with rows of birds and butterflies.

A nofang béing, a big unisex sleeping blanket woven by Samira Musa from suku Deng Wahi

in 2017. Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Bibliography

Alelang, Yanti, 2018. Personal communications, Museum Seribu Mokos (Museum of One Thousand Mokos), Kalabahi, Alor.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor 2018. Kecamatan Alor Barat Laut dalam Angka 2017, Kalabahi.

Baron van Lynden, D. W. C., 1851. Bijdrage tot de kennis van Solor, Allor, Rotti, Savoe en omliggende eilanden, Natuurkundig tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië, vo. 2, pp. 317-336.

Findlay, Alexander George, 1878. A Directory for the Navigation of the Indian Archipelago, China, and Japan, from the Straits of Malacca and Sunda, and the Passages East of Java, R. H. Laurie, London.

Fitriana, Ria, 2014. Assessing the impact of a marine protected area on coastal livelihoods: A case study from Pantar Island, Indonesia, Ph. D. Thesis, Charles Darwin University.

Gomang, Syarifuddin R., 1993. The people of Alor and their alliances in eastern Indonesia: a study in political sociology, MA Thesis, University of Wollongong, New South Wales.

Gomang, Syarifuddin R., 2006. Muslim and Christian alliances ‘Familial relationships’ between inland and coastal peoples of the Belagar community in eastern Indonesia, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vols 162-4, pp. 468-489.

Indrawati, Klara Puspa, 2016. The Sea around ‘Alor Kecil’ Vernacular Society: A critical threshold for ecological and cultural survival, ISVS e-journal, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 1-15.

Departement van Overzeese Rijksdelen, 1908. Jaarboek van het mijnwezen in Nederlandsch-Indië, C.F. Stember.

Kasim, Dahlia Syahbudin, 2019. Mengunjungi Desa Pulau Buaya di Kabupaten Alor, Universitas Muhammadiyah, Kupang, Kompasiana.

Klamer, Marian, 2010. From Lamaholot to Alorese: Simplification without Shift, Austronesian Undressed: How and Why Languages Become Isolating, DeGruyter, Berlin.

Klamer, Marian, 2011. A short grammar of Alorese (Austronesian), Lincom Europa, Munich.

Klamer, Marian, 2012. Papuan-Austronesian language contact: Alorese from an areal perspective, Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century, pp. 72-108, University of Hawai‘i Press.

Klamer, Marian, 2017. The Alor-Pantar Languages: History and Typology, Language Science Press, Berlin.

Ricklefs, Merle Calvin, 1993. A History of Modern Indonesia since c-1300, Macmillan Press, Basingstoke.

Sulistyono, Yunus, 2018. Language Alorese, Buaya, LexiRumah 3.0.0, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Leiden. Available online at https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/alor1247-buaya

Sulistyono, Yunus, 2019. Personal communications, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics, Leiden.

Wellfelt, Emilie 2007. Diversity & Shared Identity: A case study of interreligious relations in Alor, Eastern Indonesia, MA Thesis, Göteborg University.

Wellfelt, Emilie 2019. Personal communications, Stockholm University.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 1 December 2019.