Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production in the Past

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production Today

Terminology

Women's Costume

The Kewatek Miten

The Kewatek Lamakera

The Kewatek Kenuma

The Kewatek Makassar

The Kewatek Mowak

The Kewatek Méa

The Tenapa

Bridewealth Sarongs

Dance Costume

Men's Costume

The Senai Miten

The Nowin

The Senai Méa

The Mét

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Go to: Ilé Mandiri

Introduction

The Ilé Mandiri Region

The Baipito and Larantuka Myth of Origin

A Limited Early History of Baipito

Ilé Mandiri in 1928

Ilé Mandiri in 1950s

The Ilé Mandiri Clan System

Marriage and Bridewealth

Bibliography

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production in the Past

The eastern end of Flores Island, now the mainland part of East Flores Regency, had a rich material culture related to the crafting of warp ikat textiles. The traditional multi-striped cotton textiles made by its womenfolk are richly coloured and subtlety decorated, made from local hand-spun cotton that was naturally dyed.

There are six separate weaving districts in mainland East Flores – Tanjung Bunga, Ilé Mandiri, Lewolema, Demon Pagong, Titihena and Ilé Bura – each with their own types of textiles, costume terminology and motifs. Regrettably much of the literature published on Indonesian textiles takes a simplistic approach to this complex region and attributes many of its textiles to just the one district of Ilé Mandiri.

This webpage focuses only on those textiles that really do only come from the Ilé Mandiri region. We seek to build a collection that is a serious scholarly resource so provenance is absolutely essential. We therefore prioritise collecting textiles in the field, not from dealers or auction houses, acquiring the majority of them from families who know their history, having previously inherited them from their mothers and grandmothers.

We first visited the beautiful Ilé Mandiri region in 2004 but only later, in 2013, conducted a survey of weavers in the seven Baipito villages starting in Lewoloba in the west and finishing in Mudakaputu in the east. We discovered that by then, hardly any local women were still hand-spinning cotton or producing natural dyes. The textiles being woven bore little resemblance to those that had been made several decades previously. We were also struck by how the styles and motifs from this region were completely different from those of neighbouring Demon Pagong or Lewolema. Since 2013 we have revisited the area once or twice every year until the cancellation of our visit scheduled for May 2020. We plan to return soon.

Being a relatively low-lying region with an extensive coastline, eastern Flores has been an ideal location for making textiles, with cotton, indigo, morinda and candlenut growing plentifully.

Cotton

Native tree cotton (Gossypium arboreum) once thrived in this region, but is no longer cultivated. Vatter observed that among the Lamaholot it was grown locally in the villagers' gardens, or sometimes bought as raw cotton from traders on the coast (1932, 218). During his sojourn in Lewoloba in 1928 he observed and photographed the village girls and women preparing their cotton.

"The sun is high and burns down hot and scorching. The spaces between the houses have become empty, and those who are still working have long sought the shade. The women and girls sit under the protruding roof of the house, they spin the drop spindle in their hands, or turn the spinning wheel, or weave a basket, others pluck the cotton with a bow to make it loose and fluffy, or they are are ikatting" (1932, 67).

Cotton (kapas) was picked several months into the dry season, around May and June, after the bolls (kapas lolon) had set. It could be processed there and then, or fully dried and stored in baskets for later use.

A basket of cotton bolls on a bale outside of a house in Lewoloba in December, with a man about to head off to tap palm juice. Vatter 1928

The first task was to remove the cotton seeds using the wooden menalo, a mechanical gin with two bolen rollers linked by carved helical gears and turned by a crank. The black cottonseed was collected in a basket for planting at the start of the following rainy season. Sometimes for stability, the menalo was attached to an aran board on which the operator sat.

Removing cotton seeds with a mechanical roller gin, Vatter 1928

Now the cotton fibres could be cleaned and fluffed using a stringed bow that was plucked with the fingers or with a pick.

A young girl fluffing cotton fibres with a stringed bow. Vatter 1928

Cotton was locally spun using either a keturé drop spindle or a muté spinning wheel. In 1928 girls aged ten or even less appeared to be proficient with the use of either.

Thanks to Baipito’s closeness to the port of Larantuka, it is probable that spinning wheels were introduced before the arrival of the Dutch, perhaps by maritime traders from Java or Makassar. Sanskrit sources suggest that it was introduced into the Malay Peninsula from India, and reached South Sulawesi and Maluku by 1600 (Clarence-Smith 2011, 141).

A young Lamaholot girl drop-spinning. Vatter 1928

A woman cranking her spinning wheel on a bale inside her house in Lewoloba. She holds a wad of fibres in her left hand and one end of the spindle between her toes. Vatter 1928

Once the yarn is spun it was either rolled into balls directly from the spindle or stretched on the H-shaped belawa niddy-noddy, which helped set the twist while allowing the weaver to measure the length of the skein.

In Wailolong in 1950 they were still growing their cotton locally and spinning it using both the spindle and the wheel (Kennedy 1953, 43). The women drop-spun their cotton as they walked.

The Binding Process

In the past the yarn bundles were bound with strips of gebang palm cut from dried leaves of the cabbage palm (Corypha utan). In Vatter’s words:

A certain number of threads, which are stretched next to each other on a four-sided wooden frame, are carefully counted and then the area that is to be protected in the first dye bath is tightly wrapped with a fine strip of gebang palm leaf.

A woman binding her yarns on the raised bamboo baleh platform beside her house in Lewoloba

Photographed by Ernst Vatter in 1928

Indigo

Around Ilé Mandiri the term for indigo is taun. Vatter recorded the Solorese word as tá‘ung. In the past indigo grew like a weed everywhere.

In Lewoloba, Vatter noted:

In front of another house, dye is being made: a black, round-bellied pot stands on the baleh and a woman, whose hands and forearms are dyed blue-black, stirs it with a wooden stick. The disgusting, sweet smell announces that an indigo solution is being prepared here; the small leaflets of the indigo bush, which can be seen growing everywhere on the house walls and in the open spaces in the village, are soaked in water until fermentation occurs, whereupon the dye is produced by adding lime. The pots are not made in the village, but bought or bartered on the market (1932, 67-68).

The ceramic pots were made in the coastal kampong of Lewoleri near Waibalun, just west of Larantuka.

Indigo was primarily used to dye everyday women’s sarongs and men’s senai.

Morinda

Being a more complex and time-consuming process, morinda root was used to dye festival and bridewealth sarongs and men’s ceremonial senai. In Lewohala the term for morinda is keroré. Verheijen recorded exactly the same name for morinda in his survey of plant names in the East Flores-Solor-Adonara-Lembata region (1990, 165). At Ilé Mandiri Vatter recorded the name as kerorä. In the villages of Baipito, morinda grows in the yards around the houses. The best time to harvest morinda root is when the leaves fall from the trees, usually in September.

Before dyeing with keroré the weavers first treat their yarns with bark from the rerat tree that grows in the mountains. This appears to be a local Ilé Mandiri name for Symplocos, the species of tree whose leaves and bark contains the metal mordant aluminium (known elsewhere of Flores as lobha). The rerat bark is mixed with crushed candlenut and the yarns are steeped in the cold mix for three days before drying. Weavers told us that they must use a clay pot for making keroré dye. Yarns are dyed multiple times and dried thoroughly between each immersion.

Vatter gave a general overview of the process for dyeing morinda in the Solor Islands (East Flores to Lembata). In this the crushed bark of morinda root was mixed with water and the crushed bark or the crushed leaves of the roma tree, another local term for Symplocos. The yarns were immersed for two days. In nearby west Solor they mix chopped and dried morinda root with dry pounded roma leaves in a ratio of 10:1 before adding chewed candlenut and water.

Baipito in 1950

By 1950 little had changed since Vatter’s visit in 1928. The houses in Wailolong were exactly the same and women still sat on the bale platforms under the roof overhang or in front to perform their daily chores (Kennedy 1953, 43).

Cloth was woven on ‘the regular horizontal back-bar loom’ and was heavy, always ikatted and was mostly blue and black. Different designs were used for men and women but the designs were ‘even poorer than those in Ende’. It took about a year to make a cloth, i.e. sarong. Kennedy was clearly not that interested in textiles and in his opinion: ‘the arts here are poor in all ways’ (1953, 47).

Return to Top

Ilé Mandiri Textile Production Today

Since 1950 there has been a revolution in local weaving and all the traditional methods of cotton production and natural dyeing have almost been lost. Now machine-spun yarn, both cotton and synthetic, is purchased in Larantuka and coloured with commercial chemical dyes. The textiles have lost the subtlety and deep tones of the past and new motifs have been introduced.

In Lewoloba there is now a small local weaving group called Kelompok Tenun led by Mama Maria Ogrimita. However only eight people are involved and they are all using commercial yarns.

Warping up synthetically dyed yarns in Lewoloba

The accuracy of the binding on the wider ikat bands is not as fine as it was in the past. It is clear that the village no longer has the critical mass of weavers required to maintain the high standards of the past.

A modern kewatek méa woven by Marianne Ogaritan in Lewoloba

Above and below: some of the cloth being woven in Lewoloba in 2013

In Riang Kemie we interviewed Elisabeth Letek Molang and her mother Fatima Molang. They were weaving modern chemically dyed cloths, some embellished with gold lurex thread. They confirmed that they no longer made natural dyes in that village. Fatima’s neighbour offered to give us a demonstration of drop-spinning, but the yarns on her spindle were commercial and mechanically spun!

The sarongs made in this kampong differed from those in the other Baipito villages. This raises the question as to whether this was also the case in the past. The ancestors of this village were not indigenous to the Ilé Mandiri region, but were later immigrants from the twin islands of Lapan Batan, located to the north of Western Pantar.

They made two types of sarong in Riang Kemie, known locally as ago not kewatek:

- an ago satu, for ceremonial use, was made in two versions, red and blue, and

- an ago Lamakera, also known as an ago Makassar, a lower-status sarong, was sometimes decorated with lurex.

However they no longer prepared natural dyes and only used commercial cotton yarn.

Above and below: two modern ago satu from Riang Kemie, both decorated with a similar motif. The upper sarong has a complete rewot.

When we visited Lewohala in 2013 we were told that there was very little weaving in the village, which seemed surprising.

However in Mudakaputu more than twenty women were still weaving - although they did so independently in their own homes, which were rather scattered. There had previously been a weaving group, but it had been dissolved because of a lack of visitors. Here the main weaving season was after the harvest between May and September.

We first visited this village in 2004, when some weavers were still producing traditional cloths. At that time we were shown a recently made sarong woven from locally grown cotton dyed with indigo and morinda. However the owner complained that the indigo made the cotton become rough and dry. In another house a woman was weaving a chemically-dyed sarong from commercial cotton on a back-tension loom. She had secured the warp beam behind the table legs and the foot rest in front of them, helping with the tension. She had fastened the warps to short sticks to lock the bands of ikat in alignment during the weaving process.

A woman weaving a kewatek méa inside her house at Mudakaputu in 2004

The alignment of the ikat locked in place using short wooden sticks

Again natural dyes had been superseded by synthetic dyes and new motifs had been introduced.

A modern kewatek méa woven in Mudakaputu around 2013

We were told that the ikat designs in each village are different and even today it is not possible to copy another village’s pattern. A weaver who did so would become insane!

Return to Top

Terminology

Because there is no uniform agreement on Lamaholot terminology, for simplicity we will use the terms miten for black and méa for red.

Vatter transliterated the local words into German as mittän and mäan, the umlauted ä pronounced like a clipped 'e' (1932, 52).

More recently Gregory Keraf recorded the term for black as mitǝn (with the 'uh' mid-central vowel) and red as mé'a in the Baipito dialect of Lamaholot and mitã and me?ã in the Lewolaga dialect (1978). For the same Ilé Mandiri region, Ruth Barnes used the terms miten and méan (2004, 130).

Michels recorded the western Lamaholot term for black as mite-n (2017, 53).

Akoli recorded the terms for black and red as mitẽ (the nasal e with a tilde diacritic) and me’ã in Lewoléma and mitǝ and me?ã in Waibalun (2010, 75 and 77).

Weking translates the Baipito word mea as brown (2018, 142).

Kroon recorded the terms spoken on Solor Island as mitẽ (the nasal e with a tilde diacritic) and me’ã (2016, 119).

Return to Top

Women's Costume

Over the last half-century the women of Baipito produced two classes of two-panel tubeskirt – the ago and the kewatek. Generally ago are simple everyday sarongs while kewatek are higher quality or ceremonial. Vatter only used the term kěwatäk (with a short e and ä pronounced ‘eh’). He never referred to an ago. One wonders if the latter is a more recent introduction, or a term previously only used in Riang Kemie.

Some of the women of Wailolong in their ceremonial kewatek méa and tenapa sarongs

Photographed by Viktor B. Hurint, the kepala desa of Wailolong

There are at least seven types of two-panel sarong produced in the Ilé Mandiri region, listed below in roughly increasing levels of status:

- the kewatek miten, an everyday sarong that was worn in the past, but fell out of use many decades ago,

- the ago klaor, which is patterned with very narrow stripes of dotted ikat.

- the ago Lamakera or kewatek Lamakera, an everyday sarong named after a village on Solor that today is always chemically dyed

- the kewatek kenuma

- the kewatek mowak

- the kewatek méa

- the tenapa

There also appears to have been a kewatek Makassar, which is generally not recognised today.

Not every village made all seven types. For example, they did not make an ago klaor in Lewohala.

In Baipito, clothing, jewellery, weapons and equipment were always personal and not clan property (Vatter 1932, 84).

Vatter left us a good overview of clothing in 1928 (51-52):

The clothing for both genders and all ages is the same, with the exception of small children up to four or five years of age who run around completely naked: [...] the sarong: a smooth, oblong, rectangular, sack-shaped skirt made of homewoven cotton. For children it consists of one cloth, and for adults usually two cloths sewn together. The everyday sarong is mostly dark blue or blue-black, dyed with indigo and only slightly animated by light rows of dots and dashes that were concealed during dyeing. The sarongs with a basic red-brown colour and wide, richly patterned graduated stripes in blue and brown-red tones, which we later saw at the dances and festivals, are more artistic. [...] The cut is the same for men's and women's sarongs, but the patterns are different [...] we distinguished five types of women's sarongs [...] The simplest are the kěwatäk mittän, i.e. the blue, actually black sarongs; the finest and most valuable, valued at up to 30 guilders, are the kěwatäk mäan, i.e. the red sarongs.

A sarong valued at 30 guilders in 1928 would be worth $750 today.

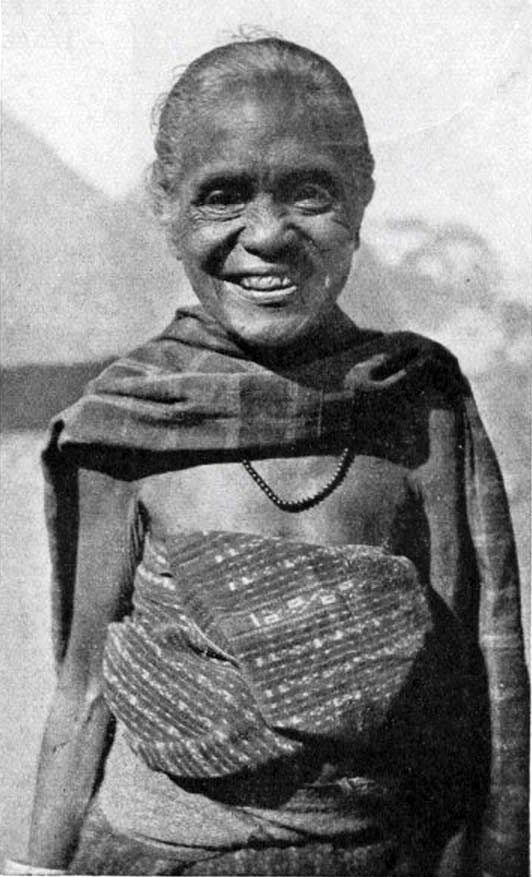

Vatter noted that the sarong could be worn in different ways and also served as a cloak, blanket and sleeping pad. For women it usually covered the chest but children went topless. It was pulled tightly forward over the buttocks, folded at the front and rolled over outwards over the hips or the breasts so that it held up without any further fastening (1932, 52).

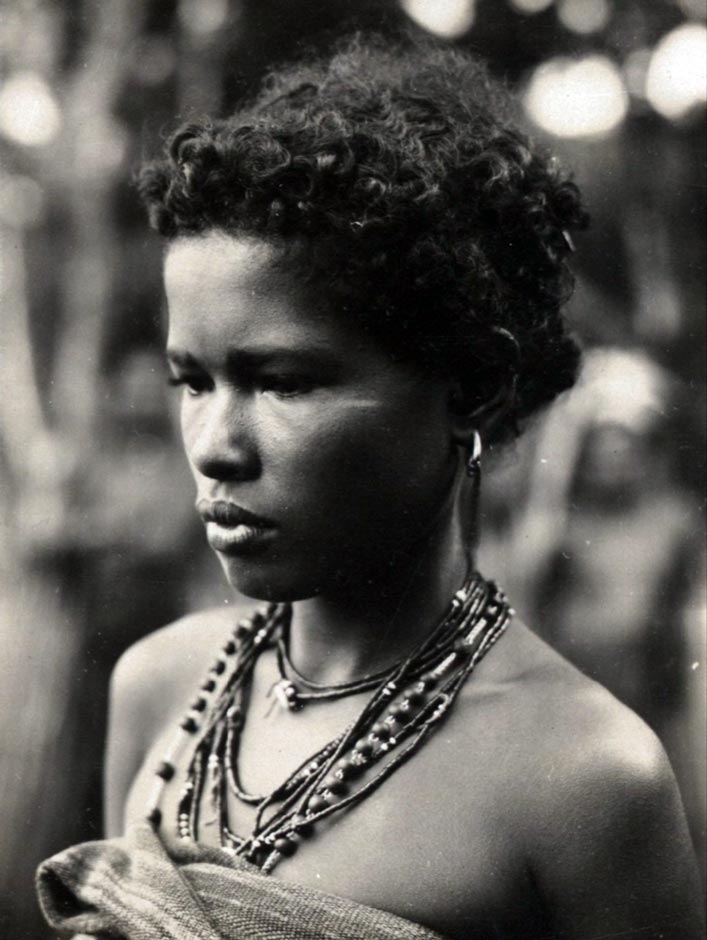

According to Vatter, women’s jewellery was conservative and ‘not very original’, mostly bought from a Chinese shop in Larantuka (1932). Necklaces were made of red and yellow beads or imitation corals, while bracelets were made of brass, white metal or bone.

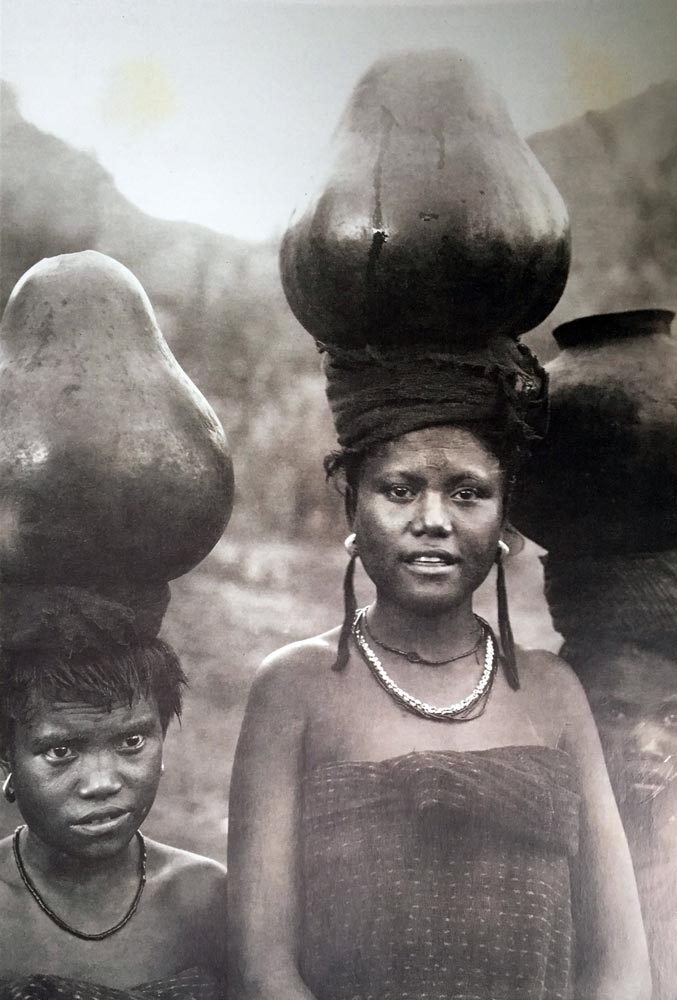

A woman from Lewoloba wearing necklaces. Vatter 1928

Horseshoe-shaped silver earrings called belàung were made by Islamic craftsmen in Lamahala on Adonara. Sometimes they were embellished with a tuft made from red cotton yarn that hung down to the shoulder. The only hair decoration was a small bamboo comb placed in the bun. Female dancers wore more elaborate headdresses that we will discuss later.

Return to Top

The Kewatek Miten

The kewatek miten or women’s black sarong was once extremely common, but is today quite rare, probably because they were worn repeatedly until they became rags.

As mentioned above, Vatter described these everyday sarongs as being mostly dark blue or blue-black, dyed with indigo and only slightly animated by light rows of ikatted dots and dashes. However many must have been extremely dirty. Given the lack of any sense of hygiene and complete uncleanliness, the same sarong was not only worn throughout the day but was slept in on the bale at night. It was also used to blow the nose, press the pus from wounds and wipe inflamed eyes.

Vatter took fewer photographs of women than of men during his stay at Ilé Mandiri, but those that he did show the everyday kewatek miten and how it was worn. The dark blue indigo cloth was simply decorated with parallel rows of narrow dashes spaced roughly 1½ cm apart. It seems likely that women would have previously gone bare-breasted, as on Lembata, but by 1928 had been encouraged to cover up by the local Catholic priests.

Women and girls wearing simple kewatek miten going to collect fresh water at Lewohala. Photographed by Vatter in 1928

Girls at Lewoloba wearing everyday kewatek miten on their way to collect water at a spring

By 1950 Kennedy leaves us with the impression that little had changed since 1928. The fabric woven for clothing was heavy, always ikatted and was mostly blue and black. In his opinion the designs were poor, ‘even poorer than those in Ende’ (1953, 47). However Kennedy was obsessed with social anthropology and showed little interest in weaving or costume. It appears he was never exposed to a local festival, so never encountered the more refined textiles.

Return to Top

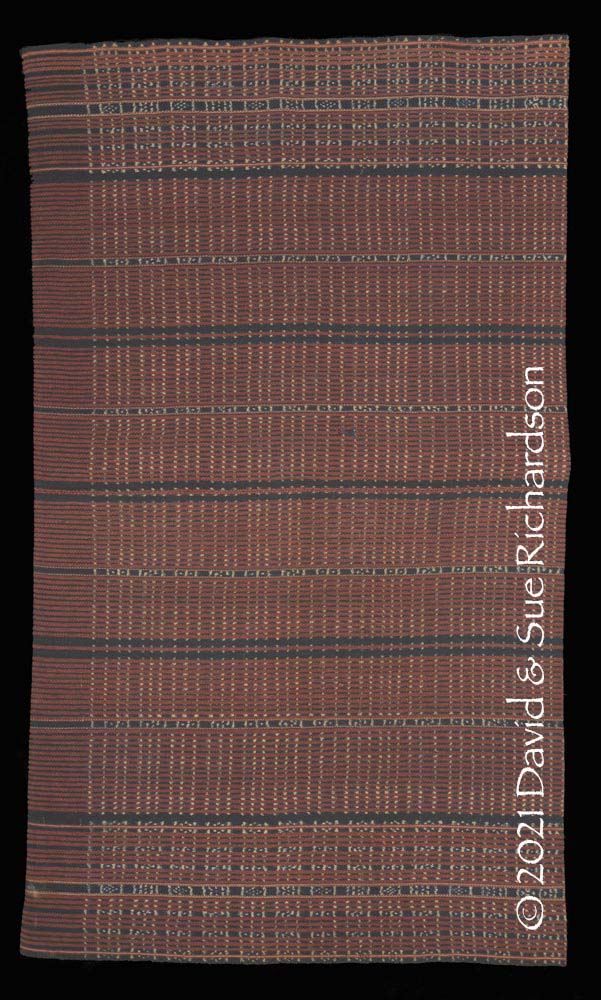

The Kewatek Lamakera

Local weavers informed us that the everyday ago or kewatek Lamakera was named after Lamakera, the Islamic whaling village on the eastern tip of Solor Island. Was this because the sarongs of eastern Solor were only decorated with narrow plain and ikatted stripes?

Such sarongs are known as ago Lamakera when worn for everyday use and kewatek Lamakera when worn ceremonially. In the later case, they are placed on the man’s shoulder to cushion the elephant tusk when it is exchanged for marriage. Today they are always chemically dyed and are therefore classified as ago Lamakera.

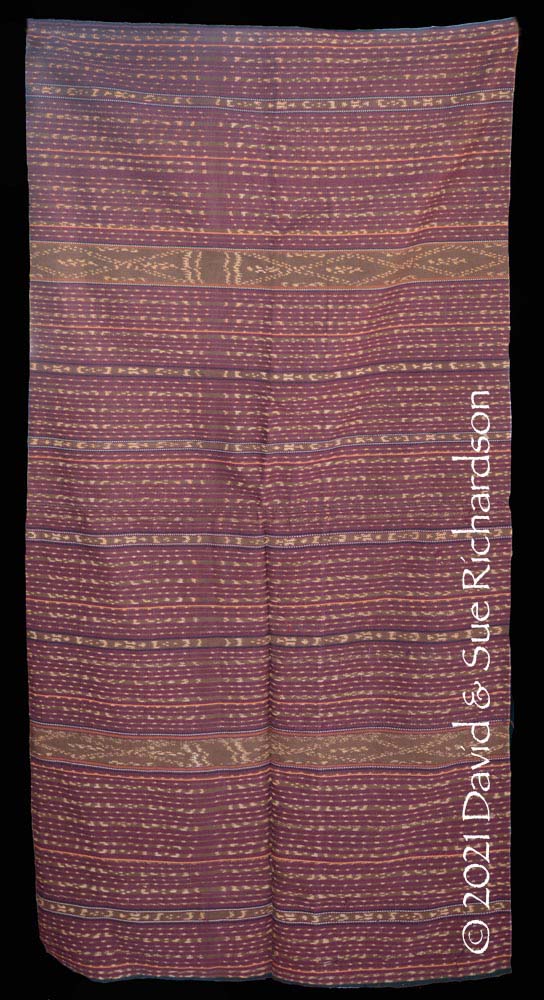

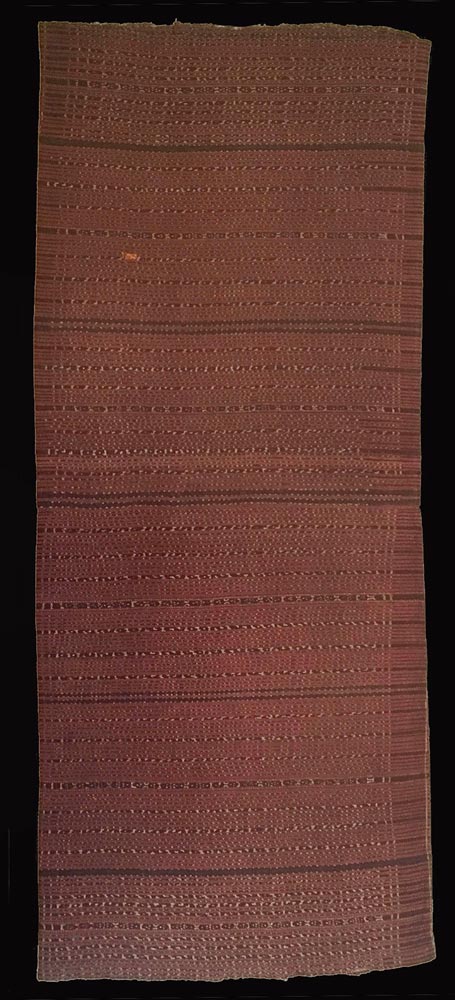

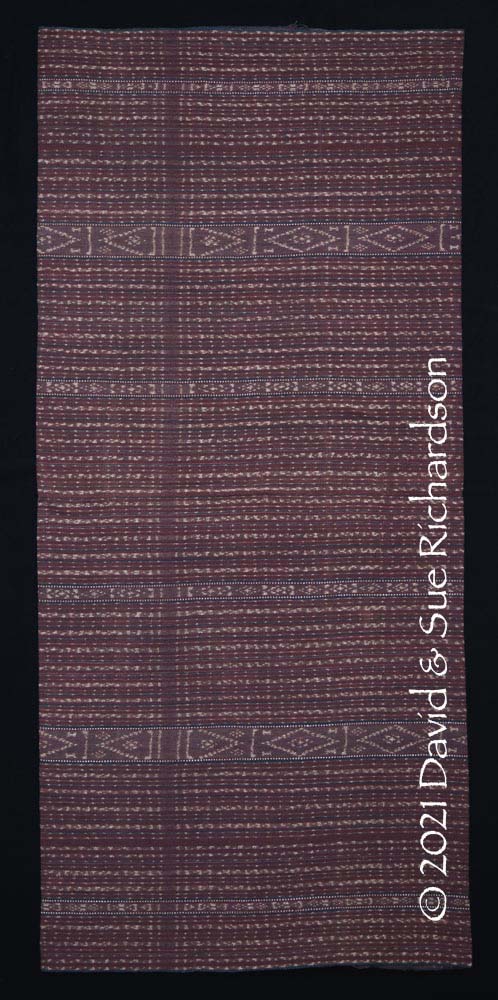

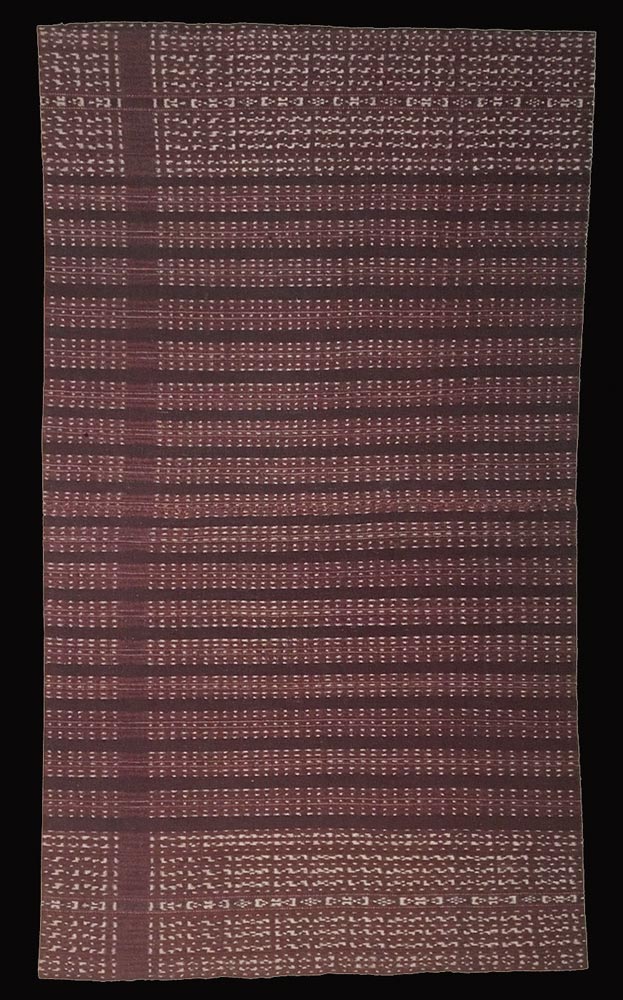

The hand-spun kewatek Lamakera from our collection illustrated below was made by Bole Lebuan of suku Lebuan in Lewohala. She was born in 1928 and wove it before she was married. The sarong is therefore between 60 and 70 years old. After she was married, Ibu Bole had four children but sadly died at the very young age of 51 in 1979, the year of the big Ilé Mandiri landslide that destroyed the neighbouring village to the east. The kewatek was acquired from her daughter-in-law, Ona Piré Piran, who was aged 61 at the time.

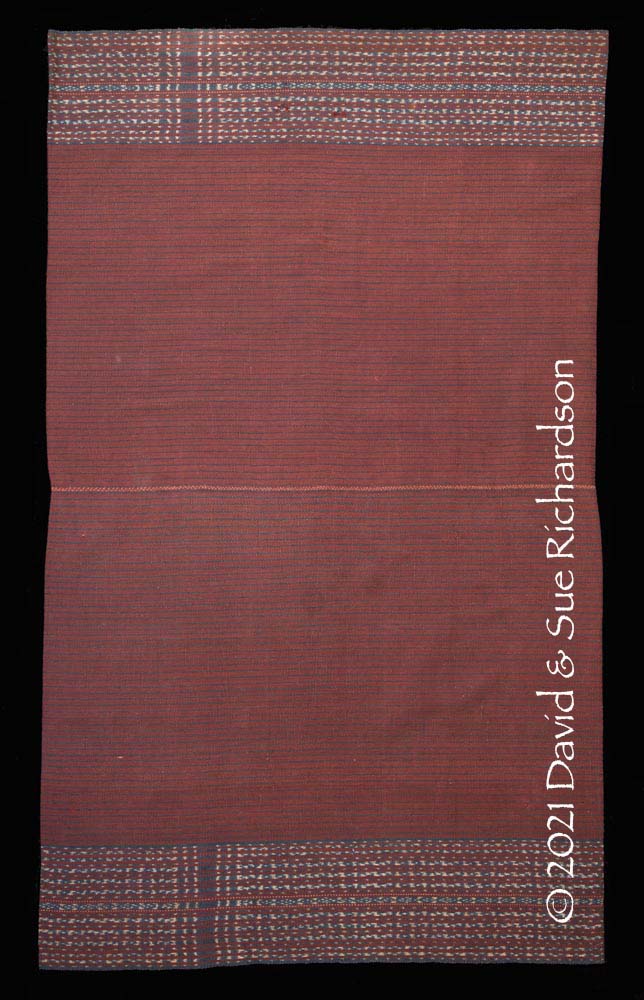

A kewatek Lamakera

Richardson Collection

The two identical panels are mostly covered with alternating stripes of plain morinda and indigo dyed warp ikat, the latter decorated with very simple dots and dashes. The weft is indigo. The bands are arranged so that the narrowest ikat bands are grouped in clusters.

Each panel contains ten ikat bands composed of three kenuma (ikatted bundles) and one outer band composed of five kenuma. Each panel also includes a few plain indigo stripes and a few rows of fine undyed plied warps. The alignment of the ikat stripes is excellent. The two panels have been joined using plied morinda hand-spun yarn. There is no rewot, the rolled side seam has been neatly sewn using a fine, plied, undyed hand-spun yarn.

Return to Top

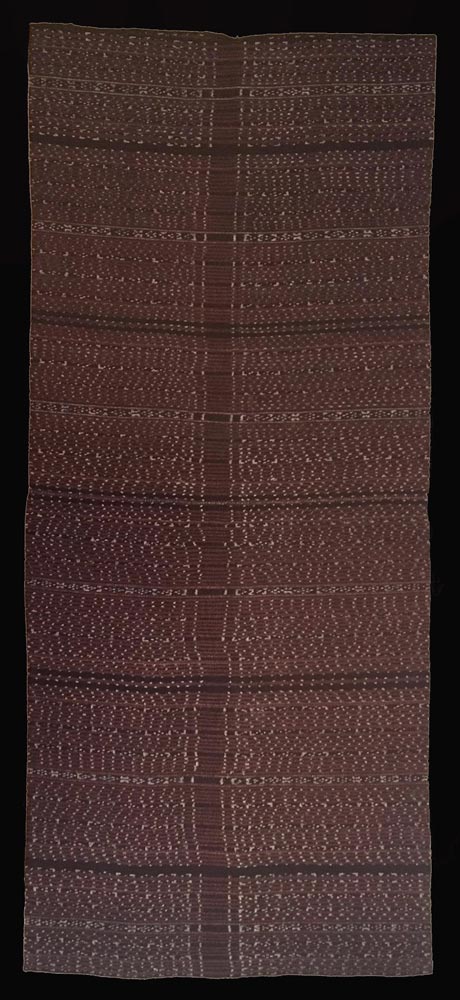

The Kewatek Kenuma

The kewatek kenuma is very similar to the kewatek Lamakera, and it is hard to define what separates them. According to our informants the only difference is that the main ikat bands are slightly wider and/or there are more of the wider bands.

The appellation kenuma refers to an individual bundle of six yarns, which is separately bound and dyed to become one of the elements that make up the pattern in the ikat band – the mowak (Barnes 1984, 92). A mowak is always composed of an uneven number of kenuma. A kewatek kenuma has indigo-dyed ikat bands composed of three (telo) or five (léma) kenuma, whereas a kewatek mowak has indigo-dyed bands composed of five (léma), seven (pito) or a larger number of odd kenuma. A kewatek kenuma is the lowest-status kewatek that can be used for bridewealth exchange.

Note that in the neighbouring regions of Lewolema and Demon Pagong the individual bundles are called kenumak.

The villagers of Baipito value a bridewealth sarong in terms of an elephant’s tusk or bala, the more valuable the sarong, the longer the tusk. A kewatek kenuma is valued equivalent to a legar tusk – a tusk with a length extending from the fingertip to the armpit.

Vatter collected a kewatek kenuma in Lewohala with each panel decorated with about fifteen indigo ikat bands composed of three kenuma and three indigo ikat bands composed of five kenuma. Ruth Barnes claimed that in terms of bridewealth status and value it ranked third after the kewatek Makassar and the kewatek méa (2004, 130). Our informants reported that it ranks third after the kewatek mowak and the kewatek méa.

A kewatek kenuma from Lewohala collected by Vatter.

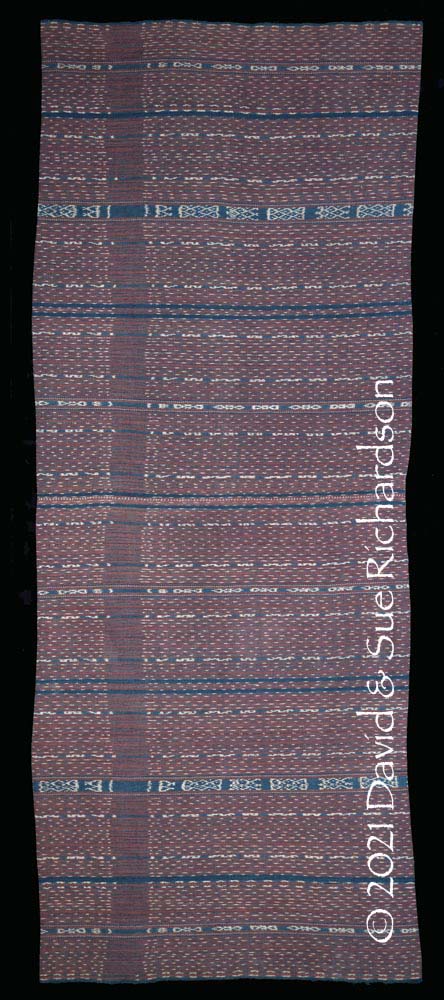

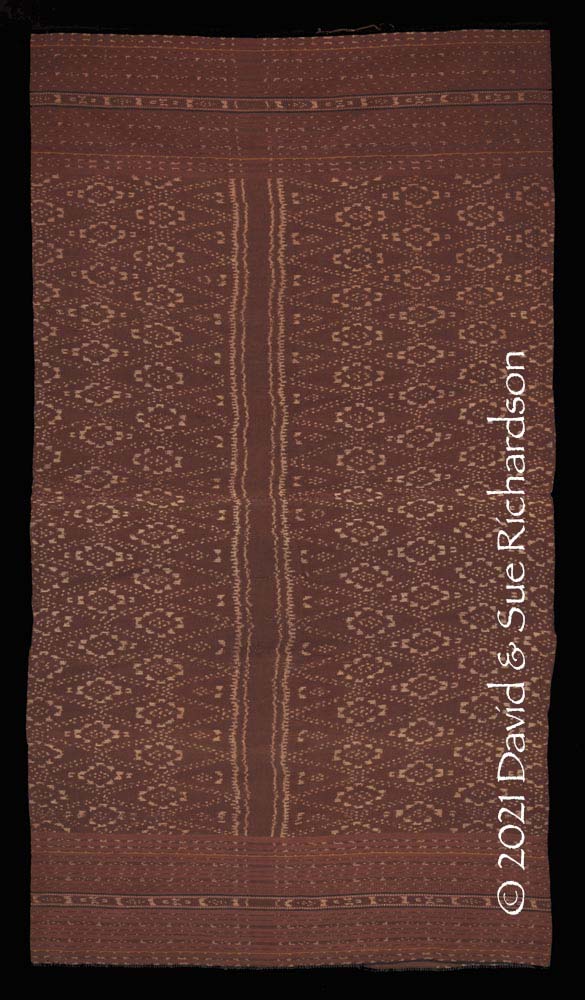

The following kewatek kenuma from our collection was woven from hand-spun cotton by the late Hadu Buan from kampong Lewohala. She was born in 1898 and belonged to suku Lebuan. She died around 1955.

An extraordinarily fine kewatek kenuma woven in Lewohala approximately 100 years ago

Richardson Collection

The two identical panels are mostly covered with alternating stripes of plain morinda and indigo-dyed warp ikat, the latter decorated with very simple dots, dashes and square brackets. The weft is indigo. Each panel contains eighteen indigo ikat bands composed of three kenuma and three indigo ikat bands composed of five kenuma. Each panel also includes a few plain indigo stripes and a few rows of fine two-ply coffee-coloured warps. The alignment of the ikat stripes is excellent.

Return to Top

The Kewatek Makassar

Ernst Vatter collected a sarong in Lewoloba in 1928 that he described as a kewatek Makassar. In 2013, weavers in Riang Kemie told us they too had an ago Makassar but did not describe it. Each panel of Vatter’s kewatek is decorated with eighteen ikat bands each composed of three kenuma and three ikat bands each composed of five kenumak – similar to the kewatek kenuma shown above. It was not new when acquired, being worn and partly frayed along the outer selvedges.

Ruth Barnes claimed that in terms of bridewealth status and value it was second only to the kewatek méa (2004, 130). This would place it on the same level of status as the kewatek mowak, described below.

The kewatek Makassar acquired by Vatter in Lewoloba

Return to Top

The Kewatek Mowak

A kewatek mowak (literally ‘ikat sarong’) has bands composed of more than five kenuma.

During the 1930s the Dutch ethnomusicologist Jaap Kunst visited the Baipito villages to record their local songs, including a Portuguese song sung by the Lewoloba teacher Joseph Kerfalo and his female choir (Kunst 1942, 4). While in Lewoloba he photographed the widow of the former kakang or village chief, wearing a kewatek mowak with a zigzag pattern identical to another shown below. She also had a dark checked cloth around her neck and appears to be wearing a mét belt around her waist.

The widow of the former chief of Lewoloba, photographed by Jaap Kunst

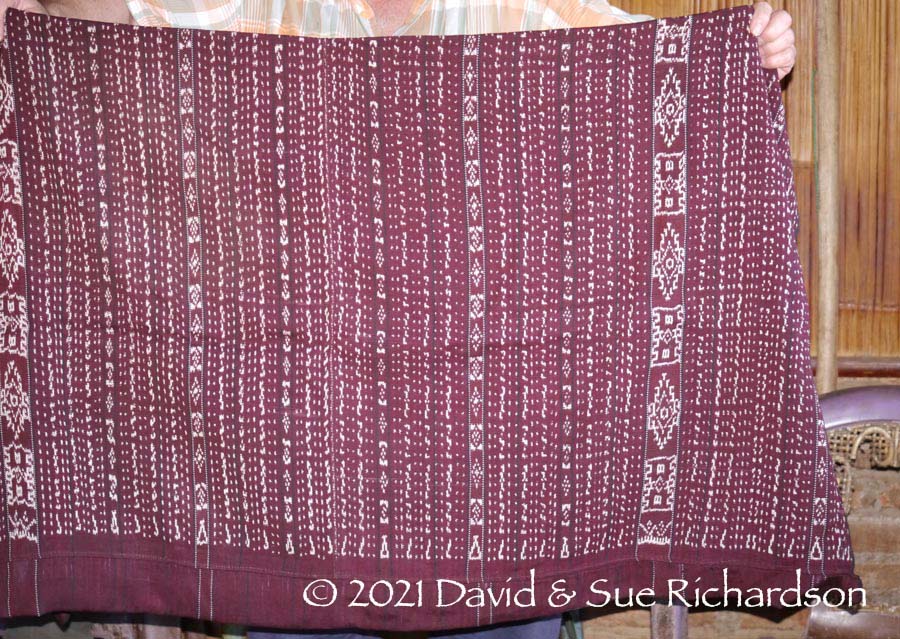

The panels in the following kewatek mowak from our collection are decorated with eight indigo bands composed of three kenuma, two indigo bands composed of five kenuma and one indigo band composed of thirteen kenuma.

It was woven by a young woman from Lewoloba who belonged to suku Lebuan. She married Lama Rongan, a man from Mawa, a village on the north coast of Ilé Api, Lembata Island, who belonged to suku Rongan. This kewatek was part of the counter-prestation for her marriage, given by suku Lebuan to suku Rongan.

A kewatek mowak woven in Lewoloba

Richardson Collection

Another kewatek mowak, this time from Lewohala, has panels decorated with two indigo bands composed of seven kenuma, each flanked by rows of white complementary alternating warp.

Another kewatek mowak woven in Lewohala

This seems to be a popular number of kenuma for the widest bands in this type of kewatek. We have examined four other sarongs from Lewohala with the same sized pair of bands in each panel, the patterns on each kewatek being different. The example below has two different bands in the same panel, one composed of five kenuma and the other composed of seven, both flanked by rows of complementary alternating warp.

A kewatek mowak from Lewohala with two types of main band

Return to Top

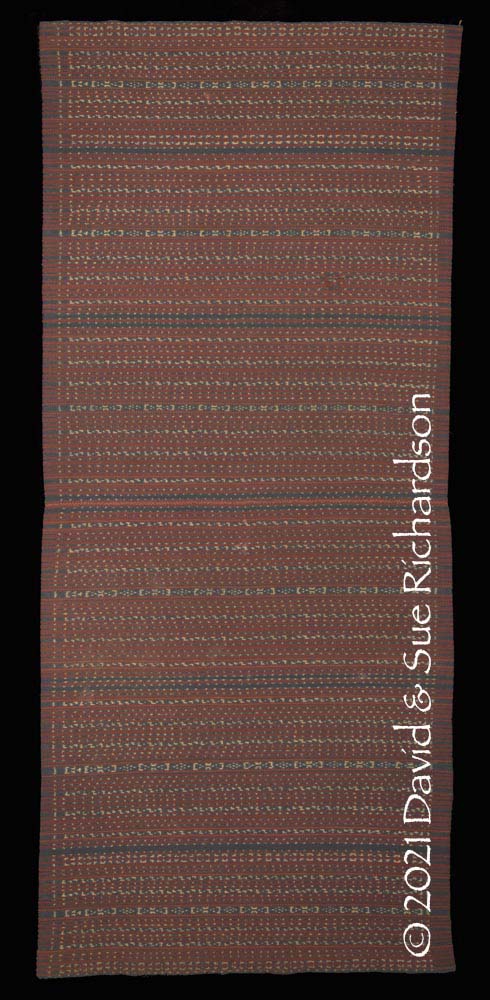

The Kewatek Méa

The kewatek méa or red sarong is decorated with bands of morinda-dyed ikat, one on each panel being much wider than those found on lower-status sarongs. Although the term méa or méan literally means red, for the Lamaholot it has cultural overtones signifying extraordinary and wealth (Barnes, R. H. 1974, 106).

Traditional Ilé Mandiri kewatek méa are quite conservative and understated compared to similar cloths made in Demon Pagong or Titihena. Ernst Vatter collected just one kewatek méa in Ilé Mandiri, but it was destroyed during World War II (Barnes 2004, 130).

Two different traditional kewatek méa woven in Baipito

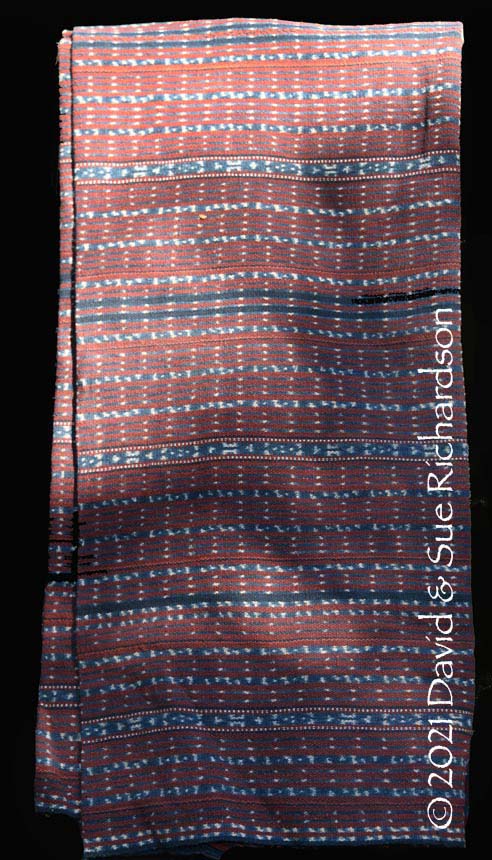

The following kewatek méa from the Richardson Colection was woven by Piré Piran from suku Piran, who was born in 1888 and died in Lewohala in 1979 at the age of 91. She started to weave at the age of 12, but only became completely competent in her early 20s. Her 63-year-old granddaughter who inherited this sarong believes that she wove it over 100 years ago when living in the village of Sirigokok, located higher up the slopes of Ilé Mandiri. The family left Sirigokok in 1916. It is precisely woven from finely hand-spun yarn, each kenuma composed of just four yarns. It has an intact uncut rewot and we were informed that it had been used once as part of a marriage counter-prestation.

An antique kewatek méa from Lewohala

Richardson Collection

The skirt is completely covered with narrow alternating bands of morinda ikat and plain morinda, separated by narrow indigo warp stripes. The majority of the ikat bands are composed of either single kenumas or triple kenumas. However the widest ikat bands are composed of either seven or nineteen kenumas, there being two of the first type on each panel and one of the second type. Each of these wider bands is highlighted by two outer dashed warp stripes woven in complementary warp using a pair of morinda warps and a pair of bright white two-ply commercial cotton warps. The latter are very shiny and give the impression of silk.

The design in the main ikat band, known as the kenire bele or big drawing, is called the snake pattern and is typical of Lewohala. It is composed of a single row of diamonds, each enclosing a small rectangle and cross.

Diamonds are the dominant motif found in the kenire bele of Ilé Mandiri kewatek méa and the hooked diamonds found in the neighbouring districts appear to be absent. The local weavers say the diamond motif has no name.

Return to Top

The Tenèpa Méa

Tenèpa were high-status Lamaholot sarongs that were woven on the east Flores mainland, as well as on Solor and Lembata. Some were two-panel and others were three-panel. In some regions they could be used for bridewealth but in others, such as Ilé Api on Lembata, they could not.

Paul Arndt translated tenepa in his Solorese grammar as ‘spread’ or ‘large mat’, a term related to the verb tepa, to stretch or to slap (Arndt 1937 cited by Barnes 1984, 220; Kroon 2016, 336). In Lamalera Lamaholot, the word tenèpa means extension (Robert Barnes 1996, 209). This might refer to the central panel extending a two-panel into a three-panel sarong, or perhaps to the much wider main ikat bands which occupy most of each skirt panel.

Morinda-dyed tenèpa méa appear to have been quite rare in the Ilé Mandiri region, although they are clearly still being made today as evidenced by an example worn by one of the group of women from Wailolong, illustrated above.

The following ceremonial two-panel tenèpa méa from our collection was woven from hand-spun cotton in Lewoloba. Unfortunately the identity of the weaver had been lost and could not be recalled by the previous 60-year-old owner from that village. It has an uncut rewot and could be used for bridewealth, being equivalent in value to one of the larger elephant tusks.

An old tenèpa méa from Lewoloba

Richardson Collection

This tenèpa tubeskirt has been woven with a double warp and a coarser morinda weft, apart from the three narrow plain black stripes located towards the outside of each panel, which appear to have been woven from pre-dyed two-ply commercial yarn. Each panel is woven with a continuous warp, the 10cm-wide section of unwoven warps (called the rewot on Ilé Mandiri) positioned at the rear.

The main body of the skirt is decorated with two diagonal lattices separated by tramlines, each cell of which is filled with simple stepped diamonds. Each panel has an outer section composed of a cluster of narrow warp stripes, the widest decorated with simple geometric motifs.

Bridewealth Sarongs

A kewatek that is exchanged for an elephant tusk must have an uncut rewot. At the time of the exchange the man’s clan will check the kewatek and look for the intact rewot and the nature of the ikat bands. Once a kewatek has been used as part of the counter-prestation, a woman in the receiving man’s clan may now cut the rewot and sew it up, showing that it now belongs to her. This means that it can no longer be used as a bridewealth sarong. Generally if a kewatek has an intact rewot it has been used, or is yet to be used, for bridewealth. If it is sewn, it has either already been used for bridewealth or never used for bridewealth at all.

In Ilé Mandiri only three types of kewatek can be used for the counter-prestation – in increasing status and value these are kenuma, mowak and méa. Valued in terms of an elephant’s tusk:

- a kenuma can be exchanged for a legar tusk with a length extending from the fingertip to the armpit,

- a mowak can be exchanged for a bedori tusk, with a length extending from the fingertip to the opposite shoulder, while

- a kewatek méa can be exchanged for a balarai tusk with a length extending from one fingertip to the other fingertip.

The best textiles were stored along with the dance jewellery in lidded baskets. Tobacco leaves were placed inside to protect the contents from moths.

Return to Top

Dance Costume

Ernst Vatter described the costume worn by twelve women and girls belonging to the same clan at a festival held in Wailolong to celebrate the repair of the village korke (1932, 94-95). They were performing the soka dance:

[Their] jewellery was wild and picturesque. Around their foreheads they wore a kenobo [headband], covered with a red cloth and embellished with nasa snails, on which a wreath of rooster feathers rose up, while long white goat hairs hung down to the shoulder framing the face like a wig. A piece of white cloth was wound around the richly patterned red festival sarong, tied as a belt or tied in the manner of an apron, while brass hoops clinked around the hands and ankles and small strips of fur covered with bells were fastened below the knees. In their right hand they held a white or brightly coloured cotton cloth, in the left a long stick with feathers at the top or a narrow dance shield carved with simple patterns, on which a stick was also placed.

Dancers in festival costumes at Wailolong. Vatter 1928

The dance lasted about a quarter of an hour before the beating of the drums and gongs ceased and a new group of dancers from another clan replaced them. The dances were strictly separated according to sex – men and women never danced together.

Among the next dance group was a little girl who was hardly more than eight or nine years old, dressed and adorned exactly the same as the grown-ups. She was the tono wudjo or tono wujo, the rice maiden, who represents the mythical young girl who was sacrificed in a field by her brother so that her body could metamorph into rice (Rappoport 2016, 173). The tono wujo participates in the various agricultural rituals associated with planting the annual rice crop.

Dance still plays an important role in Baipito festivals as well as ceremonies to welcome dignitaries such as senior government officials or new village teachers and priests.

Young dancers from Baipito wear similar festival costumes today

One of the largest formal dance performances was staged by 500 young women and girls from Lewohala and Riang Kemie at the opening ceremony of the East Flores Regency Lamaholot Arts and Culture Festival, held at Bantala in Lewolema district in September 2019.

Five hundred young Baipito women and girls performing a dance describing the farming life of their community in 2019. Image courtesy of vivatimur.com

Return to Top

Men's Costume

Baipito men’s costume is less varied than that made for women. In 1928 Ernst Vatter found that men were wearing three types of sarongs termed sěnái, the simplest being the indigo-dyed senai miten (in his transliteration sěnái mittän) and the finest and most valuable, the senai méa (sěnái mäan) (1932, 52). They covered the lower half of the body from the waist down, leaving the upper body free.

Vatter photographed a group of village elders in Lewoloba who were all dressed in senai miten, fastened in a bundle below the stomach. Two appear to have also had dark checked cloths wound around their waist, while one has a higher-status nowin draped over his shoulder.

Lewoloba elders photographed by Vatter in 1928

Apparently Father Paul Arndt photographed a warrior from Ilé Mandiri in the 1930s holding a short sword and a small labi shield (Arndt 1940, 251, plate 4).

The western Lamaholot term senai refers to a man’s two-panel hip wrapper. Jasper and Pirngadie suggested that senai was the Larantuka term for a man’s sarong and the Solorese term for a selendang (1912, 276). However the linguist Keraf suggested the term had the same meaning in Solor Lamaholot (Keraf 2016, 49). Keraf suggests it is related to the verb sai – to tear a cloth or fabric (2016, 268).

The same term is also used across eastern Indonesia to describe a single panel shawl or shoulder cloth – from the Endenese and the Lio of Ndona in Ende Regency, to Adonara and Ilé Api and Lamalera on Lembata (Al Khatab 2011; Barnes 1984, 109; Barnes 1989, 49).

However Western influences were already apparent. When Vatter arrived in Wailolong he was welcomed by the village chief (kakang) and the teacher Guru Roij, who wore linen jackets over their sarongs and had European haircuts, emphasising their social status (1932, 46).

The senai miten appears to have become obsolete many decades ago. Today a man’s everyday sarong is the nowin and the ceremonial sarong is the senai méa. This is strange because the former requires more ikatting than the latter.

Return to Top

The Senai Miten

In the past men wore an everyday indigo-dyed hip wrapper decorated with simple ikat stripes called a senai miten, which left the upper body uncovered.

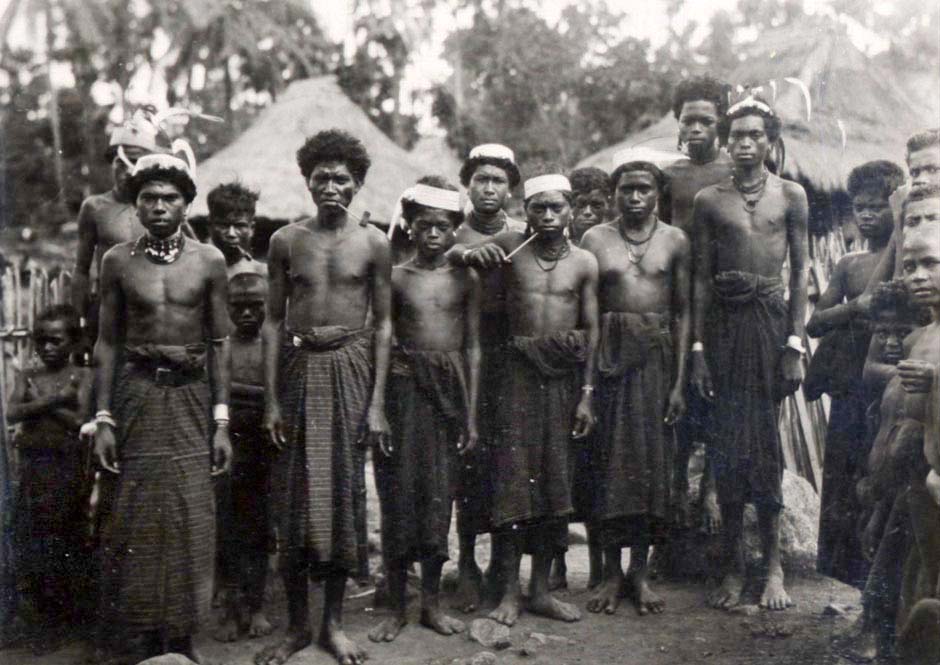

The earliest photographs of men from the Ilé Mandiri region were probably taken by the Dutch civil engineer Charles le Roux at some time between 1915 and 1918. The image below shows the two radically different communities who were living around Ilé Mandiri at that time, with two Larantuqueiros wearing European shirts surrounded by four mountain people, mostly youths. The latter are bare-chested and wearing simple textiles that appear coarse, three decorated with simple stripes, one chequered.

Two men from Larantuka with mountain people from the area around Ilé Mandiri, dated 1915. Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

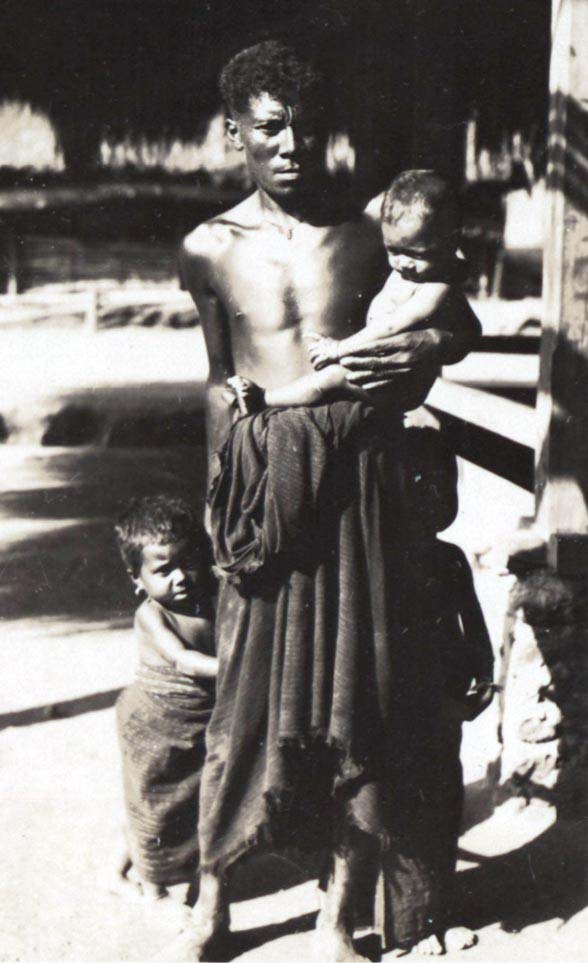

In 1928 Ernst Vatter took several photographs of men in Lewoloba wearing their everyday sarongs. One showing a man with his two small children gives a good illustration of how they were worn, with a large pouch at the front for holding the betel chew and other items.

A man in Leloba wearing a senai miten

It appears to be decorated with just single ikatted kenumas of indigo and white warps threads spaced closely together across each panel. It also shows the poor condition of some of these senai, with the lower hem shredded into threads. In another image of a group of men and youths in Lewoloba two of the men (far left) are clearly using leather belts with their senai, while the others wear them in the traditional manner.

A group of men in Lewoloba, some with bamboo kenobo headbands, necklaces and tobacco pipes

Kennedy observed that in 1950 the majority of cloth was heavy, dyed blue and black and ikatted, the decoration for men’s cloth being different than that for women (1953, 47). Later versions of senai miten were finished with a yellow warp thread along each outer selvedge.

We do not know exactly when, but just like the equivalent kewatek mitan, the senai mitan went out of fashion sometime ago, probably due to the increasing availability of lighter imported commercial textiles and clothing.

Return to Top

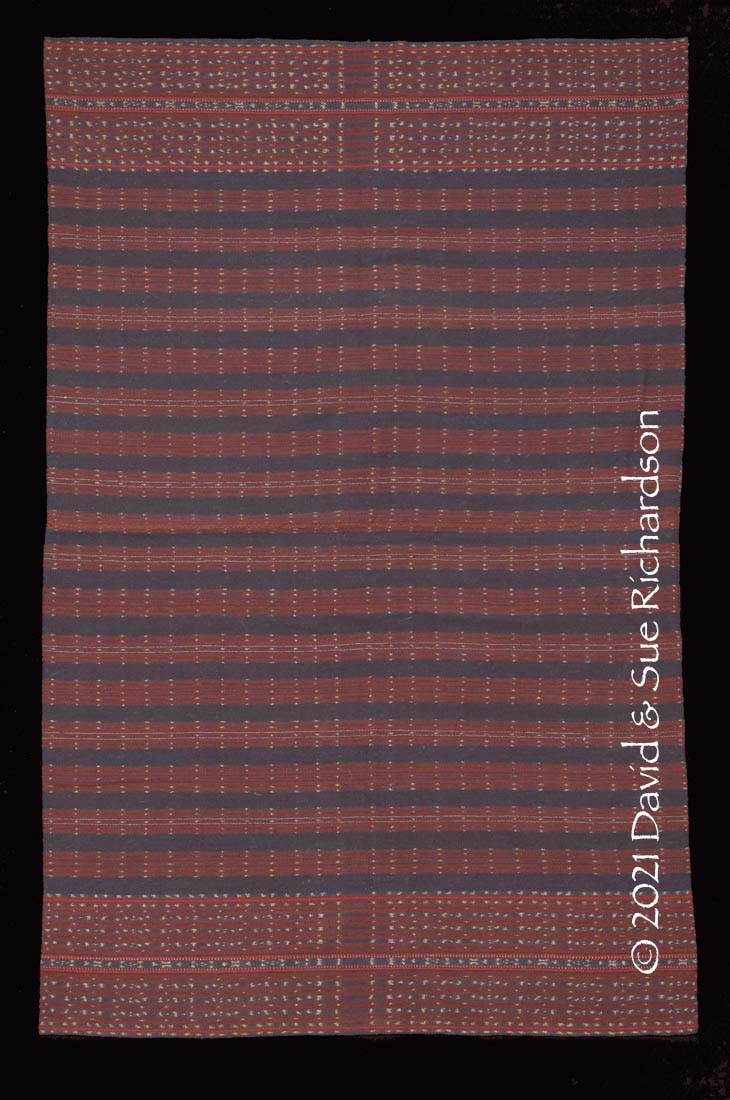

The Nowing

For ceremonial purposes today men wear two types of senai, the lowest-status version of which is the senai nowin. It is woven with a centre field with wide bands of plain red and indigo-ikatted stripes alternating with narrower bands of blue-black warp stripes, and with the hebak end panels filled with a cluster of closely-spaced narrow morinda stripes alternating with indigo-dyed kenuma stripes. Nowin are always woven using an indigo weft. Although woven with a continuous warp, men’s sarongs are always made with the rewot removed, the cut edges sewn together with a rolled side seam.

Having said that, we were however shown one nowin in Lewohala that had been made with an intact rewot, but were told that it could not be worn in that state.

Ernst Vatter collected an example in Lewohala that he described as a nowi. It has a centre field containing seventeen clusters of red and black stripes.

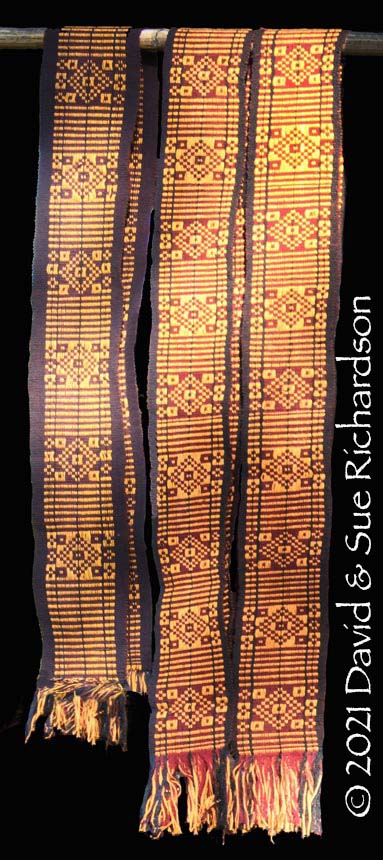

The senai nowin collected by Vatter in Lewohala in 1928

A second nowin example from the Richardson Collection was woven later in 1976 by Kibo Badin of suku Badin, the head clan in Lewohala. She was born in 1933 and was first taught to dye and weave at the age of 12 by her mother, Piré Piran from suku Piran, who also began learning to weave at the same age. Ibu Kibo married a farmer from suku Tukan and they had a daughter and two sons. She made the nowin for her second son, Nino Tukan. Kibo Badin sadly died in 2013 at the age of 80. The nowin was acquired from Kibo’s daughter, who was 63-years-old at that time.

A senai nowin woven in Lewohala in 1976

Richardson Collection

It was traditional for some mothers to gift such a sarong to her son at the time of his marriage, although it did not form part of the bridewealth. In other cases a prospective bride would make a nowin for her future husband and gift it to him at the time of their marriage.

A further pair of nowin woven in Lewohala

Nowin were worn with the seam at the front, almost hidden by a fold. The wearer makes a pocket at the top to hold cigarettes and other items and then twists and folds the top. In the past it was often worn with a mét belt, which was tied.

A similar nowin worn by Anton Hajon, the Regent (bupati) of Kecamatan East Flores

A male dance group from Baipito, dressed in synthetically dyed nowin, performing at Weri near Larantuka

Return to Top

The Senai Méa

The highest-status man’s sarong is the two-panel senai méan which has a red centre field covered with thin plain indigo and morinda stripes and hebak end panels with rows of indigo kenuma stripes. Senai méan were woven with a red weft on a continuous warp but, as with the nowin, the rewot is removed and the cut edges sewn together with a rolled side seam. Unlike the highest-status women’s sarong, the men’s senai méan is only decorated with bands and stripes dyed with indigo, never morinda.

Ernst Vatter referred to these cloths as sěnái mäan, noting that they were the finest and most valuable of the three men’s sarongs, valued at up to 30 guilders (about $750 in today’s money).

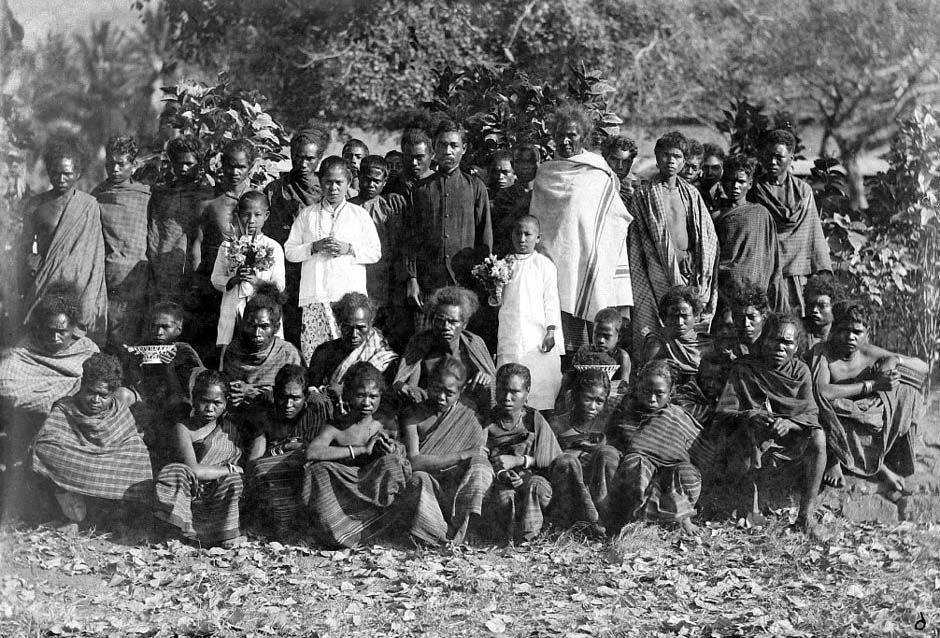

The earliest image we have of such sarongs is from a photograph that was most probably taken by Charles le Roux at some time between 1915 and 1918. It is a group portrait of a Roman Catholic bridal couple with two bridesmaids surrounded by local men and boys in a mountain village near the Ili Mandiri. Many of the villagers appear to be wearing senai méa, as would be appropriate for a wedding. The main body of their sarongs is decorated with narrow stripes apart from a wide lower band filled with a cluster of narrower stripes. Many others are wearing large checked cotton wrappers, probably imported from Makassar.

A Catholic wedding in a mountain village near Ilé Mandiri, dated about 1915

Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam

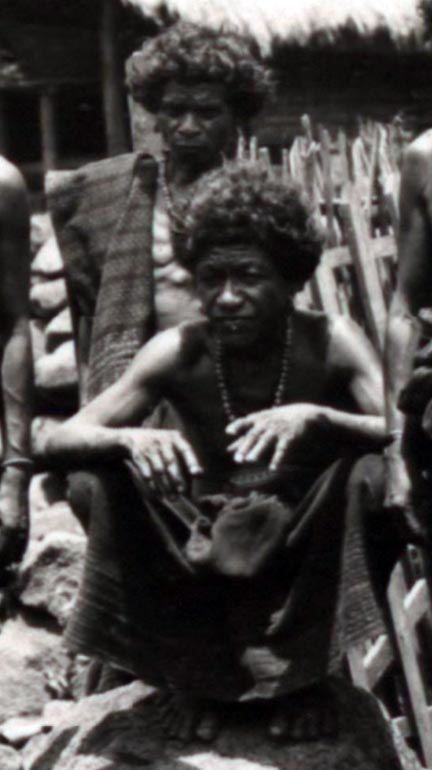

One of the unnamed men in Ernst Vatter’s photograph of the elders of Lewoloba shown earlier appears to be wearing a senai méa. The man standing behind has a nowin draped over his shoulder.

Squatting elder from Lewoloba wearing a senai méa

At least one of the three male dancers in Vatter’s backlit photograph taken in Lewoloba also appears to be wearing a senai méa.

Three male dancers at Lewoloba photographed by Vatter in 1928

In addition to red kenobo palm leaf headbands decorated with cockerel feathers, a few male dancers wore small straw hats, a feature common to many other districts in eastern Flores. Vatter found these most amusing:

Among the young men there were only two or three who expressed a greater sense of conspicuousness and preeminence than their fellow villagers: high on their thick woollen wig was a small, colourful straw hat with a high crown and a narrow rim, decorated with bobbing brass spirals which gave them an incredibly funny look.

The following example of a senai méa from the Richardson Collection was probably made before Vatter’s visit in 1928. It was woven by Piré Piran from suku Piran, the mother of Kibo Badin who made the nowin described above. As already mentioned, Ibu Piré was born in 1888 in the hillside kampong of Sirigokok up above Lewohala and was initially taught to spin and weave at the age of 12. She married a man from suku Badin and died at the age of 91 in 1979. The senai was acquired from another one of Piré’s granddaughters, who at the time was 68-years-old. The family believed that the senai méa was around 100 years old, having been carefully preserved for decades in a palm leaf basket containing tobacco leaf to protect the contents from insect attack.

A very old senai méa from Lewohala

Richardson Collection

Senai méa are still woven today using commercial yarns and dyes, but some families still have traditional versions that are donned for festivals and dance performances.

The parish priest of Riang Kemie surrounded by dancers from Lewoloba dressed in senai méan ready to welcome the Bishop of Larantuka in September 2018. Wikimedia Commons

Return to Top

The Mét

In the past men wore a narrow ceremonial belt called a mét, which was also occasionally worn by women. They were decorated with a geometric pattern and were woven on a narrow band loom using the supplementary warp weaving technique. This is a difficult technique because the tension of the supplementary warps must be kept the same as that of the ground warps.

A woman from Ilé Mandiri weaving a mét on a narrow back-tension loom

She uses lidi sticks to pre-programme the supplementary pattern

The mét had a ground woven from finely hand-spun warps and a thicker gauge weft. These were mostly dyed with morinda, but a few were dyed with indigo. A few black and sometimes white warps often delineated each selvedge. Heavier gauge undyed cotton was used for the supplementary warps, and sometimes a few supplementary black warps were added to embellish the banding. The supplementary warp pattern was always geometric. The unwoven warps at each end were twisted together to make long fringes.

Ernst Vatter collected two mét in Lewoloba, a mét mitan with an indigo dyed ground and a mét méa, with a morinda dyed ground.

The technique is still used by a few weavers today, but the quality of the belts is far below that produced in the past.

Modern synthetically dyed mét from Lewohala

Return to Top

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many weavers in the villages of Baipito – Lewoloba, Lewohala, Riang Kemie and Mudakaputu – who have welcomed us over the years and generously answered our many questions.

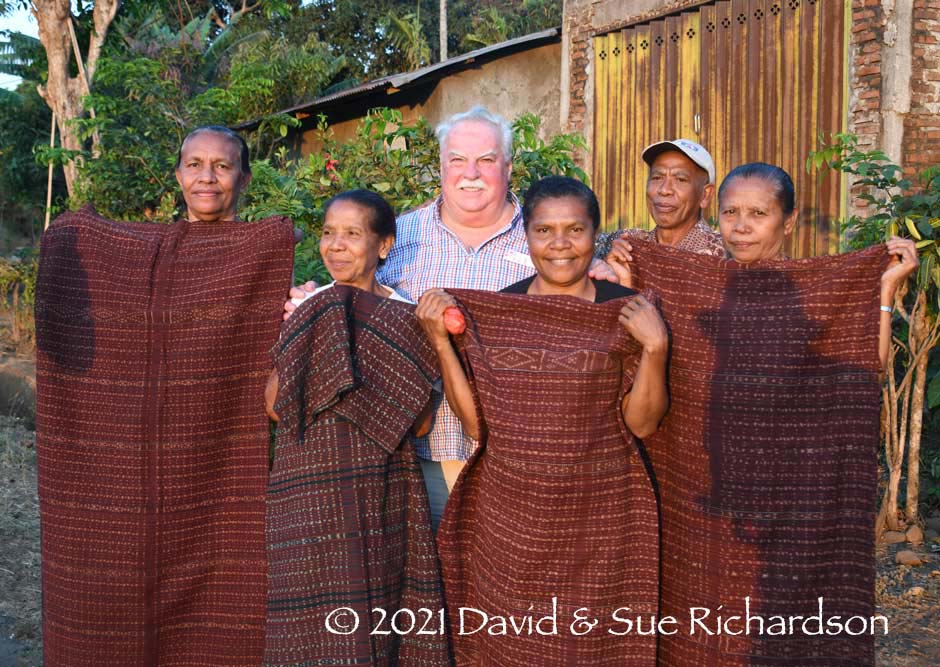

David with four of the ladies from Lewohala displaying some of their family heirlooms

Return to Top

Bibliography

Al Khatab, Umar Ibnu, 2011. Makna Motif Tenun Ikat Dalam Masyarakat Pesisir dan Masyarakat Pedalaman, Patanjala: Jurnal Penelitian Sejarah dan Budaya, pp. 64-73, Bandung.

Arndt, Paul, 1937. Grammatik der Solor-Sprache, Arnoldus Drukkerij, Ende, Flores.

Barnes, R. H., 1974. Kedang: a Study of the Collective Thought of

An Eastern Indonesian People, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1977. Alliance and Categories in Wailolong, East Flores, Sociologus, vol. 27, pp. 133-157, Duncker and Humblot, Berlin.

Barnes, R. H., 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 2009. A temple, a mission, and a war: Jesuit missionaries and local culture in East Flores in the nineteenth century, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 165, no. 1, pp. 32-61.

Barnes, Ruth, 1984, The Ikat textiles of Lamalera, Lembata within the Context of Eastern Indonesian Fabric Traditions, D.Phil. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1991. "Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 2, pp. 95–112.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. East Flores Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden: textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, Hamilton, Roy W., (ed.), pp. 171–191, Fowler Museum, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 2004. Ostindonesien im 20. Jahrhundert: Auf den Spuren der Sammlung Ernst Vatter, Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt.

Clarence-Smith, William Gervase, 2011. The expansion of cotton textile production in the western Indian Ocean, c1500-c1850, Reinterpreting Indian Ocean worlds: essays in honour of Kirti N. Chaudhuri, pp. 84-106, Cambridge Scholars Publishing Ltd., Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Dietrich, Stefan, 1995. Tjeritera Patigolo Arkian: Struktur und Variation in der Gründungsmythe des Fürstenhauses von Larantuka (Ostindonesien), Tribus, vol. 44, pp. 112–148.

Dietrich, Stephan, 1998. "We Don't Sell Our Daughters": A Report on Money and Marriage Exchange in the Township of Larantuka (Flores, E. Indonesia), Kinship, Networks and Exchange, pp. 234–250, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Graham, Penelope, 1987. East Flores Revisited: a Note on Asymmetric Alliance in Leloba and Wailolong, Indonesia, Sociologus, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 40-59.

Graham, Penelope, 1994. The ‘Severed Shroud’: Local and Imported Textiles in the Mortuary Rites of an Indonesian People, Contact, Crossover and Continuity, pp. 159–166, Textile Society of America, Los Angeles.

Graham, Penelope, 1994. Vouchsafing Fecundity in Eastern Flores: Textiles and Exchange in the Rites of Life, Gift of the Cotton Maiden: textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, Hamilton, Roy W., (ed.), pp. 228–245, Los Angeles.

Hamilton, Roy W., 2010. Textiles and Identity in Eastern Indonesia, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles, pp. 301-349, Delmonico Books – Prestel, Munich.

Kennedy, Raymond, 1955. Field Notes on Indonesia: Flores, 1949-1950, Human Relations Area Files, Behaviour Science Monographs, New Haven.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. Morfologi Dialek Lamalera, Doctoral Thesis, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java.

Kroon, Yosep Bisara, 2016. A Grammar of Solor – Lamaholot: A Language of Flores, Eastern Indonesia, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide.

Kunst, Jaap, 1942. Music in Flores, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Rappoport, Dana, 2016. Why do they (still) sing stories? Singing narratives in Tanjung Bunga (eastern Flores, Lamaholot, Indonesia), Wacana, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 163-190.,

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Vatter, Ernst, and Niggemeyer, Hermann, 1961. Ata Kiwan ("Menschen der Berge") im Solor-Alor-Archipel (Ostindonesien) - 1. Männerauenarbeiten, IWF, Göttingen.

Vatter, Ernst, and Niggemeyer, Hermann, 1961. Ata Kiwan ("Menschen der Berge") im Solor-Alor-Archipel (Ostindonesien) - 2. Frauenarbeiten, Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, Göttingen.

Vatter, Ernst, and Niggemeyer, Hermann, 1961. Ata Kiwan ("Menschen der Berge") im Solor-Alor-Archipel (Ostindonesien) - 3. Spiel und Tanz, Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, Göttingen.

Verheijen, Jilis A. J., 1990. Dictionary of Plant Names of the Lesser Sunda Islands, Australian National University, Canberra.

Weking, Christina T., 2018. Derivasi Bahasa Lamaholot Dialek Baipito, Metalingua, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 135-151.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 15 February 2021.