Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Wate Senewaken

Wate Tenépa

Wate Tenépa Miten

Wate Tenépa Méan

Wate Tenépa of Lamagute

Wate Tenépa Lakedowak

Wate Tenépa Blaun

Wate Nai Pa

Kewodu

Nowing and Senawe

Senai

The Influence of Indian Patolu

Bibliography

Introduction

The Ilé Apé District

Ilé Apé Ethnography

Local Cotton and its Processing

Binding

Natural Dyes

Indigo

Morinda

Moringa

Réo Bark

Tenor Bark

Mango Bark

Tamarind

Natural Black

Turmeric

Weaving

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

A Fragmented History of Ilé Apé and its Textiles

Women's Sarongs

Wate Mohle or Wate Kerokong

Wate Buraken

Wate Topon or Wate Krokon

Wate Kebo Lolon

Wate Hebaken or Wate Hebak

Wate Ohin or Wate Bala Ohi

Wate Ohin Motifs

The Revot on Ilé Apé

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

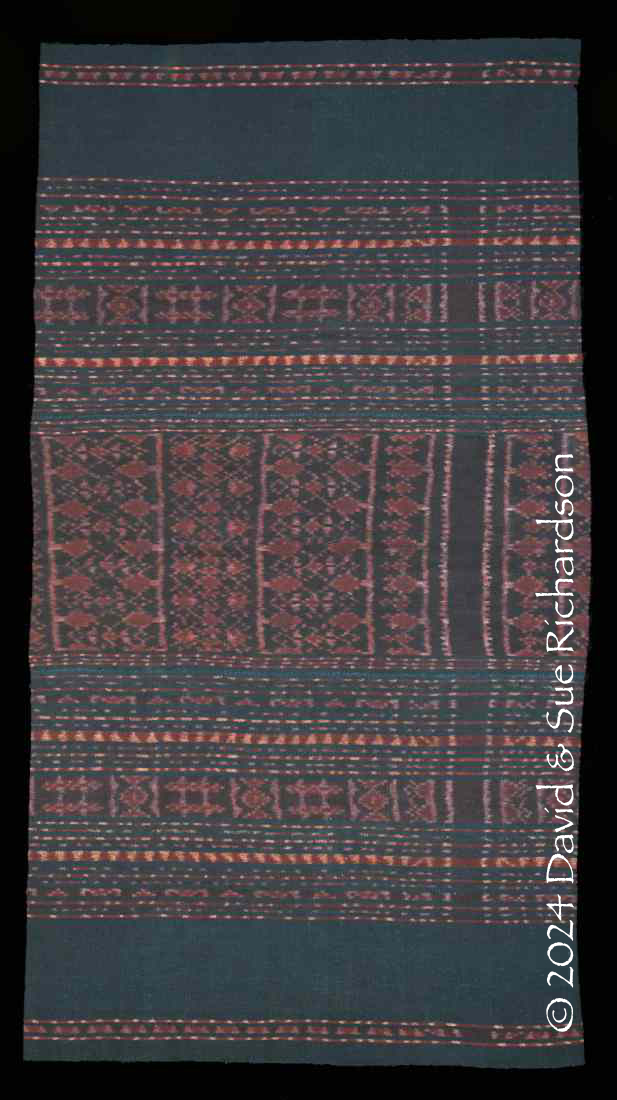

Wate Senewaken

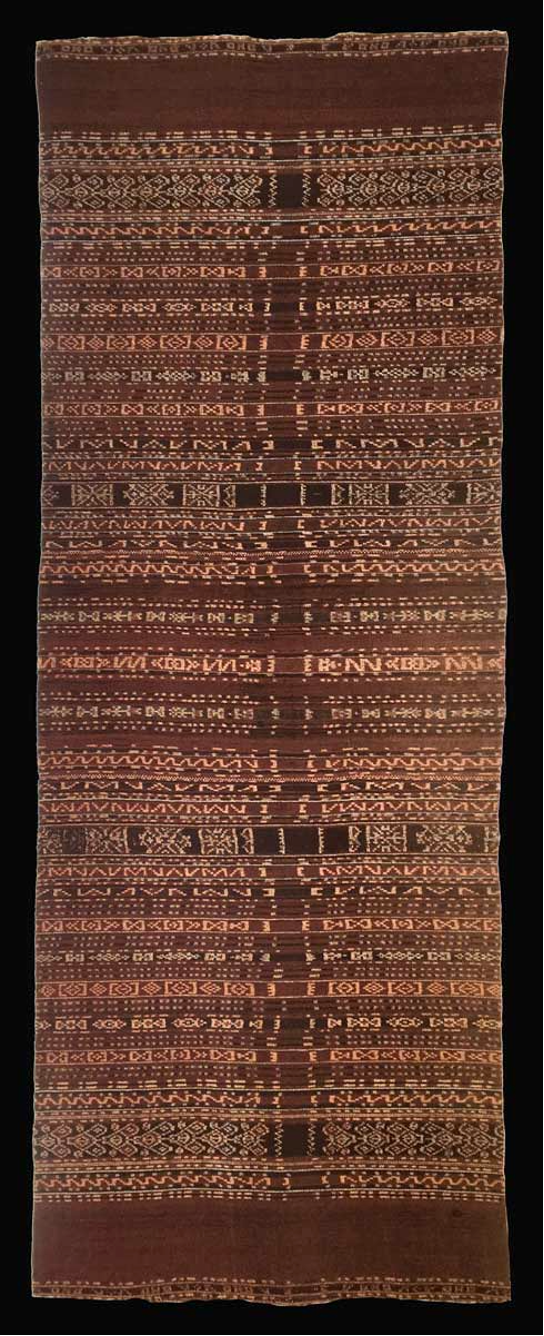

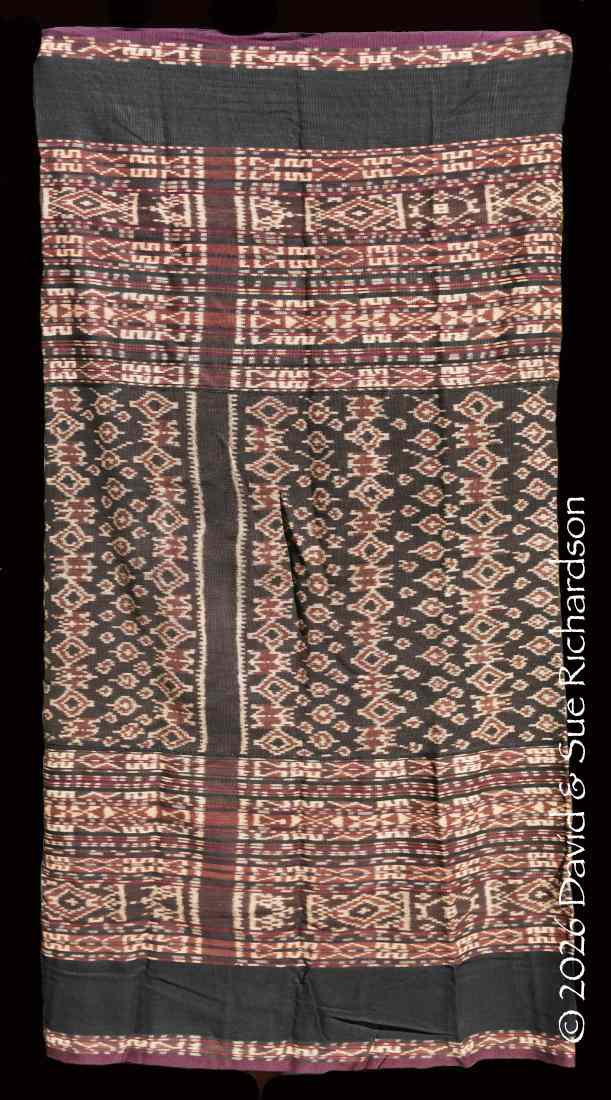

Wate senewaken are mostly two-panel tube skirts traditionally woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton, with each panel almost completely covered with narrow bands of ikat, apart from a plain morinda-dyed band close to each terminal end. They are mainly confined to Lamagute (formerly Atawatung), the hamlet from which they originated.

A very fine example was collected by Ernst Vatter when he visited Ilé Apé in June 1929. Unfortunately, he and his wife only spent a few days on Ilé Apé, staying at Waipukan in the southwest part of the peninsula. However, they did visit Atawatung, where he purchased his wate senewaken, which he described as a watek ohing [sic]. It had three panels, the middle panel being very narrow. Vatter noted that it was old and damaged, but very beautifully patterned. He described Atawatung as a 'pure' fishing village where fish were caught using a bow and arrow.

The three-panel wate senewaken collected from Atawatung in June 1929 by Ernst Vatter. 73cm x 188cm. Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt am Main

Gaining accurate information in the field about these textiles has been a difficult task. We have spent a lot of time on numerous visits, asking questions from a range of local people in both Lamagute and Napasabok, and have received a range of different explanations.

A good example is provided by the two-panel example from our collection shown below. The initial information we were given about this textile was that it was made by the late Nene Kewa Tuteo from Napasabok (formerly Mawa), about 60 years ago. We acquired it in 2015 from her 80-year-old granddaughter.

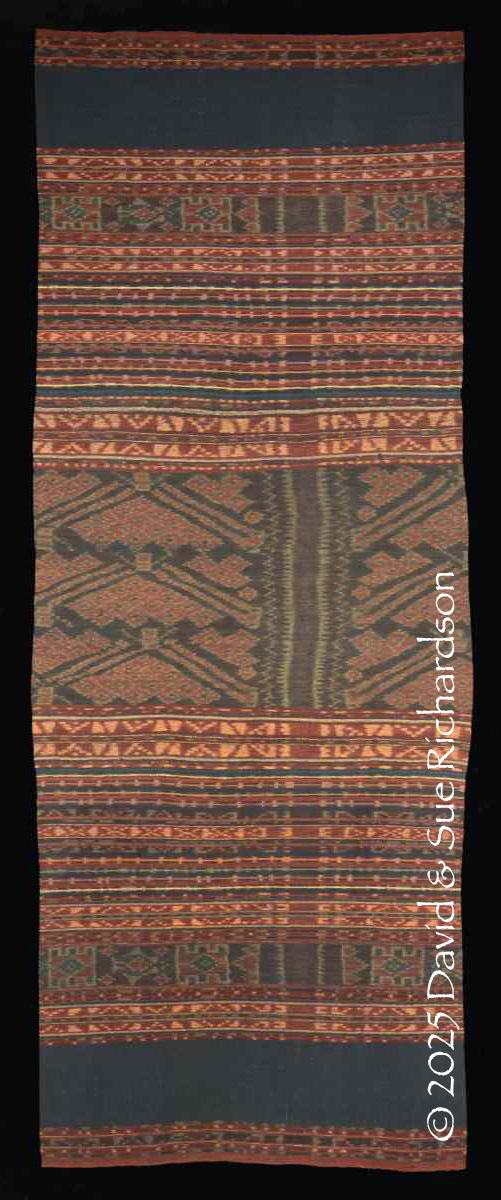

Wate senewaken possibly made around 1950 by the late Nene Kewa Tuteo from Napasabok

Richardson Collection

However, the weavers in Lamagute told us that it was made by Sawu Lewolein, the grandmother of master weaver Maria Sawu Betekeneng, who is the head of Kelompok Peten Ina. Maria was born in 1957, so this would make the sarong around 70 years old.

According to the kepala desa of Lamagute in 2019, Anwar Koli Witak from suku Witak, such sarongs were only made by women belonging to the clan suku Making. He claimed that the design was created by his grandmother, Deram Bisa Making, who died in 2016 aged around 80 to 90. Then other people from suku Making copied her design. He claimed that his type of sarong was only woven in Lamagute. The kepala desa said he had two of these made by Mama Deram. Deram’s daughter, Jari Laba from suku Making, was apparently still alive aged 102.

A wate senewaken from a private collection

Maria Sawu Betekeneng was taught to make a wate senewaken by her mother, Rosa Kedo Wato Witak, after she was married in 1980. Although her father belonged to suku Betekeneng, her mother came from suku Wato Witak. She was told by her grandmother that the wate senewaken design was created by a woman from suku Lango Tukan, which merged with suku Atawatung and is a subgroup of suku Blecker. María’s grandmother was one of three sisters, all of whom belonged to suku Lango Tukan. Her grandmother married into suku Witak, while her two sisters married into suku Betekenang. Only these two clans could make the senewaken from traditional materials.

According to local Lamagute weaver Augustina Tuto in 2025, such sarongs were known as wate senewaten not wate senewaken, the term senewaten having no particular meaning. She claimed that the first sarong of this type was made in Lamagute by Ema Jari Aman from suku Betekeneng and thereafter they could only be made and worn by women from suku Betekeneng. However, today they can be made by any experienced woman from any Lamagute clan. Because they require so much binding, they are beyond the capability of young weavers. Augustina Tuto showed us one of the panels from a new wate senewaten that she was in the process of making. It was made from synthetically dyed commercial cotton.

One panel of a wate senewaten being made by Augustina Tuto

Such sarongs can be worn at church for Christmas or Easter or for special adat ceremonies. They cannot be used for bridewealth - only the wate ohin can be used for that purpose. Today they are always made with two panels. They can also be made by experienced weavers in Napasabok, but they must first obtain permission from weavers in Lamagute.

Mama Retha Sabu, who was born in Lamagute in 1947 and belongs to the clan Atawatung, was taught to make a wate senewaken by her mother, who belonged to suku Betekeneng. She too confirmed that in the past, only weavers from suku Betekeneng could make and wear a wate senewaken. If somebody wants to make a senewaken today they must obtain permission from someone from the clan Betekeneng. Weavers in Napasabok confirmed to us that wate senewaken were mainly produced in Lamagute. They have occasionally been made in Napasabok, but only after obtaining permission from Lamagute.

A wate senewaken labelled a kewatek méan from the Yale Indo-Pacific Collection. It was initially collected by Kent Watters in the 1970s before being acquired by Tony Granucci.

To summarise, it seems likely that the wate senewaken originated within the aristocratic Betekenang clan and was initially restricted to members of that clan. It was clearly designed as a high-status item of clothing, not an alternative to the wate ohin. Only later did it become possible for other Lamagute clans to make and wear it, possibly beginning with suku Witak. Athough only two-panel versions are made today, it does seem that three-panel versions were made in the past.

Return to Top

Wate Tenépa

In the past many villages on Ilé Api produced an exclusive three-panel warp ikat sarong, which was known as a wate tenépa. Such sarongs were usually reserved for women of noble descent, or women who married into the nobility. They were worn for important ceremonies, such as a wedding or when the man’s clan presented the bridewealth elephant tusk to the prospective bride’s clan. However, despite being very high status, these sarongs could not be used for bridewealth exchange in marriage alliances.

The term tenépa is used widely by Lamaholot weavers to describe three-panel ikat sarongs. The name means ‘extension’ in the Lamaholot language (Barnes 1996, 209). It signifies that the normal two-panel sarong has been extended with an extra central panel.

Each village had its own design, which could only be made and worn by women from that village.

There are two types of wate tenépa: the tenépa méan, which is predominantly dyed with morinda, and the tenépa miten, which is predominantly dyed with indigo. The status of both types is the same. Generically they are both three-panel or wate berait rua sarongs – sarongs with two lateral seams.

Ruth Barnes reported that she had been informed that three-panel sarongs were used in the Ilé Apé region of Lembata, but could not obtain a description (Barnes 1989, 100). She could only identify one possible candidate as a three-panel Ilé Apé sarong, held in the collection of the Museum der Kulturen, Basel. She mysteriously concluded that this could not be a tenépa because the central panel was decorated with a patola-like pattern similar to the three-panel sarongs made in Lamalera and on Ata Déi.

Return to Top

Wate Tenépa Miten

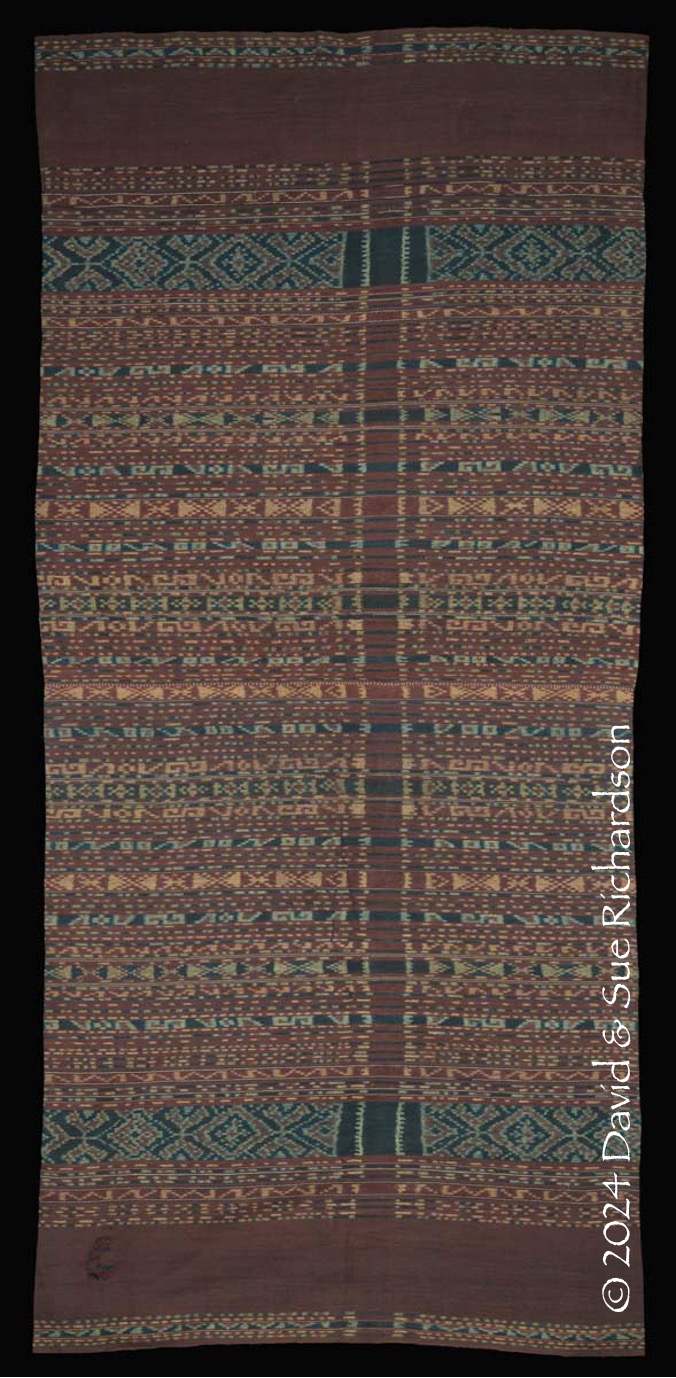

Wate tenépa miten are quite rare. All three panels are first dyed with indigo, and later with morinda. The end panels have plain broad bands coloured near black with indigo overdyed with morinda. This overdyeing is known as belapit.

The following example was woven in the 1930s or 1940s by the late Tenoa Lango Belen, who was from Lamawara (formerly Bungamuda) and belonged to suku Lango Belen. It was acquired from her granddaughter in Lamawara.

Tenoa married a man from the same village who also belonged to suku Lango Belen, but came from a different clan house. She died in 1976 in her 80s, so must have been born just before 1896.

The sarong has been woven from hand-spun cotton dyed with indigo, morinda and a cocktail of tannins to create black. In Lamawara the latter is made by boiling ground tamarind seed, powdered mangrove bark and the outer shells of the Java Olive or Wild Almond tree (Sterculia foetida), and then kneading this solution into yarns that have been very deeply dyed with indigo. The weft is indigo.

A wate tenépa miten made by Tenoa Lango Belen from Lamawara

Richardson Collection

The narrow central panel, known as the beleken, is decorated with alternating rectangles containing lattices of diamonds. The small diamond pattern is called mudaten, meaning orange leaf (muda means orange), while the large diamond pattern is bélewaten, béle meaning large and waten meaning liver or diamond.

The two outer panels have a main band of ikat (the inan or mother) decorated with two alternating motifs: a large hashtag-shaped double cross called mekangen (which means flying) and a small diamond sandwiched between half diamonds, also called mudaten (orange leaf). This is flanked by narrow ikat stripes called belekan inan, or inan protectors.

The outermost stripe is the semerengen, and it is decorated with the kebelepak or coconut leaf pattern.

Return to Top

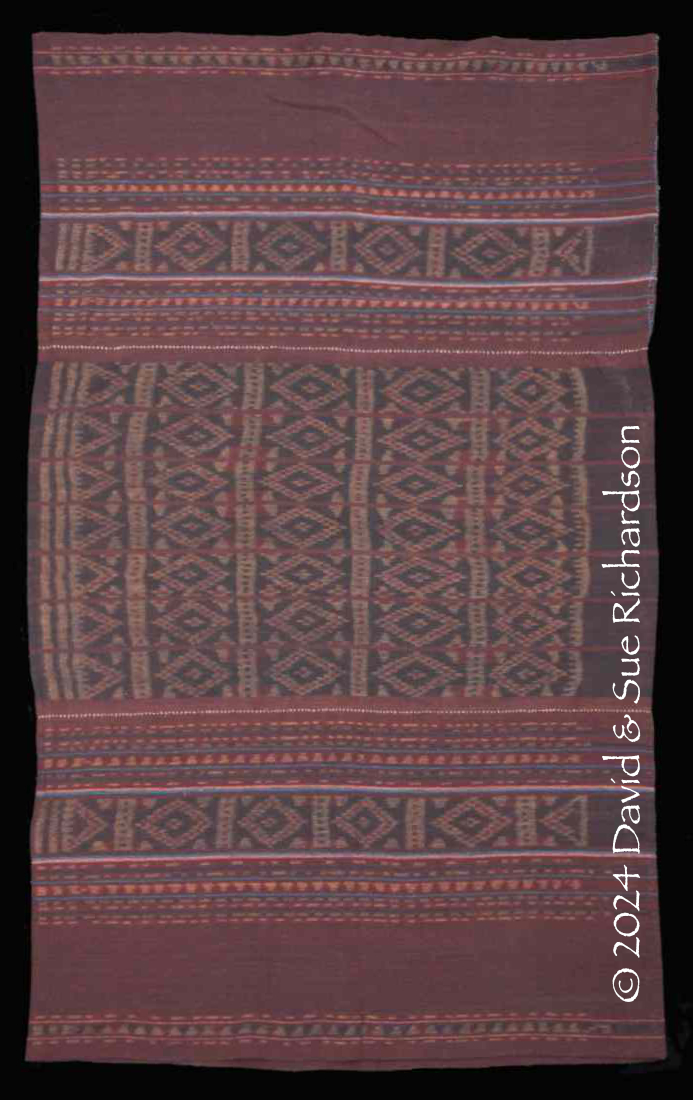

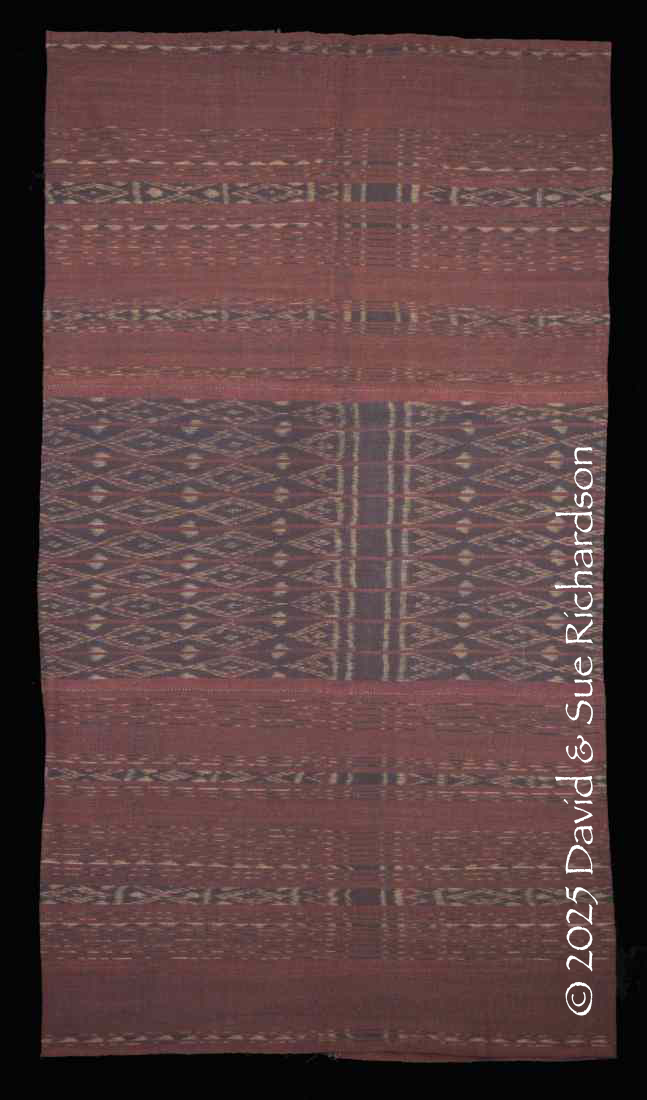

Wate Tenépa Méan

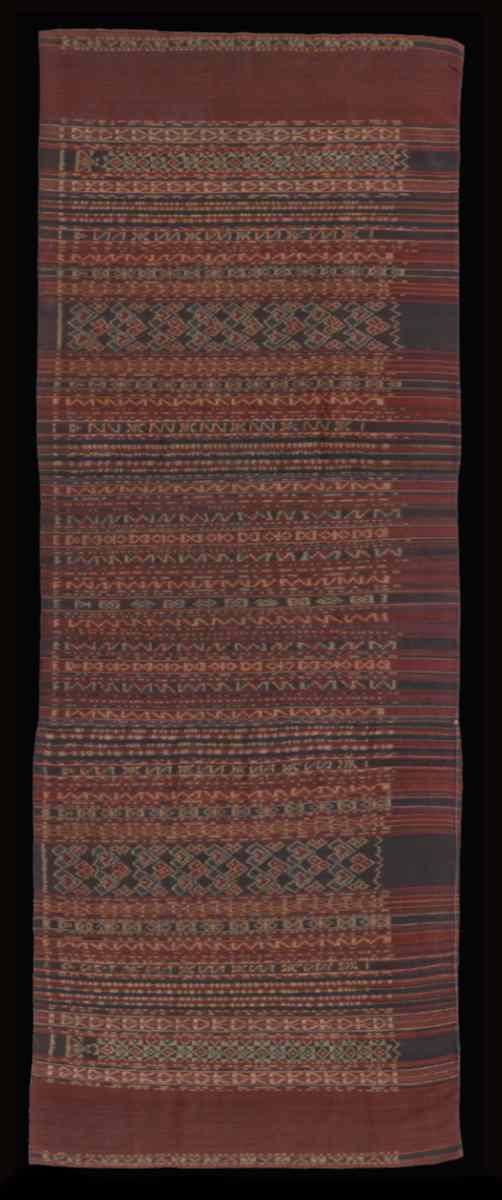

The majority of wate tenépa méan have a central panel decorated with a rectangular lattice of diamonds. Some central panels are only dyed with morinda, while others are dyed with indigo followed by morinda. The outer panels always terminate with a broad, plain band of morinda.

According to the weavers of Lamawara (formerly Bungamuda), every village in the region produced both two-panel (nai rua) and three-panel (nai telo) cloths, each village having its own specific style. This conclusion is supported by the existence of examples of wate tenépa from Lamawara, Lewotolok, Lamagute and Tokojaeng.

The weavers of Lamawara recounted to us the mythical story of the origin of the tenépa. A local village chief had a young daughter, who he offered up to his people for sacrifice. The villagers took the girl to a sacred location, but instead of sacrificing the girl they chose to sacrifice a buffalo. After the chief discovered what had happened, he became angry and swore to kill his daughter. When he summoned the young girl, she said she could not come now because she was weaving. When she finally appeared later, she was wearing her newly woven wate tenépa. The chief was so impressed that he decided not to kill his daughter but to issue a decree that this pattern should henceforth be restricted to his family.

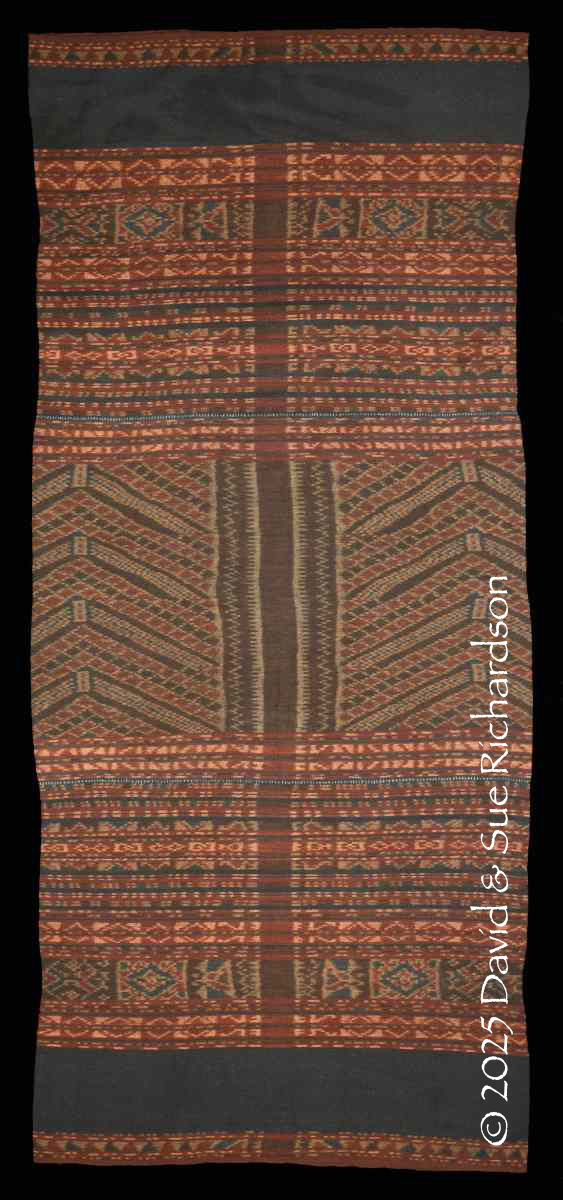

The first example of a wate tenépa méan shown below was made in 1956 by the late Lusia Dera Ola Wanganaing when she was just 19 years old. She was born in 1937 in Tokojaeng, on the northeast coast of Ilé Apé, and died in 2006. In 1970 she married Rafel Raing Tedemaking of suku Tedemaking from Laranwuntun (formerly Waipukang) on the southwest coast of Ilé Apé, and moved to her new husband’s village. Later they had two daughters. The sarong was acquired in Laranwuntun from the weaver’s eldest daughter, Mariana Abon Tedemaking, aged 48.

The central panel is patterned with two rectangular lattices filled with large spotted diamonds, as well as one column of half diamonds. The two identical end panels have a plain band of morinda and one further row of large diamonds, banded by narrow plain light blue and pink warp stripes. The latter is flanked by clusters of narrow stripes decorated with simple warp ikat. The outer edges of the end panels terminate with a narrow band of yet more warp ikat stripes.

A wate tenépa méan made by the late Lusia Dera Ola Wanganaing from Tokojaeng

Richardson Collection

The second example was made by Margareta Bui Purab from suku Purab, who was born in Lewotolok on the northwest coast of Ilé Apé in 1960. However, the hand-spun yarns were bound and dyed by her grandmother, Kidi Belae from suku Niha Making, who was born in 1894 and died in 1989 at the age of 95. She produced the yarns in 1951 when she was aged 57.

Margareta Bui Purab started weaving when she was 11-years-old and made this sarong when she was just 20-years-old. She later married a man from Lamawara (formerly Bungamuda) and relocated to his village.

The yarns were pre-dyed before binding with mango bark. All of the indigo in the warps has been overdyed with morinda. According to Margareta Bui, the yarns required fifteen separate morinda immersions.

The central panel is patterned with two rectangular lattices filled with large spotted diamonds, along with a single column of simple half-diamonds. The lattices are separated by two pairs of plain vertical tramlines.

The end panels are almost completely filled with a cluster of narrow, ikatted and plain warp stripes and bands, apart from one outer plain band of morinda – the howin (pron. hovin). The ikat stripes and bands are decorated with simple geometric motifs, the largest being triangles, diamonds and diagonal crosses.

A wate tenépa méan made by Margareta Bui Purab in Lewotolok

Richardson Collection

The next example was made in 1978 by Yuliana Perada (Mama Yuli) from Lamawara. She was born in 1955 and has three children – two boys and one girl. Her husband died in 2018 and in 2021 she lost her home as a result of the volcanic eruption of Ilé Apé followed by heavy rain that caused a flood and a landslide. She was therefore relocated to a small house built by a local NGO. She decided to sell her wate tenépa because she needed some money to pay for her youngest son’s university tuition and to support her daily needs.

Her tubeskirt is woven from hand-spun cotton that have been richly dyed with indigo and morinda, the warp singles having first been pre-dyed with boiled mango bark. The coarser weft was deeply dyed with indigo. She told us there was an adat requirement that before undertaking the dyeing, the weaver must first chew betel nut.

According to Mama Yuli, the indigo dyeing was repeated thirty times until the desired near-black colour was obtained. At each stage the bound yarns were immersed in the indigo mixed with lime powder for about three days and were then removed and fully dried.

Before dyeing the yarns with morinda, they were first oiled by soaking them in a mix of crushed candlenut and cold water for about ten days, then drying them in the sun for a month until the candlenut oil fully soaked into the threads. They were then dyed with crushed morinda bark soaked in cold water and mixed with pounded kokaw (the dried bark of the Symplocos tree, obtained from Alor). Mama Yuli claimed that this was repeated about an incredible sixty times, until she obtained the desired colour.

The wate tenépa méan made by Yuliana Perada from Lamawara

Richardson Collection

The central panel has eight bands decorated with rows of diamonds that are separated by narrow plain bands of morinda.

The end panels have a symmetrically arranged cluster of narrow bands, with simple ikat bands alternating with morinda bands. The wider central band has a row of geometrical motifs, diamonds alternating with x-shaped crosses.

The final example of a wate tenépa méan was woven more recently in 2019 by Mama Julie Tenoa, the head of the local weaving group in Lamawara. However, the ikatted hand-spun cotton warps were considerably older, having been bound by Julie’s mother, Veronika Wona, who died in 2009, aged over 70. Unfortunately, Julie did not know when her mother ikatted the yarns - when she was a young girl, or after she was married and was living with her husband in Malaysia.

The hand-spun cotton warps has been pre-dyed with mango bark and then dyed with indigo followed by morinda, the coarser weft having only been dyed with indigo. All three panels have a continuous warp, the 15cm-wide section of unwoven warps being positioned at the back of the skirt.

A wate tenépa méan made by Julie Tenoa in Lamawara

Richardson Collection

The central panel is patterned with two rectangular lattices filled with large diamonds and half-diamonds. The lattices are separated by a pair of simple vertical tramlines.

The outer panels have three separate bands of plain morinda, separated by clusters of ikatted and plain warp stripes. These vary in width from narrow to wide, the widest containing a central band decorated with alternating diamonds and diagonal crosses.

Return to Top

The Wate Tenépa of Lamagute

The women of Lamagute (formerly Atawatung) make two unique types of wate tenépa, one being much more popular than the other.

In the past wate tenépa could only be made in Lamagute by women from the highest status Betekeneng suku or clan or by women marrying into that clan. According to the wife of the kepala desa of Lamagute (Anwar Koli Witak from suku Witak), they can only be woven within Lamagute. If a woman marries outside of the village she loses the right to weave the wate tenépa, although if she already has one she can take it with her.

Today wate tenépa can be woven by all seven of the local Lamagute clans – Betekeneng, Witak, Watun, Mamik, Making, Berwulo, and Bleker. This is because in the 1920s the number of Betekeneng weavers had become so low that they were fearful that their tradition would become extinct. They therefore decided to allow all of the other clans to weave the wate tenépa to keep the pattern alive. However the proviso is that a weaver from one of the other clans cannot make one without obtaining the permission of the Betekeneng suku. If they do so without authorisation, they believe the textiles will be fragile and will break. Women from the neighbouring villages of Napasabok and Waimatan are not allowed to weave such tenépa.

There are currently 40-50 weavers in Lamagute, many belonging to two local weaving groups – Kelompok Peten Ina (Remember Mother), with 21 members led by Maria Sawa Betekeneng, and Kelompok Mekar Sari (Blooming Flower), with just 7 members led by Margarita Kewa Betekeneng. However less than ten of these 28 weavers can weave a wate tenépa. Of these Margaretha Jawa Betekeneng is considered the best.

As with the wate tenépa made in other Ilé Apé villages, these wate tenépa are high status ceremonial sarongs that can be worn for adat ceremonies or for weddings or the welcoming of guests. Any woman can wear one, whether young or old, married or unmarried.

As a rule, they are not used for bridewealth (belis). However in 2004 we were told by Margareta, who ran a local Lamagute homestay, that certain people could use the wate tenépa for belis. Local women informed us that the standard amount for a counter prestation consists of one wate ohine, one wate hebak, one synthetically dyed wate krokan and 5 ivory bracelets. In some cases, more textiles are included.

There are two types of wate tenépa – the wate tenépa blaun, which is a floral design, and the wate tenépa lakedowak, which means steps. In the latter case, the pattern in the central panel is called naga, representing the pattern of the naga’s skin.

Return to Top

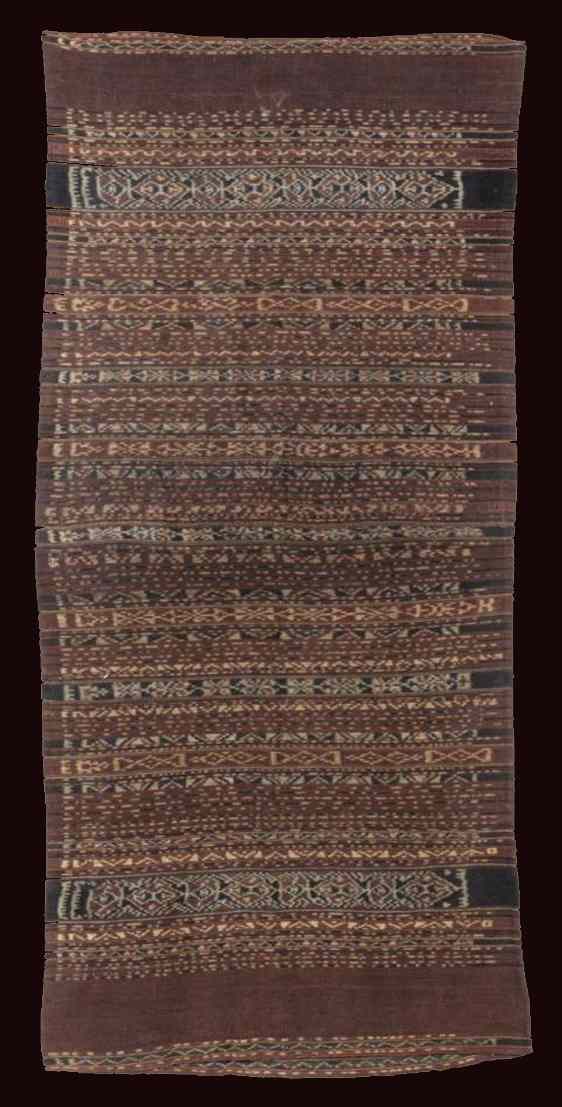

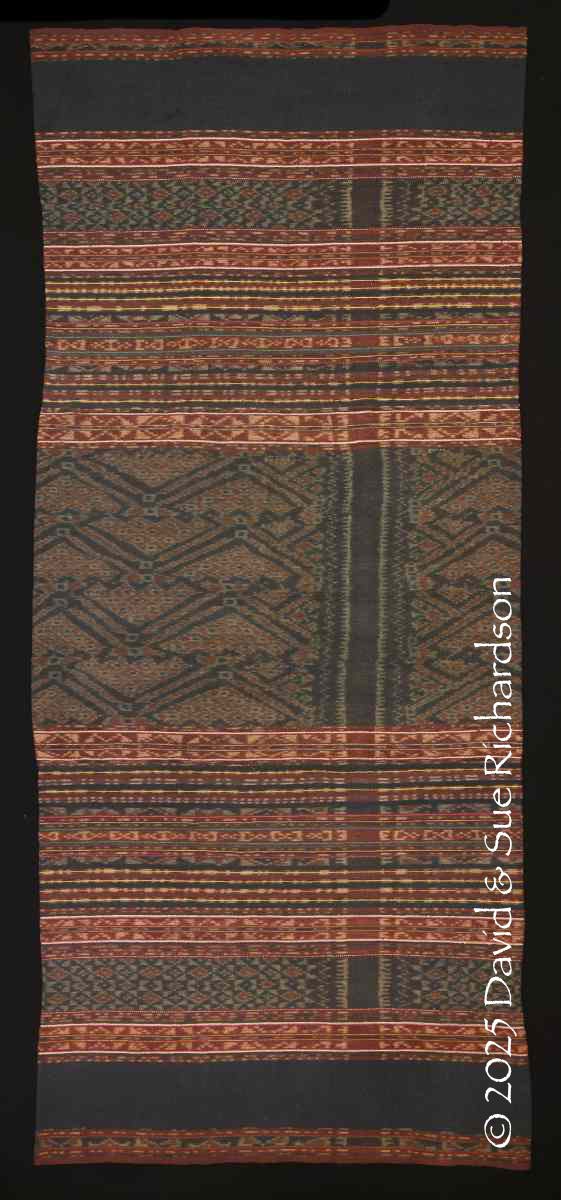

Wate Tenépa Lakedowak

The wate tenépa lakedowak (or lake dowa or lake dowak) has a middle panel decorated with the so-called naga or lakedowak pattern consisting of columns of large chevrons, separated by chevron-shaped bands of tiny light- and dark-brown diamonds. Some Lamagute weavers say that lakedowak is a term that cannot be translated, while others say it means steps.

We photographed the first example of a wate tenépa lakedowak in Lamagute in 2004. It was made in 1960 by a grandmother as a gift for the marriage of her daughter.

A wate tenépa lakedowak made in Lamagute in 1960

The second example shown below was made in the 1990s by Paulina Pasa, the mother of a previous kepala desa of Lamagute, Kristoforus Nimanuho. She was born in Lamagute, but moved to Napasabok (Mawa) after she married a man from that village. She belonged to suku Mamik.

The wate tenépa lakedowak made by Paulina Pasa. Richardson Collection

There are local beliefs about the origin of the naga pattern. In one of them, a weaver fell asleep at her loom. A snake appeared and continued with her weaving while she remained asleep, naturally producing a snakeskin pattern. Exactly the same thing happened many years later with her daughter and then later again with her granddaughter. Because of this they were the first family to introduce the naga pattern.

In another story, a long time ago a woman was spinning under the full moon when she saw a naga snake in the sky. She therefore decided to copy the same pattern in her cloth.

Above: A wate tenépa lakedowak displayed in Lamagute in 2004

Below: A wate tenépa lakedowak displayed in Napasabok in 2024

Snakes and nagas play a part in many myths recounted by the people of eastern Indonesia. On Alor, carved nagas were erected at the entrance to villages to protect the inhabitants from harm. Women in Watowara, in Kecamatan Titehena, East Flores, told us a legend about a girl from kampong Kroko Pukang (the Lapan Batan Islands) who fell in love with a big snake. The snake came to her in her dreams and told her to weave a snakeskin pattern. The snake then came and lay beside her so that she could bind the pattern of the snake’s skin into her yarns.

The following wate tenépa lakedowak was made in the mid-1950s by the late Deram Bisa in Lamagute. It was acquired in Napasabok from her granddaughter, Agnes Agong Witak, who was born in 1960.

The wate tenépa lakedowak made by Deram Bisa. Richardson Collection

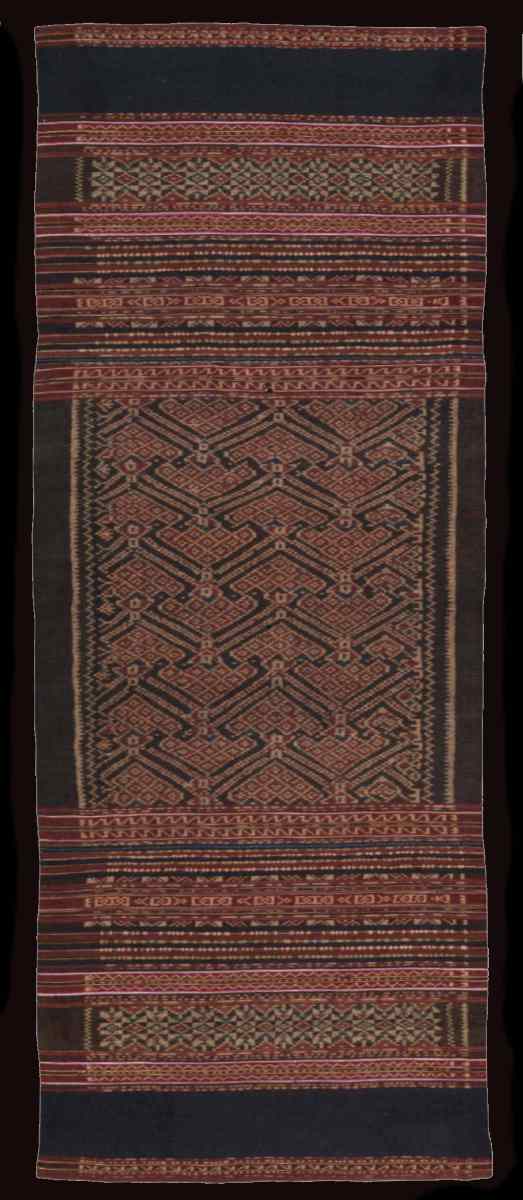

The next wate tenépa lakedowak was woven by Margaretha Jawa Betekeneng, known locally as Mama Retha, at her home in the eastern part of Lamagute. She began making it during the 1980s and finished in the early 2000s. However, the drop spinning of the cotton yarn and the binding and dyeing of the threads had already been completed many years previously by her mother. Mama Retha was born in Lamagute in 1954 into the noble clan of suku Betekeneng. She is very religious and belongs to the local Catholic group at the nearby Gereja Santa Maria Perantara (Church of St. Mary the Mediator). The local weaving groups consider Mama Retha as the most accomplished of all of the women who are able to make a wate tenépa lakedowak.

The wate tenépa lakedowak woven by Margaretha Jawa Betekeneng. Richardson Collection

Our final example was collected by Augustus Flick and is now in the collection of Thomas Murray. It has (in our opinion) been erroneously described as a bridewealth sarong from southern Lembata – either a kewatek nai telo from Lamalera or a petak haren from Ata Déi. Sadly, a previous misguided owner had cut the vertical seam in order to display both sides of the tubeskirt at the same time.

A wate tenépa lakedowak from the Thomas Murray Collection

Return to Top

Wate Tenépa Blaun

Wate tenépa blaun appear to be quite rare. Indeed, we have never seen a complete traditional sarong of this type. However, the weavers in Lamagute have shown us the central section of an old example, which they describe as being decorated with a bunga or flower motif. This particular middle section is made from two very narrow panels joined selvedge to selvedge, so the original sarong will have had four panels.

A weaver in Lamagute displaying the two narrow centre panels of a wate tenépa blaun.

Maria Sabu Betekeneng, the head of Kelompok Peten Ina, kindly showed us a wate tenépa blaun made by her mother, Rosa Kedo Wato Witak. The specific design belonged to her grandmother and today was restricted to Maria and her sisters.

A wate tenépa blaun made by Rosa Kedo Wato Witak.

Return to Top

Wate Nai Pa

We know of only one complete example of a wate nai pa or four-panel wate. It belongs to three sisters – Mama Monika Kihan Making, the eldest sister, Mama Agnes Dai Making, the middle sister, and Mama Berlina Lopot Making, the youngest sister. They all belong to suku Lopot Making and live in Napasabok. Their sarong was made by their great grandmother and has been passed down over four generations. By tradition the sarong should have been passed down from the mother to the youngest son. Having no brothers, the three sisters inherited it from their father, who was the youngest of their grandmother’s sons. Because the current owners are all childless, the sarong will eventually go to the son of their uncle (their cousin).

Mama Agnes photographed in 2004 wearing the wate nai pa

The people of Napasabok and Bungamuda belong to two socially stratified tribes: the higher status Beloloken tribe and the lower status Lereken tribe.

The Beloloken clans are: Wao Langun, Lemanuk, Koli Making, Niha Making, Belaon Making, Lopot Making and Laper Making. The Wao Langun and Lemanuk clans have a higher social stratification than the Laper Making, Niha Making and Lopot Making clans, holding the position of Belen Raya (village leaders). The Niha Making clan fulfil the role of village protector.

The Lereken clans are: Hurek Making, Lamarongan, Paokuma, Nimanuho, Balawala, Laga Making, and Lado Purab.

Ownership of this sarong has been both a privilege and a curse for the three sisters. Because it is so valuable, no man has been wealthy enough to afford the bridewealth required to marry any one of them. Consequently, they have spent all of their lives as spinsters.

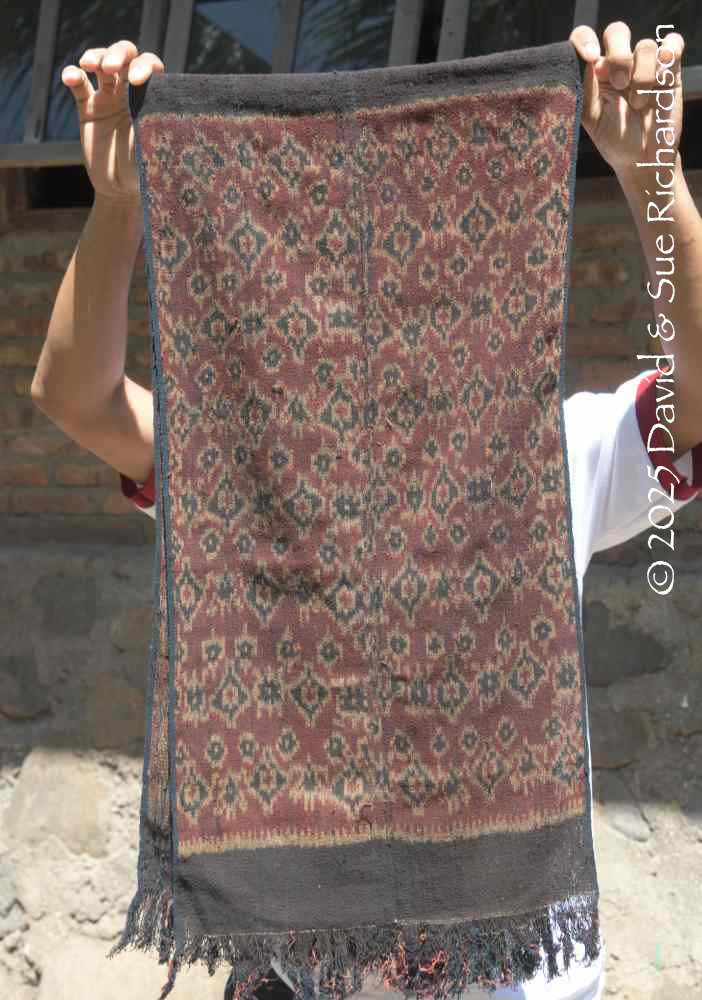

Above and below: On several occasions, local villagers have held up the complete wate nai pa for us to view

Above: Details of the rows of geometric motifs

Below: The folded wate nai pa photographed in 2016, displaying some of the geometric motifs

The diamond-shaped motifs are called muda lolon, meaning orange leaf.

The sisters describe the sarong as a wate ara bora, meaning snake pattern sarong. Villagers believe the pattern of this ikat was woven by a snake. Robert Barnes found that in the neighbouring region of Kedang, the term ara bora refers to a mythical sea monster (Barnes 2013, 72).

This very high-status sarong is worn for a wedding, a big mass or for welcoming important visitors.

Above: Mama Agnes singing a local melody in 2018 dressed in the wate nai pa.

Below: Sue with Mama Monika in 2015 with her wate nai pa draped around her shoulders.

Return to Top

Kewodu

The kewodu was a traditional man’s handspun sarong that was predominantly white, and decorated with brown and black checks. They are rarely made today.

The same term is also used for a man’s white sarong on Adonara, more completely described as a kewatek kiwane kewodu.

Nowing and Senawe

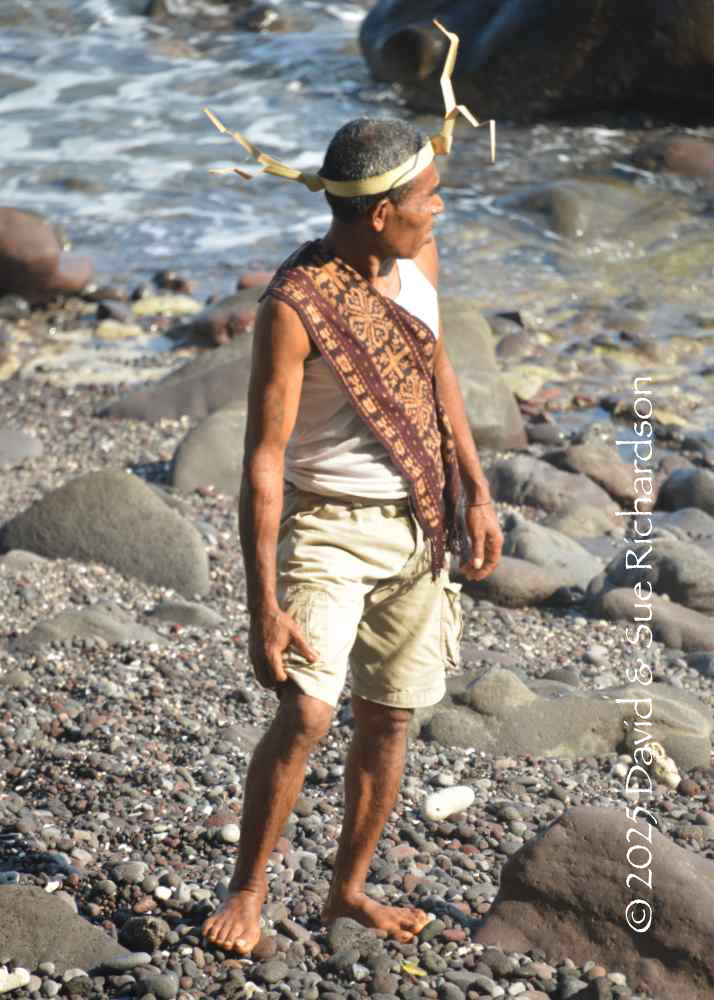

The most common man’s sarong is dark-coloured, with very narrow warp stripes. On the north coast of Ilé Apé - from Lewotolok to Lamagute, Ebak and Tokojaeng – these are called nowing, but in southern Ilé Apé – from Batuntawa (formerly Riangbao) to Watodiri and Jontona – they are called senawe. The term senawe is also used in southwest Solor.

The first example of a nowing was made by the late Paulina Lingin in Napasabok (formerly Mawa), who died in 1991. It was acquired from her daughter, Berlinda, in 2016. She informed us that her mother made this sarong when she was only a child. At that time Berlinda was about 60 years old, suggesting that this nowing was woven around 1965.

The two-panel nowing was woven from very finely handspun cotton, that had been naturally dyed with indigo, morinda and a natural yellow dye – possibly kayu kuning. Each identical panel was woven with very narrow alternating indigo and morinda warp stripes, regularly interspersed with a pair of single yellow warps. The wefts are dark indigo.

The nowing made by the late Paulina Lingin in Napasabok

Richardson Collection

The second handspun nowing that belonged to a resident of Napasabok has a more pronounced warp-striped decoration.

A handspun nowing hung on a washing line in Napasabok

The following two examples belong to the collection of Yayasan Solidaritas Sedon Senarew Lamaholot (the Lamaholot Sedon Senaren Solidarity Foundation) based in Lewoleba. The first is made from naturally dyed handspun cotton, while the second is made from synthetically dyed commercial cotton.

Above: A bold-striped nowing from a collection in Lewoleba

Below: A modern chemically-dyed nowing from the same collection

The latter types are still widely worn for ceremonial occasions, such as at this welcoming ceremony in Napasabok. The nowing is held in place by a belt or waist sash and the top is folded down on the outside, having the appearance of an apron.

Modern nowing worn by Vitalis Nimanuho and the Village Secretary at a welcoming ceremony in Napasabok

Return to Top

Senai

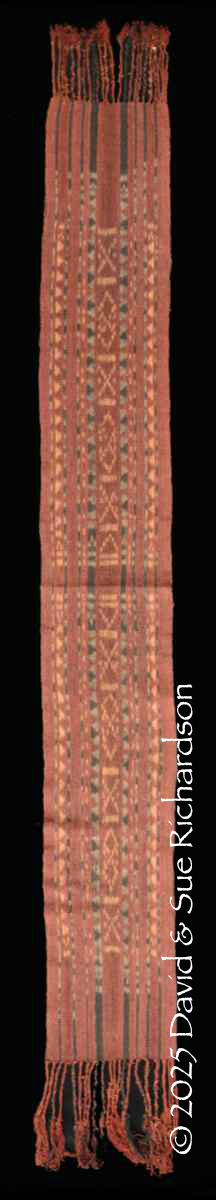

A warp ikat shoulder cloth is known as a senai and is mainly worn across the chest but can also be hung around the neck. Traditionally, men wear their shoulder cloths over their left shoulder and women wear them over their right shoulder.

Today these are always one-panel and are decorated with a central band of ikat flanked by narrower bands of ikat.

Above: A modern senai worn in Napasabok by the lord of the land, Bapak Nadus Bada Lapermaking. Below: Another moden senai worn in Napasabok.

The narrow handspun senai shown below was woven in 2014 by master weaver Yuliana Tenoa, the head of the Lamawara weaving group. The pattern is a copy from the outer decorative bands of a ceremonial wate hebaken tube-skirt.

The senai woven by Yuliana Tenoa in Lamawara

Return to Top

The Influence of Indian Patola

The influence of patola motifs on local Lembata textile design is undeniable, as evidenced by this kewatek nai telo from Lamalera in the collection of the Museum der Kulturen, Basel, acquired at some time prior to 1950. The elephant motifs are remarkably similar to those found on the most prestigious types of silk Gujarati patola.

Patolu with elephants. Collection of the Museum der Kulturen, Basel.

The kewatek sarongs of Lamalera show the strongest link to Indian patola. The type of three-panel kewatek nai telo decorated with the diamond-shaped motif known as taru mata was clearly influenced by the small export patolu classified by Bühler and Fischer as motif type 25.

Above: The taru mata motif on a kewatek collected prior to 1950. Museum der Kulturen, Basel. Below: A small export patolu with motif type 25. Richardson Collection.

This type of patolu was probably only rarely used in India, since its dimensions in no way correspond to Indian requirements. According to Bühler and Fischer, such items are ‘mostly quite carelessly worked export goods’ (1979, vol. 1, 106). Ruth Barnes found an identical patolu in Lamalera, locally called a ketipa, belonging to the clan Lelaona (1989, illustration 31).

Another Lamalera kewatek motif called ketipa is octagonal and has a loose connection to the chhabadi bhat or flower basket motif found on export patola with the motif type 11e design. This was one of the most common types of patola to be exported to the Indonesian archipelago.

On the nearby Ata Déi peninsula some clans do have treasured imitation patola in their clan houses. However, it is more difficult to find any link to patola patterns among the textiles made in this region.

Treasured heirlooms - elephant tusks and a badly damaged roller-printed cotton cloth – in a clan house at Watowawer, Ata Déi

While some of the ikat textiles made in Lamalera have clearly been influenced by the motifs found on certain double ikat silk patolu from Gujarat, it has been claimed that those of Ilé Apé have not. In discussing the textiles of Ilé Apé, Ruth Barnes (1984, 215) made the following observations:

There is very little trace of patola influences. One single geometric pattern, the rhombic shape close to the petolã (sic) of Lamalera, may certainly have its source in the Indian double ikat cloths, but there is no attempt otherwise to evoke the appearance of the high-status imported cloths, as is so evidently the case in southern Lembata.

Patola influences are primarily found in the central panels of the three-panel bridewealth sarongs from Lamalera. The unusual feature of Ilé Apé bridewealth sarongs is that they only have two-panels, just like those found in East Flores and on Solor and Adonara. Ruth Barnes was not really aware that in the past, and even today, the women of Ilé Apé made three-panel sarongs, called tenépa (Barnes 1989, 100). Most Ilé Apé tenépa either have centre panels with simple diagonal lattice designs or with a naga-inspired pattern, neither of which show any link to Indian patola.

However, the centre panels of both the wate tenépa miten and the wate tenépa blaun do have motifs with a resemblance to the Gujarati chhabadi bhat or flower basket motif:

Above: A detail from the centre panel of a wate tenépa miten

Below: The two-panel centre of a wate tenépa blaun

The lattice of flower basket motifs on an export chhabadi bhat patola.

Richardson Collection.

It therefore seems that Gujarati patola have had some limited influence on Ilé Apé textiles, although not on the most common types of textiles produced in that region.

Return to Top

Bibliography

Albo, Franscico, 1874. Extracts from a Derrotero or Log-Book of the Voyage of Fernando de Magellanes in Search of the Strait, from the Cape of St. Augustin, Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Anon, 1956. Fundaçâo das Primeiras Cristanades nas Ilhas de Solor e Timor, pp. 475-

Documentação para a história das missões do padroado português do Oriente: 1568-1579, vol. 4, Basílio de Sá, Artur (ed.), Agência Geral do Ultramar, Divisão de Publicações e Biblioteca, Lisbon.

Ansar, Majid, 2018. Belis gading gajah tradisi perkawinan masyarakat Lamaholot di Ile Ape Kabupaten Lembata Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Timur, S1 Thesis, University of Makassar.

Ataladjar, Thomas B., 2015. Pai Hone Tala Ia, Pai Wane Tele Pia, Lame Lusi Lako dari Tanah Nubanara Menuju Tanah Misi, Koker, Jakarta.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Lembata, 2018. Kabupaten Lembata Dalam Angka, Lewoleba.

Barbosa, Duarte, 1866. A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the beginning of the Sixteenth Century, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Barnes, R. H., 1977. Alliance and Categories in Wailolong, East Flores, Sociologus, New Series, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 133-157.

Barnes, R. H., 1979. Lord, Ancestor and Afine: An Austronesian Relationship Name, NUSA, vol. 7, pp. 19-34,

Barnes, Robert. 1982. The Majapahit dependency Galiyao, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, vol. 138, pp. 407–412, Leiden.

Barnes, Robert Harrison, 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Barnes, R. H., and Samely, U. B., 2013. A Dictionary of the Kedang Language, Brill, Leiden and Boston.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989a. The Ikat textiles of Lamalera: a study of an Eastern Indonesian weaving tradition, E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Barnes, Ruth, 1989b. 'The Bridewealth Cloth of Lamalera, Lembata', in To Speak With Cloth: Studies in Indonesian Textiles, Gittinger, Mattiebelle, (ed.), University of California, Los Angeles.

Barnes, Ruth, 1991a. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 2, pp.95–112.

Barnes, Ruth, 1994. “Without Cloth We Cannot Marry”: The Textiles of the Lamaholot in Transition, Fragile Traditions: Indonesian Art in Jeopardy, University of Hawaii Press.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010a. Woman’s Tubular Skirt: Porso Toraja Region, Sulawesi, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 254-255, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Barnes, Ruth, 2010b. Woman’s Bridewealth Tubular Skirt, watek ohing Ili Api, Lembata, Five Centuries of Indonesian Textiles: The Mary Hunt Kahlenberg Collection, pp. 346-347, Delmonico Books, Munich.

Beckering, J. D. H., 1911. Beschrijving der eilanden Adonara en Lomblem, behoorende tot de Solor-Groep, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2e Série, vol. 28, pp. 167-202.

Bolland, Rita, 1977. Weaving the Pinatikan, a warp-patterned Kain Bentenan from North Celebes , Studies in textile history : in memory of Harold B. Burnham, pp. 1-17, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Bühler, Alfred, 1959. Patola influences in Southeast Asia, Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. 4, pp. 4–46.

Donselaar, W. M., 1882. De Christelijke zending in de residentie Timor, Mededeeling van mege het Nederlandsche Zendinggenootschap, vol. 21, pp. 269-89, Rotterdam.

Duggan, Geneviève, 2015. Tracing Ancient Networks; Linguistic, Hand-woven Cloths and Looms in Eastern Indonesia, Ancient Silk Trade Routes, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte, Ltd., Singapore.pp. 53-

Fricke, Hanna, 2017. Nouns and pronouns in Central Lembata Lamaholot (Austronesian, Indonesia), Wacana, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 746-771.

Fricke, Hanna and Klamer, Marian, 2018. Reconstructing Linguistic and Social Histories of the Lamaholot region, Seventh 7th East Nusantara Conference, Kupang.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2019. Traces of language contact: The Flores-Lembata languages in eastern Indonesia, Ph. D. Thesis, Leiden University.

Fricke, Hanna Lotte Anneliese, 2020. Personal communication.

Gittinger, Mattiebelle, 1982, 45. Master Dyers to the World, Textile Museum, Washington DC.

Grangé, Phillipe, 2015. The Lamaholot dialect chain (East Flores, Indonesia), Language Change in Austronesian languages, Asia-Pacific Linguistics, Canberra.

Guy, John, 1998. Woven Cargos: Indian Textiles in the East, Thames and Hudson, London.

Hudjashov, Georgi; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Lawson, Daniel J.; Downey, Sean; Savina, Olga; Sudoyo, Herawati; Lansing, J. Stephen; Hammer, Michael F. and Cox, Murray P., 2017. Complex Patterns of Admixture across the Indonesian Archipelago, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 2439–2452, Oxford University Press.

Hull, Geoffrey, 1998. The Basic Lexical Affinities of Timor’s Austronesian Languages: A Preliminary Investigation, Studies in Languages and Cultures of East Timor, vol. 1, pp. 97-174, University of Western Sydney, Macarthur.

Hull, Geoffrey, 2006. Timorese Plant Names and their Origins, Monografias do Instituto Nacional de Linguōstica (Timor-Leste), no. 1, Instituto Nacional de LinguÌstica.

Irwin, John, 1955. Indian textile trade in the seventeenth century: 1. Western India, The Journal of Indian Textile History, vol. 1, pp. 15-44, Ahmedabad.

Keraf, Gregorius, 1978. https://lexirumah.model-ling.eu/lexirumah/languages/lama1277-ileap

Kleiweg, J. P., 1931. Quelques crânes de l’île Lomblen (Archipel Indien), Anthropologie, vols 9-10, pp. 129-143.

Lianurat, Antonius Buga, (Antoni Lebuan), Head of Culture, Lembata Culture and Tourism Office, 2013 – 2020. Personal communications and translations.

Lundberg, Anita, 2003. Voyage of the Ancestors, Cultural Geographies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 64-83.

Melalatoa, Junus, 1995. Ensiklopedi Suku Bangsa di Indonesia Jilid L-Z, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Michels, Marc, 2017. Western Lamaholot: A cross-dialectal grammar sketch, MA Thesis, University of Leiden.

Nagaya, Naonori, 2011. The Lamaholot Language of Eastern Indonesia, Doctoral Thesis, Rice University, Houston, Texas.

Ndate, Aloysius Sato, 2022. Sai Miu? Ata Nggela Lio-Ende, Penerbit, Ledalero, Maumere, Flores.

Pires, Tomé, 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, vol. 1, The Hakluyt Society, London.

Prakash, Om, 2009. Indian Textiles in the Indian Ocean Trade In the Early Modern Period, The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1984. Clothing, Ritual and Society in Tenganan Pegeringsingan (Bali), Verhandlungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Basel, vol. 95, pp. 191-241.

Ramseyer, Urs, 1991. Balinese Textiles, British Museum Press, London.

Rutan, Margarita I. M.; Daga, Lukas Lebi and Wutun, Monika, 2018. Studi Etnografi Makna Komunikasi Ritual Adat Werung Lolong pada Masyarakat Lewohala di Desa Todanara, Kecamatan Ile Api, Kabupaten Lembata, Provinsi Nusa Tenggarah Timur, pp. 1149-1163,

Schoutens, Wouter, 1676. Oost-Indische Voyagie, Jacob van Meurs and Johannes van Someren, Amsterdam.

Siebert, Lee; Simkin, Tom, and Kimberly, Paul, 2010. Volcanoes of the World, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Sumber Group Orang Baopukang, 2015. Sejarah Kampung Adat Lewohala, Kompasiana 25 June 2015: https://www.kompasiana.com/sandro.wangak/550b24cd813311df78b1e503/sejarah-kampung-adat-lewohala

Ten Kate, H. F. C., 1894. Een en ander over anthropologische problemen in Insulinde en Polynesië, Feestbundel aangeboden aan Dr. P. J. Veth, Leiden.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 1 February 2025.