Asian Textile Studies

Contents

Introduction

Geography

Captain Beckering’s Visit in 1910

Ernst Vatter’s Visit in 1929

Linguistics

Ethnography

Bibliography

Introduction

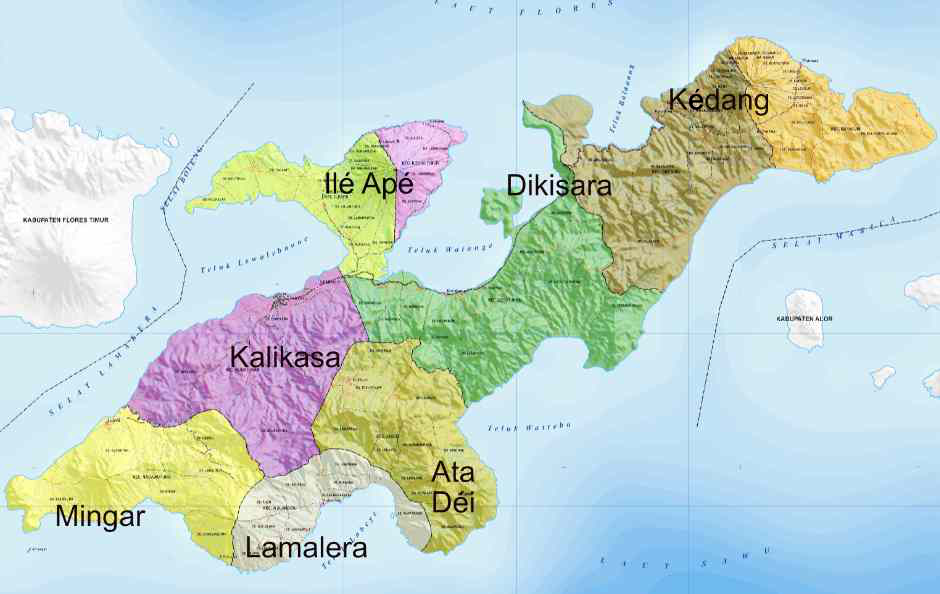

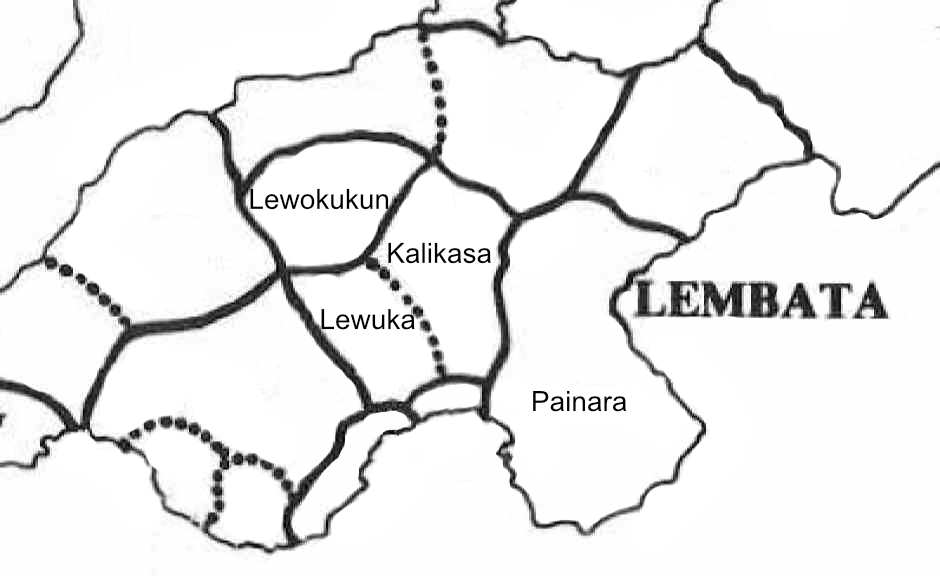

Ata Déi is one of the seven textile producing regions on Lembata Island, the other six being Ilé Apé, Kalikasa, Mingar, Lamalera, Dikisara and Kédang. Each of these has its own distinctive style, Ata Déi being renowned for its heavy three- and five-panel sarongs that are woven from naturally dyed hand-spun cotton.

The seven textile producing regions of Lembata Island shown on a map of the nine districts (kecamatan) of Lembata Regency (Kabupaten)

We collected our first Ata Déi sarong on Lembata Island in 1991, but did not return again until 2004, hiring an open backed ten-ton truck in Lewoleba to cope with the four-hour drive over the dreadful unmetalled road to Lerek. In 2013 we visited the peninsula in a tena whaling boat, sailing from Lamalera with the intention of landing at Dulir. However, the heavy south coast swell and the rocky shoreline meant this was impossible. With some difficulties our experienced crew managed to land us at Mulandoro during the morning high tide, but when we attempted to leave that evening at low tide, an exposed previously hidden reef made it impossible for us to return to our boat. The villagers telephoned friends in Labala who dispatched some young lads to pick us up on motorcycles and take us back to Lamalera.

Heading towards Ata Déi in 2013

Our most recent visits were in 2017 when we spent time in Watuwawer, in 2018 when we explored the village of Atawolo and in 2025 when we visited Waiwejak and returned to Watuwawer. Fortunately, the quality of the road has been steadily improving in recent years and today the journey from Lewoleba takes less than two hours.

Return to Top

Geography

The Ata Déi Peninsula, sometimes referred to as the Lerek Peninsula, is located on the southern coast of Lembata Island. The southern half of the peninsula is of ancient volcanic origin (Yudhicara et al 2015). It has an extremely rugged landscape, with a central hilly plateau encompassed on its seaward sides by steep sloping ravines

Above: The Ata Déi Peninsula as seen from the west, with the cone of Ilé Labalekang in the distance. Below: The southeast corner of the Ata Déi Peninsula.

The south western corner of the peninsula is formed from an ancient long-dormant and well eroded volcano, while the south eastern corner is occupied by the active volcano of Ilé Werung. The whole of the peninsula is seismically active and has a number of geothermal hot springs.

Above: The topography of the Ata Déi Peninsula. Image courtesy of Google Maps

Below: A view of the Peninsula from the air

The Ilé Werung lava dome was formed as a result of a major eruption in 1870. Over the following century and a half, it has sporadically erupted numerous times – in 1910, 1928, 1948, 1949, 1950 and 1951. Between 1972 and 1974 the eruptions moved to a submarine vent directly south of Ilé Werung located about 800 metres from the shore, forming three ephemeral islands that were named Mount Hobal.

The caldera of Ilé Werung

In late 1978 there was an increase in seismic activity on the eastern side of Ata Déi that triggered a significant landslide. On 18 July 1979 there was an even larger landslide, again on the eastern side of the peninsula, which destroyed the village of Sarapuka and initiated a tsunami wiping out the village of Waiteba. Over 500 people were killed.

Mount Hobal erupted again in 1980, 1999, 2001, 2013 and 2021. The August 2013 eruption was the most significant, producing a 2km-high column of ash, boiling water and incandescent flames on the sea surface.

Further north, the village of Watuwawer is located above a geothermal field, where hot fluid upwells to the surface through hot springs and fumaroles via an underground fracture (Supijo et al 2020). Local residents still use some of these outlets as a natural kitchen, cooking cassava, peanuts, sweet potatoes, corn and coconut in small fumaroles. Numerous geological studies over the last 15 years suggest this source of energy could be sufficient to support a small geothermal power plant.

In the local Lamaholot dialect, the name Ata Déi means standing man, a reference to the natural rock pillar located on the south coast of the peninsula. A local legend says that it is the fossilised body of an old woman who was responsible for the flooding of Keroko Pukan, two small islands to the west of Lembata that were the home of many of the local people’s ancestors (Barnes 1996, 58). Today those islands are known as Lapan and Batan.

A Sea Eagle perched on the top of the ‘standing man’ rock pillar

Politically the Ata Déi Peninsula forms the southern part of Kecamatan Atadei, one of the nine districts of Kabupaten Lembata. Its administrative centre is Kalikasa.

Kecamatan Atadei is divided into 15 village areas or desas:

| Atakore |

| Dori Pewut |

| Dulir |

| Ile Kerbau |

| Ile Kimok |

| Katakeja |

| Kowaape |

| Lebaata |

| Lerek |

| Lusilame |

| Nogo Doni |

| Nuba Atalojo |

| Nubahaeraka |

| Tubuk Rajan |

On the Ata Déi Peninsula, ten of its fifteen kampongs are located over 500 meters above sea level. Travel between villages has never been easy across this difficult terrain, but has improved in recent years.

Above: Some of the kampongs on the Ata Déi Peninsula. The 1979 landslide can be seen top right. Below: The track into kampong Lerek

The population of Kecamatan Atadei has declined significantly over the past four decades, while the population of Lembata has remained stable. This is because people have moved away to the island’s capital, Lewoleba, or to other islands to find work. This is especially so for men, so women make up 53% of the population.

The population of Kecamatan Atadei

| 1980 | 1990 | 1994 | 2022 |

| 11,397 | 10,062 | 9,144 | 7,739 |

Source: Barnes 1996 and Kecamatan Atadei dalam angka 2023

The majority of residents are subsistence farmers, using slash and burn techniques to grow maize, sweet potatoes, other root vegetables, hill rice, areca nut, coffee, coconut and bananas. Livestock is limited to pigs, goats and chickens, most of which are used for traditional ceremonies. After clearing the fields, the land is turned over and is planted at the start of the rainy season, around October. Harvest time is around March.

Above: Land being cleared on the Ata Déi Peninsula

Below: Hillside fields belonging to kampong Kenota

The district has 19 Catholic churches, 21 elementary schools (SD, sekola dasar), 4 junior high schools (SMP, sekola menengah pertama) and one vocational high school (SMK, sekola menengah kejuruan).

Above: The Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus at Lerek.

Below: The Church of the Very Sacred Heart at Watuwawer with the statue of Father Beeker who was murdered by a local resident in 1956.

Return to Top

Captain Beckering’s Visit in 1910

Prior to the imposition of Dutch rule, Lembata was a lawless island, with widespread robbery, murder and inter-village warfare.

In 1910 the Dutch officer Captain Beckering and a company of troops visited Lembata to register the population and confiscate weapons and firearms. Beckering found that the majority of the population lived in well-defended positions on the slopes of the four highest mountains (Ilé Mingar, Ilé Labalekang, Ilé Apé and Kédang) as well as on the high plateau on the Lerek Peninsula beyond Lebala. He noted that the mountain kampongs of Lerek were protected in the same way as the coastal Muslim kampong of Labala – surrounded by a fairly heavy circular palisade, reinforced here and there between the poles of the palisade with thorny bamboo (Beckering 1911, 190-191). In Watuwawer and Lélawerang the palisades were heavier and more intensively reinforced with thorny bamboo.

Kampong Watuwawer consisted of two large sections separated by a square with big banyan trees, access being provided through two narrow corridors. Within the kampong many more heavily palisaded approaches created further sections, each of which contained some houses.

These protective fences were originally erected to defend each kampong from enemy attack. They also served to keep goats and pigs within the kampong, so that they did not damage the surrounding gardens. Following Beckering’s arrival, the kampong chiefs were instructed to remove these defences and replace them with neat 1-meter-high fences, just sufficient to keep the animals within the kampong.

Almost all of the kampongs on the Lerek Peninsula were situated on a high plateau ringed by peaks around 800 metres high. They were surrounded by fields of corn (maize). The houses were built on 1-metre-high posts and all contained a room. However, it was rare to find any decorations on the houses. The corn granaries were built higher above the ground and had thick wooden discs, roughly 1-metre in diameter, arranged horizontally around the posts to prevent rats and other vermin from reaching the corn cobs.

Beckering also described an incident on the Lerek Peninsula that illustrated how simple disputes could easily escalate into cases of murder and kidnap. It started when a goat belonging to a man from kampong Nuba Kupak was killed by a dog owned by a resident of Tobilolong (Beckering 1911, 196-197). As compensation, the goat’s owner suggested that the two men kill the dog and that both of them then ate two animals. After the dog owner refused, the owner of the goat exercised his bokang – a tradition of making up one’s loss by means of theft from a third party. He went to Watuwawer and stole a sarong and 10 arm rings. Meanwhile despite having lost nothing and as a precaution against the possibility of losing his dog, the dog owner also went to Watuwawer and stole 2 sarongs, 10 arm rings and a pair of earrings.

In turn, the people who had been robbed in Watuwawer sought compensation by going to Atawolo and Borena and selling to their residents the fields and coconut trees belonging to Nuba Kupak, the dog owner’s village. In return they received payment of four sarongs, 20 ivory arm rings, 2 knives and 2 simple cotton sarongs.

To compensate for the loss of their fields, the people of Nuba Kupak then went to Lerek and stole three sarongs and 15 arm rings. Finally, the people of Lerek attacked Nuba Kupak, killing a man and a woman and kidnapping two girls. Meanwhile the people in Nuba Kupak, who could no longer feed themselves because of the loss of their fields, attacked Atawolo, resulting in further deaths on both sides.

When Beckering arrived one year later, both girls were still in Lerek. Beckering ordered the girls to be returned to their families and announced that from then on, incidents of kidnapping would be severely punished.

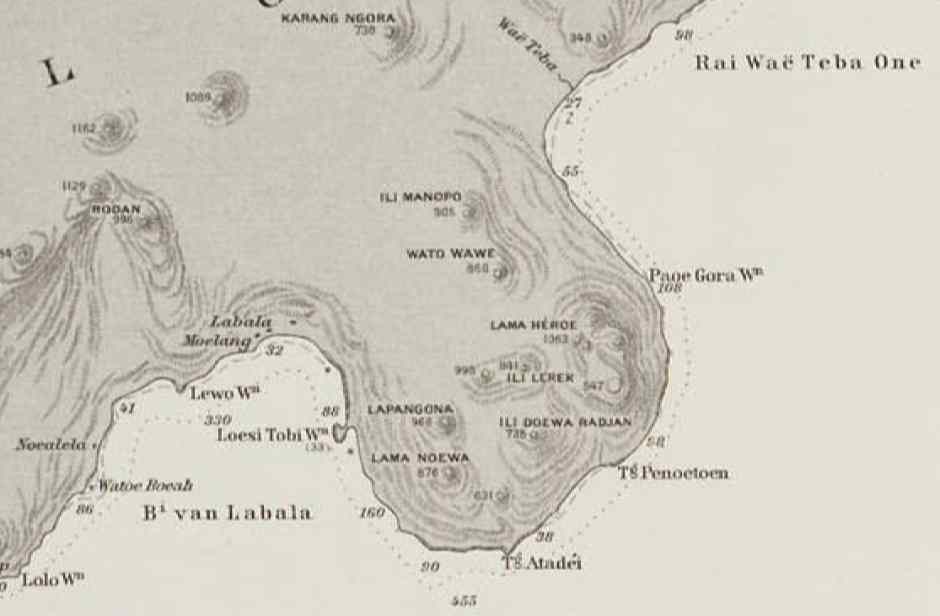

A hydrographic chart of Ata Déi dated 1911,

made at about the same time as Beckering’s visit

Return to Top

Ernst Vatter’s Visit in 1929

Ernst and Hanna Vatter visited Lembata, at that time called Lomblen, in June 1929 following their visits to Pantar and Alor. They sailed from Larantuka using a small motorboat and were met in Lewoleba by the Catholic missionary Father Preissler, who provided them with horses. They first rode to Lamalera where they spent a few days before setting off for the Lerek Peninsula, which Vatter termed the Labala Peninsula. Taking a local Lamalera whale boat, they sailed across Labala Bay to reach the coastal Islamic settlement of Labala. There, after some difficult negotiations, they procured new horses and a team of carriers, before embarking on the hazardous climb up to Lerek.

Vatter left us with a good descriptive picture of the region:

Our next destination was the mountainous land of Lerek in the interior of the Labala Peninsula. To get to Labala first, a purely Mohammedan coastal town, from where the ascent was to take place, we settled ourselves into one of the large Pledangs [tena whale boats], which travelled the distance in just under two hours. There was an unwanted stay of several hours in Labala; only after endless quarrels and fierce confrontations with the kakan and kapala there, real coastal Mohammedans who apparently decided to make trouble for us, was a horse procured for my wife and me along with the necessary number of carriers. So, we could not leave until three o'clock in the afternoon. The ascent into the mountains was extremely arduous, the narrow path was repeatedly blocked by boulders; at six o'clock it started to get dark, half an hour later we could hardly recognise the path in front of us, and soon we had to rely entirely on the instinct of our animals. Finally, it was already completely night-time, we saw a faint glimmer of light down in a valley basin: the kerosene lamp on the porch of the pastoral, which, as Father Bode correctly advised, the teacher had set up as a signal and signpost. Now the path went down steeply, right next to us a black abyss seemed to open. Branches and thorns hit us in the face, the horses slipped and stepped into deep holes, from which they tried to save themselves with a horrified jump. Finally, we were safe and soundly down.

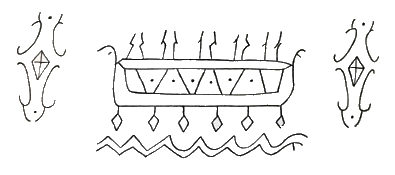

What distinguishes the natives of the mountain country of Lerek before all other inhabitants of the Solor-Alor archipelago is the extraordinarily rich tattooing, primarily of the women: the forehead, temples and cheeks, the skin area under the eyes, nose and upper lip, the shoulders, chest and back, and the arms and hands are all covered with deep blue ornaments. Particularly beautiful is the large breast ornament, "tana", i.e. "boat", the main element of which represents a strongly stylised Pledang with rowers positioned below and perhaps also its occupants positioned above (see below) and certainly indicates earlier close relationships of this population with the sea. In fact, several clans also come from other islands. The patterns are somewhat coarser than in East Flores and Solor, since unlike there, the punctures are not made with a thorn but with an iron spear; a slurry of soot in human milk is used for colouring.

The costume is still fairly undeveloped, men and women wear the self-woven sarong, the upper body usually remains uncovered.

Breast tattooing of the women in Lerek

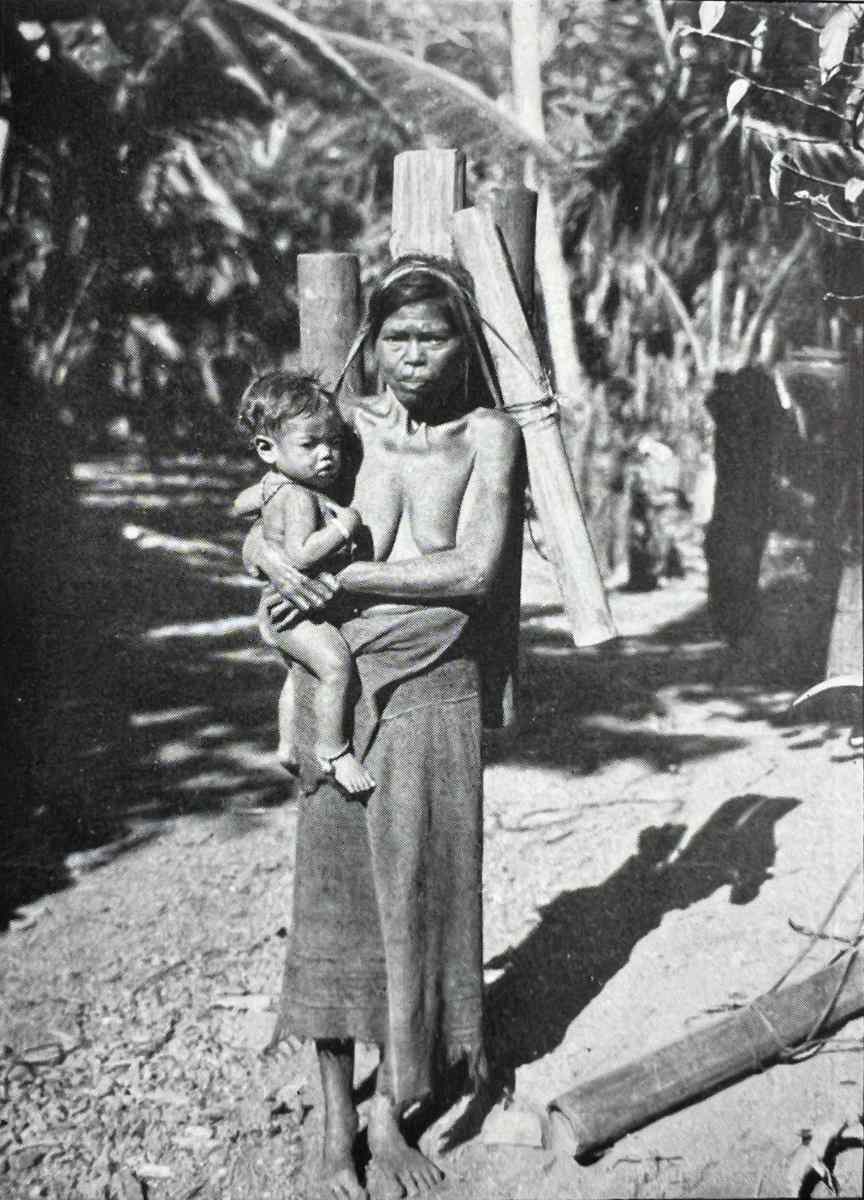

A lot is woven, but only a little ikatted. In some men, we still saw an old piece of jewellery: a belt made of large snail and coconut rings, which today is already very rare so the owners were reluctant to sell them to us. Peculiar to this area is also the way women carry water with a bundle of four or five bamboo tubes on their backs, the vessel’s hanging cords placed over the crown (s. Taf. 40,2).

A woman from Lerek on the way to the waterhole. Short bamboo tubes serve as containers, and up to half a dozen of them are hung over the head. Photographed by Ernst Vatter.

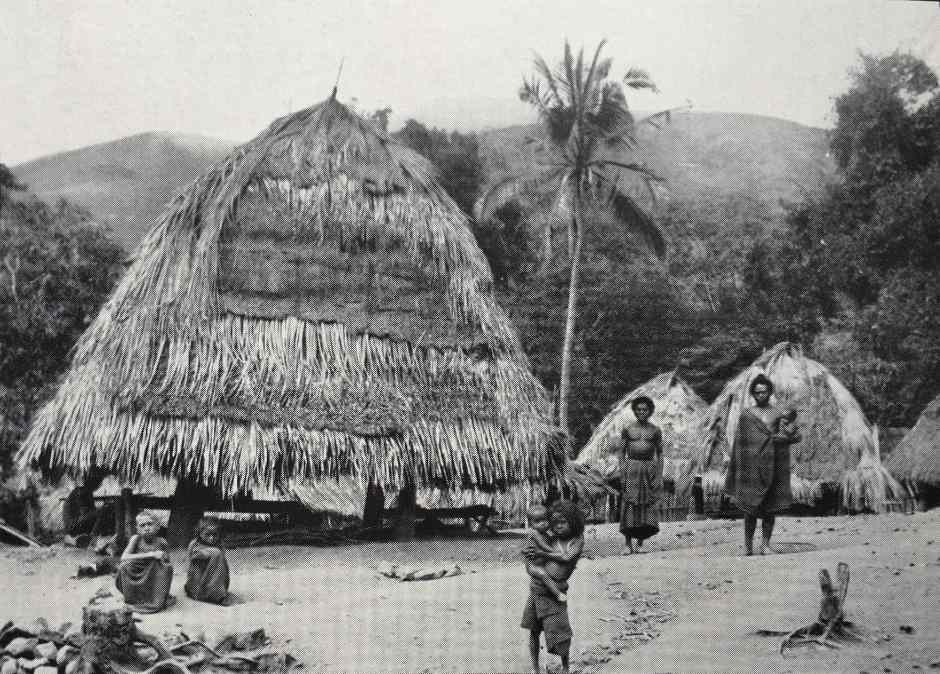

The houses "wata'" are small and unsightly and not roofed as usual with tufts of grass, but are covered with lined-up palm leaf strips and also with palm leaves, which gives them a somewhat messy and neglected appearance.

Houses with round-shaped roofs at Karang Ora

The roof extends almost down to the floor on all sides, so you have to bend down low to get inside the house. Only when you stand under the roof do you recognise the special shape of these houses: they are "real" prefabricated dwellings, i.e. the whole house stands like a granary on wooden piles, and in fact, they are also the union of a residential house and a corn store, we would like to call them a "residential store". This storage room rests on four piles, which are covered at the top with a wooden slice of "kelilit" to protect against the rats; in the open space between them, but protected against the wind by the low hanging roof, there are two bales on which in the warm season you eat, work and also sleep; here is also the kitchen with the three hearth stones on the ground. From the floor of the actual house, i.e. from the wooden piles, a bamboo frame with pots and other household goods usually hangs down. A thick branch of bamboo protrudes diagonally upwards into a hatch that forms the access to the [roof] interior; to get up, you step on this primitive ladder with one foot, at the same time grasp the edges of the hatch with your hands and pull yourself up. The interior itself is completely enclosed by the floor, roof and walls – the entrance hatch can also be sealed by a lid woven from palm leaves – it is a granary and a treasure chamber, in cool weather it is also used as a bedroom. On the floor there are some baskets of rice and a massive, over one metre high and wide, stack of corn cobs, which are stacked up in a similar way to the corn baskets in our photo below. In the past the women were not allowed to settle in these houses, but had to move into a special small birthing hut "bahar", of which there were several in the village. In Lerek itself they have now completely disappeared, but further north, in Watu Wawä, which we touched on the way to Karang Ora, such a birthing house still belongs to almost every "wäta", the residential storage house; both buildings are usually united into a farm within a common fence. The "bahar" are low huts built on four posts, not even 2-metres high, but do not serve exclusively for the confinement, but are also the residence of the woman and the small children, while the man lives in the "wata". It is only after sowing the rice that the woman settles with her husband to spend the next nights with him on the Baleh under the house and thus exert a fertility spell on the young seed.

Girls from Karang Ora in the fields with their baskets filled with corn cobs, stacked in the same way the cobs are stacked in the large baskets of the granaries

The population of Lerek is divided into five large and several small clans, some of which again come from Lapan Batang, but only via Tuakfutu, the sunken land between Adonara and the Gunung Api peninsula. Each of the large clans has its own korke "kokar" and in it its own "nuba-nara" stones, which according to tradition have been brought from Lapan Batang. The "strongest" of these stones, which is in the possession of the clan Lēwo Koba, is used by all clans as an oath stone, all oaths being placed on it. Its name is kotta bala, which is "ivory spinning top"; "spin", because it is sometimes supposed to turn in a circle by itself, "ivory spinning top" because of its preciousness and magical strength. Every korke, which, by the way, is just as poorly built and unsightly as the residential store, includes an "unan pègäwenän" (unan" is "house"), which corresponds to the "lango bälen", the sacred clan house of the rest of the Solor area that is inhabited by the head of the clan and contains its treasures and objects of worship. However, at the same time, it also seems to represent a kind of house of worship for women and in particular to serve the magic of pregnancy. Among the sanctuaries that are kept in these "unan pegäwenän", there is also a large "nuba-nara" stone, which bears a woman's name and is wrapped in a children's sarong; women who want a child sacrifice iron nails, arrowheads or simply small pieces of iron to it, a custom that may refer back to a time when iron was even more precious than today. Also, the wife of the head of the clan does not settle down like her comrades in one of the small birthing houses, but in the "unan pegäwenän" itself; and in some villages further north, e.g. in Karang Ora, does not live in it with the male clan head, but the oldest woman of the clan.

The clans are exogamous, but marriage is allowed in all other clans. The food taboos are again primarily directed against the women, e.g. the enjoyment of pork is prohibited in all groups. In individual clans, however, any indirect contact with this animal is also considered a violation of the taboo, for which Father Bode told us the following characteristic dispute, which could only be resolved after long negotiations. A teacher who had not been born in Lerek and did not yet know the views of his new home had borrowed a rice pounding trough from a family and used it in front of his house. By chance, a pig was slaughtered nearby, whereupon the owner of the trough refused to take it back and demanded a new one from the teacher. Because the pig was strictly taboo for his wives and daughters, and the rice pounding trough was "present" at the slaughter it could therefore no longer be used by them.

Here, in contrast to southwestern Lomblem, Léra-Wulan is called Lädja-Wulan, again the highest being in the area of Lerek, while Lahatala is quite unknown. In addition to Lëra-Wulan, however, the ancestral souls, the "kewoko" are always called upon. This is what they say of the rain magic, in which a chicken is slaughtered in the "unan pegäwenn" and its blood is drizzled "like rain" on young coconuts:

"Ina ama Lädja- Wulan, Tana-äkan,

ina ama tua magu, koda-kēwoko,

begam udjan, nē-turung!"

In translation:

"Mother, father (or " ina-ama" - parents), sun-moon, earth,

mother, father, you elders (= ancestors),

you dead souls, send rain, help us!"

A peculiar fertility spell is practised after the sowing of the rice: at the evening festival. The young men organise real boxing matches, in which they make massive punches to the face "to make the seeds strong". A similar fighting game is staged at the same festival and for the same magical purpose in the mountains around Lama Lêrap, only there the men violently push their opponents and try to knock them over.

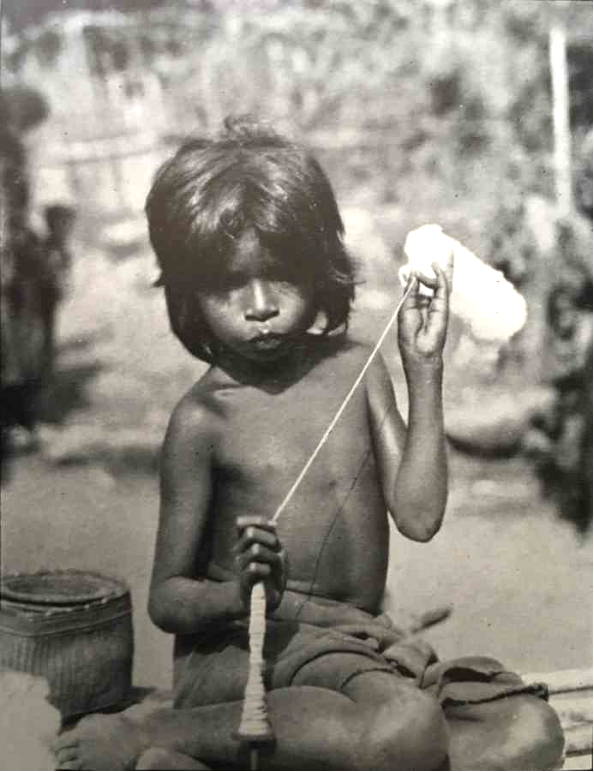

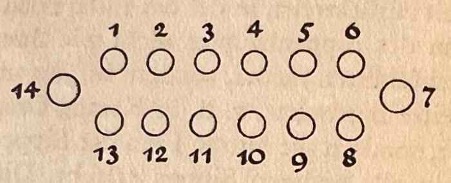

A young girl spinning yarn in Karang Ora

From Lerek, we rode on bad paths north via Watu Wawä to Karang Ora [today known as Ilé Kimok and shown on maps as Karangora], which is located in a deep, cauldron-shaped depression in the highlands. In addition to strong curly-haired people, there are also very simple-haired, non-negro types in the population. The residential stores are larger here, their roof is rounded like a barrel; the women's birthing huts look tiny next to them and live up to their name "una anaken", i.e. "small house", actually "children's house". Here in Karang Ora we saw a game (S. Taf. 44,2), which is found as a board game over a large part of the planet and is usually called by its Arabic name "Mankalah". On Java it is called "dakon", but here inside Lomblem "kêmotä". However, it was not played on a board, but on the earth: the required pits were simply scraped out in the sand. The game takes place in the following way: there are four stones in each hole; one of the two players starts at a hole, for example at 1. [The player] takes out the stones and puts one at a time in holes 2, 3, 4 and 5, then he takes the five stones from 5 and distributes them to 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, as well as the five stones from 10 to 11, 12, 13, 14 and 1. In this hole there is now only one stone, that player’s turn is over and it is the opponent's turn. It depends on the fact that when the stones are counted in, four of them come together again in a hole, which can then be taken out as a win. Whoever has won the most stones is the winner.

Above: The counting game called "kemota" played with stones or fruits in Karang Ora. Below: A schematic plan of the game “kemota’

Return to Top

Linguistics

Ata Déi is located in the Lamaholot-speaking region of eastern Indonesia, which extends from East Flores to the islands of Solor, Adonara and Lembata. Lamaholot belongs to the Timor subgroup of Central Malayo-Polynesian languages. It is not a single unified homogeneous language, but rather a family of dialects that in some cases differ so widely that they are mutually incomprehensible.

According to the linguist Gregorius Keraf (1978, 449-452), the people of Kecamatan Atadei speak four different dialects of Lamaholot: Painara, Kalikasa, Lewuka, and Lewokukun, there being a total of thirty-five different dialects on the whole island.

The four dialects of Kecamatan Atadei

The people on the Ata Déi Peninsula speak Ata Déi Painara. Daniel Krauße (2016, 116) has demonstrated how this dialect is significantly different from some of the other dialects of Lamaholot, both lexically (relating to words or vocabulary) and syntactically (the grammatical arrangement of words). This difference was brought home to us in 2013 when we visited Mulandoro with the crew members of a Lamalera whaling boat. The Lamalerans, who normally only sailed past Ata Déi, were shocked to discover that they could not understand a word of the local language. We had to find a local missionary who could speak Bahasa Indonesia to translate for us.

Although Lamaholot is primarily a language, its speakers are often treated as a distinct ethnic group, because they have similar social structures, beliefs and rituals.

Ethnography

Descent and kinship on Ata Déi is patrilineal, with offspring joining the clan or suku of their father. A few of these are higher-status clans that have land rights as a result of their ancestors being the first to arrive. Traditionally Lamaholot society was hierarchical, with the nobility, tatkabelan, the commoners, atakabalen, and the slaves, aziana (Melallatoa, 1995, 444). Today, status is determined by different factors such as education, profession, position in the government administration and of course wealth. Suku are responsible for negotiating marriage alliances and funeral arrangements.

The total number of clans or suku on Ata Déi is probably well in excess of one hundred. Villages differ widely in the number of clans they encompass. For example, Watuwawer has nine clans – Huar, Karang, Koban, Lajar, Lejab Ruin (eldest), Lejab Nujan (youngest), Lerek, Tukan and Wawin. Tukan is a clan that originated in Lerek. Some of the clans such as Lejab believe that their ancestors came from Lapan Batan, just like the people of Lamalera. Their ancestors arrived at roughly the same time, but settled in different parts of the island. The village of Watuwawer still conducts the Ahar ritual, which is believed to have originated on Lapan Batan. This is an initiation ceremony for boys and girls aged three to four conducted in July and August. It is only after this ceremony that the children can use their clan names.

In the past these sukus were strictly exogamous. People could only marry a partner if they were from a different clan. Because of the isolation of Ata Déi, this restriction is still generally maintained. As in the rest of the Lamaholot region, each clan has a number of long-standing alliances with up to three or four wife-giving clans and these alliances are one-directional (asymmetric). Thus, men from clan A can marry women from clan B, but men from clan B cannot marry women from clan A. They must marry women from another clan, such as clan C.

For example, in Watuwawer men from suku Ledjab can marry women from sukus Koban, Wawin and Huar. Men from suku Wawin can marry women from sukus Ledjab and Tukan. While men from suku Lerek can marry women from sukus Ledjab, Koban and Wawin.

Meanwhile in Atawolo, men from suku Namang can marry women from suku Tolok, men from suku Tolok can marry women from suku Henakin and men from suku Henakin can marry women from suku Namang.

Marriage requires an exchange of goods between the two clans. The traditional bridewealth from the man’s clan, known as pe weling, was one large elephant tusk, while the counter-prestation, known as pohe, consisted of textiles and ivory bracelets. A three-panel sarong plus five kala mutu ivory bracelets tied together was exchanged for a normal sized elephant tusk wheras a five-panel sarong plus five bracelets was exchanged for a large elephant tusk. Today an elephant tusk is quite rare and would be exchanged for four three-panel sarongs, along with five bracelets. However today, these bracelets would be made from shell not ivory.

In the past, every clan had its own clan house or korke, for conducting traditional ceremonies and for storing clan treasures, such as elephant tusks, silk patola and cotton imitation patola. Sadly the majority of these have fallen into disrepair and have been demolished. Today only the villages of Lamanunang, Lewogromang, Lewokoba and Watuwawer still have a traditional korke. The korke in Watuwawer is a small thatched structure which holds the treasures that the clan has inherited from its ancestors. These include five elephant tusks, three of which are said to have been brought to Lembata from Lapan Batan by three brothers and two that were obtained from other clans, a cotton imitation patola and some small textile fragments.

Above: The small Lejab Nujan clan house in Watuwawer, named Una Rajan.

Below: Niko, the keeper of the clan house with five large elephant tusks inherited from the clan’s ancestors

Return to Top

Bibliography

Anon, 2008. Livelihood in the Coastal and Midland Livelihood Zone, Lembata District: A household Economy Assessment in The Lembata District, Province of East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, Oxfam.

Ataladjar, Thomas B., 2015. Pai Hone Tala Ia, Pai Wane Tele Pia Lame Lusi Lako Dari Tanah Nubanara Menuju Tanah Misi, Penerbit, Koker-Jakarta.

Barnes, Robert H., 1996. Sea Hunters of Indonesia: Fishers and Weavers of Lamalera, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Beckering, J. D. H., 1911. Beschrijving der eilanden Adonara en Lomblem, behoorende tot de Solor-Groep, Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap, 2e Série, vol. 28, pp. 167-202.

Krauße, Daniel, 2016. A Brief Grammar of the Eastern Atadei Language of Lembata, Indonesia, Linguistik Indonesia, vol. ke-34, no. 2, pp. 113-128.

Ledjap, Donatus Dewa, 2014. Suku Ledjap: Rekonstruksi Jati Diri Orang Watuwawer, Absolute Media, Yogyakarta.

Vatter, Ernst, 1932. Ata Kiwan: unbekannte Bergvölker im tropischen Holland, ein Reisebericht, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig.

Yudhicara, Yudicara; Bani, Philipson and Darmawan, Alwin, 2015. Geothermal System as the Cause of the 1979 Landslide Tsunami in Lembata Island, Indonesia, Indonesian Journal on Geoscience, vol. 2, issue 2, pp. 91-99.

Return to Top

Publication

This webpage was published on 31 March 2024.