Asian Textile Studies

Contents

The Ngada Region

Ngada History

Ethnography

Ngada Textiles

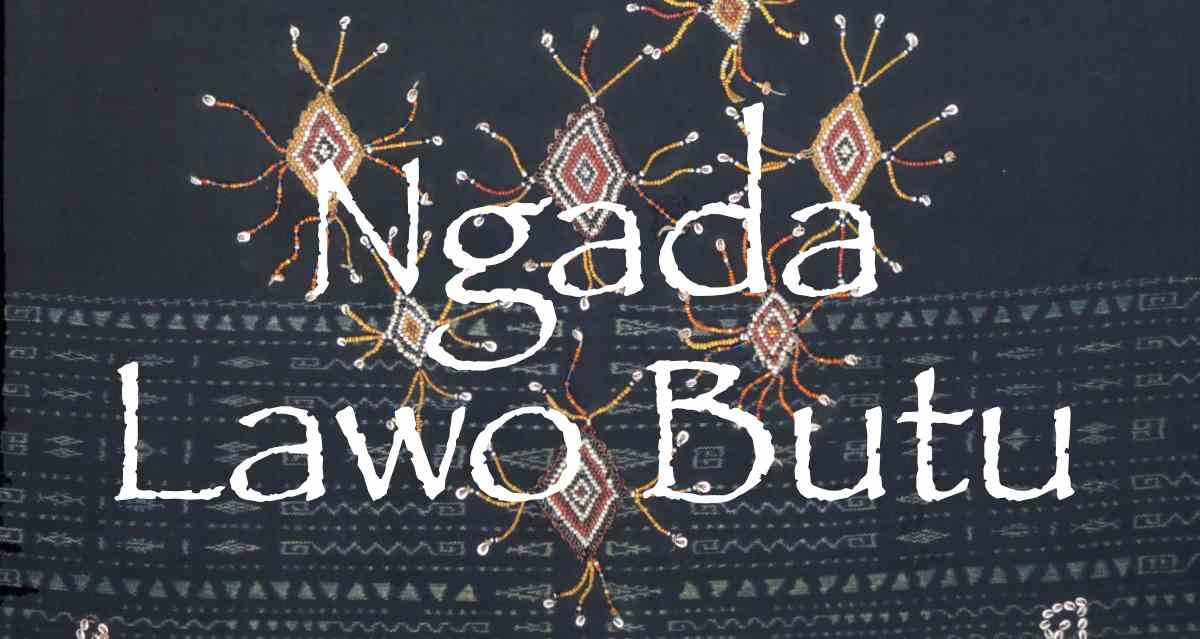

The Ngada Lawo Butu

Lawo Butu Types and Motifs

Lawo Butu and Father Piet Petu SVD

Examples from Museums and Private Collections

Modern Lawo Butu

Restoring Old Lawo Butu

Other Beaded Sarongs from Flores

Bibliography

The Ngada Region

The region of Ngada (pronounced ‘Nada’) is located close to the middle of Flores Island, stretching from north coast to south coast.

The region of Ngada highlighted on a map of Flores

Ngada has low-lying coastal plains and hills in the north; rugged and heavily forested valleys in the interior; and extensive volcanic mountain ranges in the south. This central part of the island is much wetter than eastern Flores and its many mountain streams drain into the central Soa Basin catchment area, which empties north through the Sissa River into the Flores Sea. The old capital of Bajawa, the highest town on Flores, remains the administrative centre of the new slimmed-down Ngada Regency. Established here by the Dutch because of its cool climate, it nestles in a mountain bowl overlooked by volcanic peaks to the north and west. To the south of Bajawa lies the vast, isolated pyramidal cone of dormant Gunung Inierie (2245m), sloping down to the Savu Sea – the sixth highest volcano in the Lesser Sunda Islands. The population is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, although communities of Muslim Bugis and Bajau live along the north coast and in the northern town of Riung.

Above: The imposing cone of Gunung Inierie

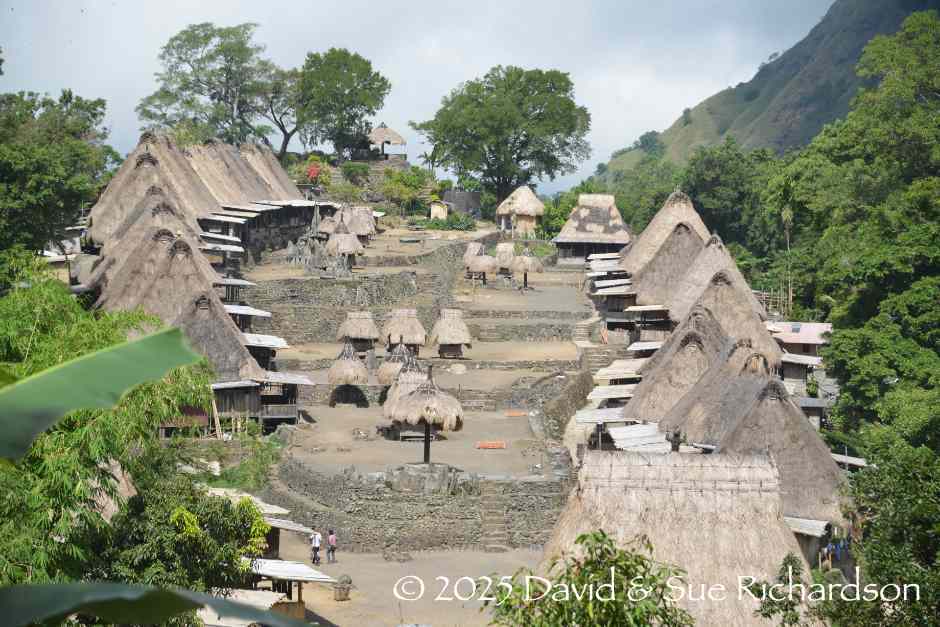

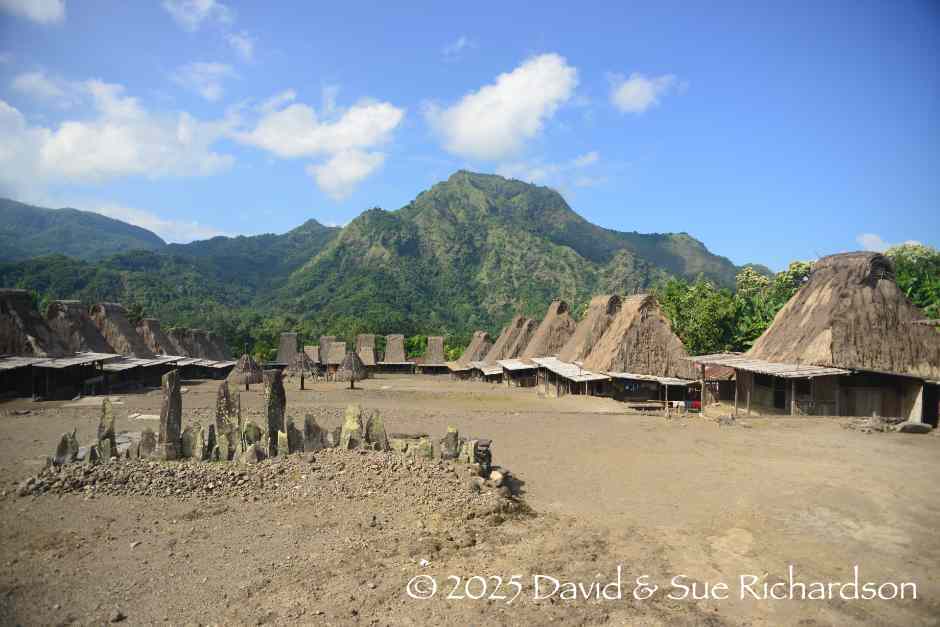

Below: The Ngada village of Bena

Ngada History

The Ngada region offered little to the Portuguese or the Dutch and remained a fragmented backwater until the early twentieth century. Portuguese involvement during the sixteenth century was restricted to the export of local Rokka cinnamon through the port of Ende, and the creation of a mission with five chapels on the southeast coast of the Nagekeo region – at Kewa, Lena, Mari, Lambo and Tonggo. In the seventeenth century the small northern coastal port of Riung fell under the authority of the Sultan of Goa in South Sulawesi and was obliged to pay tribute. Following a marriage alliance between Bima and Goa in 1727 it came under the authority of the Sultanate of Bima.

Although the Dutch acquired Flores from the Portuguese in 1859, their initial interest was confined to Ende, Sikka and Larantuka. In 1856 the Ngada coast was visited by the merchant J. P. Freijss who found that because of the export of cinnamon and wax, the natives were able to enjoy a higher standard of living and acquire articles of luxury. He also reported that gold and tin were available in the region. This eventually led to the arrival of a Dutch geological expedition in 1889 to explore Gunung Inierie (then known as Mount Rokka) in the hope of discovering large deposits of tin. Despite heavy military protection they were attacked by the local Ngada tribesmen and forced to return to Kupang. The Dutch quickly responded with a punitive mission the following year, which was also attacked after failing to find tin.

Following further uprisings across Flores, the Dutch administration in Batavia responded in 1907 by launching a brutal 'war of pacification'. After suppressing Ende, Captain Hans Christoffel landed with a company of military police at Aimere Bay in August and by late September had gained control of the whole Ngada region. In 1909 the Dutch created the separate sub-division (onderafdeling) of Ngada. This was split into four self-governing districts, with the capital of Bajawa and the cultural regions of Riung, Nagé, and Kéo each placed under the authority of a Dutch-appointed Raja. A road was constructed from Aimere to Bajawa, which, with its mountain setting and temperate climate, soon became the main colonial administrative centre. There was some subsequent native resistance, especially from the Kéo who staged a rebellion in 1912.

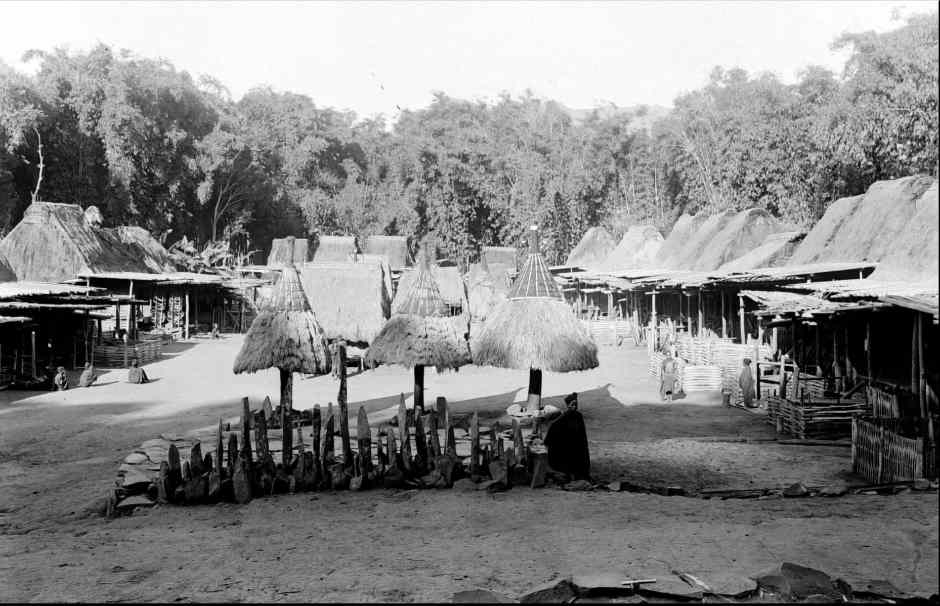

The village of Bolonga photographed by Charles Le Roux around 1917

The first school was opened in Bajawa in 1911, founded by a teacher from Lela near Sikka Natar. Between 1920 and 1930 an influx of priests from the Societas Verbi Divini (SVD) established parishes across the onderafdeling in an attempt to convert the population to Catholicism. However, Ngada remained the most isolated and traditional region on Flores. Although a church was inaugurated in Bajawa in 1930, a teacher from the nearby seminary still described the Raja of Bajawa as a full-blooded pagan with a cortège of women. By 1942 the number of schools across the whole of Ngada had reached fifty.

The spectacular village of Gurusina, which was destroyed by fire in 2018

Return to Top

Ethnography

Until the late nineteenth century the Dutch referred to all of the mountain people living in the region between Manggarai and Ende as the Rokka. The colonial civil engineer Charles C. F. M. Le Roux summed up Dutch attitudes to these and the other peoples of Flores:

Our close acquaintance with the Florenese - who are a particularly primitive people – only dates from the year 1907. Previous to that year the tribes lived far away in their almost inaccessible, desolate and grim mountains.

The Ngada (or sometimes Ngadha) occupy the southern highlands of Ngada Regency. They were formerly animist, but today regard themselves as Roman Catholics. The people of the inland Soa valley have yet to be studied by anthropologists, but seem to have a language and customs somewhat similar to the Nagé of neighbouring Nagekeo Regency. Finally the Riung occupy the northern lowlands, especially the districts of Riung and Wangka. They are closely linked to the neighbouring Rembong of Manggarai and trace their origins to Sulawesi, Sumbawa and Maluku. Now mainly Catholic, they are of mixed ethnicity with the endemic Bajawanese farming the inland regions, while the Islamic Bugis and Bajau live in fishing communities along the coast.

The Ngada depend primarily on swidden agriculture supplemented by hunting and gathering and, along the coast, fishing. They also keep water buffalo, pigs, poultry and dogs. Despite their conversion to Catholicism in the 1920s, they have preserved many of their traditional beliefs and practices, such as the worship of ancestors, building rectangular and boat-shaped ceremonial villages, and creating megalithic structures.

Every Ngada person is born into a social kin group called a sa’o (house), to which both their parents belong. Depending on the specific sa'o, affiliation follows either male or female lines back to a common ancestor or ancestress. Groups of from six to ten sa'o are clustered into a woé, which Olaf Smedal defines as a coalition of houses rather than a clan because its members do not share one common line of descent. Neither woé nor sa'o are exogamous – while 85-90% of marriages take place between couples from separate sa'o, 10-15% do not.

If the couple do not already belong to the same sa'o, marriage can take two forms depending on the size of the bridewealth – either the husband joins the wife’s sa'o, or the wife joins the husband’s sa'o. When the bridewealth is modest the woman remains in her sa'o and is joined by her husband. When the bridewealth is substantial the woman moves into the sa'o of her husband. These two patterns tend to be regional because bridewealth payments tend to be high in some eastern villages (such as Wéré) and are more modest around Gunung Inierie.

At the same time Ngada society is divided into a hierarchy of three classes – nobles (ga’é méze), commoners (ga’é kisa), and former slaves (zo'o or ho'o), between which marriage is strictly regulated. In particular, women must not marry down.

The negotiation of marriage arrangements is the responsibility of the couple's respective sa'o. Marriage exchange in Ngada society differs from that found among the other ethnic groups on Flores in that it is unbalanced – bridewealth prestations are not reciprocated by specific goods, such as valuable textiles. The wife-takers are obliged to provide bridewealth in the form of livestock (water buffalo and horses – ranging from a handful around Bena and Gurusina, up to twenty further to the east). The wife-givers make a counter-prestation of pigs, which are immediately slaughtered for joint large-scale feasting. Bridewealth is paid in instalments over many years and in many cases is never completed. The Ngada believe that the greater the unpaid part of the bridewealth, the stronger the bond between the sa’o.

A traditional village or nua consists of a collection of physical houses, which are owned by different woé and are usually set up along two parallel lines. Each woé owns a pair of ancestral shrines, a male ngadhu (a two-pronged sacrificial pole topped with a parasol-like thatched roof) and a female bhaga (a ceremonial hut built like a miniature house), both situated in the centre of the nua. To protect the village and its inhabitants the ngadhu must be regularly fed with 'noble' blood from sacrificed buffalo. Chickens and pigs are sacrificed in front of the bhaga. The centre of the nua also contains a number of megalithic structures called lenggi, which are used as a court where the leaders of the different sa’o can settle their legal disputes.

A female bhaga (left) and a sacrificial male ngadhu (right) in Bena

Return to Top

Ngada Textiles

The earliest colonial reports depict the Rokka as cannibals, but in 1858 J. P. Freijss found them to be strong and industrious growing cotton and indigo. The earliest record of Ngada costume comes from photos taken between 1915 and 1918 by the Dutch civil engineer Charles Le Roux. They show women wearing dark ankle-length sarongs fastened at the shoulders, conservatively decorated with narrow rows of faint motifs. The men are shown wearing short dark hip wrappers, large dark shoulder cloths (some folded and crossed over the upper breast and shoulders), and plain head wrappers. Dancers at a feast wear plumed headdresses, a narrow sash crossed over the breasts and heavy cylindrical armlets. Another photo shows women with drop spindles, spinning wheels and a back-tension loom set up with a continuous warp.

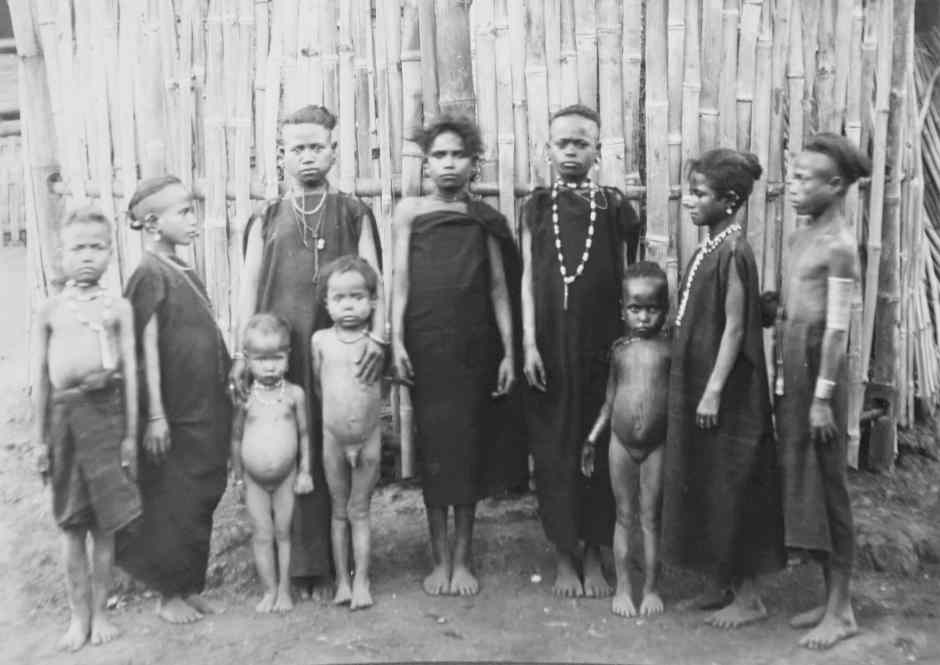

Above: Ngada weavers photographed by Charles Le Roux around 1917. Below: A group of Ngada women and children photographed by Charles Le Roux around 1917

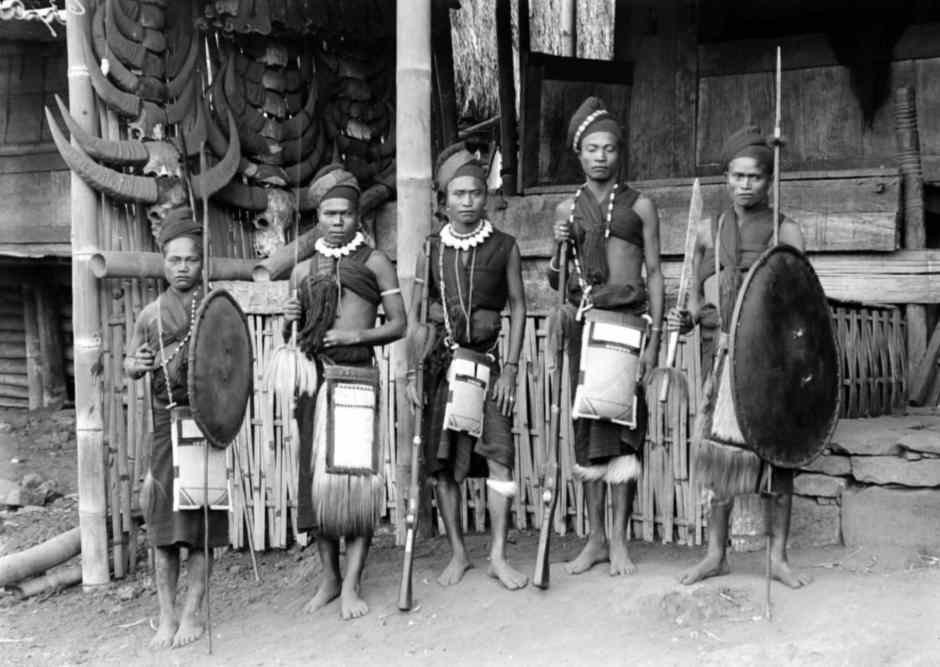

Ngada warriors photographed by Charles Le Roux around 1917

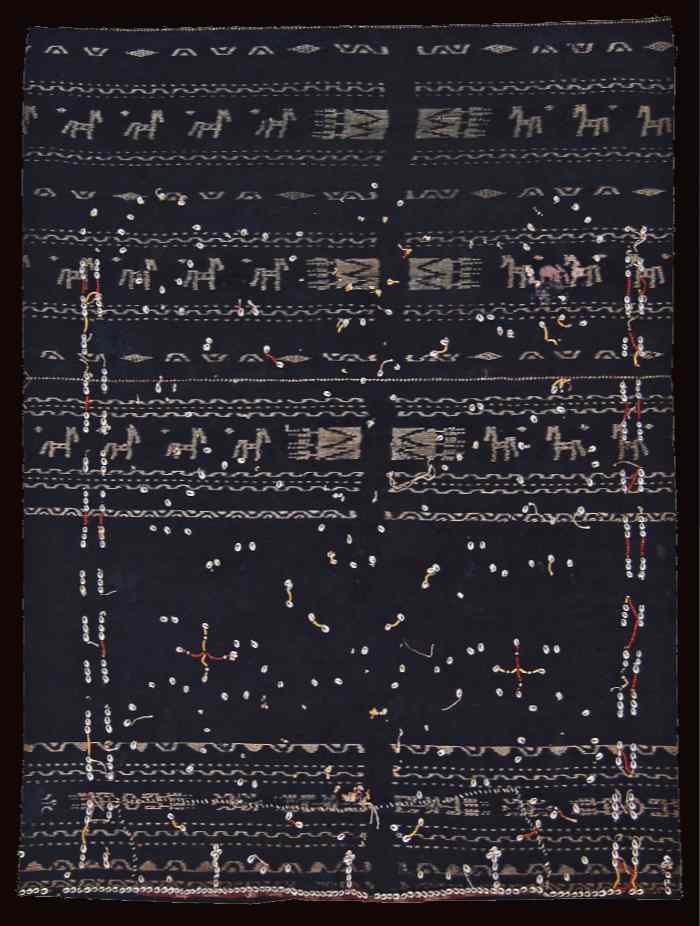

Jaap Kunst and Pater Heerkens recorded almost identical costumes when they visited a festival in Wéré village in 1930 (Kunst 1942,84). The women wore black cotton dresses with orange-coloured sashes crossed over their chest and back. Some wore brass spirals enclosing the whole of their upper- and forearms. The men wore a sarong around their hips and legs, an upper body cloth rolled up lengthwise wound under the arms and over the shoulders, and a headband. They had chains of white cowrie shells around their necks and large flat rectangular betel nut baskets (lega) decorated with hairy goat hide hanging by their sides.

The Ngada traditionally specialized in warp ikat, dyed almost black as a result of multiple immersions in indigo. Red was uncommon but a few textiles included small amounts of sappan wood dye, especially along the selvages. Because indigo does not grow at higher altitudes, the most important Ngada weaving villages are located on the lower eastern slopes of Gunung Inierie, firstly in the sub-district of Jere Bu'u (specifically the villages of Luba and Bena, but not Gurusina or Tolelola), and secondly around the more modern village of Langar which is situated further north. The third region is located to the west of the highest peak on the rim of the mountain bowl that surrounds Bajawa, specifically the isolated hamlets of Lopijo and Teni. In the past weaving also took place in the eastern villages of Mangulewa, Mataloko and Wogo. Because of its high location, weavers in Mangulewa obtained their cotton and indigo from fields further down the mountain, although some used black mud instead of indigo.

A Ngada weaver photographed by Gerret Pieter Rouffaer in 1910

Women's sarongs are known as lawo and are fastened at the shoulder with threads known as kondo. They are all indigo-dyed and are classified according to status:

- lawo wa'i manu, a two-panel'chicken-foot' sarong with a small three-pronged motif, once worn by young girls.

- lawo wua wera, a three-panel sarong, worn by girls of marriageable age. Equivalent in value to one pig.

- lawo jara, a three-panel sarong with bands of horse motifs, restricted to a woman who, together with her husband, has commissioned a community feast. Worth one horse.

- lawo sora, an aristocratic three-panel sarong with ikat bands containing motifs, such as a spear, butterfly, mantis, fish and crab. Worth one buffalo.

- lawo kéto, a three-panel sarong of the highest status with horse motifs arranged in a broad field covering both the end panels and the centre panel. Worth one buffalo with horns the length of a man's arm.

- lawo butu, a sacred three-panel beaded sarong for a clan elder of the highest rank. Women wove the cloth but supposedly men did the beading. After the clan leader's death, the sarong was known by his name and stored in the clan house. For this reason they are sometimes called lawo ngaza, 'named skirts'.

The generic term lawo gaja seems to refer to a cloth belonging to someone of the highest status, whatever its motifs.

Once they are circumcised and initiated, young men wear a ghi'u sarong and an isi wio shoulder cloth, both dyed with indigo and decorated with simple warp ikat motifs. Initially signifying marriageability, these two garments continue to be worn as daily dress well into married life. They were traditionally worn with a sappan-dyed rectangular headdress (boku), and an indigo belt (keru), decorated with supplementary warp.

In the past, when a man reached a state of maturity and was in a position to host a traditional feast involving the slaughter of a buffalo, he was entitled to adopt a new set of garments decorated with narrow bands of horse (jara) motifs – a sapu jara sarong and a lu'é jara shoulder cloth that could also be folded and worn across the chest. These were accompanied by a matching ikat belt decorated with similar horse motifs.

Return to Top

The Ngada Lawo Butu

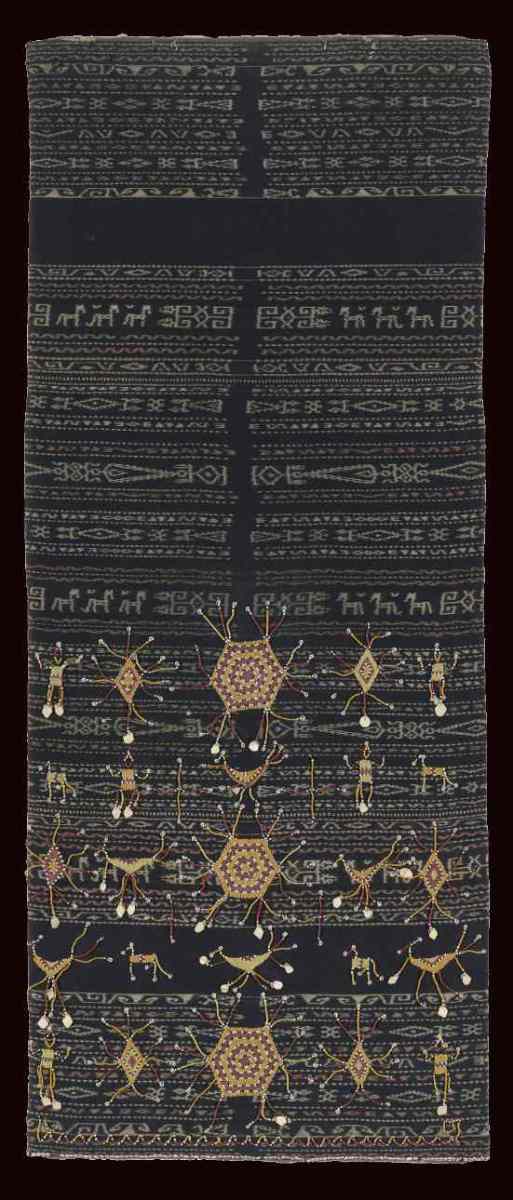

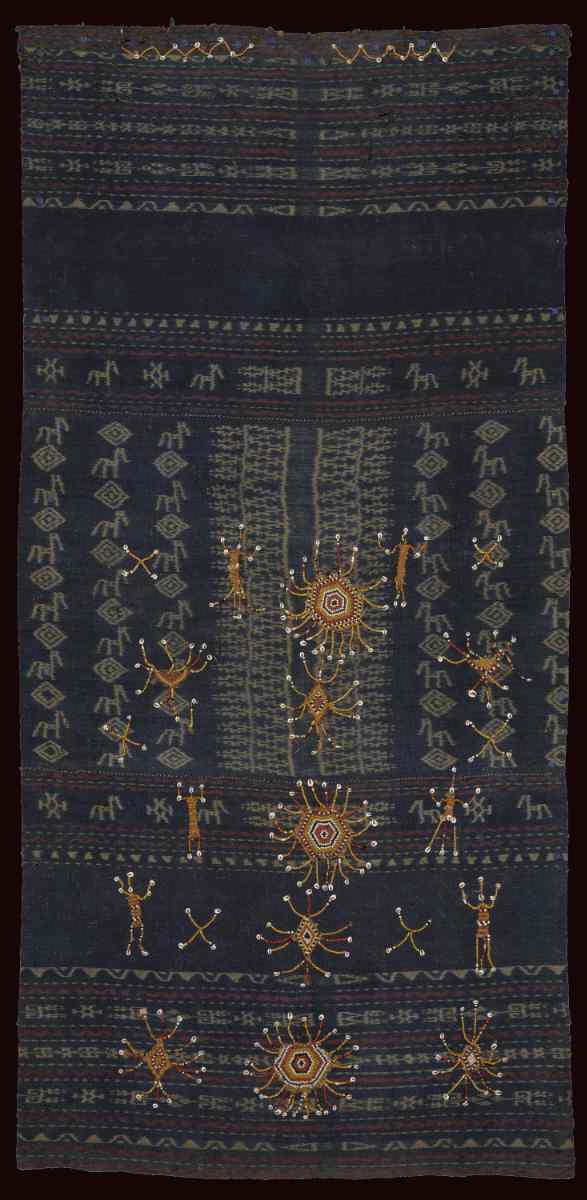

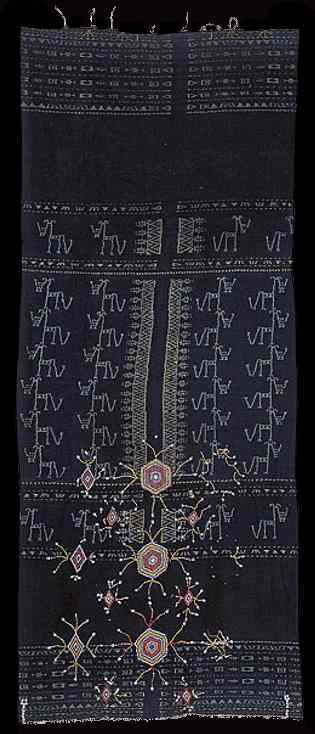

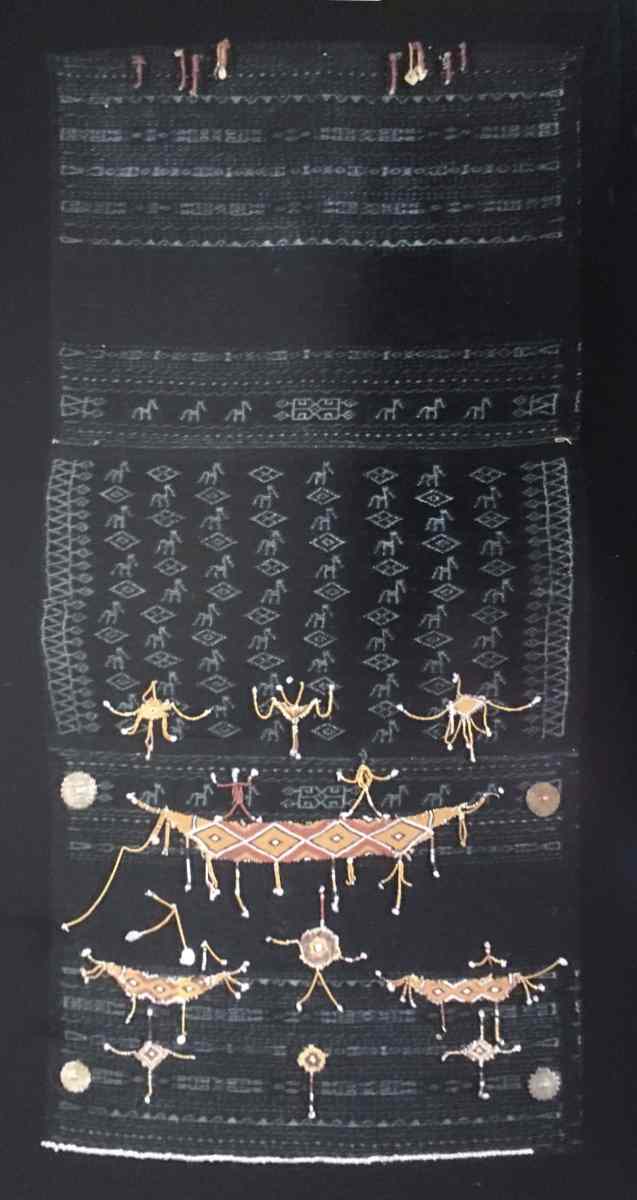

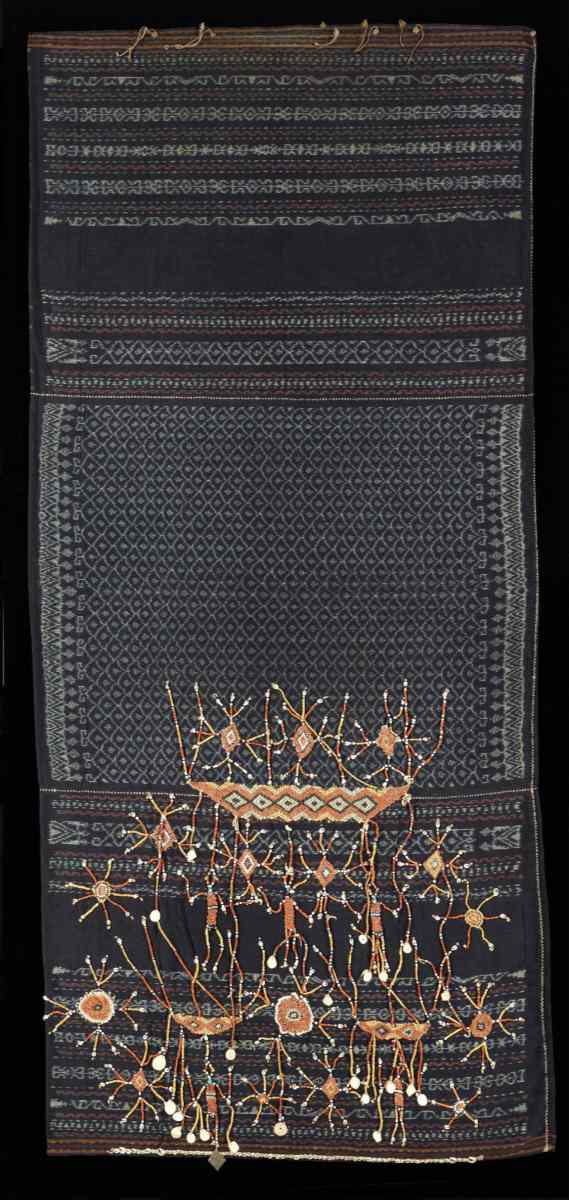

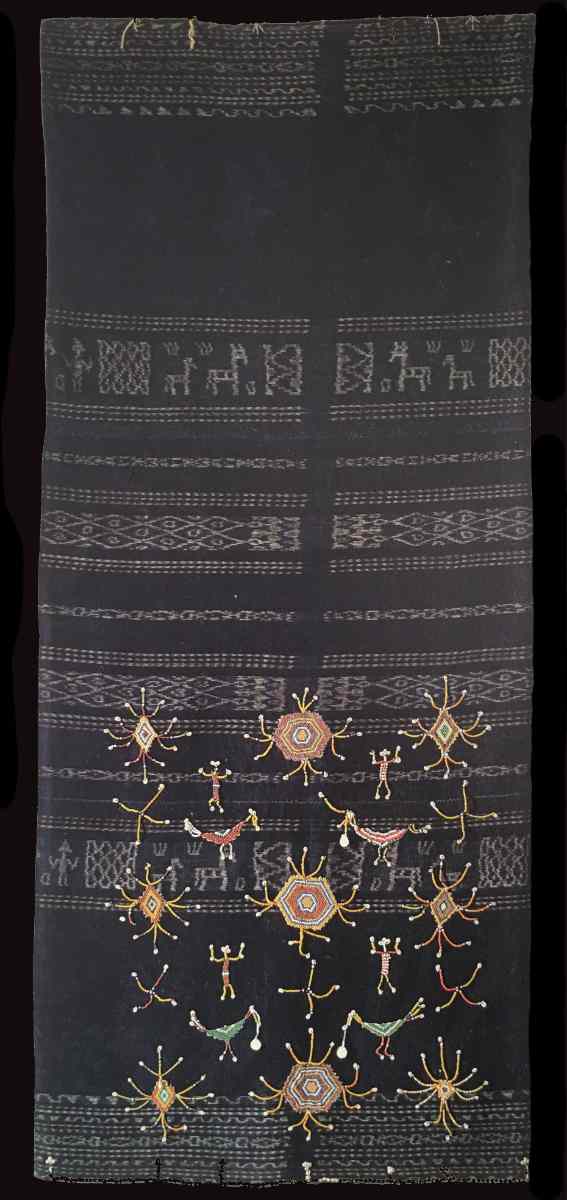

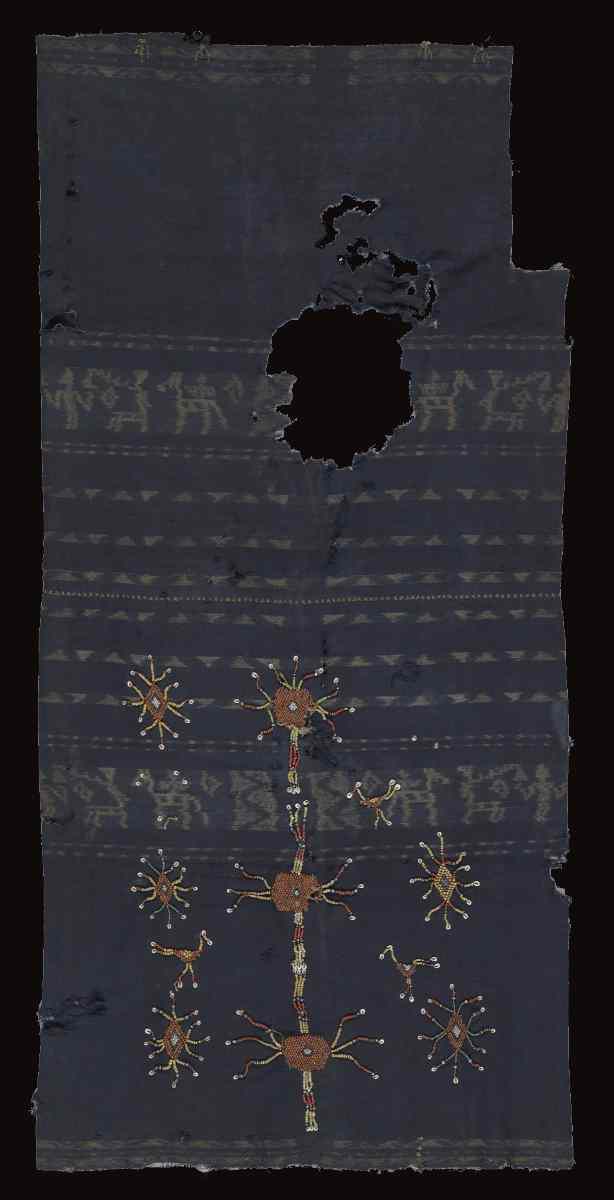

The lawo butu is a three-panel or occasionally a two-panel cotton tube-skirt elaborately embellished with imported coloured glass beads and split nassa shells. The skirt panels are decorated with warp ikat and predominantly dyed indigo blue, although some examples contain narrow rows of ikat naturally dyed a rust-coloured brown, possibly obtained from sappanwood or morinda.

A lawo butu in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia

While women exclusively produced the majority of textiles throughout eastern Indonesia, Roy Hamilton claimed that the production of a lawo butu was a collaborative effort between a woman and a man, the woman binding, dyeing and weaving the cloth and the man appliqueing the shells and beadwork (1984, 109). However, this might not be universally true – Father Piet Petu photographed two women repairing the beading on a damaged lawo butu (see later).

Like other Ngada lawo sarongs, the lawo butu was worn high under the armpits with the top of the tube fastened front to back over the shoulder with a series of ties known as kondo. It covered the entire torso, reaching down either to the calves or the ankles. Some were worn with a waistbelt while others were not.

Yet a lawo butu was more than just a sarong – it was a precious clan heirloom, commissioned by a male clan leader of high status. After his death, the skirt was known by his name. For this reason, lawo butu were sometimes referred to as lawo ngaza, ‘named skirts’ (Hamilton 1984, 109). Only women of the highest rank could wear them for the most sacred ceremonial occasions, such as the inauguration of a new clan house or the erection of a new ngahdu ancestral shrine. Construction of such a shrine could result from a desire for prestige or as a response to disasters. When not in use, lawo butu were carefully stored in baskets within the clan house along with other treasures such as gold jewellery. The beads themselves were highly valued. As the sarongs became decrepit, the beads were removed and were used to decorate new sarongs. Consequently, many of the beads used on the lawo butu were of considerable age, used by generation after generation.

According to one report, lawo butu also played a role following the birth of a child by a member of the Ngada aristocracy (Kjellgren 2007, 236; Ellis 2013, 241). They were apparently employed in a ceremony to receive the child during its formal introduction to the community. However, this is not reported elsewhere in the anthropological literature.

The beads were probably originally acquired through trade, although their exact origin remains a mystery. However, some Ngada villagers maintained a belief that beads, along with other forms of wealth, originally grew on a single tree planted by two orphans (Hamilton 1984, 108). Cut down by greedy villagers, the tree fell in such a way that nearly all the wealth it carried was lost to the island of Java and only the beads remained on Flores!

After the completion of each lawo butu, the maker was obliged to perform a kalaneo ceremony of thanksgiving to their ancestors, not only blessing the textile but also releasing the maker from their cloth.

It seems that the production of traditional lawo butu ceased many decades ago. Many were eventually acquired by local small-time dealers, ending up in museum and private collections, often passing through galleries in Bali on the way.

Return to Top

Lawo Butu Types and Motifs

Lawo butu have been produced in a variety of styles and designs – every example is unique.

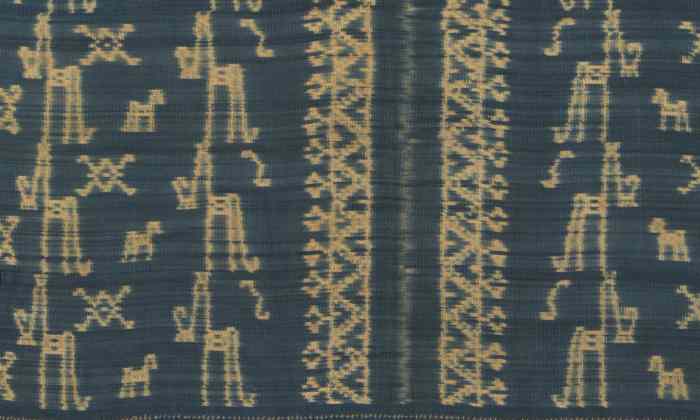

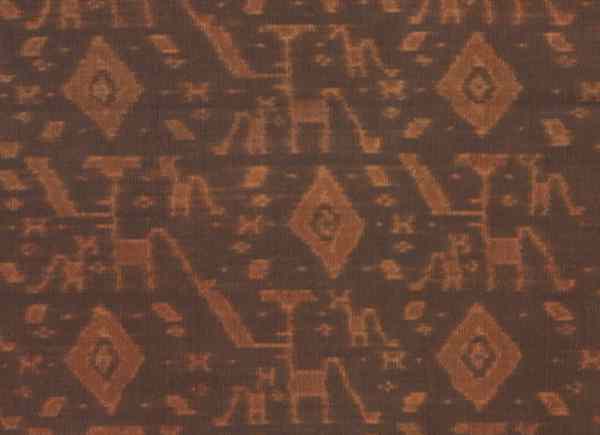

The ikat designs on the skirts varies enormously. Roy Hamilton stated that most beaded sarongs have a centerfield format, but in some cases banded sarongs were beaded as well (Hamilton 1994, 109). However, from our survey of museum examples, banded sarongs appear to be more common than those with centerfields.

Some banded examples have only a few simple ikat bands while others are covered in clusters of bands. Some are exclusively indigo dyed while others have reddish-brown warp stripes or striped meanders. Some even have a mixture of white and reddish-brown motifs. Many have a lateral row of split nassa shells sewn along the outer selvage of the bottom panel.

The most common ikat motifs are stick-like horses, diamonds and pointed tumpals, some terminating with bela riti earrings. Horses, known as jara, were a symbol of wealth and status and in the past were vital in hunting and warfare. A few mix horse motifs with anthropomorphic figures. Some have interpreted the larger horse motifs as elephants, having a raised trunk and long tail.

According to Katharina Paba from Borani hamlet in Langar village a few centre field and banded lawo butu have rectangular X-like kawe pere motifs that represent the shaped threshold which marks the doorway into the inner chamber of every traditional Ngada house. The minor motifs in the end sections are mainly geometric. The simplest of these are wide dashes called lie or beads. Zigzag motifs are called gheo while a wider version is called the wai manu or chicken foot motif.

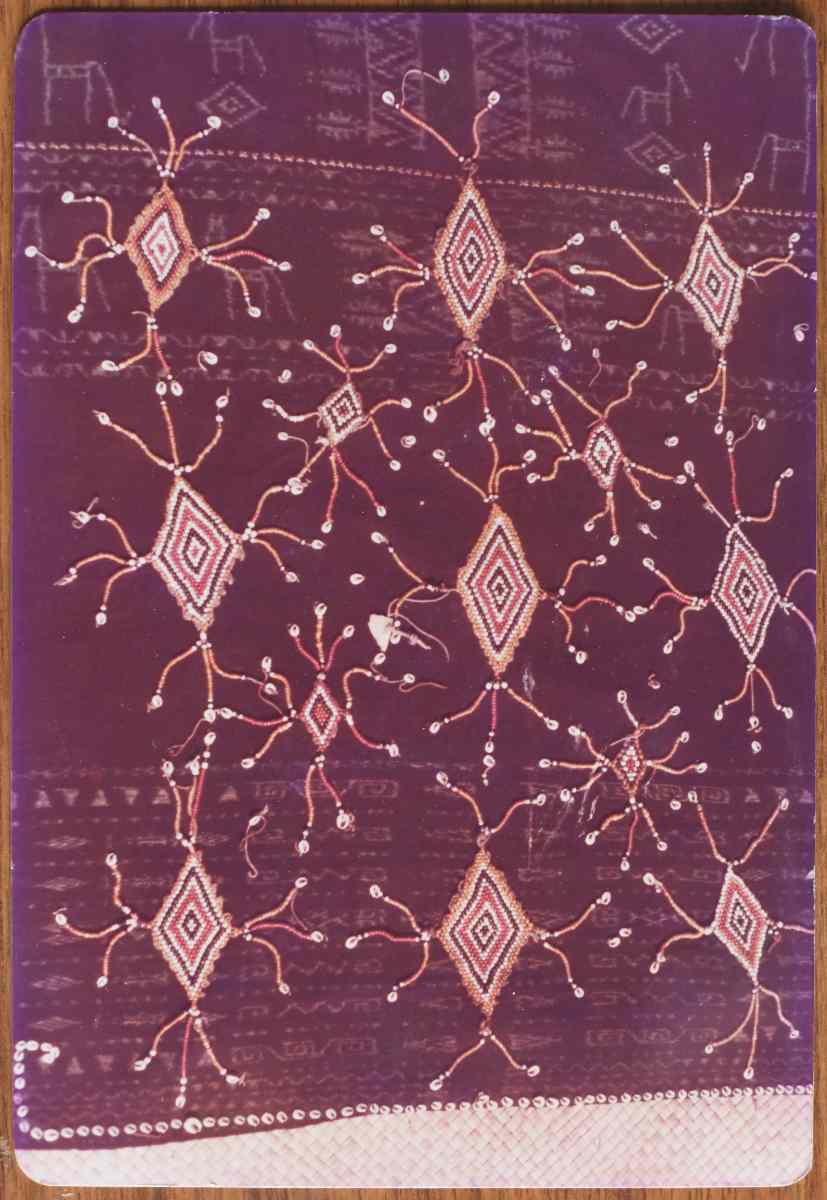

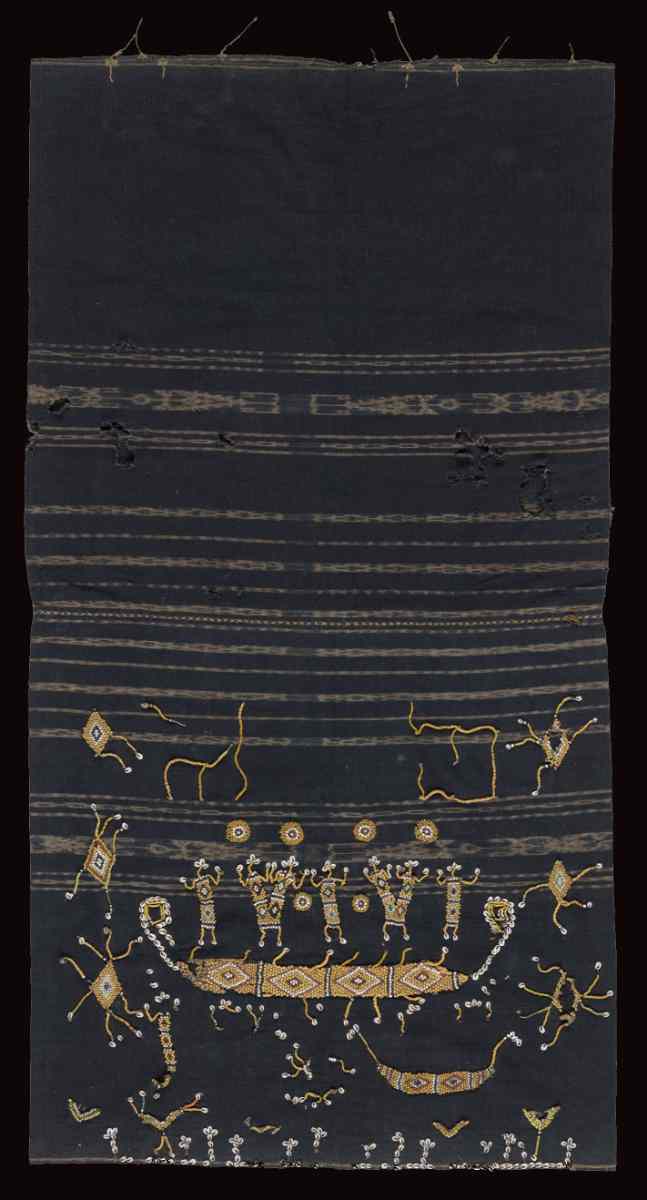

The beading was always confined to the front section of the bottom half of the lawo butu. The beads and nassa shells were not sewn onto the sarong singly but were first strung together to form figures such as diamonds or hexagons that could then be attached in their entirety.

The exact meaning of many of the beaded motifs remains uncertain. Trying to identify the meaning of traditional ethnic motifs can be a fool’s errand as many may have been lost in the mists of time, assuming that they originally had any meaning at all. Nevertheless, this has not stopped many writers attempting to decipher Ngada iconography.

Some have suggested that the beaded diamonds are fertility symbols, representing the female vulva. Others that the diamonds with wavy protrusions are kubi or octopus motifs. Some have suggested that hexagonal motifs represent crabs, while birds are most likely depictions of chickens, the most common sacrificial animals. Anthropomorphic figures probably represent ancestors.

Anthropomorphic figures and chicken motifs

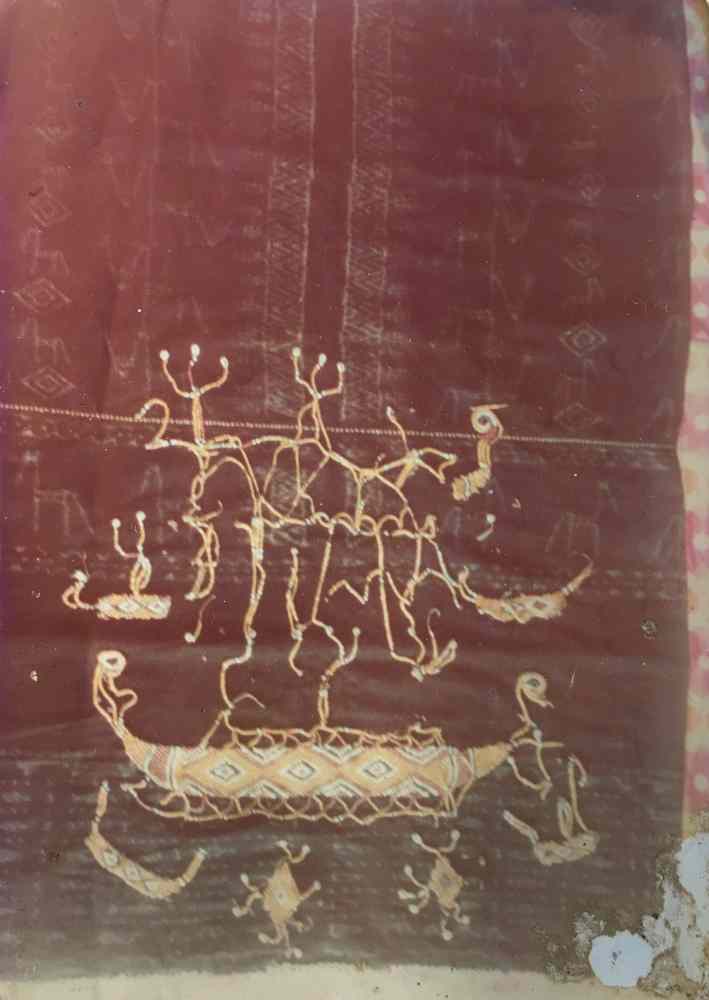

Motifs of boats or kowa along with their human crew are said to symbolise the original voyage of the Ngada founding ancestors to Flores Island from the west.

Return to Top

Lawo Butu and Father Piet Petu SVD

Unfortunately, we have been unable to locate any early photographs taken of Ngada noblewomen wearing a lawo butu. Although Charles Le Roux photographed both women and men wearing traditional clothing at some time between 1915 and 1919, he did not manage to capture the image of a lawo butu, probably because such sarongs were only worn for infrequent special ceremonies.

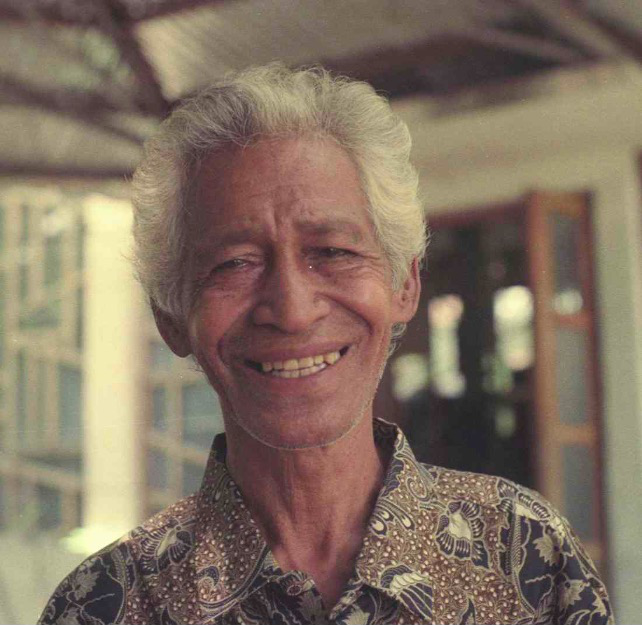

Fortunately a number of Ngada lawo butu were photographed by the Catholic priest, Father Piet Petu SVD, born Sareng Orinbao, taken in the Ngada region in the mid- to late-1980s or early 1990s. Some of these were published in his 1992 book: Seni tenun suatu segi kebudayaan orang Flores (The art of weaving as an aspect of Flores culture). Most of these photographic prints are now in the collection of the Bikon Blewut Museum at Ledolero, near Maumere on Flores Island, whose curator kindly permitted us to copy them.

Sareng Orinbao was born on 3 February 1919 in the village of Nita in the Sikka district of Flores. His parents were village chiefs, so his family were highly regarded. His mother died when he was just 10-years-old.

Piet Petu SVD at the Blikon Blewut Museum

In 1936, at the age of 17, Sareng Orinbao entered the secondary seminary of St. Yohanes Berkhmans at Todabelu in Mataloko, just east of Bajawa in Ngada district. It was run by the Societas Verbi Divini (SVD, Society of the Divine Word). In the middle of his studies, he became involved with Father Theodorus Lambertus Verhoeven, SVD, who seems to have involved him in some small archaeological excavations around Mataloko, developing his interest in, and knowledge of, anthropology and archaeology. In 1950 he was involved with Verhoeven’s first major expedition to the important cave of Liang Bua (literally ‘Cold Cave’).

In 1951, at the age of 32, Sareng Orinbao was finally ordained as a priest, adopting the name Piet Petu SVD. On his ordination day he baptized his parents as Catholics. From 1952 to 1954 Father Piet Petu studied history in Jakarta, obtaining a B1 degree. Later, between 1961 and 1962, the Catholic church sent Piet Petu to continue the study of spirituality at an SVD community in the small village of Nemi, overlooking Nemi Lake in the Province of Rome. While there he took the opportunity to visit a number of European museums in order to learn about museum management practices.

It is not exactly clear where he was located following his return to Flores but it seems that by the late 1960s, he was based at Ende. Following a request from the Congregation for German Language Studies in Munich, Germany, he had begun to write a book about the mythical identity of Flores Island. Nusa Nipa: Nama Pribumi Nusa Flores (Snake Island: the indigenous name of Flores Island). This was finally published in 1969 by Arnoldus Printers, Nusa Indah Ende Publishing, which was allied to the Catholic mission on Flores.

In the meantime, Piet Petu embarked on detailed research into the cultures of Flores, producing various written works and gradually accumulating an important collection of ethnographic artefacts. He initially focused on the local Lio people, followed by the neighbouring Ngada and Sikka regions and later the other islands apart from Flores. His research included a comprehensive study of Flores ikat weaving, the traditional farming practices of the Lio, the cosmology of the Sikka Krowé and the marriage practices of the Sikka people.

Back in Ngada district, Dr. Verhoeven had never had any ambition to establish a museum. After he returned to the Netherlands in 1967, the ancient artifacts he had collected between 1950 and 1965 remained in the Todabelu seminary in Ngada district, cared for by the local SVD priests.

In 1975 Drs. Guus Cremmers SVD, a young and energetic Dutch missionary, was appointed as a Lecturer in Arts and Philosophy of Literature at the Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Katholik Ledalero, the Roman Catholic seminary based in Nita village, about 8km from Maumere. On his initiative and with the approval of the SVD Ende Regional Leadership at that time, Verhoeven's discoveries were transferred to the Ledalero Seminary under the supervision of Cremmers.

In 1982, the head of the SVD Seminary at Ledalero arranged for Piet Petu to be transferred from Ende to become a lecturer in cultural history and to establish a professional museum, taking responsibility for the scientific and systematic curation of Verhoeven’s collection. This led to the opening of a small museum (with only 99m² of space) the following year. Piet Petu named the museum Blikon Blewut, based on a local a Sikka Krowé poem and meaning ancient artefacts. Thanks to his initiative, the objects gathered over the years by different SVD missionaries were finally organised and presented in a structured way.

Father Piet Petu continued collecting local ethnographic artefacts including textiles, publishing Seni Tenun Suatu Segi Kebudayaan Orang Flores (The art of weaving as an aspect of Flores culture) in 1992. It was illustrated with many of the coloured photographs that he had taken of the museum’s textile collection, as well as of people making and wearing those textiles. Some reports suggest that he gave up responsibility for managing the museum in 1999. He died on 24 November 2001 at the age of 82.

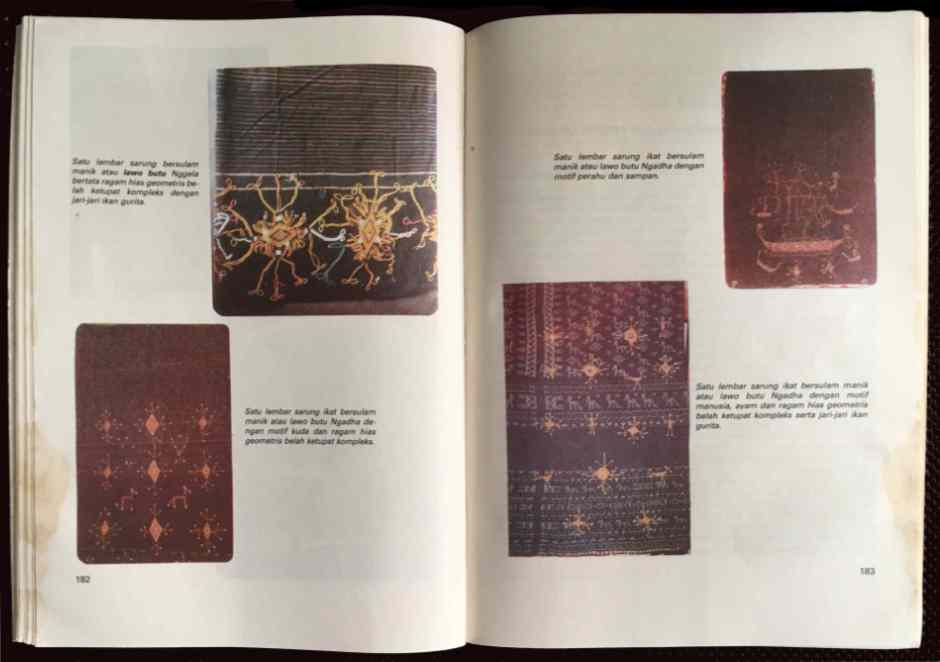

Two pages from Father Piet Petu’s book, illustrating four lawo butu, three from Ngada and one from Nggela village in the Ende region

Father Piet Petu only had access to a simple camera so the resolution of his images is poor. Frustratingly, only a few of the images in his photograph albums were given captions, so the precise location and context of the majority remains unknown. Nevertheless, we have identified and copied several dozen images of Ngada men and women dressed in traditional costume, out of which there were just over a dozen with women dressed in lawo butu and with details of the beadwork.

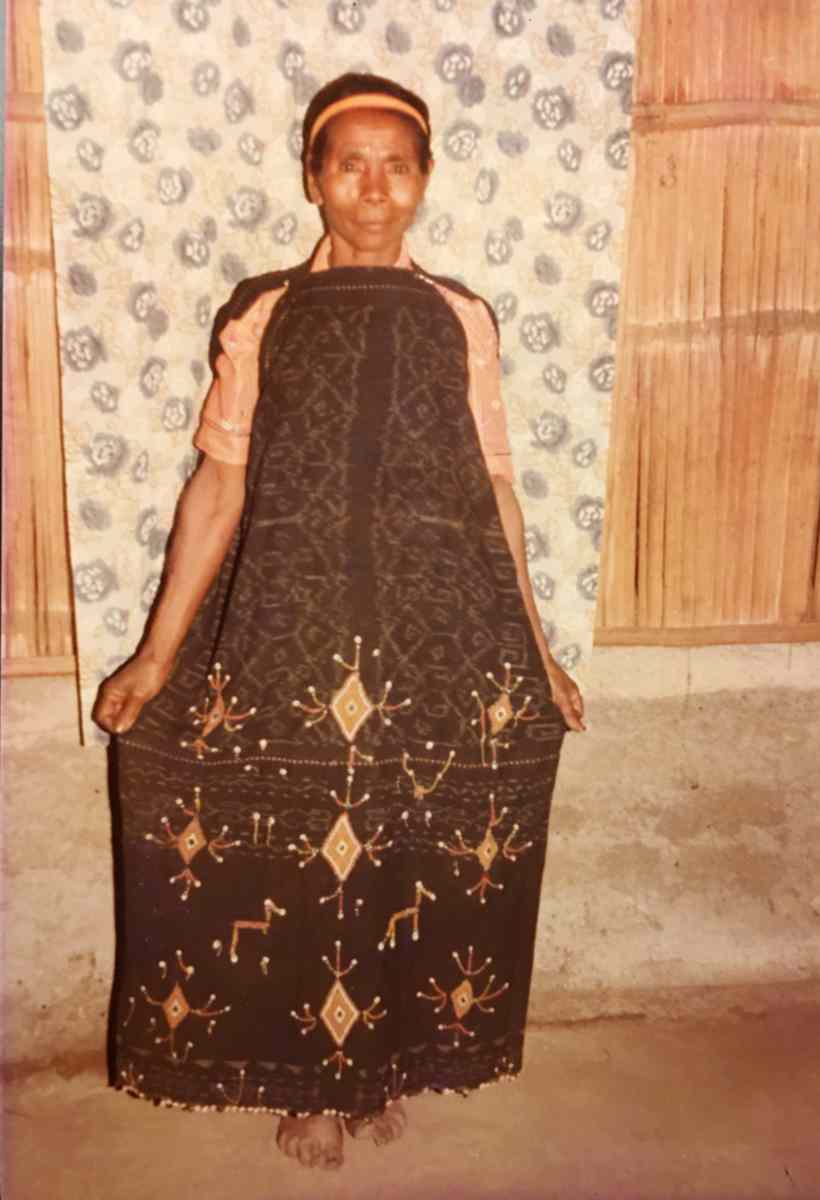

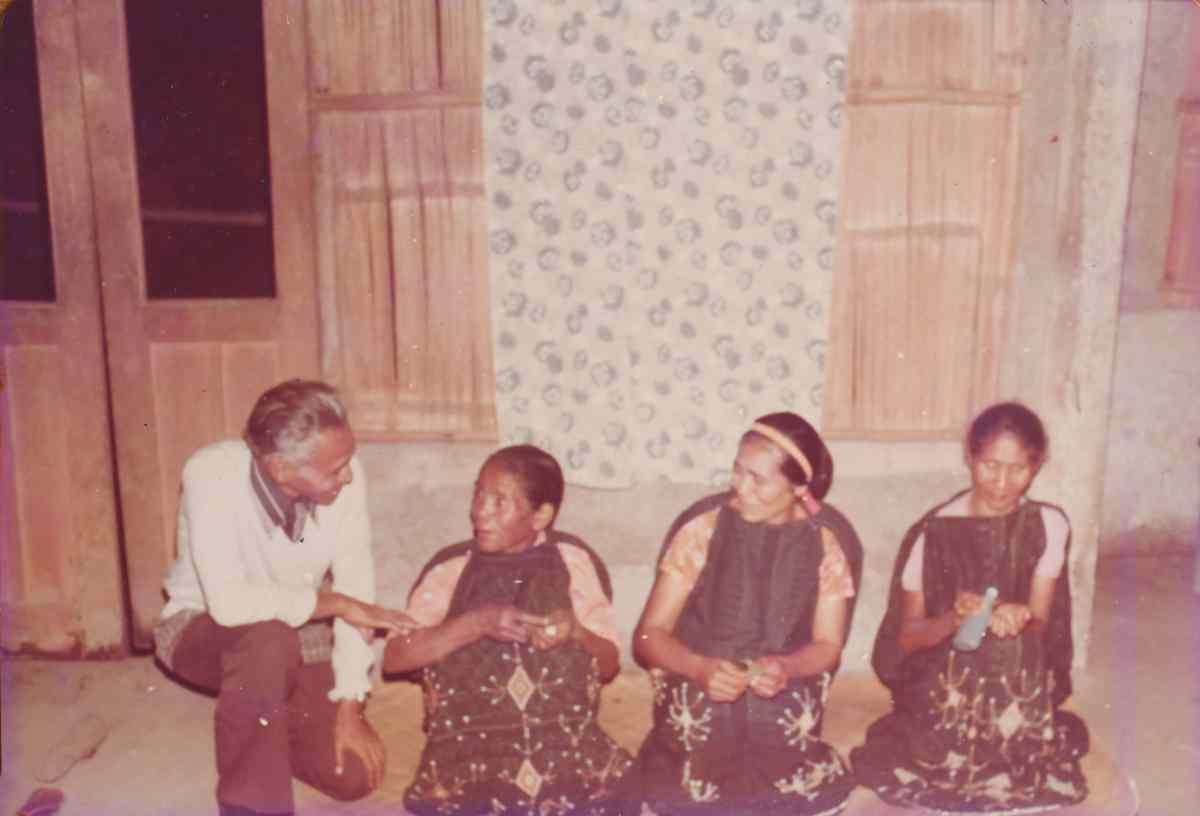

The first of these shows a woman modelling an unusual lawo butu with only two panels, a large main panel ikatted with a lattice of diamonds and a lower panel with a very wide plain indigo band. The next three, taken in the same indoor location, show three seated women chewing betel nut, each dressed in a lawo butu.

A woman modelling a lawo butu with an unusual ikatted pattern

Above: Three women dressed in lawo butu flanked by two men

Below: Father Piet Petu talking to the same three women

A close-up of the three women wearing lawo butu

The mystery in all of the above photos is that the four lawo butu appear to be two-panel sarongs but having the appearance of three-panel sarongs with the upper panel removed. Yet most examples in private and museum collections have three panels with kondo shoulder ties affixed to the top of the uppermost panel. The length of most of these sarongs ranges from 150cm to 200cm, with many in the range 185cm to 200cm. Such garments could only be worn with the top panel folded down or removed. This is clearly illustrated in the photo below:

An old photograph of woman wearing a Ngada lawo butu

Interestingly there are a few two-panel lawo butu in museum collections, such as the example in the British Museum, collected in Langa in 1989, that is only 100cm long, and the sarong restored in Singapore by the Heritage Conservation Centre (Komatsu 2010).

The next two photographs show women wearing lawo butu that cover them from shoulders to mid-calf, and can therefore be only around 125cm long.

Above: Woman wearing a lawo butu and an orange sash

Below: A group of Ngadha women in festival dress, some wearing lawo butu

Most of the lawo butu in Father Piet Petu’s photographs appear to be in relatively good condition, unlike those taken in the Lio village of Nggela. They also appear to be similar in their beaded design with an array of diamond-shaped figures sprouting wavy arms and stylised horses and chickens.

Detail of a lawo butu in relatively good condition

However, the following image shows a lawo butu with no diamond motifs but just strings of detached beads.

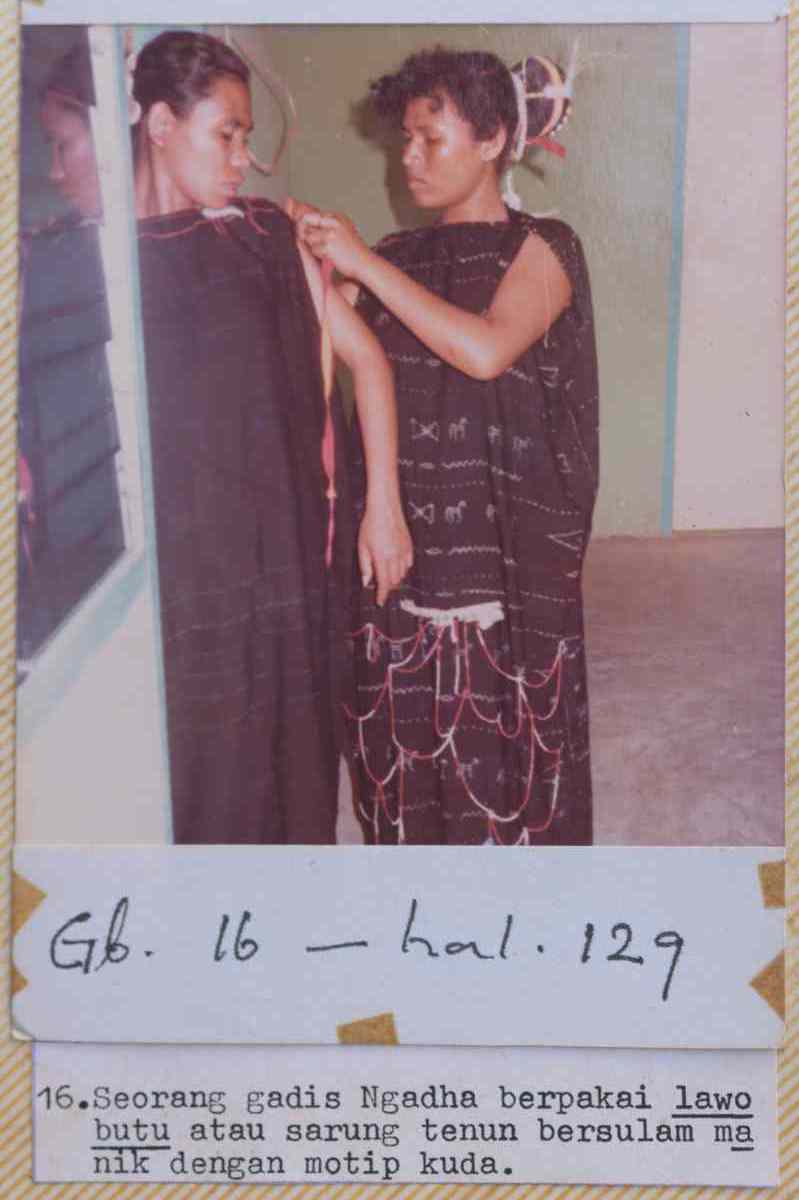

A Ngada girl wearing a lawo butu with hanging strings of beads. The caption reads: a Ngada girl wearing a lawo butu or woven sarong with a horse motif embroidered with beads.

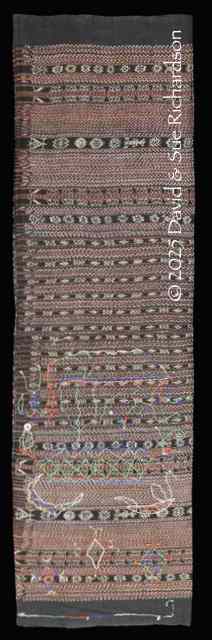

Another captioned image of the lower reverse side of a lawo butu refers to the narrow bands of ikat at the bottom of the sarong. It reads as follows:

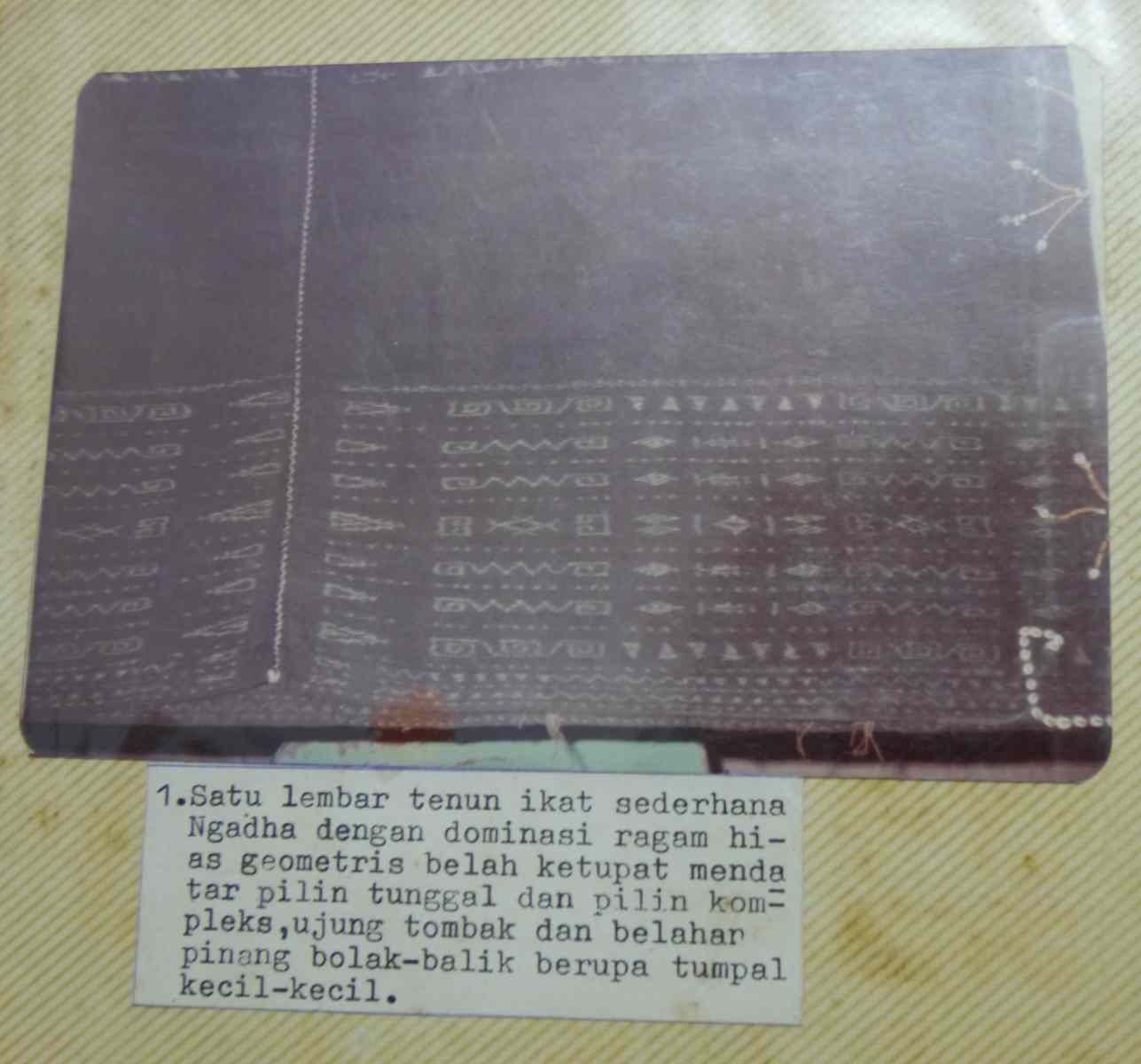

One panel of simple Ngada ikat weaving with a dominant geometric decorative motif of horizontal rhombuses, single meanders and complex meanders, spearheads and alternating pinang branches in the form of small tumpal.

The ikat bands at the bottom of a lawo butu

The final image was taken by Father Piet Petu in a Ngada village at the time of an important and rarely staged ceremony and feast, probably the erection of a new ngadhu shrine. The ngadhu is a forked post supporting a conical roof structure that represents the male founding ancestor of a house or sa’o. It is the location where buffalo are sacrificed. When a new ngadhu is erected, the wooden post is first carried horizontally and root first from the place where it has been carved into the village on top of a huge bamboo scaffold. The sa’o pu’u, the most senior elder of the sa’o, stands on the leading trunk end of the post while the sa’o lobo, the second most prominent elder, stands atop of its tip end (Smedal 2009, 211).

While most of the participants are male, two women walk at the head of the procession, one wearing a lawo butu.

A Ngada procession with a woman at the front dressed in a lawo butu

Return to Top

Examples from Museums and Private Collections

A significant number of Ngada lawo butu are held in museums, especially in the USA and Australia, as well in important private collections.

The majority of these sarongs have been appliqued with large beaded hexagons and/or diamonds, each bearing projecting strands of beads and shells. These are accompanied by smaller beaded motifs, such as anthropomorphic figures, chickens and horses. A few have been appliqued with beaded boat motifs.

It is clear from these preserved examples that there were several distinct styles of lawo butu. Because of the lack of provenance of most of these textiles it is impossible to say whether these reflect different village or regional styles.

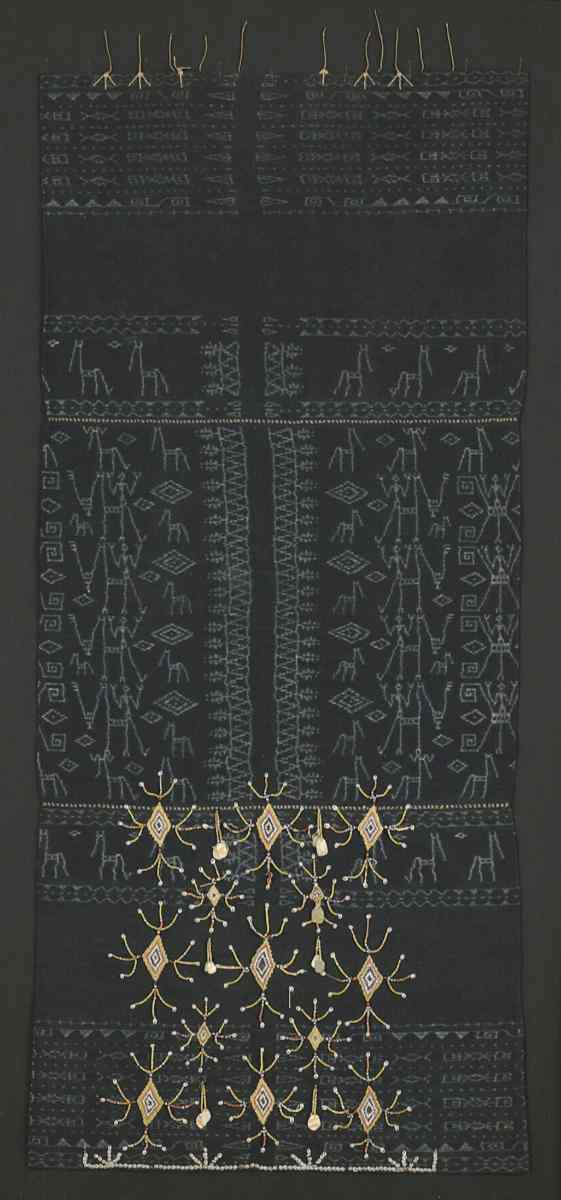

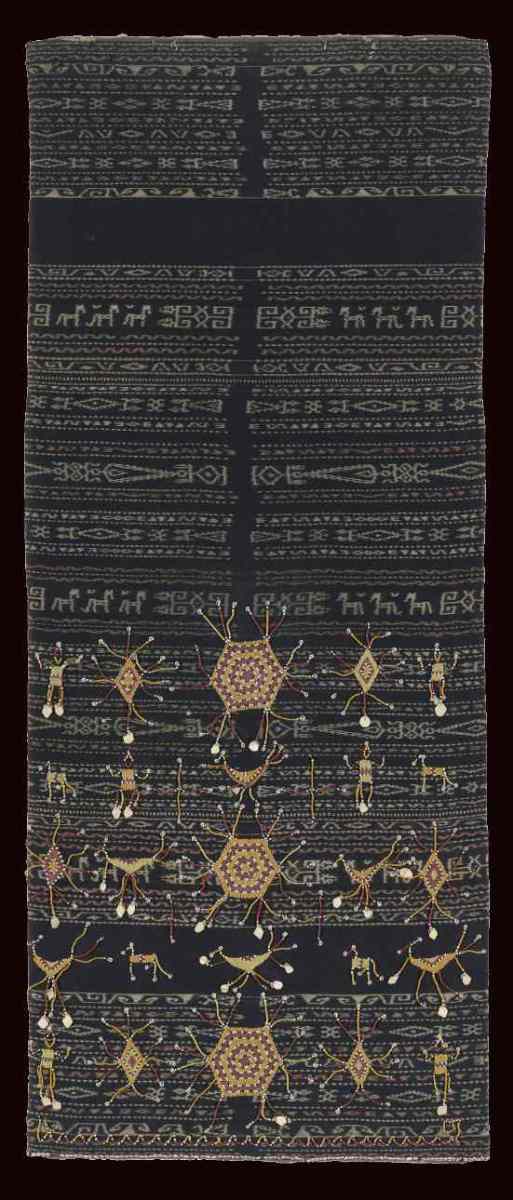

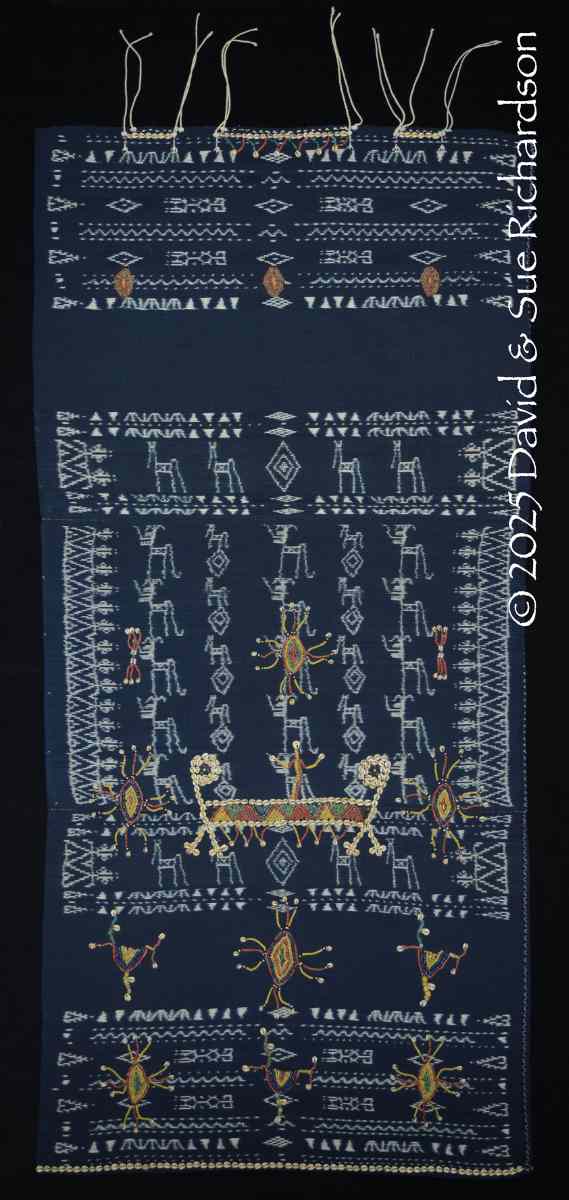

Type 1. Three-panel lawo butu with centre fields

In most of these examples, the central panel is completely covered with a lattice of stick-like horse (jara) motifs, sometimes alternating with diamonds, while each end panel has a wide plain indigo band and narrow outer bands of simple geometric motifs. In most examples, all three panels are divided into two sections by two columns of arrow-like tumpal motifs, frequently combined with a bela riti earring motif.

Above: Lawo butu. Yale University Art Gallery Collection. 158cm x 76cm

Below: Lawo butu. National Gallery of Australia Collection

The lawo butu owned by the Art Institute of Chicago is unusual in having a centre field lattice containing columns of alternating horse and diamond motifs flanked by columns of anthropomorphic figures. some appearing to be riding on horses or possibly elephants.

Lawo butu. Art Institute of Chicago Collection. 186cm x 83cm.

Meanwhile the centre field lattice on the lawo butu previously owned by Anthony Granucci is exclusively filled with simple horse motifs.

Lawo butu. Ex-Anthony Granucci Collection. 196cm x 80cm.

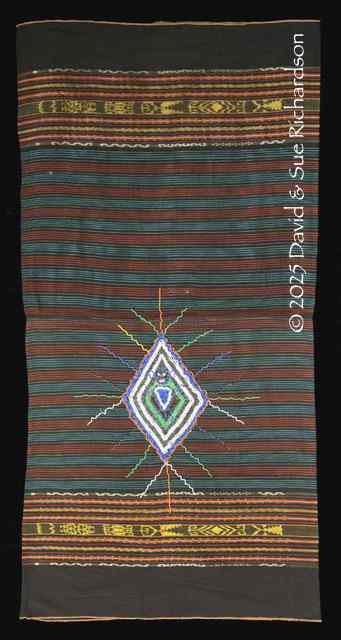

The next example of this type of lawo butu was collected in 1985 from the remote hamlet of Majamala in Kecamatan Golewa, which is 5.5km east of Bena. It was woven from hand-spun cotton naturally dyed with indigo. The ikatted sections are woven with a double warp while the plain sections are woven with a single warp. The weft is a heavier gauge than the warp.

Lawo butu from Majamala. Richardson Collection. 198cm x 79cm.

In some lawo butu, the stick like quadrupeds have a long tail and a trunk ending with an upward curl, more like an elephant than a horse. Similar motifs appear on some of the lawo and zawo sarongs from the Endenese and Lio of the Ende region to the east of Ngada.

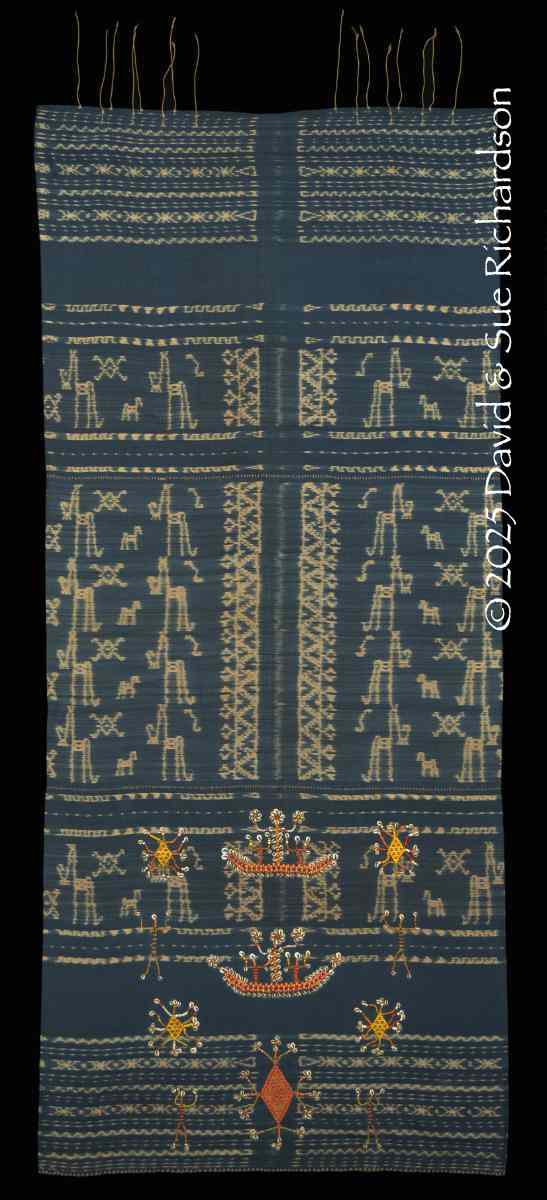

This can be seen in the following lawo butu that was collected in Langar, 5km south of Bajawa. It is unusual for having being embellished with two boat motifs.

Above: Lawo butu from Langar. Richardson Collection. 182cm x 80cm. Below: Details of the elephant motifs in the Langar lawo compared to those in an Endenese zawo.

In most lawo butu the longitudinal seam is positioned at the back. However, in the following lawo butu it has been positioned at the side, thus allowing the beading to be applied across a whole undivided lattice of horse and diamond motifs. Unlike most lawo butu embellished with a boat motif, the boat in this example has an even number of crew.

Lawo butu. Ex-Anthony Granucci Collection. 155cm x 80cm.

The final example from the Dallas Museum of Art also has the longitudinal seam positioned at the side. It is also an exception, having a centre panel decorated with a fine diagonal lattice of diamonds flanked by two columns of tumpals and bela riti earring motifs.

Lawo butu. Dallas Museum of Art Collection. 174cm x 79cm.

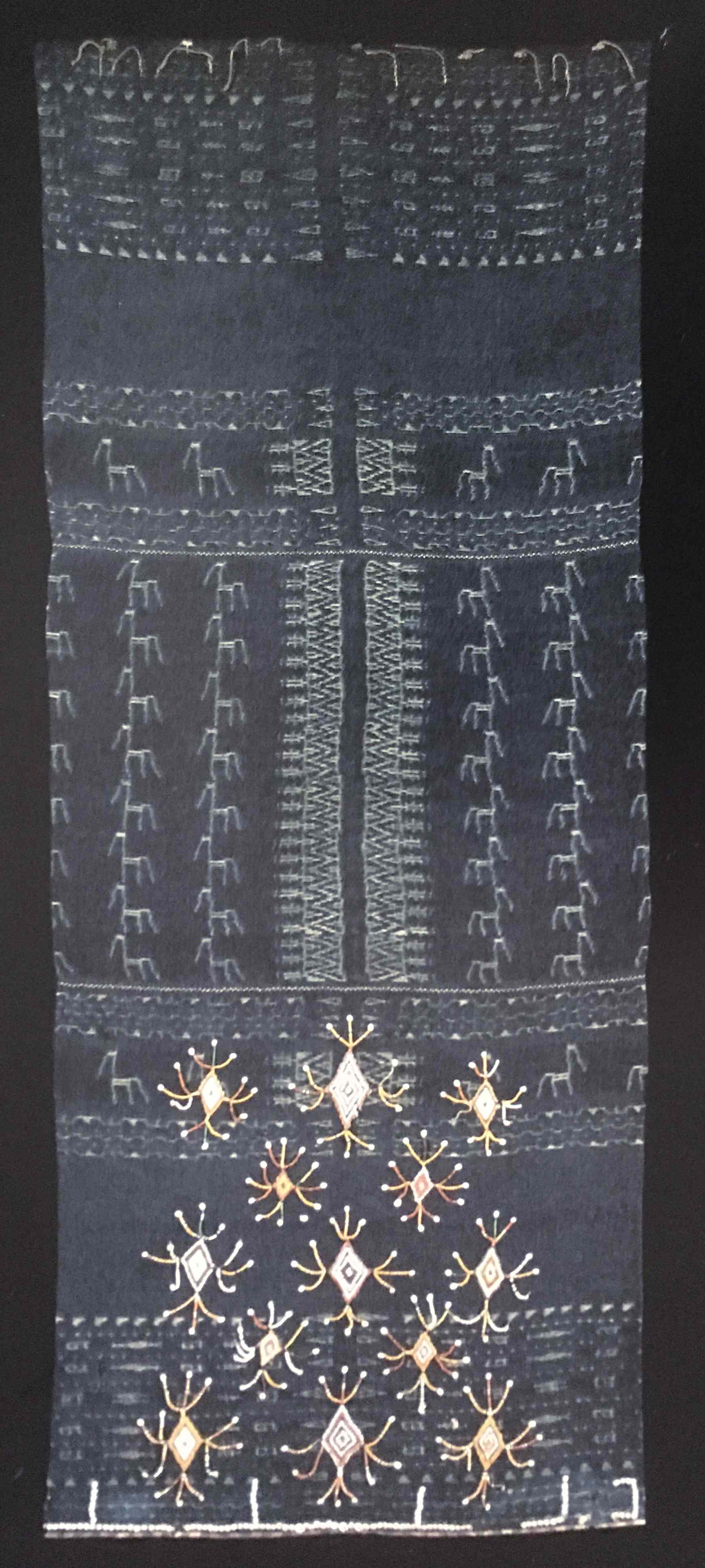

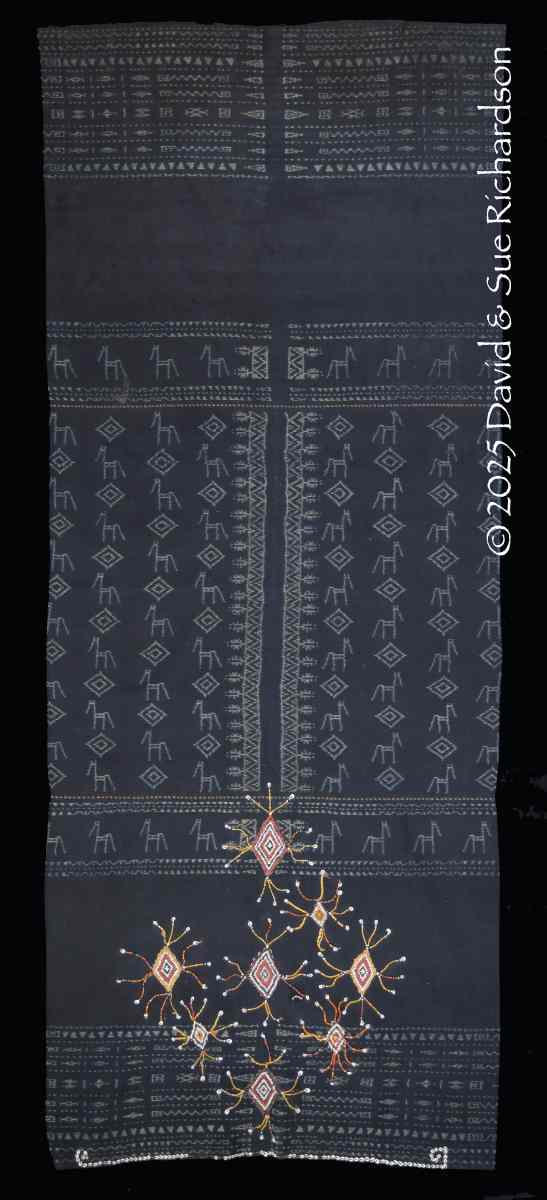

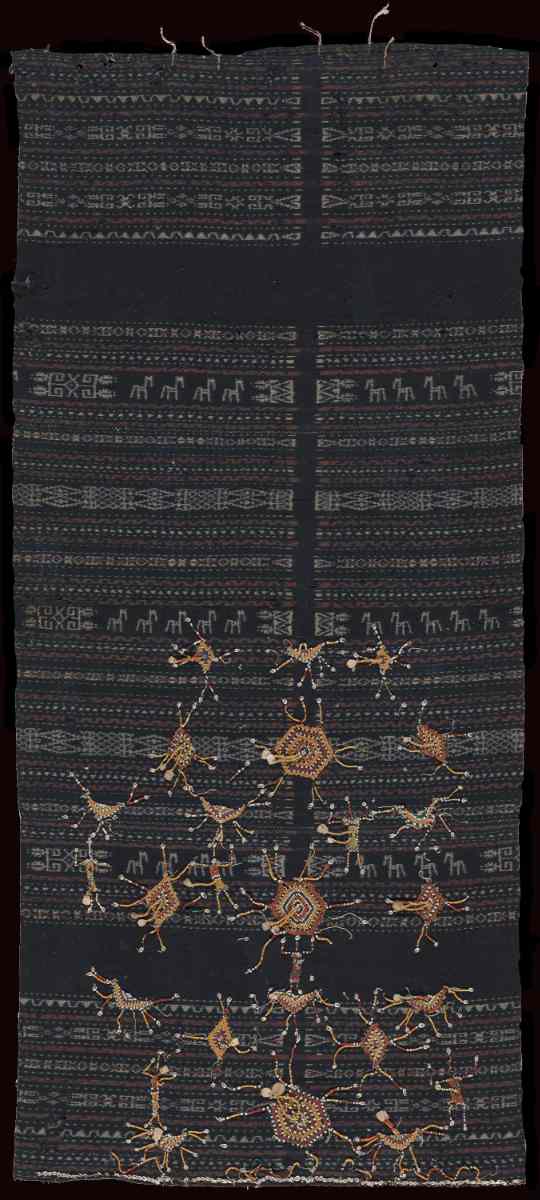

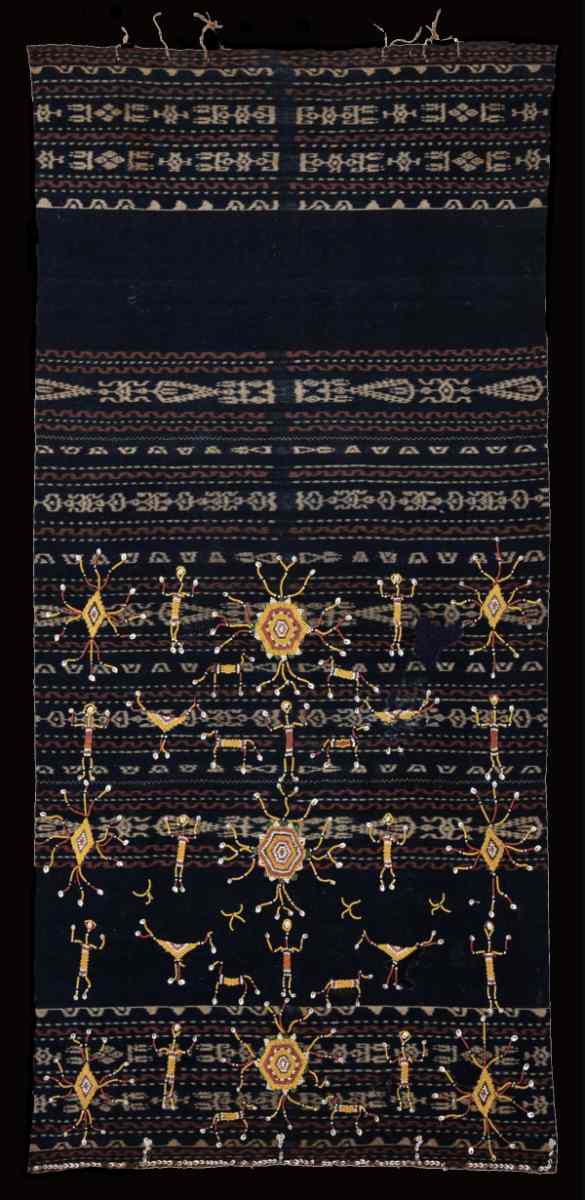

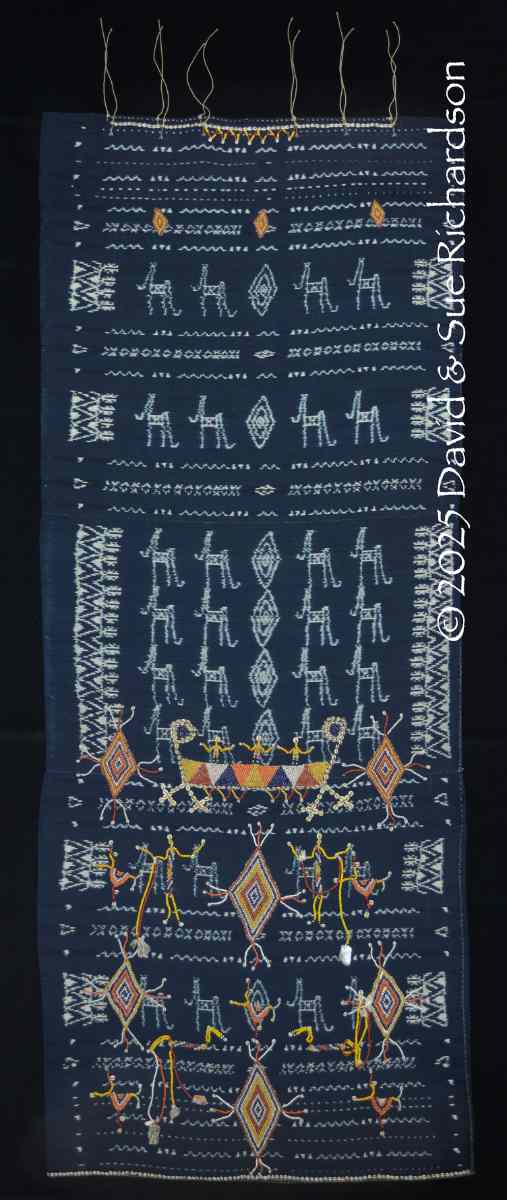

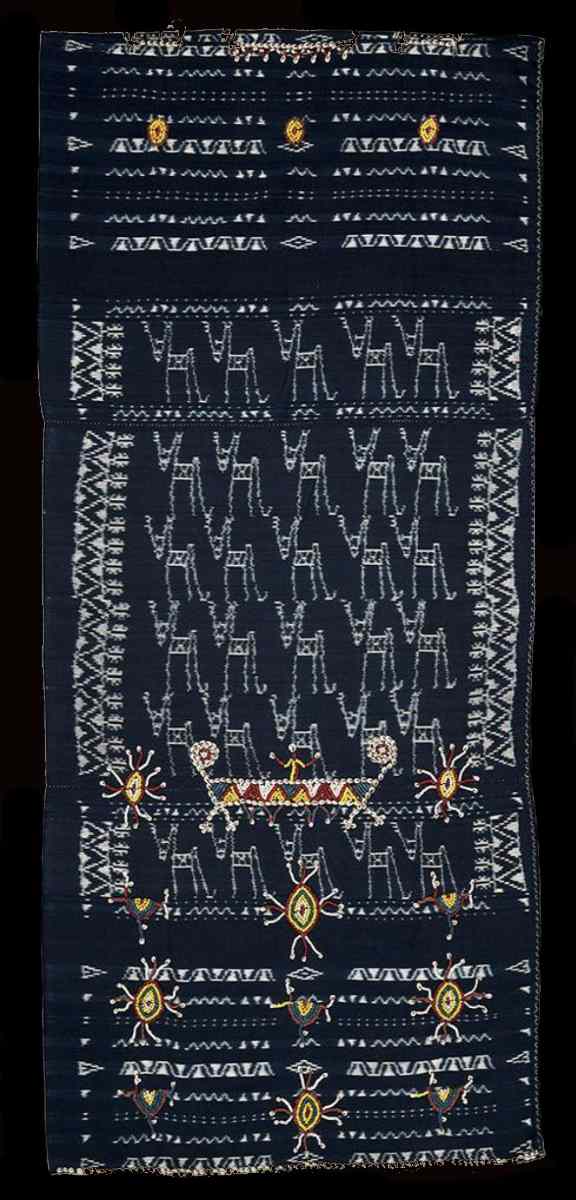

Type 2. Lawo butu with three banded panels

In this type of lawo butu there is no centre field – all three panels are decorated with bands of warp ikat, the outer panels having a wide plain band of indigo and a terminal cluster of narrower ikat bands. Some contain brownish warp stripes and brownish ikat bands decorated with a continuous meander.

A narrow longitudinal central strip of plain indigo divides all the ikat bands into two sections. On some lawo butu of this type, some ikat bands contain horse motifs, while on others the ikat bands are filled with purely geometric motifs.

The first exhibit of this type was collected by Robert Holmgren and Anita Spertus and later acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Some of the geometric motifs are quite complex.

Lawo butu. The Metropolitan Museum Collection, New York. 188cm x 76cm

The next two lawo butu are quite similar to the one from the Met, apart from having a few horse motifs in some of the lateral bands.

Above: Lawo butu. National Gallery of Australia. 185cm x 79cm.

Below: Lawo butu. National Gallery of Victoria Collection. 175cm x 79cm.

The following lawo butu from a private collection is unusual in having been embellished with a dozen beaded anthropomorphic figures.

Lawo butu. Private collection.

The lawo butu held by the Honolulu Museum of Art is perhaps the most exceptional banded example of them all, having been beaded with nine complex hexagons along with eight anthropomorphic figures, four chickens and two horses. It is shown with the top panel folded over a supporting bar.

Lawo butu. Honolulu Museum of Art Collection.

By contrast, some lawo butu in this category have far less banding than the above examples.

Lawo butu. Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection. 175cm x 73cm.

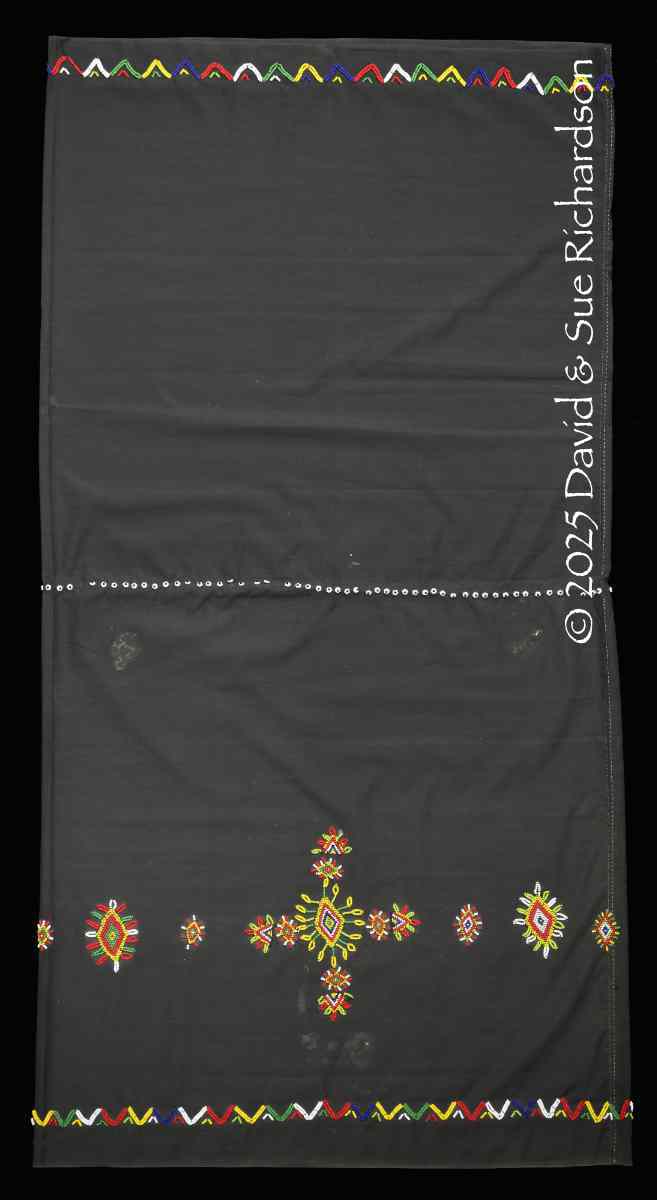

While others are more subtly decorated with very narrow bands of ikat. The final example was collected from the ancestral ceremonial village of Bena, located on the lower slope of Gunung Inierie. It is considered to be the first village in the region that was settled and is described as original – in other words it has always occupied its present site. Today the village has a population of 326 living in 45 houses. They are all Catholic.

The lawo butu from Bena. Richardson Collection. 133cm x 78cm.

Type 3. Two-panel lawo butu

Two-panel lawo butu appear to be much less common in collections than three-panel versions. Those that we know about tend to have one wide band of ikat on each panel, with simple narrow bands on the inner sections and a broad plain band on the outer section. In some, the main ikat band is decorated with horse motifs.

Above: Lawo butu. Dallas Museum of Art Collection. 157cm x 74cm.

Below: Lawo butu. Yale University Art Gallery Collection. 150cm x 68cm

Meanwhile a second damaged two-panel lawo butu in the Yale collection has even simpler warp ikat bands but has been embellished with a more elaborate boat motif along with a group of anthropomorphic figures, two of which appear to be Siamese twins.

Lawo butu. Yale University Art Gallery Collection. 132.5cm x 68cm

One very unusual example has panels that are not mirror symmetric, the upper panel being narrower and bearing two main bands of ikat. Sadly, most of its original beads are missing although many of the nassa shells that were positioned at the outer parts of the bead motifs remain in place. It looks like the sarong has been deliberately stripped of its beads.

Lawo butu. Collection of the British Museum.

Is it possible that these old two-panel examples are an earlier version of the Ngada lawo butu that was superseded by the three-panel version?

Return to Top

Modern Lawo Butu

In the Ngada region today only one woman has the skills to make high quality lawo butu. She is Mama Katharina Paba who lives in the Borani hamlet of Langar village, just under 3 kilometres south of Bajawa, the capital of the Ngada region. Katherina began weaving in the early 1970s but it was not until 1986 that she began hand spinning her own cotton, while setting up indigo vats next to her house.

Shortly afterwards she had a dream in which an old woman came to her with some beads (Ingram 2000). A few days later she had a second dream in which the old woman showed her an old textile from the clan treasury. One month later she experienced a similar dream. She concluded that these dreams were a message from the ancestors, instructing her to examine the clan’s sacred lawo butu.

With support from her mother, the elders gave her permission to open the basket in which the lawo butu was stored. First the clan leaders performed a ceremony, sacrificing a chicken and reading its liver, which confirmed the ancestors approval. After opening the basket, she found a second basket inside containing the remains of the lawo butu. It had been eaten by mice and was in a dreadful state with only a few threads and beads remaining. Before closing the basket, Katherina removed three detached nassa shells and took them home.

Katherina decided that she would make a new lawo butu, modelled on the one she had just seen, incorporating the three nassa shells she had taken from the clan treasury. Although other local weavers had attempted to make lawo butu before, none had been able to bead their sarongs correctly. However, Katherina did not encounter similar problems and her finished skirt was well received. Her initial intension had been to sell the lawo butu to pay for her children’s schooling but on reflection she decided to keep it for herself. It was initially used in a ceremony for the inauguration of a church and then later for several house blessing ceremonies.

In the meantime, Katherina continued making lawo butu for sale, supported by some of her neighbours. Yet it was only after participating in a weaving conference in Kupang in 1994 that she realised the unique nature of her sarongs. Out of four hundred weavers, only a few used natural dyes, none of which followed a process as complex as hers. Furthermore, none were embellishing their textiles with beads like Katherina. The following year she was visited by the Governor of her province, Nusa Tenggara Timur, who commissioned her to make a lawo butu for him. He encouraged her to pass on her skills to the younger weavers. However, none were interested in dyeing with indigo, which they regarded as dirty work.

Later that year Katherina fell seriously ill. For the next three years she consulted various doctors on Flores and on other east Indonesian islands, all to no avail. In desperation she approached a local shaman, who diagnosed that her problems arose from her first lawo butu. She needed to return the three nassa shells to the clan treasury along with her sarong. A special ceremony was organised, which included the sacrifice of a red pig and the offering of red rice and red coconuts to the ancestors, and this was followed by the placement of the lawo butu into the treasury. The remedy was successful and over the following days Katherina made a full recovery.

Over the years Katherina has produced scores of lawo butu, most embellished with modern beads. However, in 1999 some were commissioned by Threads of Life in Bali, who provided Katherina with a stock of rare Indo-Pacific drawn glass beads originating from ancient graves in Jember, East Java, which had been recovered from farmer’s fields during tilling.

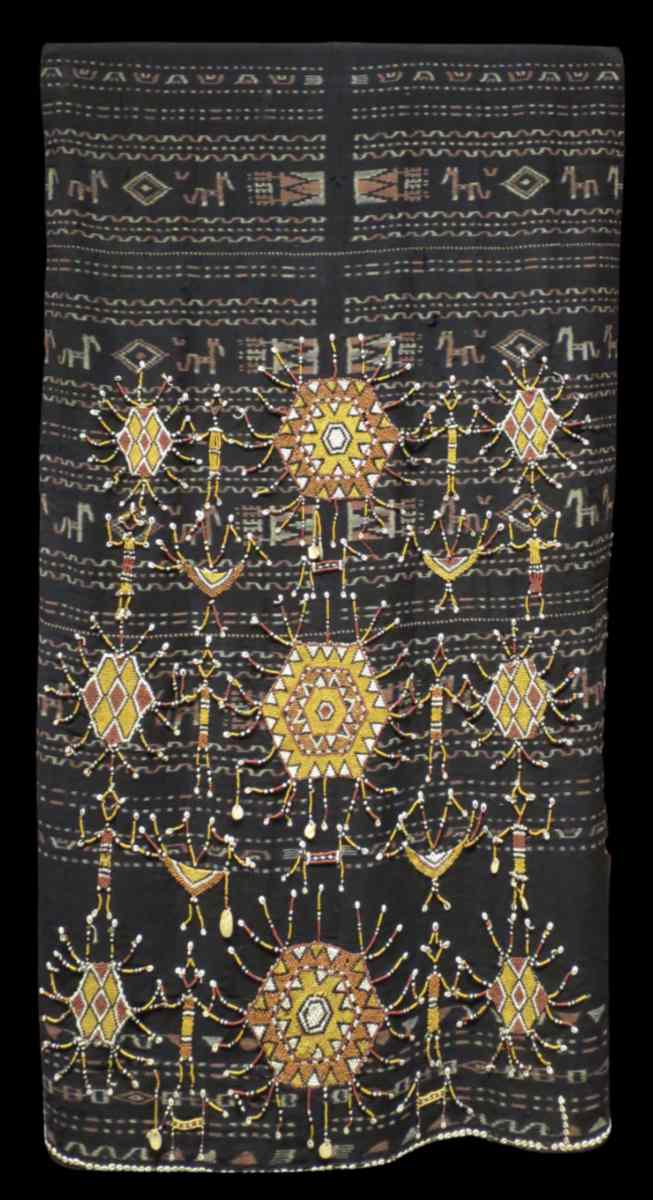

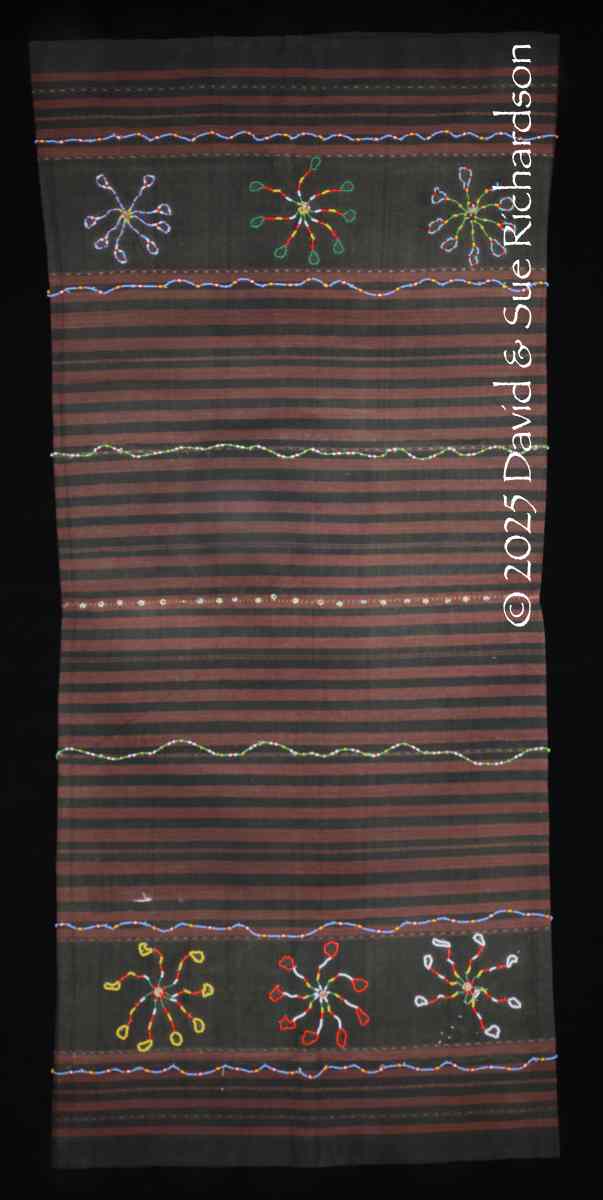

The following two lawo butu were made by Katherina Paba using hand-spun cotton and those same antique glass beads. Katherina bound and dyed the yarns and added the beads but her neighbour, Maria Meo wove the cloth. For the wefts, Mama Katharina used thread that had been drop spun by either her, her mother, or her sisters. For the warps, she bought finer 2-ply hand-spun cotton from the market at Ende.

Above and below: Two lawo butu made by Katherina Paba incorporating antique glass beads. Richardson Collection. 154cm x 74m and 189cm x 76cm.

For dyeing the yarns, Mama Katharina used eleven indigo dye vats, which were constantly topped up with indigo leaves. For each dyeing cycle, each bundle of tied threads was passed through each dye vat. It was then beaten on a rock with a wooden paddle to force the dye into the threads before being hung up to dry. The process was repeated until the correct depth of colour was obtained, a process that could take up to three years. Some were stored for up to eight or ten years before weaving to enable them to deepen in colour.

All of Katharina’s lawo butu have been ikatted with stick-like horse motifs and some include a column of large X-shaped kawe pere motifs, representing the threshold to the oné sa’o, the sacred inner part of the traditional Ngada sa’o or house. They also all feature a beaded boat or kowa containing an odd number of human passengers.

Over the years a number of Katharina’s lawo butu have been acquired by museums, such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Seattle Art Museum and The Powerhouse Museum in Sydney.

Above: Lawo butu. The Powerhouse Collection, Sydney. 165cm x 76cm.

Below: Lawo butu. Seattle Art Museum Collection. 171 x 74cm.

There are other weavers in Ngada Regency that have attempted to make lawo butu. However, none are able to match the quality achieved by Mama Katherina.

A lawo butu with new beads displayed on the road from Waibela Bay to Gurusina

Return to Top

Restoring Old Lawo Butu

Although most of the lawo butu in museum and private collections are in good condition, some immaculately so, a few have missing and/or detached beads. It is not surprising that a ceremonial sarong embellished with delicate beading that has been in use from generation to generation becomes progressively damaged. This is particularly so given how badly Ngada villagers look after their traditional textiles – something that we have observed during the time that we have spent in their villages.

Yet the beading on some lawo butu is so pristine that it raises one’s suspicions.

Unfortunately, because so many of these sarongs have no provenance, we have no record of their long history. In the past some restoration undoubtably took place locally. Severely damaged lawo butu were recycled, the beads carefully removed and reapplied to a newly woven sarong. Some partially damaged lawo butu were also repaired locally. Father Piet Petu took one photograph of two Ngada women repairing the beading on a lawo butu. This is noteworthy since it has always been claimed in the literature that the beads were applied by men.

Two women repairing a lawo butu, photographed by Father Piet Petu

In a few cases, some lawo butu have been restored by museum conservation departments. Miki Komatsu has described the process of restoring an old two-panel lawo butu at the Heritage Conservation Centre in Singapore. Dirt was removed from the cloth and the beads were cleaned with deionised water. Then the loose beds were reattached and the fabric of the sarong was stabilised with an internal lining of polyester Stabilex. Finally, the sarong was mounted on and affixed to a padded board to distribute the weight of the beadwork on the lower part of the skirt.

The worry is that some of these pristine lawo butu may have been assembled by middle men or dealers. From our work on Sumba we know that certain individuals manufacture apparently traditional beaded textiles for profit. Some do this honestly and openly but others do this to deceive. They first track down an old un-beaded sarong as a canvas and a stock of antique glass beads and nassa shells, and then commission an artisan to combine them together. The only way to guard against this possibility is to acquire such textiles in the field from the families that have owned them for generations and know their history.

Return to Top

Other Beaded Sarongs from Flores

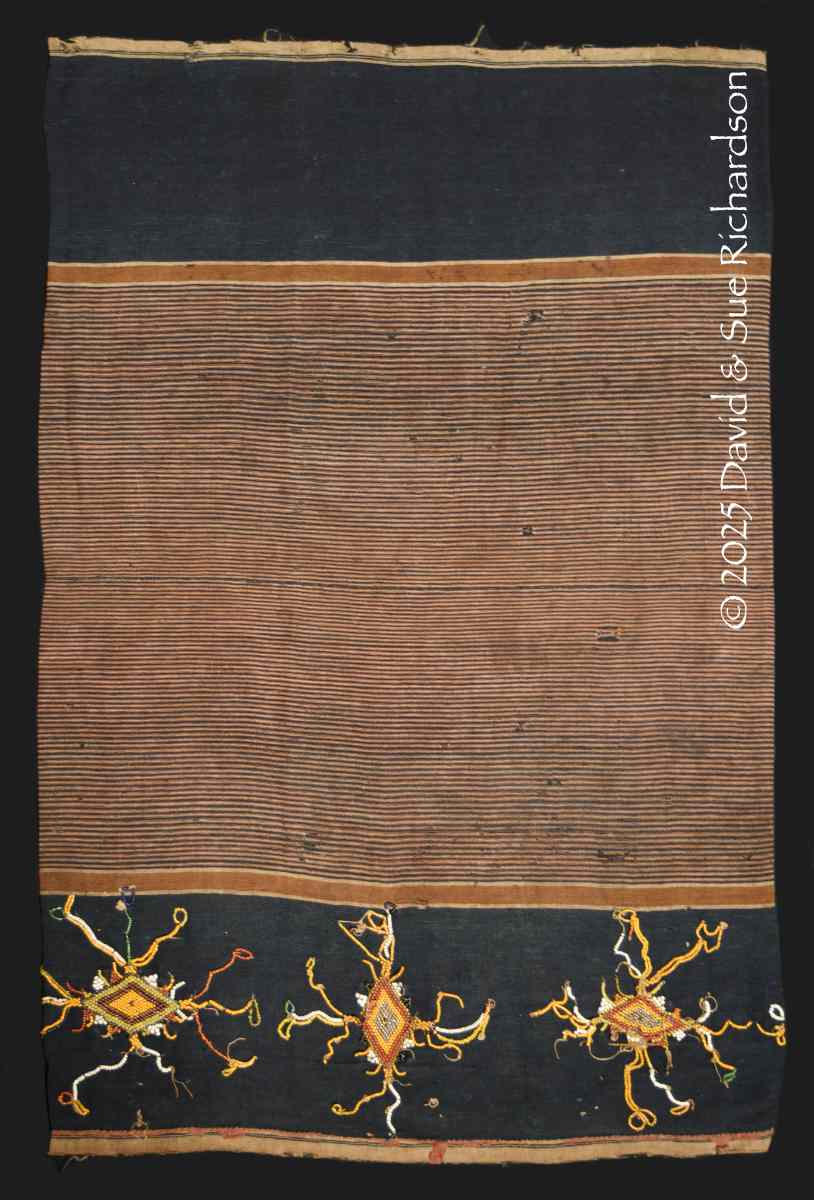

Beaded sarongs are found in other parts of Flores, specifically the Regencies of Ende, Sikka and East Flores. Those made by the Ata Lio, the Ata Sikka and the Ata Tana ‘Ai of eastern Sikka were generally not decorated with ikat and were worn during a rarely staged rain ceremony, only performed when there was fear of an imminent famine following a prolonged drought.

It is unclear whether the Ngada lawo butu was once associated with a similar type of rain ceremony. The anthropological literature makes no mention of such a ritual.

In the Lio region of Ende Regency, the two-panel lawo butu was the most sacred and highest status ceremonial sarong in the village of Nggela, despite being devoid of any ikat. Lio lawo butu were decorated with beads in a similar fashion to the Ngada lawo butu but without the addition of nassa shells. Each lawo butu belonged to the women’s respective social groups, called ‘houses’ or sa’o. They were worn on two respective occasions (de Jong 1996, 172):

- The ceremony of the rain dance or muré, a four-day ceremony authorised by the village council when, due to exceptional drought, starvation was imminent, or when after seven years of fallow, new swidden fields were cleared for the cultivation of mainly cassava and corn. According to local customary law, the period of cultivation of the fields is restricted to seven years on the village land to the west, and then seven subsequent years on the village land to the east. The muré dance was performed in the sacred village centre, the pusé nua, by the young unmarried women from the two highest status matri-clans, who symbolised purity and fertility.

- The meditation or maru ceremony undertaken during the thatching of two of the most important ceremonial houses – the ate sa'o nggua. In this case the lawo butu is worn by married women from two of the highest ranking matri-clans.

These ceremonies were maintained up until the 1930s but then ceased due to the upheavals of the Japanese occupation during the Second World War. A shorter version of the rain dance was revitalised in the early 1960s at the behest of local government officials. However, one report claims that after the muré dance was performed at the court of President Soekarno in about 1963, Nggela was struck by a disastrous famine. The mosa laki responded by performing rituals and sacrificing a buffalo, sprinkling its blood into every corner of the village. Since then, the community became reluctant to perform their sacred dances out of context.

By the 1980s these fears seem to have subsided. The muré dance was performed in 1987 for the visit of the district governor and again in 1988 for a visit of the provincial tourist authorities.

The following lawo butu was owned by Paulina Hawa from Sa’o Labo, who was born in 1962 and wore it at the performance of the muré ceremony in 1988. It was made by her grandmother, Mama Bhoa, also from Sa’o Labo, who was born around 1893 and died in 1967, aged about 75.

The lawo butu made by Mama Bhoa in Nggela about 100 years ago

Richardson Collection

In Sikka Regency the Ata Krowé also had a ceremonial sarong worn at ceremonies aimed at averting a disaster but, in this case, it was worn by a man. It was called an 'utang breké, the Sikkanese word breké referring to the hungry season, the dry season before the next harvest. It was worn by the tana pu'an (the lord of the land, the source of the domain or tana), who had special social and spiritual responsibility for coordinating the clans within and around his domain. According to David Butterworth, this traditional role, which may have disappeared elsewhere in Sikka Regency, remains strong in Romanduru and the surrounding villages (Butterworth 2008). The sacred authority of the tana pu'an can be helpful in resolving issues of land use, land tenure and natural resource exploitation.

Father Piet Petu studied an ‘utang breké in Hewokloang in the Krowé region of Sikka (1992, 161-162) and commented as follows:

In this type of beaded ceremonial sarong ‘utang means sarong and the name breké means starvation because of a lack of food. Wulang breké means the month of hunger. Two months of hunger are distinguished:

- breké geté means the month of great hunger, January, when there is a severe hunger because the food left over from the last season is almost gone and the new crops are not yet ready.

- breké doi means the month of small hunger, February, because the fields start producing a few vegetables and a small amount of young corn.

The people of Krowé Sikka believe in the soul of the earth, Ina Niang Tana Wawa [Mother Land and Earth Below], and the soul of the sky, Ama Lero Wolang Reta [Father Sun and Moon Above]. They form a duality that underlies fertility and the harvest. The ‘utang breké sarong with beads is a symbol of lack of food or hunger. To prevent a destructive famine, the ‘utang breké is worn by traditional functionaries who appeal to the soul of heaven and earth to dispel the destructive elements.

The farming ceremony is called éba goit or banish the onslaught. It involves dressing in the ‘utang breké and appealing to Ina Niang Tana Wawa and Ama Lero Wolang Reta to eradicate the destructive elements and avoid the threat of total hunger.

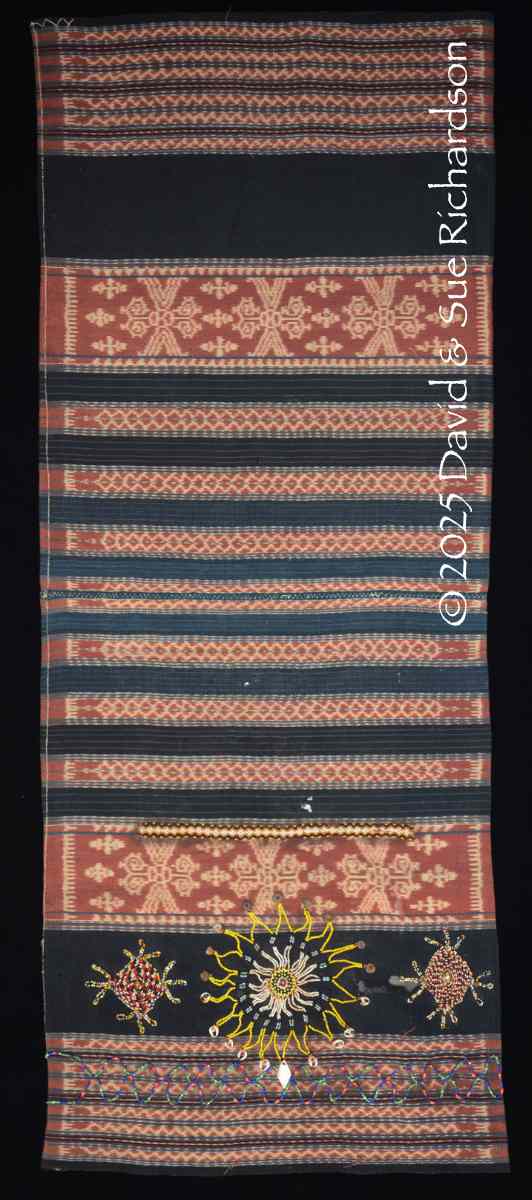

The ‘abstinence’ ‘utang breké is different from the normal Krowé Sikka striped or ikatted sarong, being indigo black and long because the wearer covers himself in the folds of the tube skirt. Normally the ‘utang breké is decorated with simple geometric motifs adapted to the mourning mentality: octopus motifs and rhombuses in the form of bahar habi or bahar riti, geometric symbols aimed at preventing calamity.

The following ‘utang breké was collected at sometime prior to 1992 by Father Piet Petu from the small Krowé village of Romanduru in Kecamatan Kewapante, located on the western slope of Mount Méat about 3½km east of Watublapi in the highlands of Sikka Regency.

Above: A Sikka ‘utang breke collected from Romanduru by Father Piet Petu.

Richardson Collection. 150cm x 76cm.

Below: A model wearing the same ‘utang breke, photographed by Father Piet Petu.

There is limited evidence that some Sikka groups also beaded their own locally made ikatted sarongs. Father Piet Petu acquired an ‘utang welak from the ’Iwang Geté highlands of Sikka that had been crudely embellished with a boat motif and three diamonds with sprouting projection using modern glass beads.

The ‘utang welak/’utang breke acquired in the ‘Iwang Geté highlands of Sikka

Richardson Collection

Surprisingly some Sikka clans added beads to ikatted sarongs that were woven outside of the Sikka region. Father Piet Petu collected a number of textiles of this type.

The first was a Ngada lawo that had been beaded with a boat motif but with much of the surrounding beading partially detached. He classified it as an ‘utang breke, suggesting that the beading had been done locally in the Sikka area. It was published in his 1992 book on Flores textiles so must have been collected sometime earlier.

A beaded Ngada lawo photographed by Father Piet Petu

Father Piet Petu also collected a beaded èi ledo in the Sikka area that had been woven on Savu. This too must have been collected prior to 1992 as the un-beaded upper part was published in his above-mentioned book. We know that while the people of Savu had beads and wore beads, they had no tradition of beading textiles (Duggan 2014). The sarong must therefore have been beaded on Flores.

The èi ledo/’utang breké collected by Father Piet Petu at some time prior to 1992

Richardson Collection

The third example was a tais matin woven on Tanimbar, which Father Piet Petu acquired in the village of Hewokloang in the ‘Iwang Geté region of Sikka. It had been beaded with a large diamond with multiple extended arms. According to the museum curator, this sarong was used to cover the basket of rice seeds at the time of planting a new rice field, to honour the rice goddess Ine Mbu Ine Pare.

The tais matin/’utang breké collected by Father Piet Petu in Hewokloang

Richardson Collection

It remains a mystery as to why some of the Sikka people chose to embellish ikatted sarongs from other parts of the archipelago rather than their own locally made textiles.

The Ata Tana ‘Ai (‘People of the Forest Land’) who inhabit the watershed and tributary valleys of Napun Geté in the mountainous region of far eastern Sikka Regency also have a ceremonial beaded sarong called a nénang butu. It was worn at the gren mahé (‘the celebration of the mahé, the domain’s central ceremonial site’). The gren mahé is the ceremony of ceremonies, in which the whole community participates. It is held every 5 to 20 years under the leadership of the tana pu’an (the lord of the land or source of the domain). In gren mahé during the tudi-laba rite, the dual deity, Nian Tana Lero Wulan (Land, Earth, Sun, Moon), and the ancestors are directly addressed by the ritual leaders of the tana to correct all of the accumulated imbalances in the domain and to ensure the fertility of the land and prevent the outbreak of disease or crop failure (Lewis 2006, 248). It is followed by animal sacrifices. The festival requires many months of preparation and requires one week to complete.

At the gren mahé in Tana Wai Brama in 1980 more than 300 goats and pigs were sacrificed. After decapitation with a ceremonial sword, the severed heads of the goats were rubbed on the mahé altar, a branching tree trunk surrounded by monoliths.

A two-panel nénang butu collected by Father Piet Petu

Richardson Collection

Return to Top

Bibliography

Arndt, Paul, S.V.D. 1954. Gesellschaftliche Verhältnisse der Ngadha, Verlag der Missionsdruckerei St. Gabriel, Wien-Müdling.

Bluming, Martha, 2017. The octopus enigma, HALI, issue 193, pp. 76- 85.

Butterworth, David J., 2008. Lessons of the Ancestors: Ritual, Education and the Ecology of Mind in an Indonesian Community, Doctoral Thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

Cole, Stroma, 2008. Tourism, Culture and Development: Hopes, Dreams and Realities in East Indonesia, Channel View Publications, Clevedon.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2016. Private correspondence.

Ellis, George, 2013. Skirt (lawo butu), Eyes of the Ancestors: The Arts of Island Southeast Asia at the Dallas Museum of Art, pp. 240-243, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Gardener-Medwin, Clare, 2007. The power of dreams, Textile Perspectives, vol. 44, pp. 10-12.

Granucci, Anthony F., 2005. The Art of the Lesser Sundas, pp. 83, 166-167, Editions Didier Millet, Singapore.

Hamilton, Roy W., 1994. Ngada Regency, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, Roy W. Hamilton (ed.), pp. 98–121, Los Angeles.

Hamilton, Roy W., 2010. Beaded ceremonial skirt, lawo butu, Ngada Regency, Flores, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles, p. 326-329, Delmonico Books and Prestel, Munich.

Ingram, William, 2000. The Life of Katherina Paba, Threads of Life, Ubud, Bali.

Ingram, William and Howe, Jean, 2017. Flores: the skin of tradition, Garland Magazine, issue 8, Melbourne.

Kjellgren, Eric, 2007. Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Komatsu, Miki, 2010. Beads and threads – conserving a flores ikat tube skirt, On conservation – perspectives from the Heritage Conservation Centre, pp. 35-39, Heritage Conservation Centre, Singapore.

Kunst, Jaap, 1942. Music in Flores, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, vol. 42, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Lewis, E. Douglas, 2006. A Quest for the Source: The Ontogenesis of a Creation Myth of the Ata Tana Ai, To Speak in Pairs: Essays on the Ritual languages of Eastern Indonesia, pp. 246-281, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Maxwell, Robyn J., 1983. Ceremonial Textiles of the Ngada of Eastern Indonesia, in Connaissance des Arts Tribaux, vol.18, pp. 1–6, Musée Barbier-Müller, Genéve.

Molnar, Andrea K, 1998. Transformations in the Use of Traditional Textiles of Ngada (Western Flores, Eastern Indonesia): Commercialization, Fashion and Ethnicity, in Consuming Fashion: Adorning the Transnational Body, Anne Brydon and Sandra Niessen (eds), pp. 39–56, Oxford.

Orinbao, P. Sareng, 1992. Seni tenun suatu segi kebudayaan orang Flores, Seminari Tinggi St. Paulus, Ledalero, Nita, Flores.

Puirwoaji, Ayos, 2024. Uncharted Territory: The Roots of Curatorial Practices in Eastern Indonesia, Curatography: The Study of Curatorial Culture, issue 7, The Heterogeneous South.

Schröter, Susanne, 1998. Death Rituals of the Ngada in Central Flores (Indonesia), Anthropos, vol. 93, pp. 417–435.

Schröter, Susanne, 2000. Creating Time and Society: The Annual Cycle of the People of Langar in Eastern Indonesia, Anthropos, vol. 95, pp. 463–483.

Schröter, Susanne, 2005. Red cocks and black hens: Gendered symbolism, kinship and social practice in the Ngada highlands, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (BKI), vol. 161, no. 2, pp. 318–349.

Smedal, Olaf H., 2009. Hierarchy, Precedence and Values: Scopes for social action in Ngadhaland, Central Flores, in Precedence: Social Differentiation in the Austronesian World, Michael P. Vischer (ed.), ANU E Press, pp. 209–228, Canberra.

Smedal, Olaf H., 2011. On the Value of the Beast or the Limit of Money: Notes on the Meaning of Marriage Prestations among the Ngada, Central Flores (Indonesia), in Hierarchy: Persistence and Transformation in Social Formations, pp. 269–298, Berghahn Books, New York Oxford.

Smedal, Olaf H., 2011. Unilineal descent and the house – again: The Ngadha, eastern Indonesia, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (BKI), vol. 167, no. 2, pp. 270–302.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 12 March 2025.